|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Gérard Thibault d'Anvers/Plates 12-22"

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 281: | Line 281: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | The usefulness of seizing the space inside the angle is so obvious, it should require no further proof. Anyone who has entered inside will always have twice the advantage, with regard to timing and distance. For he cannot be hit in a single beat, because he has passed the tip of his opponent’s sword, yet he has not given up the ability to attack however he wishes to. And if his enemy begins to draw back his sword to thrust, he can feel it and wound his enemy before he can pull it far enough, because he is in position, and outside his enemy’s line, and thus has the advantage. Also, note that those who fence in the old style, because they know no better, try to open up the angle, to beat the opposing sword aside. What we do with our sword, they want to do with their left hand. But this is their fault, because, since they always remain face to face against their opponents in a straight line, how is it possible for them to safely open up the angle, when we consider how this is the opposite of the direct line, and cannot happen except when one line crosses the other. This is why they do not know how to engage their enemy’s swords without uncovering their own side at the same time. That is why Alexander always approaches by moving to the side. Because he knows his enemy does not know how to parry the slightest strike without creating an angle. But if he does not create a large enough opening for them, there is nothing that stops him from executing his strike. And if not, he only needs to step inside the angle. | |

| − | |The usefulness of seizing the space inside the angle is so obvious, it should require no further proof. Anyone who has entered inside will always have twice the advantage, with regard to timing and distance. For he cannot be hit in a single beat, because he has passed the tip of his opponent’s sword, yet he has not given up the ability to attack however he wishes to. And if his enemy begins to draw back his sword to thrust, he can feel it and wound his enemy before he can pull it far enough, because he is in position, and outside his enemy’s line, and thus has the advantage. Also, note that those who fence in the old style, because they know no better, try to open up the angle, to beat the opposing sword aside. What we do with our sword, they want to do with their left hand. But this is their fault, because, since they always remain face to face against their opponents in a straight line, how is it possible for them to safely open up the angle, when we consider how this is the opposite of the direct line, and cannot happen except when one line crosses the other. This is why they do not know how to engage their enemy’s swords without uncovering their own side at the same time. That is why Alexander always approaches by moving to the side. Because he knows his enemy does not know how to parry the slightest strike without creating an angle. But if he does not create a large enough opening for them, there is nothing that stops him from executing his strike. And if not, he only needs to step inside the angle. | + | | class="noline" | L’uſage de ſaiſir les angles eſt ſi manifeſte, qu’il n’en faut pas demander des preuves. Car celuy qui eſt entré dedans, a touſiours double avantage au regard du temps & de la meſure. Dont il ne peut eſtre touché au Premier Inſtant, par ce qu’il a paſſé la pointe contraire, & pourtant il ne laiſſe pas d’avoir la commodité luy meſme de travailler à touts moments, ſi bon luy ſemble. & ſi l’Ennemy commence à vouloir ramener ſa pointe, il a le ſentiment qui l’advertit de le bleſſer au meſme temps avant qu’il en ſoit venu à bout de ſorte qu’il a l’ennemi en preſence, eſtant luy meſme dehors, tant il a d’avantage. Auſſi voit on que ceux qui tirent à la veille mode, à faute de ne ſçavoir mieux, ils taſchent d’ouvrir les angles pour battre l’eſpee contraire. Ce que nous faiſons avec l’eſpee meſme, ils le veulent faire avec la main gauche. mais c’eſt leur faute. car puis qu’ils demeurent touſiours viz à viz de leurs contraires en ce droite ligne, comment leur ſeroit il poſſible de bien ouvrir les angles, conſideré que l’angle ceſt tout le contraire de la ligne droite, & qu’il n’y en a peut avoir, ſinon que l’une des lignes ſoit miſe en travers de l’autre. Et c’eſt la cauſe pourquoy ils ne ſçauroyent engager les eſpees des Ennemis, qu’ils ne ſe deſcouvrent auſſi de leur coſté pareillement. Voilà donc pourquoy Alexandre a fait touſiours ſes approches en allant de travers. Pour ce qu’il ſçait que l’Ennemi ne ſçauroit parer le moindre coup ſans faire angle. Car s’il ne fait point aſſez d’ouverture, il n’y a rien qui l’empeſche de faire l’execution; & ſi au contraire, il ne tient qu’à luy d’entrer dedans l’angle. |

| − | |||

| − | |L’uſage de ſaiſir les angles eſt ſi manifeſte, qu’il n’en faut pas demander des preuves. Car celuy qui eſt entré dedans, a touſiours double avantage au regard du temps & de la meſure. Dont il ne peut eſtre touché au Premier Inſtant, par ce qu’il a paſſé la pointe contraire, & pourtant il ne laiſſe pas d’avoir la commodité luy meſme de travailler à touts moments, ſi bon luy ſemble. & ſi l’Ennemy commence à vouloir ramener ſa pointe, il a le ſentiment qui l’advertit de le bleſſer au meſme temps avant qu’il en ſoit venu à bout de ſorte qu’il a l’ennemi en preſence, eſtant luy meſme dehors, tant il a d’avantage. Auſſi voit on que ceux qui tirent à la veille mode, à faute de ne ſçavoir mieux, ils taſchent d’ouvrir les angles pour battre l’eſpee contraire. Ce que nous faiſons avec l’eſpee meſme, ils le veulent faire avec la main gauche. mais c’eſt leur faute. car puis qu’ils demeurent touſiours viz à viz de leurs contraires en ce droite ligne, comment leur ſeroit il poſſible de bien ouvrir les angles, conſideré que l’angle ceſt tout le contraire de la ligne droite, & qu’il n’y en a peut avoir, ſinon que l’une des lignes ſoit miſe en travers de l’autre. Et c’eſt la cauſe pourquoy ils ne ſçauroyent engager les eſpees des Ennemis, qu’ils ne ſe deſcouvrent auſſi de leur coſté pareillement. Voilà donc pourquoy Alexandre a fait touſiours ſes approches en allant de travers. Pour ce qu’il ſçait que l’Ennemi ne ſçauroit parer le moindre coup ſans faire angle. Car s’il ne fait point aſſez d’ouverture, il n’y a rien qui l’empeſche de faire l’execution; & ſi au contraire, il ne tient qu’à luy d’entrer dedans l’angle. | ||

|} | |} | ||

{{master end}} | {{master end}} | ||

| − | + | {{master begin | |

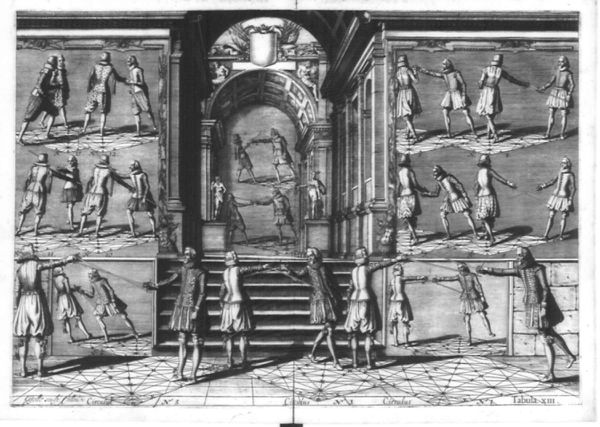

| title = Book 1 - Tableau / Plate XIII - Defeating or Defending With The Guard Raised High to Protect the Face | | title = Book 1 - Tableau / Plate XIII - Defeating or Defending With The Guard Raised High to Protect the Face | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 617: | Line 615: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | In sum, to see how Alexander does the actions in Circle No 6, by which he captures and subjugates his opponent’s sword, it seems there is nothing easier. This is because he works from a good foundation. And even though the swords do not always make contact in the same place, at the same Spans, nevertheless the choice of thrust, cuts, and holds which follow are entirely his own. He may freely take whichever pleases him. He will completely upend those ignorant or foolhardy imitators who have the temerity to to copy what they have seen done three or four times by a well trained and able man. From which they can gain only a sense of shame and confusion, when they try to test him, and find all their intentions frustrated at every moment, because they do not know the depth of this science, nor how difficult it is, nor the time, well worth the effort, which it requires to learn, nor the amount of study to bring to the subtleties of these examples. Gentlemen both presumptuous and ridiculous, who, having learned but two or three points, convince themselves that they fully understand the techniques, and that they can deal with any situation with the little that they know. They have no consideration of the full expanse, of the infinity of variation which dailly presents itself in training. Because each one has his own way of striking, different from all others, just as each hour, each minute, each instant changes from one to the next. So I can say, comparing the chamber, where debates are resolved with words, to the promenade where questions are settled with victory in arms, that just as [in logical discourse] arguments are subjected to critiques, critiques to responses, responses to reviews, reviews to commentaries until all evidence the adversaries wish to examine has been discussed, so in the performance of arms there is no stroke, either ordinary, or well examined, or completely grasped, or so secret, or so amazing, that it does not have a counter. As such one must never be too confident of any particular strike. What is good on one occasion will fail in another. It may be the best attack in the world, but nothing prevents someone from defending against it. It should not be that strange if common fencers are always unsure, given that their training, not being founded on general sciences, should fail to prepare them to face all situations, and so it must follow that much of the result of their workings depends in great measure on fortune, where the path of wisdom is closed to them. | |

| − | |In sum, to see how Alexander does the actions in Circle No 6, by which he captures and subjugates his opponent’s sword, it seems there is nothing easier. This is because he works from a good foundation. And even though the swords do not always make contact in the same place, at the same Spans, nevertheless the choice of thrust, cuts, and holds which follow are entirely his own. He may freely take whichever pleases him. He will completely upend those ignorant or foolhardy imitators who have the temerity to to copy what they have seen done three or four times by a well trained and able man. From which they can gain only a sense of shame and confusion, when they try to test him, and find all their intentions frustrated at every moment, because they do not know the depth of this science, nor how difficult it is, nor the time, well worth the effort, which it requires to learn, nor the amount of study to bring to the subtleties of these examples. Gentlemen both presumptuous and ridiculous, who, having learned but two or three points, convince themselves that they fully understand the techniques, and that they can deal with any situation with the little that they know. They have no consideration of the full expanse, of the infinity of variation which dailly presents itself in training. Because each one has his own way of striking, different from all others, just as each hour, each minute, each instant changes from one to the next. So I can say, comparing the chamber, where debates are resolved with words, to the promenade where questions are settled with victory in arms, that just as [in logical discourse] arguments are subjected to critiques, critiques to responses, responses to reviews, reviews to commentaries until all evidence the adversaries wish to examine has been discussed, so in the performance of arms there is no stroke, either ordinary, or well examined, or completely grasped, or so secret, or so amazing, that it does not have a counter. As such one must never be too confident of any particular strike. What is good on one occasion will fail in another. It may be the best attack in the world, but nothing prevents someone from defending against it. It should not be that strange if common fencers are always unsure, given that their training, not being founded on general sciences, should fail to prepare them to face all situations, and so it must follow that much of the result of their workings depends in great measure on fortune, where the path of wisdom is closed to them. | + | | class="noline" | En ſomme à voir faire à Alexandre l’operation du Cercle N.6. par laquelle il enferme & aſſujettit l’eſpee contraire, il ſemble, qu’il n’y ait rien plus facile. c’eſt pour autant qu’il travaille avec fondement. Et encores que les eſpees ne s’accouplent pas touſiours aux meſmes endroits, & à meſmes Nombres; toutesfois le chois des eſtocades, coups de taille, & prinſes, qui s’en enſuivent, ne depend que de ſa ſeule elećtion; il en prendra librement celle, qui luy viendra le plus à gré. Tout au rebours en ſera il de ces ignorants & hardis entrepreneurs d’imiter temerairement tout ce qu’ils auront veu pratiquer trois ou quatre fois à vn homme adroit & bien fondé: dequoy ils ne peuvent raporter que honte & confuſion, quand il eſt queſtion d’en venir aux preuves, ſe voyants fruſtrez à touts moments de leurs intentions, à faute de ne cognoiſtre pas l’amplitude de ceſte Science, ne combien elle eſt difficle, le temps qu’elle requiert & merite pour l’apprendre, ne l’eſtude qu’il faut apporter à la ſubtilité de ſes demonſtrations. Gents preſomptueux & ridicules; qui n’ayants apprins, que deux ou trois pointilles, ſe ſont accroire, que rien ne leur manque, ſur l’aſſeurance qu’ils ont de faire ſervir à toutes occaſions le peu qu’ils en ſavent; ſans conſiderer la grande eſtendue, voire l’infinité des variations, qui ſe preſentent journellement en la Pratique; par ce que chaſcun a ſa propre maniere à tirer differemment des autres, voire que les heures, les minutes, les inſtants touſiours ſe changent. Dont je puis dire, en faiſant compariſon du bureau, où les debats ſe finiſſent par paroles, avec le parquet où les queſtions ſe terminent par la victoire des armes, que comme les accuſations ſont ſujettes aux exceptions, les exceptions aux repliques, le repliques aux duplications, triplications, & finalement à toutes les Inſtances que la partie adverſe voudra faire; ainſi au fait des armes il n’y a aucun trait tant ordinaire, tant bien examiné, tant priſé, tant ſecret, ne tant admirable, que n’ait ſon contraire; de ſorte qu’il ne faut jamais fier en aucun trait particulier; tout ce qui eſt bon en l’une des occaſions, eſtant faux en l’autre: ſoit aſſailli le mieux du monde, rien n’empeſche qu’il ne ſoit encore mieux defendu. Dont ſi les vulgaires en demeurent eſtonnez, il ne faut pas le trouver eſtrange; attendu que leur pratique, n’eſtant pas fondée en ſcience generale, qui ſoit baſtante à les preparer contre toutes occurrences, il s’enſuit de neceſſité, que les iſſues de leurs entreprinſes dependent en partie du ſort de la Fortune, qui domine par tout, où la Prudence eſt forcloſe. |

| − | |||

| − | |En ſomme à voir faire à Alexandre l’operation du Cercle N.6. par laquelle il enferme & aſſujettit l’eſpee contraire, il ſemble, qu’il n’y ait rien plus facile. c’eſt pour autant qu’il travaille avec fondement. Et encores que les eſpees ne s’accouplent pas touſiours aux meſmes endroits, & à meſmes Nombres; toutesfois le chois des eſtocades, coups de taille, & prinſes, qui s’en enſuivent, ne depend que de ſa ſeule elećtion; il en prendra librement celle, qui luy viendra le plus à gré. Tout au rebours en ſera il de ces ignorants & hardis entrepreneurs d’imiter temerairement tout ce qu’ils auront veu pratiquer trois ou quatre fois à vn homme adroit & bien fondé: dequoy ils ne peuvent raporter que honte & confuſion, quand il eſt queſtion d’en venir aux preuves, ſe voyants fruſtrez à touts moments de leurs intentions, à faute de ne cognoiſtre pas l’amplitude de ceſte Science, ne combien elle eſt difficle, le temps qu’elle requiert & merite pour l’apprendre, ne l’eſtude qu’il faut apporter à la ſubtilité de ſes demonſtrations. Gents preſomptueux & ridicules; qui n’ayants apprins, que deux ou trois pointilles, ſe ſont accroire, que rien ne leur manque, ſur l’aſſeurance qu’ils ont de faire ſervir à toutes occaſions le peu qu’ils en ſavent; ſans conſiderer la grande eſtendue, voire l’infinité des variations, qui ſe preſentent journellement en la Pratique; par ce que chaſcun a ſa propre maniere à tirer differemment des autres, voire que les heures, les minutes, les inſtants touſiours ſe changent. Dont je puis dire, en faiſant compariſon du bureau, où les debats ſe finiſſent par paroles, avec le parquet où les queſtions ſe terminent par la victoire des armes, que comme les accuſations ſont ſujettes aux exceptions, les exceptions aux repliques, le repliques aux duplications, triplications, & finalement à toutes les Inſtances que la partie adverſe voudra faire; ainſi au fait des armes il n’y a aucun trait tant ordinaire, tant bien examiné, tant priſé, tant ſecret, ne tant admirable, que n’ait ſon contraire; de ſorte qu’il ne faut jamais fier en aucun trait particulier; tout ce qui eſt bon en l’une des occaſions, eſtant faux en l’autre: ſoit aſſailli le mieux du monde, rien n’empeſche qu’il ne ſoit encore mieux defendu. Dont ſi les vulgaires en demeurent eſtonnez, il ne faut pas le trouver eſtrange; attendu que leur pratique, n’eſtant pas fondée en ſcience generale, qui ſoit baſtante à les preparer contre toutes occurrences, il s’enſuit de neceſſité, que les iſſues de leurs entreprinſes dependent en partie du ſort de la Fortune, qui domine par tout, où la Prudence eſt forcloſe. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 629: | Line 625: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 999: | Line 995: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

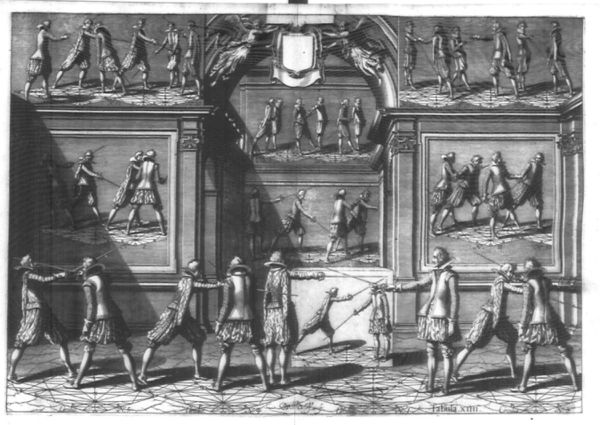

| − | + | | class="noline" | Here we have another action that has the same beginning in Circle No 14, where Alexander subjugates the opposing sword by stepping with his right foot towards the Centre, to block his path. In this Circle, Zachary advances and enters at the same time with his left side and foot, set down at the letter M along the Perpendicular Diameter, drawing the right foot along behind, and grasping with his left hand to grab his opponent’s guard. While he is making these moves, Alexander withdraws his arm and the guard back and to the left side, while putting his left foot on the Outside Square on the Oblique Diameter. He then proceeds to move his sword in a circle above over his head to cut at his opponent’s left ear, while withdrawing his right foot to the letter I on the Oblique Diameter. As we can see in the image. | |

| − | |Here we have another action that has the same beginning in Circle No 14, where Alexander subjugates the opposing sword by stepping with his right foot towards the Centre, to block his path. In this Circle, Zachary advances and enters at the same time with his left side and foot, set down at the letter M along the Perpendicular Diameter, drawing the right foot along behind, and grasping with his left hand to grab his opponent’s guard. While he is making these moves, Alexander withdraws his arm and the guard back and to the left side, while putting his left foot on the Outside Square on the Oblique Diameter. He then proceeds to move his sword in a circle above over his head to cut at his opponent’s left ear, while withdrawing his right foot to the letter I on the Oblique Diameter. As we can see in the image. | + | | class="noline" | Voicy une operation qui a auſſi le meſme commencement du Cercle N.14. où <font style="font-variant:small-caps">Alexandre</font> aſſujettit l’eſpee contraire en marchant avec le pied droit devers le Centre pour luy couper le chemin. En ce preſent Cercle <font style="font-variant:small-caps">Zacharie</font> s’avance & entre au meſme temps avec le coſté & le pied gauche à planter à la lettre M par delà le Diametre, entrainant & voltant auſſi le pied droit derriere, & gripant avec la main gauche pour prendre la garde contraire. Durant ces dit mouvements <font style="font-variant:small-caps">Alexandre</font> ſe retire le bras & la garde à main gauche & vers le bas, en reculant auſſi le meſme pied ſur le Quarrè Circonſcrit, à planter ſur le Diametre Oblicq, conduiſant à l’advenant ſa lame circulairement en haut par deſſus ſa teſte, & en donnant un coup de taille au contraire à l’oreille gauche, en retirant le pied droit en deçà le Diametre à la lettre I; comme on le voit en la repreſentation des figures. |

| − | |||

| − | |Voicy une operation qui a auſſi le meſme commencement du Cercle N.14. où <font style="font-variant:small-caps">Alexandre</font> aſſujettit l’eſpee contraire en marchant avec le pied droit devers le Centre pour luy couper le chemin. En ce preſent Cercle <font style="font-variant:small-caps">Zacharie</font> s’avance & entre au meſme temps avec le coſté & le pied gauche à planter à la lettre M par delà le Diametre, entrainant & voltant auſſi le pied droit derriere, & gripant avec la main gauche pour prendre la garde contraire. Durant ces dit mouvements <font style="font-variant:small-caps">Alexandre</font> ſe retire le bras & la garde à main gauche & vers le bas, en reculant auſſi le meſme pied ſur le Quarrè Circonſcrit, à planter ſur le Diametre Oblicq, conduiſant à l’advenant ſa lame circulairement en haut par deſſus ſa teſte, & en donnant un coup de taille au contraire à l’oreille gauche, en retirant le pied droit en deçà le Diametre à la lettre I; comme on le voit en la repreſentation des figures. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,011: | Line 1,005: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 1,283: | Line 1,277: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | History tells of the Roman General Fabius Maximus, who harassed the army of Hannibal and thus saved the Republic. VNVS HOMO NOBIS CUNCTANDO RESTITVIT REM (“One man, by delaying, restored the state to us”). Our students should take heed to likewise learn above all to manage their attack with patience. There is no reason at all to be hasty during the initial approach, because one does not know how one’s adversary will behave, whether one must work quickly or slowly, attacking forward, or defending backwards. Anything else would be temerity made manifest. It is true that those who hold to the common style agree with this, except when it comes to performing the pauses which we require when in the midst of combat, then they strongly object. They claim that victory is lost whenever one holds back, and that each slight pause is a fault, because, they say, one cannot disrupt an enemy, except by constant speed, so that he does not have time to respond, and it would be useless to even think of doing anything differently; that one could neither offend, nor defend, since pauses cannot be but like a burden that slows a packhorse and would leave one unable to meet the short, fast attacks which strike and strike again, and hit before one could stop them. I reply, to those who value nothing other than that one thing, that in our system we have no intention of only taking our time and disregarding speed, but that each one has its use, as much as the other, and that security comes from caution, as much as strikes succeed through quickness. It is not the back-and-forth motion of the arms, nor the clash of swords, nor the impetus of the body, nor the stamping of the feet which produce hits, these are merely movements. Careful preparations are not in fear, but in order to effectively deliver big hits, one needs to make certain of one’s approach, until one has the range and opportunity to hit with one quick motion. This how to offend your adversary, together with your proper defense, instead of just using speed which leaves you completely uncovered because it does not allow you time to assess your opponent’s actions. | |

| − | |History tells of the Roman General Fabius Maximus, who harassed the army of Hannibal and thus saved the Republic. VNVS HOMO NOBIS CUNCTANDO RESTITVIT REM (“One man, by delaying, restored the state to us”). Our students should take heed to likewise learn above all to manage their attack with patience. There is no reason at all to be hasty during the initial approach, because one does not know how one’s adversary will behave, whether one must work quickly or slowly, attacking forward, or defending backwards. Anything else would be temerity made manifest. It is true that those who hold to the common style agree with this, except when it comes to performing the pauses which we require when in the midst of combat, then they strongly object. They claim that victory is lost whenever one holds back, and that each slight pause is a fault, because, they say, one cannot disrupt an enemy, except by constant speed, so that he does not have time to respond, and it would be useless to even think of doing anything differently; that one could neither offend, nor defend, since pauses cannot be but like a burden that slows a packhorse and would leave one unable to meet the short, fast attacks which strike and strike again, and hit before one could stop them. I reply, to those who value nothing other than that one thing, that in our system we have no intention of only taking our time and disregarding speed, but that each one has its use, as much as the other, and that security comes from caution, as much as strikes succeed through quickness. It is not the back-and-forth motion of the arms, nor the clash of swords, nor the impetus of the body, nor the stamping of the feet which produce hits, these are merely movements. Careful preparations are not in fear, but in order to effectively deliver big hits, one needs to make certain of one’s approach, until one has the range and opportunity to hit with one quick motion. This how to offend your adversary, together with your proper defense, instead of just using speed which leaves you completely uncovered because it does not allow you time to assess your opponent’s actions. | + | | class="noline" | L’hiſtoire teſmoigne de Fabius Maximus General de l’Armee Romaine, qu’en trainant l’Armee de Hannibal il a redreſſé la Republique: Vnvs homo nobis cunctando restituit rem. Noſtre Eſcholier ſe doit propoſer ſemblablement d’apprendre ſur tout à meſnager ſes forces. Auſsi n’a il nulle raiſon de ſe haſter durant les premieres approches, par ce qu’il ne ſçait quelle ſituation l’Adverſaire doit prendre, s’il doit travailler viſte ou lentement, en avant, ou en arriere. Ce ſeroit donc une temerité manifeſte. Et de vray ceux qui ſe tiennent à la Pratique vulgaire, confeſſent le meſme. Mais touchant les pauſes que nous requerons au milieu de la bataille, il leur ſemble qu’ils ont grande occaſion d’y contredire. Car ils objećtent, que la vićtoire s’envole à touts les fois qu’on la refuſe, & que touts les clins d’oeil qu’on ſe retarde, ſont autant de fautes; pour ce qu’on ne peut mettre l’Ennemy en desorder, ſinon par la viſteſſe, de façon qu’il ne ſache de quelle part il nous doive attendre: & ſi nous penſons d’y aller autrement, que nous ne ferons rien qu vaille, ny pour offenſer, ny pour defendre, d’autant que la tardiveté ne pourra eſtre baſtante à rencontrer tant de fretillements, qui paſſent, & repaſſent, & arrivent avant qu’on le puiſſe atteindre. Ie reſpons que ce n’eſt pas notſte intention de priſer la ſeule tardiveté des aćtions & en desprinſer la viſteſſe: mais que l’une y doit avoir ſa place, auſsi bien que l’autre, & que les aſſeurances procedent de la tardiveté, comme les executions de la viſteſſe; reprenant ceux qui n’eſtiment rien valable aux prix d’elle ſeule. Ce ne ſont pas les branſlements du bras, ny le cliquement des eſpees, ny les impetuoſitez du corps, ny le battements des pieds, qui donnent les atteintes, ce ſont des ſimples mouvements: les grandes preparations, ne ſont pas à craindre, mais les grands coups, pour leſquels effećtuer il ne faut qu’aſſeurer ſes approches, juſqu’à tant qu’on ait le moyen de prendre une ſeule fois le temps à ſon avantage. Voilà la maniere d’offenſer voſtre Adverſaire, conjoinćte avec voſtre propre defenſe, au lieu de ceſte grande viſteſſe qui en eſt toute deſnuée, par ce qu’elle n’a pas le loiſir d’examiner les aćtions du Contraire. |

| − | |||

| − | |L’hiſtoire teſmoigne de Fabius Maximus General de l’Armee Romaine, qu’en trainant l’Armee de Hannibal il a redreſſé la Republique: Vnvs homo nobis cunctando restituit rem. Noſtre Eſcholier ſe doit propoſer ſemblablement d’apprendre ſur tout à meſnager ſes forces. Auſsi n’a il nulle raiſon de ſe haſter durant les premieres approches, par ce qu’il ne ſçait quelle ſituation l’Adverſaire doit prendre, s’il doit travailler viſte ou lentement, en avant, ou en arriere. Ce ſeroit donc une temerité manifeſte. Et de vray ceux qui ſe tiennent à la Pratique vulgaire, confeſſent le meſme. Mais touchant les pauſes que nous requerons au milieu de la bataille, il leur ſemble qu’ils ont grande occaſion d’y contredire. Car ils objećtent, que la vićtoire s’envole à touts les fois qu’on la refuſe, & que touts les clins d’oeil qu’on ſe retarde, ſont autant de fautes; pour ce qu’on ne peut mettre l’Ennemy en desorder, ſinon par la viſteſſe, de façon qu’il ne ſache de quelle part il nous doive attendre: & ſi nous penſons d’y aller autrement, que nous ne ferons rien qu vaille, ny pour offenſer, ny pour defendre, d’autant que la tardiveté ne pourra eſtre baſtante à rencontrer tant de fretillements, qui paſſent, & repaſſent, & arrivent avant qu’on le puiſſe atteindre. Ie reſpons que ce n’eſt pas notſte intention de priſer la ſeule tardiveté des aćtions & en desprinſer la viſteſſe: mais que l’une y doit avoir ſa place, auſsi bien que l’autre, & que les aſſeurances procedent de la tardiveté, comme les executions de la viſteſſe; reprenant ceux qui n’eſtiment rien valable aux prix d’elle ſeule. Ce ne ſont pas les branſlements du bras, ny le cliquement des eſpees, ny les impetuoſitez du corps, ny le battements des pieds, qui donnent les atteintes, ce ſont des ſimples mouvements: les grandes preparations, ne ſont pas à craindre, mais les grands coups, pour leſquels effećtuer il ne faut qu’aſſeurer ſes approches, juſqu’à tant qu’on ait le moyen de prendre une ſeule fois le temps à ſon avantage. Voilà la maniere d’offenſer voſtre Adverſaire, conjoinćte avec voſtre propre defenſe, au lieu de ceſte grande viſteſſe qui en eſt toute deſnuée, par ce qu’elle n’a pas le loiſir d’examiner les aćtions du Contraire. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,295: | Line 1,287: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 1,531: | Line 1,523: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

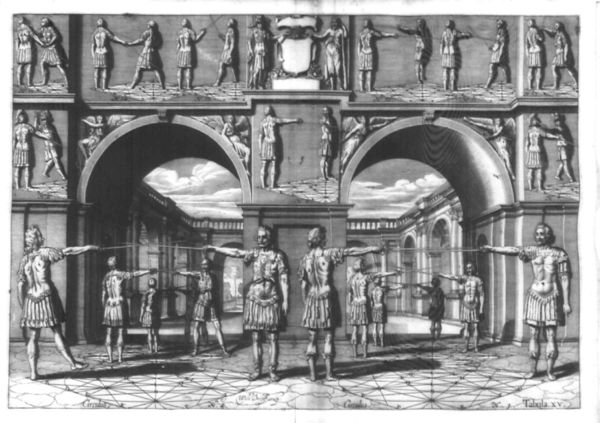

| − | + | | class="noline" | There is no question but physical strength is of very great importance , when it comes to fighting. Nature herself imprints this, with I cannot say what degree of terror, such that we are often stunned, not just by the sight of those who are blessed with huge size, but at the mere mention of such. However, we can see that even the strength of lions, bears, and tigers are of no use against man’s agility and cleverness. Where does this come from, if not that great power is always accompanied by some weakness by which one can exploit? The same thing is in our System. If our opponent’s appearance seems to be intimidating, yet they still have their weaknesses, through which we can master and overcome them and against which they will never have the luxury of enough time to work out a counter-move. Having seen the benefits of Alexander’s agility, we should do likewise. We may hold our physical strength in high regard, but we will lose all benefit should we try to resort to that too early. That is why Alexander remains content to contain his adversary with small movements, reserving his strength until the proper time to make use of it presents itself so perfectly that is impossible not to take full advantage of the chance. Which we can manifestly see in all the examples in this current Plate. | |

| − | |There is no question but physical strength is of very great importance , when it comes to fighting. Nature herself imprints this, with I cannot say what degree of terror, such that we are often stunned, not just by the sight of those who are blessed with huge size, but at the mere mention of such. However, we can see that even the strength of lions, bears, and tigers are of no use against man’s agility and cleverness. Where does this come from, if not that great power is always accompanied by some weakness by which one can exploit? The same thing is in our System. If our opponent’s appearance seems to be intimidating, yet they still have their weaknesses, through which we can master and overcome them and against which they will never have the luxury of enough time to work out a counter-move. Having seen the benefits of Alexander’s agility, we should do likewise. We may hold our physical strength in high regard, but we will lose all benefit should we try to resort to that too early. That is why Alexander remains content to contain his adversary with small movements, reserving his strength until the proper time to make use of it presents itself so perfectly that is impossible not to take full advantage of the chance. Which we can manifestly see in all the examples in this current Plate. | + | | class="noline" | Il eſt certain que les forces corporelles ſont de tres-grande importance, quand il eſt queſtion de ſe battre. Nature meſme leur a empraint, je ne ſay quelle marque effroyable, par laquelle nous ſommes eſtonnez non ſeulement en regardant entre les yeux ceux qui en ſont douez par deſſus les autres, mais encore aſſez de fois, à les ouir nommer tant ſeulement. Cependant on voit qu’aux Lions, Ours, & Tigres toute leur force ne profite de rien contre la dexterité des hommes. D’ou vient cela? Sinon de ce que la force eſt touſiours accompagnée de quelque foibleſſe, où on l’attrappe. Le meſme en eſt il en noſtre Exercice. Si les mouvements du Contraire ſont terribles en apparance, ils ne laiſſent pas pourtant d’avoir leur foibleſſe, durant laquelle on les peut maiſtriſer & prevenir, qu’ils n’ayent jamais le loiſir de ſe renforcer à leur avantage. Voylà la dexterité de noſtre Alexandre faiſons en de meſme. Eſtimons grandement nos forces corporelles; mais ſachons que nous en perdrons le fruit, ſi nous en voulons avoir l’uſage avant le temps. C’eſt pourquoy Alexandre ſe contente d’entretenir l’Adverſaire avec de petits mouvements, reſervant ſes forces juſqu’à tant que l’occaſion de s’en prevaloir ſe preſente ſi belle, qu’il ſoit impoſsible quelle luy eſchappe: comme on voit manifeſtement en touts les Exemples de ce preſent Tableau. |

| − | |||

| − | Il eſt certain que les forces corporelles ſont de tres-grande importance, quand il eſt queſtion de ſe battre. Nature meſme leur a empraint, je ne ſay quelle marque effroyable, par laquelle nous ſommes eſtonnez non ſeulement en regardant entre les yeux ceux qui en ſont douez par deſſus les autres, mais encore aſſez de fois, à les ouir nommer tant ſeulement. Cependant on voit qu’aux Lions, Ours, & Tigres toute leur force ne profite de rien contre la dexterité des hommes. D’ou vient cela? Sinon de ce que la force eſt touſiours accompagnée de quelque foibleſſe, où on l’attrappe. Le meſme en eſt il en noſtre Exercice. Si les mouvements du Contraire ſont terribles en apparance, ils ne laiſſent pas pourtant d’avoir leur foibleſſe, durant laquelle on les peut maiſtriſer & prevenir, qu’ils n’ayent jamais le loiſir de ſe renforcer à leur avantage. Voylà la dexterité de noſtre Alexandre faiſons en de meſme. Eſtimons grandement nos forces corporelles; mais ſachons que nous en perdrons le fruit, ſi nous en voulons avoir l’uſage avant le temps. C’eſt pourquoy Alexandre ſe contente d’entretenir l’Adverſaire avec de petits mouvements, reſervant ſes forces juſqu’à tant que l’occaſion de s’en prevaloir ſe preſente ſi belle, qu’il ſoit impoſsible quelle luy eſchappe: comme on voit manifeſtement en touts les Exemples de ce preſent Tableau. | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,543: | Line 1,533: | ||

| width = 60em | | width = 60em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="master" |

! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ! Translation by <br/> [[user:Bruce Hearns|Bruce G. Hearns]] | ||

| Line 1,920: | Line 1,910: | ||

|- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | |- style="font-family: times, serif; vertical-align:top;" | ||

| − | + | | class="noline" | As a general obeservation of some great consequence, all movements are easily overcome as they first begin. As experience in all things demonstrates, there is nothing strong which was not once weak. Consider, for example, the infancy of trees, of beasts, of men; the foundation of cities, of peoples, and Kingdoms; the general time span of all things which increase by degree, to find at base their point of birth. consider the ease with which these, at that point, could be mastered, taking no great pains. And yet, if one leaves these alone, they shall strangthen over time, some so much that there is no way to rein them back. Take a millstone, grinding at the summit of a mountain, which begins to break away to roll from the top to the bottom. It is possible, at the very first, to hold it with but the force of a hand, oftimes merely a finger is enough. If it begins to lean, one may still hold it back with one’s body. But if it begins to roll, if it has already made a single turn from top to bottom, what strength has any man to stop, slow, or turn it from its course? It is the same with blows or cuts, as in Circle No 3. If you wait, so that the motion has descended, then all that you would try, to bring it under control, is a lost cause. The force will be too great. But if you act at the beginning, it will be easy. That way, there is little more to do than to quickly align your sword-tip, as it should be, so as to have the swords contact at the instant his unwinds. I am not saying you must chase after his sword, but rather to constrain his so that his must strike along the length of your blade; that your action is founded less on strength and more on skill; that you must aim your sword-tip and connect with the middle of his blade. This is the principle and the source of all his strength. For as long as you have reached the centre of his blade, he must contend against the entirety of your blade, not more nor less than the short part of your blade, in the same way as when one draws near a candle when one wishes to remove the light spread about a room, or when the Sun shines its rays through a small aperture and the light expands, it is easier to block the aperture with a hand than to try and stop it with the entire body at a distance when the light has expanded too much. So there is no point in doing otherwise because when one gives a cut the centre of the sword almost remains in the same place, and so is very easy to find and contact, whereas the tip revolves in a large arc, and so swiftly that it would be impossible to attain. From which, we see, again, as before, that the power begins with the beginning of the motion. | |

| − | |As a general obeservation of some great consequence, all movements are easily overcome as they first begin. As experience in all things demonstrates, there is nothing strong which was not once weak. Consider, for example, the infancy of trees, of beasts, of men; the foundation of cities, of peoples, and Kingdoms; the general time span of all things which increase by degree, to find at base their point of birth. consider the ease with which these, at that point, could be mastered, taking no great pains. And yet, if one leaves these alone, they shall strangthen over time, some so much that there is no way to rein them back. Take a millstone, grinding at the summit of a mountain, which begins to break away to roll from the top to the bottom. It is possible, at the very first, to hold it with but the force of a hand, oftimes merely a finger is enough. If it begins to lean, one may still hold it back with one’s body. But if it begins to roll, if it has already made a single turn from top to bottom, what strength has any man to stop, slow, or turn it from its course? It is the same with blows or cuts, as in Circle No 3. If you wait, so that the motion has descended, then all that you would try, to bring it under control, is a lost cause. The force will be too great. But if you act at the beginning, it will be easy. That way, there is little more to do than to quickly align your sword-tip, as it should be, so as to have the swords contact at the instant his unwinds. I am not saying you must chase after his sword, but rather to constrain his so that his must strike along the length of your blade; that your action is founded less on strength and more on skill; that you must aim your sword-tip and connect with the middle of his blade. This is the principle and the source of all his strength. For as long as you have reached the centre of his blade, he must contend against the entirety of your blade, not more nor less than the short part of your blade, in the same way as when one draws near a candle when one wishes to remove the light spread about a room, or when the Sun shines its rays through a small aperture and the light expands, it is easier to block the aperture with a hand than to try and stop it with the entire body at a distance when the light has expanded too much. So there is no point in doing otherwise because when one gives a cut the centre of the sword almost remains in the same place, and so is very easy to find and contact, whereas the tip revolves in a large arc, and so swiftly that it would be impossible to attain. From which, we see, again, as before, that the power begins with the beginning of the motion. | + | | class="noline" | C’eſt une obſervation fort generale, & de tresgrande conſequence, que touts mouvements ſont aiſez à ſurmonter en leurs premiers commencements; comme l’experience demonſtre en toutes choſes, qu’il n’y a rien de fort, qui n’ait eſté foible au paravant. Conſiderez en pour example, l’enfance des arbres, des beſtes, & des hommes; la fondation des Villes, des Peuples, & Royaumes; & generalement tous les periodes des choſes, qui augmentent par degrez pour atteindre le comble de leur premiere naiſſance; & combien ſeroit il facile de les y maiſtriſer tout à ſouhait, ſans nulle peine? Et cependent, ſi on le laiſſe, ils ſe renforcent quelques uns ſi avant, qu’il ny reſte pluy moyen de les retenir davantage en bride. Soit une Pierre de Moulin, giſant au ſommet d’une montagne, & qu’elle commence à ſe deſtacher pour rouler de haut en bas; il y a moyen au premier commencement de l’arreſter avec la main ſeule, voire ſouvent avec un doigt ſans plus: ſi elle commence à pancher, encore la peut on retenir avec le corps: mais ſi elle a prinſ ſa courſe, & qu’elle ait deſia donné un tour de haut à bas, qu’elle force d’homme y a il, qui la puiſſe empſcher, moderer, ou divertir, qu’elle n’aille ſon train tout à vau de route? Le meſme en eſt il de ces coups de taille, comme il eſt repreſenté au Cercle N.3. Si vous attendez tant, que le mouvement ſoit venu à deſcendre, tout ce que vous ferez pour l’aſſujettir ſera peine perdue. La force en eſt trop grande. Mais ſi vous prenez le commencement du temps, tout ſera facile. De façon, qu’il n’y a rien à faire, ſinon dreſſer à temps voſtre pointe, comme il faut, pour avoir les lames accouplées tout à l’inſtant qu’il debande la ſienne. Non pas di-je que vous alliez taſter apres, mais qu’il ſoit contraint luy meſme, de frapper au long de la voſtre; & que voſtre aćtion ſoit fondée ſur moins de force, & plus d’adreſſe: Or pour ce faire dreſſez & accouplez voſtre pointe tout joignant le centre de ſa lame; qui eſt le principe & la ſource de toute ſa force. Tellement qu’avoir gagné le Centre, c’eſt luy avoir gagne toute l’eſpee, ne plus ne moins qu’on ſe contente pour le plus court, de tirer la chandelle, quand on veut oſter la lumiere qui reluiſt dedans une chambre, ou quand le Soleil y jette ſes rayons par un petit pertuis, & que la lumiere s’en eſpard ſi largement, qu’il ſeroit plus facile de l’obſcurcir à l’entree du meſme pertuis avec la ſeule main, que de le faire au lieu où la lumiere eſt eſpandu avec le corps tout entier. Auſsi n’y a il point de moyen de faire autrement car pour donner l’eſtramaçon le centre de l’Eſpee demeure quaſi en la meſme place, de façon qu’il eſt beaucoup plus facile à trouver & à prendre, que la pointe, qui fait un grand deſtour & ſi viſte, qu’il ſeroit impoſsible de l’atteindre. Dequoy il appert derechef, comme au paravant, qu’il faut prendre le commencement de la force avec le commencement du temps. |

| − | |||

| − | |C’eſt une obſervation fort generale, & de tresgrande conſequence, que touts mouvements ſont aiſez à ſurmonter en leurs premiers commencements; comme l’experience demonſtre en toutes choſes, qu’il n’y a rien de fort, qui n’ait eſté foible au paravant. Conſiderez en pour example, l’enfance des arbres, des beſtes, & des hommes; la fondation des Villes, des Peuples, & Royaumes; & generalement tous les periodes des choſes, qui augmentent par degrez pour atteindre le comble de leur premiere naiſſance; & combien ſeroit il facile de les y maiſtriſer tout à ſouhait, ſans nulle peine? Et cependent, ſi on le laiſſe, ils ſe renforcent quelques uns ſi avant, qu’il ny reſte pluy moyen de les retenir davantage en bride. Soit une Pierre de Moulin, giſant au ſommet d’une montagne, & qu’elle commence à ſe deſtacher pour rouler de haut en bas; il y a moyen au premier commencement de l’arreſter avec la main ſeule, voire ſouvent avec un doigt ſans plus: ſi elle commence à pancher, encore la peut on retenir avec le corps: mais ſi elle a prinſ ſa courſe, & qu’elle ait deſia donné un tour de haut à bas, qu’elle force d’homme y a il, qui la puiſſe empſcher, moderer, ou divertir, qu’elle n’aille ſon train tout à vau de route? Le meſme en eſt il de ces coups de taille, comme il eſt repreſenté au Cercle N.3. Si vous attendez tant, que le mouvement ſoit venu à deſcendre, tout ce que vous ferez pour l’aſſujettir ſera peine perdue. La force en eſt trop grande. Mais ſi vous prenez le commencement du temps, tout ſera facile. De façon, qu’il n’y a rien à faire, ſinon dreſſer à temps voſtre pointe, comme il faut, pour avoir les lames accouplées tout à l’inſtant qu’il debande la ſienne. Non pas di-je que vous alliez taſter apres, mais qu’il ſoit contraint luy meſme, de frapper au long de la voſtre; & que voſtre aćtion ſoit fondée ſur moins de force, & plus d’adreſſe: Or pour ce faire dreſſez & accouplez voſtre pointe tout joignant le centre de ſa lame; qui eſt le principe & la ſource de toute ſa force. Tellement qu’avoir gagné le Centre, c’eſt luy avoir gagne toute l’eſpee, ne plus ne moins qu’on ſe contente pour le plus court, de tirer la chandelle, quand on veut oſter la lumiere qui reluiſt dedans une chambre, ou quand le Soleil y jette ſes rayons par un petit pertuis, & que la lumiere s’en eſpard ſi largement, qu’il ſeroit plus facile de l’obſcurcir à l’entree du meſme pertuis avec la ſeule main, que de le faire au lieu où la lumiere eſt eſpandu avec le corps tout entier. Auſsi n’y a il point de moyen de faire autrement car pour donner l’eſtramaçon le centre de l’Eſpee demeure quaſi en la meſme place, de façon qu’il eſt beaucoup plus facile à trouver & à prendre, que la pointe, qui fait un grand deſtour & ſi viſte, qu’il ſeroit impoſsible de l’atteindre. Dequoy il appert derechef, comme au paravant, qu’il faut prendre le commencement de la force avec le commencement du temps. | ||

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 00:05, 4 June 2020

| Translation by Bruce G. Hearns |

Transcription by Bruce G. Hearns |

|---|---|

| |

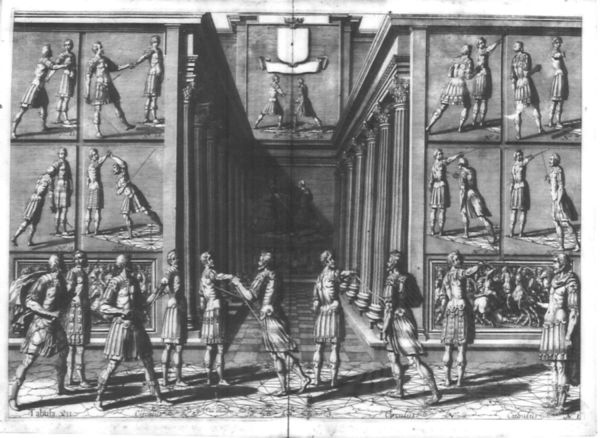

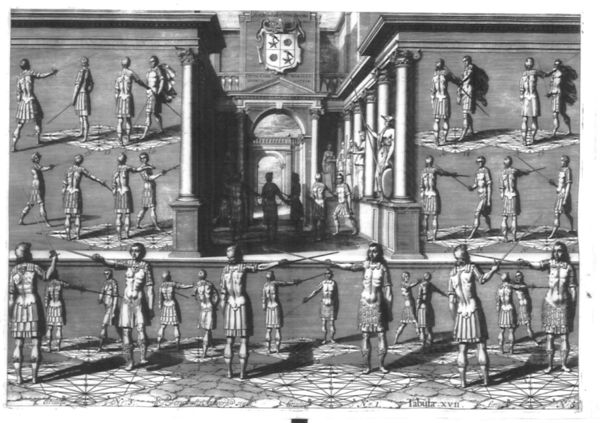

| EXPLANATION OF THE ACTIONS IN THE TWELFTH PLATE. | DECLARATION DES OPERATIONS DV TABLEAV DOUZIEME. |

| We follow here, in this twelfth plate, the example of those who are concerned with fortifications. After they have taught to their students the form of ideal designs, they then briefly show them how, in practice, these must be adapted to the particulars of each place. Moreover, it is impossible to have site exactly one would wish. Thus, we do the same for our System, because we have already explained the manner of entering into the sword-angles, which is one of the points of the greatest importance, we shall now show the versatility of this move and the multiplicity of circumstances in which the scholar can prevail. Such contemplation will be very useful and very easy for them, considering the small number of precepts to keep in mind on which we can build, and which dominate even against the most unusual moves. To do this, we propose to examine a few particular examples, where Zachary opens up the angle in diverse ways, of which none are particularly strange. And in fact he allows opportunities of all sorts. Some ones which consist of a simple defence, others which include attempts to attack. At some times he will completely open up the angle, at other times he will do no more than prepare to. But all with such moves as he hopes will will create confusion by their novelty. But why, then, do this? These situations are useless to learn, because they are so rare, you say? On the contrary, the strangest situations are those that are most necessary to learn. For your enemy will not fail to perform any strange action, if he thinks it will confuse and confound you. Furthermore, whether or not he performs these moves with the same intent and the same follow-on exactly as we show here, nevertheless, you will find yourself often enough in similar situations such as these by chance one way or another. Therefore, be prepared for everything. For in the practice of Arms, after a mistake is made, there is neither valid excuse nor available recovery. | Nous enſuivons en ce Tableau XII. l’exemple de ceux qui traitent les matieres des fortifications. Car apres qu’ils ont enſeigné les figures regulieres, ils ſe contentent de monſtrer briefvement à leurs diſciples, qu’en la Pratique il les faut accommoder ſelon les particularitez de chaſcune place; d’autant qu’il eſt impoſſible de les avoir touſiours à ſouhait. Ainſi donc pour faire le meſme en noſtre Exercice, puis que nous venons de declarer la maniere d’entrer dedans les angles, qui eſt un de points de plus grande importance; monſtrons maintenant combien l’uſage en eſt ample, & comme l’Eſcholier s’en pourra prevaloir en pluſieurs occurrences. Contemplation qui luy ſera tresutil, & tresaggreable, conſiderant que le petit Nombre de ſes preceptes eſt baſtant à tenir en devoir voire & à dompter meſme des mouvements ſi extraordinaires. Pour ce faire nous propoſerons icy quelques particularitez d’exemples, ou Zacharie luy fait l’ouverture de l’angle en diverſes manieres, & aucunes d’icelles bien eſtranges. Et de fait il luy en donne des occaſions de toutes ſortes; les unes qui conſiſtent en ſimple defenſe, les autres conjointes avec intention d’offenſer; tantoſt il ouvre l’angle tout à fait, tantoſt il n’en fait que la ſeule preparation; le tout avec de tels mouvements, qu’il eſpere luy en troubler le jugement par la nouveauté meſme. Mais quoy donc? Direz vous, ce ſont des occaſions inutiles, pour ce qu’elles ſont rares? Au contraire, le plus eſtranges ſe ſont les plus neceſſaires. Car l’Ennemy ne manquera pas à faire une aćtion eſtrange, s’il penſe qu’il vous en mettra en deſordre; & d’autrepart combien qu’il ne les face pas avec la meſme intention, & en la meſme ſuite qu’elles ſont icy repreſentées, toutesfois on ſe retrouve aſſez ſouvent en telles & ſemblables ſituations par les changements des occaſions de part & d’autre. Soyons donc preparez à tout. Car au fait des Armes, apres que la faute eſt commiſe, il n’y a ny remede ny excuſe valable. |

| Circle No 1 | Cercle N.1. |

| Alexander, has subjugated his opponent’s sword at the Second Instance, has stepped with his foot to the Third, in such a way that his left foot is in the process of following along, with the intent to wound his opponent with the length of his blade. At this very moment, Zachary turns his right side to the outside, raising his arm and sword to an obtuse angle above the Inscribed Square X-N, holding it with some force. Alexander sees this, he allows his own tip to rise up, lowering and closing his elbow against his side, and setting his left foot on the ground inside the Quadrangle at the letter O. | Alexandre ayant ſujetté l’eſpee contraire à la Seconde Inſtance, & puis marché avec le pied droit à la Troiſieme, en ſorte que le pied gauche eſt deſia en train à pourſuivre l’autre, avec intention de bleſſer le Contraire au long de ſa lame; en ce meſme temps Zacharie ſe deſtourne le coſté droit en dehors, hauſſant le bras & l’eſpee en angle obtus au deſſus le coſté du Quarré Inſcrit X N, retenant le poids en force. Dequoy s’appercevant Alexandre il laiſſe aller au meſme temps ſa pointe contremont, en abaiſſant & affermiſſant la coude à ſon coſté, & mettant le pied gauche à terre dedans le Quadrangle à la lettre O. |

| After Alexander has subjugated his opponent’s blade moving from the First to the Second Instance along the Diameter at G, and taken a step with his right foot along the side of the Inside Square to the letter N, intending to slide the point of contact up his opponent’s blade to give him a thrust to the face, he draws his left foot along the path following the other. At this time, Zachary turns his toes forward towards the diameter, without leaving his Quadrangle, in such a way that his right side is withdrawn a quarter turn, bringing his extended arm with his sword up into an obtuse angle along the side of Inscribed Square, X-N, with some force, so that the thrust to the face which his adversary had thought to give him is diverted aside. At the same time, Alexander drops his arm and guard down, while his sword-tip comes up, and he closes his elbow against his right side to protect himself, and he sets his left foot down inside the Quadrangle at the letter O, while keeping his body erect. This is shown by the figures. | Apres qu’Alexandre a ſujetté l’eſpee contraire, de la Premiere Inſtance à la Seconde au deça le Diametre lettre G. & ayant conſequemment cheminé avec le pied droit par la trace du Quarré Inſcrit juſqu’à la Troiſieme à la lettre N, pour en graduant l’eſpee contraire luy donner une eſtocade au viſage, dont le pied gauche eſt deſia en train de cheminer apres l’autre : à ce meſme temps Zacharie ſe tourne les orteils en devant vers le Diametre ſans bouger de ſon Quadrangle, en ſorte que le coſté droit du corps s’en retire à quartier, menant le bras eſtendu avec l’eſpee en haut en angle obtus au deſſus le coſté du Quarré Inſcrit X N avec poids de force; de façon que l’eſtocade, que l’adverſaire luy penſoit donner au viſage, en eſt divertie : Au meſme temps Alexandre s’abaiſſe le bras & la garde, & avec la pointe dreſſée contrement il ſe l’affermiſt coſté droit pour defenſe de la partie inferieure de ſa perſonne, mettant enſemblement le pied gauche à terre, dedans e Quadrangle à a lettre O, avec le corps eſtendu; comme les figures demonſtrent. |

| Circle No 2 | Cercle N.2. |

| Alexander raises his right foot in the air, while forcing his opponent’s sword down a little, which (while setting his foot down on the ground before the letter S) he subjugates it, turning his left side forward, and leaning his body even further forward on the same foot inside the angle, while simultaneously drawing his left foot along up to the letter N. | Alexandre eſleveant le pied droit en l’air, abaiſſe enſemble quelque peu l’eſpee de ſon Contraire, laquelle (en plantant le meſme à terre devant la lettre S) il aſſujettit, avançant le coſté gauche, & panchant du corps ſur le devant encores ſur le meſme pied au dedans de l’angle, entrainant quand & quand le pied gauche derriere juſqu’à la lettre N. |

| As soon as Alexander has completed the preceeding action, he pauses briefly, so as to see if his adversary will try to work against him, so he can counter it. But as soon as he sees him waiting, he follows on, moving forward and raising himself with his right foot while lowering the swords with his sense of contact and likewise turning his left side forward, in such a way that the instant his foot lands on the ground in front of the letter S, and his weight comes down on it, he subjugates his opponent’s blade, then leans his body onto the forward foot, drawing his left foot along behind up to the letter N. Thus he puts himself inside the angle of the swords, and inside the lines of his ennemy; As is evident in the portrait of the figures. | Alexandre dés qu’il à parachevé l’aćtion precedente, fait une petite pauſe, afin que ſi l’adverſaire taſche d’avēture à travailler deſſus, il y puiſſe donner order. Mais quand il le voit attendre, il pourſuit, en avançant & hauſſant le corps avec le pied droit, & abaiſſant enſemble un peu les lames au rapport du Sentiment, avec pareil advancement du coſté gauche; en ſorte qu’à l’inſtant que le corps deſcend, & que le pied droit tombe à terre devant la lettre S, il aſſujettit l’eſpee de l’adverſaire, ſe panchant du corps ſur le devant, & entrainant le pied gauche derriere juſqu’au point N. Dont il ſe met par ainſi dedans l’angle, & au dedans des perpendiculaires de l’ennemy; comme il eſt evident au pourtrait des figures. |

| Circle No 3 | Cercle N.3. |

| Alexander continues the movement by leaning further forward, while raising his left hand between them over the swords. Then, he simultaneously moves forward, shifts his weight entirely onto his right foot, raises his left foot, reaches his left hand above the blades to seize the whole of his opponent’s guard and moves his left side leaning still further forward, as we see portrayed in the figure. | Alexandre continuant l’operation encommencée, ſe panche un peu davantage, hauſſant tout d’un temps en avant ſa main gauche entre deux & à l’egal des lames, puis il s’avance quand & quand en ſautant du pied droit, eſlevant en ſuite le pied gauche, & prenant enſemble par deſſus le long des lames la garde du Contraire avec ſa main gauche, le coſté gauche du corps panché encor davantage; ainſi qu’on le voit pourtrait en la figure. |

| Circle No 4 | Cercle N.4. |

| Alexander follows on from the previous movements, stabbing his opponent’s right side with the sword-tip. | Alexandre pourſuit les operations precedentes, donnant à ſon contraire un coup de pointe au coſté droit par le fil de ſa lame. |

| Here the movement carries on, where Alexander suddenly takes his already raised left foot and makes a sudden large circular step outside the Circle, off to the side of his opponent. This he follows with a similar very quick circular move of his right foot, in a volte, taking a large step behind his left foot, he traps his opponent’s sword as he turns his opponent’s hand and pushes the guard away, which creates the opening to stab his opponent’s right side along the line of the blade, as his shown in the figure. | Ceſt encor la continuation du precedent, ou Alexandre pourſuit ſoudainement à faire un grand pas circulaire avec le pied gauche, qui eſtoit deſia eſlevé, au dehors du Cercle à coſté de l’adverſaire; pourſuivant pareillement en cercle avec l’autre pied, aſſavoir le pied droit, qu’il avance & volte de pareille viſteſſe, faiſant un grand pas derriere le pied gauche, pouſſe & tourne cependant le bras & la garde contraire au loing, & luy donne par le fil de la lame un coup de pointe au coſté droit; comme il eſt repreſenté en la figure. |

| Circle No 5 | Cercle N.5. |

| Alexander completes the final execution of the movement by pushing his thrust with full force through his opponent’s body. | Alexandre faiſant la finale execution pouſſe ſon eſtocade au travers le corps de ſon Contraire de pleine force. |

| This is the final follow up to the previous moves, done by Alexander immediately raising his left foot and stepping into his opponent, putting his weight down on it, and thereby pushing his thrust with full force through his opponent’s body. | C’eſt la derniere ſuite de la continuation precedente, fait par Alexandre en eſlevant tout à l’inſtant & avançant le pied gauche devers ſon Contraire, en faiſant la charge du corps deſſus, & luy pouſſant par ainſi l’eſtocade à travers le corps de pleine force. |

| Circle No 6 | Cercle N.6. |

| This action stems from Circle No 1, in the case when his opponent puts more force behind his blade. Thus Alexander continues to work against his opponent, taking a large, deliberate step straight forward with his right foot, moving his body in closer to his sword, and being very attentive to the feel, so to be aware if perchance his opponent comes to change the force he is using and so change the resuting actions as well. | Ceſt aćtion prend ſon origine du Cercle 1. à condition, qu’il y ait plus de poids en la lame contraire. Dont Alexandre pourſuit à travailler, en faiſant un grand pas tout droit en avant lentement avec le pied droit, s’approchant le corps plus pres de ſon eſpee, & prenant fort ſerieuſement garde au ſentiment, ſi daventure le Contraire venoit à changer le poids, pour changer auſſi l’operation. |

| Circle No 7 | Cercle N.7. |

| This continues from the preceeding Circle, where Alexander takes a further large, deliberate step with his left foot, straight forwards, out beside his adversary. After which he raises his right foot and brings it up near to the left one. As he feels that his opponent’s sword still resists with the same degree of force, he turns on the ball of his left foot, to face him. | C’eſt la continuation du precedent, ou Alexandre marche encor un autre grand pas tout droit en avant & lentement avec le pied gauche à coſté de l’adverſaire; pourſuivant apres à eſlever & avancer le pied droit, lequel il joint tout pres de l’autre; & comme il ſent que la lame contraire continue encor au meſme poids, il ſe tourne ſur le pied gauche qui eſt planté tout droit contre luy pour le regarder.

|

| Circle No 8 | Cercle N.8. |

| Alexander carries on the preceeding actions and, entering in towards his opponent, he aims the tip of his blade into his right side, thrusting with full force. | Alexandre pourſuit les operations precedents, & entrant devers le Contraire luy aſſene ſa pointe au coſté droit, l’executant de pleine force. |

| Continuing to feel the same degree of force against his blade, Alexander carries on his actions, disengaging the swords (so the other passes over his head) and at the same instant he enters in towards his opponent with the right foot, which was raised and ready, while aiming his sword-tip at the right side, and then driving it in with full force and his body leaning behind it, in accordance with the figures. | Continuant le meſme Sentiment des lames, Alexandre pourſuit l’operation, en deſtachant les eſpees (dont l’eſpee contraire luy paſſe par deſſus la teſte) & au meſme inſtant il entre devers le Contraire avec le pied droit, qui eſtoit deſia preparé, luy aſſenant la pointe au coſté droit, & l’executant à pleine force avec le corps panché de meſme; le tout en conformité des figures. |

| Circle No 9 | Cercle N.9. |

| Alexander has finished the actions of Circle No 1, and sees his adversary increase the degree of force resisting his blade. After he releases the sword to fly overhead, he wounds his opponent in the right side with his sword-tip. | Alexandre ayant achevé les operations du Cercle 1. voyant que l’adverſaire luy reſiſte en augmentant le poids, apres avoir laiſſé eſchapper l’eſpee contraire il le bleſſe d’un coup de pointe au coſté droit. |

| This is an action which follows from Circles 1 & 2. Alexander has finished the movement in Circle 1. to the point where he has raised his right foot intending to force down and subjugate his opponent’s blade, as in Circle 2. His adversary resists by greatly increasing the degree of force against his blade, enough to move the swords back. To which Alexander lifts his sword from on top, allowing the other to fly freely overhead from the intensity of the force, and at the same time enters in to the angle, by advancing his right foot, which he sets down where the line crosses the segment S-X. He wounds his opponent’s right side by a strike with his sword-tip and finishes the move with his body leaning forward, and left leg drawn up appropriately behind him, as his shown in the figure. | C’eſt icy une operation qui procede en ſuite des Cercles 1. & 2. Alexandre ayant achevé celle du Cercle 1. apres avoir eſlevé le pied droit pour abaiſſer, & conſequemment pour aſſujettir l’eſpee contraire à l’exemple du Cercle 2. l’Adverſaire luy fait reſiſtance, en augmentant le Poids, & uſant de force pour tranſporter les lames. Qui fait qu’Alexandre en oſte ſon eſpee de deſſus, laiſſant enfuir l’autre, qui luy paſſe outre la teſte par la vehemence de la force, & entrant au meſme temps dedans l’angle par advancement du pied droit, qu’il plant à la ſećtion de la ligne S X, il le bleſſe d’un coup de pointe au coſté droit, & en fait la finale execution avec le corps panché en avant, le pied gauche trainant proportionnellement derriere; comme il eſt repreſenté au pourtrait de ſa figure. |

| Circle No 10 | Cercle N.10. |

| Zachary resists by increasing the force against his blade. Alexander slides the point of contact down the blade to prepare the next move. | Zacharie faiſant reſiſtance hauſſant le poids des lames, Alexandre deſgradue les lames & ſe prepare à l’execution ſuivante |

| This action likewise begins from Circle 2, in which Alexander is shown lowering and subjugating his opponent’s blade. Against which Zachary has tried to resist by raising and increasing the force against the blade, however, with a little less than in the previous Circle. So Alexander leans a bit further forward, while making a quick step with his right foot up to the letter S, and with his left hand seizes his opponent’s guard, then slides the point of contact down along the entire length of the blade in such a way that he pulls away as he keeps his grip on the guard, holding it out to the left. He turns his right side forward, raising his left foot, and raises his opponent’s guard up high, while turning the tip of his own blade away behind his back. Thus, he is prepared to perform the following moves, as we can see him making ready in the image. | Ceſte operation prend ſemblablement ſon origine du Cercle 2. auquel Alexandre eſt repreſenté abaiſſant & aſſujettiſſant la lame cōtraire: à quoy Zacharie à voulu faire reſiſtance, en hauſſant & accroiſſant le poids des lames, toutesfois avec un peu moindre effort, qu’au Cercle dernier precedent. Dont Alexandre ſe panche un peu davantage, faiſant au meſme temps avec le pied droit un petit ſaut en avant à la lettre S, & avec la main gauche prend la garde contraire, enluy deſgraduant la lame entier, de ſorte qu’il ſe retire & s’affermit le bras de l’eſpee avec la garde au coſté gauche, en tournant le coſté droit devant avec le pied gauche eſlevé, pouſſant enſemblement ſon bras gauche, qui tient l’eſpee contraire en haut, & conduiſant la pointe de la ſienne contremont par derriere le dos. Voilà comme il s’eſt preparé le corps pour venir conſequemment à l’operation ſuivante; comme on l’y voit tout appreſté en la figure. |

| Circle No 11 | Cercle N.11. |

| This follows on from the last. Alexander, leaps with a large, circular, forward step with his left foot outside the Circle to a point almost behind his adversary, to whom he gives, by leaning forward with his body and bringing his right foot smoothly around through the air in circular motion, setting it down behind the other, a reverse cut to the thick part of his opponent’s left leg, while pressing his opponent’s arm and sword down and pinning them against his left side, as is portrayed in the figure. | C’eſt la ſuite du prēcedent. Alexandre ſaute avec le pied gauche un grand pas circularement en avant au dehors du Cercle à peu pres derriere l’adverſaire; auquel il donne (en panchant du corps ſur le devant, & continuant à mener circulairement le pied droit en l’air derriere l’autre) un coup de revers au gras de la jambe gauche, pouſſant enſemblement vers le bas le bras & l’eſpee contraire, laquelle il s’affermiſt à ſon coſté gauche; ainſi qu’il eſt pourtraićt en la figure. |

| Circle No 12 | Cercle N.12. |

| Alexander continues with the same sequence. He suddenly moves backward and sets his foot down right behind himself, then rocks back onto it, leaning backward and lifing his left foot. As he does, he pulls his opponent’s hand and sword off to his left, and draws his own sword back to his right side, as we see represented in the figure. | C’eſt la continuation de la meſme ſuite, faite par Alexandre, en retirant & plantant ſoudainemēt le pied droit en arriere, ſur lequel il ſe redreſſe & ſe panche à l’envers, en eſlevant le pied gauche, & retirant à ſoy le bras & l’eſpee contraire, meſme auſſi la ſienne, laquelle il conduit à coſté de ſa perſonne à main droite, la pointe tournée vers le bas; comme on le voit repreſenté à la figure. |

| Circle No 13 | Cercle N.13. |

| Here, Alexander executes his strike, and pierces his oppnent with a straight arm through the body. | Alexandre execute icy ſon coup, & perce ſa partie d’un bras roide au travers du corps. |

| And here is the final move. Alexander steps with his left foot forward into his opponent, & leaning his body, he drives his sword, with a straight and extended arm, through his opponent’s body. | En voicy le finale execution. c’eſt qu’Alexandre marche avec le pied gauche deſſus ſon homme, & en panchant le corps de meſme, il luy pouſſe d’un bras roide & eſtendu l’eſpee au travers du corps. |

| Circle No 14 | Cercle N.14. |

| Alexander subjugated his opponent’s sword. Zacharie tries to wound his opponent by disengaging his blade. Alexander perceives this move and swiftly follows, sliding his tip along and again subjugates it. | Alexandre ayant aſſujetti l’eſpee contraire, Zacharie taſche de bleſſer ſa partie en deſtachant ſa lame, Alexandre s’en apercevant le pourſuit vivement & graduant ſa pointe l’aſſujettiſt derechef. |

| Alexander has previously subjugated his opponent’s sword at the Second Instance at the letter G, along the Diameter, according to our precepts and required form. Zachary tries to circularly disengage his blade, which is subjugated underneath the guard, and raise it over Alexander’s, to wound him from above his arm. Alexander feels it is about to disengage, follows it quickly before that can happen, turning it down and outside of the intended path. He does this with his wrist, turning and sliding the point of contact up to the centre of his opponent’s sword, so it cannot escape, at least until the two swords have been raised up at an obtuse angle. Then, with his body upright, he enters in with his left foot forward as he again slides the point of contact up the sword to dominate his opponent’s sword, setting his foot down on the Diameter at the letter Q, bearing the weight of his body on it, over his bent knee, inside the perpendicular lines, as it appears in the figure. | Alexandre ayant preallablement aſſujetti l’eſpee contraire à la Seconde Inſtance lettre G, au deça du Diametre, ſelon les preceptes & en la forme requiſe. Zacharie taſche à luy paſſer circulairement ſa lame, qui eſt aſſujettie par deſſous la garde, pour bleſſer par deſſus le bras. Dont Alexandre, qui recognoiſt au Sentiment, qu’elle commence à ſe vouloir deſtacher de la ſienne, la pourſuit vivement avant qu’elle ſe ſoit delivrée, en tournoyant par le bas & en dehors la meſme chemin q’uelle s’en alloit prendre; ce qu’il fait avec le poignet de la main, tournant & graduant ſa pointe un peu devers le Centre de l’eſpee contraire, afin qu’elle ne luy puiſſe eſchapper, juſqu’à tant que les deux eſpees ſoyent conduites en haut en angle obtus; Lors il entre avec le corps eſtendu, le pied gauche devant, en faiſant derechef deſgraduation en aſſujettiſſant l’eſpee contraire, & plantant le meſme pied au deça le Diametre à la lettre Q, menant la charge du corps deſſus ayant le genoil plié, au dedans des perpendiculaires, ainſi qu’il paroit à la figure. |

| This same action can be done, even if Alexander has not yet done more than set his right foot down at the Second Instance, before his left foot has come into place, and the subjugation of his opponent’s blade is but half done. However, in this latter case, one will not have the leisure to set the left foot down at the Second Instance, before one must increase the size of his step, and move in one up motion to the letter Q, keeping in mind all the same particulars as above. | Ceſte meſme operation ſe pourra pratiquer, moyennant qu’Alexandre n’ait encor planté que le pied droit à la Seconde Inſtance, avant que le gauche y ſoit arrivé, & que l’aſſujettiſſement ne ſoit qu’à demi fait. Toutsfois en ce dernier cas on n’aura pas le loiſir d’aller planter le pied gauche en terre à la Seconde Inſtance, ains il faudra en aggrandir la demarche, & entrer tout d’un train juſqu’à la lettre Q, en obſervant touſiours le meſmes particularitez que deſſus. |

| Circle No 15 | Cercle N.15. |

| This is the follow-on from the preceeding action. Alexander momentarily raises his left foot, making little or no forward motion. He leans on it, moves his left side forward, at the same time disengaging his sword, and seizing hold of his opponent’s guard with his left hand, which he pulls towards himself. He puts the tip of his sword on his adversary’s right side, as the figures demonstrate. | Voicy une ſuite de l’operation precedente. aſſavoir qu’Alexandre eſleve tout à l’inſtant un peu le pied gauche avec peu ou point d’avancement, ſe panchant deſſus, le coſté gauche du corps avancé, en deſtachant au meſme tēps les eſpees, & faiſant prinſe de la garde contraire avec ſa main gauche, laquelle il retire à ſoy, en aſſenant ſa pointe au coſté droit de l’edverſaire; comme les figures demonſtrent. |

| In this action, which proceeds from Circle No 14, where Alexander held his opponent’s blade subjugated with his left foot forward, he follows in Circle No 15 by disengaging the swords while at the same time seizing his opponent’s guard. Note that he could also do the step in with his right foot, and performing the consequent seizure and follow-on without disengaging the blades, as shown in Circles No 2, 3, 4, and 5. | En ceſte opration precedente du Cercle 14, où Alexandre tient l’eſpee contraire aſſujettie avec le pied gauche devant; laquelle il a pourſuivie au Cercle 15. en deſtachant les eſpees, & faiſant au meſme temps prinſe de la garde contraire. Notez qu’il peut auſſi pratiquer la meſme intrade avec le pied droit, en faiſant conſequemment la prinſe avec le ſuite annexées ſans quitter les lames en conformié de ce qui eſt repreſenté es Cercles 2. 3. 4. 5. |

| This is similar to Circle No 2, when Alexander had his right foot forward, but in any case, nothing impedes him from following on as from Circle No 14 disengaging his sword, seizing his opponent’s guard, and giving his a thrust in the stomach, as is shown in Circle No 15. | Semblable eſt du Cercle N.2. combien qu’Alexandre y ait le pied droit devant, toutesfois rien n’empſche qu’il n’en puiſſe auſſi tirer la ſuite du 14. en deſtachant les eſpees, à faire prinſe, & luy preſenter l’eſtocade à la poitrine; comme il eſt monſtré au Cercle N.15. |