|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Fiore de'i Liberi/Mounted Fencing"

| Line 570: | Line 570: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:MS Latin 11269 5r-b.jpg|300px|center | + | | [[File:MS Latin 11269 5r-b.jpg|300px|center]] |

| [[File:MS Ludwig XV 13 45r-b.jpg|300px|center]] | | [[File:MS Ludwig XV 13 45r-b.jpg|300px|center]] | ||

| | | | ||

Revision as of 00:05, 4 February 2016

Images |

Images |

PD |

Morgan Transcription |

Getty Transcription |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[1] I carry my lance in the Boar's Tusk: I carry my lance in Posta di Dente di Cinghiale, because I am well armoured, and therefore I have a shorter lance than my fellow’s, and I manage to rebat his spear out of the path, hence to the traverse or upwards. In this way I will hit his lance with mine, one arm inside with the branch of my staff, and my lance will slide into his ______. And his lance will go out of the path, away from me, and I will do it in this way. [This saying goes to the King hereby.] |

I carry my lance in the Stance of the Wild Boar's Tusk because I am well armored and have a shorter lance than my companion. And so I make my strategy to beat his lance out of the way (so that it is off to one side and not high), and thus I will strike with my lance to his and enter with an arm on my haft, and my lance will run into his person. And his lance will go out of the way far from me, and in such fashion will I do it as is written and depicted here. |

[41r-a] ¶ Io porto mia lanza in posta di dente di cenghiaro per che io son ben armado, e si, o curta lanza piu che lo compagno, e si fazo rasone de rebatter sua lanza fora de strada zoe ala traversa overo in erto. E si firiro cum la mia lanza in la sua, uno brazo in entro cum uno brazo dela mia hasta, E la mia lanza discorrera in la sua persona.[1] E lla sua lanza andara fora di strada lonze de mi e per tal modo faro. |

|||||

|

[3r-b] Io porto mia lanza in posta di dente di zenghiar perche io son bene armado, e si o curta lanza piu che lo compagno. ¶ E si fazo rasone de rebatere la sua lanza fora de strada, zoe ala taiversa[!] e non in erto. E si firiro Cum la mia lanza in la sua uno brazo in entro cum uno brazo dela mia asta. ¶ E la mia lanza discorrera in la sua persona. E lla sua lanza andera fora de strada lonze de mi e per tal modo faro como e dipento e scripto aqui. |

[41r-b] ¶ Questa glosa va al Re di qua. |

[29a-b] Io porto mia lança a'dent de çenchiar |

|||||

|

[2] In the Boar's Tusk I carry my lance; This is the counter of the lance play before, that is, when one runs towards the other with loose stirrups, and one has a shorter lance than the other’s. When the one who has the shorter lance carries his lance low in Dente di Cinghiale, the one with the longer lance has to move it downwards as well, so that the shorter one can not rebat the longer one, as it is drawn here. |

[41r-c] ¶ Questo si'e lo contrario dello zogho de lanza ch'e denançi che quando uno corre contra l'altro a ferri moladi, e uno a corta lança piu che l'altro. Quando quello che a curta lanza porta la sua lanza bassa in dente di cenghiaro quello che a la lanza longa debia simile mente portarla bassa la sua, per che la curta non possa rebattere la longa per lo modo che qui e depento. |

[29a-c] A dent de cenchiar io porto la mia lança |

|||||

|

So that you won't have advantage over me with your lance, [In the Getty, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

This is the counter to the play of the lance which came before, that here one runs against the other with sharp iron and he has a shorter lance than the other. When he that has a short lance carries his low in the Boar's Tusk, he that has the long lance should similarly carry it low in the way which is depicted here, so that the short cannot beat the long. |

[3r-d] Aquesto si e lo contrario dello zogo de lanza ch'e denanzi. Che qui uno corre contra l'altro a ferri amoladi, e uno a curta lanza piu che l'altro. ¶ Quando aquello che a curta lanza la porta la sua bassa in dente de zenghiar, Aquello che ala lanza longa debia similmente portarla bassa la sua, ¶ perche la curta non possa rebater la longa per lo modo ch'e aqui dipento. |

[29a-d] Pero che cum tua lança de mi non habii avantaço |

||||

|

[3] Because of the short lance that I hold, I come in the Stance of the Queen: This is another way of conducting a lance against another. This Master has a short spear and carries it in Posta de Donna la Sinistra, as you can see, to strike back and hit the opponent. |

This is another way to carry the lance. This Master has a short lance and carries it in the Stance of the Queen on the Left as you can see, to beat and then to strike his companion. |

[3v-b] Aquesto e uno altro portar de lanza. Aquesto magistro a curta lanza, e si la porta in posta de dona la sinistra como voii vedite, per rebater, e ferire lo compagno. |

[41v-b] ¶ Questo e un altro portar de lanza contra lanza. Questo magistro a curta Lanza e si la porta in posta de donna la sinistra como voii vedete, per rebatter a ferir lo compagno. |

[29b-b] Per curta lança che io ho in posta de dona vegno |

[2r-d] ¶ En venio retinens muliebrj pectore telum. | ||

|

[4] To waste you or your horse, I make this throw: [In the Getty, the Master on the left is missing his crown.] |

If I throw my lance into the chest of your horse, your beat will fail. And as soon as I've thrown my lance, I will take up the sword for my defense and with your lance you will not do me offense. |

[3v-c] S’io lanzo mia lanza in lo petto dello tuo cavallo, lo tuo rebatere fallo. E subito lanzada mia lanza la spada pigliro per mia defesa. E cum tua lanza non mi faraii offesa. |

[29b-c] Per guastar ti o tuo cavallo faço questo lançar |

||||

|

Again this Master carries his spear in Posta di Donna la Sinistra to strike back the spear the opponent wants to throw at him. And this rebat he wants to perform with a lance could also be done with a stick or a short sword. [In the Pisani-Dossi, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

Again, this Master carries his lance in the Stance of the Queen on the Left to beat the lance that the companion wants to throw. And that beat which he wants to strike with the lance he could also do with a staff or with a sword—except that if he throws his lance into the chest of my horse, my beat will be turned to failure. [In the Morgan, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

[3v-d] Anchora a questo magistro porta la sua lanza in posta di donna sinistra per rebater la lanza che lo[5] compagno gli vole lanzare. E aquello rebatere che lo vol cum la lanza fare, Aquello cum uno bastone o curta spada far lo poria. Salvo che s'ello buta sua lanza in lo peto delo mio cavallo lo mio rebater tornera fallo. |

[41v-d] ¶ Anchora questo magistro porta la sua lanza in posta de donna la sinistra per rebatter la lanza che lo compagno gli vole lanzare. E quello rebatter ch'ello vole cum la lanza fare, quello cum uno bastone o curta spada far lo poria. |

||||

|

[5] Fleeing, I cannot make any other defense This Master who is running away is not armoured, and has a very fast horse, and he always goes thrusting with his lance towards his back to hit the opponent. And if he turned around to the front he could as well enter in Dente di Cinghiale with his lance, or in Posta di Donna la Sinistra, and strike back and finish up, as it can be done, in the first and third play of spear. [In the Pisani-Dossi, the Master is missing his crown.] |

This Master who flees is not armored and is on a running horse, and he is always throwing thrusts with his lance backward to strike his companion. And if he were to turn to the right side he could easily enter into the Boar's Tusk with his lance or into the Stance of the Queen on the Left, and beat and strike as he could do in the first and third plays of the lance [on foot]. |

[4r-b] Aquesto magistro che fuge non e armado, e si e bene a cavallo corrente, e sempre va butando le punte cum la sua lanza deriedo da si, per ferire lo compagno. E s'ello si voltasse della parte dritta ben poria intrar in dente de zenghiar cum sua lanza, overo in posta di donna la sinistra, e rebater, e ferire como si po fare, in lo primo & in lo terzo zogo de lanza. |

[42r-b] ¶ Questo magistro che fuzi non e armado, e si a bon[6] cavallo corente, e sempre va buttando le punte cum la sua lanza dredo de si per ferire lo compagno. E si ello se voltasse dela parte dritta ben poria intrar in dente di zenghiaro cum sua lanza, overo in posta di donna la sinistra, e rebatter e finire come si po far in lo primo e in lo terzo çogho de lanza. |

[30a-b] Fuçando non posso far altra deffesa |

|||

|

[6] I make the counter to your guard, This is the counter to the play before, because this Master lowers his lance to hit the horse in the head or in the chest, and the opponent can not rebat so low with his sword. |

This is the counter to the play that came before. And this Master with the lance carries it low to strike the horse in the head and in the chest, because his companion cannot reach so low with his sword. |

[4r-c] Aquesto si e lo contrario dello zogho ch'e denanci. Che questo magistro cum la lanza la porta bassa per ferire lo cavalo in la testa, o in lo petto, che lo compagno non po rebater cum la spada tanto basso. |

[42v-a] ¶ Questo si'e contrario del zogho ch'e denanzi che questo magistro cum la lanza la porta bassa per ferir lo cavallo, o in la testa, o in lo petto che lo compagno non po rebatter cum la spada tanto basso. |

[30a-c] Lo contrario dela tua guardia io faço |

|||

|

Carrying a sword this way is very good against a lance and very good to strike a lance back riding to the right side of the opponent. And this guard is good against every manual weapon, against axe, stick, sword, et cetera. [In the Getty, the Master on the right is missing his crown. In the Pisani-Dossi, both Masters are missing their crowns.] |

This carry of the sword against the lance is very good for beating the lance while riding to the right side of your companion. And this guard is good against all other handheld weapons—that is, against the ax, the staff, the sword, and so forth. |

[4r-d] Aquesto portar de spada contra lanza e molto fino per rebatere la lanza, cavalcando dela parte dritta delo compagno. E aquesta guardia si e bona contra tute altre arme manuale, zoe contra azza, bastone spada, &c. |

[42r-d] ¶ Questo portar de spada contra lanza e molto fino per rebatter la lança cavalcando dela parte dritta dello compagno. E questa guardia si'e bona contra tutte altre arme manuale, zoe contra Aza, Bastone, spada, & cetera. |

||||

|

[7] With my sword, I will beat your lance, |

This carry of the sword is very fine, and it is called by a name that was said before: I carry my sword in the left Queen's Stance. And if this one comes to me with the lance in rest (to strike me and not my horse), I will beat his lance and I will strike him with my sword without fail. Note that the sword cannot defend below the neck of a horse. |

[4v-b] E aquesto portare di spada e molto fino ch'e ditto denanci che se porta contra lanza come e ditto denanci. Che porto la mia spada in posta donna sinistra. E da questo mi vene cum la lanza in resta per ferirmi, e non el cavallo, rebatero la sua lanza, e cum mia spada lo feriro senza fallo che la spada non po defendere basso per lo collo del cavallo. |

[30b-b] Cum la spada tua lança io rebatero |

||||

|

[8] So that you do not beat my lance out of the way, This is another counter for lance against sword; the one with the lance sets it in rest under his left arm, so that it can not be stricken back. And in this way he will be able to hit the one with the sword with his lance. |

Again this is another counter of lance against sword. He of the lance sets his lance in rest under his left arm so that his lance cannot be beaten aside. And in this fashion he can strike him of the sword with his lance. [In the Morgan, the Master's opponent is wearing a crown.] |

[4v-d] Anchora e aquesto uno altro contrario de lanza contra spada. Che aquello dela lanza, meti e resta sua lanza sotto lo suo brazo stancho perche non sia rebatuda sua lanza. E per tal modo pora ferir cum sua lanza aquello della spada. |

[42v-d] ¶ Questo e un altro contrario de lanza contra spada, che quello dela lanza metti e resta sua lanza sotto lo suo brazo stancho per che non gli sia rebattuda sua lanza. E per tal modo pora ferir cum sua lança quello della spada. |

[30b-d] Perche tu non rebati mia lança fora destrada |

|||

|

[9] At mid-lance thus I come, well enclosed [In the Pisani-Dossi, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

[In the Paris, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

[5r-a] [No text] |

[43r-a] [No text] |

[31a-a] A meça lança io vegno acossi ben asserato |

|||

|

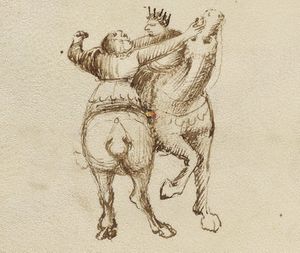

This one with the sword waits for this other one with the lance, and he waits for him in Dente di Cinghiale. As soon as the one with the lance comes close to him, the Master with the sword strikes his lance outwards to the right-hand side. And the one with the sword can do the same, he can cover and hit just in one sword turn. [In the Getty, the Master on the left is missing his crown.] |

This one with the sword awaits him with the lance. He waits in the Boar's Tusk as he with the lance comes, and then the Master with the sword beats his lance away toward the right side. And thus can the Master do with the sword—that is, he can cover in one rotation of the sword. [In the Morgan, the Master on the left is missing his crown.] |

[5r-b] Aquesto cum la spada aspeta aquesto cum la lanza, e si lo aspeta in dente de zenghiare, como aquello cum la lanza gli vene apresso, lo magistro cum la spada rebati sua lanza in fora verso parte dritta. E acosi po far lo magistro cum la spada. ch'ello po covirre[!] in uno voltar de spada. |

[43r-b] ¶ Questo cum la spada spetta questo cum la lanza e si lo spetta cum dente di cenghiaro, Come quello cum la Lanza gli vene apresso, lo magistro cum la spada rebatti sua lanza in fora in verso parte dritta. E chossi po far lo magistro cum la spada, ch'ello po covrir e ferir in un voltar di spada. |

[31a-b] [No text] |

[2v-d] [No text] | ||

|

[10] So that you cannot cross your sword with my [weapon], This is the counter to the play of lance and sword before: the one with the lance hit his enemy horse in the head, because he can not strike the lance back so low with his sword. [In the Pisani-Dossi, the Master is missing his crown.] |

This is the counter of the play of the lance and the sword that came before: that is, that he with the lance strikes to the head of the horse of his enemy (that is, of him with the sword), because he cannot beat a lance or sword which is so low. [In the Morgan, the Master's opponent wears a crown.] |

[5r-c] Aquesto e lo contrario dello zogo de lanza, e spada ch'e denanzi zoe che aquello cum la lanza fieri in la testa lo cavallo del suo inimigo zoe aquello dela spada perché non po rebater la lanza cum la spada si a basso. |

[43r-c] ¶ Questo e lo contrario dello zogho di lanza e de spada ch'e denanzi, çoe che quello cum la lanza fieri in la testa lo cavallo dello suo inimigho, zoe quello della spada, per che non po rebatter la lanza cum la spada si basso. |

[31a-c] Perche cum tua spada cum mi non possi incrosar |

|||

|

[11] Such a carry of the sword gives me four plays to make: Carrying the sword this way is called Posta di Coda Longa, and it is very good against lance, and against any manual weapon, riding on the right-hand side of your enemy. And keep well in mind that thrusts and reverse blows have to be stricken back outwards, that is traversing and not upwards. And in the same way the downwards blows have to be stricken back outwards, rising a little your enemy’s sword. And you can perform the plays according to the drawn figures. |

This carry of the sword is called the Stance of the Long Tail, and it is very good against lance and sword and against all other handheld weapons, while riding to the right side of the enemy. Bear well in mind that the thrusts and the backhand blows should be beaten out to the side and not upward, and the downward blows should also be beaten to the side (lifting the sword of the enemy slightly); [this guard] can make all the plays corresponding to the figures that are depicted. |

[5v-b] Aquesto portar di spada si chiama posta de coda longa e si e molto bona, contra lanza e sp[ada], e contra ogni arma manuale. Cavalcando della parte dritta delo suo iminigo. E tente bene a mente che le punte e li colpi riversi si dibano rebater in fora zoe ala traversa e non in erto. E lli colpi di fendent si dibano rebater anche in fora levando un pocho la spada dello suo inimigo, e po fare gli zoghi segondo le figure depente |

[43v-b] ¶ Questo portar di spada se chiama posta de coda longa, e si e, molto bona contra lanza, e contra ogni arma manuale, cavalcando dela parte dritta dello suo inimigho. E tente ben a mente che le punte e li colpi riversi si debano rebatter in fora, zoe, ala traversa e non in erto. E li colpi de fendenti, si debano rebatter per lo simile in fora, levando un pocho la spada dello suo inimigo, E po fare gli zoghi segondo le figure depente. |

||||

|

[12] Of these two guards I make no comparison; Also, this same guard of Coda Longa is good when someone comes towards you with the sword to the reverse hand side, as this enemy of mine is coming. And you shall know that this guard is good against all the blows coming from the right or the left-hand sides, against anybody who is right or left-handed. And here following the plays of Coda Longa begin, which rebat always in the way told above in the first guard of Coda Longa. [In the Getty, the Master on the left is missing his crown.] |

Again this same Stance of the Long Tail is good when one comes against you with the sword on the left-hand side, as this enemy of mine does, and know that this guard counters all blows from the right side and from the left side, and counters anyone, be they right- or left-handed. And hereafter commence the plays of the Long Tail, which always beats in the fashion that was said earlier in the first Guard of the Long Tail. |

[5v-d] Anchora aquesta propria guardia de coda longa si e bona quando uno gli vene in contra cum la spada a man riversa, come vene questo mio inimigo, e sapia che questa guardia e contra tuti colpi de parte dritta e di parte riversa, e contra zaschuno che sia drito o manzino. E aqui de driedo comenzano gli zoghi de coda longa che sempre rebati per lo modo ch'e ditto denanci in prima guardia de coda longa. |

[43v-d] ¶ Anchora questa propia guardia de choda longa si'e bona quando uno gli vene incontra cum la spada, a man riversa come vene questo mio inimigo. E sapia che questa guardia e contra tutti colpi de parte dritta e di parte riversa, e contra zaschun che sia, o dritto o manzino. E qui dredo cominzano gli zoghi di coda longa che sempre rebatte per lo modo ch'e ditto denanzi in prima guardia de coda longa. |

[31b-c] De queste due guardie io non faço conperacion |

|||

|

[13] This is an equal crossing, without advantage; |

These two Masters are here crossed at the full of the sword. And that which one can do, the other can do also—that is, he can do all the plays of the sword with this crossing. But crossing is of three categories (that is, from the full of the sword to the tip of the sword), and whoever is crossed at the full of the sword can withstand a little, and whoever is crossed at middle of the sword can withstand less, and whoever at the tip of the sword can withstand nothing at all. So the sword, as such, has three matters—that is, a little, less, and nothing. |

[6r-b] Quisti doi magistri sono aqui incrosadi a tuta spada. E zo che po far uno po far l'altro, zoe che po fare tuti zoghi de spada cum lo incrosar. Ma lo incrosar si e de tre rasone, zoe a tuta spada, e punta de spada. E chi e incrosado a tuta spada pocho gle po stare. E chi e incrosado a meza spada meno gle po stare. E chi a punta de spada niente gle po stare. Si che la spada si ha in si tre cose, zoe pocho, meno, e niente. |

[32a-b] Questo e uno ingualivo e sença avantaço incrosar |

||||

|

[14] This point I gladly have set in your throat This is the first play of the guard of Coda Longa which is before, that is, the Master rebats his enemy’s sword and thrusts him in the chest, or in the face, as it is drawn here. |

This is the first play which belongs to the Guard of the Long Tail which appeared here before: that is, that the Master beats the sword of his enemy and thrusts the point into his chest, or into his face as depicted here. [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

|

[44r-a] ¶ Questo e lo primo zogho che esse dela guardia de coda longa ch'e qui denanzi, zoe ch'ello magistro rebatte la spada dello suo inimigo, e mettigli la punta in lo petto, o vole in lo volto come qui depento. |

[32a-a] Questa punta in la golla volentera t'o posta |

|||

|

[15] Per the first Master that is in guard with the sword This is the second play, and to rebat it, I hit this one in the head, as I can see well that his head is not armoured. |

This is the second play which can give a beat. I strike this man over the head, for I see well that he is not armored on his head. [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[6r-c] Aquesto si e lo segondo zogo che puo de quello rebater Io fiero a costui sopra la testa che vezo bene che ello non e armado in la testa. |

[44r-b] ¶ Questo si'e lo segondo zogho ch'e pur di quello rebatter, Io fiero costuii sopra la testa che vezo ben ch'ello non e armado la testa. |

[32a-c] Per lo primo magistro che sta in guardia cum spada |

|||

|

[16] By crossing ahead of your sword I have deviated it This is another play, the third one: once the enemy’s sword has been rebated, he grabs it with his left hand and in this way he hits him in the head, in this way he can hit with a thrust. |

Here is another play, which is the third that beats the sword of his enemy; he grasps with his left hand and strikes the [enemy's] head, and he could also strike thusly with the point. |

[6r-d] Aquesto e uno altro zogo ch'e llo terzo che rebatuda la spada dello suo Inimigo ello la pigla cum la mane stancha e si gle feri la testa e acosi gle poria ferire de punta. |

[44r-c] ¶ Questo e un altro zogho lo terzo, che rebattu da la spada dello suo inimigho, ello la piglia cum la mane stancha, E si gli fieri la testa. e cossi gli poria ferir de punta. |

[32a-d] Per lo incrosar denançi tua spada io o'suariada |

|||

|

[17] You will lose your sword because of this catch This is the fourth play: the student wants to hit him and take his sword in this way you can see drawn here. |

This is the fourth play that the scholar wants to make—that is, take the sword in this way that you can see depicted here. [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[6v-a] Aquesto si e lo quarto zogo che lo scolar gle vole fare zoe tore la spada per questo modo che vuii possite vedere aqui depento. |

[44r-d] ¶ Questo si'e lo quarto zogho che lo scolaro gli vol ferir la testa e tor gli la spada per questo modo che vedete qui depento. |

[32b-a] La tua spada perderaii per questa presa |

|||

|

[18] So that my sword would not be taken from me This is the sixth one, who wants to take the sword off the playfellow. With the hilt of his sword he will raise the other’s hilt high, the sword will certainly fall off his hand. [This Master is missing his crown.] |

This is the fifth play, in which he wants to take the sword of his companion with the hilt of his sword; the other hilt he will have above, and the sword will fall from [his companion's] hand for certain. |

[6v-b] Aquesto si e lo quinto che vol tore la spada al compagno. Cum lo mantenir dela spada, l'altro mantenir lavera in erto. Dela mane gli cadera la spada per certo. |

[44v-b] ¶ Questo si'e lo Sexto che vol tore la spada al compagno. cum lo mantenir dela spada, l'altro mantenir Levera in erto, della mane gli cadera sa[!] spada per certo. |

[32b-b] Perche la mia spada non me sia tolta |

|||

|

[19] From horse to ground it will behoove you to go; This is the fifth play, a counter with a striking back of sword. I will throw my arm at his neck while quickly turning around, I will surely throw him with his sword on the floor. And my contrary, afterwards, is the second play. Although it is not to be done when one is armoured. |

This is the sixth play that makes a cover with the beating of the sword. I throw my arm to his neck and quickly turn, and I will throw you to the ground, sword and all, without a doubt. My counter is here after and is the seventh play. Well that he has not achieved being armored. [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

|

[44v-a] ¶ Questo si'e lo quinto zogho che fa la coverta cum lo rebatter de spada. Io gli butto lo brazzo al collo allo voltar subito, cum tutta la spada in terra lu buttiro senza dubito. E lo mio contrario de dredo si'e lo segondo zogho. Ben che siando armado, di farlo, non a logo. |

[32b-c] Da cavallo in terra te conven andar |

[4r-c] ¶ Expedit ut terram calcato pectore pulses. | ||

|

[20] If it would behoove me to go to the ground, [sword] and all, This is the seventh play, the counter to the fifth one that is the hit that he does to the leg. If the playfellow is armoured, do not trust this play. |

This is the seventh play which is the counter—that is, the strike that he makes to the leg of the other one. If your companion were armored, you could not rely on this. [In the Morgan, the Master is missing his crown.] |

|

[44v-c] ¶ Questo si'e lo Settimo zogho ch'e contrario del quinto. Lo ferir ch'ello gli fa in la gamba a quello e desso. Se lo compagno fossi armado non te infidar in esso. |

[32b-d] Si del tuto in terra me conven andar |

|||

|

[21] I want to make my defense against the point and the edge, This is the eight play, the counter to all the plays before, especially to the mounted with sword plays, and to their Masters who stay in guard of Coda Longa. When the Masters or students stay in this guard, and I perform a thrust or another strike on them, and they strike back immediately, whatever thrust or cut I do, when they strike back, I immediately make my sword turn around, and I hit them in the face with my pommel. And then I step over with my fast cover and with the rounded reverse I hit them behind their heads. |

This is the eighth play and it is the counter to all the plays that came before, and especially of the plays of the sword on horseback and of the Masters that are in the Guard of the Long Tail. And when the Masters or Scholars stand in the aforesaid guard and I strike with a thrust or another blow, and they quickly beat my sword, I immediately give a turn to my sword and with my pommel I strike them in the face. And I can pass with my cover quickly and strike them behind the head with a backhand middle cut. |

[7r-a] Aquesto si e lo ottavo zogo ch'e contrario de tuti li zoghi che mi sono denanci. E maximamente deli zoghi de spada a cavallo, e deli lor magistri che sono in guardia de coda longa. Che quan li magistri, o scolari stano in la ditta guardia e io tra una punta, o altro colpo. E subito elli me rebateno, o taio, o punta che faza. Quando elli me rebateno subito io do volta ala mia spada e cum lo pomo mio io fero in lo volto. E poii passo cum la mia coverta presta. E cum lo riverso tondo gli fero dredo la testa. |

[44v-d] ¶ Questo si'e lo ottavo zogho ch'e contrario di tutti gli zoghi che mi sono denançi. e maxima mente delli zoghi de spada a cavallo, e delli lor magistri che sono in guardia de coda longa. Che quando li magistri, o scolari stano in la ditta guardia, e io gli tro[!] una punta o altro colpo, e subito elli me rebatteno o taglo o punta che faza, Quando elli me rebateno, subito e io do volta ala mia spada, e cum lo pomo mio, io gli fiero in lo volto. E poii passo cum la mia coverta presta e cum lo riverso tondo gli fiero dredo la testa. |

[33a-a] Per punta e taglio voio far mia deffesa |

|||

|

[22] So that you could not hit me in the face with your pommel, I am the ninth and I do against the contrary who is before me. When he makes his sword turn, I immediately put my hilt, as you can see drawn here, because he can not hit me with the pommel to his face. And then I raise my sword high, and I turn the back of the sword around; I can take your sword off you. And if I fail to perform that, I will hit you in the face with the back of my sword, that is I will hit you in the head with the pommel, so fast my twist will be. The mounted plays of sword against sword finish here. Who knows more, shall teach me a good lesson. [This Master is missing his crown.] |

The ninth I am, who makes the counter to that which came before me, so that when he gives a turn to his sword I quickly thrust my hilt (as you see depicted) so that he cannot strike me in the face with his pommel. And if I raise my sword high and give a turn to the left, it could very well be that his sword will be taken from him. And if that fails me and I cannot do it, so quickly will I make the turn that I will give to his face with the false edge of my sword (or I will strike him in the head with my pommel). This finishes the mounted play of sword against sword, and whoever keeps it in mind will give a good deal. |

[7r-b] Lo nono sone che fazo lo contra lo contrario che m'e denanci. Che quando ello da volta ala sua spada, subito lo mio mantenere meto como vuii vedeto depento, che cum lo pomo in lo volto non me po ferire, e s'io levo la spada in erto e dello riverso io piglo volta. Ben poria essere che la spada ti sara tolta. E si aquello mi falla che io non lo faza, dello riverso dela spada ti daro in la faza overo dello pomo ti firiro in la testa tanto faro una volta presta. Aqui finisse lo zogo a cavalo de spada a spada chi piu ne sa men dia una bona derada. |

[45r-a] ¶ Lo nono son che façço contra lo contrario che m'e denançi. Che quando ello da volta ala sua spada subito lo mio mantenir metto, comme voii vedete depento che cum lo pomo in lo volto non me po ferir. E s'io levo la spada in erto, e dello riverso io piglio volta, ben poria esser che la spada ti saria tolta. E si quello mi falla che io non lo faza, dello riverso dela spada ti daro in la faza. Overo delo pomo te feriro in la testa, tanto faro mia volta presta. ¶ Qui finisse lo zogho a cavallo de spada a spada. Chi piu ne sa men dia una bona derada. |

[33a-b] Perche tu non me daghi del pomo in lo volto |

|||

|

[23] In such a way have I grabbed you, running up behind, This is a play of wrestling, that is a play of unarmed combat, and it is to be done in this way: when someone runs away on your left side, you follow him and with your right hand you grab him from the cheeks of his basinet, and if he is not armoured by the neck, or his right arm, or by the back of his shoulders, so to make his fall backwards, and you will make him go to the floor. [In the Getty and Pisani Dossi, the Master is missing his crown.] |

This is a play of grappling, and inasmuch as it is a play of grappling it is a play of the arms, and it is done in this way: when one flees from you and you come up behind him from the left side, grab him on the cheek of his helmet with your right hand (or, if he is unhelmed, grab him by the hair or the right arm from behind his shoulder), and in this way you will make him fall backward such that you will make him go to the ground. [In the Morgan, the Master is missing his crown.] |

[7v-a] Aquesto e zogo de abrazar e tanto, e a dire zogo de abrazar che zogo di braci, e si fa per tal modo. Quando uno te fugi e dela parte stancha tu gli ven apresso Cum la man dritta tu lo pigli in lo sguança dello bacinetto, e s'ello e desarmado per gli cavili, Overo per lo brazo dritto, per dredo le sue spalle, per tal modo lo faraii arivesare, Che in terra lo faraii andare. |

[45r-b] ¶ Questo e zogho de Abrazare zoe zogho de brazi, e si fa per tal modo. Quando uno ti fuzi e dela parte stancha tu gli ven apresso, Cum la man dritta tu lo pigli in le sguanze dello bacinetto, e se ello e disarmado, per gli cavigli, overo per lo brazo dritto per dredo le soy spalle, per tal modo faralo riversare, che in terra lo farai andare. |

[33a-c] Acossi come io t'o preso corandoti dredo |

|||

|

[24] You wanted to throw me from my horse This is the counter to the play before. And it is useful this way: this counter with this hold has to be performed immediately when the other grabs him from behind; he has to change the hand keeping the reins, and grab him this way with his left arm. |

This is the counter to the play that came before; this counter goes in this way with the catch that was made: that is, that quickly when he grabs him from behind, [the Master] should immediately exchange the hand on the reins, and with his left arm he should grab him in this fashion. |

[7v-b] Aquesto e contrario dello zogo che dinanci me va per tal modo aquesto contrario cum tal presa se fa zoe che subito quando ello per dredo lo piglia la man della brigla debia subito scambiare. E cum lo brazo stancho, per tal modo lo de piglare. |

[45r-c] ¶ Questo e contrario del zogho ch'e denanzi ne val per tal modo, questo contrario cum tal presa se fa zoe subito quando ello per dredo lo piglia, La man dela briglia debia subito scambiare, e cum lo brazo stancho per tal modo lo de pigliare. |

[33a-d] Da cavallo me vulisti pur butare |

[5r-c] ¶ Ut modo tellurem calcato corpore tundas | ||

|

[25] I want to lift your leg with the stirrup, This student wants to make this one fall from the horse, he grabs him by the stirrup and rise him high. If he does not go to the floor he will certainly stay in the air. This play can not be failed, except if he is tied to the horse. And if he does not have his foot in the stirrup, he can grab him by the ankle; it works anyway to raise him high. Do what it follows here. [In the Getty, the Master is missing his crown.] |

This Scholar wants to throw this one from his horse—that is, he grabs him by the stirrup and lifts him up. If he doesn't go to the ground, he would clearly be floating in the air! Assuming he isn't lashed to his horse, this play cannot fail. If he does not have his foot in a stirrup, grab him by the ankle and it will be even easier to lift him up than I said before so do as was written here earlier. [In the Morgan, the Master is missing his crown.] |

[7v-c] Aquesto scolar vole butar questo da cavallo zoe che lo pigla per la staffa e levalo in erto. S'ello non va in terra in aere stara per certo. Salvo che se non e a cavallo ligado. Aquesto zogo non po essere falado. S'elo non ha lo pe in la staffa per lo collo del pe lo pigla che piu vale levando in erto come denanci e ditto, fate aquello ch'e denanzi aqui scrito. |

[45r-d] ¶ Questo scolaro vole buttar questo da cavallo çoe ch'ello lo piglia per la staffa e levalo in erto. Se ello non va in terra in aere stara per certo, Salvo s'ello non e[27] al cavallo ligado, questo zogho non po esser fallado. E se ello non a, lo pe in la staffa per lo collo del pe lo piglia che piu vale levandolo in erto come denanzi ditto. Fate quello ch'e denanzi qui scritto. |

[33b-a] La staffa cum la gamba te voio levar |

|||

|

[26] You wanted to throw me well from my horse; The counter to the play before is shown here; if someone grabs you by the stirrup or by the foot, throw your arm around his neck, and he immediately has to do something. And in this way you will cause him dismounting his horse. If you do this, he will certainly go to the floor. |

This here is the counter of the play that appeared before it, so if one grabs you by the stirrup or by the foot, throw your arm to his neck. You should do this quickly, for in this fashion you could dismount him from his horse; if you do this, he will hit the ground without fail. |

[7v-d] Lo contrario aqui del zogo ch'e denanci aparechiado et se uno te pigla per la staffa overo per lo pe, Butagle lo brazo allo collo, aquesto subito far se de. E per tal modo lo porai descavalcare da cavallo. S'tu fai aquesto ello andera per terra senza fallo. |

[45v-a] ¶ Lo contrario del zogho denançi qui e parechiado, che se uno ti piglia per la staffa, overo per lo pe, buttagli lo brazo al collo, e questo subito far si de. E per tal modo lo poraii discavalcare da cavallo. S'tu fa questo ello andera in terra senza fallo. |

[33b-b] De cavallo tu me volisti ben butare |

|||

|

[27] I want to throw you and your horse to the ground; This is a way of throwing someone on the floor with the horse. The remedy of throwing someone on the floor together with his horse has to be done this way: when you are against someone with a horse, ride to his right side. throw your right arm around the horse’s neck, and grab his reins next to the bit which stays in his mouth, and turn it upwards with strength. And make you horse go against the other’s back with his chest. In this way he is forced to go to the floor together with his horse. [In the Getty, the Master is missing his crown.] |

This is a play of throwing one to the ground, horse and all: that is, the Master rides to the right side of his enemy and throws his right arm over the neck of his [enemy's] horse. And he grabs the bridle of his [enemy's] horse behind the bit, rotates the head of the horse up, and he should spur his horse with his foot striking the rump or flanks. And in this way he will fall, horse and all… |

[8r-a] Aquesto e uno zogo de butare uno in terra cum tuto lo cavallo zoe che lo magistro cavalcha dela parte dritta dello suo Inimigo, e buta lo suo brazo dritto per sopra lo collo dello suo cavallo. E pigla la brena delo so cacavallo[!] apresso lo morso, revoltando la testa dello cavallo in erto e llo suo debia speronare che lo suo cavallo cum lo suo petto fiera in gropa overo in gli fianchi del suo cavallo. E per tal modo cadera cum tuto[34] lo cavallo. Lo contrario de questo magistro che vole butare in terra lo suo inimigo cum tuto lo cavallo. Si e aquesto che subito quando lo magistro pigla la sua brena. Che ello debia butare lo brazo al collo per modo che fa lo quarto zugadore che m'e denanci per tal modo andera in terra. |

[45v-b] ¶ Questo si'e un Aito[!] de butar uno in terra cum lo cavallo. Lo rimedio di buttar uno in terra cum tutto lo cavallo per tal modo si fa. Quando tu scontre uno a cavallo. Cavalca dela sua parte dritta. E llo tuo brazo dritto buttalo per sopra lo collo del suo cavallo, e pigla la sua brena a presso lo morso che gli sta in bocha, e rivoltalo in erto per forza. E llo petto del tuo cavallo fa che vada per mezo la groppa del suo cavallo. E per tal modo convene andar in terra cum tutto lo cavallo. |

[33b-c] Ti e'l tuo cavallo per terra voio butar |

|||

|

[28] This is the counter to the play before, which wants to throw the playfellow to the ground together with his horse. This is an easy thing to learn: when the student throws his arm around the horse’s neck to grab the bridle, immediately the player must throw his arm around the student’s neck, and he must leave the hold. It has to be done according to what you see drawn here. |

…This is the counter of the play that came before in which he wants to throw his companion to the ground along with his horse. This is an easy thing to remember, that when the Scholar throws his arm over the neck of his horse to grab the bridle, the player should quickly throw an arm to the neck of the Scholar, and thus he is forced to release it. Following that which you see depicted here, so should you do. |

[45v-c] ¶ Questo si'e lo contrario di questo zogho qui denanzi che vole buttar in terra lo compagno cum tutto lo cavallo. Questa e lizera chosa da cognossere che quando lo scolaro butta lo brazo per sopra lo collo del cavallo per piglar la brena, de subito ello gli de buttar el brazo lo zugador al collo dello scolaro, e per forza ello convien lassar. Segondo vedeti qui depento si debia fare. |

|||||

|

[29] I seek to take the bridle from your hands This is a play of taking the horse’s reins off the playfellow’s hands, in the way you see drawn here. When he fights against someone else on a horse, the student has to ride on his right side, and throw his right arm around the horse’s neck and grabs his reins on the left hand side with his reversed hand. And he must pull the reins off the horse’s head. And this play is safer in armour than not in armour. [In the Getty, the Master is missing his crown.] |

This is a play of taking the bridle of a horse from the hand of your companion in the way that you see depicted here. The Scholar, when he goes against another on horseback, should ride to the right side and throw his right arm over the neck of the horse, grabbing its bridle near his hand on the left-hand side, and so take the bridle off the horse's head. And this play is more secure in armor than unarmored. |

[8r-b] Aquesto e uno zogho de tore la brena dello cavallo dela maane[40] delo compagno per modo che voii vedite aqui dipento, lo scolar quando ello se scontra cum uno altro da cavallo, ello gle cavalcha dela parte dritta, e butagli lo suo brazo dritto per sopra lo collo del cavallo, e pigla la sua brena[41] apresso la sua man sinistra cum la sua man riversa. E tra la brena delo cavallo dela testa. E aquesto zogo e piu seguro armado che disarmado. |

[45v-d] ¶ Questo si'e un zogo di tore la brena delo cavallo de mane del compagno per modo che vedeti qui depento. Lo scolaro quando ello se scontra cum uno altro da cavallo, ello gli cavalca dela parte dritta, e butta gli lo suo brazo dritto per sopra lo collo dello cavallo, e pigla la sua brena apresso la sua man sinestra, cum la sua mane riversa. E tra la brena dela testa del cavallo. E questo zogo e piu siguro armado che disarmado. |

[33b-d] Per tor la brena de mano aquello cercho de far

E dela testa del tuo cavallo la voio tirar E quando la brena sera dela testa tirada A mia posta io te menaro in altra contrada |

|||

|

[30] This Master has lashed a cord to his saddle This Master has tied a strong rope to his horse’s saddle that is one end of it. He has tied the other end to the foot of his lance. First he wants to hit him, then with the lance tied this way to the left side of his enemy, he wants to throw it around his shoulder, so to drag him off the horse. |

This Master has lashed a strong cord (that is, one end) to the saddle of his horse, and the other end is lashed to the foot of his lance. First he wants to strike, and then to put the tied part of the lance to the left of his enemy, throwing it over his shoulder, and thereby to be able to pull him off his horse and onto the ground. |

[2v-a] ¶ Aquesto magistro ha ligada una forte corda alla sella dello suo cavallo, zoe uno cavo, e l'altro cavo si a ligado alo pe della sua lanza primo lo vol ferir e poii la lanza a cosi ligada della parte stancha delo suo inimigo sopra la spalla la vole butar, per poterlo zo dello cavallo strasinare. |

[46v-a] ¶ Questo magistro a ligada una forte corda ala Sella del suo cavallo zoe uno cavo, L'altro cavo sia ligado allo pe dela sua lanza. Primo lo vol ferire, e poii la Lanza chossi ligada della parte stancha dello so inimigo sopra la spalla la vola buttare, per posserlo lo zo del cavallo strassinare. |

[34b-a] Questo magistro si'a ligada una corda ala sella |

|||

|

[31] This bold one was running away towards a fortress. I ran so much that I arrived close to the fortress always riding at full gallop. And I hit him with my sword under the armpit, where no one can be well armoured. And for fear of his friends I want to go back. |

[46v-c] ¶ Questo Ribaldo mi fuziva a una forteza. tanto corsi che io lo zunsi apresso la fortezza sempre corando a tutta brena. E de mia spada lo feri sotto la lasena, Li che male si po l'omo armare. E per paura de soii amisi voglio retornare. |

||||||

|

Here ends the Flower of the Art of Combat, Here finishes the book written by the student Fiore. He has put here what he knows about this art, that is the whole art of fighting is in this book, and Fiore has entitled it Fior di Battaglia. This shall be appreciated by the one who is made for, because nobility and virtue can not be found often. Fiore Friulan, poor old man, commits himself to you. |

Here ends the book that was made by the Scholar Fiore, and all that he knows in this art (that is, the fullness of armizare) he has placed here in this book. And the Flower of Battle he has called this blossom by name. He for whom he has made it shall always be praised, because you will not find his equal in Nobility and virtue. Fiore Furlano, a wretched old man, commends himself to you. |

[46v-d] ¶ Qui finisse lo libro che a fatto lo scolaro Fiore che zo ch'ello sa in quest'arte, qui l'a posto, zoe in tutto la armizare, in questo libro e lo fiore Fior di Bataglia per nome ello e chiamato. Quello per chi ello e fatto sempre sia apresiato che de Nobilita e virtu non se trova Lo parechio, Fior Furlan a voii si recomanda povero vechio. |

[36b-a] Aqui finisse el fior de'l'arte delo armiçar |

[44r-c] ¶ Florius hunc librum quondam pritissimus auctor |

- ↑ The abbreviation ꝑa for "persona" isn't attested in Capelli, but he does list ꝑam for "personam", which is close enough. Morgan has ꝑsona.

- ↑ Nunc/mihi in some order?

- ↑ The second line has been over-written to darken worn-away letters. If there were annotations, they have not survived.

- ↑ This pair of verses has a bracket at the end, which has been posited as indicating enjambment of the lines by Mondschein.

- ↑ Up to this point, the text is partially effaced.

- ↑ Corrected from "e" to "o".

- ↑ Added later: "ego".

- ↑ Added later: "de la pointe".

- ↑ Added later: "remoror [!] jaculum".

- ↑ Added later: "eqqus". Probably meant to be “equus”, but the two q’s are fairly clear.

- ↑ Corrected from "a" to "e".

- ↑ This word was obliterated somehow (“et” and “cesura” both show uncorrected damage) but has been written over by a later hand in similarly-colored ink. Further, someone has tried to write something above it, perhaps a French equivalent—the superscript is unreadable, but the second word, above cuspide, appears to end in “te” and could be “pointe”. The superscript above “acute” may have been in the D1 or F hand, but not enough is clear. There may have been a superscript above mucronem that was erased, although the remaining strokes look like they may have suffered the same damage as the rest of the page. None of the superscripts are clear enough to certainly identify the hands.

- ↑ A bracket, similar to the enjambment bracket, hangs off the last line.

- ↑ "ue" is mostly effaced.

- ↑ Enjambment bracket

- ↑ We believe this is "vulnerare" but the condition of the page has elided an abbreviation mark.

- ↑ There is an erasure above “cervice”, but we were not able to discern any letters.

- ↑ Enjambment bracket

- ↑ Enjambment bracket

- ↑ This paragraph is written with a wedge-shaped gap in the text. This might be a coincidence, or it might indicate that the manuscript being copied had the text flowing around the sword of the player (as is done on the next page), and the scribe assumed that would be the case here as well.

- ↑ This paragraph is partially effaced and hard to read.

- ↑ Added later: "te juc g???et".

- ↑ Added later: "de la poignee".

- ↑ There is no enjambment bracket, but the punctuation and text indicate it.

- ↑ Added later: “??eeu vit”. Could this be “heeume”, misspelling of “heaume”, old french for “helmet”? There are certainly letters beginning above the g in “galea” and reaching to above the e in “prensum”, but we can’t make out enough to guess further. If the latter word is meant to be “heaume”, this must be hand F.

- ↑ Enjambment bracket

- ↑ Literally "ē", which would be read as "en", but in context it seems to make more sense as è, a conjugation of essere.

- ↑ There is a marginal notation to the right of the verse beginning with +. The marginal note seems likely to be hand F, but the + may be from one of the Latin hands. My best guess: ??a??e tram ? perm

- ↑ Enjambment bracket

- ↑ Added later: "pro tui".

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet".

- ↑ or 'Si pargere', but Rebecca says there is a scribal practice for separating the first letter of a line in this manner.

- ↑ Enjambment bracket

- ↑ Corrected from "i"; probably intended to be a "u", but looks like an "a".

- ↑ Added later: "eqquus".

- ↑ Added later: "te mordé de\per bride".

- ↑ According to Cappelli, p. 257

- ↑ Probably laedere

- ↑ Possible scribal flourish

- ↑ Overwritten and difficult to decipher.

- ↑ Written over a previously-effaced word that can't be deciphered.