|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Peloquin"

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox writer | {{Infobox writer | ||

| − | | name = [[name:: | + | | name = [[name::Peloquin]] |

| image = | | image = | ||

| imagesize = | | imagesize = | ||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

| below = | | below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | ''' | + | '''Capitaine Peloquin''' was a [[century::16th century]] [[nationality::French]] soldier and [[fencing master]]. He is described as "one of the four leading fencing masters of France", and his treatise notes that he trained King Henri IV of France in fencing. This likely occurred in the 1570s, giving us an approximate time frame for Peloquin's career. |

Toward the end of the 16th century, Peloquin authored a fencing treatise titled ''Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt'' ("Showcase of Fencing with the Sword and Dagger").<ref>[[Matt Galas]] estimates that it was written in the 1580s or 1590s based on internal evidence.</ref> The only extant copy, current [[Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt (MS KB.73.J.39)|MS KB.73.J.39]], was made by [[J. de La Haye]], a friend of Peloquin's, between 1600 and 1609. Peloquin's treatise is distinctive for its abstract diagrams consisting of floating weapons and feet with lines connecting them to disembodied hearts and faces. | Toward the end of the 16th century, Peloquin authored a fencing treatise titled ''Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt'' ("Showcase of Fencing with the Sword and Dagger").<ref>[[Matt Galas]] estimates that it was written in the 1580s or 1590s based on internal evidence.</ref> The only extant copy, current [[Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt (MS KB.73.J.39)|MS KB.73.J.39]], was made by [[J. de La Haye]], a friend of Peloquin's, between 1600 and 1609. Peloquin's treatise is distinctive for its abstract diagrams consisting of floating weapons and feet with lines connecting them to disembodied hearts and faces. | ||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | [[File:MS KB.73.J.39 01r.jpg|400x400px|center]] |

| − | | <p>'''Practice of Fencing with the Sword and dagger. Once composed by Monsieur Péloquin Captain and one of the four first<ref>An alternative translation of “premier” could be “foremost”.</ref> fencing masters of France.'''</p> | + | | <p>'''Practice of Fencing with the Sword and dagger. Once composed by Monsieur Péloquin, Captain and one of the four first<ref>An alternative translation of “premier” could be “foremost”.</ref> fencing masters of France.'''</p> |

<p><br/></p> | <p><br/></p> | ||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

| <p>Monseigneur,</p> | | <p>Monseigneur,</p> | ||

| − | <p>Out of fear that this small Practice of fencing (which was in times past given to me as a gift by the author) will lose much of its value, not being put to use at all, for having fallen into the hands of one who makes more profession of the feather than of the weapons. Its dignity merits well someone who attach importance to it[: the Captain Péloquin,] being held as one of the bravest swordsmen of France (which I do not say from affection but I assure myself that all those who have known him will give him this same praise), having had</ | + | <p>Out of fear that this small Practice of fencing (which was in times past given to me as a gift by the author) will lose much of its value, not being put to use at all, for having fallen into the hands of one who makes more profession of the feather than of the weapons. Its dignity merits well someone who attach importance to it[: the Captain Péloquin,] being held as one of the bravest swordsmen of France (which I do not say from affection but I assure myself that all those who have known him will give him this same praise), having had the honour in his lifetime to be one of the four first fencing masters in France, and of having trained the king of France, ruling presently, in the weapons, when he was no more yet than the king of Navarre,<ref>This seems to refer to King Henry Ⅳ of France.</ref> and that he had such heart with the weapons that he has acquired an immortal memory through both beautiful victories won with so much fortune as never a king has done. In which, Monseigneur, you follow him very closely, as well in happiness, as in military caution and wise conduct, and I have estimated that is not possible to encounter anyone to whom this small work can be more recommended than to your Eminence. So, I have taken the boldness in the same way, knowing that you take pleasure in it, in daring to present it to you, so that that which a great King has learned from the master himself, your Eminence can learn from this silent master if it delights him. Because your eminence will see a different method here, than that of the masters of it, however without despising anyone. If you think me too presumptuous to thus make a show of another’s work, I can assure well that I have known the author of this book as honest and an admirer of truly Christian Princes. If he was still alive, he would praise my undertaking and he would esteem it a great fortune to see this little work fall in the hands of a Prince as wise and virtuous that God has placed him the weapons in hand to preserve his Church and to defend the freedom of these lands. Therefore receive, Monseigneur, this little orphan, gratefully and under your protection, of a countenance so humane that it is offered to you willingly by he who has no greater ambition than to be able to deserve the fortune that my parents have had, who have confined the most beautiful of their age in the service of the deceased Monseigneur the Prince of Orange, of high memory, your very honoured lord and Father. And I, I would like to be able to do the same. But that which they have done with the weapons, I would like to be able to do that with the feather and the discourse, because my profession is nothing else. If this can happen some day, I will think myself the most fortunate in the world, and still if it is denied me, I will let myself be thought fortunate enough if your Eminence does me this favour of believing that I am and will be all my life.</p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 02r.jpg|2|lbl=02r.2|p=1}} {{paget|Page:MS KB.73.J.39|02v|jpg|p=1}} {{paget|Page:MS KB.73.J.39|03r|jpg|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 03v.jpg|1|lbl=03v.1|p=1}} |

| − | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | Monseigneur | ||

| − | + | your eminence’s | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | very humble and very obedient servant<br/>I. de La Haye.</p> | |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 03v.jpg|2|lbl=03v.2}} |

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

{{master end}} | {{master end}} | ||

| Line 107: | Line 100: | ||

! <p>{{rating|c}}<br/>by [[Reinier van Noort]]</p> | ! <p>{{rating|c}}<br/>by [[Reinier van Noort]]</p> | ||

! <p>[[Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt (MS KB.73.J.39)|Hague Version]]<br/>Transcribed by [[User:ADordor|Aurélien Dordor]]</p> | ! <p>[[Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt (MS KB.73.J.39)|Hague Version]]<br/>Transcribed by [[User:ADordor|Aurélien Dordor]]</p> | ||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 115: | Line 107: | ||

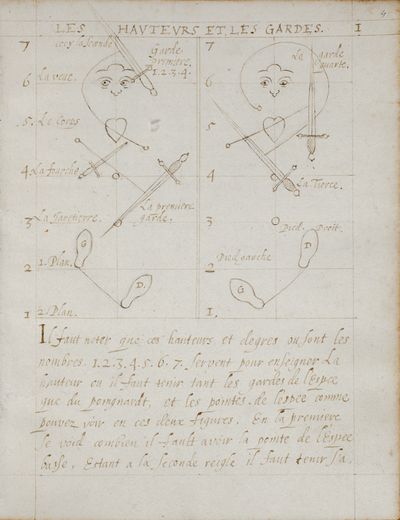

<p>You must note that the elevations and degrees, where there are the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, serve to instruct the elevation where you must hold the guards of both the sword and of the dagger, and the points of the sword, as you can see in these two figures.</p> | <p>You must note that the elevations and degrees, where there are the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, serve to instruct the elevation where you must hold the guards of both the sword and of the dagger, and the points of the sword, as you can see in these two figures.</p> | ||

| − | <p>On the first [figure], you see how low you must have the point of the sword. Being on the second line, you must hold its | + | <p>On the first [figure], you see how low you must have the point of the sword. Being on the second line, you must hold its point at one foot from the ground. Being on the third, at two feet from the ground. And on the fourth, at the height of the crotch. And thus the others following until seven, which is the highest for the cuts.</p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<p>Likewise, the second line in the middle<ref>A little further down in the treatise, after the Riposte from fourth guard, the primes are described as attacks given from close measure where further advancing is not required. The premieres are defined as attacks given whilst advancing into measure. The movements indicated on the four diagrams showing the guard may demonstrate the prime that can be made from each guard.</ref> makes the separation between left and right to involve the guards and points of both the sword and of the dagger, towards your left or towards your right to shut out the sword of your enemy.</p> | <p>Likewise, the second line in the middle<ref>A little further down in the treatise, after the Riposte from fourth guard, the primes are described as attacks given from close measure where further advancing is not required. The premieres are defined as attacks given whilst advancing into measure. The movements indicated on the four diagrams showing the guard may demonstrate the prime that can be made from each guard.</ref> makes the separation between left and right to involve the guards and points of both the sword and of the dagger, towards your left or towards your right to shut out the sword of your enemy.</p> | ||

<p>The feet are governed the same, and at the same heights.</p> | <p>The feet are governed the same, and at the same heights.</p> | ||

| − | | {{paget|Page:MS KB.73.J.39|04v|jpg}} | + | | |

| + | {{paget|Page:MS KB.73.J.39|04r|jpg|p=1}} {{paget|Page:MS KB.73.J.39|04v|jpg|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 180: | Line 168: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 08r.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 08r.jpg|400px|center]] |

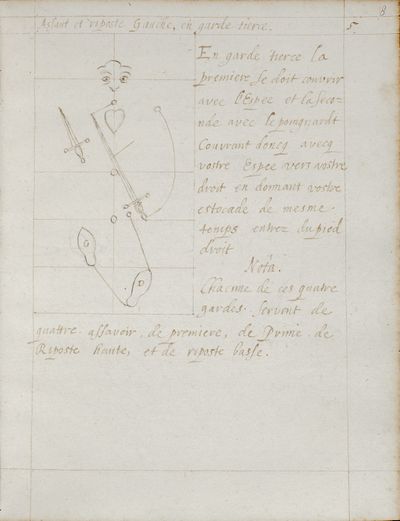

| <p>'''Assault and left riposte in third guard'''</p> | | <p>'''Assault and left riposte in third guard'''</p> | ||

| Line 186: | Line 174: | ||

<p>Giving your thrust, at the same time enter with the right foot.</p> | <p>Giving your thrust, at the same time enter with the right foot.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 08r.jpg|1|lbl=08r.1}} | ||

| − | <p>Nota.</p> | + | |- |

| + | | <p>Nota.</p> | ||

<p>Each of these four guards uses the four, to wit the premiere, the prime, the high riposte and the low riposte.</p> | <p>Each of these four guards uses the four, to wit the premiere, the prime, the high riposte and the low riposte.</p> | ||

| − | | {{ | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 08r.jpg|2|lbl=08r.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 08v.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 08v.jpg|400px|center]] |

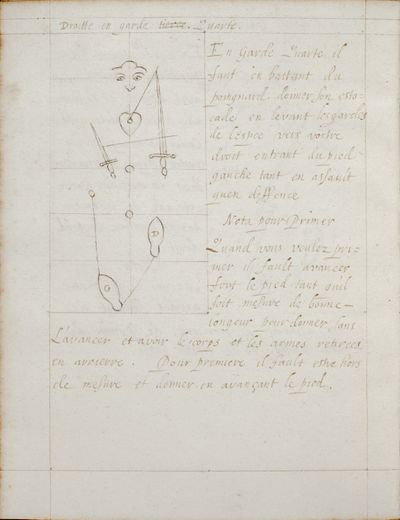

| <p>'''Right in fourth guard'''</p> | | <p>'''Right in fourth guard'''</p> | ||

<p>In fourth guard, you must, while beating with the dagger, give your thrust by raising the guards of the sword towards your right, entering with the left foot, both in assault and in defence.</p> | <p>In fourth guard, you must, while beating with the dagger, give your thrust by raising the guards of the sword towards your right, entering with the left foot, both in assault and in defence.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 08v.jpg|1|lbl=08v.1}} | ||

| − | <p>Nota on giving the prime.</p> | + | |- |

| + | | <p>Nota on giving the prime.</p> | ||

<p>When you want to give the prime, you must advance the foot strongly, until you are at measure of a good length to give, without advancing and have the body and the weapons drawn backwards. For the premiere you must be out of measure and give while advancing the foot.</p> | <p>When you want to give the prime, you must advance the foot strongly, until you are at measure of a good length to give, without advancing and have the body and the weapons drawn backwards. For the premiere you must be out of measure and give while advancing the foot.</p> | ||

| − | | {{ | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 08v.jpg|2|lbl=08v.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 09r.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 09r.jpg|400px|center]] |

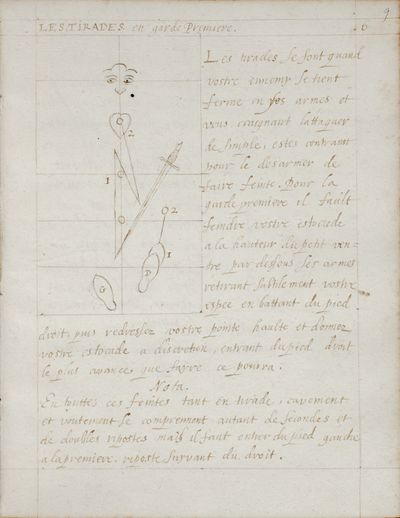

| <p>'''The tirades<ref>The French word “Tirade” seems to indicate a feint performed with a (partial) strike that is quickly drawn back for a second strike to be made to a different target. It is one of the three types of feint described in the treatise, together with a feint by cavade (“Cavement”) and afeint by arching (“voûtement”).</ref> in first guard.'''</p> | | <p>'''The tirades<ref>The French word “Tirade” seems to indicate a feint performed with a (partial) strike that is quickly drawn back for a second strike to be made to a different target. It is one of the three types of feint described in the treatise, together with a feint by cavade (“Cavement”) and afeint by arching (“voûtement”).</ref> in first guard.'''</p> | ||

| Line 212: | Line 204: | ||

<p>Then you straighten up your point high, and give your thrust at discretion, entering with the right foot, advanced as much as you can.</p> | <p>Then you straighten up your point high, and give your thrust at discretion, entering with the right foot, advanced as much as you can.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 09r.jpg|1|lbl=09r.1}} | ||

| − | <p>Nota.</p> | + | |- |

| + | | <p>Nota.</p> | ||

<p>All these feints, by tirade as well as by cavade and by arching,<ref>Voûtement” from ”voûte”, which in turn derives from old French “volte”. Despite the similarity to the Italian term “volta” a blade action is intended here, whereby the blade is curved upwards around the cover placed by the opponent. Instead, “incarter” is used for the volta-like stepping action. This has been translated here as “turning”, as in “turn with the left foot”.</ref> could be used as well as seconds, or as double ripostes, but you must enter with the left foot at the first riposte, following with the right.</p> | <p>All these feints, by tirade as well as by cavade and by arching,<ref>Voûtement” from ”voûte”, which in turn derives from old French “volte”. Despite the similarity to the Italian term “volta” a blade action is intended here, whereby the blade is curved upwards around the cover placed by the opponent. Instead, “incarter” is used for the volta-like stepping action. This has been translated here as “turning”, as in “turn with the left foot”.</ref> could be used as well as seconds, or as double ripostes, but you must enter with the left foot at the first riposte, following with the right.</p> | ||

| − | | {{ | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 09r.jpg|2|lbl=09r.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 09v.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 09v.jpg|400px|center]] |

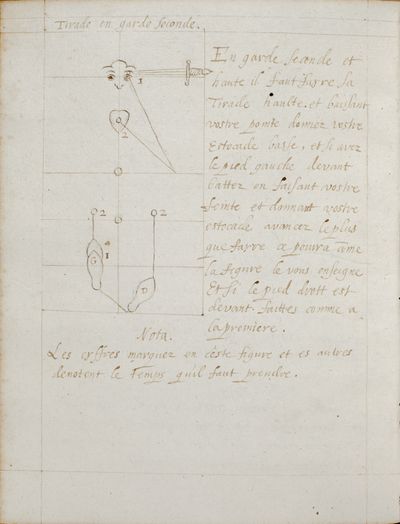

| <p>'''Tirade in second guard.'''</p> | | <p>'''Tirade in second guard.'''</p> | ||

| Line 227: | Line 221: | ||

<p>And if the right foot is in front, do as in the first.<ref>From the context it is not clear what “the first” refers to. Possibilities include the first tirade (i.e. the tirade from first guard) and the simple riposte.</ref></p> | <p>And if the right foot is in front, do as in the first.<ref>From the context it is not clear what “the first” refers to. Possibilities include the first tirade (i.e. the tirade from first guard) and the simple riposte.</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 09v.jpg|1|lbl=09v.1}} | ||

| − | <p>Nota.</p> | + | |- |

| + | | <p>Nota.</p> | ||

<p>The numbers marked in this figure and the others denote the times that you must take.</p> | <p>The numbers marked in this figure and the others denote the times that you must take.</p> | ||

| − | | {{ | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 09v.jpg|2|lbl=09v.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 10r.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 10r.jpg|400px|center]] |

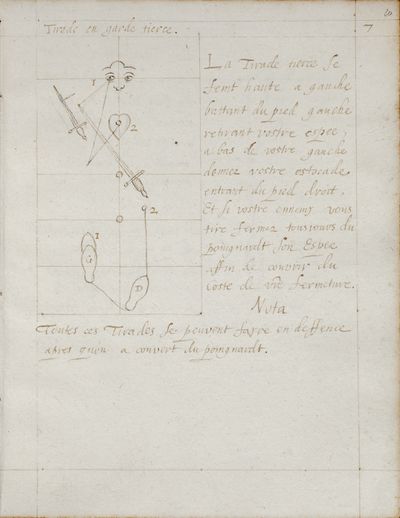

| <p>'''Tirade in third guard.'''</p> | | <p>'''Tirade in third guard.'''</p> | ||

| Line 241: | Line 237: | ||

<p>Give your thrust, entering with the right foot, and if your enemy strikes you, always shut out his sword with your dagger, in order to cover on the side of your | <p>Give your thrust, entering with the right foot, and if your enemy strikes you, always shut out his sword with your dagger, in order to cover on the side of your | ||

closure.</p> | closure.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 10r.jpg|1|lbl=10r.1}} | ||

| − | <p>Nota.</p> | + | |- |

| + | | <p>Nota.</p> | ||

<p>All these tirades can be done in defence, after you have covered with the dagger.</p> | <p>All these tirades can be done in defence, after you have covered with the dagger.</p> | ||

| − | | {{ | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 10r.jpg|2|lbl=10r.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

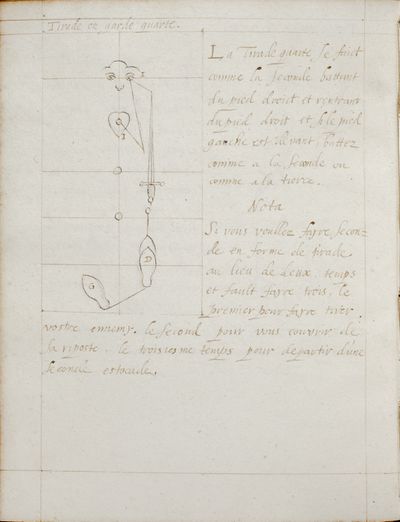

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 10v.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 10v.jpg|400px|center]] |

| <p>'''Tirade in fourth guard.'''</p> | | <p>'''Tirade in fourth guard.'''</p> | ||

<p>The fourth tirade is done like the second tirade, beating with the right foot and going in with the right foot, and if the left foot is in front, beat with the foot as in the second tirade or as in the third tirade.</p> | <p>The fourth tirade is done like the second tirade, beating with the right foot and going in with the right foot, and if the left foot is in front, beat with the foot as in the second tirade or as in the third tirade.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 10v.jpg|1|lbl=10v.1}} | ||

| − | <p>Nota.</p> | + | |- |

| + | | <p>Nota.</p> | ||

<p>If you want to make a second<ref>This most likely refers to using a feint as second as mentioned in the nota after the “Tirade in first guard”.</ref> in the form of a tirade, instead of two times, you must make three: the first to make your enemy strike, the second to cover yourself from his riposte, the third time to depart for a second thrust.</p> | <p>If you want to make a second<ref>This most likely refers to using a feint as second as mentioned in the nota after the “Tirade in first guard”.</ref> in the form of a tirade, instead of two times, you must make three: the first to make your enemy strike, the second to cover yourself from his riposte, the third time to depart for a second thrust.</p> | ||

| − | | {{ | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 10v.jpg|2|lbl=10v.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 275: | Line 275: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 12r.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 12r.jpg|400px|center]] |

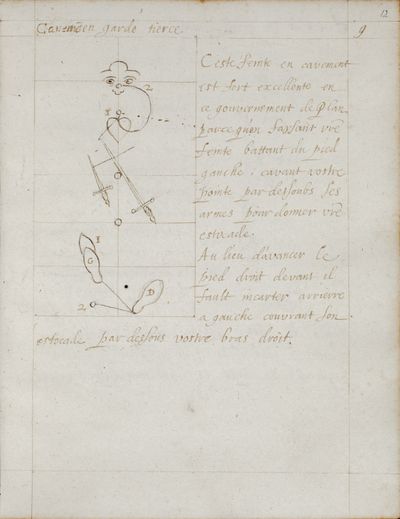

| <p>'''Cavade in third guard.'''</p> | | <p>'''Cavade in third guard.'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This feint by cavade is greatly excellent in this governing of the plan13. Because in making your feint, you beat with the left foot, and disengage your point underneath the weapons to give your thrust. Instead of advancing the right foot in front, you must turn it behind the left, covering his thrust underneath your right arm.</p> | + | <p>This feint by cavade is greatly excellent in this governing of the plan13. Because in making your feint, you beat with the left foot, and disengage your point underneath the weapons to give your thrust.</p> |

| − | | {{ | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 12r.jpg|1|lbl=12r.1}} |

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>Instead of advancing the right foot in front, you must turn it behind the left, covering his thrust underneath your right arm.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 12r.jpg|2|lbl=12r.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 298: | Line 302: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 13v.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 13v.jpg|400px|center]] |

| <p>'''Arching in second guard.'''</p> | | <p>'''Arching in second guard.'''</p> | ||

<p>In second guard, it is done in the same way, except that you must lower the point of your sword to feign your low thrust, to arch afterwards, and to turn with the left foot, conducting all this with discretion.</p> | <p>In second guard, it is done in the same way, except that you must lower the point of your sword to feign your low thrust, to arch afterwards, and to turn with the left foot, conducting all this with discretion.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 13v.jpg|1|lbl=13v.1}} | ||

| − | <p>You can arch on the left as on the right, depending on the coverage of your enemy.</p> | + | |- |

| − | | {{ | + | | <p>You can arch on the left as on the right, depending on the coverage of your enemy.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 13v.jpg|2|lbl=13v.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 14r.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 14r.jpg|400px|center]] |

| <p>'''Arching in third guard.'''</p> | | <p>'''Arching in third guard.'''</p> | ||

<p>In third guard there are three defences, but two principal ones, to wit: of the sword in the first time, and in the second time of the dagger, and in the third time of turning the body with the left foot, and governing the rest as in the preceding.</p> | <p>In third guard there are three defences, but two principal ones, to wit: of the sword in the first time, and in the second time of the dagger, and in the third time of turning the body with the left foot, and governing the rest as in the preceding.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 14r.jpg|1|lbl=14r.1}} | ||

| − | <p>And for the assault, you must beat with the left foot and go in with the right foot while arching and covering with the dagger towards your left. And if you have the right foot in front, you make your arching on your left side, beating with the right foot, and turning with the left.</p> | + | |- |

| − | | {{ | + | | <p>And for the assault, you must beat with the left foot and go in with the right foot while arching and covering with the dagger towards your left. And if you have the right foot in front, you make your arching on your left side, beating with the right foot, and turning with the left.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 14r.jpg|2|lbl=14r.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 346: | Line 354: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 16v.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 16v.jpg|400px|center]] |

| <p>'''Beat in fourth guard.'''</p> | | <p>'''Beat in fourth guard.'''</p> | ||

<p>In fourth guard, you must beat on the inside, your point high, then entering with the right foot, give a thrust, or a reverse or backhand cut over the arms or at your discretion.</p> | <p>In fourth guard, you must beat on the inside, your point high, then entering with the right foot, give a thrust, or a reverse or backhand cut over the arms or at your discretion.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 16v.jpg|1|lbl=16v.1}} | ||

| − | <p>Nota.</p> | + | |- |

| + | | <p>Nota.</p> | ||

<p>You must not start with the foot in the first time, making the beat, but in the second time giving your thrust.</p> | <p>You must not start with the foot in the first time, making the beat, but in the second time giving your thrust.</p> | ||

| − | | {{ | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 16v.jpg|2|lbl=16v.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 384: | Line 394: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 18v.jpg|400px|center]] | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 18v.jpg|400px|center]] |

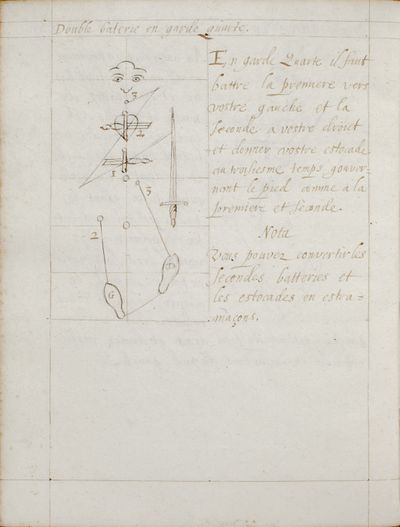

| <p>'''Double beat in fourth guard.'''</p> | | <p>'''Double beat in fourth guard.'''</p> | ||

<p>In fourth guard, you must first beat towards your left and second to your right. And give your thrust in the third time, governing the foot as in the first and second.</p> | <p>In fourth guard, you must first beat towards your left and second to your right. And give your thrust in the third time, governing the foot as in the first and second.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 18v.jpg|1|lbl=18v.1}} | ||

| − | <p>Nota.</p> | + | |- |

| + | | <p>Nota.</p> | ||

<p>You can convert the second beats and the thrusts into cuts.</p> | <p>You can convert the second beats and the thrusts into cuts.</p> | ||

| − | | {{ | + | | {{section|Page:MS KB.73.J.39 18v.jpg|2|lbl=18v.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 515: | Line 527: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 27r.jpg|400px|center]] | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 27r.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| − | | <p>'''Trick of enticement<ref> I.e. an invitation.</ref> in first guard.''' | + | | <p>'''Trick of enticement<ref> I.e. an invitation.</ref> in first guard.'''</p> |

| − | This trick of enticement is done and starts having the feet quite close together, advancing your first [thrust] with the right foot and the body as much as you can.</p> | + | |

| + | <p>This trick of enticement is done and starts having the feet quite close together, advancing your first [thrust] with the right foot and the body as much as you can.</p> | ||

<p>Then drawing back the sword and the right foot backwards, cover his thrust over your right arm, stepping in with a second thrust from below your left arm in the form of a low riposte, with the right foot.</p> | <p>Then drawing back the sword and the right foot backwards, cover his thrust over your right arm, stepping in with a second thrust from below your left arm in the form of a low riposte, with the right foot.</p> | ||

| Line 542: | Line 555: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | [[file:MS KB.73.J.39 28v.jpg|400px|center]] | |

| − | + | | <p>'''Double cavade in fourth guard.'''</p> | |

<p>And for this cavade towards your left, you must be in the perfect fourth guard, which is having the sword and dagger on the right in order to remove your sword and dagger to beat the sword upwards towards your right while disengaging your sword underneath the dagger of your enemy, entering with the right foot.</p> | <p>And for this cavade towards your left, you must be in the perfect fourth guard, which is having the sword and dagger on the right in order to remove your sword and dagger to beat the sword upwards towards your right while disengaging your sword underneath the dagger of your enemy, entering with the right foot.</p> | ||

<p>[The text of the technique simply ends; there is no text denoting the end of the work.]</p> | <p>[The text of the technique simply ends; there is no text denoting the end of the work.]</p> | ||

| − | + | | {{paget|Page:MS KB.73.J.39|28v|jpg}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 576: | Line 589: | ||

{{sourcebox | {{sourcebox | ||

| work = Transcription | | work = Transcription | ||

| − | | authors = | + | | authors = [[Aurélien Dordor]] |

| source link = | | source link = | ||

| source title= [[Index:Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt (MS KB.73.J.39)]] | | source title= [[Index:Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt (MS KB.73.J.39)]] | ||

| Line 585: | Line 598: | ||

== Additional Resources == | == Additional Resources == | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{bibliography}} | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

{{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| − | {{DEFAULTSORT: Peloquin | + | {{DEFAULTSORT: Peloquin}} |

__FORCETOC__ | __FORCETOC__ | ||

Latest revision as of 20:41, 15 June 2025

| Peloquin | |

|---|---|

| Born | 16th Century |

| Died | 17th Century (?) |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Nationality | French |

| Patron | Henri Ⅳ of France |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Middle French |

| Notable work(s) | Cabinet d’Escrime de l’espee et poingnardt |

| Archetype(s) | Currently lost (ca. 1585) |

| Manuscript(s) | MS KB.73.J.39 (1600s) |

| Translations | Alternate English translation |

Capitaine Peloquin was a 16th century French soldier and fencing master. He is described as "one of the four leading fencing masters of France", and his treatise notes that he trained King Henri IV of France in fencing. This likely occurred in the 1570s, giving us an approximate time frame for Peloquin's career.

Toward the end of the 16th century, Peloquin authored a fencing treatise titled Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt ("Showcase of Fencing with the Sword and Dagger").[1] The only extant copy, current MS KB.73.J.39, was made by J. de La Haye, a friend of Peloquin's, between 1600 and 1609. Peloquin's treatise is distinctive for its abstract diagrams consisting of floating weapons and feet with lines connecting them to disembodied hearts and faces.

Contents

Treatise

Illustrations |

Hague Version | |

|---|---|---|

Practice of Fencing with the Sword and dagger. Once composed by Monsieur Péloquin, Captain and one of the four first[2] fencing masters of France. Poverty prevents good minds from succeeding. |

[01r] CABINET D'ESCRIME DE L’espée et poingnardt, composé jadis par Monsieur Peloquin, Capitaine et l'un des quattre premiers maistres d'escrime de France. ~~ Povrete empeche les bons esprits de parvenir. | |

To the very great and very illustrious Prince, Monseigneur the Count Maurice, Prince of Orange, Count of Nassau and of Katzenelnbogen, Marquis of Veere and of Vlissingen, Governor and Captain General of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, etc. |

||

Monseigneur, Out of fear that this small Practice of fencing (which was in times past given to me as a gift by the author) will lose much of its value, not being put to use at all, for having fallen into the hands of one who makes more profession of the feather than of the weapons. Its dignity merits well someone who attach importance to it[: the Captain Péloquin,] being held as one of the bravest swordsmen of France (which I do not say from affection but I assure myself that all those who have known him will give him this same praise), having had the honour in his lifetime to be one of the four first fencing masters in France, and of having trained the king of France, ruling presently, in the weapons, when he was no more yet than the king of Navarre,[4] and that he had such heart with the weapons that he has acquired an immortal memory through both beautiful victories won with so much fortune as never a king has done. In which, Monseigneur, you follow him very closely, as well in happiness, as in military caution and wise conduct, and I have estimated that is not possible to encounter anyone to whom this small work can be more recommended than to your Eminence. So, I have taken the boldness in the same way, knowing that you take pleasure in it, in daring to present it to you, so that that which a great King has learned from the master himself, your Eminence can learn from this silent master if it delights him. Because your eminence will see a different method here, than that of the masters of it, however without despising anyone. If you think me too presumptuous to thus make a show of another’s work, I can assure well that I have known the author of this book as honest and an admirer of truly Christian Princes. If he was still alive, he would praise my undertaking and he would esteem it a great fortune to see this little work fall in the hands of a Prince as wise and virtuous that God has placed him the weapons in hand to preserve his Church and to defend the freedom of these lands. Therefore receive, Monseigneur, this little orphan, gratefully and under your protection, of a countenance so humane that it is offered to you willingly by he who has no greater ambition than to be able to deserve the fortune that my parents have had, who have confined the most beautiful of their age in the service of the deceased Monseigneur the Prince of Orange, of high memory, your very honoured lord and Father. And I, I would like to be able to do the same. But that which they have done with the weapons, I would like to be able to do that with the feather and the discourse, because my profession is nothing else. If this can happen some day, I will think myself the most fortunate in the world, and still if it is denied me, I will let myself be thought fortunate enough if your Eminence does me this favour of believing that I am and will be all my life. |

[02r.2] Monseigneur. De peur que ce petit Cabinet d'escrime (lequel m'a autrefois esté donné en don de L'auteur) ne vient a perdre beaucoup de sa valeur n'estant point mis en usage, pour estre tombé entre les mains d'un qui faict plus profession de la Plume que des Armes, et que sa dignité merite bien quelqu'un qui en face cas, pour estre venu d'un des plus braves espadasins de france, (ce que je ne dis pas par affection mais je m'asseure que tous ceux qui l'ont cognu luy donneront c'este mesme louange) ayant eu [02v] l'honneur en son vivant d'estre l'un des quatre premiers maistres d'escrime de France, et d'avoir dressé aux armes Le Roy de France à présent régnant Lors qu'il n'estoit encores que Roy de Navare, et qu'il avoit tellement le coeur aux armes, qu'il s'en est acquis une mémoire immortelle partant de belles victoires acquises avecq autant d'heur que jamais Roy ait faict. En quoy (Monseigneur) vous le suivez de bien près, tant en bonheur, prudence et militaire, et sage conduitte que j'ay estimé ne pouvoir recontrer personne auquel ce petit labeur peut estre plus recommandé qu'à V.E.[5] En sorte que j'ay prins la hardiesse mesmement sçachant qu'y prenez plaisir de le vous oser présenter, Affin que ce qu'un grand Roy a apprins du maistre mesme, V.E. le puisse apprendre de ce maistre muet s'il luy plaist, car vre[6] E. y verra un autre méthode, que celle des maistres d'éparde ça[7] [03r] sans toutesfois en méspriser aucun, que si on m'estime trop présomptuer de faire ainsy parade du labeur d'autruy, je puis bien asseurer que j'ay cognu l'autheur de ce livre si honneste et amateur des princes vrayement chréstiens, que quand mesmes il seroit en vie, il loueroit mon entreprise et estimeroit à beaucoup d'heur de voir ce petit labeur entre les mains d'un prince si sage et vertueux auquel Dieu a mis les armes en main pour maintenir son Eglise et déffendre la liberté de ces pays. Recevez donc, Monseigneur, ce petit orphelin, en gré et sous vostre protection d'un usage autant humain qu'il vous est offert de bon coeur de celuy qui n'a plus grande ambition que de pouvoir mériter l'heur qu'ont eu mes parens qui ont confinné le plus beau de leur aage au service de feu Monseigneur le Prince d'Orange de haute mémoire vostre très honnoré [03v.1] seigneur et père, et moy je voudrois pouvoir faire le mesme, mais ce qu'ils ont faict avec les armes je voudrois le pouvoir faire avec la plume, et le discours, car ma profession n'est autre. Si ce bien me peut quelque-jour arriver je m'estimeray le plus heureux du monde, et encores qu'il me soit dénié; je ne laisseray de m'estimer assez heureux si V. E. me faict ceste faveur de croire que je suis et seray toutte ma vie | |

|

Monseigneur your eminence’s very humble and very obedient servantI. de La Haye. |

Illustrations |

Hague Version | |

|---|---|---|

The elevations and the guards You must note that the elevations and degrees, where there are the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, serve to instruct the elevation where you must hold the guards of both the sword and of the dagger, and the points of the sword, as you can see in these two figures. On the first [figure], you see how low you must have the point of the sword. Being on the second line, you must hold its point at one foot from the ground. Being on the third, at two feet from the ground. And on the fourth, at the height of the crotch. And thus the others following until seven, which is the highest for the cuts. Likewise, the second line in the middle[8] makes the separation between left and right to involve the guards and points of both the sword and of the dagger, towards your left or towards your right to shut out the sword of your enemy. The feet are governed the same, and at the same heights. |

[04r] LES HAUTEURS ET LES GARDES. Il faut noter que ces hauteurs et degrés où sont les nombres. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. servent pour enseigner la hauteur où il faut tenir tant les gardes de l'espée que du poignardt, et les pointes. de l'espée comme pouvez voir en ces deux figures. En la première se void combien il fault avoir la pointe de l'espée basse, estant a la seconde reigle il faut tenir sa [04v] pointe à ung pied près de terre ; estant à la troisièsme à deux pieds près de terre ; et à la quatrièsme à la hauteur de la fourche, et ainsy des autres ensuyvants jusques à sept, qui est la plus haute pour les estramaçons, comme à la seconde reigle du mitant[9] faict la séparation du gauche au droict pour faire participer les gardes, ou pointes tant de l'eséee que du poingnardt, vers vostre gauche ou vers vostre droit, pour fermer l'espée de vostre ennemy. Les pieds se gouvernent de mesme, et aux mesmes hauteurs. | |

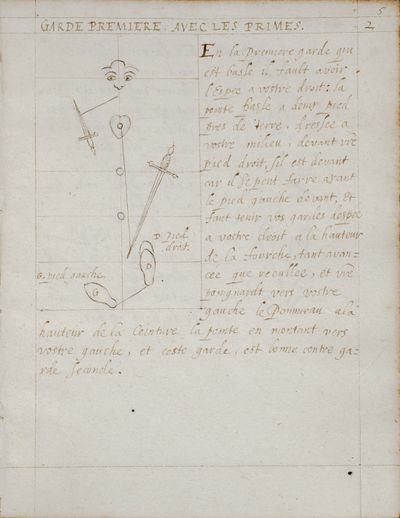

First guard with the primes In the first guard, which is low, you must have the sword at your right, the point low at a half foot from the ground, held in your middle in front of your right foot, if it[10] is in front, because you can make this having the left foot in front. And you must hold your guards of the sword at your right at the height of the crotch, as advanced as withdrawn, and your dagger towards your left, the pommel at the height of the belt, the point upwards towards your left. This guard is good against the second guard. |

[05r] GARDE PREMIERE. AVEC LES PRIMES. En la première garde qui est basse il fault avoir l'espée à vostre droit : la pointe basse à demy pied près de terre, dressée à vostre milieu, devant vostre pied droit, s'il est devant car il se peut fayre ayant le pied gauche devant, et faut tenir vos gardes d'espée à vostre droit à la hauteur de la fourche, tant avancée que recullée, et vostre poingnardt vers vostre gauche le pommeau à la hauteur de la ceinture, la pointe en montant vers vostre gauche et ceste garde est bonne contre garde seconde. | |

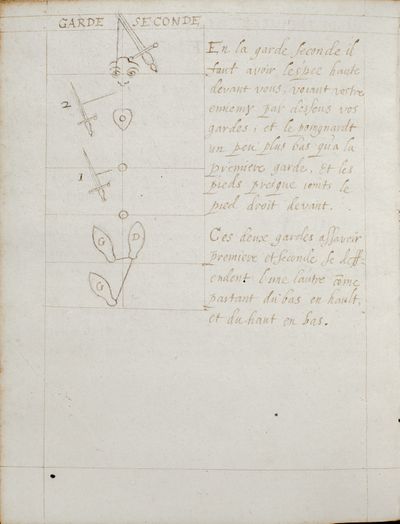

Second guard. In the second guard, you must have the sword high in front of you, watching your enemy underneath your guards, and the dagger a little lower than in the first guard, and the feet almost joined, the right foot in front. These two guards, to wit the first and the second, defend against each other, as starting from low to high, and from high to low. |

[05v] GARDE SECONDE. En la garde seconde il faut avoir l'espée haute devant vous, voiant vostre ennemy par dessous vos gardes, et le poingnardt un peu plus bas qu'à la première garde, et les pieds presque joints le pied droit devant. Ces deux gardes assavoir première et seconde se déffendent l'une l'autre comme partant du bas en hault, et du haut en bas. | |

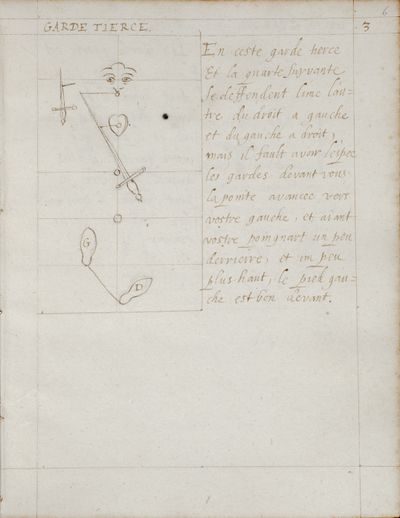

Third guard This third guard and the following fourth defend against each other, from right to left and from left to right. You must have the sword with the guards in front of you, the point advanced towards your left, and having your dagger a little back and a little higher. The left foot is good in front. |

[06r] GARDE TIERCE. En ceste garde tierce et la quarte suyvante se déffendent l'une l'autre du droit à gauche et du gauche à droit, mais il fault avoir l'espée les gardes devant vous, la pointe avancée vers vostre gauche, et aiant vostre poingnart un peu derrièrre, et un peu plus haut, le pied gauche est bon devant. | |

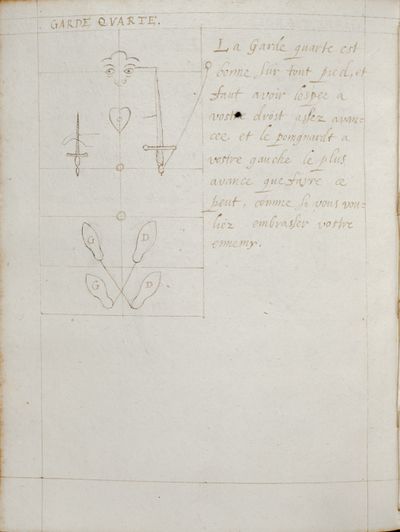

Fourth guard The fourth guard is good on either foot. You must have the sword at your right quite advanced, and the dagger at your left as much advanced as it can be, as if you want to embrace your enemy. |

[06v] GARDE QUARTE. La garde quarte est bonne sur tout pied, et faut avoir l'espée à vostre droit assez avancée et le poingnardt à vostre gauche le plus avancé que fayre ce peut, comme si vous vouliez embrasser vostre ennemy. | |

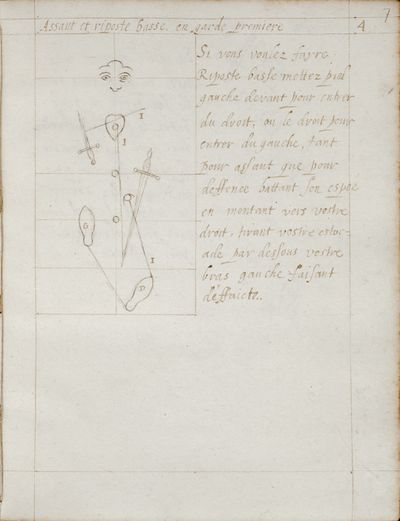

Assault and low riposte in first guard If you want to make a low riposte, place the left foot in front to enter with the right, or the right in front to enter with the left, both for assault and for defence beating the sword of the enemy upwards towards your right, striking your thrust from below your left arm, voiding.[11] |

[07r] Assaut et riposte basse. En garde premiere. Si vous voulez fayre riposte basse mettez pied gauche devant pour entrer du droit, ou le droit pour entrer du gauche, tant pour assaut que pour déffence battant son espée en montant vers vostre droit, tirant vostre estocade par dessous vostre bras gauche faisant d'effaicte[12]. | |

High in the second guard If your enemy strikes you, or if he lowers his sword to the engagement, beat it with your dagger below your right arm, letting the point of your sword drop where you want to give, entering the right foot, both for assault and for defence. |

[07v] Haute. En garde Seconde. Si vostre ennemy vous tire ou qu'il vous baille son espée en prise, battez-la par dessous vostre bras droit laissant tomber la pointe de vostre espée où vous voulez donner en entrant du pied droit tant pour assaut que pour déffence. | |

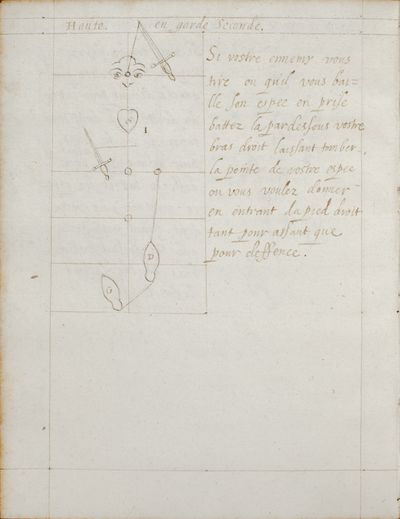

Assault and left riposte in third guard In third guard, the first must cover with the sword and the second with the dagger,[13] and second with the dagger, thus covering with your sword towards your right. Giving your thrust, at the same time enter with the right foot. |

[08r.1] Assaut et riposte. Gauche, en garde tierce. En garde tierce la première se doit couvrir avec l'Espée et la seconde avec le poingnardt couvrant doncq avecq vostre espée vers vostre droit en donnant vostre esctocade, de mesme temps, entrez du pied droit. | |

Nota. Each of these four guards uses the four, to wit the premiere, the prime, the high riposte and the low riposte. |

[08r.2] Nota. Chacune de ces quatre gardes servent de quattre, assavoir, de première, de Prime, de Riposte haute et de riposte basse. | |

Right in fourth guard In fourth guard, you must, while beating with the dagger, give your thrust by raising the guards of the sword towards your right, entering with the left foot, both in assault and in defence. |

[08v.1] Droitte en garde tierce Quarte. En garde quarte il faut en battant du poingnard donner son estocade en levant les gardes de l'espée vers vostre droit entrant du pied gauche tant en assault qu'en déffence. | |

Nota on giving the prime. When you want to give the prime, you must advance the foot strongly, until you are at measure of a good length to give, without advancing and have the body and the weapons drawn backwards. For the premiere you must be out of measure and give while advancing the foot. |

[08v.2] Nota pour primer Quand vous voulez primer il fault avancer fort le pied tant qu'il soit mesure de bonne longeur pour donner sans l'avancer et avoir le corps et les armes retirées en arrièrre. Pour première il fault estre hors de mesure et donner en avançant le pied. | |

The tirades[14] in first guard. The tirades are done when your enemy stands firm with his weapons and you, being afraid of attacking him with a simple [attack], are compelled to disorder him by making a feint. From the first guard, you must feint your thrust at the height of the belly, underneath his weapons, drawing your sword back subtly while beating the right foot. Then you straighten up your point high, and give your thrust at discretion, entering with the right foot, advanced as much as you can. |

[09r.1] LES TIRADES en garde Première. Les tirades se font quand vostre ennemy se tient ferme en ses armes et vous craignant l'attaquer de simple, estes contraint pour le désarmer de faire feinte. Pour la garde première il fault feindre vostre estocade à la hauteur du petit ventre par dessous ses armes retirant subtilement vostre espée en battant du pied droit, puis redressez vostre pointe haulte et donnez vostre estocade à discrétion, entrant du pied droit le plus avancé que fayre ce pourra. | |

Nota. All these feints, by tirade as well as by cavade and by arching,[15] could be used as well as seconds, or as double ripostes, but you must enter with the left foot at the first riposte, following with the right. |

[09r.2] Nota. En touttes ces feintes tant en tirade, cavement et voûtement se comprennent autant de secondes et de doubles ripostes mais il faut entrer du pied gauche à la première riposte suyvant du droit. | |

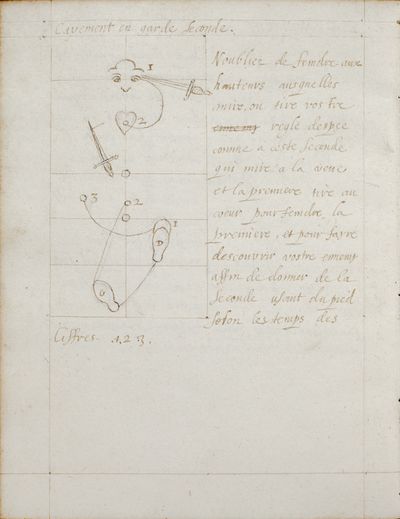

Tirade in second guard. In second and high guard, you must make your tirade high, and lowering your point, give your thrust low. If you have the left foot in front, beat [with the foot] while making your feint, and while giving your thrust advance as much as you can, as the figure instructs you. And if the right foot is in front, do as in the first.[16] |

[09v.1] Tirade en garde seconde. En garde seconde et haute il faut fayre sa tirade haulte et baissant vostre pointe donnez vostre estocade basse, et si avez le pied gauche devant battez en faisant vostre feinte et donnant vostre estocade avancez le plus que fayre ce pourra comme la figure le vous enseigne. Et si le pied droit est devant faittes comme à la première. | |

Nota. The numbers marked in this figure and the others denote the times that you must take. |

[09v.2] Nota. Les cyffres marquéz en ceste figure et ès autres dénotent le temps qu'il faut prendre. | |

Tirade in third guard. The third tirade is feigned high to the left, beating with the left foot drawing back your sword down to your left. Give your thrust, entering with the right foot, and if your enemy strikes you, always shut out his sword with your dagger, in order to cover on the side of your closure. |

[10r.1] Tirade en garde tierce. La tirade tierce se feint haute à gauche battant du pied gauche retirant vostre espée, à bas de vostre gauche donnez vostre estocade entrant du pied droit, et si vostre ennemy vous tire fermez tousjours du poingnardt son espée affin de couvrir du costé de vostre fermeture. | |

Nota. All these tirades can be done in defence, after you have covered with the dagger. |

[10r.2] Nota Toutes ces tirades se peuvent fayre en déffence après qu'on a couvert du poingnardt. | |

Tirade in fourth guard. The fourth tirade is done like the second tirade, beating with the right foot and going in with the right foot, and if the left foot is in front, beat with the foot as in the second tirade or as in the third tirade. |

[10v.1] Tirade en garde quarte. La tirade quarte se faict comme la seconde battant du pied droit et rentrant du pied droit et si le pied gauche est devant, battez comme à la seconde ou comme à la tierce. | |

Nota. If you want to make a second[17] in the form of a tirade, instead of two times, you must make three: the first to make your enemy strike, the second to cover yourself from his riposte, the third time to depart for a second thrust. |

[10v.2] Nota Si vous voullez fayre seconde en forme de tirade au lieu de deux temps et fault fayre trois, le premier pour fayre tirer vostre ennemy, le second pour vous couvrir de sa riposte, le troisièsme temps pour départir d'une seconde estocade. | |

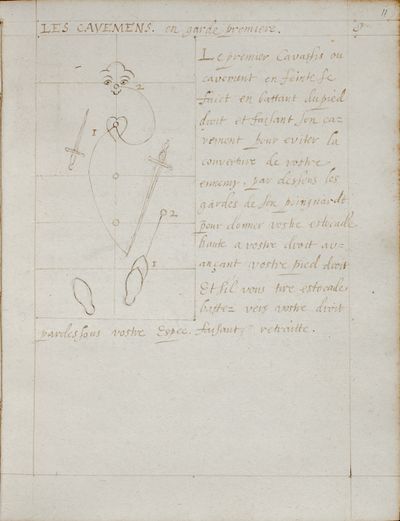

The cavades in first guard. The first cavazione or cavade in feint is made by beating with the right foot and lowering your cavade to avoid the cover of your enemy, underneath the guards of his dagger to give your high thrust on your right advancing your right foot. And if he strikes you a thrust, beat [with the dagger] towards your right below your sword, voiding.[18] |

[11r] LES CAVEMENS. En garde première. Le premier cavassis ou cavement en feinte se faict en battant du pied droit et faisant son cavement pour éviter la couverture de vostre ennemy, par dessous les gardes de son poingnardt pour donner vostre estocade haute à vostre droit avançant vostre pied droit et s'il vous tire estocade, battez vers vostre droit par dessous vostre espée faisant retraitte. | |

Cavade in second guard. Do not forget to feign at the heights at which you aim or draw your line of the sword as in this second which aims at the eyes and the first [guard] [which] strikes at the heart, to feign the first and to uncover your enemy to give the second using the foot according to the times of the numbers 1, 2, 3. |

[11v] Cavement en garde Seconde. N'oubliez de feindre aux hauteurs ausquelles mire, ou tire vostre | |

Cavade in third guard. This feint by cavade is greatly excellent in this governing of the plan13. Because in making your feint, you beat with the left foot, and disengage your point underneath the weapons to give your thrust. |

[12r.1] Cavement en garde tierce. Ceste feinte en cavement est fort excellente en ce gouvernement de plan parce qu'en faysant vostre feinte battant du pied gauche, cavant vostre pointe par dessoubs ses armes pour donner vostre estocade. | |

Instead of advancing the right foot in front, you must turn it behind the left, covering his thrust underneath your right arm. |

[12r.2] Au lieu d'avancer le pied droit devant il fault incarter arrièrre à gauche couvrant son estocade par dessous vostre bras droit. | |

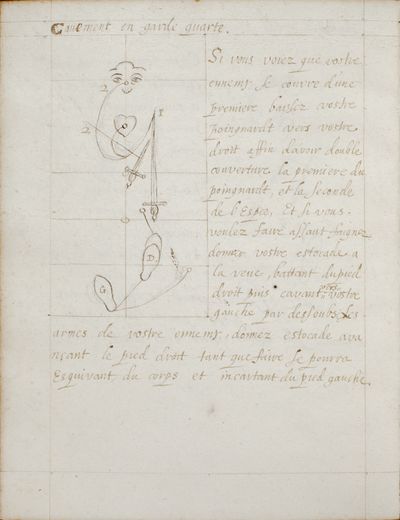

Cavade in fourth guard. If you see that your enemy covers himself with a first [guard], lower your dagger towards your right to have double cover: the first with the dagger and the second with the sword. And if you want to make an assault, feign to give your thrust at the eyes, beating with the right foot then disengaging towards your left underneath the weapons of your enemy, give the thrust while advancing the right foot as far as you can, evading with the body and turning with the left foot. |

[12v] Cavement en garde quarte. Si vous voiez que vostre ennemy se couvre d'une première, baissez vostre poingnardt vers vostre droit affin d'avoir double couverture la première du poingnardt, et la seconde de l'espée, et si vous voulez faire assaut faignez donner vostre estocade à la veüe, battant du pied droit puis cavant vers vostre gauche par dessoubs les armes de vostre ennemy, donnez estocade avançant le pied droit tant que faire se pourra esquivant du corps et incartant du pied gauche. | |

Archings in first guard. After having feigned your thrust under the left armpit of your enemy, where he can only cover to your right, after having beat with the right foot entering with this one, arch with the guard and the point, and give your thrust while arching high to your right, shutting out his sword in the place where it is with the dagger, with which you will cover that part where he will strike you. |

[13r] VOUTEMENTS. En garde première. Les voûtements. Après avoir feint vostre estocade souz l'aisselle gauche de vostre ennemy où il ne peut couvrir qu'à vostre droit après avoir battu du pied droit rentrant d'iceluy, voûtez de garde et de pointe, et donnez vostre estocade en voûtant hault à vostre droit fermant son espée en quelque endroit qu'elle soit avecq le poingnardt duquel vous couvrirez selon le quartier dont il vous tirera. | |

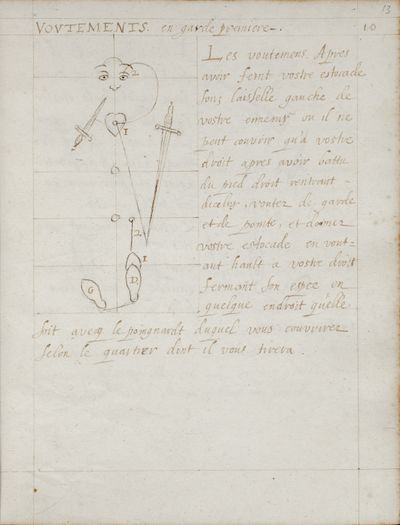

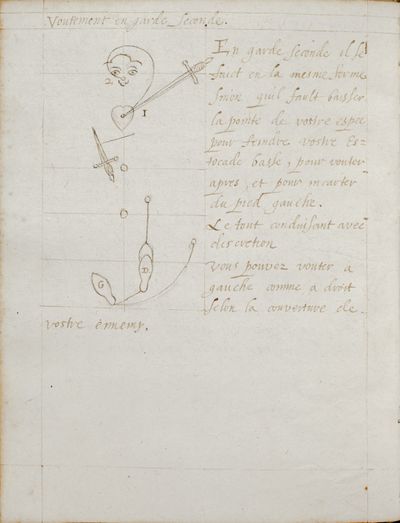

Arching in second guard. In second guard, it is done in the same way, except that you must lower the point of your sword to feign your low thrust, to arch afterwards, and to turn with the left foot, conducting all this with discretion. |

[13v.1] Voûtement en garde seconde. En garde seconde il se faict en la mesme forme sinon qu'il fault baisser la pointe de vostre espée pour feindre vostre estocade basse, pour voûter après, et pour incarter du pied gauche. Le tout conduisant avec discrétion | |

You can arch on the left as on the right, depending on the coverage of your enemy. |

[13v.2] Vous pouvez voûter à gauche comme à droit selon la couverture de vostre ennemy. | |

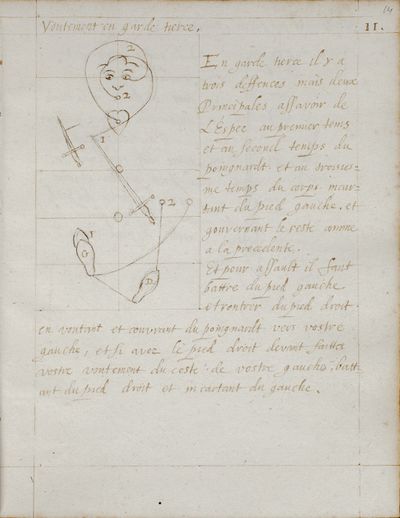

Arching in third guard. In third guard there are three defences, but two principal ones, to wit: of the sword in the first time, and in the second time of the dagger, and in the third time of turning the body with the left foot, and governing the rest as in the preceding. |

[14r.1] Voûtement en garde tierce. En garde tierce il y a trois déffences mais deux principales assavoir de l'espée au premier tems et au second temps du poingnardt. Et au troisièsme temps du corps incartant du pied du pied gauche. Et gouvernant le reste comme à la précédente. | |

And for the assault, you must beat with the left foot and go in with the right foot while arching and covering with the dagger towards your left. And if you have the right foot in front, you make your arching on your left side, beating with the right foot, and turning with the left. |

[14r.2] Et pour assault il faut battre du pied gauche et rentrer du pied droit en voûtant et couvrant du poingnardt vers vostre gauche, et si avez le pied droit devant faittes vostre voûtement du costé de vostre gauche, battant du pied droit et incartant du gauche. | |

Arching in fourth guard. The fourth guard is similar, except that it starts from the right and the third on the left. It is better on the right foot, and the third is better on the left foot. And instead of turning with the left foot, you must make a retreat with the right foot. |

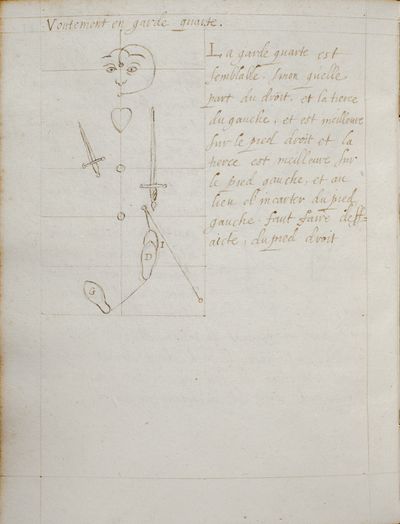

[14v] Voûtement en garde quarte. La garde quarte est semblable, sinon qu'elle part du droit, et la tierce du gauche, et est meilleure sur le pied droit et la tierce est meilleure sur le pied gauche, et au lieu d'incarter du pied gauche, faut faire d'effaicte du pied droit. | |

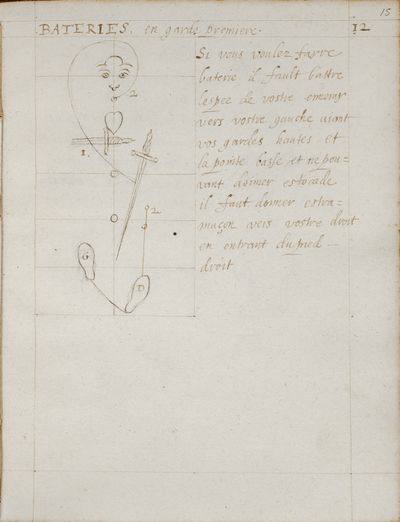

Beats in first guard. If you want to make a beat, you must beat the sword of your enemy towards your left having your guards high and the point low. And not being able to give a thrust, you must give a cut towards your right while entering with the right foot. |

[15r] BATERIES, en garde première. Si vous voulez fayre baterie il fault battre l'espée de vostre ennemy vers vostre gauche aiant vos gardes hautes et la pointe basse et ne pouvant donner estocade il faut donner estramaçon vers vostre droit en entrant du pied droit. | |

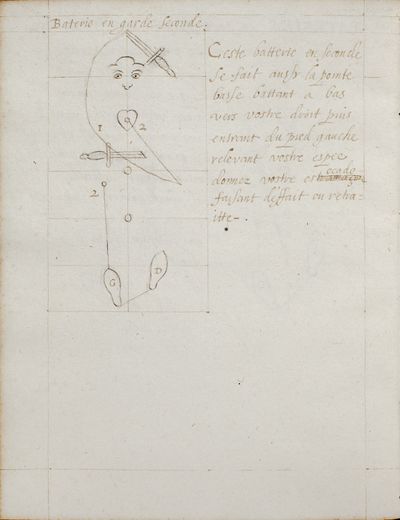

Beat in second guard. This beat in second is also done with the point low, beating down towards your right, then entering with the left foot raising your sword, you give your thrust, voiding or making a retreat.[19] |

[15v] Baterie en garde seconde. Ceste batterie en seconde se fait aussy la pointe basse battant à bas vers vostre droit puis entrant du pied gauche relevant vostre espée donnez vostre estocadetramaçon es faisant d'effait ou retraitte | |

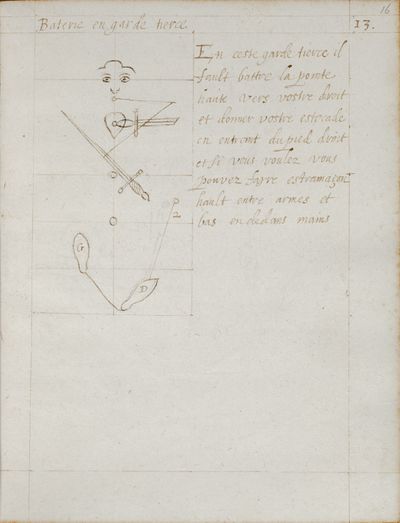

Beat in third guard. In this third guard, you must beat [with] the point high towards your right, and give your thrust while entering with the right foot. And if you want you can make a high cut between the weapons and low inside the hands. |

[16r] Baterie en garde tierce. En ceste garde tierce il fault battre la pointe haute vers vostre droit et donner vostre estocade en entrant du pied droit et si vous voulez vous pouvez fayre estramaçon hault entre armes et bas en dedans mains. | |

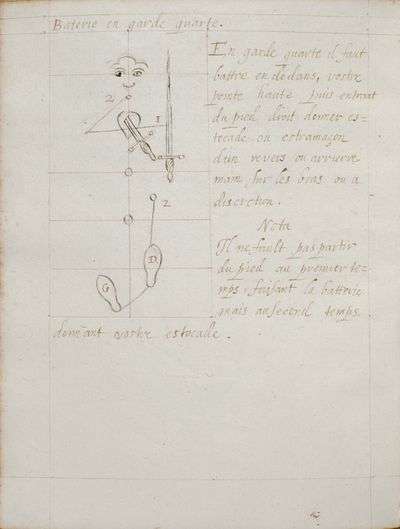

Beat in fourth guard. In fourth guard, you must beat on the inside, your point high, then entering with the right foot, give a thrust, or a reverse or backhand cut over the arms or at your discretion. |

[16v.1] Baterie en garde quarte. En garde quarte il faut battre en dedans, vostre pointe haute puis entrant du pied droit donner estocade ou estramaçon d'un revers ou arrièrre main sur les bras ou à discrétion. | |

Nota. You must not start with the foot in the first time, making the beat, but in the second time giving your thrust. |

[16v.2] Nota Il ne fault pas partir du pied au premier temps faisant la batterie mais au second temps donnant vostre estocade. | |

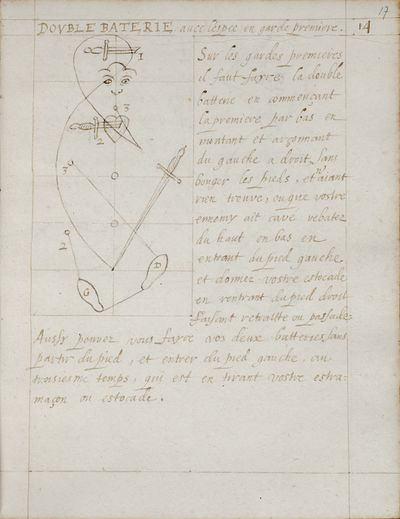

Double beat with the sword in first guard. Out of the first guards, you must make the double beat by beginning the first from below by rising and curving from left to right, without moving the feet. And having found nothing, or if your enemy has disengaged, beat again from high to low while entering with the left foot, and give your thrust while going in with the right foot, making a withdrawal or a passade. Also, you can make your two beats without moving your feet, and enter with the left foot in the third time, which is while striking your cut or thrust. |

[17r] DOUBLE BATERIE. Avec l'espée en garde première. Sur les gardes premières il faut fayre la double batterie en commençant la première par bas en montant et arçonnant du gauche à droit, sans bouger les pieds, et n'aiant rien trouvé, ou que vostre ennemy ait cavé rebatez du haut en bas en entrant du pied gauche et donnez vostre estocade en rentrant du pied droit faisant retraitte ou passade.Aussy pouvez-vous fayre vos deux batteries sans partir du pied, et entrer du pied gauche au troisièsme temps, qui est en tirant vostre estramaçon ou estocade. | |

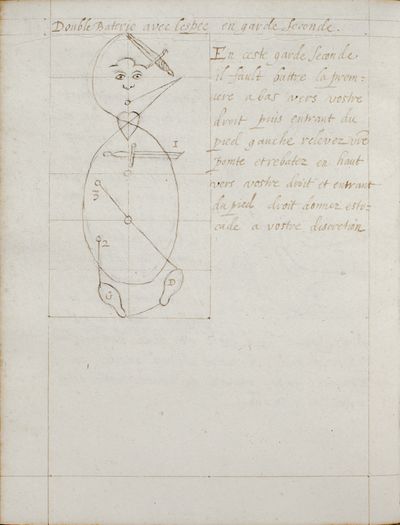

Double beat with the sword in second guard. In this second guard, you must first beat down towards your right, then entering with the left foot, raise your point and beat again upwards towards your right. And entering with your right foot, give a thrust at your discretion. |

[17v] Double Baterie avec l'espée en garde seconde. En ceste garde seconde il fault battre la première à bas vers vostre droit puis entrant du pied gauche relevez vostre pointe et rebatez en haut vers vostre droit et entrant du pied droit donnez estocade à vostre discrétion. | |

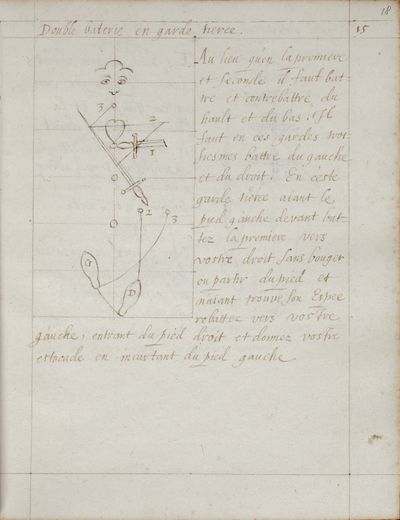

Double beat in third guard. Whereas in the first and second [guards] you must beat and counterbeat from high and from low, in these third [and fourth] guards, you must beat from the left and from the right. In this third guard having the left foot in front, first beat towards your right without moving or moving away the feet, and not having found his sword, beat again towards your left, entering with the right foot and give your thrust while turning with the left foot. |

[18r] Double baterie en garde tierce. Au lieu qu'en la première et seconde il faut battre et contrebattre du hault et du bas. Il faut en ces gardes troisièsmes battre du gauche et du droit. En ceste garde tierce aiant le pied gauche devant battez la première vers vostre droit sans bouger ou partir du pied et n'aiant trouvé son espée rebattez vers vostre gauche, entrant du pied droit et donnez vostre estocade en incartant du pied gauche. | |

Double beat in fourth guard. In fourth guard, you must first beat towards your left and second to your right. And give your thrust in the third time, governing the foot as in the first and second. |

[18v.1] Double baterie en garde quarte. En garde quarte il faut battre la première vers vostre gauche et la seconde à vostre droict et donner vostre estocade au troisièsme temps gouvernant le pied comme à la première et seconde. | |

Nota. You can convert the second beats and the thrusts into cuts. |

[18v.2] Nota Vous pouvez convertir les secondes batteries et les estocades en estramaçons. | |

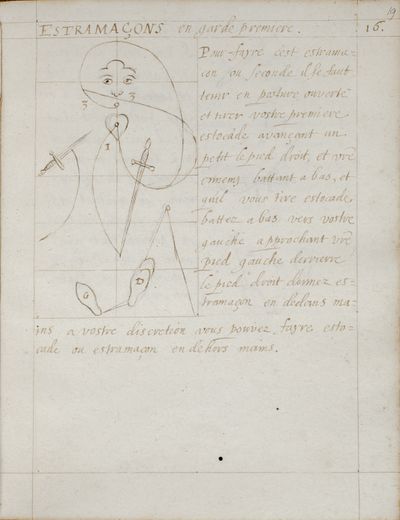

Cut in first guard. To make this cut or second,[20] you must stand in an open posture and strike your first thrust advancing the right foot a little. And your enemy beating down, and as he strikes you a thrust, beat down towards your left approaching with your left foot behind the right foot, give a cut inside the hands. At your discretion, you can make a thrust or a cut outside the hands. |

[19r] ESTRAMAÇONS en garde première. Pour fayre c'est estramaçon ou seconde il se faut tenir en posture ouverte et tirer vostre première estocade avançant un petit le pied droit, et vostre ennemy battant à bas, et qu'il vous tire estocade. Battez à bas vers vostre gauche approchant vostre pied gauche derrièrre le pied droit donnez estramaçon en dedans mains à vostre dicrétion vous pouvez fayre estocade ou estramaçon en dehors mains. | |

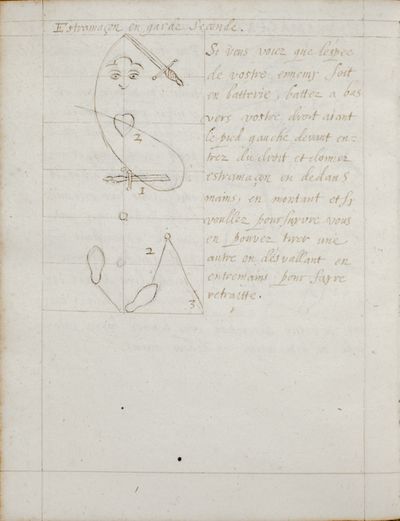

Cut in second guard. If you see that the sword of your enemy is in a beat,[21] beat down towards your right having the left foot in front, enter with the right and give a rising cut inside the hands. And if you want to continue, you can strike another rushing down in between the hands, to make a withdrawal. |

[19v] Estramaçon en garde seconde. Si vous voiez que l'espée de vostre ennemy soit en batterie, battez à bas vers vostre droit aiant le pied gauche devant, entrez du droit et donnez estramaçon en dedans mains, en montant et sy voullez poursuyvre vous en pouvez tirer une autre en désvallant en entremains pour fayre retraitte. | |

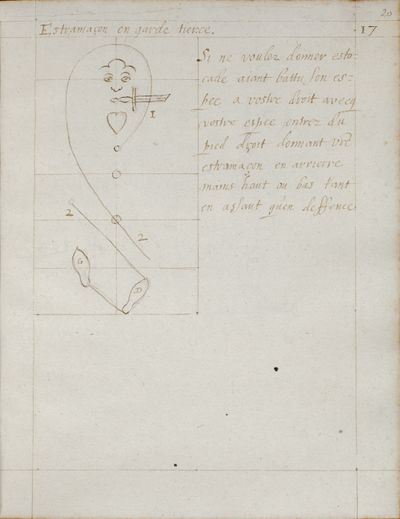

Cut in third guard. If you do not want to give a thrust having beat his sword to your right with your sword, enter with the right foot, giving your backhand cut high or low, both in assault and in defence. |

[20r] Estramaçon en garde tierce. Si ne voulez donner estocade aiant battu son espée à vostre droit avecq vostre espée, entrez du pied droit donnant vostre estramaçon en arrièrre mains haut ou bas tant en assaut qu'en déffence. | |

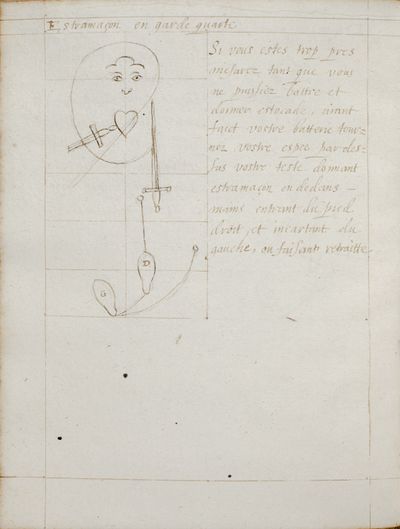

Cut in fourth guard. If you are at very close measure, so that you cannot beat and give a thrust, having done your beat, turn your sword over your head giving a cut between the hands, entering with the right foot, and turning with the left, or making a retreat. |

[20v] Estramaçon en garde quarte. Si vous estes trop près, mesurez tant que vous ne puissiez battre et donner estocade, aiant faict vostre batterie tournez vostre espée par dessus vostre teste donnant estramaçon en dedans mains entrant du pied droit, et incartant du gauche ou faisant retraitte. | |

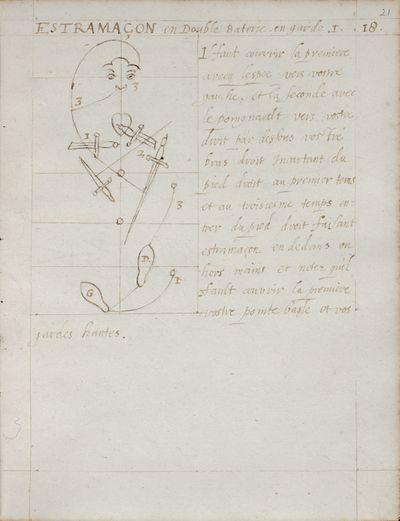

Cut with double beat in first guard. You must cover the first with the sword towards your left, and the second with the dagger towards your right underneath your right arm, turning with the left foot in the first time. And in the third time, enter with the right foot, making a cut within or outside the arms. Note that you must cover the first with your point low and your guards high. |

[21r] ESTRAMAÇON en double baterie. En garde I.[22] Il faut couvrir la première avecq l'espée vers vostre gauche, et la seconde avec le poingnardt vers vostre droit par dessous vostre bras droit incartant du pied droit au premier tems et au troisièsme temps entrer du pied droit faisant estramaçon en dedans ou hors mains et notez qu'il fault couvrir la première vostre pointe basse et vos gardes hautes. | |

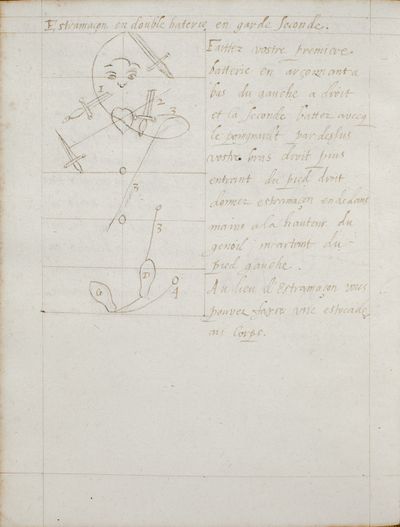

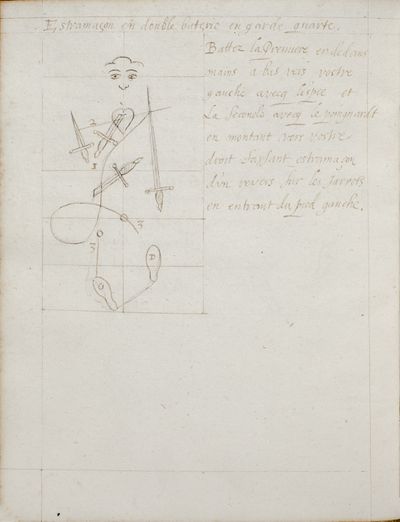

Cut with double beat in second guard. Make your first beat by curving downwards from left to right, and the second beat, beat with the dagger over your right arm. Then, entering with the right foot, give a cut within the hands, at the height of the knee, turning with the left foot. Instead of a cut you can make a thrust to the body. |

[21v] Estramaçon en double baterie en garde seconde. Faittez vostre première batterie en arçonnant à bas du gauche à droit et la seconde battez avecq le poingnardt par dessus vostre bras droit puis entrant du pied droit donnez estramaçon en dedans mains à la hauteur du genoil[23] incartant du pied gauche. Au lieu d'estramaçon vous pouvez fayre une estocade au corps. | |

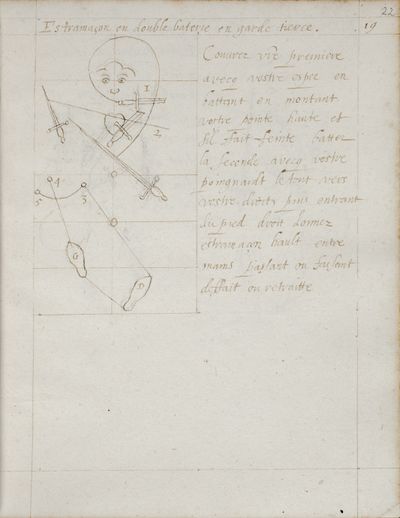

Cut with double beat in third guard. Cover your first with your sword beating upwards, your point high. And if he feigns, beat the second with your dagger, all to the right. Then, entering with the right foot, give a high cut between the hands, passing or voiding or making a retreat. |

[22r] Estramaçon en double baterie en garde tierce. Couvrez vostre première avecq vostre espée en battant en montant vostre pointe haute et s'il fait feinte battez la seconde avecq vostre poingnardt le tout vers vostre droit, puis entrant du pied droit donnez estramaçon hault entre mains passant ou faisant d'effait ou retraitte. | |

Cut with double beat in fourth guard. Beat the first within the hands, down towards your left with the sword and the second with the dagger upwards towards your right, making a reverse cut across the backs of the knees while entering with the left foot. |

[22v] Estramaçon en double baterie en garde quarte. Battez la première en dedans mains à bas vers vostre gauche avec l'espée et la seconde avecq le poingnardt en montant vers vostre droit faysant estramaçon d'un revers sur les jarrets en entrant du pied gauche. | |

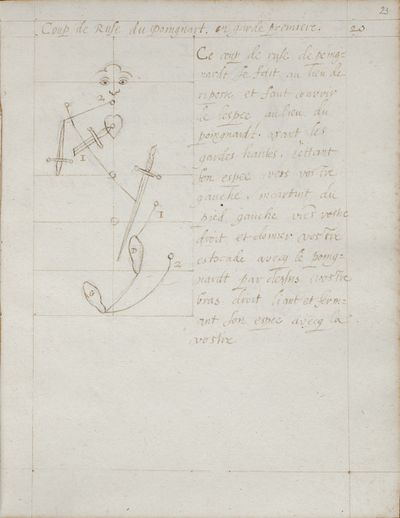

Cunning blow with the dagger in first guard. This cunning blow with the dagger is made instead of a riposte. You must cover with the sword instead of with the dagger, having the guards high, casting his sword towards your left, turning with the left foot towards your right, and give your thrust with the dagger over your right arm, binding and shutting out his sword with yours. |

[23r] Coup de ruse du poingnart. En garde premiere. Ce coup de ruse de poingnardt se fait au lieu de riposte et faut couvrir de l'espée au lieu du poingnardt. Ayant les gardes hautes, jettant son espée vers vostre gauche, incartant du pied gauche vers vostre droit et donner vostre estocade avecq le poingnardt par dessus vostre bras droit liant et fermant son espée avecq la vostre. | |

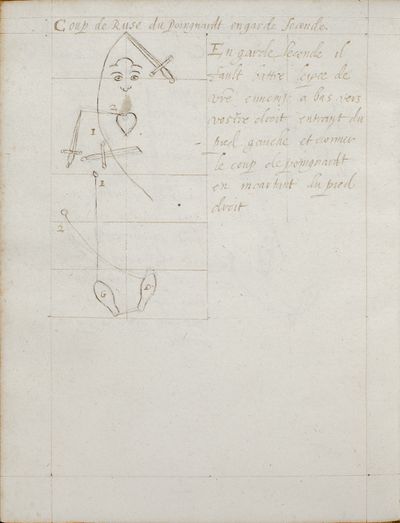

Cunning blow with the dagger in second guard. In second guard, you must beat the sword of your enemy down towards your right, entering with the left foot. And give the blow with the dagger while turning with the right foot. |

[23v] Coup de Ruse du Poingnardt en garde seconde. En garde seconde il fault battre l'espée de vostre ennemy à bas vers vostre droit entrant du pied gauche et donner le coup de poingnardt en incartant du pied droit. | |

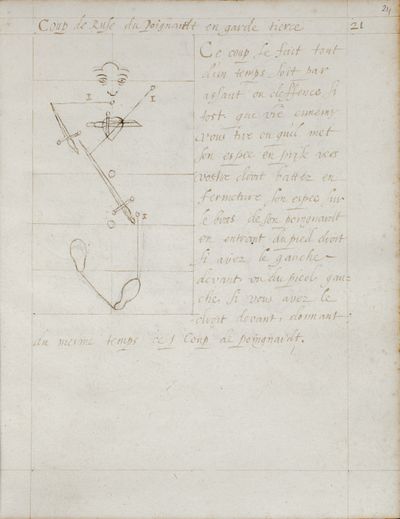

Cunning blow with the dagger in third guard. This blow is made all in one time, either as assault or as defence. As soon as your enemy strikes you or places his sword engaged towards your right, beat shutting out his sword over the arm of his dagger while entering with the right foot if you have the left in front, or with the left foot if you have the right in front, giving at the same time this blow with the dagger. |

[24r] Coup de ruse du poingnardt en garde tierce. Ce coup se fait tout d'un temps soit par assaut ou déffence si tost que vostre ennemy vous tire ou qu'il met son espée en prise vers vostre droit battez en fermeture son espée sur le bras de son poingnardt en entrant du pied droit si avez le gauche devant ou du pied gauche si vous avez le droit devant, donnant du mesme temps ce coup de poingnardt. | |

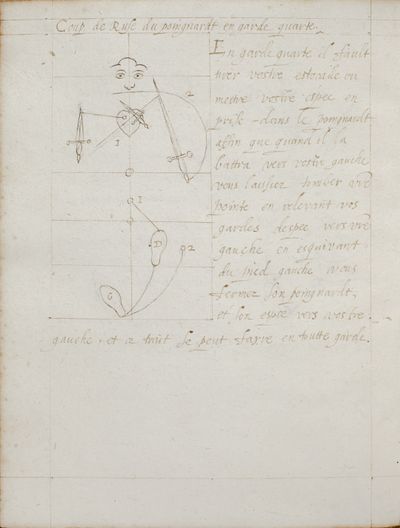

Cunning blow with the dagger in fourth guard. In fourth guard, you must strike your thrust or place your sword engaged inside the dagger, so that when he will beat it towards your left, you let your point drop while raising your guards of the sword towards your left evading with the left foot. You shut out his dagger and his sword towards your left, and this trick can be done in each guard. |

[24v] Coup de ruse du poingnardt en garde quarte. En garde quarte il fault tirer vostre estocade ou mettre vostre espée en prise dans le poingnardt affin que quand il la battra vers vostre gauche vous laissiez tomber vostre pointe en relevant vos gardes d'espée vers vostre gauche en esquivant du pied gauche, vous fermez son poingnardt et son espée vers vostre gauche, et ce trait se peut fayre en toutte garde. | |

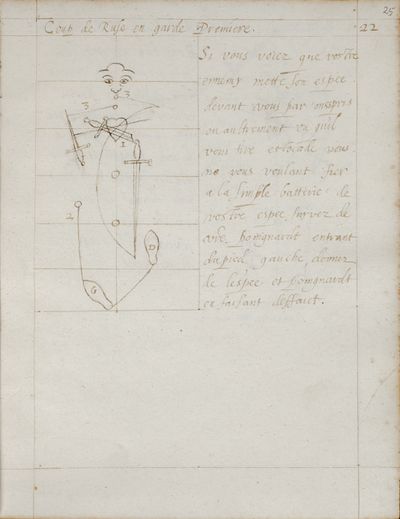

Cunning blow in first guard. If you see that your enemy places his sword in front of you with disdain, or otherwise, or if he strikes you a thrust, you not wanting to rely on the simple beat with your sword, follow with your dagger, entering with the left foot, give with the sword and the dagger in making retreat. |

[25r] Coup de Ruse en garde première. Si vous voiez que vostre ennemy mette son espée devant vous par méspris ou aultrement ou qu'il vous tire estocade vous ne vous voulant fier à la simple batterie de vostre espée suyvez de vostre poingnardt entrant du pied gauche, donnez de l'espée et poingnard en faisant d'effaict. | |

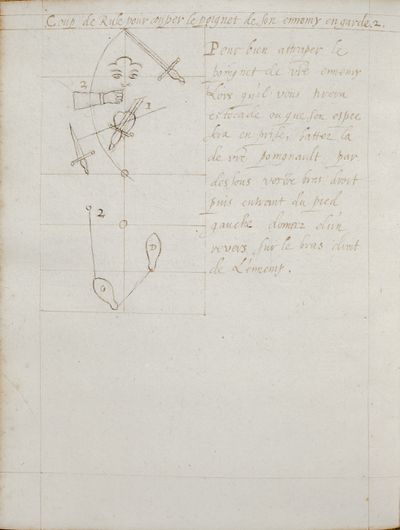

Cunning blow for cutting the wrist of your enemy in second guard. To catch the wrist of your enemy well, while he will strike you a thrust or while his sword will be engaged, beat it with your dagger below your right arm. Then entering with the left foot, give a reverse [cut] across the right arm of the enemy. |

[25v] Coup de ruse pour couper le poignet de son ennemy en garde 2.[24] Pour bien attraper le poingnet de vostre ennemy lors qu'il vous tirera estocade ou que son espée sera en prise, battez-la de vostre poingnardt par dessous vostre bras droit puis entrant du pied gauche donnez d'un revers sur le bras droit de l'ennemy. | |

Bind[25] of the sword and dagger in third guard. This bind is made when you see that your enemy places his sword engaged or if he strikes you a thrust. So to beat his sword towards your right over the arm of his dagger, entering with the right foot and following with the left, you must constrict him with the dagger from behind as if you are holding him embraced, then you can make him the rack.[26] |

[26r] Liaison de l'Espee et poingnardt. En garde tierce Ceste liaison se faict lors que vous voiez que vostre ennemy met son espée en prise et qu'il vous tire estocade. Affin de battre son espée vers vostre droit sur le bras de son poingnardt entrant du pied droit et suyvant du gauche fault le ferrer avecq le poingnardt par derrièrre comme le tenant embrassé luy pouvez faire le chevallet. | |

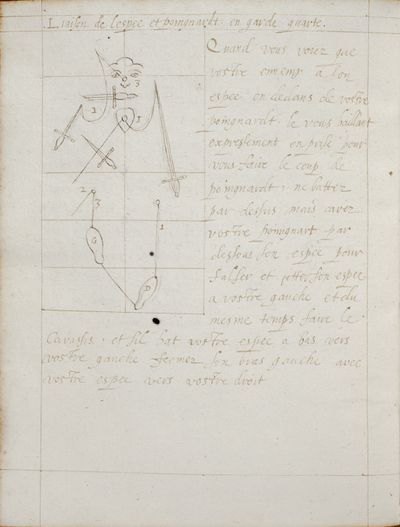

Bind of the sword and dagger in fourth guard. When you see that your enemy has his sword within your dagger, giving it to you explicitly in the engagement to make you the blow of the dagger,[27] do not beat above, but disengaging your dagger underneath his sword to bend and cast his sword to your left and at the same time, make the cavade. And if he beats your sword down towards your left, shut out his left arm towards your right with your sword. |

[26v] Liaison de l'espée et poingnardt. En garde quarte. Quand vous voiez que vostre ennemy a son espée en dedans de vostre poingnardt le vous baillant expressément en prise pour vous faire le coup de poingnardt, ne battez par dessus mais cavez vostre poingnart par dessous son espée pour falser et jetter son espée à vostre gauche et du mesme temps faire le cavassis. Et s'il bat vostre espée à bas vers vostre gauche fermez son bras gauche avec vostre espée vers vostre droit. | |

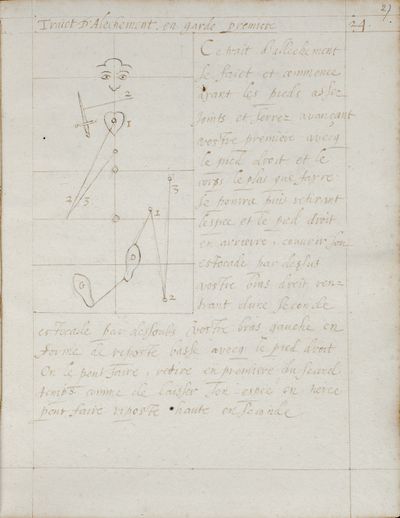

Trick of enticement[28] in first guard. This trick of enticement is done and starts having the feet quite close together, advancing your first [thrust] with the right foot and the body as much as you can. Then drawing back the sword and the right foot backwards, cover his thrust over your right arm, stepping in with a second thrust from below your left arm in the form of a low riposte, with the right foot. You can do this drawn back in first in the second time, as well as leaving your sword in third to make a high riposte in second. |

[27r] Traict d'alèchement. En garde première. Ce trait d'allèchement se faict et commence ayant les pieds assez joints et serrez avançant vostre première avecq le pied droit et le corps le plus que fayre se pourra puis retirant l'espée et le pied droit en arrièrre, couvrir son estocade par dessus vostre bras droit rentrant d'une seconde estocade par dessoubs vostre bras gauche en forme de riposte basse avecq le pied droit. On le peut faire, retire en première du second temps comme de laisser son espée en tierce pour faire riposte haute en seconde. | |

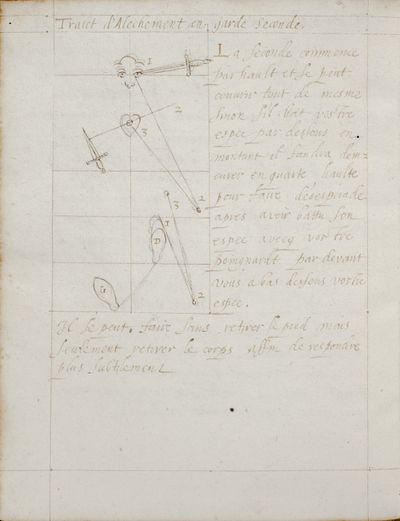

Trick of enticement in second guard. The second begins from above and can cover just the same [as the previous trick]. Alternatively, if he beats your sword from below upwards, you will have to remain in high fourth to make despair,[29] after having beaten his sword with your dagger in front of you, underneath your sword. This can be done without drawing back the foot, but only drawing back the body, in order to respond more subtly. |

[27v] Traict d'alèchement en garde seconde. La seconde commence par hault et se peut couvrir tout de mesme sinon s'il bat vostre espée par dessous en montant il faudra demeurer en quarte haulte pour faire désespérade après avoir battu son espée avecq vostre poingnardt par devant vous à bas dessous vostre espée. Il se peut faire sans retirer le pied mais seulement retirer le corps affin de respondre plus subtilement | |

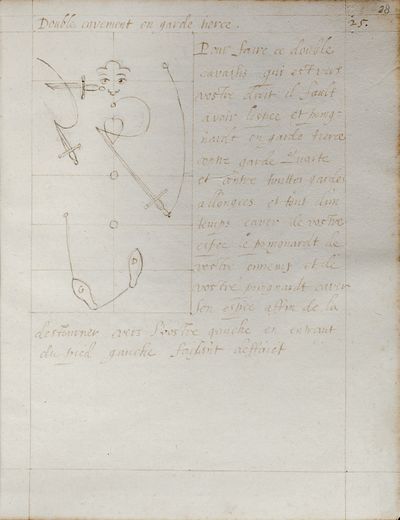

Double cavade in third guard. To make this double cavade, which is towards your right, you must have the sword and the dagger in the third guard against the fourth guard and against all elongated guards. And all at once, disengage with your sword from the dagger of your enemy, and with your dagger disengage from his sword, in order to deflect this towards your left while entering with the left foot, voiding[30] |

[28r] Double cavement en garde tierce. Pour faire ce double cavassis qui est vers vostre droit il fault avoir l'espée et poingnardt en garde tierce contre guarde quarte et contre touttes gardes allongées et tout d'un temps caver de vostre espée le poingnardt de vostre ennemy et de vostre poingnardt caver son espée affin de la destourner vers vostre gauche en entrant du pied gauche faisant d'effaict. | |

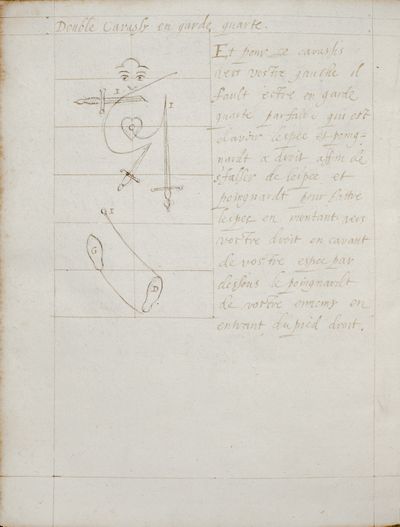

Double cavade in fourth guard. And for this cavade towards your left, you must be in the perfect fourth guard, which is having the sword and dagger on the right in order to remove your sword and dagger to beat the sword upwards towards your right while disengaging your sword underneath the dagger of your enemy, entering with the right foot. [The text of the technique simply ends; there is no text denoting the end of the work.] |

[28v] Double cavassy en garde quarte. Et pour ce cavassis vers vostre gauche il fault estre en garde quarte parfaite qui est d'avoir l'espée et poingnardt à droit affin de s'falser de l'espée et poingnardt pour battre l'espée en montant vers vostre droit en cavant de vostre espée par dessous le poingnardt de vostre ennemy en entrant du pied droit. |

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illustrations | |||

| Translation | Reinier van Noort | Ense et Mente | |

| Transcription | Aurélien Dordor | Index:Cabinet d'escrime de l'espee et poingnardt (MS KB.73.J.39) |

Additional Resources

The following is a list of publications containing scans, transcriptions, and translations relevant to this article, as well as published peer-reviewed research.

- Dupuis, Olivier (2016). "The French Fencing Traditions, from the 14th Century to 1630 through Fight Books." Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe: 354-375. Ed. by Daniel Jaquet; Karin Verelst; Timothy Dawson. Leiden and Boston: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004324725_014. ISBN 978-90-04-31241-8.

References

- ↑ Matt Galas estimates that it was written in the 1580s or 1590s based on internal evidence.

- ↑ An alternative translation of “premier” could be “foremost”.

- ↑ Espagnol

- ↑ This seems to refer to King Henry Ⅳ of France.

- ↑ Vostre Excellence

- ↑ vostre

- ↑ "de par deçà"?

- ↑ A little further down in the treatise, after the Riposte from fourth guard, the primes are described as attacks given from close measure where further advancing is not required. The premieres are defined as attacks given whilst advancing into measure. The movements indicated on the four diagrams showing the guard may demonstrate the prime that can be made from each guard.

- ↑ milieu

- ↑ Your right foot.

- ↑ The phrase “faisant deffaicte” provided some difficulty. Possible translations include “to avoid” or “to miss”, but whether it relates to an action of the body/feet or of the sword is unclear. Throughout the treatise we have chosen to translate it as “voiding”. In this instant it can mean either voiding a possible counter, for instant by stepping offline, or it could mean avoiding a possible defence with your sword. Neither of these avoidances is specifically indicated in the accompanying diagram.

- ↑ d'effet? défaite?

- ↑ Most likely this ambiguous section indicates that during the first (assaulting) you must cover with the sword and during the second (riposting) you must cover with the dagger.

- ↑ The French word “Tirade” seems to indicate a feint performed with a (partial) strike that is quickly drawn back for a second strike to be made to a different target. It is one of the three types of feint described in the treatise, together with a feint by cavade (“Cavement”) and afeint by arching (“voûtement”).

- ↑ Voûtement” from ”voûte”, which in turn derives from old French “volte”. Despite the similarity to the Italian term “volta” a blade action is intended here, whereby the blade is curved upwards around the cover placed by the opponent. Instead, “incarter” is used for the volta-like stepping action. This has been translated here as “turning”, as in “turn with the left foot”.

- ↑ From the context it is not clear what “the first” refers to. Possibilities include the first tirade (i.e. the tirade from first guard) and the simple riposte.

- ↑ This most likely refers to using a feint as second as mentioned in the nota after the “Tirade in first guard”.

- ↑ Here, “making it miss” might be a better translation.

- ↑ The sentence “faisant déffait ou retraitte” suggests that both are actions of the body/feet. You either retreat (backwards) or void (going sideways).

- ↑ From context, the most likely translation might have been “as second [attack]”.

- ↑ It is unclear what exactly is meant with “en batterie”. Possibly the author either meant that the enemy's sword is in the process of making a beat, is in a position where it can be beat, or it could be a reference to artillery where “en batterie” means prepared to shoot. In this case, that could mean that the sword is aimed at you in a position where you can easily beat it aside (and that the opponent is ready to attack).

- ↑ première

- ↑ genou

- ↑ seconde

- ↑ “Liaison” or bind seems to indicate a harder, stronger engagement.

- ↑ This is a literal translation of “Chevallet”. Likely, a grappling or wrestling move, potentially a throw, is meant by this.

- ↑ This most likely refers to the “Cunning blow of the dagger in fourth guard”.

- ↑ I.e. an invitation.

- ↑ According to Cotsgrave French-English dictionary of 1611, the French word “désesperade” means “a long mournful song”. Here, “faire désesperade” was translated as “make despair”.

- ↑ Here, “faisant deffaict” could mean either avoiding his dagger with your sword, or voiding in general.