|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Liber de Arte Dimicatoria"

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{DISPLAYTITLE:''{{PAGENAME}}''}} | ||

{{infobox medieval text | {{infobox medieval text | ||

<!----------Name----------> | <!----------Name----------> | ||

| Line 959: | Line 960: | ||

| source link = http://www.nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:384-uba002004-0 | | source link = http://www.nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:384-uba002004-0 | ||

| source title= Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg | | source title= Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg | ||

| − | | license = | + | | license = public domain |

}} | }} | ||

{{sourcebox | {{sourcebox | ||

| Line 966: | Line 967: | ||

| source link = http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/bsb00107024/image_1 | | source link = http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/bsb00107024/image_1 | ||

| source title= Bayerische Staatsbibliothek | | source title= Bayerische Staatsbibliothek | ||

| − | | license = | + | | license = noncommercial |

}} | }} | ||

{{sourcebox | {{sourcebox | ||

| Line 987: | Line 988: | ||

== Additional Resources == | == Additional Resources == | ||

| − | + | {{bibliography}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 1,014: | Line 1,003: | ||

[[Category:New format]] | [[Category:New format]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Modular display candidate]] | ||

Latest revision as of 16:03, 17 November 2023

| Liber de Arte Dimicatoria | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| "Book on the Art of Fencing" | |||

|

| |||

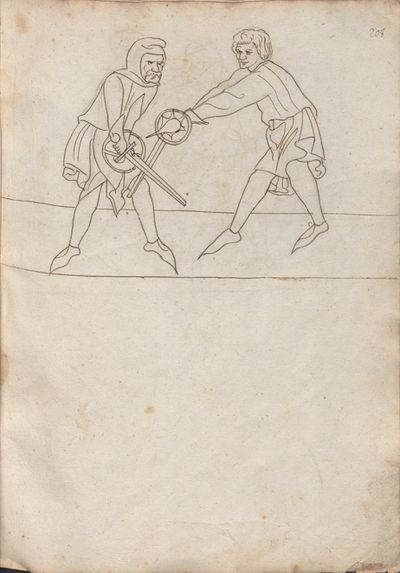

| Also Known as |

| ||

| Author(s) | Unknown | ||

| Ascribed to | Clericus Lutegerus | ||

| Illustrated by | Unknown (up to 17 artists) | ||

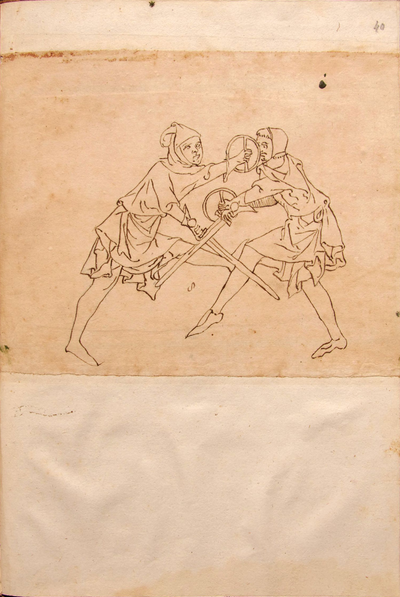

| Date | early 14th century | ||

| Genre | Fencing manual | ||

| Language | Medieval Latin | ||

| State of Existence | One substantial but incomplete manuscript exists, along with several fragments which may be related | ||

| Principal Manuscript(s) |

MS Ⅰ.33 (1320s) | ||

| Manuscript(s) |

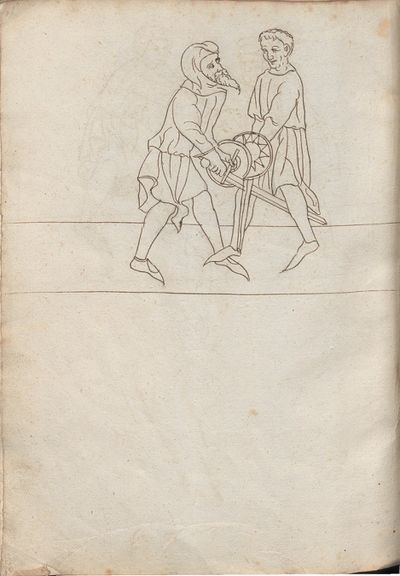

| ||

| First Printed English Edition |

Forgeng, 2003 | ||

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester | ||

| Translations | |||

|

Caution: Scribes at Work This article is in the process of updates, expansion, or major restructuring. Please forgive any broken features or formatting errors while these changes are underway. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. Stay tuned for the announcement of the revised content! This article was last edited by Michael Chidester (talk| contribs) at 16:03, 17 November 2023 (UTC). (Update) |

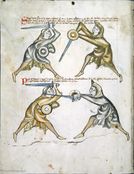

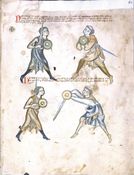

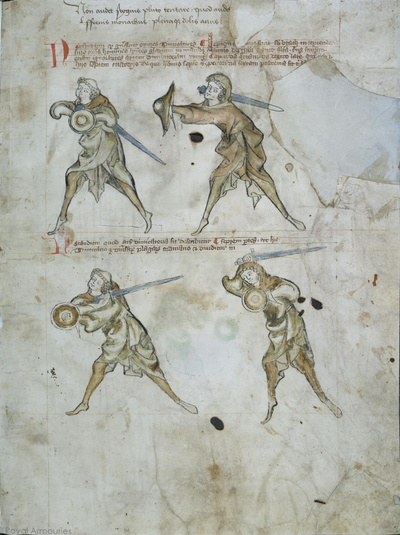

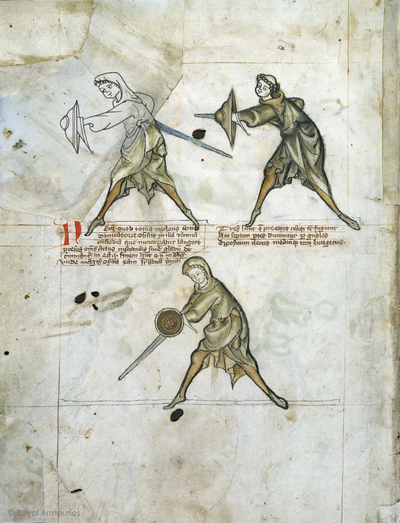

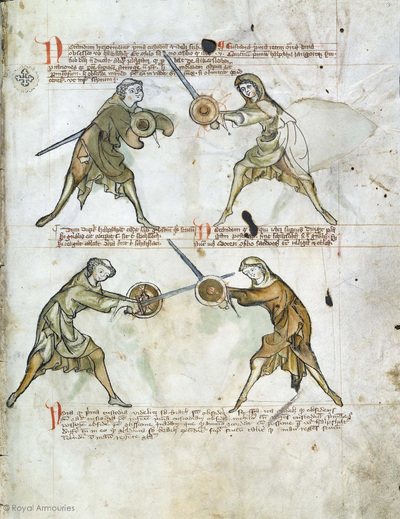

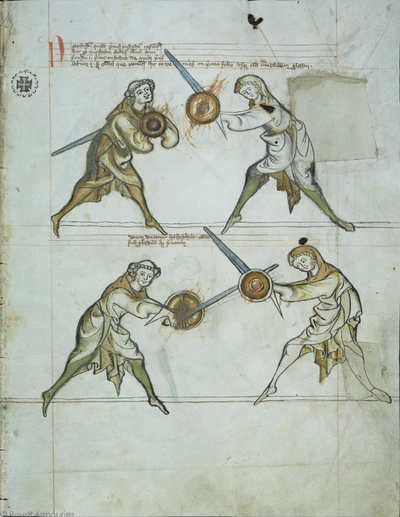

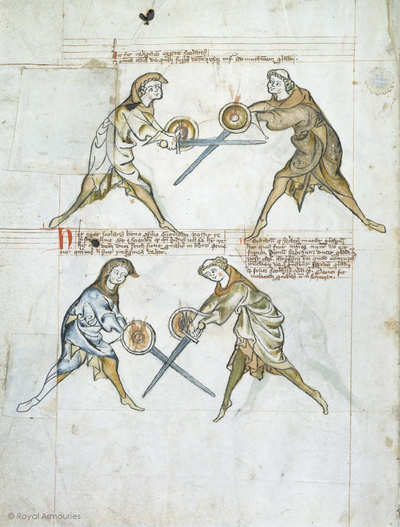

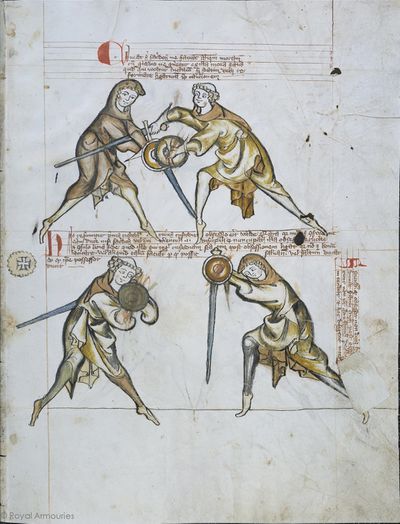

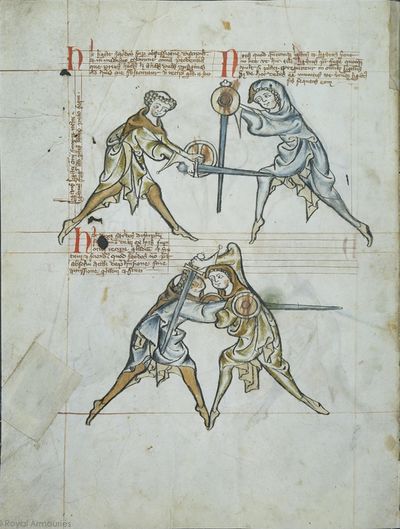

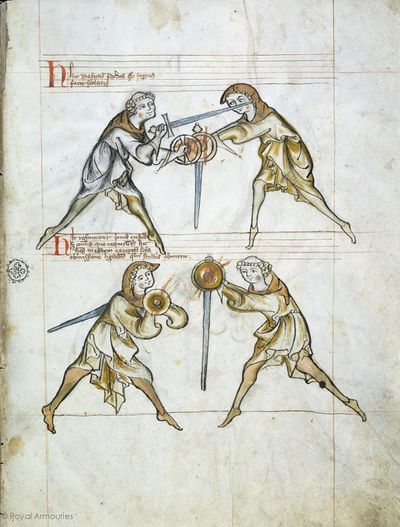

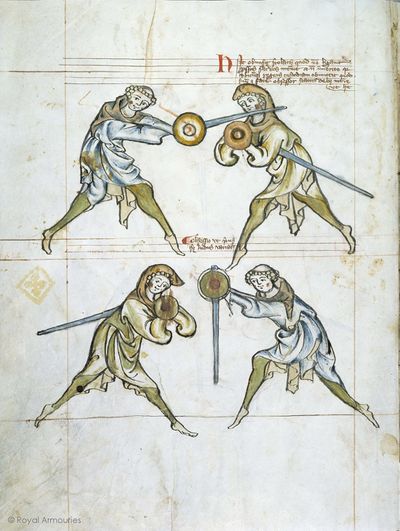

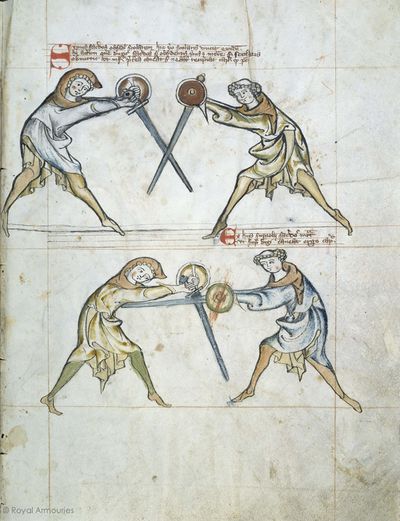

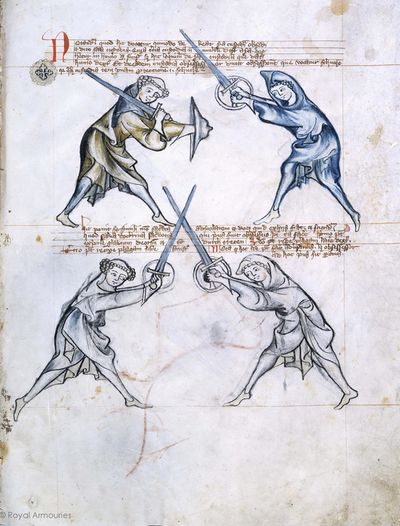

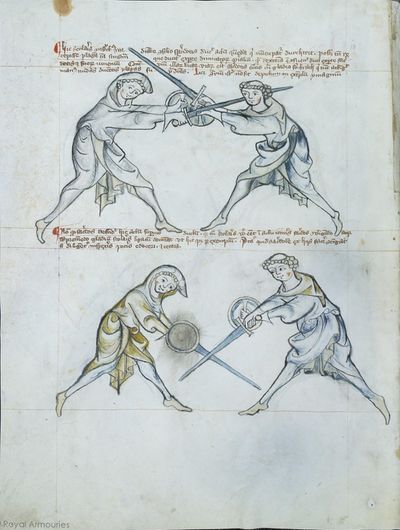

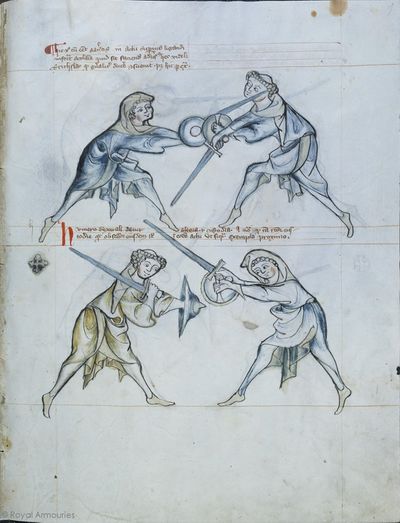

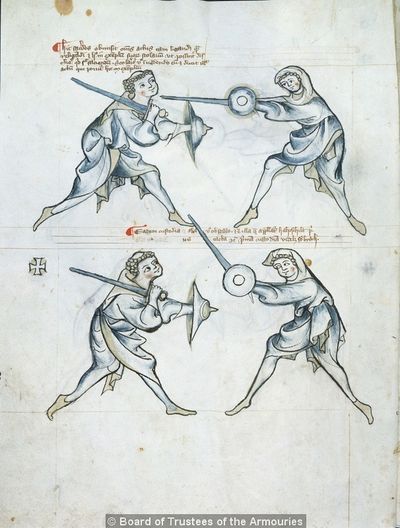

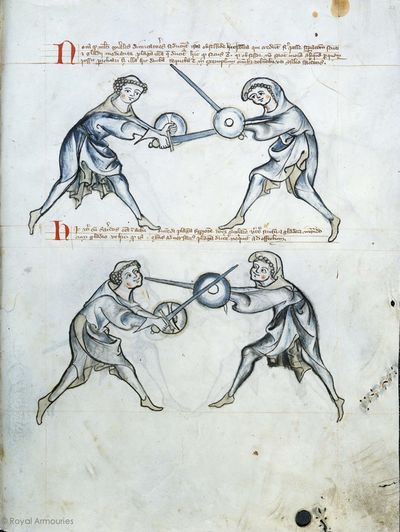

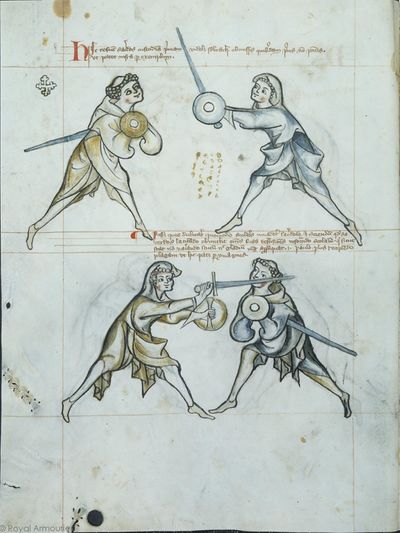

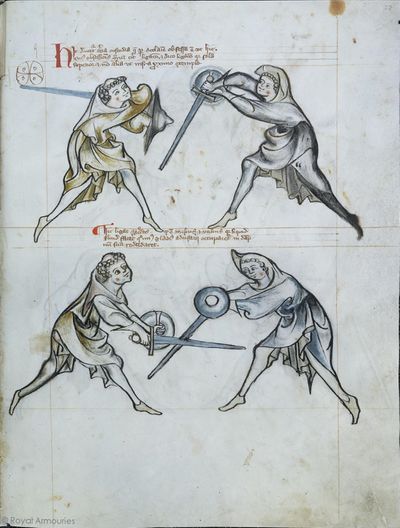

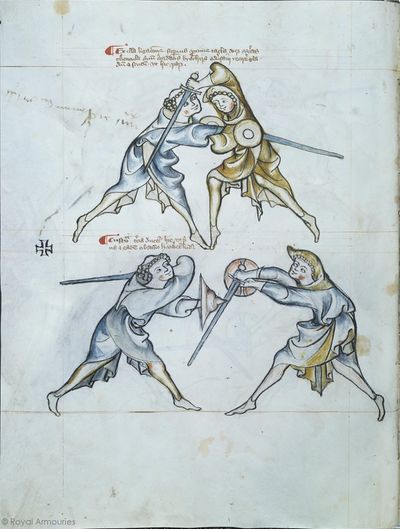

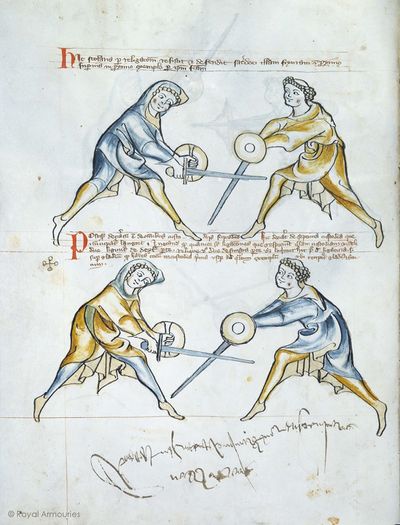

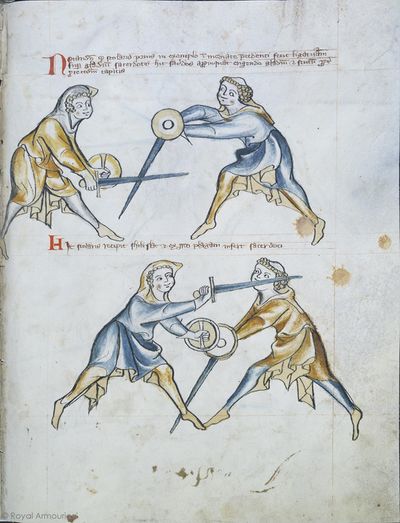

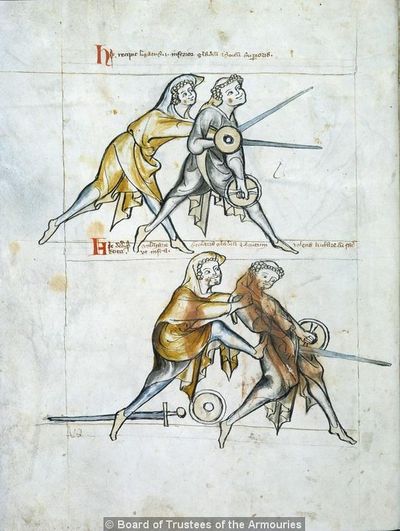

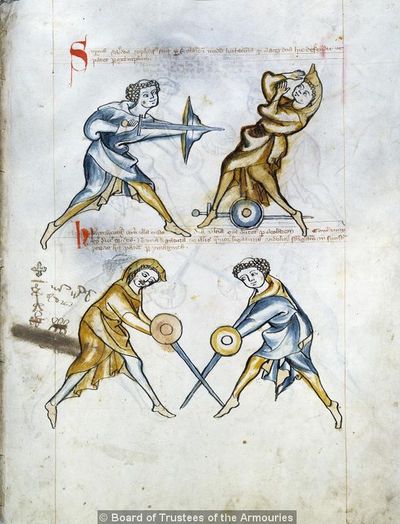

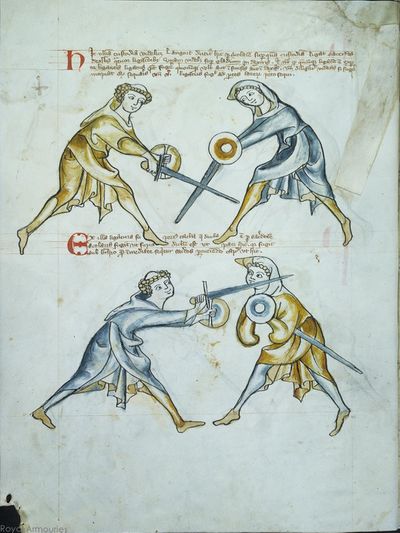

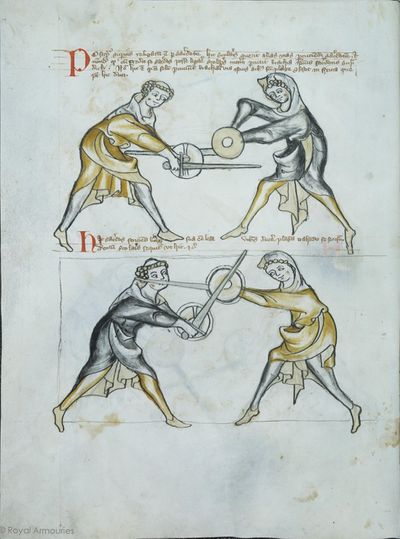

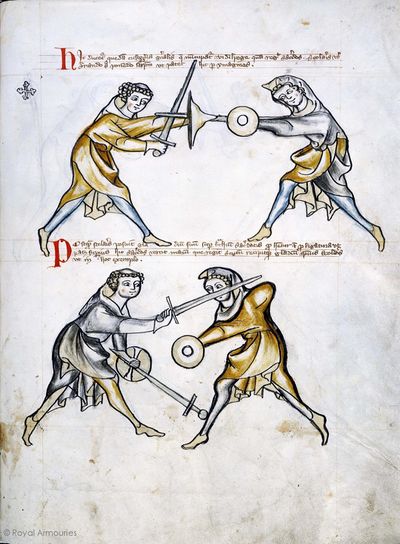

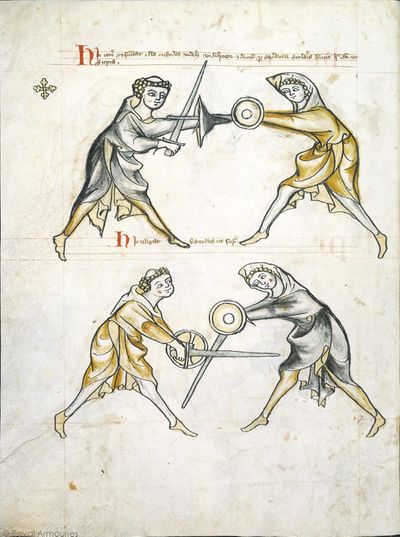

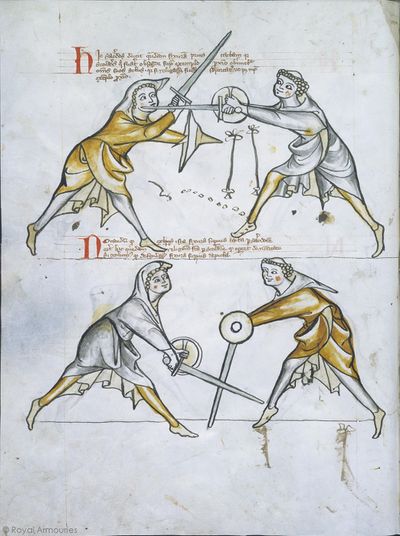

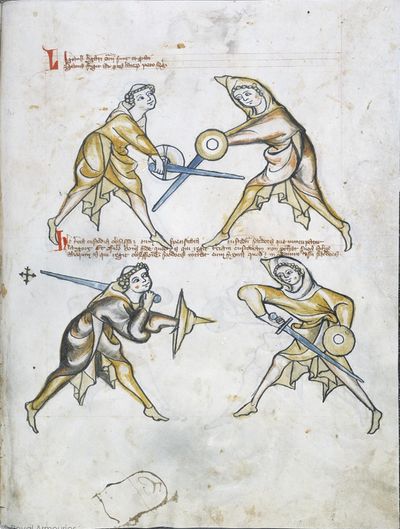

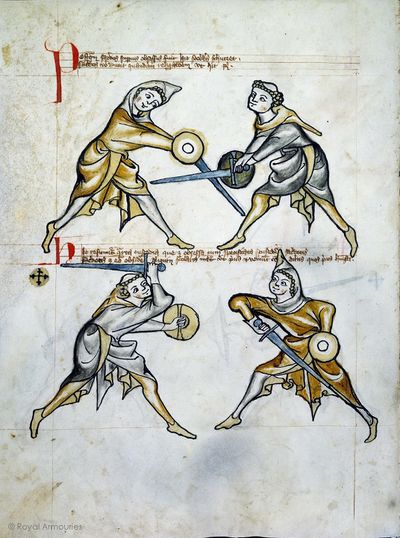

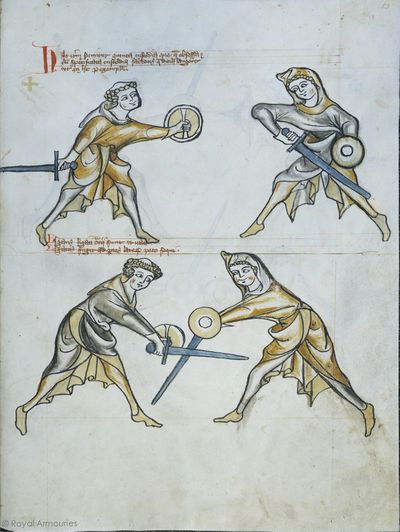

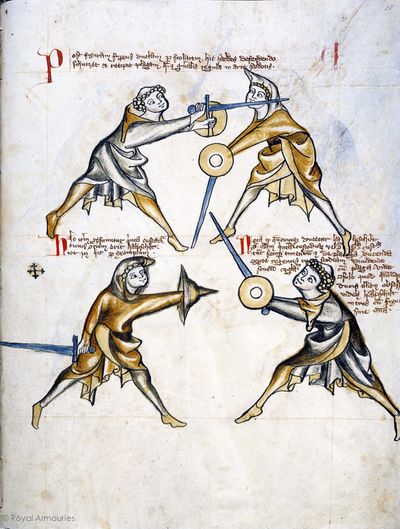

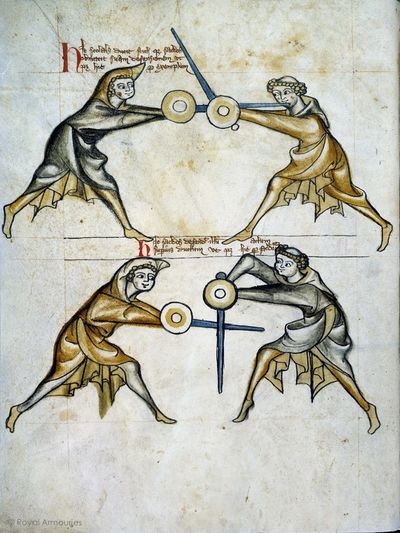

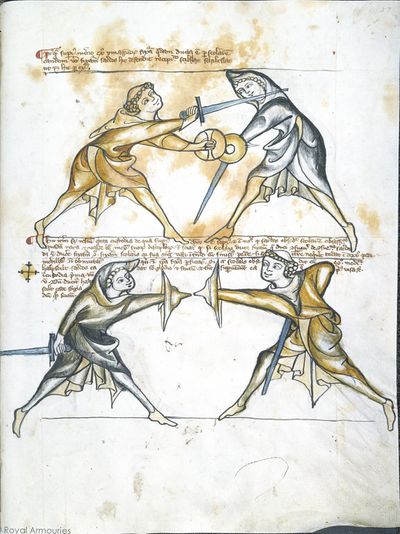

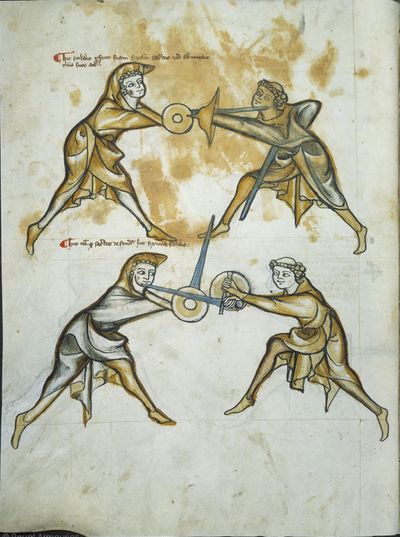

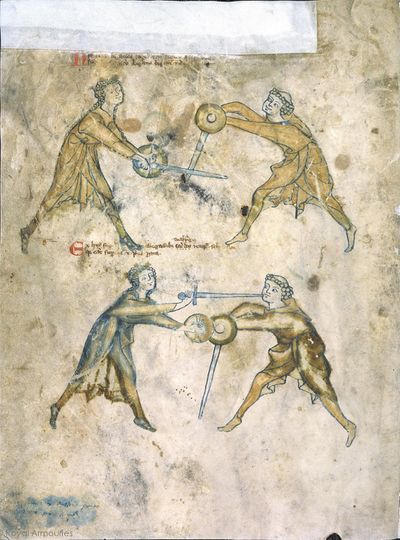

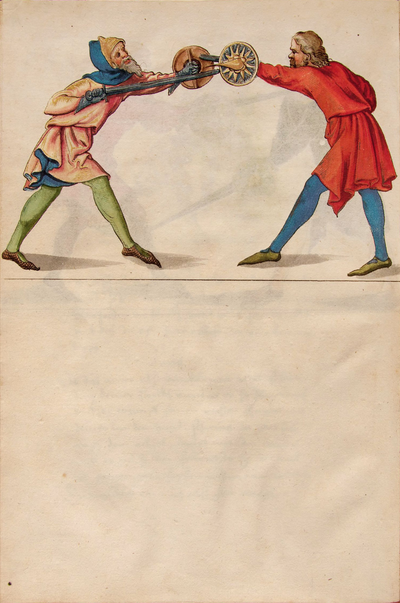

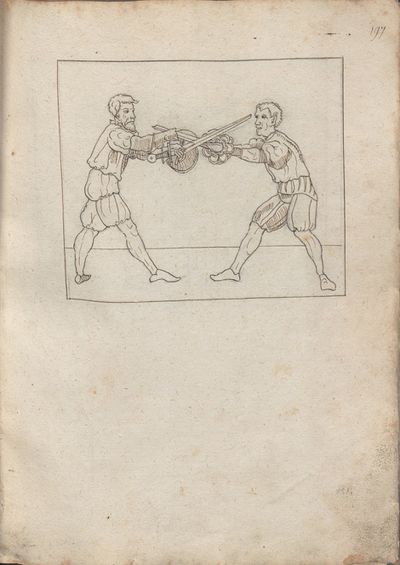

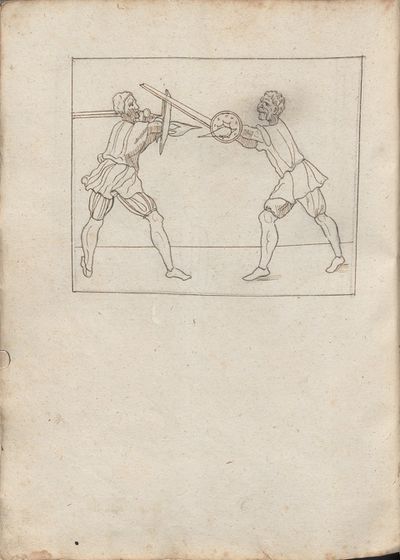

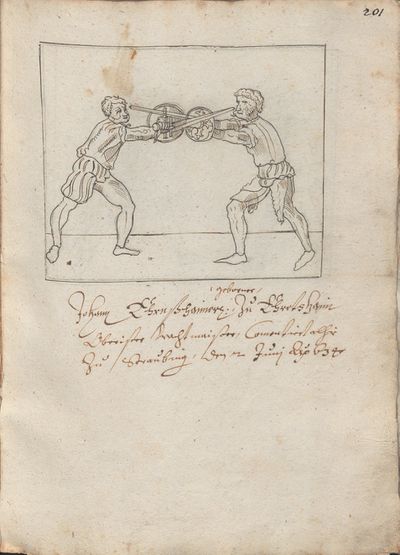

Liber de Arte Dimicatoria is a German fencing manual from the early 14th century; it is generally considered to be anonymous, though the name Ludger ("Lutegerus") appears prominently on the first folio and may be the name of the author or scribe. The illustrations and monastic origin of the principal manuscript, MS Ⅰ.33 (or FECHT 1), suggest that it was created by a member of the clergy (perhaps a priest or monk).

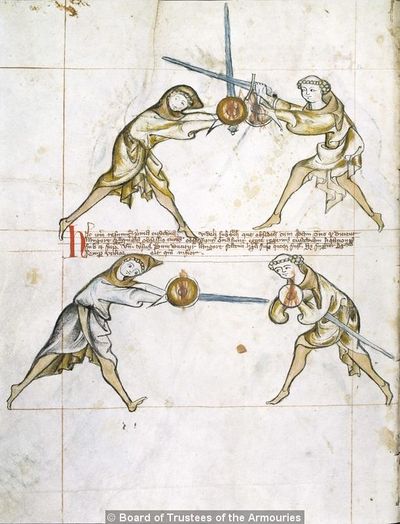

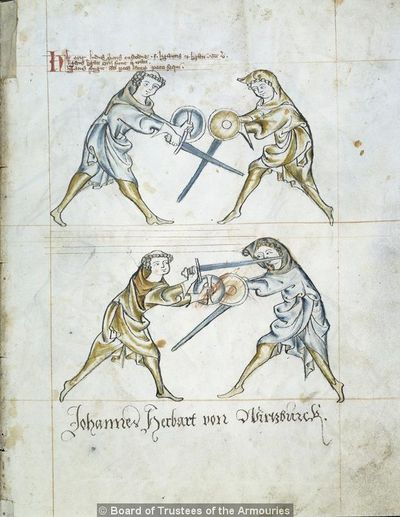

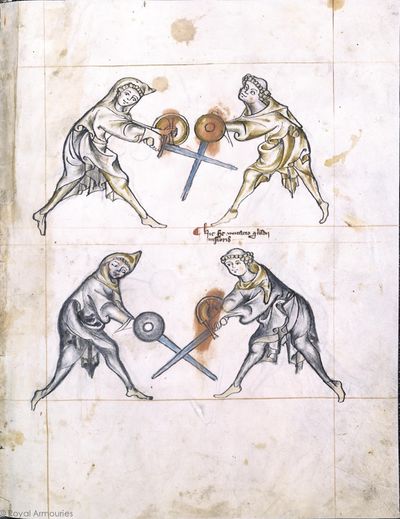

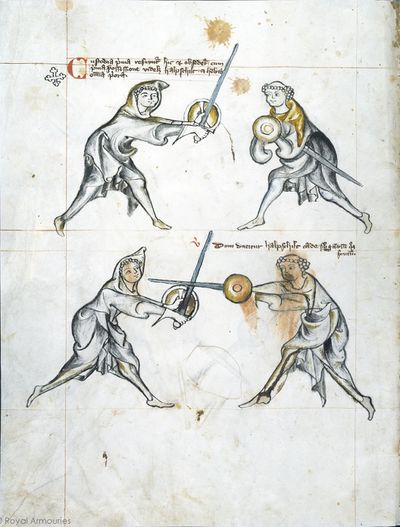

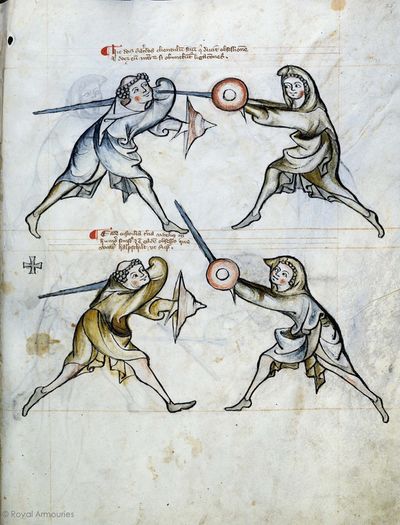

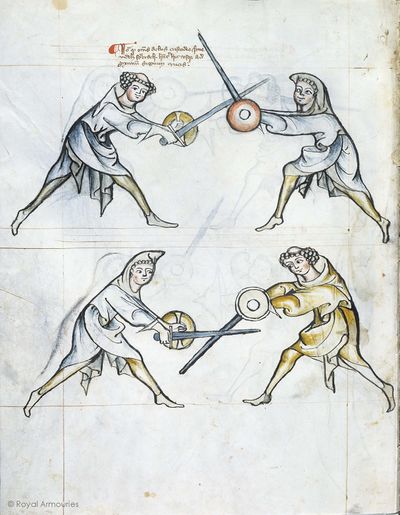

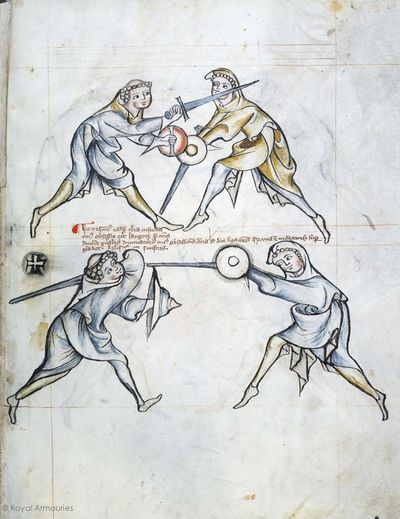

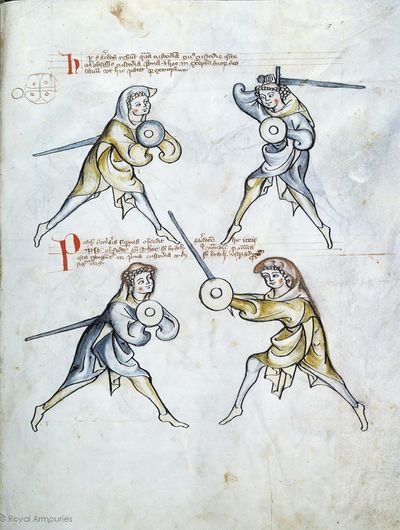

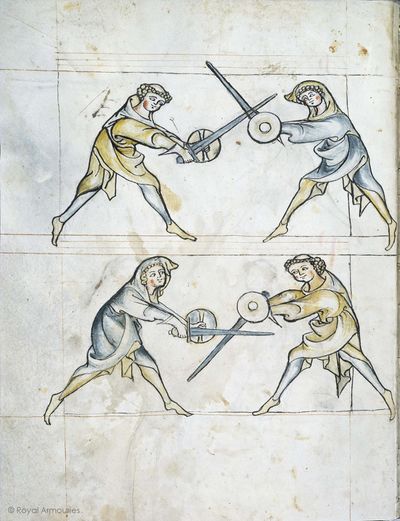

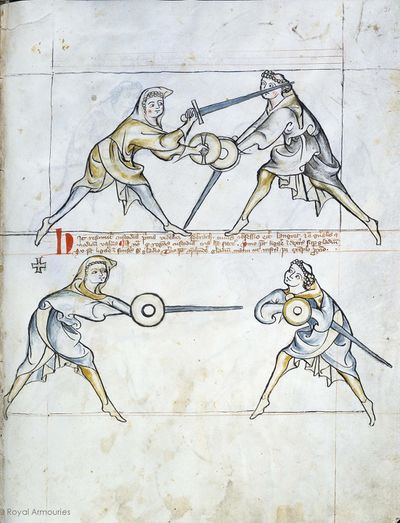

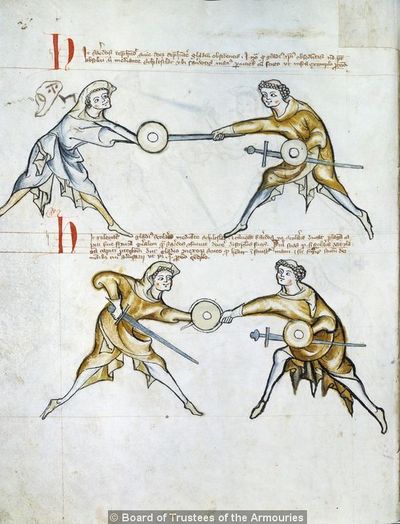

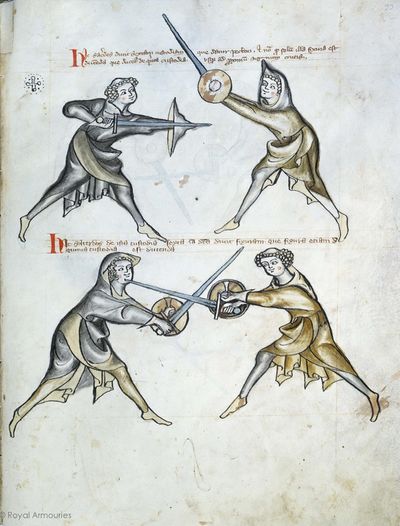

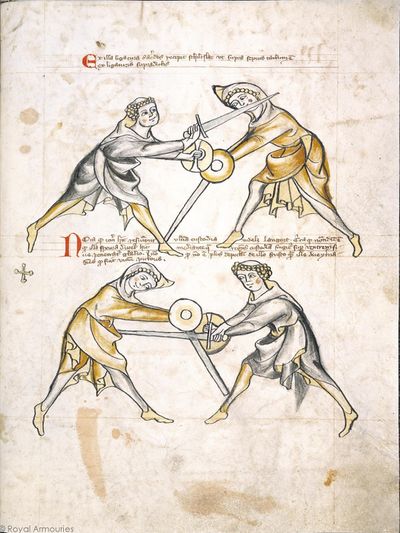

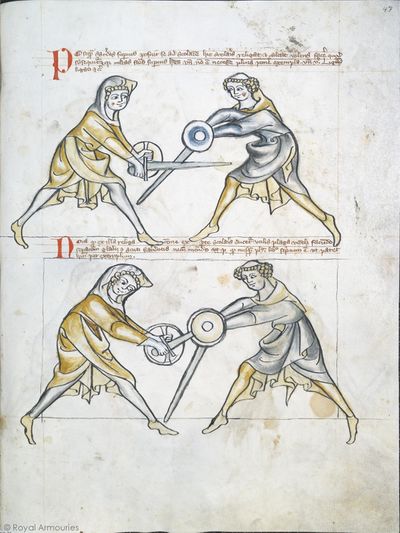

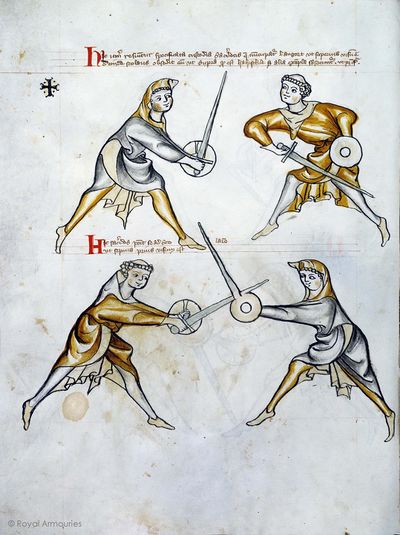

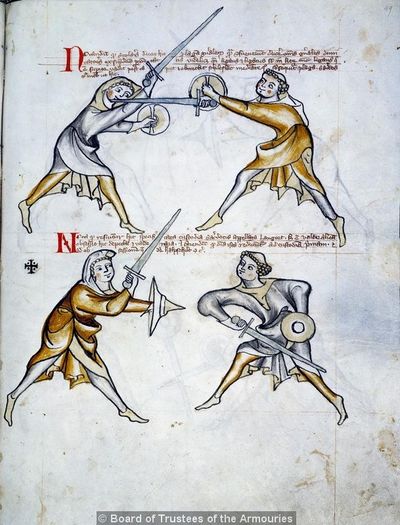

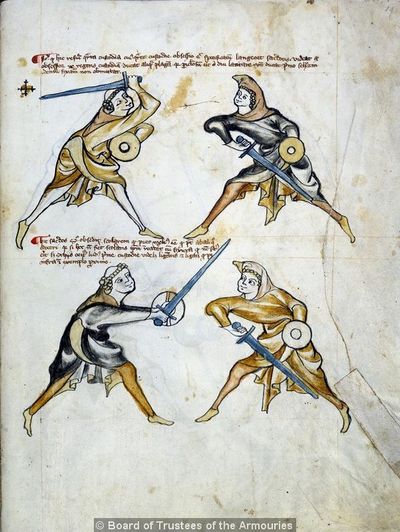

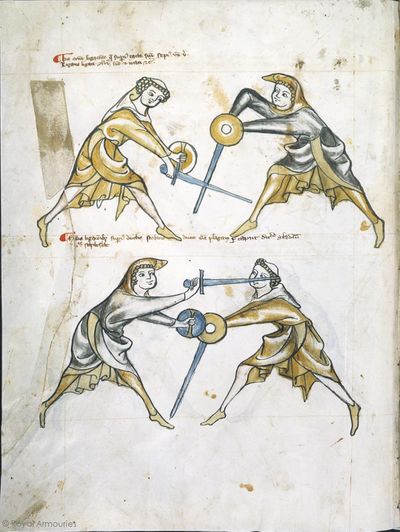

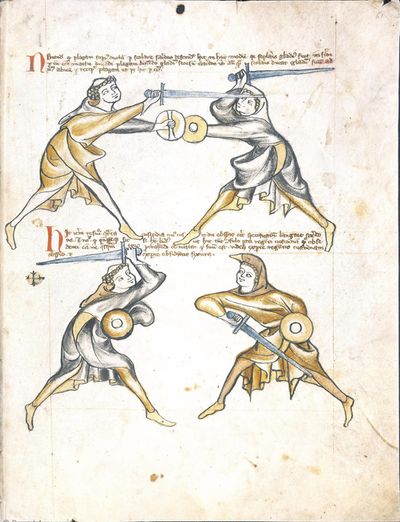

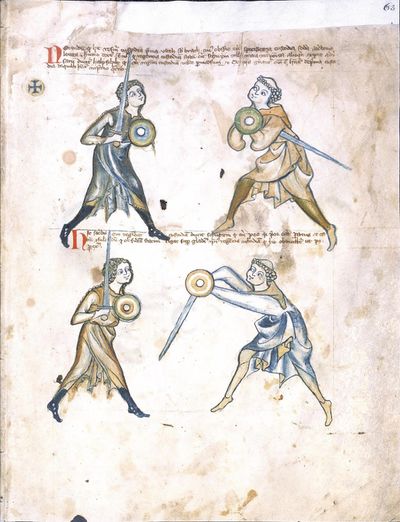

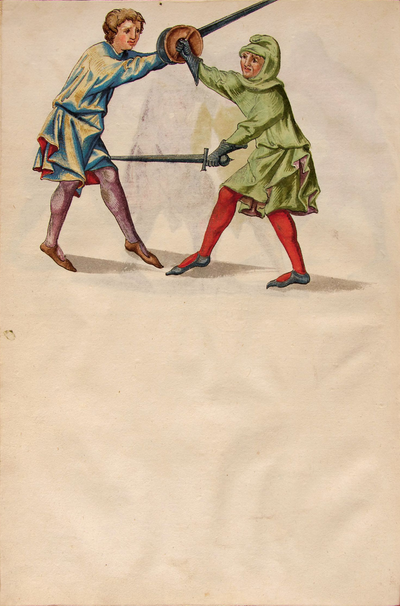

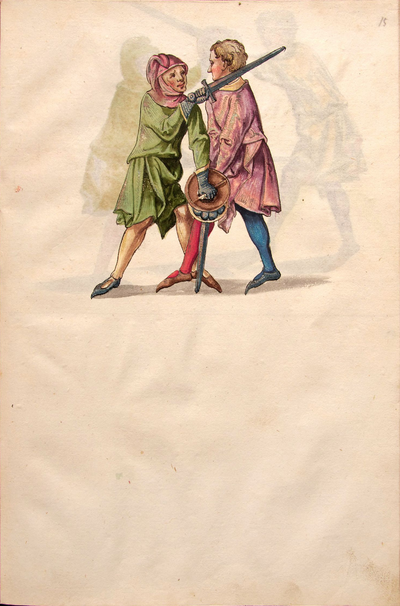

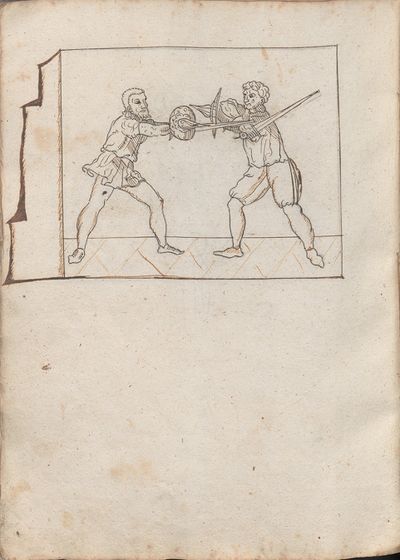

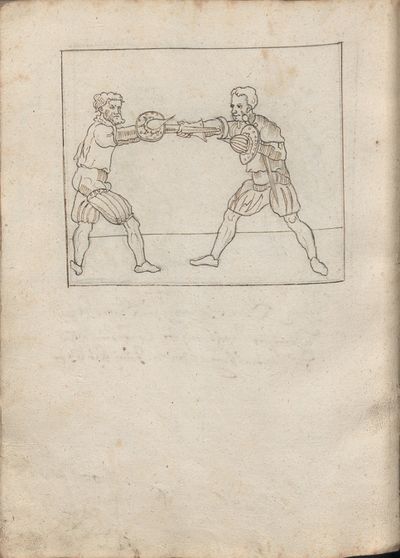

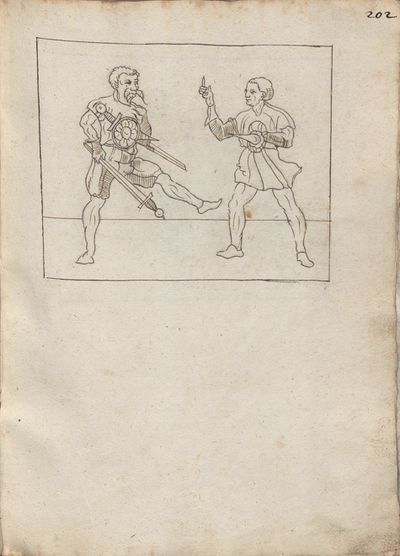

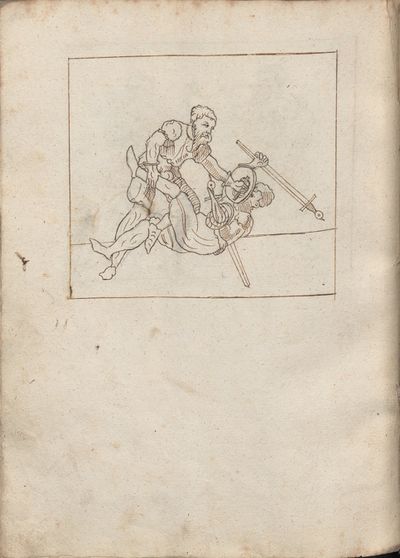

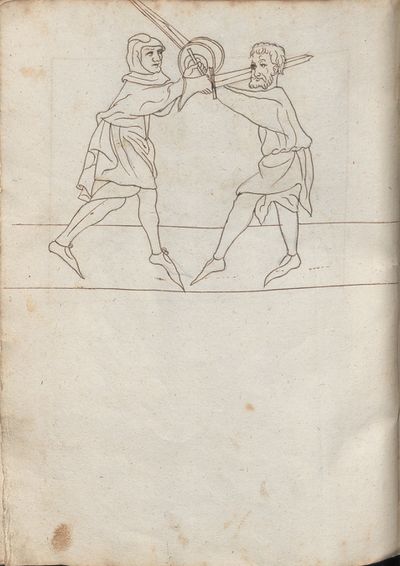

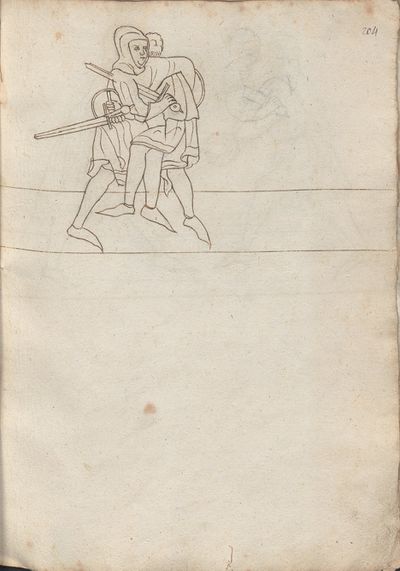

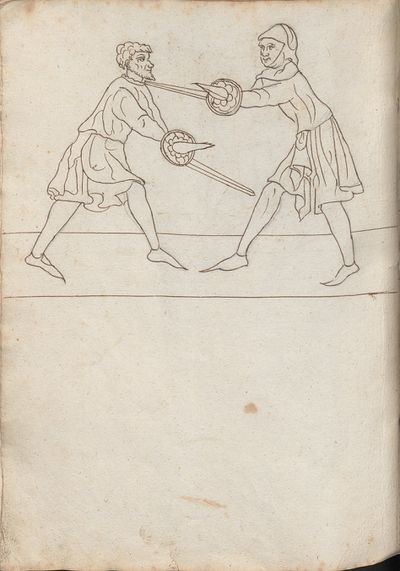

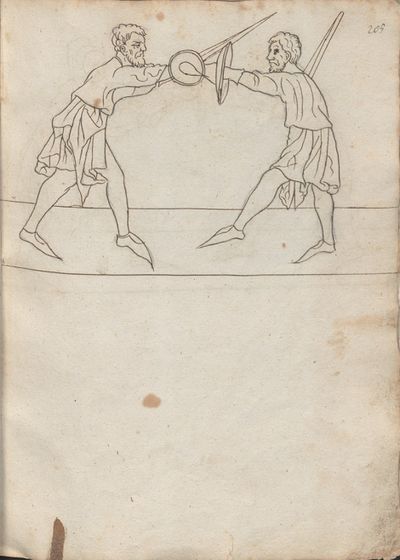

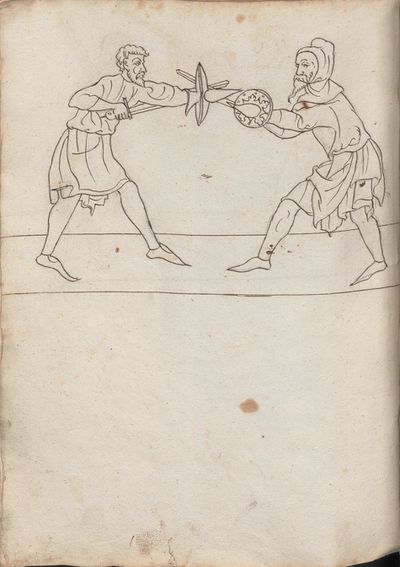

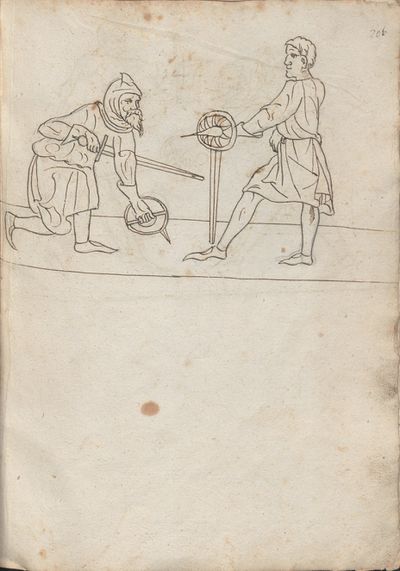

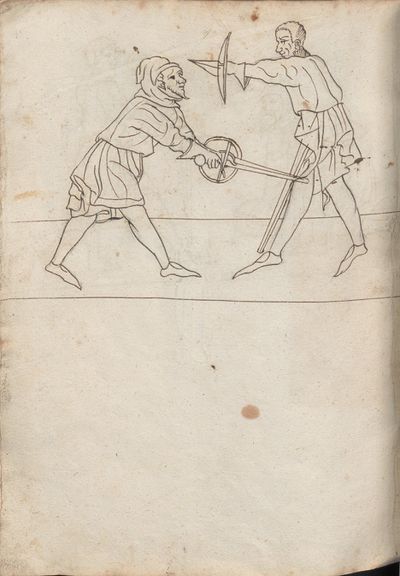

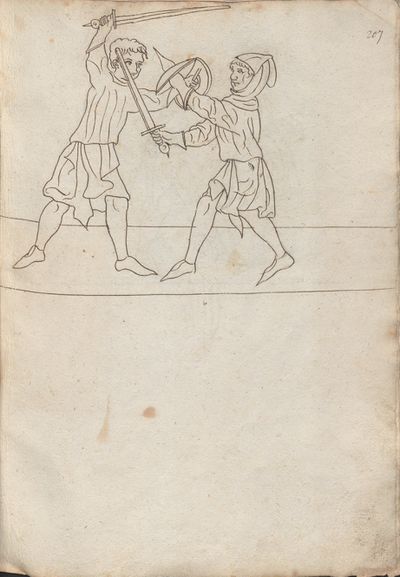

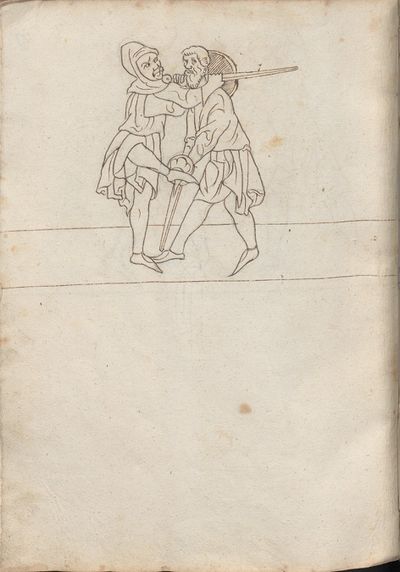

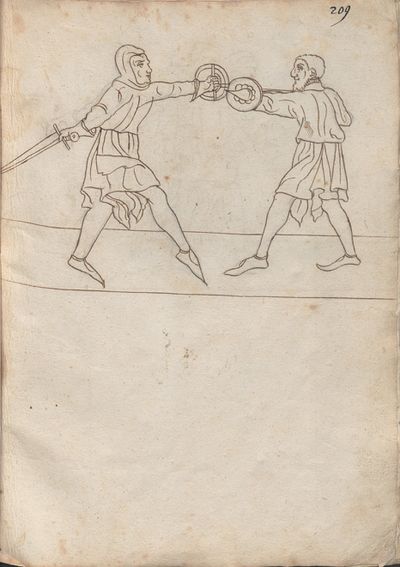

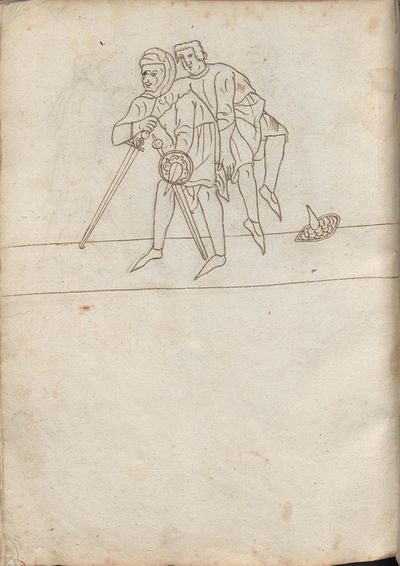

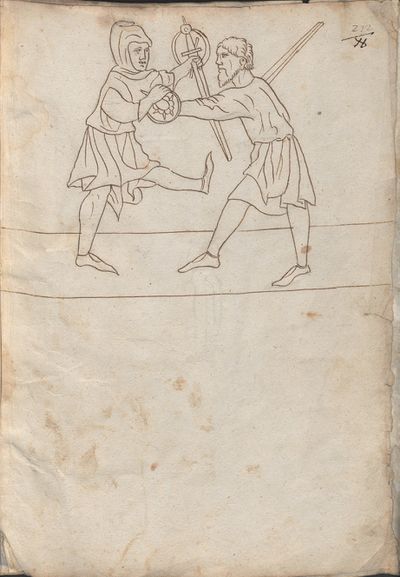

The treatise is fully illustrated, and the text includes both short mnemonic verses and longer explanations in a Medieval Latin with strong vernacular influences. (The format of verse and gloss may indicate that the author was recording a yet older tradition.) It treats unarmored fencing with sword and buckler; the intriguing fact that the fencers depicted are a priest and a student (and on the last two pages, a priest and a woman), seems to suggest that this was a middle class or priestly art rather than one of the knightly class. Repeatedly, the text makes mention of the pupils (scolaris or discipulus) of the priest, as well as youths (iuvenis) and clients (clientulum).

The apparent identification of the priest as Ludger and the woman as Walpurga may suggest an allegorical aspect to the artwork, as both names belong to Medieval saints who were popular in Germany.

The principal manuscript in its present form consists of five quires, of which all but the first are incomplete; at least eight leaves are believed to be missing (assuming it started with complete quires of four bifolia each).[1] The precise contents of these missing leaves are unknown, but it is possible that they were a source for the thirty uncaptioned sword and buckler plays which appear in the Libr.Pict.A.83, the Cod. Ⅰ.6.2º.4, and the Cgm 3712 (see below); alternatively, these may originate from another manuscript within the same tradition. The anonymous plays seem in turn to have been the main source for Paulus Hector Mair's treatment of rapier and buckler, which he captioned with his own interpretations; since Mayr's connection to this tradition seems limited to being a late commentator, his text is not included below.

Contents

Treatise

Scans of MS Ⅰ.33 are licensed under the terms of the Royal Armouries Non-Commercial Licence.

Folia 1r-3v have been conceptually restored by artist Mariana López Rodríguez; unmodified versions can be viewed on the Royal Armouries website.

Images |

Leeds Version | |

|---|---|---|

[1] Stygian Pluto dares not attempt what a rogue monk and a treacherous hag dare do.[2] |

[1r] Non audet stygius pluto tentare, quod aude[t] | |

[2] Note how in general all fencers, or all men who hold a sword in hand, even when ignorant in the art of fencing, make use of these seven guards, on which we have seven verses: |

NOtandum est quod generaliter omnes Dimicatores, sive omnes homines habentes gladium in manibus, etiam ignorantes artem dimicatoriam vtuntur hijs septem custodijs de quo habemus septem versus | |

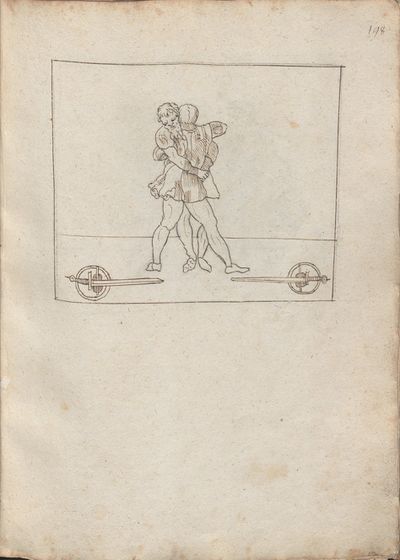

[3] Seven guards there are, under the arm the first |

¶ Septem [cust]odie sunt sub brach incipiende | |

[4] Note that the art of fencing is described as follows: Fencing is the ordering of various strikes, and it is divided into seven parts as here. |

NOtandum quod ars dimicatoria sic describitur Dimicatio est diversarum plagarum ordinatio & diuiditur in ¶ septem partes vt hic | |

[5] Note that the whole core of the art of fencing consists in this final guard which is called langort, because in it, all actions of the guards or the sword terminate, i.e. they end in it and not in the others, therefore consider it more than the the above-mentioned first one. |

[1v] NOta quod tot nucleus artis dimicatorie consistit in illa vltima custodia que nuncupatur langort pretera omnes actus custodiarum siue gladij determinantur in ea i. finem habent & non in alijs Vnde magis considera eam supradi[c]ta prima | |

[6] There are three which go forward, and the remaining then flee.[3] |

Tres sunt que preeunt relique tunc fugiunt | |

[7] (+) Note, here is contained the first guard, viz. the one under the arm, and the siege is halbschilt. And I give the sensible counsel that the one under the arm should not execute any strike, as recommends de Alkersleiben,[6] for the reason that he cannot reach the upper part; if [he should aim] lower, it would be pernicious to [his] head. But the besieger by entering could invade him at any time if he omits what is being held, as is written below. |

[2r] ⊕ NOtandum hic continetur prima custodia, videlicet sub [brachio] obsesseo vero halbschilt ¶ Et consulo sano consilio quod il[...] sub brachio non ducat aliquam plagam quod probat de al[b]ersleiben, per raciones quia partem superiorem attingere non potest si inferiorem capiti erit perniciosum sed obsessor intrando potest eum invadere quandocumque si obmittit quod tenetur vt infra scriptum est | |

[8] Verse: |

Versus: | |

[9] When halbschilt is executed, fall underneath sword and shield. |

¶ Dum ducitur halpschilt cade sub gladium quoque scutum | |

[10] Note that the one who lies above will direct a strike to the head without schiltslac if he is common. But if you want to be informed by the counsel of the priest, bind and press. |

NOtandum quod qui iacet superius dirigit plagam post [c]apud sine schiltslach si est generalis Si autem uis edoceri consilio sacerdotis tunc religa et calca | |

[11] Note that the first guard, viz. the one under the arm, can besiege itself, so that the one besieging with this guard can besiege the first guard; but nevertheless the one assuming first guard against the besieger can besiege the siege which corresponds with the siege that is called halbschilt, differing in this, that the sword is extended below the arm and above the shield so that the hand holding the shield is included in the hand holding the sword.[7] |

NOta quod prima custodia videlicet sub brachium potest obsederi se ipsa ita videlicet quod obsidens cum eadem custodia potest regentem primam custodiam obsidere nichilominus tamen regens custodiam primam econtrario possessorem obsidere potest obsessione quadam que quodammodo concordat cum possessione que vocatur halpshilt differt tamen in eo quod gladius sub brachio* extenditur supra scutum taliter quod manus regens scutum includitur in manu regente gladium | |

[12] Note that the scholar here binds and applies pressure so that he gets to perform a schiltslac as [in the image] below. But he should take care that what is to be done on the part of the priest [because] after the bind, the priest will be the first to act. Note also that the priest can do nothing other than a schiltslac or embracing with the left hand the arms of the priest, i.e. sword and shield. |

[2v] NOtandum quod scolaris [religat hic & calcat] ad hoc ut recipiat schiltslac vt infra Sed caueat de hiis que sunt facienda ex parte sacerdo[tis quia ...] post religationem sacerdos erit prior ad agendum | |

[13] It is to be seen, that the pupil has no option but to do a schiltslac, or to grip the arms of the priest with his left hand, namely sword and shield. |

[N]Otandum est etiam quod scolaris nichil habet aliud facere quam schiltslac vel circumdare sinistra manu brachia sacerdotis videlicet gladium & scutum | |

[14] Verse: |

Versus: Hic religat calcat scolaris sit sibi schilslach | |

[15] The priest here has three options, viz. sword-change, so that he is above, or durchtreten, or with the leftright hand embrace the arms of the scholar, i.e. sword and shield. |

Sacerdos autem tria habet facere videlicet mutuare gladium q vt fiat superior Siue durchtreten vel sinistradextra manu comprehendere brachia* scolaris i. gladium & scutum | |

[16] These three are for the cleric: durchtrit, sword-change, |

Hec tria sunt cleri durchtrit mutacio gladii | |

[17] Note that what is said above you find in this example.[9] |

Nota quod supradictum est invenies hic exempli gestum | |

[18] (+) Note that the first guard is resumed here, due to certain actions from the first section, i.e. of the first guard of which was treated before, but all that belongs here you find in the first page, up to the sword-change. |

[3r] ⊕ Notandum quod prima custodia resumitur hic propter quosdam actus illius primi frusti i. prime custodie de quibus prius actum est sed omnia que ponuntur hic invenies in primo folio vsque ad mutacionem gladii | |

[19] When halbschilt is assumed, fall |

Dum ducitur halpschilt cade | |

[20] Here is a bind on the part of the scholar, and all other things which were treated above, until the sword-change below.[11] |

[3v] Hic fit religatio ex parte scolaris & omnia alia de quibus superi[u]s dictum est vsque infra ad mutationem gladij. | |

[21] Here the scholar gets good counsel as to how he may resist this. And know that when the game is as shown here, then a stich must be executed as generally contained in the book, even though there are no images of this [here]. |

HIc eget scolaris bono consilio quomodo possit resiste[re] huic Et est sciendum quod quando ludus ita se habet vt hic tu[nc] debet duci stich sicut generaliter in libro continetur quamuis non sint ymagines de hoc. | |

[22] Note how the priest here changes the sword, because it was below and now it will be above; then he puts the sword to his adversary's head, which is called nucken, from which results a separation of the sword and the shield of the scholar.[12] |

NOtandum quod sacerdos mutat gladium hic quia fuit inferior nunc vero erit superior demum seorsum ducit gladium post capud adversarij sui quod nuncupatur nucken de quo generatur separatio gladij et scuti scolaris. | |

[23] Hence the verse: |

Vnde v[ersus]. Clerici sic nucken generales non nulli schutzen. | |

[24] Here the priest should take care not to delay with the sword in the slightest, lest out of this delay an action should arise which is called wrestling, but out of caution he must immediately re-establish the bind.[13] |

[4r] CAveat hic sacerdos ne faciat aliquam moram cum gladio ne generatur ex illa mora actus quidam qui vocatur luctacio sed statim debet reformare ligaturam propter cautionem | |

[24] (+) Here the first guard is resumed, the siege to which guard will be very rare, because nobody is in the habit of performing it except for the priest, or his little clients, i.e. students, and this siege is called krucke, and I counsel in good faith that he who assumes the guard should bind immediately after the siege, as it isn't good to lag, or to do any of the things by which he might be saved, or that he at least execute the same as the [besieger] did. |

⊕ HIc resumitur prima custodia cuius custodie obsessio erit valde rara quia nu[llu]s consweuit eam ducere nisi sacerdos vel sui clientuli i. discipuli & nuncupatur illa obse[ssio] krucke & consulo bona fide quod ille qui regit custodiam statim post obsessionem ligat quia non est bonum latitare vel aliquid talium faciat per quod possit salvari vel saltim ducat id quod ipse possessor ducit | |

[25] Know that the besieger must not hesitate but immediately after the siege should execute a stich; thus the adversary cannot deliberate on what he might intend and this is to be understood diligently.[14] |

Sciendum quod obsessor non debet h[esitare sed] ducat statim stich post obsess[ionem ...] tunc non potest adversarius delibe[rare quod] intendat & hoc diligenter intell[igatur] | |

[26] Here the priest binds above the scholar's siege, and immediately there follow all the preceding things, which you had before, although granted, two images you did not yet see, they follow below, where he catches sword and shield. |

[4v] HIc ligat sacerdos super obsessioenem discipili & inmediate veniunt omnia precedentia que prius habueras licet alias duas ymagines non habueris que subsecuntur vbi recipit gladium & scutum | |

[27] Note that whenever binder and bound are in conflict as here, then the bound can flee wherever he wants, if he so chooses, and it is necessary in all binds. But for this you have to be prepared, that wheresoever the bound [flees], you should pursue him. |

Nota quod quandocumque ligans & ligatus sunt in lite vt hic tunc ligatus potest fugere quocumque vult si placet & requiritur in omnibus ligaturis sed de hoc debes esse munitus vt vbicumque ligatus sis sequens eum | |

[28] Binder and bound are contrary and irate; |

Ligans ligati contrarij sunt & irati | |

[29] Here the priest teaches his student how from the above he may catch sword and shield, and know that the priest cannot free himself from such an embrace without letting go of his sword and shield. |

HIc docet sacerdos discipulum su[um quo] modo debet ex hiis superioribus recipere gladium & scutum & sciendum quod sacerdos non potest absolui a tali deprehensione sine amissione gladij & scuti | |

[30] Here the priest defends against what the scholar does above. |

[5r] HIc defendit sacerdos quod superius fecit scolaris | |

[31] (+) Here first guard is resumed, but all that is required here you have likewise [i.e. as discussed above], with the sole exception of the scholar's omission of the bind. |

⊕ HIc resumitur prima custodia sed omnia que requiruntur hic habes in eadem excepta sola obmissione ligacionis quam scolaris obmittit | |

[32] Here the scholar has omitted [all actions], as he did not bind; the scholar enters straight [away],[16] and not without merit, because whenever the one assuming the guard omits that which he has to do, the besieger has to enter as [shown] here. |

[5v] HIc obmisit scolaris quod non ligauit prossus sacerdos intrauit & non inmerito quia vbicumque regens custodiam obmittit quod suum est facere obsessor statim debet intrare vt hic | |

[33] (+) The siege is as before, but the play is different.[17] |

⊕ ¶ Obsessio vt prius sed ludus variatur | |

[34] Above, the priest besieges the scholar; here, the scholar performs the same action as the priest, but the besieger is the first to enter if the scholar omits [further action], as below. Moreover, he should take care lest the other might reach the head, as he can [do that].[18][19] |

[6r] SVperius sacerdos obsedit scolarem hic vero scolaris ducit eundem lu actum quem duxit sacerdos sed obsidentis prius est intrare si sacerdos scolaris obmittit vt infra preterea caueat hic ne alter recipiat capud quod potest | |

[35] From these above actions, the priest enters; as I said above, he should mind the head. |

ET hiis superio[ri]bus sacerdos intrat dixi caveat ergo capud | |

[36][20] (+) Here once again the first guard, viz. the one under the arm, is re-assumed, which is besieged with a certain counter that is called langort, and it is a siege of the common fencers, and the counters to this siege on the part of the one in the guard are the binds below and above. |

[6v] ⊕ HIc iterum resumitur prima custodia videlicet sub brachio* que obsedetur cum quodam contrario quod dicitur langort & est generalis obsessio cuius obssessionis contraria sunt ex parte regentis custodiam ligationes sub et supra | |

[37] Whence the verse: When langort is performed, quickly bind below or above. |

vnde versus Dum ducitur langort statim liga sub quoque supra Sed superior ligacio semper vtilior erit quam inferior | |

[38] Here will follow the game of the first guard, that is, of the binder and the bound. |

[7r] HIc erit ludus prioris custodie scilicet ligantis & ligati | |

[39] Whence the verse: Binder and bound are contrary and irate |

vnde versus Ligans ligati contrarij sunt & irati ligatus fugit ad partes laterum peto sequi | |

[41] (+) The first guard and the siege of the common [fencers][22] as above, but the game is varied at the end of the play. |

||

[42] Above

|

¶ Superior

| |

[43] Here is the change of the sword in lower position.[25] |

[8r] ¶ Hic fit mutatio gladij inferioris | |

[44] (+) First guard is resumed here, and it is besieged with the first [siege], that is halpschilt, and you will have all of the things [treated] before.[26] |

[8v] ⊕ Custodia prima resumitur hic et obsedetur cum prima possessione videlicet halpschilt et habebis omnia priora | |

[45] Verse: When halpschilt is assumed, fall |

V[ersus:] Dum ducitur halpschilt cade sub gladium quoque scutum | |

| One leaf (four plays) is missing between 8v and 9r. | ||

[46] (+) It can be seen how here is taught in which way the second ward may be displaced. And I say the second ward, because the third ward which is given to the left shoulder, does not differ much from the second. But here we speak of the second ward, which is given to the right shoulder. And from the same ward, the displacer executes the displacement called schutzen, because every ward has its protection (which is the meaning of schutzen). |

[9r] ⊕ Notandum quod hic docetur qumodo debeat secunda custodia obside & dico secunda custodia quia tertia custodia non multum differt a secunda que habetur in humero d sinistro sed hic loquimur de secunda custodia que datur humero dextro Et de eadem custodia obsessessor ducit obsessionem que vocatur schutzen quare quelibet custodia tenet vnam proteccionem i. schutzen | |

[47] Here the priest places himself in a similar way to the pupil and teaches, what will follow from these things. And you must know that (according to the true teaching of the priest) he who was the first to displace, can do three things: firstly, he can push the sword downwards and then durchtreten; secondly, he can execute a blow[28] from the right side; thirdly, he can execute a blow from the left side. Note that the opponent can do the same, even though the displacer is the first to be ready. |

Hic ponit se simili modo sacerdos ad scolarem et docet quid ex hijs fiat & sciendum quod salua doctrina sacerdotis qui prius fuit obsessorus potest tria facere Primo potest exprimere gladium deorsum & tunc durchtreten Secundo potest recipere plagam latere dextro Tertio potest recipere plagam latere sinistro Nota quod hoc idem potest facere aduersarius licet obsessessor ad hoc prius sit paratus | |

[48] Here the pupil, instructed by the priest, executes an action that is called durchtritt.[29] He might get an opportunity far a strike to the left, as it is done by general fencers, or to the right, as it is done by the priest and his youths. To counter these two possibilities, the priest may, with the sword under the arm, reach the bare hands of him who executes the abovementioned strikes, although this counter is not depicted in the example image. |

[9v] ¶ Hic scolaris instructus mediante consilio sacerdotis ducit actum quemdam qui nuncupatur durchtritt posset tamen recipisse plagam tam sinistram que ducitur ex parte dimicatorum generalium quam dexteram que consueuit duci ex parte sacerdotis & suorum iuuenium Contrarium illarum duarum viarum erit sacerdotis euntis cum gladio sub brachio* qui tunc attingit manus nudas ducentis plagas supradictas Licet contrarium istud non sit depictum in exemplum ymaginum | |

[49] Note that the priest deflects the action mentioned above while the pupil is still underway. The priest demonstrates this, depressing the pupil's bound sword, as shown here in the image. Later, you may learn what the priest will make of this if you pay careful attention etc. |

¶ Nota quod sacerdos defndit hic actum superius dictum quia cum scolaris vero esset in actu itineris sacerdos religando atque subpremendo gladium scolaris ligatum demonstrat vt hic patet per exemplum Preterea quid sacerdotem ex hijs facere contingat si diligenter inspexeris poteris edoceri & cetera | |

[50] Here, as the priest is in the act of binding from above, he teaches the pupil, what may be done against this, namely stichslac, which he generally recommends, as shown here in the example. |

[10r] ¶ Hic vero cum esset sacerdos in actu superius ligandi informat scolarem quid sit faciendum aduersus hec videlicet stichslac quod generaliter ducere consueuit Patet hic per exemplum | |

[51] (+) "the second to the right shoulder", i.e. the second ward. And note, that both the one assuming the ward and the one displacing it are in the same position as in the previous example. |

⊕ Hvmero dextrali datur altera .i. custodia & nota quod tam rector custodie quam obsessor eiusdem sunt in eodem actu vt supra exemplo proximo | |

[52] Here, the priest obits to bind or being bound, and this as an example for his students, so that these may learn what is to be done; the pupil attacks and executes an action put here in the example. |

[10v] ¶ Hic sacerdos obmisit omnes actus tam ligandi quam religandi & hoc in exemplum suorum scolarium vt possint dischere quid sit faciendum scolaris vero inuadendo eum & ducit illum actum qui ponitur hic in exemplum | |

[53] (+) same ward, but with a different displacement, and it is the one called halbschilt first treated displacing the first ward, i.e. the one under the arm. |

⊕ ¶ Eadem custodia & alia vero obsessio & est illa que appellatur halpschilt prius tacta contra primam custodiam videlicet sub brachio | |

[54] Note how many ordinary fencers will be seduced by this displacement shown here. They think they can achieve a separation of sword and shield by means of the strike executed here. This is however not the case, because the displacer tarries, which could endanger him, but this [separation] executed is depicted here for all that wish to make use of the counsel of the priest. |

[11r] NOta quod multi generales dimicatores seducuntur ista obsessione hic posita qui credunt ?fiere posse separacionem scuti & gladij mediante plaga illa que ducitur hic quod secus est quare obsessor non facit moram aliquam per quam possit periclitari sed illa hic ducta depicta est in exemplum omnibus volentibus vti consilio sacerdotis | |

[55] Here, the priest is about to execute the above strike. He teaches the pupil to turn sword and shield and to attack with the sword as here, so that the opponent may not effectively execute the strike. |

NIc vero cum sacerdos esset in actu ducendi plagam superiorem docet scolarem vertere scutum & gladium intrando cum gladio vt hic quod is qui existens adversarius plagam ducere nequiuit ad effectum | |

[56] (+) Here the priest re-adopts the first ward, i.e. the one under the arm; some things were omitted which you had not put before, as shown in the example below. |

[11v] ⊕ HIc resumit sacerdos custodiam primam videlicet sub brachio obmissis quibusdam prius non positis vt patet infra per exemplum | |

[57] You might ask how the pupil should attack the priest. And it should be known that the priest by tarrying omits all defence, in order to teach the pupil, who, as he stands, without moving sword or shield, approaches, i.e., soon he has the opportunity to strike, as shown in these images. |

¶ Posset quis dubitare quomodo scolaris inuaderet sacerdotem & sciendum quod sacerdos latitando obmittit omnes suas defensiones informando scolarem qui sicut stst non variando scutum nec gladium magis appropinquat i. paulo plus recipiendo plagam vt hic patet per ymagines | |

[58] (+) Here, the priest adopts third ward, which is displaced by the student as shown. The counter to this displacement will be a bind, and I say bind, but only above, and no other as in the example below. |

[12r] ⊕ HIc ducetur tertia custodia que per scolarem obsessa est vt hic cuius obsessionis contrarium erit ligacio & dico ligacio quare sola superior & non alia vt infra proximo exemplo | |

[59] Here, the priest binds, which is better and more profitable, because if he did aught else less occupying the adversary's sword, it would be to his loss.[30] |

¶ Hic ligat sacerdos quod est melius & vtilius quare si quid aliud faceret quominus gladius aduersarii occuparetur in dampnum suum redundaret | |

[60] From the above bind, the priest teaches his little client to get sword and shield by embracing the arms of his opponent, as shown here. |

[12v] ¶ Ex illa ligacione superius proxime tacta docet sacerdos clientulum suum circumdatis brachijs adversarij recipere gladium & scutum vt hic patet | |

[61] Here the third ward is adopted, as before, and the same displacement, but the game is varied. |

¶ Custodia tertia ducetur hic vt prius & eadem obsessio licet varietur ludus | |

[62] Here the priest teaches his little client, who executes a displacement, and he teaches him to enter if a bind is omitted. |

[13r] ¶ Hic docet sacerdos clientulum suum qui ducit obsessionem & docet eum intrare si obmittuntur ligaciones | |

[63] (+) The same third ward, viz. on the left shoulder, and the same displacement called halbschilt, as above. |

⊕ ¶ Eadem custodia tertia videlicet in humero sinistro & est eadem obsessio que vocatur halpschilt vt supra | |

[64] Note that all actions of the first ward, viz. under the arm, are here, up to the next sign of the cross. |

[13v] ¶ Nota quod omnes actus custodie prime videlicet sub brachio habuntur his vsque ad proximum signum crucis | |

[65] (+) Here the third ward is re-adopted, which will be displaced by langort, which all common fencers execute, and the counter to this displacement are two binds, one on the right above the sword, the other on the left. |

[14r] ⊕ ¶ Hic resumitur eadem tertia custodia cuius obsessio erit langort quam omnes ducunt generales dimicatores et cuius obsessionis contraria sunt due ligaciones quarum vna est in dexteris super gladium reliqua vero in sinistra | |

[66] Verse: Binder and bound are adverse and irate; |

[14v] ¶ V[ersus:] Ligans ligati contrarij sunt & irati ligatus fugit ad partes laterum peto sequi | |

[67] (+) Now that the third ward has been treated, here the fourth is treated, which will have halbschilt as its displacement, and all that you had before you will find here up to the next sign of the cross. |

⊕ ¶ Postquam determinatum est de tertia custodia hic determinat de quarta cuius obsessio erit halpschilt que omnia prius habuisti invenies hic vsque ad proximum signum crucis | |

| One leaf (four plays) is missing between 14v and 15r. | ||

[68] (+) Here the priest re-adopts the fourth ward; the displacement of this fourth ward will be the first ward, and this as an example to his pupils, as here shown in the example. |

[15r] ⊕ HIc sacerdos resumit quartam custodiam cuius custodie quarta erit obsessio custodia prima & hoc in exemplum suorum scolarium vt hic patet per exemplum | |

[69] After above the pupil has displaced the priest, here he again displaces him, and that below the arm, and note how all this has been treated with the first ward, i.e. the one under the arm, up to the next sign of the cross. |

Postquam scolaris superius obsedit sacerdotem hic iterum ipse obsedit eum & hoc sub brachium & notandum quod omnia ista tanguntur in prima custodia videlicet sub brachium vsque ad proximam signum crucis | |

[No text] |

[15v] [No text] | |

[70] (+) Here the first ward is re-adopted, viz. under the arm, and its displacement will be langort, and it is common and of limited value, and note that he who adopts the ward has three possibilities: firstly, he may bind right, above the sword; secondly, he may left, below the sword; thirdly, he may grip the sword with his hand, as shown below in the next example. |

[16r] ⊕ Hic resumitur custodia prima videlicet sub brachio cuius obsessio erit langort & est generalis & modicum valens ¶ & nota quod regens custodiam tria habet facere Primo potest ligare in dextris super gladium Secundo potest ligare in sinistris sub gladio Tertio potest comprehendere gladium manu vt infra patet exemplo proximo | |

[71] Here the priest grips - i.e. he teaches to grip - the displacer's sword. And note that the sword of said displacer may not be freed except by means of a schiltslac, where the priest's hand is struck with the shield, as below in the next example. |

[16v] HIc sacerdos deprehendit siue docet deprehendere gladium obsedentis & nota quod gladius ipsius obsedentis non potest absolui nisi mediante schiltslac vbi sacerdotis manus percutiet cum scuto vt infra exemplo proximo | |

[72] Here the pupil's sword is freed by means of a schiltschlac, and the priest should take care that the pupil does not execute a strike to his head, or a general stab, which the priest is wont to teach his students. Also, you should know that if the pupil strike to the head, execute a protection, with the sword together with the shield in the left hand, and so you will strike the shield from the hands of your adversary, as shown below in the next example. |

HIc relevatur gladius scolaris mediante schiltslac et caueat sacerdos ne scolaris ducet plagam capiti siue fixuram generalem quam sacerdos consueuit docere discipulos suos Preterea scias quod si scolaris dat plagam capiti protectionem duc gladio connexque scuto quod habetur in sinistra manu & sic frangis scutum de manibus tui aduersarij vt patet infra proximo exemplo | |

| Four leaves (sixteen plays) are missing between 16v and 17r. | ||

[73] (+) Here the priest adopts the sixth ward, which is given to the breast. And note, it is solely this stab that must be executed which is executed from the fifth ward, up to the next sign of the cross. |

[17r] ⊕ HIc sacerdos ducit sextam custodiam que datur pectori & nota quod solum illa fixura est ducenda que ducetur de quita custodia vsque ad proximum signum crucis | |

[74] Here the priest from the said sixth ward executes a stab, and a stab is also executed from the fifth ward. |

HIc sacerdos de ista custodia sexta iam dicta ducit fixuram que fixura etiam de quinta custodia est ducenda | |

[75] Here the pupil by binding resists and deflects this stab of the priest's |

[17v] HIc scolaris per religacionem resistit & defendit sacerdoti illam fixuram in proximo superius in proximo exemplo per ipsum facto | |

[76] (+) After all the wards above have been treated, here the seventh ward is treated, which is called langort, and note that there are four binds, that answer to this ward, namely two from the right, and the other two from the left. But here we speak only of the first bind above the sword, which you have all in the first ward, up to the fourth example, where sword and shield are taken. |

⊕ POstquam determinatum est de omnibus custodijs supradictis hic determinat de septima custodia que nuncupatur langort & notandum quod quatuor sunt ligaciones que respiciunt illam custodiam videlicet due liguntur de dextra parte relique vero due de sinistra parte sed loquimur hic primo de ligatura s super gladium quod habes totum in custodia prima vsque ad quartum exemplum vbi recipitur gladius & scutum | |

[77] It is to be seen how the pupil was the first to bind above the priest's sword in the preceding example. Here, the priest approaches and erects his sword and shield for the protection of the head. |

[18r] NOtandum quod scolaris prius in exemplo immediate precedenti fecit ligaturam super gladium sacerdotis hic sacerdos appropinquat erigendo gladium & scutum propter proteccionem capitis | |

[78] Here the pupil can perform shiltslac, and form the counter he can inflict a blow to the priest. |

HIc scolaris recipit shiltslac & ex contrario plagam infert sacerdoti | |

[79] Here the bound, i.e. the one below, grips sword and shield of the one above. |

[18v] HIc recipit ligatus i. inferior gladium et scutum superioris. | |

[80] Here the pupil voluntarily drops sword and shield, intending to grapple with the priest as below. |

HIc dereliquit voluntarie scolaris gladium & scutum volens luctare cum sacerdote vt infra. | |

[81] Above the priest was grabbed by the pupil and forced to grapple, which the priest may prevent as shown in the example. |

[19r] Svperius sacerdos deprehensus fuit per scolarem in modum luctationis quod sacerdos hic defendit vt patet per exemplum | |

[82] (+) Here the same final ward is adopted by the pupil. The priest counters, and it is one of the four binds, namely the one below and left, as shown in the images. |

⊕ HIc resumitur iterum illa custodia vltima que ducetur per scolarem Contrarium vero ducet sacerdos & est vna ligatura de illis quatuor ligaturis videlicet subligacio in sinistra parte vt hic patet per ymagines | |

[83] After the example above, in the following the priest is bound from below, but the pupil may reach the priest's head, because his sword was higher, and note, in all binds from below, one should guard the head, lest it be hit as here. |

[19v] POstquam superius exemplo proximo subligatum est per sacerdotem scolaris vero recipit capud sacerdotis quia fuit superior gladius suus & nota quod quandocunque subligatur capud debet teneri in custodia ne percutiatur vt hic. | |

[84] Whence the verse: When binding from below, take care that you are not deceived |

vnde versus Dum subligaueris caueas ne decipieris Dum subligatur capud ligantis recipiatur | |

[85] Above, the pupil executes a strike and hits the head of the priest, which the priest prevents here by countering, as shown in the example. |

Svperius scolaris duxit plagam percutiens capud sacerdotis quod sacerdos hic defendit quia ducit contrarium vt patet per exemplum | |

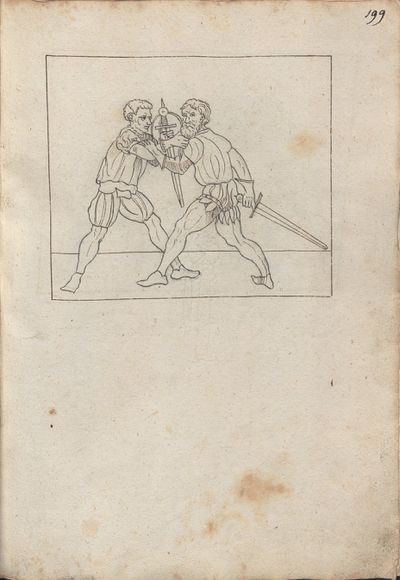

[86] (+) Here the final ward is again adopted, which is called langort, and here the priest is adopting it. But the pupil executes one of the four binds, viz. above the sword, as shown here in the example. |

[20r] ⊕ HIc iterum ducitur vltima custodia que nuncupatur langort quam in hoc loco regit sacerdos scolaris vero de hijs quatuor ligacionibus ducit vnam videlicet super gladium vt patet hic per exemplum | |

[87] After above there was a bind above the priest's sword, one may see here how the priest defends against this by an action called stich, as shown here. |

POstquam superius ligatum est super gladium sacerdotis vt supra visum est hice vero sacerdos defendit per illum actum qui vocatur sthich vt patet hic | |

[88] (+) Here the final ward is adopted, viz. langort, by the pupil. Above this ward, the priest binds with one of the four binds, viz. above the sword and to the right. And note that whenever there is a bind, the bound may flee from the binder to wherever he likes, to the left or to the right. Thence you may diligently see that if he flees, you will follow him, as in the verse: The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

|

[20v] ⊕ HIc vltima custodia videlicet Langort ducitur hic per scolarem super quam custodiam ligat sacerdos de illis quatuor ligacionibus vnam videlicat super gladium in dextris & nota quod quandocumque ligatum est ex parte ligantis ligatus potest fugere quocumque vult aut in sinistris aut in dextris vnde diligenter videas si fugere incipiat dum sequaris vnde versus ligatus fugit ad partes laterum peto sequi | |

[89] From this bind treated above, executed by the priest, the pupil flees as said above, and as shown here: Because he flees under the arm, the priest immediately follows, cutting his head like here. |

Ex illa ligatura superius tacta que ducta est per sacerdotem scolaris fugit vt supra dictum est vt patet hic quia fugit sub brachio quod immediate sequitur sacerdos percutiendo capud vt hic | |

[90] (+) Note that this is a different ward, viz. upper langort which is adopted here by the priest as an example to his pupils, and he instructs his pupil to execute this action, viz. to position himself as shown here in the example. |

[21r] ⊕ NOta quod hic est alia custodia videlicet superior Langort que ducitur hic per sacerdotem suis scolaribus in exemplum iubendo scolarem suum ducere illum actum videlicet ponendo se ad eum vt patet hic per exemplum | |

[91] Here the priest binds in order to counter the pupil and it will be one of those four binds, viz. above the sword and to the right, which you had all in another part treated above. |

HIc sacerdos religat defendendo atque contradicendo scolari & erit vna ligacio de illis quatuor ligacionibus videlicet super gladium in dextris quod habes superius totum in alijs supradictis | |

[92] After above the priest had bound, here the pupil wants to hit the priest in another way, and note that as the priest thinks that he could enter a bind, the pupil hits this same priest's arms. Note also that he not only hits the arms, but the power of this blow lies in the stab, which may also be executed here. |

[21v] POstquam superius religatum est per sacerdotem hic scolaris querit alias vias percutiendi sacerdotem & notandum quod cum credit se sacerdos posse ligare scolaris interim percutit brachia ipsius sacerdotis supradicti Nota hic etiam quod non solum percutuntur brachia sed vis istius actus siue plage consistit in fixura que potest hic duci | |

[93] Here the priest notices that his arms are endangered, and he draws himself back, intending to strike, but the pupil follows as here etc. |

HIc sacerdos sentiens brachia sua esse lesa volens ducere plagam trahendo se seorsum demum scolaris sequitur vt hic & cetera | |

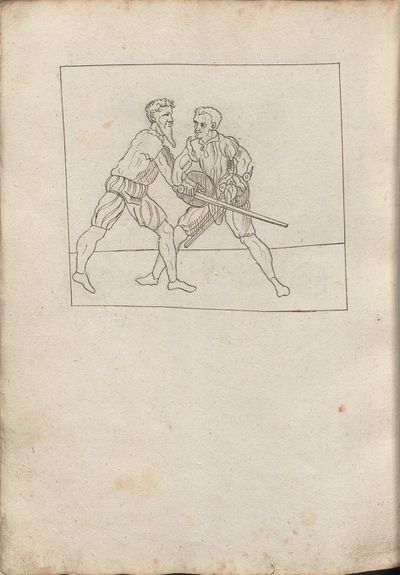

[94] (+) Here a common ward is adopted, which is called vidilpoge,[31] executed by the priest. The pupil counters it positioning himself as shown here in the images. |

[22r] ⊕ HIc ducetur quedam custodia generalis que nuncupatur vidilpoge quam regit sacerdos scolaris vero contrariando sic ponendo se ad ipsum vt patet hic per ymagines | |

[95] Then, the pupil placed his sword on the priest's arm, which also counts as a bind, as shown above. Here the priest turns the hand holding the shield and grasps the pupil's sword, as in this example. |

POstquam scolaris posuit gladium suum super brachium sacerdotis quod habetur etiam pro ligatura vt patet superius hic sacerdos vertit manum que regit scutum recipitque gladium ipsius scolaris vt in hoc exemplo | |

[96] (+) Here the same ward is re-adopted, viz. vidilpoge, executed by the priest, the pupil acting as above. |

[22v] ⊕ HIc iterum resumitur illa custodia videlicet vidilpoge & ducitur per sacerdotem scolaris ducit hic idem vt supra | |

[97] Here the priest binds as above. |

Hic religat sacerdos vt supra | |

[98] From this bind the priest does a schiltslac as treated often above, from abovementioned binds. |

[23r] Ex illa ligatura sacerdos recipit schiltslac vt supra sepius tactum est ex ligaturis supradictis | |

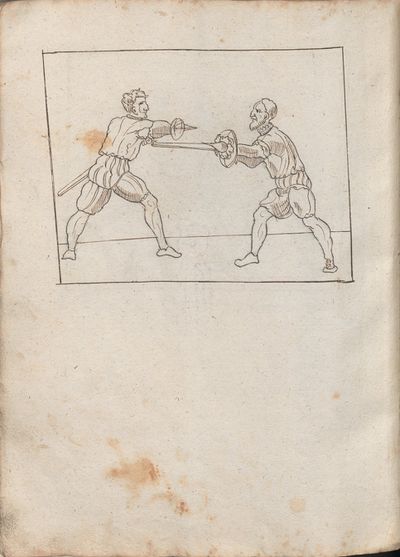

[99] (+) Note that the final ward is re-adopted, viz. langort, concerning which it should be noted that a stab is executed, by means of which the one in the ward is stabbed in the belly, i.e. he is penetrated by the sword, and note that of this paragraph not more than these two images are shown, which was the fault of the painter.[32] |

⊕ NOta quod iterum hic resumitur vltima custodia videlicat Langort circa quod notandum est quod illa fixura ducetur hic mediante qua regens custodiam fingitum super ventrem siue penetratur gladio & nota quod non est plus depictum de illo frusco quam ille due ymagines quod fuit vicium pictoris | |

[100] (+) Here, the priest adopts his special ward, viz. langort, which is displaced by the pupil, whose displacement will be halpschilt, as shown here in the example. |

[23v] ⊕ HIc ducit sacerdos suam custodiam specificatam videlicet Langort que opsedetur per scolarem cuius opsessio erit halpschilt vt patet hic per exemplum | |

[101] Here the priest puts himself under the sword of the pupil, as was often treated. |

HIc ponit se sacerdos sub gladium scolaris quod sepius prius tactum est. | |

[102] Whence the verse: If halbschilt is assumed, fall |

Unde Versus Dum ducitur halpschilt cade sub gladium quoque scutum | |

[103] After the priest above positioned himself to the scholar, the scholar here binds and steps, intending to do which follows, because you had many forms above, it is not necessary to give more examples. Therefore the verse, "the binder and the bound" etc.

|

[24r] POstquam sacerdos superius posuit se ad scolarem hic scolaris religat & calcat volens facere quod subsequitur & quia multas formas superius habetis vnde non est necesse plura ponere exempla vnde versus Ligans ligati & cetera | |

[104] Note that form this bind of the part of the pupil a useful strike is executed, viz. a separation of sword and shield of the priest, and entering (but no more of this is written in this book) as shown here in the example. |

NOta quod ex illa religacione ex parte scolaris ducetur vtilis plaga videlicet faciendo separacionem gladij & scuti sacerdotis necnon intrando vt p quod nusquam plus in libro scriptum est vt patet hic per exemplum | |

[105] (+) Here the special ward of the priest's is re-adopted, which is called langort, as seen above, and again the pupil displaces it with haloschilt, as above, but other examples follow, as shown below. |

[24v] ⊕ HIc iterum resumitur specificata custodia sacerdotis que nuncupatur Langort vt superius visum est deinde scolaris obsedit eum vt supra quod est halpschilt sed alia exempla subsecuntur vt patet infra | |

[106] Here the priest positions him to the pupil as was seen often before. |

HIc sacerdos ponit se ad scolarem vt sepius prius visum est | |

[107] It is to be noted, that the pupil is here dealing a common strike, which all common fencers are wont to deal from the position just treated, namely when binder and bound are engaged and the binder who is above goes to the head and omits a schiltslac, from which follows a strike, and the priest enters, as here. |

[25r] NOtandum quod scolaris ducit hic plagam generalem quam consueuerunt ducere omnes generales dimicatores ex supradictis proxime tactis videlicet quando ligans & ligatus sunt in lite tunc ligans qui est superior vadit post caput & obmittit schiltslac mediante quo subsequitur plaga sacerdos vero intrat ut hic | |

[108] (+) Note, that here again the special ward of the priest is assumed that is called langort, but it is a very strange displacement that is depicted here, and very rare, and you must know that this can be reduced to the first ward and to the displacement called halpschilt etc. |

⊕ NOta quod resumitur hic specificata custodia sacerdotis apellata Langort sed est valde aliena obsessio hic depicta & valde rara & sciendum quod omnia ista reducuntur ad custodiam primam et ad obsessionem que dicitur halpschilt & cetera | |

[109] Here, the priest executes the abovementioned stab, because the pupil, who has displaced in the previous example, omits all actions, because, had he bound, he would have been ?under-bound, as in the following example. |

[25v] HIc sacerdos ducit quandam fixuram prius tactam quia scolaris qui fuerat obsessor supra exemplo proximo obmittit omnes suos actos quia si religasset fuisset subportatus vt patet infra exemplo proximo | |

[110] It is to be noted, that from these actions this abovementioned stab by the priest the pupil will here bind, which is necessary, if we want the stab depicted above to be deflected. |

NOtandum quod ex hiis ista fixura superius tacta per sacerdotem erit hic quedam religacio facta per scolarem quod oportet de necessitate si volumus quod defendatur fixura superius depicta | |

| One leaf (four plays) is missing between 25v and 26r. | ||

[111] Binder and bound are adverse and irate; |

[26r] LIgans ligati contrarij sunt & irati | |

[112] (+) Here, the third ward is displaced by the special ward of the priest's that is called langort, and I counsel in good faith, that he who is performing the third ward should not at all delay his actions, because otherwise the one performing the priest's displacement will enter with a stab, which is a common practice of the priest's. |

⊕ HIc tertia custodia obsessa est cum specificata custodia sacerdotis que nuncupatur langort Et consulo bona fide quod is qui regit tertiam custodiam non protrahat suos actus alioquin is qui regit obsessionem sacerdotis intrat cum fixura quod est in communi vsu sacerdotis | |

[113] After the priest has been displaced above, the pupil does here schutzen, while the priest is executing a bind, as shown here. |

[26v] POstquam sacerdos superius obsessus fuit hic scolaris schutzet sacerdos vero ducit quandam religacionem vt hic patet | |

[114] (+) Here the fourth ward is assumed again, and it is displaced by the special ward of the priest. It is now up to the priest to displace, and the pupil enters as above, and all the actions that you had before will follow. |

⊕ HIc resumitur quarta custodia que est obsessa cum specificata custodia sacerdotis Sacerdotis est econtra obsidere aliquin scolaris intrat vt prius & veniunt omnes actus quos prius habuisti | |

[115] (+) Here again the fifth ward is assumed, and it is displaced by the special ward of the priest that is called langort, as shown in the example. |

[27r] ⊕ HIc iterum sumitur quinta custodia que etiam obsessa est cum specificata custodia sacerdotis que dicitur langort vt patet hic per exemplum | |

[116] Binder and bound are adverse and irate; |

LIgans ligati contrarij sunt & irati | |

[117] (+) Here the fifth ward is displaced, its displacement being halbschilt. And note, that the one executing the ward may do only two things: Firstly, he can execute a stab, secondly, he can execute a strike to divide shield and sword. |

[27v] ⊕ HIc obsedetur quinta custodia cuius obsessio erit halbschilt & nota regens+ +custodiam solum habet due facere primo potest ducere fixuram secundo potest ducere plagam diuidendo scutum & gladium | |

[118] Above, the pupil was displaced. Here however, he gets to do a stab, as shown in the example. |

Superius scolaris obsessessus est hic vero recipit fixuram vt patet per exemplum | |

[119] After the above stab executed by the pupil, here the priest defending does schutzen and gets the opportunity for a strike which is a general rule in the art of the priest. |

[28r] POst fixuram superius ductam per scolarem hic sacerdos defendendo schutzet & recipit plagam hoc est generalis regula in arte sacerdotis | |

[120] (+) Here the fifth ward is resumed which will be countered by halpschilt as shown in the example. |

⊕ HIc iterum resumitur quinta custodia cuius contraria erit halpschilt vt patet per exemplum | |

[121] Note, that whenever halbschilt is assumed against this fifth ward, or against the second ward, a strike from the one assuming the ward is always to be expected, which could divide sword and shield. Thence the counsel, that whenever you execute this displacement, i.e. halpschilt, you should enter with a stab without mercy. |

NOta quod quandocumque ducetur halpschilt contra illam quintam custodiam dividendo scutum & gladium cum plaga vnde consulo quod quandocumque ducis illam obsessionem videlicet halpschilt intras cum fixura sine misericordia | |

[122] Here the pupil executes a stich, because the priest omits his defense, as shown here in the example. |

[28v] HIc scolaris ducit stich, quare sacerdos obmittit suam defensionem vt patet hic per exemplum | |

[123] Here the priest deflects the action executed above, as shown here by the priest. |

HIc sacerdos defendit illum actum superius ductum vt patet hic per sacerdotem | |

[124] First, as above in the third example of the pictures, the same stab is executed by the pupil, and this stab is deflected by the priest, by means of a schiltslac, as shown here in the example. |

[29r] ¶ Prius quam superius in tertio exemplo ymaginarum fixura quedam ducta est per scolarem eandem vero fixuram sacerdos hic defendit recipiendo schilslac schiltslac ut patet hic per exemplum | |

[125] (+) Here the fifth ward is again resumed, of which much was said above, and it is to be noted that the priest is displacing the pupil with a displacement that is rare and very good, as an example for his students. And you have to know, that if the pupil executes a stab, which to execute is usually the use, the priest also must execute a stab against the stab of the pupil, because his will be more effective, entering with the left foot. But if he does not want to enter he should nevertheless retract his right foot and not omit this stab. But if the pupil displaces against him by means of halpscilt, the priest should fall below sword and shield, and then will follow those things which were seen before. |

⊕ ¶ Hic iterum se resumitur quinta custodia de qua superius dictum est sepius & est notandum quod sacerdos obsedit scolarem obsessione quandam rara & valde bona in exemplum suorum discipulorum & sciatur quod si scolaris ducet fixuram que duci consueuit de consuetudine sacerdos debet etiam ducere fixuram contra fixuram scolaris quia sua magis valet intrando cum sinistro pede si autem intrare nequiuerit cedat cum dextro pede nichillominus non obmittatur quin etiam ipsa fixura perficiatur si autem scolaris obsedit eum econtrario mediante halpscilt sacerdos cadet sub gladio & scutum & tunc superueniunt ea que prius visa sunt in custodia prima. | |

[126] Thence the verse, If halbschilt is assumed, fall |

Vnde versus Dum ducitur halpscilt cade sub gladium quoque scutum | |

[127] Here the pupil completes his stab, the priest omitting all actions. |

[29v] ¶ Hic scolaris perfecit suam fixuram sacerdos vero obmittit omnes suos actus | |

[128] Here note that the priest deflects the pupil's stab. |

¶ Hic nota quod sacerdos defendit hic fixuram scolaris | |

[129] (+) It is to be seen that here the fourth ward is again assumed, and the displacement to this fourth ward is the special langort of the priest. But the displacer should see that the one assuming the ward does not execute a strike, as it would be dangerous to tarry; therefore he should execute schuzin, and finally not omit a stab. |

[30r] ⊕ ¶ Notandum quod hic resumitur quarta custodia cuius quarte custodie obsessio est specificatum langcort sacerdotis videat autem obsessor ne regens custodiam ducet aliquam plagam quia periculosum erit sic diu latiare vnde ducat primo schuzin demum fixuram non obmittat | |

[130] Here, on the other hand, the priest is displacing the pupil, which I consider to be better, and what can be learned from anybody, because if he did not, the pupil would enter with a stab which would now be possible for him. And from these actions follows the game of the first ward, that is, of the binder and the bound, which is shown below in the first example. |

¶ Hic sacerdos econtrario obsedit scolarem quod puto melius esse quod potest ab aliquo edoceri quia si hoc non fiet scolaris ipsum invaderit cum fixura quod nunc suus erit sed ex hiis oritur ludus prime custodie videlicet ligantis & ligati quod patet infra in exemplo proximo | |

[131] Here will be the bindings that were treated often above, whence the verse "the binder and the bound are contrary and enraged" etc.

|

[30v] ¶ Hic erunt ligaciones que superius tacte sunt sepius vnde versus ligans ligati contraria sunt & irati & cetera | |

[132] From these above bindings, the pupil executes this strike lifting his sword to the head by means of a schiltslac. |

¶ Ex illis ligacionibus superius ductis scolaris ducit illam plagam per caput ducendo gladium [median]te schiltslac | |

[133] It is to be seen that the priest deflects the above strike delivered by the pupil in this way, as the pupil's sword has been below, and as he was about to deliver the strike, moving his sword, the priest has the opportunity for a strike before the pupil could put his sword to its use, as shown here in the example. |

[31r] NOtandum quod plagam superius ductam per scolare sacerdos defendit hic in hunc modum quia scolaris gladius fuit inferior & cum esset in actu ducendi plagam ducendo gladium seorsum sacerdos vero antequam scolaris ducat gladium suum ad usum debitum recipit plagam vt patet hic per exemplum | |

[134] (+) Here, the fourth ward is reassumed, whose displacement is the special langort of the priest. And it is to be noted, that whenever the game is set in this way, I counsel the one assuming the ward, and also the one displacing him, that none should delay what they have to do, i.e. on one hand the one assuming the ward, a displacement, on the other hand the one displacing, a stab. |

⊕ NIc iterum resumitur quarta custodia cuius custodie obsessio erit specificatum langort sacerdotis & notandum quod quandocunque sic se habet ludus ut hic tunc consulo tam regenti custodiam quam obsedenti eam ne quisquam eorum protrahendo obmittat quod suum est videlicet ex parte regentis custodiam obsessio & ex parte obsidentis fixura | |

[135] Above, both the one assuming the ward and the one displacing it were referred to; and because the pupil, who was the displacer, will be quicker, he executes what he should, namely first schuzin, as here, and in the next example below a stab, because the priest is omitting all actions. Thus, the one entering first will be the first to do damage to his opponent.[30] |

[31v] Superius dictum est tam de eo qui regit custodiam quam de eo qui eam pobssedit & quia prior erit scolaris qui superius fuerat obsessessor ducit quod suum est videlicet primo schuzin ut hic & infra exemplo proximo fixuram quia sacerdos omnes suos actus obmittit vnde qui prior vadit prior erit ad faciendum dampnum suo aduersario | |

[136] After the actions of the pupil's and the omission of actions of the priest's were discussed above, the priest is here omitting what he should do, and the pupil is completing the obvious attack, as shown here. |

POst quam determinatum est superius de actibus scolaris & de obmissione actuum sacerdotis hic iterum sacerdos obmittit quod suum est donec scolaris suam perducit adessentem intracionem ut patet hic | |

[137] (+) It is to be seen, that the first ward is reassumed, i.e. the one below the arm, the replacement to which is the special second ward of the priest on the right shoulder, and take note, that the one assuming the ward will schuzin without delay, otherwise his opponent will execute halbschilt which would be disastrous for the one assuming the ward. And from here will be generated all the things related to the first ward that were treated in the first quire. |

[32r] ⊕ NOtandum est quod hic resumitur custodia prima videlicet sub brachio cuius obsessio est specificata custodia secunda sacerdotis locata in humero dextro & nota quod regentis custodiam statim erit schuzin nulla mora interposita alioquin ex parte adversarij ducetur halbschilt quod erit regenti custodiam valde perniciosum & ex hiis generantur omnia que habuntur de prima custodia de quibus habetur in primo quaterno | |

[138] The priest, assuming the ward, is here executing schuzin, which will be for the reason that he was the first to be ready. And it is good counsel that the displacer will bind immediately above the sword of the one assuming the ward (which is here omitted), as shown in the example. |

HIc sacerdos qui regebat custodiam ducit schutzin quod erit proptereo quia prior erit paratus & est bene[?] consulendum quod obsidens statim ligat super gladium ipsius regentis custodiam quod hic obmittitur ut patet per exemplum | |

[139] Here will be bindings, above and below, as they occur often, thence the verse "binder and bound" etc.

|

[32v] HIc e[runt] ligationes superius & inferiores que [?sepius] ducte sun[t] [...] Vnde versus Ligans ligati & ce[tera] | |

[140] From the above bindings, (the priest) Walpurgis[33] executes a schiltslac because she was higher, and quicker to be ready. |

Ex hiis super[ioribus] allegacionibus sacerdoswalpurgis recipit schiltslac quia erat superior & prius parata | |

| One leaf (four plays) is missing after 32r. | ||

No text |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] | ||

| [No text] |

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| MS Ⅰ.33 Images | Royal Armouries | Used under the Royal Armouries Non-Commercial Licence | |

| Libr.Pict.A.83 Images | Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin | Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz | |

| Cod.Ⅰ.6.2º.4 Images | Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg | Universitätsbibliothek Augsburg | |

| Cgm 3712 Images | Bayerische Staatsbibliothek | Bayerische Staatsbibliothek | |

| Translation | Dieter Bachmann | Kunst des Fechtens | |

| Transcription | Dieter Bachmann | Index:Walpurgis Fechtbuch (MS I.33) |

Additional Resources

The following is a list of publications containing scans, transcriptions, and translations relevant to this article, as well as published peer-reviewed research.

- Binard, Fanny; Daniel Jaquet (2016). "Investigation on the collation of the first Fight book (Leeds, Royal Armouries, Ms I.33)." Acta Periodica Duellatorum 4(1): 3-21. doi:10.1515/apd-2016-0001.

- Cinato, Franck; André Surprenant (2009). Le Livre de l'art du Combat: Liber de arte dimicatoria. Édition critique du Royal Armouries MS. I.33, collection Sources d'Histoire Médiévale nº39. Paris: CNRS Editions. ISBN 978-2-271-06757-9.

- Dawson, Timothy (2009). "The Walpurgis Fechtbuch: An Inheritance of Constantinople?." Arms & Armour 6(1): 79-92. doi:10.1179/174962609X417536.

- Deacon, Jacob Henry (2016). "Prologues, Poetry, Prose and Portrayals: The Purposes of Fifteenth Century Fight Books According to the Diplomatic Evidence." Acta Periodica Duellatorum 4(2): 69-90. doi:10.36950/apd-2016-014.

- Eads, Valerie; Rebecca L. R. Garber (2014). "Amazon, Allegory, Swordswoman, Saint? The Walpurgis Images in Royal Armouries MS I.33." Can These Bones Come to Life? Insights from Reconstruction, Reenactment, and Re-creation 1: 5-23. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-1-937439-13-2.

- Forgeng, Jeffrey L. (2003). The Medieval Art of Swordsmanship: A Facsimile & Translation of Europe's Oldest Personal Combat Treatise, Royal Armouries MS I.33 (Royal Armouries Monograph). Union City, CA: Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 1-891448-38-2. (Corrigenda)

- Forgeng, Jeffrey L. (2012). The Illuminated Fightbook Royal Armouries Manuscript I.33. Extraordinary Editions. ISBN 978-0-9573046-0-4.

- Forgeng, Jeffrey L. (2018). The Medieval Art of Swordsmanship: Royal Armouries MS I.33. Royal Armouries. ISBN 978-0948092855.

- Forgeng, Jeffrey L. (2021). Das Tower-Fechtbuch. Ein Meisterwerk der mittelalterlichen Kampfkunst. Damstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Gräf, Julia (2017). "Fighting in women's clothes: The pictorial evidence of Walpurgis in Ms. I.33." Acta Periodica Duellatorum 5(2): 47-71. doi:10.1515/apd-2017-0008.

- Hester, James (2012). "Home-Grown Fighting: A Response to the Argument for a Byzantine Influence on MS I.33." Arms & Armour 9(1): 76-84. doi:10.1179/1741612411Z.0000000008.

- Hester, James (2012). "A Few Leaves Short of a Quire: Is the 'Tower Fechtbuch' Incomplete?." Arms & Armour 9(1): 20-25. doi:10.1179/1741612411Z.0000000003.

- Ijäs, Antti (2022). Study of the Language and Genre of Royal Armouries MS I.33 [Unpublished dissertation]. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto. https://helda.helsinki.fi/items/e91439c3-6354-4bd8-9203-8df6aaa0d196

- Kellett, Rachel E. (2012). "Royal Armouries MS I.33: The Judicial Combat and the Art of Fencing in Thirteenth- and Fourteenth- Century German Literature." Oxford German Studies 41(1): 32-56. doi:10.1179/0078719112Z.0000000003.

- Leblanc, Hélène; Franck Cinato (2023). "Scholastic Clues in Two Latin Fencing Manuals: Bridging the gap between medieval and renaissance cultures." Acta Periodica Duellatorum 11(1): 39-64. doi:10.36950/apd-2023-004.

- Morini, Andrea; Riccardo Rudilosso (2012). Manoscritto I.33. Rome: Il Cerchio Iniziative Editoriali.

- Singman, Jeffrey L. (1998). "The Medieval Swordsman: a 13th Century German Fencing Manuscript." Royal Armouries Yearbook 2: 129-136.

References

- ↑ Hester (2012).

- ↑ The introductory verse is added on the top margin of the page in a 15th-century hand. The distichon was apparently added in the 15th century, when the manuscript was still kept in a monastery library. It seems to express a disparaging view of “armed clerics” and clearly also refers to the depiction of a female fencer on the last folium. This verse is attested in print in the 16th century, and there attributed to Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II, 1405–64), as follows:

- Andreas Gärtner, Proverbialia dicteria (1574): “Non audet Stygius Pluto tentare, quod audet Eff renis monachus plenaque fraudis anus” (cited after Wilhelm Binder, Novus Thesaurus Adagiorum Latinorum, 1861 who off ers the German paraphrase “Wo der Teufel nicht selbst hin will, schickt er entweder einen Pfaff en, oder ein altes Weib.”)

- Holinshed's Chronicles (1577): “Æneas Sylvius (and before him many more driving upon the like argument) dooth saie in this distichon: Non audet Stygius Pluto tentare, quod audent / Eff rænis monachus, plenaque fraudis illa. Meaning Mulier, a woman.”

- ↑ Gunterrodt: Tres quae praecedunt, reliquae tantum fugientes.

- ↑ It is suggestive that the author (if we accept the instructor in the verses and in the manual as the same person) is called cler[ic]us “the cleric” (or “the clerk”) three times in these verses, but never in the text; conversely, the text consistently calls him sacerdos, and never clericus (Middle Latin use of clerus for clericus is noted in Du Cange's Glossarium). It is almost as if he had composed the verses as a mnenomic orally at an earlier time, before envisaging the project of creating this manual, when he was younger and not yet ordained as a priest. Latin clericus renders MHG pfaffe, which may could to either a priest, a deacon or a member of the minor orders. Note that it is not unusual to find the designation pfaffe associated with fencing masters of the late medieval tradition, so Hanko Döbringer (still in the 14th century) and Hans Lecküchner (in the later 15th century).

The interpretation of the name Lutegerus in the verse on fol. 1v depends on the interpretation of the verse of which it forms a part. This verse is very difficult to interpret in a number of ways. In fact, nothing about it is entirely clear to me.

- ↑ Are we to understand that the seven guards are the same as the “seven parts”, and of these three “precede” (or “go forward” as antonym to fugiunt?) and the remaining (i.e. four) “flee” or “go backward” in some way? CS translate Il y en a trois qui avancent, tandis que les autres replient. But “reply” isn't really what a custodia does, the system has the separate term obsessio just for that, and there is nothing in the subsequent material that would somehow suggest that some of the guards have a function of replying or reacting to the others. It is also anyone's guess how the guards are to be grouped. One reasonable assumption would be the the first four, shown on 1r, as opposed to the final three, shown on 1v. There is, in fact, a conceptual difference between the groups, guards 1-4 as described in the manual initiate a strike, while 5 and 6 initiate a thrust, and 7 is a special case, inviting a bind instead of posing a direct threat.

Now, the verse goes on to say “these seven (parts, guards) are done by the common fencers”, followed by “the cleric holds the opposite, and Luitger holds the middle”. This may be interpreted in a number of ways. It is important to note that neither medium nor oppositum is used in any technical sense anywhere in the manual outside of this verse.

CS have Le clerc est a l'opposé et Luitger à mi-chemin “the cleric is opposite, and Luitger is at halfway”, i.e. they here treat “the cleric” as a different person from Luitger. In the reading of Ukert, Lutegerus is a reference by name to a notable “common fencer”, so that the cleric holding “the opposite” would presumably be preferable to the “common fencer” Luitger who holds merely “the middle”.

It does seem more probable to me, however, that the entire line refers to a single person, clerus Lutegerus, who holds “both the opposite and the middle” and that this statement, as a whole, contrasts with the “common fencers” mentioned in the preceding line. Note that this would mean that the author here employs hyperbaton (the separation of the two associated nominatives), in apparent aspiration to a “poetic” mode of speech entirely absent from the rest of the “verses”.

I am unsure whether the terms oppositum and medium should be interpreted in a figurative way, as it were “he is in possession of the counter and the means”, or in a strictly spatial sense, as it were “he holds against (his opponent)” and at the same time “he holds or occupies the center” between the fencers. This latter interpretation strikes me as a useful description of the “conflict of binder and bound” referenced throughout the manual, but it must be admitted that a discussion in the terms used in the verse is not repeated anywhere in the following text. It nevertheless remains my preferred reading, against both CS and Ukert, that “clerus Lutegerus” here refers to a single person, and most likely the manual's author himself (compare the discussion of de Alkersleiben below).

- ↑ Gunterrodt (1579) read this name as Albenslaiben recognising it as the name of the “ancient stem and most famous family” (vetustissima prosapia et clarissima familia) of Alvensleben. Ukert, on the other hand, reads Alkersleiben. Both Gunterrodt and Ukert recognised the word as a personal name (while a reading albersleiben is due to Forgeng, who identified the word as a fencing term, a “proto-Liechtenauerian” version of Alber). Alkersleiben is clearly more consistent with the manuscript, and Gunterrodt's reading should perhaps be considered an emendation, inserting the more familiar name of Alvensleben, a prominent noble family of Brandenburg in Gunterrodt's time (which also had held extensive possessions already in the 1300s). For Gunterrodt, it was obvious that the author of the manuscript must have been a nobleman who had retired to a monastery in his old age, and he took his reading as a confirmation of the association with nobility without positively identifying the name as referencing the manual's author.

However, reading de Alkersleiben (with Ukert) we have a reference to the Thuringian village of Alkersleben (recorded in the 13th century as Alkesleibin), at the time of merely local importance as the site of a manor and a deanery. Alkersleben is some 200 km to the north of the parts of Franconia affected by the Second Margravian War, the presumed area of production of our manuscript. Ukert interprets both Lutegerus and de Alkersleiben as the names of “common fencers” (generales dimicatores, “gemeine Fechtmeister”). This depends entirely on the context we give to the occurrence of the names, in the case of de Alkersleiben: Non ducat aliquam plagam quod probat de Alkersleiben “He should not deliver any strike, as recommended by de Alkersleiben” – are we to understand that this is a counsel against the recommendation to “deliver a strike” attributed to a notable “common fencer” known as de Alkersleiben, or are we much rather to understand that the counsel not to deliver a strike is attributed to the highly profi cient fencer known by this name, which would amount to nothing less than yet another reference by the author to himself in the third person? If we are ready to interpret Lutegerus in this way, I see no obstacle to adopt the same position here, which would give us an author Clericus Lutegerus de Alkersleiben, or, in German, Pfaffe Luitger von Alkersleben. Incidentially, the term nucken happens to be more consistent with a Thuringian rather than a Franconian origin of whoever is responsible for coining it.

- ↑ CS praise this image as “one of the most beautiful aesthetic successes” of the codex. The postures are drawn very carefully, including an indication that each fencer has the right foot forward, a detail that will not be evident in later figures. The final (and let's face it, rather awkward) paragraph is in hand B and alludes to changed dynamics that arise if first guard is answered with first guard.

- ↑ This is written vertically on the right margin. The image is damaged, but it is the first of dozen identical images illustrating “overbind” (see §11). This image is also the first instance of a “change of perspective” (i.e. the position of fencers is inverted; this is done on purpose in order to show the hand position of the fencer).

- ↑ i.e. Showing the schiltslac.

- ↑ The verse is written between the two images on the left side (the side of the fencer performing the technique).

- ↑ The first three images of the second play are equivalent to the first play. This is made explicit in the text, the sword-change in the following image being shown as a counter to the overbind. But note the explicit depiction of step with the left foot forward for the overbind (based on the position of the rear foot), a detail absent from the equivalent situation as shown in 2v.

- ↑ The two paragraphs are arranged on the left and on the right, referring to the scholar and the priest, respectively. The image shows the situation after the sword-change (mutatio gladii); the scholar is instructed to counter this with a stich, but this isn't pursued further. This is presumably the action depicted in 10r, where it is, however, referred to as stichslac. The play here instead continues with the action of nucken performed by the priest immediately after the sword-change. The last part of the second paragraph is already in reference to the following image on the next page, i.e. the one depicting the priest's nucken. The word is written nucken in prose, but then nukcen in the verse: is this a simple error, or is the creation of an apparent rhyme with schutzen significant?

- ↑ The paragraph is centered on the page above the image, perhaps added as an afterthought as the scribe realised that the description intended for this image has already been given on the previous page. This image is unique in the book, and CS point out correctly a mistake on the part of the illustrator, who has given the priest two left hands.

- ↑ The second paragraph is written on the right margin. The krucke is introduced as an alternative reaction to first guard (other than halbschilt), and advertised as a speciality of the priest's system. This position at the same time covers the right side (threatened by first guard) and threatens a thrust to the opponent's sword side. CS interpret the image as reflecting the fencers maintaining eye contact under the shield. I do not think this is the case: Krucke should be performed with a step to the right, and eye-contact is maintained in a line passing left of the shield.

- ↑ The first occurrence of the ligans-ligati verse, written on the left margin; note that the verse is grammatically dubious, you would expect ligans ligatusque or something similar. The text is distracted from the play at hand to give general advice on the bind, but 5v below can be seen as immediately following the establishment of the bind here.

- ↑ prossus for prorsus or prosus “straight ahead, directly, truly”; even though the literal meaning of the adverb is “straight ahead”, the intended meaning is not necessarily spatial but rather temporal, i.e. the priest enters “straight away” as the scholar omits the bind, but not necessarily in a straight line.

- ↑ The short gloss is written without the initial usually used for new sections, and squeezed between the feet of the fencers in the above image.

- ↑ The text has a stray lu, the beginning of the word ludem, amended to actum on the fly (because ludus “game” is used for a sequence of techniques, while actus refers to a single tempo, in this case the assumption of krucke). The addition of scholaris as the subject of obmittit is in the later hand B.

- ↑ The technique described is an example of Fühlen in the bind, the priest may thrust to the belly in the (strong) bind, but the scholar has the opportunity to release the bind and strike to the head, scoring an easy double-hit. As soon as the attacker feels he is losing the bind, he has to interrupt the attack and perform the counter shown in the next image.

- ↑ The top image is without text (and without lineation). It shows a counter against the double-hit discussed under the previous image. The counter is worth closer scrutiny, as it does not recur (but compare the counter on 19v as conceptually related).

- ↑ This page once again shows the overbind-schiltslac sequence; there is a change of perspective from the previous. The lower image has lineation but no text. On the bottom of the page, Johann Herbart (Herwart) of Würzburg, who acquired the manuscript in the 1550s, has left his name.

- ↑ i.e. langort

- ↑ The text has been re-traced in darker ink, according to CS by hand C (but closely following the original ductus of hand A).

- ↑ This is a rare instance of an actively established underbind (followed immediately by a sword-change), the only other example of this being 19r.

- ↑ The text is written between the two images, on the right side (the side of the fencer performing the technique). There is no other text (or lineation) on the page. The prior image (the underbind) is closely reproduced in the top image, the only difference in posture being the scholar's having moved his shield to his left hand side. It thus shows the same situation as the top of 7r (with the role of the two fencers reversed), i.e. the overbind, but in this case, the Vor is held not by the fencer in the overbind, but by the fencer in the underbind, who next performs sword-change, so that the sequence on 8r becomes a repetition of 3v.

- ↑ This “play” on the final page of the first quire has no new material, but it is important as the only instance of the frequently used action of “falling under” being shown from the reverse perspective, showing the hands of the fencer in halpschilt. The variant possessio for obsessio here occurs for the last time (otherwise only as possessor on 4r, and in the late addition on 2r).

- ↑ The verse is written between the two images, on the right side (the side of the fencer performing the technique).

- ↑ recipere plagam: to execute (not to receive) a blow. Probably intended as 'receive the opportunity to strike'.

- ↑ durchtritt: a step to the side seems intended; for the (preferable) action depicted, we would expect 'to the left', so dexteram may be taking the opponent's view.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 dampnum for damnum

- ↑ vidilpoge = "fiddle-bow".

- ↑ fingitur for figitur; fuit vicium pictoris: Here is evidence that the author is not identical with the draftsman.