|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Walpurgis Fechtbuch (MS I.33)"

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

|- | |- | ||

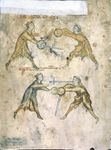

| − | | rowspan="4" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="4" | [[File:MS I.33 01r.jpg|300px|center|Folio 1r]] |

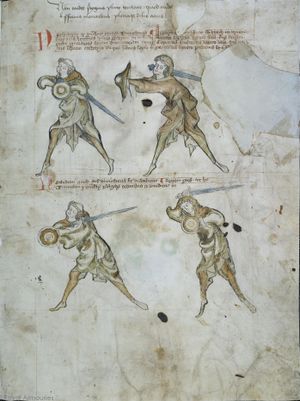

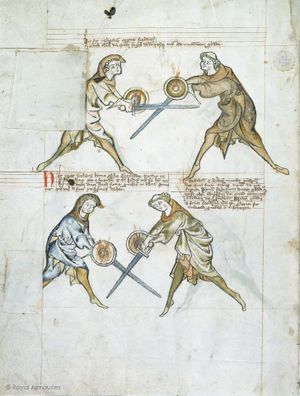

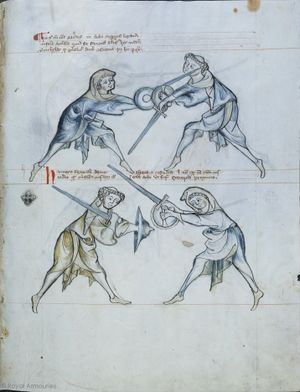

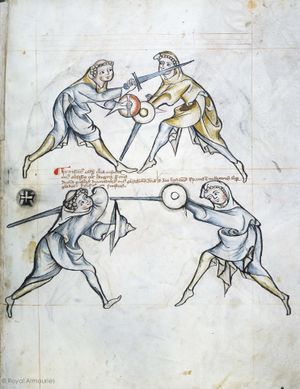

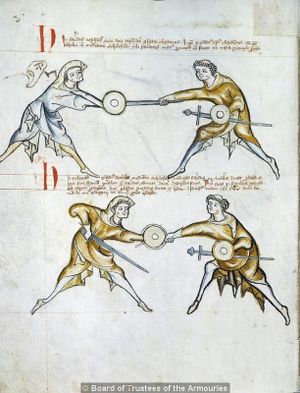

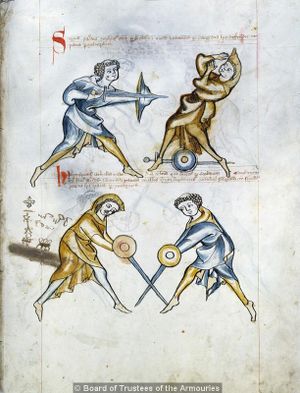

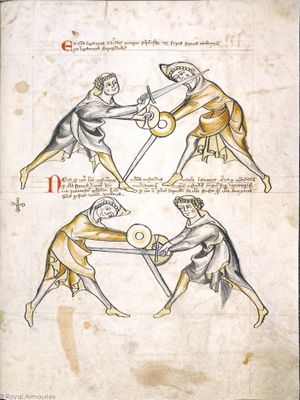

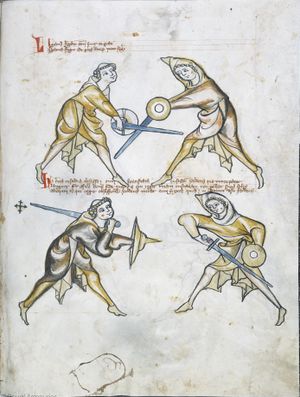

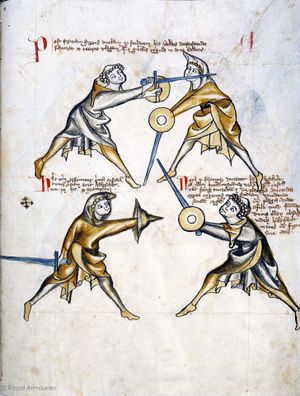

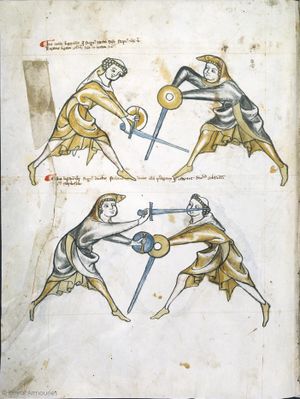

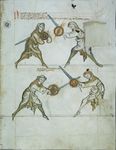

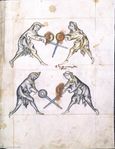

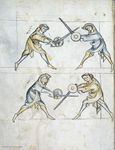

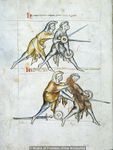

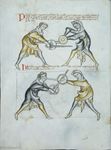

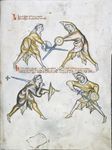

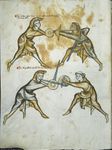

| − | | <p>[1] '' | + | | <p>[1] ''Stygian Pluto dares not attempt what a rogue monk and a treacherous hag dare do.''<ref>The introductory verse is added on the top margin of the page in a 15th-century hand. The distichon was apparently added in the 15th century, when the manuscript was still kept in a monastery library. It seems to express a disparaging view of “armed clerics” and clearly also refers to the depiction of a female fencer on the last folium. This verse is attested in print in the 16th century, and there attributed to Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II, 1405–64), as follows: |

| − | |||

* Andreas Gärtner, Proverbialia dicteria (1574): “''Non audet Stygius Pluto tentare, quod audet Eff renis monachus plenaque fraudis anus''” (cited after Wilhelm Binder, ''Novus Thesaurus Adagiorum Latinorum'', 1861 who off ers the German paraphrase “Wo der Teufel nicht selbst hin will, schickt er entweder einen Pfaff en, oder ein altes Weib.”) | * Andreas Gärtner, Proverbialia dicteria (1574): “''Non audet Stygius Pluto tentare, quod audet Eff renis monachus plenaque fraudis anus''” (cited after Wilhelm Binder, ''Novus Thesaurus Adagiorum Latinorum'', 1861 who off ers the German paraphrase “Wo der Teufel nicht selbst hin will, schickt er entweder einen Pfaff en, oder ein altes Weib.”) | ||

| Line 104: | Line 103: | ||

|- | |- | ||

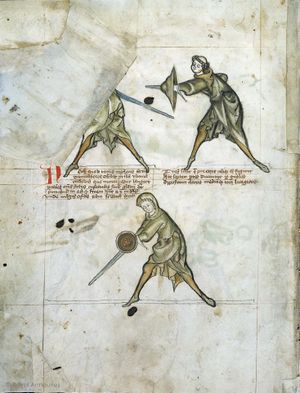

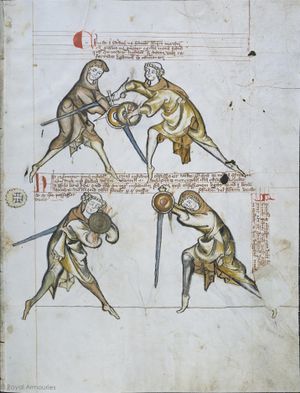

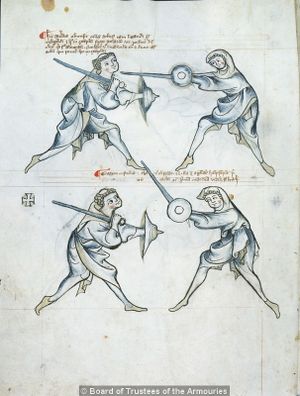

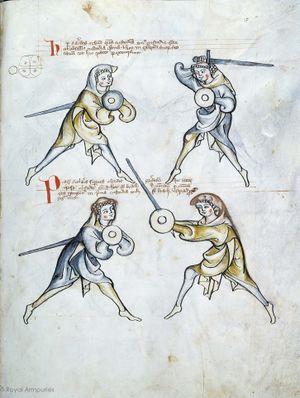

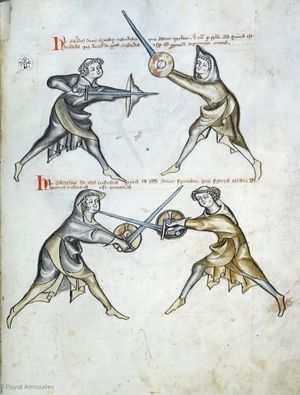

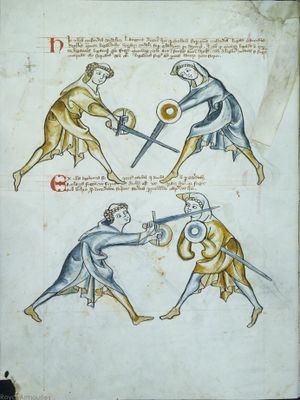

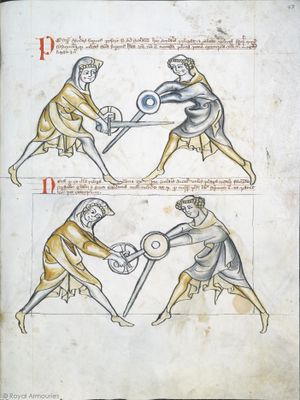

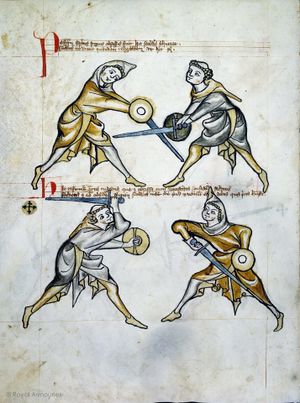

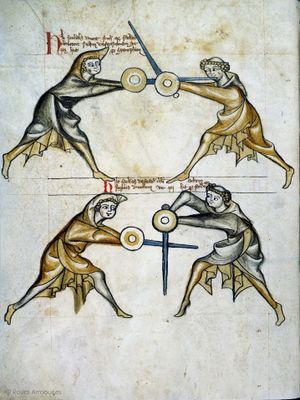

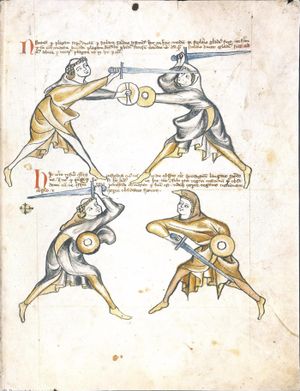

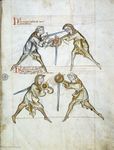

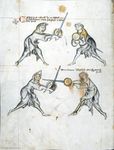

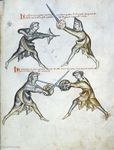

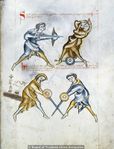

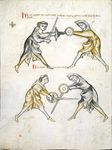

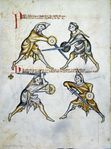

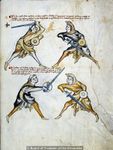

| − | | <p>[2] | + | | <p>[2] Note how in general all fencers, or all men who hold a sword in hand, even when ignorant in the art of fencing, make use of these seven guards, on which we have seven verses:</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 01r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 01r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[3] {{red|Seven | + | | <p>[3] {{red|Seven guards there are, under the arm the first<br/>On the right shoulder the second, the third on the left<br/>To the head give the fourth, to the right side the fifth<br/>To the breast give the sixth, and as the final one have ''langort''.}}</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 01r.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 01r.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

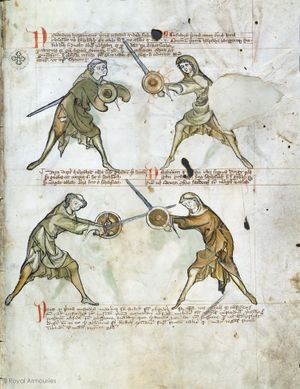

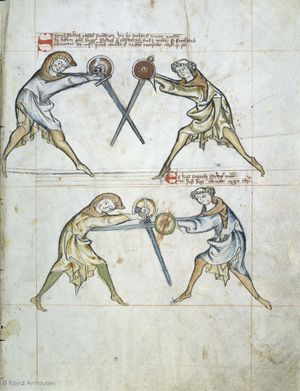

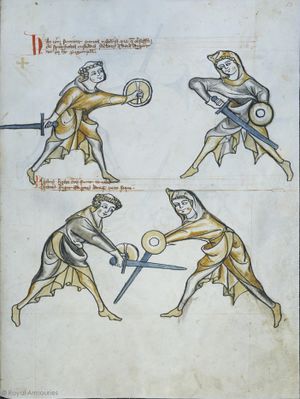

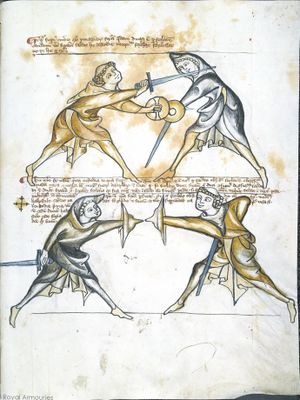

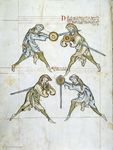

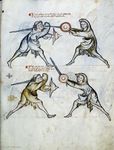

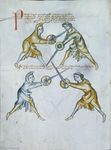

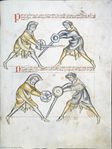

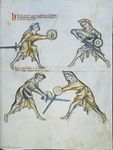

| − | | <p>[4] | + | | <p>[4] Note that the art of fencing is described as follows: Fencing is the ordering of various strikes, and it is divided into seven parts as here.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 01r.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 01r.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | ||

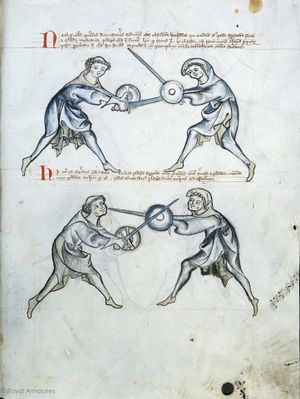

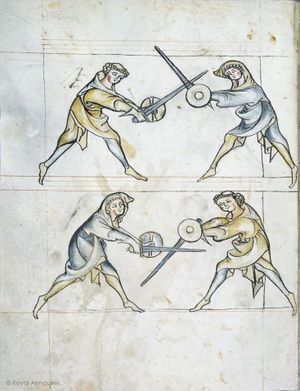

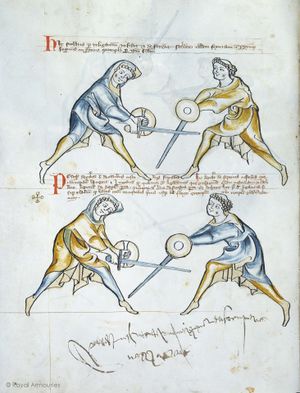

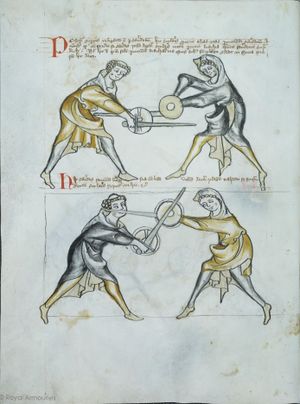

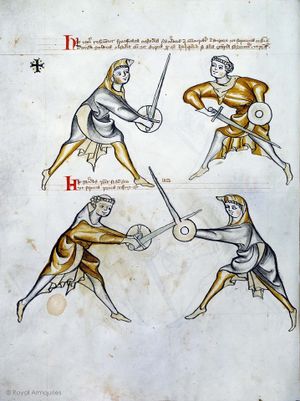

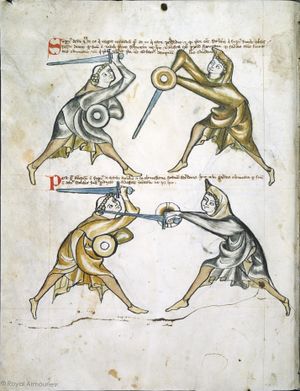

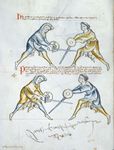

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 01v.jpg|300px|center|Folio 1v]] |

| − | | <p>[5] Note | + | | <p>[5] Note that the whole core of the art of fencing consists in this final guard which is called ''langort'', because in it, all actions of the guards or the sword terminate, i.e. they end in it and not in the others, therefore consider it more than the the above-mentioned first one.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 01v.jpg|1|lbl=1v}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 01v.jpg|1|lbl=1v}} | ||

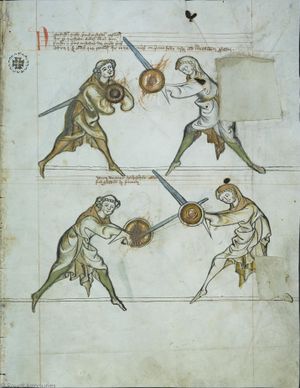

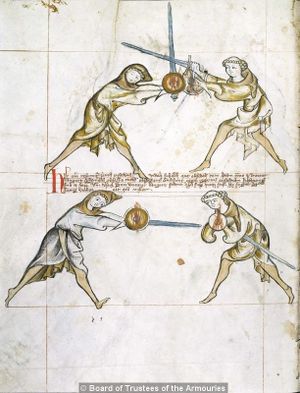

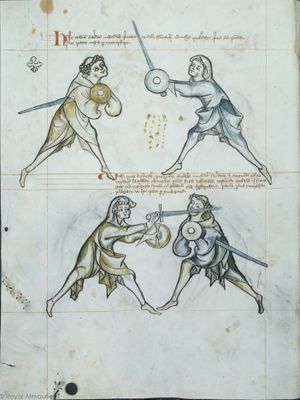

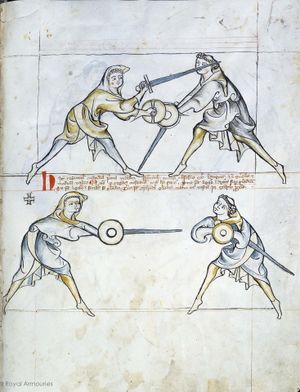

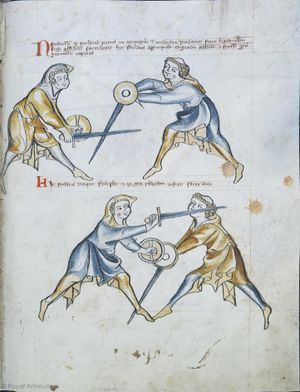

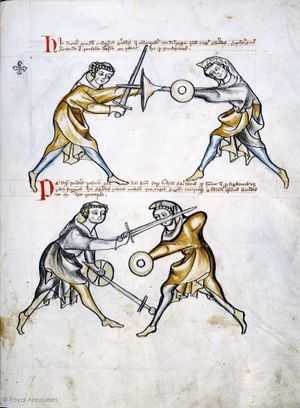

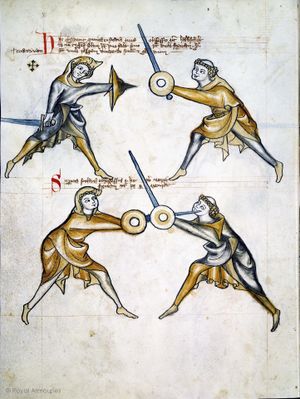

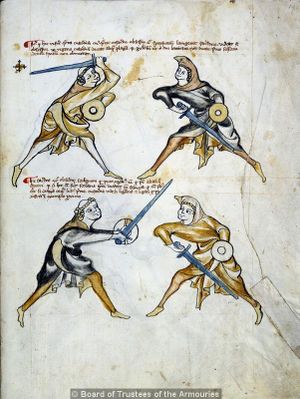

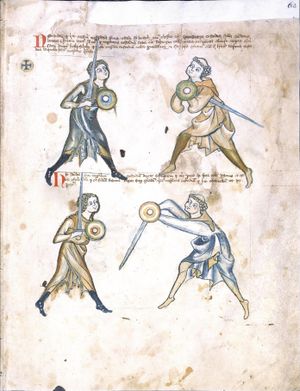

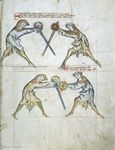

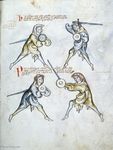

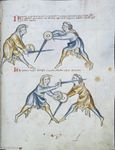

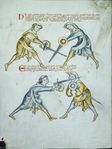

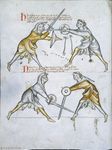

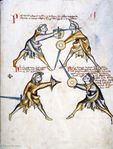

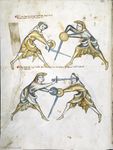

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[6] {{red| | + | | <p>[6] {{red|There are three which go forward, and the remaining then flee.<ref>Gunterrodt: ''Tres quae praecedunt, reliquae tantum fugientes''.</ref><br/>These seven parts are executed by the common [fencers],<br/>Luitger the cleric<ref>It is suggestive that the author (if we accept the instructor in the verses and in the manual as the same person) is called ''cler[ic]us'' “the cleric” (or “the clerk”) three times in these verses, but never in the text; conversely, the text consistently calls him ''sacerdos'', and never ''clericus'' (Middle Latin use of ''clerus'' for ''clericus'' is noted in Du Cange's ''Glossarium''). It is almost as if he had composed the verses as a mnenomic orally at an earlier time, before envisaging the project of creating this manual, when he was younger and not yet ordained as a priest. Latin ''clericus'' renders MHG ''pfaffe'', which may could to either a priest, a deacon or a member of the minor orders. Note that it is not unusual to find the designation ''pfaffe'' associated with fencing masters of the late medieval tradition, so [[Hanko Döbringer]] (still in the 14th century) and [[Hans Lecküchner]] (in the later 15th century). |

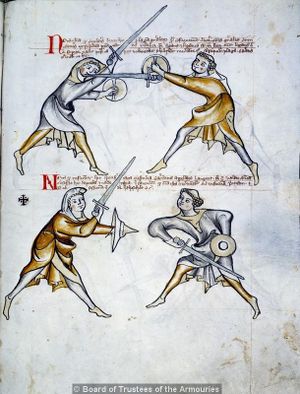

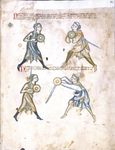

| + | |||

| + | The interpretation of the name Lutegerus in the verse on fol. 1v depends on the interpretation of the verse of which it forms a part. This verse is very difficult to interpret in a number of ways. In fact, nothing about it is entirely clear to me.</ref> holds the opposite and the middle.<ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Are we to understand that the seven guards are the same as the “seven parts”, and of these three “precede” (or “go forward” as antonym to ''fugiunt''?) and the remaining (i.e. four) “flee” or “go backward” in some way? CS translate ''Il y en a trois qui avancent, tandis que les autres replient''. But “reply” isn't really what a ''custodia'' does, the system has the separate term ''obsessio'' just for that, and there is nothing in the subsequent material that would somehow suggest that some of the guards have a function of replying or reacting to the others. It is also anyone's guess how the guards are to be grouped. One reasonable assumption would be the the first four, shown on 1r, as opposed to the final three, shown on 1v. There is, in fact, a conceptual difference between the groups, guards 1-4 as described in the manual initiate a strike, while 5 and 6 initiate a thrust, and 7 is a special case, inviting a bind instead of posing a direct threat. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Now, the verse goes on to say “these seven (parts, guards) are done by the common fencers”, followed by “the cleric holds the opposite, and Luitger holds the middle”. This may be interpreted in a number of ways. It is important to note that neither ''medium'' nor ''oppositum'' is used in any technical sense anywhere in the manual outside of this verse. | ||

| + | |||

| + | CS have ''Le clerc est a l'opposé et Luitger à mi-chemin'' “the cleric is opposite, and Luitger is at halfway”, i.e. they here treat “the cleric” as a different person from Luitger. In the reading of Ukert, Lutegerus is a reference by name to a notable “common fencer”, so that the cleric holding “the opposite” would presumably be preferable to the “common fencer” Luitger who holds merely “the middle”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It does seem more probable to me, however, that the entire line refers to a single person, ''clerus Lutegerus'', who holds “both the opposite and the middle” and that this statement, as a whole, contrasts with the “common fencers” mentioned in the preceding line. Note that this would mean that the author here employs ''hyperbaton'' (the separation of the two associated nominatives), in apparent aspiration to a “poetic” mode of speech entirely absent from the rest of the “verses”. | ||

| + | |||

| + | I am unsure whether the terms ''oppositum'' and ''medium'' should be interpreted in a figurative way, as it were “he is in possession of the counter and the means”, or in a strictly spatial sense, as it were “he holds ''against'' (his opponent)” and at the same time “he holds or occupies the ''center''” between the fencers. This latter interpretation strikes me as a useful description of the “conflict of binder and bound” referenced throughout the manual, but it must be admitted that a discussion in the terms used in the verse is not repeated anywhere in the following text. It nevertheless remains my preferred reading, against both CS and Ukert, that “clerus Lutegerus” here refers to a single person, and most likely the manual's author himself (compare the discussion of ''de Alkersleiben'' below).</ref>}}</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 01v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 01v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

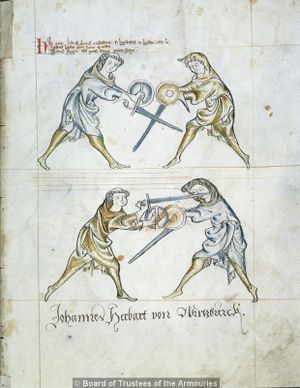

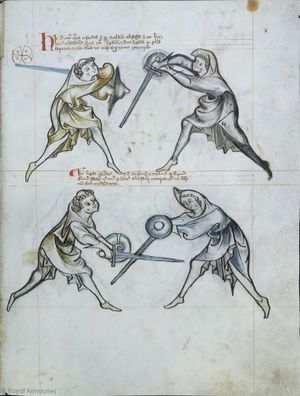

| − | | rowspan=" | + | | rowspan="5" | [[File:MS I.33 02r.jpg|300px|center|Folio 2r]] |

| − | | <p>[7] '''(+)''' | + | | <p>[7] '''(+)''' Note, here is contained the first guard, viz. the one under the arm, and the siege is ''halbschilt''. And I give the sensible counsel that the one under the arm should not execute any strike, as recommends ''de Alkersleiben'',<ref>Gunterrodt (1579) read this name as ''Albenslaiben'' recognising it as the name of the “ancient stem and most famous family” (''vetustissima prosapia et clarissima familia'') of Alvensleben. Ukert, on the other hand, reads ''Alkersleiben''. Both Gunterrodt and Ukert recognised the word as a personal name (while a reading ''albersleiben'' is due to Forgeng, who identified the word as a fencing term, a “proto-Liechtenauerian” version of Alber). ''Alkersleiben'' is clearly more consistent with the manuscript, and Gunterrodt's reading should perhaps be considered an emendation, inserting the more familiar name of Alvensleben, a prominent noble family of Brandenburg in Gunterrodt's time (which also had held extensive possessions already in the 1300s). For Gunterrodt, it was obvious that the author of the manuscript must have been a nobleman who had retired to a monastery in his old age, and he took his reading as a confirmation of the association with nobility without positively identifying the name as referencing the manual's author. |

| + | |||

| + | However, reading ''de Alkersleiben'' (with Ukert) we have a reference to the Thuringian village of Alkersleben (recorded in the 13th century as ''Alkesleibin''), at the time of merely local importance as the site of a manor and a deanery. Alkersleben is some 200 km to the north of the parts of Franconia affected by the Second Margravian War, the presumed area of production of our manuscript. Ukert interprets both ''Lutegerus'' and ''de Alkersleiben'' as the names of “common fencers” (''generales dimicatores'', “gemeine Fechtmeister”). This depends entirely on the context we give to the occurrence of the names, in the case of ''de Alkersleiben'': ''Non ducat aliquam plagam quod probat de Alkersleiben'' “He should not deliver any strike, as recommended by ''de Alkersleiben''” – are we to understand that this is a counsel against the recommendation to “deliver a strike” attributed to a notable “common fencer” known as ''de Alkersleiben'', or are we much rather to understand that the counsel not to deliver a strike is attributed to the highly profi cient fencer known by this name, which would amount to nothing less than yet another reference by the author to himself in the third person? If we are ready to interpret ''Lutegerus'' in this way, I see no obstacle to adopt the same position here, which would give us an author ''Clericus Lutegerus de Alkersleiben'', or, in German, ''Pfaffe Luitger von Alkersleben''. Incidentially, the term ''nucken'' happens to be more consistent with a Thuringian rather than a Franconian origin of whoever is responsible for coining it.</ref> for the reason that he cannot reach the upper part; if [he should aim] lower, it would be pernicious to [his] head. But the besieger by entering could invade him at any time if he omits what is being held, as is written below.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|1|lbl=2r}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|1|lbl=2r}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[8] Verse:<br/>{{red|The first | + | | <p>[8] Verse:<br/>{{red|The first guard has a two-fold counter:<br/>The first counter is ''halbshilt'', the second is ''langort''.}}</p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| − | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | + | |- |

| + | | <p>[9] {{red|When ''halbschilt'' is executed, fall underneath sword and shield.<br/>If he is common, he will reach [for] the head, then you should do a ''stichschlac''.<br/>If he binds and presses, you should counter with a ''schiltschlac''.}}</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[10] Note that the one who lies above will direct a strike to the head without ''schiltslac'' if he is common. But if you want to be informed by the counsel of the priest, bind and press. </p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[11] ''Note that the first guard, viz. the one under the arm, can besiege itself, so that the one besieging with this guard can besiege the first guard; but nevertheless the one assuming first guard against the besieger can besiege the siege which corresponds with the siege that is called ''halbschilt'', differing in this, that the sword is extended below the arm and above the shield so that the hand holding the shield is included in the hand holding the sword.''<ref>CS praise this image as “one of the most beautiful aesthetic successes” of the codex. The postures are drawn very carefully, including an indication that each fencer has the right foot forward, a detail that will not be evident in later figures. The final (and let's face it, rather awkward) paragraph is in hand B and alludes to changed dynamics that arise if first guard is answered with first guard.</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|5|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02r.jpg|5|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

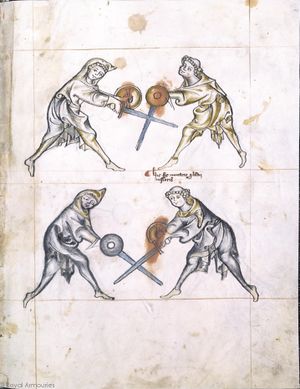

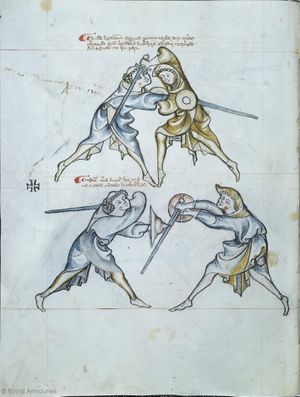

| − | | rowspan="6" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="6" | [[File:MS I.33 02v.jpg|300px|center]] |

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[12] Note that the scholar here binds and applies pressure so that he gets to perform a ''schiltslac'' as [in the image] below. But he should take care that what is to be done on the |

| + | part of the priest [because] after the bind, the priest will be the first to act. Note also that the priest can do nothing other than a ''schiltslac'' or embracing with the left hand the arms of the priest, i.e. sword and shield.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|1|lbl=2v}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|1|lbl=2v}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[13] It is to be seen, that the pupil has no option but to do a ''schiltslac'', or to grip the arms of the priest with his left hand, namely sword and shield.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[14] Verse:<br/>{{red|Here the scholar binds and presses, for him is a ''schildschlac''.<br/>Or with the left hand he is to embrace the priest's arms.}}</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[15] The priest here has three options, viz. sword-change, so that he is above, or ''durchtreten'', or with the {{dec|s|left}}<sup>right</sup> hand embrace the arms of the scholar, i.e. sword and shield.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[16] {{red|These three are for the cleric: ''durchtrit'', sword-change,<br/>or with the right hand he could take the sword [and] shield.}}<ref>This is written vertically on the right margin. The image is damaged, but it is the first of dozen identical images illustrating “overbind” (see §11). This image is also the first instance of a “change of perspective” (i.e. the position of fencers is inverted; this is done on purpose in order to show the hand position of the fencer).</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|5|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|5|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[17] Note that what is said above you find in this example.<ref>i.e. Showing the ''schiltslac''.</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|6|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 02v.jpg|6|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

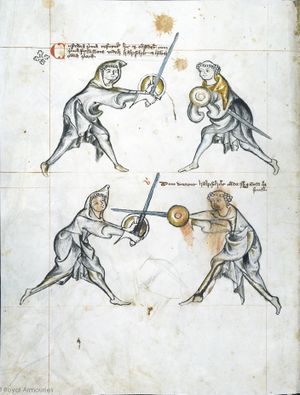

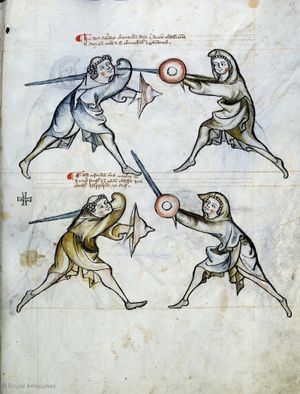

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 03r.jpg|300px|center]] |

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[18] '''(+)''' Note that the first guard is resumed here, due to certain actions from the first section, i.e. of the first guard of which was treated before, but all that belongs here you find in the first page, up to the sword-change.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 03r.jpg|1|lbl=3r}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 03r.jpg|1|lbl=3r}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[19] {{red|When ''halbschilt'' is assumed, fall<br/>under sword and shield.}}<ref>The verse is written between the two images on the left side (the side of the fencer performing the technique).</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 03r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 03r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="4" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="4" | [[File:MS I.33 03v.jpg|300px|center]] |

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[20] Here is a bind on the part of the scholar, and all other things which were treated above, until the sword-change below.<ref>The first three images of the second play are equivalent to the first play. This is made explicit in the text, the sword-change in the following image being shown as a counter to the overbind. But note the explicit depiction of step with the left foot forward for the overbind (based on the position of the rear foot), a detail absent from the equivalent situation as shown in 2v.</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 03v.jpg|1|lbl=3v}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 03v.jpg|1|lbl=3v}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[21] Here the scholar gets good counsel as to how he may resist this. And know that when the game is as shown here, then a ''stich'' must be executed as generally contained in the book, even though there are no images of this [here].</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 03v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 03v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[22] Note how the priest here changes the sword, because it was below and now it will be above; then he puts the sword to his adversary's head, which is called ''nucken'', from which results a separation of the sword and the shield of the scholar.<ref>The two paragraphs are arranged on the left and on the right, referring to the scholar and the priest, respectively. The image shows the situation after the sword-change (''mutatio gladii''); the scholar is instructed to counter this with a ''stich'', but this isn't pursued further. This is presumably the action depicted in 10r, where it is, however, referred to as ''stichslac''. The play here instead continues with the action of ''nucken'' performed by the priest immediately after the sword-change. The last part of the second paragraph is already in reference to the following image on the next page, i.e. the one depicting the priest's ''nucken''. |

| + | |||

| + | The word is written ''nucken'' in prose, but then ''nukcen'' in the verse: is this a simple error, or is the creation of an apparent rhyme with ''schutzen'' significant?</ref></p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 03v.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 03v.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[23] Hence the verse:<br/>{{red|So the cleric's ''nucken'',<br/>[where] the common fencers [will rather?] ''schutzen''.}}</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 03v.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 03v.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

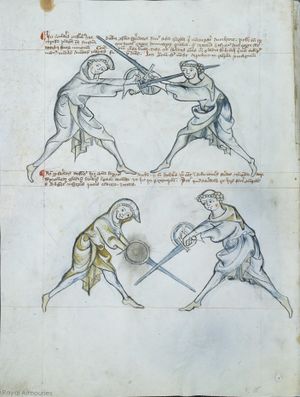

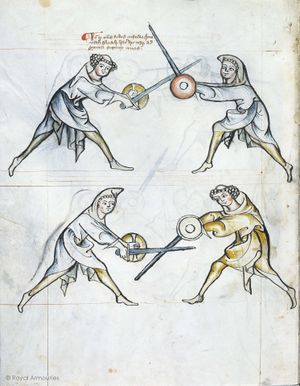

| − | | rowspan="3" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="3" | [[File:MS I.33 04r.jpg|300px|center]] |

| − | | <p>[ | + | | <p>[24] Here the priest should take care not to delay with the sword in the slightest, lest out of this delay an action should arise which is called wrestling, but out of caution he must immediately re-establish the bind.<ref>The paragraph is centered on the page above the image, perhaps added as an afterthought as the scribe realised that the description intended for this image has already been given on the previous page. This image is unique in the book, and CS point out correctly a mistake on the part of the illustrator, who has given the priest two left hands.</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 04r.jpg|1|lbl=4r}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 04r.jpg|1|lbl=4r}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[24] '''(+)''' {{red|H}}ere the first | + | | <p>[24] '''(+)''' {{red|H}}ere the first guard is resumed, the siege to which guard will be very rare, because nobody is in the habit of performing it except for the priest, or his little clients, i.e. students, and this siege is called ''krucke'', and I counsel in good faith that he who assumes the guard should bind immediately after the siege, as it isn't good to lag, or to do any of the things by which he might be saved, or that he at least execute the same as the [besieger] did.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 04r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 04r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[25] | + | | <p>[25] Know that the besieger must not hesitate but immediately after the siege should execute a ''stich''; thus the adversary cannot deliberate on what he might intend and this is to be understood diligently.<ref>The second paragraph is written on the right margin. The ''krucke'' is introduced as an alternative reaction to first guard (other than ''halbschilt''), and advertised as a speciality of the priest's system. This position at the same time covers the right side (threatened by first guard) and threatens a thrust to the opponent's sword side. CS interpret the image as reflecting the fencers maintaining eye contact under the shield. I do not think this is the case: ''Krucke'' should be performed with a step to the right, and eye-contact is maintained in a line passing left of the shield.</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 04r.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 04r.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="4" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="4" | [[File:MS I.33 04v.jpg|300px|center]] |

| − | | <p>[26] Here the priest binds above the | + | | <p>[26] Here the priest binds above the scholar's siege, and immediately there follow all the preceding things, which you had before, although granted, two images you did not yet see, they follow below, where he catches sword and shield.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 04v.jpg|1|lbl=4v}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 04v.jpg|1|lbl=4v}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[27] Note that whenever binder and bound are | + | | <p>[27] Note that whenever binder and bound are in conflict as here, then the bound can flee wherever he wants, if he so chooses, and it is necessary in all binds. But for this you have to be prepared, that wheresoever the bound [flees], you should pursue him.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 04v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 04v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[28] {{red|Binder and bound | + | | <p>[28] {{red|Binder and bound are contrary and irate;<br/>The bound flees to the side, I aim to pursue.}}<ref>The first occurrence of the ''ligans-ligati'' verse, written on the left margin; note that the verse is grammatically dubious, you would expect ''ligans ligatusque'' or something similar. The text is distracted from the play at hand to give general advice on the bind, but 5v below can be seen as immediately following the establishment of the bind here.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 04v.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 04v.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[29] Here the priest teaches his | + | | <p>[29] Here the priest teaches his student how from the above he may catch sword and shield, and know that the priest cannot free himself from such an embrace without letting go of his sword and shield.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 04v.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 04v.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 05r.jpg|300px|center]] |

| − | | <p>[30] Here the priest defends against what the | + | | <p>[30] Here the priest defends against what the scholar does above.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 05r.jpg|1|lbl=5r}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 05r.jpg|1|lbl=5r}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[31] '''(+)''' Here | + | | <p>[31] '''(+)''' Here first guard is resumed, but all that is required here you have likewise [i.e. as discussed above], with the sole exception of the scholar's omission of the bind.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 05r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 05r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 05v.jpg|300px|center|Folio 5v]] |

| − | | <p>[32] Here the | + | | <p>[32] Here the scholar has omitted [all actions], as he did not bind; the scholar enters straight [away],<ref>''prossus'' for ''prorsus'' or ''prosus'' “straight ahead, directly, truly”; even though the literal meaning of the adverb is “straight ahead”, the intended meaning is not necessarily spatial but rather temporal, i.e. the priest enters “straight away” as the scholar omits the bind, but not necessarily in a straight line.</ref> and not without merit, because whenever the one assuming the guard omits that which he has to do, the besieger has to enter as [shown] here.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 05v.jpg|1|lbl=5v}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 05v.jpg|1|lbl=5v}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>[33] '''(+)''' | + | | <p>[33] '''(+)''' The siege is as before, but the play is different.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 05v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 05v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 06r.jpg|300px|center|Folio 6r]] |

| <p>[34] Above, the priest displaced the pupil. Here now, the pupil is executing the same action as the priest before. But the displacer should enter first, if the pupil omits it, as below. Also, he should take care that the other reach not his head, which he may.</p> | | <p>[34] Above, the priest displaced the pupil. Here now, the pupil is executing the same action as the priest before. But the displacer should enter first, if the pupil omits it, as below. Also, he should take care that the other reach not his head, which he may.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 06r.jpg|1|lbl=6r}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 06r.jpg|1|lbl=6r}} | ||

| Line 254: | Line 270: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 06v.jpg|300px|center|Folio 6v]] |

| <p>[36] '''(+)''' Here the first ward is re-assumed, namely the one under the arm, which is displaced with a certain counter that is called ''langort'', and it is a common displacement, and the counters to this displacement are, for the part of the one assuming the ward, bindings above and below,</p> | | <p>[36] '''(+)''' Here the first ward is re-assumed, namely the one under the arm, which is displaced with a certain counter that is called ''langort'', and it is a common displacement, and the counters to this displacement are, for the part of the one assuming the ward, bindings above and below,</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 06v.jpg|1|lbl=6v}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 06v.jpg|1|lbl=6v}} | ||

| Line 265: | Line 281: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 07r.jpg|300px|center|Folio 7r]] |

| <p>[38] Here the game of the former ward will take place, namely of binder and bound,</p> | | <p>[38] Here the game of the former ward will take place, namely of binder and bound,</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 07r.jpg|1|lbl=7r}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 07r.jpg|1|lbl=7r}} | ||

| Line 276: | Line 292: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 07v.jpg|300px|center|Folio 7v]] |

| <p>[41] '''(+)''' First ward and common displacement as above, but the game varies at the end of the passage.</p> | | <p>[41] '''(+)''' First ward and common displacement as above, but the game varies at the end of the passage.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 07v.jpg|1|lbl=7v}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 07v.jpg|1|lbl=7v}} | ||

| Line 288: | Line 304: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | [[File:MS I.33 08r.jpg|300px|center|Folio 8r]] |

| <p>[43] Here a mutation of the sword below is taking place.</p> | | <p>[43] Here a mutation of the sword below is taking place.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 08r.jpg|1|lbl=8r}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 08r.jpg|1|lbl=8r}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 08v.jpg|300px|center|Folio 8v]] |

| <p>[44] '''(+)''' The first ward is re-assumed and displaced by the first displacement, namely ''halpschilt'', and you will have all of the above.</p> | | <p>[44] '''(+)''' The first ward is re-assumed and displaced by the first displacement, namely ''halpschilt'', and you will have all of the above.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 08v.jpg|1|lbl=8v}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 08v.jpg|1|lbl=8v}} | ||

| Line 307: | Line 323: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 09r.jpg|300px|center|Folio 9r]] |

| <p>[46] '''(+)''' It can be seen how here is taught in which way the second ward may be displaced. And I say the second ward, because the third ward which is given to the left shoulder, does not differ much from the second. But here we speak of the second ward, which is given to the right shoulder. And from the same ward, the displacer executes the displacement called ''schutzen'', because every ward has its protection (which is the meaning of ''schutzen'').</p> | | <p>[46] '''(+)''' It can be seen how here is taught in which way the second ward may be displaced. And I say the second ward, because the third ward which is given to the left shoulder, does not differ much from the second. But here we speak of the second ward, which is given to the right shoulder. And from the same ward, the displacer executes the displacement called ''schutzen'', because every ward has its protection (which is the meaning of ''schutzen'').</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 09r.jpg|1|lbl=9r}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 09r.jpg|1|lbl=9r}} | ||

| Line 316: | Line 332: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS I.33 09v.jpg|300px|center|Folio 9v]] |

| <p>[48] Here the pupil, instructed by the priest, executes an action that is called ''durchtritt''.<ref>''durchtritt'': a step to the side seems intended; for the (preferable) action depicted, we would expect 'to the left', so dexteram may be taking the opponent's view.</ref> He might get an opportunity far a strike to the left, as it is done by general fencers, or to the right, as it is done by the priest and his youths. To counter these two possibilities, the priest may, with the sword under the arm, reach the bare hands of him who executes the abovementioned strikes, although this counter is not depicted in the example image.</p> | | <p>[48] Here the pupil, instructed by the priest, executes an action that is called ''durchtritt''.<ref>''durchtritt'': a step to the side seems intended; for the (preferable) action depicted, we would expect 'to the left', so dexteram may be taking the opponent's view.</ref> He might get an opportunity far a strike to the left, as it is done by general fencers, or to the right, as it is done by the priest and his youths. To counter these two possibilities, the priest may, with the sword under the arm, reach the bare hands of him who executes the abovementioned strikes, although this counter is not depicted in the example image.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS I.33 09v.jpg|1|lbl=9v}} | | {{section|Page:MS I.33 09v.jpg|1|lbl=9v}} | ||

Revision as of 02:16, 28 November 2017

| Walpurgis Fechtbuch | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS I.33, Royal Armouries Leeds, United Kingdom | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Also known as |

| ||||

| Type | Fencing manual | ||||

| Date | ca. 1320s | ||||

| Place of origin | Franconia | ||||

| Language(s) | Medieval Latin | ||||

| Ascribed to | Clerus Lutegerus | ||||

| Scribe(s) | Unknown (three hands) | ||||

| Illustrator(s) | Unknown (up to 17 artists) | ||||

| Material | Parchment, in a modern binding | ||||

| Size | 34 folia | ||||

| Format | Double-sided; two illustrations per side with text above and below | ||||

| Script | Bastarda | ||||

| Previously kept | MS Membr.I 115, Schloß Friedenstein | ||||

| Treatise scans |

Digital scans (600x800)

| ||||

| Other translations | |||||

The MS I.33 is a German fencing manual dating to the 1320s.[1] It currently rests in the holdings of the Royal Armouries at Leeds, United Kingdom. The I.33 is earliest extant treatise on Medieval martial arts, and it appears to have been devised by a secular priest, possibly the "Lutegerus" (or Liutger) mentioned in the text.[2] It was the work of three scribes and potentially as many as 17 illustrators.[3]

The treatise is fully illustrated, and consists of both mnemonic verses and longer explanations in a vernacular Medieval Latin. (The format of verse and gloss may indicate that the priest was explaining a much older tradition.) It treats unarmored fencing with sword and buckler; the intriguing fact that the fencers depicted are a priest and a student (and on the last two pages, a priest and a woman identified as St. Walpurga), seems to suggest that this was a middle class or priestly art rather than one of the knightly class. Repeatedly, the text makes mention of the pupils (scolaris/discipulus) of the priest, as well as youths (iuvenis) and clients (clientulum). It seems, therefore, to have been prepared for secular priests who were offering fencing lessons to young men.

The manuscript in its present form consists of five quires, of which all but the first are incomplete; at least eight leaves are believed to be missing (assuming it started with complete quires of four bifolia each).[3] The precise contents of these missing leaves are unknown, but it is possible that they were a source for the thirty uncaptioned sword and buckler plays which appear in the Libri Picture A 83, the Codex I.6.2º.4, and the Cgm 3712; alternatively, these may originate from another manuscript in the same tradition. The anonymous plays seem in turn to have been the primary source for Paulus Hector Mair's treatment of the side sword and buckler, which he captioned with his own interpretations.

Contents

Provenance

The known provenance of the MS I.33 is:

- Written in the 1320s, possibly by a priest named Liutger; owned by Franconian monks until the 1500s.

- 1400s – an additional couplet was inscribed at the top of folio 1r.

- 1552-53 – looted from a monastery by Johannes Herbart von Würzburg during the Franconian campaigns of Albert-Archibald, Duke of Brandenburg-Kulmbach.[4][3] Würzburg was a belt-maker by trade and later served as fencing master to the dukes of Sachsen-Gotha; he inscribed his name on folio 7r.

- before 1579 – possibly duplicated by Heinrich von Gunterrodt while compiling material for his book[4] (such a copy is currently unknown).

- late 1500s-1945 – owned by the dukes of Sachsen-Gotha; listed in an 18th century library catalog as Cod.Membr.I.no.115.[citation needed] The second device on folio 26r was copied into the Codex Guelf 125.16 Extravagante in the 1600s by a scribe who couldn't decipher the Latin text.[5] The manuscript was further described on six leaves of paper (with short excerpts of the text) by Heinrich Niewöhner in 1910. (Lost during World War II.)

- 1945-1950 – location unknown (sold London, Sotheby's, 27 March 1950). Sotheby's listed the manuscript as "a 14th-century manuscript of unknown provenance", and it was not identified as the lost Cod.Membr.I.no.115. until Krämer in 1975.[6]

- 1950-1996 – held by the Royal Armouries and stored in the Tower of London; known variously as "Tower of London Ms. I.33" or "British Museum No. 14 E iii, No. 20, D. vi. I".

- 1996 – moved to the newly-opened Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds.

Contents

| 1r - 32v |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Gallery

Identification and placement of missing leaves based on work by Dr. Jeffrey L. Forgeng[citation needed] and James Hester.[3] These scans are licensed under the terms of the Royal Armouries Non-Commercial Image Licence.

Additional Resources

- Binard, Fanny and Jaquet, Daniel. "Investigation on the collation of the first Fight book (Leeds, Royal Armouries, Ms I.33)". Acta Periodica Duellatorum 4(1): 3-21. 2016. doi:10.1515/apd-2016-0001.

- Cinato, Franck and Surprenant, André (in French). Le Livre de l'art du Combat: Liber de arte dimicatoria. Édition critique du Royal Armouries MS. I.33, collection Sources d'Histoire Médiévale nº39. Paris: CNRS Editions, 2009. ISBN 978-2-271-06757-9

- Dawson, Timothy. "The Walpurgis Fechtbuch: An Inheritance of Constantinople?" Arms & Armour 6(1):79-92. April 2009. doi:10.1179/174962609X417536

- Forgeng, Jeffrey L. The Illuminated Fightbook Royal Armouries Manuscript I.33. Extraordinary Editions, 2012.

- Forgeng, Jeffrey L. The Medieval Art of Swordsmanship: A Facsimile & Translation of Europe's Oldest Personal Combat Treatise, Royal Armouries MS I.33 (Royal Armouries Monograph). Chivalry Bookshelf, 2003. ISBN 1-891448-38-2

- Hester, James. "A Few Leaves Short of a Quire: Is the ‘Tower Fechtbuch’ Incomplete?" Arms & Armour 9(1):20-25. April 2012. doi:10.1179/1741612411Z.0000000003

- Hester, James. "Home-Grown Fighting: A Response to the Argument for a Byzantine Influence on MS I.33". Arms & Armour 9(1):76-84. April 2012. doi:10.1179/1741612411Z.0000000008

- Kellett, Rachel E. "Royal Armouries MS I.33: The Judicial Combat and the Art of Fencing in Thirteenth- and Fourteenth- Century German Literature". Oxford German Studies 41(1):32-56. April 1012. doi:10.1179/0078719112Z.0000000003

- Morini, Andrea and Rudilosso, Riccardo (in Italian). Manoscritto I.33. Rome: Il Cerchio Iniziative Editoriali, 2012.

References

- ↑ The manuscript has received a wide variety of dates. Anglo (1988) dated it to "the very end of the 13th century" and Hils (1985) to the early 14th century; Cinato and Surprenant (2009) are even less precise, placing it at around the turn of the 14th century. Most recent analysis has suggested a slightly later date, with Leng (2008) dating it to 1320-1330 and Hester (2012) to "around 1320".

- ↑ See folio 1v.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Hester (2012).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 von Gunterrodt, Heinrich. De Veris Principiis Artis Dimicatorie. Wittenberg, 1579. p C3rv

- ↑ See Codex Guelf 125.16.Extrav., f 45r.

- ↑ S. Krämer. "Verbleib unbekannt Angeblich verschollene und wiederaufgetauchte Handschriften." Zeitschrift für Deutsches Altertum und Deutsche Literatur, volume 104. 1975

- ↑ The introductory verse is added on the top margin of the page in a 15th-century hand. The distichon was apparently added in the 15th century, when the manuscript was still kept in a monastery library. It seems to express a disparaging view of “armed clerics” and clearly also refers to the depiction of a female fencer on the last folium. This verse is attested in print in the 16th century, and there attributed to Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (Pope Pius II, 1405–64), as follows:

- Andreas Gärtner, Proverbialia dicteria (1574): “Non audet Stygius Pluto tentare, quod audet Eff renis monachus plenaque fraudis anus” (cited after Wilhelm Binder, Novus Thesaurus Adagiorum Latinorum, 1861 who off ers the German paraphrase “Wo der Teufel nicht selbst hin will, schickt er entweder einen Pfaff en, oder ein altes Weib.”)

- Holinshed's Chronicles (1577): “Æneas Sylvius (and before him many more driving upon the like argument) dooth saie in this distichon: Non audet Stygius Pluto tentare, quod audent / Eff rænis monachus, plenaque fraudis illa. Meaning Mulier, a woman.”

- ↑ Gunterrodt: Tres quae praecedunt, reliquae tantum fugientes.

- ↑ It is suggestive that the author (if we accept the instructor in the verses and in the manual as the same person) is called cler[ic]us “the cleric” (or “the clerk”) three times in these verses, but never in the text; conversely, the text consistently calls him sacerdos, and never clericus (Middle Latin use of clerus for clericus is noted in Du Cange's Glossarium). It is almost as if he had composed the verses as a mnenomic orally at an earlier time, before envisaging the project of creating this manual, when he was younger and not yet ordained as a priest. Latin clericus renders MHG pfaffe, which may could to either a priest, a deacon or a member of the minor orders. Note that it is not unusual to find the designation pfaffe associated with fencing masters of the late medieval tradition, so Hanko Döbringer (still in the 14th century) and Hans Lecküchner (in the later 15th century). The interpretation of the name Lutegerus in the verse on fol. 1v depends on the interpretation of the verse of which it forms a part. This verse is very difficult to interpret in a number of ways. In fact, nothing about it is entirely clear to me.

- ↑ Are we to understand that the seven guards are the same as the “seven parts”, and of these three “precede” (or “go forward” as antonym to fugiunt?) and the remaining (i.e. four) “flee” or “go backward” in some way? CS translate Il y en a trois qui avancent, tandis que les autres replient. But “reply” isn't really what a custodia does, the system has the separate term obsessio just for that, and there is nothing in the subsequent material that would somehow suggest that some of the guards have a function of replying or reacting to the others. It is also anyone's guess how the guards are to be grouped. One reasonable assumption would be the the first four, shown on 1r, as opposed to the final three, shown on 1v. There is, in fact, a conceptual difference between the groups, guards 1-4 as described in the manual initiate a strike, while 5 and 6 initiate a thrust, and 7 is a special case, inviting a bind instead of posing a direct threat. Now, the verse goes on to say “these seven (parts, guards) are done by the common fencers”, followed by “the cleric holds the opposite, and Luitger holds the middle”. This may be interpreted in a number of ways. It is important to note that neither medium nor oppositum is used in any technical sense anywhere in the manual outside of this verse. CS have Le clerc est a l'opposé et Luitger à mi-chemin “the cleric is opposite, and Luitger is at halfway”, i.e. they here treat “the cleric” as a different person from Luitger. In the reading of Ukert, Lutegerus is a reference by name to a notable “common fencer”, so that the cleric holding “the opposite” would presumably be preferable to the “common fencer” Luitger who holds merely “the middle”. It does seem more probable to me, however, that the entire line refers to a single person, clerus Lutegerus, who holds “both the opposite and the middle” and that this statement, as a whole, contrasts with the “common fencers” mentioned in the preceding line. Note that this would mean that the author here employs hyperbaton (the separation of the two associated nominatives), in apparent aspiration to a “poetic” mode of speech entirely absent from the rest of the “verses”. I am unsure whether the terms oppositum and medium should be interpreted in a figurative way, as it were “he is in possession of the counter and the means”, or in a strictly spatial sense, as it were “he holds against (his opponent)” and at the same time “he holds or occupies the center” between the fencers. This latter interpretation strikes me as a useful description of the “conflict of binder and bound” referenced throughout the manual, but it must be admitted that a discussion in the terms used in the verse is not repeated anywhere in the following text. It nevertheless remains my preferred reading, against both CS and Ukert, that “clerus Lutegerus” here refers to a single person, and most likely the manual's author himself (compare the discussion of de Alkersleiben below).

- ↑ Gunterrodt (1579) read this name as Albenslaiben recognising it as the name of the “ancient stem and most famous family” (vetustissima prosapia et clarissima familia) of Alvensleben. Ukert, on the other hand, reads Alkersleiben. Both Gunterrodt and Ukert recognised the word as a personal name (while a reading albersleiben is due to Forgeng, who identified the word as a fencing term, a “proto-Liechtenauerian” version of Alber). Alkersleiben is clearly more consistent with the manuscript, and Gunterrodt's reading should perhaps be considered an emendation, inserting the more familiar name of Alvensleben, a prominent noble family of Brandenburg in Gunterrodt's time (which also had held extensive possessions already in the 1300s). For Gunterrodt, it was obvious that the author of the manuscript must have been a nobleman who had retired to a monastery in his old age, and he took his reading as a confirmation of the association with nobility without positively identifying the name as referencing the manual's author. However, reading de Alkersleiben (with Ukert) we have a reference to the Thuringian village of Alkersleben (recorded in the 13th century as Alkesleibin), at the time of merely local importance as the site of a manor and a deanery. Alkersleben is some 200 km to the north of the parts of Franconia affected by the Second Margravian War, the presumed area of production of our manuscript. Ukert interprets both Lutegerus and de Alkersleiben as the names of “common fencers” (generales dimicatores, “gemeine Fechtmeister”). This depends entirely on the context we give to the occurrence of the names, in the case of de Alkersleiben: Non ducat aliquam plagam quod probat de Alkersleiben “He should not deliver any strike, as recommended by de Alkersleiben” – are we to understand that this is a counsel against the recommendation to “deliver a strike” attributed to a notable “common fencer” known as de Alkersleiben, or are we much rather to understand that the counsel not to deliver a strike is attributed to the highly profi cient fencer known by this name, which would amount to nothing less than yet another reference by the author to himself in the third person? If we are ready to interpret Lutegerus in this way, I see no obstacle to adopt the same position here, which would give us an author Clericus Lutegerus de Alkersleiben, or, in German, Pfaffe Luitger von Alkersleben. Incidentially, the term nucken happens to be more consistent with a Thuringian rather than a Franconian origin of whoever is responsible for coining it.

- ↑ CS praise this image as “one of the most beautiful aesthetic successes” of the codex. The postures are drawn very carefully, including an indication that each fencer has the right foot forward, a detail that will not be evident in later figures. The final (and let's face it, rather awkward) paragraph is in hand B and alludes to changed dynamics that arise if first guard is answered with first guard.

- ↑ This is written vertically on the right margin. The image is damaged, but it is the first of dozen identical images illustrating “overbind” (see §11). This image is also the first instance of a “change of perspective” (i.e. the position of fencers is inverted; this is done on purpose in order to show the hand position of the fencer).

- ↑ i.e. Showing the schiltslac.

- ↑ The verse is written between the two images on the left side (the side of the fencer performing the technique).

- ↑ The first three images of the second play are equivalent to the first play. This is made explicit in the text, the sword-change in the following image being shown as a counter to the overbind. But note the explicit depiction of step with the left foot forward for the overbind (based on the position of the rear foot), a detail absent from the equivalent situation as shown in 2v.

- ↑ The two paragraphs are arranged on the left and on the right, referring to the scholar and the priest, respectively. The image shows the situation after the sword-change (mutatio gladii); the scholar is instructed to counter this with a stich, but this isn't pursued further. This is presumably the action depicted in 10r, where it is, however, referred to as stichslac. The play here instead continues with the action of nucken performed by the priest immediately after the sword-change. The last part of the second paragraph is already in reference to the following image on the next page, i.e. the one depicting the priest's nucken. The word is written nucken in prose, but then nukcen in the verse: is this a simple error, or is the creation of an apparent rhyme with schutzen significant?

- ↑ The paragraph is centered on the page above the image, perhaps added as an afterthought as the scribe realised that the description intended for this image has already been given on the previous page. This image is unique in the book, and CS point out correctly a mistake on the part of the illustrator, who has given the priest two left hands.

- ↑ The second paragraph is written on the right margin. The krucke is introduced as an alternative reaction to first guard (other than halbschilt), and advertised as a speciality of the priest's system. This position at the same time covers the right side (threatened by first guard) and threatens a thrust to the opponent's sword side. CS interpret the image as reflecting the fencers maintaining eye contact under the shield. I do not think this is the case: Krucke should be performed with a step to the right, and eye-contact is maintained in a line passing left of the shield.

- ↑ The text has been re-traced in darker ink, according to CS by hand C (but closely following the original ductus of hand A).

- ↑ recipere plagam: to execute (not to receive) a blow. Probably intended as 'receive the opportunity to strike'.

- ↑ durchtritt: a step to the side seems intended; for the (preferable) action depicted, we would expect 'to the left', so dexteram may be taking the opponent's view.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 dampnum for damnum

- ↑ vidilpoge = "fiddle-bow".

- ↑ fingitur for figitur; fuit vicium pictoris: Here is evidence that the author is not identical with the draftsman.

- ↑ Concerning the name of the woman fencer: The name walprgis as written directly above the word sac'dos (below which are five dots forming a line). It is not entirely clear, whether Walpurgis is meant to replace sacerdos or if it is an addition (in which case it would be genitive of Walpurga). But since in the picture, the woman is executing the schiltslac, and because the woman is said to have been ready first (parata), she must be called (in the nominative) Walpurgis.

Copyright and License Summary

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Images | Royal Armouries | Used under the Royal Armouries Non-Commercial Image Licence | |

| Translation | Dieter Bachmann | Kunst des Fechtens | |

| Transcription | Dieter Bachmann | Index:Walpurgis Fechtbuch (MS I.33) |