Images

|

Complete Translation

by Dieter Bachmann

|

Transcription [edit]

by Dieter Bachmann

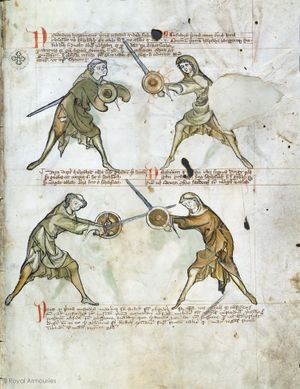

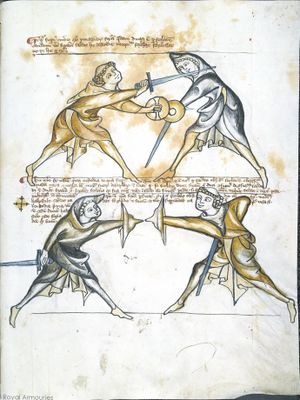

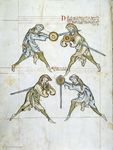

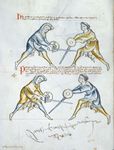

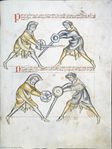

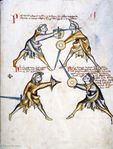

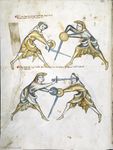

|

|

|

[1] Stygian Pluto dares not attempt what a rogue monk

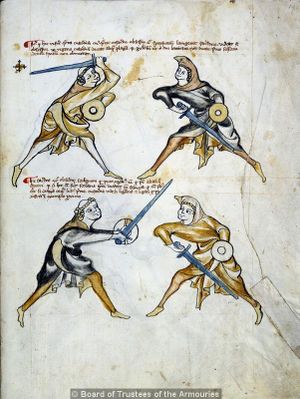

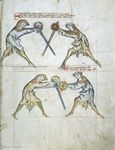

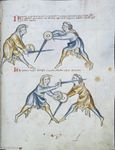

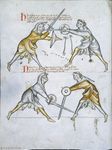

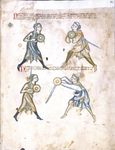

and a treacherous hag dare do.[7]

|

[1r] Non audet stygius pluto tentare, quod aude[t]

Effrenis monachus plenaque dolis anus

|

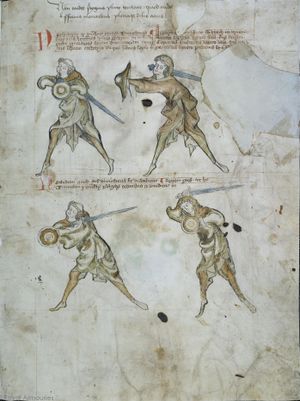

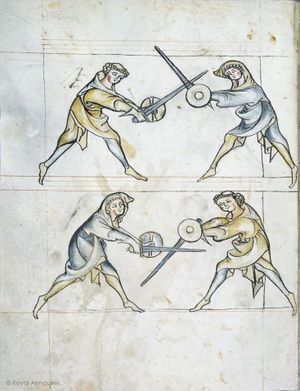

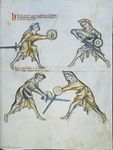

[2] It is to be noted, how in general all fencers, or all men holding a sword in hand, even if ignorant in the art of fencing, use these seven wards, of which we have seven verses:

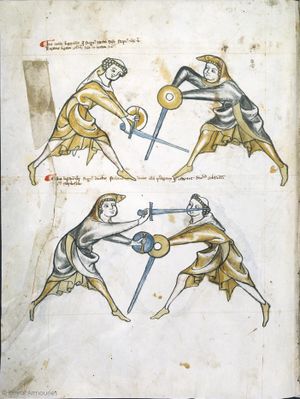

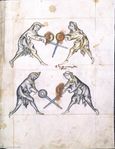

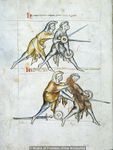

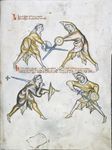

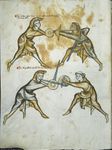

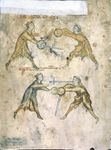

|

NOtandum est quod generaliter omnes Dimicatores, sive omnes homines habentes gladium in manibus, etiam ignorantes artem dimicatoriam vtuntur hijs septem custodijs de quo habemus septem versus

|

[3] Seven wards there are, under the arm the foremost,

to the right shoulder is given the second, to the left the third,

to the head give the fourth, give to the right side the fifth,

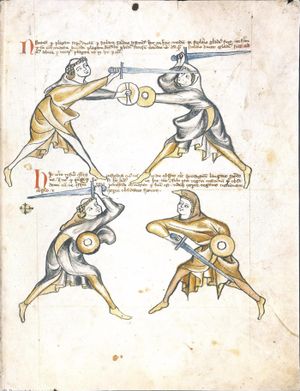

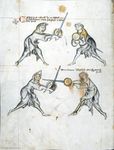

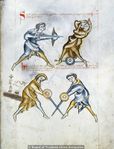

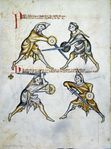

to the breast give the sixth, and finally have you the langort.

|

¶ Septem [cust]odie sunt sub brach incipiende

Humero dextrali datur alter terna sinistro

Capiti da quartam da dextro latere quintam

Pectori da sextam, postrema sit tibi l[angort]

|

[4] It is to be noted, that the art of fencing is so described: Fencing is the the ordering of diverse strikes, and is divided in seven parts, as here.

|

NOtandum quod ars dimicatoria sic describitur Dimicatio est diversarum plagarum ordinatio & diuiditur in ¶ septem partes vt hic

|

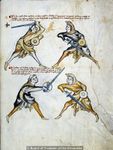

|

|

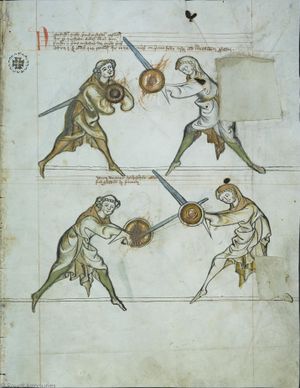

[5] Note, that the nucleus of all the art of fencing consists in this latter ward which is called langort. Also, all actions of the wards or of the sword are determined by it, i.e. they end in it and not in others. Therefore, do first consider well this above-mentioned ward.

|

[1v] NOta quod tot nucleus artis dimicatorie consistit in illa vltima custodia que nuncupatur langort pretera omnes actus custodiarum siue gladij determinantur in ea i. finem habent & non in alijs Vnde magis considera eam supradi[c]ta prima

|

[6] It is three that precede, the remaining do follow

These seven parts are (also) executed by the common,

(but) Brother Liutger[8] has the defense and the means.

|

Tres sunt que preeunt relique tunc fugiunt

Hec septem partes ducuntur per generales

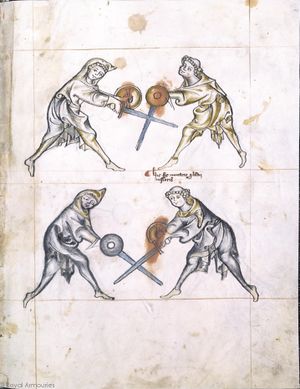

Oppositum clerus mediumque tenet lutegerus

|

|

|

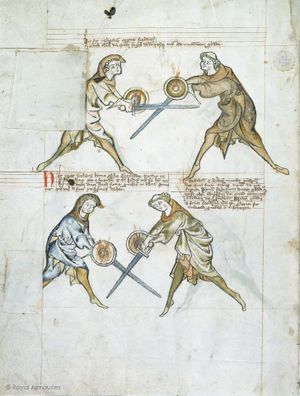

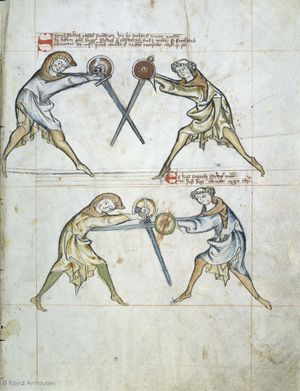

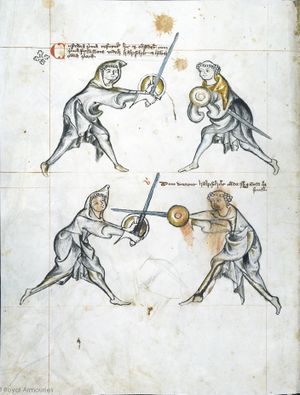

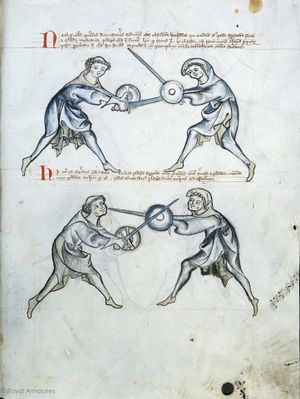

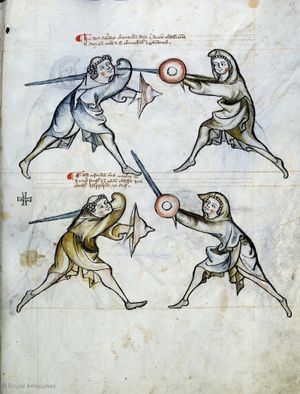

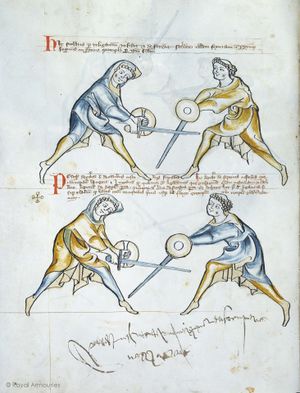

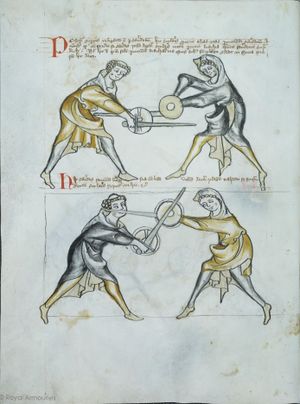

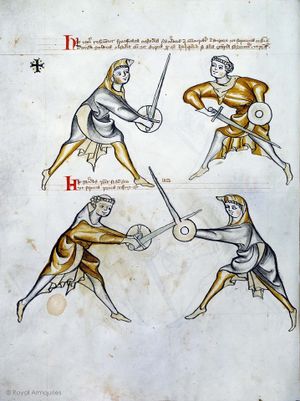

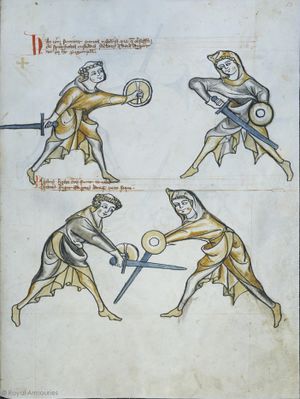

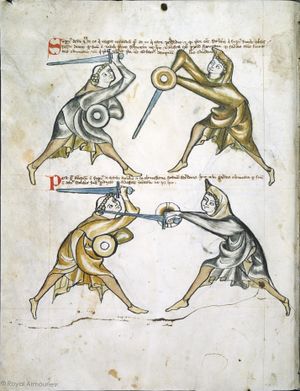

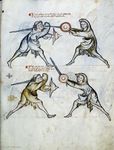

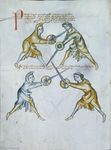

[7] (+) It is to be seen that here is the first ward contained, i.e. the one under the arm, and the displacer is in halpschilt. I give the good counsel that the one (assuming the ward) under the arm do not execute a strike, which is commendable from the albersleiben, for the reason that he could not reach the upper part, and (reaching anywhere) lower would be pernicious to the head. But the displacer entering to attack may reach him at any time if he fails to observe what is written below:

|

[2r] 🕀 NOtandum hic continetur prima custodia, videlicet sub [brachio] obsesseo vero halbschilt ¶ Et consulo sano consilio quod il[...] sub brachio non ducat aliquam plagam quod probat de al[b]ersleiben, per raciones quia partem superiorem attingere non potest si inferiorem capiti erit perniciosum sed obsessor intrando potest eum invadere quandocumque si obmittit quod tenetur vt infra scriptum est

|

[8] Verse:

The first ward / Has two counters,

The first counter being halbschilt, / The second Langort.

If Halbschild is adopted, fall / Below both sword and shield.

If he is a common fencer, he will strike to the head, / Then you should apply stichschlach,

If he binds and enters, / Then you should counter with schiltschlac.

|

Versus:

¶ Custodia prima retinet contraria bina

Contrarium primum halpschil langortque secundum

¶ Dum ducitur halpschilt cade sub gladium quoque scutum

Si generalis erit recipit caput sit tibi stichschlach

Si religat calcat contraria si(n)t tibi schiltschlac

|

[9] It is to be seen that the one who is higher is directing a strike to the head, without schiltslac, if he is a common fencer. But if you would be instructed by the priest's counsel, do bind and enter.

|

NOtandum quod qui iacet superius dirigit plagam post [c]apud sine schiltslach si est generalis Si autem uis edoceri consilio sacerdotis tunc religa et calca

|

[10] Note that the first ward, i.e. the one under the arm, may be displaced by itself, namely, the displacer may displace the one assuming the first ward with that selfsame ward. Nevertheless, the one assuming first ward can displace the displacer with a displacement that in a way corresponds to the displacement called halpschilt, but differs from it in this, that the sword below the arm is extended above the shield, so that the hand holding the shield is enclosed by the hand holding the sword.

|

NOta quod prima custodia videlicet sub brachium potest obsederi se ipsa ita videlicet quod obsidens cum eadem custodia potest regentem primam custodiam obsidere nichilominus tamen regens custodiam primam econtrario possessorem obsidere potest obsessione quadam que quodammodo concordat cum possessione que vocatur halpshilt differt tamen in eo quod gladius sub brachio* extenditur supra scutum taliter quod manus regens scutum includitur in manu regente gladium

|

|

|

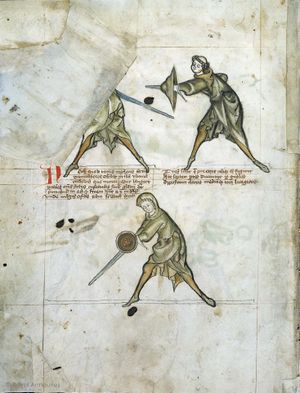

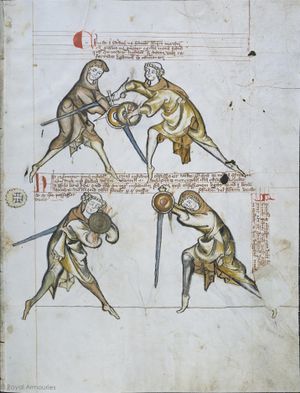

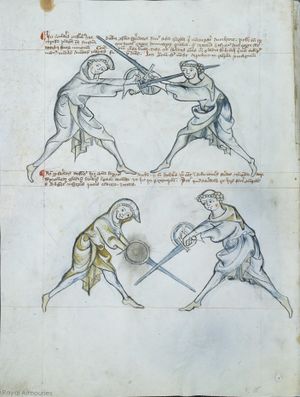

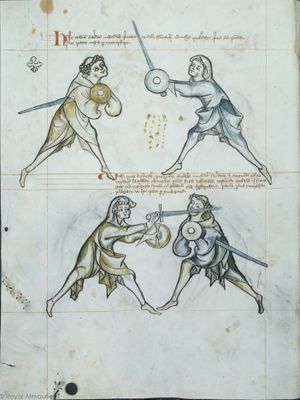

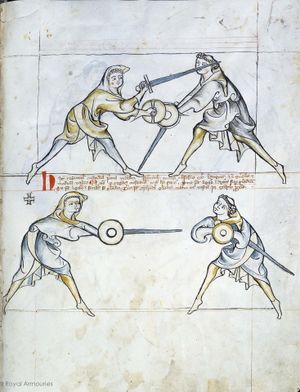

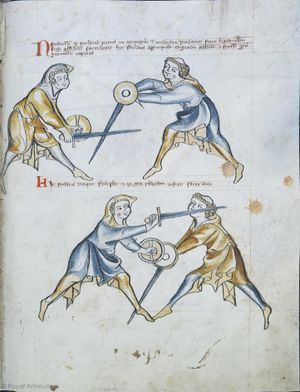

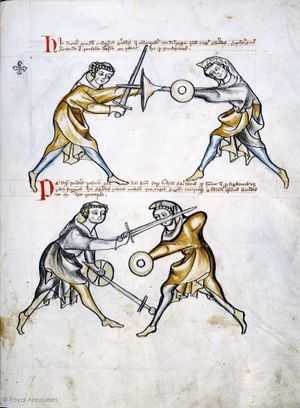

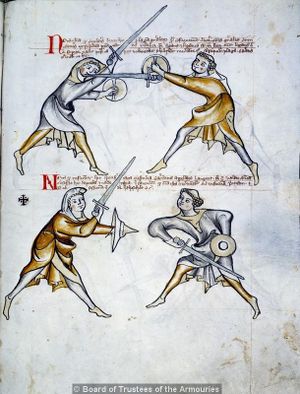

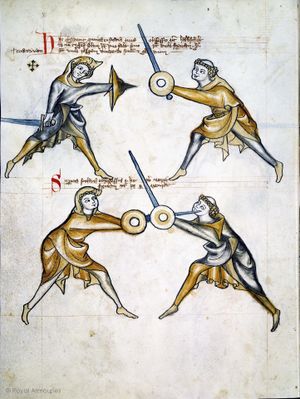

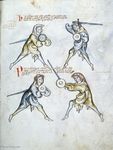

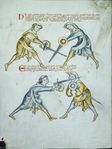

[11] It is to be seen, that the pupil is here binding and entering, so that he may place a schiltschlac, as below. But he should take heed of what is done by the priest, as after the bind the priest will be the first to act.

|

[2v] NOtandum quod scolaris [religat hic & calcat] ad hoc ut recipiat schiltslac vt infra Sed caueat de hiis que sunt facienda ex parte sacerdo[tis quia ...] post religationem sacerdos erit prior ad agendum

|

[12] It is to be seen, that the pupil has no option but to do a schiltslac, or to grip the arms of the priest with his left hand, namely sword and shield.

|

[N]Otandum est etiam quod scolaris nichil habet aliud facere quam schiltslac vel circumdare sinistra manu brachia sacerdotis videlicet gladium & scutum

|

[13] Verse:

Here the pupil binds and enters, for him is a schiltslac

Or with the left hand he grip the arms of the priest.

|

Versus: Hic religat calcat scolaris sit sibi schilslach

Siue sinistra manu circumdat brachia cleri

|

[14] The priest, on the other hand, has three options, namely mutation of the sword, so that it be higher, or durchtreten, or with the leftright hand grasp the pupil's arms, i.e. sword and shield.

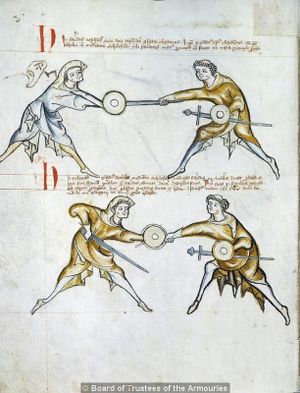

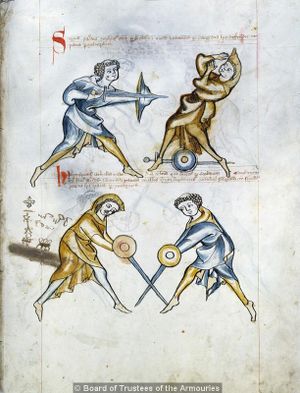

|

Sacerdos autem tria habet facere videlicet mutuare gladium q vt fiat superior Siue durchtreten vel sinistradextra manu comprehendere brachia* scolaris i. gladium & scutum

|

[15] These three are for the priest: durchtritt, mutation of the sword,

or with the right hand he may grasp sword and shield.

|

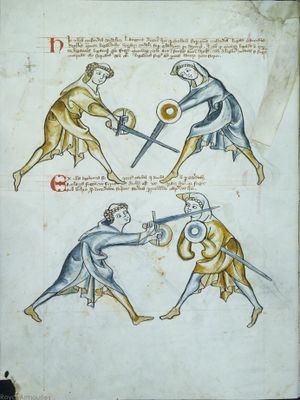

Hec tria sunt cleri durchtrit mutacio gladii

dextra siue manu poterit deprehendere gladium schutum

|

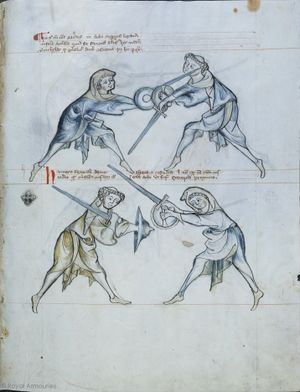

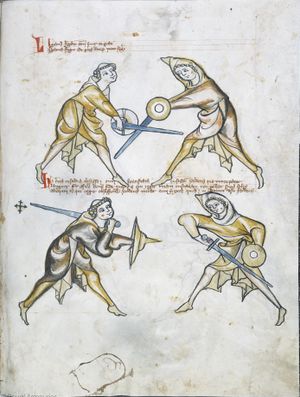

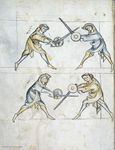

[16] Note that you find here what was said above, executed in the example.

|

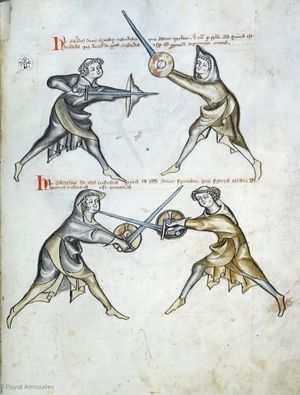

Nota quod supradictum est invenies hic exempli gestum

|

|

|

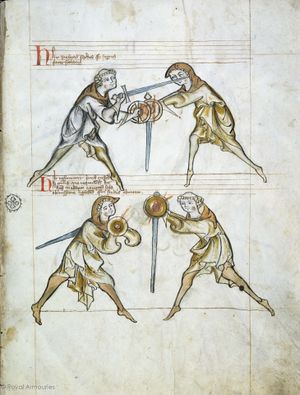

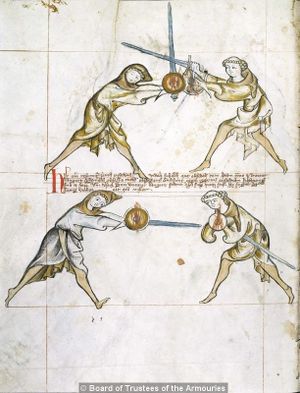

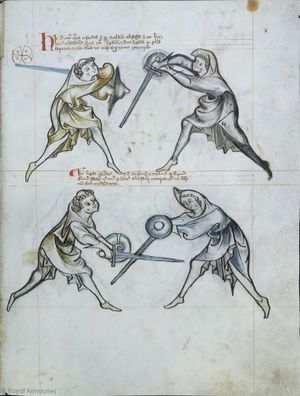

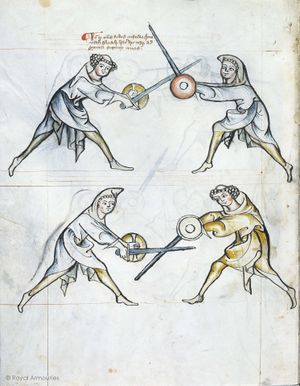

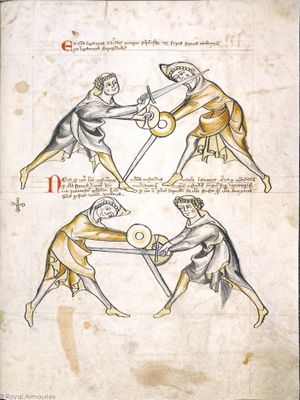

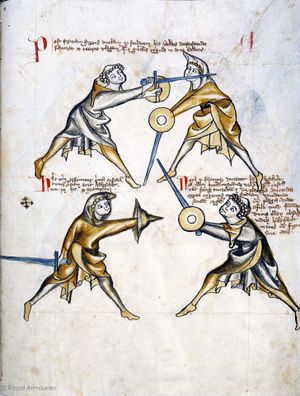

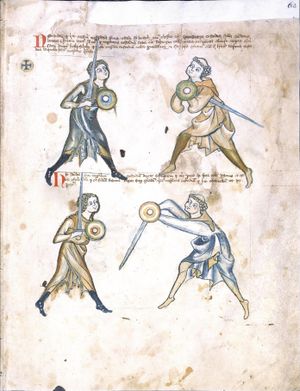

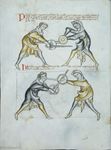

[17] (+) It is to be seen how the first ward is again assumed, because of certain actions of this first section, i.e. because of the first ward that was treated first. But all things that belong here you will find on the first page, up to the mutation of the sword.

|

[3r] 🕀 Notandum quod prima custodia resumitur hic propter quosdam actus illius primi frusti i. prime custodie de quibus prius actum est sed omnia que ponuntur hic invenies in primo folio vsque ad mutacionem gladii

|

[18] If halbschilt is assumed, fall

below both sword and shield.[9]

|

Dum ducitur halpschilt cade

sub gladium quoque scutum

|

|

|

[19] Here is a binding of the pupil's, and all other things, of which was talked above, until the mutation of the sword.

|

[3v] Hic fit religatio ex parte scolaris & omnia alia de quibus superi[u]s dictum est vsque infra ad mutationem gladij.

|

[20] Here the pupil is wanting good counsel how he could withstand this, and you must know, that if the game stands as here, then a stich must be executed, as commonly contained in the book, even if here is no image.

|

HIc eget scolaris bono consilio quomodo possit resiste[re] huic Et est sciendum quod quando ludus ita se habet vt hic tu[nc] debet duci stich sicut generaliter in libro continetur quamuis non sint ymagines de hoc.

|

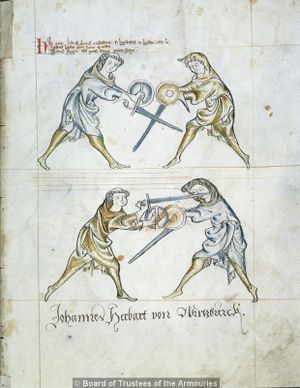

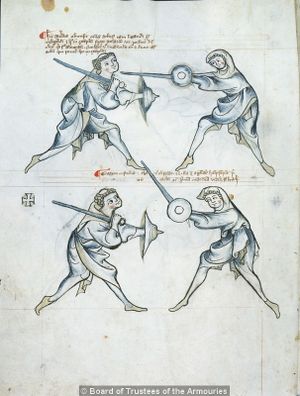

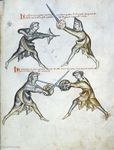

[21] It is to be seen, that the priest is here mutating the sword, because he was below earlier, now he will be above. Then, he moves the free sword upwards, which is called nucken, whence follows a separation of sword and shield of the pupil's.

|

NOtandum quod sacerdos mutat gladium hic quia fuit inferior nunc vero erit superior demum seorsum ducit gladium post capud adversarij sui quod nuncupatur nucken de quo generatur separatio gladij et scuti scolaris.

|

[22] Thence the verse:

Such is the monk's nucken,

where most of the common will schutzen.

|

Vnde v[ersus]. Clerici sic nucken generales non nulli schutzen.

|

|

|

[23] Here the priest should pay attention that he tarry not one instant with the sword, lest from that instant arise an act which is called grappling, but he must immediately re-establish the binding out of caution.

|

[4r] CAveat hic sacerdos ne faciat aliquam moram cum gladio ne generatur ex illa mora actus quidam qui vocatur luctacio sed statim debet reformare ligaturam propter cautionem

|

[24] (+) Here the first ward is re-assumed, to which ward the displacement will be very rare, because none uses to apply it save the priest or his clients, i.e. his students, and this displacement is called krucke, and I counsel in good faith that the one executing the ward should bind immediately after the displacement, because it is not good to tarry, or that he should do aught by which he may be saved, or that he should immediately do that, which his displacer does.

|

🕀 HIc resumitur prima custodia cuius custodie obsessio erit valde rara quia nu[llu]s consweuit eam ducere nisi sacerdos vel sui clientuli i. discipuli & nuncupatur illa obse[ssio] krucke & consulo bona fide quod ille qui regit custodiam statim post obsessionem ligat quia non est bonum latitare vel aliquid talium faciat per quod possit salvari vel saltim ducat id quod ipse possessor ducit

|

[25] You must know that the displacer must not hesitate, but he should execute immediately a stich towards the displacer, so that his adversary cannot deliberate what he intend, and that should diligently comprehended.[10]

|

Sciendum quod obsessor non debet h[esitare sed] ducat statim stich post obsess[ionem ...] tunc non potest adversarius delibe[rare quod] intendat & hoc diligenter intell[igatur]

|

|

|

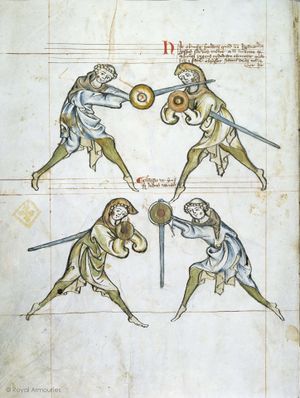

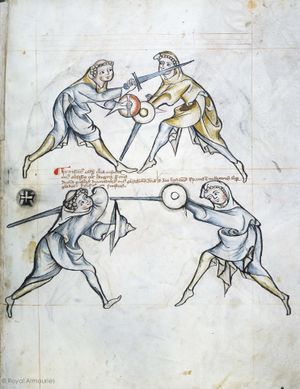

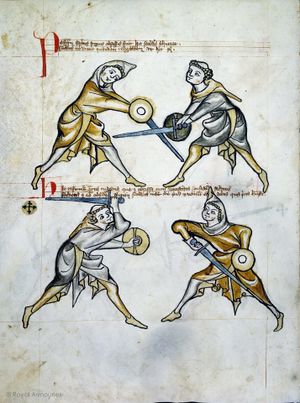

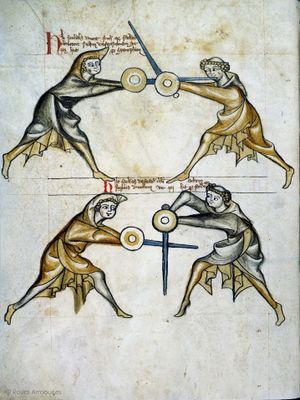

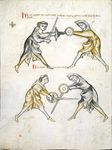

[26] Here the priest binds above the pupil's displacement, and immediately, all the preceding things which you had above; granted, you did not have the other two images which follow, where he grasps sword and shield.

|

[4v] HIc ligat sacerdos super obsessioenem discipili & inmediate veniunt omnia precedentia que prius habueras licet alias duas ymagines non habueris que subsecuntur vbi recipit gladium & scutum

|

[27] Note that whenever binder and bound are competing as here, then the bound may flee whither he chooses, if he likes, and this is required in all bindings. But of this you must be admonished, that where ever the bound (flees to), you should follow him.

|

Nota quod quandocumque ligans & ligatus sunt in lite vt hic tunc ligatus potest fugere quocumque vult si placet & requiritur in omnibus ligaturis sed de hoc debes esse munitus vt vbicumque ligatus sis sequens eum

|

[28] Binder and bound[11] are adverse and irate;

The bound flees to the side,[12] I try to follow.

|

Ligans ligati contrarij sunt & irati

ligatus fugit ad partes laterum peto sequi

|

[29] Here the priest teaches his pupil, how from these above things he may grasp sword and shield. And you must know, that the priest cannot free himself from such a grip without the loss of sword and shield.

|

HIc docet sacerdos discipulum su[um quo] modo debet ex hiis superioribus recipere gladium & scutum & sciendum quod sacerdos non potest absolui a tali deprehensione sine amissione gladij & scuti

|

|

|

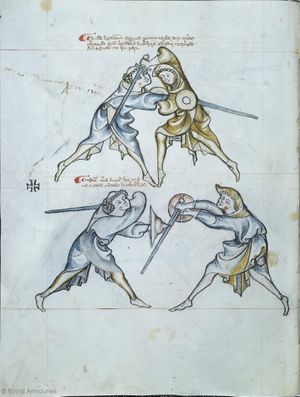

[30] Here the priest defends against what the pupil did above.

|

[5r] HIc defendit sacerdos quod superius fecit scolaris

|

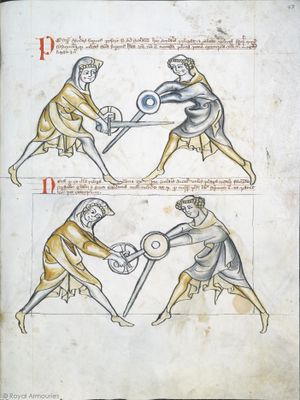

[31] (+) Here the first ward is re-assumed, but all that is necessary you have here in it, except only the omission of the binding, which the pupil omits.

|

🕀 HIc resumitur prima custodia sed omnia que requiruntur hic habes in eadem excepta sola obmissione ligacionis quam scolaris obmittit

|

|

|

[32] Here the pupil has neglected to bind, and the priest has promptly entered, and not undeservedly, as whenever the one assuming the ward omits something he should do, the displacer must immediately enter, as here.

|

[5v] HIc obmisit scolaris quod non ligauit prossus sacerdos intrauit & non inmerito quia vbicumque regens custodiam obmittit quod suum est facere obsessor statim debet intrare vt hic

|

[33] (+) Displacement as before, but the game is varied.

|

🕀 ¶ Obsessio vt prius sed ludus variatur

|

|

|

[34] Above, the priest displaced the pupil. Here now, the pupil is executing the same action as the priest before. But the displacer should enter first, if the pupil omits it, as below. Also, he should take care that the other reach not his head, which he may.

|

[6r] SVperius sacerdos obsedit scolarem hic vero scolaris ducit eundem lu actum quem duxit sacerdos sed obsidentis prius est intrare si sacerdos scolaris obmittit vt infra preterea caueat hic ne alter recipiat capud quod potest

|

[35] And from the above actions, the priest enters, I have said: he should therefore mind his head.

|

ET hiis superio[ri]bus sacerdos intrat dixi caveat ergo capud

|

|

|

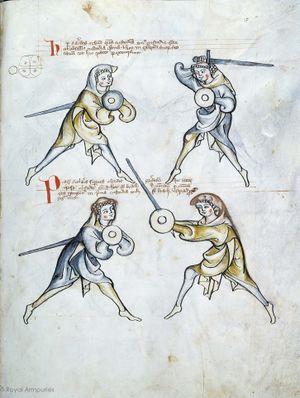

[36] (+) Here the first ward is re-assumed, namely the one under the arm, which is displaced with a certain counter that is called langort, and it is a common displacement, and the counters to this displacement are, for the part of the one assuming the ward, bindings above and below,

|

[6v] 🕀 HIc iterum resumitur prima custodia videlicet sub brachio* que obsedetur cum quodam contrario quod dicitur langort & est generalis obsessio cuius obssessionis contraria sunt ex parte regentis custodiam ligationes sub et supra

|

[37] Whence the verse:

When langort is executed, do bind immediately, above or else below.

But the higher binding is always more useful than the lower one.

|

vnde versus Dum ducitur langort statim liga sub quoque supra Sed superior ligacio semper vtilior erit quam inferior

|

|

|

[38] Here the game of the former ward will take place, namely of binder and bound,

|

[7r] HIc erit ludus prioris custodie scilicet ligantis & ligati

|

[39] Whence the verse:

Binder and bound are adverse and irate;

The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

|

vnde versus Ligans ligati contrarij sunt & irati ligatus fugit ad partes laterum peto sequi

|

|

|

[41] (+) First ward and common displacement as above, but the game varies at the end of the passage.

|

[7v] ⊕ Custodia prima [&] obsessio generalis vt supra sed variatur ludus in fine frusci[13]

|

[42] Above

- Below. But the priest has bound, in spite of being below.

|

- ¶ Inferior Sed sacerdos ligauit licet sit inferior

|

|

|

[43] Here a mutation of the sword below is taking place.

|

[8r] ¶ Hic fit mutatio gladij inferioris

|

|

|

[44] (+) The first ward is re-assumed and displaced by the first displacement, namely halpschilt, and you will have all of the above.

|

[8v] + Custodia prima resumitur hic et obsedetur cum prima possessione videlicet halpschilt et habebis omnia priora

|

[45] Verse:

When halbschild is assumed, fall

below both sword and shield.

|

V[ersus:] Dum ducitur halpschilt cade sub gladium quoque scutum

|

| One leaf (four plays) is missing between 8v and 9r.

|

|

|

[46] (+) It can be seen how here is taught in which way the second ward may be displaced. And I say the second ward, because the third ward which is given to the left shoulder, does not differ much from the second. But here we speak of the second ward, which is given to the right shoulder. And from the same ward, the displacer executes the displacement called schutzen, because every ward has its protection (which is the meaning of schutzen).

|

[9r] 🕀 Notandum quod hic docetur qumodo debeat secunda custodia obside & dico secunda custodia quia tertia custodia non multum differt a secunda que habetur in humero d sinistro sed hic loquimur de secunda custodia que datur humero dextro Et de eadem custodia obsessessor ducit obsessionem que vocatur schutzen quare quelibet custodia tenet vnam proteccionem i. schutzen

|

[47] Here the priest places himself in a similar way to the pupil and teaches, what will follow from these things. And you must know that (according to the true teaching of the priest) he who was the first to displace, can do three things: firstly, he can push the sword downwards and then durchtreten; secondly, he can execute a blow[14] from the right side; thirdly, he can execute a blow from the left side. Note that the opponent can do the same, even though the displacer is the first to be ready.

|

Hic ponit se simili modo sacerdos ad scolarem et docet quid ex hijs fiat & sciendum quod salua doctrina sacerdotis qui prius fuit obsessorus potest tria facere Primo potest exprimere gladium deorsum & tunc durchtreten Secundo potest recipere plagam latere dextro Tertio potest recipere plagam latere sinistro Nota quod hoc idem potest facere aduersarius licet obsessessor ad hoc prius sit paratus

|

|

|

[48] Here the pupil, instructed by the priest, executes an action that is called durchtritt.[15] He might get an opportunity far a strike to the left, as it is done by general fencers, or to the right, as it is done by the priest and his youths. To counter these two possibilities, the priest may, with the sword under the arm, reach the bare hands of him who executes the abovementioned strikes, although this counter is not depicted in the example image.

|

[9v] ¶ Hic scolaris instructus mediante consilio sacerdotis ducit actum quemdam qui nuncupatur durchtritt posset tamen recipisse plagam tam sinistram que ducitur ex parte dimicatorum generalium quam dexteram que consueuit duci ex parte sacerdotis & suorum iuuenium Contrarium illarum duarum viarum erit sacerdotis euntis cum gladio sub brachio* qui tunc attingit manus nudas ducentis plagas supradictas Licet contrarium istud non sit depictum in exemplum ymaginum

|

[49] Note that the priest deflects the action mentioned above while the pupil is still underway. The priest demonstrates this, depressing the pupil's bound sword, as shown here in the image. Later, you may learn what the priest will make of this if you pay careful attention etc.

|

¶ Nota quod sacerdos defndit hic actum superius dictum quia cum scolaris vero esset in actu itineris sacerdos religando atque subpremendo gladium scolaris ligatum demonstrat vt hic patet per exemplum Preterea quid sacerdotem ex hijs facere contingat si diligenter inspexeris poteris edoceri & cetera

|

|

|

[50] Here, as the priest is in the act of binding from above, he teaches the pupil, what may be done against this, namely stichslac, which he generally recommends, as shown here in the example.

|

[10r] ¶ Hic vero cum esset sacerdos in actu superius ligandi informat scolarem quid sit faciendum aduersus hec videlicet stichslac quod generaliter ducere consueuit Patet hic per exemplum

|

[51] (+) "the second to the right shoulder", i.e. the second ward. And note, that both the one assuming the ward and the one displacing it are in the same position as in the previous example.

|

+ Hvmero dextrali datur altera .i. custodia & nota quod tam rector custodie quam obsessor eiusdem sunt in eodem actu vt supra exemplo proximo

|

|

|

[52] Here, the priest obits to bind or being bound, and this as an example for his students, so that these may learn what is to be done; the pupil attacks and executes an action put here in the example.

|

[10v] ¶ Hic sacerdos obmisit omnes actus tam ligandi quam religandi & hoc in exemplum suorum scolarium vt possint dischere quid sit faciendum scolaris vero inuadendo eum & ducit illum actum qui ponitur hic in exemplum

|

[53] (+) same ward, but with a different displacement, and it is the one called halbschilt first treated displacing the first ward, i.e. the one under the arm.

|

⊕ ¶ Eadem custodia & alia vero obsessio & est illa que appellatur halpschilt prius tacta contra primam custodiam videlicet sub brachio

|

|

|

[54] Note how many ordinary fencers will be seduced by this displacement shown here. They think they can achieve a separation of sword and shield by means of the strike executed here. This is however not the case, because the displacer tarries, which could endanger him, but this [separation] executed is depicted here for all that wish to make use of the counsel of the priest.

|

[11r] NOta quod multi generales dimicatores seducuntur ista obsessione hic posita qui credunt ?fiere posse separacionem scuti & gladij mediante plaga illa que ducitur hic quod secus est quare obsessor non facit moram aliquam per quam possit periclitari sed illa hic ducta depicta est in exemplum omnibus volentibus vti consilio sacerdotis

|

[55] Here, the priest is about to execute the above strike. He teaches the pupil to turn sword and shield and to attack with the sword as here, so that the opponent may not effectively execute the strike.

|

NIc vero cum sacerdos esset in actu ducendi plagam superiorem docet scolarem vertere scutum & gladium intrando cum gladio vt hic quod is qui existens adversarius plagam ducere nequiuit ad effectum

|

|

|

[56] (+) Here the priest re-adopts the first ward, i.e. the one under the arm; some things were omitted which you had not put before, as shown in the example below.

|

[11v] 🕀 HIc resumit sacerdos custodiam primam videlicet sub brachio obmissis quibusdam prius non positis vt patet infra per exemplum

|

[57] You might ask how the pupil should attack the priest. And it should be known that the priest by tarrying omits all defence, in order to teach the pupil, who, as he stands, without moving sword or shield, approaches, i.e., soon he has the opportunity to strike, as shown in these images.

|

¶ Posset quis dubitare quomodo scolaris inuaderet sacerdotem & sciendum quod sacerdos latitando obmittit omnes suas defensiones informando scolarem qui sicut stst non variando scutum nec gladium magis appropinquat i. paulo plus recipiendo plagam vt hic patet per ymagines

|

|

|

[58] (+) Here, the priest adopts third ward, which is displaced by the student as shown. The counter to this displacement will be a bind, and I say bind, but only above, and no other as in the example below.

|

[12r] ⊕ HIc ducetur tertia custodia que per scolarem obsessa est vt hic cuius obsessionis contrarium erit ligacio & dico ligacio quare sola superior & non alia vt infra proximo exemplo

|

[59] Here, the priest binds, which is better and more profitable, because if he did aught else less occupying the adversary's sword, it would be to his loss.[16]

|

¶ Hic ligat sacerdos quod est melius & vtilius quare si quid aliud faceret quominus gladius aduersarii occuparetur in dampnum suum redundaret

|

|

|

[60] From the above bind, the priest teaches his little client to get sword and shield by embracing the arms of his opponent, as shown here.

|

[12v] ¶ Ex illa ligacione superius proxime tacta docet sacerdos clientulum suum circumdatis brachijs adversarij recipere gladium & scutum vt hic patet

|

[61] Here the third ward is adopted, as before, and the same displacement, but the game is varied.

|

🕀 ¶ Custodia tertia ducetur hic vt prius & eadem obsessio licet varietur ludus

|

|

|

[62] Here the priest teaches his little client, who executes a displacement, and he teaches him to enter if a bind is omitted.

|

[13r] ¶ Hic docet sacerdos clientulum suum qui ducit obsessionem & docet eum intrare si obmittuntur ligaciones

|

[63] (+) The same third ward, viz. on the left shoulder, and the same displacement called halbschilt, as above.

|

🕀 ¶ Eadem custodia tertia videlicet in humero sinistro & est eadem obsessio que vocatur halpschilt vt supra

|

|

|

[64] Note that all actions of the first ward, viz. under the arm, are here, up to the next sign of the cross.

|

[13v] ¶ Nota quod omnes actus custodie prime videlicet sub brachio habuntur his vsque ad proximum signum crucis

|

|

|

[65] (+) Here the third ward is re-adopted, which will be displaced by langort, which all common fencers execute, and the counter to this displacement are two binds, one on the right above the sword, the other on the left.

|

[14r] 🕀 ¶ Hic resumitur eadem tertia custodia cuius obsessio erit langort quam omnes ducunt generales dimicatores et cuius obsessionis contraria sunt due ligaciones quarum vna est in dexteris super gladium reliqua vero in sinistra

|

|

|

[66] Verse:

Binder and bound are adverse and irate;

The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

|

[14v] ¶ Versus Ligans ligati contrarij sunt & irati ligatus fugit ad partes laterum peto sequi

|

[67] (+) Now that the third ward has been treated, here the fourth is treated, which will have halbschilt as its displacement, and all that you had before you will find here up to the next sign of the cross.

|

+ ¶ Postquam determinatum est de tertia custodia hic determinat de quarta cuius obsessio erit halpschilt que omnia prius habuisti invenies hic vsque ad proximum signum crucis

|

| One leaf (four plays) is missing between 14v and 15r.

|

|

|

[68] (+) Here the priest re-adopts the fourth ward; the displacement of this fourth ward will be the first ward, and this as an example to his pupils, as here shown in the example.

|

[15r] ⊕ HIc sacerdos resumit quartam custodiam cuius custodie quarta erit obsessio custodia prima & hoc in exemplum suorum scolarium vt hic patet per exemplum

|

[69] After above the pupil has displaced the priest, here he again displaces him, and that below the arm, and note how all this has been treated with the first ward, i.e. the one under the arm, up to the next sign of the cross.

|

Postquam scolaris superius obsedit sacerdotem hic iterum ipse obsedit eum & hoc sub brachium & notandum quod omnia ista tanguntur in prima custodia videlicet sub brachium vsque ad proximam signum crucis

|

|

|

[No text]

|

|

|

|

[70] (+) Here the first ward is re-adopted, viz. under the arm, and its displacement will be langort, and it is common and of limited value, and note that he who adopts the ward has three possibilities: firstly, he may bind right, above the sword; secondly, he may left, below the sword; thirdly, he may grip the sword with his hand, as shown below in the next example.

|

[16r] 🕀 Hic resumitur custodia prima videlicet sub brachio cuius obsessio erit langort & est generalis & modicum valens ¶ & nota quod regens custodiam tria habet facere Primo potest ligare in dextris super gladium Secundo potest ligare in sinistris sub gladio Tertio potest comprehendere gladium manu vt infra patet exemplo proximo

|

|

|

[71] Here the priest grips - i.e. he teaches to grip - the displacer's sword. And note that the sword of said displacer may not be freed except by means of a schiltslac, where the priest's hand is struck with the shield, as below in the next example.

|

[16v] HIc sacerdos deprehendit siue docet deprehendere gladium obsedentis & nota quod gladius ipsius obsedentis non potest absolui nisi mediante schiltslac vbi sacerdotis manus percutiet cum scuto vt infra exemplo proximo

|

[72] Here the pupil's sword is freed by means of a schiltschlac, and the priest should take care that the pupil does not execute a strike to his head, or a general stab, which the priest is wont to teach his students. Also, you should know that if the pupil strike to the head, execute a protection, with the sword together with the shield in the left hand, and so you will strike the shield from the hands of your adversary, as shown below in the next example.

|

HIc relevatur gladius scolaris mediante schiltslac et caueat sacerdos ne scolaris ducet plagam capiti siue fixuram generalem quam sacerdos consueuit docere discipulos suos Preterea scias quod si scolaris dat plagam capiti protectionem duc gladio connexque scuto quod habetur in sinistra manu & sic frangis scutum de manibus tui aduersarij vt patet infra proximo exemplo

|

| Four leaves (sixteen plays) are missing between 16v and 17r.

|

|

|

[73] (+) Here the priest adopts the sixth ward, which is given to the breast. And note, it is solely this stab that must be executed which is executed from the fifth ward, up to the next sign of the cross.

|

[17r] 🕀 HIc sacerdos ducit sextam custodiam que datur pectori & nota quod solum illa fixura est ducenda que ducetur de quita custodia vsque ad proximum signum crucis

|

[74] Here the priest from the said sixth ward executes a stab, and a stab is also executed from the fifth ward.

|

HIc sacerdos de ista custodia sexta iam dicta ducit fixuram que fixura etiam de quinta custodia est ducenda

|

|

|

[75] Here the pupil by binding resists and deflects this stab of the priest's in the next above in the next example thus.

|

[17v] HIc scolaris per religacionem resistit & defendit sacerdoti illam fixuram in proximo superius in proximo exemplo per ipsum facto

|

[76] (+) After all the wards above have been treated, here the seventh ward is treated, which is called langort, and note that there are four binds, that answer to this ward, namely two from the right, and the other two from the left. But here we speak only of the first bind above the sword, which you have all in the first ward, up to the fourth example, where sword and shield are taken.

|

🕀 POstquam determinatum est de omnibus custodijs supradictis hic determinat de septima custodia que nuncupatur langort & notandum quod quatuor sunt ligaciones que respiciunt illam custodiam videlicet due liguntur de dextra parte relique vero due de sinistra parte sed loquimur hic primo de ligatura s super gladium quod habes totum in custodia prima vsque ad quartum exemplum vbi recipitur gladius & scutum

|

|

|

[77] It is to be seen how the pupil was the first to bind above the priest's sword in the preceding example. Here, the priest approaches and erects his sword and shield for the protection of the head.

|

[18r] NOtandum quod scolaris prius in exemplo immediate precedenti fecit ligaturam super gladium sacerdotis hic sacerdos appropinquat erigendo gladium & scutum propter proteccionem capitis

|

[78] Here the pupil can perform shiltslac, and form the counter he can inflict a blow to the priest.

|

HIc scolaris recipit shiltslac & ex contrario plagam infert sacerdoti

|

|

|

[79] Here the bound, i.e. the one below, grips sword and shield of the one above.

|

[18v] HIc recipit ligatus i. inferior gladium et scutum superioris.

|

[80] Here the pupil voluntarily drops sword and shield, intending to grapple with the priest as below.

|

HIc dereliquit voluntarie scolaris gladium & scutum volens luctare cum sacerdote vt infra.

|

|

|

[81] Above the priest was grabbed by the pupil and forced to grapple, which the priest may prevent as shown in the example.

|

[19r] Svperius sacerdos deprehensus fuit per scolarem in modum luctationis quod sacerdos hic defendit vt patet per exemplum

|

[82] (+) Here the same final ward is adopted by the pupil. The priest counters, and it is one of the four binds, namely the one below and left, as shown in the images.

|

🕀 HIc resumitur iterum illa custodia vltima que ducetur per scolarem Contrarium vero ducet sacerdos & est vna ligatura de illis quatuor ligaturis videlicet subligacio in sinistra parte vt hic patet per ymagines

|

|

|

[83] After the example above, in the following the priest is bound from below, but the pupil may reach the priest's head, because his sword was higher, and note, in all binds from below, one should guard the head, lest it be hit as here.

|

[19v] POstquam superius exemplo proximo subligatum est per sacerdotem scolaris vero recipit capud sacerdotis quia fuit superior gladius suus & nota quod quandocunque subligatur capud debet teneri in custodia ne percutiatur vt hic.

|

[84] Whence the verse:

When binding from below, take care that you are not deceived

When you are bound from below, the head of the binder can be reached.

|

vnde versus Dum subligaueris caueas ne decipieris Dum subligatur capud ligantis recipiatur

|

[85] Above, the pupil executes a strike and hits the head of the priest, which the priest prevents here by countering, as shown in the example.

|

Svperius scolaris duxit plagam percutiens capud sacerdotis quod sacerdos hic defendit quia ducit contrarium vt patet per exemplum

|

|

|

[86] (+) Here the final ward is again adopted, which is called langort, and here the priest is adopting it. But the pupil executes one of the four binds, viz. above the sword, as shown here in the example.

|

[20r] 🕀 HIc iterum ducitur vltima custodia que nuncupatur langort quam in hoc loco regit sacerdos scolaris vero de hijs quatuor ligacionibus ducit vnam videlicet super gladium vt patet hic per exemplum

|

[87] After above there was a bind above the priest's sword, one may see here how the priest defends against this by an action called stich, as shown here.

|

POstquam superius ligatum est super gladium sacerdotis vt supra visum est hice vero sacerdos defendit per illum actum qui vocatur sthich vt patet hic

|

|

|

[88] (+) Here the final ward is adopted, viz. langort, by the pupil. Above this ward, the priest binds with one of the four binds, viz. above the sword and to the right. And note that whenever there is a bind, the bound may flee from the binder to wherever he likes, to the left or to the right. Thence you may diligently see that if he flees, you will follow him, as in the verse: The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

- Binder and bound are adverse and irate;

The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

|

[20v] 🕀 HIc vltima custodia videlicet Langort ducitur hic per scolarem super quam custodiam ligat sacerdos de illis quatuor ligacionibus vnam videlicat super gladium in dextris & nota quod quandocumque ligatum est ex parte ligantis ligatus potest fugere quocumque vult aut in sinistris aut in dextris vnde diligenter videas si fugere incipiat dum sequaris vnde versus ligatus fugit ad partes laterum peto sequi

|

[89] From this bind treated above, executed by the priest, the pupil flees as said above, and as shown here: Because he flees under the arm, the priest immediately follows, cutting his head like here.

|

Ex illa ligatura superius tacta que ducta est per sacerdotem scolaris fugit vt supra dictum est vt patet hic quia fugit sub brachio quod immediate sequitur sacerdos percutiendo capud vt hic

|

|

|

[90] (+) Note that this is a different ward, viz. upper langort which is adopted here by the priest as an example to his pupils, and he instructs his pupil to execute this action, viz. to position himself as shown here in the example.

|

[21r] 🕀 NOta quod hic est alia custodia videlicet superior Langort que ducitur hic per sacerdotem suis scolaribus in exemplum iubendo scolarem suum ducere illum actum videlicet ponendo se ad eum vt patet hic per exemplum

|

[91] Here the priest binds in order to counter the pupil and it will be one of those four binds, viz. above the sword and to the right, which you had all in another part treated above.

|

HIc sacerdos religat defendendo atque contradicendo scolari & erit vna ligacio de illis quatuor ligacionibus videlicet super gladium in dextris quod habes superius totum in alijs supradictis

|

|

|

[92] After above the priest had bound, here the pupil wants to hit the priest in another way, and note that as the priest thinks that he could enter a bind, the pupil hits this same priest's arms. Note also that he not only hits the arms, but the power of this blow lies in the stab, which may also be executed here.

|

[21v] POstquam superius religatum est per sacerdotem hic scolaris querit alias vias percutiendi sacerdotem & notandum quod cum credit se sacerdos posse ligare scolaris interim percutit brachia ipsius sacerdotis supradicti Nota hic etiam quod non solum percutuntur brachia sed vis istius actus siue plage consistit in fixura que potest hic duci

|

[93] Here the priest notices that his arms are endangered, and he draws himself back, intending to strike, but the pupil follows as here etc.

|

HIc sacerdos sentiens brachia sua esse lesa volens ducere plagam trahendo se seorsum demum scolaris sequitur vt hic & cetera

|

|

|

[94] (+) Here a common ward is adopted, which is called vidilpoge,[17] executed by the priest. The pupil counters it positioning himself as shown here in the images.

|

[22r] 🕀 HIc ducetur quedam custodia generalis que nuncupatur vidilpoge quam regit sacerdos scolaris vero contrariando sic ponendo se ad ipsum vt patet hic per ymagines

|

[95] Then, the pupil placed his sword on the priest's arm, which also counts as a bind, as shown above. Here the priest turns the hand holding the shield and grasps the pupil's sword, as in this example.

|

POstquam scolaris posuit gladium suum super brachium sacerdotis quod habetur etiam pro ligatura vt patet superius hic sacerdos vertit manum que regit scutum recipitque gladium ipsius scolaris vt in hoc exemplo

|

|

|

[96] (+) Here the same ward is re-adopted, viz. vidilpoge, executed by the priest, the pupil acting as above.

|

[22v] 🕀 HIc iterum resumitur illa custodia videlicet vidilpoge & ducitur per sacerdotem scolaris ducit hic idem vt supra

|

[97] Here the priest binds as above.

|

Hic religat sacerdos vt supra

|

|

|

[98] From this bind the priest does a schiltslac as treated often above, from abovementioned binds.

|

[23r] Ex illa ligatura sacerdos recipit schiltslac vt supra sepius tactum est ex ligaturis supradictis

|

[99] (+) Note that the final ward is re-adopted, viz. langort, concerning which it should be noted that a stab is executed, by means of which the one in the ward is stabbed in the belly, i.e. he is penetrated by the sword, and note that of this paragraph not more than these two images are shown, which was the fault of the painter.[18]

|

🕀 NOta quod iterum hic resumitur vltima custodia videlicat Langort circa quod notandum est quod illa fixura ducetur hic mediante qua regens custodiam fingitum super ventrem siue penetratur gladio & nota quod non est plus depictum de illo frusco quam ille due ymagines quod fuit vicium pictoris

|

|

|

[100] (+) Here, the priest adopts his special ward, viz. langort, which is displaced by the pupil, whose displacement will be halpschilt, as shown here in the example.

|

[23v] 🕀 HIc ducit sacerdos suam custodiam specificatam videlicet Langort que opsedetur per scolarem cuius opsessio erit halpschilt vt patet hic per exemplum

|

[101] Here the priest puts himself under the sword of the pupil, as was often treated.

|

HIc ponit se sacerdos sub gladium scolaris quod sepius prius tactum est.

|

[102] Whence the verse:

If halbschilt is assumed, fall

Below both sword and shield.

|

Unde Versus Dum ducitur halpschilt cade sub gladium quoque scutum

|

|

|

[103] After the priest above positioned himself to the scholar, the scholar here binds and steps, intending to do which follows, because you had many forms above, it is not necessary to give more examples. Therefore the verse, "the binder and the bound" etc.

- Binder and bound are adverse and irate;

The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

|

[24r] POstquam sacerdos superius posuit se ad scolarem hic scolaris religat & calcat volens facere quod subsequitur & quia multas formas superius habetis vnde non est necesse plura ponere exempla vnde versus Ligans ligati & cetera

|

[104] Note that form this bind of the part of the pupil a useful strike is executed, viz. a separation of sword and shield of the priest, and entering (but no more of this is written in this book) as shown here in the example.

|

NOta quod ex illa religacione ex parte scolaris ducetur vtilis plaga videlicet faciendo separacionem gladij & scuti sacerdotis necnon intrando vt p quod nusquam plus in libro scriptum est vt patet hic per exemplum

|

|

|

[105] (+) Here the special ward of the priest's is re-adopted, which is called langort, as seen above, and again the pupil displaces it with haloschilt, as above, but other examples follow, as shown below.

|

[24v] ⊕ HIc iterum resumitur specificata custodia sacerdotis que nuncupatur Langort vt superius visum est deinde scolaris obsedit eum vt supra quod est halpschilt sed alia exempla subsecuntur vt patet infra

|

[106] Here the priest positions him to the pupil as was seen often before.

|

HIc sacerdos ponit se ad scolarem vt sepius prius visum est

|

|

|

[107] It is to be noted, that the pupil is here dealing a common strike, which all common fencers are wont to deal from the position just treated, namely when binder and bound are engaged and the binder who is above goes to the head and omits a schiltslac, from which follows a strike, and the priest enters, as here.

|

[25r] NOtandum quod scolaris ducit hic plagam generalem quam consueuerunt ducere omnes generales dimicatores ex supradictis proxime tactis videlicet quando ligans & ligatus sunt in lite tunc ligans qui est superior vadit post caput & obmittit schiltslac mediante quo subsequitur plaga sacerdos vero intrat ut hic

|

[108] (+) Note, that here again the special ward of the priest is assumed that is called langort, but it is a very strange displacement that is depicted here, and very rare, and you must know that this can be reduced to the first ward and to the displacement called halpschilt etc.

|

⊕ NOta quod resumitur hic specificata custodia sacerdotis apellata Langort sed est valde aliena obsessio hic depicta & valde rara & sciendum quod omnia ista reducuntur ad custodiam primam et ad obsessionem que dicitur halpschilt & cetera

|

|

|

[109] Here, the priest executes the abovementioned stab, because the pupil, who has displaced in the previous example, omits all actions, because, had he bound, he would have been ?under-bound, as in the following example.

|

[25v] HIc sacerdos ducit quandam fixuram prius tactam quia scolaris qui fuerat obsessor supra exemplo proximo obmittit omnes suos actos quia si religasset fuisset subportatus vt patet infra exemplo proximo

|

[110] It is to be noted, that from these actions this abovementioned stab by the priest the pupil will here bind, which is necessary, if we want the stab depicted above to be deflected.

|

NOtandum quod ex hiis ista fixura superius tacta per sacerdotem erit hic quedam religacio facta per scolarem quod oportet de necessitate si volumus quod defendatur fixura superius depicta

|

| One leaf (four plays) is missing between 25v and 26r.

|

|

|

[111] Binder and bound are adverse and irate;

The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

|

[26r] LIgans ligati contrarij sunt & irati

ligatus fugit ad partes laterum peto sequi

|

[112] (+) Here, the third ward is displaced by the special ward of the priest's that is called langort, and I counsel in good faith, that he who is performing the third ward should not at all delay his actions, because otherwise the one performing the priest's displacement will enter with a stab, which is a common practice of the priest's.

|

+ HIc tertia custodia obsessa est cum specificata custodia sacerdotis que nuncupatur langort Et consulo bona fide quod is qui regit tertiam custodiam non protrahat suos actus alioquin is qui regit obsessionem sacerdotis intrat cum fixura quod est in communi vsu sacerdotis

|

|

|

[113] After the priest has been displaced above, the pupil does here schutzen, while the priest is executing a bind, as shown here.

|

[26v] POstquam sacerdos superius obsessus fuit hic scolaris schutzet sacerdos vero ducit quandam religacionem vt hic patet

|

[114] (+) Here the fourth ward is assumed again, and it is displaced by the special ward of the priest. It is now up to the priest to displace, and the pupil enters as above, and all the actions that you had before will follow.

|

⊕ HIc resumitur quarta custodia que est obsessa cum specificata custodia sacerdotis Sacerdotis est econtra obsidere aliquin scolaris intrat vt prius & veniunt omnes actus quos prius habuisti

|

|

|

[115] (+) Here again the fifth ward is assumed, and it is displaced by the special ward of the priest that is called langort, as shown in the example.

|

[27r] 🕀 HIc iterum sumitur quinta custodia que etiam obsessa est cum specificata custodia sacerdotis que dicitur langort vt patet hic per exemplum

|

[116] Binder and bound are adverse and irate;

The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

|

LIgans ligati contrarij sunt & irati

Ligatus fugit ad partes laterum peto sequi

|

|

|

[117] (+) Here the fifth ward is displaced, its displacement being halbschilt. And note, that the one executing the ward may do only two things: Firstly, he can execute a stab, secondly, he can execute a strike to divide shield and sword.

|

[27v] ⊕ HIc obsedetur quinta custodia cuius obsessio erit halbschilt & nota regens+ +custodiam solum habet due facere primo potest ducere fixuram secundo potest ducere plagam diuidendo scutum & gladium

|

[118] Above, the pupil was displaced. Here however, he gets to do a stab, as shown in the example.

|

Superius scolaris obsessessus est hic vero recipit fixuram vt patet per exemplum

|

|

|

[119] After the above stab executed by the pupil, here the priest defending does schutzen and gets the opportunity for a strike which is a general rule in the art of the priest.

|

[28r] POst fixuram superius ductam per scolarem hic sacerdos defendendo schutzet & recipit plagam hoc est generalis regula in arte sacerdotis

|

[120] (+) Here the fifth ward is resumed which will be countered by halpschilt as shown in the example.

|

⊕ HIc iterum resumitur quinta custodia cuius contraria erit halpschilt vt patet per exemplum

|

[121] Note, that whenever halbschilt is assumed against this fifth ward, or against the second ward, a strike from the one assuming the ward is always to be expected, which could divide sword and shield. Thence the counsel, that whenever you execute this displacement, i.e. halpschilt, you should enter with a stab without mercy.

|

NOta quod quandocumque ducetur halpschilt contra illam quintam custodiam dividendo scutum & gladium cum plaga vnde consulo quod quandocumque ducis illam obsessionem videlicet halpschilt intras cum fixura sine misericordia

|

|

|

[122] Here the pupil executes a stich, because the priest omits his defense, as shown here in the example.

|

[28v] HIc scolaris ducit stich, quare sacerdos obmittit suam defensionem vt patet hic per exemplum

|

[123] Here the priest deflects the action executed above, as shown here by the priest.

|

HIc sacerdos defendit illum actum superius ductum vt patet hic per sacerdotem

|

|

|

[124] First, as above in the third example of the pictures, the same stab is executed by the pupil, and this stab is deflected by the priest, by means of a schiltslac, as shown here in the example.

|

[29r] ¶ Prius quam superius in tertio exemplo ymaginarum fixura quedam ducta est per scolarem eandem vero fixuram sacerdos hic defendit recipiendo schilslac schiltslac ut patet hic per exemplum

|

[125] (+) Here the fifth ward is again resumed, of which much was said above, and it is to be noted that the priest is displacing the pupil with a displacement that is rare and very good, as an example for his students. And you have to know, that if the pupil executes a stab, which to execute is usually the use, the priest also must execute a stab against the stab of the pupil, because his will be more effective, entering with the left foot. But if he does not want to enter he should nevertheless retract his right foot and not omit this stab. But if the pupil displaces against him by means of halpscilt, the priest should fall below sword and shield, and then will follow those things which were seen before.

|

⊕ ¶ Hic iterum se resumitur quinta custodia de qua superius dictum est sepius & est notandum quod sacerdos obsedit scolarem obsessione quandam rara & valde bona in exemplum suorum discipulorum & sciatur quod si scolaris ducet fixuram que duci consueuit de consuetudine sacerdos debet etiam ducere fixuram contra fixuram scolaris quia sua magis valet intrando cum sinistro pede si autem intrare nequiuerit cedat cum dextro pede nichillominus non obmittatur quin etiam ipsa fixura perficiatur si autem scolaris obsedit eum econtrario mediante halpscilt sacerdos cadet sub gladio & scutum & tunc superueniunt ea que prius visa sunt in custodia prima.

|

[126] Thence the verse,

If halbschilt is assumed, fall

Below both sword and shield.

|

Vnde versus Dum ducitur halpscilt cade sub gladium quoque scutum

|

|

|

[127] Here the pupil completes his stab, the priest omitting all actions.

|

[29v] ¶ Hic scolaris perfecit suam fixuram sacerdos vero obmittit omnes suos actus

|

[128] Here note that the priest deflects the pupil's stab.

|

¶ Hic nota quod sacerdos defendit hic fixuram scolaris

|

|

|

[129] (+) It is to be seen that here the fourth ward is again assumed, and the displacement to this fourth ward is the special langort of the priest. But the displacer should see that the one assuming the ward does not execute a strike, as it would be dangerous to tarry; therefore he should execute schuzin, and finally not omit a stab.

|

[30r] + ¶ Notandum quod hic resumitur quarta custodia cuius quarte custodie obsessio est specificatum langcort sacerdotis videat autem obsessor ne regens custodiam ducet aliquam plagam quia periculosum erit sic diu latiare vnde ducat primo schuzin demum fixuram non obmittat

|

[130] Here, on the other hand, the priest is displacing the pupil, which I consider to be better, and what can be learned from anybody, because if he did not, the pupil would enter with a stab which would now be possible for him. And from these actions follows the game of the first ward, that is, of the binder and the bound, which is shown below in the first example.

|

¶ Hic sacerdos econtrario obsedit scolarem quod puto melius esse quod potest ab aliquo edoceri quia si hoc non fiet scolaris ipsum invaderit cum fixura quod nunc suus erit sed ex hiis oritur ludus prime custodie videlicet ligantis & ligati quod patet infra in exemplo proximo

|

|

|

[131] Here will be the bindings that were treated often above, whence the verse "the binder and the bound are contrary and enraged" etc.

- Binder and bound are adverse and irate;

The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

|

[30v] ¶ Hic erunt ligaciones que superius tacte sunt sepius vnde versus ligans ligati contraria sunt & irati & cetera

|

[132] From these above bindings, the pupil executes this strike lifting his sword to the head by means of a schiltslac.

|

¶ Ex illis ligacionibus superius ductis scolaris ducit illam plagam per caput ducendo gladium [median]te schiltslac

|

|

|

[133] It is to be seen that the priest deflects the above strike delivered by the pupil in this way, as the pupil's sword has been below, and as he was about to deliver the strike, moving his sword, the priest has the opportunity for a strike before the pupil could put his sword to its use, as shown here in the example.

|

[31r] NOtandum quod plagam superius ductam per scolare sacerdos defendit hic in hunc modum quia scolaris gladius fuit inferior & cum esset in actu ducendi plagam ducendo gladium seorsum sacerdos vero antequam scolaris ducat gladium suum ad usum debitum recipit plagam vt patet hic per exemplum

|

[134] (+) Here, the fourth ward is reassumed, whose displacement is the special langort of the priest. And it is to be noted, that whenever the game is set in this way, I counsel the one assuming the ward, and also the one displacing him, that none should delay what they have to do, i.e. on one hand the one assuming the ward, a displacement, on the other hand the one displacing, a stab.

|

⊕ NIc iterum resumitur quarta custodia cuius custodie obsessio erit specificatum langort sacerdotis & notandum quod quandocunque sic se habet ludus ut hic tunc consulo tam regenti custodiam quam obsedenti eam ne quisquam eorum protrahendo obmittat quod suum est videlicet ex parte regentis custodiam obsessio & ex parte obsidentis fixura

|

|

|

[135] Above, both the one assuming the ward and the one displacing it were referred to; and because the pupil, who was the displacer, will be quicker, he executes what he should, namely first schuzin, as here, and in the next example below a stab, because the priest is omitting all actions. Thus, the one entering first will be the first to do damage to his opponent.[16]

|

[31v] Superius dictum est tam de eo qui regit custodiam quam de eo qui eam pobssedit & quia prior erit scolaris qui superius fuerat obsessessor ducit quod suum est videlicet primo schuzin ut hic & infra exemplo proximo fixuram quia sacerdos omnes suos actus obmittit vnde qui prior vadit prior erit ad faciendum dampnum suo aduersario

|

[136] After the actions of the pupil's and the omission of actions of the priest's were discussed above, the priest is here omitting what he should do, and the pupil is completing the obvious attack, as shown here.

|

POst quam determinatum est superius de actibus scolaris & de obmissione actuum sacerdotis hic iterum sacerdos obmittit quod suum est donec scolaris suam perducit adessentem intracionem ut patet hic

|

|

|

[137] (+) It is to be seen, that the first ward is reassumed, i.e. the one below the arm, the replacement to which is the special second ward of the priest on the right shoulder, and take note, that the one assuming the ward will schuzin without delay, otherwise his opponent will execute halbschilt which would be disastrous for the one assuming the ward. And from here will be generated all the things related to the first ward that were treated in the first quire.

|

[32r] 🕀 NOtandum est quod hic resumitur custodia prima videlicet sub brachio cuius obsessio est specificata custodia secunda sacerdotis locata in humero dextro & nota quod regentis custodiam statim erit schuzin nulla mora interposita alioquin ex parte adversarij ducetur halbschilt quod erit regenti custodiam valde perniciosum & ex hiis generantur omnia que habuntur de prima custodia de quibus habetur in primo quaterno

|

[138] The priest, assuming the ward, is here executing schuzin, which will be for the reason that he was the first to be ready. And it is good counsel that the displacer will bind immediately above the sword of the one assuming the ward (which is here omitted), as shown in the example.

|

HIc sacerdos qui regebat custodiam ducit schutzin quod erit proptereo quia prior erit paratus & est bene[?] consulendum quod obsidens statim ligat super gladium ipsius regentis custodiam quod hic obmittitur ut patet per exemplum

|

|

|

[139] Here will be bindings, above and below, as they occur often, thence the verse "binder and bound" etc.

- Binder and bound are adverse and irate;

The bound flees to the side, I try to follow.

|

[32v] HIc e[runt] ligationes superius & inferiores que [?sepius] ducte sun[t] [...] Vnde versus Ligans ligati & ce[tera]

|

[140] From the above bindings, (the priest) Walpurgis[19] executes a schiltslac because she was higher, and quicker to be ready.

|

Ex hiis super[ioribus] allegacionibus sacerdoswalpurgis recipit schiltslac quia erat superior & prius parata

|

| One leaf (four plays) is missing after 32r.

|