|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Wiktenauer:Main page/Featured"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Infobox writer |

| − | | name = | + | | name = [[name::Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi]] |

| − | | image = File: | + | | image = File:Fiore delli Liberi.jpg |

| imagesize = 250px | | imagesize = 250px | ||

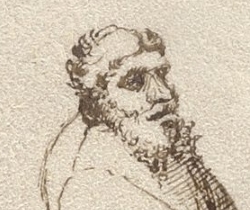

| − | | caption = | + | | caption = This master with a forked beard appears sporadically throughout both the Getty and Pisani Dossi mss., and may be a representation of Fiore himself. |

| pseudonym = | | pseudonym = | ||

| birthname = | | birthname = | ||

| − | | birthdate = | + | | birthdate = 1340s |

| − | | birthplace = | + | | birthplace = Cividale del Friuli, Friuli |

| − | | deathdate = | + | | deathdate = after 1420 |

| − | | deathplace = | + | | deathplace = France (?) |

| resting_place = | | resting_place = | ||

| − | | occupation = [[Fencing master]] | + | | occupation = {{plainlist |

| − | | language = [[ | + | | [[occupation::Diplomat]] |

| − | | nationality = | + | | [[Fencing master]]{{#set: occupation=Fencing master }} |

| + | | [[occupation::Mercenary]] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | | language = {{plainlist | ||

| + | | [[language::Middle Italian]] | ||

| + | | [[language::Renaissance Latin]] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | | nationality = Friulian | ||

| ethnicity = | | ethnicity = | ||

| citizenship = | | citizenship = | ||

| education = | | education = | ||

| alma_mater = | | alma_mater = | ||

| − | | patron = | + | | patron = {{plainlist |

| + | | Gian Galeazzo Visconti (?) | ||

| + | | Niccolò III d’Este (?) | ||

| + | }} | ||

| − | | period = | + | | period = |

| − | | genre = [[Fencing manual]] | + | | genre = {{plainlist |

| + | | [[Fencing manual]] | ||

| + | | [[Wrestling manual]] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| subject = | | subject = | ||

| − | | movement = | + | | movement = |

| − | | notableworks = | + | | notableworks = ''The Flower of Battle'' |

| − | |||

| manuscript(s) = {{collapsible list | | manuscript(s) = {{collapsible list | ||

| − | | | + | | Codex LXXXIV (before 1436) |

| − | | [[ | + | | Codex CX (before 1436) |

| − | | [[ | + | | [[Fior di Battaglia (MS M.383)|MS M.383]] (1400s) |

| − | | [[ | + | | [[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|MS Ludwig XV 13]] (1400s) |

| − | | [[ | + | | [[Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)|Pisani Dossi MS]] (1409) |

| − | | [[ | + | | [[Florius de Arte Luctandi (MS Latin 11269)|MS Latin 11269]] (1410s?) |

| + | | [[Fior di Battaglia (MS XXIV)|MS XXIV]] (1699) | ||

}} | }} | ||

| principal manuscript(s)= | | principal manuscript(s)= | ||

| − | | first printed edition= | + | | first printed edition= |

| wiktenauer compilation by=[[Michael Chidester]] | | wiktenauer compilation by=[[Michael Chidester]] | ||

| Line 42: | Line 55: | ||

| partner = | | partner = | ||

| children = | | children = | ||

| − | | relatives = | + | | relatives = Benedetto de’i Liberi |

| − | | influences | + | | influences = {{plainlist |

| − | + | | [[Johannes Suvenus|Johane Suveno]] | |

| − | | [[ | + | | [[Nicholai de Toblem]] |

| − | |||

| − | | [[ | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | | influenced = [[Philippo di Vadi]] | ||

| awards = | | awards = | ||

| signature = | | signature = | ||

| Line 55: | Line 67: | ||

| below = | | below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | ''' | + | '''Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi de Cividale d’Austria''' (Fiore delli Liberi, Fiore Furlano, Fiore de Cividale d’Austria; ca. 1340s - 1420s) was a late [[century::14th century]] knight, diplomat, and itinerant [[fencing master]]. He was born in Cividale del Friuli, a town in the Patriarchal State of Aquileia (in the Friuli region of modern-day Italy), the son of Benedetto and scion of a Liberi house of Premariacco. The term ''Liberi'', while potentially merely a surname, more probably indicates that his family had Imperial immediacy (''Reichsunmittelbarkeit''), either as part of the ''nobili liberi'' (''Edelfrei'', "free nobles"), the Germanic unindentured knightly class which formed the lower tier of nobility in the Middle Ages, or possibly of the rising class of Imperial Free Knights. It has been suggested by various historians that Fiore and Benedetto were descended from Cristallo dei Liberi of Premariacco, who was granted immediacy in 1110 by Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich V, but this has yet to be proven. |

| + | |||

| + | Fiore wrote that he had a natural inclination to the martial arts and began training at a young age, ultimately studying with “countless” masters from both Italic and Germanic lands. He had ample opportunity to interact with both, being born in the Holy Roman Empire and later traveling widely in the northern Italian states. Unfortunately, not all of these encounters were friendly: Fiore wrote of meeting many “false” or unworthy masters in his travels, most of whom lacked even the limited skill he'd expect in a good student. He further mentions that on five separate occasions he was forced to fight [[duel]]s for his honor against certain of these masters who he described as envious because he refused to teach them his art; the duels were all fought with sharp swords, unarmored except for gambesons and chamois gloves, and he won each without injury. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Writing very little on his own career as a commander and master at arms, Fiore laid out his credentials for his readers in other ways. He stated that foremost among the masters who trained him was one [[Johannes Suvenus|Johane dicto Suueno]], who he notes was a disciple of [[Nicholai de Toblem]]; unfortunately, both names are given in Latin so there is little we can conclude about them other than that they were probably among the Italians and Germans he alludes to, and that one or both were well known in Fiore's time. He further offered an extensive list of the famous ''condottieri'' that he trained, including Piero Paolo del Verde (Peter von Grünen), Niccolo Unricilino (Nikolo von Urslingen), Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli (Galeazzo Gonzaga da Mantova), Lancillotto Beccaria di Pavia, Giovannino da Baggio di Milano, and Azzone di Castelbarco, and also highlights some of their martial exploits. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The only known historical mentions of Fiore appear in connection with the Aquileian War of Succession, which erupted in 1381 as a coalition of secular nobles from Udine and surrounding cities sought to remove the newly appointed Patriarch (prince-bishop of Aquileia), Philippe II d'Alençon. Fiore seems to have supported the secular nobility against the Cardinal; he traveled to Udine in 1383 and was granted residency in the city on 3 August. On 30 September, the high council tasked him with inspection and maintenance of city's weapons, including the [[artillery]] pieces defending Udine (large crossbows and catapults). In February of 1384, he was assigned the task of recruiting a mercenary company to augment Udine's forces and leading them back to the city. This task seems to have been accomplished in three months or less, as on 23 May he appeared before the high council again and was sworn in as a sort of magistrate charged with keeping the peace in one of the city's districts. After May 1384, the historical record is silent on Fiore's activities; the war continued until a new Patriarch was appointed in 1389 and a peace settlement was reached, but it's unclear if Fiore remained involved for the duration. Given that he appears in council records four times in 1383-4, it would be quite odd for him to be completely unmentioned over the subsequent five years if he remained, and since his absence from records coincides with a proclamation in July of that year demanding that Udine cease hostilities or face harsh repercussions, it seems more likely that he moved on. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Based on his autobiographical account, Fiore traveled a good deal in northern Italy, teaching fencing and training men for duels. He seems to have been in Perugia in 1381 in this capacity, when his student Peter von Grünen likely fought a duel with Peter Kornwald. In 1395, he can be placed in Padua training the mercenary captain Galeazzo Gonzaga of Mantua for a duel with the French marshal Jean II le Maingre (who went by the war name “Boucicaut”). Galeazzo made the challenge when Boucicaut called into question the valor of Italians at the royal court of France, and the duel was ultimately set for Padua on 15 August. Both Francesco Novello da Carrara, Lord of Padua, and Francesco Gonzaga, Lord of Mantua, were in attendance. The duel was to begin with [[spear]]s on [[:category:Mounted Fencing|horseback]], but Boucicaut became impatient and dismounted, attacking Galeazzo before he could mount his own horse. Galeazzo landed a solid blow on the Frenchman’s helmet, but was subsequently disarmed. At this point, Boucicaut called for his poleaxe but the lords intervened to end the duel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fiore surfaces again in Pavia in 1399, this time training Giovannino da Baggio for a duel with a German squire named Sirano. It was fought on 24 June and attended by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, as well as the Duchess and other nobles. The duel was to consist of three bouts of mounted lance followed by three bouts each of dismounted [[poleaxe]], [[estoc]], and [[dagger]]. They ultimately rode two additional passes and on the fifth, Baggio impaled Sirano’s horse through the chest, slaying the horse but losing his lance in the process. They fought the other nine bouts as scheduled, and due to the strength of their armor (and the fact that all of the weapons were blunted), both combatants reportedly emerged from these exchanges unharmed. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fiore was likely involved in at least one other duel that year, that of his final student Azzone di Castelbarco and Giovanni degli Ordelaffi, as the latter is known to have died in 1399. After Castelbarco’s duel, Fiore’s activities are unclear. Based on the allegiances of the nobles that he trained in the 1390s, he seems to have been associated with the ducal court of Milan in the latter part of his career. Some time in the first years of the 1400s, Fiore composed a fencing treatise in Italian and Latin called "The Flower of Battle" (rendered variously as ''Fior di Battaglia'', ''Florius de Arte Luctandi'', and ''Flos Duellatorum''). The briefest version of the text is dated to 1409 and indicates that it was a labor of six months and great personal effort; as evidence suggests that at least two longer versions were composed some time before this, we may assume that he devoted a considerable amount of time to writing during this decade. | ||

| − | + | Beyond this, nothing certain is known of Fiore's activities in the 15th century. [[Francesco Novati]] and [[D. Luigi Zanutto]] both assume that some time before 1409 he accepted an appointment as court fencing master to Niccolò III d’Este, Marquis of Ferrara, Modena, and Parma; presumably he would have made this change when Milan fell into disarray in 1402, though Zanutto went so far as to speculate that he trained Niccolò for his 1399 passage at arms. However, while the records of the d’Este library indicate the presence of two versions of "the Flower of Battle", it seems more likely that the manuscripts were written as a diplomatic gift to Ferrara from Milan when they made peace in 1404. C. A. Blengini di Torricella stated that late in life he made his way to Paris, France, where he could be placed teaching fencing in 1418 and creating a copy of a [[fencing manual]] located there in 1420. Though he attributes these facts to Novati, no publication verifying them has yet been located and this anecdote may be entirely spurious. The time and place of Fiore's death remain unknown. | |

| − | + | Despite the depth and complexity of his writings, Fiore de’i Liberi does not seem to have been a very significant master in the evolution of fencing in Central Europe. That field was instead dominated by the traditions of 14th century master [[Johannes Liechtenauer]] in the Holy Roman Empire and of Fiore's near-contemporary [[Filippo di Bartolomeo Dardi]] in Italy. Even so, there are a number of later treatises which bear strong resemblance to his work, including the writings of [[Philippo di Vadi]] and [[Ludwig VI von Eyb]]. This may be due to the direct influence of Fiore or his writings, or it may instead indicate that the older tradition of Johane and Nicholai survived and spread outside of Fiore's direct line. | |

| − | ([[ | + | ([[Fiore de'i Liberi|Read more]]...) |

<dl> | <dl> | ||

<dt style="font-size:90%;">Recently Featured:</dt> | <dt style="font-size:90%;">Recently Featured:</dt> | ||

| − | <dd style="font-size:90%;">[[Joachim Meÿer]] – [[Paulus Hector Mair]] – [[Die Blume des Kampfes]] | + | <dd style="font-size:90%;">[[Sigmund Schining ain Ringeck]] – [[Joachim Meÿer]] – [[Paulus Hector Mair]] – [[Die Blume des Kampfes]]</dd> |

</dl> | </dl> | ||

Revision as of 00:26, 20 April 2016

| Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi | |

|---|---|

This master with a forked beard appears sporadically throughout both the Getty and Pisani Dossi mss., and may be a representation of Fiore himself. | |

| Born | 1340s Cividale del Friuli, Friuli |

| Died | after 1420 France (?) |

| Relative(s) | Benedetto de’i Liberi |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Friulian |

| Patron |

|

| Influences | |

| Influenced | Philippo di Vadi |

| Genres | |

| Language | |

| Notable work(s) | The Flower of Battle |

| Manuscript(s) |

MS M.383 (1400s)

|

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi de Cividale d’Austria (Fiore delli Liberi, Fiore Furlano, Fiore de Cividale d’Austria; ca. 1340s - 1420s) was a late 14th century knight, diplomat, and itinerant fencing master. He was born in Cividale del Friuli, a town in the Patriarchal State of Aquileia (in the Friuli region of modern-day Italy), the son of Benedetto and scion of a Liberi house of Premariacco. The term Liberi, while potentially merely a surname, more probably indicates that his family had Imperial immediacy (Reichsunmittelbarkeit), either as part of the nobili liberi (Edelfrei, "free nobles"), the Germanic unindentured knightly class which formed the lower tier of nobility in the Middle Ages, or possibly of the rising class of Imperial Free Knights. It has been suggested by various historians that Fiore and Benedetto were descended from Cristallo dei Liberi of Premariacco, who was granted immediacy in 1110 by Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich V, but this has yet to be proven.

Fiore wrote that he had a natural inclination to the martial arts and began training at a young age, ultimately studying with “countless” masters from both Italic and Germanic lands. He had ample opportunity to interact with both, being born in the Holy Roman Empire and later traveling widely in the northern Italian states. Unfortunately, not all of these encounters were friendly: Fiore wrote of meeting many “false” or unworthy masters in his travels, most of whom lacked even the limited skill he'd expect in a good student. He further mentions that on five separate occasions he was forced to fight duels for his honor against certain of these masters who he described as envious because he refused to teach them his art; the duels were all fought with sharp swords, unarmored except for gambesons and chamois gloves, and he won each without injury.

Writing very little on his own career as a commander and master at arms, Fiore laid out his credentials for his readers in other ways. He stated that foremost among the masters who trained him was one Johane dicto Suueno, who he notes was a disciple of Nicholai de Toblem; unfortunately, both names are given in Latin so there is little we can conclude about them other than that they were probably among the Italians and Germans he alludes to, and that one or both were well known in Fiore's time. He further offered an extensive list of the famous condottieri that he trained, including Piero Paolo del Verde (Peter von Grünen), Niccolo Unricilino (Nikolo von Urslingen), Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli (Galeazzo Gonzaga da Mantova), Lancillotto Beccaria di Pavia, Giovannino da Baggio di Milano, and Azzone di Castelbarco, and also highlights some of their martial exploits.

The only known historical mentions of Fiore appear in connection with the Aquileian War of Succession, which erupted in 1381 as a coalition of secular nobles from Udine and surrounding cities sought to remove the newly appointed Patriarch (prince-bishop of Aquileia), Philippe II d'Alençon. Fiore seems to have supported the secular nobility against the Cardinal; he traveled to Udine in 1383 and was granted residency in the city on 3 August. On 30 September, the high council tasked him with inspection and maintenance of city's weapons, including the artillery pieces defending Udine (large crossbows and catapults). In February of 1384, he was assigned the task of recruiting a mercenary company to augment Udine's forces and leading them back to the city. This task seems to have been accomplished in three months or less, as on 23 May he appeared before the high council again and was sworn in as a sort of magistrate charged with keeping the peace in one of the city's districts. After May 1384, the historical record is silent on Fiore's activities; the war continued until a new Patriarch was appointed in 1389 and a peace settlement was reached, but it's unclear if Fiore remained involved for the duration. Given that he appears in council records four times in 1383-4, it would be quite odd for him to be completely unmentioned over the subsequent five years if he remained, and since his absence from records coincides with a proclamation in July of that year demanding that Udine cease hostilities or face harsh repercussions, it seems more likely that he moved on.

Based on his autobiographical account, Fiore traveled a good deal in northern Italy, teaching fencing and training men for duels. He seems to have been in Perugia in 1381 in this capacity, when his student Peter von Grünen likely fought a duel with Peter Kornwald. In 1395, he can be placed in Padua training the mercenary captain Galeazzo Gonzaga of Mantua for a duel with the French marshal Jean II le Maingre (who went by the war name “Boucicaut”). Galeazzo made the challenge when Boucicaut called into question the valor of Italians at the royal court of France, and the duel was ultimately set for Padua on 15 August. Both Francesco Novello da Carrara, Lord of Padua, and Francesco Gonzaga, Lord of Mantua, were in attendance. The duel was to begin with spears on horseback, but Boucicaut became impatient and dismounted, attacking Galeazzo before he could mount his own horse. Galeazzo landed a solid blow on the Frenchman’s helmet, but was subsequently disarmed. At this point, Boucicaut called for his poleaxe but the lords intervened to end the duel.

Fiore surfaces again in Pavia in 1399, this time training Giovannino da Baggio for a duel with a German squire named Sirano. It was fought on 24 June and attended by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, as well as the Duchess and other nobles. The duel was to consist of three bouts of mounted lance followed by three bouts each of dismounted poleaxe, estoc, and dagger. They ultimately rode two additional passes and on the fifth, Baggio impaled Sirano’s horse through the chest, slaying the horse but losing his lance in the process. They fought the other nine bouts as scheduled, and due to the strength of their armor (and the fact that all of the weapons were blunted), both combatants reportedly emerged from these exchanges unharmed.

Fiore was likely involved in at least one other duel that year, that of his final student Azzone di Castelbarco and Giovanni degli Ordelaffi, as the latter is known to have died in 1399. After Castelbarco’s duel, Fiore’s activities are unclear. Based on the allegiances of the nobles that he trained in the 1390s, he seems to have been associated with the ducal court of Milan in the latter part of his career. Some time in the first years of the 1400s, Fiore composed a fencing treatise in Italian and Latin called "The Flower of Battle" (rendered variously as Fior di Battaglia, Florius de Arte Luctandi, and Flos Duellatorum). The briefest version of the text is dated to 1409 and indicates that it was a labor of six months and great personal effort; as evidence suggests that at least two longer versions were composed some time before this, we may assume that he devoted a considerable amount of time to writing during this decade.

Beyond this, nothing certain is known of Fiore's activities in the 15th century. Francesco Novati and D. Luigi Zanutto both assume that some time before 1409 he accepted an appointment as court fencing master to Niccolò III d’Este, Marquis of Ferrara, Modena, and Parma; presumably he would have made this change when Milan fell into disarray in 1402, though Zanutto went so far as to speculate that he trained Niccolò for his 1399 passage at arms. However, while the records of the d’Este library indicate the presence of two versions of "the Flower of Battle", it seems more likely that the manuscripts were written as a diplomatic gift to Ferrara from Milan when they made peace in 1404. C. A. Blengini di Torricella stated that late in life he made his way to Paris, France, where he could be placed teaching fencing in 1418 and creating a copy of a fencing manual located there in 1420. Though he attributes these facts to Novati, no publication verifying them has yet been located and this anecdote may be entirely spurious. The time and place of Fiore's death remain unknown.

Despite the depth and complexity of his writings, Fiore de’i Liberi does not seem to have been a very significant master in the evolution of fencing in Central Europe. That field was instead dominated by the traditions of 14th century master Johannes Liechtenauer in the Holy Roman Empire and of Fiore's near-contemporary Filippo di Bartolomeo Dardi in Italy. Even so, there are a number of later treatises which bear strong resemblance to his work, including the writings of Philippo di Vadi and Ludwig VI von Eyb. This may be due to the direct influence of Fiore or his writings, or it may instead indicate that the older tradition of Johane and Nicholai survived and spread outside of Fiore's direct line.

(Read more...)

- Recently Featured:

- Sigmund Schining ain Ringeck – Joachim Meÿer – Paulus Hector Mair – Die Blume des Kampfes