|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Philippo di Vadi"

| Line 617: | Line 617: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter V Of Thrusts and Cuts}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>The sword has a point and two edges, | + | <p>The sword has a point and two edges,<br/> |

| − | But note well and understand this text, | + | But note well and understand this text,<br/> |

| − | That memory will not | + | That memory will not bamboozle you:</p> |

| − | <p>One is the false, and the other the true, | + | <p>One [edge] is the false, and the other the true,<br/> |

| − | And reason commands and desires | + | And reason commands and desires<br/> |

| − | That this | + | That you keep this fixed in your brain.</p> |

| − | <p>Forehand and true edge go together, | + | <p>Forehand and true edge go together,<br/> |

| − | Backhand and false edge stay together, | + | Backhand and false edge stay together,<br/> |

| − | Except the fendente which | + | Except the fendente which calls for the true.</p> |

| − | <p>Understand my text well, | + | <p>Understand my text well,<br/> |

| − | + | Seven are the blows that the sword delivers<br/> | |

| − | + | That would be six cuts, with the thrust.</p> | |

| − | <p> | + | <p>SSo that you will find this vein,<br/> |

| − | Two from above and below and two in the middle, | + | Two from above and below and two in the middle,<br/> |

| − | The thrust up the middle with deceit and | + | The thrust up the middle with deceit and pain,<br/> |

| − | That our | + | That often gets us out of trouble.<ref>''Che l’aer nostro fa spesso serena'', lit. “that often makes our skies serene”.</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:Cod.1324 09r.jpg|9r.2}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 09r.jpg|9r.2}} | ||

| Line 656: | Line 656: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter VI. The seven blows of the sword.}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>We are the fendenti and we make quarrels, | + | <p>We are the ''fendenti'' and we make quarrels,<br/> |

| − | To strike and cut often with | + | To strike and cut often, with pain,<br/> |

| − | The head and the teeth | + | The head and the teeth in a direct way.</p> |

| − | <p>And all guards that are made low to the ground, | + | <p>And all guards that are made low to the ground,<br/> |

| − | We break often with our cunning, | + | We break often with our cunning,<br/> |

Passing from one to the other without trouble.</p> | Passing from one to the other without trouble.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The blows make a bloody mark, | + | <p>The blows make a bloody mark,<br/> |

| − | When we mix them with the rota | + | When we mix them with the rota<br/> |

| − | We | + | We make the entire Art our support.</p> |

| − | <p>Fendente for striking we are well endowed, | + | <p>''Fendente'', for striking we are well endowed,<br/> |

| − | Returning to guard from pass to pass, | + | Returning to guard from pass to pass,<br/> |

| − | Note we are not slow to strike.</p> | + | Note: we are not slow to strike.</p> |

| − | <p>I am the rota and I have in me such a load, | + | <p>I am the ''rota'' and I have in me such a load,<br/> |

| − | + | If you want to mix me with the other blows,<br/> | |

| − | I place a thrust | + | I will often place a thrust in an arc.<ref>This line reads “''io metterò la punta spesso a l’archo''”. “I will place the thrust” is clear. ''Spesso a l’archo'' is literally “often at a bow”. But just as ''bistecca alla fiorentina'' is steak in the manner of Florence, so ''a l’archo'' can be read as “in the manner of an arc”, or possibly “in the manner of a bow”. I will discuss this further in the commentary.</ref></p> |

| − | <p>I cannot be courteous or loyal | + | <p>I cannot be courteous or loyal,<br/> |

| − | Turning I pass through forehand fendente | + | Turning I pass through the forehand fendente<br/> |

And destroy arms and hands without delay.</p> | And destroy arms and hands without delay.</p> | ||

| − | <p>People call me | + | <p>People call me ''rota'' by name,<br/> |

| − | I seek the | + | I seek the deception of the sword<br/> |

| − | I | + | I hone the mind of he who uses me.</p> |

| − | <p>We are volanti, always crossing | + | <p>We are ''volanti'', always crossing<br/> |

| − | And from the knee up | + | And striking from the knee up,<br/> |

Fendente and thrusts we often banish.</p> | Fendente and thrusts we often banish.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>The ''rota'' that come up from below<br/> |

| − | The | + | Pass us obliquely without fail<br/> |

| − | And with the fendente | + | And with the ''fendente'' warm the cheeks.<ref>This means the ''fendente'' strike us. In this last stanza, ''rota'' blows are defeating ''volante'' blows; they are parrying them and returning with a fendente to the face.</ref></p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Cod.1324 09r.jpg|9r.3|p=1}}<br/>{{section|Page:Cod.1324 09v.jpg|9v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 09r.jpg|9r.3|p=1}}<br/>{{section|Page:Cod.1324 09v.jpg|9v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 711: | Line 711: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter VII. Of the thrust}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>I am | + | <p>I am she that quarrels with<br/> |

| − | All the other blows, and I am called the thrust. | + | All the other blows, and I am called the thrust.<br/> |

I carry venom like the scorpion.</p> | I carry venom like the scorpion.</p> | ||

| − | <p>I feel so strong, bold and | + | <p>I feel so strong, bold and ready,<br/> |

| − | Often I make the guards | + | Often I make the guards waver<br/> |

| − | When I am thrown at others and confront them</p> | + | When I am thrown at others and confront them,</p> |

| − | + | <p>And when I am joined, I harm nobody with my touch.</p> | |

| {{section|Page:Cod.1324 09v.jpg|9v.2}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 09v.jpg|9v.2}} | ||

| Line 739: | Line 739: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter VIII. The dispute of the cuts and thrusts}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>The rota with the fendente and the volante | + | <p>The ''rota'' with the ''fendente'' and the ''volante''<br/> |

| − | + | Argue with the thrusts and show them<br/> | |

| − | That | + | That they are not so dangerous.</p> |

| − | <p>And when they come to us, | + | <p>And when they come to us,<br/> |

| − | All the blows can make them lose their way | + | All the blows can make them lose their way<br/> |

Losing in this joust the chance to strike.</p> | Losing in this joust the chance to strike.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The blow of the sword does not lose its turn, | + | <p>The blow of the sword does not lose its turn,<br/> |

| − | + | The thrust is worth little against he who turns quickly<br/> | |

| − | + | The blows clear the way for the one who is going.<ref>As I understand it, this means that the quick turn of the cut beats the thrust out of the way, ‘making room’ for you.</ref></p> | |

| − | <p>If you don’t have a | + | <p>If you don’t have a quick memory,<br/> |

| − | If the thrust doesn’t | + | If the thrust doesn’t wound it loses its turn,<br/> |

| − | All the | + | All the other [blows] deem it weak.</p> |

| − | <p>Against just one the thrust finds its place, | + | <p>Against just one [opponent] the thrust finds its place,<br/> |

| − | Against more it doesn’t do its duty, | + | Against more it doesn’t do its duty,<br/> |

| − | This is found in the text and the act.</p> | + | This is found in the text and the act.<ref>That is, in theory and in practice.</ref></p> |

| − | <p>If the thrust throws a rota do not fear | + | <p>If the thrust throws a ''rota'' do not fear,<br/> |

| − | If it does not immediately take a good fendente, | + | If it does not immediately take a good ''fendente'',<br/> |

| − | It remains fruitless | + | It remains fruitless, it seems to me. </p> |

| − | <p>Keep in mind here, | + | <p>Keep in mind a little here,<br/> |

| − | If the thrust enters but does not swiftly exit, | + | If the thrust enters but does not swiftly exit,<br/> |

| − | It lets the companion strike | + | It lets the companion hurt you with a strike.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Cutting a blow, your sword is lost,<br/> |

| − | + | If the point loses its way in the strike,<br/> | |

| − | + | Or the right cross from below helps you.<ref> I read this to mean that when cutting, your point should remain in line (in the ''strada''), unless you deliberately allow it to fall, to parry up from below.</ref></p> | |

| − | <p>I make a | + | <p>I make a forehand ''fendente'' at you with the sword,<br/> |

| − | And break you out of that guard | + | And break you out of that guard,<br/> |

So that you are forced into a bad spot.</p> | So that you are forced into a bad spot.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Do not lose | + | <p>Do not lose even an hour of learning:<br/> |

| − | The great | + | The great motions with a serene hand,<ref>''Tempi'' here is clearly ‘motions’, rather than ‘times’.</ref><br/> |

Will place you above the others and give you honour.</p> | Will place you above the others and give you honour.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Break all low guards | + | <p>Break all low guards,<br/> |

| − | Low guards await small loads, | + | Low guards await small loads,<br/> |

And so heavy ones pass without difficulty.</p> | And so heavy ones pass without difficulty.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>A heavy weapon does not pass quickly to the step,<br/> |

| − | Light ones go | + | Light ones come and go like an arrow from a bow.</p> |

| <p>{{paget|Page:Cod.1324|10r|jpg|p=1}}<br/>{{section|Page:Cod.1324 10v.jpg|10v.1|p=1}}</p> | | <p>{{paget|Page:Cod.1324|10r|jpg|p=1}}<br/>{{section|Page:Cod.1324 10v.jpg|10v.1|p=1}}</p> | ||

| Line 804: | Line 804: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter IX. Of the Cross}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>I am the Cross with the name of Jesus | + | <p>I am the Cross with the name of Jesus<br/> |

| − | My sign is made both in front and behind | + | My sign is made both in front and behind<br/> |

To find many more defences.</p> | To find many more defences.</p> | ||

| − | <p>If I | + | <p>If I confront a different weapon,<br/> |

| − | I do not lose my way, | + | I do not lose my way, I have been proven;<br/> |

| − | This I | + | This often happens because I go looking for it.</p> |

| − | <p>And when | + | <p>And when a long weapon finds me,<ref>This line is ambiguous; it could also read “And when a weapon finds me extended”.</ref><br/> |

| − | + | He who with reason makes my defence,<br/> | |

| − | + | Will gain the honour in every venture.<ref>The word Vadi uses here is ‘''inprexa''’. It is the same word as the French ‘''emprise''’, which was commonly used in the fifteenth century to denote a feat of arms in which a knight travelled from place to place, fighting other knights in the lists, to gain renown. It was also commonly used to denote a military campaign.</ref></p> | |

| {{section|Page:Cod.1324 10v.jpg|10v.2}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 10v.jpg|10v.2}} | ||

| Line 834: | Line 834: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter X. Theory of the half sword}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>Wanting to follow in this great work, | + | <p>Wanting to follow in this great work,<br/> |

| − | It is necessary to explain bit by bit, | + | It is necessary to explain bit by bit,<br/> |

All the strikes of the art.</p> | All the strikes of the art.</p> | ||

| − | <p>So that | + | <p>So that it is well understood and put into practice,<ref>This is the point at which terza rima gives way to rhyming couplets. At this stage in the manuscript, the division of the text is not simple. This chapter begins with terza rima, then shifts into couplets, which are not in sync with the quatrains denoted by coloured capitals. The capitals seem to divide the text by sense: one on the stramazzone; one on the roverso, and so on. The reader should be aware that this does not accord with the rhyme scheme.</ref><br/> |

| − | The | + | Reason demands that I first explain<br/> |

The turning principle of the sword.</p> | The turning principle of the sword.</p> | ||

| − | <p>And with arms extended | + | <p>And with arms extended go,<ref> At this point there ''menando'', (“bringing”) is written vertically as a catchword (the first word on the first sheet of the next quire, an aid to the bookbinder).</ref><br/> |

| − | + | Driving the edge to the middle of the companion.</p> | |

| − | <p>And if you wish to appear great in the art, | + | <p>And if you wish to appear great in the art,<br/> |

| − | You | + | You can go from guard to guard,<br/> |

| − | With a slow and serene hand, | + | With a slow and serene hand,<ref>A slow and serene hand: this is one of the more counter-intuitive instructions; why would you want slow, calm motions in a sword fight? In practice, smooth, calm motions are the hallmark of a master.</ref><br/> |

With steps that are not out of the ordinary.</p> | With steps that are not out of the ordinary.</p> | ||

| − | <p>If you wish to make a | + | <p>If you wish to make some kind of ''stramazone'',<ref>This is the first appearance of stramazone in this text, and I believe in all fencing literature, and it’s described in the line that follows in similar terms to subsequent authors, such as Capoferro: “The ''stramazzone'' is a wheel-like cut delivered from the wrist.” (Leoni 2011, 27.)</ref><br/> |

| − | Do it with a small turn | + | Do it with a small turn in front of the face,<br/> |

| − | Don’t make a very wide | + | Don’t make a very wide motion,<br/> |

| − | Because all | + | Because all wide motions<ref>''Largo tempo'', literally “wide time”; another case in which ‘tempo’ is clearly used to mean a movement. ‘Largo’ here is wide or broad.</ref> are for nothing.</p> |

| − | <p>Making the roverso you will be helped, | + | <p>Making the ''roverso'' you will be helped,<br/> |

| − | Passing out of the way with the left foot, | + | Passing out of the way with the left foot,<br/> |

| − | + | Drawing forwards with the right foot too,<br/> | |

Keeping an eye out for a good parry.</p> | Keeping an eye out for a good parry.</p> | ||

| − | <p>When you wish to enter | + | <p>When you wish to enter into half sword<br/> |

| − | As the companion lifts his sword, | + | As the companion lifts his sword,<br/> |

| − | Then don’t hold back, | + | Then don’t hold back,<br/> |

| − | Grab the tempo or it will cost you dear.</p> | + | Grab the tempo<ref>Tempo here is clearly used in the sense of “opportunity to strike”. “Seize the time” might also work as a translation.</ref> or it will cost you dear.</p> |

| − | <p>Place yourself in the guard of the boar, | + | <p>Place yourself in the guard of the boar,<br/> |

| − | When you enter with the thrust at the face | + | When you enter with the thrust at the face<br/> |

| − | Do not | + | Do not be divided at all [from the companion],<ref>''punto divixo'': lit. “point divided”. Rodolfo Tanara pointed out (in private correspondence 5 February 2017) that “in Tuscany [it] is a regionalism to say ''poco e punto'' to say “a few and not at all”. So ''punto'' could be intended as ''affatto'' that is “not at all”; since Philippo Vadi was from Pisa, he could actually have intended that meaning. So in this phrase, the general advice he gives us is to stay close to the companion, “not divided at all”, obviously this favours half-sword measure.”</ref><br/> |

| − | Turn quickly a roverso fendente.</p> | + | Turn quickly a ''roverso fendente''.</p> |

| − | <p>And | + | <p>And strike a ''dritto''. Keep this in mind,<br/> |

| − | So that you understand my intention, | + | So that you understand my intention,<br/> |

| − | With clear reasoning, | + | With clear reasoning,<br/> |

| − | I hope to show you the way.</p> | + | I hope to thoroughly show you the way.</p> |

| − | <p>I don’t want your blows to be solely roverso, | + | <p>I don’t want your blows to be solely ''roverso'',<br/> |

| − | Nor just fendente, but between one and the other, | + | Nor just ''fendente'', but between one and the other,<br/> |

| − | + | Both between the common one,<ref>This is indicating a vertical downwards blow.</ref><br/> | |

Hammering the head on all sides.</p> | Hammering the head on all sides.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Also I advise you when you have entered, | + | <p>Also I advise you when you have entered,<br/> |

| − | Be with the legs | + | Be with the legs not too far apart,<br/> |

| − | You will be lord, and clear | + | You will be the lord, and clear<br/> |

To constrain and strike valiantly.</p> | To constrain and strike valiantly.</p> | ||

| − | <p>And when you strike a roverso fendente, | + | <p>And when you strike a ''roverso fendente'',<br/> |

| − | Bend the left knee, and note the text, | + | Bend the left knee, and note the text,<br/> |

| − | Extend the right foot, | + | Extend the right foot,<br/> |

| − | Without changing it, i.e. to | + | Without changing it, i.e. to either side.</p> |

| − | <p>Also, | + | <p>Also, the left foot and the head are understood<br/> |

| − | + | To be connected now,<br/> | |

| − | Because | + | Because the head is closer to the left foot,<ref>This line actually reads “Because it is closer to it”; I have expanded on it for clarity.</ref><br/> |

| − | + | Than to the right one, that remains sideways.</p> | |

| − | <p>So you will be safe from every side, | + | <p>So you will be safe from every side,<br/> |

| − | + | If you want to strike a forehand fendente,<br/> | |

| − | You need to bend | + | You need to bend<ref>There appears to be a correction to the text: ''pigliare'' (to grab) has been modified to ''pighare'' (to bend). Rubboli has it as the former. (51)</ref><br/> |

The right knee: and extend well the left.</p> | The right knee: and extend well the left.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>You will consider that the head is now connected,<br/> |

| − | + | To the right foot that is closest.<br/> | |

| − | This is | + | This is a better way<br/> |

| − | + | Than the footwork of our ancestors.<ref> This detailed explanation of mechanics, with the head being “connected” (''atacata'') to the weighted foot (the one with the bent knee) is unprecedented in fencing literature.</ref></p> | |

| − | <p>It is | + | <p>It is necessary that no one contradicts this,<br/> |

| − | Because you will be stronger, and more secure, | + | Because you will be stronger, and more secure,<br/> |

| − | Hard in defence, | + | Hard in defence,<br/> |

| − | And make war with | + | And make war with the shortest motion,<br/> |

| − | And neither can anyone | + | And neither can anyone make you fall.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Cod.1324 10v.jpg|10v.3|p=1}}<br/>{{paget|Page:Cod.1324|11r|jpg|p=1}}<br/>{{paget|Page:Cod.1324|11v|jpg|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 10v.jpg|10v.3|p=1}}<br/>{{paget|Page:Cod.1324|11r|jpg|p=1}}<br/>{{paget|Page:Cod.1324|11v|jpg|p=1}} | ||

| Line 930: | Line 930: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter XI. Theory of swordplay}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>When you | + | <p>When you have arrived at the half sword,<br/> |

| − | + | Making a ''mandritto'' or ''roverso'',<br/> | |

| − | Be sure to grasp the sense | + | Be sure to grasp the sense<br/> |

Of what I say, because it is to the point.</p> | Of what I say, because it is to the point.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>When you feint keep a sharp eye out,<ref>The word used is ‘visteggi’; in the next chapter, “Ragion de viste di spada”, he uses it again. From the context, he is clearly using the word to mean ‘feint’. The only other place I have encountered this word with the same meaning is in Giganti, Nicoletto, p.23 – in the chapter heading: ''Della finta dichiaratione'' (“Explanation of the feints”), which is subtitled ''Far vista di cavar la Spada con il nodo della mano''. (“Make a feint of disengaging the sword with the wrist.”)</ref><br/> |

| − | And | + | And make the feint short, with the cover,<br/> |

| − | And hold the sword up, | + | And hold the sword up,<br/> |

So your arms play above your head.</p> | So your arms play above your head.</p> | ||

| − | <p>I cannot say in a few words, | + | <p>I cannot say in a few words,<br/> |

| − | Because the | + | Because the actions are of the half sword,<br/> |

| − | + | Where you go as you please.<ref>The sense here is that there are so many possible actions to be done from here that it is impossible to list them all.</ref><br/> | |

| − | When you parry, parry with a fendente.</p> | + | When you parry, parry with a ''fendente''.</p> |

| − | <p>Brush aside the sword, a little | + | <p>Brush aside the sword, a little away from you, cautiously,<br/> |

| − | + | Pressing that of the companion,<br/> | |

| − | You will make a good deal, | + | You will make a good deal,<br/> |

| − | Parrying well | + | Parrying well whichever blows.</p> |

| − | <p>When you parry the roverso | + | <p>When you parry the ''roverso'' do so with<br/> |

| − | The right foot, and parry as I have said. | + | The right foot forwards, and parry as I have said.<br/> |

| − | Parrying the mandritto, | + | Parrying the ''mandritto'',<br/> |

| − | + | Put your left foot forwards instead.</p> | |

| − | <p>You should also keep in mind, | + | <p>You should also keep in mind,<br/> |

| − | When you strike a roverso fendente, | + | When you strike a ''roverso fendente'',<br/> |

| − | To keep a careful eye out, | + | To keep a careful eye out,<br/> |

| − | So that a mandritto doesn’t come from underneath.</p> | + | So that a ''mandritto'' doesn’t come from underneath.</p> |

| − | <p>And if the companion strikes and you all of a sudden | + | <p>And if the companion strikes, and you all of a sudden<br/> |

| − | Parry, making then to the head | + | Parry, making then to the head<br/> |

| − | A blow with the false edge | + | A blow with the false edge carefully,<br/> |

| − | And as he lifts it, strike a good roverso | + | And as he lifts it,<ref>“It” in this case refers to his sword: the opponent is parrying your feint of a false edge blow. Avoid the parry and strike a ''roverso'' from below.</ref> strike a good ''roverso''</p> |

| − | <p>From below, | + | <p>From below, across his arms,<br/> |

| − | Redoubling then with a quick mandritto, | + | Redoubling then with a quick ''mandritto'',<br/> |

| − | And note also this, | + | And note also this,<br/> |

| − | That you do not fail the | + | That you do not fail the principles of the Art.</p> |

| − | <p>If you strike a mandritto, then beware, | + | <p>If you strike a ''mandritto'', then beware,<br/> |

| − | + | The ''roverso'' that he might strike.<br/> | |

| − | Make it that your sword | + | Make it so that your sword also<br/> |

| − | Parries with a fendente, so you are not | + | Parries with a ''fendente'', so that you are not hit.</p> |

| − | <p>And if it comes to you then to want | + | <p>And if it comes to you then to want<br/> |

| − | To enter underneath and grab his handle | + | To enter underneath and grab his handle,<br/> |

| − | And then do your duty, | + | And then do your duty,<br/> |

| − | Hammering his moustache with your pommel, | + | Hammering his moustache with your pommel,<ref>''Mustaccio'' is a slang word for face (Italian for moustache is baffo), but I hope the reader will forgive me taking advantage of a false friend to create a more memorable image.</ref><br/> |

| − | + | Watching out that you do not get stuck.</p> | |

| | | | ||

{{paget|Page:Cod.1324|12r|jpg|p=1}}<br/>{{section|Page:Cod.1324 12v.jpg|12v.1|p=1}} | {{paget|Page:Cod.1324|12r|jpg|p=1}}<br/>{{section|Page:Cod.1324 12v.jpg|12v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,000: | Line 1,000: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter XII. Theory of the feints of the sword}}</p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <p>You then well from every side | + | <p>Again I advise you, and note my words well,<br/> |

| + | That when you have entered into half sword<br/> | ||

| + | You then [act] well from every side,<br/> | ||

Following the art with good feinting.</p> | Following the art with good feinting.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Feints | + | <p>Feints are considered an obfuscation,<br/> |

| − | They | + | They confound the opponent in the defence.<br/> |

| − | + | They do not let him understand,<br/> | |

| − | What you want to do | + | What you want to do on one side or the other.</p> |

| − | <p>I cannot show you so well | + | <p>I cannot show you so well<br/> |

| − | With my words | + | With my words, as I could with a sword.<br/> |

| − | Make your mind go | + | Make your mind go<br/> |

| − | To investigate the art with my sayings | + | To investigate the art with my sayings,</p> |

| − | <p>And grasp valour with reason | + | <p>And grasp valour with reason,<br/> |

| − | As I admonish and as I teach you | + | As I admonish and as I teach you.<br/> |

| − | And | + | And make it so that with cunning<br/> |

| − | You follow that which I | + | You will follow that which I write in so many verses,<br/> |

To discover the depths and the banks of the Art.</p> | To discover the depths and the banks of the Art.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,043: | Line 1,042: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter XIII. Theory of the half sword}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Having then arrived at the half sword,<br/> |

| − | You can well hammer more and more times, | + | You can well hammer more and more times,<br/> |

| − | Striking on only one side, | + | Striking on only one side,<br/> |

Your feints go on the other side.</p> | Your feints go on the other side.</p> | ||

| − | <p>And when he loses his way with parrying, | + | <p>And when he loses his way with parrying,<br/> |

| − | And you hammer then on the other side, | + | And you hammer then on the other side,<br/> |

| − | Then you | + | Then you decide<br/> |

| − | + | Which ''stretta'' you should finish with.</p> | |

| − | <p>And if you want to throw blows, | + | <p>And if you want to throw blows,<br/> |

| − | Let a fendente roverso go, | + | Let a ''fendente roverso'' go,<br/> |

| − | < | + | Turning a cross-wise<ref>The line “''voltandoli atraverso''” is inserted in the margin.</ref> false edge blow<br/> |

| + | With the point in his face.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Do not be divided from | + | <p>Do not be divided from him,<br/> |

| − | With roverso or mandritto | + | With ''roverso'' or ''mandritto''<br/> |

| − | With whichever you can work | + | With whichever you can work,<br/> |

| − | + | As long as the knees bend on every side.</p> | |

| − | <p>Following that which I showed you above, | + | <p>Following that which I showed you above,<br/> |

I repeat for you again this addition,</p> | I repeat for you again this addition,</p> | ||

| − | <p>Always enter with the point, | + | <p>Always enter with the point,<br/> |

| − | + | Upwards from below, until you have skewered the face,<br/> | |

| − | + | Use your strikes in their appropriate times.</p> | |

| {{section|Page:Cod.1324 13r.jpg|13r.2}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 13r.jpg|13r.2}} | ||

| Line 1,087: | Line 1,087: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter XIIII. Theory of the half tempo of the sword}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>I cannot show you in writing | + | <p>I cannot show you in writing<br/> |

| − | The theory and | + | The theory and way of the half tempo<br/> |

| − | Because | + | Because the shortness of the tempo and its strike<br/> |

| − | + | Reside in the wrist.</p> | |

| − | <p>The half | + | <p>The half tempo is just one turn<br/> |

| − | Of the | + | Of the wrist: quick and immediately striking,<br/> |

| − | It can rarely fail | + | It can rarely fail<br/> |

When it is done in good measure.</p> | When it is done in good measure.</p> | ||

| − | <p>If you note well my | + | <p>If you note well my text,<br/> |

| − | One who does not practice will | + | One who does not practice [the art] will get into trouble:<ref>Porzio and Mele (81) read this line as ''mal separa chi non na la praticha'', or “he who lacks practice does not divide well”. Rubboli and Cesari (57) also transcribe ''separa'' as one word. I read it as ''mal se para'', or “will get into trouble”, which seems to me to fit the context better.</ref><br/> |

| − | Often the | + | Often the quick flight from one side to another<br/> |

Breaks with a good edge the other’s brain.</p> | Breaks with a good edge the other’s brain.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Of all the art this is the jewel, | + | <p>Of all the art this is the jewel,<br/> |

| − | Because it | + | Because in one go it strikes and parries.<br/> |

| − | Oh what a valuable thing, | + | Oh what a valuable thing,<br/> |

| − | + | To practice it according to the good principles,<br/> | |

| − | + | It will let you carry the banner of the Art.<ref>Vadi uses the term ‘gonfalone’, which brings to mind the highest military honour the Pope could bestow (recalling that Urbino was one of the Papal states), that of ''gonfaloniere'', “standard bearer”, an equivalent rank perhaps to Marshal of France in that there was only ever one ''gonfaloniere'' at a time. Guidobaldo’s father Federico was ''gonfaloniere'' from 1462 to 1468 under Pope Pius II, and again from 1474 to 1482 under Sixtus IV. Guidobaldo did indeed make it to that rank like his father before him, from 1504 until his death in 1508, under Julius II. (This has been called into question by Clough.) It’s hard to imagine that Vadi would have been unaware of the reference, and he probably meant this to encourage the young Duke to reach the heights that his father had.</ref></p> | |

| {{section|Page:Cod.1324 13v.jpg|13v.1}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 13v.jpg|13v.1}} | ||

| Line 1,126: | Line 1,126: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter XV. Theory of the sword against the rising blow}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>There are many who make their base | + | <p>There are many who make their base<br/> |

| − | In turning strongly from every side | + | In turning strongly from every side<br/> |

| − | So be advised, | + | So be advised,<br/> |

| − | As his sword | + | As his sword is turning, move,</p> |

| − | <p>And you turn and you will win the test, | + | <p>And you turn and you will win the test,<br/> |

| − | + | Then harmonise yourself with his strikes,<br/> | |

| − | And make your going thus | + | And make your going thus<br/> |

| − | With your sword | + | With your sword behind his.</p> |

| − | <p>To | + | <p>To better explain your design,<br/> |

| − | You can also go into boar’s tooth guard, | + | You can also go into boar’s tooth guard,<br/> |

| − | And if he with the turning, | + | And if he with the turning,<br/> |

| − | And you | + | And you ripping up from below.<ref>The verb used here is ‘scharpando’, the gerund form of the vulgar scharpare, from Latin discerpere – Italian dilaniare. It means to tear apart, rip apart, to shred. (Rodolfo Tanara, private correspondence, 3 February 2017.) Incidentally, by ripping up from below, you beat aside the opponent’s sword and your blade does end up behind theirs, as recommended in the previous quatrain.</ref></p> |

| − | <p>Listen and understand my reasoning, | + | <p>Listen and understand my reasoning,<br/> |

| − | You who are new to the art, and experts too, | + | You who are new to the art, and experts too,<br/> |

| − | I want you to be sure, | + | I want you to be sure,<br/> |

That this is the art and the true science.</p> | That this is the art and the true science.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Grasp this, that is a steelyard’s trace, | + | <p>Grasp this, that is a steelyard’s trace:<ref>This line reads “Piglia questo, che un tracto di stadera”. A steelyard is a weighing scale, with arms of unequal length. It is hung from a hook, with the item to be weighed hung from the short arm, and the counterweight hung from the longer arm, and slid along until the scale balances. The position of the counterweight on the longer arm tells you the weight of the item. ‘Tracto’ here probably refers to the gradations on the steelyard. The image is perhaps one of rapid movement, a passing instant. I am indebted to Rodolfo Tanara who suggested this reading. Personal conversation, 3 February 2017.</ref><br/> |

| − | + | The companion is in the iron door guard,<br/> | |

| − | Lock this into your heart, | + | Lock this into your heart,<br/> |

| − | + | Make it so you are in the archer’s guard,</p> | |

| − | <p>Watch out that your point does not waver, | + | <p>Watch out that your point does not waver,<br/> |

| − | + | And covers the companion’s sword;<br/> | |

| − | Go a little out of the way | + | Go a little out of the way<br/> |

Straightening the sword and the hand with the point.</p> | Straightening the sword and the hand with the point.</p> | ||

| − | <p>When your sword is joined at the crossing, | + | <p>When your sword is joined at the crossing,<br/> |

| − | Then do the thirteenth | + | Then do the thirteenth stretta,<br/> |

| − | As is you can plainly see | + | As is you can plainly see<br/> |

| − | Pictured in our book of | + | Pictured in our book on page seven.<ref> This is a very specific reference, but one that makes no sense. The thirteenth play of the sword is on f20v. This would be page 40 of the ms. The seventh page starting from the beginning of the sword section (the page with Vadi’s portrait on, 16r), is 19r. If we count each ‘''carta''’ in the way we count folia, then we get to 22r (counting from 16r), or 21r counting from the beginning of the illustrated section (15r). For the purposes of reconstructing this action, I use the thirteenth play of the sword, and disregard the page reference.</ref></p> |

| − | <p>You can also use in this art | + | <p>You can also use in this art<br/> |

| − | + | Strikes and strette that are handier to you,<br/> | |

| − | Leave the more | + | Leave the more clumsy,<ref>''Sinestre'' is literally “left-handed ones”. This is the antonym of ‘dextrous’. Clumsy is the intended meaning.</ref><br/> |

| − | Keep those that favour your hand, | + | Keep those that favour your hand,<br/> |

So you will often have honour in the art.</p> | So you will often have honour in the art.</p> | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 13v.jpg|13v.2}} | + | | |

| − | + | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 13v.jpg|13v.2|p=1}}<br/>{{section|Page:Cod.1324 14r.jpg|14r.1|p=1}} | |

| − | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 14r.jpg|14r.1}} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,187: | Line 1,186: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>{{red|b=1|Chapter XVI Mastering the sword}}</p> |

| − | + | ||

| − | <p>It is necessary that the sword should be | + | <p>It is necessary that the sword should be<br/> |

| − | A great shield that covers all, | + | A great shield that covers all of you,<br/> |

| − | And grasp this fruit, | + | And grasp this fruit,<br/> |

| − | That I give you for your | + | That I give you for your instruction.</p> |

| − | <p>Be sure that your sword | + | <p>Be sure that your sword is never far away<br/> |

| − | + | In making guards or striking<br/> | |

| − | + | Oh how sensible this thing is,<br/> | |

That your sword makes short movements.</p> | That your sword makes short movements.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Make it so your point watches the face<br/> |

| − | Of the companion, in guard or striking, | + | Of the companion, in guard or striking,<br/> |

| − | You will take his courage, | + | You will take away his courage,<br/> |

Seeing always the point staying in front of him.</p> | Seeing always the point staying in front of him.</p> | ||

| − | <p>And you will make your plays always forwards, | + | <p>And you will make your plays always forwards,<br/> |

| − | With your sword and with a small turn, | + | With your sword and with a small turn,<br/> |

| − | With a serene and | + | With a serene and relaxed hand,<br/> |

| − | Often breaking the tempo of the companion, | + | Often breaking the tempo of the companion,<br/> |

| − | You will weave a web | + | You will weave a web better than a spider’s.</p> |

| − | + | <p>'''The End.'''</p> | |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Cod.1324 14r.jpg|14r.2|p=1}}<br/>{{paget|Page:Cod.1324|14v|jpg|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Cod.1324 14r.jpg|14r.2|p=1}}<br/>{{paget|Page:Cod.1324|14v|jpg|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,229: | Line 1,228: | ||

|- | |- | ||

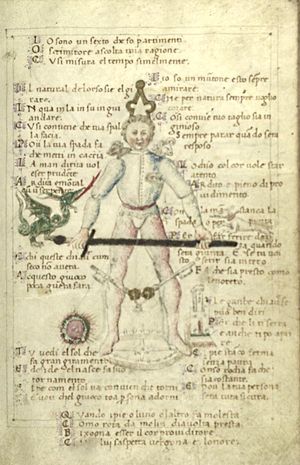

| [[File:Cod.1324 15r.jpg|300px|center|link=http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cod.1324_15r.jpg]] | | [[File:Cod.1324 15r.jpg|300px|center|link=http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cod.1324_15r.jpg]] | ||

| − | | <p>I am callipers, that divide into parts, | + | | <p>I am callipers, that divide into parts,<br/> |

| − | O fencer heed my | + | O fencer heed my principle,<br/> |

| − | Thus measure the tempo similarly.</p> | + | Thus [the callipers] measure the tempo similarly.<ref>This means that the tempo is measured by dividing it into parts.</ref></p> |

| − | <p>The nature of the bear is to turn | + | <p>The nature of the bear is to turn<br/> |

| − | + | Here, there, up and down:<br/> | |

| − | Thus your shoulder should move, | + | Thus your shoulder should move,<br/> |

Sending your sword out to hunt.</p> | Sending your sword out to hunt.</p> | ||

| − | <p>I am a ram, always on the lookout, | + | <p>I am a ram, always on the lookout,<br/> |

| − | Naturally always looking to | + | Naturally always looking to clash,<br/> |

| − | So your cut should be clever, | + | So your cut should be clever,<br/> |

| − | Always parry when | + | Always parry when [your cut] is answered.</p> |

| − | <p>The right hand should be prudent, | + | <p>The right hand should be prudent,<br/> |

Bold and deadly as a serpent.</p> | Bold and deadly as a serpent.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The eye with the heart should be alert, | + | <p>The eye with the heart should be alert,<br/> |

Bold and full of foresight.</p> | Bold and full of foresight.</p> | ||

| − | <p>With the left hand | + | <p>With the left hand I have the sword by the point,<br/> |

| − | + | To strike already when it is joined<br/> | |

| − | And if you want the strike to be complete | + | And if you want the strike to be complete<br/> |

Make it as quick as a greyhound.</p> | Make it as quick as a greyhound.</p> | ||

| − | <p>And he who does not have these keys with him | + | <p>And he who does not have these keys with him<br/> |

| − | Will make little war with this play.</p> | + | Will make little war with this play.<ref>These keys (the Keys of St Peter) appear both on the coin struck for Philippo Vadi, as noted in the introduction, and on the seal of the Duke of Urbino where they symbolise Guidobaldo’s father Federico’s status as Gonfalioniere della Chiesa.</ref></p> |

| − | <p>The legs keys it is well said, | + | <p>The legs [are] keys it is well said,<br/> |

| − | Because you close them and also open them | + | Because you close them and also open them. </p> |

| − | <p>You see the sun, that makes great turns, | + | <p>You see the sun, that makes great turns,<br/> |

| − | And where it is born it returns. | + | And where it is born it returns.<br/> |

| − | The foot with the sun should return together, | + | The foot with the sun should return together,<br/> |

If you want the play to adorn your person.</p> | If you want the play to adorn your person.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Plant the left foot without fear,<br/> |

| − | Make it | + | Make it firm like a castle,<br/> |

And then your body will be completely safe.</p> | And then your body will be completely safe.</p> | ||

| − | <p>When one or other foot bothers you | + | <p>When one or other foot bothers you<br/> |

| − | Turn it quickly like a mill wheel, | + | Turn it quickly like a mill wheel,<br/> |

| − | The heart must be foresightful, | + | The heart must be foresightful,<br/> |

| − | + | For on it depends shame and honour.<ref>This line has some text missing. Rubboli and Cesari render it: “C[he-testo abraso-] luj s’aspetta vergogna e l’onore.”</ref></p> | |

| {{paget|Page:Cod.1324|15r|jpg}} | | {{paget|Page:Cod.1324|15r|jpg}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Cod.1324 15v.jpg|300px|center|link=http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cod.1324_15v.jpg]] | | [[File:Cod.1324 15v.jpg|300px|center|link=http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cod.1324_15v.jpg]] | ||

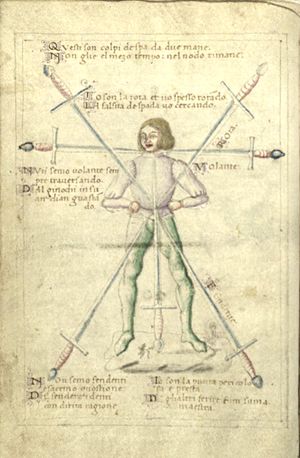

| − | | <p>These are the blows of the two-handed sword, | + | | <p>These are the blows of the two-handed sword,<br/> |

| − | Not | + | Not the ''mezzo tempo'', which remains in the wrist.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p><br/></p> |

| − | |||

| − | <p>We are the volante, always crossing, | + | <p>I am the ''rota'' and I am often turning,<br/> |

| + | I go looking for the deception of the sword.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p><br/></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>We are the ''volante'', always crossing,<br/> | ||

From the knee up we go destroying.</p> | From the knee up we go destroying.</p> | ||

| − | <p>We are the fendenti and we | + | <p><br/></p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>We are the ''fendenti'' and we dispute,<br/> | ||

| + | And we break the teeth with full right.</p> | ||

| − | <p>I am the thrust, dangerous and quick, | + | <p>I am the thrust, dangerous and quick,<br/> |

| − | + | Great teacher of the other blows.</p> | |

| {{paget|Page:Cod.1324|15v|jpg}} | | {{paget|Page:Cod.1324|15v|jpg}} | ||

Revision as of 19:48, 3 February 2020

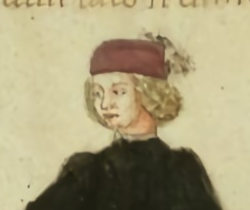

| Philippo di Vadi Pisano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1425 Pisa, Italy |

| Died | 1501 Urbino, Italy (?) |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Nationality | Pisa, Italy |

| Ethnicity | Ligurian |

| Citizenship | Pisan |

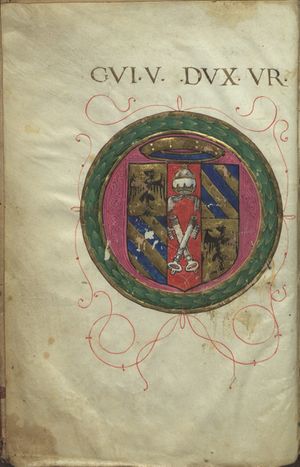

| Patron | Guidobaldo da Montefeltro |

| Influences | Fiore de'i Liberi |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | |

| Notable work(s) | De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi |

| Manuscript(s) |

|

| First printed english edition |

Porzio and Mele, 2002 |

| Translations | |

Philippo di Vadi Pisano was a 15th century Italian fencing master. His name signifies that he was born in Pisa, a city in northern Italy, but little else can be said with certainty about the life of this master. It may be that he was the same Philippo Vadi who was governor of Reggio under the marquisette of Leonello d’Este and later, from 1452 to 1470, counselor to Borso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara.[1] Some time after this, Vadi composed a treatise on fencing entitled De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi ("On the Art of Swordsmanship"); it was dedicated to Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino,[2] and gifted to him between 1482 and 1487,[3] but while this may indicate that he served the duke after leaving Ferrara, there is no record of a Master Vadi being attached to the ducal court.

Vadi was probably an initiate of the tradition of Fiore de’i Liberi, as both his teachings and the format of his treatise closely resemble those of the earlier master. As both Leonello and Borso were sons of Niccolò III d’Este, owner of two copies of Fiore's treatise Fior di Battaglia, Vadi would have had ample opportunity to study his writings.

Treatise

Images |

||

|---|---|---|

To my most illustrious Prince Guido di Montefeltro Duke of Urbino |

[1r.1] Ad illustrissimus Principem meum Guidum Feretranum Ducem Urbinatem | |

This little book I dedicate to you, most honourable prince Guido, |

[1r.2] Hunc tibi do princeps dignissime guide libellum | |

Philippo Vadi offers this book on the Art of fencing in earnest[5] to the illustrious Prince Guido di Montefeltro Duke of Urbino. |

[1r.3] Philippi Vadi servi Liber de Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, ad illustrissimus Principem Guidum Feretranum Ducem Urbini. | |

[6]Just as my earnest mind, devoid of all cowardice and spurred by an outpouring of natural desire in my earliest thriving years, moved me towards warlike deeds and matters; so did it move me, as time progressed and as I grew in strength and knowledge, to learn more of those warlike deeds, matters, styles and skills through hard work, such as how to play with the sword, lance, dagger and pollax. |

[1r.4] HAvendomi mosso per appetito naturale quale producea fuori el mio franco animo alieno da ogni viltade nelli mei primi e floridi anni ad acti e cose bellicose: cussì per processo di tempo cre- [1v.1] sendo in forze et in sapere mi mosse per industria ad volere inparare più arte e modi de ingiegno de dicti acti et cose bellicose, come è giuchare di spada de lanza di daga e azza. | |

Of these things, through the guidance of almighty God, I acquired a good deal of knowledge and this through the practical experience and instruction of many teachers from various different countries, all masters and utterly proficient and knowledgeable in this art. |

[1v.2] De le qual cose medi ante lo aduito de summo idio ne ò acquistato assai bona notitia e questo per pratica experientia e doctrina de molti maestri de varii e diversi paesi amaestrati e docti in perfectione in tale arte. | |

And not to diminish but instead to increase this doctrine so that it will not perish from my negligence, because from it comes no small help in battles, wars, riots and other warlike tumults: instead it gives all men trained and instructed in this material immediate and unique help: it has been suggested and required that I compile a booklet concerning these things by people I have surpassed in the art, and am more long winded than: adding to this various figures and placing various examples so that any man versed in this material can use if for assaults at arms, and can defend himself intelligently and be advised of all the types and styles. |

[1v.3] Et per non minuire anzi volendo acrescere tal doctrina acioché per mia negligentia epsa non perisca per che da epsa non procede pocho alturio ne’ bataglie, guerre, rixe e altri tumulti bellicosi: Immo dona agli omini instruti e periti in tale materia uno prestantissimo e singulare sussidio. Ho proposto e statuido nella mente mia de compillare uno libretto concernente cosse le qualle sono più oltra e più prolixe de tale arte: depingendo in quello varie figure e ponendoli exempli diversi, per li quali qualunqua homo instructo in tal materia, possa usare ne l so asaltare e nel so diffendere, astucie, calidità e avisi di più ragione e manere. | |

Therefore, anyone with a generous spirit will see this little work of mine as a jewel and a treasure and will keep it in memory deep within their heart, so that this art and discipline should never fall into the hands of peasants and low-born men. |

[1v.4] Adunque ciascuno di generoso animo vederà questa mia op ereta, ammi epsa sì come uno gioiello e texauro e recordansello ne lo inti mo core, a ciò che mai, per modo alcuno, tale industria arte e dotrina non perve- [2r.1] nga a le mane de homini rusticali e di vile condizione. | |

Because Heaven has not made these rough-hewn men, ignorant and beyond all cleverness and diligence and wholly bereft of bodily agility, but instead they were made like animals without reason, just to carry heavy burdens and do base and rustic work; and because I declare them to be in every way alien to this science; everyone of perspicacious intelligence and lively limbs such as courtiers [l.10], scholars, barons, princes, dukes and kings, should on the contrary be welcomed into this noble science according to the principle of the Instituta which states: not only should the Imperial Majesty be honoured with Arms, but it must also be armed with sacred laws. |

[2r.2] Perché el cielo non à generato tali homini indocti, rozi et fuori de ogni ingiegno et industria et omnino alieni da la agilità del corpo, ma più tosto sono stati generati a similitudine de animali inragionevoli a portare carichi et fare opere vile e rusticale. E perché debitamente io vi dico loro essere per ogni modo alieni da tal scientia e per l’opposito al mio parere, ciascuno di perspicace ingegno e ligiadro de le membra sue, come sono cortegiani, scolari, baroni, principi, Duchi et Re, debeno essere invitati a questa nobile scientia, secondo el principio de la “Instituta” quale parla e dice così: el non bixogna solo la maestà inperiale essere honorata di arme ma ancora è necesario epsa sia armata de le sacre legge. | |

Nobody should think that there is anything false or any kind of error in my book, because I have omitted and carved out anything unsure, and included only things that I have seen and tested. Let us begin then to explain our intention, with the aid and grace of the omnipotent God, blessed be His name. |

[2r.3] Né sia alcuno quale creda che in questo mio volume sia posta cosa falsa o invelupata de alcuno errore, perché tollendo e rescecando via le cosse dubiose, solo li metterò cose vedute e provate da me: comenzando ad unque ad exprimere la intentione nostra, con l’adiuto e grazia de lo omnipotente dio del qualle el nome sia benedetto in eterno. | |

Some animals, lacking reason, ply their skills naturally without any knowledge. Man, instead, naturally lacks skills and his body lacks weapons. Nature compensates for this deficiency of weapons by giving man his hands, and for his lack of natural skills by offering him the virtues of intelligence and thought. Even if a man were born with some level of skill, he would not be able to acquire the remainder naturally, that is, learn to use all weapons and know each skill. He was therefore not endowed by nature with either skill or weapon. Consequently, among all animals, man needs intelligence and reason, through which art and ingenuity flourish and in which he overtakes and surpasses all other animals. Just so every trained and clever man of good intelligence overtakes and surpasses any other who is stouter and stronger than him. |

[2r.4] Et perché alcuni animali inrationabili fano li loro artificii naturalmente, senza alcuna doctrina de l’homo [2v.1] manca de artificio naturalmente sì come il corpo de quello manca de arme debitamente li presta la natura per lo mancamento de dite arme le mane et in loco de quello che ‘l manca de artificij naturali, li presta la virtù de intellecto e cogitatione, e come si lui avesse avuto alcuni artificii naturalmente non poria acquistare artificii per lo resto; e per lo meglio a lui ad usare tutte le arme e tutti li artificii, però non li fo prestato da dita natura né arme né artificio. Have adoncha bixogno tra li altri animali lo intelletto e ragione, ne le qual cosse fiorisce arte et ingiegni, de’ quali due cosse non solo avanza e supera tutti gli animali: ma ciascuno homo docto e adoctato de bono ingiegno avanza a supedita qualunqua sia più robusto di lui e più pieno di forze. | |

As the famous saying goes: cleverness overcomes strength. And what is greater still and almost incredible: the wise rules the stars. An art that conquers all, and dominates anyone who would fight you or stand against you, is born from the aforesaid cleverness and other piercing thinking. And not only can just one man prevail against another, but also a way and possibility exists for one man to overcome many. Not only do we show the way and the theory of combating the adversary as well as to defend yourself against him, but we also teach methods on how to take the weapon from his hand. |

[2v.2] Iusta illud preclare dictum: ingenium superat vires, et quod maius est et quasi incredibile, sapiens dominabitur astris: nasce da dito ingiegno e da altri e penetrative cogitatione, una arte de vincere superare e debbelare qualunque vol conbatere e contrastare; e non solo adviene che uno homo vinca l’altro, ma ancora nasce modo et posibilità che uno solo superi più persone, e non se mostra solo el modo e documento de assaltare lo adversario e repararsi e deffendersi da lui, ma etiam se insegna advi [3r.1] si de togliere l’arme sue di mano: | |

Oftentimes in these texts, a small person of little strength overcomes, prostrates and throws a big, tough and brave man to the ground; just so, you will see how the humble can overtake the proud, and the unarmed the armed. And many times it happens that someone on foot defeats and conquers someone on horseback. |

[3r.2] per li quali documenti, spese fiate uno de poche forze e picolo sottomete prosterne et sbate uno grande robusto, e valoroso e cusì adviene che anche uno humile avanza el superbo e uno disarmato lo armato. Et molte volte accade che uno a piedi vinci e sconfigie uno da cavallo. | |

But because it would be very inconvenient if this noble doctrine were to wilt and die through negligence, I, Philippo di Vadi from Pisa having studied this art ever since my first flourishing years, having travelled to and practiced in many different countries, lands, castles and cities to collect the teachings and examples of many perfect masters of the art, having acquired and obtained (by the Grace of God) a sufficient portion of the art, I have decided to compose this little work, in which I have organised and shown at least the main points of four types of weapon: the lance, sword, dagger and axe. |

[3r.3] Ma perché el seria cossa molto inconveniente che così nobile doctrina per negligentia perise e venise meno, Io philippo di vadi da pisa, havendo ateso a tale arte insino a li mei primi et floridi anni havendo cercato e praticato più et diversi paesi et terre castelle e citade per racogliere amaestramenti et exempli da più maestri perfecti nell’arte, per la dio gratia havendomi acquistato et conseguito una particella assai sufficiente, ho deliberato de conponere questo mio libreto nel qualle ve si ponerà e dimostrarà almeno la noticia di quatro manere d’arme, cioé lanza, spada, daga e aza. | |

And in this book, I will describe the rules, the methods and the actions of this art, with examples illustrated with various figures, so anyone new to the art can understand and learn how to fight, and by which trick and ploy he can fend off and beat aside the opponent’s attacks and counters. I have only included in the aforesaid book the good and true doctrine, which I have received from the most perfect masters, with great pains, efforts, and sleepless nights. And I have also included things that I have discovered and often tested. |

[3r.4] Et in epso libro per mi si descrivirà regole, modi et atti de talle arte, metendo li exempli con varie figure, aciò che ciascheduno, novo ne l’arte, comprehenda e cognosca li modi de assaltare, e per le qualle astutie e calidità lui expella et rebuti da sé le contrarie e i nimici colpi; ponendo solo nel dicto libro quella doctrina [3v.1] vera e bona la qualle io con grandissimi affanni et fatiche e vigilie ho inparato da più perfectisimi maistri metandoli ancho cosse per mi atrovate e spesso provate. | |

Let me remind and admonish all not to be rashly presumptuous, nor to be so bold as to interfere in this art and discipline unless one is high-minded and filled with gallantry. That is because whoever is thick-brained, pusillanimous and cowardly must be banished from such nobility and refinement. To this doctrine should only be invited such men as soldiers,[7] men at arms, scholars, barons, lords, dukes, princes and kings of the land, and any of those whose task is to govern the state, and to any of these who defend widows and orphans (both of which are pious and divine works). |

[3v.2] Ricordando et amonendo ogniuno non prosumma temerariamente né habia ardire de intermeterse in tale arte e scienzia, se lui non è magnanimo e pien de ardire: perché qualuncha homo grosso d’inzegno, pusilanimo e ville, debbe essere caciato e refudato da tanta nobilità e gientileza: perché solo a questa dottrina se debeno invitare sacomani, homini d’arme, scolari, baroni, Signori, Duchi, Principi e Re di terre de le qualli ad alcuni de loro apertene a governare la repubblica; et ad alcuni de loro apertene deffendere pupili e vedoe: et tute due sono opere divine e pie. | |

And if this little work of mine finds its way into the hands of anyone versed in the art, and appears to him to have anything redundant or wrong, may it please him to cut, take away or add to it as he pleases. Because in the end I place myself under his correction and judgement. |

[3v.3] Et se questa mia opereta pervenisse a mane de alcuno docto nella arte e paresseli che in epsa fosse alcuna cossa superflua o manchevole piazali de resecare minuire e acrescere quello li parerà, perché insino da mò io mi sottopono a sua correctione e censura. |

Images |

||

|---|---|---|

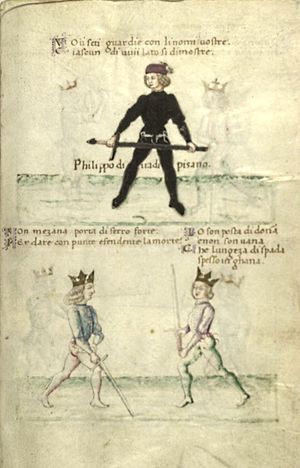

Here are the guards with their names, Each of your sides is shown. |

[16r-a] Voii seti guardie con li nomi vostre

| |

I am the strong middle iron gate Dealing death with thrust and fendente. ::I am the guard of the woman, and I am not vain,

|

[16r-c] Son mezana porta di ferro forte [16r-d] Io son posta di donna e non son vana | |

I am the flat ground iron door, Always impeding cuts and thrusts. ::I am the guard of the falcon, high up above,

|

[16v-a] Son porta di fero piana terrena [16v-b] Son posta di falcon superba e altera | |

I am the short guard of the extended sword, I often strike with the turn back. ::I am the archer’s guard, to deceive

|

[16v-c] Son posta breve di spada longeza [16v-d] Son posta sagitaria per ingiegno | |

I am the guard of the true window I raise from the art the thing from the left. ::I am the crown and I am made master

|

[17r-a] Io son la posta di vera finestra [17r-b] Io son corona e son fatta maestra | |

With the deadly guard of the boar’s tooth Anyone looking for trouble, I’ll give them plenty. ::I am the long guard with the short(ened) sword,

|

[17r-c] Con mortal posta de denti cinghiare [17r-d] Son posta lunga con la spada curta | |

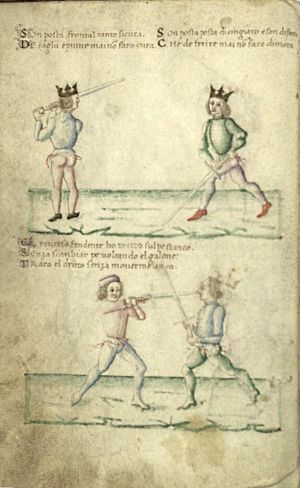

I am the frontal guard, so secure Of cuts and thrusts I have the solution. ::I am the guard of the boar and I am outside,

|

[17v-a] Son posta frontal tanto sicura [17v-b] Son posta posta di cingiaro e son di fora | |

I have made a roverso fendente on the left foot, Without changing the foot turning the hips I strike a dritto without further movement. |

[17v-c] El reverso fendente ho tratto sul pè stanco | |

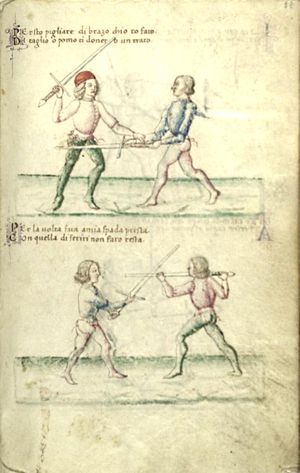

By this grip of your arm that I have made, I can hit you with a cut or pommel strike. |

[18r-a] Per sto pigliare di brazo chio t’ò fato | |

By this turn that I quickly make to my sword I will not pause with this strike. |

[18r-c] Per la volta fata a mia spada presta | |

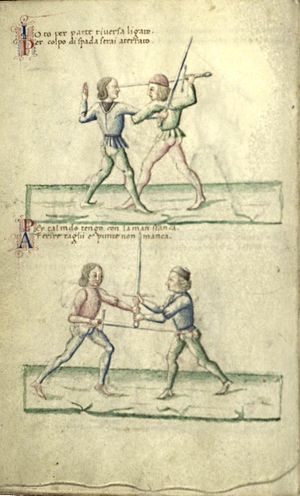

I have bound you from the roverso side, You’ll be thrown to the ground by a blow of the sword. |

[18v-a] Io t’ò per parte riversa ligato | |

In this way I have you with the left hand, I will not hold back striking with cuts and thrusts. |

[18v-c] Per tal modo tengo con la man stanca | |

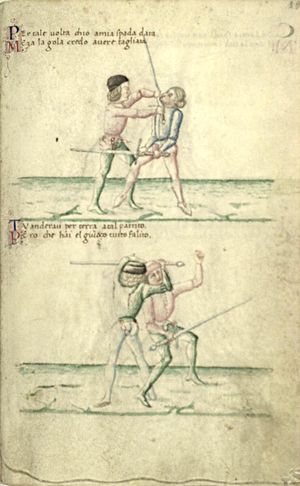

By this turn that I have given to my sword I think I will have cut the middle of your throat. |

[19r-a] Per tale volta ch’i’ ò a mia spada data | |

You will go to the ground with this technique And your play has completely failed. |

[19r-c] Tu anderaii per terra a tal partito | |

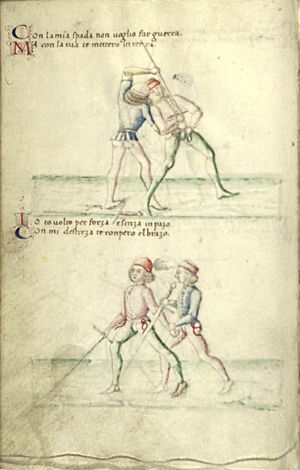

I do not wish to make war with my sword, But with yours I’ll throw you to the ground. |

[19v-a] Con la mia spada non voglio far guerra | |

I have turned you with force and without difficulty With my skill I will break your arm. |

[19v-c] Io t’ò volto per forza e senza inpazo | |

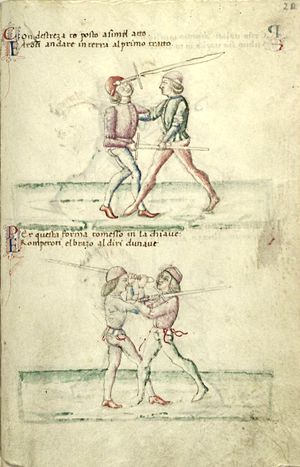

With skill I have placed you in a similar position, I’ll make you go to the ground at the first blow. |

[20r-a] Con destreza t’ò posto a simil atto | |

In this way I’ll put you in a lock And break your arm (in the time it takes to) say “hello”. |

[20r-c] Per questa forma t’ò messo in la chiave | |

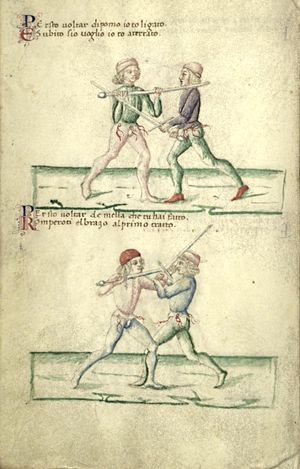

By this turn of the pommel I have bound you, Immediately If I want to I’ll throw you to the ground. |

[20v-a] Per sto voltar di pomo io t’ò ligato | |

By this turn of the blade that you have done, I will break your arm at the first attempt. |

[20v-c] Per sto voltar de mella che tu hai fatto | |

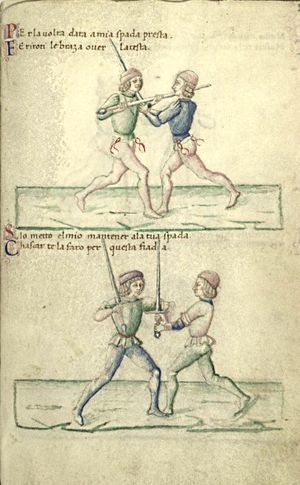

By the turn quick I have given my sword, I’ll strike your arm or your head. |

[21r-a] Per la volta data a mia spada presta | |

If I put my hilt to your sword I’ll make it fall with this action. |

[21r-c] S’io metto el mio mantener a la tua spada | |

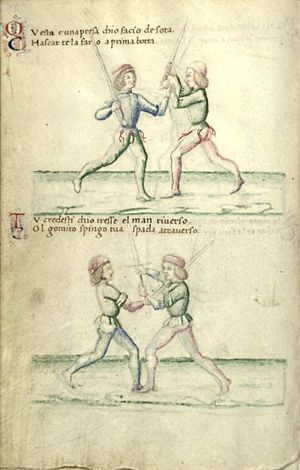

This is a grip that I do from below, I will make it fall at the first go. |

[21v-a] Questo è una presa ch’io facio de fora | |

You believed I would strike with a backhand blow, With the elbow I push your sword across. |

[21v-c] Tu credesti ch’io tresse el man riverso | |

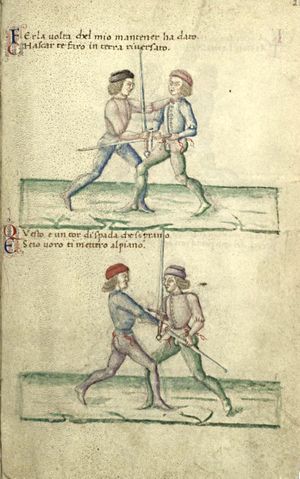

Making the turn that my handle has given, I make you fall to the ground backwards. |

[22r-a] Per la volta ch’el mio mantener ha dato | |

This is a disarm that is above, And if I want to I’ll lay you flat. |

[22r-c] Questo è un tor de spada ch’è soprano | |

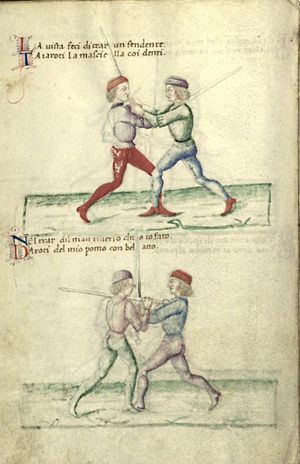

The feint that I made to strike a fendente, Cuts the jaw and teeth together. |

[22v-a] La vista feci di trar un fendente | |

From the backhand strike that I have done, I’ll give you a good strike with my pommel. |

[22v-c] Nel trar d’il man riverso ch’io t’ò fato | |

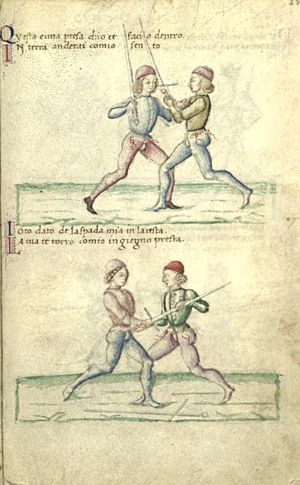

This is a grip that I do on the inside, I feel that you’re going to the ground. |

[23r-a] Questa è una presa ch’io te facio dentro | |

I have given you my sword in the head, Yours I’ll take with my quick cunning. |

[23r-c] Io t’ò dato de la spada mia in la testa | |

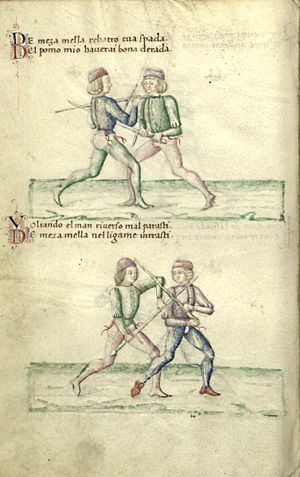

I beat your sword aside with the middle of the blade, You’ll get a good deal from my pommel. |

[23v-a] De meza mella rebatto tua spada | |

Turning a roverso you parried badly, Entering into a bind at the middle of the blade |

[23v-c] Voltando el man riverso mal parasti |

Images |

||

|---|---|---|

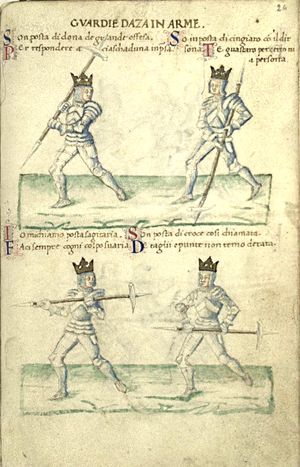

|

Guards of the Axe in Armour. I am the guard of the woman, of great offence, To respond to any situation. ::I am in the guard of the boar, with its saying,

|

[24r] GUARDIE D’AZA IN ARME [24r-a] Son posta di dona de grande offesa [24r-b] So in posta di cingiaro con il dir sona | |

I am called the Archer’s guard, I always make blows deviate. ::I am the guard of the cross, so called,

|

[24r-c] Io mi chiamo posta sagitaria [24r-d] Son posta di croce così chiamata | |

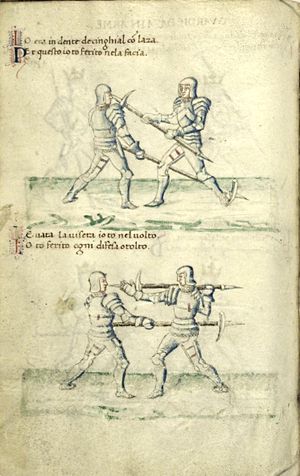

I was in boar’s tooth with the axe, In this way I have struck you in theface. |

[24v-a] Io era in dente de cinghial con l’aza | |

Lifting the visor I strike your face, I struck you: all defences are gone. |

[24v-c] Levata la visera io t’ò nel volto | |

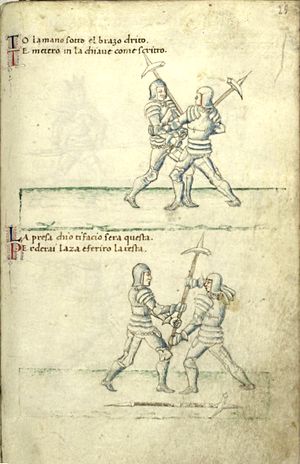

I place my hand under the right arm I’ll place you in the lock as is written. |

[25r-a] T’ò la mano sotto el brazo drito | |

This is the grip that I do to you, You’ll lose your axe and I’ll strike your head. |

[25r-c] La presa ch’io ti facio serà questa |

Images |

||

|---|---|---|

|

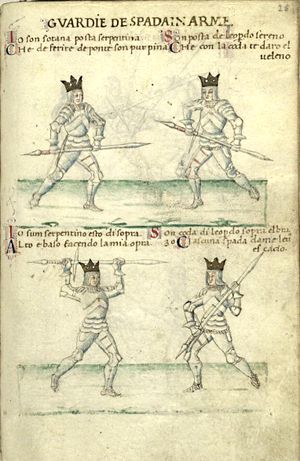

Guards of the Sword in Armour. I am the lower snake guard, That is good for striking with thrusts. ::I am the guard of the serene leopard,

|

[26r] GUARDIE DI SPADA IN ARME [26r-a] Io son sotana posta serpentina [26r-b] Son posta de leopardo sereno | |

I am the snake, held high, Above and below I do my work. ::I am the leopard’s tail over the arm,

|

[26r-c] Io sum serpentino e sto di sopra [26r-d] Son coda di leopardo sopra el brazo | |

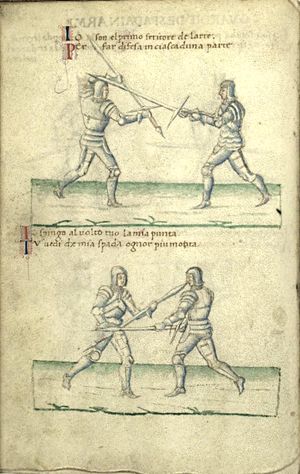

I am the first wounder of the art, To make defence on any side. |

[26v-a] Io son il primo feritore de l’arte | |

I push my point into your face, You see my sword rising upand up. |

[26v-c] Io spingo al volto tuo la mia punta | |

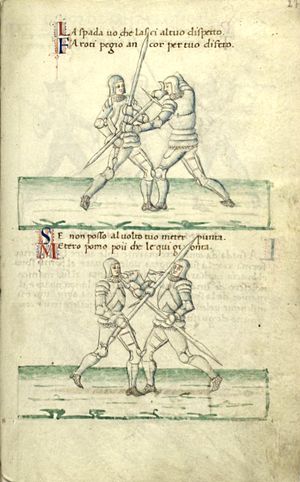

You will let go of your sword in spite of your wishes, I will do even worse to you too. |

[27r-a] La spada vo’ che lasci al tuo dispetto | |

If I can’t stick a point in your face, I’ll stick a pommel instead, as it is there. |

[27r-c] Se non posso al volto tuo meter punta | |

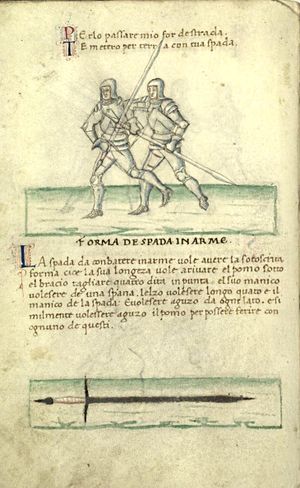

By the pass I have made out of the way, I’ll throw you to the ground with your sword. |

[27v-a] Per lo passare mio for de strada | |

|

FORM OF THE SWORD IN ARMOUR The sword for fighting in armour should have the form as written below, thus: it should be of a length to come with the pommel under the arm, sharpened four fingers from the point. It’s handle should be of a span. The crossguard should be as long as the handle of the sword. And it should be pointed on every side. And similarly, the pommel should be pointed, so that you can strike with any of these parts. |

[27v-c] FORMA DE SPADA IN ARME La spada da conbatere in arme vole avere la sotoscrita forma cioé la sua longeza vole arivare el pomo sotto el bracio, tagliare quatro dita in punta, el suo manico vole eser de una spana. L’elzo vol esere longo qua(n)to è il manico de la spada: e vol esere aguzo da ogni lato, e similmente vol esere aguz o il pomo per possere ferire con ognuno de questi. |

Images |

||

|---|---|---|

|

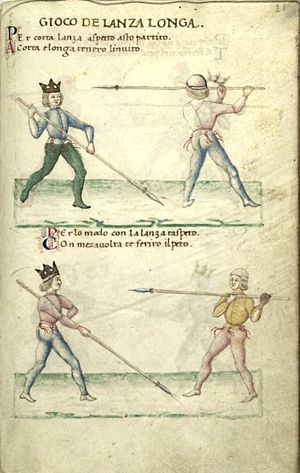

Play of the Long Lance With a short lance I’ll wait in this way, I invite you to come with long and short. |

[28r] GIOCO DE LANZA LONGA [28r-a] Per corta lanza aspetto a sto partito | |

From the way I wait for you with a spear I can strike you in the chest with a half turn. |

[28r-c] Per lo modo con la lanza t’aspeto | |

By the half turn that I have made to my spear, I’ll strike you in the chest or side. |

[28v-a] Per meza volta che mia lanza à dato | |

Here end the blows of the spear, They usually go to this technique. |

[28v-c] Qui finiscono i ferir de lanza |

Images |

||

|---|---|---|

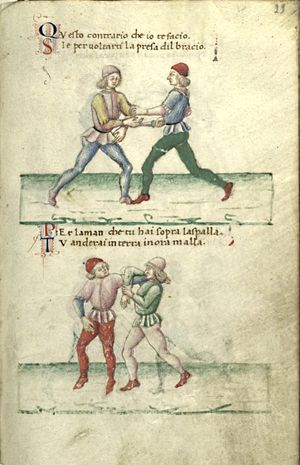

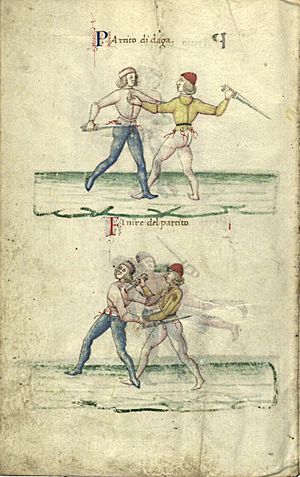

[1] I do this counter to you,Turning you with the grip on your arm. |

[29r-a] Questo contrario che io te facio | |

[2] With the hand that you have on my shoulder,You’ll go to the ground in a bad hour. |

[29r-c] Per la man che tu hai sopra la spalla | |

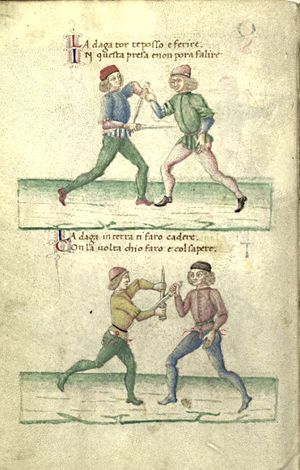

[3] I can take the dagger and strike youWith this grip, and I cannot fail. |

[29v-a] La daga tor te posso e ferire | |

[4] With the dagger on the ground I’ll make you fallWith the turn that I do, and with my knowledge. |

[29v-c] La daga in terra ti farò cadere | |

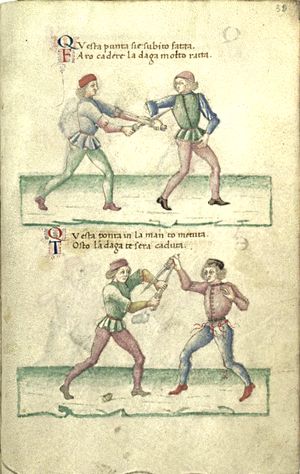

[5] This thrust is done immediatelyI make your dagger fall very fast. |

[30r-a] Questa punta sie subito fataa | |

[6] This thrust that I have placed in your hand,Quickly you will drop your dagger. |

[30r-c] Questa ponta in la man t’ò metuta | |

[7] This cover I make very quickly,So you will be placed in the lock. |

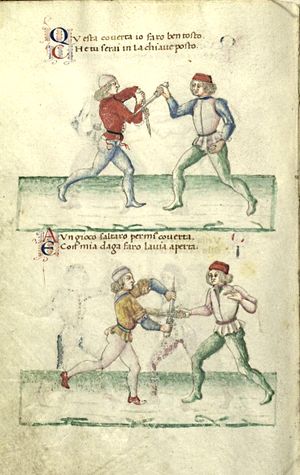

[30v-a] Questa coverta io farò ben tosto | |

[8] I will leap to a play using this cover,And with my dagger I’ll open the way. |

[30v-c] A un gioco saltarò per mi coverta | |

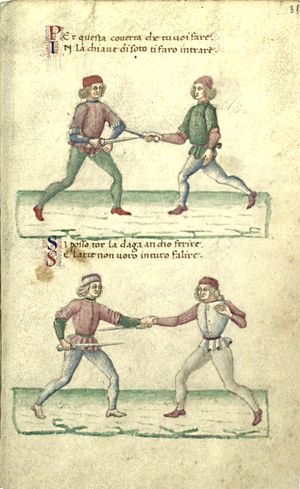

[9] With this cover that you want to do,I’ll make you go into the lower lock. |

[31r-a] Per questa coverta che tu voi fare | |

[10] I can take the dagger or strike,If I don’t want to completely fail the art. |

[31r-c] Si posso tor la daga ancho ferire | |

[11] If I push the dagger towards the ground,You will make no more war with it to me. |

[31v-a] S’io carco la daga verso terra | |

[12] Here I look for your hand to strike itI’ll make you come under the lock. |

[31v-c] Qui cerco la tua man per lei feri(ri) | |

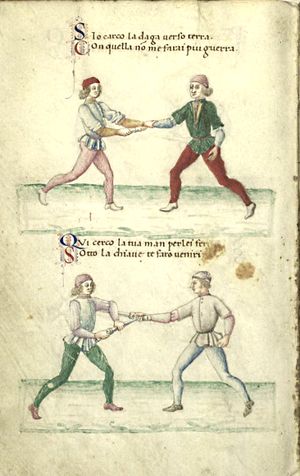

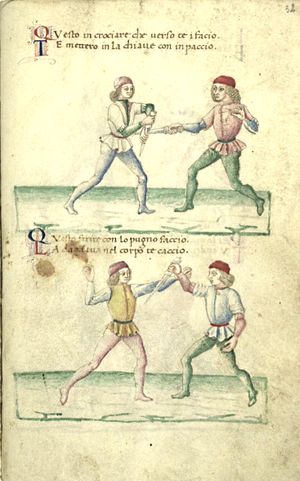

[13] This crossing that I make against youI’ll place you in the lock without difficulty. |

[32r-a] Questo incrociare che verso te i’ facio | |

[14] This strike I make with the fist,I’ll stick your dagger into your body. |

[32r-c] Questo ferire con lo pugno faccio | |

[15] I make the cover of one hand,I make your dagger go to the ground. |

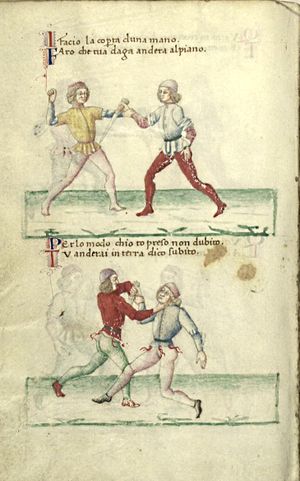

[32v-a] I’ facio la coperta d’una mano | |

[16] From the way I have grabbed you I do not doubtThat you’ll go to the ground, I say immediately! |

[32v-c] Per lo modo ch’io t’ò preso non dubito | |

[17] By the way that I have got youI’ll break the arm and the dagger very quickly. |

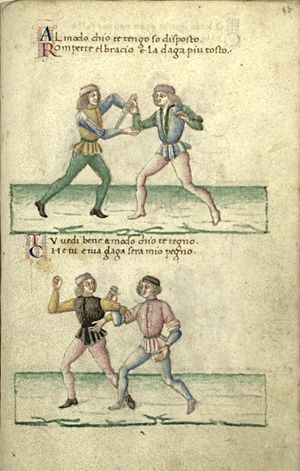

[33r-a] Al modo ch’io te tengo so’ disposto | |

[18] You see well the way that I have you,So you and your dagger will be my pawn. |

[33r-c] Tu vedi bene a modo ch’io te tegno | |

[19] I see that this play will not fail me.As I break your arm over my shoulder. |

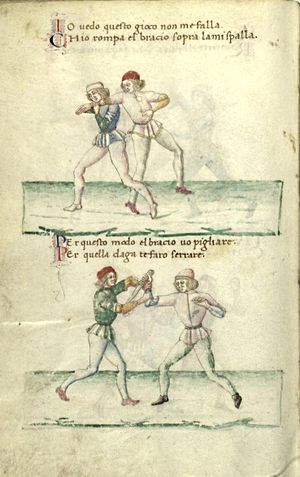

[33v-a] Io vedo questo gioco non me falla | |

[20] Because of this way that the arm is grabbed,I will lock you with this dagger. |

[33v-c] Per questo modo el bracio vo pigliare | |

[21] I saw that you are bound and going to the ground,I break the arm and you’ll lose the dagger. |

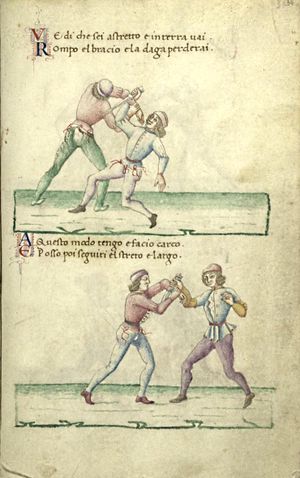

[34r-a] Vedi che sei astretto e in terra vai | |

[22] In this way I have you, and I make a burden,And I can then follow the close and wide. |

[34r-c] A questo modo tengo e facio carco | |

[23] I come at you with crossed arms,And I can do all the previous plays. |

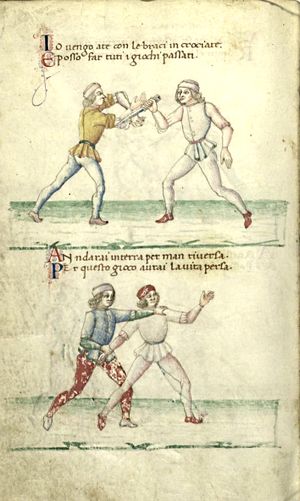

[34v-a] Io vengo a te con le braci incrociate | |

[24] You’ll go to the ground by the backhand,By this play your life is lost. |

[34v-c] Andarai in terra per man riversa | |

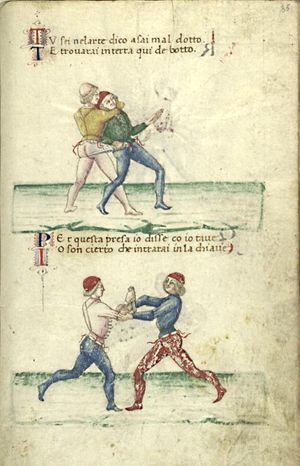

[25] I say you are badly taught in this art;You will find yourself suddenly on the ground. |

[35r-a] Tu sei ne l’arte dico asai mal dotto | |

[26] By this grip I say I have you,I am certain you will go into the lock. |

[35r-c] Per questa presa io disse co’ io t’ave | |

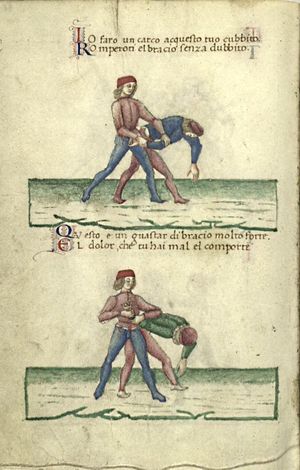

[27] I make a lock to this, your elbow;I’ll break your arm for you without doubt. |

[35v-a] Io farò un carco a cquesto tuo cubbito | |

[28] This is a very strong destruction of the arm,The pain that you’ll have will ruin your composure. |

[35v-c] Questo è un guastare di bracio molto forte | |

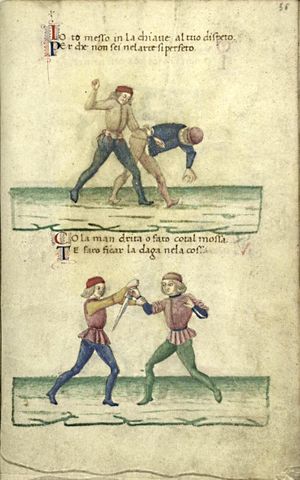

[29] I have put you in the lock, to your despite,Because you are not perfect in the Art. |

[36r-a] Io t’ò messo in la chiave al tuo dispeto | |

[30] With my right hand I have made this move;I will stick the dagger in your thigh. |

[36r-c] Co’ la man drita ò fato cotal mossa | |

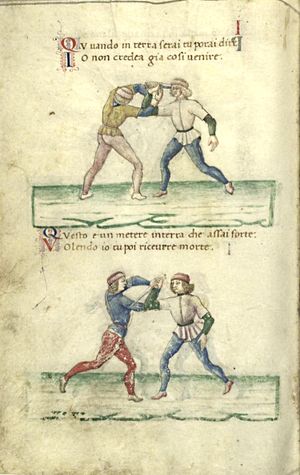

[31] When you’re on the ground you’ll say,“I didn’t believe it would come to this”. |

[36v-a] Quando in terra serai ti porai dire | |

[32] This is a strong way to throw someone to the ground;If I wish it, you will die. |

[36v-c] Questo è un metere in terra ch’è assai forte | |

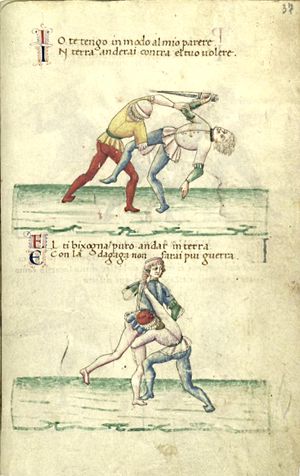

[33] I have you, by the way that I parried;You will go to the ground against your wishes. |

[37r-a] Io te tengo in modo al mio parere | |

[34] You must just go to the ground,And you’ll make no more war with the dagger. |

[37r-c] El ti bixogna puro andar in terra | |

[35] By the pass that I do under the arm,You’ll go to the ground with much trouble. |

[37v-a] Per lo passare fato soto el bracio | |

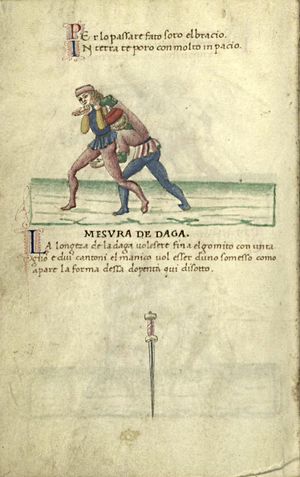

|

[36] THE MEASURE OF THE DAGGERThe length of the dagger should be just to the elbow, with an edge and two corners. The grip should be the length of the fist, as the shape is shown depicted here below. |

[37v-c] MESURA DE DAGA La longeza de la daga vol esere fin a el gomito con un taglio e dui cantoni, el manico vol esser d’uno somesso como apare la forma d’essa dopent a qui di sotto. |

Images |

||

|---|---|---|

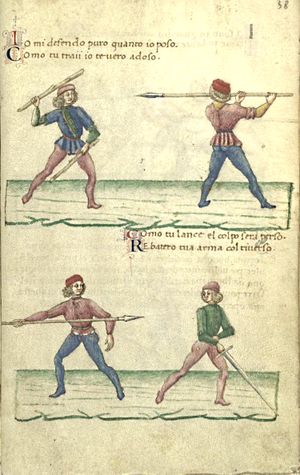

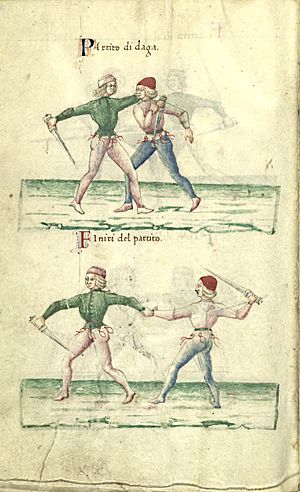

I defend myself just as well as I can, As you strike I will overcome you. |

[38r-a] Io mi difendo puro quanto poso | |

As you throw, your blow will be lost; I’ll beat away your weapon with a backhand blow. |

[38r-c] Como tu lance el colpo serà perso | |

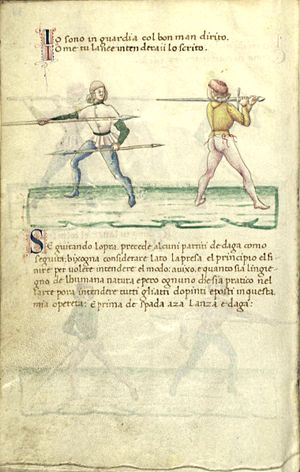

I am in guard with a good forehand blow, As you throw at me you’ll understand the text. |

[38v-a] Io sono in guardia col bon man dirito | |

|

Following the work are some dagger techniques as follows. You must consider the act, the grip, the principle and the finish to understand the way. Knowing how cunning human nature is, and for everyone who is practiced in the art can understand all the actions depicted and shown in this, my little work, mainly of the sword, the axe, the spear and the dagger. |

[38v-c] Seguitando l’opra precede alcuni partiti de daga como seguita: bixogna considerare l’ato la presa el principio el finire, per volere intendere el modo: avixo e quanto sia l’ingiegno de l’humana natura e però ognuno che sia pratico nell’arte porà intendere tutti gli altri dopinti e posti in questa mia opereta e prima de spada, aza, lanza e daga. | |

|

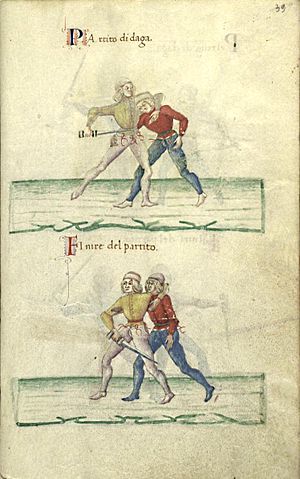

Dagger technique |

[39r-a] Partito de daga | |

|

End of the technique |

[39r-c] Finiri del partito | |

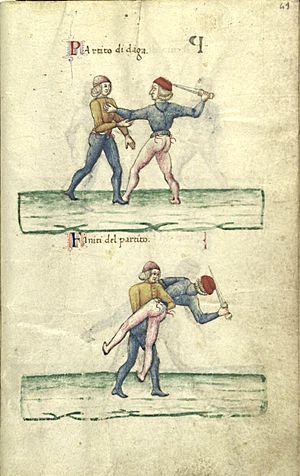

|

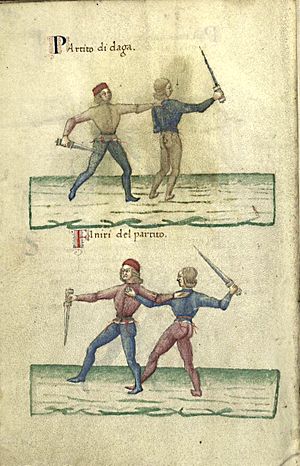

Dagger technique |

[39v-a] Partito de daga | |

|

End of the technique |

[39v-c] Finiri del partito | |

|

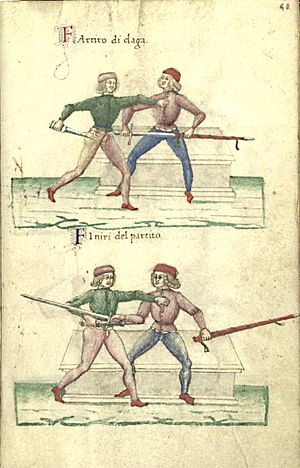

Dagger technique |

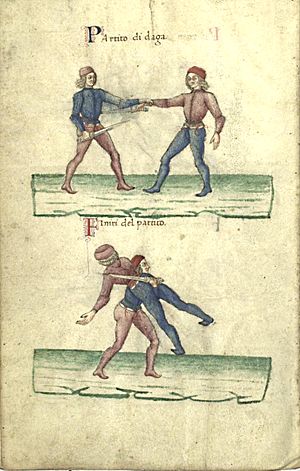

[40r-a] Partito de daga | |

|

End of the technique |

[40r-c] Finiri del partito | |

|

Dagger technique |

[40v-a] Partito de daga | |

|

End of the technique |

[40v-c] Finiri del partito | |

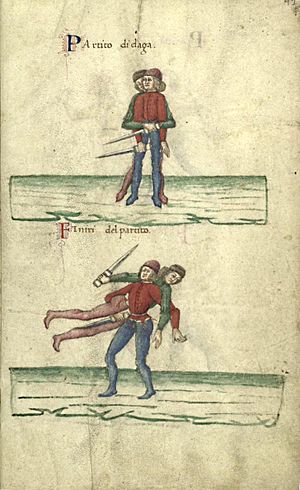

|

Dagger technique |

[41r-a] Partito de daga | |

|

End of the technique |

[41r-c] Finiri del partito | |

|

Dagger technique |

[41v-a] Partito de daga | |

|

End of the technique |

[41v-c] Finiri del partito | |

|

Dagger technique |

[42r-a] Partito de daga | |

|

End of the technique |

[42r-c] Finiri del partito | |

|

Dagger technique |

[42v-a] Partito de daga | |

|

End of the technique |

[42v-c] Finiri del partito |

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Images | Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma | WikiMedia Commons | |

| Translation | Guy Windsor | The School of European Swordsmanship | |

| Transcription | Marco Rubboli and Luca Cesari | Index:De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi (MS Vitt.Em.1324) |

Additional Resources

- Vadi, Filippo. Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi: 15th Century Swordsmanship of Master Filippo Vadi. Trans. Luca Porzio and Gregory Mele. Union City, CA: Chivalry Bookshelf, 2002. ISBN 978-1891448164

- Vadi, Filippo; Rubboli, Marco; and Cesari, Luca. L'arte Cavalleresca del Combattimento. Rome: Il Cerchio Iniziative Editoriali, 2005. ISBN 88-8474-079-7

- Windsor, Guy. Veni Vadi Vici. A Transcription, Translation and Commentary of Philippo Vadi's De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi. The School of European Swordsmanship, 2013. ISBN 978-952-93-1686-1

References

- ↑ For an alternative theory as to the identity of Philippo di Vadi, see Greg Mele. "Interesting information on the Vadi family (Philippo Vadi)". HEMA Alliance Forum. 06 June 2012. Retrieved 09 October 2012.

- ↑ Vadi, Philippo di. De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi [manuscript]. MS Vitt. Em. 1324. Rome, Italy: Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma, 1480s.

- ↑ Rubboli, Marco and Cesari, Luca. The Knightly Art of Combat of Filippo Vadi. Document circulated online.

- ↑ The translation of these lines was kindly done by Alan Cross, personal correspondence, 28 September 2016.

- ↑ The title that the manuscript is known by comes from this line of the book: de arte gladiatoria dimicandi. Dimicare means to fight in earnest against your enemies; l’arte gladiatoria is the art of fencing. Together, the sense is “the art of fencing in earnest against your enemies”, as opposed to fencing for fun, exercise or display.

- ↑ I am indebted to both Prof Alessandra Petrina and Tom Leoni for their suggestions on improving this section.

- ↑ The word here is ‘sacomani’ (more commonly saccomani), a kind of man at arms who follows the army looking for spoils. I think ‘scavenger’ would not be inaccurate, but clearly Vadi is laying out a hierarchy of martial prowess, with kings at the top, barons in the middle, and men at arms near the bottom. Saccomani is the lowest class of men worthy to learn the art, and so elevated above what comes to mind when we think ‘scavenger’. I’ve used the generic ‘soldier’ here. It is not a normal translation of this term, but it fits this hierarchy better.

- ↑ I, and Mele and Porzio before me (on page 41), were confounded by the page break between this line and the next. E mostrallo con breve eloquenza./La geometria che divide e parte. F3v, f4r. I am indebted to Prof Petrina for pointing out that Geometry, not the author, is the subject of the sentence. I mention this particularly because I know that many readers will trace the translation line by line, comparing it to a transcription or the scans of the ms, and may wonder why Geometry is apparently on the wrong line! It serves to illustrate the differences between the two languages, and as a reminder that similar changes to word order can be expected throughout.

- ↑ Note that on folio 28r where he gives the form of the sword to be used in armour, the crossguard is as long as the handle alone, not handle and pommel together. The images tend to suggest this latter arrangement.

- ↑ This could refer to the blade, but most practitioners believe it refers to the crossguard itself, which can indeed be sharpened for striking with, as we see in the section on combat with the sword in armour. The word is ‘ferruza’; ‘ferruzo’ means ‘a little piece of iron’, so the implication is that this would refer to the crossguard.

- ↑ si tu averai nel cervel tuo sale, lit. “if you have salt in your brain”.