|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Henry de Sainct Didier"

(→Treatise: added rectangle picture - I don't think I can convey it with text. I also think I shouldn't have named it the way it is, but I also don't know how to rename nor delete it.) |

m (→Treatise) |

||

| Line 163: | Line 163: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | And to follow | + | | And in order to follow the experienced well and imitate them, of two good things one must choose the better, and of two bad things to avoid both if possible and if not at least avoid the worse, and in doing so I advise all said adherents to take the better of the said two steps, which is the one where you stand on the left foot initially with weapons in hand to make one of the said three drawings. |

| Et pour bien suivre les doctes, & les immiter, faut de deux choses bonnes choisir la meilleure, & de deux mauvaises, eviter les deux, si faire se peut, sinon la pire, & en ce faisant, je conseille à tous lesdits suppots de prendre la meilleure desdites deux desmarches, qui est celle qu’on se tient sur le pied gauche pour la premiere fois, en mettant les armes au poing, faisant un desdits trois desgainements. | | Et pour bien suivre les doctes, & les immiter, faut de deux choses bonnes choisir la meilleure, & de deux mauvaises, eviter les deux, si faire se peut, sinon la pire, & en ce faisant, je conseille à tous lesdits suppots de prendre la meilleure desdites deux desmarches, qui est celle qu’on se tient sur le pied gauche pour la premiere fois, en mettant les armes au poing, faisant un desdits trois desgainements. | ||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | As for me I believe that the left foot is the best because one can be free to take more time and move farther than on the step of the right foot, and therefore to attack and to defend better, as will be seen later in the section on the strikes. | + | | As for me I believe that the left foot is the best because one can be free to take more time and move farther than on the step of the right foot, and therefore to attack effectively and to defend better, as will be seen later in the section on the strikes. |

| Quant à moy je dy soy tenant sur le pied gauche est le meilleur, par ce que y estant on a liberté de prendre plus de temps, & grande course, que sur la desmarche du pied droict & par consequent de bien assaillir, & de beaucoup mieux se deffendre, comme se verra cy aprés à l’ordre des coups. | | Quant à moy je dy soy tenant sur le pied gauche est le meilleur, par ce que y estant on a liberté de prendre plus de temps, & grande course, que sur la desmarche du pied droict & par consequent de bien assaillir, & de beaucoup mieux se deffendre, comme se verra cy aprés à l’ordre des coups. | ||

| Line 185: | Line 185: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | This is the reason why we know that stepping with the left foot is better than the said right foot. | + | | This is the reason why we know that stepping with the left foot is better than that of the said right foot. |

| Voyla la raison pourquoy la desmarche qu’on faict sus ledit pied gauche, est meilleure que celle dudit pied droict. | | Voyla la raison pourquoy la desmarche qu’on faict sus ledit pied gauche, est meilleure que celle dudit pied droict. | ||

| Line 205: | Line 205: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | Some demonstrators, when they define the said guards, start at the top. As for me, I start on the bottom, since everything begins at the foundations. For example, learned | + | | Some demonstrators, when they define the said guards, start at the top. As for me, I start on the bottom, since everything begins at the foundations. For example, learned people do not start by teaching advanced level sciences; neither do masons start on the buildings when they construct houses; they start on the foundations. And so I start on the low guard which is the foundation to guarding well. |

| Les aucuns demonstrateurs, quand ils definissent lesdites gardes, accommencent à la haute. Quant à moy, je commence à la basse, attendu que toutes choses se commencent aux fondements. Comme pour exemple, les gens doctes ne commencent à monstrer les sciences aux hautes, ne les maçons quand ils viennent à commencer à bastir les maisons, ne commencent pas à la tuille, ains au fondement. Et par ainsi je commence à la basse, qui est le fondement qu’on doit bien garder. | | Les aucuns demonstrateurs, quand ils definissent lesdites gardes, accommencent à la haute. Quant à moy, je commence à la basse, attendu que toutes choses se commencent aux fondements. Comme pour exemple, les gens doctes ne commencent à monstrer les sciences aux hautes, ne les maçons quand ils viennent à commencer à bastir les maisons, ne commencent pas à la tuille, ains au fondement. Et par ainsi je commence à la basse, qui est le fondement qu’on doit bien garder. | ||

| Line 211: | Line 211: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | It is true that this low guard can itself | + | | It is true that this low guard can itself generate two other lows: one on the right side and the other on the left side. |

| Bien est vray, que de ceste garde basse, s’en peut engendrer deux autres basses, l’une est sur le costé droit, l’autre sur le costé gauche. | | Bien est vray, que de ceste garde basse, s’en peut engendrer deux autres basses, l’une est sur le costé droit, l’autre sur le costé gauche. | ||

| Line 229: | Line 229: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | These said two guards created by the said low | + | | These said two guards created by the said low is often done for drawing some ignorant strikes who makes either a high right-hand or a high thrust; because we cannot use another strike, which we easily can trick and hit the attacking enemy who would be surprised, and would not consider the mistake that could come from being on the said two imagined guards. But the original low guard is the most effective, so therefore there are no more than three guards as stated. |

| Cesdites deux gardes engendrées de ladite basse, elle se font bien souvent pour attirer quelque coup des ignorans, qui fera un maindroict, ou un estoc haut ; car autre coup on ne peut, sur lesquels facilement on peut attraper & toucher l’ennemy assaillant qui sera estourdy, & ne considerera l’accident qui peut venir, estant sur sesdittes deux gardes faintes. Mais la garde basse leur mere est la plus certaine, de sorte qu’il n’y a que trois gardes, comme dit est. | | Cesdites deux gardes engendrées de ladite basse, elle se font bien souvent pour attirer quelque coup des ignorans, qui fera un maindroict, ou un estoc haut ; car autre coup on ne peut, sur lesquels facilement on peut attraper & toucher l’ennemy assaillant qui sera estourdy, & ne considerera l’accident qui peut venir, estant sur sesdittes deux gardes faintes. Mais la garde basse leur mere est la plus certaine, de sorte qu’il n’y a que trois gardes, comme dit est. | ||

| Line 248: | Line 248: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | It is true that they can be multiplied in six clean targets on the human body, which must be kept well, as well as a good tennis player must keep the es<ref>Dupuis describes this as a wooden board placed in the back wall of the tennis court which, if hit by a volley, is scored immediately. In modern tennis, this board is replaced by a grid.</ref> well | + | | It is true that they can be multiplied in six clean targets on the human body, which must be kept well, as well as a good tennis player must keep the es<ref>Dupuis describes this as a wooden board placed in the back wall of the tennis court which, if hit by a volley, is scored immediately. In modern tennis, this board is replaced by a grid.</ref> well so that the ball of the opposing party does not touch it. So too must a good fencer be careful that one of the three strikes do not hit the six targets that can be adapted as stated, which will be seen later. |

| Bien est vray qu’ils se peuvent multiplier en six lieux propres sur corps humain, qui faut bien garder, tout ainsi qu’un bon joueur de paulme faut qu’il garde bien l’es,<ref>« L'es », habituellement orthographiée « ais », désigne une planche de bois placée dans le mur du fond de la salle de jeu de paume qui, si elle est touchée par un coup de volée, donne le point immédiatement. Dans le jeu de paume moderne, cette planche est remplacée par une grille. Il est possible que cet « ais » ait donné le terme anglais d'« ace » que les étymologies modernes confondent avec l'« as » du jeu de carte. Voir la définition d' « ais » de l'Encyclopédie de Diderot et d'Alembert.</ref> que lesteu<ref>L’esteuf : ancien nom pour la balle.</ref> de partie adverse ne le touche. Aussi faut il qu’un bon tireur d’armes garde bien qu’un desdits trois coups ne touchent aux six lieux ausquels se peuvent adapter comme dit est, dont se verront cy apres. | | Bien est vray qu’ils se peuvent multiplier en six lieux propres sur corps humain, qui faut bien garder, tout ainsi qu’un bon joueur de paulme faut qu’il garde bien l’es,<ref>« L'es », habituellement orthographiée « ais », désigne une planche de bois placée dans le mur du fond de la salle de jeu de paume qui, si elle est touchée par un coup de volée, donne le point immédiatement. Dans le jeu de paume moderne, cette planche est remplacée par une grille. Il est possible que cet « ais » ait donné le terme anglais d'« ace » que les étymologies modernes confondent avec l'« as » du jeu de carte. Voir la définition d' « ais » de l'Encyclopédie de Diderot et d'Alembert.</ref> que lesteu<ref>L’esteuf : ancien nom pour la balle.</ref> de partie adverse ne le touche. Aussi faut il qu’un bon tireur d’armes garde bien qu’un desdits trois coups ne touchent aux six lieux ausquels se peuvent adapter comme dit est, dont se verront cy apres. | ||

| Line 254: | Line 254: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | It should be noted that fencing and tennis are related, and whoever knows how to play tennis well will be able to strike well easily and early | + | | It should be noted that fencing and tennis are related, and whoever knows how to play tennis well will be able to strike well easily and early in fencing. |

| Faut noter que les armes, & la paulme sont cousins germains, & qui scaura bien jouer à la paulme, facilement & tost scaura bien tirer des armes. | | Faut noter que les armes, & la paulme sont cousins germains, & qui scaura bien jouer à la paulme, facilement & tost scaura bien tirer des armes. | ||

| Line 266: | Line 266: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | The following are the names of said six clean targets | + | | The following are the names of the said six clean targets where one can and must throw the said three strikes which are: |

* Right-Hand | * Right-Hand | ||

| Line 349: | Line 349: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | And so I come attacking the said Fabrice first, and say to him Sir Fabrice | + | | And so I come attacking the said Fabrice first, and say to him, "Sir Fabrice, before discussing presently with you about none other than the said fencing, I want to know how many strikes the attacking enemy can offend the defendant. And yet with your grace, I pray you tell me." |

| Et alors je me viens atacquer premierement audit Fabrice, & luy dis Seigneur Fabrice, avant que tirer à present avec vous, ny avec autre ausdites armes, je veux sçavoir de combien de coups l’ennemy assaillant peut offencer le deffendant. Et pourtant, de grace vous prie, le moy dire. | | Et alors je me viens atacquer premierement audit Fabrice, & luy dis Seigneur Fabrice, avant que tirer à present avec vous, ny avec autre ausdites armes, je veux sçavoir de combien de coups l’ennemy assaillant peut offencer le deffendant. Et pourtant, de grace vous prie, le moy dire. | ||

| Line 355: | Line 355: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | And so responding the said Fabrice said that there are many blows, blows in Neapolitan is what is called strikes in French. And hearing this response uttered by the said Fabrice the said Author answered that this answer is infinite and vague. Responding again the said Fabrice asked | + | | And so responding the said Fabrice said that there are many blows, blows in Neapolitan is what is called strikes in French. And hearing this response uttered by the said Fabrice the said Author answered that this answer is infinite and vague. Responding again the said Fabrice asked, "Sir why do you say that my answer is impertinent?" |

| Et alors respondit ledit Fabrice & dit, de plusieurs bottes, bottes en napollitain vaut autant à dire que coups en françois. Et encores oyant ledit Autheur cette response proferée par ledit Fabrice, estre infinie et incertaine. Respondit encore ledit Fabrice & dist seigneur pourquoy dictes vous que ma reponse est impertinente. | | Et alors respondit ledit Fabrice & dit, de plusieurs bottes, bottes en napollitain vaut autant à dire que coups en françois. Et encores oyant ledit Autheur cette response proferée par ledit Fabrice, estre infinie et incertaine. Respondit encore ledit Fabrice & dist seigneur pourquoy dictes vous que ma reponse est impertinente. | ||

| Line 386: | Line 386: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | So the said Author, without pause responded to him and said that these two answers that he responded is wrong, whereas one is a response that is plural, | + | | So the said Author, without pause responded to him and said that these two answers that he responded is wrong, whereas one is a response that is plural, the other is singular. The plural is worthless given the reason above; the singular which is when he said above about there being five blows is also impertinent. The reason is because there are too many and thus some must be removed. |

| Alors le dit Autheur, sans bien peu d’intervalle luy respondit & dit que telles responses contenoient deux chefs, par lesquels il avoit mal respondu, attendu qu’il y a une response qui est plurielle, & l’autre singuliere. La plurielle ne vaut rien, la raison est cy dessus donnée, la singuliere qui est quand il a dit cy dessus de cinq bottes n’est aussi pertinente. La raison par ce que il en y a trop & par ainsi en faut oster. | | Alors le dit Autheur, sans bien peu d’intervalle luy respondit & dit que telles responses contenoient deux chefs, par lesquels il avoit mal respondu, attendu qu’il y a une response qui est plurielle, & l’autre singuliere. La plurielle ne vaut rien, la raison est cy dessus donnée, la singuliere qui est quand il a dit cy dessus de cinq bottes n’est aussi pertinente. La raison par ce que il en y a trop & par ainsi en faut oster. | ||

| Line 392: | Line 392: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | The said Fabrice, seeing that I said that we must remove some of the strikes of the said blows, replied to know of my true definition and secret and said to me, Sir S. Didier, why have you said these responses that I said above that of the many blows and of the five blows are incorrectly answered by me? | + | | The said Fabrice, seeing that I said that we must remove some of the strikes of the said blows, replied to know of my true definition and secret and said to me, "Sir S. Didier, why have you said these responses that I said above that of the many blows and of the five blows are incorrectly answered by me?" |

| Voyant ce, ledit Fabrice, que je dits qu’il falloit oster quelques coups desdites bottes, me repliqua pour scavoir de moy la vraye definition & secret, & me dit, Seigneur de S. Didier, pourquoy avez-vous dit que les responses, que je dy cy dessus, de plusieurs & de cinq bottes n’estoient par moy bien ne deuement respondues ? | | Voyant ce, ledit Fabrice, que je dits qu’il falloit oster quelques coups desdites bottes, me repliqua pour scavoir de moy la vraye definition & secret, & me dit, Seigneur de S. Didier, pourquoy avez-vous dit que les responses, que je dy cy dessus, de plusieurs & de cinq bottes n’estoient par moy bien ne deuement respondues ? | ||

| Line 398: | Line 398: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | Responding a second time the said Author, and saying that truly such above responses are worthless, at least the plural, as has been defined above, and will be shown | + | | Responding a second time the said Author, and saying that truly such above responses are worthless, at least the plural, as has been defined above, and will be shown as an example next. |

| Respond derechef ledit Autheur, & dit que veritablement telles susdites responses ne valloient rien, au moins la plurielle, comme a esté definy cy dessus, & sera monstré cy aprés comme par exemple. | | Respond derechef ledit Autheur, & dit que veritablement telles susdites responses ne valloient rien, au moins la plurielle, comme a esté definy cy dessus, & sera monstré cy aprés comme par exemple. | ||

| Line 404: | Line 404: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | If one would speak and interrogate a camp master and asked him how many times the enemy can come up to a camp, and he answered from several | + | | If one would speak and interrogate a camp master and asked him how many times the enemy can come up to a camp, and he answered from several, I would say that such a response would be uncertain and therefore impertinent, whereas when we ask such aforementioned questions to a camp master or any other masters, they must be certain of their responses. Otherwise they are not fit to rule or govern a camp nor a republic, since it is necessary to be sure of how many times the enemy can come up to a camp; to that end that we can put as many as a hundred, for the preservation and protection of it. |

| Si on disoit & interrogoit un maistre de camp, & on luy demandast de combien d’advenues l’ennemy peut venir sur un camp, & qu’il respondit de plusieurs : Je dy que telle response seroit incertaine, & par consequent n’est pertinente, attendu que quand on fait telle susdittes interrogations à un maistre de camp ou autres, tels doivent estre certains de leurs responses. Autrement ne sont dignes de regir ne gouverner un camp, ne republiques, attendu qu’il faut estre certain de combien d’advenues l’ennemy peut venir sur un camp, à celle fin qu’on y puisse mettre autant de centinelles, pour la conservation & garde d’iceluy. | | Si on disoit & interrogoit un maistre de camp, & on luy demandast de combien d’advenues l’ennemy peut venir sur un camp, & qu’il respondit de plusieurs : Je dy que telle response seroit incertaine, & par consequent n’est pertinente, attendu que quand on fait telle susdittes interrogations à un maistre de camp ou autres, tels doivent estre certains de leurs responses. Autrement ne sont dignes de regir ne gouverner un camp, ne republiques, attendu qu’il faut estre certain de combien d’advenues l’ennemy peut venir sur un camp, à celle fin qu’on y puisse mettre autant de centinelles, pour la conservation & garde d’iceluy. | ||

Revision as of 04:54, 15 February 2021

| Henry de Sainct Didier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1530s (?) Pertuis, Provence |

| Died | after 1584 Paris, France (?) |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Patron | Charles IX of France |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | Salvator Fabris (?) |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Middle French |

| Notable work(s) | Les secrets du premier livre sur l'espée seule (1573) |

| Translations | Traducción castellano |

| Signature | |

Henry de Sainct Didier, Esq. was a 16th century French fencing master. He was born to a noble family in Pertuis in the Provence region of France, son of Luc de Sainct Didier. Sainct Didier made his career in the French army, ultimately serving 25 years and seeing action in Piedmont, Italy from 1554 - 1555. He wrote of himself that he "lived his whole life learning to fight with the single sword" and eventually "reached a point of perfection" in his art. Apparently he became a fencing master of some renown, for in ca. 1573 he secured a royal privilege for a period of ten years for treatises on a number of weapons, including the dagger, single side sword, double side swords, sword and buckler, sword and cloak, sword and dagger, sword and shield (both rotella and targe), and greatsword. Unfortunately, only his treatise on the single side sword, titled Les secrets du premier livre sur l'espée seule ("Secrets of the Premier Book on the Single Sword") and printed on 4 June 1573, is known to survive; it seems likely that the others were never published at all.

Contents

Treatise

Illustrations |

by John Tse | |

|---|---|---|

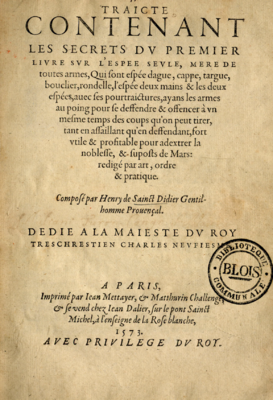

| THE TREATY CONTAINING THE SECRETS OF THE FIRST BOOK ON THE SWORD ALONE, MOTHER OF

all fencing, which includes dagger, cape, targe, buckler, rondel, two handed swords, and dual-wielding swords with portraitures, that have the weapon in hand for throwing strikes to defend and offend at the same time, both offensively and defensively, which is very useful and advantageous to become a skillful noble and disciples of Mars; written for art, order, and practice. Written by Provencal Gentleman Henry de Saint Didier. DEDICATED TO THE MAJESTY OF THE VERY CHRISTIAN KING CHARLES THE NINTH. PARIS, Printed by Jean Mettayer, and Matthurin Challenge, and is sold at Jean Dalier, on the Saint Michel bridge, to the sign of the White Rose, 1573. WITH PRIVILEGE OF THE KING. |

TRAICTE CONTENANT LES SECRETS DU PREMIER LIVRE SUR L’ESPEE SEULE, MERE DE

toutes armes, Qui sont espée dague, cappe, targue, bouclier, rondelle, l’espée deux mains & les deux espées, avec ses pourtraictures, ayans les armes au poing pour se deffendre & offencer à un mesme temps des coups qu’on peut tirer, tant en assaillant qu’en deffendant, fort utile & profitable pour adextrer la noblesse, & suposts de Mars : redigé par art, ordre & pratique. Composé par Henry de Sainct Didier Gentilhomme Provençal. DEDIÉ À LÀ MAJESTE DU ROY TRESCHRESTIEN CHARLES NEUVIESME. À PARIS, Imprimé par Jean Mettayer, & Matthurin Challenge, & se vend chez Jean Dalier, sur le pont Sainct Michel, à l’enseigne de la Rose blanche, 1573. AVEC PRIVILEGE DU ROY. | |

| LETTER TO THE KING.

SIRE, It does not please me to say how many are to be praised for those who strive, as they say, to help or even perfect the nature of reducing confusion to order, and in such a way that the face of it appeared rough, sick, and inaccessible; was made easy, accessible, and approachable by them. Even though the only harm that results from confusion and disorder, and among other things that are proper to the Gentlemen make them quite recommendable. Why would I turn my pen elsewhere to show you that to restore a battle that is in disarray, to put it back in its previous order, that a leader must be familiar with two things. To make certain decisions to save time and the place, where and when to stop the broken ranks and by a feint to divert the enemies, while the remaining troops reform and regroup. That decision cannot be acquired, even the reason for it cannot be believed without the second point that I the leader must make is truly necessary, which is having the experience of things, from which arises the aforementioned decision. SIRE, whoever wants to put art or doctrine back in order to avoid confusion lest in the end it will be wasted, decision is required, arising from the experience seen through the exercise of the said art which I have from having served in battle, very much for your grandfather as well as for your Majesty, for twenty years in Piedmont and elsewhere. I can justly attribute to myself having used my life to experience such arms, so much so that accumulating such evidence may have allowed me to to perfect the art and the practice of them. So seeing how confused and disordered they have been and are for today by everyone shown and practiced, have in my mind figured some model or idea, which as an example, I make sure that the order will not only be good so the art that consists of it will be completely restored, and will reach closer to perfection which I have longed for, both because of my powerlessness and extreme poverty (the enemy of good spirits) as well as to be prevented from serving you, kept hidden and buried among my papers in my office where the Muses after martial efforts made me, and hope that will keep me company. But I now have the desire to give you a most humble and pleasant service, far from the zeal that all my life I have had to fencing and to those who enjoy them and who make a profession of them have allowed little, that in this time when Mars gives us some respite, I have not been emboldened to present myself to your Majesty, something not worthy of such a great Monarch, but very suitable for the exercise of a common man, both in war and in peace, namely a treatise on the sword alone, mother of all fencing, that I wrote according to my opinions, which contains six points that I declare had never been organized and their proofs, both by reason and by effect attached to the end. SIRE, this here will contain this little work, which is like a summary or collection of the first book that I still have beside me. If your Majesty appreciates this, with God giving me the grace to live, I hope by means of your Majesty to later enlighten others. Therefore, you who is first and foremost to drive skill to the nobility, I thought you who is the patron of fencing worthy of this treatise, begging you most humbly where and when it would be reputed by other, to please take my ardent affection, which for a long time has been dedicated to offer you the most humble and pleasant service in payment for employing me for something of which this concerns, and I will be more than happy with endless opportunity and will, more than great to pray to the Sovereign Rector of the Universe to give you a long and happy life, and for the boundary of your Empire to only be the Sea.

|

EPISTRE AU ROY.

SIRE, Je ne m’amuseray à vous descrire combien sont à louer ceux qui taschans (comme l’on dit) ayder voire parfaire la nature, ont reduit les choses confuses en ordres, & de telle sorte que ce que de primeface sembloit rude, malaisé, & inaccessible, a esté par eux rendu aisé, traictable, & facile à aborder. Veu mesmement que le seul mal qui provient de la confusion & desordre des choses, et entre autres de celle qui sont propres aux Gentils-hommes les rendent assez recommandables. Parquoy tourneray ailleurs ma plume à vous remonstrer, que pour restaurer une bataille qui est en derroute, & la remettre en son pristin[1] ordre, il est besoin à un chef avoir deux choses bien familieres. Assavoir le jugement, pour gaigner le temps & le lieu, où & quand il faut arrester les rancs rompus & par une fainte cargue amuser les ennemis, pendant que le reste des troupes se rassemble & reserre. Lequel jugement ne se peut acquerir, voire la raison d’iceluy ne se peut croire sans le second poinct que je dy au chef estre fort necessaire, qui est l’experience des choses, de laquelle naist le jugement susdit. (SIRE) quiconque veut remettre quelque art ou doctrine en son ordre ou la tirer de la confusion, de peur qu’en fin elle ne se gaste, il est requis qu’il soit fourny de jugement, nay de l’experience veue par lexercice dudit art, ce que je ne dy sans cause car ayant fait service au faict des armes, tant à voz ayeux, comme aussi à vostre Majesté, par l’espace de vingtcinq ans en Piedmont & ailleurs. Je me puis justement attribuer avoir usé ma vie à l’expérience desdites armes, tellement qu’une si longue preuve peut avoir en moy engendré quelque perfection de l’art & pratique d’icelles. De sorte que voyant combien confusément, & avec mauvais ordre elles ont esté & sont pour le jourd’huy par tout le monde monstrées, & pratiquées, ay en mon cerveau figuré quelque patron ou idée, suivant laquelle comme exemplaire, je me fay fort que l’ordre en sera non seulement bon, ains l’art qui y consiste sera du tout restauré, & atteindra plus prés sa perfection, lequel j’ay par longs jours, tant à cause de mon impuissance & extreme pauvreté (ennemie des bons esprits) comme aussi pour estre empesché à vostre service, tenu caché & ensevely parmy mes papiers en mon cabinet, où les Muses aprés les efforts martiaux m’ont fait, & espere que me feront compaignie. Mais maintenant le desir que j’ay de vous faire treshumble & tresagreable service, loinct le zelle que toute ma vie j’ay eu aux armes, & à ceux qui les aiment, & qui en font profession, n’ont peu permettre, qu’en ce temps (ou Mars nous donne quelque relasche) je ne me sois enhardy presenter à vostre Majesté, chose non digne d’un tel & si grand Monarque, mais fort propre pour l’exercice d’un commun père, tant des armes que de paix, scavoir, un traicté sur l’espée seule, mere de toutes armes, que j’ay composé suivant mon petit jugement, dans lequel sont contenus six poincts, par cy aprés declarez, avec un ordre, non encores jamais usité, & la preuve d’iceluy, tant par raison que par effait attaché au bout. Voyla (SIRE) que contiendra, à present ce petit œuvre, qui est comme un sommaire ou recueil du premier livre que j’ay encores par devers moy. Parquoy si vostre Majesté prent quelque goust à cestuy cy, Dieu me donnant la grace de vivre, j’espere par le moyen de vostredite Majesté en mettre par cy aprés d’autres en lumiere, Donc cestuy (qui est le premier & principal pour adextrer la noblesse) j’ay pensé digne de vous, qui estes le protecteur, & soustien des armes, desquelles il traicte, vous suppliant plusque treshumblement, là & quand il seroit reputé autre vous plaise prendre mon ardente affection, laquelle de long temps a esté dediée à vous offrir treshumble, & tresagreable service, en payement m’employant à quelque chose, qui concerne iceluy, & je me tiendray plus que tresheureux avec perpetuelle occasion & volonté, plus que grande de prier le souverain Recteur de l’univers vous donner treslongue, & tresheureuse vie. Et pour borne de vostre Empire la seule Mer Occeane. | |

| Your most humble, and obedient servant, Henry de S. Didier, Provencal Gentleman. |

Vostre treshumble, & obeïssant serviteur, Henry de S. Didier, Gentilhomme Provençal. | |

| The following six points are required to understand and above all to best execute the secrets of the sword alone and all other weapons that are dependent.

The first is to know how many types of steps there are in the art of said fencing, to choose the best, and to give an explanation. |

S’ensuivent les secrets de ceste espée seule, & de toutes les autres armes qui en dépendent, pour lesquels entendre, & sur tout mieux executer, six poinct sont requis.

Le premier est combien de desmarches il y a en tout l’art desdites armes, & eslire la meillleure, & en donner raison. | |

| The second: how many guards and placements there are in the said fencing, to choose the best, and explain the reason. | Le second, combien de gardes, & situations y a ausdittes armes & eslire la meilleure, & par quelle raison. | |

| The third: how many strikes the aggressive enemy can offend the defender and to give the same explanation. | Le troisiesme, de combien de coups l’ennemy aggresseur peut offencer le deffendeur & en donner pareille raison. | |

| The fourth: how many clean targets can be listed for the said strikes on a person, both in attacking as well as in defending. | Le quatriesme, en combien de lieux propres se peuvent adapter lesdits coups sur la personne, tant en assaillant, qu’en deffendant. | |

| The fifth is namely to all those who make or will make the profession of teaching the said fencing: being able to defend and offend at the same time some strike or strikes that one can throw, and thus if they do not know how can they teach their disciples. | Le cinquiesme, sçavoir, à tous ceux qui font, ou feront, cy aprés profession de monstrer audites armes : soy deffendre & offencer à un mesme temps de quelque coup ou coups qu’on peut tirer, & par ainsi s’ils ne les sçavent comment les pourront ils monstrer à leurs disciples. | |

| By the sixth point, which is the last, we will see a great secret which is to decide which strike that the attacker can throw on the defender and will be given an explanation. | Par le sixiesme poinct, qui est le dernier on verra un grand secret, qui est de juger du coup que l’assaillant peut tirer sur le deffendeur & en sera donné raison. | |

| Regarding the first point, which is to know how many steps there are, I answer that there are no more than two because we have no more than two feet. | Quand au premier poinct, c’est à sçavoir combien il y a de desmarches, je respond qu’il n’y en a[2]que deux, par ce que nous n’avons que deux pieds. | |

| Some stand on the right foot, others on the left foot, however none give good reasons for one step or the other. But rest assured when he must take the sword in hand, knowing which of the said steps is best and most effective is necessary to execute the said art. | Les aucuns se tiennent sur le pied droict, les autres sur le pied gauche, toutefois en donnent bien peu de raisons, soy tenant sur l’une ou sur l’autre desmarche. Mais pour estre bien asseuré quand il est besoing de mettre l’espée au poing, faut sçavoir laquelle desdites deux desmarches est la meilleure & la plus certaine & superlative & en icelle comme dit est se faut tenir pour executer ledit art. | |

| As for me I favor with experience and proof that the step which is done by standing on the left foot initially in putting sword in hand is better and more effective, both for attacking and for defending. How little that our past demonstrators keep to either on one or the other, give very little reason. For this reason I will conclude that there are no more than two steps in all the art to start this off. | Quant à moy je soustiens avec l’esperience & preuve la desmarche qui se faict, soy tenant sur le pied gauche, pour la premiere foys, en mettant l’espée au poing, est la plus certaine & meilleure, tant pour l’assaillant que pour le deffendant. Combien que peu de noz encestres demonstrateurs s’y tiennent, & soy y tenant, tant sur l’un que sur l’autre, en donnent bien peu de raison. À ceste cause je concluray qu’il n’y a que deux desmarches en tout l’art, pour bien commencer iceluy. | |

| And in order to follow the experienced well and imitate them, of two good things one must choose the better, and of two bad things to avoid both if possible and if not at least avoid the worse, and in doing so I advise all said adherents to take the better of the said two steps, which is the one where you stand on the left foot initially with weapons in hand to make one of the said three drawings. | Et pour bien suivre les doctes, & les immiter, faut de deux choses bonnes choisir la meilleure, & de deux mauvaises, eviter les deux, si faire se peut, sinon la pire, & en ce faisant, je conseille à tous lesdits suppots de prendre la meilleure desdites deux desmarches, qui est celle qu’on se tient sur le pied gauche pour la premiere fois, en mettant les armes au poing, faisant un desdits trois desgainements. | |

| The following are the declaration and reasons of the said six points.

The first reason is that there are no more than two steps, the one on the right foot and the other on the left foot. |

Sensuivent cy aprés les declarations & raisons desdits six poincts.

La raison du premier est qu’il n’y a que deux desmarches, l’une se fait sur le pied droit, & l’autre sur le pied gauche. | |

| As for me I believe that the left foot is the best because one can be free to take more time and move farther than on the step of the right foot, and therefore to attack effectively and to defend better, as will be seen later in the section on the strikes. | Quant à moy je dy soy tenant sur le pied gauche est le meilleur, par ce que y estant on a liberté de prendre plus de temps, & grande course, que sur la desmarche du pied droict & par consequent de bien assaillir, & de beaucoup mieux se deffendre, comme se verra cy aprés à l’ordre des coups. | |

| This is the reason why we know that stepping with the left foot is better than that of the said right foot. | Voyla la raison pourquoy la desmarche qu’on faict sus ledit pied gauche, est meilleure que celle dudit pied droict. | |

The second is knowing how many guards and placements there are of said fencing. I say that there are no more than three guards and three principal placements.

|

La seconde est sçavoir combien de gardes & situations il y a ausdites armes. Je dis qu’il n’y a que trois gardes, & trois assituations principalles.

| |

| Some demonstrators, when they define the said guards, start at the top. As for me, I start on the bottom, since everything begins at the foundations. For example, learned people do not start by teaching advanced level sciences; neither do masons start on the buildings when they construct houses; they start on the foundations. And so I start on the low guard which is the foundation to guarding well. | Les aucuns demonstrateurs, quand ils definissent lesdites gardes, accommencent à la haute. Quant à moy, je commence à la basse, attendu que toutes choses se commencent aux fondements. Comme pour exemple, les gens doctes ne commencent à monstrer les sciences aux hautes, ne les maçons quand ils viennent à commencer à bastir les maisons, ne commencent pas à la tuille, ains au fondement. Et par ainsi je commence à la basse, qui est le fondement qu’on doit bien garder. | |

| It is true that this low guard can itself generate two other lows: one on the right side and the other on the left side. | Bien est vray, que de ceste garde basse, s’en peut engendrer deux autres basses, l’une est sur le costé droit, l’autre sur le costé gauche. | |

| This one which is the right side leaves the natural form and domain of the said original one and participates on the right side. | Celle qui se fait sur le costé droit, elle se faict laissant la nature, & proprieté de leurditte mere, & participer sur le costé droict. | |

| The one which is the left side also leaves the natural form of its said originator and participate on the left side. | Celle qui se fait sur le costé gauche, elle se fait aussi laissant la nature, & estre de saditte mere, & participer du costé gauche. | |

| These said two guards created by the said low is often done for drawing some ignorant strikes who makes either a high right-hand or a high thrust; because we cannot use another strike, which we easily can trick and hit the attacking enemy who would be surprised, and would not consider the mistake that could come from being on the said two imagined guards. But the original low guard is the most effective, so therefore there are no more than three guards as stated. | Cesdites deux gardes engendrées de ladite basse, elle se font bien souvent pour attirer quelque coup des ignorans, qui fera un maindroict, ou un estoc haut ; car autre coup on ne peut, sur lesquels facilement on peut attraper & toucher l’ennemy assaillant qui sera estourdy, & ne considerera l’accident qui peut venir, estant sur sesdittes deux gardes faintes. Mais la garde basse leur mere est la plus certaine, de sorte qu’il n’y a que trois gardes, comme dit est. | |

The third point that one must know is how many strikes the attacking enemy can offend the defendant. As for me I say that the attacker and defendant can offend with no more than three strikes. Which are:

|

Le troisiesme poinct est qu’il faut scavoir de combien de coups l’ennemy assaillant peut offencer le deffendant. Quant à moy, je dy que l’assaillant & deffendant ne se peuvent offencer que de trois coups. Qui sont,

| |

| It is true that they can be multiplied in six clean targets on the human body, which must be kept well, as well as a good tennis player must keep the es[3] well so that the ball of the opposing party does not touch it. So too must a good fencer be careful that one of the three strikes do not hit the six targets that can be adapted as stated, which will be seen later. | Bien est vray qu’ils se peuvent multiplier en six lieux propres sur corps humain, qui faut bien garder, tout ainsi qu’un bon joueur de paulme faut qu’il garde bien l’es,[4] que lesteu[5] de partie adverse ne le touche. Aussi faut il qu’un bon tireur d’armes garde bien qu’un desdits trois coups ne touchent aux six lieux ausquels se peuvent adapter comme dit est, dont se verront cy apres. | |

| It should be noted that fencing and tennis are related, and whoever knows how to play tennis well will be able to strike well easily and early in fencing. | Faut noter que les armes, & la paulme sont cousins germains, & qui scaura bien jouer à la paulme, facilement & tost scaura bien tirer des armes. | |

| The fourth point is that attacking and defending can offend with no more than three said strikes: it is true that they can be multiplied and adapted as have been promised above at six clean targets on a person, either in attacking or in defending, and whoever knows the means to defend and offend with the said three strikes at the same time when multiplied can know a hundred strikes, which is above and will be defined later. | Le quatriesme poinct est, que l’assaillant & deffendant ne se peuvent offencer que desdicts trois coups : bien est vray qu’ils se peuvent multiplier, & adapter comme avons promis si dessus en six lieux propres sur la person ne, soit en assaillant, ou en deffendant, & qui scaura le moyen de soy deffendre, & offencer à un mesme temps, comme ce peult, desdicts trois coups, qui sont cy dessus & seront si aprés definis, estant multipliez il en scaura cent. | |

The following are the names of the said six clean targets where one can and must throw the said three strikes which are:

|

Sensuivent les noms desdits six lieux propres, ou fault, & se peuvent tirer les susdicts trois coups, c’est à dire,

| |

| The first strike and target is a low right-hand to the left leg of the defendant. | Le premier coup & lieu, est un maindroict, de bas au jarret gauche du deffendant. | |

| The second strike and target is a low backhand to the right leg of the defender if he is right; and if he left, it will be done at his left leg. | Le second coup & lieu, est un renvers, de bas au jarret droict du deffendeur, s’il est droictié, & s’il est gauché, se fera au jarret gauche. | |

| The third target, the said right-hand, is multiplied once from above on the left side of the defendant. | Le troisieme lieu, ledict maindroict est multiplié une fois d’hault sur le costé gauche du deffendant. | |

| The fourth target is a high backhand at the right shoulders of the defendant, multiplied once. | Le quatriesme lieu est un renvers d’hault sur l’espaulle droicte du deffendant, estans multiplié une fois. | |

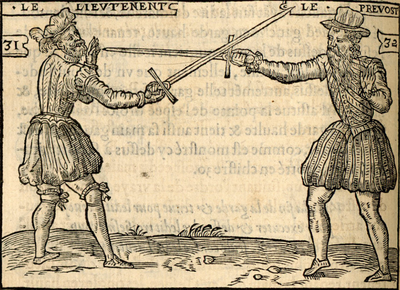

| The fifth target is the left nipple, to which the attacking Lieutenant throws a thrust to the Prevost, which is the said third strike. | Le cinquiesme lieu, est le tetin gauche, auquel le Lieutenent assaillant tirera un estoc au Prevost, qui est ledict troisieme coup. | |

| The sixth and final target, is the right nipple of the said Prevost to which the Lieutenant throws a thrust, which is the said third strike, being multiplied once like the right-hand and the backhand. | Le sixiesme & dernier lieu, est le tetin droict dudict Prevost auquel le Lieutenent tirera un estoc, qui est ledict troisiesme coup, estant multiplié une fois comme ledict Maindroict, & Renvers. | |

| The end of the said six targets, which is also the end of the fourth point. | Fin desdicts six lieux, qui est aussi la fin du quatriesme poinct. | |

| The fifth is that it is necessary to be defending and offending at the same time with the said three strikes, adapting and throwing at the said targets, both in attacking and in defending observing the time that is required. All of which will then be shown and declared at length in the instruction of the sword alone. | Le cinquiesme est, qu’il fault sçavoir soy deffendre & offencer à un mesme temps desdits trois coups, adaptez & tirez aux susdits lieux, tant en assaillant qu’en deffendant observant bien le temps qui est requis. Dont le tout sera cy aprés monstré & declaré au long à l’instruction de ceste espée seule. | |

| The sixth and last point is one of the good ones that is required to know in all of the art, which is to decide which strikes could be thrown, both in attacking and in defending, because being able to decide easily will be provide a remedy; otherwise it will be hard. And to do this we must look at the sword point and never lose sight of it and in doing so, we will easily decide which strike we will find to defend and offend at the same time, as promised. | Le sixiesme & et dernier poinct est un des bons qui soit requis de sçavoir en tout l’art, qui est juger du coup qui se peut tirer, tant en assaillant qu’en deffendant, car le jugeant facilement on y trouvera son remede, autrement non. Et pour ce faire faut regarder la pointe de l’espée, & ne la perdre jamais de veue, & en ce faisant, facilement on jugera du coup, le jugeant on trouvera moyen de soy deffendre & offencer, comme j’ay promis à un mesme temps. | |

| The reason to decide the said strikes is that the outside, which is the said sword point, directs and leads by the inside, which is the will and knows not the sword point, which is the outside, to be so skillful as the observation, and therefore the observation of deciding the strike and gaining time. The observation and the gained time could succeed and precede the said outside, which is the said strikes that the Lieutenant could throw at the defending Prevost, and there we can find the remedy. | La raison pour juger d’un desdits coups est que l’exterieur, qui est ladite pointe de l’espée, se conduit & meine par l’interieur, qui est la volonté, & ne scauroit la pointe de l’espée, qui est l’exterieur, estre si habile que la veue, & par consequent la veue fait juger du coup, & gaigner le temps. La veue & le temps gaignées peuvent succeder & prealler[6] ledit exterieur, qui est l’un desdits coups que le Lieutenant peut tirer sur le Prevost deffendant, & par là on peut trouver son remede. | |

| This is the end and the declaration of the sixth and last point, which is truly necessary to know in order to understand this weapon and everything else on the same subject.

Following the aforementioned six points, someone named Fabrice and Jules came to see me once with some of his people, because they had heard talks of me, and they were told that I was writing a book on fencing and that I had dedicated it to the King. Avaricious and willing to know even more of the said fencing than they knew, they begged me to show them the said book, which I refused until his said Majesty had seen it, and then seeing their good will knowing that they had not come to chatter to try to see the contents of the said book, I am excited to discuss with them some points contained in the said fencing and asked them certain questions, which we will be able to see later, along with their responses, by which we can easily judge who best touches the goal of the true definition and demonstration of said fencing. |

Voicy la fin & declaration du sixiesme & dernier poinct, qui est necessaire de scavoir à tous, pour l’intelligence de ceste arme, & de toutes les autres qui sont du mesme subjet.

Suyvant les dessusdits six poincts, un nommé Fabrice[7] & Jule, me vindrent une fois voir, avec quelques uns de leur païs, par ce qu’ils avoient ouy parler de moy, & leur avoit on dit que je composois un livre sus les armes & que je l’avois dedié au Roy. Eux cupides & volontaires, de sçavoir encores plus ausdites armes qu’ils ne sçavoient, me prierent de leur monstrer ledit livre, ce que je leur fis refus, (jusques à ce que ladite Majesté l’eust veu) & alors voyant leurs volontez bonnes, & qui n’estoient venus à moy pour eux jacter, ains pour tascher à voir le contenu dudit livre, cela m’esmeut de discourir avecques eux quelques poincts contenuz ausdites armes, & leurs fis certaines interrogations, qu’on pourra voir cy aprés avec leurs responses, par lesquelles on pourra facillement juger qui touche mieux au but de la vraye definition, & demonstration desdites armes. | |

| And so I come attacking the said Fabrice first, and say to him, "Sir Fabrice, before discussing presently with you about none other than the said fencing, I want to know how many strikes the attacking enemy can offend the defendant. And yet with your grace, I pray you tell me." | Et alors je me viens atacquer premierement audit Fabrice, & luy dis Seigneur Fabrice, avant que tirer à present avec vous, ny avec autre ausdites armes, je veux sçavoir de combien de coups l’ennemy assaillant peut offencer le deffendant. Et pourtant, de grace vous prie, le moy dire. | |

| And so responding the said Fabrice said that there are many blows, blows in Neapolitan is what is called strikes in French. And hearing this response uttered by the said Fabrice the said Author answered that this answer is infinite and vague. Responding again the said Fabrice asked, "Sir why do you say that my answer is impertinent?" | Et alors respondit ledit Fabrice & dit, de plusieurs bottes, bottes en napollitain vaut autant à dire que coups en françois. Et encores oyant ledit Autheur cette response proferée par ledit Fabrice, estre infinie et incertaine. Respondit encore ledit Fabrice & dist seigneur pourquoy dictes vous que ma reponse est impertinente. | |

| Responding the said Saint Didier says that every answer with infinite points are vague, so to this said answer of many blows from the said Fabrice is impertinent. | Respond ledit de Sainct Didier & dit que toute response infinie n’a point de certitude, à ceste cause ladite response qu’a ledit Fabrice respondu de plusieurs bottes est impertinente. | |

And so the said Fabrice saw that I was shaking my head, meaning that he did not answer me pertinently. The said Fabrice comes to his senses and gives another answer and says that there are five blows that the attacking enemy could offend the defendant: And again I told him to define them, and this time he says:

And hearing this answer uttered by the said Fabrice when he said the above five Blows. |

Et alors ledit Fabrice voyant que je remuois la teste, signifiant par là qu’il ne m’avoit respondu pertinement. Va ledit Fabrice un petit reprendre ses esprits, & feit autre response, & dit que de cinq bottes l’ennemy assaillant pouvoit offencer le deffendant : Et encores je luy dis definissez les, & à ceste heure il dit d’un,

Et oyant ceste responce proferée par ledit Fabrice, quand il dit cy dessus de cinq Bottes. | |

| So the said Author, without pause responded to him and said that these two answers that he responded is wrong, whereas one is a response that is plural, the other is singular. The plural is worthless given the reason above; the singular which is when he said above about there being five blows is also impertinent. The reason is because there are too many and thus some must be removed. | Alors le dit Autheur, sans bien peu d’intervalle luy respondit & dit que telles responses contenoient deux chefs, par lesquels il avoit mal respondu, attendu qu’il y a une response qui est plurielle, & l’autre singuliere. La plurielle ne vaut rien, la raison est cy dessus donnée, la singuliere qui est quand il a dit cy dessus de cinq bottes n’est aussi pertinente. La raison par ce que il en y a trop & par ainsi en faut oster. | |

| The said Fabrice, seeing that I said that we must remove some of the strikes of the said blows, replied to know of my true definition and secret and said to me, "Sir S. Didier, why have you said these responses that I said above that of the many blows and of the five blows are incorrectly answered by me?" | Voyant ce, ledit Fabrice, que je dits qu’il falloit oster quelques coups desdites bottes, me repliqua pour scavoir de moy la vraye definition & secret, & me dit, Seigneur de S. Didier, pourquoy avez-vous dit que les responses, que je dy cy dessus, de plusieurs & de cinq bottes n’estoient par moy bien ne deuement respondues ? | |

| Responding a second time the said Author, and saying that truly such above responses are worthless, at least the plural, as has been defined above, and will be shown as an example next. | Respond derechef ledit Autheur, & dit que veritablement telles susdites responses ne valloient rien, au moins la plurielle, comme a esté definy cy dessus, & sera monstré cy aprés comme par exemple. | |

| If one would speak and interrogate a camp master and asked him how many times the enemy can come up to a camp, and he answered from several, I would say that such a response would be uncertain and therefore impertinent, whereas when we ask such aforementioned questions to a camp master or any other masters, they must be certain of their responses. Otherwise they are not fit to rule or govern a camp nor a republic, since it is necessary to be sure of how many times the enemy can come up to a camp; to that end that we can put as many as a hundred, for the preservation and protection of it. | Si on disoit & interrogoit un maistre de camp, & on luy demandast de combien d’advenues l’ennemy peut venir sur un camp, & qu’il respondit de plusieurs : Je dy que telle response seroit incertaine, & par consequent n’est pertinente, attendu que quand on fait telle susdittes interrogations à un maistre de camp ou autres, tels doivent estre certains de leurs responses. Autrement ne sont dignes de regir ne gouverner un camp, ne republiques, attendu qu’il faut estre certain de combien d’advenues l’ennemy peut venir sur un camp, à celle fin qu’on y puisse mettre autant de centinelles, pour la conservation & garde d’iceluy. | |

| And to answer and conclude to what was said above we need to know how many strikes the enemy can offend us, to know how to remedy and defend our body and honor, like a camp master who has a camp of a hundred or fifty thousand men because it is in our specific interest. As for me, I say with the learned that what can be done with less is better than what can be done with more. Because of this I will remove two of the said five blows that Fabrice have because I say they are redundant, which is Fendente and Imbrocatta, and so remain no more than three, which is defined above and will be next. | Et pour respondre & conclure, à ce que dessus est dit nous avons autant de besoin de scavoir de combien de coups l’ennemy nous peut offenser, pour scavoir à iceux remedier & deffendre nostre corps & honneur, comme un Maistre de camps qui a un camp de cent ou cinquante mille hommes car c’est nostre interest particulier. Quant à moy je dis avec les doctes que ce qui ce peut faire avec peu est meilleur que ce qui ce fait avec beaucoup. À ceste cause j’osteray deux desdites cinq bottes que tient le dit Fabrice par ce que je les dy estre superflus, qui sont Fendant, & Imbronccade, & n’en demeurera plus que trois, qui sont cy dessus par moy definis, & seront cy apres. | |

| The following is the declaration and reason why the said Author removes the said Fendente against the opinion of the said Fabrice and Jules and many others, who nevertheless always put them in the list of the said strikes.

The reason why I first removed the said Fedante is because it cannot actually be done. Because any Fendente that is true must hold and must not leave the top and middle of the thing you want to slash. I know of no man, as long as I have practiced in all the sciences or arts, that having a sword in hand, cutlass, or another weapons that can properly slash with whatever strikes that he can do, will not participate either on one side or the other, which gives up the middle. And yet if such a strike is thrown in the right side, is not Fedente but is Right-Hand, and if kept on the left side, it is not Fendente but will be Backhand. |

S’ensuit la declaration & raison cy aprés pourquoy ledit Autheur oste ledit Fendant, contre l’opinion desdits Fabrice & Julle, & plusieurs autres, ce neantmoins de tout temps les ont mis & mettent au ranc desdits coups.

La raison pourquoy j’oste premierement ledit Fendant est par ce qu’il ne se peut faire proprement. Car tout Fendant qui est propre faut qu’il tienne & ne laisse le sommet & meillieu de la chose qu’on veut fendre. Or est il que je ne sache homme, tant soit il exercé en toutes sciences ou arts, qu’ayant une espée au poing, couttellats, ou autres armes à ce propres à fendre, que quelque coup qu’il puisse faire, ne participe ou d’un costé ou d’autre, laissant le meillieu. Et pourtant si tel coup tiré participe du costé droict, n’est Fendant, ains Maindroict, & s’il tient plus du costé gauche, n’est aussi Fendant, mais sera un Renvers. | |

| This is the reason why the said Fendente is removed by the said Author: of the number of the said blows that were held by the said Fabrice, and in it remains no more than four. | Voyla la raison pourquoy ledit Fendant est osté par ledit Autheur : du nombre desdites cinq bottes que tient le susdit Fabrice, & n’en demourera plus que quatre. | |

| This is also why the author declared that he removed the said Imbrocatta from the number of the said five blows.

The reason is because Stoccata and Imbrocatta are both the same, like grapejuice green and green grapejuice, which are also the same. Because by asking for one or the other, one will never admit that they are the same. As such, a Stoccata and an Imbrocatta are the same thing since it is only the point that differs. And by removing the Fendente and Imbrocatta as stated, there will remain no more than three of the said strikes that are above declared in the said third point. |

Cy aprés est aussi declaré pourquoy ledit autheur oste ladite Imbronccade du nombre desdites cinq bottes.

La raison, par ce qu’Estoccade & Imbronccade, c’est tout un, comme verjus verd, & verd verjus,[8] c’est aussi tout un. Car en demandant l’un ou l’autre, on ne vous apportera jamais que le mesme. Aussi une Estoccade, & une Imbronccade, c’est une mesme chose, attendu que cest tousjours la pointe qui faict la faction. Et par ainsi ostant comme dit est, le Fendant & imbronccade, n’en demoureront plus que lesdits trois coups qui sont cy dessus declarez audit troisiesme poinct. | |

| Here is the end of every requirement to know and to understand for whoever wants to be skillful in the said fencing.

To truly understand the said fencing and discover the art, order and pratice of it, he must imagine three personas: the first is the Author, the second the Lieutenant, the third the Prevost. The Author will describe all of the orders that the said Lieutenant and Prevost must follow in the art of the sword alone, which follows next and is now commencing. END. |

Voicy la fin de tout ce qui est requis & necessaire de scavoir & entendre à un chacun, qui veut estre adroit ausdites armes

Pour bien donner entendre lesdites armes, & discourir de l’art, ordre & pratique d’icelle, il a fallu feindre trois personnages : lLe premier c’est l’Autheur, le second le Lieutenant, le troisiesme le Prevost. Par l’Autheur sera descrit cy aprés tout l’ordre que doit tenir ledit Lieutenant & Prevost en l’art de ceste espée seule, laquelle s’ensuit cy aprés & le commencement d’icelle. FIN. | |

| To the King.

By the Gentleman Stephen of Guette. SIRE, it is all but certain that men are made |

Au Roy.

Par Estienne de la Guette, gentilhomme. SIRE, il est tout certain que les hommes sont faits | |

| Sonnet to the author by Sir L'Aigle.

I already see, Sainct Didier, the intuition of your beautiful book |

Sonnet à l’auteur, par Monsieur de l’Aigle.

Je voy ja, Sainct Didier, au flair de ton beau livre | |

Illustrations |

by John Tse | |

|---|---|---|

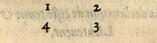

| The following is how one must be planted to put the sword in hand, both in time of peace and in times of war, with the steps, guards, drawings, and placements required in this art, which is truly necessary to those who wish to practice the said fencing.

Four footprints are placed below the feet of the Lieutenant and Prevost which are marked number 1, and another 2, and another 3, and another 4, which serves the Lieutenant and Prevost and everyone else to teach how one must skillfully make all the steps, drawings, guards, and placement of the weapons well as imagined in this rectangle. |

Sensuit cy aprés comment il se fault planter pour bien mettre l’espée au poing, tant en temps de paix qu’en temps de guerre, avec les desmarches, gardes, desgainements, & assituations requises en cest art, qui sont fort necessaires à ceux qui veulent exercer lesdites armes.

Cy aprés quatre semelles mises & assituées au dessous des pieds du Lieutenent & Prevost, dont à l’une est cotté en chiffre 1, & à l’autre 2, & à l’autre 3, & l’autre 4, qui servent au Lieutenent & Prevost, & à tous autres, monstrans comment il faut bien & dextrement faires toutes les desmarches, desgainements, gardes, & assituations aux armes faignant un tel quadriangle, | |

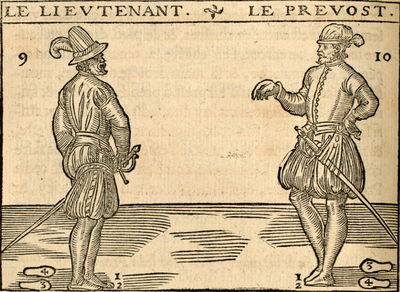

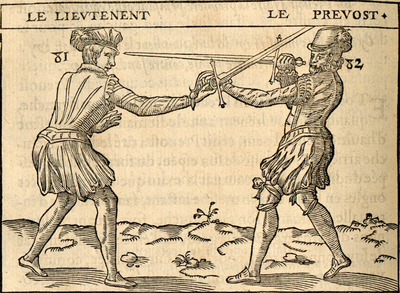

| The position and general plan to make the first step and the first, second, and third drawings, which is necessary to know both for the attacking Lieutenant as well as for the defending Prevost and all those who love fencing, carrying the sword on their side.

Here follows the declaration of this position and plan for the Lieutenant. And to do this the Lieutenant first must have the feet together thus placed, keeping the left foot in the footprint marked close to number 1 and the right foot in the other footprint where it is marked number 2, keeping the right hand on the sword hilt and the left hand on the scabbard of the sword, showing that he wants to teach the Prevost how this must be made, as shown above at the portraiture of the said Lieutenant marked number 1 behind the hat. The end of what the said Leiutenant needs to do. The declaration of the plan and position of the said Prevost. And to do this the said Prevost needs to have the feet together, keeping the left foot in the footprint marked above at number 1 and the right foot in the other footprint marked above at number 2, keeping the right hand on the sword hilt and the left hand on the scabbard, showing that he is ready to make the necessary first step, as shown by the said Lieutenant, which is the first, second, and third drawings, as marked above at its portraiture and figure in number 2. This is the end and declaration of the said first plan for the said Prevost. |

Tenue & plan general, pour faire la premiere desmarche & le premier, second, & tiers desgainements, qui sont necessaires scavoir, tant pour le Lieutenent assaillant, que pour le Prevost deffendant, & à tous autres qui aiment les armes, portans espée en leurs costez.

Icy ensuit la declaration de ceste tenue & plan pour le Lieutenent. Et pour ce faire faut que cestuy premier Lieutenant soit à pied joinct, ainsi placé, tenant le pied gauche dans une semelle, où il y a cotté auprés en chiffre 1, & le pied droict dans l’autre semelle, où il y a auprés cotté en chiffre 2, tenant la main droicte à la garde de son espée, & la main gauche au fourreau de l’espée, monstrant par cela qu’il veut monstrer au Prevost comment il faut qu’il face par cy aprés : comme est monstré cy dessus à la pourtraicture dudit Lieutenent cotté en chiffre au derriere du chappeau 1. La fin de ce que doit faire à present ledit Lieutenent. La declaration du plan & tenue pour ledit Prevost. Et pour ce faire est besoin que ledit Prevost soit à pied joinct, tenant le pied gauche dans une semelle où est cotté au dessous icelle en chiffre 1, & le pied droict dans une autre semelle où est cotté au dessus en chiffre 2, tenant la main droicte à la garde de l’espée, & la main gauche au fourreau d’icelle, monstrant qu’il est prest à faire ce que est necessaire en ceste premiere desmarche, comme luy a monstré ledit Lieutenent, qui est le premier, second, & tiers desgainement, comme est cotté cy dessus à sa pourtraiture & figure en chiffre 2. Voyla la fin & declaration dudit premier plan pour ledit Prevost. | |

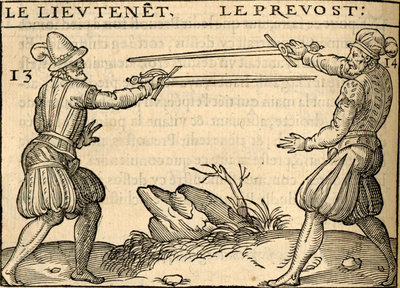

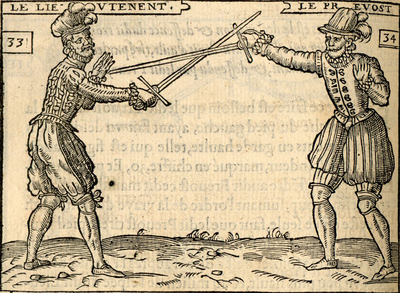

| The guard to execute the said first step and the first and second drawings for the Lieutenant and Prevost.

And to do the said first step for the Lieutenant, he must have the feet together as shown above at the first portraiture marked number 1, and being there he must pull the right foot back on the footprint marked number 3 below, which is the first step. And at the same time, put the sword in hand, for the said first drawing carry the sword hilt higher than the right shoulder, placing the sword point straight at the left nipple, content 1, keeping the left hand right of the face, as shown above at the portraiture of the said Lieutenant marked number 3 behind the collar. This is the end of the first drawing for the said Lieutenant. Following is the second drawing for the said Lieutenant. For the second drawing for the Lieutenant, he must have the feet together like so as shown above at the first portraiture marked number 1. And to execute this said second drawing, he must move the right foot a little apart in the air, remove it from the footprint marked 2, carrying the sword hilt, drawing it higher than the shoulder, and the placement of this as above content 1. And in an instant pass the sword above the head, extending strongly the arms, keeping the sword hilt higher than the right shoulder, and placing the sword point at the left nipple of the Prevost, as shown in the said portraiture at number 3. The end of the second drawing for the said Lieutenant. This is the declaration for the first and second drawing for the said Prevost, which is to know how to put the sword in hand as taught by the said Lieutenant. And to do this, the said Prevost has to remember how he placed his said first plan as shown above in number 2, which is with the feet together, and from there the said Prevost must make the said first drawing by pulling the right foot on footprint 2 back to the footprint marked number 3, which is also the first step, and at the same time put the sword in hand, carrying the sword hilt higher and a bit farther than the right shoulder, placing the sword point straight at the left eye to be on high guard, and keeping the left hand right of the left nipple to deflect the sword point of the said Lieutenant if by fortune he wants to advance further, as shown above in the portraiture marked number 4. This is the end of the first drawing of the said Prevost. The following is the second drawing for the Prevost. And to effectively execute the second drawing, the Prevost must have the feet together as shown in the said portraiture marked number 2, and from there the said Prevost must pull the right foot out of the footprint where it was in number 2, putting it down a bit, and making the said second drawing which is that he must carry the sword hilt in middle guard, and the point straight at the left nipple. And to begin the third drawing, he must pass the sword above the head, extending strongly the arms, and carrying the sword hilt higher and a bit farther than the right shoulder, placing at the same time the sword point straight at the left eye of the said Lieutenant, and the left hand is kept right of the left nipple, as shown above in the first drawing and as shown at the said portraiture marked behind the back of the person marked number 4. The end of the first and second drawings for the said Prevost. After having shown this said first plan above, being to make the first and second drawings for the Lieutenant and the Prevost, stay for the demonstration of the third drawing, after which one will be able to see the guard and position to and to be able to execute and do it. |

Garde pour faire, & executer ladite premiere desmarche, premier & second desgainement, pour le Lieutenent & Prevost.

Et pour faire ledit premier desgainement pour ce Lieutenent, est besoing qu’il soit à pied joinct, comme est monstré cy dessus à sa premiere pourtraiture, cotté en chiffre 1, & y estant, faut qu’il tire le pied droict arriere sur la semelle où est cotté au dessoubs d’icelle en chiffre 3, qui est pour la premiere desmarche. Et à un mesmes temps, mettre l’espée au poing, pour ledit premier desguainement portant la garde de l’espée aussi haut que l’espaule droite, assituant la pointe de l’espée droit le tetin gauche, contant 1, tenant la main gauche droict le visage, comme est monstré si dessus à la pourtraiture dudit Lieutenant, cotté en chiffre au derriere du col 3. Voyla la fin du premier desgainement pour ledit Lieutenent. Sensuit le second desgainement pour ledit Lieutenent. Pour le second desgainement pour ledict Lieutenent, faut qu’il soit ainsi placé à pied joinct, comme est monstré cy dessus, à la premiere pourtraiture, cotté en chiffre 1. Et pour executer cedit second desgainement est besoin, & faut qu’il tienne le pied droit un peu à quartier en l’air, l’ostant de la semelle où est cotté 2, portant la garde de l’espée, la desgainant aussi haute que l’espaule & la situation d’icelle comme dessus contant 1. Et à un instant passer l’espée par dessus la teste, estendant fort le bras, allant pauser ladicte garde de l’espée aussi haute que l’espaulle droitte, assituant la pointe de l’espée au tetin gauche du prevost, comme est cotté à sadite pourtraiture en chiffre 3. La fin du second desgainement pour ledit Lieutenent. Cy aprés est declaré le premier & second desgainement pour ledit Prevost, qui est pour scavoir bien mettre les armes au poing, comme luy monstre ledit Lieutenent. Et pour ce faire fault que ledit Prevost se souvienne comme il estoit placé cy dessus à sondit premier plan cotté en chiffre 2, qui est à pied joinct, & y estant, faut que cedit Prevost, pour faire cedit premier desgainement qu’il tire le pied droict qu’il a sur la semelle cottée 2, arriere sur la semelle où est cotté en chiffre 3, qui est aussi pour la premiere desmarche, & à un mesme temps mettre l’espée au poing, portant la garde de l’espée aussi hault, & un peu d’avantage que l’espaulle droict assituant la poincte de l’espée, estant sur ceste garde haulte, droit l’œil gauche, tenant sa main gauche droict son tetin gauche pour détourner la pointe de l’espée dudit Lieutenent, si par fortune la vouloit advancer davantage, comme est monstré cy dessus à sa pourtraiture cotté en chiffre 4. Voyla la fin de ce premier desgainement pour ledit Prevost. Sensuyt pour iceluy Prevost le second desgainement. Et pour bien executer le second desgainement, fault que ledit Prevost soit à pied joinct, comme est monstré a sadite pourtraiture, cotté en chiffre 2, & y estant, faut que cedit Prevost tire le pied droict hors de la semelle où il estoit, qui est cotté en chiffre 2, la posant un peu à cartier, faisant ledit second desgainement, qui est qu’il faut porter la garde de l’espée en garde moyenne, & la pointe droit le tetin gauche. Et pour commencer ce tiers desgainement, faut passer l’espée par dessus la teste, estendant bien fort le bras que tient icelle, & porter la garde de l’espée aussi haut, & un peu davantage que laditte espaulle droicte, assituant à un mesme temps la pointe de l’espée droict à l’œil gauche dudit Lieutenent, & la main gauche la tenant droict son tetin gauche, comme est dit cy dessus au premier desgainement, & comme est monstré à sadite pourtraiture cotté en chiffre au derriere du dos 4. La fin du premier & second desgaignement pour ledit Prevost. Aprés avoir monstré cy dessus, estant sur ledit premier plan, pour faire le premier & second desgainement pour le Lieutenent & Prevost, reste à monstrer le troisiesme desgainement, dont cy aprés on verra la garde & tenue pour executer & faire iceluy. | |

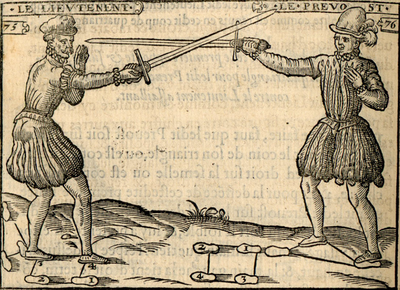

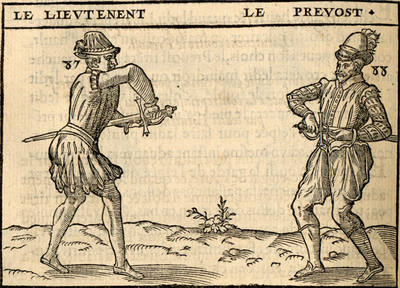

| Guard and position for commencing to make the third drawing for the demonstrating Lieutenant at the defending Prevost.

This third drawing for the Lieutenant is to be done with the feet together, as stated above and shown at the said general plan, keeping the left foot on the footprint marked number 1 below, and the right foot at the footprint marked 2, and in order to effectively start this said third drawing, the said Lieutenant must remove the right foot from the said footprint marked 2 and carry it forward in the air, making the first drawing, which can be seen above at its place in content 1, and while keeping the foot in the air, turn the sword hilt, the back of the hand down and the nails high, placing the sword point straight at the belly, keeping the left hand behind, as shown above at the portraiture marked number 5 behind the hat. The end of the start of the said third drawing for the Lieutenant. The third drawing for the said Prevost starts by having the feet together as shown above in the plan of the said Prevost marked number 2, keeping the left foot in the footprint marked near number 1, and the right foot in the other footprint marked 2, and to start and do the said third drawing, the Prevost must put the right foot which is on the footprint marked 2 a bit up in the air. And doing the first drawing that has been made by the said Prevost above in content 1. And to complete this said drawing, he must turn the nails on the sword hand upwards, content 2, placing the sword point straight at the eyes, keeping the left hand behind, as shown above at the portraiture and figure marked number 6 behind the bonnet. This is the end of the start of the said third drawing for the said Prevost. |

Garde & tenue pour commencer à faire troisiesme desgainement pour le Lieutenent demonstrateur, au Prevost deffendeur.

Ce troisiesme desgainement pour ce Lieutenent, il se fait estant à pied joinct, comme est dit cy dessus, & monstré audit plan general, tenant le pied gauche sur la semelle où est cotté au dessous en chiffre 1, & le pied droict à la semelle où est cotté 2, & pour bien commencer cedit troisiesme desgainement, faut que ledit Lieutenent oste le pied droict de ladite semelle, où est cotté 2, & la porter en avant en l’air, faisant le premier desgainement, voy en son lieu cy dessus, contant un, & tenant tousjours le pied en l’air, tournant la garde de l’espée, le dessus de la main en bas, & les ongles en haut, assituant la pointe de l’espée droict au ventre, tenant la main gauche derriere, comme est monstré cy dessus à sa pourtraiture cotté en chiffre au derriere du chappeau 5. La fin du commencement dudit troisiesme desgainement pour le Lieutenent. Le troisiesme desgainement pour ledit Prevost, il se commence & se faict estant à pied joinct, comme est monstré cy dessus au plan dudit Prevost, cotté en chiffre 2, tenant le pied gauche dans une semelle, où est cotté en chiffre auprés 1, & le pied droict dans une autre semelle où est cotté 2, & pour commencer & faire ledit troisiesme desgainement faut que le Prevost mette le pied droict qui est sur la semelle cotté 2 un peu à cartier en l’air. Et faisant le premier desgainement qu’a faict ledit Prevost cy dessus contant 1. Et pour parachever cedict desgainement fault tourner la main de l’espée les ongles en hault, contant 2, assituant la pointe de l’espée droit à la veue, tenant la main gauche derriere, comme est monstré cy dessus à sa pourtraiture & figure cotté en chiffre au derriere du bonnet 6. Voila la fin du commencement dudit troisiesme desgainement pour ledit Prevost. | |

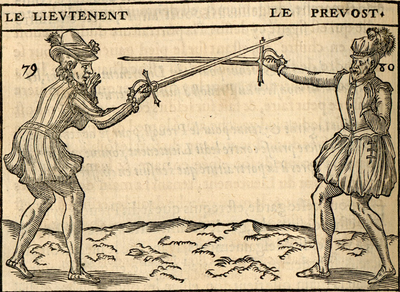

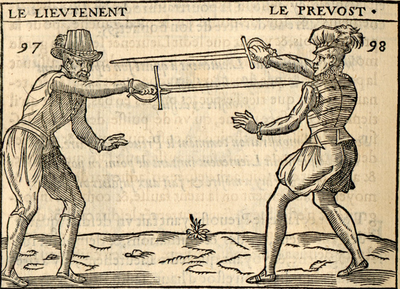

| The last of the third drawing for the Lieutenant and the Prevost that is left to declare its properties and significance below as portrayed and completed here.

In order to be effective and graceful to complete the said third drawing for the Lieutenant, the said Lieutenant must do the plan portrayed above where he keeps the right foot forward in the air after having made the said first and second drawing marked in number 5 in order to complete this drawing, which is to leave the said right foot over the footprint marked number 3 in this portraiture, turning the back of the hand holding the sword hilt up, as done by the Lieutenant marked number 3 since the artist made a mistake with this one. Yet the Lieutenant is to keep his left hand, making sure that he keeps it well under his sword arm as shown at the portraiture number 7. The last of the said final third drawing for the said Lieutenant. And in order to complete the said third drawing for the Prevost, he must come to be on the same plan as the above marked number 5 as shown with the preceding Prevost, who keeps the right foot in the air, keeping the back of the hand holding the sword hilt up, and to complete this said third drawing, the said Prevost must pull the right foot back from the air as stated above and leave it on the fooprint marked number 3 at the portraiture, turning the nails on the sword hand down, placing the sword point straight at the face or better yet the left eye, and keeping the left hand right on the shoulder, as shown above at the portraiture marked number 8. This is the last and final said third drawing for the said Prevost. |

La fin du troisiesme desgainement pour le Lieutenent & Prevost, que voicy pourtraits & parachevez, reste à declarer cy dessous leurs proprietez & significations

Pour bien, & avec grace parachever ledit troisiesme desgainement pour ce Lieutenent, faut estant sur le plan cy dessus pourtraict, où il tient le pied droict[14] en avant en l’air ayant fait ledit premier & second desgainement, cotté en chiffre, 5, est besoin que ledit Lieutenent, pour parachever ce desgainement, qu’il pause ledit pied droict qu’avoit en l’air, sur la semelle où est cotté à ceste pourtraiture en chiffre 3, retournant la garde de l’espée le dessus de la main en haut, comme fait le Lieutenent où est cotté en chiffre 3, car le pourtrayeur a faict faute à cestuy cy[15]. Mais cestuy Lieutenent icy tient bien sa main gauche, attendu qu’il la tient soubs le coude du bras de l’espée, comme est monstré à sa pourtraiture cotté en chiffre 7. La fin du parachevement dudit troisiesme desgaignement pour ledit Lieutenent. Et pour le parachevement dudit troisiesme desgainement pour ledit Prevost, faut aussi qu’il vienne à faindre estre sur le mesme plan cy dessus cotté 5, en chiffre à l’autre precedent Prevost, lequel tient le pied droict en l’air, tenant la garde de l’espée le dessus de la main en haut, & pour le parachevement de cedit troisiesme desgainement, faut que ledit prochain Prevost tire son pied droict arriere qu’avoit en l’air, comme est dit cy dessus, & le pauser sur la semelle où est cotté à sa pourtraiture en chiffre 3, tournant la main qui tient l’espée les ongles en bas, assituant la pointe de l’espée droict la face, ou l’œil gauche, qui est le mieux, & tenant la main gauche droict son espaulle, comme est monstré cy dessus à sa pourtraiture cotté en chiffre 8. Voyla la fin & parachevement dudit troisiesme[16] desgainement pour ledit Prevost. | |