|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Carlo Giuseppe Colombani"

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

<p>By which all people are shown how to wield the sword, dagger, cloak, halberd, flag and two-handed spadone, with ease, with the rules that should be followed by one who finds himself with his sword drawn, in order to defend and protect himself.</p> | <p>By which all people are shown how to wield the sword, dagger, cloak, halberd, flag and two-handed spadone, with ease, with the rules that should be followed by one who finds himself with his sword drawn, in order to defend and protect himself.</p> | ||

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/3|1|lbl=1}} |

| − | |||

| − | {{section| | ||

|- | |- | ||

| <p>'''''A work useful to all'''''</p> | | <p>'''''A work useful to all'''''</p> | ||

| − | | {{section| | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/3|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| <p>DEDICATED ''TO THE INCOMPARABLE MERIT'' OF THE YOUTH OF VENICE.</p> | | <p>DEDICATED ''TO THE INCOMPARABLE MERIT'' OF THE YOUTH OF VENICE.</p> | ||

| − | | {{section| | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/3|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| <p>IN VENICE, M. DCCXI.<br/>Printed by Miloco.<br/>''WITH PERMISSION FROM THE AUTHORITIES''</p> | | <p>IN VENICE, M. DCCXI.<br/>Printed by Miloco.<br/>''WITH PERMISSION FROM THE AUTHORITIES''</p> | ||

| − | | {{section| | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/3|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 98: | Line 96: | ||

<p>''This work can truly bring you great benefit, having first learned however sound principles from good masters, with figures of the most important positions and guards. And live in happiness.''</p> | <p>''This work can truly bring you great benefit, having first learned however sound principles from good masters, with figures of the most important positions and guards. And live in happiness.''</p> | ||

| − | | {{section| | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/4|1|lbl=2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| <p>''A simple method of learning how to attack well and wield arms correctly, through which the student should apply himself and work diligently; it is not his spirit or even his skill that will bring him success however, but merely a little judgment, since spirit and quickness count for little without the art.''</p> | | <p>''A simple method of learning how to attack well and wield arms correctly, through which the student should apply himself and work diligently; it is not his spirit or even his skill that will bring him success however, but merely a little judgment, since spirit and quickness count for little without the art.''</p> | ||

| − | | {{section| | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/4|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 129: | Line 127: | ||

<p>These are the principle parries and attacks you should teach your student at the beginning, to ensure he is accomplished ahead of giving him further lessons. He must parry with the heel, that is to say the sword's forte, and you should always keep your eyes open when you know he wishes to assault, so you can correct him when he errs. Similarly you should put him in posture in front of his enemy and show him how he should throw the attack, and once he has done this have him throw directly in front of you.</p> | <p>These are the principle parries and attacks you should teach your student at the beginning, to ensure he is accomplished ahead of giving him further lessons. He must parry with the heel, that is to say the sword's forte, and you should always keep your eyes open when you know he wishes to assault, so you can correct him when he errs. Similarly you should put him in posture in front of his enemy and show him how he should throw the attack, and once he has done this have him throw directly in front of you.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section| | + | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/4|3|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/5|1|lbl=3|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 173: | Line 171: | ||

<p>To execute everything well however, including these responses, and to deal with every sort of posture and movement, requires great effort. No man can put into practice what he knows without being able to train and exercise the movements in his mind. If we had bodies as sublime as our thoughts, people would be perfect. Our nature is too cumbersome a machine however, and requires great effort to manage and move before it functions without fault. Nonetheless with judgment, patience and endeavour, you will always become more accomplished than many others, if you have applied yourself.</p> | <p>To execute everything well however, including these responses, and to deal with every sort of posture and movement, requires great effort. No man can put into practice what he knows without being able to train and exercise the movements in his mind. If we had bodies as sublime as our thoughts, people would be perfect. Our nature is too cumbersome a machine however, and requires great effort to manage and move before it functions without fault. Nonetheless with judgment, patience and endeavour, you will always become more accomplished than many others, if you have applied yourself.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section| | + | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/5|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/6|1|lbl=4|p=1}} {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/7|1|lbl=5|p=1}} {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/8|1|lbl=6|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 182: | Line 180: | ||

<p>For this reason the fencer with the sword must quickly resolve, as soon as he sees the sabre fencer and is able, to throw an attack, either at the head, or at another target. He should throw feints to where he knows he can enter most easily, then quickly leap back, because if the fencer with the sword is not overly skilled, he runs a great risk of being harmed by the sabre's fury. Those who keep their guard in a straight ahead in a line however will always be wounded by the sabre, if its wielder has a modicum of experience.</p> | <p>For this reason the fencer with the sword must quickly resolve, as soon as he sees the sabre fencer and is able, to throw an attack, either at the head, or at another target. He should throw feints to where he knows he can enter most easily, then quickly leap back, because if the fencer with the sword is not overly skilled, he runs a great risk of being harmed by the sabre's fury. Those who keep their guard in a straight ahead in a line however will always be wounded by the sabre, if its wielder has a modicum of experience.</p> | ||

| − | | {{section| | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/8|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | To defend against a sword as long as a man, with a sword half a foot shorter than your enemy's, the fencer with the shorter sword should not be intimidated by his opponent's feints, whether mezze botte or provocations. Instead as soon as the enemy performs an attack he should quickly parry and close measure, or find the sword, observing the cavazioni as he closes measure. | + | | <p>To defend against a sword as long as a man, with a sword half a foot shorter than your enemy's, the fencer with the shorter sword should not be intimidated by his opponent's feints, whether mezze botte or provocations. Instead as soon as the enemy performs an attack he should quickly parry and close measure, or find the sword, observing the cavazioni as he closes measure.</p> |

| − | If the fencer with the shorter sword throws an attack at his enemy he must then quickly jump backwards, while raising his sword, since his opponent could still wound him easily. If the fencer with the short sword however, due to his great spirit, wishes to carry his blow from distance he runs a risk. This is because his enemy can hold firm with the significant advantage of his weapon, and on being tormented by attacks whose force he might not be able to parry, he becomes obliged to extend his arm and thrust. | + | <p>If the fencer with the shorter sword throws an attack at his enemy he must then quickly jump backwards, while raising his sword, since his opponent could still wound him easily. If the fencer with the short sword however, due to his great spirit, wishes to carry his blow from distance he runs a risk. This is because his enemy can hold firm with the significant advantage of his weapon, and on being tormented by attacks whose force he might not be able to parry, he becomes obliged to extend his arm and thrust.</p> |

| − | | ' | + | | |

| + | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/8|3|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/9|1|lbl=7|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''''On grappling''''' | + | | <p>'''''On grappling'''''</p> |

| − | Good judgment is required by those who wish to leap at the body. You should only attempt this when your enemy overextends himself in carrying out his attack. Seeing him slow to recover, you can seize the tempo and employ the grapple. | + | |

| − | | | + | <p>Good judgment is required by those who wish to leap at the body. You should only attempt this when your enemy overextends himself in carrying out his attack. Seeing him slow to recover, you can seize the tempo and employ the grapple.</p> |

| − | ' | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/9|2|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''''To defend yourself with a sword against a halberd''''' | + | | <p>'''''To defend yourself with a sword against a halberd'''''</p> |

| − | The fencer with the sword is advised to hold it firmly in the hand, and to grasp the middle of the blade with his left hand. If the enemy throws to the inside, you should parry with your right and perform an ''inquartata'' with your body. If he throws to the outside you should parry, passing with your left foot to his right in order to grapple him, which will succeed without any doubt. | + | |

| − | | | + | <p>The fencer with the sword is advised to hold it firmly in the hand, and to grasp the middle of the blade with his left hand. If the enemy throws to the inside, you should parry with your right and perform an ''inquartata'' with your body. If he throws to the outside you should parry, passing with your left foot to his right in order to grapple him, which will succeed without any doubt.</p> |

| − | ' | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/9|3|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''''Sword and cloak, sword and buckler''''' | + | | <p>'''''Sword and cloak, sword and buckler'''''</p> |

| − | |||

| − | He has only to ensure that all of his body is over his left foot, and that the sword is held at his thigh, as low as possible while still being usable. As for his left hand, the point of the dagger should be aimed at the enemy's throat, seeking to unsettle the enemy, so he leaves himself open to a straight thrust either to the outside or inside, whichever is easiest. He should take practice defending against attacks from a good fencer for at least fifteen days, in order to learn how to parry with a dagger in his left hand, and likewise with the cape, ''targa'' and hat. | + | <p>Once the student has a good understanding of the sword alone, having taken lessons from a good master, he will be able to quickly and very easily learn the sword and dagger, sword and cape and sword and ''targa'', noting that all three consist of but one play.</p> |

| − | | | + | |

| − | + | <p>He has only to ensure that all of his body is over his left foot, and that the sword is held at his thigh, as low as possible while still being usable. As for his left hand, the point of the dagger should be aimed at the enemy's throat, seeking to unsettle the enemy, so he leaves himself open to a straight thrust either to the outside or inside, whichever is easiest. He should take practice defending against attacks from a good fencer for at least fifteen days, in order to learn how to parry with a dagger in his left hand, and likewise with the cape, ''targa'' and hat.</p> | |

| + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/9|4|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''''Method of wielding the halberd against a sword, or in the midst of many swords''''' | + | | <p>'''''Method of wielding the halberd against a sword, or in the midst of many swords'''''</p> |

| − | |||

| − | In wishing to join a combat with a halberd you should grasp it a ''palmo'' from its head. By then using ''montanti'', while moving around at speed, you can enter into the fray without danger, the halberd being no more than a ''palmo'' taller than its wielder. | + | <p>If it happens that you must retrieve a halberd from your house or workshop to confront a sword, you should grasp the bottom of the halberd with your right hand, with your left hand in the middle. Your right foot should be back and your left foot forward, with your right arm well withdrawn. When you release a thrust you should immediately pull your attack back, and you should never swing the halberd when you know that the swordsman is accomplished, because he will be able to close to the grapple with ease.</p> |

| − | | ' | + | |

| − | + | <p>In wishing to join a combat with a halberd you should grasp it a ''palmo'' from its head. By then using ''montanti'', while moving around at speed, you can enter into the fray without danger, the halberd being no more than a ''palmo'' taller than its wielder.</p> | |

| + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/9|5|lbl=-}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''''The rule for the two-handed spadone against multiple swords''''' | + | | <p>'''''The rule for the two-handed spadone against multiple swords'''''</p> |

| − | This is applies both to a two-handed ''spadone'' and to long sword. Finding yourself assailed by enemies, and supposing that there are many of them, the situation demands nothing else but attacks like those of a desperate man, that is to say you must enter liberally into the fray. You should never throw thrusts with the point, except at an opponent who seems weaker, instead throwing ''roversi'', such attacks keeping you always in motion, this being the true method of defending yourself. | + | |

| − | + | <p>This is applies both to a two-handed ''spadone'' and to long sword. Finding yourself assailed by enemies, and supposing that there are many of them, the situation demands nothing else but attacks like those of a desperate man, that is to say you must enter liberally into the fray. You should never throw thrusts with the point, except at an opponent who seems weaker, instead throwing ''roversi'', such attacks keeping you always in motion, this being the true method of defending yourself.</p> | |

| − | < | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/9|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''''To defend yourself against one with a great spirit, but who possesses little knowledge of fencing''''' | + | | <p>'''''To defend yourself against one with a great spirit, but who possesses little knowledge of fencing'''''</p> |

| − | |||

| − | + | <p>In all the world where I practised, I heard of many instances of men with no knowledge of fencing having killed valiant men. Here I will reflect, and say that it is possible, but not as easy as some believe, because knowing a little is better than having a lot. If I had a great spirit without the art, I would say that the art can achieve more than a great spirit, because in having a great spirit without posture, tempo and measure I would never in any way be accomplished.</p> | |

| − | + | <p>Having to draw my sword from its sheath, I would always pray that heaven might send me an opponent with great spirit but no art (rather than a phlegmatic one with more art than me) because when you are beset by a misadventure such as this you can overcome it without danger.</p> | |

| − | + | <p>You should first however try and avoid drawing your sword against one who understands little of the art. If you are wounded your entire reputation is lost but if you wound or kill him it will grant you no honour. If you must draw your sword though, never jest with him or throw cuts, because in not understanding the danger he could charge forward, or leave himself in front of you, whereupon he might shame you.</p> | |

| − | This being so, I will now give some important advice, from a case I saw in Naples. A great personage, who had completed twenty four combats without ever being injured, was wounded by a young lad of tender years, who to his great shame took his life. May this instance therefore serve as an example to all those who carry a sword at their side, that it is always better to be circumspect and avoid such situations. | + | <p>I advise instead that you stand put yourself well in guard and stay covered. It he strikes desperately let him throw, and if he enters into measure you should retreat while always in guard. In the end, after he has thrown ten or twelve thrusts without effect, you can either wound him if you wish, or take his sword by coming to the grapple and leave him for the ignorant that he is. Reason will be yours however, as reason is the foundation of the art of the sword, since it it said that reason conquers all.</p> |

| − | | | + | |

| − | + | <p>This being so, I will now give some important advice, from a case I saw in Naples. A great personage, who had completed twenty four combats without ever being injured, was wounded by a young lad of tender years, who to his great shame took his life. May this instance therefore serve as an example to all those who carry a sword at their side, that it is always better to be circumspect and avoid such situations.</p> | |

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/9|7|lbl=7|p=1}} {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/10|1|lbl=8|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''''When combat takes place at night''''' | + | | <p>'''''When combat takes place at night'''''</p> |

| − | The rule for combat at night is as follows. You should never thrust except with your foot, and you should seek your enemy's sword by sound and with your sword, and once you find it releasing your thrust over its edge. A cape is better than a ''targa'', for those who know how to use it. | + | |

| − | | ' | + | <p>The rule for combat at night is as follows. You should never thrust except with your foot, and you should seek your enemy's sword by sound and with your sword, and once you find it releasing your thrust over its edge. A cape is better than a ''targa'', for those who know how to use it.</p> |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/10|2|lbl=-}} | |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''''To learn the play of the flag''''' | + | | <p>'''''To learn the play of the flag'''''</p> |

| − | Firstly your flag should be the same height as you, and be well counterbalanced both with lead and wood, so that the whole flag weighs as much as the ''palmo'' of lead. Every step that you take should be accompanied by a flourish of the flag, and you should practice with your left as well as your right. In this manner you can also learn without difficulty to play with two flags. | + | |

| − | | ' | + | <p>Firstly your flag should be the same height as you, and be well counterbalanced both with lead and wood, so that the whole flag weighs as much as the ''palmo'' of lead. Every step that you take should be accompanied by a flourish of the flag, and you should practice with your left as well as your right. In this manner you can also learn without difficulty to play with two flags.</p> |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/10|3|lbl=-}} | |

|- | |- | ||

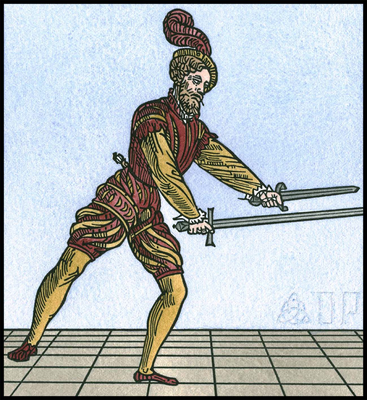

| − | | rowspan="3" | [[File:Marozzo 6.png| | + | | rowspan="3" | [[File:Marozzo 6.png|400x400px|center]] |

| − | | Every sort of guard should be good for those with some knowledge, but I say the Italian guards are the best. | + | | <p>Every sort of guard should be good for those with some knowledge, but I say the Italian guards are the best.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/10|4|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Those who wish to describe everything in great detail are like those who would seek the Phoenix at the bottom of the sea, since I am sure that if they searched that vast ocean, they would do so in vain. | + | | <p>Those who wish to describe everything in great detail are like those who would seek the Phoenix at the bottom of the sea, since I am sure that if they searched that vast ocean, they would do so in vain.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/10|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | It is better to do one thing well, and let everyone take stock, etc. | + | | <p>It is better to do one thing well, and let everyone take stock, etc.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/10|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | class="noline" | [[File:Marozzo 9.png| | + | | class="noline" | [[File:Marozzo 9.png|400x400px|center]] |

| − | | class="noline" | '''THE END.''' | + | | class="noline" | <p>'''THE END.'''</p> |

| − | | class="noline" | ' | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani).pdf/10|7|lbl=-}} |

|} | |} | ||

Revision as of 21:31, 5 June 2020

| Carlo Giuseppe Colombani | |

|---|---|

Colombani performing a dentistry exhibition | |

| Born | 21 January 1676 San Bartolomeo, Italy |

| Died | 1735 or 1736 Venice, Italy |

| Spouse(s) | Apollonia Colombani di Livorno |

| Relative(s) |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Movement | Dardi tradition |

| Influences | Achille Marozzo |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) | L'Arte maestra (1711) |

Carlo Giuseppe Colombani (1676 - 1735/6) was an Italian soldier, fencing master, and dentist at the turn of the 18th century. He was born on 21 January 1676 in San Bartolomeo to Francesco and Isabella Colombani, who seem to have been of high social status. In 1693 at the age of 17, he joined the army of Vittorio Amedeo of Savoy to fight in the war with the French. Colombani participated in several battles (Guastella, Pinerolo, Orbassano, Santa Brigida, and Staffarda) and ultimately became an officer and color guard; for his valor he gained the title Alfier Lombardo ("the Pride of Lombardy").[1]

Colombani traveled for a time after the war, passing through Barcelona, Spain before returning to travel around his native Italy. He supported himself as a fencing master during this time, teaching private lessons and performing public exhibitions; he also dabbled in other forms of performance including charlatanism, puppetry, and tightrope walking. In 1700, he seems to have become involved with a Spanish woman and embarked on another international journey through France, Holland, and England, eventually exhausting all of the wealth he had acquired.[1]

In 1709, he married Apollonia, the daughter of a respected tooth-puller, and then moved to Venice and received an official diploma in dentistry. Between 1710 and 1712, Colombani practiced charlatan dentistry and minor medical care in the public piazza in Venice, proving himself the most capable dentist in the city (other than his wife).[1] In 1711 (during this same period), he also published a brief treatise on fencing with at least some tenuous connection to the tradition of Filippo di Bartolomeo Dardi entitled L'Arte maestra ("The Master Art").

After 1712, Appolonia convinced him to give up public exhibition and they devoted themselves to a more scientific approach to dentistry. He lived the rest of his life in Venice, practicing his trade and become extremely wealthy. Colombani went on to publish several other books on various topics, including a fairly sensationalized memoir in 1724; his wife was also a writer, publishing a treatise on dentistry in 1719.[1]

Contents

Treatise

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

THE MASTER ART OF GIUSEPPE COLOMBANI KNOWN AS THE LOMBARD ENSIGN By which all people are shown how to wield the sword, dagger, cloak, halberd, flag and two-handed spadone, with ease, with the rules that should be followed by one who finds himself with his sword drawn, in order to defend and protect himself. |

[1] LʼARTE MAESTRA DI GIUSEPPE COLOMBANI DETTO LʼALFIER LOMBARDO Nella qual sʼimpara facilmente adʼogni persona adʼimparare a maneggiar da se stesso la Spada , e Pugnale Tabaro , Targa , Labarda , Bandiera , Spadone à due mani, con le regole, che deve usar ogni persona trovandosi con la Spada nuda per ben guardarsi , e diffendersi. | |

A work useful to all |

Opera utile adʼogni persona | |

DEDICATED TO THE INCOMPARABLE MERIT OF THE YOUTH OF VENICE. |

DEDICATA AL MERITO IMPAREGGIABILE DELLA GIOVENTUʼ VENEZIANA. | |

IN VENICE, M. DCCXI. |

IN VENEZIA, M. DCCXI. | |

TO THE READER. I know dear reader, that I am too eager in wishing to present this feeble labour of mine before your eyes. If it is true however, that great men are not disdainful of small offerings, then please enjoy this meagre effort, which I hope through your heart you will deign to consider, read, and find to be a work necessary for all those who seek to defend and safeguard their lives, showing the correct path towards acquiring the true blows, and understanding of the sword. I can only say that I have toiled all of my youth, but since many good and able masters have practised, I do not presume to speak except to those under the discipline of talented men. I therefore seek to instruct to each of those who desire to know all of the rules of the sword, or rather not all of them, but the most vital and principal among them: with the sword alone, with the sword and dagger, sword and targa, and sword and cloak; how to behave in combat at night, how to comport yourself in an affray, what to do to defeat without any doubt someone with a great heart but who does not possess the true science of the sword; what you must do when attacked by someone wielding a spontoon or halberd, how to defend yourself with the sword and overcome him. Furthermore how to wield a halberd against a sword, how to wield a two-handed spadone or long sword in the midst of many swords, the true method of using the pole for the plays of the flag and pike; the true knowledge of which is the best posture of all, since I have practised with all of them; how to comport yourself when playing with those of other nations, what to do when fighting against a sabre, how to deal with grapples and disarms. This work can truly bring you great benefit, having first learned however sound principles from good masters, with figures of the most important positions and guards. And live in happiness. |

[2] AL LETTORE. Conosco hò benigno Lettore esser tropo ardito in volerti presentar avani delli tuoi ochi questa mia debol fatica, mà se è vero non esser desdicenti à li animi grandi una picol offerta, dunque gradisci questa mia picola fatica chʼio spero mediante il tuo animo ti degnarai considerarla, legerla, e troverai esser opera necessaria à tutti quelli che pretendono difender è benguardar la sua vita dandosi il vero camino per aquistar le vere bote, e la vera cognitione della Spada, solo ti posso dir di haver fatigato tutta la mia gioventù, e havendo praticato boni, e virtuosi Maestri, non pretendo però di parlar se non sotto le descipline de virtuosissimi huomini; e così voglio far conoscere à tutti quelli che bramano di saper tutte le regole della Spada, cioè non tutte, ma le più bisognose è le principali, che ognʼuno deve saper per guardarsi, così di Spada sola, come di Spada, e Pugnale, Spada, e Targa, Spada, e Tabaro, e nelle costioni di notte come si deve contenersi nelle zuffe, come ti devi regolare, come devi far per vincere senza dubio uno, che à gran core, e non possiede la vera scienza della Spada, come devi contenerti quando sarai assaltato da uno che havesse il Spontone ò Labarda, esso con la Spada difenderti, e vincerlo. Come devi con la Labarda contro la Spada, come devi manegiar il Spadone à due mani ò Spada longa in mezo à più Spade. Il modo è la vera regola per far le aste da giocar le Bandiere, e la Pica, e la vera cognitione qual sia la meglio positura di tutte avendole io praticato tutte, e come ti devi regolar con il giocar con altre nationi come devi far quando succedesse di far costione contro la Sabola, come devi regolarti contro la presa ò disarmatura. Opera in vero che ti potrà portar gran profito avendo però li boni principi da virtuosi Maestri con le figure delle guardie ò piante più bisognose. E vivi felice. | |

A simple method of learning how to attack well and wield arms correctly, through which the student should apply himself and work diligently; it is not his spirit or even his skill that will bring him success however, but merely a little judgment, since spirit and quickness count for little without the art. |

Modo facile per aprendere à ben tirare. & fare propriamente dellʼarmi, mediante chʼel Scolaro si voglia aplicarsi, & pigliarci pena; non è però il suo animo ne mancho sua destrezza, che lo farà riuscire bravo, ma solamente un poco di giuditio perche lʼanimo, e la prestezza serve poco senza lʼarte. | |

Because if an untrained fencer on occasion throws some attacks, it is only through chance. To give the student a simple method of throwing good attacks, first you must position him correctly over his legs and make him walk with both short and long steps, moving forwards and backwards. You should then show him the forte and debole of the sword, and then teach him what is meant by quarta, terza, and seconda. When he is able to understand the motion of the thrusts, you should place him into the natural guard, demonstrating how he should keep a distance of two feet between his left and right foot, his left knee slightly bent and his right leg fully extended, the hips in line and his body straight, with his left hand forming a circle at the height of the eye. From this position you should have him extend an attack in quarta, having him release the hand in this tempo. You should then have him bend his right knee and straighten his left knee, if it so happens that the hand needs the help of the foot to reach the enemy's body. You should have him advance his right foot forward half a foot and, when he is in this position, show him how to throw this thrust by turning the nails of his right hand upwards, and those of his left hand downwards. Both arms should be extended level in height along the same plane, with the the feet similarly aligned, the head leaning a little to the outside of the sword. When you have demonstrated these rules you should have him throw in terza, always starting with the hand and not rushing in but as I have already said moving the foot when it is needed by the hand. You should demonstrate how the nails of the left hand should be turned towards the ground, and those of the right hand turned towards the sky. The head should be positioned along the line of the arm, directly over the knee; because if it is not over the knee, inevitably he will drag his body towards the ground, something I have witnessed many times in the salle. Next you should show them how to thrust in seconda, which in effect is a reversed quarta thrown below the line of the arm. These are the three main attacks that the student must learn well. There are others named quinta and prima, which are not so important for the student to see until his initial efforts are completed, which I will speak of when the time comes. Once the student is stable on his feet, understands the motion of the first three blows, and can execute them very well, you should show him the parries and the attacks which accompany them. Firstly you should show him how to parry the sword's forte to the inside of his weapon, which is performed by lifting the hand. The attack for this parry is a mezza botta carried out in two tempi, or else a quarta rotta, which you will demonstrate over the course of eight days. When you see he is adept at this, you will defend against the mezza botta with the parry of the sword's point, which you should show him along with the attacks that accompany it. These are a feint inside the weapons before throwing underneath, or else a feint in quarta before throwing in terza. These are the parries of the sword to be performed, and the attacks which follow these types of parry, that you should show your student and have him throw in the space of a month. When he is proficient with these you will teach him the parries over the sword, firstly those in which the arm is raised. You should show him this parry, for which you should throw a feint to the head, then a thrust in seconda. When he has learned all of this well, you should demonstrate how to parry the point to the outside of the weapons. You should have him feint to the outside, before thrusting to the inside, or else perform a feint in terza followed by a thrust in quarta. These are the principle parries and attacks you should teach your student at the beginning, to ensure he is accomplished ahead of giving him further lessons. He must parry with the heel, that is to say the sword's forte, and you should always keep your eyes open when you know he wishes to assault, so you can correct him when he errs. Similarly you should put him in posture in front of his enemy and show him how he should throw the attack, and once he has done this have him throw directly in front of you. |

Perche se qualche volta tira qualche colpo non è che di fortuna, mà per dare un modo facile al Scolaro à ben tirare dellʼarmi, bisogna prima bene situarlo sopra le sue gambe, & farlo caminare à passi picoli, & grandi, che si fanno in avanti, & indietro, bisogna poi farli conoscere il forte, & il debole della Spada, & poi imparargli, che cosa significa quarta, terza, & seconda, & quando potrà conoscere il movimento delle stocade, bisogna situarlo nella guardia naturale facendoli conoscere, che bisogna avere una distanza trà il piede sinistro, & il piede dritto di due piedi il ginochio sinistro, uno poco piegato, & la gamba dritta tutta distesa, le anche quadre, & il corpo dritto, & la mano sinistra in modo di cerchio à lʼaltezza dellʼocchio: in quella positura li fatte slongare la botta di quarta, facendola partire nellʼistesso tempo la mano; Dipoi fatteli piegare il ginochio destro, & il sinistro disteso, se à caso la mano havesse bisogno del piede per andare al corpo del suo inimico; gli farete portare il piede destro [3] in avanti mezo piede, & quando lo Scolaro è in quella situazione gli farete conoscere, che quella stochata si tira voltando le ongie della mano destra in alto, & quelle della sinistra à basso, li due brazzi distesi sopra dʼuna stessa regola egualmente alta, & egualmente sopra la regola del piede; la testa un pocho pendente al di fuori della Spada, & quando voi li havreste fatto osservare queste regole gli farete slongare la Terza partendo sempre dalla mano, & non correre, mà il piede che come hò già detto quando la mano ne havrà di bisogno, facendo osservare che le ongie della mano destra siano volte verso la terra, & quelle della sinistra verso il Cielo, il capo situato al longho della ligna del brazzo direttamente al di sopra del ginochio, perche se non è al di sopra del ginochio, lui strascinerà infallibilmente il corpo per terra, cosa, che hò veduto molte volte nelle Salle; seguitando poi gli mostrarete á tirare la Seconda, che è propriamente una quarta rinversata che si tira al di sotto della ligna del braccio. Queste sono le tre botte principali che il Scolaro deve bene imparare; ve ne sono che si chiamano quinte, & prima del che non è troppo necessario per farle osservare allo Scolaro che nel seguito del suo travaglio che poi ne parlerò nel tempo che saranno proprie; quando una volta che lo Scolaro stà fermo, è che conosce il movimento di quelle tre botte, & che le sà portare benissimo gli farete conoscere le parade, & li colpi che bisognano per tutte le parade, primieramente voi li farete osservare in qual modo si fà la parada del forte della Spada, di dentro lʼarma che si fà in levando la mano, il colpo per quella parada è una mezza botta che si fà in due tempi, altrimente quarta rotta che li farete osservare lʼespaccio di otto giorno, & quando conoscerete che sarà habite nella foncione voi gli parete questa mezza botta per la parada della ponta della Spada. la qual cosa farete conoscere al Scolaro, e i colpi che bisognano per questa parada, e una finta da dentro lʼarmi, & tirate al di sotto altrimente è una finta di quarta, & tirare di terza; ecco le sue parade che si fanno nella spada e i colpi che seguano queste sorte di parade, che vi farete osservare, & tirare il spazio dʼun Mese al vostro Scolaro, e quando sopra il tutto per pratticha voi gli farete conoscere quelli di sopra la spada, primieramente quelle in levando il braccio, & quella parada gli farete osservare, cha per quella parada bisogna fare una finta alla testa, & tirare detta seconda, & quando conosce benissimo il tutto gli farete conoscere la parada della ponta al di fuori dell armi per quelle parade. Voi li farete fare una finta al di fuori dellʼarmi, & tirare al di dentro dellʼarmi, altrimente una finta di terza, & tirar di quarta, queste sono le principal parade, & colpi che si devono principalmente imparare à uno Scolaro per renderlo perfetto avanti di darli altre lettioni, che bisogna parare dal calcagno, ò veramente del forte della spada, & tenere sempre lʼocchio aperto quando conoscerete che vol fare assalto, accioche lo possiate corregere quando fà male, e medesimamente metterlo in positura avanti il suo innimico, & li farete osservare come bisogna tirare il colpo quando hà tirato farglielo fare avanti voi medesimo. | |

Once the student has had lessons for three or four months, you will show him the simplest method of throwing these attacks with greater skill, and how to overcome those who flee, rush in, and parry with their hands. Before demonstrating how to defeat these sorts of opponents however, you should teach your student the method and manner of attacking judiciously, telling him never to throw an attack without due consideration. For example if he throws in quarta or terza, and it so happens that his attack is parried, he should think of nothing else except giving his response, carefully observing how the attack was defended. If it was defended by his opponent's forte, after retreating he should give a mezza botta; if this is parried he must think only of giving his reply. If the enemy refuses to enter into his measure however, and this hinders his designs; you must demonstrate how, as he advances into measure and his opponent withdraws, he must ensure he can parry his enemy's attacks and respond with vigour. When the enemy sees he has been parried, he will no longer be able to throw with such zeal, and will surrender his measure with ease. In this manner the student can execute his intentions without difficulty inside or outside of the weapons, observing with attention the parries and attacks, which proceed as I have already noted above. If he follows these admonitions carefully he will be able to fight against any sort of person, and can be scornful of any posture. When it is said to me that the French guards, the German guard, and the Spanish guard are more difficult to beat, these are all lunacies. A Frenchman, a German and a Spaniard have bodies similar to mine. If I know how to defend my body with a good posture, I do not see why I need to adopt their postures to defend myself from their extravagant guards. I have seen a great many of these, and I have noted that their positions do not even have any strength in them. In respect of these guards, as I will come to explain, with time in his efforts the student will realise that what I say is the absolute truth. Although I pronounce it with my tongue, this advice follows in the footsteps of many honoured masters from this Serenissima Dominante and from other locations. Before arriving at the attacks that I have used against these guards however, I will describe the method suggested by my feeble intellect, of how to beat those who flee, rush in, and parry with their hands. For those who flee, you should let your sword extend and take a small step to straighten your left knee, in order to find the measure and give the attack. With this method you will be successful, not neglecting to complete the blow having thrown the attack. If your opponent attacks you must parry, and give your response. If he lets his point drop low and wishes to raise his fist, throw an attack in quarta below the line of his arm, opposing him with your left hand. This is the attack known as quinta, or the fianconata. If he keeps his point high however, you should turn your hand from quarta to seconda, then raising your hand further into the attack known as prima. If your opponent remains opposed to your sword, you should disengage and perform your attack; if he parries, you should execute the feint appropriate to the parry he employs, either inside or outside the sword, or in seconda. Double feints are very effective against this sort of opponent, as long as they are well executed. The method and technique for provoking all manner of openings is as follows. You begin by throwing an attack from a firm foot, either in quarta or terza. If your enemy parries, you should feint a response, considering the manner in which your blow was defended, and feinting in accordance with your enemy's parry. If again your feint is defended, you must always think to respond. You should observe how your feint was defended and, in accordance with this parry, redouble your feint, returning your point to where your enemy defended previously. In completing this attack you should stamp your foot twice. The first stamp is performed while standing firm, and returning your point to where the first feint was parried. The second stamp is executed while extending a short step forward, straightening your left knee, while carrying your point to where the previous attack had been defended. In this manner you will never attack with excessive fury, although you should keep your arm well extended, since there is a strong risk of being struck in the same tempo if you attack haphazardly. For this reason you should always perform an arrest of some sort when redoubling, so you can quickly parry anything your enemy may attempt in that tempo. Regarding those who rush in there is a different method. Rather than advancing you should take a small step backwards, and when you see that they wish to rush in, you should attack purposefully to wherever you see is most uncovered. In this manner your blow will never fail if you judge the measure of your sword well. It is very effective against this sort of opponent to perform two or three stamps of the foot, the first while standing firm, the second by stepping a good half-foot forward with your right, without moving your left and with your arm extended well forward. As you recover inevitably they will advance, and you can hit them in the tempo in which they raise their foot, to the target you see is most uncovered, whether in quarta, terza or seconda. If they move in quarta to look for your sword, you should throw in terza, and if they find it in quarta you should throw in terza, while if they move in seconda you should throw in seconda. For those those who parry with the hand you should perform a cavazione. They cannot employ two actions at once, that is to say parry and attack, therefore when you know that a man parries with his hand and he holds it high, wanting to parry any blow you attempt to his stomach, you should bring your hand forward and present your attack in the same tempo. When you see his hand approaching you should perform a cavazione over it with a circular motion, and if he moves his hand again thinking to meet your sword you should perform a ricavazione below, with the same movement. If he has his hand near is abdomen and still wishes to parry with it, you should present your point right at his heart, and he will not fail to raise his hand in order to parry. As he does so you should put your point to the pit of his stomach with a circular movement, and if he still moves his hand to meet your sword low you should perform a ricavazione over it. This is the method and manner which I employed, and which I always found very effective to beat this sort of person. You need great patience however, and much effort, because you should not believe that you can be as accomplished as a master within a year or two, and be consummate at wielding arms. I would say that it is very difficult to find a man highly accomplished with weapons. Returning to the Italian, German and Spanish Guards, and to the attacks I used to defeat these sorts of guards. Against the French I performed a disordinatione of the sword. Against the Germans I gave a crollamento, opposing the enemy with my left hand, sometimes with two beats, the first in quarta and the second crossing swords while advancing with a small step, as well as performing many double feints since they attack the sword often. Against Spaniards, since they always follow with their rear foot, I performed a cavazione of the sword upon contact, sometimes in two tempi, closing measure with a short step. You must pay attention to your head when dealing with a Spaniard, because there is no parrying these attacks, since they throw only at the eye, saying that they are more capable when aiming for the eye rather than the middle of the stomach. You should also keep in mind to watch your opponent's responses as well as his attacks, that is to say observe how the enemy parries your counter. If he parries it by raising his arm, you should give him a mezza botta, if he parries the point you should perform a cavazione, and if he parries the cavazione you should feint in the manner I demonstrated above in discussing the attacks. To execute everything well however, including these responses, and to deal with every sort of posture and movement, requires great effort. No man can put into practice what he knows without being able to train and exercise the movements in his mind. If we had bodies as sublime as our thoughts, people would be perfect. Our nature is too cumbersome a machine however, and requires great effort to manage and move before it functions without fault. Nonetheless with judgment, patience and endeavour, you will always become more accomplished than many others, if you have applied yourself. |

Quando poi lo Scolaro havrà auto lettione tre ò quattro Mesi, voi gli farete conoscere il modo più facile per tirare qnelli colpi con più destrezza, [4] & mostrarli come bisogna fare per battere quelli, che fugano, che corrano, & che vanno alla parada con la mano, ma avanti che di venir al giuoco per bettere con più facilità quelle sorte di persone, bisogna mostrare allo Scolaro il modo, & maniera di far assalto con giudicio dicendoli, che non bisogna mai tirare un colpo senza prima pensare bene, cioe che quando tira quarta, ò terza, e che in caso suo colpo, e parato non deve pensare à altro, che da dargli la risposta, & osservare bene come il suo colpo dʼattacco è stato deffeso, sʼè slato diffeso dal forte della spada, bisogna, che dopo la sua ritirata faccia la sua meza botta, & se in caso gli è parata, che pensi sempre à darli la risposta, mà se il nemico non volesse sopportare di entrare nella sua misura, & che questo li dasse impedimento nelli suoi dissegni, bisogna fargli osservare, che quando entra in misura, che il suo inimico venisse à partire, che faccia in sorte di parare li colpi, & di darli vigorosamente la risposta, & quando una volta lʼinimico vede, che il colpo glʼè stato parato, non possa più tirare così arditamente, e si lascia facilmente in misura, e così e facile di poner in essecutione i suoi dissegni dentro le armi, cosi bene come fuori le armi osservando bene le parade, & li colpi, che seguano come hò già noto quì sopra lo scolaro, che bene osserverà questi avertimenti non mancherà di farsi habile per combatere contra qual si voglia sorte di persona, & si puol fare scherno di qual si voglia postura, & quando mi vengono dire, che le guardie Francese la guardia todesca, & la guardia Spagnola sono più difficile à battere, che le altre queste sono tutte pazzie, il Francese, Tedesco, & Spagnolo hanno un corpo simile al mio, & se sò diffendere il mio corpo dʼuna buona postura, non aprovo che non sii necessario, che io prenda le loro posture per diffendermi delle loro guardie straordinarie, che io hò veduto à molti, e molti, là dove io hò fatto osservatione, che hanno manco forza dentro le loro posture, che dentro qnelle, che io vengo di narrare, lo scolaro conoscerà al longo andare del suo travalgio che quello chʼio vengo dire, è vero verissimo, ma avanti che di venire alli colpi che io parlando però con la lingua sono le piante di Signori Maestri di questa Ser Dom. & altre parti, mi son servito in quelle sorte di guardie, io ne diro il modo conforme me ne suggerirà il mlo poco intelletto, come bisogna battere quelle sorte di persone che fuggano, che corrano, & che parano con la mano à quelli che fuggano bisogna lasciar correre il longo della Spada per un picol passo tenendo disteso il ginochio sinistro a fine di potersi trovare in misura per darli una bota, & in tal caso ve ne caverete, & per portare una botta, non lasciarete di finire il vostro colpo, & se tirano bisogna parare, & dare la risposta, & se lasciano cadere la punta à basso; & che vogliano levare il pugno, a voi tirate di quarta sotto la ligna del braccio opponendo la mano sinistra, quando il colpo, che si chiama quinta ò fianconata, e se sostengono la ponta alta, quando voi ci lasciate di quarta, voi voltate la mano di seconda in levando bene il pugno questo è il colpo, che si chiama primo, se restano contro la vostra spada, voi cavate è farete il vostro colpo, & se parano, voi farete poi la finta conforme che le parade, che faranno, sia dentro la Spada, ò fuori della spada, ò di seconda le finte doppie sono bonissime per quelle sorte di persone mediante [5] che siano ben fatte, ecco il modo, & maniera che bisogna fare per eccitare tutte le sorprese; si comincia à tirare un colpo à piedi fermo, sia quarta ò terza & se lʼinimico lo para, voi farete finta di darli la risposta, e bisogna guardar in qual modo il vostro colpo è stato diffeso, e conforme la parade che lʼinimico haverà fatta, gli farete la finta, e se la vostra finta è stata ancor diffesa, voi pensarete sempre alla risposta, osservarete in qual maniera la vostra finta è stata difesa, è conforme la parada, voi doppiarete la vostra finta, in rapresentando la ponta là dove lʼinimco ha fatto difesa, e se fa in questo modo battendo due volte del piede il primo battimento del piede si fa fermo in rapresentando la punta là dove la prima finta è stata diffesa, è il secondo battimento del plede si fà in avanzando un picol passo in avanti distendendo il ginochio sinistro marchiando con la punta là dove lʼultimo colpo è stato diffeso, e in questo modo voi non fatarete mai vostro colpo mediante che voi non andiate con troppa furia, è bisogna havere il braccio bene disteso, perche è molto pericoloso di esserne colto sopra lʼistesso tempo se si fa balordamente, e per questo bisogna sempre fare come un modo di arestamento, nel doppiamento accioche possiate sempre essere lesto per parare ogni caso che lʼinimico ci voglia prendere sopra quel tempo à riguardo di quelli che corrono in avanti, questa e unʼaltra maniera perche in cambio di avanzarsi bisogna fare in modo dʼun piccolo passo indietro, e quando vedete che vogliano cortere tirate arditamente nel luogo dove vedrete più scoperto, & in quel modo non mancherete mai vostro colpo se voi pigliate bene le vostre misure, della Spada son bonissimi per questi corridori, che se fano batendo due, ò tre volte del piede, la prima volta del piede fermo, & la seconda volta partendo il piede destro in avanti di un bon mezo piede senza movere il sinistro, & il braccio longo disteso, & rimettendovi non mancheranno di marchiare, & ii prenderete nel tempo che levano il piede nel luogo che vedrete più scoperto, sia quarta, terza o seconda, mà se a caso vengono per cerchare la spada di quarta voi tirate di terza, & se la trovate di terza voi tirate di quarta, & se vengono di seconda voi tirate di seconda quella cavatione per quelli che parano con la mano, non possono fare due, atti alla volta cioè parare, & dare, & cosi quando conoscerete, che unʼhomo para con la mano, se la tiene alta, & che voglia parare il colpo che voi gli volete portare nel estomaco, bisogna che avanzate la mano presentandogli un colpo nel istesso tompo, & quando vedete la mano avicinarsi, voi cavate di sopra per il movimento del cercolo, & se reviene credendo di ritrovarla, voi raincavate peʼl di sotto per lʼistesso movimento, & se ha la mano verso il ventricolo, & che voglia ancora servirsene per parare, voi gli presentarete il colpo giusto al cuore, & non mancherà di volere levare la mano per parare, & in quel voi tirate la punta per il movimento del cercolo nella bocca dello stomaco i e se riporta ancora la mano per ritrovarla à basso, voi rincavate di sopra, è questo è il modo, e maniera che mi son servito, & che me ne sono sempre trovato benissimo, per battere tal sorte di persone, mà vi si vole gran patienza, & molta fatica perche non bisogna credere, che frà unʼanno ò due si possi esser si forte, che il Maestro, & che si possa far dellʼarmi nella perfettione, per me dico, che è molto difficile di [6] trovare un huomo molto perfetto nellʼarme per ritornare alle guardie Italiane, Todesche, & Spagnole, & alli colpi, che mi sono servito per tale sorte di guardie, al Francese io li faceva una disordinatione di Spada, & al Todesco il crollamento opponendogli la mano sinistra, & qualche volta per due battimenti, uno di quarta, & lʼaltro crosando la Spada in avanzando un picol passo, fa ceno dopie finte perche si attacha molto alla Spada, per lʼEspagnolo perche seconda sempre il piede di dietro, gli faceva le cavationi della Spada per un toccamento qualche volta il colpo in due tempi in serando la misura per un picolo passo, bisogna star avertito alla testa quando fate con lʼEspagnuolo perche non hanno nissuna parada, perche non tirano, che à lʼochio, perche dicano, che sono più habili quando dano nellʼochii, che quando danno nel mezo dello stomaco, bisogna ancora tenere à mente, che bisogna guardare le risposte, come gli colpi dʼottaco; come sarebbe à dire osservare, come lʼinemico para vostra risposta, se à caso la para in levando il braccio voi li darete la mezza botta, se la pará della ponta, voi cavate, & se para la cavatione voi li farete la finta come vi hò dinotato qui sopra nelli colpi dʼattaco, mà per fare riuscire ogni cosa bene, & come anche le risposte, & fare contra ogni sorte di posture, e de movimenti si vuole un grande travaglio, perche non vi è huomo, che possa mettere pratica quello, che conosce per pratica, non havendo la facilità del corso per potere esercitare gli movimenti del pensiero, & se si trovasse de corpi tanto sublimi, come gli pensieri, vi sarebbe molte persone perfette, mà la nostra natura è una machina troppo pesante, che ci vole molta fatica à regolarla, & moverla per farla riuscire con tutte le perfettioui, nulla di meno con il giuditio; la patienza, & il travaglio, si puole sempre arrivare à riuscire meglio, che molti altri quando ci haverette lʼattentione. | |

A method of defence with the sword against a sabre Firstly if a man has good judgment he should hold his sword hand by his pocket, a foot and a half off the ground, so that the sabre cannot beat his blade. This is because the sabre seeks nothing except the blade in order to displace it, or if not the hand. For this reason the fencer with the sword must quickly resolve, as soon as he sees the sabre fencer and is able, to throw an attack, either at the head, or at another target. He should throw feints to where he knows he can enter most easily, then quickly leap back, because if the fencer with the sword is not overly skilled, he runs a great risk of being harmed by the sabre's fury. Those who keep their guard in a straight ahead in a line however will always be wounded by the sabre, if its wielder has a modicum of experience. |

Modo per diffendersi Contro una Sabola con Spada Primieramente se è huomo, che habbia giuditio alla Spada bisogna, che tengā la mano dove hà il maneggio contra lʼe scarsella, à un piede, e mezzo da terra accioche la Sabola non possa battere la sua lama, perche la Sabola non cerca altro, che la lama per dismontarla, ò veramente il pugno, in modo tale. che quello, che si serve della Spada, deve giudicare subito, che vede quello che gioca della Sabla, & che conosce, che li vol dare un colpo, sia alla testa ò in altro luogo facendole finte al luogo dove conosce, che più facilmente puol intrare, & subito saltare indietro perche se quello, che tiene la Spada, non è troppo habile corre molto pericolo, che la furia della Sabla non gli porta danno, per quelli, che tengono la guardla in diritta linea saranno sempre offesi per la Sabla, se quello, che la manteggia hà un poco di studio. | |

To defend against a sword as long as a man, with a sword half a foot shorter than your enemy's, the fencer with the shorter sword should not be intimidated by his opponent's feints, whether mezze botte or provocations. Instead as soon as the enemy performs an attack he should quickly parry and close measure, or find the sword, observing the cavazioni as he closes measure. If the fencer with the shorter sword throws an attack at his enemy he must then quickly jump backwards, while raising his sword, since his opponent could still wound him easily. If the fencer with the short sword however, due to his great spirit, wishes to carry his blow from distance he runs a risk. This is because his enemy can hold firm with the significant advantage of his weapon, and on being tormented by attacks whose force he might not be able to parry, he becomes obliged to extend his arm and thrust. |

Per diffendersi contro unà Spada longa un huomo, che habbia una Spada corta dʼun mezo piede poco meno, che suo inimico bisogna, che quello, che lʼhà corta non si spaventi delle finte, che gli fà il suo aversario, tanto à meze botte che à desfida, che subito, che il suo inimico fornisse un colpo deve ricorrere subito parada, & serrarlo, ò stringerlo, & osservar le cavatione nel mentre che voi lo serrate, & se quello che si serve della Spada corta dà al suo inimico deve subito saltare indietro, in levando la sua Spada da se perche quello, che hà ricevuto il colpo potrebbe ancor facilmente offenderlo, & se quello, che si ser [7] ve della corta volesse per il suo gran animo portare delle botte in longhezza, corre pericolo perche il suo inimico si tiene forte per il grande avantaggio che hà della sua spada perche vedendosi opresso dai colpi che puol essere non potersi riparargli la forza lʼobbligarebbe à stenderli il braccio per fare un colpo forado. | |

On grappling Good judgment is required by those who wish to leap at the body. You should only attempt this when your enemy overextends himself in carrying out his attack. Seeing him slow to recover, you can seize the tempo and employ the grapple. |

A servirsi della Presa Il giuditio non deve manchare à quello che vuole saltare alla persona & non servirsene che quando il suo inimico portandogli un colpo si slonga oltre misura & vedendoli cosi tardi al ritirarsi puol proffittare del tempo è servirsi della presa. | |

To defend yourself with a sword against a halberd The fencer with the sword is advised to hold it firmly in the hand, and to grasp the middle of the blade with his left hand. If the enemy throws to the inside, you should parry with your right and perform an inquartata with your body. If he throws to the outside you should parry, passing with your left foot to his right in order to grapple him, which will succeed without any doubt. |

Per difendersi contro la Labarda con Spada. Deve avertire il giocator di spada, che deve tenere la spada forte in mano e pigliar la Spada con la mano sinistra nel mezo della lama, se lʼinemico tira di dentro para con la destra e inquarta la vita se tira per difouri para e passa il sinistro piede al destro e vada alla presa senza dubio alcuno li ariuscirà. | |

Sword and cloak, sword and buckler Once the student has a good understanding of the sword alone, having taken lessons from a good master, he will be able to quickly and very easily learn the sword and dagger, sword and cape and sword and targa, noting that all three consist of but one play. He has only to ensure that all of his body is over his left foot, and that the sword is held at his thigh, as low as possible while still being usable. As for his left hand, the point of the dagger should be aimed at the enemy's throat, seeking to unsettle the enemy, so he leaves himself open to a straight thrust either to the outside or inside, whichever is easiest. He should take practice defending against attacks from a good fencer for at least fifteen days, in order to learn how to parry with a dagger in his left hand, and likewise with the cape, targa and hat. |

Spada e capa, Spada e brochiere. Quando il Scolaro averà bona congnitione di Spada sola avendo auto lettione da bon Maestro facilissimamente potrà imparar con brevità Spada e pugnale, spada e capa, spada e targa avertendo che tutte tre sono un sol gioco basta solo che si assicuri tutto il corpo sopra il piede sinistro, e la spada la porti con la mano destra alla cossiia più bassa che polle usarsi & alla sinistra il pugnale che guardi con la punta alla golla del nemico cercando di scomponere il nemico e lasciarsi di botta dritta ò per fora ò di dentro che sarà più facile facendosi tirare almeno prima 15. giorni da un bon giocatore per imparare à parare con la mano sinistra il pugnale, e cosi farai di Tabaro, di Targa, e di Capello. | |

Method of wielding the halberd against a sword, or in the midst of many swords If it happens that you must retrieve a halberd from your house or workshop to confront a sword, you should grasp the bottom of the halberd with your right hand, with your left hand in the middle. Your right foot should be back and your left foot forward, with your right arm well withdrawn. When you release a thrust you should immediately pull your attack back, and you should never swing the halberd when you know that the swordsman is accomplished, because he will be able to close to the grapple with ease. In wishing to join a combat with a halberd you should grasp it a palmo from its head. By then using montanti, while moving around at speed, you can enter into the fray without danger, the halberd being no more than a palmo taller than its wielder. |

Modo di manegiar la Labarda contro la Spada ò in mezo una quantità di Spade. Quando ti succedesse di cavar fori di tua botega ò casa la Labarda contro la Spada deve pigliar con la mano destra in fondo della Labarda con la sinistra in mezo il piede destro dietro, & il sinistro avanti ritirarsi ben adietro con il brazzo destro, e quando tiri la stocata tornerai subito à dietro con il tuo colpo, e mai non darai bastonate con la Labarda quando sai che il giocator di spada la sà manegiare che ti verà facilmente alla presa. Volendo spartire con la Labarda una costione si piglia la Labarda un palmo vicino. l fero poi con li montanti essendenti girandoti à torno con velocità tù potrai entrar nel mezo senza tuo pericolo non essendo la Labarda un palmo più alta di quello che la manegia. | |

The rule for the two-handed spadone against multiple swords This is applies both to a two-handed spadone and to long sword. Finding yourself assailed by enemies, and supposing that there are many of them, the situation demands nothing else but attacks like those of a desperate man, that is to say you must enter liberally into the fray. You should never throw thrusts with the point, except at an opponent who seems weaker, instead throwing roversi, such attacks keeping you always in motion, this being the true method of defending yourself. |

Regola di Spadone à due mano contro à più Spade. Tanto vol dire Spadone a due mani quanto ancora con una Spada longa, e trovandoti assaltato da nemici, e che fossero assia in questa occasione non vol altro che li colpi da disperato cioè entrar liberamente nel mezo, e non tirar mai di punta se non à chi ti pare che sia più debole mà con roversi tali cortelate tenendoti sempre in giro, che questo sarà il vero modo di difenderti. | |

To defend yourself against one with a great spirit, but who possesses little knowledge of fencing In all the world where I practised, I heard of many instances of men with no knowledge of fencing having killed valiant men. Here I will reflect, and say that it is possible, but not as easy as some believe, because knowing a little is better than having a lot. If I had a great spirit without the art, I would say that the art can achieve more than a great spirit, because in having a great spirit without posture, tempo and measure I would never in any way be accomplished. Having to draw my sword from its sheath, I would always pray that heaven might send me an opponent with great spirit but no art (rather than a phlegmatic one with more art than me) because when you are beset by a misadventure such as this you can overcome it without danger. You should first however try and avoid drawing your sword against one who understands little of the art. If you are wounded your entire reputation is lost but if you wound or kill him it will grant you no honour. If you must draw your sword though, never jest with him or throw cuts, because in not understanding the danger he could charge forward, or leave himself in front of you, whereupon he might shame you. I advise instead that you stand put yourself well in guard and stay covered. It he strikes desperately let him throw, and if he enters into measure you should retreat while always in guard. In the end, after he has thrown ten or twelve thrusts without effect, you can either wound him if you wish, or take his sword by coming to the grapple and leave him for the ignorant that he is. Reason will be yours however, as reason is the foundation of the art of the sword, since it it said that reason conquers all. This being so, I will now give some important advice, from a case I saw in Naples. A great personage, who had completed twenty four combats without ever being injured, was wounded by a young lad of tender years, who to his great shame took his life. May this instance therefore serve as an example to all those who carry a sword at their side, that it is always better to be circumspect and avoid such situations. |

[7] Per difendersi da un gran core, mà che possieda la scherma poco. Per tutto il mondo, che hò praticato intesi à dir moltissimi casi cioè, che molti [8] senza sapere lʼarte della scherma abiano amazzato molti bravi hominii, io qui faccio una reflessione, e dico che pol essere, mà non tanto facile quanto si crede perche meglio è il poco sapere che lʼassai possedere, che io possieda gran core e che non abia lʼarte dico che lʼarte pol far più che gran core, perche io avendo il gran core senza pianta ne tempo ne misura non sarò mai niente di bene; pregai sempre il Cielo, che avendo da cavar la Spada dal fodro mi mandassi un gran core senza lʼarte, e non un flematico con più arre di me, perche dico che quando ti succedesse tal disgratia ti poi tegolare senza pericolo, & è questo prima devi schivar lʼoccasione di cavar la Spada con uno che intende poco lʼarte, perche se ti ferisse perdi tutta la tua reputatione, e se lo ferisse lui ò lo mazzi non aquistarai niente di onore è succedendoti di cavar la Spada non scherzar mai con lui ne con tagli, perche non conoscendo il pericolo si pol investire ò lassarsi di incontro e ti pol svergognare, ma dico che si deve ben piantarsi in guardia, e coprirsi, è se tira da disperato lascialo tirare è se entra nella misura tù ritirati in pianta sempre, che al fine avendo tirato dieci ò dodeci stochate senza cognitione, ò lo ferirai se voi, ò li piglierai la spada di mano venendoli alla presa, e lo lasciarai da ignorante come è, avendo però tu la ragione, che è base fondamentale della Spada, perche si dice che la ragione vince tutto, che sia vero quì darò un gran consiglio à tutti dʼun caso che ò veduto in N. di un gran personaggio, che avendo fatto venti quatro dovesi tutti à guera fornita senza mai esser ferito, e un giovineto di tenera età con grandissima sua vergogna lo privò di vita; servirà dunque questo caso dʼesempio à tutti, che chi porta Spada al fianco si deve stimare è sempre schivar lʼoccasione. | |

When combat takes place at night The rule for combat at night is as follows. You should never thrust except with your foot, and you should seek your enemy's sword by sound and with your sword, and once you find it releasing your thrust over its edge. A cape is better than a targa, for those who know how to use it. |

Quando succede la costione di notte. La regola di far costione di notte è questa, che non si tirano mai stocate se non con il piede, e con la voce, e con la spada si cercha quella quella del nemico e trovandola si lassa sopra del suo filo la stoccata, & è bono aver el ferarolo meglio della Targa, à chi la sà maneggiare. | |

To learn the play of the flag Firstly your flag should be the same height as you, and be well counterbalanced both with lead and wood, so that the whole flag weighs as much as the palmo of lead. Every step that you take should be accompanied by a flourish of the flag, and you should practice with your left as well as your right. In this manner you can also learn without difficulty to play with two flags. |

Per imparar à giocar la Bandiera. Prima la Bandiera che farai, deve esser tanto alta quanto sei tù, e deve essere ben contrapesata tanto di piombo quanto di legno, tanto deve pesar un palmo del piombo quanto tutta lʼAsta & a tutte le tue passate che farai fa li sempre fare il scartosso alla Bàndiera, & impararai tanto con la destra quanto con la sinistra, e cosi potrai imparare à giocar ancora due con faciltà. | |

Every sort of guard should be good for those with some knowledge, but I say the Italian guards are the best. |

Tutte le sorte de guardie devono essere buone à quelli che sano qualche cosa dico lʼItaliane esser le meglio. | |

Those who wish to describe everything in great detail are like those who would seek the Phoenix at the bottom of the sea, since I am sure that if they searched that vast ocean, they would do so in vain. |

Chi volesse descrivere il tutto minuto per minuto sarebbe come chi volesse andar cercando la Fenice nel fondo del mare, che sò certo che quando cercasse quel gran Oceano cercarebbe invano. | |

It is better to do one thing well, and let everyone take stock, etc. |

Facciamo una cosa ben fatta che ogni uno pigli bene le sue misure &c. | |

THE END. |

IL FINE. |

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Images | Achille Marozzo | Opera Nova | |

| Translation | Piermarco Terminiello | The School of the Sword | |

| Transcription | Piermarco Terminiello | Index:L'Arte maestra (Carlo Giuseppe Colombani) |

Additional Resources

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Roberto Lasagni. Dizionario biografico dei Parmigiani. Trans. Piermarco Terminiello. Parma: PPS Editrice, 1999.