|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Nicoletto Giganti"

m (Updated translation link) |

(Translation brought up-to-date with latest PDF) |

||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

| TO THE LORD READERS,<br/>ALMORO LOMBARDO<br/>Son of the Most Renowned Lord Marco. | | TO THE LORD READERS,<br/>ALMORO LOMBARDO<br/>Son of the Most Renowned Lord Marco. | ||

| − | Wanting to write on the matter of arms, although the author does not mention that it is a science, to me it appears a necessary thing, Lord Readers, to treat with what share it has, and of | + | Wanting to write on the matter of arms, although the author does not mention that it is a science, to me it appears a necessary thing, Lord Readers, to treat with what share it has, and of which name it would adorn itself so that everyone knows its greatness, dignity, and privilege.<br/> |

| − | Whereupon first some students of this this most noble science read and discuss the most learned and easy observations of this valorous and knowledgeable professor Nicoletto Giganti, I, by observing the rule and general precept of | + | Whereupon first some students of this this most noble science read and discuss the most learned and easy observations of this valorous and knowledgeable professor Nicoletto Giganti, I, by observing the rule and general precept of a person who wants to address anything, will come to the definition, and then to the general division of this word Science, from which it will be possible for two things to finally be recognized by everyone, showing us that this beautiful profession is science.<br/> |

| − | Science therefore, is a certain and manifest | + | Science, therefore, is a certain and manifest knowledge of things that the intellect acquires. It is of two sorts, that is, Speculative and Practical. Speculative is a simple operation of the intellect around its own object. Practical only consists in the actual workings of the intellect.<br/> |

| − | Speculative is divided in two parts, that is, in | + | Speculative is divided in two parts, that is, in Real Speculation and Rational Speculation. The Real aims at the reality of its object, which demonstrates its essence on its exterior. The Rational consists of those things that only the intellect administers and does not extend itself to other goals.<br/> |

| − | Physics is a | + | Physics is a Real Speculative Science that only aims at moving and natural things, like the elements. Mathematics is a Real Speculative Science that only extends itself to continuous and discrete quantity. Continuous like lines, circles, surfaces, the measures of which deal with Arithmetic.<br/> |

| − | Grammar, Rhetoric, Poetry, and Logic are | + | Grammar, Rhetoric, Poetry, and Logic are Rational Speculative Sciences.<br/> |

Practical Science is divided in two: Active and Workable. Active is Ethics, Politics, and Economics. Workable can be divided in seven others, called mechanical, which are these: Woolcraft, Agriculture, Soldiery, Navigation, Medicine, Hunting, and Metalworking.<br/> | Practical Science is divided in two: Active and Workable. Active is Ethics, Politics, and Economics. Workable can be divided in seven others, called mechanical, which are these: Woolcraft, Agriculture, Soldiery, Navigation, Medicine, Hunting, and Metalworking.<br/> | ||

| − | Now, coming to what I promised above about this noble science, I will go over its qualities and nature, discussing | + | Now, coming to what I promised above about this noble science, I will go over its qualities and nature, discussing whether it is Speculative or Practical science. In my opinion I say that it is Speculative, and prove it with diverse reasons. That it is science there is no doubt, because it is not acquired if it is not mediated by the operation of the intellect, from which it is born. That it is Speculative is certain since it does not consist in anything other than simple knowledge of its object, as I will be discussing below.<br/> |

| − | The object of this science is nothing more than parrying and wounding. The knowledge of those two things is a work of the intellect, and moreover professors of this science do not extend it further | + | The object of this science is nothing more than parrying and wounding. The knowledge of those two things is a work of the intellect, and moreover with intelligence professors of this science do not extend it further than the knowledge of them, which cannot be understood at all unless one first has knowledge of tempi and measures, or rather, knowledge of Feint, Disengage, or resolution without knowledge of tempi and measures. These are all operations of the intellect, and moreover outside of this knowledge the intellect does not extend, because as I have said the aim of these professions is understanding parrying. We will see if it is Real Speculative or Rational Speculative.<br/> |

| − | Considering, it cannot be | + | Considering this, it cannot be Rational, and the reason is this: because if it is indeed an operation of the intellect, nevertheless it spreads further, wherefore I find it to be Real Speculative. Real, because the knowledge of its aim is shown to us outwardly by the intellect. As the understanding of wounding and parrying, with tempi, measures, feints, disengages, and resolutions, even though they are operations of the intellect, they cannot be understood if not outwardly, and this exterior consists in the bearing of the body and of the Sword in the guards and counterguards, which all consist of circles, angles, lines, surfaces, measures, and of numbers. These things, which must be observed, can be read about in Camillo Agrippa and in many other professors of this science. Note that just as those operations of the intellect without an exterior operation cannot be shown, so these exterior operations cannot be understood without the operations of the intellect first, in a manner that this science, which derives from the intellect, cannot be understood if not outwardly. Neither can one understand outwardly without operations of the intellect. These operations seek to understand the greatness, excellence, and perfection of this profession, and always come united. As there can never be Sun without day, nor day without Sun, never will there be those without these, nor these without those. In the end we see that it is Real Speculative Science.<br/> |

| − | This science of the Sword, or of arms, is a | + | This science of the Sword, or of arms, is a Real Speculative Mathematic Science, and Geometric, and Arithmetic. Geometric because it consists in lines, circles, angles, surfaces, and measures. Arithmetic because it consists of numbers. There is no motion of the body that does not make an angle or constraint. There is no motion of the Sword that does not travel in a line. There is neither guard nor counterguard that does not go by the number. The observations of these things all depend on knowledge of tempi and measures, whence I conclude that this most noble science is Real, Mathematic, Geometric, and Arithmetic, as I said a little above.<br/> |

| − | + | Perhaps some inquisitive person arguing over this could say that the science of arms is a Practical Science with this reason: that being a Practical Science, a science which not only extends to the knowledge of its own object but to the operation of it, this science is therefore Practical, and not Speculative. To this objection I respond: all things have from nature their operation. Three are the sorts of their operations; some are internal, and these have their being in pure and simple intellect, and result from a Rational Speculative. Some are internal and external, and these have a commonality inside the intellect and outside, and are born from a Real Speculative. Some are completely external, and these have their being outside the intellect entirely and depend on a Practical Science, and are either Active or Workable. The Speculative Workable Real Science is no different from the Practical Science other than in this: the Real Speculative operates outwardly on its object and through the knowledge of that serves the intellect. The Practical Science not only cannot operate on its object if not outwardly, it cannot even come to the knowledge of it if not outwardly. The science of arms has the knowledge of its object in the intellect, and even though it operates outwardly, it cannot be said that it is Practical, but instead Speculative Real Science.<br/> | |

| − | We have therefore seen that it is a science and it is Mathematics, of Geometry and Arithmetic, since it consists of numbers, lines, and measures. The author does not make mention of this in his observations, | + | We have therefore seen that it is a science and it is Mathematics, of Geometry and Arithmetic, since it consists of numbers, lines, and measures. The author does not make mention of this in his observations, so that from him learned persons and those with no study may acquire some profit. Therefore, from his present figures and noted lessons, without learning to understand the multiplicity of lines, circles, angles, surfaces which would rather confuse the minds of readers that do not have understanding of these studies, nor give them any instruction, without a doubt everyone will learn to understand without difficulty the tempi, measures, resolutions, feints, disengages, and the way of parrying and wounding.<br/> |

| − | As for knowing how to understand the circles, | + | As for knowing how to understand the circles, lines, and other things mentioned above, every studious person will come to understand them with exercise. I will always advise everyone to apply themselves to the study of letters before this profession, because one that has studied in order to have understanding of the necessary things around this science will better profit and will make themselves more excellent and more perfect, with much more quickness of time for the acquisition, so that he can understand the aforesaid things of the guards, counterguards, covered just as uncovered. He that has not studied will not obtain it so easily, which, if he can learn it well, he will not therefore acquire understanding of this science without length of time and continuous exercise.<br/> |

| − | This profession is of | + | This profession is of so much dignity and consideration. What decorum does it seek? What reputation and how much honour must one give it? Under what obligation is one that carries the sword and makes a profession of it? I say its dignity and consideration derive totally from its qualities, and with the division of the same one can come to understand.<br/> |

| − | This science of the sword is divided into three parts . The first is divided in two: | + | This science of the sword is divided into three parts. The first is divided in two: Natural and Artificial. Natural is a demonstrative discourse man makes use of naturally in parrying and wounding, since with his own ingenuity he proceeds with those goals extracting what mother nature administers to him for his needs. Here is what many men of courage and spirit have shown great measure of in their contentions with men of great art and knowledge. The Artificial is that which with ingenuity and long use and exercise found under short rules and impossible methods different manners of parrying and wounding with the above noted things. Accordingly, coming to some occasion the man extracts from this the real ends of his safety. In his lessons the author shows great understanding of those two qualities, and the reader will be fully satisfied with them.<br/> |

| − | The second part is this: the | + | The second part is this: the Artificial science of the sword is divided in two, Demonstrative and Exercised. The Demonstrative is that which demonstrates the proper method, and aims at knowledge of parrying and of wounding, by firm foot just as with the pass, when one must bind the enemy and when one must draw back by way of those lines, circles, or circumstances you remember from above, for which the intellect governs and imparts the many and multiple postures and counterpostures of the body. The Exercise is the same as the Demonstrative which, since we have acquired it, we apply to the understanding of a thousand warnings. There is no difference between them, except that the Demonstrative is self-contained, and the Exercised extends to serve the understanding of different things.<br/> |

The third part is this: the Demonstrative science of the sword is divided in two: the first Demonstrative consists of uncomplicated ends, that is, in simple ends, or composite, that unite in themselves more ends for the same Demonstratives of various occurrences, such as being outside of measure with the arms open, the weapons high or low. These ends require incomplete ends, that is, ends not understood by the enemy. They are called simple because they are natural. They are called composite because they have in themselves many considerations, and these are divided into the first and the second concepts.<br/> | The third part is this: the Demonstrative science of the sword is divided in two: the first Demonstrative consists of uncomplicated ends, that is, in simple ends, or composite, that unite in themselves more ends for the same Demonstratives of various occurrences, such as being outside of measure with the arms open, the weapons high or low. These ends require incomplete ends, that is, ends not understood by the enemy. They are called simple because they are natural. They are called composite because they have in themselves many considerations, and these are divided into the first and the second concepts.<br/> | ||

| − | The first concepts are real things that are first learned from the intellect, like parrying and wounding, and these come in the first intention. The second concepts are formed from the intellect, and these make the second of our intentions, the knowledge in order to be able to wound and parry, and are made through the first, for the reason that immediately when our intellect has learned this aim of wounding and parrying, it soon discusses how this can be done in a different manner and | + | The first concepts are real things that are first learned from the intellect, like parrying and wounding, and these come in the first intention. The second concepts are formed from the intellect, and these make the second of our intentions, the knowledge in order to be able to wound and parry, and are made through the first, for the reason that immediately when our intellect has learned this aim of wounding and parrying, it soon discusses how this can be done in a different manner and with different methods.<br/> |

| − | The second Demonstrative consists | + | The second Demonstrative consists of the complex ends, that is, of ends that unite in themselves more ends for the same demonstratives, and these aims either united in measure or separate in distance demonstrate their ends, like being in guard with the weapons closed demonstrates, or the posture or counterposture of the body in measure or at distance which is the aim of that, and how many things can be done with that working. For this reason one sees of how much consideration this beautiful science is for its qualities, and for the aims it contains.<br/> |

| − | Therefore just as it is of great dignity, because it is real Speculative Mathematics of Geometry and Arithmetic, and for many parts found under itself, such decorum and reputation I say it requires. No other will be the decorum and reputation if not this. And also considering, o Readers, that this science for the most part is found in royal courts, and of every Prince, in the most famous Cities, studied by Barons, Counts, Knights, and persons of great quality, and for no other | + | Therefore, just as it is of great dignity, because it is real Speculative Mathematics of Geometry and Arithmetic, and for many parts found under itself, such decorum and reputation I say it requires. No other will be the decorum and reputation if not this. And also considering, o Readers, that this science for the most part is found in royal courts, and of every Prince, in the most famous Cities, studied by Barons, Counts, Knights, and persons of great quality, and for no other reason if not because just as it is noble, it excites and inflames our spirits to great things, to learn, and to heroic actions, to match of the virtue of the spirit, the valour of the body, the vigour of the strength, and the skill of the person. This always seeks parity, and does not allow any blemish to it. It wants to be understood and learned, but not to be professed for every folly one takes up. It flees the disputes of villainous persons. It does not do all that it can. It shows itself at the time and place. It avoids the practices of excess. It is of few words. It desires a serious comportment, a lively eye, an honoured dress, and a noble practice. This is enough about its decorum and reputation. In regard to the honour that it requires, advising that the observance of all the said things is honour to this profession, it remains only to be said what obligation one who carries the sword is under.<br/> |

| − | We will pass by the aims of these Duellists who, just as they have badly learned the said profession, so I say with many of their propositions they degrade it and have reduced it to such an unhappy state that it not only casts aside | + | We will pass by the aims of these Duellists who, just as they have badly learned the said profession, so I say with many of their propositions they degrade it and have reduced it to such an unhappy state that it not only casts aside the virtuous life which demands such a science, and human discourse, and every reason, but forgetting the great God, and themselves as a consequence, their unjust aims can only possess it for the damnation of their spirits, postponing the divine church for their diabolical thoughts.<br/> |

| − | This profession, o Readers, puts one who practices it under obligation to learn, and considering this wants to be used in four occasions: the first for | + | This profession, o Readers, puts one who practices it under obligation to learn, and considering this wants to be used in four occasions: the first for Faith, then for Country, for defence of one’s own life, and finally for honour. It always wants to be a defender of reason, never taken hold of in order to do wrong, and one who does so makes an injury to this profession. Neither will a man of honour have held onto a wrong in order to fight, but will only do so for the said things. It is necessary to have occasion because fighting without one is a thing of the foolish and drunk. Some as soon as they have acquired some beginning of this mock, putting the Sword at their side, and using a thousand insolences, either stop or wound someone, and at such time kill some miserable person, believing themselves to have acquired honour and fame. They do evil, because other than making an outrage to the nobility of this which must not be put in use without reason, they offend the just God and themselves.<br/> |

In order to not come to tedium I will not continue, but only exhort each to study such a noble and real science, begging him to keep in mind the underwritten observations of our noble professor, and practice in it, because with brevity of time one can acquire no small profit, observing how much it suits honour, glory, and greatness themselves.<br/> | In order to not come to tedium I will not continue, but only exhort each to study such a noble and real science, begging him to keep in mind the underwritten observations of our noble professor, and practice in it, because with brevity of time one can acquire no small profit, observing how much it suits honour, glory, and greatness themselves.<br/> | ||

| ALLI SIG. LETTORI,<br/>ALMORO LOMBARDO<br/>fù del Clarissimo Signor Marco. | | ALLI SIG. LETTORI,<br/>ALMORO LOMBARDO<br/>fù del Clarissimo Signor Marco. | ||

| Line 165: | Line 165: | ||

Dated the 31st of October, 1605. | Dated the 31st of October, 1605. | ||

| − | + | D. Santo Balbi<br/> | |

| − | + | D. Gio. Giacomo Zane<br/> | |

| − | + | D. Piero Barbarigo<br/> | |

Captains of the Most Illustrious Council of X. | Captains of the Most Illustrious Council of X. | ||

| Line 204: | Line 204: | ||

| December 23, 1605 in Senate | | December 23, 1605 in Senate | ||

| − | The power is granted to our faithful Nicoletto Giganti, Venetian, that other than him or one at his behest, it is not permitted for the space of the next thirty years to venture to print in this City, nor any other City, Land, or place of our Domain, nor printed elsewhere to conduct or sell in Our Domain the book composed by him, titled School, or Theatre, under pain of losing printed work, or conducted, which is by the aforesaid Nicoletto Giganti, and being obliged to observe what is required by our law in matters of Printing, of paying three hundred ducats: a third to our | + | The power is granted to our faithful Nicoletto Giganti, Venetian, that other than him or one at his behest, it is not permitted for the space of the next thirty years to venture to print in this City, nor any other City, Land, or place of our Domain, nor printed elsewhere to conduct or sell in Our Domain the book composed by him, titled School, or Theatre, under pain of losing printed work, or conducted, which is by the aforesaid Nicoletto Giganti, and being obliged to observe what is required by our law in matters of Printing, of paying three hundred ducats: a third to our Arsenal, a third to the Magistrate that makes the execution, and the other third to the complainant.<br/> |

| 1605. a 23. di Decembre in Senato | | 1605. a 23. di Decembre in Senato | ||

| Line 230: | Line 230: | ||

| GUARDS AND COUNTERGUARDS | | GUARDS AND COUNTERGUARDS | ||

| − | It is necessary for someone wanting to become a professor of the science of arms to understand many things. To give my lessons a beginning, I will first begin to discuss the guards and counterguards, or postures and counterpostures, of the sword. This, because coming to some incident of contention it is first necessary to understand this to be able to secure oneself against the enemy. To place oneself in guard then, many things must be observed, as can be seen in my figures: standing firm over the feet, that are low and the foundation of the entire body, in a just pace, restrained rather than long in order to be able to increase it, holding the sword and dagger strongly in the hands, the dagger now high, now low, now extended, the sword now high, now low, now on the right side, ready to parry and wound so that the enemy throwing either a thrust or cut can be parried and wounded in the same tempo, with the vita disposed and ready because | + | It is necessary for someone wanting to become a professor of the science of arms to understand many things. To give my lessons a beginning, I will first begin to discuss the guards and counterguards, or postures and counterpostures, of the sword. This, because coming to some incident of contention it is first necessary to understand this to be able to secure oneself against the enemy. To place oneself in guard then, many things must be observed, as can be seen in my figures: standing firm over the feet, that are low and the foundation of the entire body, in a just pace, restrained rather than long in order to be able to increase it, holding the sword and dagger strongly in the hands, the dagger now high, now low, now extended, the sword now high, now low, now on the right side, ready to parry and wound so that the enemy throwing either a thrust or cut can be parried and wounded in the same tempo, with the vita disposed and ready because lacking the disposition and readiness of that it will be an easy thing for the enemy to put it into disorder with a dritto, a riverso, a thrust, or in another manner, and even if such a person parried they would remain in danger. It is advised to let the dagger watch the enemy’s sword, because if the enemy throws it will parry that. Always aim the sword at the uncovered part of the enemy so that the enemy is wounded when throwing. This is all the artifice of this profession. Moreover, one must note that all the motions of the sword are guards to one who knows them, and all guards are good to one who practices, as on the contrary no motion is a guard to one who does not understand, and they are not good for one who does not know how to use them. This profession does not require more than science and exercise, and this exercise presents the science. Placing oneself uncovered in guard is artifice and done because the enemy disorders themselves when throwing and ends up in danger. Placing oneself covered is also artifice because in binding the enemy can be wounded. In this way it is understood that every guard aids one who has skill and understands, and no guard is valuable to he who does not have skill or understanding. This is enough about the guards. As for the counterguards, be advised that one who has knowledge of this profession will never place themselves in guard, but will seek to place themselves against the guards. Wanting to do so, be warned of this: one must place oneself outside of measure, that is, at a distance, with the sword and dagger high, strong with the vita, and with a firm and balanced pace, then consider the guard of the enemy. Afterwards approach him little by little with your sword binding his for safety, that is, almost resting your sword on his so that it covers it because he will not be able to wound if he does not disengage the sword. The reason for this is that in disengaging he performs two actions. First he disengages, which is the first tempo, then wounding, which is the second. While he disengages, in that same tempo he can come to be wounded in many ways before he has time to wound, as one will see in the figures of my book. If he changes guard for the counterguard it is necessary to follow him along with the sword forward and the dagger, always securing his sword, because in the first tempo he will always have to disengage the sword and end up wounded. It will never be possible for him to wound if not with two tempi, and from those parrying will always be a very easy thing. This is enough about guards and counterguards. |

| DELLE GUARDIE, E CONTRAGUARDIE. | | DELLE GUARDIE, E CONTRAGUARDIE. | ||

| Line 241: | Line 241: | ||

| TEMPO AND MEASURE | | TEMPO AND MEASURE | ||

| − | One cannot know how to place oneself in guard, or against the guard, nor how to throw a thrust, an imbroccata, a mandritto, or a riverso, nor how to turn the wrist, nor how to carry the body well, or to best control the sword, or say one understands parrying and wounding, but by understanding tempo and measure which, of one who does not understand, even though they parry and wound, it could not be said that they understand parrying and wounding, because such a person in parrying as in wounding can err and incur a thousand dangers. Therefore, having discussed the guards and counterguards it remains to discuss tempo and measure in order to know how to, then to accommodate an understanding of when one must parry and wound. | + | One cannot know how to place oneself in guard, or against the guard, nor how to throw a thrust, an imbroccata, a mandritto, or a riverso, nor how to turn the wrist, nor how to carry the body well, or to best control the sword, or say one understands parrying and wounding, but by understanding tempo and measure which, of one who does not understand, even though they parry and wound, it could not be said that they understand parrying and wounding, because such a person in parrying as in wounding can err and incur a thousand dangers. Therefore, having discussed the guards and counterguards it remains to discuss tempo and measure in order to know how to, then to accommodate an understanding of when one must parry and wound. Therefore, measure means when the sword can reach the enemy. When it cannot it is called being out of measure. Tempo is understood in this way: if the enemy is in guard, one needs to place oneself outside of measure and advance with one’s guard, securing oneself from the enemy’s sword with one’s own, and put one’s mind on what he wants to do. If he disengages, in the disengagement one can wound him, and this is a tempo. If he changes guard, while he changes is a tempo. If he turns, it is a tempo. If he binds to come to measure, while he walks before arriving in measure is a tempo to wound him. If he throws, parrying and wounding in a tempo also is a tempo. If the enemy stays still in guard and waits and you advance to bind him and throw where he is uncovered when you are in measure, it is a tempo, because in every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and vita such as changing guard, is a tempo in such a way that all these things are tempi: because they contain different intervals, and while the enemy makes one of these motions, he will certainly be wounded because while a person moves they cannot wound. It is necessary to understand this in order to be able to wound and parry. I will be demonstrating more clearly how one must do so in my figures. |

| DEL TEMPO, ET DELLA MISURA. | | DEL TEMPO, ET DELLA MISURA. | ||

| Line 250: | Line 250: | ||

|- | |- | ||

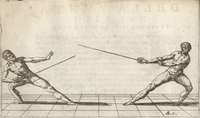

| [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 04 Figure 01.png|200px|center|Figure 1]] | | [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 04 Figure 01.png|200px|center|Figure 1]] | ||

| − | | The | + | | The method of throwing the stoccata |

| − | Now that we have discussed the guards, counterguards, measures, and tempi, it is a necessary thing to demonstrate and give | + | Now that we have discussed the guards, counterguards, measures, and tempi, it is a necessary thing to demonstrate and give knowledge of how to hold the vita in order to throw a stoccata and escape since wanting to learn this art it is first necessary to understand how to carry the vita and throw stoccate that are long, as seen in this figure, and all is in throwing brief, strong, and immediate stoccate, withdrawing backward outside of measure. To throw the long stoccata, one must place themselves in a just and strong pace, short rather than long in order to be able to extend, and in throwing the stoccata stretch the sword arm, bending the knee as much as possible. The proper method of throwing the stoccata is after placing oneself in guard, it is necessary to throw the arm first, then extend forward with the vita in one tempo so that the stoccata arrives and the enemy does not perceive it. If the vita were brought forward first the enemy could notice it and, availing himself of the tempo, parry and wound in one tempo. In withdrawing backward one must first carry back the head because behind the head will follow the vita, and afterwards the foot. Carrying the foot back first and leaving the head and vita forward keeps them in great danger. Therefore, to learn this art well one must first practice throwing this stoccata. Knowing it one will learn the rest easily, and not knowing it the contrary. Be advised, Lord readers, that I will place this method of throwing the stoccata many times in my lessons at appropriate times. This I know makes the lessons better understood. It is not said of me that I say one thing many times. |

| Del modo di tirar la Stoccata. | | Del modo di tirar la Stoccata. | ||

| Line 263: | Line 263: | ||

| Why begin with the single sword | | Why begin with the single sword | ||

| − | In my first book of arms I proposed to discuss only two kinds of weapons, that is, single sword and sword and dagger, setting aside discussion of certain others. If it pleases my Lord, I will illuminate all sorts of weapons as soon as possible. Because the sword is the most common and most used weapon of all I wanted to begin with it, since one who understands playing with the sword well will also understand the handling of almost every other kind of weapon. Since it is not usual in every part of the world to carry the dagger, targa, or rotella, and fighting with single sword | + | In my first book of arms I proposed to discuss only two kinds of weapons, that is, the single sword and sword and dagger, setting aside discussion of certain others. If it pleases my Lord, I will illuminate all sorts of weapons as soon as possible. Because the sword is the most common and most used weapon of all I wanted to begin with it, since one who understands playing with the sword well will also understand the handling of almost every other kind of weapon. Since it is not usual in every part of the world to carry the dagger, targa, or rotella, and as fighting with single sword occurs many times, I urge everyone to first learn to play with the single sword, despite everything one might have in frays, such as the dagger, the targa, or the rotella, since occurring as it many times does that the dagger, targa, or rotella falls from his hand, a man would have to defend himself and wound the enemy with the single sword, and because one who practices playing with the single sword will understand just as well how to parry and wound as one who has sword and dagger. |

| Perche cominci dalla Spada sola. | | Perche cominci dalla Spada sola. | ||

| Line 274: | Line 274: | ||

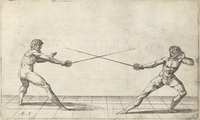

| GUARDS, OR POSTURES | | GUARDS, OR POSTURES | ||

| − | Many are the guards of the single sword, and many still the counterguards. In my first book I will not teach any other than two sorts of guards and counterguards, of which you will be able to avail yourself for all lessons of the figures of this book. Therefore, before coming to do | + | Many are the guards of the single sword, and many still the counterguards. In my first book I will not teach any other than two sorts of guards and counterguards, of which you will be able to avail yourself for all lessons of the figures of this book. Therefore, before coming to do what you desire, you must go to bind the enemy outside of measure, securing yourself from his sword by placing your sword over his in a way that he cannot wound you if not with two tempi: one will be the disengage of the sword, and the other the wounding of you. In this way you will accommodate yourself against all the guards, either high or low, according to how you see your enemy accommodated, always taking care to not give opportunity and occasion to the enemy to be able to wound you in a single tempo. You will do this if you take care that the point of his sword is not toward the middle of your vita, so that pushing his sword forward quickly and strongly it will not be possible for him to wound you. Therefore, cover the enemy’s sword with yours as you see in this figure, so that the enemy’s sword is outside of your vita and he cannot wound you if he does not disengage his sword. You will settle yourself with your feet strong, stable with your vita, with your sword arm extended and strong in order to parry and wound, as the figure shows you. If you were to see the enemy in a high or low guard and did not place yourself in a counterguard and secure yourself from his sword you would be in danger even if your enemy had lesser science and lacked practice compared to you, since you could produce an incontro and both wound each other, or he could place you on the defensive, or rather, in obedience, with feints or disengages of the sword or other things that are possible. If you secure yourself from the enemy’s sword as I have said above he will not be able to move nor do any action that you will not see and have opportunity to parry. These figures here are two guards with the swords forward, and two counterguards covering the sword. One is made going to bind the enemy on the inside and the other going outside, as these figures show you, and as I will go about showing you in the subsequent lessons. |

| GUARDIE, OVERO POSTURE. | | GUARDIE, OVERO POSTURE. | ||

| Line 285: | Line 285: | ||

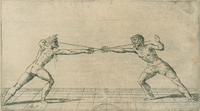

| EXPLANATION OF WOUNDING IN TEMPO | | EXPLANATION OF WOUNDING IN TEMPO | ||

| − | This figure teaches you to wound your enemy in the tempo he disengages his sword. You do this by approaching to bind the enemy outside of measure, placing your sword over his to the inside as the figure of the first guard shows you | + | This figure teaches you to wound your enemy in the tempo he disengages his sword. You do this by approaching to bind the enemy outside of measure, placing your sword over his to the inside as the figure of the first guard shows you so that he will not be able to wound you if he does not disengage the sword. Then, in the same tempo that he disengages to wound you, push forward your sword, turning your wrist in the same tempo so that you wound him in the face as is seen in the figure. In the case that you were to parry and then wound it would not be successful, since the enemy would have tempo to parry and you would be in danger, but if you enter immediately forward with your sword in the tempo he disengages his, turning your wrist and parrying, the enemy will have difficulty parrying. This done, the enemy wounded or not, to secure yourself return backward outside of measure with your sword over that of the enemy, never abandoning it.<br/> |

| − | In the case that the enemy does not disengage his sword to wound you, I want you to advance to bind him outside of measure and immediately throw him a thrust where he is uncovered, returning | + | In the case that the enemy does not disengage his sword to wound you, I want you to advance to bind him outside of measure and immediately throw him a thrust where he is uncovered, returning backward outside of measure and resting your sword over his. |

| DICHIARATIONE DI FERIR DI TEMPO. | | DICHIARATIONE DI FERIR DI TEMPO. | ||

| Line 296: | Line 296: | ||

|- | |- | ||

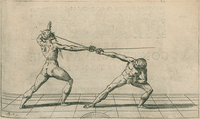

| [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 08 Figure 05.png|200px|center|Figure 5]] | | [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 08 Figure 05.png|200px|center|Figure 5]] | ||

| − | | THE PROPER | + | | THE PROPER METHOD OF GOING TO BIND THE ENEMY AND STRIKE HIM while he disengages the sword |

| − | From this figure you learn that if your enemy is in a guard with the sword | + | From this figure you learn that if your enemy is in a guard with the sword on the left side, high or low, you approach him to bind him outside of his sword outside of measure, with your sword over his so that it barely touches it, with a just and strong pace, with your sword ready to parry and wound, with lively eyes, as you see in the second figure of the guards and counterguards., You being accommodated in this way, your enemy will not be able to wound you with a thrust if he does not disengage the sword. While he disengages, turn your wrist and in the same tempo throw a stoccata at him as the fourth figure teaches you. Having thrown this stoccata, immediately in the same tempo return backward outside of measure, resting your sword over his so that if he wants to disengage anew, you will return to throw to him the same stoccata, turning your wrist as above, returning outside of measure. As many times as he disengages, that many times you will use the same method of turning your wrist and throwing the stoccata at him. To perform this game well much practice is necessary, since from this one learns to parry and wound with skill and great speed. Take care to always be balanced with your vita and to parry strongly with the forte of your sword because if your enemy throws strongly at you, parrying strongly will make him disconcerted and you will be able to wound him where he is uncovered. This must be the first lesson that one learns with the single sword, since all the others that I have placed in this book arise from it. Knowing how to do this in the tempo teaches you to parry all the cuts and resolute thrusts that can come for the head, which I will teach hand in hand in the subsequent lessons. |

| IL VERO MODO D’ANDAR A STRINGER IL NEMICO, E DARGLI, mentre cava la Spada. | | IL VERO MODO D’ANDAR A STRINGER IL NEMICO, E DARGLI, mentre cava la Spada. | ||

| Line 307: | Line 307: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

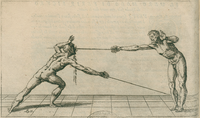

| − | | THE PROPER | + | | THE PROPER METHOD OF DISENGAGING THE SWORD |

| − | + | The two figures that were placed here above taught to wound the enemy while he disengages his sword. Because I would not leave a thing in my lessons that is not more than clear, I want to show you the method of disengaging the sword. But note that your enemy being settled in whichever sort of guard he wants, you having gone to bind him, throw a stoccata at him where he is uncovered and if he knows as much as you, you will always be with your swords equal. I want you then to disengage the sword under the hilt of that of the enemy, quickly turning your wrist and throwing a thrust in the same tempo where you find him uncovered. This is the proper and safe method to disengage the sword and wound in one tempo. If you were to disengage your sword without turning your wrist you would give a tempo and place to the enemy to wound you, as you will see quite well in exercising and trying it yourself. If the enemy were to parry return to disengage in the aforesaid way, always turning your wrist. As many times as he parries, disengage as many other times in the above way, which is safest, then throw the stoccata at him in the tempo that you disengage. This method of disengaging is no less necessary than what we taught in the explanation of the previous figure of the method of parrying, since this is the main thing that one seeks in knowing how to manage the single sword. Therefore I exhort everyone to practice well in these two things, since being in measure against the enemy, as soon as it is the tempo to disengage the sword, one would know how to disengage quickly and well, and as soon as it is the tempo of parrying, to understand parrying similarly well. | |

| DEL VERO MODO DI CAVAR LA SPADA. | | DEL VERO MODO DI CAVAR LA SPADA. | ||

| Line 320: | Line 320: | ||

| THE INSIDE COUNTERDISENGAGE OF THE SWORD | | THE INSIDE COUNTERDISENGAGE OF THE SWORD | ||

| − | In this figure another | + | In this figure another method of parrying and wounding by way of counterdisengage is represented and shown to you, which is done in this way: having covered the sword of your enemy so that if he wants to wound you he must disengage, while he disengages I want you to also disengage so that your sword returns to its first position, covering that of the enemy. But in the disengaging that you do, availing yourself of the tempo, throw a stoccata at him where he is uncovered, turning your body a little toward the right side and holding your arm stretched forward so that if he comes to wound you he will wound himself of his own accord. Having thrown the stoccata, return backward outside of measure. |

| DELLA CONTRACAVATIONE DENTRO DELLA SPADA. | | DELLA CONTRACAVATIONE DENTRO DELLA SPADA. | ||

| Line 329: | Line 329: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 10 Figure 07.png|200px|center|Figure 7]] | | [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 10 Figure 07.png|200px|center|Figure 7]] | ||

| − | | THE COUNTERDISENGAGE<br/>OF THE SWORD OUTSIDE | + | | THE COUNTERDISENGAGE<br/>OF THE SWORD ON THE OUTSIDE |

| − | This | + | This method of wounding by way of outside counterdisengage is similar to the inside counterdisengage, only there is a difference: that your enemy being in guard and you coming to bind, being outside of measure you must place yourself against his guard, securing yourself from his sword outside and making the enemy resolve himself to disengage. While he disengages, in the same tempo you will again disengage, turning the point of your sword under his together with your wrist, resting the forte of the edge of your sword and going along the edge of it, holding your arm long and extended, loosening the vita and lengthening the pace, as is seen in the figure, so you come to wound him without him sensing it. But be advised that if the enemy throws the sword strongly and you want to disengage yours so that the enemy does not reach and wound you, you need to hold your vita back in your disengage so that you stay safe. Supposing the enemy had thrown strongly, he would disconcert himself and come to wound himself on your sword. Then you will stay superior to him, being able to wound him where you parry, taking care to always hold your sword outside of your vita so that he cannot wound you. |

| DELLA CONTRACAVATIONE<br/>DELLA SPADA DI FUORI. | | DELLA CONTRACAVATIONE<br/>DELLA SPADA DI FUORI. | ||

| Line 342: | Line 342: | ||

| EXPLANATION<br/>OF THE FEINT<br/>Making a show of disengaging the sword with your wrist | | EXPLANATION<br/>OF THE FEINT<br/>Making a show of disengaging the sword with your wrist | ||

| − | The ways of wounding are various | + | The ways of wounding are various and as a consequence my lessons are also various. But don’t expect at all that I will tell all the things that are possible to do in this profession because, those being infinite, my work would be too long and would bring tedium to the Readers. However, I will untangle those things that to me appear most beautiful, most artificial, and most useful, from which arise many others easier and less artificial. Therefore, among all the methods of wounding artificially the feint, in my opinion, exceeds all others. This is nothing more than hinting at doing one thing and doing another. It is done in different ways, and they are these: I want you to place yourself on your feet, on the right side with the sword forward, with the right arm extended in order to give your enemy occasion to come to bind you. As he comes into measure with you, watch if he wants to wound you from fixed feet or instead with a pass. You will know at the disengage you make with the sword. Disengage the sword with your wrist and feint a thrust at his face, but throw wide of the enemy’s sword so that it does not find yours. If the enemy does not parry throw it resolutely so that you wound him. If he parries, in his parrying redisengage the sword and wound as you see in this figure, where the enemy carelessly wounds himself. Take care that in redisengaging you do not let the sword be found because then your plan could be in vain, and in disengaging bring the head and vita back a little in order to see what the enemy does, because if he were to throw and you had not withdrawn backward, he could produce an incontro and you would wound each other. Moreover, you are advised to run with the right edge of your sword along the edge of the enemy’s sword, turning the inside of your wrist upwards in wounding with your sword over the debole of that of the enemy. As soon as the stoccata is given, either resolute or feinted, return backward outside of measure, securing yourself as shown to you above. The feint is therefore performed in this way: first one displays the sword to either the face or chest of the enemy, and then one lengthens the arm without stepping. If the enemy parries, disengage the sword in the same tempo, accompanying it forward with the step so that you wound him unawares. If he does not parry, increase the step and strike him. This is the method of wounding by feint. |

| DELLA FINTA<br/>DICHIARATIONE<br/>Far vista di cavar la spada con il nodo della mano. | | DELLA FINTA<br/>DICHIARATIONE<br/>Far vista di cavar la spada con il nodo della mano. | ||

| Line 351: | Line 351: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | Although they appear similar, the following two figures are nevertheless different from each other since they contain different methods of feinting. Although they contain almost the same goal of wounding, and although it would have sufficed to give you a single figure to discuss and teach different methods of feinting in order to wound, to show clearly the different ways of feinting I wanted to put two of them here that differ widely from one other, which is shown to you in their explanations. |

| LE due seguente figure, benche paiano simili, sono però differenti tra loro, poiche hanno in se diversi modi di fingere, se bene hanno in se quasi un medesimo fine per ferire; & se bene havrebbe bastato mettervi una sola figura, sopra la quale si potesse discorere, & insegnare diversi modi di fingere per ferire; pure per mostrare evidentemente il diverso modo di fingere, ho voluto ponerne quì due più differenti trà loro; ilche vi dimostro nelle loro dichiarationi. | | LE due seguente figure, benche paiano simili, sono però differenti tra loro, poiche hanno in se diversi modi di fingere, se bene hanno in se quasi un medesimo fine per ferire; & se bene havrebbe bastato mettervi una sola figura, sopra la quale si potesse discorere, & insegnare diversi modi di fingere per ferire; pure per mostrare evidentemente il diverso modo di fingere, ho voluto ponerne quì due più differenti trà loro; ilche vi dimostro nelle loro dichiarationi. | ||

| [http://fechtgeschichte.blogspot.de/2014/08/das-fechtbuch-des-nicolai-giganti-in.html Text to copy over] | | [http://fechtgeschichte.blogspot.de/2014/08/das-fechtbuch-des-nicolai-giganti-in.html Text to copy over] | ||

| Line 358: | Line 358: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 12 Figure 09.png|200px|center|Figure 9]] | | [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 12 Figure 09.png|200px|center|Figure 9]] | ||

| − | | | + | | METHOD OF WOUNDING IN THE CHEST<br/>WITH THE SINGLE SWORD WHEN THEY ARE IN<br/>measure with the swords equal |

| − | The present figure is an artificial way of wounding the enemy in the chest and securing oneself from his sword so that he cannot offend while you pass to wound him. It is done in this way: | + | The present figure is an artificial way of wounding the enemy in the chest and securing oneself from his sword so that he cannot offend while you pass to wound him. It is done in this way: one needs to place themselves in guard with the sword forward on the left side and if the enemy comes to bind you and cover your sword with his let him come until he finds himself in measure with you. When he is in measure with you disengage, putting your sword inside of his, straightening the point against the enemy’s face. If he does not go to parry, wound him resolutely, going as I have said above with the right edge of yours on the edge of his, turning your wrist and carrying the body across a bit. But if the enemy comes to parry and wound you while you disengage do not throw the thrust but hold it a little outside, and in the same tempo that he wants to parry and wound, redisengage your sword under the hilt of his, done aiming at the chest of the enemy so that you strike him in the chest safely, increasing a little with the sword, as you see in the present figure, taking care to disengage and redisengage it in the same tempo, never holding it still so that the enemy does not find it. In the movement he makes to parry, pass to him with your vita on the outside, taking care to place your hand on the hilt of the sword. This pass makes this effect: he takes the chance to wound you and you can wound him how and where you like and please. |

| IL MODO DI FERIRE NEL PETTO<br/>DI SPADA SOLA, QUANDO SONO IN<br/>misura con le spade dal pari. | | IL MODO DI FERIRE NEL PETTO<br/>DI SPADA SOLA, QUANDO SONO IN<br/>misura con le spade dal pari. | ||

| Line 371: | Line 371: | ||

| THE PASS WITH FEINT AT A DISTANCE | | THE PASS WITH FEINT AT A DISTANCE | ||

| − | This is an artificial way of passing at the enemy so that he does not perceive it, and it is of great consideration for the effect it shows, as is seen in the present figure, where one passes with a feint and wounds the enemy. It is done in this way: you need to see in what guard your enemy places himself and how he is accommodated. Go to bind him in guard, directing the point of your sword at his face, and | + | This is an artificial way of passing at the enemy so that he does not perceive it, and it is of great consideration for the effect it shows, as is seen in the present figure, where one passes with a feint and wounds the enemy. It is done in this way: you need to see in what guard your enemy places himself and how he is accommodated. Go to bind him in guard, directing the point of your sword at his face, and when you find yourself almost in measure, if you see that he stays waiting and doesn’t move, throw a thrust at his face strongly as figure number …. shows and if he does not parry strongly you make the effect of figure number …. not having to make other feints, but if he parries you will both be with the swords equal. Immediately return backward outside of measure and put yourself in the same first guard, and when you are almost in measure feint throwing the same thrust at his face. While he goes to parry it, disengage the point of your sword underneath the hilt of the enemy’s sword with your wrist, making sure you keep the enemy sword outside your vita. Then in the same tempo pass, going with your sword over the furnishings of his, accompanying it with the left hand, and immediately put it over the hilt of the enemy sword so that he cannot give you a riverso in the face, so that without doubt you wound him if he does not see your goal. This done, leap outside of measure and replace the sword within that of the enemy, securing yourself in the above way, and beating his sword, return to wound him with two or three resolute and irreparable thrusts. |

| DELLA PASSATA CON FINTA IN DISTANZA. | | DELLA PASSATA CON FINTA IN DISTANZA. | ||

| Line 382: | Line 382: | ||

| The pass with feint over the point of the sword | | The pass with feint over the point of the sword | ||

| − | This is another kind of disengage | + | This is another kind of disengage and feint not commonly used, which produces the effect of the previous two figures. It is done so: one must put oneself in guard with the sword to the left side, with the arm extended and long. Letting the enemy come to bind you in the described way, when he is in measure disengage your sword over the point of his and if you see that he does not parry throw at him strongly and resolutely, as I have said to you, so that you will not make other feints. But if he parries, do not stop with the sword but avoid the guard of the enemy sword and pass in the above way and wound him in the chest, withdrawing yourself then as was said. |

| Della Passata con Finta sopra la punta della spada. | | Della Passata con Finta sopra la punta della spada. | ||

| Line 393: | Line 393: | ||

| THE FEINT TO THE FACE AT A DISTANCE | | THE FEINT TO THE FACE AT A DISTANCE | ||

| − | This feint is no different from the other except that the first has its disengage under the hilt of the sword and this has it over in order to throw at the enemy’s face. This stoccata becomes a feint if he parries | + | This feint is no different from the other except that the first has its disengage under the hilt of the sword and this has it over in order to throw at the enemy’s face. This stoccata becomes a feint if he parries and is resolute if he does not parry. In the rest then, the same guards, distances, and measures are observed, and one carries the vita equally, as is seen in the figure, and immediately returns outside of measure as soon as the thrust is thrown. The most important thing is knowing how to make the feint natural so that it cannot be distinguished from the resolute, which is done in this way. One presents the point (for example) over the outside at his face, and in going with point underneath the hilt of the enemy sword in order to wound him inside, it must be done so that the thrust wounds his face or chest with the disengage. This is what is meant by “natural feint”. But be advised that you never perform a feint if the enemy does not parry resolutely, because you would be in danger of wounding each other and you would end up in danger. |

| DELLA FINTA IN DISTANTIA NEL VISO. | | DELLA FINTA IN DISTANTIA NEL VISO. | ||

| Line 402: | Line 402: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 15 Figure 12.png|200px|center|Figure 12]] | | [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 15 Figure 12.png|200px|center|Figure 12]] | ||

| − | | THE PROPER | + | | THE PROPER METHOD TO GIVE<br/>A THRUST WITH THE SINGLE SWORD<br/>WHILE THE ENEMY THROWS<br/>a cut |

| − | This figure teaches you to avail yourself of the tempo in order to give your enemy a stoccata to the face while he raises the sword, if he can be given a stoccata while his sword is in the air, and before he reaches you. Note how this is done. After having placed yourself in whichever guard you like, go to bind your enemy and | + | This figure teaches you to avail yourself of the tempo in order to give your enemy a stoccata to the face while he raises the sword, if he can be given a stoccata while his sword is in the air, and before he reaches you. Note how this is done. After having placed yourself in whichever guard you like, go to bind your enemy and when you are in measure if the enemy throws a cut toward your head, in the raising of the sword you make use of the tempo, enter forward, and throw the sword at his face so that without doubt you wound him while the enemy sword is in the air, as you see in the figure. But, in throwing turn the inside of your wrist and the right edge of the sword upwards, holding your arm long and high, and make the guard of your sword cover your head so that if the enemy disengages his sword he would find you covered and it will not be possible to offend you. It is necessary, however, to throw this thrust quickly. When it is not made quickly the enemy could parry it and wound you. After you have thrown, quickly withdraw yourself backward outside of measure, securing yourself with your sword against that of the enemy.<br/> |

I did not want to put all the ways of parrying the cuts, which are many, in my first book, but I have placed this alone for you, this appearing to me most useful and commodious for understanding the tempo and making use of it, which is necessary to understand in every occasion. | I did not want to put all the ways of parrying the cuts, which are many, in my first book, but I have placed this alone for you, this appearing to me most useful and commodious for understanding the tempo and making use of it, which is necessary to understand in every occasion. | ||

| IL VERO MODO DI DARA<br/>UNA PUNTA DI SPADA SOLA<br/>MENTRE L’INIMICO TIRA<br/>una Coltellata. | | IL VERO MODO DI DARA<br/>UNA PUNTA DI SPADA SOLA<br/>MENTRE L’INIMICO TIRA<br/>una Coltellata. | ||

| Line 415: | Line 415: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 16 Figure 13.png|200px|center|Figure 13]] | | [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 16 Figure 13.png|200px|center|Figure 13]] | ||

| − | | THE PROPER WAY TO WOUND | + | | THE PROPER WAY TO SAFELY WOUND<br/>with both hands and the single sword |

| − | This figure shows you a | + | This figure shows you a method of safely wounding the enemy which is impossible to parry. It is done in two manners. First one needs to find the occasion to have your sword equal with the enemy’s, having yours outside, then affront your sword toward the enemy’s face which, if not parried strongly, strikes him in the face as is seen in the fourth figure. If he parries well and strongly, increase with your left foot, putting your left hand over your sword, driving strongly with both hands, straightening the point against the enemy’s chest and lowering the hilt of your sword as is seen in the present figure, taking care to do all these things in one tempo.<br/> |

| − | + | Next, accommodated in guard in the aforesaid way but with your sword inside, I want you to disengage the sword in place to wound outside, and in the same tempo that you disengage the sword, place your left hand over your sword and with the strength of both hands beat the enemy sword with yours. That beaten away, immediately pass with your left foot forward as seen in the figure. So that this succeeds well, it is necessary to take care to do all these things in one tempo. That is, disengaging the sword, placing your hand over and beating the enemy sword with yours, and passing forward with the left foot. Not doing these things in one tempo you would not succeed and be in danger, as you would be with some valiant men that know how to disengage the sword quickly and well. Therefore, so that you succeed at this you must do it quickly and suddenly. | |

| IL VERO MODO DI FERIR SICURO<br/>di Spada sola, con tutte due le mani. | | IL VERO MODO DI FERIR SICURO<br/>di Spada sola, con tutte due le mani. | ||

| Line 430: | Line 430: | ||

| THE PROPER WAY<br/>TO PARRY THE CUT<br/>OR RIVERSO, THAT COMES AT THE LEG | | THE PROPER WAY<br/>TO PARRY THE CUT<br/>OR RIVERSO, THAT COMES AT THE LEG | ||

| − | In this lesson, in which we reflect on the mandritto or riverso cut to the leg, I cannot say anything | + | In this lesson, in which we reflect on the mandritto or riverso cut to the leg, I cannot say anything further on parrying and wounding the enemy in one same tempo. Rather, I will say why the enemy ends up offending himself on the point of your sword, except to say that the enemy dropping a dritto or riverso to your leg, it is necessary that he lengthen his step, and his vita, and carry his face forward. While the enemy drops to wound you, you then carry the front leg, lifting it backward, and in the same tempo throw a thrust at his face that is impossible to parry. He wounds himself, neither can you then be wounded. You then (as I have said other times) return backward outside of measure.<br/> |

| − | And since the present lesson is very artificial it is necessary to learn it in order to be able to make use of it in such occasions | + | And since the present lesson is very artificial it is necessary to learn it in order to be able to make use of it in such occasions as the figure clearly demonstrates to you. |

| IL VERO MODO<br/>DI PARARE LA COLTELLATA,<br/>O RIVERSO, CHE VENISSE PER GAMBA. | | IL VERO MODO<br/>DI PARARE LA COLTELLATA,<br/>O RIVERSO, CHE VENISSE PER GAMBA. | ||

| Line 441: | Line 441: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 18 Figure 15.png|200px|center|Figure 15]] | | [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 18 Figure 15.png|200px|center|Figure 15]] | ||

| − | | THE INQUARTATA<br/>OR SLIP OF VITA | + | | THE INQUARTATA<br/>OR SLIP OF THE VITA |

| − | Knowing the inquartata, or slip, is necessary in order to master the body. But this | + | Knowing the inquartata, or slip, is necessary in order to master the body. But this not ordinarily used in the schools, except by the French in order to exercise the body. In truth many are these slips, or inquartate, but I judged in my first book to show only three of them, in my judgement the safest and most beautiful, as appears in the present figure.<br/> |

| − | The first of these is done putting yourself in guard outside of measure with the right foot forward, with the sword long and the arm extended, standing strongly on the right side, holding the point of the sword at the face of the enemy. Let the enemy come to bind you, and | + | The first of these is done putting yourself in guard outside of measure with the right foot forward, with the sword long and the arm extended, standing strongly on the right side, holding the point of the sword at the face of the enemy. Let the enemy come to bind you, and when he is almost in measure disengage the sword in a feint a little wide, and in the tempo the enemy parries, redisengage it, returning it to its first position, running along the edge of his sword with the disengage in a way that as soon as you have disengaged you have wounded the enemy, because if you were to disengage the sword and then wound you would be in danger, since there would be two tempi. Carry the left leg and equally the left shoulder across, turning, and make the effect, giving him (as is seen in the figure) a thrust either in the face or chest without him perceiving the aim, holding the arm stiff, and with the hilt of your sword covering you, far from the sword of the enemy. Keep your eye on his face, taking care not to turn your face with the vita as some do, because you would find yourself in danger and not see your action. After this return immediately back out of measure with your sword over his, securing yourself as above. |

| DELLA INQUARTATA,<br/>OVERO SCANSO DI VITA. | | DELLA INQUARTATA,<br/>OVERO SCANSO DI VITA. | ||

| Line 454: | Line 454: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | The inquartata, or slip of vita | + | | The inquartata, or slip of the vita |

This is no different from the other inquartata from before, except in the way in which it wounds. That is, having regard in going to the edge of the enemy sword, approaching to wound him under the pommel of his sword, lifting the arm with the wrist, as seen in the figure, and after having turned your person, stopping yourself and not passing upon the enemy in order to not come to grips, because you would go into danger, compared to returning outside of measure and securing yourself from that. This inquartata is very difficult to parry, in fact I will say impossible, when it is done with judgement. | This is no different from the other inquartata from before, except in the way in which it wounds. That is, having regard in going to the edge of the enemy sword, approaching to wound him under the pommel of his sword, lifting the arm with the wrist, as seen in the figure, and after having turned your person, stopping yourself and not passing upon the enemy in order to not come to grips, because you would go into danger, compared to returning outside of measure and securing yourself from that. This inquartata is very difficult to parry, in fact I will say impossible, when it is done with judgement. | ||

| Line 465: | Line 465: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | THE THIRD INQUARTATA,<br/>or slip of vita | + | | THE THIRD INQUARTATA,<br/>or slip of the vita |

| − | This third inquartata is the most beautiful and | + | This third inquartata is the most beautiful and safest of all, which is done in this way. Placing yourself in guard, as in the other two, holding the sword to the right side with the arm extended and firm, as the enemy comes to bind you with his sword over yours and you are in measure, disengage the sword with the turn of your wrist. If he does not parry, strike him in the face and make the effect of the figure, nor should you do more. But if he parries, you find yourself with the swords equal. Affront his sword strongly with yours so that he affronts, and as he affronts disengage, going with the disengage under the hilt of his sword, turning your body as above, wound him in the chest, which he will not perceive, and do the effect of the present figure. Then return outside of measure, securing yourself as in the other lessons. |

| DELLA TERZA INQUARTATA,<br/>o Scanso di vita. | | DELLA TERZA INQUARTATA,<br/>o Scanso di vita. | ||

| Line 478: | Line 478: | ||

| An artificial way to strike in the chest, affronting the swords | | An artificial way to strike in the chest, affronting the swords | ||

| − | In the previous lessons I demonstrated the | + | In the previous lessons I demonstrated the method of the inquartate, that is, how one would affront the swords outside in order to come to wound the enemy inside. Now I will briefly say how one would carry the swords inside and wound outside. As you meet with the enemy, affront strongly with the edge of your sword, holding the point at his face, with the forte over the enemy sword. If he is weaker than you, give him a stoccata, either in the face or chest that he cannot parry. If he is stronger than you, feeling how much your sword is affronted disengage the sword under the hilt of his so that his falls downward, and he equally takes a thrust from which there is no defense. In the same tempo pass without any danger and put your left hand on his hilt, wounding him with three or four thrusts that cannot be avoided. Then return outside of measure, securing yourself as above. |

| D’un modo artificioso di dar nel petto affrontando le spade. | | D’un modo artificioso di dar nel petto affrontando le spade. | ||

| Line 489: | Line 489: | ||

| The way of playing single sword against single sword with resolute thrusts | | The way of playing single sword against single sword with resolute thrusts | ||

| − | Many are those in the schools that when they assail the enemy come resolutely throwing thrusts, imbroccate, and cuts, nor do they give any tempo, throwing always with fury and very great impetus. These things ordinarily mess up and | + | Many are those in the schools that when they assail the enemy come resolutely throwing thrusts, imbroccate, and cuts, nor do they give any tempo, throwing always with fury and very great impetus. These things ordinarily mess up and disorder every beautiful player and fencer. Accordingly, in such occasions it is necessary to know how to defend oneself. It is necessary that you place yourself to the guard of the enemy sword with yours ready to defend, outside the measure, in a that is pace restrained rather than long, and in the tempo that he throws a thrust, imbroccata, stoccata, or other similar blow, beat the enemy sword with the forte of yours and immediately lengthen your pace, and throwing him a thrust wound him in the chest or face and quickly return backward with the lead foot to where you were before, resting your sword on his in order to secure yourself from it, in a way that he cannot wound if he does not disengage. Turning your wrist inside, return to beat the enemy sword with the forte of yours, lengthening your pace throw him a thrust and wound him and quickly return backward with the foot as above, likewise securing yourself from his sword with yours. If he returns anew to redisengage, always return and do the same.<br/> |

| − | This lesson is more useful than beautiful | + | This lesson is more useful than beautiful and contains two tempi which you can make before the enemy has time to make one of them. The first of which is the parry, the other is the wound. Which, as has been observed, you have understood. |

| Del modo di giucar di Spada sola contro Spada sola, di punte risolute. | | Del modo di giucar di Spada sola contro Spada sola, di punte risolute. | ||

| Line 502: | Line 502: | ||

| PARRYING STOCCATE<br/>THAT COME AT THE CHEST WITH THE SINGLE SWORD | | PARRYING STOCCATE<br/>THAT COME AT THE CHEST WITH THE SINGLE SWORD | ||

| − | + | Seen in this figure is the safe method of parrying thrusts that come at your chest, wounding the chest. It is done in different ways because some may pass at a distance, others stay in measure, and others inside the measure, but one who has understanding of tempo and knows how to parry well as my figure demonstrates will parry all the methods. From which you note that, being with your enemy with the swords equal and he passes in order to wound you in the chest, by necessity in that same tempo follow his sword with yours, lowering, however, the point of yours and raising your wrist, parrying with the same and passing with your left foot toward his right side, taking yourself away from his sword wound him in the chest, holding your left hand over the hilt of his sword. Then, the stoccata given, disengage the sword in the way described above, returning backward outside of measure. | |

| DEL PARAR LE STOCCATE<br/>CHE VENGONO NEL PETTO DI SPADA SOLA. | | DEL PARAR LE STOCCATE<br/>CHE VENGONO NEL PETTO DI SPADA SOLA. | ||

| Line 513: | Line 513: | ||

| THE THRUST<br/>IN THE FACE<br/>TURNING YOUR WRIST | | THE THRUST<br/>IN THE FACE<br/>TURNING YOUR WRIST | ||

| − | With this figure you are taught a very beautiful | + | With this figure you are taught a very beautiful method of wounding your enemy’s face, and it consists entirely of seizing the occasion of being with the swords equal, causing your enemy to be in the motion of parrying by giving him suspicion that you want to disengage the sword. In the same tempo, turn your wrist, put your left hand on the guard of his sword, and increase with the foot in one tempo so that you strike him in the face, as you see. Doing it properly it cannot be parried. Having given that, increase with your left hand over the hilt of the enemy sword and redisengaging the sword you can give him two or three stoccate where you like. Then return backward outside of measure, always holding your sword over theirs, as above. |

| DELLA PUNTA<br/>NEL VISO<br/>VOLTANDO IL NODO DELLA MANO. | | DELLA PUNTA<br/>NEL VISO<br/>VOLTANDO IL NODO DELLA MANO. | ||

| Line 523: | Line 523: | ||

| [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 21 Figure 18.png|200px|center|Figure 18]]<br/>[[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 22 Figure 19.png|200px|center|Figure 19]] | | [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 21 Figure 18.png|200px|center|Figure 18]]<br/>[[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 22 Figure 19.png|200px|center|Figure 19]] | ||

| THE COUNTERDISENGAGE AT A DISTANCE | | THE COUNTERDISENGAGE AT A DISTANCE | ||

| − | This | + | This is one and the same counterdisengage at a distance against one who has their left foot forward and wants to pass by inquartata. I wanted to demonstrate to you with this figure the postures and wound so that it is possible to comprehend it well for the sake of necessity (when one is coming to bind you with their left foot forward). Stand in guard as you see in this figure, giving occasion to your enemy to throw at your chest. If he is a valiant man he will pass with his foot quickly and strongly turn his wrist in the manner of the inquartata in order to defend himself from your sword. In the same tempo that he passes, redisengage the sword under the hilt, lowering your vita as you see in the present figure so that you wound him in the face before he wounds you. In fact, while he carries his foot forward in order to pass it is not possible to parry. At times it is necessary to make the effect of this figure. Exercise well these two figures placed before. |

| DELLA CONTRACAVATIONE IN DISTANTIA. | | DELLA CONTRACAVATIONE IN DISTANTIA. | ||

| Line 532: | Line 532: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 23 Figure 20.png|200px|center|Figure 20]] | | [[File:Scola, overo teatro (Giganti) 23 Figure 20.png|200px|center|Figure 20]] | ||

| − | | | + | | METHOD OF PLAYING WITH THE SINGLE SWORD,<br/>while the enemy has sword and dagger |