The fourth book begins, in which is treated the selection of armaments. Chapter 1.

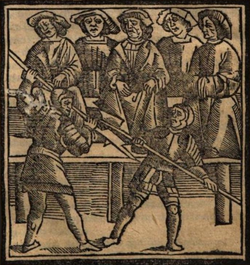

In the first chapter of the present book, it is written whether the weapons of those who are challenged by pledge of battle should follow the covenant of engagement signed between them (such as lance, sword, dagger, iron-shod mace, or whichever other arms, according to the decision that they should fight). Or it is lawful for each of them to carry, apart from the appointed weapons, other small arms such as knives and stilettos, with which they might prevail if necessary despite not being named or covenanted between them. And similarly, in battle on foot one may bring long weapons and also short weapons (such as bodkins and spikes and similar instruments of battle).

However, some are wont to measure the weapons, and others do not care if they be equal. But when the battle is made to the death, every manner of weapon may be carried even if it be not specified in the covenant. And in the case that the challenged had not made a choice of weapons, it will be left to each of the two to carry the weapons that they want for the battle. Because Emperor Federico described in the constitution of the Kingdom of Sicily that the weapons be equal. However, by common custom whichever of them wishes may use whichever weapon seems best (not contravening the pact and covenant between them).

And as it is narrated about one of our Neapolitans who, lightly armed, made to carry into the list a certain quantity of smooth, round, and small rocks to cast by hand, which so injured his enemy and in this manner offended him that after the first throws he was overthrown and defeated, just as did the king David to the giant Goliath, who he killed with stones.

|

[48r] Incipit Liber quartus. De Armis. 1

[A]Rma quiden pugnantium in duello erunt sedum federa & conventiones pugilim quippe cum armis conventis pugnabunt quia si equites pugnare [48v]

|

[119] Incomincia il quarto libro, nel quale se tracta dela electione dele arme. Capitulo I.

NEl primo capitulo del presente libro se descrive, si como l'arme deli disfidati per guagio de battaglia debbeno essere secondo la conventione deli pacti fermati tra loro se con lanze, spate, daghe, mazze ferrate[2] o con quale se voglia altra armatura, secondo la deliberatione debbeno combattere. Pero e licito a ciascuno de loro portare oltra quelle arme deputate altre piccole como sono li cortelli, pugnali, quatrelli conliquali se possano prevalere nel necessario, quantunche non fosseno nominati tra loro capituli. Similmente in battaglia pedestre se po portare arme longhe, & piccole como sono brocchette, & ponzoni, & de simile natura de instrumenti de battaglia pero alcuni sogliono mesurare l'arme, alcuni non curano che siano mesurate; ma quando la battaglia fosse a tutta oltranza se potria portare ogni generatione de arme benche non fosseno specificati neli pacti; & in caso chel rechiesto non havesse facto electione de l'arme fara ne l'arbitrio de tutti doi l'arme che volesseno portare nela battaglia. Perche descrive Federico Imperatore nela constitutione del regno de Sicilia che l'arme siano equale; pero de commune consuetudine quale se voglia de loro potra usare quel'arme [120] che meglio li parera non contravenendo ali pacti;

|

[19v] ¶ Comiença el quarto Libro en el qual se trata de la elicion de las armas Capitulo Primero.

EEn el primer capitulo del presente Libro se escrive si las armas de los desafiados por gajo de batalla deven ser segun la convincion y partido firmado entre ellos si con lança y espada: y daga: y maça herrado: o qual quiera otra armadura segun la deliberacion deven combatir o si es licito a cada uno de ellos traer otras armas {vitra} de aquellas que son señaladas otras chicas como son cuchillos: y puñales quadrillos con los quales se pueda ayudar en la necessidad aunque no fuessen nombrados ni capitulados entre ellos: y semejantemente en batalla a pie si se puede traer armas luengas y chicas como son broquetes punçones: y de semejante natura de ustrumento de batalla por que algunos suelen medir las armas: y algunos no curan que sean medidas mas quando la Batalla fuesse hecha a todo trance podria traer todo genero o manera de armas con tal que no fuessen defendidas por convenencia entre ellas: y en caso que el reutado no oviesse hecho la elecion de las armas sera en el alvedrio de todos dos llevar las Armas que ellos quisieren ala batalla / y porque escrive Federico Emperador en la constitucion del Reyno de Cecilia que las Armas sean yguales Pero comun constituciones que qualquiera de ellos [20r] pueda usar aquellas armas que mejor le pareceran no viendo en contra del patio /

|

[48r] The Ffowerthe Booke wherin is declared the Election of the weapon and Armes. Capitolo Primero

In the ffirste chapter of this ffowrth booke

is mencioned what weapons are allowed in combatt wch are

accordinge to the agrement betwext the parties as lannces

swordes daggers maces of Iron or such like It is lawfull

for them to weare besides thease somme others of small

importannce, as knives and daggers wherof sometimes they maye

receave somme commoditie, though in the agrement no mencion

be made of them at all. Lykewise in fight on foote a man maye

weare a longe or shorte weapon at his plessr, as Tucke or shorte

swordes, and such like instrumente of warre. Some are of a

opinion to have all weapons measured, somme others make therof

none accompte, but when combat is vppon lyfe and death a man

maye vse whatsoever weapon him liste, albeit it be not specified

wthin the agremente. And in case the defender hath not chosen

the weapons, then shall it be free for either of them to make

their owne choise. Federick [sic] the Emperor in his constitucion

of the kingdome of Sicilia saith that the weapons wolde be eequall,

wheruppon it semeth the custome is, that every man

may choose his own weapon, so as the same doe not repugne

to the agremente. [48v] Then shall he proceede accordinge to order before agreed vppon w[i]thout

further advanntage, for the proverb saith Per amore si fanno gran tratti, guardati de l’auantagio che danno non habbi. ~

|

|

|

De armis concessis secundum ius longobardum. et quid de consuetudine. 2

[I]n duello secundum iura longobarda concessa sunt scuta & fustes. [49r]

|

& perche se narra de uno nostro regnicola il quale armato ligiero se fece conducere nel steccato certa quantita de pietre si lice tonde, & piccole apte a menare a braccio con le quale percosse il suo nimico, in modo & in tal manera lo offese che dapo lo assalto lo vinse, & superollo; si como fece Re David al gigante Golia ilquale occise con pietre. De un'altro Cavaliero anchora se narra che porto una quantita de giavarine dentro del steccato le quale in diversi lochi le fixe in terra; & con quelle insultando il suo nimico quando tirandole, & quando fugendole sempre con nove offese se adoperava tale che a la fine rimase vincitore. Et per questo se denota chel nimico se debbe con ogni subtile industria, & ingegno superare cercando quallo che lui deliberasse contra de te adoperare, tu contra epso con ogni avantagio se sforza adoperarlo per salvatione dela vita desiderata a ogni generatione d'animali. Pero quando se combattesse per amore, per voto, o per monstrare la virtu se debbe seguire secondo la conventione deli pacti senza alcuno avantagio dele parte; perche dice l'antiquo proverbio, per amore se fanno de gran tracti; guardate del avantagio che danno non habi. [121] & con armecto, schineri; salvo se la battaglia fosse causata par delicto de infidelitate; perche alhora se deveria combattere con arme militare. Et quando la battaglia se fa con bastoni debbeno essere equali; & in caso che nel combattere se rompesseno se debbeno deli altri provedere. Pero quando combattesseno con arme militare rompendose non debbeno prendere l'altri; perche se imputano a la sua mala fortuna; & in caso che uno cascasse non debbe essere sublevato secondo la consuetudine de li oltramontani, & Italici cascando l'arme, overo rompendose in battaglia de tutta oltranza non potranno altre arme recercare, per respecto che pare per divino judicio intravenga; attale che la battaglia se fornisca; reservato se facesseno altri pacti, neli quali havesseno deliberati de rompere tante lanze, overo de correre tanti colpi toccati con lanze, o con haste quale rompendose potranno l'altre repigliare; ma per evitare il periculo essendo convenuti de combattere con spate sara licito portarne due, o piu per sua volunta.

|

y convencion que entre ellos esta porque se cuenta de un nuestro por nombre nicola: el qual armado ligero se hizo traer en el estacada cierta cantidad de piedras lisas y redondas aparejadas para tirar con la mano con las quales hirio a su enemigo de modo y manera lo ofendio que luego a los primeros tiros lo derribo y vencio assi como hizo el rey David al gigante Golias el qual mato con piedras: de otro cavallero tanbien se dize que truxo una cantidad de cuchillos dentro del estacada y en diversos cabos los hinco en tierra / y con aquellas salteo a su enemigo quando le tirava una y quando se retraya: y con nuevas ofensas se defendia de tal manera que al fin quedo vencedor: y por aquesto se declara que el enemigo se defendia de tal manera que al fin quedo vencedor: y por aquesto se declara que el enemigo se deve con toda sotil industria y ingenio buscar venciendo aquello que el delibra hazer contra ti: y tu contra el: con toda ventaja esfuerça a obrarlo por salvacion de la vida desseada a toda generacion de animales pero quando se combatiesse por amor o por boto o por mostrar la virtud se deve seguir segun la convincion del partido o concierto sin alguna ventaja de las partes porque dize el antiguo proberbio por amor se hazen grandes tratos: y engaños guardate de tal ventaja que daño no recibieras.

|

Of Armes accordinge to the Lawe of Lombardie. ~ . ~ . Ca[pitolo] 2.

Lett vs nowe consider accordinge to the Lawe

of the emperors of Lombardie, the first inventors

of Combatte in Italie whether a man maye fighte w[i]th sheildes

and staves, the battle not beinge for infidelitie, for then a man

ought to use the weapon of a Soldier. And when as the combat

is tried w[i]th staves, the same ought to be equall and yf perchannce

they breake in fighte, then ought others to be provided

But yf in fight w[i]th weapons martiall they happen to break

then shall none other be provided, because the breakinge is imputed

to his evill fortune, or yf happelie one of the fighters doe

fall, he ought not be helped up, accordinge to the custome

used beyonde the mountaines. The Italians beinge in fighte

for life and deathe, and happeninge to lose his weapon by breakinge

or otherwist, maye not be permitted to take an other weapon

in hande, because the hap hereof semeth to proceede of the

devine Judgemente therby to ende the combat (unles by former

agremente) it be ordered to the contrarie. As yf they agreed

to breake a certeine nomber of lannces, or to runne a certeine

nomber of courses, or yf the fight be w[i]th swordes, and the

parties agreed to fight w[i]th two thre or fowre accordinge to

the Agremente. ~ . ~ . ~ . ~ . ~ . ~ . ~ .

|

Chapter 3: When two knights decide to fight with swords, without other military armaments

It brings to mind two knights who, having pledged for battle, obtained a field from a prince. They had decided an agreement to fight unarmed apart from swords and without any body armor, and with this, each one would show their mettle in defending their cause/right, and in order to defend their lives they would put themselves in a state such that each had the semblance of a raving dragon. Seeing this, on the appointed day [the prince] did not want the battle to be made, seeing that it was more suitable for vile butchers than for valorous knights, and for this work and provision[3] the prince was highly praised. And in a similar case for the worthy prince, he would not permit such a battle except with military weapons, fighting at least partially armored (and partially unarmored).

Combat without all the armaments necessary for military exercise is not pertinent to good knights, and likewise good knights in the field are wont on occasion, in similar endeavors, to exercise their valorous persons in order to show their strength, and to defend their justice. And it is described in Lombard law that battle between knights should not be made with sticks, nor with stones$mdash;unless there be contrary testimonies, then in that hour they should fight with sticks and shields in order to prove which of them had spoken the truth.

|

Si duo se diffidant ad pugnam non cum armis militaribus an sint admittendi 3

[C]Ontingit q[ui] duo milites nobiles in armis versati se ad pugnam diffidaverunt cu[m] ensibus pugnaturi eq[ui]tes ac inermes cum vero invenissent principe[m] qui campum dederat securum & explicassent co[n]troversiam & [qui?] inermes solis ensibus belligerare convenerant princeps co[n]spiciens [qui] talis[?] pugnandi modus potius lenonibus [q??] militibus decebat mutato decreto ca[?]pi securitate[m] abolevit · ac jussit[?] eos nequaq[uam] pugnaturos more lenonu[m?] cum nobiles existerent huiusmodi[~?] probissimi principis decretum fuit in militu[m] ordine probatum · & pro r[ati]o[n]e[? cappelli 396] observandum erit cu[m] iterato [?] cas[cum? con, cun, com] eveniret q[uia? cappelli 366] exe[m]plis optimi p[ri]ncipis e[st? cappelli 177] iudicandu[m] q[???] seque[n]da sunt ff.ad tre.l.q[ui] iulian[cum?] .ad si. sicut exe[m]pla e[m?]porum .xvii.q.vl. q[uo]cunq[ue] [49v] & exempla doctoru[m] .l.i.ff. de manu .vin. & dicit[?] lombarda .q[uem? cappelli 367 very unsure] pugna debet fieri cu[m] armis militaribus .ut in lombar. ubi dicit qui[?] no[n] debet fieri pugna fuste vel lapide sed armis militaribus nisi in testibus pugna[n]tibus [Cf.????] ipsi pugna[n]t fustibus &

|

Quando li cavalieri deliberasseno combattere con spate senza arme militare. Capitulo III.

ACcade fare mentione de doi cavalieri quali havendone guagio de battaglia obtenere da un principe il campo ilquale vedendo che haveano deliberati per pacto combattere desarmati solo con spate senza altre arme corporale, & con quelle ogn'uno de loro monstrare il suo ardire defensare la sua ragione, & defendere la vita se possono in modo che ognun de loro parea un drago rabiato, & [122] nela giornata non volse che la battaglia se facesse vedendo che era piu conveniente a vilissimi beccarini, che a valorosi cavalieri; & sumamente fo laudata la sententia de tal principe; & in simili casi per degno principe questo saria da fare de non permettere tal battaglia; reservato quando con arme militare in parte armati, & in parti desarmati combattesseno non saria apertenente a boni cavalieri combattere senza tutte le arme necessarie alo exercitio militare, & como boni cavalieri sogliono inel campo, & in simile imprese exercitare loro valorose persone per cagione de demonstrare loro forze, & defensare loro iustitia; & descrivese nela longobarda lege che la battaglia fra cavalieri non se devera fare con bastoni, ne con pietre; reservato quando fosseno li testimonii contrarii; perche alhora deveriano combattere con bastoni, & scuti per provare chi de loro havesse dicta la verita;

|

¶ Capitulo .ii. De las armas segun la ley Lombarda.

AHora sera de ver segun la ley de los emperadores Lombarda qua;es fueron los inventores en ytalia para combatir por gajo de batalla si se deve combatir con escudo y baston y con almete equinado salvo si la Batalla fuesse causada por delito de infidelidad porque a la ora se devria combatir con arma militar y quando la batallase haze con baston deven ser yguales en caso que combatiendo se rompiessen deven les de proveer de otros pero quando combatiessen con arma militar si se rompiessen no deven tomar otras: por que se imputa a su mala fortuna y si por caso el uno cantanos / y los ytalianos caendose les armas: o rompiendose les en la batalla de oltrance no pueden otras armas buscar por respeto que parece ser por divino juyzio portal que la batalla se acaba reservando si hiziesse en otro concierto en el qual oviesse deliberado de romper tantas lanças o de correr tantos golpes tocados con lanças con astas los quales siendo concertados rompiendose podran tomar otras mas por evitar el peligro porque siendo concertados para combatir con espadas sera licito traer dos o mas a su voluntad. [20v] reservando quando fuessen los testigos contrarios porque a la ora deverian combatir con bastones y escudos por provar qual de ellos oviesse dicho la verdad

|

[49r] When the fighters doe Appointe to fighte with swordes disarmed. ~ . ~ . ~ . Capitolo 3.

It semethe not impertinent to make mention that whereas two gentlemen havinge obteyned place for combatt of somme prince doe determine to fighte clerelye disarmed with swordes onlye and therewith to showe the nobylitie of their mindes in the defence of reason and lives. And beinge thus prepared like dragons appearinge at day appointed the prince forbiddeth them to fighte, supposinge this manner of doinge more meete for butchers and suche lyke, men of base condition then for noble and couragious gentlemen. The opinion of the prince was greatlie commended in not sufferinge them to proceede in fight accordinge to their determination unles theye doe appear in somme parte armed and furnished with weapon meete for the exercise of a soldier, for it is not the parte of a gentleman to be unfurnished all kinde of armes meete for the exercyse of the warre, which all good soldiers were wonte ever to have readie of purpose to practize in feilde their valiannt bodies in feates of armes and therby to declare their force and defend their righte. In the law of Lombardie it is declared that gentry ought not to enter into combatt with staves nor stones, riservato quando fussino gli testimonij contrarij. For then they ought to fight with staves and sheildes in the triall of truthe.

|

It happened that two Ultramontane knights came into Italy to fight unarmed apart from swords and knives, and having obtained a free field, they gave notice to a judge, to whom many knights appealed that he not permit this cruelty that would get them killed, and the field was revoked by the prince. And the judge made harmony between them with excusatory words that should be said by the challenged party. And so they returned to their land where, after they arrived, they had a new question between them, whether the words of the challenged could be unsaid or not, and because of this they went on another journey for another battle.

And for this reason, at the end of the present work I will write at length about the manner of unsaying, which should be made one way by the challenged and one way by the challenger, which intervenes in similar battles that are made person-to-person.

|

|

& accade che venendo in Italia doi Cavalieri oltramontani per combattere desarmati solo con spate, & pugnali havendo obtenuto il campo libero pervenendo in notitia del iudice al quale molti cavalieri supplicaro che non permettesse si crudelmente farli amazare fo per il principe revocato il campo; & facta tra loro concordia per il iudice de alcune parole exusatorie se devesseno dire per il rechiesto se retornorno nel loro paese dove essendo pervenuti hebbeno fra loro novo rebacto se le parole dicte dal rechiesto erano desdicta si, o no; perche seguiro nova impresa in un'altra battaglia; & per questo al fine dela presente opera descriveremo ad pleno dela desdicta como, & quale se debbe fare si per il rechiesto, & si anchora per il rechieditore che intraveneno a simile battaglia che se fanno da persona a persona.

|

acaescio que viniendo en ytalia dos cavalleros Oltramontanos para combatis desarmados: mas solamente con espadas y puñales: y haviendo tenido el campo libre veniendo a noticia del juez al qual muchos cavallero le suplicaron que no permitiesse assi cruelmente haz ellos matar fue por el Principe revocado el campo: y hecho entre ellos concordia por el Juez de algunas palabras escusatorias que se deviessen dezir por el reutado. E assi se bolvieron en su tierra donde despues venidos ovieron entre ellos nueva quistion diziendo si las palabras dichas por el reutado si era desdezido o no por lo qual figuieron nueva empressa en una otra batalla y por aquesto al fin de la presente obra escrivire mos cumplidamente de la manera del desdezir lo qual se deve hazer assi por e reutado como por el reutador y que intreviene en semejante batalla que se haze de persona a persona.

|

There happened to come into Italie two gentlemen stranngers of purpose to fight with swordes and daggers disarmed who havinge obteyned libertie of feilde elected their judge to whome repaired diuers other gentry prayenge him nott to permitt so great a crueltie that the one sholde in this sorte sleae the other. At the firste the prince revoked the feilde and caused concored betwext the gent to be made by the Judge with certein wordes of excuse on the parte of the defender, which done they retorned into their contrie, where beinge arrived, they fall againe into a newe quarrel, wheter the excuse made before were a yeldinge or unsayeinge or not. Heereuppon ensueth a newe question, [49v] if the saide wordes were a deniall or not? Wheruppon a combat maye be granted. But in the case of deniall we shall in the ende of this worke discourse at large, what and howe the defenders deniall shal be understoode, and in what sort the challenger shall enter into like personall battle. ~. ~. ~. ~. ~. ~. ~ .

|