|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli"

| Line 995: | Line 995: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Capo Ferro | + | | [[File:Capo Ferro 01.png|400x400px|center]] |

| '''WAY OF LAYING THE HAND ON THE SWORD.''' | | '''WAY OF LAYING THE HAND ON THE SWORD.''' | ||

Because in all the lands there are not the same customs, and often times enmities are expressed with little sincerity, in order to be provided against all occasions, it will not, perhaps, be out of place to teach the way of laying the hand on the sword, before we come to deal with its handling. If by chance you will have your right leg forward when laying your hand on the sword, as is shown in this figure, you will draw back the said leg, extending your right arm at the same time into high first; and if perchance you find yourself with the left leg forward, as the other figure shows, it will not happen if you do not draw your sword in the aforesaid manner, without changing of your pace; and if you would like to avail yourself of the sword and cape, or sword and dagger, as well as the single sword, the true way is, that first you will take a step with your right foot forward in order to present yourself in fourth, or alternately being near the adversary you will draw your left foot back presenting yourself as above, and then at your ease you will be able to wind your cape, or extend your hand to your dagger with more safety, being that the point of your sword will make it such that your adversary remains distant wile you accommodate yourself to your weapons; and this is as much as it occurs to me to say about this particular topic. | Because in all the lands there are not the same customs, and often times enmities are expressed with little sincerity, in order to be provided against all occasions, it will not, perhaps, be out of place to teach the way of laying the hand on the sword, before we come to deal with its handling. If by chance you will have your right leg forward when laying your hand on the sword, as is shown in this figure, you will draw back the said leg, extending your right arm at the same time into high first; and if perchance you find yourself with the left leg forward, as the other figure shows, it will not happen if you do not draw your sword in the aforesaid manner, without changing of your pace; and if you would like to avail yourself of the sword and cape, or sword and dagger, as well as the single sword, the true way is, that first you will take a step with your right foot forward in order to present yourself in fourth, or alternately being near the adversary you will draw your left foot back presenting yourself as above, and then at your ease you will be able to wind your cape, or extend your hand to your dagger with more safety, being that the point of your sword will make it such that your adversary remains distant wile you accommodate yourself to your weapons; and this is as much as it occurs to me to say about this particular topic. | ||

| Line 1,002: | Line 1,002: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Capo Ferro | + | | [[File:Capo Ferro 02.png|400x400px|center]] |

| rowspan=3 | '''OF THE GUARDS.''' | | rowspan=3 | '''OF THE GUARDS.''' | ||

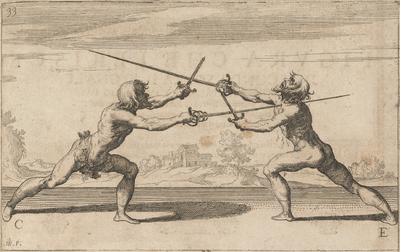

As one cannot make some composition of beautiful and judicious writings without employing the letters of the alphabet, so does it occur in this our art of fencing, that without the following guards, and some voids and slips of the body which come to be the foundation of this exercise, one could not in any way show this use of ours; therefore the following six figures are designated alphabetically. “A” demonstrates the first to you, and the second is presented to you as “B”, and the third as “C”. The fourth is named as “D”, the fifth as “E”, and the sixth as “F”. | As one cannot make some composition of beautiful and judicious writings without employing the letters of the alphabet, so does it occur in this our art of fencing, that without the following guards, and some voids and slips of the body which come to be the foundation of this exercise, one could not in any way show this use of ours; therefore the following six figures are designated alphabetically. “A” demonstrates the first to you, and the second is presented to you as “B”, and the third as “C”. The fourth is named as “D”, the fifth as “E”, and the sixth as “F”. | ||

| Line 1,009: | Line 1,009: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Capo Ferro | + | | [[File:Capo Ferro 03.png|400x400px|center]] |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Capo Ferro | + | | [[File:Capo Ferro 04.png|400x400px|center]] |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Capo Ferro | + | | [[File:Capo Ferro 05.png|400x400px|center]] |

| '''FIGURE EXPLAINED BY WAY OF THE ALPHABET.''' | | '''FIGURE EXPLAINED BY WAY OF THE ALPHABET.''' | ||

Figure that demonstrates resting in guard, as is shown in our art, and the incredible increase of the long blow, in regard of the members which are all moved to strike. | Figure that demonstrates resting in guard, as is shown in our art, and the incredible increase of the long blow, in regard of the members which are all moved to strike. | ||

| Line 1,048: | Line 1,048: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Capo Ferro | + | | [[File:Capo Ferro 06.png|400x400px|center]] |

| '''WAY OF GAINING THE SWORD ON THE INSIDE IN THE STRAIGHT LINE AND STRIKING ACCORDING TO THE POINT THAT THE ENEMY WILL GIVE.''' | | '''WAY OF GAINING THE SWORD ON THE INSIDE IN THE STRAIGHT LINE AND STRIKING ACCORDING TO THE POINT THAT THE ENEMY WILL GIVE.''' | ||

There are two causes (it seems to me) for which it is necessary to stringer the adversary: the first is to stringer the sword in order to seek the measure and the tempo; the other is to stringer the body of the adversary in order to seek only the measure; which excellent stringerings are considered in the straight line; and because there are two causes of stringering there must also be two occasions: the first occasion of stringering the sword, in order to seek the measure and tempo, is when the said adversary lies in an oblique line, because the adversary lying with the sword in fourth which is aimed on an oblique line at your left side, you will lie with the sword on the outside, and disengage with an increase of pace in order to stringer it on the inside with the said straight line, as the figures show you; from this he can cause you a good deal of difficulty, seeing as how only the said straight line suffices to stringer the sword, the adversary's sword lying in an oblique line; the second occasion, that of stringering the body in order to find only the measure, is when the adversary lies in the straight line, or with his body uncovered, then without stringering the sword in order to seek the tempo, it will suffice to only stringer the body with the straight line in order to find the measure, and then to strike according to the point; although the use of the art requires that one stringer the sword in all the lines without some utility. Striking according to the point, one must understand that every time that the point of the opposing sword be in your line then you will be able to strike in the straight line where the height of the point of the enemy's sword will give its direction, taking a palmo from the point of your enemy's sword, however, with the forte of your sword, and you will strike safely, taking heed that if it is as high as the middle of your head you will strike him in the face, and were it to the middle of your body you will be able to strike him in the face and in the breast; this is called "to strike according to the point that the enemy's sword will give"; moreover in this way you will be able to safely disengage the sword from all sides in order to attack; however, when disengaging you will carry the forte of your sword in primo tempo to the point of the adversary's sword, and do not do as some masters do, who disengage, and do so in order to strike in primo tempo, arriving with the point of their sword on the forte of the enemy's sword, not perceiving that they give the point to the enemy, and most of the time they are offended, as is seen in our figures. | There are two causes (it seems to me) for which it is necessary to stringer the adversary: the first is to stringer the sword in order to seek the measure and the tempo; the other is to stringer the body of the adversary in order to seek only the measure; which excellent stringerings are considered in the straight line; and because there are two causes of stringering there must also be two occasions: the first occasion of stringering the sword, in order to seek the measure and tempo, is when the said adversary lies in an oblique line, because the adversary lying with the sword in fourth which is aimed on an oblique line at your left side, you will lie with the sword on the outside, and disengage with an increase of pace in order to stringer it on the inside with the said straight line, as the figures show you; from this he can cause you a good deal of difficulty, seeing as how only the said straight line suffices to stringer the sword, the adversary's sword lying in an oblique line; the second occasion, that of stringering the body in order to find only the measure, is when the adversary lies in the straight line, or with his body uncovered, then without stringering the sword in order to seek the tempo, it will suffice to only stringer the body with the straight line in order to find the measure, and then to strike according to the point; although the use of the art requires that one stringer the sword in all the lines without some utility. Striking according to the point, one must understand that every time that the point of the opposing sword be in your line then you will be able to strike in the straight line where the height of the point of the enemy's sword will give its direction, taking a palmo from the point of your enemy's sword, however, with the forte of your sword, and you will strike safely, taking heed that if it is as high as the middle of your head you will strike him in the face, and were it to the middle of your body you will be able to strike him in the face and in the breast; this is called "to strike according to the point that the enemy's sword will give"; moreover in this way you will be able to safely disengage the sword from all sides in order to attack; however, when disengaging you will carry the forte of your sword in primo tempo to the point of the adversary's sword, and do not do as some masters do, who disengage, and do so in order to strike in primo tempo, arriving with the point of their sword on the forte of the enemy's sword, not perceiving that they give the point to the enemy, and most of the time they are offended, as is seen in our figures. | ||

| Line 1,055: | Line 1,055: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Capo Ferro | + | | [[File:Capo Ferro 07.png|400x400px|center]] |

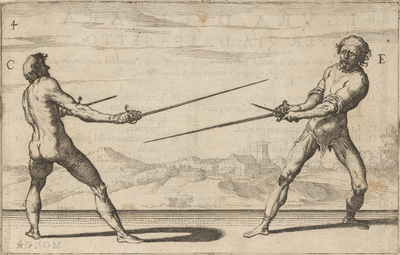

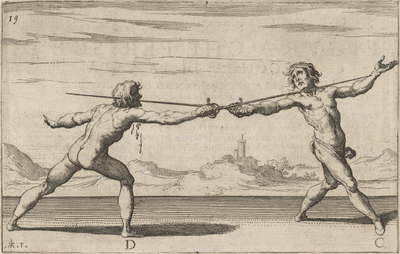

| '''The present and subsequent figures demonstrate diverse manners of wounding on the outside, always presupposing a stringering on the inside and a disengage by the adversary in a thrust for the attack.''' | | '''The present and subsequent figures demonstrate diverse manners of wounding on the outside, always presupposing a stringering on the inside and a disengage by the adversary in a thrust for the attack.''' | ||

For an explanation of the following figure I say that D being narrow to the inside of the figure marked C, the same C disengages to attack with a thrust to the chest of D. D then attacks with a thrust to the left eye with a firm foot or an increase of a step as seen in the figure. But still I say that if C had been clever, when disengaging he would have disengaged by way of a feint, with his body held back, and D, in approaching, would have been confident in attacking C. Then C would have parried the enemy's sword with the false or the true edge to the outside, giving him a mandritto to the face or an imbroccata to the chest and then he would return to a low fourth. | For an explanation of the following figure I say that D being narrow to the inside of the figure marked C, the same C disengages to attack with a thrust to the chest of D. D then attacks with a thrust to the left eye with a firm foot or an increase of a step as seen in the figure. But still I say that if C had been clever, when disengaging he would have disengaged by way of a feint, with his body held back, and D, in approaching, would have been confident in attacking C. Then C would have parried the enemy's sword with the false or the true edge to the outside, giving him a mandritto to the face or an imbroccata to the chest and then he would return to a low fourth. | ||

| Line 1,062: | Line 1,062: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Capo Ferro | + | | [[File:Capo Ferro 08.png|400x400px|center]] |

| '''Figures that demonstrate how much measure is lost by attacking the leg.''' | | '''Figures that demonstrate how much measure is lost by attacking the leg.''' | ||

C having gained the sword of D, this same C turns a riverso to the leg of the figure noted as D. During the attack of the riverso, D is able to make a stramazzone to the arm or a thrust to the face as a result of it being tipped too far forward. As seen in the figure, D throws the right leg back in the attack. Always, I say, that when D was stringering C, had C been clever, he would have given a riverso to the face followed by a mandritto fendente to the head and thus he would have been safer. | C having gained the sword of D, this same C turns a riverso to the leg of the figure noted as D. During the attack of the riverso, D is able to make a stramazzone to the arm or a thrust to the face as a result of it being tipped too far forward. As seen in the figure, D throws the right leg back in the attack. Always, I say, that when D was stringering C, had C been clever, he would have given a riverso to the face followed by a mandritto fendente to the head and thus he would have been safer. | ||

| Line 1,069: | Line 1,069: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Capo Ferro | + | | [[File:Capo Ferro 09.png|400x400px|center]] |

| '''A figure that attacks in a passata while the adversary disengages in order to wound.''' | | '''A figure that attacks in a passata while the adversary disengages in order to wound.''' | ||

Figure D having gained the sword on the inside of the figure noted as C, the same C disengages to give a stocatta to the face of D. D attacks him to the face in second with a passing step making a grip with the left hand at the same time of the hilt of the enemy's sword. I will never fail to say that had the one called C been a clever person, he would have disengaged as a feint with his body held back to the rear. D advancing confidently to pass, C falsing underneath his sword and turning an inquartata with a void of the body, passing his leg crossed behind, would wound him in the chest. | Figure D having gained the sword on the inside of the figure noted as C, the same C disengages to give a stocatta to the face of D. D attacks him to the face in second with a passing step making a grip with the left hand at the same time of the hilt of the enemy's sword. I will never fail to say that had the one called C been a clever person, he would have disengaged as a feint with his body held back to the rear. D advancing confidently to pass, C falsing underneath his sword and turning an inquartata with a void of the body, passing his leg crossed behind, would wound him in the chest. | ||

Revision as of 01:17, 18 July 2020

| Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli | |

|---|---|

| 200px | |

| Born | 16th century |

| Died | 17th century |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Patron | Federico Ubaldo della Roevere |

| Influences | Camillo Aggrippa |

| Influenced | Sebastian Heußler |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) | Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (1610) |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli (Ridolfo Capoferro, Rodulphus Capoferrus) was a 17th century Italian fencing master. He seems to have been born in the town of Cagli in Urbino and was a resident of Siena, Tuscany. Little is known about the life of this master, though the dedication to Federico Ubaldo della Roevere, the young son of Duke Francesco Maria Feltrio della Roevere, may indicate that he was associated with the court at Urbino in some capacity. The statement at the beginning of Capo Ferro's treatise describing him as a "master of the great German nation"[1] likely signifies that he was faculty at the University of Siena, either holding a position analogous to dean of all German students, or perhaps merely the fencing master who taught the German students.

Capo Ferro authored a fencing manual on the rapier entitled Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma ("Great Representation of the Art and Use of Fencing"); it was published in Siena in 1610 and refers to Federico by the ducal title. Though this treatise is highly praised by modern fencing historians, it is neither comprehensive nor particularly innovative and does not seem to have been terribly influential in its own time.

Contents

Treatise

Images |

Complete Translation |

Transcription |

|---|---|---|

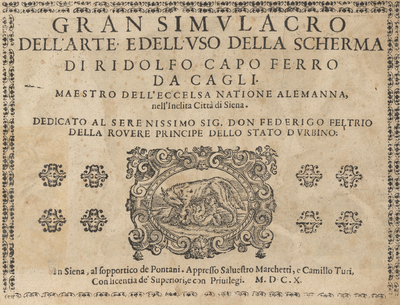

| GREAT REPRESENTATION OF THE ART AND USE OF FENCING by Ridolfo Capo Ferro of Cagli

Maestro of the Most High German Nation, in the Famous City of Siena Dedicated to the Most Serene Signore Don Federigo Feltrio della Rovere, Prince of the State of Urbino. In Siena, at the underporch of the Pontani. Printed by Salvestro Marchetti and Camillo Turi. With license of the Superiors, and with Privileges. 1610. |

GRAN SIMVLACRO DELL'ARTE EDELL'VSO DELLA SCHERMA DI RIDOLFO CAPO FERRO DA CAGLI

MAESTRO DELL'ECCELSA NATIONE ALEMANNA, nell'Inclita Città di Siena DEDICATO AL SERENISSIMO SIG. DON FEDERIGO FELTRIO DELLA ROVERE PRINCIPE DELLO STATO D'VRBINO. In Siena, al sopportico de Pontani. Appresso Saluestro Marchetti, e Camillo Turi. Con licentia de' Superiori, e con Priuilegi. M.D.C.X (Transcribed by Michael Chidester) | |

| To the Most Serene Signore Don Francesco Maria Feltrio della Rovere, sixth Duke of Urbino.

Every father (Most Serene Signor Duke), in order that his children should acquire reputation, procures for them some place in some noble court, and of some protection, to provide for them the best that he can. Thus do I, which, finding the present book on the instruction of fencing born of the better part of me, attempt to place in court, and because more dear to me than any other are the progeny of my intellect, I plead with Your Highness to grant them some place in your court, which, being a perfect compendium of the world, considered perfect, shown in and of itself of so much beauty and goodness as is found in the world, the same is dedicated to the Most Serene Don Federigo, your son, recommending it to his protection, although a lad in child’s gowns, and in jests, and gay dances, it appears nonetheless that there are enfolded in his hands triumphs and spoils, and as young Alcide2 with infantile hand, not yet equal to the purpose, menaces the Hydra, slays the serpents, then in the generous shining of his aspect is seen the greatness of his ancestors, the magnanimity, the valor, and the innumerable other virtues, which have exhausted the greatest and most famous historians, and which will render him above every Prince, and named and illustrious; would they not prove sufficient to confer such eminence, in truth only the virtues of Your Excellency being in number and quality so great, that it rightly could come to be called a diligent imitator of the perfection of GOD? It is not to be marveled at, therefore, by Your Highness, if I long to introduce into your Most Serene House, and place under the protection of the Most Serene Prince, your son, this book of mine; but considering the singular graciousness, very characteristic of Your Highness and of his Most Serene Blood, I cannot but strongly hope that Your Highnesses, without regarding the baseness of the subject, will favor it fully with your most powerful favor. But whereas indeed it may not be proper for Your Highnesses to receive such baseness with such grace, consent at least (as I humbly beseech you) that it can stand alone in the public hall of your Royal Palace, and in the other public places of your ample Dominion, as much glory moreover will arise merely from the authority of having a place among those who are humbly dedicated to serving and revering Your Highnesses, for whom I pray to the Lord God for complete and perpetual happiness. |

AL SERENISSIMO SIGNORE DON FRANCESCO MARIA FELTRIO DELLA ROVERE DVCA SESTO D’VRBINO.

OGNI Padre (Serenissimo Signor Duca) acciò che i figliuoli suoi acquistin reputatione, procaccia lor qualche luogo in qualche nobil Corte e di qualche protetione li provede, la maggiore che può. Così fo io, il quale, trovandomi il presente libro d’Ammaestramenti di Scherma, parto della parte migliore di me stesso, procuro di mandarlo in Corte, e perchè son più cari d’ogn’altro i parti dell’intelletto, supplico V. A. a concedergli qualche luogo nella sua Corte, la quale essendo un perfetto compendio del mondo, considerato perfetto, mostra in sè quanto di bello e di buono si trova nel mondo istesso, e dedicandolo al Serenissimo DON FEDERIGO suo Figlio, il raccomando alla sua protetione; il quale, benchè fanciullo in fasce, e scherzi e rida, par nondimeno che ci ravvolga per le sue mani trionfi e spoglie e, come novello Alcide, con pargoletta mano, non ancor pari alle voglie, minaccia l’Idra, uccide i Serpenti, poichè nell’aspetto suo generoso rilucer si vede la grandezza de’ suoi maggiori, la magnanimità, il valore e l’innumerabili altre virtù che hanno stancati i maggiori e più famosi Istoriografi, e che lui renderanno, sopra ogni nominato Principe, e nominato ed illustre, alla quale eminenza si basterebbono in vero le sole virtù dell’A. V., in numero ed in qualità così grandi che ella può venir direttamente chiamata imitator diligente della perfettione di DIO. Non si maravigli dunque l’A. V. se io bramo d’introdur nella sua Serenissima Casa e d’appoggiare alla protetion del Serenissimo PRINCIPE suo Figliolo quaesto mio libro, ma considerando qual sia la forza dell’affetto paterno mi scusi dell’ardimento mio. Io, certamente considerata la singolar benignità molto propria di V. A. e del suo Serenissimo Sangue, non posso non fermamente sperare che l’AA. VV., senza riguardar la bassezza del suggetto, il favoriranno compiutamente del potentissimo favor loro. Ma dove pur non fusse convenevole all’Altezza loro ricevere a tanta gratia cotanta bassezza, consentino almeno (di che humilmente le suplico) che starsene possa nella publica sala del lor Regio Palazzo e ne gli altri publici luoghi del loro ampio Dominio, chè molta gloria etiamdio sarà il poter solamente haver luogo fra quegli che si sono humilmente dedicati a servire e riverire le VV. SS. AA., alle quali prego dal Signore Iddio intera e perpetua felicità. | |

| From Siena on the 8th of April, 1610. Your Most Serene Highness’s Most Humble Subject, and Most Devoted Servant, Ridolfo Capo Ferro of Cagli. |

Di Siena, il dì 8. Aprile. 1610. Di V. A. S. Umilissimo Suddito e Devotissimo Servo Ridolfo Capoferro da Cagli | |

| TO THE GRACIOUS READER RIDOLFO CAPO F. DA CAGLI.

It is not my intention to hold you at bay with pompous and splendid words, in the recommending to you of the profession of arms that I practice. It is extolled in the due order of its merit, for which it is greatly prized and honored, and always praised, and the greatness and valor are commended of those who worthily carry the sword at their side; among whom today shines gloriously the Most Illustrious Signor SILVIO Piccolomini, Grand Prior of the Religion of the Knights of Saint Stephen in Pisa, and General of the Artillery and Master of Chamber of S.A.S. because not only is he endowed with full and marvelous advantage of that of the sword, but also of every other chivalric art, as his heroic actions by the same, to the wonder of all, clearly make manifest. But to turn to the sword, I say it is the noblest weapon above all others, in whose handling the majority of the industry of the art of fencing is honorably employed; therefore according to my judgment, the carrying of arms does not alone constitute the entire work, and that is not what makes the essential difference between a completely valorous man, and a vile and cowardly one, but as well the profession that someone practices to know how to employ them valorously in legitimate defense of himself and of his homeland, which no one truly can do with honor, if he has not first humbled himself, and placed himself under the law and rules of the discipline of fencing. Which, in the manner of sharpened flint, and honing valor, reduces him to the apex of his true perfection. The reason being that this science is laudable and so overly precious, that rather it would be a hopeless work to want to undertake the task of recounting all of its excellence; I do not believe that any rebuke must fall upon me, because I have set myself to press it into terms of undoubtedly brief, infallible, and well ordered precepts, avoiding as much as possible the blind and dark confusions, the deceitful and fallacious uncertainties, and burdensome and ambitious long-windedness. Now, even as through recognition of my weak faculties, I do not presume to have the joy of success of the full response to the fervor of my most ardent desire, so am I assured that my sincere and cordial labor has not turned out to be accomplished in vain, deferring such to comparison to those who dealt with the same topic before me. Considering that such thing relied upon the virtue of that by whose favor all graces descend unto us, I hope fervently, by these more faithful instructions of mine that may serve no less useful and delightful to you than showy ones, for a small particle of that sweet display of the true glory, that it pleases the graceful spirits always to courteously offer to one who with sincerity of heart goes perpetually laboring in their honored services. |

A I BENIGNI LETTORI RIDOLFO CAPOFERRO DA CAGLI

NON è la mia intentione di tenervi a bada con pompose & splendid parole nel raccomandarvi la professione dell’arme, che io fo. Essa, sublimata nel debito grado al suo merito, da per sè si pregia & honora assai, & tuttavia loda & commenda la grandezza & il valor di quegli che degnamente portano la spada a lato. Tra i quali, hoggi gloriosamente risplende l’Illustrissimo Signor SILVIO PICCOLOMINI Gran Priore della Religione de’ Cavalieri di Santo Stefano in Pisa & Generale dell’Artiglierie e Mastro di Camera di S. A. S., perciò che non pure è fornito, a pieno & con meraviglioso avantaggio di questa, della spada, ma ancora d’ogni altra arte Cavalleresca, come l’heroiche sue attioni appresso l’istesso, con istupore di tutti, appresso si manifestano. Ma per tornare alla spada, dico ella essere arme sopra ad ogn’altra nobilissima, nel cui maneggio il più dell’industria dell’arte della Scherma honoratamente s’impiega, perciò che secondo il mio giuditio il portar l’arme solo non fa l’opera intera; & non è quello che fa essentiale differenza da un huomo compiutamente valoroso a un vile & codardo, ma sì bene la professione, ch’altrui fa di saperle adoprare valorosamente in legittima difesa di se stesso & della Patria sua, la quale veramente nessuno può fare con suo honore, se prima non s’humilia & sottomette alle leggi & regole della disciplina della scherma; la quale a guisa di cote affinando & assottigliando il valore, lo riduce al colmo della sua vera perfettione. Laonde essendo questa scienza sì lodevole & tanto pregiata che soperchio, anzi opera perduta, sarebbe voler prendere l’assunto di raccontare tutte le sue eccellenze, non credo che in me habbia da cadere veruna riprensione perchè mi sia messo a stringerla nei termini di certi brevi, infallibili & ben ordinati precetti, schivando al più possibile la cieca & oscura confusione, l’ingannevole e fallace incertezza & la disutile ed ambitiosa prolissità. Hora, sì come per la conoscenza delle deboli forze mie non presumo che la felicità del successo habbia del tutto risposto al fervore del mio ardentissimo desiderio, così m’assicuro che la mia honesta & cordial fatica non mi sia riuscita vana a fatto, rimettendomi in ciò al paragone di chi innanzi me trattarono il medesimo suggetto. Per la qual cosa, confidato nella virtù di quello dal cui favore tutte le gratie in noi discendono, spero fermamente che da questi miei più fedeli che appariscenti ammaestramenti, sia per tornare non meno a voi utile e diletto, che a me una piccola particella di quel dolce saggio della vera gloria, che a gli animi grati sempremai piace di cortesemente porgere a chi con sincerità di cuore si va continuamente affaticando ne’ loro honorati servigij. |

Images |

Complete Translation |

Transcription |

|---|---|---|

GENERAL TABLE OF THE ART OF FENCING

|

TAVOLA GENERALE DELL’ARTE DELLA SCHERMA

| |

| Chapter I: Of Fencing in general

1) There is nothing in the world to which Nature, wise mistress and benign mother of the universe, with greater genius, and more solicitudinous regard, than for the conservation of one’s self provides him (of which Man is, more so than any other noble creature, demonstrating himself very dear of his safety), as the singular privilege of the hand, with which not only does he go procuring all things necessary for the sustenance of his life, but if he arms himself yet with the sword, noblest instrument of all, protects and defends himself, against any willful assault of inimical force; nonetheless following the strict rule of true valor, and of the art of fencing. |

CAPITOLO I Della scherma in generale.

1 Non è cosa al Mondo alla quale la Natura, savia Maestra & benigna Madre dell’universo, con maggior ingegno & più sollecitudine riguardi che alla conservatione di se stessa, della quale essendo l’huomo, sopra ad ogn’altra, nobilissima creatura, mostrandosi molto tenera della sua salute, lo provvide, come di singolar privilegio, della mano, con la quale non solamente va procurando tutte le cose necessarie per sustentatione della vita, ma si arma ancor di spada, nobilissimo instrumento di tutti, per riparare & difendersi con essa contra qual si voglia assalto di forza nemica, però secondo la dritta regola del vero valore & dell’arte della scherma. | |

| 2) Hence if one would clearly discern how necessary to man, how useful, and honorable may be the said discipline, and how it is that to everyone it may be necessary, and good to them, and maximally in demand, those armed of singular valor are inclined to the noble profession of the military, to which this science is subordinate in the guise of an alternative or subservient discipline, as is the part to the whole, and the end of the middle is subject to the final end. | 2 Onde si puote chiaramente discernere quanto all’huomo sia necessaria, utile & honorata la detta disciplina & come che ad ogn’uno faccia mestieri, & stia bene a quegli, & massimamente richiesta, i quali armati di singolar valore sono inclinati alla nobile professione della militia, alla quale questa scienza è sottoposta, guisa di disciplina alternativa, o servente, sì come la parte al tutto & il fine di mezzo all’ultimo fine è suggetto. | |

| 3) The aim of fencing is the defense of self, from whence it derives its name; because “to fence” does not mean other than defending oneself, hence it is that “protection” and “defense” are words of the same meaning; whence one recognizes the value and the excellence of this discipline is such that everyone should give as much care thereunto, as they love their own life, and the security of their native land, being obligated to spend that lovingly and valorously in the service thereof. | 3 Il fine della scherma è la difesa di se stesso, dalla quale ancora prese il suo nome, perchè schermire non vien a dire altro che difesa, e schermo & difesa sono parole di medesimo significato; onde si conosce il pregio, & l’eccellenza di questa disciplina, che ad ogn’uno debba essere tanto cara quanto ama la sua propria vita & la salute della Patria sua, essendo obbligato a spender quella amorevolmente & valorosamente in servitio di questa. | |

| 4) Thence it is yet seen that defense is the principal action in fencing, and that no one must proceed to offense, if not by way of legitimate defense. | 4 Indi si vede ancora che la difesa è la principale attione nella scherma & che nessuno debba procedere all’offesa, se non per la via della legittima difesa. | |

| 5) The effective causes of this discipline are four. Reason, nature, art, and practice. Reason, as orderer of nature. Nature, as potent virtue. Art, as regulator and moderator of nature. Practice, as minister of art. | 5 Le cause efficienti di questa disciplina sono quattro: la Ragione, la Natura, L’Arte & l’Esercitio. La Ragione come dispositrice della Natura. La Natura come virtù potente. L’Arte come regola & moderatrice della Natura. L’Esercitio come ministro dell’Arte. | |

| 6) Reason orders nature, and the human body in fencing, is its defense, in reason is considered judgment and volition. Judgment discerns and understands that which must be done for its defense. Volition inclines and stimulates one to the preservation of self. | 6 La Ragione dispone la Natura & il corpo humano alla scherma e sua difesa; nella Ragione si considera il giuditio & la volontà. Il giuditio discerne & intende quello che deve fare per sua difesa. La volontà l’inclina & stimula alla conservatione di se stesso. | |

| 7) In the body, which in the guise of servant executes the commandments of reason, is to be considered in the body proper greatness: in the eyes the vitality, and in the legs, in the body, and in the arms, the agility, vigor, and quickness. | 7 Nel corpo, il quale a guisa di servitore esseguisce i comandamenti della Ragione, si considera nella persona la giusta grandezza, nell’occhio la vivezza e nelle gambe, nella vita e nelle braccia la scioltezza, gagliardezza e prestezza. | |

| 8) Nature orders and prepares matter, is the sketch, is the accommodation to such extent in order to contain the final form and perfection of art. | 8 La Natura dispone & prepara la materia e l’abbozza e l’accommoda alquanto per ricever l’ultima forma & perfettione dell’Arte. | |

| 9) Art regulates nature, and with more secure escort guides us according to the infallible truth, and by the ordinance of its precepts to the true science of our defense. | 9 L’Arte regola la Natura & con più sicura scorta ci guida per l’infallibile verità e per l’ordine de’ suoi precetti alla vera scienza della nostra difesa. | |

| 10) Practice conserves, augments, stabilizes the strength of art, of nature, and more so than science, begets in us the prudence of many details. | 10 L’Esercitio conserva, augmenta, istabilisce le forze dell’Arte, della Natura & oltre la scienza partorisce in noi la prudenza in molte particolarità. | |

| 11) Art regards nature and sees that owing to the small capacity of matter, it cannot do all that which it intends to do, and however considers in many details its perfections and imperfections, and in the guise of architect takes thereof and makes such a beautiful model that it is thus refined, and sharpens the rough-hewn things of nature, reducing them little by little to the height of their perfection. | 11 L’Arte riguarda alla Natura & vede che per la poca capacità della materia non può fare tutto ciò che intende di fare & però considera in molti particolari le sue perfettioni & imperfettioni, & a guisa d’Architetto ne prende & fa qualche bel modello e così affina & assottiglia le cose della natura dirozzate, riducendola a poco a poco al colmo della sua perfettione. | |

| 12) From nature art has undertaken in defending oneself the ordinary step, the third guard for resting in defense, and the second and fourth for offense, the tempo, or the measure, and the manner as well of the placement of the body, with the torso now placed above the left leg for self-defense, now thrown forward and carried on the right leg in order to offend. | 12 Dalla Natura l’Arte ha preso, nel difendersi, il passo ordinario, la guardia terza per stare in difesa & la seconda & quarta per offesa, il tempo o la misura, sì come ancora la positura della persona con la vita, hora posata nella gamba manca per difendersi, hora spinta innanzi e caricata nella gamba dritta per offendere. | |

| 13) Because without doubt the first offenses were those of the fists, in the making of them is seen the ordinary step. The third, the second, and fourth, it is yet seen, that many do the punch mostly in tempo and measure. | 13 Perchè senza dubbio le prime offese furono quelle della pugna, nel fare alle quali si vede il passo ordinario, la terza, la seconda e quarta; si vede ancora che molti sanno fare alle pugna molto a tempo & a misura. | |

| 14) Against this offense of the fist, of course was found the art of the stick, and this defense not yet sufficing, iron; I believe it is, that of this material were made little by little many diverse weapons, but always one more perfect than all others, owing to the multiplicity of its offenses, to wit that the sword was discovered, the perfect weapon, and proportioned to the proper distance, in which mortals naturally can defend themselves. | 14 Contro questa offesa delle pugna, senz’altro fu trovato dall’Arte il bastone &, non bastando ancora questa difesa, il ferro; e credo io che di questa materia si facessero di mano in mano molt’armi diverse, ma sempre una più perfetta dell’altra, secondo che moltiplicavano le offese, in fin che fu trovata la spada, arme perfetta & proportionata alla giusta distantia, nella quale i mortali naturalmente si possono difendere. | |

| 15) The weapons which are of length exceeding the distance of natural defense and offense are discommodious and abhorrent for use in civic converse, and the excessively short ones are insidious and with danger to life; owing to which, in republics founded upon justice of good laws, and of good customs, it always was, and is, prohibited to carry arms of which can be born treacherous and heedless homicides. On the contrary, in the ancient Roman republic, the true ideal of a good government, the use of arms was entirely prohibited, and to no one, however noble and great that there was, was it licit to carry a sword or other weapon, except in war, and those who in time of peace were discovered with arms, were proceeded against as against murderers. | 15 L’armi che di lunghezza eccedono la distantia della difesa & offesa naturale sono scommode & abborescenti dall’uso della conservation Civile, e le troppo corte son insidiose e con pericolo di vita; per il che nelle Repubbliche fondate nella Giustitia delle buone leggi e dei buoni costumi sempre fu & è proibito di portar l’arme, onde possano nascere tradimenti & disaveduti homicidij. Anzi nella Republica Romana antica, ov’era idea d’un buon governo, fu del tutto interdetto l’uso dell’armi & a nessuno per nobile e grande che fosse era lecito portare la spada o altr’arme fuor che nella guerra, & contro quelli che a tempo di pace si trovavano con armi, procedevano come contro omicidiali. | |

| 16) And the Roman soldiers, immediately upon arriving home, put down their arms together with their short uniforms, and soldiery, and assumed again their long civil robes, and attended to the studies and the arts of peace, because no Roman exercised the body (as says Salustio) without the brain, each one attending beyond the studies of war, to each office of peace, therefore desirous, the burden of war, themselves supported, and yet immediately upon the end of war, they heard no more of captain, of soldier, nor of military wages. | 16 Et i soldati Romani, subito che arivavano a casa deponevano l’armi insieme con l’habito soldatesco & repigliavano la veste lunga e Civile & attendevano alli studij & all’arti della pace, perchè nissuno Romano esercitava il corpo (come dice Sallustio) senza l’ingegno: ogn’uno attendeva oltre allo studio della guerra ad uno offitio della pace, per cui desiderio le gravezze della guerra si sopportano; & però subito finita la guerra non s’intendeva più nè Capitano, nè soldato, nè soldo nessuno. | |

| 17) In these times soldiers are a greater burden to Princes and to Lords, and more so to the populace in times of peace than in war, and because they are not trained in other studies than those of war, they hate peace, and much of the time they are the authors of turbulence and wretched counsel. | 17 A questi tempi i soldati sono di maggior gravezza a i Principi & alle Signorie & maggiormente a i Popoli nel tempo della pace che della guerra, & perchè non sono avezzi ad altri studij che a quelli della guerra, odiano la pace & il più delle volte si fanno autori de turbolenti e cattivi consigli. | |

| 18) But turning to our matter, I say that the sword is the most useful and just arm, because it is proportioned to the distance at which offense is naturally performed, and all arms, to the degree that they differ from this distance of natural defence and offense, are to that extent more bestial and adverse to nature, and therefore useless to civic converse; the one is the way of virtue and of true reason, and the other burdensome and coarse, from which nature never departs, keeping company with sin and ignorance, and sliding about by many routes; one is the straight line, which none but the artful knows how to do; the oblique lines are infinite, and anyone can do them. Whence in our times we see offenses and defences multiply themselves and the art unto infinity, human endeavour imitating nature from principles; and while it follows the traces thereof it is useful and advantageous to the human life, but as soon as it departs from the footprints of nature, it begins to degenerate from the nobility of its origin, and hurls itself into the snares of harmful fancy, and plunges human kind into the abyss of ignorance, leading it from the age of gold into the filthiness of mud. | 18 Ma tornando alla nostra materia, dico che la spada sia arme utilissima & giustissima, perchè è proportionata alla distantia nella quale naturalmente si fa l’offesa & tutte l’arme quanto più si discostano da questa distanza della difesa & offesa naturale, tanto sono più bestiali & più avverse alla natura & però inutili alla conservation Civile: una è la strada della virtù & della vera ragione, è quella faticosa & aspra, dalla quale la Natura mai si diparte; al vitio & all’ignorantia si discorre e sdrucciola per molte vie; una è la linea retta, la quale non sa fare se non l’artefice, le linee oblique sono infinite & le può fare ogn’uno. Onde vediamo a’ nostri tempi multiplicarsi l’offese e le difese in infinito; l’arte & l’industria humana da principio imita la Natura & mentre che seguita l’orme sue è utile & giovevole al vivere humano, ma subito ch’esce dalle pedate della Natura incomincia a tralignare dalla nobiltà della sua origine & si precipita per li trabucchi della nocevol curiosità e sprofonda la generation humana nell’abisso dell’ignoranza, conducendola dal secolo d’Oro nella bruttura del fango. | |

| 19) From the force of nature, art, and practice, as efficient causes of the defense of which, up until now we have treated, is born the advantage and disadvantage of arms, but principally derives from the just height of body and from the length of the sword; because a man, large of frame, and that carries a sword proportioned to his body, without doubt will come first to the measure. In regard of this, in order to compensate for the natural imperfections of those who are found to be inferior of height, I believe, that it is prohibited in certain lands to make the blade of a sword longer than another, which does not seem a just thing, that one, who is through nature superior, loses advantage still from art, necessitating to him to suffice the privilege of nature, which without manifest indignity, wanting to equalize him with the smaller, not able to take away from him in general, with bestowing a sword less long to him, than to those who are short, who by chance could have other advantages of art and of practice, which exceed those of nature, in which cases human prudence is not sufficient to provide imparticular things. | 19 Dalle forze della Natura, dell’Arte & dell’Esercitio, come cause efficienti della difesa delle quali fin’hora habbiamo trattato, nasce ogni vantaggio & disvantaggio dell’armi, ma principalmente deriva dalla giusta altezza della persona & dalla lunghezza della spada, perchè un huomo grande di persona & che porta una spada proportionata alla sua altezza, senza dubbio verrà prima a misura. In riguardo di questo, per soccorrere all’imperfettione naturale di quegli che si trovano inferiori di grandezza, credo che sia prohibito in certi paesi di fare una lama di spada più lunga dell’altra, chè non pare cosa giusta che quello ch’è di natura superiore si prevalga ancor dell’avantaggio dell’Arte, dovendo bastare il privilegio della Natura, il quale, senza manifesta indegnità, volendogli pareggiare con li più piccoli, non se li può torre in generale con attribuire una spada meno lunga a loro che alli piccoli, i quali per aventura potrebbono havere altri vantaggi dall’arte & dall’esercitio che avanzassero quelli della natura; a’ quali casi la prudenza humana non è sufficiente a provedere così in particulare. | |

| 20) The art of fencing is most ancient, and was discovered in the times of Nino, King of the Assyrians, who, through use of the advantage of arms, was made monarch and patron of the world; from the Assyrians the monarchy passed to the Persians; the praise of this practice, through the valor of Ciro, from the Persians, came to the Macedonians, from these to the Greeks, from the Greeks it was fixed in the Romans, who (as testifies Vegetius) delivered in the field masters of fencing, whom they named “Campi doctores, vel doctores” which is to say, guides, or masters of the field, and these taught the soldiers the strikes of the point and of the edge against a pole. Nowadays we Italians equally carry the boast in the art of fencing, although more in the schools than in the field, and in the use of the militia, considering that in these times war is made more with artillery, and with the arquebus, than with the sword, which moreover almost will not serve in order to secure victory. | 20 L’arte della scherma è antichissima & fu trovata a i tempi di Nino Re delli Assiri, il quale per uso e avantaggio dell’armi si fece Monarca & patrone del Mondo; dalli Assiri con la Monarchia passò a’ Persiani la lode di questo esercitio, per il valore di Ciro; da’ Persiani pervenne a’ Macedonesi, da questi a i Greci, da i Greci si fermò ne’ Romani, i quali (come testimonia Vegetio) menavano in Campo Maestri di scherma, i quali nomavano Campi ductores, vel doctores, che vuol dire guide o Maestri del Campo; & questi insegnavano a’ soldati di ferire di punta e di taglio contro a un palo. Hoggidì noi Italiani parimente portiamo il vanto nell’arte della scherma, ben che più nelle Scuole che in Campo, e nell’uso della Militia, atteso che a questi tempi le guerre si fanno più con l’artiglierie e con gl’archibusi che con la spada, la quale per altro non serve che per esequire la vittoria. | |

| 21) This discipline is art, and is not science, taking that is, the word “science” in its strictest sense, because it does not deal with things eternal, and divine, and that surpass the force of human will, but it is art, not done from manuals, but rather active, and serves very closely the civil science; because its effects pass together with its operation, in the guise of virtue, and being passed, they do not leave any chance of labor or of manufacture, as are employed in performing the plebian and mechanical arts, all of which, although some of them are celebrated with the name of nobility, at great length it surpasses and exceeds. | 21 Questa disciplina è arte e non scienza, preso però il vocabolo “scienza” nel suo stretto significato, perchè non tratta delle cose etterne & Divine & che trapassino le forze dell’arbitrio humano, ma è arte, non fattiva nè manuale, anzi attiva & ministra molto stretta della scienza civile, perchè li suoi effetti passano insieme con l’operation sua, a guisa della virtù, & essendo passati non lasciano nessuna sorte di lavoro o di manifattura, come usano di fare l’arti meccaniche & plebee, le quali tutte, quantunque alcune di esse con il nome della nobiltà si celebrano, di gran lunga trapassa & avanza. | |

| 22) The material of fencing is the precepts of defending oneself well with the sword; its form, and the order is the truth of its rule, always true and infallible. | 22 La materia della scherma sono i precetti di ben difendersi con la spada; la sua forma e l’ordine & la verità delle sue regole, sempremai vere, è infallibile. | |

| 23) But it is time at last, that gathering all up, which heretofore we have said in brief words, we come to lay the foundation of this discipline, which is its true and proper definition, following the rule from which we will guide and direct the rest of all its precepts. | 23 Ma è tempo hormai che raccogliendo il tutto che fin’hora habbiamo detto in brevi parole, veniamo a porre il fondamento di questa disciplina, il quale è la sua & propria difinitione, di cui incaminaremo & indirizzaremo il rimanente de tutti i suoi precetti. | |

| Chapter II: The definition of fencing, and its explanation.

24) Fencing is an art of defending oneself well with a sword. |

CAPITOLO II La difinitione della scherma & la sua dichiaratione.

24 La scherma è un’arte di ben difendersi con la spada. | |

| 25) An art, because it is an assembly of perpetually true and well-ordained precepts, useful to civil converse. | 25 E’ arte perchè è una ragunanza de precetti perpetuamente veri e ben ordinati & giovevoli alla conservation Civile. | |

| 26) The truth is a disposition of precepts of fence; it must not be measured following the ignorance of some, who teach and write owing to the long use of arms that they have; and not owing to knowledge, but rather more often they make of shadow, substance; and of chance, reason; mixing gourds with lanterns, and pole-vaulting in shrubbery; but one must esteem those who constrain themselves to the truth of its nature. | 26 La verità e dispositione de’ precetti della scherma non s’ha da misurare secondo l’ignoranza d’alcuni, che insegnano & scrivono per l’uso lungo dell’armi che hanno & non per scienza, & però il più delle volte fanno dell’ombra sostanza & del caso ragione, mescolando zucche con lanterne & saltando di palo in frasca, ma si deve estimare da sè & ristretta nella verità della sua natura. | |

| 27) Their utility is manifest, because they teach the mode of defense, that is very naturally just, and honest, and that cannot be doubted to be of the greatest utility that it delivers to human life, because daily they discern it manifestly in its effects. For as much as that the sword is a commodious weapon to defend oneself in just distance, in which one and the other can naturally offend, we see that the combatants, almost always resting in the defense, rarely come to the offense, which is the last remedy for saving their life, which they would not have, if the arms were disproportionate, that is, either greater or lesser than the natural defense looks for. | 27 L’utilità loro è manifesta, perchè insegnano il modo della difesa che è molto naturale, giusta & honesta, & non si può dubitare del grandissimo giovamento che arreca al vivere humano, perchè giornalmente si scorgono manifestamente i suoi effetti. Imperocchè essendo la spada arme accomodata a difendersi in giusta distanza, nella quale l’uno & l’altro può naturalmente offendere, vediamo che restando i combattenti quasi sempre nella difesa, rare volte vengano all’offesa, la quale è l’ultimo rimedio di salvar la sua vita; il che non averebbe se l’arme fosse sproporzionata, cioè o maggiore o minore che ricerca la difesa naturale. | |

| 28) The aim which separates fencing from all other sciences, is to defend oneself well, however with the sword. | 28 Il fine che separa la scherma da tutte l’altre scienze è il ben difendersi, però con la spada. | |

| Chapter III: The division of fencing that is posed in the knowledge of the sword.

29) There are two parts to fencing, the knowledge of the sword, and its handling. The knowledge of the sword is the first part of fencing, that teaches to know the sword to the end to handle it well. |

CAPITOLO III La divisione della scherma, ch’è posta nel conoscimento della spada.

29 Due sono le parti della scherma, il conoscimento della spada & il suo maneggio. Il conoscimento della spada è la prima parte della scherma, che insegna a conoscere la spada a fine di maneggiarla bene. | |

| 30) The sword therefore is a pointed arm of iron, and apt to defend oneself in distance, in which one and the other can naturally and with danger of body offend. | 30 La spada dunque è un’arma di ferro, apuntata & atta a difendersi in distanza, nella quale l’uno & l’altro può naturalmente & con pericolo di vita offendere. | |

| 31) The material of the sword is the iron material of defense; without doubt it is found against that of wood it suffices little to beat aside, and disdain the injury, that one does daily to another. | 31 La materia della spada è il ferro, materia di difesa senza altro trovata contra quella di legno, poco bastante a ribattere e schifar l’ingiurie che l’uno a l’altro giornalmente usa di fare. | |

| 32) Its exterior form is that it is pointed; because if it were blunt, it would not serve to hold the adversary at the distance of natural offense. | 32 La forma sua esteriore è che sia apuntata, perchè se fosse spontata non servirebbe a tener lontano l’aversario in distanza di offesa naturale. | |

| 33) Its purpose is chiefly that of defense, which signifies chiefly to hold the adversary at a distance such that he cannot offend me, which sort of defense, and natural limits, enabling it to put into action, without injury of my fellow man. And in the Latin tongue, as it is already heard said with grammatical certainty, “defend” does not mean other than “avoid”, or truly to distance oneself from a thing that can harm, if one comes too near thereunto. | 33 Il fin suo è la difesa, la quale significa primieramente tener lontano l’avversario tanto che non mi possa offendere, la qual sorte di difesa è massime naturale, potendola mettere in opra senza danno del prossimo mio. Et in lingua latina, come già udij dire ad un certo letterato, difender non viene a dir altro che scansar, o ver alontanar da una cosa che potesse nocere, se troppo si avvicinasse. | |

| 34) Hence the words “to defend” signify “to offend”, and strike, which is the ultimate and subsidiary remedy of defense, in case the enemy should pass the boundary of the first defense, and advance himself near to such extent, that I came in danger of coming to harm from him, were I not to take heed for myself; because of the fact, that the enemy crosses the boundaries of defense, entering into those of offense, I am no longer obligated to carry any respect for the conservation of his life, as he comes to my turn, with some arm, commodious to harm me, naturally indeed, as I say in the distance of being able to arrive to me. | 34 Dipoi la parola difendere significa offendere & ferire, che è l’ultimo & sussidiale rimedio della difesa, caso che l’inimico trapassasse i termini della prima difesa & s’avvicinasse talmente che io venissi in pericolo di venir da lui offeso se io non mi provedessi; perchè di fatto che l’inimico trascorre i termini della difesa entrando in quelli dell’offesa, non son più obligato a portar rispetto alcuno alla conservation della sua vita, venga alla volta mia con qual si voglia arme accomodata ad offendermi, naturalmente pure, come dico, nella distanza di potermi arrivare. | |

| 35) The purpose of the sword, which is to defend oneself in the said distance, is measured in its length. | 35 Dal fin della spada, il quale è difendersi nella detta distanza, si misura la sua lunghezza. | |

| 36) Therefore the sword has as much for its length as twice that of the arm, and as much as my extraordinary step, which length corresponds equally to that which is from the placement of my foot, as far as it is beneath the armpit. | 36 Adunque la spada ha da esser lunga quanto il braccio doi volte o quanto il mio passo straordinario, la qual lunghezza parimente risponde a quella che dalla pianta del mio piede infino sotto alla ditella del braccio. | |

| 37) There are two parts to the sword: the forte, and the debole. The forte begins from the hilt, extending as far as the middle of the blade; and the remainder is called the debole. The forte is for parrying, and the debole for striking. | 37 Due sono le parti della spada, il forte & il debile. Il forte comincia dal finimento infino a mezza lama & il debile si chiama il rimanente; il forte è per parare & il debile per ferire. | |

| 38) The edge is false, and true. The true is that which faces downward when the hand rests in its natural position, which, turning itself out, or from inside, outwards from its natural orientation, makes the false edge. The first orientation, that is, of the true edge, is to be recognized in third, which is the position of the sword in guard, and the other, that is, of the false edge, will appear manifested in the position of third, and second, which are orientations of the sword, not in guard, but in striking. | 38 Il filo è falso & dritto. Il dritto è quello che sta in giù quando la mano sta nella sua natural positura, la quale voltandosi in fora o di dentro fuor del suo natural sito fa il filo falso. Il primo sito, cioè del filo dritto, si conosce nella terza, che è la positura della spada in guardia & l’altro, cioè del filo falso, apparirà manifesto nella postura della quarta & seconda, che sono siti di spada non in guardia, ma nel ferire. | |

| 39) I divide only the debole into the true and false edges, and not the forte, because the consideration does not occur that is made in the forte, which serves no other purpose than to parry, and were it without edge, and dulled, it would not be at all amiss, in place of point in the forte and the hilt, not only for gripping the sword, but also for covering oneself and chiefly the head in striking. | 39 Divido solamente il debile nel filo dritto & falso & non il forte, perchè questa consideratione non accade che si faccia nel forte, che serve nonad altro fine che al parare, & però se fosse senza filo e rintuzzato, non sarebbe error nessuno; in luogo di punta nel forte è il finimento, non solamente per impugnare la spada, ma ancora per coprirsi, e principalmente la testa, nel ferire. | |

| Chapter IV: On Measure

40) Up until now we have discussed the first part of fencing, which consists of the knowledge of the sword; now we commence to treat of the second part, which is that of its handling. |

CAPITOLO IIII Della misura.

40 Fin hora habbiamo ragionato della prima parte della scherma, che consiste nel conoscimento della spada; adesso incominciaremo a trattare della seconda parte, che è quella del suo maneggio. | |

| 41) The handling of the sword is the second part of fencing, which shows the way of handling the sword, and is distributed among the preparation of the defense, and in the same defense, the preparation, and, in the first part of the handling of the sword, that places the combatants in just distance, and in convenient posture of body in order to defend themselves in tempo; and has two parts; in the first is discussed measure and tempo. | 41 Il maneggio della spada è la seconda parte della scherma, che mostra il modo di maneggiare la spada & si distribuisce nella preparativa alla difesa & nella difesa istessa; la preparativa è la prima parte del maneggio della spada, chè mette i combattenti in giusta distanza & in convenevole postura di persona per difendersi a tempo, & ha due parti: nella prima si ragiona della misura & del tempo. | |

| 42) In the second is treated of the disposition of the limbs of the body. | 42 Nella seconda si tratta della dispositione delle membra della persona. | |

| 43) Measure is taken for a certain distance from one end to the other, as for example in the art of fencing is taken for the distance that runs from the point of my sword to the body of the adversary, which is wide or narrow. From then it is taken for an apt thing to measure the said distance, which in the use of fencing is the natural braccio <i.e. arm length>, which measures all distances, which in the exercise of this art, has all the qualities, and conditions, that are expected of an accomplished measure. | 43 La misura si prende per una certa distanza da un termine all’altro, come per essempio nell’arte della scherma si piglia per la distanza che corre dalla punta della mia spada alla vita dell’avversario, che è larga o stretta. Di poi si piglia per una cosa atta a misurare la detta distanza, la quale nell’uso della scherma è il braccio naturale, che misura tutte le distanze, il quale nell’esercitio di quest’arte ha tutte le qualità & conditioni che ad una compiuta misura si aspettano. | |

| 44) The measure is a just distance, from the point of my sword to the body of my adversary, in which I can strike him, according to which, is to be directed all the actions of my sword, and defense. | 44 La misura è una giusta distanza dalla punta della mia spada alla vita dell’avversario, nella quale lo posso ferire, secondo la quale si ha da indirizzare tutte le attioni della mia spada & difesa. | |

| 45) The narrow measure is of the foot, or of the right arm; the measure of the foot is of the fixed foot, or of the increased foot. | 45 La misura stretta è del piede o del braccio dritto; la misura del piede è del piè fermo o del piede accresciuto. | |

| 46) The wide measure is, when with the increase of the right foot, I can strike the adversary, and this measure is the first narrow one. | 46 La misura larga è quando con l’accrescimento del piede dritto posso ferire l’avversario, & questa misura è la prima stretta. | |

| 47) The narrow fixed foot measure is that in which only pushing the body and leg forward, I can strike the adversary. | 47 La misura stretta di piè fermo è nella quale solamente spingendo la vita & gambe innanzi posso ferire l’avversario. | |

| 48) The narrowest measure is when the adversary strikes at wide measure, and I can strike him in the advanced and uncovered arm, either that of the dagger or that of the sword, with my left foot back, followed by the right while striking. | 48 La strettissima misura è quando a misura larga ferisco l’avversario nel braccio avanzato & scoperto, o sia quello del pugnale o quello della spada, con il piè sinistro indietro, accompagnato dal destro nel ferire. | |

| 49) The first wide measure is of a tempo and a half, the second is of a whole tempo, the third is of a half tempo, regarding the three distances, which according to their size require more or less speed of tempo, and this is enough to have said of measure. Following now is the doctrine of tempo. | 49 La prima misura larga è d’un tempo intiero & mezzo; la seconda è d’un tempo intiero, la terza è d’un mezzo tempo, rispetto alle tre distanze, le quali secondo la loro grandezza ricercano più o meno velocità di tempo; & questo basti di haver detto della misura. Seguita hora la dottrina del tempo. | |

| Chapter V: Of Tempo

50) The word “tempo” in fencing comes to signify three different things; chiefly it signifies a just length of motion or of stillness that I need to reach a definite end for some plan of mine, without considering the length or shortness of that tempo, only that I finally arrive at that end. As in the art of fencing in order to come to measure, I need a certain and just tempo of motion and of stillness, it doesn’t matter whether I arrive there either early or late, provided that I reach the desired place. We pose the example that I move myself to look for the measure, and that I go very slowly to find it, and that my adversary is so much fixed of body that I find it, although I have arrived somewhat late, nonetheless not at all can it jeopardize my plan; because I have arrived in tempo, considering that, as much length of time as I am myself in motion, precisely so much had my adversary fixed himself; thus my motion equals the tempo of the stillness of my adversary, and his stillness measures my motion precisely, and because in remaining in guard, and searching for the measure, is only to be considered the correspondence of the tempo, that the combatants in moving themselves, and in fixing themselves, mutually consume, that they arrive to a certain point of measure; according to this, in the said actions, the speed of the motion, and the shortness of the stillness do not come into consideration, but rather through taking the just measure, it is more useful that they go, as is often said, with a leaden sandal , with the weight counterpoised, and placed over the left leg in ordinary pace, a posture of body most apt for coming with consideration and with respect to apprehend the due measure. |

CAPITOLO V Del tempo.

50 Il vocabolo Tempo nella scherma vien a significare tre cose diverse: primieramente significa un giusto spatio di moto o di quiete che mi bisogna per venire a un termine definito per alcun mio disegno, senza considerare la lunghezza o brevità di quel tempo, solo che io alla fine pervenga a quel termine. Sì come nell’arte della scherma, per venire a misura, mi bisogna un certo & giusto tempo di moto & di quiete, non importa se vi arrivo o presto o tardi, purchè io giunga al luogo desiderato. Poniamo esempio che io mi mova a cercare la misura & che io vada pian piano a trovarla & che l’avversario mio tanto si fermi di vita che io la trovi, ben che io sia arrivato alquanto tardi, nondimeno niente può pregiudicare al mio disegno, perchè son arrivato a tempo, atteso che quanto spatio d’hora io mi sono mosso, tanto apunto il mio avversario s’è fermato, così il mio moto aguaglia il tempo della quiete del mio avversario & la sua quiete misura apunto il mio movimento, & perchè nello stare in guardia & nel cercare la misura solo si considera la corrispondenza del tempo che li combattenti nel moversi e nel fermarsi scambievolmente consumano, infino che arrivano a un certo punto di misura, per questo nelle dette attioni non viene in consideratione la prestezza del moto & la brevità della quiete, anzi per pigliar la giusta misura è più utile che vadino, come si suol dire, con il calzar di piombo, con la vita contrepassata & posata sopra la gamba manca in passo ordinario, positura di vita attissima a venire consideratamente & con rispetto a prendere la debita misura. | |

| 51) Next this word “tempo” is taken in the sense of quickness, in respect of the length or brevity of the motion or of the stillness. Thus in the art of fencing there are three distances, and different measures of striking, and through this again are found three distinct tempos, and here it is not wished to consider only that one comes to a certain end, but that one arrives also with a certain quickness and velocity, because the wide measure, that is, of the increased foot, requires a tempo, that is, a severing of stillness, either of movement of the sword, or of the bodies of the combatants, fairly brief, but not so brief as the narrow measure of the fixed foot; and the narrowest measure requires a fastest tempo, because each little bit that I move myself with the point of my sword, and each little bit that my adversary fixes himself, in the distance of narrowest measure, suffices me to effect my plan, because this tempo is briefest; however we will call it half a tempo, and consequently the tempo that is spent in striking from the less narrow measure of the fixed foot will come to make a whole tempo, and the last tempo, which is employed in striking from wide measure, which is of the increased foot, will be a tempo and a half. | 51 Appresso si piglia questa parola tempo in luogo di prestezza, rispetto alla lunghezza o brevità del moto o della quiete: così nell’arte della scherma sono tre distanze e misure diverse di ferire & per questo ancor si trovan tre tempi apartati; & qui non si vuol solamente considerare che si giunga ad un certo termine, ma che si arrivi ancora con una certa prestezza & velocità, perchè la misura larga, ch’è di piede accresciuto, vuol un tempo, cioè una perseveration di quiete o di movimento della spada o della vita delli combattenti, breve assai, ma non tanto breve, che la misura stretta di piè fermo; & la strettissima misura ricerca un velocissimo tempo, perchè ogni poco ch’io mi movo con la punta della mia spada & ogni poco che si ferma il mio avversario nella distanza della strettissima misura mi basta ad essequire il mio disegno; & perchè questo tempo è brevissimo, però lo chiameremo mezzo tempo & consequentemente il tempo che si consuma nel ferire di misura manco stretta a piè fermo verrà a fare un tempo intiero & l’ultimo tempo che s’impiega nel ferire di misura larga, che è di piè accresciuto, farà un tempo intero & mezzo. | |

| 52) In the first tempo, which is that of seeking the wide measure, one does not consider the quickness of the motion and of the stillness, nor is it necessary to measure it by half of a whole tempo, which manners of tempos are only to be regarded in striking. By which thing the posture of the body in the striking is entirely contrary to that which is observed in seeking the narrow measure; because the first posture is comfortable for going little by little to find the narrow measure, and the other is bold, and with speed one hurls oneself to strike. | 52 Nel primo tempo, chè quello di cercare la misura larga, non si considera la prestezza del moto e della quiete & però non fa mestieri di misurarlo per mezzo tempo intiero, le qual maniere di tempi solamente si riguardano nel ferire. Per la qual cosa la positura della vita nel ferire è tutto contraria a quella che si osserva nel cercare la misura stretta, perchè la prima positura è agiata per andare a poco a poco a cercare la misura stretta & l’altra è ardita & con velocità si avventa a ferire. | |

| 53) The tempo is not other than the measure of the stillness and of the motion; the stillness of the point of my sword measures the motion of the body of my adversary, and the motion of my adversary with his body measures the stillness of the point of my sword. Now, so that this tempo may be just, it is necessary that as much length of tempo as the body of my adversary is fixed, so much is the point of my sword moved, and thus, consequently, for example: I find myself in wide measure, with a will to come to narrow measure; now I move the point of my sword to come to the said terminus; meanwhile as I move myself it is necessary that my adversary fix his body, and thus the stillness of body of my adversary is the measurement of the point of my sword; and, however, if I moved myself to strike before my adversary finished fixing himself, because the tempo would be unequal, I would move myself in vain, or not without great danger to myself. We pose the case, that both of us move ourselves to find the measure, and the one and the other give each other to intend to have found it; both going to invest themselves, intervene so that the one and the other don’t hit, because the tempo in which they move themselves to strike won’t be just, in respect of the distance to which they must first arrive; in this example it is seen that the motion of my point measures the motion of the body of my adversary, and the motion of the point of my adversary measures the motion of my body. However in the times to come, many strike each other in contra tempo, having come at the same time to narrow measure. | 53 Il tempo non è altro che la misura della quiete e del moto; la quiete della punta della mia spada misura il moto della vita del mio avversario & il moto del mio avversario con la sua vita misura la quiete della punta della mia spada. Hora, acciò questo tempo sia giusto, bisogna che quanto spatio di tempo si ferma la vita dell’avversario, tanto si muovi la punta della mia spada; & così conseguentemente per essempio mi trovo in misura larga, con animo di venire a misura stretta, hora muovo la punta della mia spada per venire al detto termine, mentre che io mi muovo bisogna che l’avversario fermi la sua vita e così la quiete della vita del mio avversario è la misura del movimento della punta della mia spada. E però se io prima mi movessi a ferire che l’avversario mio finisse di fermarsi, perchè il tempo sarebbe diseguale mi moverei invano o non senza mio gran pericolo. Poniamo il caso che ambidue ci moviamo a cercare la misura e l’uno & l’altro si dia ad intendere di haverla trovata, andando ambidue ad investirsi: interviene che l’uno & l’altro non colpisca, perchè il tempo nel quale si mossono a ferire non fu giusto rispetto alla distanza alla quale dovevano prima arrivare; in questo esempio si vede che il moto della mia punta misura il moto della vita del mio avversario & il moto della punta dell’avversario misura il moto della mia vita. Però alle volte avviene che molti si feriscono l’un l’altro di contra tempo, essendo venuti ad un tempo eguale a misura stretta. | |

| 54) The tempo that has to be considered in wide measure requires patience, and that of the narrow measure, quickness in striking and in exiting. | 54 Il tempo che si ha da considerare nella misura larga richiede patientia & quello della misura stretta prestezza nel ferire & nel partirsi. | |

| 55) The tempo of the narrow measure is lost either through shortcoming of nature, or through defect of art and of practice. | 55 Il tempo della misura stretta si perde o per mancamento della natura o per difetto dell’arte e dell’esercitio. | |

| 56) Through shortcoming of nature, by too much slowness of the legs, of the arm, and of the body, which derives either from weakness or from too much bodily weight, as we see to come to men who are either too fat or too thin. | 56 Per mancamento della natura per troppa tardezza delle gambe, del braccio & della vita, la qual deriva dalla debolezza o dal troppo peso della persona, come vediamo avvenire a huomini o troppo corpolenti o troppo sottili. | |

| 57) Through defect of art, when one does not learn to find the narrow measure as is necessary, with weight carried on the left leg, with the ordinary pace, and with the right arm extended, because the things must move in company in order to produce one single effect, yet they have to move in a just distance; but if the point of the sword is very advanced and the leg back, or if the leg is advanced and the arm back, then the sword will never be carried with that promptness, justness, and speed, which is required; by which, those who come to find the narrow measure in disproportionate distance of limbs, although they arrive there, nonetheless they cannot be in tempo of striking, because they would lack the best tempo of the narrow measure, which is that of prompt justness, or quickness. | 57 Per difetto dell’arte quando la misura stretta non s’impara a cercare come si conviene, con la vita caricata in su la gamba manca, con il passo ordinario, & con il braccio dritto disteso, perchè le cose si hanno a muovere in compagnia, per producere ad uno effetto medesimo si debbono ancor muovere in una giusta distanza; però se la punta della spada è molto innanzi & la gamba addietro o se la gamba è innanzi & il braccio addietro, mai si porterà la spada con quella prontezza, giustezza & prestezza che si richiede; per la qual cosa quelli che in sé sproportionata distanza di membra vengono a cercare la misura stretta, benchè vi arrivono, nondimeno non possono essere a tempo di ferire, perchè li mancherà il miglior tempo della misura stretta, ch’è quella della pronta giustezza o prestezza. | |

| 58) Through lack of practice, tempo is lost for the reason that the body is not yet well loose of limb, or when the scholars acquire some wretched habit, going back to the vanities of feints, and disengages, and counter-disengages, and similar things thus done. | 58 Per mancamento dell’essercitio si perde il tempo, per cagione che la persona non è ancora bene sciolta di membra o quando li scolari prendono qualche uso cattivo, andando dietro alle vanità delle finte & delle cavationi & contracavationi & simil cose così fatte. | |

| 59) From this, which we have so far said, everyone will easily be able to understand to be falsest that which many say, that tempo is taken solely from the movement that my adversary makes with his body and sword; but it is necessary to have equal regard for my own motion, and not only to my motion and that of the adversary, but as well to our stillnesses; because tempo is not solely a measure of motion, but of motion and stillness. | 59 Da questo che fin’hora habbiamo detto, ogn’uno facilmente potrà comprendere esser falsissimo quello che molti dicono, che il tempo si prenda solamente dal movimento che fa l’aversario con la sua vita & spada, ma che bisogni aver parimente riguardo al moto mio proprio, e non solamente al moto mio & quel dell’avversario, ma ancora alla nostra quiete; perchè il tempo non è solamente misura del moto, ma del moto e della quiete. | |

| 60) And concluding this matter of tempo, I say that every motion and every stillness of mine and of my adversary make together a tempo, to such extant, that one and the other measures. | 60 E concludendo questa materia del tempo, dico che ogni moto & ogni quiete mia e del mio avversario fanno insieme un tempo, in quanto che l’uno l’altro misura. | |

| Chapter VI: Of the body, and chiefly of the head.

|

CAPITOLO VI Della persona, & primieramente della testa.

61 La testa veramente è cosa principale in questo esercitio, posta però nel suo debito loco, perchè è quella che conosce le misure & i tempi, onde bisogna che venga collocata in luogo ove possa far la sentinella & scoprire il paese da ogni banda. | |