|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Sigmund ain Ringeck/Sandbox

Ringeck's treatise might be said to have kicked off the modern HEMA movement; a complete transcription of the Dresden version was included by Martin Wierschin in his landmark Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des Fechtens in 1965, which was the first "HEMA book". This transcription was later translated to modern German by Christoph Kaindel in the 1990s. A new transcription was authored by Dierk Hagedorn in 2008 and posted on the Hammaborg site.

The first English translations were produced in 2001 by Jörg Bellinghausen and Christian Tobler. An early draft of Bellinghausen's translation of the long sword was posted on the ARMA site, whereas Tobler's translated was published by Chivalry Bookshelf in Secrets of German Medieval Swordsmanship. Jörg Bellinghausen indicates that he completed translation afterward, but it was lost in a computer mishap and he never reproduced it; instead, in 2003 David Rawlings completed his work by translating the remaining plays of the long sword as well as the short sword section. A fourth English translation was produced by David Lindholm and published in 2005 by Paladin Press in two volumes: Sigmund Ringeck's Knightly Art of the Longsword and Sigmund Ringeck's Knightly Arts of Combat: Sword-and-Buckler Fighting, Wrestling, and Fighting in Armor.

Other translations produced in the '00s include an anonymous French translation posted on the ARDAMHE site, Eugenio García-Salmones' Spanish translation in 2006 posted on the AVEH site (translated from the French), Gábor Erényi's Hungarian translation (posted on the Schola Artis Gladii et Armorum site), and Andreas Engström's Swedish translation posted on the GHFS site. In 2011, Keith Farrell translated the Swedish into a fifth English version.

All of these translations were based exclusively on the Dresden version, which was the only version known in the 20th century and thought to be unique until other versions began surfacing in the 21st.

The Glasgow Fechtbuch was identified in Sydney Anglo's 2000 opus as merely "[R. L.] Scott's Liechtenauer MS",[1] but it was eventually determined to contain writings of Ringeck. In 2009, the first 24 folia were transcribed by Anton Kohutovič and posted on the Gesellschaft Liechtenauers site, and the complete manuscript was translated by Dierk Hagedorn and posted on Hammaborg. It's unclear when the Rostock version was first identified as pertaining to Joachim Meyer, but it began circulating prior to 2009 and Kevin Maurer authored a partial transcription in 2011; Dierk Hagedorn posted a complete transcription in 2015 on Hammaborg.

On the other hand, the Salzburg version was well-known going back at least to Wierschin, and transcriptions were posted by Beatrix Koll on the Universitätsbibliothek Salzburg site in 2002 and by Dierk Hagedorn on the Hammaborg site in 2009; likewise, the Aubsburg version was known going back at least to Hans-Peter Hils, and a transcription by Werner Ueberschär was posted on the Schwertbund Nurmberg site in 2012. However, the fact that these manuscripts included fragments of Ringeck's gloss was not realized until they were added to Wiktenauer in the 2010s. Likewise, the Vienna version has been known as a manuscript illustrated by Albrecht Dürer for centuries, but the attribution of the short sword teachings to Ringeck wasn't made until Dierk Hagedorn's transcription of 2016.

In 2015, Christian Trosclair authored a sixth translation of the long sword section for Wiktenauer, which was the first that incorporated all five known versions of that section.

More recently, Stephen Ceney authored a seventh translation of the long sword section, based on Dresden and Glasgow, which he self-published in Ringeck · Danzig · Lew Longsword in 2020. He also authored the first translation of the Glasgow version of Ringeck's mounted fencing and donated it to Wiktenauer.

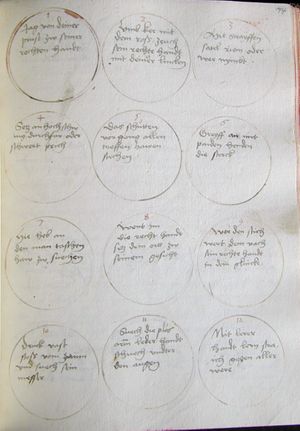

Illustrations |

Draft Translation |

Featured Translation |

Incomplete Translation (Dresden only) |

Incomplete Translation (Dresden only) |

Salzburg Version (1491) |

Dresden Version (1504-19) |

Glasgow Version (1508) |

Augsburg Version (1553) |

Rostock Version (1570) |

|---|

Illustrations |

Incomplete Translation (Dresden only) |

Dresden Version (1504-19) |

Vienna Version (1512) |

Rostock Version (1570) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[1] Here listen itself in the earnest fight from mounting and from foot All hear itself master Johannes Lichtenauer's fence in armor to Battle, that he has let be written with hidden words, they hereafter in this little book explained and unhide, so that each fencer who can understands art might, that another fencer can not. |

[1] The earnest fight on horse and foot. In St George's name here begins the art. Here begins the earnest fight on horse and foot. It begins here with Mr. Johann Liechtenauer's fence in the mail coat. This he has put down in secret words. That stands now laid out and explained, therefore every fencer can understand the art, who already understands how to fence. |

[1] Here begins the true fighting on horseback and on foot. Meister Johann Liechtenauers duelling in armour begins here, that he permitted it to be written down with secret words. That is now clarified and laid out in this book, so that every fighter of the art (who already understands duelling) can understand it. |

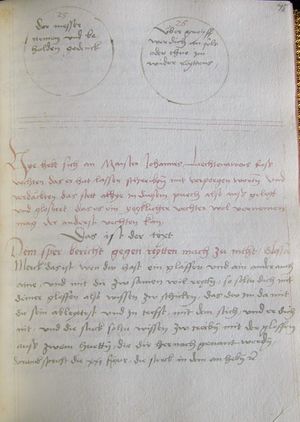

[89r] Hie höpt sich an der ernstlich kampff zu° roß vnd fu°ß Alhie hept sich ann Maiste~ Johannsen Liechtennawers vechten Im harnash zu° kampff Daß er hät laussen schriben mitt verborgen worten Das stet hie nach in disem biechlin glosiert vnnd vßgelegt Das ain ÿede~ fechte~ vernem~en mag die kunst de~ and anderst vechten kan ~ |

[105r] Hie hebt Sich an Meinster Johannes Liechtenawers vechtenn In harnachs [!] zw kampff das Er hatt lassen Schreybenn mitt verborgen worten Das Stett Hie In disem puch glosirett vnd außlegt Das Ein Iglicher vechter vernemen mag der anders vechten kan |

[98r] Hie hebt sich ann meister Joannes Liechtenawers vechtenn Im harnasch tzu kampf das er hat lassenn schreiben mit verborgen vnnd verdecktenn wortten das stet hie in diesem buch glosiert vnd ausgelegt das ein ietlicher vechter vernemen mag der annders vechtenn kann. |

||||||||

[2] This is the preface of the text

Explanation: Note, that you should understand this this way, when two on foot in armor one to the other will fence, then each man should have three wear, a spear, a sword and a dagger, and the first that you should bring is the long spear, with it you should rightly carry it in both arrangements, in two stances, as that here after will be explained. |

[2] Fight with the spear.

When two fight together in coats of mail, then each of them will have three different weapons: A spear, a sword and a dagger. And the beginning of the fight will occur with the spear. So you should prepare yourself with two ground positions, just as is now explained. |

[2] Fighting with the Spear

If two armoured men fight with each other on foot, then each should have three weapons: a spear, a sword and a dagger. And the fight should begin with the spear. So you should prepare for the first attack with two basic positions, as it is now explained. |

Die vor red mitt dem text Wer absinnet / Glosa Mörck daß solt du also versten Weñ zwen zu° fu°ssen in hamasch mitt ain ander fechten wollen So soll ÿeder man haben drÿerlaÿ wär / ain sper ain schwert vnd ain degenn Vnd daß erste anheben soll geschechen mitt dem lang langen sper Domitt solt du dich mitt rechter wer schicken In dem anheben In zwaÿen stendt alß du hernach hörn wirst ~ ~ ~~ |

Das Ist die vorred mit disem text Wer absinnet Glosa merck das Soltu also vernemen wen zwen zw fuß In harnachs mitt ein ander vechten wollen So soll Jeder man haben dreyerley wer Ein sper ein Schwertt ein degen vnnd das Erst anhebenn soll geschehenn mit dem Sper damitt soltu dich mitt rechter wer In dem anheben zw Schickenn In zwen Stend Als dw hernach horen wirdest |

Das ist die vorred mit dem Texte. Wer absinnet, Glosa. Merk das solstu also vernemen, wenn zween zu fuss in Harnisch mit ein ander fechten wollen, so sol Jedern haben dreierlei wher, ein Sper, ein schwerdt und ein degen und das erst anheben sol geschehen mit dem Sper, damit solstu dich mit verhser wehr [98v] in dem anhebenn zu schickenn, in tzwen steendt als du hernach horenn würdest. |

||||||||

[3] This is the text of the two stances

Explanation: This is the first stance with the spear, when you both form the saddle are dismounted, So then stand with the left foot forward and hold your spear by the wrap, and step this way to him all the way, that your left foot remains forward, and wait that you before him can shoot towards him and follow quickly the shoot against him with the sword, so that he can not have know which to shoot out and grab[2] the sword. |

[3] The first ground position.

When you are both down from the horses, Then stand with your left foot forward and hold the spear ready to throw. And close to him thus; so that the left foot always stays in front. And wait, so that you can throw before him. And follow on at once shooting forward with the sword, then he cannot safely cast against you, and grip the sword. |

[3] The First Basic Position

If you are both dismounted from your horses, then stand with the left foot forward and hold the spear ready. And approach him in such a way that your left foot always remains forward. And wait so that you can throw before him. And follow the shot immediately with the sword, then he cannot aim a safe throw against you. And grasp to the sword. |

Der text von zwaien stend~ Sper vnd ort / Glosa Daß ist der erst stand mitt dem sper [90r] Wann ir baÿde von den rossen abgetretten sind So stand mitt dem lincken fu°ß vor vnd halt din sper zu° dem schuß / vñ tritt also zu° im daß allweg din lincker fu°ß vor blÿb Vñ wart dz du ee schüsst den er vñ folg bald dem schuss nach zu° im mitt dem schwert So kan er kaine~ gewissen schuß vff dich haben Vñ grÿff zu° dem schwert ~ |

Das Ist der text von den zwen Stendenn Sper vnnd ortt Glosa merck das erst Stand mitt mutt [!] dem Sper wen Ire beid von den Rossen abgedrettenn seitt So stee mit dem linken fus vor vnd halt vnnd haltt [!] dein Sper mit dem Schus vnd dritt also zw Ime das albeg dein linker fuß vor bleib vnd [105v] wartt das dw Ee Scheust dan er vnd volg bald dem Schuß nach zw Ime mitt dem Schwertt So kan er keynen gewissen Schus auff dich habenn vnnd zw Ime mitt dem Schwertt |

Das ist der Text von den tzwen stendenn. Sper vnnd ort, Glosa. Merck das ist der erst stand mit dem Sper, Wenn ir baid vonn den Roßen abgetrettenn seitt so stehe mit dem linckenn fus vor, vnd halt dein sper tzu dem schus, vnd trit also tzu im, das alweg dein lincker fus vor bleib, vnd wart das du ee scheust dan er, vnnd volg bald dem schus nach tzu im mit dem schwert, so kan er keinenn gewisenn schuß auff dich habenn, vnnd greif tzu dem schwert. |

||||||||

[4] The second stance with spear Note: If you your spear will not throw, then hold it near your right side to the lower guard, and go this way to him, and stab artfully from below to the face, before than he does to you, if he then stabs to you equally or mis-places, then push him out with the spear in the high guard, so you remain with his point out to the left arm and with it then hang with the point over his arm in his face, if he push then out and mis-places with the left arm, then yank and place the point under his left armpit in the opening. |

[4] The second ground position. When you would not shoot[3] your spear, then hold it next to your right side in the lower guard and go to him thus. And stab him bravely from underneath at his face, before he does it [to you]. If he jabs at the same time or sets aside, then drive up in the high guard. So that his point remains on your left arm. Stab him at once with the point over his arm into his face. If he then drives up and sets aside with his left arm then jerk down and set the point in the opening of his left arm pit. |

[4] The Second Basic Position If you don't want to shoot your spear, then hold him near your right side in the lower guard and in that manner approach him. And thrust bravely from below to his face, before he does it. If he thrusts at the same time or deflects your thrust, then drive high in the high guard. Thus his point will remain on your left arm. Thrust immediately with your point over his arm into his face. If he drives high and deflects with his left arm, then jerk away downwards and set your point under his left shoulder in his opening. |

Der ander stand im sper Mörck ob du din sper nitt verschiessen wilt So halt es nebe~ dine~ rechten sÿtten zu° der vndern hu°tt vñ gee also zu° im Vnnd stich im ku~nlich von vnde~ vff zu° de~ gesicht Ee wann er dir Sticht er a dann mitt dir glich ein oder versectzt [90v] So far vff mitt dem sper in die obern hu°t So blÿpt dir sin ort vff dinem lincken arm Vnd mitt dem so heng im den ort über sine~ arm in sin gesicht / fört er dann vff vnd versetzt mitt dem lincken arm So züch vnd secz im den ort vnde~ sin lincke v~chsen in die blöß ~ |

Merck dw ob dw dein Sper nit verschiessenn wild So haltt Es nebenn deyner rechten seyten In der vndern hutt vnnd gee also zw Ime vnd Stich in kunlich von vnnden auff zw dem gesicht Ee wen er dir | sticht er den… [107v] …mit der gleich ein (?) oder versetzt So far auff mit dem Sper In die obern hutt so Bleibt dir sein ort auff deynem linken arm in seim gesicht fert er auff vnd versetzt mit dem linken arm so zuckt vnd setzt Im den ortt vnter sein links vchssen In die Blose |

Das ist der ander standt mit dem Sper. Merck ob du dein Sper nit verschießenn wilt, so halt es nebenn deiner Rechtenn seitten. In der vnternn hut, vnnd gehe also tzu im, vnnd stich Im künlich von vntenn auf tzu dem gesicht, ee wen er dir. sticht er denn. … [109r] …Mit dir gleich ein oder versetzt, So far auf mit dem Sper in die obernn hut, so bleibt dir sein ortt [109v] auf deinem linckenn arm, vnnd mit dem so heng im denn ort vber seinenn arm in sein gesicht, fert er denn auf vnnd versetzet, mit dem linckenn arm, so tzuck vnnd setz im den ort vnter sein lincke vchsenn in die plos. |

||||||||

[5] The text on how one should yank

Explanation: Note, that is, that you should well learn that you this way must yank “to someone that do not in-places that you yank-through”,[4] and take it this way, when you stab to him from the lower guard, if he out-places with the spear, that his point aside near to you goes out, so then yank through and stab to the other side, or if he holds you with the other out-placing with the point in front of your face, then do not yank and remain with the spear on the side, and work with the winding to the next opening that you might like. |

[5] The jerk with the spear.

When you stab from the lower guard, and he sets [it] aside with his spear, and his point to the side and goes beyond you,[5] then jerk through and stab him to the other side. Or if he stays with the point before his face, then don't jerk. But remain with the spear on his and wind to the next opening, that he opens to you. |

[5] The Jerking Away with the Spear

When you thrust out of the lower guard and he sets it aside with his spear, then his point goes past yours, then twitch through and thrust him to the other side. Or if he stays with the second setting aside with the point in front of the face then don't twitch, stay with the spear on his and wind to the next opening that offers itself. |

Der text wie man zucken soll Wilt du mitt stechen / Glosa Mörck daß ist / daß du wol lernen solt daß du also zuckest Vnnd vernÿm daß also wann du im vß der vndern hu°t zu° stichst Versectz er mitt dem sper / dz sin ort besÿzt besÿtz neben dir vß gat So zuck durch vnd stich im zu° der andere~ sÿtten Oder pleibt er dir mitt der andern [91r] versaczüng mitt dem ort vor de~ gesicht So zucke nicht / vñ pleÿb mitt de~ sper an dem sÿnen / vñ arbait mitt dem winden zu° der nechsten blöß die dir werden mag ~ ~ |

Das Ist der text wie man zuckenn Soll Wiltu zuckenn vonn Stechenn Glosa merke also das Ist das wol lernenn solt das dw also zwckes das man dir Icht an setz dieweill dw durch zwckes das vernim also wen du Im auß der vntern hutt zw Stichs versetzt er mit dem Sper das sein ortt nebenn dir beseitt auß gett so zuck durch vnd Stich Ime zw der andern seyten Oder pleibtt er dir mit der andern versatzung mit dem ortt vor dem gesicht so zuck nicht vnd Bleib mit dem Sper an dem Seynenn vnd arbeitt mitt dem windenn zw der nechsten plose die dir werdenn mag |

Das ist der Text wie mann tzuckenn sol. Wiltu vonn stechen Glosa. Merck also, das ist das du wol lernenn solt, das du also tzuckest das man dir nicht ansetze, dieweil du durchtzuckst. Das vernim also wenn du im aus der vnternn hut zu stichst, versetzt er mit dem sper, das sein ort neben dir beseit ausgehet, so tzuck durch, vnnd stich im tzu der andernn seittenn, Oder bleibt er dir mit der andernn versatzung mit dem ort vor dem gesicht, so tzuck nicht, vnnd pleib mit dem sper an dem seinenn, vnnd arbeit mit dem winden zu der nechstenn plos, die dir werdenn mag. |

||||||||

[6] This is the text

Explanation: Note, this is how you should race after with the spear, note, when you come forward with a stab, if he out-places and wish himself with the spear to pull it off, then follow him after with the point, strike him with it, then push him out from you, if he will from the point underneath flee and went to you to a side, so then wait that the same side charged and wisely take him with wrestling and with arm breaking as you will found written here. |

[6] The traveling after with the spear.

When you stab and he sets aside and loosens himself from the bind, then follow quickly with the point. Strike him with it. Then press[6] him in that way back. If he now wishes to flee backwards before the stab and turns aside close to you. Then run in on this side and grip him with such wrestling grips and arm breaks, just as you find described in the following. |

[6] Nachreisen with the Spear.

If you thrust towards him and he sets it aside and wants to free himself from the bind. then follow immediately with the point. If you hit him with it then shove him back with it. If he wants to fly backwards in front of your thrust and winds you to one side then walk into that side, grab him with such wrestling techniques and arm-holds as you find in the following descriptions. |

Der text Mörch will er ziechen / Glosa Merck daß ist wie du solt nachraisen mitt dem sper Mörck wañ du vorkumst mitt de~ stich verseczt er vñ will sich am sper abziechen So volg im nach mitt de~ ort / triftest du in do mitt So dring in für dich Will er dañ vß dem ort hindersich fliechen vnd wendt dir zu° ein sÿtten So wart dz du im zu° derselben sÿtten ein lauffest Vnd in wÿsslich begrÿffest mitt ringe~ [91v] vñ mitt armbrüchen alß du hernach geschriben fündest ~ |

[108r] Das Ist der text Merck will er ziehenn Glosa merck das Ist das dw solt nachreysenn mit dem Sper merck wen dw vor komst mit dem stich versetzt er vnnd will sich vom Sper abziehenn So volg Ime nach mit dem ortt Triffstu In damit So tring In fur dich will Er dan auß dem ortt hinter sich fliehenn vnd meint dir zw ein seytten So wartt das dw Ime zw der selbigen seytten ein lawffest vnd In weißlich begreiffest mit ring vnnd mit arm pruchenn als dw her nach geschribenn vindest |

[110r] Das ist der Text Merck wil er ziehen, Glosa. Merck das ist wie du solt nachreissen mit dem sper, merck wenn du vor kumbst mit dem stich, versetz er und wil sich von Sper abziehen so volg ihm nach mit dem ort trittsdu in damit, so tring in fur dich, wil er denn aus dem ort hintersich fliehen, und wendt dir zu ein seitten. So wart das du im zu derselbigen seitten, einlauffst und in weislich begreiffest mit ring, und mit armbruchen, als du hernach geschrieben findet. |

||||||||

[7] The text about wrestling to battle

Explanation: This is, when you go to him to wrestle, then you should know how you front or behind to the leg spring and it should happen with not more than one step. |

[7] The battle wrestle.

The throw behind over behind the leg. When you come in to fight him, then you should know, just as you should step in front or behind his leg, you should no longer need to step. |

[7] |

Der text von ringen zu° kampffe Ob du wilt ringen / Glosa Daß ist Wenn du mitt im kumst zu° ringe~ So solt du wissen wie du forne~ oder hinden für daß bain springe~ solt Vñ soll gescheche~ nicht mer dañ mit aine~ zu° tritt |

Das Ist der text vonn Ringenn zw kampff Ob dw wilt ringen Glosa merck das Ist wen dw mit Ime komest zw Ringenn So soltu wissen wie dw von oder hinden fur das pein springenn solt das er hatt vor gesetzt vnd das sol geschehenn vnnd nit mer dan mit eynem zw dritt |

Das ist der text von ringen zu Kampf Ob du wilst ringen, Glosa. Merck das ist wenn du mit ihm kombst zu ringen, so soldtu wissen, wie du vorn oder linken fur das bein springen. … [103r] …Solt das er hat vorgesetzt, vnnd das sol geschehenn nit mer denn mit einem zu trit. |

||||||||

[8] Item note then act this way When you hold him in the wrestling, and he against you, then see which foot he set forward, if he have the left forward then kick in his left foot[7] off with your right and with the kick then spring with your right foot behind his left and push him with the right knee behind, behind his his left knee and push him with both hands over that same knee. |

[8] When you [come to] each other, then be aware which foot he sets forward, then strike him to the left side with your right [foot]. From the beating aside, spring to him with your right foot behind his left, and press behind his knee joint with your right knee, and using both hands tear him backwards over your knee. |

[8] |

Item mörck de~ thu° also Wenn du in angriffest mitt ringen / vnd er dich wide~ / Welche~ fu°ß vor secz / hat er den lincken vor so schlach im sin lincke hand vß mitt diner rechten Vnnd mitt dem vßschlage~ so spring mitt dine~ rechten fu°ß hinden sine~ lincken [92r] vnd truck in mitt dem rechte~ knÿ hinde~ hinden In sin linck knÿckel vñ ruck in mitt baiden henden über daß selbig knÿ |

Item merck dem thw also wen dw Ine angreiffest mit Ringenn vnd er dich wider So sich welchenn fus er vorsetzt hatt er den linkenn fus vor so schlag So schlag Im den linken fus auß hand auß mit deyner Rechten vnd mit dem auß schlahenn so spring mit deynem rechten hinter seynen linken fus vnnd druck In mit deynem rechten knye In sein linke [108v] kniekyl vnnd Ruck Im|mit beiden hennden vber das selbig knye |

Item merck den thu also, wenn du in angreiffest mit ringen, vnnd er dich wider, so sihe welchen fus er vorsetzt. Hatt er denn linckenn fus vor, so schlag im sein lincke handt aus, mit deiner Rechtenn, vnd mit dem auschlag so spring mit dem Rechtenn fus hinter sein linckenn, vnnd druck in mit dem Rechten knie, in sein lincke kniekel, vnnd Ruck in mit baiden hendenn, vber daßelbig knie. |

||||||||

[9] Item, note one other When you jump with the right foot behind his left, then step[8] with your left behind both legs and take his left knee between the both knees and hold it with it firmly and push him with the left hand forward, “in the head”,[9] with the hew and with the right pull him behind, off to the side. |

[9] Or try the following. When you spring with your right foot behind his left, then go with your left foot between his legs. Clamp his left knee between both of your legs and hold it firmly. Push/thrust him in front against his forehead with your left hand, and with your right draw him backwards to behind him. |

[9] |

Item mörck ain anderß wenn du springst mitt de.~ rechten fu°ß hinder sine~ lincken So schrÿtt mitt dem lincken hin nach zwischen sine baide bain vñ faß sin linckes knÿ zwischen din baÿde knÿ vñ halt es domitt föst Vnnd stoß in mitt der lincken hand vorne~ an die haw~ben vñ mitt de~ rechtz zeüch in hinden vff die sÿtten ~ |

Item merck ein anders wen dw Springst mit dem Rechten fus hinter sein linkenn so schreit mit deim linken hinnoch zwischenn sein Beyde beynen vnnd fas sein linckes knie dein beyde knye vnnd halt es damit vest vnnd Stoß Inn mit der linckenn hand fornn an die hawbenn mit der Rechten zeuch In hinten auff die seyten |

Item merck ein anders, wenn du springst mitt dem Rechtenn fus hinter sein lincken, so schreit mit dem lincken hinach zwischen sein baiden painenn, vnd fas sein lincks knie, vnd halt es damit fest, vnd stos in mit der linckenn handt, vorn an die hauben, mit der Rechten zeuch in hintẽ auf ein seitten. |

||||||||

[10] This is the text

Explanation: This is, that you all wrestling should know to try from both sides, that is if you wish to end him with art, as you come to him, and that take it this way, when you with the right foot spring behind his left, if he steps then in the spring with his left foot to push, then follow him quickly to the other side with your left foot behind his right and throw him over the knee or kick him on that knee with your leg as before written is. |

[10]

You should control all wrestling techniques on both sides. Therefor you'll counter all that he attempts against you. When you have sprung with your right foot behind his left foot and he climbs back with his left foot, then follow him quickly to the other side with your left foot to behind his right foot. And throw him over over your knee with or lock his knee with both of your legs, as described earlier. |

[10] |

Der text Von baÿden henden / Glosa Daß ist daß du alle ringen solt wissen zu° tribenn võ baiden sÿtten Ist daß du mitt kunst enden wilt dar nach [92v] alß du an in kumst Vnd dz vernÿm also Wañ du mitt dem rechte~ fu°ß springst hinder sine~ lincken Tritt er dann im spru~g mitt sine~ lincken fu°ß zu° rucke So volg im bald nach zu° der andern sÿtten mitt dine~ lincken fu°ß hinder sine~ recht~ vñ wirff in über dz knÿ Oder verschlaiß im dz sin knÿ mitt dine~ bain alß vor geschriben stät ~ |

Das Ist der text Von beydenn hendenn Glosa das Ist das dw das Ringenn solt wissen zw treybenn von beydenn seyttenn Ist das dw mit kunst endenn wild darnach als dw an dich kumst vnd das vernim also wen dw mit dem Rechten fus Springst hinter seynen linkenn fus zw Ruck So volg Im bald nach zw der andern seytten mit dem linkenn hinter seynen Rechten vnnd wurff Ine vber das knye oder beschleus Im sein knie mit denn beynenn als vor geschribenn Stett |

Das ist der Text. [103v] Vonn baiden henden, Glosa. Das ist, das du das Ringen solt wissen zu treibenn vonn baidenn seittenn, Ist das du mit kunst endenn wilt, darnach als du ann Inn kumbst, Vnnd das vernim also. wen du mitt dem Rechtenn fus springst hinter sein linckenn, trit er dan im sprung mit dem lincken fus tzu Ruck, so folge im bald nach zu der andernn seittenn mit dem lincken fus hinter sein Rechten vnnd wirf in vber das knie, oder verschleus im sein knie mit denn painenn als vorgeschriben stehet. |

||||||||

[11] This is the text how one itself should arrange with the spear against the sword

Explanation: Note, this is when you your lance have miss shoot and he kept his, then arrange yourself this way against him with the sword, grip middle with the left hand, on the middle of the blade, and let the sword close to you middle of that knee, your left knee in the guard or hold it near your right side in the lower guard. |

[11] Sword against spear. Parry with the half-sword.

When you have thrown[10] your spear and he has kept his, then place yourself in the following position: Grip your sword in the middle of the blade and place it before your left knee in the guard. Or hold it next to your right side in the lower guard. |

[11] Sword against Spear. Parry with the half-sword.

When you have lost your spear, and he has kept his, then set yourself in the following position. Grab your sword with the left hand in the middle of the blade and lay it in front of yourself over the left knee in the guard or else hold it on the right side in the low guard. |

Daß ist der text wie man sich sol schicken mitt dem sper wide~ daß schwert ~~ Ob er sich ver ruckt / Glosa Mörck daß ist wann du din gleffen ver schosse~ hãst Vnd er behelt die sinen So [93r] schick dich also gegen im mitt de~ schwert Griff mitte der lincken hand mitte~ in die clingen vñ leg das schwert für dich mitten vff dz knÿ din linckes knÿ In die hu°t oder halt es neben diner rechten sÿtten In der vndern hu°t ~~~ ~ :· ~ |

Das ist der text wie man sich soll Schickenn mit dem Sper wider das Schwertt Ob es sich verruckt Glosa merck das Ist wen dw dein gleffen verschossenn hast vnnd er behelt dye seynenn So Nim eben war wie er sye gefast hab ob er den ortt lanck oder kurtz sein vorgesatzte hand lest fur gen oder ob er dir damit oben oder vnnden will zw Stechenn hatt er sye dan kurtz geuast vnd will [109r] In die obern hutt so leg das Schwertt fur dich auff dein lincks knye In die hutt |

Das ist der Text wie man sich sol schicken mit dem Sper wider das schwert. Ob es sich verruckt, Glosa. Merck das ist, wenn du dein glefen verschoßenn hast, vnnd er behelt die seinen, So nim ebenn war, wie er sie gefast hab, ob er denn ortt [104r] langk oder kurtz fur sein vorgesatzte handt lest fur gehenn, vnnd ob er dir damit obenn oder vntenn, wil tzu stechenn, hat er sie dann kurtz gefast, vnd wil damit in die obernn hut, so leg das schwert fur dich auf dein lincks knie in die hut. |

||||||||

[12] Item: Or if he stabs to you underneath, then set the stab out towards to your left hand and spring with the right behind his left and take him with the pommel from over his right shoulder around the neck and throw him over the knee. |

[12] |

[12] |

Item oder Sticht er dir vnndenn zw So setz den Stich ab vor deyner linkenn hand vnd Spring mit dem Rechten hinter seynen linkenn vnd far Im mit dem knopff forn vber sein Rechte achssell vmb den hals vnd wurff In vbers knye |

Item oder sticht er dich vntenn tzu, so setz denn stich ab vor deiner linckenn handt, vnnd spring mit dem Rechten fus hinter sein linckenn, vnnd far im mit dem knopf vornn vber sein Rechte achsel vmb den hals, vnnd wirf in vbers knie. |

|||||||||

[13] Item: Note, if he stabs you then with the lance above, then go off and set his stab out towards your left hand with the sword off your left side and spring to him and wait the in-placement, if you do not want to come that, then let your sword fall and wait the wrestling. |

[13] If he thrusts high with the spear, then drive high and parry the thrust in front of your left hand with the sword on your left side and spring towards him and set your point towards him. If thats not possible then let your side fall and go under with wrestling. |

Item mörck Sticht er dir dann mitt der gleffen oben eÿn zu° So far vff vñ secz im den stich ab vor diner lincken hand mitt de~ schwert vff din lincke sÿtten vñ spring zu° im vnd wart des anseczents Magst du deñ zu° nicht komen So lauß din schwert fallen vnnd wart der ringen |

Sticht er dir dan mit der gleuen oben zw so far auff vnd setz Im den Stich ab vor deyner linkenn hand mit dem Schwertt auff linke seytten vnd Spring zw Im vnd wartt des ansetzenn magstu dar zw nit kumen So las dein Schwertt vallen vnnd wartt der Ringen |

Sticht er dir dann mit der glefenn oben tzu, so far auf, vnnd setz im denn stich ab, vor deiner linckenn handt mit dem schwert auf sein lincke seittenn vnnd spring tzu im, vnnd wart des ansetzen, magstu dartzu nit kummenn, so las dein schwert fallenn vnnd wart der ringenn. |

|||||||||

[14] Item: If he stabs to you with the lance when you stand in the lower guard, then set his stab out with the sword towards your left hand, off to his right side, and wait the in-placement or the wrestling. |

[14] When he jabs towards you and you stand in the lower guard, then set [aside] his stab from with the sword before your left hand on his right side, and go over in setting aside or the wrestle. |

[14] If he thrusts towards you and you are standing in the lower guard then set his thrust aside with the sword in front of your left hand on his right side and go over with the attack or wrestling. |

Item sticht er dir zu° mitt der glefen wañ du stäst in der vndern hu°t So secz im den stich ab mitt dem schwert vor [93v] diner lincken hand vff sin rechte sÿtten vnd wart deß anseczents oder der Ringen ~ ~ ~ |

||||||||||

[15] The text about out-pacing with bear hands

Explanation: When you stand in the lower guard, if he stabs you from above with the spear and have catch that, that the point is away from the hand and goes out “and stabs with it above you”,[12] then hit him with your “left hand”[13] in middle of his spear out away, and hold your sword quickly against with the left hand middle in the blade and spring to him and set it in, etc. |

[15] Parry with the open hand.

When you stand in the lower guard, and he jabs above to you, and he holds the spear, so that the point in front broadly juts over the hands. Then strike his spear down to the side with your left hand, and spring to him setting the point on him. |

[15] |

Der text võ abseczen mitt lerer hand ~~ Lincke lanck von hand schlache Glosa Wenn du stau~st in der vndern hu°t Sticht er dir an oben zu° mitt dem sper vñ hat dz gefasst daß im der ort lang für die hand vsß gat vnd sticht dir domitt oben zu° So schlach in mitte der lincken hand sin sper beseÿcz abe / vnd begrÿff din schwert bald wide~ mitt der lincken hand mitten in der clingen vnd spring zu° im vñ secz im an etc |

Das ist der text vonn absetzenn mit lerer hannd Linck lanck von hand Glosa Merck das Ist wen dw steest In der vntern hutt Sticht er dir dan obenn zw mit dem Sper vnd hatt das gefast das Im der ortt fur die hanndt auß geet So Schlag Inne mit der Schwert beseyt ab vnd begreiff dein Schwertt bald wider mit der linkenn hand mitten In der clingenn vnd Spring zw Im vnd setz Im ann |

Das ist der Text vonn absetzen mit lerer handt. Linck lang vonn handt schlag, [104v] Glosa. Merck das ist, wenn du stehest in der vnternn hut, Sticht er dir denn oben tzu mit dem Sper, vnnd hat das gefast das im der ort langk fur die hanndt ausgehet, so schlag im mit der schwer beseit ab vnnd begreif dein schwert bald wider mit der linckenn handt, mittenn in der klingenn, vnd spring zu im vnd setz im an. |

||||||||

[16] Item: If he stabs you with the spear underneath to the stomach, then take his spear in the left hand and hold it with it firmly and stab him with the right beneath towards the stomach and push him than his spear firmly forward yourself and will your the off the hand races, then let the spear over him off the hand go, then if he gives himself an opening then hold your sword quickly with the left hand against middle of the blade and follow him quickly after and set him in. |

[16] When he stabs underneath with his spear, to your guts. Then grab his spear with your left hand and hold it firmly. At the same time stab him underneath in the gut. And if he then wants to pull strongly on the spear and jerk it from your hand, then press the spear up over and let him go. So that he gives you an opening. Grab your sword at once with your left hand, follow to him and set the point on him. |

[16] |

[94r] Item sticht er dir mitt dem sper vnden zu° dem gemächt So fahe sin sper in die lincken hand vñ halt es domitt vast vñ stich im mitt der rechte~ vnde~ zu° den gemächt Vnd ruckt er dañ sin sper fast an sich vñ will dir daß vsß der hand rÿssen So lauß daß sper über in vß der hand far So gibt er sich blöß So begriff din schwert bald mitt der lincken hand wide~ mitten in der dingen vñ volg im bald nach vnd secz im an ~~~ |

Item oder Sticht er dir mit dem Sper vndenn zw dem gemecht So vach sein Sper In die linkenn hand vnd halt es damit vaste vnd Sticht Im mit der Rechtenn vnnden zw dem gemecht vnd Ruck er dan sein Sper vast an sich vnd will dir das auß der hand reyssen So las das Sper vrbering auß der hand farn So gibt er sich plos So begreiffe sein Schwertt bald mit der linkenn hand wider mitten In der klingenn [109v] vnd volg Im Bald nach vnd Setz Ime ann |

Item oder sticht er dir mit dem sper, vntenn tzu dem gemecht so fahe sein sper in die lincken handt vnnd halt es damit fast, vnnd stich im mit der Rechtenn vntenn tzu dem gemecht, vnnd Ruckt er den sein sper fast ansich, vnnd wil dir das aus der hanndt reissenn, so las das sper urbering aus der hanndt farenn, so gibt er sich plos, so begreif dein schwert baldt mit der lincken hannd wider mittenn in der clingenn, vnnd volge im bald nach vnd setz im ann. |

||||||||

[17] The text about the openings

Explanation: This is, when you with an armed man will in-place, then you should the opening precisely take. The first is in the face, other below the armpit, other in the palms, other behind the gauntlets, other in the knee pits, other between the legs, other in all articulations of the armor his joint inside have, When he is steady, the best for winning and the openings you should rightly know to seek on the man, that you should not go after one far target when can take you a near one, that with all weapons that to the battle belong, etc. |

[17] When you set the point to an equipped[14] man.

Then you must quickly recognise his openings. At first try and strike him in the face, but also in the armpits, in the palms of the hands, or in from behind the gloves, or in the knee pits, between the legs and on all the limbs, where the coat of mail joins inside. Because these are the best place in which to strike him. And you should know precisely, how you can strike these openings. Therefore you will not aim at a more remote one, when you could hit a closer one with greater ease. Practice with all the arms, that pertain to the fight. |

[17] The openings of one who is armed

If you want to place an attack at a place on a prepared man, then you must detect his openings quickly. First attempt to attack him in the face, but also under the shoulders, in the palms of the hands or from the rear in the gloves, or in the hollows of the knee, between his legs and to all the members there, where the armour has his joints inside. Because it is best to attack him at these places. And you should know exactly how you can attack those openings, so that you do not aim at a further one if you can attack a closer one more easily. Practice that with all weapons which belong to the fight. |

Der text von den blossen Leder vnnd handschüch Glosa Das ist wañ du aine~ gewapnete~ man an seczen wilt So solt du der blöß eben war nemen Der ersten [94v] In daß gesicht / oder vnder den v°chsen / oder in den teñern / ode~ hinden in die handtschu°ch Oder in die knÿkeln oder zwischen den bainen oder in allen glidern da der harnosch sin gelenck iñen hat Wann an den stetten ist de~ man am besten zegewinnen vñ die blossen solt du recht wissen zu° su°chen / dz du nach aine~ nicht wÿt griffen solt wañ dir ain nächere werden mag / Daß tu° mitt aller were die zu° dem kanpff gehörent etc |

Das ist der text vonn den Blossen Leder hantschuch Glosa Das ist wan dw eynen gewappetten man ansetzenn wild So soltu der Bloeß eben war nemen des Erstenn In das gesicht oder vnter den vchssenn oder In den tener oder In den hantschuch oder In dye knyekelen oder zwischenn den peinen oder In allen glidern do der harnasch sein gelenck Innen hatt wen an den Stellen Ist der mann am besten zw gewinnen vnd der Bloessen Soltu Recht wissenn zw Suchenn das dw nach einer nit weitt greiffen Solt wen dir ein nehere werden mag das thu mit aller wer die zw dem kampff gehorenn |

Das ist der Text vonn denn plossenn. [105r] Leder vnnd hantschuch, Glosa. Das ist wenn du einem gewappenden man ansetzẽ wilt, so soltu der plöß ebenn war nemen, des ersten in das gesicht, oder vnter die vchsenn, oder in denn tener, oder hintenn in denn handschuch, oder in die kniekel, oder tzwischenn denn painenn, oder in allenn glidernn, da der harnasch sein gelenck Innen hatt, wenn an denn stettenn ist der man am bestenn zugewinnenn, vnnd die blössenn soltu recht wissen zu suchenn, das du nach einer nit weit greiffenn solt, wenn dir ein nehere werdenn mag, das thu mit aller wer die tzu dem kampf gehorenn. |

||||||||

[18] The text about the hidden wrestling

Explanation: This is when one to the other charges, then let your sword fall and wait with it carefully the wrestling that to the battle belongs hear that is forbidden from all known mastery of the sword, that to one to them are often teach to no one, nor learned nor should seek to reveal, because they to the battle fencing belong, and they are the arm breaking, leg breaking, testicles hits, the death hit, knee hit, finger dislocation, eye griping and more like that. |

[18] Secret wrestling techniques.

When he runs in, then drop your sword and use carefully the wrestling, that belong to the battle fight. These shall not be taught or shown in publicly accessible fencing schools, so is it from all to show sword mastery closed. Because he will to the earnest fight to use dignity, and there are arm breaks, leg pieces, testicle thrusts, death strikes, knee thrusts, finger breaks and eye grips[15] and more. |

[18] |

Der text von dem verborgnen ringen Verbotten Ringen / Glosa Das ist wañ ainer dem andern andern ein laufft So lauß din schwert fallen vñ wardt [95r] domitt wÿßlich der ringen die zu° dem kampff gehören / vñ verbotte~ sin von allen wÿsen maistern des schwerts Daß man die vff offenbare~ schu°len nÿemancz lernen noch seche~ lasen sol daru~ daß sÿ zu° dem kampff fechten gehörn vñ daß sind die armbrüch / Bainbruch / hoden stoß / mortstoß / knÿstoß / vinger lausunge / äugen griff / vnd dar zu° mer ~ ~ ~ :· |

Das ist der text mit den verpotten zw Ringen Verpottenn Ringen Glosa merck das Ist wen einer dem andern ein lawfft So las dein Schwertt zw hand fallen vnd wart damit weyßlich der ringenn die zw dem kampff gehorenn die verbotten sein von alten weissen meinster des schwertz das man auff offenbaren Schulen nyemantz lernen noch sehenn soll lassenn Darumb das sye zw dem kampff fechten gehorenn das sein die arm bruch vnd pein bruch zw hodenn stosß vnd mortt Stosß vnnd knye [110r] Stoeß vnd vinger losung vnd augenn greyffung vnd dar zw mer |

Das ist der Text vonn denn verpotnenn Ringenn. Verpottenn Ringen, Glosa. Merck das ist wenn einer dem andern einlauft, so las dein schwert zu handt fallenn, vn[d] [105v] wart damit weislich der ringens, die zi dem kampf gehoren, die verbotten sein, vom alten weisens Meistern des Schwerts, das man die auff offen waren schulen niemandts lernen nach ~sehen lassen darumb das sie zu° dem kampff fechten gehörn. Das sein die armbrüch / Bainbruch / hoden stoß / mortstoß / kniestoß / finger losing und äugen greiffen und darzu° mehr. |

||||||||

[19] Here you should note the wrestling Item: If "you grip someone"[16] above with wrestling and you wish with strength to pull or push him, then hit the right arm out over his left forward by his hand and press then with both hands on his chest and spring with the right foot behind his left and throw him over that knee of the foot. |

[19] The first technique. The cast over the leg to behind: When he seizes you you above and then draws you to him with strength to him or will thrust you from him, then strike the right arm outside over his left hand, just behind his hand. Press his arm with both hands at the breast, spring with your right foot behind his left and throw him over your knee. |

[19] |

Hie solt du morcken die ringen Item grifft dich an ainer oben mitt ringen vñ will dich mitt störck zu° im rucken oder võ im stossen So schlach den rechten arm vssen über sin lincken forne~ vorne~ bÿ siner hand vnnd truck den mitt baiden henden an din brüst vñ spring mitt dim [95v] rechten fu°ß hinde~ sinen lincken Vñ wirff in über dz knÿ vß dem füß ~ |

Hie merck die ringenn Item gerifft er dich obenn an mit ringen vnnd will dich mit Sterck zw Ime Ruckenn oder von Ime Stossenn So Schlag den Rechtenn arm aussenn vber sein glinckenn forn bey seyner hand vnnd truckt den mit beyden hendenn an dein Brust vnd Spring mit dem Rechten fus hinter sein linken vnd wurff In vber das knye auß dem fus |

Hie merckt die Ringen Item greifft er dich oben an mitt ringen und will dich mitt sterck zu° im rucken oder von im stossen So schlag den rechten arm aussen über sein lincken vorm bei seiner hand vnnd truck den mitt baiden henden an dein brüst und spring mitt dem rechten fuss hinter seine lincken und wirf ihn uber das Knie aus dem fuss. |

||||||||

[20] Item: If he grips you on with wrestling and he holds to you then not firmly, then hold his right hand with your right and pull him from you with the left hold him by the elbow and step with the left foot to his right, And pull in this way over it or throw him by the chest off with the arm and break him then this way. |

[20] Cast over the leg in front, and break the arm when he seizes you above but doesn't grip firmly. Then grab his right hand with your right, draw him to you with your left hand and grab his elbow. Step with your left foot in front of his right and pull him over that. Or fall with your breast onto his arm and break it so. |

[20] |

Item grifft er dich an mitt ringen vñ halt er dich dann nitt fast vast So begrÿff sin rechte hand mitt dine~ rechten vñ ruck in zu° dir mitt der lincken begrÿff im den elnbogen vñ schrÿtt mitt de~ lincken fu°ß für sinen rechten Vñ ruck in also darüber Oder fall im mitt der brust vff den arm vñ brich im den also It~ grÿff mitt der lincken hand sin lincke vorne~ bÿ der hand vñ ruck in zu° dir vñ schlach din rechte~ arm mitt störck über sin lincken In das glenck der armbu~ge vnd brich mitt der lincke hannd sin lincke v~ber sin rechte~ vnd spring |

Item greiff er dich an mit ringenn helt er dich den nit fast So begreiff sein Rechte hand mit deyner Rechtenn vnd Ruck In zw dir mit der linkenn greiff Im den Elebogenn vnd Schreytt mit dem linken fus fur seynen Rechten vnd Ruck In also daruber vnnd vall Im mit der prust auff den arm vnd brich Im denn also |

Item greift er dich an mit ringen, helt er dich dem nit fast so begreif sein rechte handt mitt [106r] deiner Rechtenn, vnnd ruck in tzu dir mit der lincken begreif im denn Elnpogenn, vnnd schreit mit dem linckenn fus für, seinenn Rechtenn, vnnd ruck in also daruber, oder fal im mit der prust auff denn arm, vnd brich im denn also. Item begreif mit der linckenn handt sein lincken, vorn bey der hanndt, vnnd ruck in tzu dir, vnnd schlag den Rechtenn arm mit sterck vber seinenn lincken, in das gelenck der armpug, vnnd prich mit der linc[k]enn handt sein linckenn vber dein Rechtenn, vnnd spring mit dem Rechten fus hinter sein Rechtenn vnd wirf in also daruber. |

||||||||

[21] Item: Hold with the left hand his left forward by the hand and pull him to you, and hit your right arm with strength over his left in this bend the arm breaking and break with the left hand his left over his right and spring with the right foot behind his right and throw him from there, etc. |

[21] Grip his left hand with your left hand, just above the hand, and tear him to you. Strike your right arm strongly over his left arm (in the bend) and break it over your right using your left. Spring with your right foot behind his right and throw him over that. |

[21] |

[96r] mitt dem rechte~ fu°ß hinde~ sinen rechten vñ wirff in also darüber etc~ |

Item begreifft mit der linkenn hand sein linken forn pey der hand vnd Ruck In zw dir vnd Schlag den Rechten arm mit sterck vber seynen linken In das glenck der armpug vnnd [p]rich mit der linkenn vber den Rechten vnd Spring mitt dem Rechten fus hinter sein Rechten vnd wurff In als das vber |

Item fert er dir mit dem linckenn arm, vnnter deinenn Rechtenn durch vmb denn leib, so schlag in mit dem rechtenn arm starck vonn obenn nider, auswendig in das gelenck seins lincken elnpogens vnnd wend dich damit vonn im. |

||||||||

[22] Item: If he goes with the left arm beneath your right through, around your body, then hit him with the right arm strong from above below outside his join of his left elbow, and turn with it from him. |

[22] When he drives through under your right arm with his left arm and wants to catch you around the body, then strike with your right arm strongly from above and outside into his left elbow joint and turn away from him. |

[22] |

Item fört er dir mitt de~ lincken arm vnde~ dinen rechten durch vmb din lÿbe So schlach in mitt dem rechten arm starck von oben nÿde~ vsswendig in das glenck sins lincken elbog elnbogens vñ wend dich do mitt von Im ~ ~~ |

Item fertt er dir mit deynem linkenn arm vnter dem Rechtenn durch vmb den leib So schlag In mit dem rechtenn arm starck von oben nyder außwendig an das glenck seins linken elpogens vnd wend dich da mit von Im |

Item wenn er dich fast bey denn armen, vnnd er dich wider, stet er denn gestrackt mit dem fus denn er hatt furgesetzt, So stos in mitt dem |

||||||||

[23] When he has you gathered in his arms and you also have him in the same way, and he stands with a straight leg. Then stamp against his straight leg, so you break his leg. |

[23] |

Item wann er dich fasst bÿ den armen vñ du in wider / stat er dañ gestrackts mitt dem fu°ß So stoß in vff daß selbig knÿ So brichst im den fu°ß ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ |

Item wen er dich fast bey den armen vnd er dich wider Stett er den Starck gestrackt mit dem fus den er hatt fur [110v] gesetzt So stoß In mit dem fus auff das selbig knye So prichstu Ime den fus |

[106v] fus, auff dasselbige knie, so brichstu im den fus. |

|||||||||

[24] Item: You can also with the knee or with the foot hit him to the testicles, when he is aware, however, you should that foresee that he to you by the foot do not hold you, etc. |

[24] You will also thrust with the knee or foot into the testicles. But be aware that he does not catch your leg. |

[24] |

Item du magst im och mitt dem knÿ ode~ mitt dem fu°ß zu° den gemächten stossen / wenn es dir eben ist Aber du solt dich für sechen daß er dich bÿ dem fu°sse nitt begrÿffe etc |

Item dw magst In auch mit dem knye oder mit dem fus zw dem gemecht stossenn wen es dir Ebenn Ist Oder sich dich fur das er dich bey dem fus begreifft |

Item du magst im auch mit dem knie, oder mit dem fus zu dem gemecht stossenn wenn es dir ebenn ist, Oder sihe dich fur, das er dich bey dem fus nicht begreiffe. |

||||||||

[25] Item: When he after you grips with open hands or with outstretched fingers, then wait if that in one finger like to grip and breaking it form above and take him with it out of the arena. Also you win over him with the side and gain even more other great advantage. |

[25] When he approaches you with an open hand or outstretched fingers, then try to seize a finger. Break it above, then you'll lead him to the edge of the arena, also weaken him on this side and win ever more advantage. |

[25] |

[96v] Item wann er nach dir grÿfft mitt offen henden oder mitt gerackten fingern So wart ob du im ainen finger begrüffen mügst Vñ brüch im den übersich Vnd für in domitt zu° dem kraÿß ~ ~~ Auch gewinst du Im do mitt die sÿtten an vñ sunst vill ander grosser vortail ~ Der text võ aine~ lere Item aller lere / Glosa Daß ist daß du mitt allen drÿ wörn die zu° dem kampff gehörn allweg mitt dem ort zu° den blossen stechen solt die dir vorgenant sind / vnd sunst nicht / anders es bringt dir schaden etc~~ ~ |

Item wen er nach dir greifft mit offen henden oder mit gerackten vingern So wart ob dw Im ein vinger begreiffenn ma[g]st vnd prich Im den vbersich vnd fur In da mit In den K[r]eiß auch gewinstu In damit die seytten an vnd sunst vil groß vorteill |

Item wenn er nach dir greift mit offen hendenn oder mit geräcktenn fingernn, So wart ob du im ein finger begreiffenn magst, vnnd prich im denn vbersich vnnd fur in damit tzu dem krais auch gewinstu in damit die seittenn ann, vnnd sonnst vil groß vortail. Das ist der Text von einer lere. Item alle lere, Glosa. Merck das ist das du mit allenn trewenn werenn, die zu dem kampf gehornn, alweg mit dem ort zu denn ploßenn stechenn, solt, die dir vorgenant sein, vnnd sonnst nit oder es bringt dir schadenn. |

||||||||

[26] The text about a lesson

Explanation: That is that you with all three weapons that wear to the battle, to go all the way with the point to the openings should stab with the forth mentioned, and if otherwise can not, you another bring to damage, etc. |

[26] |

[26] |

|

Das ist der text vor [!] einer lere Item aller lere Glosa merck das Ist das du mit allen treuen weren die zw dem kamppff keren alweg mit dem ortt zw denn plosen Stechenn soltt die dir vorgenant sein vnd sust nit oder es pringt dir schaden |

Das ist der Text wie man sol fechten mit dem schwert gegen dem schwert. |

||||||||

[27] The text how one should fence with the sword against sword in battle

Explanation: That is if they both the spear have not choose and should fence with the sword, then you should before all wrestling note and know the the four guards with the short sword, and therefore stab him all the way to the high opening, if he then stabs you with the same one or bind you in the sword, then you should in the hand note if he is hard or weak on sword, And when you have found out, then use the strength against him that you here after written will see. |

[27] The serious fight sword vs sword

When both javelins have been thrown and the sword fight begins, then you should before all things pay attention to the four guards with the half sword. From them stab always to his upper opening. If he then jabs or binds with your sword. Then your should immediately notice if he is hard or soft at the sword. And when you have noted that, then use the strong against him, as is described in the following. |

[27] |

[97r] Der text wie man soll fecht~ Im schwert gegen schwert zu° kampff ~~ Wo man von schaiden / Glosa Daß ist öb sÿ baidde die sper verschossen hetteñ vnd solten fechten vechten mitt den schwertern So salt du vor allen dingen mörcken vñ wissen daß die vier hu°ten mitt dem kurczen schwert / vnd daruß stich im allweg zu° der obern blöß Sticht er dañ mitt dir glich ein ode~ bindt dir an dz schwert So salt du zu° hand mercken ob er hert oder waich am schwert ist Vñ wenn du enpfunnden hau~st So trÿb die [97v] störck gegen im die du hernach geschriben wirst sechen ~~~ :· |

Das Ist der text wie man soll vechten mit dem Schwertt gegen dem Schwertt Wo man von scheyden Glosa Das ist ob wir beyde die Sper verschossenn habend vnd wollen vechten mit den Schwerten So soltu vor allen dingen wissenn die vier huten mit dem kurtzen Schwert vnd darauß stich Im alwegenn zw den obern bloeß Sticht er den mit dir gleich ein oder bind dir an das Schwert so soltu zw hand merckenn ob er hert oder weich am [111r] Schwertt Ist vnd wen dw das Empffunden hast So treib die Stuck gegen Ime die gegen der weich oder gegen der hert gehorenn |

[107r] Wo mann vonn schaidenn, Glosa, das ist ob wir beide die Sper verschossenn hettenn, vnnd soltenn fechtenn mit denn schwertten so soltu vor allenn dingenn wissenn die vier huttenn mit dem kurtzenn schwert, vnd daraus stich im alwegen zu der obernn plos, Sticht er denn mit dir gleich ein oder pint dir an das schwert, so soltu zu hanndt merckenn, ob er hert oder waich am schwert ist, vnnd wen du das empfundenn hast, so treib die stuck gegenn im, die gegenn der waich oder gegen der hert gehornn. |

||||||||

[28] The first guard in the half sword Item: Hold your sword with the right hand by the handle and with the left hold middle in the blade and hold it near your right side over your head and let the point lower hang, to the man, against the face, etc. |

[28] The first guard from the half sword. Holding your sword with the right hand on the grip and the left in the middle of your sword, keeping it on your right side above your head and let the point hang down towards his face. |

[28] |

Die erst hu°t In dem halben schwert ~~ Item halt din schwert mitt de~ rechten hand bÿ der händhäbe vñ mitt de~ lincken grÿff mitten in die clingen vñ halt es neben dine~ rechten sÿtten über din haüpt vñ laß den ort vndersich hang~ dem man gegen dem gesicht etc |

Hie merck die Erst hutt mit dem halben Schwertt Item halt dein Schwertt mit der Rechten hand pey der hand hab vnd mit der linkenn greiff mittenn In die klingenn vnd halt es nebenn deyner Rechten seittenn vber dein haubt vnd los den ortt vntersich hangenn dem man gegenn dem gesicht |

Hie merck die erst hut mit dem halbenn schwert. Item halt dein schwert mit der rechtenn handt bey der handhab, vnnd mit der linckenn greif mittenn in die clingenn, vnnd halt es neben deiner Rechtenn seittenn, vber dein haupt, vnd las denn ort [107v] vnntersich hangenn, dem mã gegen dem gesicht. |

||||||||

[29] Item: If he stands then against you in the lower guard and wish to stab you underneath then stab through from above to below between the sword and his forth-placed hand and press the pommel downward and wind in the point on sword beneath through against his right side and set it in. |

[29] If he then stands in the lower guard and wants to stab you underneath, then stab down from above between the sword and his closest hand. Press the pommel underneath, wind the point on his sword under and through to his right side and set the point on him. |

[29] |

Item stätt er dañ gegen dir In der vndern hu°t Vnd will dir vnden zu° stechen So stich durch võ oben nider zwischen dem schwert vñ siner vorgesäczner hand Vñ truck den knopff vndersich vnd wind im den ort am schwert vnde~ durch gege~ sine~ recht~ sÿtten vñ secz im an ~~~~ ~ ~ ~ :·~ |

Item merck Stett er dan gegen dir In der vndern hutt vnd will dir vnnden zw Stechen von oben nyder zwyschen dem Schwertt vnd seyner vorgesatzten handt vnnd truck den knopff vntersich vnd wind Im den ortt vnden am Schwertt durch gegen seyner Rechten seÿtten vnd setz Im ann |

Item merck stet er dann gegenn dir in der vntern hut, vnnd wil dir vntenn tzu stechenn vonn obenn nider tzwischenn dem schwert, vnd seiner vorgesatztenn handt, vnnd truck denn knopf vntersich, vnnd wind im denn ort am schwert vntenn durch gegenn seiner Rechtenn seittenn, vnd setz im an. |

||||||||

[30] Stab him in the face from the first guard. If he fends that off then jerk or go through with the point to the other side, just as before. When you have set the point against him then put your sword under your right armpit with the hilt on your breast and push him from you. |

[30] |

[98r] Item stich Im vß der ersten hu°t zu° dem gesicht wert ers So zuck oder ge du~rch mitt dem stich alß vor zu° der anderen sÿtten Vñ weñ du Im hau~st angeseczt So schlach din schwert vnde~ din rechte v°chsen mitt demgehu~ltz an die brüst vñ dring in also von dir hin ~ |

Item Stich Im aus der Ersten hutt zw dem gesicht wert ers weitt So zuck oder gee durch mit Stich als vor zw der andern seytten vnd wen dw Im hast angesetzt So Schlag dein Schwertt vnter dein recht vchssenn mit dem gehultz an die prust vnd dring In also von dir hin |

Item stich im aus der erstenn hut zu dem gesichtt, wert ers weit so tzuck, so tzuck [!] oder gehe durch mit dem stich als vor, zu der andernn seittenn vnnd wenn du im hast angesetzt, so schlag dein schwert vnter dein Rechte vchsenn, mit dem gehiltz an die brust, vnd dring in also von dir hin. |

|||||||||

[31] Second assault from the first guard Stab him in the face from the first guard, just as before. If he puts the sword in front of him with the left hand in front and keeps the point in front of the face, and sets it around to you. Then grip with the left hand the point of his sword and hold it tight. With your right hand stab him hard in the face. |

[31] |

Item mörck ain aid anders Stich im zu° alß vor / verseczt er vor siner lincken hannd mitt dem schwert vñ blipt dir mitt dem ort vor dem [98v] gesicht vñ will diner dir anseczen so begrÿff mitt de~ lincken hand sÿn schwert bÿ dem ort vnd halt daß föst vñ mitt de~ kerechten hand stich im kröffticlichen zu° den gemächten |

Item merck ein anders Stich Im zw als vor versetzt er vonn seiner linkenn hand mit dem Schwertt vnnd pleibt dir mit dem ortt vor dem gesicht vnd will dir ansetzenn So greiff mit der linken hand sein Schwertt bey dem ortt vnd halt es vest vnd mit dem Rechten Stich Im krefftiglich zw dem gemecht |

Item merck ein annders, Stich im tzu als vor, versetzt er vor seiner linckenn handt mit dem schwert vnnd pleibt dir mit dem ort vor dem gesicht, vnd wil dir ansetzenn, so begreif mit der linckenn hanndt sein schwert bey dem ortt, vnnd halt das [108r] fest, vnnd mit der Rechtenn stich im kreftiglichenn tzu dem gemecht |

|||||||||

[32] If he then yanks his sword firmly to himself and you will that out the hands follow, then release the sword, go to the upper wrestling, then, if he gives himself an opening then hold his sword quickly with the left hand against the middle of the blade and follow him after etc. |

[32] If he then wants to jerk on the sword and pull it from your hand, then suddenly let it go, so he gives you an opening. Straight away grip your sword again in the middle with your left hand and follow straight away to him. |

[32] |

Zuckt er dann sÿn schwerst vast an sich vñ will dir daß vß der hand rissen So laß im dz schert / Vrbringe faren So gibt er sich bloß So begriff sin schwert bald mitt de~ lincken hand wider mitten in der clingen vñ folg im nach etc |

zuckt er dan sein Schwertt vast an sich vnnd will dir das auß der hand Reyssenn So las Im das Schwertt [111v] vrbering farn so gibt er sich plos So begreiff dein Schwertt bald mit der linken hand wider mitten In der clingen vnd volge Im nach |

tzuckt er dann sein schwert fast ann sich, vnnd wil dir das aus der handt reissenn so las im das schwert vrbering farn, so gibt er sich plos, so begreif dein schwert bald mit der lincken hanndt, wider mittenn in der clingenn, vnnd volge im nach. |

||||||||

[33] Item another If you took his sword and he to yours, then throw his sword to the left hand and hold yours with it against middle in the blade and rotate the point outside over his left hand and set it in. |

[33] Second defence from the first guard If you grab his sword and he grabs yours, then let go of his sword and grip yours again in the middle with your left hand, wind the point out and over his left hand and set the point at him. |

[33] |

Item ain anders Begrÿffstu sin schwert vñ er das din So [99r] wirff sin schwert vß de~ lincken hand Vnd do mitt begrÿff daß din wide~ mitten inder clingen vnd wind im den ort ausen über sin lincke hand vñ secz im an ~ ~ |

Item Aber ein anders begreiffstu sein Schwertt… |

Item aber ein anders, begreifstu sein schwert, vnnd er das dein, so wirf sein schwert aus der linckenn hanndt, vnd begreif das dein damit wider mittenn in der clingenn, vnnd wind im denn ort außenn vber sein lincke handt, vnd setz im ann. |

||||||||

[34] Item: Or throw in your sword to his foot and hold his left hand with your left and conduct the arm break or otherwise other wrestling, etc. |

[34] Or throw the sword in front of his feet. Grab his left hand with your left hand and set an arm break, or some other wrestle on. |

[34] |

Item oder wirff im din schwertt für die füsß vñ begriff sin lincke hand mit dine~ lincken vñ trÿb den arm bruch oder sunst ander Ringen etc |

Item oder wirf im dein schwert fur sein fus, vnnd begreif sein lincke handt mit deiner lincken, vnnd treib denn armpruch, oder sonnst ander ringenn. |

|||||||||

[35] Item: When you are in the high guard to stab, if he size you then with the left hand in your sword between your both hands, then go in with the pommel winding out or winding in, over his left hand and tear[20] off to your right side and set it in, also you can off the high guard with the pommel well hit when it is precisely to you. |

[35] When you stab him to the face from the upper guard. And he with his left hand seizes your sword between your hands, then drives through with his pommel outside or inside above his left hand. Tear to your right side and set the point on him. When you do, you'll also strike him with the pommel from the upper guard. |

[35] |

Item wann du Im vß der obern hu°t zu° stichst fölt er dir dann mitt der lincken hannd in din schwert zwischen dine~ baid~ henden So far im mitt dem [99v] kr knopff vsswendig oder Inwendig über sin lincke hannd vñ reÿß vff din rerchte sÿtten vnd secz im an au~ch magst du vsß der obern hu°t mitt dem knopff wol schlachen wann es dir eben ist ~~ Die ander hu°tt mitt dem kurczen schwert zu° kampff Merck halt din schwert mitt baiden henden vnd halt daß vndersich zu° dine~ rechten sÿtten mitt der handhäben neben dine~ rechten knÿ vñ dz din lincker fu°ß vor stee vñ din ort dem man gege~ din ge gesicht ~ ~ ~ : ~ |

Item wenn du im aus der obernn hut zu stichst felt er dir dann mit der linckenn handt in dein schwert, zwischenn deinenn beidenn hennden, so far im mit dem knopf auswendig oder inwendig, vber sein [108v] lincke hanndt, vnnd reiß auf dein Rechte seittenn, vnnd setz im ann, auch magstu aus der obernn hut mit dem knopf wol schlagen wẽ es dir ebẽ ist. Das ist die ander hut mit dem kurtzen schwert zu kampff. Merck halt dein schwert mit baiden hendenn, vnnd halt es vntersich, tzu deiner Rechten seittenn, mit der handhab nebenn deinem Rechtenn knie vnnd das dein lincker fus vor stehe, vnnd der ort dem man gegen dem gesicht. |

|||||||||

[36] The second guard with the short sword to battle Note, hold your sword with both hands and hold it underneath, towards your right side with the handle near your right knee and that your left foot stands forward and your point to the man goes against the face. |

[36] The second guard with the half sword Hold your sword with both hands, down to your right side, with the grip next to your knee. Your left foot will stand forward and the point shall be directed at the face of your opponent. |

[36] |

|

Item wenn du also stehest, in der hut, stehet er den gegenn dir in der obernn hut, vnnd wil dir obenn ansetzenn, So stich du vor, vnd setz im den ort, vnter sein lincke vchsenn in die plos, oder stich im tzu seiner vorgesatzenn handt, zu der plos des teners. Oder stich im vber seiner vorgesatzten handt durch, vnnd dem schwert, vnd truck denn knopf, gegenn der erdenn, vnd setz im an zu der andern seitten. |

|||||||||

[37] Item: When you this way stand in the guard, if he stands then against you in the high guard and you will from above in-place, then stab before and set the point to his forth-placed hand to the opening on the palm, or stab him over his forth-placed hand through and your sword, and press your pommel against the earth and set it in to the other side. |

[37] When you stand in this guard and he faces you in the upper guard and wants to set it in from above.[21] Then stab him first and set the point on his forward hand in the opening of the flat of the hand. Or stab through over his forward hand, press down with your pommel and set him to the other side. |

[37] |

[100r] It~ wenn du also steest In de~ hu°t Stet er dann gegen dir in der obern hu°t vñ will dir oben anseczen So stich du vor vñ secz im den ort für sin fürgeseczte hand zu° der blöß des teners v oder stich im über sin vorgeseczte~ hand durch vñ vnd din schwert vñ truck dine~ knopff gegen der erden vnd secz im an zu° der andern sÿtten ~ |

|

|||||||||

[38] Item: When he stabs to you from above, then hold with the left hand his sword in front of his left side and with the right set your sword with the hilt in your chest and set it in, etc. |

[38] When he jabs at you from above, grab his sword with your left hand in front of his left hand, place the hilt on your breast and set the point against him. |

[38] |

Item wañ er dir oben zu° sticht So grÿffe mitt der lincken hand sin schwert vor sine~ lincken vñ mitt der rechten secz I din schwert mitt dem gehülcz [100v] an din brüst vnnd secz im an etc |

[109r] Item wenn er dir obenn tzu sticht, so begreif mitt der linckenn handt sein schwert vor seiner lincken vnnd mit der Rechtenn setz dein schwert mit dem gehiltz an dein prust, vnd setz im ann. |

|||||||||

[39] A break against the setting through When you stab him from the lower guard and he stabs you from the upper guard between your forward hand and your sword and pushes his pommel down. Then go in to the upper guard and set on him at once. |

[39] |

Ain bruch wide~ daß durchseczen Item wañ du im vß der vnder hu°t zu° stichst Stichts er dir vß der obern hu°t durch zwischen dine~ vorgesäczteñ hand vnd dem schwert So mörck die wil er den knopff nide~ truckt / so far vff zu° der obern hu°t vñ secz im an ~~ |

Item das ist ein pruch, wider das durchstechen, wen du im aus der vnternn hut zu stichst, Sticht er dir aus der obernn hut durch, zwischenn deiner vorgesatztenn handt vnnd dem schwert, so merck dieweil er denn knopf nider truckt, so far auf, Inn die obernn hut, vnnd setz im ann. |

||||||||||

[40] Item: If you want to stab from the lower guard, if he then goes through with the pommel beneath your sword and will with it out-place, then hold him with the point strong in front of the face, and press him to his right hand this way underneath, if he will wind through and set it in. |

[40] |

Item stich im zu° vß der vndern hu°t fert er dann durch mitt dem knopff vnde~ din schwert vnd will domitt abseczen So blÿb im mitt dem ort starck vor dem gesicht vnd truck Im sin gerechte hand also vnder [122r] die wil wÿl er durch windt vñ secz im an ~~ ~~ |

|

Item stich im tzu, aus der vnternn hut, fertt er dan durch mit dem knopf, vnter dem schwert, vnnd wil damit absetzenn oder reissenn, so bleib im mit dem ort starck vor dem gesicht, vnd truck im sein Rechte hanndt also vntersich, dieweil er durchwindet, vnd setz im an… |

|||||||||

[41] Item: If you want to stab strong from the lower guard to the face, if he stabs then towards you from the same one, then hold his sword in the middle with your with left with turned hand and hold they both to together and go with the pommel under through his sword and with the right arm pull from above off to your right side so you take his sword. |

[41] |

[41] |

Item stich im starck vß der vndern hu°t zu° dem gesicht Sticht er dann mitt dir glÿch ÿn So begrÿff sin schwert in der mitte zu° dem dine~ mitt lincker ver korter hand vnd halt sÿ baÿde föst zu° samen vnd far mitt dem knopff vnden durch sin schwert vnd mitt dem rechten arm rück ubersich vff din rechten sÿtten so nÿmpst du im sÿn schwert ~ ~~ |

Item Stich Im Starck auß der vntern hutt zwm gesicht Sticht er dan mit dir gleich ein / so begreiff sein Schwertt In der mitt zw dem deynen mit linker verkerter hand vnd halt sie bede vest zw samen vnd far mit dem knopff vnder durch sein Schwertt vnd mit dem Rechten arm Ruck versich [!] auff dein Rechte seyttenn So nimst Im das Schwertt |

[99r] …Item stich im starck aus der vntern hut zum gesicht, sticht er dann mit dir geleich ein, so begreif sein schwert In der mit zu dem deinen mit lincke[r] vekerter hanndt, vnnd halt sie baide fest tzusamen vnnd far mit dem knopf vntenn durch sein schwert, vnnd mit dem Rechtenn arm Ruck vber sich auf dein Rechte seiten, so nimbst im das schwert. |

||||||||

[42] Item this way break that When you are with someone that with his left hand hold your sword in the middle towards him and you will that chase-out, then note when he your sword takes to the left hand, towards his, then go off in the high guard and set it in. |

[42] |

[42] |

Item also brich daß Wenn dir aine~ mitt sine~ lincken hand begrÿfft din schwert In der [122v] mitten zu° dem sinen Vñ will dir daß vsßrissen So mörck die wil er dir daß schwert fasst in die lincken hand zu° dem sine~ So far vff in die obern hu°t vnd secz im an ~ ~~ |

Item Also prich das wen dir eyner mit seyner linken hand begreifft dein Schwertt In der mitt zw seynem vnd will dir das außreissenn So merck wen er dein Schwertt vast In die linck hand zw dem seynen so far auff In die ober hutt vnd setz Im ann |

Item also prich das, wenn dir einer mit seiner linckenn hanndt begreift dein schwert in der mitt, tzu dem seinenn vnd wil dir das außrayßenn, So merck dieweil er dein schwert fast in der linck[en] handt, zu dem seinen, so far auf in die oberhut vnnd setz im ann. |

||||||||

[43] Item: If you stab him from the lower guard in, agile to the face, if he mis-places then yank and stab him from outside to the face, if he mis-places further, then punch him with the pommel, in front over his right shoulder around the neck and spring with the right foot behind his left and pull in with the pommel over the leg so he falls, etc. |

[43] |

[43] |

Item stich im vsß der vndern hu°t in wendig zu° dem gesicht / verseczt er So zuch zuck vñ schu stich im vß zu° dem gesicht / verseczt er fürbaß So far im mitt dem knopff vornen über sin rechte achseln vmb den halß vñ spring mitt dem rechten fu°ß hinder sin lincken vñ ruck in mitt dem knopff über daß bain so fölt er etc~ |

Item Stich Im auß der vndern hutt In wendig zwm gesicht versetzt er so zuck vnnd Stich Im aussenn zwm gesicht versetzt er furpas so far Im mit dem knopff vorn vber sein rechte achsseln vmb den hals vnd Spring mit deim Rechtenn fus hinter sein linkenn vnd Ruck In mit dem knopff vber das pein So felt er |

Item stich im aus der vntern hut inwendig tzum gesicht, versetzt er so tzuck vnnd stich im außenn tzum gesicht, versetzt er furbas, so far im mit dem knopf, vorn vber sein Rechte achseln vmb den hals vnd spring mit dem Rechtenn fus hinter sein lincken, vnd ruck in mit dem knopf vber das [99v] pain so felt er. |

||||||||

[44] Item break that this way Whoever that to you with the pommel forward, around the neck goes and with the right foot spring behind your left, then grab his "right arm with your"[24] left hand and press the firmly on his[25] chest, and turn from him to the right side and take him off your left hip and throw him away from to you, etc. |

[44] |

[44] |

[125r] Item also brich daß wer dir mitt dem knopff vorne~ vmb den halß fört vñ mitt dem rechte~ fu°ß springt hinde~ din lincken So begrÿff im sin lincke hand vñ truck die fast an die bru~st / vnd wend dich von im an die rechte~ sÿtten vñ fass in vff din lincke hu~ffe vnd wirff in für dich etc~ |

Item Also prich das wer dir mit dem knopff forn vmb dein hals fert vnd mit dem Rechten fus Springt hinter den linken [112r] So greiff sein rechtenn arm mit deyner linkenn handt vnd truck den vast an dein prust vnd wend dich von Im auf dein prust rechte seitten vnd faß In auff dein Rechte hufft vnd wurff In fur dich |

Item also prich das. wer dir mit dem knopf, vornn vmb denn hals fert, vnnd mit dem Rechten fus spri~gt hinter dein linckenn, So begreif sein Rechten arm mit deiner lincken handt, vnd truck den fast an dein brust, vnnd wend dich von im auf dein Rechte seittenn, vnd fas in auf dein lincke huf, vnd wirf in fur dich. |

||||||||

[45] |

[45] |

Item och magstu du im vß der vndern hu°t wol zu° schlachen weñ es dir eben ist ~~ |

Item Auch magstü In auß der vnntern hutt auch zw Schlagenn mit dem knopff wen es dir Eben Ist |

Item auch magstu im aus der vnternn hut auch tzuschlagenn mit dem knopf, wen es dir ebenn ist. |

|||||||||

[46] The third guard with the short sword/ this is the third guard with the short sword to battle Item: Hold your sword with both hands as before written is, and hold it over your left knee And therefore break him all his techniques with mis-placement, etc. |

[46] |

[46] |

Die dritt hu°tt mitt dem kurczen schwert Item halt din schwert mitt baÿden henden alß vor geschriben stät vñ leg es über [125v] din linckes knÿ Vñ daruff brich im alle sine stuck mitt verseczen etc |

Das ist die dritt hutt mit dem kurtzenn Schwertt zw kempffenn Halt dein Schwertt mitt beiden henndenn als vorgestriben [!] steet vnd leg es vber dein linkes knye vnd daraüß prich Im alle sein Stuck mit versetzenn |

Das ist die drit hut mit dem kurtzen schwert zu kempffenn. Halt dein schwert mit beiden henden, als vorgeschribenn stet, vnnd leg es vber dein linckes knie vnd daraus prich im al sein stuck mit versetzen. |

||||||||

[47] Item: If he stabs you from the high guard to the face and place the stab out with the sword in front of your left hand against his right side, then go off with the sword in the high guard and set it in. |

[47] |

[47] |

Item sticht er dir vß der obern hu°t zu° dem gesicht vñ seczt den stich abe mitt dem schwert vor dine~ lincken hand gege~ sine~ rechten sÿtten So farfar vff mitt dem schwert in die obern hu°t vnd secz im an ~~ |

Item Sticht er dir aus der obern hutt zwm gesicht vnd setzt den Stich ab mit dem Schwertt vor deyner linken handt gegenn seyner rechten seytten vnd far auff In die obern hutt vnd setz Im an |

Item sticht er dir aus der obernn hut zum gesicht vnnd setzt denn stich ab mit dem schwert vor deiner lincken handt, gegen seiner Rechten seitenn vnd far auf in die oberhut, vnd setz im an. |

||||||||

[48] |

[48] |

Item oder far vff mitt de~ schwert vñ versecz den obern stich zwischen dine~ baiden henden vñ far im mitt dem knopff über sin vor geseczte hand vñ ruck domitt vndersich vñ secz im an ~~ |

Item oder far auff mit dem Schwertt vnd versetz den obern stich zwischen deinen beyden hendenn vnd far Im mitt dem knopff vber sein versatzte hand vnd Ruck da mit vntersich vnd setz Im ann |

[100r] Item oder far auf mit dem schwert, vnd setz denn obernstich zwischenn deinen baiden henden, vnd far im mit dem knopf… |

|||||||||

[49] Item: Go under through with the pommel over his forth-placed hand and pull with it underneath and set it in, also you can change through underneath with the pommel and in the stab out-place. |

[49] |

[49] |