|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Fiore de'i Liberi/Mounted Fencing

Illustrations |

Illustrations |

Novati Translation |

Paris Translation |

Morgan Transcription (1400s) |

Getty Transcription (1400s) |

Pisani Dossi Transcription (1409) |

Paris Transcription (1420s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [No Image] | [1] I am a noble weapon, Lance by name: |

Here begins the art of the noble weapon called Lance; in the beginning of battle, on horse and on foot, is its use. And whoever watches it with its dashing pennant should be frightened with great dread. And it makes great thrusts which are dangerously strong, and with a single one it can give death. And if in the first blow it makes its due, then axe, sword, and dagger will all be upset.[1] |

[9r] Aqui comenza l'arte de nobele arma chiamada lanza principio de bataglia a cavallo, e a pe e sua usanza. E chi la guarda cum so bello penone e polito de grande paura doventa smarido. E la fa grande punte, e pericolose forte. E cum una sola po dar la morte. E si lo primo colpo el suo debito ella fara, Azza spada e daga de impazo tute le cavara. |

[29a-a] Io son la nobelle arma per nome lança |

|||

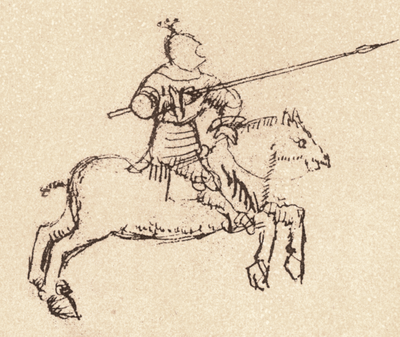

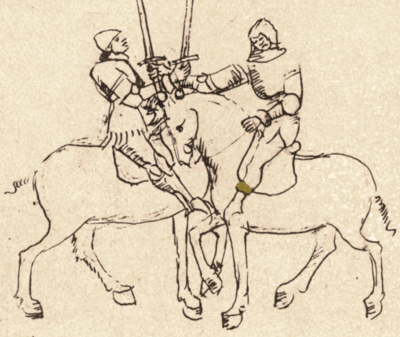

[2] I carry my lance in the Boar's Tusk: I carry my lance in the guard Boar’s Tooth, because I am well-armoured and have a shorter lance than my opponent. My intention is to beat his lance offline as I raise mine diagonally. And this will result in our lances crossing each other at about an arm’s length from the point. My lance however will then run into his body, while his will pass offline far from me. And that is how this is done. (This text applies to the drawing on the right.)[2] |

[Now] I bear [my] spear, but brandishing with the Boar’s Tooth I carry my lance in the Stance of the Wild Boar's Tusk because I am well-armored and have a shorter lance than my companion. And so I make my strategy to beat his lance out of the way (so that it is off to one side and not high), and thus will I strike with my lance to his and enter with an arm on my haft, and my lance will run into his person. And his lance will go out of the way far from me, and in such fashion will I do it as is written and depicted here. |

[41r-a] ¶ Io porto mia lanza in posta di dente di cenghiaro per che io son ben armado, e si, o curta lanza piu che lo compagno, e si fazo rasone de rebatter sua lanza fora de strada zoe ala traversa overo in erto. E si firiro cum la mia lanza in la sua, uno brazo in entro cum uno brazo dela mia hasta, E la mia lanza discorrera in la sua persona.[3] E lla sua lanza andara fora di strada lonze de mi e per tal modo faro. |

|||||

|

[3r-b] Io porto mia lanza in posta di dente di zenghiar perche io son bene armado, e si o curta lanza piu che lo compagno. ¶ E si fazo rasone de rebatere la sua lanza fora de strada, zoe ala taiversa[!] e non in erto. E si firiro Cum la mia lanza in la sua uno brazo in entro cum uno brazo dela mia asta. ¶ E la mia lanza discorrera in la sua persona. E lla sua lanza andera fora de strada lonze de mi e per tal modo faro como e dipento e scripto aqui. |

[41r-b] ¶ Questa glosa va al Re di qua. |

[29a-b] Io porto mia lança a'dent de çenchiar |

|||||

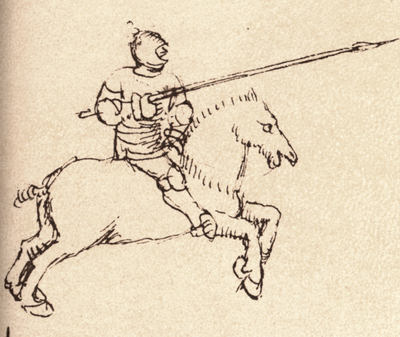

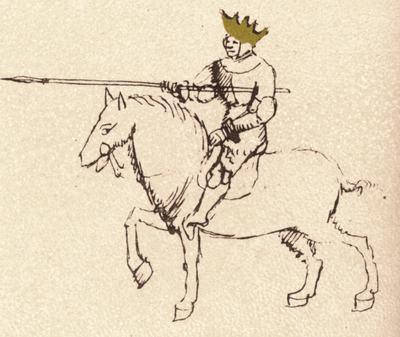

[3] In the Boar's Tusk I carry my lance; This is the counter to the previous play when one rides against another with sharp steel, but one has a shorter lance than the other. When he who has the shorter lance carries it low in the Boar’s Tusk, then he with the longer lance should similarly carry his lance low, as drawn here, so that the short lance cannot beat aside the long lance. |

[41r-c] ¶ Questo si'e lo contrario dello zogho de lanza ch'e denançi che quando uno corre contra l'altro a ferri moladi, e uno a corta lança piu che l'altro. Quando quello che a curta lanza porta la sua lanza bassa in dente di cenghiaro quello che a la lanza longa debia simile mente portarla bassa la sua, per che la curta non possa rebattere la longa per lo modo che qui e depento. |

[29a-c] A dent de cenchiar io porto la mia lança |

|||||

So that you won't have advantage over me with your lance, [In the Getty, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

This is the counter to the play of the lance which came before, that here one runs against the other with sharp iron and he has a shorter lance than the other. When he that has a short lance carries his low in the Boar's Tusk, he that has the long lance should similarly carry it low in the way which is depicted here, so that the short cannot beat the long. |

[3r-d] Aquesto si e lo contrario dello zogo de lanza ch'e denanzi. Che qui uno corre contra l'altro a ferri amoladi, e uno a curta lanza piu che l'altro. ¶ Quando aquello che a curta lanza la porta la sua bassa in dente de zenghiar, Aquello che ala lanza longa debia similmente portarla bassa la sua, ¶ perche la curta non possa rebater la longa per lo modo ch'e aqui dipento. |

[29a-d] Pero che cum tua lança de mi non habii avantaço |

||||

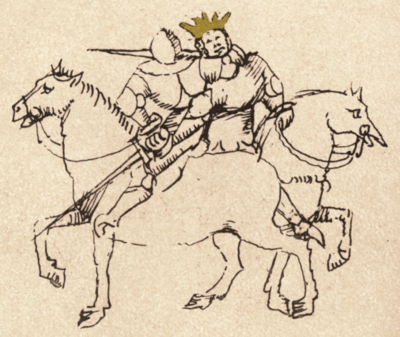

[4] Because of the short lance that I hold, I come in the Stance of the Queen: This is another way to carry your lance when fighting another lance. This Master has a short lance, so he carries it in Guard of the Lady on the left as you can see, so he can beat aside his opponent’s weapon and strike him. |

Behold! I come, holding the lance in the Woman’s [Position] at the chest. This is another way to carry the lance. This Master has a short lance and carries it in the Stance of the Queen on the Left as you can see, to beat and then to strike his companion. |

[3v-b] Aquesto e uno altro portar de lanza. Aquesto magistro a curta lanza, e si la porta in posta de dona la sinistra como voii vedite, per rebater, e ferire lo compagno. |

[41v-b] ¶ Questo e un altro portar de lanza contra lanza. Questo magistro a curta Lanza e si la porta in posta de donna la sinistra como voii vedete, per rebatter a ferir lo compagno. |

[29b-b] Per curta lança che io ho in posta de dona vegno |

[2r-d] ¶ En venio retinens muliebrj pectore telum. | ||

[5] To waste you or your horse, I make this throw: [In the Getty, the Master on the left is missing his crown.] |

If I throw my lance into the chest of your horse, your beat will fail. And as soon as I’ve thrown my lance, I will take up the sword for my defense and with your lance you will not do me offense. |

[3v-c] S’io lanzo mia lanza in lo petto dello tuo cavallo, lo tuo rebatere fallo. E subito lanzada mia lanza la spada pigliro per mia defesa. E cum tua lanza non mi faraii offesa. |

[29b-c] Per guastar ti o tuo cavallo faço questo lançar |

||||

This Master also carries his lance in Guard of the Lady on the left, in order to knock aside the spear his opponent is about to throw at him. Just as he can beat it aside using his lance, so too he could beat it aside using a staff or a short sword. [In the Pisani Dossi, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

Again, this Master carries his lance in the Stance of the Queen on the Left to beat the lance that the companion wants to throw. And that beat which he wants to strike with the lance he could also do with a staff or with a sword—except that if he throws his lance into the chest of my horse, my beat will be turned to failure. [In the Morgan, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

[3v-d] Anchora a questo magistro porta la sua lanza in posta di donna sinistra per rebater la lanza che lo[7] compagno gli vole lanzare. E aquello rebatere che lo vol cum la lanza fare, Aquello cum uno bastone o curta spada far lo poria. Salvo che s'ello buta sua lanza in lo peto delo mio cavallo lo mio rebater tornera fallo. |

[41v-d] ¶ Anchora questo magistro porta la sua lanza in posta de donna la sinistra per rebatter la lanza che lo compagno gli vole lanzare. E quello rebatter ch'ello vole cum la lanza fare, quello cum uno bastone o curta spada far lo poria. |

||||

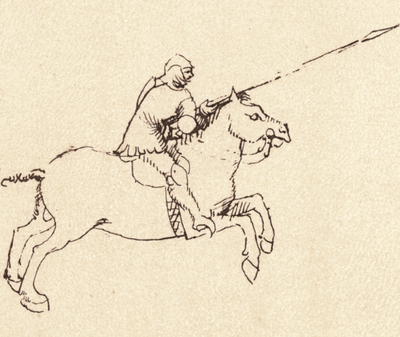

[6] Fleeing, I cannot make any other defense This master who is fleeing is not wearing armor and rides a horse built for speed, and as he flees he constantly throws his lance point behind him so as to strike at his opponent. And if were to turn his horse to the right he could quickly enter into the Boar’s Tusk guard with his lance, or he could take the left side Guard of the Lady, to beat aside his opponent’s weapon and finish him in similar fashion to the first and the third plays of the lance. [In the Pisani Dossi, the Master is missing his crown.] |

Correct in opposition, I would make you strong pains. This Master who flees is not armored and is on a running horse, and he is always throwing thrusts with his lance backward to strike his companion. And if he were to turn to the right side he could easily enter into the Boar's Tusk with his lance or into the Stance of the Queen on the Left, and beat and strike as he could do in the first and third plays of the lance [on foot]. |

[4r-b] Aquesto magistro che fuge non e armado, e si e bene a cavallo corrente, e sempre va butando le punte cum la sua lanza deriedo da si, per ferire lo compagno. E s'ello si voltasse della parte dritta ben poria intrar in dente de zenghiar cum sua lanza, overo in posta di donna la sinistra, e rebater, e ferire como si po fare, in lo primo & in lo terzo zogo de lanza. |

[42r-b] ¶ Questo magistro che fuzi non e armado, e si a bon[8] cavallo corente, e sempre va buttando le punte cum la sua lanza dredo de si per ferire lo compagno. E si ello se voltasse dela parte dritta ben poria intrar in dente di zenghiaro cum sua lanza, overo in posta di donna la sinistra, e rebatter e finire come si po far in lo primo e in lo terzo çogho de lanza. |

[30a-b] Fuçando non posso far altra deffesa |

|||

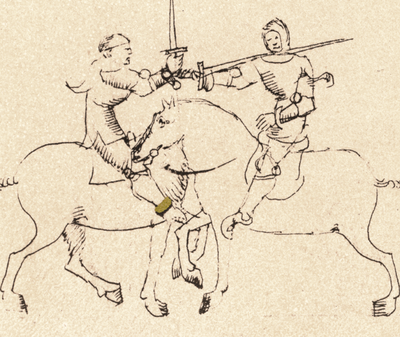

[7] With my sword, I will beat your lance, This method of carrying the sword against the lance is well suited for beating aside your opponent’s lance when you are passing him on his right side. And this guard is effective against all hand held weapons, namely pole axe, staff, sword etc. |

The regal Form of the Woman is suitable, and piercing you This carry of the sword against the lance is very good for beating the lance while riding to the right side of your companion. And this guard is good against all other handheld weapons—that is, against the ax, the staff, the sword, and so forth. [Morgan text accompanies subsequent pairing.] |

[4r-d] Aquesto portar de spada contra lanza e molto fino per rebatere la lanza, cavalcando dela parte dritta delo compagno. E aquesta guardia si e bona contra tute altre arme manuale, zoe contra azza, bastone spada, &c. |

[42r-d] ¶ Questo portar de spada contra lanza e molto fino per rebatter la lança cavalcando dela parte dritta dello compagno. E questa guardia si'e bona contra tutte altre arme manuale, zoe contra Aza, Bastone, spada, & cetera. |

[30b-b] Cum la spada tua lança io rebatero |

|||

[8] I make the counter to your guard, This is the counter to the previous play. This Master attacks with his lance held low in order to strike his opponent’s horse either in the head or the chest, and the opponent will be unable to beat aside such a low attack with his sword. [In the Getty, the Master on the right is missing his crown. In the Pisani Dossi, both Masters are missing their crowns.] |

This is the counter to the play that came before. And this Master with the lance carries it low to strike the horse in the head and in the chest, because his companion cannot reach so low with his sword. |

[4r-c] Aquesto si e lo contrario dello zogho ch'e denanci. Che questo magistro cum la lanza la porta bassa per ferire lo cavalo in la testa, o in lo petto, che lo compagno non po rebater cum la spada tanto basso. |

[42v-a] ¶ Questo si'e contrario del zogho ch'e denanzi che questo magistro cum la lanza la porta bassa per ferir lo cavallo, o in la testa, o in lo petto che lo compagno non po rebatter cum la spada tanto basso. |

[30a-c] Lo contrario dela tua guardia io faço |

|||

This carry of the sword is very fine, and it is called by a name that was said before: I carry my sword in the left Queen's Stance. And if this one comes to me with the lance in rest (to strike me and not my horse), I will beat his lance and I will strike him with my sword without fail. Note that the sword cannot defend below the neck of a horse. [Morgan text accompanies previous pairing.] |

[4v-b] E aquesto portare di spada e molto fino ch'e ditto denanci che se porta contra lanza come e ditto denanci. Che porto la mia spada in posta donna sinistra. E da questo mi vene cum la lanza in resta per ferirmi, e non el cavallo, rebatero la sua lanza, e cum mia spada lo feriro senza fallo che la spada non po defendere basso per lo collo del cavallo. |

||||||

[9] So that you do not beat my lance out of the way, This is another counter of lance versus sword. In this one, the man with the lance couches his lance under his left arm, so that his lance cannot be beaten aside. And in this way he will be able to strike the man with the sword with his lance. |

Again this is another counter of lance against sword. He of the lance sets his lance in rest under his left arm so that his lance cannot be beaten aside. And in this fashion he can strike him of the sword with his lance. [In the Morgan, the Master's opponent is wearing a crown.] |

[4v-d] Anchora e aquesto uno altro contrario de lanza contra spada. Che aquello dela lanza, meti e resta sua lanza sotto lo suo brazo stancho perche non sia rebatuda sua lanza. E per tal modo pora ferir cum sua lanza aquello della spada. |

[42v-d] ¶ Questo e un altro contrario de lanza contra spada, che quello dela lanza metti e resta sua lanza sotto lo suo brazo stancho per che non gli sia rebattuda sua lanza. E per tal modo pora ferir cum sua lança quello della spada. |

[30b-d] Perche tu non rebati mia lança fora destrada |

|||

[10] At mid-lance thus I come, well-enclosed [In the Pisani Dossi, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

Drawing the members close at the same time, I, the harsh one, seize the javelin <I delay the javelin> [In the Paris, the Master on the right is missing his crown.] |

[5r-a] [No text] |

[43r-a] [No text] |

[31a-a] A meça lança io vegno acossi ben asserato |

|||

Here the man with the sword awaits the man with the lance, and he is waiting in the Boar’s Tusk guard. As the man with the lance approaches him, the Master with the sword beats aside the lance to the right side, covering and striking with one turn of the sword. [In the Getty, the Master on the left is missing his crown.] |

This one with the sword awaits him with the lance. He waits in the Boar's Tusk as he with the lance comes, and then the Master with the sword beats his lance away toward the right side. And thus can the Master do with the sword—that is, he can cover in one rotation of the sword. [In the Morgan, the Master on the left is missing his crown.] |

[5r-b] Aquesto cum la spada aspeta aquesto cum la lanza, e si lo aspeta in dente de zenghiare, como aquello cum la lanza gli vene apresso, lo magistro cum la spada rebati sua lanza in fora verso parte dritta. E acosi po far lo magistro cum la spada. ch'ello po covirre[!] in uno voltar de spada. |

[43r-b] ¶ Questo cum la spada spetta questo cum la lanza e si lo spetta cum dente di cenghiaro, Come quello cum la Lanza gli vene apresso, lo magistro cum la spada rebatti sua lanza in fora in verso parte dritta. E chossi po far lo magistro cum la spada, ch'ello po covrir e ferir in un voltar di spada. |

[31a-b] [No text] |

[2v-d] [No text] | ||

[11] So that you cannot cross your sword with my [weapon], This is the counter to the preceding play of lance versus sword. Here the man with the lance strikes his opponent’s (the man with the sword) horse in the head, because he cannot beat aside the lance with his sword since it is too low. [In the Pisani Dossi, the Master is missing his crown.] |

This is the counter of the play of the lance and the sword that came before: that is, that he with the lance strikes to the head of the horse of his enemy (that is, of him with the sword), because he cannot beat a lance or sword which is so low. [In the Morgan, the Master's opponent wears a crown.] |

[5r-c] Aquesto e lo contrario dello zogo de lanza, e spada ch'e denanzi zoe che aquello cum la lanza fieri in la testa lo cavallo del suo inimigo zoe aquello dela spada perché non po rebater la lanza cum la spada si a basso. |

[43r-c] ¶ Questo e lo contrario dello zogho di lanza e de spada ch'e denanzi, çoe che quello cum la lanza fieri in la testa lo cavallo dello suo inimigho, zoe quello della spada, per che non po rebatter la lanza cum la spada si basso. |

[31a-c] Perche cum tua spada cum mi non possi incrosar |

|||

[12] Such a carry of the sword gives me four plays to make: This way of carrying the sword is named “the Long Tail Guard”. When you are riding to your opponent’s right side, this is a very good guard to use against the lance and all other hand held weapons. Keep firmly in your mind that thrusts and strikes from the left side should be beaten aside to your outside line, beating them diagonally upwards, not vertically. And the downward strikes should similarly be beaten aside to the outside, lifting your opponent’s sword a little as you do so. You can make these plays as these drawings show. |

Truly there are four ways of carrying a sword; This carry of the sword is called the Stance of the Long Tail, and it is very good against lance and sword and against all other handheld weapons, while riding to the right side of the enemy. Bear in mind well that the thrusts and the backhand blows should be beaten out to the side and not upward, and the downward blows should also be beaten to the side (lifting the sword of the enemy slightly); [this guard] can make all the plays corresponding to the figures that are depicted. |

[5v-b] Aquesto portar di spada si chiama posta de coda longa e si e molto bona, contra lanza e sp[ada], e contra ogni arma manuale. Cavalcando della parte dritta delo suo iminigo. E tente bene a mente che le punte e li colpi riversi si dibano rebater in fora zoe ala traversa e non in erto. E lli colpi di fendent si dibano rebater anche in fora levando un pocho la spada dello suo inimigo, e po fare gli zoghi segondo le figure depente |

[43v-b] ¶ Questo portar di spada se chiama posta de coda longa, e si e, molto bona contra lanza, e contra ogni arma manuale, cavalcando dela parte dritta dello suo inimigho. E tente ben a mente che le punte e li colpi riversi si debano rebatter in fora, zoe, ala traversa e non in erto. E li colpi de fendenti, si debano rebatter per lo simile in fora, levando un pocho la spada dello suo inimigo, E po fare gli zoghi segondo le figure depente. |

[31b-a] |

|||

[13] Of these two guards I make no comparison; This version of the Long Tail Guard is a good guard when your opponent attacks you from his sword on his left shoulder, as this opponent is shown doing here. And be advised that this guard will work against all attacks from both the right and the left sides, and against anyone, whether right handed or left handed. Hereafter begin the plays from the Long Tail that always begin with beating aside the opponent’s weapon, as you saw drawn in the first guard of the Long Tail. [In the Getty, the Master on the left is missing his crown.] |

Again this same Stance of the Long Tail is good when one comes against you with the sword on the left-hand side, as this enemy of mine does, and know that this guard counters all blows from the right side and from the left side, and counters anyone, be they right- or left-handed. And hereafter commence the plays of the Long Tail, which always beats in the fashion that was said earlier in the first Guard of the Long Tail. |

[5v-d] Anchora aquesta propria guardia de coda longa si e bona quando uno gli vene in contra cum la spada a man riversa, come vene questo mio inimigo, e sapia che questa guardia e contra tuti colpi de parte dritta e di parte riversa, e contra zaschuno che sia drito o manzino. E aqui de driedo comenzano gli zoghi de coda longa che sempre rebati per lo modo ch'e ditto denanci in prima guardia de coda longa. |

[43v-d] ¶ Anchora questa propia guardia de choda longa si'e bona quando uno gli vene incontra cum la spada, a man riversa come vene questo mio inimigo. E sapia che questa guardia e contra tutti colpi de parte dritta e di parte riversa, e contra zaschun che sia, o dritto o manzino. E qui dredo cominzano gli zoghi di coda longa che sempre rebatte per lo modo ch'e ditto denanzi in prima guardia de coda longa. |

[31b-c] De queste due guardie io non faço conperacion |

|||

[14] This is an equal crossing, without advantage; |

These two Masters are here crossed at the full of the sword. And that which one can do, the other can do also—that is, he can do all the plays of the sword with this crossing. But crossing is of three categories (that is, from the full of the sword to the tip of the sword), and whoever is crossed at the full of the sword can withstand a little, and whoever is crossed at middle of the sword can withstand less, and whoever at the tip of the sword can withstand nothing at all. So the sword, as such, has three matters—that is, a little, less, and nothing. |

[6r-b] Quisti doi magistri sono aqui incrosadi a tuta spada. E zo che po far uno po far l'altro, zoe che po fare tuti zoghi de spada cum lo incrosar. Ma lo incrosar si e de tre rasone, zoe a tuta spada, e punta de spada. E chi e incrosado a tuta spada pocho gle po stare. E chi e incrosado a meza spada meno gle po stare. E chi a punta de spada niente gle po stare. Si che la spada si ha in si tre cose, zoe pocho, meno, e niente. |

[32a-b] Questo e uno ingualivo e sença avantaço incrosar |

||||

[15] This point I gladly have set in your throat This is the first play that comes from the Long Tail Guard shown above. Here the Master beats aside his opponent’s sword, and then places a thrust into his chest or his face, as you see drawn here. |

I pierced through the exposed neck with the point of my sword. This is the first play which belongs to the Guard of the Long Tail which appeared here before: that is, that the Master beats the sword of his enemy and thrusts the point into his chest, or into his face as depicted here. [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

|

[44r-a] ¶ Questo e lo primo zogho che esse dela guardia de coda longa ch'e qui denanzi, zoe ch'ello magistro rebatte la spada dello suo inimigo, e mettigli la punta in lo petto, o vole in lo volto come qui depento. |

[32a-a] Questa punta in la golla volentera t'o posta |

[3v-a] ¶ Cuspide mucronis transfigo guttur apertum | ||

[16] Per the first Master that is in guard with the sword This is the second play that you can do after beating aside your opponent’s weapon. Here I strike this man over the head, because I see his head is unarmored. |

Using a wound, I, the fighting one, terrify the neck with a wound. This is the second play which can give a beat. I strike this man over the head, for I see well that he is not armored on his head. [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[6r-c] Aquesto si e lo segondo zogo che puo de quello rebater Io fiero a costui sopra la testa che vezo bene che ello non e armado in la testa. |

[44r-b] ¶ Questo si'e lo segondo zogho ch'e pur di quello rebatter, Io fiero costuii sopra la testa che vezo ben ch'ello non e armado la testa. |

[32a-c] Per lo primo magistro che sta in guardia cum spada |

|||

[17] By crossing ahead of your sword I have deviated it This is the another play, the third, where, after beating aside your opponent’s sword, you grab it with your left hand and strike him in the head. You could also strike him with a thrust. |

Here is another play, which is the third that beats the sword of his enemy; he grasps with his left hand and strikes the [enemy's] head, and he could also strike thusly with the point. |

[6r-d] Aquesto e uno altro zogo ch'e llo terzo che rebatuda la spada dello suo Inimigo ello la pigla cum la mane stancha e si gle feri la testa e acosi gle poria ferire de punta. |

[44r-c] ¶ Questo e un altro zogho lo terzo, che rebattu da la spada dello suo inimigho, ello la piglia cum la mane stancha, E si gli fieri la testa. e cossi gli poria ferir de punta. |

[32a-d] Per lo incrosar denançi tua spada io o'suariada |

|||

[18] You will lose your sword because of this catch This is the fourth play, in which the student strikes his opponent in the head and then takes his sword in the manner shown here. |

You, shamefaced, on account of this will either perhaps abandon your sword, This is the fourth play that the scholar wants to make—that is, take the sword in this way that you can see depicted here. [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[6v-a] Aquesto si e lo quarto zogo che lo scolar gle vole fare zoe tore la spada per questo modo che vuii possite vedere aqui depento. |

[44r-d] ¶ Questo si'e lo quarto zogho che lo scolaro gli vol ferir la testa e tor gli la spada per questo modo che vedete qui depento. |

[32b-a] La tua spada perderaii per questa presa |

[4r-b] ¶ Tu pudibundus obhoc ensem vel forte relinques | ||

[19] So that my sword would not be taken from me This is the sixth [fifth] play, where you take away your opponent’s sword. You use the hilt of your sword to lift his hilt upwards, which will make his sword fall from his hands. [This Master is missing his crown.] |

This is the fifth play, in which he wants to take the sword of his companion with the hilt of his sword; the other hilt he will have above, and the sword will fall from [his companion's] hand for certain. |

[6v-b] Aquesto si e lo quinto che vol tore la spada al compagno. Cum lo mantenir dela spada, l'altro mantenir lavera in erto. Dela mane gli cadera la spada per certo. |

[44v-b] ¶ Questo si'e lo Sexto che vol tore la spada al compagno. cum lo mantenir dela spada, l'altro mantenir Levera in erto, della mane gli cadera sa[!] spada per certo. |

[32b-b] Perche la mia spada non me sia tolta |

|||

[20] From horse to ground it will behoove you to go; This is the fifth [sixth] play that flows from the cover where you beat aside his sword. Here I throw my arm around his neck and turn quickly, and with the base of my sword I drive him to the ground. My counter is the second play that follows me, but this counter will not work if your opponent is armored.[20] |

He disengages lest I trample the beating heart on the ground. This is the sixth play that makes a cover with the beating of the sword. I throw my arm to his neck and quickly turn, and I will throw you to the ground, sword and all, without a doubt. My counter is here after and is the seventh play. Well that he has not achieved being armored. [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

|

[44v-a] ¶ Questo si'e lo quinto zogho che fa la coverta cum lo rebatter de spada. Io gli butto lo brazzo al collo allo voltar subito, cum tutta la spada in terra lu buttiro senza dubito. E lo mio contrario de dredo si'e lo segondo zogho. Ben che siando armado, di farlo, non a logo. |

[32b-c] Da cavallo in terra te conven andar |

[4r-c] ¶ Expedit ut terram calcato pectore pulses. | ||

[21] If it would behoove me to go to the ground, [sword] and all, This is the seventh play, which is the counter to the fifth [sixth] play above. It employs a strike to your opponent’s leg. But if your opponent is armored, you can’t trust this counter to work. |

This is the seventh play which is the counter—that is, the strike that he makes to the leg of the other one. If your companion were armored, you could not rely on this. [In the Morgan, the Master is missing his crown.] |

|

[44v-c] ¶ Questo si'e lo Settimo zogho ch'e contrario del quinto. Lo ferir ch'ello gli fa in la gamba a quello e desso. Se lo compagno fossi armado non te infidar in esso. |

[32b-d] Si del tuto in terra me conven andar |

|||

[22] I want to make my defense against the point and the edge, This is the eighth play, which is the counter to all of the preceding plays, but especially the plays of the mounted sword when the masters are in the Long Tail guard. When the Masters or their students are in this guard, and when I strike or thrust at them, and when they quickly beat my attack aside, then I quickly turn my sword and strike them in the face with my pommel. Then I move quickly from my position[23] and strike them in the back of the head with a horizontal backhand strike. |

I now protect myself from the cutting, and also the strong point. This is the eighth play and it is the counter to all the plays that came before, and especially of the plays of the sword on horseback and of the Masters that are in the Guard of the Long Tail. And when the Masters or Scholars stand in the aforesaid guard and I strike with a thrust or another blow, and they quickly beat my sword, I immediately give a turn to my sword and with my pommel I strike them in the face. And I can pass with my cover quickly and strike them behind the head with a backhand middle cut. |

[7r-a] Aquesto si e lo ottavo zogo ch'e contrario de tuti li zoghi che mi sono denanci. E maximamente deli zoghi de spada a cavallo, e deli lor magistri che sono in guardia de coda longa. Che quan li magistri, o scolari stano in la ditta guardia e io tra una punta, o altro colpo. E subito elli me rebateno, o taio, o punta che faza. Quando elli me rebateno subito io do volta ala mia spada e cum lo pomo mio io fero in lo volto. E poii passo cum la mia coverta presta. E cum lo riverso tondo gli fero dredo la testa. |

[44v-d] ¶ Questo si'e lo ottavo zogho ch'e contrario di tutti gli zoghi che mi sono denançi. e maxima mente delli zoghi de spada a cavallo, e delli lor magistri che sono in guardia de coda longa. Che quando li magistri, o scolari stano in la ditta guardia, e io gli tro[!] una punta o altro colpo, e subito elli me rebatteno o taglo o punta che faza, Quando elli me rebateno, subito e io do volta ala mia spada, e cum lo pomo mio, io gli fiero in lo volto. E poii passo cum la mia coverta presta e cum lo riverso tondo gli fiero dredo la testa. |

[33a-a] Per punta e taglio voio far mia deffesa |

|||

[23] So that you could not hit me in the face with your pommel, I am the ninth play, which is the counter to the counter that preceded me. When he turns his sword, I quickly place my hilt as you see drawn here, so that he cannot strike me in the face with his pommel. And if I raise my sword up, and turn it to the left, you[26] could well have your sword taken away. And if I am unable to do that, I could instead strike you with a backhand strike to the face, or with a quick turn of my sword strike you in the head with my pommel. Here ends the plays of sword against sword on horseback. If you know more of this, please share it. Here ends the plays of sword against sword on horseback. If you know more of this, please share it. [This Master is missing his crown.] |

The ninth I am, who makes the counter to that which came before me, so that when he gives a turn to his sword I quickly thrust my hilt (as you see depicted) so that he cannot strike me in the face with his pommel. And if I raise my sword high and give a turn to the left, it could very well be that his sword will be taken from him. And if that fails me and I cannot do it, so quickly will I make the turn that I will give to his face with the false edge of my sword (or I will strike him in the head with my pommel). This finishes the mounted play of sword against sword, and whoever keeps it in mind will give a good deal. |

[7r-b] Lo nono sone che fazo lo contra lo contrario che m'e denanci. Che quando ello da volta ala sua spada, subito lo mio mantenere meto como vuii vedeto depento, che cum lo pomo in lo volto non me po ferire, e s'io levo la spada in erto e dello riverso io piglo volta. Ben poria essere che la spada ti sara tolta. E si aquello mi falla che io non lo faza, dello riverso dela spada ti daro in la faza overo dello pomo ti firiro in la testa tanto faro una volta presta. Aqui finisse lo zogo a cavalo de spada a spada chi piu ne sa men dia una bona derada. |

[45r-a] ¶ Lo nono son che façço contra lo contrario che m'e denançi. Che quando ello da volta ala sua spada subito lo mio mantenir metto, comme voii vedete depento che cum lo pomo in lo volto non me po ferir. E s'io levo la spada in erto, e dello riverso io piglio volta, ben poria esser che la spada ti saria tolta. E si quello mi falla che io non lo faza, dello riverso dela spada ti daro in la faza. Overo delo pomo te feriro in la testa, tanto faro mia volta presta. ¶ Qui finisse lo zogho a cavallo de spada a spada. Chi piu ne sa men dia una bona derada. |

[33a-b] Perche tu non me daghi del pomo in lo volto |

|||

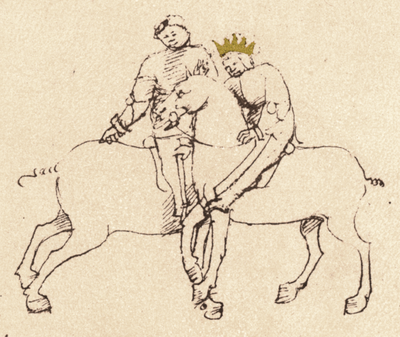

[24] In such a way have I grabbed you, running up behind, This is a grappling play, that is a play of the arms,[27] and this is how you do it: if your opponent is fleeing from you, you come up behind him to his left side. Now with your right hand grab the cheek piece of his bascinet, or if he is unarmored, grab him by the hair or by the right arm from behind his shoulder. In this way you will make him fall backwards to the ground. [In the Getty and Pisani Dossi, the Master is missing his crown.] |

I hold you captured by the helmet, whereby you turn your back backward. This is a play of grappling, and inasmuch as it is a play of grappling it is a play of the arms, and it is done in this way: when one flees from you and you come up behind him from the left side, grab him on the cheek of his helmet with your right hand (or, if he is unhelmed, grab him by the hair or the right arm from behind his shoulder), and in this way you will make him fall backward such that you will make him go to the ground. [In the Morgan, the Master is missing his crown.] |

[7v-a] Aquesto e zogo de abrazar e tanto, e a dire zogo de abrazar che zogo di braci, e si fa per tal modo. Quando uno te fugi e dela parte stancha tu gli ven apresso Cum la man dritta tu lo pigli in lo sguança dello bacinetto, e s'ello e desarmado per gli cavili, Overo per lo brazo dritto, per dredo le sue spalle, per tal modo lo faraii arivesare, Che in terra lo faraii andare. |

[45r-b] ¶ Questo e zogho de Abrazare zoe zogho de brazi, e si fa per tal modo. Quando uno ti fuzi e dela parte stancha tu gli ven apresso, Cum la man dritta tu lo pigli in le sguanze dello bacinetto, e se ello e disarmado, per gli cavigli, overo per lo brazo dritto per dredo le soy spalle, per tal modo faralo riversare, che in terra lo farai andare. |

[33a-c] Acossi come io t'o preso corandoti dredo |

|||

[25] You wanted to throw me from my horse This is the counter to the previous play, and that play will not work when this counter is quickly applied as follows: when he grabs you from behind you quickly switch hands on the reins, and with your left hand you lock him up as shown here. |

It is useful that you merely beat the ground This is the counter to the play that came before; this counter goes in this way with the catch that was made: that is, that quickly when he grabs him from behind, [the Master] should immediately exchange the hand on the reins, and with his left arm he should grab him in this fashion. |

[7v-b] Aquesto e contrario dello zogo che dinanci me va per tal modo aquesto contrario cum tal presa se fa zoe che subito quando ello per dredo lo piglia la man della brigla debia subito scambiare. E cum lo brazo stancho, per tal modo lo de piglare. |

[45r-c] ¶ Questo e contrario del zogho ch'e denanzi ne val per tal modo, questo contrario cum tal presa se fa zoe subito quando ello per dredo lo piglia, La man dela briglia debia subito scambiare, e cum lo brazo stancho per tal modo lo de pigliare. |

[33a-d] Da cavallo me vulisti pur butare |

|||

[26] I want to lift your leg with the stirrup, This student is about to throw his opponent off his horse, by grabbing the stirrup and pulling it upwards. If his opponent does not fall to the ground, he’ll be helpless in the air, and unless his opponent is tied to his horse, this play will not fail him. If he does not have his foot in the stirrup, the student can grab him by the ankle and raise him up into the air in the same way, as I described above. [In the Getty, the Master is missing his crown.] |

Lifting the leg simultaneously by the stirrup, this, my Powerful right [hand], turns you to the furthest. Nor will your leg be made better. This Scholar wants to throw this one from his horse—that is, he grabs him by the stirrup and lifts him up. If he doesn't go to the ground, he would clearly be floating in the air! Assuming he isn't lashed to his horse, this play cannot fail. If he does not have his foot in a stirrup, grab him by the ankle and it will be even easier to lift him up than I said before so do as was written here earlier. [In the Morgan, the Master is missing his crown.] |

[7v-c] Aquesto scolar vole butar questo da cavallo zoe che lo pigla per la staffa e levalo in erto. S'ello non va in terra in aere stara per certo. Salvo che se non e a cavallo ligado. Aquesto zogo non po essere falado. S'elo non ha lo pe in la staffa per lo collo del pe lo pigla che piu vale levando in erto come denanci e ditto, fate aquello ch'e denanzi aqui scrito. |

[45r-d] ¶ Questo scolaro vole buttar questo da cavallo çoe ch'ello lo piglia per la staffa e levalo in erto. Se ello non va in terra in aere stara per certo, Salvo s'ello non e[30] al cavallo ligado, questo zogho non po esser fallado. E se ello non a, lo pe in la staffa per lo collo del pe lo piglia che piu vale levandolo in erto come denanzi ditto. Fate quello ch'e denanzi qui scritto. |

[33b-a] La staffa cum la gamba te voio levar |

|||

[27] You wanted to throw me well from my horse; Here is the counter to the previous play: when your opponent grabs your stirrup or your foot, throw your arm quickly around his neck, and in this way you will be able to unhorse him. Follow this advice and he’ll end up on the ground for sure. |

Look how strongly I hold your neck by the shoulder, <in front of you> This here is the counter of the play that appeared before it, so if one grabs you by the stirrup or by the foot, throw your arm to his neck. You should do this quickly, for in this fashion you could dismount him from his horse; if you do this, he will hit the ground without fail. |

[7v-d] Lo contrario aqui del zogo ch'e denanci aparechiado et se uno te pigla per la staffa overo per lo pe, Butagle lo brazo allo collo, aquesto subito far se de. E per tal modo lo porai descavalcare da cavallo. S'tu fai aquesto ello andera per terra senza fallo. |

[45v-a] ¶ Lo contrario del zogho denançi qui e parechiado, che se uno ti piglia per la staffa, overo per lo pe, buttagli lo brazo al collo, e questo subito far si de. E per tal modo lo poraii discavalcare da cavallo. S'tu fa questo ello andera in terra senza fallo. |

[33b-b] De cavallo tu me volisti ben butare |

|||

[28] I want to throw you and your horse to the ground; This is a method of throwing your opponent to the ground by throwing his horse. It’s done like this:[37] when you and your mounted opponent close, ride to his right side. Then throw your right arm over the neck of his horse, and grab the bridle close to where the bit enters its mouth, and forcefully wrench it upwards and over. At the same time make sure your horse’s shoulders[38] drive into his horse’s haunches[39] In this way you will bring down both him and his horse at the same time. [In the Getty, the Master is missing his crown.] |

I will throw you and your horse, prevented by none, This is a play of throwing one to the ground, horse and all: that is, the Master rides to the right side of his enemy and throws his right arm over the neck of his [enemy's] horse. And he grabs the bridle of his [enemy's] horse behind the bit, rotates the head of the horse up, and he should spur his horse with his foot striking the rump or flanks. And in this way he will fall, horse and all… |

[8r-a] Aquesto e uno zogo de butare uno in terra cum tuto lo cavallo zoe che lo magistro cavalcha dela parte dritta dello suo Inimigo, e buta lo suo brazo dritto per sopra lo collo dello suo cavallo. E pigla la brena delo so cacavallo[!] apresso lo morso, revoltando la testa dello cavallo in erto e llo suo debia speronare che lo suo cavallo cum lo suo petto fiera in gropa overo in gli fianchi del suo cavallo. E per tal modo cadera cum tuto[40] lo cavallo. Lo contrario de questo magistro che vole butare in terra lo suo inimigo cum tuto lo cavallo. Si e aquesto che subito quando lo magistro pigla la sua brena. Che ello debia butare lo brazo al collo per modo che fa lo quarto zugadore che m'e denanci per tal modo andera in terra. |

[45v-b] ¶ Questo si'e un Atto de butar uno in terra cum lo cavallo. Lo rimedio di buttar uno in terra cum tutto lo cavallo per tal modo si fa. Quando tu scontre uno a cavallo. Cavalca dela sua parte dritta. E llo tuo brazo dritto buttalo per sopra lo collo del suo cavallo, e pigla la sua brena a presso lo morso che gli sta in bocha, e rivoltalo in erto per forza. E llo petto del tuo cavallo fa che vada per mezo la groppa del suo cavallo. E per tal modo convene andar in terra cum tutto lo cavallo. |

[33b-c] Ti e'l tuo cavallo per terra voio butar |

|||

[29] This is the counter to the play before, where you throw your opponent to the ground together with his horse. This is an easy counter: when the student throws his arm over the neck of your horse to grab the bridle, you should quickly throw your arm around the student’s neck, and you will effectively make him let go. Just do as the drawing shows. |

…This is the counter of the play that came before in which he wants to throw his companion to the ground along with his horse. This is an easy thing to remember, that when the Scholar throws his arm over the neck of his horse to grab the bridle, the player should quickly throw an arm to the neck of the Scholar, and thus he is forced to release it. Following that which you see depicted here, so should you do. |

[45v-c] ¶ Questo si'e lo contrario di questo zogho qui denanzi che vole buttar in terra lo compagno cum tutto lo cavallo. Questa e lizera chosa da cognossere che quando lo scolaro butta lo brazo per sopra lo collo del cavallo per piglar la brena, de subito ello gli de buttar el brazo lo zugador al collo dello scolaro, e per forza ello convien lassar. Segondo vedeti qui depento si debia fare. |

|||||

[30] I seek to take the bridle from your hands In this play you take the reins of your opponent’s horse out of his hands, as you see drawn here. When you and your mounted opponent close, ride to his right side, and throw your right arm over his horse’s neck and grab the reins near his left hand with your right hand turned down. Now pull the reins over his horse’s head. This play is safer to do in armor than unarmored. [In the Getty, the Master is missing his crown.] |

This is a play of taking the bridle of a horse from the hand of your companion in the way that you see depicted here. The Scholar, when he goes against another on horseback, should ride to the right side and throw his right arm over the neck of the horse, grabbing its bridle near his hand on the left-hand side, and so take the bridle off the horse's head. And this play is more secure in armor than unarmored. |

[8r-b] Aquesto e uno zogho de tore la brena dello cavallo dela maane[43] delo compagno per modo che voii vedite aqui dipento, lo scolar quando ello se scontra cum uno altro da cavallo, ello gle cavalcha dela parte dritta, e butagli lo suo brazo dritto per sopra lo collo del cavallo, e pigla la sua brena[44] apresso la sua man sinistra cum la sua man riversa. E tra la brena delo cavallo dela testa. E aquesto zogo e piu seguro armado che disarmado. |

[45v-d] ¶ Questo si'e un zogo di tore la brena delo cavallo de mane del compagno per modo che vedeti qui depento. Lo scolaro quando ello se scontra cum uno altro da cavallo, ello gli cavalca dela parte dritta, e butta gli lo suo brazo dritto per sopra lo collo dello cavallo, e pigla la sua brena apresso la sua man sinestra, cum la sua mane riversa. E tra la brena dela testa del cavallo. E questo zogo e piu siguro armado che disarmado. |

[33b-d] Per tor la brena de mano aquello cercho de far

E dela testa del tuo cavallo la voio tirar E quando la brena sera dela testa tirada A mia posta io te menaro in altra contrada |

|||

[31] This Master has lashed a cord to his saddle This Master has bound one end of a strong rope to his horse’s saddle, and the other end to the butt of his lance. First he strikes his opponent, then he will cast the lance to the left side of his opponent, over his opponent’s left shoulder, and in this way he can drag his opponent from his horse. |

This Master has lashed a strong cord (that is, one end) to the saddle of his horse, and the other end is lashed to the foot of his lance. First he wants to strike, and then to put the tied part of the lance to the left of his enemy, throwing it over his shoulder, and thereby to be able to pull him off his horse and onto the ground. |

[2v-a] ¶ Aquesto magistro ha ligada una forte corda alla sella dello suo cavallo, zoe uno cavo, e l'altro cavo si a ligado alo pe della sua lanza primo lo vol ferir e poii la lanza a cosi ligada della parte stancha delo suo inimigo sopra la spalla la vole butar, per poterlo zo dello cavallo strasinare. |

[46v-a] ¶ Questo magistro a ligada una forte corda ala Sella del suo cavallo zoe uno cavo, L'altro cavo sia ligado allo pe dela sua lanza. Primo lo vol ferire, e poii la Lanza chossi ligada della parte stancha dello so inimigo sopra la spalla la vola buttare, per posserlo lo zo del cavallo strassinare. |

[34b-a] Questo magistro si'a ligada una corda ala sella |

|||

[32] This scoundrel was fleeing from me towards a castle. I rode so hard and fast at full rein that I caught up with him closed to his castle. And I struck him with my sword in his armpit, which is a difficult area to protect with armor. Now I withdraw to avoid retaliation from his friends. |

[46v-c] ¶ Questo Ribaldo mi fuziva a una forteza. tanto corsi che io lo zunsi apresso la fortezza sempre corando a tutta brena. E de mia spada lo feri sotto la lasena, Li che male si po l'omo armare. E per paura de soii amisi voglio retornare. |

||||||

Here ends the Flower of the Art of Combat, Here ends this book that was written by Fiore the scholar, who has published here everything he knows about this art, that is to say, everything he knows about armed fighting is contained within this book. This same Fiore has named his book “The Flower of the Battle”. Let he for whom this book was made be forever praised, for his nobility and virtue have no equal, Fiore the Friulian, a simple elderly man, entrusts this book to you. |

Florius, the most skilled authority, previously[45] brought forth |

[46v-d] ¶ Qui finisse lo libro che a fatto lo scolaro Fiore che zo ch'ello sa in quest'arte, qui l'a posto, zoe in tutto la armizare, in questo libro e lo fiore Fior di Bataglia per nome ello e chiamato. Quello per chi ello e fatto sempre sia apresiato che de Nobilita e virtu non se trova Lo parechio, Fior Furlan a voii si recomanda povero vechio. |

[36b-a] Aqui finisse el fior de'l'arte delo armiçar |

[44r-c] ¶ Florius hunc librum quondam pritissimus auctor |

- ↑ Note that in the Morgan, this octave is used to introduce the spear, but a very similar sestet is used in the Pisani Dossi to introduce the mounted fencing. They are included here in the mounted section rather t han the spear because the Pisani Dossi has a separate introduction for the spear.

- ↑ Fiore means that the text of 41r-a actually applies to the drawing at 41r-b (i.e. the drawing to the right, who is the rider winning the engagement, hence the “Re” [King]). I assume this was an error by the scribe. I've expanded the line so that it is comprehensible.

- ↑ The abbreviation ꝑa for "persona" isn't attested in Capelli, but he does list ꝑam for "personam", which is close enough. Morgan has ꝑsona.

- ↑ The second line has been over-written to darken worn-away letters. If there were annotations, they have not survived.

- ↑ This pair of verses has a bracket at the end, which has been posited as indicating enjambment of the lines by Mondschein. As there is clearly a period at the end of the first line, this cannot be the case here.

- ↑ Depending on the interpretation of the final abbreviation, the last line may be read in different ways; the final verb might be perdet (loses), raedet (pillages), or prodet (thrusts forward). We have chosen the last of these as it is least specific to whether the lance in question is winning or losing the fight, which is unclear from the rest of the verse.

- ↑ Up to this point, the text is partially effaced.

- ↑ Corrected from "e" to "o".

- ↑ Added later: "ego".

- ↑ Added later: "de la pointe".

- ↑ Added later: "remoror [!] jaculum".

- ↑ The translator appears to be using 'stringere-refringere' as a pair, as both words are associated with defending and attacking fortified gates, for rhetorical effect; however, English doesn't have a good oppositional pair that also conveys the meanings of the words.

- ↑ Added later: "eqqus". Probably meant to be “equus”, but the two q’s are fairly clear.

- ↑ This word was obliterated somehow (“et” and “cesura” both show uncorrected damage) but has been written over by a later hand in similarly-colored ink. Further, someone has tried to write something above it, perhaps a French equivalent—the superscript is unreadable, but the second word, above cuspide, appears to end in “te” and could be “pointe”. The superscript above “acute” may have been in the D1 or F hand, but not enough is clear. There may have been a superscript above mucronem that was erased, although the remaining strokes look like they may have suffered the same damage as the rest of the page. None of the superscripts are clear enough to certainly identify the hands.

- ↑ A bracket, similar to the enjambment bracket, hangs off the last line.

- ↑ "ue" is mostly effaced.

- ↑ Supposing cuspide means sword and not point, ense could mean something other than sword, such as “sword technique” or “sword position”.

- ↑ There is an erasure above “cervice”, but we were not able to discern any letters.

- ↑ Rebecca notes: small words like et or hoc may be left out in order to shape it into something like meter.

- ↑ I’ve expanded this sentence so that it makes more sense.

- ↑ This paragraph is written with a wedge-shaped gap in the text. This might be a coincidence, or it might indicate that the manuscript being copied had the text flowing around the sword of the player (as is done on the next page), and the scribe assumed that would be the case here as well.

- ↑ This paragraph is partially effaced and hard to read.

- ↑ Fiore actually writes “Then I pass from my quick cover” but the words make no sense, since he is not in a cover but has just hit his opponent in the face with a pommel strike. I’ve altered it to give it more sense.

- ↑ Added later: "te juc g???et".

- ↑ Added later: "de la poignee".

- ↑ Note the switch from “he” to “you”. This is something Fiore does quite a lot.

- ↑ Abrazare comes from “A brazi”—“with the arms”.

- ↑ There is an erased note here with multiple words, but the letters are not very clear. One speculated reading of the second word is "heaume."

- ↑ This abbreviation can also mean "modo"

- ↑ Literally "ē", which would be read as "en", but in context it seems to make more sense as è, a conjugation of essere.

- ↑ To the right of the verse are a bracket, a +, and some erased words. The binding did not open wide enough to reveal these with ultraviolet photography.

- ↑ We have rendered per terram as “to the ground” rather than “through the ground”.

- ↑ Added later: "pro tui".

- ↑ This can also be read "conatus"

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet".

- ↑ This separation between the initial letter and remainder of the first word of the line is inconsistent with the rest of the text.

- ↑ I’ve removed the redundant repetition.

- ↑ Petto means chest but no part of a horse is named the “chest”, so I changed this to “shoulders” which refers to the area of the horse Fiore is talking about that would ram the opponent’s horse.

- ↑ The “groppa” means the crupper, which refers to the horse’s hind quarters.

- ↑ Corrected from "i"; probably intended to be a "u", but looks like an "a".

- ↑ Added later: "eqquus".

- ↑ Added later: "cert mords de bride".

- ↑ Overwritten and difficult to decipher.

- ↑ Written over a previously-effaced word that can't be deciphered.

- ↑ This word was the source of considerable trouble. We initially assumed, as others have, that it denoted that Fiore was deceased when the manuscript was prepared (quondam Florius, “the late Fiore”). However, further research on the word (which seemed merited since it could indicate a significant biographical fact) indicated that such a reading was simply not possible for most examples of the word in Medieval literature, e.g. “ubi quondam Deus” is probably not seeking to describe a deceased God. In fact, “quondam” is generally an adverb rather than a quasi-adjective, and some dictionaries, such as Lewis & Short, specify that it only has the meaning of “the late” if the person it is applied to is deceased. Rather than becoming trapped in a loop of circular reasoning (assuming Fiore is deceased and translating quondam that way, and then concluding that Fiore is deceased due to the translation of quondam), we interpreted the word in its more normal adverbial sense and applied it to “edidit”. For more definitions of quondam, see the entries in Logeion: http://logeion.uchicago.edu/index.html#quondam