|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Fiore de'i Liberi/Images"

| Line 2,561: | Line 2,561: | ||

| width = 240em | | width = 240em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{subst:Fiore de'i Liberi/Dagger/5th master}} |

{{master subsection end}} | {{master subsection end}} | ||

Revision as of 14:48, 4 October 2018

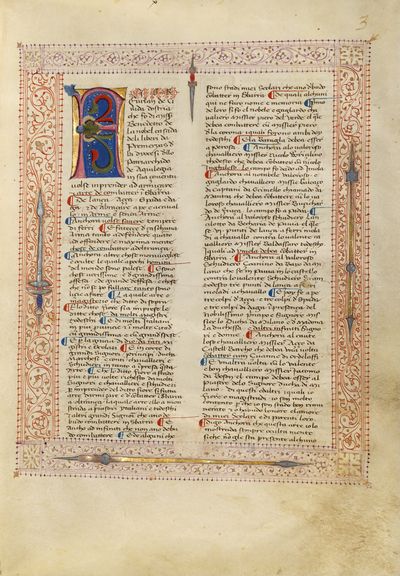

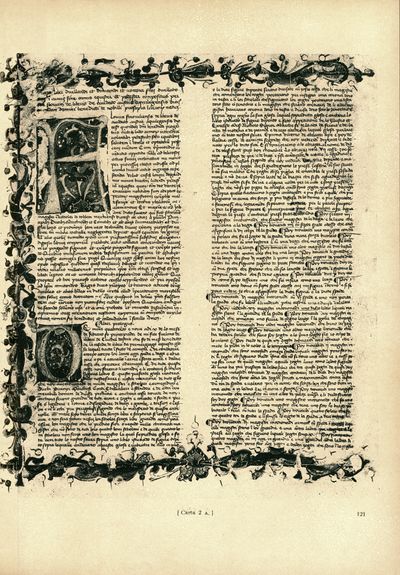

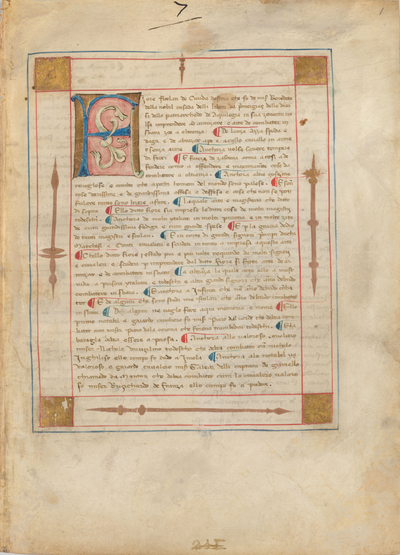

Images |

Images |

Completed Translation (from the Getty and PD) |

Draft Translation (from the Paris) |

Morgan Transcription |

Getty Transcription |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

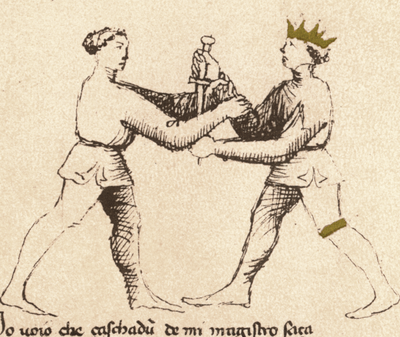

| [No Image] | [1] In the name of God and Saint George, we begin our system with Grappling on foot, seeking to gain superior holds. Holds are not superior unless they give you an advantage. Thus we four Masters seek to achieve advantageous holds through the techniques you see depicted here. |

[4a-t] Principiamo prima in nome de dio e de meser sant zorzo delo abraçare a pe aguadagnare le prese. Le prese non son guadagnade se le non son cum avantaço, Pero noii ·ⅲⅰ· magistri cerchamo prese avantaçade chomo positi vedere dipento. |

|||||

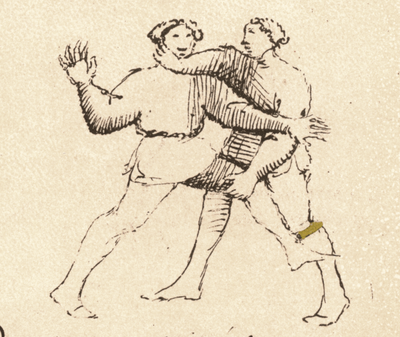

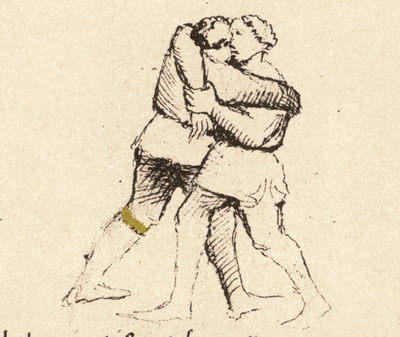

[2] [The Long Guard] I am ready to show you how I win with my holds, |

Even if you capture me, I would win; I am truly prepared. |

[4a-a] Per guadagnar le prese e son aparichiato, |

[38v-a] ¶ Vt mihi prensuras lucrer, sum nempe paratus. | ||||

I am Posta Longa and I seek you like this. And in response to the first grapple that you attempt on me I will bring my right arm up under your left arm. And I will then execute the first play of Grappling. And with that lock I will force you to the ground. And if that lock looks like it will fail me, then I will switch to one of the other locks that follow. |

[6r-a] ¶ Io son posta longa e achosi te aspetto. E in la presa che tu mi voray fare. Lo mio brazo dritto che sta in erto. Sotto lo tuo stancho lo mettero per certo. E intrero in lo primo zogho de Abrazare. E cum tal presa in terra ti faro andare. E si aquella presa mi venisse a manchare. In le altre prese che seguen vigniro intrare. |

||||||

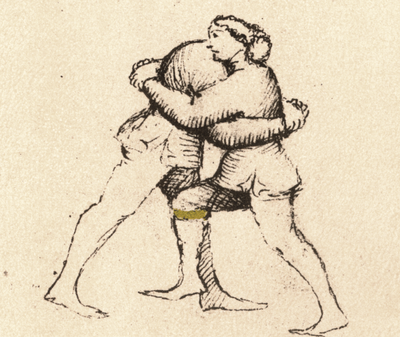

[3] [The Boar's Tooth] I seek to reverse the fight, |

I seek to shift, <for> which reason I would be able to deceive you well. |

[4a-b] De pugna mutacion cercho de'fare |

| ||||

I counter you with Dente di Zenghiaro. And with this move I am sure to break your grip. And from this guard I can transition to Porta di Ferro, which will force you to the ground. And if my plan fails me because of your defense, I will seek other ways to hurt you, for example with breaks, binds and dislocations, as you see depicted in these drawings. |

[6r-b] ¶ In dente di zenghiar contra ti io vegno. Da romper la tua presa certo mi tegno. E di questa isiro, e in porta di ferro intrero. E per metterte in terra saro aparechiado. E si aquello ch'i'o ditto mi falla per tua defesa. per altro modo cerchero di farte offesa. Çoe cum roture ligadure e dislogadure. In quello modo che sono depente le figure. |

||||||

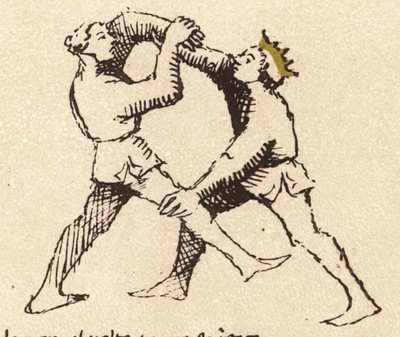

[4] [The Iron Gate] If you fail to beat me with your skill, I believe I wait for you without moving in Porta di Ferro, ready to grapple with all of my skill. And this guard can be applied not only in the art of grappling, but also in the art of the Spear, the Poleaxe, the Sword, and the Dagger. For I am Porta di Ferro, full of danger. Those who oppose me will always end up in pain and suffering. And as for those of you who come against me trying to get your hands on me, I will force you to the ground. |

If you do not conquer with a trick, I can, of course, believe [that] |

[6r-c] ¶ In Porta di ferro io ti aspetto senza mossa. Per guadagnar le prese a tutta mia possa. Lo zogho de Abrazare aquella e mia arte. E di lanza, Azza, Spada, e daga o grande parte. Porta di ferro son di malicie piena. Chi contra mi fa, sempre gli do briga e pena. E a ti che contra mi voii le prese guadagnare. Cum le forte prese io ti faro in terra andare. |

[4a-c] Se per inçegno non me vinceraii zo creço |

| |||

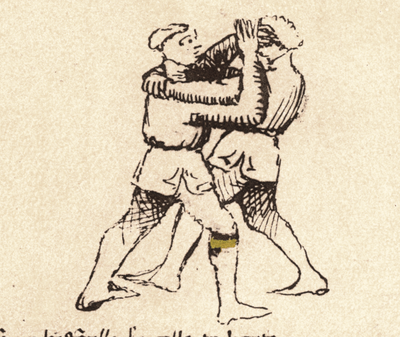

[5] [The Guard of the Forehead] I advance upon you with my arms well forward I am Posta Frontale, used to get my hands on you. Now if I come against you in this guard, you may lay hands on me. But I will then move from this guard, and with skill I will take you down to Porta di Ferro. Then I will make you suffer as if you had fallen into the depths of hell. And I will serve you so effectively with locks and dislocations, that you will quickly acknowledge my superiority. And as long as I don’t forget my skills, I will gain my superior holds. |

Behold! I am coming, eager to overcome by means of the stretched shoulder, |

[6r-d] ¶ Posta frontale son per guadagnar le prese. Si in questa posta vegno, tu me faraii offese. Ma io mi movero di questa guardia. E cum inzegno ti movero di porta di ferro. Peço ti faro stare che staresti in inferno. De ligadure e rotture ti faro bon merchato. E tosto si vedera chi avera guadagnato. E le prese guadagnero, se non saro smemorato. |

[4a-d] Cum li braci vegno acusi ben destese |

| |||

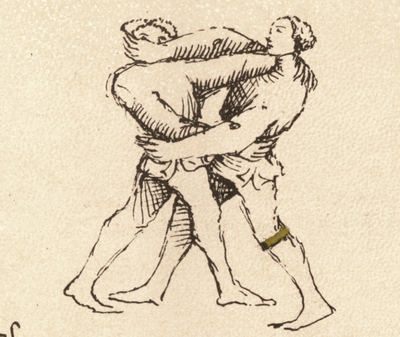

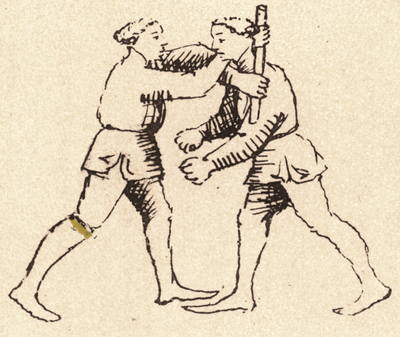

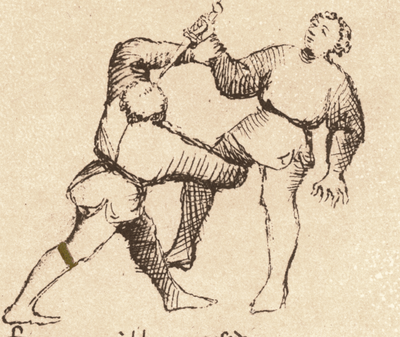

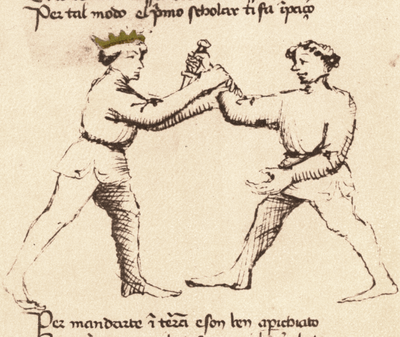

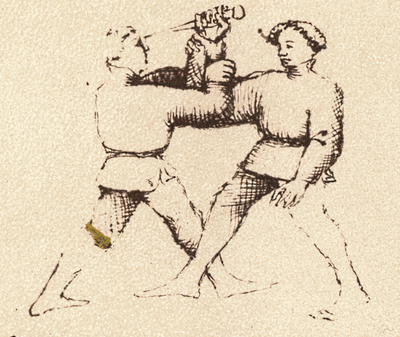

[6] With this move I will either force you to the ground This is the first play of Abrazare and from every grappling guard you can arrive at this play, and from this position, proceed as follows: jam his right inside elbow with your left hand, and bring your right hand up behind and against his left elbow as shown. Now quickly make the second play, that is to say, having gripped him like this, turn your body to the left, and as a result he either goes to the ground or his arm will be dislocated. |

In this way, I, using a capturing, would make you touch the earth. |

[6v-a] ¶ Questo si'e lo primo zogho de abrazare, & ogni guardia d'abrazare si po 'rivare in questo zogho, e in questa presa zoe. Pigli cum la man stancha lo suo brazo dritto in la piegadura del suo brazo dritto, e la sua dritta mano metta chosi dritta apresso lo suo cubito, e poii subito faza la presa del segondo zogho, zoe piglilu[!] in quello modo e daga la volta ala persona. E per quello modo, o ello andara in terra, overo lo brazo gli sera dislogado. |

[4b-a] Cum questa presa in terra andare ti faro |

[39r-b] ¶ Hac ego prensura, faciam te tangere terram. | |||

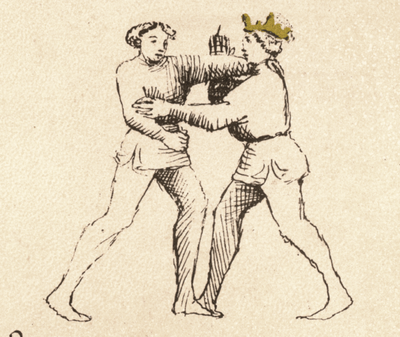

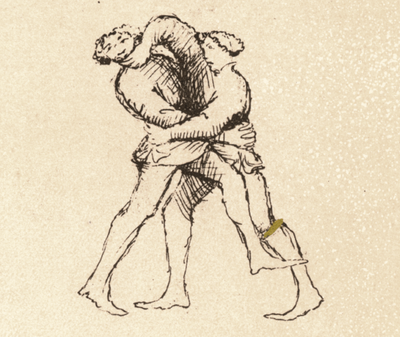

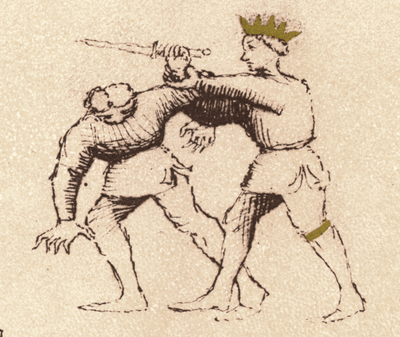

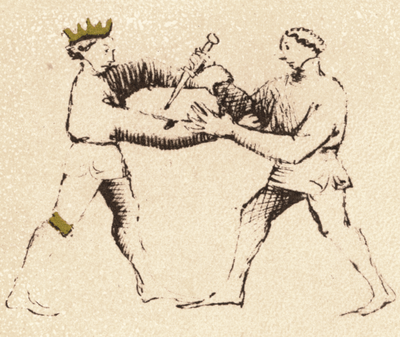

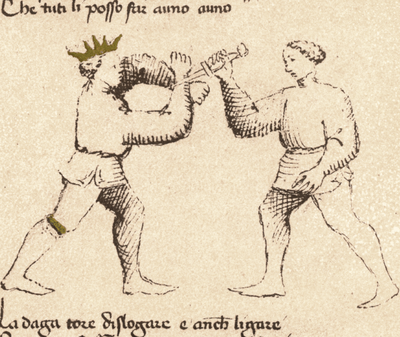

[7] Either I will make you kiss the ground with your mouth, As the Scholar of the First Abrazare Remedy Master says, I am certain to put this man to the ground, either by breaking or dislocating his left arm. And if the Zugadore who fights with the First Abrazare Remedy Master takes his left hand off the shoulder of the Remedy Master in order to make a defense, then I will quickly let go of his right arm with my left hand and instead seize his left leg with my left hand, and grip his throat with my right hand in order to throw him to the ground, as you see depicted in the third play. |

I would compel you, ugly, to lick the ground with your mouth; [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[6v-b] ¶ Io Scolaro del primo Magistro si digo che son certo de zitar questo in terra, o rompere suo brazo sinistro, overo dislogare. E si lo zughadore che zogha cum lo Magistro primo levasse la man stancha dela spalla del Magistro per far altra defesa, subito io che son in suo scambio lasso lo suo brazo dritto cum la mia man stancha, piglo la sua stancha gamba, e la mia man dritta gli metto sotto la gola per mandarlo in terra in questo che vedeti depento lo terzo zogho. |

[4b-b] Cum la bocha la terra ti faro basare |

[39r-d] ¶ Ore tuo terram te cogam lambere turpem.

| |||

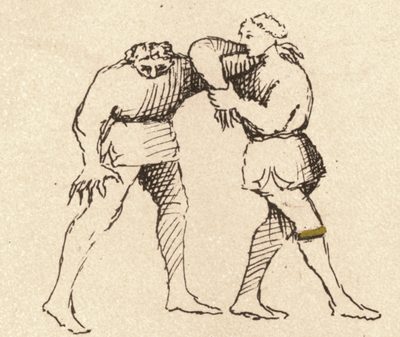

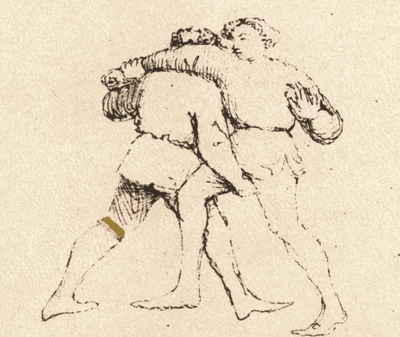

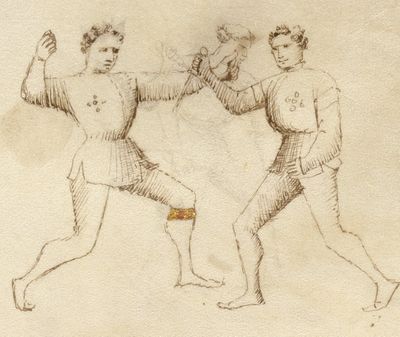

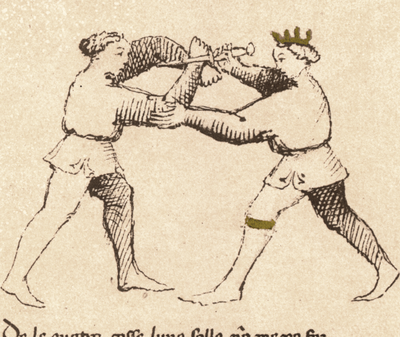

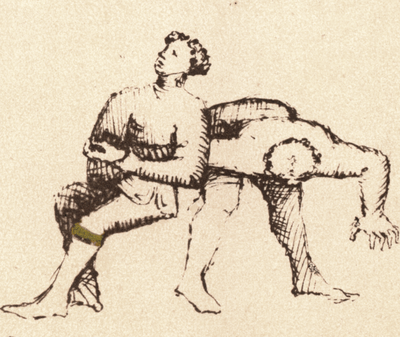

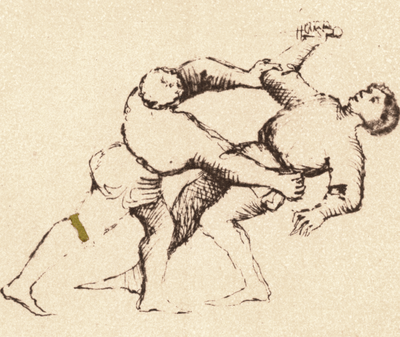

[8] And I will put you on the ground on your back, The scholar that came before me speaks truly that from his hold he will force his opponent to the ground or dislocate his left arm. As he told you, if the Zugadore takes away his left hand from the shoulder of the Remedy Master, then the Remedy Master transitions to the Third Play, as you see depicted here. Thus, the First play and the Second play are really one single play, where the Remedy Master forces the Zugadore to the ground with a turn of his body, while in this Third play the Zugadore is thrown to the ground onto his back. |

I would throw you, without pause, into the farthest earth up to the kidneys. |

[6v-c] ¶ Questo scolaro ch'e denançi de mi dise ben lo vero che dela sua presa convene che vegna in questa per metterlo in terra overo dislogargli'l brazo stancho. Anchora digo che si lo zugadore levasse la man stancha dela spalla del magistro che lo Magistro, che lo magistro[80] 'rivaria al terço zogho simile mente chomo vedeti depento. Sì che per lo primo zogho e per lo segondo che uno proprio zogho, e'llo magistro lo manda in terra cum lo volto, e lo terzo lo manda cum le Spalle in terra. |

[4b-c] E te faro cadere in terra cum la schena |

[39v-b] ¶ Renibus in terram iaciam te protinus imam. | |||

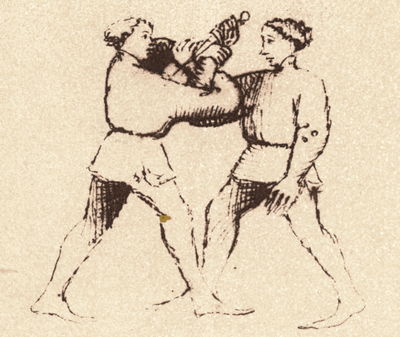

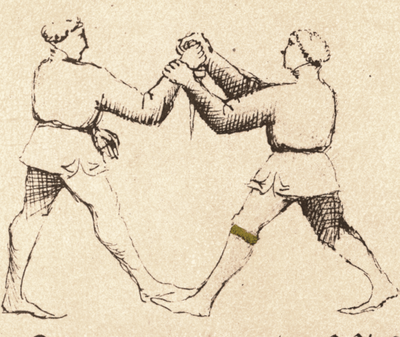

[9] Even if you were a master of grappling, This is the Fourth Play of Abrazare, by which the Scholaro [Student] can easily force the Zugadore to the ground. And if he cannot force him to ground like this, he will seek other plays and techniques and use other methods, as you will see depicted below. You should know that the plays and the techniques will not always work in every situation, so if you do not have a good hold, you should quickly seek one, so as not to let your opponent gain any advantage over you. |

In this way, I would make you sink down to the earth using a capturing, [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[6v-d] ¶ Questo e lo quarto zogho de Abrazare ch'e liziero se lo scolaro po metter lo zugadore in terra. E se non lo po mettere per tal modo in terra, ello zerchera altri zogi e prese como si po fare per diversi modi chomo vedereti al dredo noii depento, che posseti ben savere che gli zoghi non sono eguali ne le prese rare volte, e pero chi non a bona presa, se la guadagni piu presto che'l po, per non lassare avantazo al nimigho suo. |

[4b-d] Se tu fussi magistro delo abraçare |

[39v-d] ¶ Hac te prensura facerem procumbere terrae, | |||

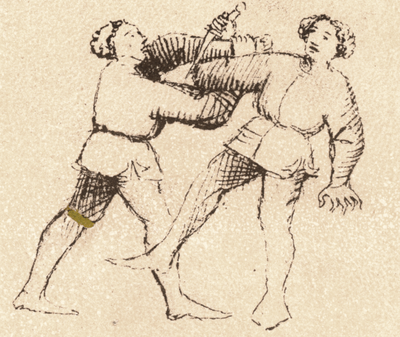

[10] With the grips that I have on you above and below, This grip that I make with my right hand at your throat will bring you pain and suffering, and with it I will force you to the ground. Also let me tell you that if I seize you under your left knee with my right hand, I will be even more certain of driving you into the ground. |

Because of capturing, <by> wrestling above and below [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[7r-a] Questa presa che o cum la mia mano dritta in la tua gola, io te fazo portare doglia e pena, e per quello tu andaraii in terra. Anchora digo che se ti piglio cum la mia mano mancha sotto lo tuo stancho zinochio che saro piu certo de mandarte in terra. |

[4b-e] Per la presa che io ho desovra e ti desota |

[40r-b] ¶ Propter prensuram, superb quaa, luctor et infra, | |||

[11] Your hand in my face is well placed, I am the counter of the Fifth Play [10] that is shown earlier. And let me explain that if with my right hand I push up the elbow of his hand that seeks to harm me, I will turn him in such a way that either I will force him to the ground, as you see here depicted, or I will gain a hold or a lock, and so I will have little concern for his grappling skills. [In the Pisani Dossi, the Master is missing his crown.] |

I served up the palms to the face.[81] But still I cheerfully moved |

[7r-b] ¶ Io son contrario del ·Ⅴ·to zogo denanci apresso. E si digo che se cum la mia mano dritta levo lo suo brazo dela sua mane che al volto mi fa impazo, faro gli dar volta per modo ch'io lo metero in terra, per modo che vedeti qui depento, overo che guadagnaro presa o ligadura, e de tuo abrazar faro pocha cura. |

[4b-f] Le man al volto si to ben poste |

||||

[12] By putting my head under your arm, From this hold that I have gained, and by the way I hold you, I will lift you off the ground with my strength and throw you down under my feet head first with your body following. And as far as I am concerned, you will not be able to counter me. |

You, confused one, will be spread on the ground (like a tarp) in sadness and disorder; |

[7r-c] ¶ Per la presa ch'i'o guadagnada al modo che io te tegno, de terra te levaro per mia forza, e sotto gli mei piedi te metero prima cum la testa che cum lo busto, e contrario non mi farai che sia visto. |

[5a-a] Per la testa che io o posta soto el tuo braço |

||||

[13] Because of my thumb pressing under your left ear, When I press my thumb under your ear you will feel so much pain that you will go to the ground for sure, or I will make other hold or lock that will be worse than torture for you. The counter that can be made is the Sixth play [11] made against the Fifth Play [10] when he puts his hand underneath his opponent’s elbow. This counter can certainly be done to me here. |

I but hold this finger to the left ear during wrestling, [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[7r-d] ¶ Lo dedo poles te tegno sotta la tua orechia che tanta doglia senti per quello che tu andarai in terra sença dubito, overo altra presa ti farò o ligadura che sara piu fiera che tortura. Lo contrario che fa lo Sesto zogho contra lo quinto quello che gli metti la mano sotto lo chubito. Aquello si po far a me tal contrario sença nessuno dubito. |

[5a-b] Per lo dedo che io te tegno soto la rechia stancha. |

[40v-d] ¶ Aure sed hac digitum teneo luctando sinistra | |||

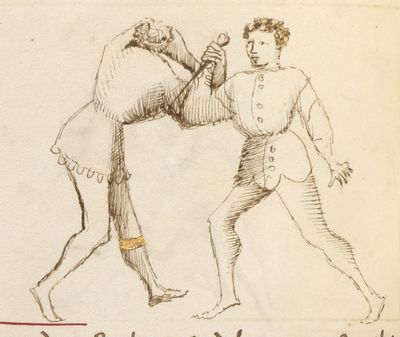

[14] With great cunning you grabbed me from behind, You seized me from behind in order to throw me to the ground, and I turned like this. And if I fail to throw you to the ground you will have a lucky escape. This play is a good finishing move, but unless this is done quickly, this remedy will fail. |

<If you>, Traitor, by your art have seized me from behind, |

[7v-a] ¶ Tu mi piglasti di dredo per butarme in terra e per questo modo io son voltado. Se io non te butto in terra tu naii[!] bon merchado. Questo zogho si'e un partido, chosi tosto sara fatto che'l contrario sara fallito. |

[5a-c] Dedredo me prendisti a grande tradimento |

||||

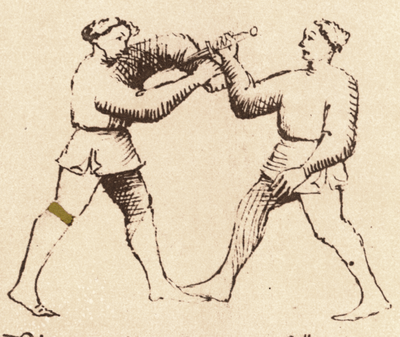

[15] This is a grappling move that involves the Gambarola, This is a play that involves a throw over the leg [Gambarola] which is a risky move in grappling. So if you want to make this leg throw successfully, you will need to do it with power and speed. |

Here, meanwhile, the play of turning of legs is discussed. |

[7v-b] ¶ Questo si'e un zogho da Gambarola che non e ben sigura chosa nel abrazare. E se alguno pur vol fare la gambarola, faza la cum forza e presta mente. |

[5a-d] Questo e un abraçare de gambarola |

[41r-c] ¶ Ludusb hica interdum celebratur crurad rotandic. | |||

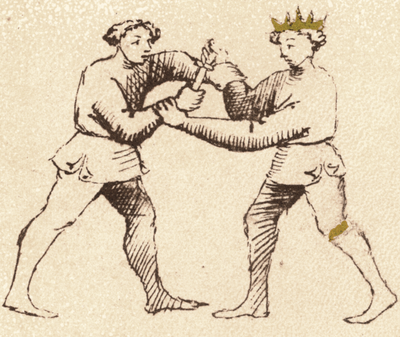

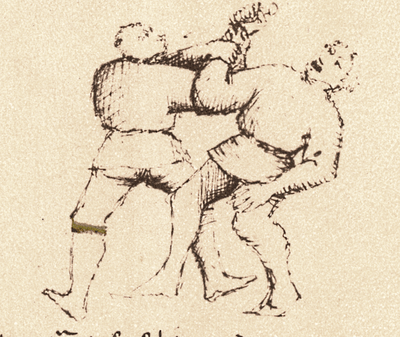

[16] This is a good hold to practice, This is a finishing move and it is a good way to hold someone, because they cannot defend themselves. For the counter, the one who is being held should move as quickly as he can over to a wall or a post and drive himself backwards against it so that the man holding him breaks his head or his back against the aforementioned wall or post. |

By the joint, thought and mind, the capturing is called Outsider. |

[7v-c] ¶ Questo si'e un partido, e si'e una strania presa a tegner uno a tal modo che non se po defendere. Lo contrario si'e che quello che tegnudo, vada al piu tosto che'l po apresso'l muro, o altro ligname e volti se per modo ch'ello faza a choluii che'lo tene romper la testa e la schena in lo ditto muro overo ligname. |

[5a-e] Questa si e de'concordia strania presa |

[41v-a] ¶ Concordi concepta animo, prensura vocatur | |||

[17] I will strike you so hard in the groin This student strikes his opponent with a knee to the groin to gain advantage in order to throw him to the ground. To make the counter, when your opponent comes in quickly to strike you in the groin with his knee, seize his right leg under the knee with your right hand, and throw him to the ground. |

In this way, <I> myself would destroy your testicles with a hard |

[7v-d] ¶ Questo fere lo compagno cum lo zinochio in gli chogloni per avere piu avantazo di sbaterlo in terra. Lo contrario si'e che subito che lo compagno tra cum lo zinochio per ferirlo in gli cogloni, ch'elle debia cum la man dritta piglare la ditta gamba sotto lo zinochio e sbaterlo in terra. |

[5a-f] In li chogiuni ti faro tal percossa |

||||

[18] I'll give you so much pain and suffering to your nose If you seize me with both your arms underneath mine, I will strike with both my hands into your face. And even if you were well armored this would still make you let go. The counter of this play is to place your right hand under the left elbow of your opponent and push hard upwards, and you will be able to free yourself. |

I will redouble so many[88] pains which your nose is suffering |

[8r-a] ¶ Per ço che tu me ha piglado cum li toi brazi de sotto gli miei, trambe le mie man te fiermo in lo volto. E si tu fossi ben armado, cum questo zogho io saria lassado. Lo contrario di questo zogho si'e che si lo scolaro che ven inzuriado del çugadore in lo volto, metta se la sua man dritta sotto, lo cubito del zugadore çoe del brazo sinistro e pença lu forte, e'lu scolar rimara in sua liberta. |

[5b-a] In tuo naso faço tanta pena e doia |

[42r-a] ¶ Tot tibi congemino naso patiente dolores | |||

[19] No doubt about it, with this move I will free myself This shows how I make the counter to the thirteenth play [18]. As you can see his hands have been removed from my face. And from this hold, if I fail to throw him to the ground I will be worthy of your disdain. [In the Getty, the master grabs the scholar's right elbow rather than his left wrist.] |

I set up your limbs using a similar capturing (and so we demonstrate). [In the Paris, the Master is missing his crown.] |

[8r-b] ¶ Lo contrario del ·ⅩⅢ· io fazo. Le soy mani del mio volto sono partide. E per lo modo ch'io lo preso e si lo tegno, Si ello non va in terra prendero grande disdegno. |

[5b-b] El'e vero che de tal presa t'o lassato |

||||

[20] I will hurt you under your chin so badly If you come to grips with both your arms underneath your opponent's, then you can attack his face as you see depicted, especially if his face is not protected. You can also transition from here into the third play of grappling. |

And I drag many pains to you below your chin, |

[8r-c] ¶ Se tu pigli uno cum trambi li toii braci de sotto va cum le toii mane al suo volto segondo vedi che io fazo, e mazor mente s'ello e discoverto lo volto. Anchora puo tu vegnire in lo terzo zogho de Abraçare. |

[5b-c] Soto el'mento ti faço doia e greveza |

||||

[21] With your hands in my face you can cause me trouble, This is the counter to the fourteenth play [20], and to any other play where my opponent has his hands in my face while grappling with me. If his face is unprotected, I push my thumbs into his eyes. If his face is protected, I push up under his elbow and quickly move to a presa or a ligadura. [In the Pisani Dossi, the Master is missing his crown.] |

Here, by this twin play, you press the face with the hand. [In the Paris, the Master is missing his crown.] |

[8r-d] ¶ Io son lo contrario dello ⅩⅢⅠ· zogho e de zaschuno che le mane me mette al volto in fatto d'abrazare. Li dedi polisi io metto in l'ochi soii s'il volto suo i'truovo discoperto. E si ello e coperto'l volto, io gli do volta al cubito o presa o ligadura io fazo subito. |

[5b-d] Cum le man al volto tu me fa impaço |

Images |

Images |

Completed Translation (from the Getty and PD) |

Draf Translation (from the Paris) |

Morgan Transcription |

Getty Transcription |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[1] With a short staff I bind your neck, See how with a short staff I hold you bound by your neck. And from here if I wish to throw you to the ground I will have little trouble doing so. And if I choose to do worse to you I can keep this strong bind applied. And you will not be able to counter this play. |

[8v-a] ¶ Guarda che cum uno bastonçello io te tegno per lo collo ligado. E in terra ti voglio butare, pocha briga per questo ho a fare ¶ che se io te volesse peço trattare in la forte ligadura te faria entrare. E llo contrario non mi porissi fare. |

[5b-e] Cum un bastoncello lo collo t'o ligato |

|||||

[2] If this short staff play does not put you on the ground, If you were well armored then I would prefer to make this play against you than the previous one. Now that I have caught you between your legs with the short staff, you are stuck riding it like a horse, but you won't be trapped like this long before I turn you upside down onto your back. [In the Getty, the Scholar steps between his opponent's legs.] |

[8v-b] ¶ S'tu fossi ben armado in questo zogo piu tosto te faria. Considerando che t'o preso cum uno bastonzello tra le gambe. Tu sta a cavallo e'pocho ti po durare che cum la schena ti faro versare. |

[5b-f] Se tu non va cum questo bastoncello in terra |

|||||

[3] I am the Student of the Sixth Remedy Master of the Daga, who counters in this way with his dagger. And it is in his honor that I make this cover with my short staff. And from here I will rise quickly to my feet and I will make the plays of my Master. And this cover that I have made with a short staff can also be done with a hood. And the counter to this move is the same counter shown by my Master [in the dagger section]. [Based on the description, the placement of this image is probably an error and it more likely belongs to the following play.] |

[8v-c] ¶ Del Sexto Re ch'e rimedio di daga e contra per questo modo cum sua daga di quello son Scolaro. E per suo honore fazo tal coverta cum questo bastonçello. E subito mi levo in pe, e fazo gli zoghi del mio magistro. Questo che fazo cum lo bastonçello io'l'faria cum un p capuzo. El contrario del mio magistro si e mio contrario. |

||||||

[4] I have taken this remedy from the Eighth Remedy Master of the Dagger, and I can defend myself armed only with this short staff. And having made this cover I rise to my feet, and I can then make all of the plays of my Master. And I could defend myself in this way equally well with a hood or a piece of rope. And the counter to this move is the same counter shown by my Master. [Based on the description, the placement of this image is probably an error and it more likely belongs to the previous play.] |

[8v-d] ¶ Del octavo Re ch'e rimedio io fazo questo zogho E pur cum questo bastonzello fazo mia deffesa. E fatta la coverta io in pe mi drizzo. E li zoghi del mio magistro posso fare. E cum uno capuzo overo una corda te faria altretale. El contrario ch'e del mio magistro, si'e mio. |

{{SUBST:Fiore de'i Liberi/Sword vs. Dagger}}

{{SUBST:Fiore de'i Liberi/Sword in One Hand}}

{{SUBST:Fiore de'i Liberi/Sword vs. Spear}}

{{SUBST:Fiore de'i Liberi/Sword in Armor}}

{{SUBST:Fiore de'i Liberi/Poleaxe}}

{{SUBST:Fiore de'i Liberi/Spear}}

{{SUBST:Fiore de'i Liberi/Spear vs. Other Weapons}}

- ↑ Fiore Furlan means “Fiore the Friulian”, i.e. “Fiore of Friuli”. Friuli is an area in the extreme north-eastern corner of Italy, to the north-east of Venice, with Austria to the north and Slovenia to the east.

- ↑ Fiore the Friulian, of the free knights of Premariacco is usually referred to as Fiore dei Liberi (one translation would be “Fiore of the Free Knights”). We don’t know for sure whether “Fiore” (“Flower”) was his real name or a pen-name. “Fiore” certainly existed as a real name for a man in medieval Italy—it was a common unisex medieval Christian name derived from the Italian word for flower. Alternately “Flower of the Free Knights” also makes sense, meaning “The best of the free knights.” As to the question of whether “Liberi” is a family name or simply refers to the class of free knights, since the word is spelled in Fiore’s manuscripts, in Getty (“liberi”), Pisani-Dossi (“liberorum”) and Morgan (“liberi”), with a small “l” for “liberi”, I am translating this word not as a family name (“Liberi”) but as “free knights” (“milites liberi”).

- ↑ I have translated the entire Prologue into the first person “I”, rather than use the third person “Fiore”, so as to make it more friendly and direct to read.

- ↑ “Armiçare” or “Armizare” means the art of armed fighting or fighting with weapons. Fiore refers to his martial art as both “L’Arte d’Armizare” (Art of Armed Combat) and “La Scientia d’Armizare” (Science of Armed Combat). However, you should note that the words Arte and Scientia do not necessarily have their modern meanings. Arte may mean simply “skill” and the word “Scientia” may mean simply “knowledge”. Thus “the skill and knowledge of armed fighting”.

- ↑ Fiore is comparing the two kinds of fighting: sport/tournament (“combatter a sbarra”—“in the lists”) and mortal combat (“combatter adoltrança”—“to the death”). To fight “in the lists” was not however without serious risks of injury and/or death. Medieval knights took these tournaments very seriously as matters of honor, and renown was won and lost in such events. Fiore also appears to include duels of honor in his term “in sbara”. The fights he describes below include duels of honor.

- ↑ “tempere di ferri” means literally “the tempering of iron”. I have translated this liberally to “the construction of weapons” to more clearly reflect what I believe Fiore means here. See also fn. 37 below.

- ↑ It is important to remember that when Fiore refers to “Germans” and “Italians” he is referring to language/cultures and not referring to nation states. Neither “Germany” nor “Italy” existed at this time.

- ↑ Here is where Fiore names his martial art: “Arte d’Armizare”—“the Art of Armed Combat”.

- ↑ “in Sbarra” means literally “at the barriers”. In many medieval sporting events the combatants would fight with longswords or spears over a fence (barrier). This prevented the combatants from closing to grapple and thus tested their long range fighting skills. Fiore uses this term to refer to sporting events as opposed to fights to the death. Fiore tells us he was asked to teach for both.

- ↑ Piero del Verde (Getty), Piero dal Verde (Morgan), (lit. “Peter of the Green”), also named elsewhere as Paolo del Verde, Pietro del Verde and Pietro von Grünen, was a recorded German condottiero (mercenary) captain who died in 1384. His birth date is not known.

- ↑ Piero della Corona (Getty), Piero dalla Corona (Morgan) (lit “Peter of the Crown”), also named elsewhere as Pietro della Corona, Peter Kornwald, Pietro Cornuald, was another recorded German condottiero (mercenary) captain who died in 1391. His birth date is not known.

- ↑ Perosa/Perusia is now known as Perugia. It is situated about 100 miles north of Rome. The date of this duel is estimated between 1379 and 1381, when both knights are recorded as present in this region.

- ↑ Nicolo Voriçilino (Getty), Nicholo Vnriçilino (Morgan), is named elsewhere variously as Niccolo Voricilino, Niccolo Borialino, Niccolo Waizilino, Nikolaus Weiss , and Nicholas von Urslingen. There is no historical record, however, as to who this person was.

- ↑ Niccolo “Inghileso” (Getty and Morgan) translates as Nicholas “the Englishman”. However, there is no historical record as to who this person was.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 The city of Imola is about 120 miles south-west of Venice.

- ↑ Galeazzo de Capitani da Grimello da Mantova (Getty), Galeaz delli capitani de Grimello chiamado da Montoa (Morgan), also named Galeazzo de Mantova (eng. Mantua), Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli, and Galeazzo Gonzaga, was an Italian condottiero captain who died in 1406. We do not know his birth. Significantly Galeazzo fought two duels against Buzichardo de Fraza, also known as Boucicault, one in 1395 that was stopped by the supervising Lord where the parties were evenly matched, and one in 1406, where Galeazzo defeated Boucicault. To be able to say that one of his students defeated the mighty Boucicault in single combat would have looked very impressive on Fiore’s resume.

- ↑ Buçichardo de Fraca (Getty), Briçichardo de Franza (Morgan), named elsewhere as Buzichardo de Fraza, also known as Boucicault, or Jean II Le Maingre (1364-1421), was a French military general who was honored by King Charles VI as Marshall of France in 1391, and was a knight of great renown for his military skill, and his strength and athleticism in single combat. Apparently at a dinner at which both Boucicault and Galeazzo were present, Boucicault insulted Italians claiming he could beat any Italian knight in single combat. Galeazzo accepted the challenge, and the two fought with spears on foot in 1395, a duel that was a draw, when it was halted by the supervising lord, Francesco Gonzaga, Lord of Mantova. The enmity was not forgotten however, and the two repeated their duel in 1406, this time on horseback with lances, at which time Boucicault was defeated by Galeazzo.

- ↑ Padova (Padua) is about 20 miles west of Venice.

- ↑ A squire was a nobleman who was trained and skilled in the knightly arts, but who had not yet been knighted. Note the fighting abilities of the squire were not necessarily any different from the knight proper.

- ↑ Lancillotto da Becharia de Pavia (Getty), Lanzilotto de Boecharia da Pavia (Morgan), also called Lancilotto Beccaria was an Italian condottiero captain who died in 1418. We do not know his birthdate.

- ↑ Notice that although these are “sporting events” they were using real spears.

- ↑ Baldassarro (Getty), Baldesar (Morgan) refers to the German knight Balthasar von Braunschweig-Grubenhagen (1336-1385)

- ↑ Gioanino de Bavo (Getty), Zohanni de Baio (Morgan), also named Giovannino da Baio likely refers to the French knight Jean de Bayeux, who is recorded as being in the area at this time.

- ↑ The city of Pavia is 20 miles south of Milan.

- ↑ The identity of the German squire named Sram (Getty and Morgan), Schraam, or Schramm, is not known.

- ↑ Açço da Castell Barcho (Getty), Azo da Castelbarcho (Morgan), refers to Azzone Francesco di Castelbarco, an Italian condottiero captain who died in 1410. We do not know his birthdate.

- ↑ Çuanne di Ordelaffi (Getty), Zohanni di li Ordelaffig (Morgan) refers to Giovanni Ordelaffi, an Italian condottiero captain (1355-1399).

- ↑ Jacomo di Boson (Getty), Jacomo de Besen (Morgan), or Giacomo da Boson, likely refers to the German nobleman Jakob von Bozen.

- ↑ These were duels of honor, and were taken very seriously in these times.

- ↑ Fiore actually says that the swords are “di taglo e di punta” meaning literally “for cutting and thrusting”, or “sharp edged and pointed”.

- ↑ A “çuparello darmare” or “zuparello d’armare” is an arming jacket, that is, a cloth padded jacket worn underneath armour as a foundation garment.

- ↑ We don’t know if this means he won all five duels, or simply acquitted himself well. But he says he was not injured.

- ↑ In addition to “L’Arte d’Armizare” (the art of armed fighting), L’Arte del Combattere (the art of combat) is a second name Fiore gives to his art.

- ↑ If they never lost and always acquitted themselves honorably, then presumably they always either won or drew.

- ↑ Letter scratched out, possibly "n".

- ↑ The word is decretali (Decretals). A Decretal is a Papal Constitution in letter form, i.e., a written decree from a Pope stating the Church’s legal position on a specific legal or moral issue.

- ↑ Scientia d’Armizare is Fiore’s other term for his Arte d’Armizare. Scientia means science or knowledge. Thus Scientia d’Armizare could translate as “Knowledge of Armed Combat” or “Science of Armed Combat.”

- ↑ Fiore writes di ferri e di tempere which literally means “of iron and of tempering”, i.e., hardening of steel. However, since Fiore’s manuscript clearly does not show anything about blacksmithing or how weapons are actually made, this literal translation does not serve me. Thus I changed it to “weapons and their applications”.

- ↑ It is not clear here whether Fiore is saying he actually consulted with Niccolo III of Este prior to the creation of the book, that Niccolo indicated how he wants the book laid out, and that Fiore has decided to lay it out exactly as Niccolo has asked for it to be done, or simply that he knows what Niccolo likes.

- ↑ I translate Abrazare or Abracare as “grappling” rather than “wrestling”, since wrestling suggests ground-fighting, and there is no ground fighting in Fiore’s system.

- ↑ The word solaço means “pleasure”. Fiore means grappling for sport. Fiore is distinguishing between fighting for fun and fighting to the death.

- ↑ The expression da ira means “in anger”. Fiore is contrasting this with grappling for fun. Thus I have translated ira as “earnest”.

- ↑ Both ingano and falsita mean “deceit”. It is not clear why Fiore uses both, but any difference in these two words are lost in translation. I therefore translated ingano as “cunning” so that there were still three words as in the original.

- ↑ The word crudelita means “cruelty”. I prefer the word “viciousness” here.

- ↑ The taking of guards would suggest he has some training and thus some skill in grappling.

- ↑ The words are prese (“holds”, “grips” or grapples”) and ligadure (“locks” or “binds”).

- ↑ inle femine sottol mento means literally “in the soft part below the chin”. Fiore means the throat/larynx.

- ↑ The fianchi, the “flanks”, are the unprotected (“soft”) areas of the side of the torso, below the lower ribs but above the hips.

- ↑ Viii chose means literally “eight things”.

- ↑ Note: attributes numbers 4 and 8 seem to be the same attribute. This is noted especially because in the earlier Pisani Dossi manuscript Fiore tells us there are seven attributes (not eight as here in the Getty). Roture (“breaking”), Romper (“tearing apart”) and Dislogar (“dislocating”) arms and legs appear here to be duplicative.

- ↑ Frontale means the front of the head, i.e., the forehead. Elsewhere Fiore comments that this guard is often named (by others) as Posta Corona (“The Crown Guard”), the “crown” referring to the top of the head.

- ↑ Dredo means “Behind” but in this context it translates better as “after”, be cause we can see from the way the manuscript is laid out that the remedies are shown first, and the counters later.

- ↑ The “Special” Remedy that comes at the very end, that Fiore is referring to is a Counter to the Counter, which, as you will see below, Fiore calls Contra-contrario or the “Counter-counter”.

- ↑ Written at the end of the line, with a mark indicating the insertion point.

- ↑ Literally “Masters of the Battle” or “Masters of the Fight”.

- ↑ Fiore just calls him the “Second Master”, but Fiore means by this that he is the Second Master of Battle.

- ↑ Fiore here calls them Zugadori (Players) rather than Scolari (Students), but that is confusing, because the way the manuscript is visually structured, the students of the Remedy Master who wear the golden garter are named Scolari (Students), not Zugadori (Players). The Zugadori are drawn without any garter at all. Therefore here I translate zugadori as Students (Scolari), so as to be consistent with what is drawn.

- ↑ Divisa means literally “device” but also refers to a uniform or insignia that marks a person's rank or position. I have chosen to translate the word divisa as “garter”. In the PD, Fiore refers to the golden ribbon worn around one leg by the Students as a lista doro. A lista is a strip of material, like a ribbon, garter or scarf. Doro means D’oro - “of gold.”

- ↑ Fiore actually writes “The Remedy Master and his plays, but since the Counter Master also defects the Remedy Master’s students, who show all the plays, I decided to translate it as above.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Should be "et e"?

- ↑ I’ve rearranged the sentences here to make my translation clearer. Thus the red and blue letters in the original don’t match up at all in my translation.

- ↑ Fiore actually says libro (“book”), but I’ve changed it to “system”.

- ↑ The word Rubriche means writing in red ink. I chose to translate this word simply as “text”.

- ↑ "e di maistri" appears twice in a row in the text, but isn't struck out like other duplications.

- ↑ Corrected from "a"(?) to "i".

- ↑ This was translated from an Italian translation of the Latin, and needs to be checked against the original language to be promoted to B-class.

- ↑ The full statement, as given by Philippo di Vadi, is "It is not meet that the Imperial Majesty be honored in arms alone, but it is necessary also that it be armored in sacred laws". (El non bixogna solo la maestà inperiale essere honorata di arme ma ancora è necesario epsa sia armata de le sacre legge.)

- ↑ Word disrupted by a lynx.

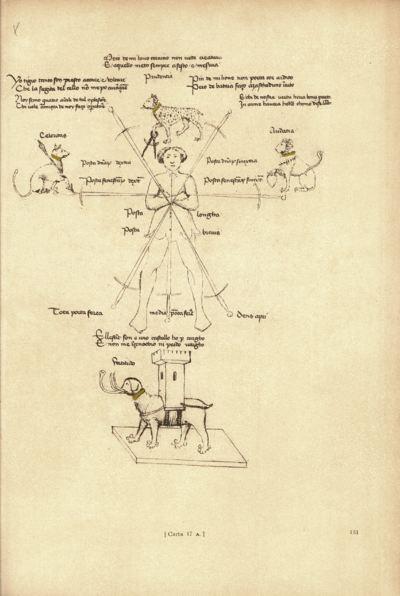

- ↑ “Lovo cerviero” (Lupo Cerviere) translates literally as “sharp-eyed wolf”. Fiore means the Eurasian Lynx that was said to have not only astonishing eyesight and the ability to see in the dark, but also the ability to see around corners and even see into the future. The choice of the Lynx to represent the ability to “read” the fight and proceed carefully is thus meaningful. The lynx has been used to symbolize the search for knowledge, or the search for the truth. In 1603, for example, the Accademia dei Lincei (Academy of the Lynxes) was founded in Italy, dedicated to providing a sharp and penetrating insight into science and nature. For its emblem, the academy chose the lynx, and its symbol, the lynx passant is remarkably similar to Fiore’s lynx. The great Galileo himself was inducted into the Accademia dei Lincei in 1609, and published papers under the Accademia dei Lincei name. In fact, after joining the Accademia dei Lincei, Gailieo thereafter signed his name Galileo Galilei Linceo (“Galileo the Lynx”).

- ↑ “A sesto e misura” - Fiore’s Lynx represents the intelligence and scientific application of knowledge. Hence it proceeds literally holding a “sesta” which is a pair of compasses or dividers. Note “sesta” is the pair of dividers, used for drawing circles and arcs and for measuring distance, not a nautical compass showing north south east west. A “misura” is a measure or rule, also used for measuring and drawing. The symbol of freemasonry is the “compass and square” (the square being a type of rule, namely two rules at right angles to each other). “A misura” means “with measure”, i.e. carefully. See, for example, Compass-and-straightedge construction.

- ↑ Fiore’s Tigro is not the black and orange striped tiger (cat family), but is a mythical creature from the medieval Bestiaries that resembles a giant wolfhound (dog family). The tiny mouse-like creature drawn in the Getty does not do justice to this mighty mythical Tiger that was said to be as big as a horse and was attributed incredible speed. There is a most beautiful painting of a medieval Tiger in the Aberdeen Bestiary.

- ↑ “la sagitta del cielo” means literally “the arrow from the sky”. Fiore means of course a bolt of lightning.

- ↑ “Avanzare” means to excel or surpass. I understand Fiore to be saying that the Tiger is faster than lightning.

- ↑ “Ne perdo vargo” means literally “I do not lose my way”. From the Bestiaries however we understand that what the Elephant never does is fall over. In the Bestiaries we are told the Elephant has no knees and if it once lies down can never get up again. Thus Fiore’s Elephant stands for stability and sure-footedness. The Aberdeen Bestiary reads as follows: “[Of the elephant] ... no larger animal is seen. The Persians and Indians, carried in wooden towers on their backs, fight with javelins as from a wall. ...The elephant has this characteristic: if it falls down, it cannot rise. But it falls when it leans on a tree in order to sleep, for it has no joints in its knees. A hunter cuts part of the way through the tree, so that when the elephant leans against it, elephant and tree will fall together.”

- ↑ The bottom of the page, including the elephant verse, has been cut off.

- ↑ Added later: "pro".

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet tu".

- ↑ It looks like the period maybe was changed to a slash/comma.

- ↑ Nec sine is an emphatic, not a negation.

- ↑ Phrase doubled.

- ↑ Apposui is clearly “I served up,” but with the convention that the captions are spoken by the wearer of the crown or garter, this makes little sense (as the palms are in the face of that person). Further, the Pisani Dossi text reverses the speaker.

- ↑ Added later: "+ ut".

- ↑ Added later: "+ posuj".

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet ego".

- ↑ Added later: "situ".

- ↑ Added later: "& mergit".

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet ego".

- ↑ Tot: so many, such a number.

- ↑ Added later: "tu scilicet".

- ↑ The accusatives [direct objects] are unusual in both of these lines

- ↑ There are no personal pronouns indicating whose eyes are getting injured in this couplet. Only the second person verb in the first line indicates whose eyes are getting damaged.

- ↑ "senza" appears twice, but neither is struck out.

- ↑ "de" appears twice, but neither is struck out.

- ↑ cautus (from cavere) is a common term in Roman jurist texts, where it means security in the sense of assurance or collateral

- ↑ Maybe "laevo".

- ↑ Possibly a scribal error—the first sentence seems to be missing a “me” and the second has one it doesn’t need.

- ↑ The illustration clearly shows a thrust to the arm, not the shoulder.

- ↑ Could be “praesto”, Latin adv. “ready, available” or Italian “presto”.

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet occidam"

- ↑ The character ꝑ (a p with a stroke through the descender) would indicate that it should be read as per, but since romperer isn't a word and the stroke is much shorter than usual, I think it was an error and the scribe stopped writing it as soon as he realized. I have thus transcribed it as a normal p.

- ↑ Alternative with accusatives in opposite order: “I would seize the arm(s) in front suddenly / <I> the strong one would bring the dagger around in a violent whirling motion close by the elbow.”

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet ego".

- ↑ Interestingly, this page appears to be dirty and damaged; the recto looks like it’s warped from water damage. The next several pages also show warping; the art quality has also declined substantially.

- ↑ Or "backhand cover"

- ↑ Or "of the backhand cover"

- ↑ Or "reverse cover"

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet ego".

- ↑ This page has lots of dirt smudges, drips, and stains; some—to the left of the combatants in the upper register, and just below the verse in the lower—look like they might be handwritten smudges, but without clear meaning.

- ↑ Denodare appears to be a technical term for breaking or dislocating limbs; appears only in Ducange.

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet revolutum".

- ↑ Or "Master's reverse cover"

- ↑ Or "with the reverse cover"

- ↑ Added later: "ego s."

- ↑ Demittere mentem is recorded (by Bantam dictionary) as an idiom meaning “to lose heart”. Possibly mente sedebit is referencing this, in a pun (e.g., demittere in the sense of depose, and sedeo in the sense of hold court).

- ↑ There is an unreadable marking here.

- ↑ Added later: "ego scilicet".

- ↑ Added later: "scilicet ego".

- ↑ This looks like it may have originally said “veter” but was corrected to “vetes” (e.g. from first person present passive to second active present).

- ↑ See Capelli 285; this can be read as either prope (near) or proprie (specifically).

- ↑ Literally “the two palms”.

- ↑ Should be "defendam".