|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Francesco Fernando Alfieri"

| Line 2,001: | Line 2,001: | ||

| source link = https://sword.school/articles/la-bandiera/ | | source link = https://sword.school/articles/la-bandiera/ | ||

| source title= The School of the Sword | | source title= The School of the Sword | ||

| + | | license = noncommercial | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{sourcebox | ||

| + | | work = Translation (Pike) | ||

| + | | authors = [[Piermarco Terminiello]] | ||

| + | | source link = | ||

| + | | source title= Private communication | ||

| license = noncommercial | | license = noncommercial | ||

}} | }} | ||

Revision as of 12:26, 18 November 2020

| Francesco Fernando Alfieri | |

|---|---|

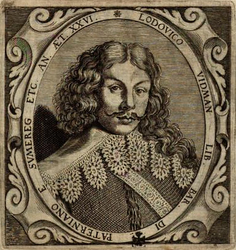

Portrait from 1640 | |

| Born | 16th century (?) |

| Died | 17th century |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) |

|

Francesco Fernando Alfieri was a 17th century Italian fencing master. He was Master of Arms of the Accademia Delia in his native Padua, most likely from 1632 until some point in the mid 1650s,[1] his predecessors being fellow Paudans: Bartolomeo Tagliaferro and Gaspare Magnanino. While not the first military academy in the Italian peninsula, it is recorded as the first state academy, with generous support from the city's coffers. The academy appointed Masters in only three disciplines: fencing, equitation, and mathematics, famously turning down Galileo Galilei for the position of professor of mathematics in 1610.

Founded in 1608, the Accademia Delia served as an elite finishing school for the sons of Paduan nobility, a military academy for future cavalry officers, continuing in this form until 1801. The academy's statutes provided for a maximum of sixty students, but in practice there were often fewer. 1632, the year Alfieri began his tenure, bore witness to a difficult period in Padua. In 1631 the city had suffered a terrible epidemic, bringing its population from 30,000 to a mere 13,000, with many of the academy's students losing their lives.

Nevertheless the academy occupied a position of considerable prestige in Paduan society, and in the entire Veneto region. For example on 18 April 1638, in the year Alfieri published La Bandiera, the academy hosted an extravagant festival, with contests and displays of fencing and jousting. This was watched by thousands of spectators, and concluded with a mass in the church of Santa Giustina, with a musical score composed for the occasion by Claudio Monteverdi.

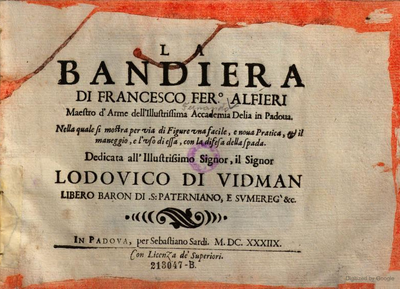

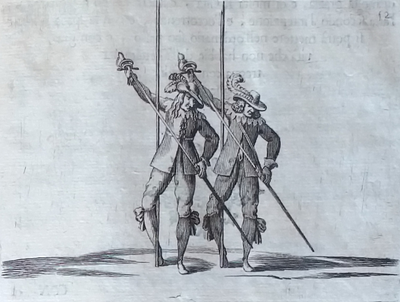

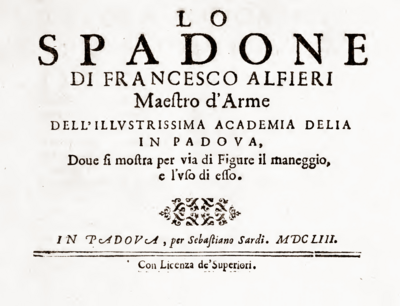

In 1638, Alfieri published a treatise on flag drill entitled La Bandiera ("The Banner"). This was followed in 1640 by La Scherma ("On Fencing"), in which he treats the use of the rapier. Not content with these works, in 1641 he released La Picca ("The Pike"), which not only covers pike drill, but also includes a complete reprint of La Bandiera (complete with title page dated 1638). His treatise on rapier seems to have been especially popular, as it was reprinted in 1646 and then received a new edition in 1653 titled L’arte di ben maneggiare la spada ("The Art of Handling the Sword Well"), which not only includes the entirety of the 1640 edition, but also adds a concluding section on the spadone.

Alfieri dedicates his La Bandiera and La Picca to Lodovico Vidman, whom he indicates was his former student and patron, with L’arte di ben maneggiare la spada dedicated to Lodovico's brother Martino (La Scherma being dedicated to the students at the Accademia Delia in general). The Vidman (or Widmann) family were an extremely wealthy merchant family, originally from Carinthia in present-day Austria, but settled in Venice. Generous patrons of the arts, in the course of the first half of the seventeenth century they were ennobled first by the Holy Roman Emperor, then by the Venetian Senate.

Treatise

Illustrations |

Draft Translation |

Transcription (1638) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The Flag by Francesco Ferdinando Alfieri, Master of Arms at the Illustrious Academy Delia of Padua In which it is demonstrated by way of figures an easy and new method, its handling, and its use with the defence of the sword. Dedicated to the Most Illustrious Sir, Sir Lodovico di Vidman Free Baron of San Paterniano, and Sommeregg, etc. In Padua, printed by Sebastiano Sardi. MDCXXXIIX. With Permission from the Authorities |

[i] LA BANDIERA DI FRANCESCO FER.º ALFIERI Maestro d'Arme dellʼIllustrissima Accademia Delia in Padoua. Nella quale si mostra per via di Figure una facile, e nova Practica, & il maneggio, e lʼuso di essa, con la difesa della spada. Dedicata allʼIllustrissimo Signor, il Signor LODOVICO DI VIDMAN LIBERO BARON DI .S: PATERNIANO, E SUMEREG` &c. IN PADOUA, per Sebastiano Sardi. M. DC. XXXIIX. Con Licenza de' Superiori. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To the Most Illustrious Sir Most Excellent and Honourable Sir and Patron Lodovico Conte di Vidman The benevolences I receive from Your Excellency daily are so frequent, and so generous, that considering what gratitude could be expected from my feeble, but above all devoted, service, I conceived to illustrate my obligations succinctly in these sheets of paper. Here, Your Excellency, is the fruit of my labours, dedicated in every respect to your generous name; such that under your protection it might acquire the esteem, that the little acumen of the author would be unable to grant it. You will see, Your Most Illustrious Excellency, the art that you deigned to learn, honouring my discipline. I have effortlessly persuaded myself that it would not displease you, to see printed this pastime which you occasionally enjoyed to practice. Nonetheless I am aware of the scarce value of my gift, but your magnanimous brilliance has emboldened me. My soul is overflowing with obeisant reverence, and Your Most Illustrious Excellency of benignity, to you I most humbly bow. |

[iii] ALL’ ILLVSTRISS.MO SIG. Sig. e Padron Colendiss.mo il Signor LODOVICO CONTE DI VIDMAN. SOn tante, e cosi grandi le grazie, che ogni giorno ricevo da V.S. Illustrissima, che pensando à quella gratitudine, che si può aspettare dalla mia debole ma sopra ogn’altra devota seruitù, mi sono ingegnato di figurare le mie obligazioni competidiosamente in queste carte. Ecco Illustrisimo Signore le primizie delle mie fadighe dedicate per ogni rispetto al suo generoso nome; e perche acquistino sotto la sua protezione quella stima, che non le hà potuta dare il basso ingegno dell’autore; Vedrà V.S. Illustrisima [iv] quell’arte, che s’è degnata d’apprendere coll’onorar la mia disciplina, e però mi son agevolmente per suaso che non le sia per dispiacere di vedere impresso ciò che per passatempo l’è piaciuto tal volta d’ esercitare, conosco tuttavia il poco valore di questo mio dono, ma il suo magnanimo genio m’hà fatto ardito: Il mio animo è colmo d’ossequiosa riverenza, e V.S. Illustrissima di benignità, ed umilissimamente me l’ inchino. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In Padua the 6 th day of September M.DC.XXXIIX. Your Most Illustrious Excellency Your Most Humble and Most Obliged Servant, Francesco Ferdinando Alfieri. |

Di Padova il dì 6. Settembre M. DC. XXXIIX.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To the reader Reader I present to you my flag. If it is not handled according to your spirit, blame the fact that the task was beyond my abilities. The condition of this century brings such liberty, that everybody burdens the printing presses, and I too have allowed myself to be taken by this custom. I am sure you will tell me I have not dusted off many bookshelves, and I will reply that my books have been experience and practice, which I leave you the image thereof. That which I have in my mind to show you, if it does not seem completely new to you, neither is it trivial. Every master of arms professes some knowledge of it, few have written treatises and nobody up until now has condensed this art into the form that you see. I desire nothing more than to please you, and to benefit you. If I achieve this goal, and you also learn that which you seek, I nonetheless seek your pardon; and perhaps in short I will bring out a new treatise on all aspects of fencing, which will please you even more. Finally it is just to admit that he who labours for others is always worthy of being commended. |

[v] A CHI LEGGE. LEttore vi si presenta la mia bandiera, se non è maneggiata secondo il vostro spirito, datene la colpa allʼaffetto che è stato maggiore del mio sapere. La condizione di questo secolo porta seco tale libertà, tutti affadigano le stampe, ancorʼio mis son lassato vincere dal costume. Son cherto che mi direte che non hò spolverate molte scanzie, ed io vi risponderò, che i miei libri sono stati lʼesperienca, e lʼesercizio, e che lascio à voi altri lo speculare, quello che hò havuto nel pensiero di mostrarvi se non vi parrà in tutto nuovo, non è manco triviale. Ogni maestro dʼArme ne professa qualche notizia, pochi ne hanno trattato e nissuno fin quì hà ridotta questʼarte allʼordine che voi ve- [vi] dete; Io non desidero che di piacervi; e di giovarvi, se conseguirò questo mio fine, e voi anco acquistarete quel tanto che ricercate, voglio però che mi scusiate, e forse in breve con un trattato nuovo di tutte le parti della Scherma vi farò di maggior gusto, e poi finalmente è giustizia il confessare che sempre mai è degno dʼesser commendato chi per altri sʼaffadiga. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[vii-viii] Tavola de capitoli

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Flag by Francesco Ferdinando Alfieri From what I have been able to learn, from those few books that have come to my hands, from the discourses of great men, and from a long and uncommon experience, there is nothing in my judgement either more honourable or more necessary to a person of noble birth, than keeping their youth engaged in the practices that are useful to, and which help and adorn, the virtues of the soul. The antique and famous republics which will always serve as examples, and as stimuli to set on the path towards civic happiness, also prized virtue, skill, and agility, reputing as blessed those who were solemnly considered stronger and faster than others.[2] They were seen in the piazzas competing, some at wrestling, some launching the pole, they challenged themselves in races, they battered one another with the cestus, and at times by hurling discs or balls of wood, they put on show the gifts they had received from nature, enhanced through their art. These exercises were common into the early centuries of the Italic nation, and if they are never expressed with the pomp in which the inhabitants of the Peloponnese and Phrygia excelled, they have nonetheless been largely conserved up to the present age, as you can see every day principally in Tuscany, while other arts that were not practised in antiquity have been discovered. The practice of the flag will always be among the most commended, since it readies the foot, it renders the waist pliable; the hand becomes strong, the arm flexible. If we look to its origins, and to who was the first to unfurl it in an army we find in the holy scriptures that it was the great captain Moses,[3] he was followed first of all by the Assyrians, then the Egyptians followed the same example both with representations of bulls and other animals they held in veneration, and with numerous hieroglyphics alluding to victory, the pretexts and reasons for war, and to the strength and valour of their soldiers. Finally there is no people so barbaric, that it does not see its armies ordered and distinct under a particular standard. If we then turn to consider how useful and of what consequence it is in the management of war, although such a treatise would belong to a captain rather than to me, even I am clearly aware that the fortune and glory of war depends in large part on the flag, and that in truth via this instrument military discipline forms troops and centuriae, permits them to understand and execute commands, maintains them in order, and allows the parts of the army needed for victory to be deployed quickly and without confusion. Efforts should not be directed elsewhere, other than to seize flag. If it is lost it seems you must no longer fear resistance, there remains a confused and armed multitude without a guide, oppressed more by disorder than by iron. Thus we see that standards are the real trophies which render a warrior's valour immortal, and they are suspended in perpetual remembrance not only in private homes but also in public buildings and churches. Therefore the subject of the art I have chosen to demonstrate is itself a worthy one and perhaps inferior to no other. Some might wish to object, stating that the flag is employed in war, but not its art, to these I would reply with a question: is the ensign needed to defend the flag? One who would deny this hints at having a rare talent, and of being a few eggs short of a dozen.[4] If this is undeniable then, who is better able to defend the flag than one who knows how to handle it perfectly? Why is the pole armed if not intended to injure? To know how to wound it is necessary to practice the art, otherwise the flag serves only to entangle and envelop the hands, while it is horribly lost, holding it up being in vain. This does not occur in the hands of someone experienced, who when reduced to such extremes will have a ready solution appropriate to the situation. Emboldened by virtue one such as this will either rescue the flag from the enemy or will pursue it through vendetta. Therefore for those who understand this virtue, without need for further exposition, it will be a simple task to arrive at the mastery desired, observing the following figures which make clear the particulars that are difficult to express with words alone. |

[1] LA BANDIERA DI FRANCESCO FERNANDO ALFIERI. PEr quello, che hò potuto imparare, da quei pochi libri, che mi son venuti alle mani, dal discorso dʼhuomini grandi, e da una lunga, e non volgare esperienza, non è cosa al mio giudizio, ne più onorevole, ne più necessaria à persona di nobil nascita, quantoʼl tenerʼimpiegata la giovinezza neglʼesercizi che serveno, e dʼaiuto, e dʼornamento alle virtù dellʼanimo; LʼAntiche è fa- [2] mose Republiche le quali ci serviranno sempre dʼesempio, e di stimolo ad incominciarci per la via che ci conduce alla felicità civile hebbero in tanto pregio, e la destrezza e lʼagilità che reputavano beati quelli, che più forti, e più veloci de glʼaltri erano nelle loro solennità giudicati; Si vedeva nelle piazze contendere, altri alla Lotta, altri Lanciare il Palo, si cimentavano al corso, si battevano col Cesto, e talʼora collo scagliar rotelle, ò palle di legno facevano mostra di quei doni, che havevano ricevuti dalla Natura, e aggranditi coll'arte; Questi esercizi sono stati comuni ancor più dai primi secoli dall'Italica Nazione, e sebbene non si sono mai rappresentati con quella pompa nella quale eccellerono gli abitatori del Peloponneso, e della Frigia, si sono però sempre conservate in gran parte sino alla nostra età come si vede ogni dì principalmente nella Toscana, ed altri di più ne sono stati ritrovati che nella Antichità non furono un uso: lʼesercizio della Bandiera sarà sempre tra questi commendato imperochè in esso il piede si fa pronto, se rende pieghevole la vita, la mano acquista forza, e si discioglie il braccio; se riguardiamo la sua origine, e chi fosse il primiero che la spiegasse [3] negli esercizi, noi troviamo nelle sacre lettere che fu il gran Capitano Moisé, fu doppo innanzitutto da Siri, e seguirono l'istesso esempio glʼEgizi con figurarci dentro ora i Tori e gli animali che avevano in venerazione ed ora con diversi ieroglifici alludendo alla vittoria, al protesto e titolo della guerra, e alla forza e virtù de loro soldati, e finalmente non è gente così barbara che sotto una particolare Insegna non vede ordinate e distinte le sue milizie. Se dall'altro canto ci rivolgiamo a considerare di quanta utilità e di quanta conseguenza sia nel maneggio della guerra, benché simil trattato appartenga più tosto ad un capitano che a me, non e per questo che non conosca chiaramente ancorʼio, che dalla Bandiera non dependa in gran parte la fortuna e la gloria delle battaglie, e che ciò sia la verità la disciplina militare con questo mezzo forma le truppe e le centurie, le dispone ad intendere ed eseguire 'l comando, le ritiene in ordinanza, e viene ad impiegar a tempo e senza confusione quelle parti dell'esercito che sanno di bisogno per acquistarsi la vittoria. Tutti gli sforzi non vanno a ferire altrove che ad insignorirsi dellʼInsegna, se queste si perdono non par che più [4] si tema resistenza, rimane una confusa moltitudine armata senza guida, e più dal disordine che dal ferro oppressa, cosi vediamo che li stendardi sono i veri trofei con i quali si rende immortale i1 valore delle persone guerriere tenendoli sospesi a perpetua memoria non solo nelle case private ma nè pubblici palazzi e nellʼistessi tempi, talchè il soggetto dellʼarte che mi son preso a dimostrare è per se degno e forse a nissun altro inferiore. Né sia chi voglia oppormisi, con dir che nella guerra faceva di mestiero lʼ Insegna ma non già l'arte, perchè a questi tali risponderei con un quesito, ed è. Se allʼAlfiere sia necessario il difendere l'Insegna, chi lo negasse darebbe indizio d'avere una strana capacità, e d'esser tenero di sale, se non si può negare chi meglio lo potrà difendere di quello che la saprà perfettamente adoperare? Per quale cagione è armata l'asta se no nper ferire? e per saper ferire è necessario esercitarsi nellʼ arte, che altrimenti non ad altro serve che ad intrigare ed inviluppare le mani, e bruttamente si perde, si come inutilmente si sostiene;il che non accade ad uno sperimentato il quale venendo ridotto a simili estremità avrà pronti i partiti che saran- [5] no appropriati al caso. E fatto ardito dalla virtù, o salvarà lʼInsegna da nemici, o lʼaccompagnarà con la vendetta; a quelli dunque che senzʼaltri discorsi conoscano queste virtù sarà facile impresa l'arrivarne alla perfezione che si desidera, osservando le seguenti figure nelle quali si fanno palesi quelle particolarità che, difficilmente, si possono dichiarare con le parole. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

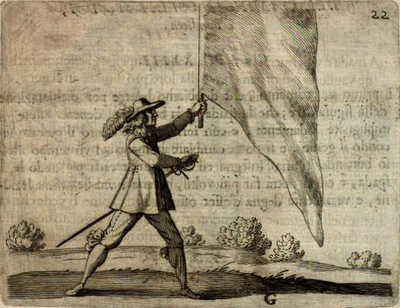

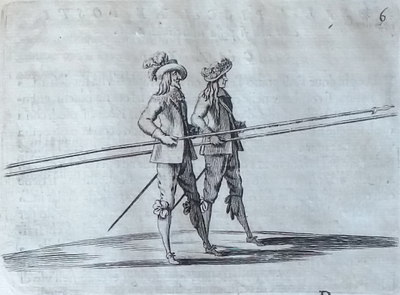

How the ensign or other person should present themselves with the standard Chapter I Wishing to proceed in an appropriate order, to arrive at a perfect understanding of this art, we must begin with its principles, since all of its perfections derive from these. In truth I confess that skill, strength and gracefulness are gifts dispensed by nature. Nonetheless with exercise and good discipline they can be acquired and developed. Therefore the movement of the ensign, or other person who wishes to handle the standard for pleasure, should be free, smooth, but also ordered and martial. You should take it with your right hand, as more noble, and passing it to your left you should gather the edges, and grasp them together with the haft, which resting on the arm, situates the flag at the breast as the figure shows. In this manner, without having to change hands and take two tempi, you can quickly unsheath the sword, and employ it as the occasion demands. |

[6] COME DEBBA LʼALFIERE, Ò ALTRA PERSONA presentarsi collʼInsegna. Cap. I. VOlendo con quellʼordine che si conviene venire alla perfetta notizia di questʼarte, bisogna essere osservante dei suoi principi, perché da essi come da sua origine tutte le perfezioni derivano.Confesso veramente che la destrezza e la forza e la leggiadria son grazie che vengon disponsate da natura, nulla di meno si possono in gran parte collʼesercizio. e con la buona disciplina, e accrescere ed acquistare. Sarà dunque il movimento dellʼAlfiere, o dʼaltra persona, che voglia per di porto maneggiare lʼInsegna, libero ma ben composto, grave, ma però militare. Si prenderà con la destra come più nobile, e portandola nella sinistra si devono raccorre i lembi, ed impugnarli con lʼasta che appongiandosi nel braccio, formarà la Bandiera il Seno, che dimostra la figura. In tal modo senzʼaver a cangiar mano e far due tempi, si può sfodrare speditamente la spada, e valersene a quellʼuso che dallʼoccasione si richiede. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

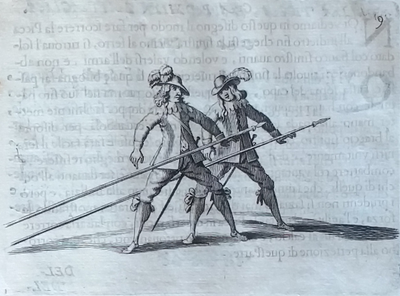

On hoisting the standard Chapter II To hoist the standard you take it with your right, lifting it so it unfolds, and assuming that the wind and location allow it, you find yourself in the posture seen in the picture. With your right foot, pole hand, and your waist gracefully in unison, you may salute the spectators before commencing your play, noting that for an army passing before a prince, general or other great personage it is an act of reverence to lower it to the ground waving it with a riverso.[5] |

[8] DELLʼINALBERARE LʼINSEGNA. CAP. II. PEr inalberare lʼInsegna si prenda con la destra e levandola in alto si dispiega, e supponendo che lo permetta il vento, e la capacità del luogo, ritrovandosi nella postura che si vede nel disegno potrà col piè destro, con la mano dellʼasta e col garbo della vita unitamente, riverire gli spettatori prima di mettersi in giuoco, avvertendo,. che nella milizia passando davanti al Principe, al Generale, o altro personaggio grande è atto di reverenza ondeggiandola di rivercio abbassandola sino a terra. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On the first method of beginning to handle the standard Chapter III This is the first lesson, in which we begin to walk. To attain the honour that is desired, the body should be somewhat bent and braced to take its force. The arm should be extended, strong and raised above the head. Passing with an ample but natural step, at the same time you will judiciously catch the wind with a mandritto, which unfurls and does not entangle the standard. This is followed by a riverso on the second pass, continuing in this manner as desired. You can also change hands, and the greatest skill is to throw the flag and take it in the air, which by its nature changes hands. |

[10] DEL MODO PRIMIERO di cominciare à maneggiar lʼInsegna. CAP. III. QUesta è la prima lezione con la quale si comincia il passeggio, e per conseguire quellʼonore che si brama, deve il corpo essere alquanto piegato e disposto alla forza. Il braccio sarà disteso, forte, ed innalzato sopra la testa, e muovendo il passo naturale ma generoso, formarà, ad un tempo di man dritto la velata pigliando con giudizio il vento, che distenda non inviluppi lʼinsegna; si replica doppo volgendo la man di rivescio il secondo giro, e si và in tal modo continuando secondo il pensiero. Si può ancora cangiar mano, ed allora è maggior destrezza il buttarla e prenderla nellʼaria, che naturalmente mutarla. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

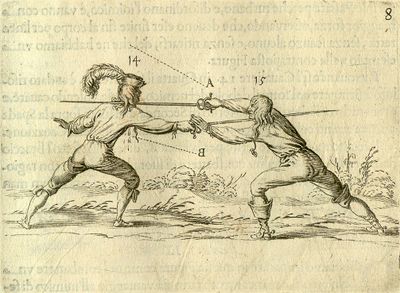

On thrusting with the standard Chapter IV All the lessons are arranged so that one is linked to the next. Here we learn how to deliver a thrust with the standard. This serves not only to demonstrate the skill and ability of the player, but could also be necessary to employ in war. The arm should be stretched out, and having flourished a circular mandritto with your right hand over your head, you should quickly push the flag forwards without wasting time, thrusting in quarta. After you should turn your arm and hand into seconda, and in unison with your left foot extend the blow, always taking into account the wind, and correct footing, to avoid misadventures, which detract from the merit of what you wish to accomplish. The same exercise can be done with the left hand which is all the more commendable, as by nature this member is usually weaker and less practised. |

[12] DEL TIRAR LE STOCATTE COLLʼ INSEGNA. CAP. IV. TUtte le lezioni sono talmente ordinate che lʼuna è concatenata collʼaltra. Qui, dobbiamo imparare come si tirino le stoccate collʼInsegna, e ciò non solo serve a mostrare la disposizione e la destrezza di chi giuoca, ma può darsi caso che faccia di mestiere praticarlo nella guerra. Si terrà dunque il braccio disteso, e data una velata in giro di man dritto per disopra della testa, si deve subito spingere avanti senza perder tempo la Bandiera, col tirar la stoccata di quarta, si. voltarà. doppo il braccio, e la mano in seconda, e collʼunire il piede stanco si slongarà parimenti la botta, avendo sempre riguardo al vento, al moto e alla giustezza del passo per isfuggire gli sconci, che levano il merito a quanto si viene ad operare. Si può ancora fare le medesime lezioni con la mano sinistra, il che è tanto più lodevole quanto suol essere questo membro per natura più debole e meno esercitato. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How to handle the flag with the hand reversed Chapter V This lesson is difficult but beautiful, and truly novel. You grip the shaft with the hand reversed, as it appears in the figure opposite, the arm must be somewhat gathered to help the wrist, which is encumbered by the weight. By taking smaller steps, with the movement of the hand rising from one flank to the other, the undulating volume of the flag is made to wave from one side to the other without confusion, while you interpose two or three passes under the leg or circle it behind the lower back, changing hands, however you prefer. |

[14] COME SI MANEGGI LA BANDIERA con la mano rivercia. CAP. V. QUesta lezione è difficile ma però bella, e veramente bizzarra. Sʼimpugna lʼasta con la mano rivercia, si fa come appare nella contrapposta figura, il braccio deve essere alquanto raccolto per aiutare il polso affatigato dal peso, e formando più ristretto il passo, al movimento della mano montante da un fianco allʼaltro ci faranno andeggiare senza confusione i tortuosi volumi dellʼInsegna, tramezzandovi due o tre sottogambe. o girandole per dietro le reni, e cambiando mano conforme a quello che maggiormente aggrada. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

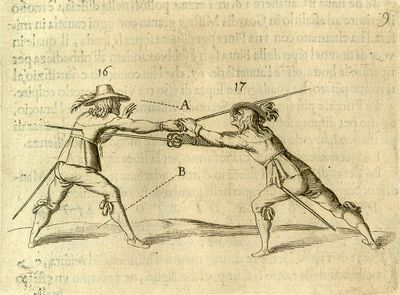

On passing the flag under the legs Chapter VI With the standard in motion, and wishing to perform the current lesson, the flag is launched into the air and caught with the hand reversed. Then with the arm turned and the body bent it is passed under the left leg towards the right. In the same motion it is then passed behind the lower back and taken with the left hand, and passed again under the right leg to the left. This can be repeated with either hand as your skill and vigour dictates. |

[16] A PASSARE L'INSEGNA sotto le gambe. CAP. VI. HAvendo lʼInsegna in moto, e volendo fare la presente lezione, si scaglia in aria e si ricoglie con la mano rivercia che voltata col braccio ed incurvato il corpo si fa passare sotto la gamba sinistra col girarla per la destra, ed allora tuttʼad un tempo si spiega di rivercio dietro le reni e si prende con la mano stanca facendosi ripassare sotto la destra gamba per la sinistra e questo si può con ambedue replicare per quanto lo comporta e la destrezza, e la lena. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

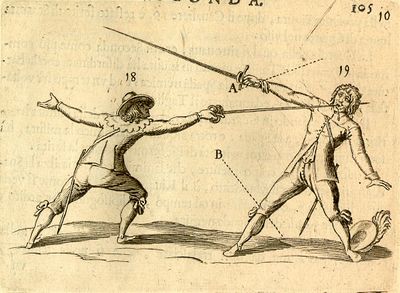

On launching the standard Chapter VII I know very well that the unusual always delights, and for this reason I have applied myself to collect and create the lessons you now see. To narrate this figure, you wave a circular flourish with a mandritto, then throw the flag in the air, retrieving it with your other hand. This same play is continued, always keeping your arm in time with your foot, skilfully catching the wind. Other passes can be interposed, under the leg or other variations, serving to embellish the lessons and demonstrate the bravura of the practitioner. |

[18] A SCAGLIARE LʼINSEGNA. CAP. VII. IO so molto bene che le cose varie sempre dilettano, e per tale cagione mi sono ingegnato e di raccorre e di inventare le lezioni che si vedono. Per intendere la presente figura, si tira in giro di man dritto una velata, doppo si butta in aria la Bandiera, si ricoglie collʼaltra mano e si và facendo lʼistesso giuoco, accompagnando sempre col braccio il piede, e collʼartifizio il vento. Vi si possono ancora frapporre alcune passate di sotto gamba ed altre mutanze, che servono dʼornamento alle lezioni ad a mostrare lo spirito di chi le pratica. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How to perform a molinello Chapter VIII The molinello is delightful. To perform it comfortably, you should have the standard in your right hand. You complete a full turn above the head, then throw it up in the air, catching it around the middle of the standard as the figure shows. The molinello is then turned towards the rear foot. After several rotations, as your the hand becomes fatigued, you should grip the butt of the flag with your other hand and repeat the same lesson, again throwing it in the air as described above. |

[20] COME SI DEBBA FARE il Molinello. CAP. VIII. IL molinello è di molta vaghezza e per farlo con ogni facilità fà dì mestiere aver lʼInsegna nella man dritta; si compisce per sopra il capo unʼintera girata, ed allora si scaglia in aria, e si piglia intorno al mezo comʼinsegna la figura. Si volta il molinello verso il piede, che resta indietro, e fatte più ruote, divenuta la mano debole, si piglia collʼ altra il calcio della bandiera e si fà la medesima lezione, col buttarla parimenti in aria come sopra si è detto. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How to manage the standard behind your lower back Chapter IX This figure presents a wonderful innovation in this art. In order that everybody may understand it, I will briefly describe it. The flag should start in your right hand. Having performed a full flourish above your head, it is pulled backwards and with a reverse turn it is carried behind your back on the left side, where it can be fluttered several times, as desired, with your left hand. This can be performed while walking, or standing without walking. However it is always necessary to watch the length of your stride, and the wind, since it is dangerous to err while both hands are occupied, and you cannot view the motion of the flag, because in order to display your mastery we advise not to stare at it. Everyone can perform this same lesson with the left hand, loosening the arm and bringing it into presence, observing the order prescribed above. |

[22] COME SI MANEGGI LʼINSEGNA DIETRO LE RENI. CAP. IX. DImostra la presente figura una bellissima invenzione di questʼarte, e perché da ciascheduno possa essere intesa, brevemente la dichiararò. Deve ritrovarsi lʼinsegna nella man dritta, e fatta unʼintera sventolata sopra la testa, si rivolta di rivercio e con un giro si porta dietro le spalle nel lato manco, dove con lʼaiuto della man sinistra si formano vari ondeggiamenti a beneplacito, e questo si può far mettendosi in passeggio, o pure stando senza camminare; è però tanto più necessario lʼavere lʼocchio alla misura del passo, e del vento, quanto è più pericolo lʼerrore dove le mani sono ambe occupate, e non si può collʼocchio dar regola al moto della Bandiera, che per palesar la maestria ci proponiamo di non voler rimirare. Sarà libero a ciascheduno il poter fare con la sinistra la medisima lezione sciogliendo il braccio e portandolo en preferenza, con osservare lʼordine che di sopra è stato prescritto. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On waving the flag behind your back Chapter X In this figure the arm is kept extended, and very prominent, and after turning it behind your back, the standard is played from one side to the other, stepping proportionately so it does not get entangled. After a few waves you can repeat with your left hand, which I will omit to avoid being bothersome by lengthening my discourse. |

[24] DELLʼ ONDEGGIAR LA BANDIERA dietro le spalle. CAP. X. IN questa figura si tiene il braccio disteso, e molto eminente, e volgendolo doppo le reni, si fà giocare dallʼuno e lʼaltro lato lʼInsegna, muovendo il passo a proporzione perché non sʼavviluppi, ed il tutto doppo alcuni ondeggiamenti si può anco replicare con la sinistra, sopra la quale per non diventare molesti tralascierò dʼallongarmi nel discorso. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On how the standard is passed under the legs Chapter XI Having completed several steps, with both mandritti and riversi, you should raise the flag as required, adjusting for the ripples which form in various places, and finally bend your waist in the manner depicted. Having circled it above your head, you should lower your arm, passing the standard under your right leg, and by taking it with your left hand, the lesson you have followed has been performed. |

[26] DEL MODO CON CHE SI PASSA LʼInsegna sotto le Gambe. CAP. XI. DOppo dʼaver fatti più passaggi, e di man dritto e di rivercio, alzata secondoʻl bisogno la Bandiera, ed aggiustata allʼonde, che si formano in vari siti, finalmente si deve piegare la vita nella maniera che è stata figurata, ed avendo fatto un giro sopra la testa sʼabbassa il braccio, e si fà passar lʼInsegna sotto la gamba destra, e presala con la man sinistra si segue la lezione che è stata fatta. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On passing the standard around your neck Chapter XII I propose passing the flag around your neck. For this innovation your arm should tend to be high and extended. Having completed a few waves, you should judge the tempo so that the flag rests on your right shoulder. By pushing it, while catching a little wind from the left, you should let go of the shaft, turning your waist to retake the flag in the middle of the shaft, as the image indicates, entering into molinelli, and after the usual waves this lesson can be repeated with your left hand. |

[28] A FAR PASSARE LʼINSEGNA, intorno al Collo. CAP. XII. SI propone ai far passare intorno al collo la Bandiera. Questa invenzione ricerca il braccio al solito disteso, e alto, e date alcune velate si prende ʻl tempo acciò venga a posarsi nella spalla dritta, e spinta col darle un poco divento nella sinistra sʼabbandona lʼasta e volgendo la vita si ripiglia nel mezzo, come accenna il disegno, sʼentra ne molinelli, e doppo lʼusati ondeggiamenti si può replicare lʼistesso con la man manca. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

How to throw the standard while walking, changing hands Chapter XIII I hope to avoid being tedious by repeating the same things, or to become unclear by neglecting them. The standard is always in motion once the lessons begin, and the principal motions are the mandritti and riversi, which form the waves of the flag and are performed above your head. I am therefore forced to repeat this for the figure presented here, as we must connect them to what I wish to describe. Having circled with a riverso you should throw the flag high, and taking it with your left hand you should perform the same towards your right side. This can be repeated many times from one side to the other before beginning a new play, the entertainment and delight that lovers of this exercise feel deriving from its novelty. This assumes as always that the timing, step, and wind are duly observed, without which every effort loses merit and earns nothing but reproach. |

[30] COME SI DEBBA SCAGLIARE LʼINSEGNA Nel passeggio, e cangiar mano. CAP. XIII. IO temo di non esser tedioso nel replicar lʼistesse cose, e diventar oscuro nel tralasciarle. LʼInsegna è sempre in moto, quando si principian le lezioni, ed i moti principali sono i mandritti, e i riverci con i quali sopra la testa si formano e si compiscono le velate. Sono adunque forzato a ripeterli nella proposta figura, perché ad essi dobbiamo connettere quello che è lʼintento nostro di dichiarare. Fatto il giro di rivercio si buttarà in alto la Bandiera, e presa colla mano stanca si farà lʼistesso, e parimente si scagliarà dalla parte destra, il che e dallʼuna e dallʼaltra più volte replicato, si cominciarà nuovo giuoco, potendosi della novità pigliar quel trattenimento e quel diletto che sentono glʼamatori delle virtù, supponendo sempre che ʻl tempo, il passo, e ʻl vento habbino la dovuta proporzione, senza la quale perde ogni fadiga ʻl merito e non sʼacquista altro che biasimo. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On handling the standard under your legs Chapter XIV Having performed the rotations above, and with the standard in your left hand, it should be lowered, and by circling a mandritto it should be carried and helped along under your leg, forming waves as shown by the figure. Having retrieved it either on the side it was put in on, or from under your left leg, you should change hands, with equal mastery executing again what has been described. |

[32] DEL MANEGGIO DELLʼ INSEGNA sotto la Gamba. CAP. XIV. SI fanno le sopradette rotate ed avendo lʼinsegna nella man manca, sʼabbassa, e con un giro di man dritto si porta sotto la gamba ed aiutata come si vede nella figura si formano lʼonde, e doppo si cava per la via, che sʼè stata messa, o di sotto la gamba sinistra, si cangia mano, e con egual maestria si torna a porre in opera quanto abbiamo dichiarato. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On thrusts with the standard in the form of a cross Chapter XV The flag should be kept hoisted, and having circled a riverso in the usual way above your head, you should perform a thrust to your left side accompanied by your foot. Turning the flag towards your right side, you should then perform a thrust with the same mastery. The cross is completed by another two attacks. Your front foot should always be followed by your rear foot, and although everything is in itself quite straightforward, it is nonetheless difficult to put into practice without a maestro. |

[34] DELLE STOCCATE IN CROCE dellʼInsegna. CAP. XV. SI tiene la bandiera inarborata, e fatto un giro di rivercio al modo usato sopra la testa sʼaccompagnarà col piede una stoccata verso la parte manca, e volgendola verso la parte destra si tirarà la stoccata con la stessa maestria; si finisce la croce con altre due botte, il piè davanti deve sempre esser seguito da quel che è dietro, e benché il tutto sia di per se stesso assai chiaro, nulladimeno difficilmente si potrebbe mettere in pratica senza maestro. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On throwing the flag high behind your back Chapter XVI This lesson is difficult and requires the usual waves as a prelude. After these, it is performed with a riverso, passing the flag behind your back and raising it, although it rests on your lower back, throwing it high in the air with the force of your hand and in particular with your index finger. It is made to pass over your left shoulder, where it is grabbed by your left hand, before the play is repeated. Once completed the flag returns to your the right hand, although it is also possible to recover the pole without passing it from one hand into the other. |

[36] DEL GITTAR IN ALTO LA BANDIERA dietro le spalle. CAP. XVI. QUesta lezione è difficile e richiede anchʼessa le solite sventolate agguisa di preludi, si fa doppo con un rivercio passar dietro le spalle ed alzandola benché appoggiata alle reni si tira in alto con la forza della mano ed in particolare dellʼindice, e si fà passare sopra la spalla manca, qui si piglia con la mano sinistra e si rinnova il giuoco, il quale finito si torna alla man dritta potendosi ancora senza cambiar mano ricogliersi lʼasta. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

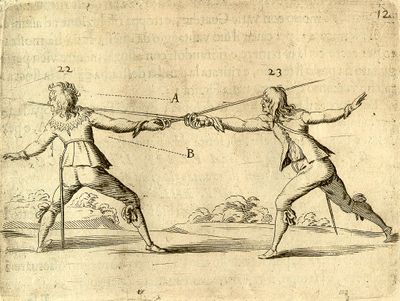

On passing the standard under the legs starting from the right Chapter XVII To perform the lesson shown here, having finished to circle a riverso, you should turn a mandritto while bending your body and lowering the standard, bringing it under both your legs starting from the right. All of this is performed in just one tempo, and what can be performed with one hand can always be performed with the other. |

[38] DEL PASSARE LʼINSEGNA sotto ambe le gambe cominciando dalla dritta. CAP. XVII. PEr far la lezione che si mostra, finito il giro di rivercio, si volta un mandritto con incurvare il corpo ed abbassare lʼinsegna, e si porta per di sotto ad ambe le gambe cominciando dalla dritta, si fà tutto in un tempo solo, e quello che si fà con una mano si può fare sempre con lʼaltra. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On montanti[6] with the right hand Chapter XVIII We have arrived at the manner of forming montanti. There is no guard or blow in fencing that cannot be adapted to the art of the flag. To perform what I wish to teach with this figure, the flag starts in your right hand, in motion above your head. Having finished to circle, the montanti begin first from your left side, and then from your right, redoubling them as you desire. You can also swap hands and repeat the same lesson, as we have described many many times in the other chapters. |

[40] DE MONTANTI DELLA Man Destra. CAP. XVIII. SIamo venuti al modo come formar si debbano i montanti. Non vʼè guardia né colpo da scherma che non venghi adattato allʼarte dellʼInsegna, e volendo far quello che è mio pensiero insegnare nella presente figura, si ritrovarà la Bandiera in passeggio di man dritta sopra la testa, e finita la giratta si cominciarà il montante prima dal sinistro, e poi dal destro lato, e raddoppiandoli a suo piacere, si può cangiar mano, e fai lʼistessa lezione, si come neglʼaltri capitoli abbiamo più e più volte dimostrato. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On throwing and recovering the standard with the same hand Chapter XIX In the handling of the flag it seems that dexterity and agility matter more than strength, but at times these attributes must be equal to one another and are of utmost importance. The truth of this is manifestly demonstrated by this figure. After several steps and flourishes of the flag you should firmly plant your feet, then turn a mandritto over your head and extend a half-thrust, launching the standard into the air with all the force of your lower back and your hand so that it rotates a turn and a half and drops as illustrated by the figure, retrieving it with the same hand. You then return to normal play, which is the usual prelude to a new lesson. |

[42] DEL BUTTARE, E RICCORE LʼINSEGNA con lʼistessa mano. CAP. XIX. NEl maneggio della bandiera par che la destrezza e lʼagilità preuguaglino la forza, ma alle volte deveno andar del pari ed essere in sommo grado, e che sia la verità manifestatamene si comprende nella nostra figura, perché doppo vari passaggi e velate della bandiera bisogna ben fermarsi ne piedi ed allora si deve di man dritta voltar una rotata sopra la testa e slogando una mezza stoccata, si tira con ogni forza e delle reni e della mano, lʼInsegna in aria si che giri, una volta e mezzo, e cada come è impresso nella figura, si prende con lʼistessa mano, e si ritorna al giuoco ordenario, che suole sempre essereʼl principio dʼuna nuova azione. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On the standard with the hand reversed Chapter XX Having performed the last flourish to enter into this lesson, the standard is thrown into the air and gathered with the hand reversed. Your arm should be extended, and the tip of the staff must be pointed towards the ground. With judicious use of timing, and the wind, you will be able to perform waves, flourishes, passes under the leg, turns of the flag behind your lower back, and all that you have been able to learn from the faithfulness and merit of your maestro. |

[44] DELLʼ INSEGNA sotto mano. CAP. XX. FAtta lʼultima velata per entrare nella nostra lezione, si gitta lʼinsegna in aria e si ricoglie con la mano rivercia, il braccio sarà disteso, e la punta dellʼasta deve essere volta verso terra, e valendosi aggiustatamene del tempo, e del vento potrà fare ondeggiamenti, velate, sottogambe, girate di bandiera dietro le reni, e tutto quello che avrà potuto imparare dalla fedeltà, e valore del suo maestro. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On gathering the standard Chapter XXI All the things that bring us delight, if they pass beyond a certain point, become bothersome. The end is the completion of the work undertaken. Having therefore to gather the standard, you should hold it with your right hand over your shoulder, and catching a bit of wind, the edge should be grasped with your left hand. Thereby holding it in the posture shown you may end your labours with high praise. |

[46] DEL RACCOGLIERE LʼINSEGNA. CAP. XXI. TUtte le cose che ci arrecano diletto, se passano il segno diventano moleste, il fine e la perfezione di ciò che cominciamo ad operare, però dovendo dunque raccorre lʼinsegna si terrà con la man dritta nella spalla e dandogli un poco di vento si piglierà per filo vicino al lembo con la mano stanca, e così tenendola nella postura del legno si potrà con lode terminare le sue fatighe. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On putting your hand to the sword Chapter XXII The sword is a weapon that is used in various ways, the effeminate use it to ornament their perfumed finery, and to strong men it is minister of wrath, in defence of duty. But refraining from speaking too long on the subject, I will continue with as much as I propose to say on this topic for now. Wishing therefore to unsheath your sword, if the flag is in your right hand, you can throw it in the air and catch it with your left, or without this action you can pass it naturally into the other hand. Raising the flag so that you have more room at your flank, the sword can be drawn as clearly demonstrated by the figure. Putting yourself in a firm stance, all that remains is to show yourself as experienced in this noble practice. If you wish to change hands, the sword should be placed under your arm, and having grasped the standard, your left will be armed, and you can perform whichever passages or lessons of the art you have learned. |

[48] DEL METTER MANO ALLA SPADA CAP. XXII. LA spada è unʼarma che diversamente sʼimpiega; glʼeffemminati se ne vagliono per ornamento della loro profumata attillatura, e agli uomini forti è ministra dʼira, che defende il dovere; ma riservandomi di parlar più longamente in breve sopra questo soggetto, seguitarò per ora quel tanto che mi sono proposto. Volendosi dunque venire a sfodrare la spada, se la bandiera sarà nella man dritta, si può scagliare in aria e prenderla con la sinistra, o senza questʼatto la possiamo portare naturalmente nellʼaltra mano, ed alzandola per avere il fianco più libero si trarrà fuor la spada come si vede chiaramente nella figura, e mettendosi ad un passo ben regolato non restarà di farsi conoscere sperimentato in questo nobile esercizio, e volendo cambiar mano, si metterà la spada sotto il braccio, e presa lʼInsegna, resterà armata la sinistra, e si potranno fare quei passaggi e quelle lezioni che si sono apprese nellʼarte. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On walking with sword and flag Chapter XXIII The first admonishment we must give to explain this figure, is that the sword and the flag must be held firmly and solidly. You are free to play according to your inclination, and the hand can be changed in one tempo by throwing the standard forwards into the air, grabbing the sword as it falls. This can be performed several times, because it is a beautiful lesson, and truly worthy of being observed. |

[50] DEL CAMINAR COLLA SPADA, e Bandiera. CAP. XXIII. IL primo auvertimento, che dobbiamo havere per dichiarazione della figura, si è, che la spada, e la bandiera, deveno essere, impugnate sodamente, e con fermezza, é libero il giocare secondo il genio, e si potrà cambiare la mano ad un tempo istesso buttando in aria lʼInsegna ed avanti, che cada pigliando la spada, e ciò si potrá far più volte, perche è una bellissima lezione, e veramente degna dʼesser osservata. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On managing the standard with your right, while your left is armed Chapter XXIV It is a fixed rule that the standard should never be idle. While your left hand holds the sword your right nevertheless remains free, but when it is somehow hindered, as I have said elsewhere, it is all the more praiseworthy. Performing this lesson with your hand behind your back, your left hand should be raised as per the figure, and with the usual waves of the flag, you can loosen your arm and enter into another lesson, changing hands, catching the wind and taking the tempo as required. |

[52] DEL MANEGGIAR LʼINSEGNA con la dritta essendo armata la man sinistra. CAP. XXIV. QUesta è fermissima regola, che lʼInsegna non deve mai essere oziosa, e però se bene la man sinistra regge la spada, rimane tuttavia libera la destra, e quando sia in qualche modo impedita come ho detto altre volte, tantʼè più lode, e facendo la lezione di rivescio il braccio sinistro si terrà alzato siccome è nel disegno, e formando i soliti seni collʼondeggiar della bandiera, sciorrà doppo il braccio, sʼentrerà nellʼaltra lezione, si mutarà mano, pigliando il vento; e ʻl tempo che vi bisogna. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On sheathing your sword Chapter XXV The present figure speaks for itself. To return your sword you should gather up the standard, holding it very firmly with your left so it does not touch the ground. This is performed after the lesson we proposed above. You can also raise the flag with the same hand while leaving it unfurled. |

[54] DEL PORRE NEL FODERO la Spada. CAP. XXV. LA presente figura è per se stessa manifesta; per rimettere la spada bisogna raccorre accanto lʼInsegna, e sostenendola ben forte con la sinistra perché non tocchi terra, si fà doppo la lezione che ci siamo proposta, ed intanto si potrà alzare la Bandiera con lasciarla spiegata nella medesima mano. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On unsheathing the sword for defence Chapter XXVI Dangers arise when you least expect them, bravery allows us to fight, but victory depends on skill, to defend yourself in incidents both in war and peace. First your should quickly gather the standard, drawing your sword over your left arm, and turning the shaft towards your enemy, you should set yourself into a strong guard to resist against any offensive. |

[56] DEL CACCIAR MANO per diffesa. CAP. XXVI. NAscano i pericoli quando meno si credono, lʼardimento ci fà combattere, ma la vittoria è propria della virtù per difendersi daglʼaccidenti tanto in guerra che in pace, si raccorrà primieramente lʼInsegna, e sopra il braccio manco si daverà la spada, e volgendo lʼasta verso il nemico si disporrà in buona guardia per resistere ad ogni offesa. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On the guard of sword and flag Chapter XXVII Defending yourself is so natural that the law still allows it against those who attack us in vendetta. If the ensign or other person is placed in this situation he should quickly gather and set the standard so that it does not block his view, but rather protects with its sheer volume.

The arm should be somewhat bent, with the hand held in terza, keeping his body in profile so it is better covered and presents a smaller target. The body should be balanced over his left leg, the nearby right foot remaining free and unencumbered, thereby able to press his enemy. He should set his stride, not too forced, and move to gain ground, the sword denying tempo and measure by anticipating his enemy's actions. The response should be faster than the call. Cuts should be parried from tutta coperta[7] or defended with voids of the body, while wounding with the point. If the enemy waits then he should be pressured, put into obedience and deceived; teaching the enemy, the threatener of life, that he is not worthy of the pleasure of living. |

[58] DELLA GUARDIA COLLA SPADA, e la Bandiera. CAP. XXVII. E Tanto naturale il difendersi che ce lo permettono le leggi, ancora contro quelli che per vendetta ci offendono. Venendo posto lʼAlfiere od altra persona in questa necessità, deve raccorre ed accomodare lʼInsegna di tale sorte che non impedisce la vista e che più tosto li serva di riparo, che di gravezza. Il braccio sarà alquanto incurvato eʻl sito della mano in terza, terrà il corpo in profilo per essere più coperto, e far minore il bersaglio, il corpo si posarà nella gamba stanca ed essendo il piè destro accanto libero, e leggiere potrà stringere il nemico; deve formare il passo che non sia molto sforzato, ed andare al guadagno del terreno, e della spada togliendoli il tempo e la misura col prevenirlo, la risposta sarà più veloce della chiamata, i tagli si pararanno di tutta coperta, o con iscanzi di vita ferendo di punta, e se ʻl nemico aspettasse, allora bisogna stringerlo metterlo in obbedienza ed ingannarlo, insegnandoli che non è degno di godere la vita chi è nemico insidiatore della vita. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On gathering the flag Chapter XXVIII Having finished the lessons the flag is gathered and carried in your left hand, keeping the edges wrapped over, with your arm supporting the shaft. These plates, made by a good engraver, if they are followed by whomever delights in such exercises, will credit my work, and have often relieved me of toil.[8] |

[60] DEL RACCORE LA BANDIERA. CAP. XXVIII. FInita la lezione si raccoglie la Bandiera portandola nella mano stanca, con tenere i lembi avviluppati e col braccio sostenendo lʼasta. Il disegno fatto da buono intagliatore se fusse accompagnato da chiunque si diletta di tali esercizi, le mie opere avrebbero più credito, ed io farei bene spesso con manco briga. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Conclusion I have arrived at the end of what I proposed. I confess my shortcomings, but nonetheless I will serve as a stimulus to others who understand more, to discover what I have not known, and demonstrate it in a style beyond the capacity of my intellect. In this apathetic century it is difficult to please. Those who look at my soul will see what it yearns for. Meanwhile I console myself that a wise man is always understated.[9] |

[62] CONCLUSIONE. SOno arrivato al fine che non sono disposto, confesso la mia debolezza, servirò nulladimeno di studio ad altro più intendente di ritrovare quello chʼio non ho saputo, e come parlo con quello stile di cui non è capace lʼingegno, è difficil cosa ʼl piacere in questo secolo svogliato, chi riguarderà il mio animo trovarà ciò che brama, ed io intanto mi consolo, che lʼuomo saggio è sempre discreto. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For Printing in Padua. Brother Antonius Lendenaria, Inquisitor General of Padua, seen and approved. On the 6th September 1638. On the 21st day of October 1638. { Battisti Nani, Magistrate. Alvise Querini Secretary. |

[63] PRO IMPRESIONE PADUAE. Fr. Antonius á Lendenaria Inquis. Generalis Paduae vidit, & approb. Die 6. Settembris 1638. Adi 21. Ottobre 1638. { Battista Nani Reff. Aluise Querini Secret. |

Illustrations |

Transcription (1641) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

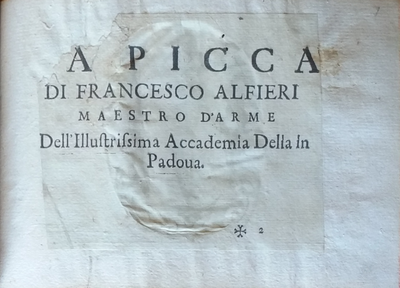

The Pike by Francesco Alfieri Master of Arms of the most illustrious Accademia Delia in Padua. |

[i] LA PICCA DI FRANCESCO ALFIERI MAESTRO D'ARME Dell'Illustrissima Accademia Delia in Padoua. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Most Illustrious Sir and Honourable Patron The acquisition by your most illustrious house of the domain of Ortenburg, a most noble county in the Empire in Carinthia, was to me - as your most devoted servant, so joyful that I could not comprehend it in my heart. I was obliged to communicate it to the world with this present book, which as a living testimony of my infinite obligations I dedicate to the immortality of your most illustrious name. The gift is small, and greatly disproportionate compared to the greatness of your merits, while in comparison my talents are also meagre. However, they are not without esteem, when they have the fortune to be accompanied by your favour. I dedicated my treatise on the flag to Your Most Illustrious Excellency, which you were pleased to enjoy. Although all that can be acknowledged as singular in it is my veneration, my spirit - ever in a tone of respect, gives me hope that you will equally enjoy this brief treatise on the pike. The laudable labours of intellect should by every right be offered to Your Most Illustrious Excellency, who for the splendour of the sublime virtues all around you, will at all times be beyond all compare. In which gentlemanly art shall you not prevail? Which science, that in arms or civilian life can render one respected, in you does not merit to be admired? I think not to speak at length of your qualities, which is not a weight for my shoulders, I speak with the tongue of all, which is moved only by the truth. May Your Most Illustrious Excellency enjoy, with every peace, the possession of many goods, and be it my glory to be named among those who in perpetuity depend upon your gestures. To Your Most Illustrious Excellency I bow. From Padua the 28th March 1641. To Your Most Illustrious Excellency Your most humble servant Francesco Alfieri. |

[iii] ILLUSTRISSIMO SIGNOR Sig. e Padron Colendiss. L’ Acquisto fatto dall’ Illustrissima sua Casa del Dominio d’ Ortemburgh nobilissima Contea dell’ Imperio nella Carintia, è stato à me come devotissimo suo servo di tanta allegrezza, che non porendo capire nel mio petto sono stato costretto à, comunicarla al mondo col presente Libro, che per vivo testimonio delle mie infinite obbligazioni consacro all’immortalità dell' Illustrissimo suo nome, Piccolo è il dono, e di gran lunga sproporzionato colla grandezza de’ fuoi meriti, ma deboli all’ incontro sono ancora i miei talenti; i quali pero non sa- [iv] ranno mai senza stima quando habbiano tanta fortuna, che l’autorità del suo favore l’accompagni: Dedicai à V.S. Illustrissima il mio trattato della, Bandiera si compiacque di gradirlo, leu che non vi potesse ricognosscere di singolare altro che la mia venerazione, l’animo che nell’ossequio è sempre d’un tenore m’ha posto in speranza, che le sia parimente per esser à grado questo breue trattato della Picca, Le fadighe dell’ingegno lo devoli deuono per ogni dritto esser offerte à V.S. Illustriss. che per le virtù subblimi delle quali risplende tutto adorno verrà in ogni tempo ad esser maggiore d’ogni esempio, Qual è quell’esercizio Cavalleresco in cui essa non prevaglia? qual è quella scienza che possa, e nell’armi, e nella, vita civile rendere altrui riguardevole, che in lei non meriti d’esser ammirata? non è mio pensiero dilungarmi nelle sue prerogative, che non è peso dalle mie spalle, parlo con la lingua di tutti, che solo è mossa dalla verità; Goda V.S. Illustriss. con ogni pace il possesso di tanti beni, sia mia gloria l’esser annoverato frà quelli che in perpetuo dependeranno da suoi cenni; E à V.S. Illustriss. riverente m’inchino. Di Padova li 28. Marzo 1641. Di V.S. Illustrissima Umillissimo Servitore Francesco Alfieri. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TO THE READER. It was not long ago that you saw my La Scherma come off the presses. The first essay of my labours was La Bandiera. Now I add La Picca. The book is not long, but it is complete. These days brevity is prized, especially if not due to omission of elements necessary, for the work not to be deficient. I have condensed all of the art into a few figures, or at least the true foundations of the art. Subtle and practised intellects may find various innovations which are not here within, but one who has well grasped what I demonstrate will know that they are superfluous, or without difficulty. It has always been my aim to guide students to perfection through clear streets, approved by the good, and not confuse them with contrivances and fantasies, which only serve to waste time. I wish to satisfy the desires of all, and if the style or the material is not valid for this aim, I should be pitied all the more, because the intention I had to please the public made me wish for more than I could have. |

[03] AL LETTORE. NOn è molto che hauete veduto uscir dalle stampe, la mia Scherma, fù il primo saggio la delle mie fadighe la Bandiera, di presente v’aggiungo la Picca; Il libro non è grande è però intero, piace oggidì la breuità, ed in particolare se non è tale per la mancanza delle parti, che son necessarie perche l’opera nõ sia difettosa, Ho ristretra in poche Figure tutta l’arte, ò almeno i veri fondamenti dell’arte, possano l’ingegni sottilied esercitati ritrouar diverse inuenzioni, che quì non vi sono, ma chi ben possiede quanto da me vien dimostrato conoscerà che sono superflue, ò senza difficultà. E slato sempre il mio fine condurre lo Scolare alla perfezione per vie libere, e che sono approvate da buoni, e non confonderli con capricci, e fantasie, che solo seruono à mal trattare ’l tempo: Vorrei sodisfare al desiderio di tutti, e se lo stile, ò la materia non son valevoli à farlo, tanto più devo esser compatito perche l’intenzione, che hò havuto di giovare al publico mi hà fatto volere più, che non posso. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE OF CHAPTERS: On the pike Chapter I One the use of the pike Chapter II On the difference between the pike in play and in war Chapter III On picking up the pike Chapter IV On grasping the pike Chapter V On marching with the pike at your shoulder Chapter VI On arming the pike Chapter VII On the raised pike Chapter VIII How the captain bears the pike in formation Chapter IX On the pike in places where in cannot be raised Chapter X On carrying the pike when retreating, etc. Chapter XI On sliding the pike, and on the sword Chapter XII On the pike and sword in battle Chapter XIII On raising the pike to your shoulder while holding your sword in hand Chapter XIV On putting the sword in its sheath Chapter XV Conclusion of the work Chapter XVI |

[04] TAVOLA DE CAPITOLI:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On the Pike by Francesco Ferdinando Alfieri Chapter I Man is by nature difficult to content. To take away the opportunity for conflict, the lands were divided, and domains introduced. Each began by recognising their own, and almost all at once, either to protect theirs or to occupy that of their neighbour, they came to war. For war they discovered weapons, and among the first was the pike. All things, at the beginning are rough, and bit by bit are improved. In this manner the pike was initially used without the refinement to which it has been distilled. Before iron was discovered, the shaft was armed with sharp stones, bones, and similar materials apt to harm, and in this way they fought. Having discovered iron, it was placed at one and by many peoples at both extremities, in the form that was believed most piercing, and strongest in attack. Its length and width varied depending on how more or less robust were the nations who used it. The Assyrians were the first, who in the opinion of many serious authors carried them in war, this province having had the first kingdoms and lordships. The Jews, whose armies blossomed because the great prophet Moses had learned from God, ordered their units armed with the pike, as clearly seen several times in the Bible. The battles they fought in Palestine, against those condemned by divine justice to be defeated by the chosen people, were conducted by armies who fought with polearms. The Persians also used it, and honed their skill in wielding it, as the great commander Cyrus, alongside military discipline, introduced the art of training. After the Persians, the glory of arms flourished in Greece. They too held it in esteem, as you see from the lives of Palamedes, Philopomenes, Miltiades, Themistocles, and other warriors of great renown: Athenians, Lacedaemonians, and Thebans. Philip of Macedon, who learned expertise at arms from Lysis, [10] formed his phalanx armed with polearms, with which his son Alexander the Great subjugated little less than the world. The Republic of Rome, in all of its virtues superior, including in the power it held on earth, had its "hastati", and with this weapon the name of its legions inspired terror. But to approach our times, omitting to recall Uguccione dalla Faggiola, and in particular the famous Castruccio Castracani, who propelled the military disciplines forward having been long neglected, the Swiss will always be immortal for their pikes, with their skill in using them, having been the arbiters of victory in Italy. Everyone knows the level they rose to, when the wars became more merciless for the state of Milan; which was stripped from Ludovico il Moro, his son Maximillian, Luis XII the King of France, and Francis I. Because the Emperor took every effort to return the Sforzas to the duchy, there followed the celebrated feats of arms at Novara, Bicocca and elsewhere, which will stand as eternal testimony to the valour of that free nation of thirteen cantons. Therefore, none can doubt the antiquity, nobility, and marvellous effect of the pike; and it is very certain that as such should be considered this art, and that worthy always of praise shall be those, who wishing to follow the fortunes of war, undertake with every care to learn it. |

[05] DELLA PICCA DI FRANCESCO FERº ALFIERI. CAP. I. L'Huomo è di si fatta natura, che difficilmente si contenta, Per tor via l'occasioni delle contese, furono divise le terre, e s'introdussero i dominij; principiò ciascheduno à riconoscere 'l suo, e quasi ad un tempo, ò per conservarlo, ò per occupar quel del vicino si venne alle guerre, e per le guerre si ritrovarono l'armi, frà le quali una delle prima fù la Picca, Tutte le cose, ne principij son roze ed à poco à poco si perfezionano, così la Picca su [06] da principio usata senza quella politezza alla quale è stata ridotta, Avanti che fusse ritrovato 'l ferro armavano l'aste con pietre taglienti, ossi, e simili materie atte à ferire, ed in questo modo combattevano, ma ritrovato il ferro fù posto in una e da molti popoli in ambe due l'estremità con quella forma, che veniva creduta più pungente, e più forte ad offendere, la sua longhezza, e grossezza fù varia secondo che più, ò meno robuste erano le nazioni, che se ne servivano. I Siri furono i primi, che al parer di molti gravi Autori le portarono in guerra havendo in questa provincia havuto principio i Regni, e le signorie: Gl'Ebrei ne quali fiorì la milizia per haverla il Gran Profeta Moisè imparata da Dio, ordinavano le loro squadre armate di Picca come in diversi luoghi della Scrittura chiaramente si vede, e le battaglie che fecero nella Palestina con le genti condennate dalla Divina giustizia ad esser disfatte dal popolo eletto, furno fatte d'eserciti che guerreggiavano coll'aste; i Persi ancora l'usarono, e s'avvezzavano à saperla ben maneggiare, poi che Ciro grandissimo Capitano introdusse con la disciplina militare, l'arte d'esercitarsi; Doppo i Persi e che la gloria dell'armi fiorì nella [07] Grecia ancor essi l'hebbero in pregio come si vede nelle Vite di Palamede, Filopomene, Milziade, Temistocle, e altri guerrieri di gran nome Ateniesi Lacedemoni, e Tebani: e Filippo Macedone che imparò da Liside la perizia dell'armi formò armata d'aste la sua Falange, con la quale Alessandro Magno suo figlio si sottomise poco meno ch'el Mondo; la Repubblica di Roma, che in tutte le virtù fù maggiore come anco nella potenza di quante ne hebbe la terra haveva i suoi astati, e con quest'armi divenne terribile il nome delle loro legioni. E per avvicinarmi à nostri tempi tralassando di rammemorare Uguccione dalla Faggiola, e particolarmente il famoso Castruccio Castracani, che rimise in essere la disciplina militare avanti per più tempo trasandata, li Svizzeri saranno sempre per le lor picche immortali essendo stati per la loro bravura in maneggiarle l'arbitri delle vittorie dell'Italia, ed ogn'un fa in che grado salirono quando incrudelivano le guerre per lo stato di Milano, del quale, Lodovico il Moro da Lodovico XII. Re di Francia, e Massimiliano suo Figlio, da Francesco Primo ne furono spogliati, perchè facendo l'Imperatore ogn'opera per rimettere li sforzes- [08] chi nel ducato seguirono i celebri fatti d'arme à Novara alla Bicocca, ed in altri luoghi, che saranno sempre eterni testimoni del valore di quella libera Nazione de' Tredici cantoni, onde non essendo da dubbitare dell'antichità, nobiltà, e meravigliosi effetti della Picca. E' certificammo ancor, che tale per ogni ragione deve esser giudicata quest'arte, e che degni sempre di lode saranno quelli, che volendo seguire la fortuna della guerra procuraranno con ogni studio d'impararla. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

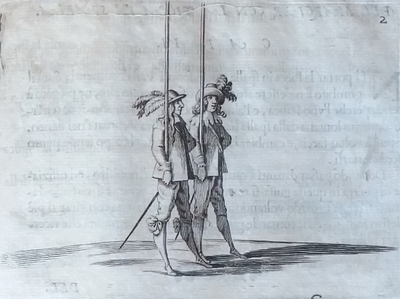

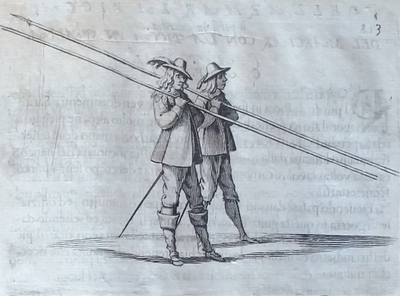

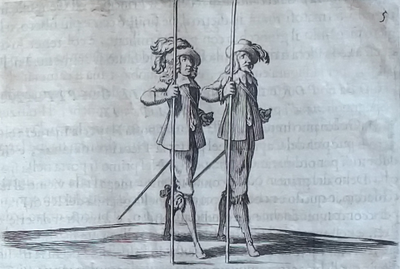

On the use of the pike Chapter II To make good use of the pike it is necessary to know its length and nature. Regarding its length, ordinarily it is nine braccia,[11] as to its nature it should be made of smooth ash, the wood well-seasoned. In earlier times it was carried without defensive arms, to be wielded with more agility, and because people had not become so ingenious in attack. However, since in this manner it wounded only at a distance, and if the enemy closed it was not possible to resist his impetus, every hope having been placed in the polearm, through experience it became clear that used in this way it was of little consequence. For this reason, soldiers were further equipped with a rather short and broad sword, to be quick and apt for cutting, and also a dagger, a much-esteemed weapon at close quarters. Also, since pikemen serve to form the body of the troops, and to absorb the clash and impetus of horses, in order not to be scattered they nowadays cover themselves with their tassets, [12] bracers, gauntlets, gorgets, and morions, [13] such that half of their body is well-armoured. Because of this they can easily thwart attempts and efforts of the enemy, all the more so if the garrison stretches out on the sides of the battlefield, being lines of as many musketeers as the pikes can cover. The pike should therefore be of a determined size, in proportion to the stature and strength of the men, bearing their defensive arms, which without impeding the soldiers increases their confidence and disposes them to fortitude. |

[09] DELL'USO DELLA PICCA. CAP. II. PEr ben servirvi della Picca fà di mestiere saper la sua longhezza e qualità, quanto alla longhezza l'ordenaria è nove braccia, quanto alla qualità deve esser di Frassino liscia, e che sia il legno bene stagionato; Anticamentè veniva portata senz'armi difensive per essere più agile à maneggiarla, e perche non era l'huomo diventato tanto ingegnoso nell'offendere, ma perche in tal modo solo feriva da lontano ed il nemico avvicinandosi non si poteva più far resistenza contro'l suo impeto per esser posto ogni speranza nella sola asta, s'è venuto in cognizione per esperienza, che usata in tal modo non era di molta conseguenza, per il che gl'è stata accresciuta al soldato la spada alquanto corta, e larga per haverla più spedita, e facila à tagli, ed insieme il pugnale arme di grande stima alle strette: E perche i picchieri serveno per formare'l corpo della battaglia, e ritenere l'urto, e l'impeto de Cavalli per- [10] che da questi non vengano sbaragliati vesteno di presente il petto con i suoi scarselloni, bracciali, manopole, goletta, e morrione; talche essendo ben armata la metà della vita possono in questo modo render vani agevolmente i tentativi, e li sforzi dell'inimico tanto più, che si distende da lati della battaglia la guarnizione, che sono file di tanti moschettieri quanto possono esser coperti dalle Picche, S'adopra dunque con una determinata grandezza proporzionata alla statura, e forza di tutti gl'huomini accompagnata con le sue armi difensive, che senza impedire soldato gl'accrescano confidenza, e lo dispongano alla fortezza. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On the difference between the pike in play and in war Chapter III Since many only enjoy criticising, some will say right at the beginning that there is pike for combat, and pike for play. I know very well that in the field, in front of the enemy you do not think of pomp, or to show your dexterity, nor your grace, nor do you arrive at certain actions that serve to delight more than to wound. But we are permitted to ask these people whether such knowledge of handling the pike is advantageous; whether the art of thrusting without entangling and confusing yourself facilitates superiority. Knowing the tempo and when to exploit it, being ready to use the haft in different ways, and putting your hand to the sword are essential elements in war, and these are learned primarily in the academies, where they demonstrate the methods that you practise in play. It is impossible to know how important and useful it is to a soldier, to grasp all that can be done with the weapon, that by its election must be the instrument of his honour, and of his fortunes. If someone completely new is deployed, and it is necessary to fight somewhere narrow, you cannot see anything more ridiculous and useless; if he wishes to put his hand to his sword and his pike falls, or if he must change face he will crash into and harm either his line or those close by. In the end it will not be good either for him or his captain. This does not happen to one who is practised in the art, because one who possesses what is most difficult also possesses what is most straightforward in the same art. However, one who knows who to make the pike fly, how to make it slide and run in every direction will not tangle himself up, nor give occasion through his harm to be mocked. They are therefore different, but in play you encompass everything that is necessary in war, where only those who know make progress. Because as the saying goes, nobody has doubts in something they know to have learned well. To attain this knowledge, you must practise, and you must commend that which makes you familiar with those precepts that conduct you to your aims. Sweat in the more difficult things, to delight in them, so they turn out more to your liking, malleable to your thoughts. |

[11] DELLA DIFFERENZA DELLA PICCA. nel giuoco, e nella guerra. CAP. III. PErche il gusto di molti è solo di contradire, però mi diranno alcuni al bel principio, che altro è la Picca con la quale si combatte, altro è la Picca con la quale si giuoca, Io ben sò che nel campo, e davanti all'inimico non si pensa à far pompa, ne della destrezza, ne della leggiadria, ne si viene ad altri movimenti, che serveno più tosto à dilettare, che à ferire, ma siami lecito il domandare à questi se il saper maneggiare l'asta sia vantaggio; se l'haver per arte lo stoccheggiar con giudizio senza invilupparli, e confonderli faciliti l'essere superiore, il conoscere'l tempo, il saperne servire, e l'esser pronto à valersi diversamente dell'asta, e cacciar mano alla spada sono parti necessarie nella guerra, e queste s'apprendono primieramente nell'Accademie dove si mostran le maniere, ch'esercitan per giuoco, non è possibile à [12] credere di quant'ornamento sia, e di utilità ad un soldato il posseder tutto quello, che si può fare con quell'arme, che deve essere per sua elezione l'istrumento dei suoi onori, e delle sue fortune, si metta in ordinanza uno in tutto nuovo, e che li sia necessità in luogo stretto combattere, non si potrà vedere cosa più ridicola, ne più inutile, se vuol mettere mano alla spada li cascarà la Picca, se dovra voltar faccia urtarà offenderà, ò la sua fila, ò le vicine; e finalmente non sarà buono, ne per se, ne per il suo Capitano, cosa che non avviene à chi è nell'arte esercitato, perche chi possiede ciò che è più difficile possiede nell'istesso mestiere quello che è più agevole, e però chi sa far volare la Picca, e senza perderla, farla strisciare, e scorrere per ogni parte non s'imbrogliarà, ne darà occasione con suo danno d'esser burlato, son dunque differenti, ma nel giuoco vi si comprende tutto quello, che è necessario nella guerra, dove non fanno progresso se non quelli che sanno, perchè è sentenza, Che nessuno dubbita di fare quello, che si ha fidanza d'haver bene imparato, e per acquistar questo concetto fa di mestiere l'esercitarsi e [13] si deve commendare quello, che per farsi familiari quei precetti, che l'hanno à condurre à suoi fini suda nelle cose più difficili per ritrovar diletto in quelle, che le riescano più della sua credenza pieghevoli à suoi pensieri. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

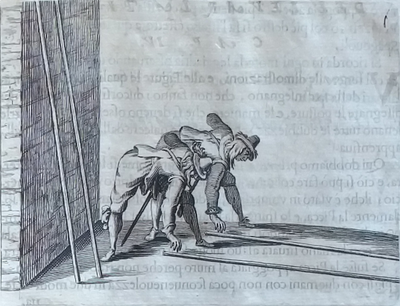

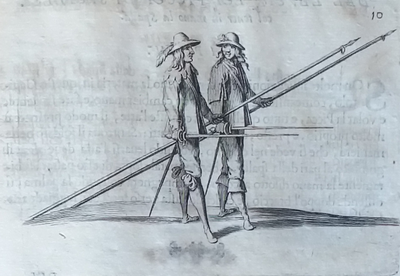

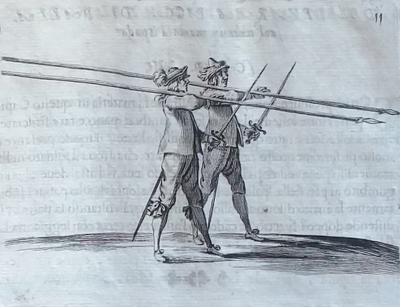

On picking up the pike Chapter IV I arrive at the demonstrations, and at the figures, which teach much more effectively than discourses, because seeing the designs of the postures, and the methods that you must observe to imitate them, lifts all doubts that could emerge from weakness in learning. Here, we must firstly learn how to lift the pike from the ground. This can be achieved equally with the forehand as with the backhand, as is universally observed. However, you must ensure to grasp the pike firmly, and raising it in the air should be accomplished in a single indivisible tempo, holding your body straight, without twists, and having lifted it, with your hand in place, it should slide close to your right thigh. If the pike is resting against a wall, in order for it not to tumble, or to avoid grasping it with two hands with no little inconvenience, it can be picked up in two ways. Either you place your left foot at the base so that it stays still, as the French do, or with your right foot to the same effect, as is customary for the Spanish. Remember to be graceful with every motion, ensuring to grasp the pike by keeping your thumb extended under the haft, with your right hand situated level with your sword. |

[14] DEL LEVAR LA PICCA. CAP. IV. VEngo alle demostrazioni, e alle Figure le quali molto più efficacemente insegnano, che non fanno i discorsi, perche il veder disegnare le posture, e le maniere, che si deveno osservare per imitarle levano tutte le dubbiezze, che potessero nascere dalla debolezza dell'apprensiva. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Qui dobbiamo primieramente imparare come si levi la Picca di terra, e ciò si può fare col tener la mano tanto per dritto quanto per rivercio, ilche è usato in universale, si deve però osservare ch'el pigliar sodamente la Picca, e lo spingerla in aria vuol esser fatto come in un tempo indivisibile fermandosi nella vita dritto, e senza sconci, e sollevatala deve con la mano situata al suo luogo scorrere appresso la coscia destra. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|