|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Fiore de'i Liberi"

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

| below = [[File:Concordance.jpg|link=http://freifechter.com/article7.cfm]] | | below = [[File:Concordance.jpg|link=http://freifechter.com/article7.cfm]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi de Cividale d’Austria''' (Fiore delli Liberi, Fiore Furlano, Fiore de Cividale d’Austria; ca. 1340s - 1420s<ref>This estimated birth date is derived from Fiore's statement that in 1409 he had been studying the art of arms for 50 years, based on the fact that nobility generally began instruction in the martial arts around the age of ten. See [[Ken Mondschein|Mondschein]], p 11. The death date listed assumes that the story about his activities in Paris is correct; see note 27, below.</ref>) was a late [[century::14th century]] knight, diplomat, and itinerant [[fencing master]]. He was born in Cividale del Friuli, a town in the Patriarchal State of Aquileia (in the Friuli region of modern-day Italy), the son of Benedetto and scion of a Liberi house of Premariacco.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan">[[Fiore de'i Liberi]]. ''Fior di Battaglia'' [manuscript]. [[Fior di Battaglia (MS M.383)|MS M.383]]. New York City: [[Morgan Library & Museum]], ca. 1400. ff 1r-2r.</ref><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty">[[Fiore de'i Liberi]]. ''Fior di Battaglia'' [manuscript]. [[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|MS Ludwig XV 13]] (ACNO 83.MR.183). | + | '''Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi de Cividale d’Austria''' (Fiore delli Liberi, Fiore Furlano, Fiore de Cividale d’Austria; ca. 1340s - 1420s<ref>This estimated birth date is derived from Fiore's statement that in 1409 he had been studying the art of arms for 50 years, based on the fact that nobility generally began instruction in the martial arts around the age of ten. See [[Ken Mondschein|Mondschein]], p 11. The death date listed assumes that the story about his activities in Paris is correct; see note 27, below.</ref>) was a late [[century::14th century]] knight, diplomat, and itinerant [[fencing master]]. He was born in Cividale del Friuli, a town in the Patriarchal State of Aquileia (in the Friuli region of modern-day Italy), the son of Benedetto and scion of a Liberi house of Premariacco.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan">[[Fiore de'i Liberi]]. ''Fior di Battaglia'' [manuscript]. [[Fior di Battaglia (MS M.383)|MS M.383]]. New York City: [[Morgan Library & Museum]], ca. 1400. ff 1r-2r.</ref><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty">[[Fiore de'i Liberi]]. ''Fior di Battaglia'' [manuscript]. [[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|MS Ludwig XV 13]] (ACNO 83.MR.183). Los Angeles: [[J. Paul Getty Museum]], ca. 1400. ff 1r-2r.</ref><ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi">[[Fiore de'i Liberi]]. ''Flos Duellatorum'' [manuscript]. [[Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)|Pisani Dossi MS]]. Italy: Private Collection, 1409. f 1rv.</ref> The term ''Liberi'', while potentially merely a surname, more probably indicates that his family had Imperial immediacy (''Reichsfreiheit''), either as part of the ''nobili liberi'' (''Edelfrei'', "free nobles"), the Germanic unindentured knightly class which formed the lower tier of nobility in the Middle Ages, or possibly of the rising class of Imperial Free Knights.<ref>He is never given such a surname in any contemporary records of his life, and the term only appears when introducing his family in his own treatises.</ref><ref name="Mondschein 11">Mondschein, p 11.</ref><ref>Howe, Russ. “[http://ejmas.com/jwma/articles/2008/jwmaart_howe_0808.htm Fiore dei Liberi: Origins and Motivations]”. [[Journal of Western Martial Art]]. Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences, 2008. Retrieved 2012-02-08.</ref> It has been suggested by various historians that Fiore and Benedetto were descended from Cristallo dei Liberi of Premariacco, who was granted immediacy in 1110 by Holy Roman Emperor Henry V,<ref>Giusto Fontanini. {{Google books|929Oruf2qScC|Della Eloquenza italiana di monsignor Giusto Fontanini|page=274}}, vol. 3 (in Italian). R. Bernabò, 1736. pp 274-276.</ref><ref>Gian Guiseppe Liruti. {{Google books|swCiIpD6UeIC|Notizie delle vite ed opere scritte da' letterati del Friuli|page=27}}, vol. 4 (in Italian). Alvisopoli, 1830. p 27.</ref><ref>Novati, pp 15-16.</ref> but this has yet to be confirmed.<ref>Malipiero, p 80.</ref> |

Fiore wrote that he had a natural inclination to the martial arts and began training at a young age, ultimately studying with “countless” masters from both Italic and Germanic lands.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> He had ample opportunity to interact with both, being born in the Holy Roman Empire and later traveling widely in the northern Italian states. Unfortunately, not all of these encounters were friendly: Fiore wrote of meeting many “false” or unworthy masters in his travels, most of whom lacked even the limited skill he'd expect in a good student.<ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> He further mentions that on five separate occasions he was forced to fight [[duel]]s for his honor against certain of these masters who he described as envious because he refused to teach them his art; the duels were all fought with sharp [[longsword]]s, unarmored except for gambesons and chamois gloves, and he won each without injury.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty"/> | Fiore wrote that he had a natural inclination to the martial arts and began training at a young age, ultimately studying with “countless” masters from both Italic and Germanic lands.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> He had ample opportunity to interact with both, being born in the Holy Roman Empire and later traveling widely in the northern Italian states. Unfortunately, not all of these encounters were friendly: Fiore wrote of meeting many “false” or unworthy masters in his travels, most of whom lacked even the limited skill he'd expect in a good student.<ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> He further mentions that on five separate occasions he was forced to fight [[duel]]s for his honor against certain of these masters who he described as envious because he refused to teach them his art; the duels were all fought with sharp [[longsword]]s, unarmored except for gambesons and chamois gloves, and he won each without injury.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty"/> | ||

| − | Writing very little on his own career as a commander and master at arms, Fiore laid out his credentials for his readers in other ways. He stated that foremost among the masters who trained him was one [[Johannes Suvenus|Johane dicto Suueno]], who he notes was a disciple of [[Nicholai de Toblem]];<ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> unfortunately, both names are given in Latin so there is little we can conclude about them other than that they were probably among the Italians and Germans he alludes to, and that one or both were well | + | Writing very little on his own career as a commander and master at arms, Fiore laid out his credentials for his readers in other ways. He stated that foremost among the masters who trained him was one [[Johannes Suvenus|Johane dicto Suueno]], who he notes was a disciple of [[Nicholai de Toblem]];<ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> unfortunately, both names are given in Latin so there is little we can conclude about them other than that they were probably among the Italians and Germans he alludes to, and that one or both were well known in Fiore's time. He further offered an extensive list of the famous ''condottieri'' that he trained, including Piero Paolo del Verde (Peter von Grünen),<ref>[http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-v/2660-piero-del-verde “PIERO DEL VERDE (Paolo del Verde) Tedesco. Signore di Colle di Val d’Elsa.”]. ''Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 - 1550''. Retrieved 2012-02-08.</ref> Niccolo Unricilino (Nikolo von Urslingen),<ref>Leoni, p 7.</ref> Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli (Galeazzo Gonzaga da Mantova),<ref name="Galeazzo">[http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-m/1450-galeazzo-da-mantova “GALEAZZO DA MANTOVA (Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli, Galeazzo Gonzaga) Di Mantova. Secondo alcune fonti, di Grumello nel pavese.”]. ''Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 - 1550''. Retrieved 2012-02-08.</ref> Lancillotto Beccaria di Pavia,<ref>[http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-b/630-lancillotto-beccaria “LANCILLOTTO BECCARIA (Lanciarotto Beccaria) Di Pavia. Ghibellino. Signore di Serravalle Scrivia, Casei Gerola, Bassignana, Novi Ligure, Voghera, Broni.”]. ''Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 - 1550''. Retrieved 2012-02-08.</ref> Giovannino da Baggio di Milano,<ref name="Malipiero 9496">Malipiero, pp 94-96.</ref> and Azzone di Castelbarco,<ref name="Jens">[https://talhoffer.wordpress.com/2013/04/24/fiore-his-master-and-his-students/ Fiore his masters and his students]. ''Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau.'' Retrieved 2013-05-08.</ref> and also highlights some of their martial exploits.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty"/> |

| − | Based on Fiore's autobiographical account, he can tentatively be placed in Perosa (Perugia) in 1381 when Piero del Verde likely fought a duel with Pietro della Corona (Peter Kornwald).<ref>This is the only point when both men are known to have been in Perugia at the same time; Verde died soon after this in 1385. See [https://talhoffer.wordpress.com/2013/04/24/fiore-his-master-and-his-students/ Fiore his masters and his students]. ''Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau.'' in English and [http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-v/2660-piero-del-verde “PIERO DEL VERDE (Paolo del Verde) Tedesco. Signore di Colle di Val d’Elsa.”]. and [http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-c/971-pietro-della-corona “PIETRO DELLA CORONA (Pietro Cornuald) Tedesco. Signore di Angri.”]. ''Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 - 1550''. in Italian. Retrieved 2013-05-08.</ref> That same year, the Aquileian War of Succession erupted as a coalition of secular nobles from Udine and surrounding cities sought to remove the newly | + | Based on Fiore's autobiographical account, he can tentatively be placed in Perosa (Perugia) in 1381 when Piero del Verde likely fought a duel with Pietro della Corona (Peter Kornwald).<ref>This is the only point when both men are known to have been in Perugia at the same time; Verde died soon after this in 1385. See [https://talhoffer.wordpress.com/2013/04/24/fiore-his-master-and-his-students/ Fiore his masters and his students]. ''Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau.'' in English and [http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-v/2660-piero-del-verde “PIERO DEL VERDE (Paolo del Verde) Tedesco. Signore di Colle di Val d’Elsa.”]. and [http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-c/971-pietro-della-corona “PIETRO DELLA CORONA (Pietro Cornuald) Tedesco. Signore di Angri.”]. ''Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 - 1550''. in Italian. Retrieved 2013-05-08.</ref> That same year, the Aquileian War of Succession erupted as a coalition of secular nobles from Udine and surrounding cities sought to remove the newly appointed Patriarch, Philippe II d'Alençon. Fiore seems to have sided with the secular nobility against the Cardinal as in 1383 there is record of him being tasked by the grand council with inspection and maintenance on the [[artillery]] pieces defending Udine (including large crossbows and catapults).<ref name="Mondschein 11"/><ref>Malipiero, p 85.</ref><ref name="Easton">[[Matt Easton|Easton, Matt]]. “[http://www.fioredeiliberi.org/fiore/ Fiore dei Liberi - Fiore di Battaglia - Flos Duellatorum]”. London: Schola Gladiatoria, 2009. Retrieved 2012-02-08.</ref> There are also records of him working variously as a magistrate, peace officer, and agent of the grand council during the course of 1384, but after that the historical record is silent. The war continued until a new Patriarch was appointed in 1389 and a peace settlement was reached, but it's unclear if Fiore remained involved for the duration. Given that he appears in council records five times in 1384, it would be quite odd for him to be completely unmentioned over the subsequent five years,<ref name="Mondschein 11"/><ref>Malipiero, pp 85-88.</ref> and since his absence after May of 1384 coincides with a proclamation in July of that year demanding that Udine cease hostilities or face harsh repercussions, it seems more likely that he moved on. |

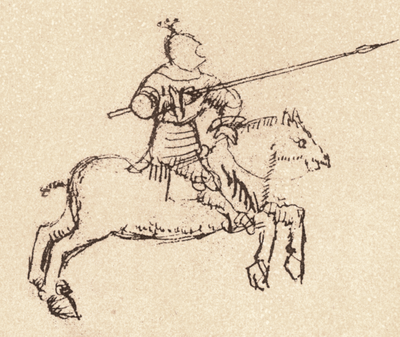

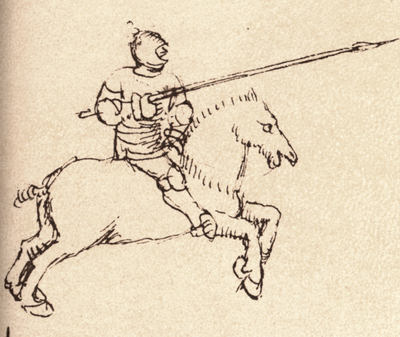

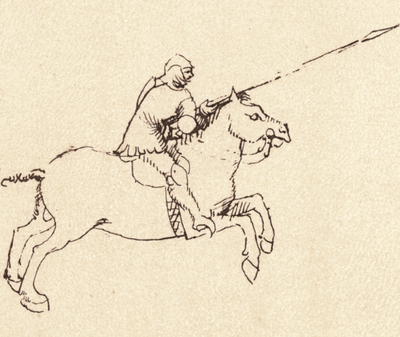

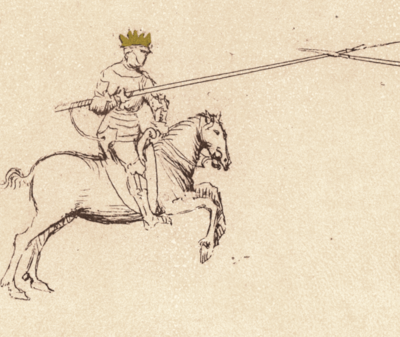

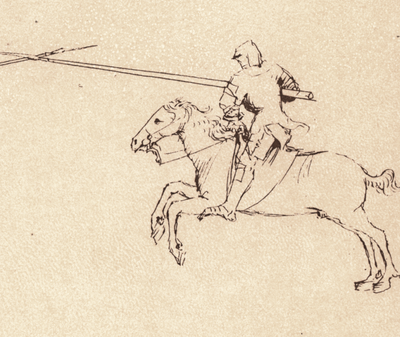

After the war, Fiore seems to have traveled a good deal in northern Italy, teaching fencing and training men for duels. In 1395, he can be placed in Padua training the mercenary captain Galeazzo Gonzaga of Mantua for a duel with the French marshal Jean II le Maingre (who went by the war name “Boucicaut”). Galeazzo made the challenge when Boucicaut called into question the valor of Italians at the royal court of France, and the duel was ultimately set for Padua on 15 August. Both Francesco Novello da Carrara, Lord of Padua, and Francesco Gonzaga, Lord of Mantua, were in attendance. The duel was to begin with [[spear]]s on [[:category:Mounted Fencing|horseback]], but Boucicaut became impatient and dismounted, attacking Galeazzo before he could mount his own horse. Galeazzo landed a solid blow on the Frenchman’s helmet, but was subsequently disarmed. At this point, Boucicaut called for his poleaxe but the lords intervened to end the duel.<ref>Malipiero, pp 55-58.</ref><ref name="Easton"/><ref name="Galeazzo"/> | After the war, Fiore seems to have traveled a good deal in northern Italy, teaching fencing and training men for duels. In 1395, he can be placed in Padua training the mercenary captain Galeazzo Gonzaga of Mantua for a duel with the French marshal Jean II le Maingre (who went by the war name “Boucicaut”). Galeazzo made the challenge when Boucicaut called into question the valor of Italians at the royal court of France, and the duel was ultimately set for Padua on 15 August. Both Francesco Novello da Carrara, Lord of Padua, and Francesco Gonzaga, Lord of Mantua, were in attendance. The duel was to begin with [[spear]]s on [[:category:Mounted Fencing|horseback]], but Boucicaut became impatient and dismounted, attacking Galeazzo before he could mount his own horse. Galeazzo landed a solid blow on the Frenchman’s helmet, but was subsequently disarmed. At this point, Boucicaut called for his poleaxe but the lords intervened to end the duel.<ref>Malipiero, pp 55-58.</ref><ref name="Easton"/><ref name="Galeazzo"/> | ||

| − | Fiore surfaces again in Pavia in 1399, this time training Giovannino da Baggio for a duel with a German squire named Sirano. It was fought on | + | Fiore surfaces again in Pavia in 1399, this time training Giovannino da Baggio for a duel with a German squire named Sirano. It was fought on 24 June and attended by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, as well as the Duchess and other nobles. The duel was to consist of three bouts of mounted lance followed by three bouts each of dismounted [[poleaxe]], [[estoc]], and [[dagger]]. They ultimately rode two additional passes and on the fifth, Baggio impaled Sirano’s horse through the chest, slaying the horse but losing his lance in the process. They fought the other nine bouts as scheduled, and due to the strength of their armor (and the fact that all of the weapons were blunted), both combatants reportedly emerged from these exchanges unharmed.<ref name="Malipiero 9496"/><ref name="Mondschein 12">[[Ken Mondschein|Mondschein]], p 12.</ref> |

Fiore was likely involved in at least one other duel that year, that of his final student Azzone di Castelbarco and Giovanni degli Ordelaffi, as the latter is known to have died in 1399.<ref>Malipiero, p 97.</ref> After Castelbarco’s duel, Fiore’s activities are unclear. Based on the allegiances of the nobles that he trained in the 1390s, he seems to have been associated with the ducal court of Milan in the latter part of his career.<ref name="Easton"/> Some time in the first years of the 1400s, Fiore composed a fencing treatise in Italian and Latin called "The Flower of Battle" (rendered variously as ''Fior di Battaglia'', ''Florius de Arte Luctandi'', and ''Flos Duellatorum''). The briefest version of the text is dated to 1409 and indicates that it was a labor of six months and great personal effort;<ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> as evidence suggests that two longer versions were composed some time before this,<ref>Fiore states in the preface to the [[Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)|Pisani Dossi MS]] that he had studied combat for fifty years, whereas the comparable statement in the [[Fior di Battaglia (MS M.383)|MS M.383]] and [[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|MS Ludwig.XV.13]] mention the slightly shorter "forty years and more".</ref> we may assume that he devoted a considerable amount of time to writing during this decade. | Fiore was likely involved in at least one other duel that year, that of his final student Azzone di Castelbarco and Giovanni degli Ordelaffi, as the latter is known to have died in 1399.<ref>Malipiero, p 97.</ref> After Castelbarco’s duel, Fiore’s activities are unclear. Based on the allegiances of the nobles that he trained in the 1390s, he seems to have been associated with the ducal court of Milan in the latter part of his career.<ref name="Easton"/> Some time in the first years of the 1400s, Fiore composed a fencing treatise in Italian and Latin called "The Flower of Battle" (rendered variously as ''Fior di Battaglia'', ''Florius de Arte Luctandi'', and ''Flos Duellatorum''). The briefest version of the text is dated to 1409 and indicates that it was a labor of six months and great personal effort;<ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> as evidence suggests that two longer versions were composed some time before this,<ref>Fiore states in the preface to the [[Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)|Pisani Dossi MS]] that he had studied combat for fifty years, whereas the comparable statement in the [[Fior di Battaglia (MS M.383)|MS M.383]] and [[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|MS Ludwig.XV.13]] mention the slightly shorter "forty years and more".</ref> we may assume that he devoted a considerable amount of time to writing during this decade. | ||

| Line 74: | Line 74: | ||

Four [[illuminated manuscript]] copies of this treatise are currently known to exist (as well as a 17th century fragment), and there are records of at least two others whose current locations are unknown.<ref>The Codex LXXXIV (or MS 84) consisted of 58 folia bound in leather with a clasp, and whose first page showed a white eagle and two helmets; the Codex CX (or MS 110) was a small, unbound volume consisting of only 15 folia. See Novati, pp 29-30. It is conceivable that one of the four extant versions is the MS 84, but no evidence in support of this proposition has yet surfaced.</ref> The MS Ludwig XV 13 and the Pisani Dossi MS are both dedicated to Niccolò III d'Este and state that they were written at his request and according to his design. The MS M.383, on the other hand, lacks a dedication and claims to have been laid out according to his own intelligence while the MSS Latin 11269 lost any dedication it might have had along with its prologue. Each of the extant copies of ''the Flower of Battle'' follows a distinct order, though both of these pairs contain strong similarities to each other in order of presentation. In addition, Philippo di Vadi's manuscript from the 1480s, whose second half is essentially a redaction of ''the Flower of Battle'', provides a valuable fifth point of reference when considering Fiore's teachings. | Four [[illuminated manuscript]] copies of this treatise are currently known to exist (as well as a 17th century fragment), and there are records of at least two others whose current locations are unknown.<ref>The Codex LXXXIV (or MS 84) consisted of 58 folia bound in leather with a clasp, and whose first page showed a white eagle and two helmets; the Codex CX (or MS 110) was a small, unbound volume consisting of only 15 folia. See Novati, pp 29-30. It is conceivable that one of the four extant versions is the MS 84, but no evidence in support of this proposition has yet surfaced.</ref> The MS Ludwig XV 13 and the Pisani Dossi MS are both dedicated to Niccolò III d'Este and state that they were written at his request and according to his design. The MS M.383, on the other hand, lacks a dedication and claims to have been laid out according to his own intelligence while the MSS Latin 11269 lost any dedication it might have had along with its prologue. Each of the extant copies of ''the Flower of Battle'' follows a distinct order, though both of these pairs contain strong similarities to each other in order of presentation. In addition, Philippo di Vadi's manuscript from the 1480s, whose second half is essentially a redaction of ''the Flower of Battle'', provides a valuable fifth point of reference when considering Fiore's teachings. | ||

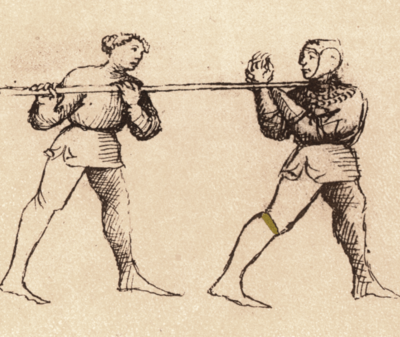

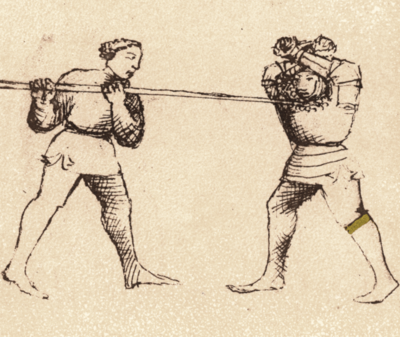

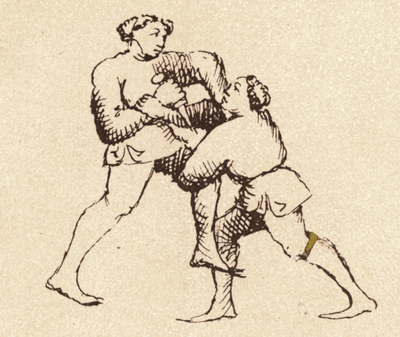

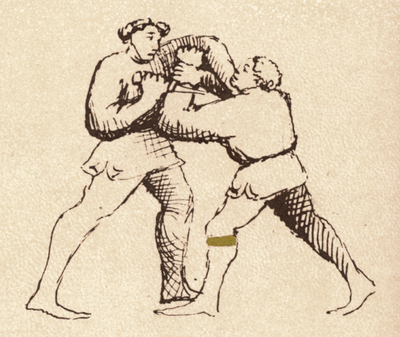

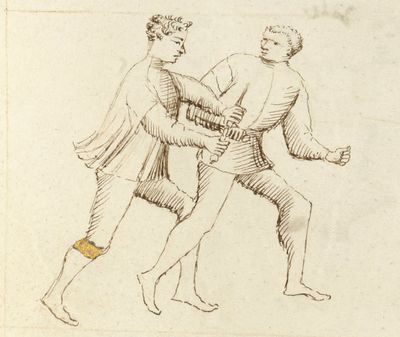

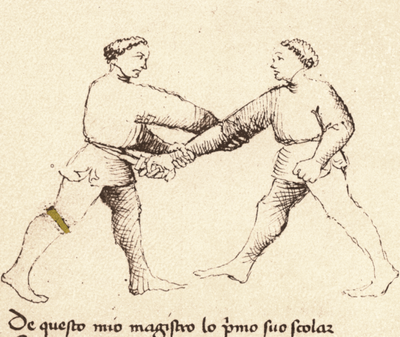

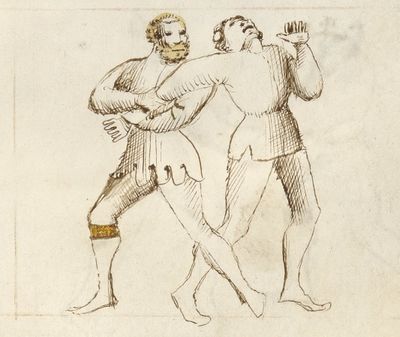

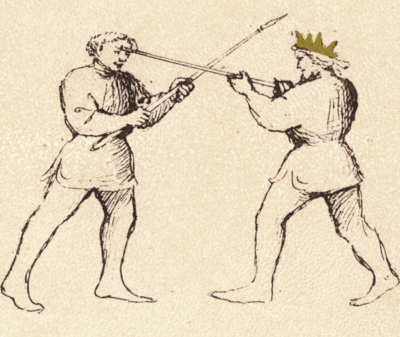

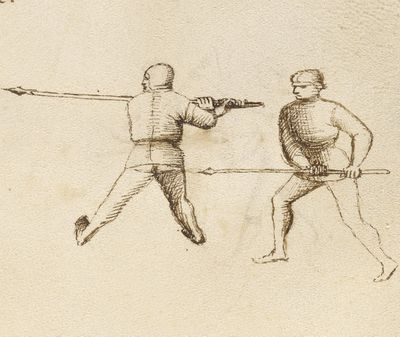

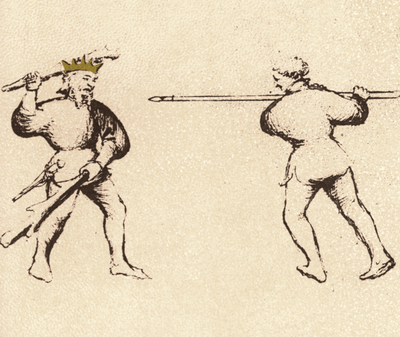

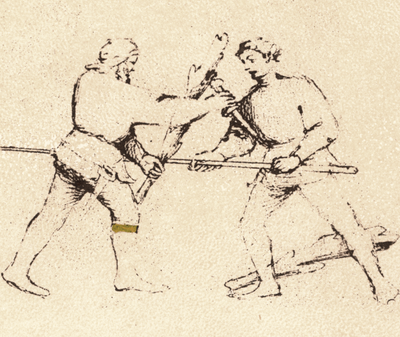

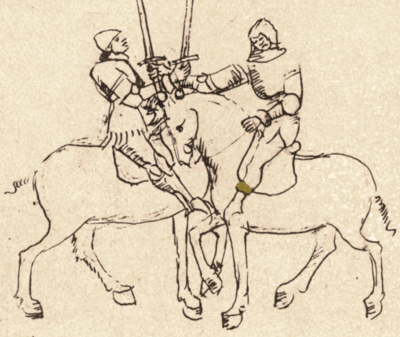

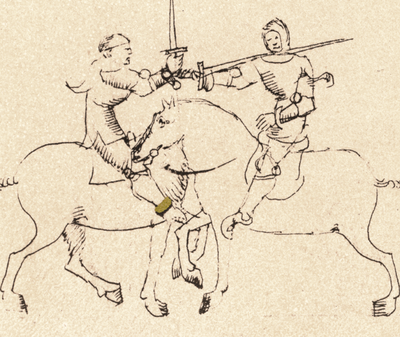

| − | The major sections of the work include: ''abrazare'' or [[grappling]]; ''[[dagger|daga]]'', including both unarmed defenses against the dagger and plays of dagger against dagger; ''spada a un mano'', the use of the [[longsword]] in one hand (also called "the sword without the buckler"); ''spada a dui mani'', the use of the | + | The major sections of the work include: ''abrazare'' or [[grappling]]; ''[[dagger|daga]]'', including both unarmed defenses against the dagger and plays of dagger against dagger; ''spada a un mano'', the use of the [[longsword|sword]] in one hand (also called "the sword without the buckler"); ''spada a dui mani'', the use of the sword in two hands; ''spada en arme'', the use of the sword in [[armor]] (primarily techniques from the [[halfsword|shortened sword]]); ''azza'', plays of the [[poleaxe]] in armor; ''lancia'', [[spear]] and staff plays; and mounted combat (including the spear, the longsword, and mounted grappling). Brief bridging sections serve to connect each of these, covering such topics as ''bastoncello'', or plays of a [[club (weapon)|small stick or baton]] against unarmed and dagger-wielding opponents; plays of longsword vs. dagger; plays of staff and dagger and of two clubs and a dagger; and the use of the [[spear|chiavarina]] against a man on horseback. |

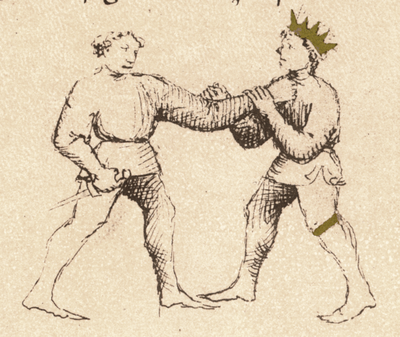

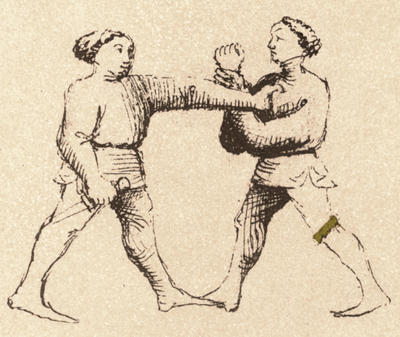

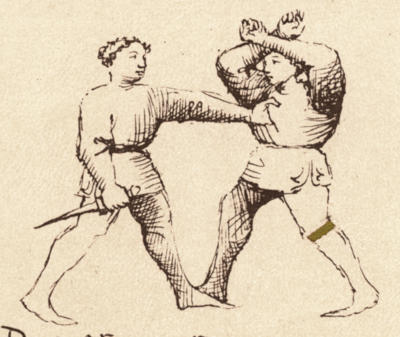

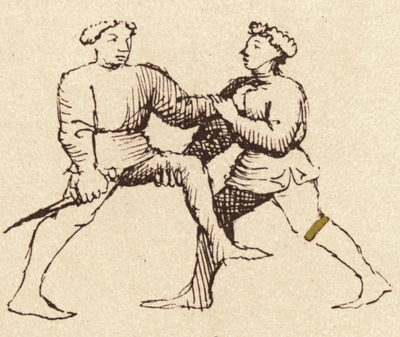

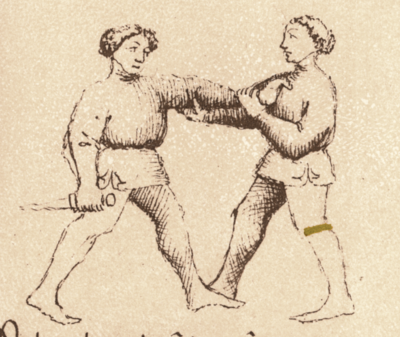

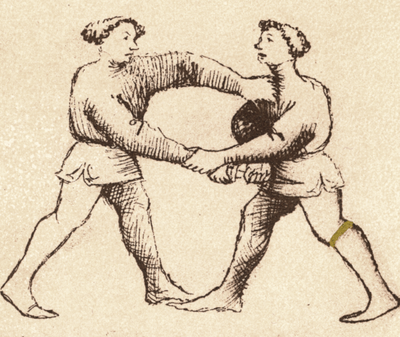

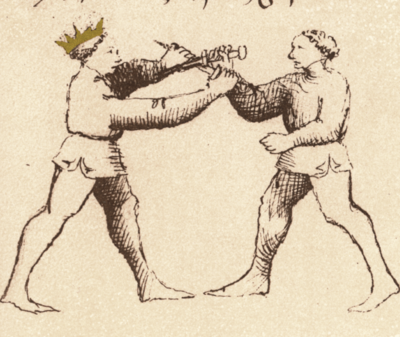

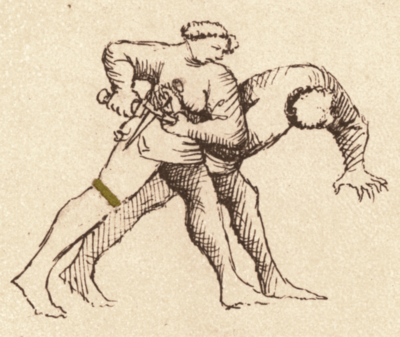

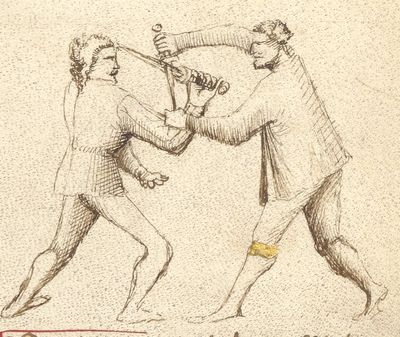

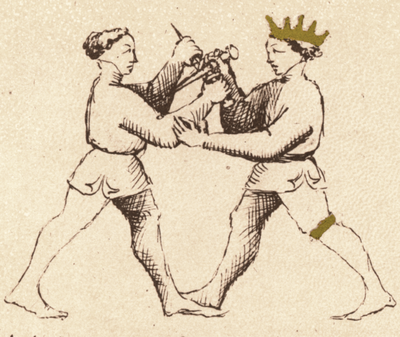

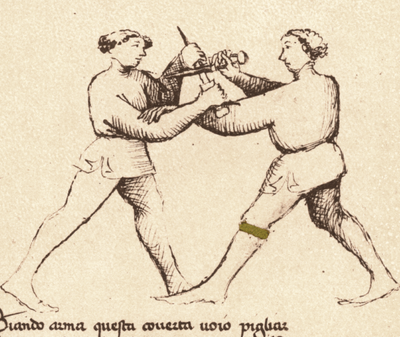

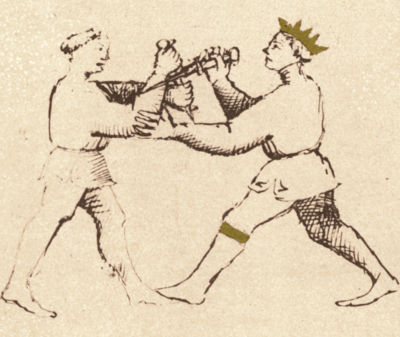

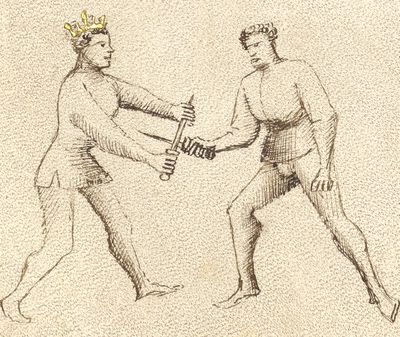

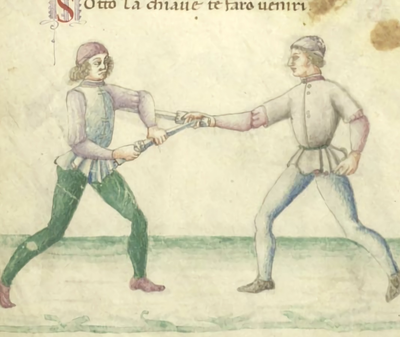

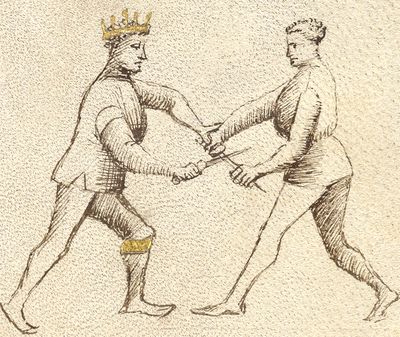

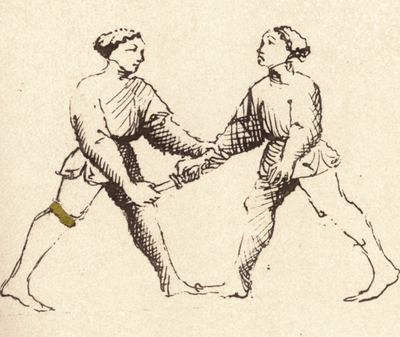

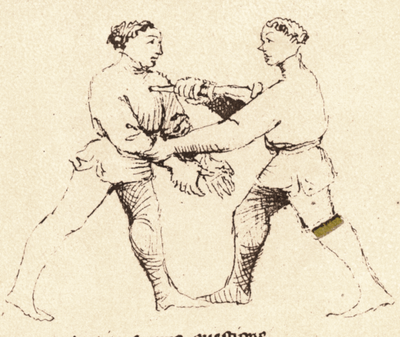

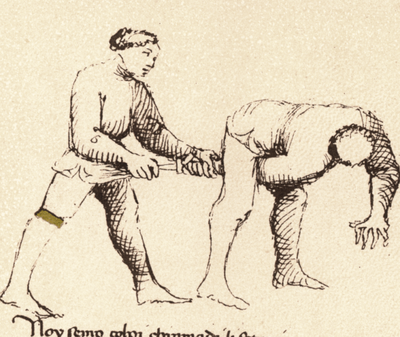

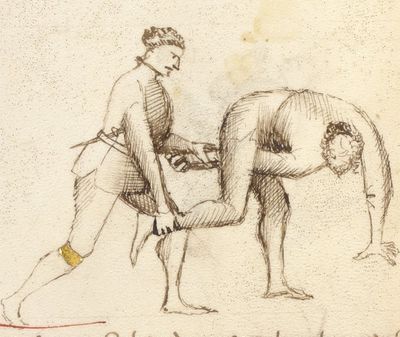

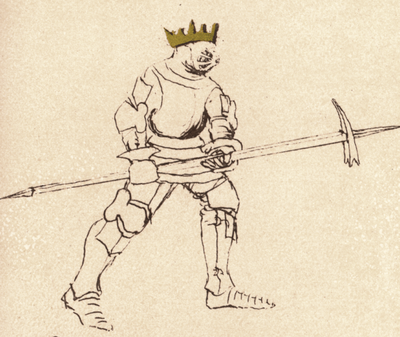

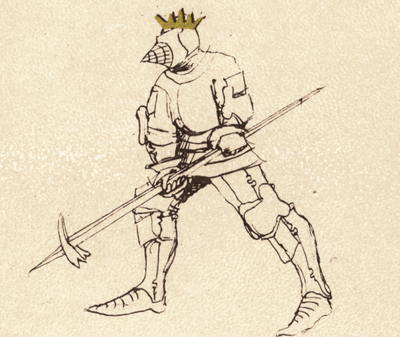

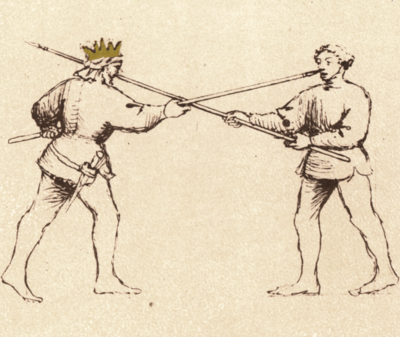

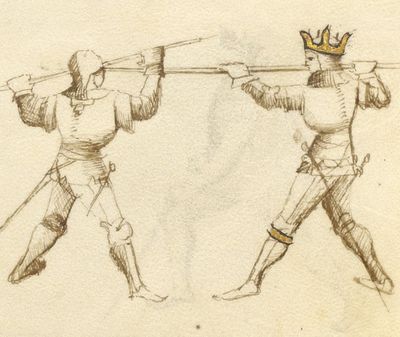

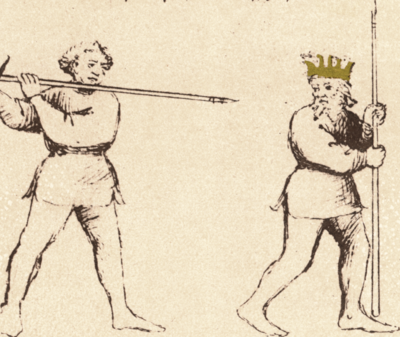

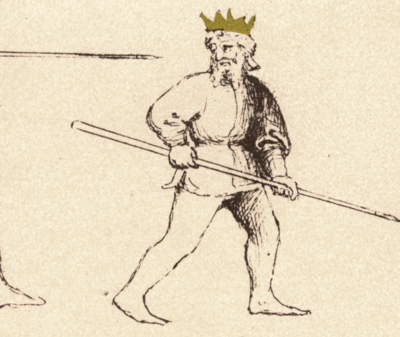

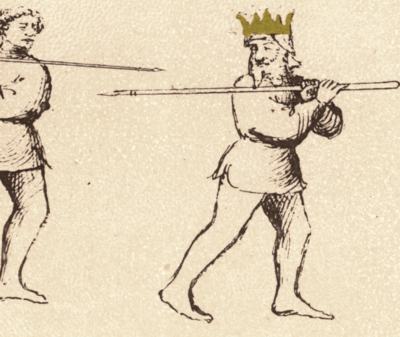

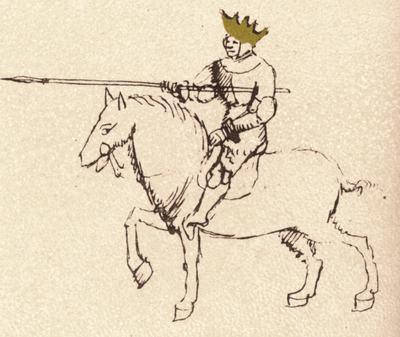

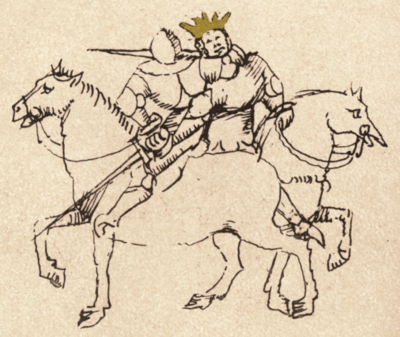

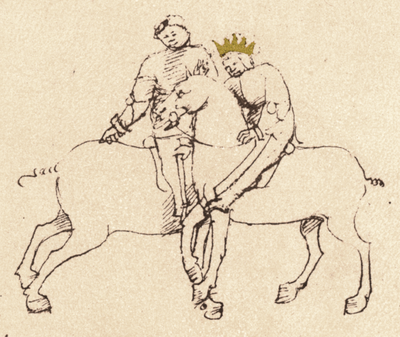

| − | The format of instruction is largely consistent across all copies of the treatise. Each section begins with a group of Masters or Teachers, figures in golden crowns each | + | The format of instruction is largely consistent across all copies of the treatise. Each section begins with a group of Masters (or Teachers), figures in golden crowns who each demonstrate a particular guard for use with their weapon. These are followed by a master called "Remedio" (remedy) who demonstrates a defensive technique against some basic attack (usually how to use one of the listed guards to defend), and then by his various Scholars (or Students), figures wearing golden garters on their legs who demonstrate iterations and variations of this remedy. After the scholars there is typically a master called "Contrario" (counter), wearing both crown and garter, who demonstrates how to counter the master's remedy (and those of his scholars), who is likewise sometimes followed by his own scholars in garters. In rare cases, a fourth type of master appears called "Contra-Contrario" (counter-counter), who likewise wears the crown and garter and demonstrates how to defeat the master's counter. Some sections feature multiple master remedies or master counters, while some have only one. There are also many cases in which an image in one manuscript will only feature a scholar's garter where the corresponding image in another also includes a master's crown. Depending on the instance, this may either be intentional or merely an error in the art. |

The concordance below includes Zeno's transcription of the Getty preface for reference, and then drops the (thereafter empty) column in favor of a second image column for the main body of the treatise. Generally only the right-side image column will contain illustrations—the left-side column will only contain additional content when when the text describes an image that spans the width of the page in the manuscripts, or when there are significant discrepancies between the available illustrations (in such cases, they sometimes display two stages of the same technique and will be placed in "chronological" order if possible). There are likewise two translation columns, with the the two manuscripts dedicated to Niccolò on the left and the two undedicated manuscripts on the right; in both columns, the short text of the PD and Paris will come first, followed by the longer paragraphs of the Getty and Morgan. | The concordance below includes Zeno's transcription of the Getty preface for reference, and then drops the (thereafter empty) column in favor of a second image column for the main body of the treatise. Generally only the right-side image column will contain illustrations—the left-side column will only contain additional content when when the text describes an image that spans the width of the page in the manuscripts, or when there are significant discrepancies between the available illustrations (in such cases, they sometimes display two stages of the same technique and will be placed in "chronological" order if possible). There are likewise two translation columns, with the the two manuscripts dedicated to Niccolò on the left and the two undedicated manuscripts on the right; in both columns, the short text of the PD and Paris will come first, followed by the longer paragraphs of the Getty and Morgan. | ||

Revision as of 20:27, 29 December 2013

| Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi | |

|---|---|

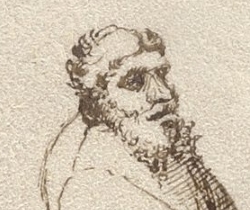

This master with a forked bear appears sporadically throughout both the Getty and Pisani Dossi mss., and may be a representation of Fiore himself. | |

| Born | 1340s Cividale del Friuli, Friuli |

| Died | after 1420 France (?) |

| Relative(s) | Benedetto de’i Liberi |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Friulian |

| Patron |

|

| Influences | |

| Influenced | Philippo di Vadi |

| Genres | |

| Language | |

| Notable work(s) | The Flower of Battle |

| Manuscript(s) |

Pisani Dossi MS (1409)

|

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi de Cividale d’Austria (Fiore delli Liberi, Fiore Furlano, Fiore de Cividale d’Austria; ca. 1340s - 1420s[1]) was a late 14th century knight, diplomat, and itinerant fencing master. He was born in Cividale del Friuli, a town in the Patriarchal State of Aquileia (in the Friuli region of modern-day Italy), the son of Benedetto and scion of a Liberi house of Premariacco.[2][3][4] The term Liberi, while potentially merely a surname, more probably indicates that his family had Imperial immediacy (Reichsfreiheit), either as part of the nobili liberi (Edelfrei, "free nobles"), the Germanic unindentured knightly class which formed the lower tier of nobility in the Middle Ages, or possibly of the rising class of Imperial Free Knights.[5][6][7] It has been suggested by various historians that Fiore and Benedetto were descended from Cristallo dei Liberi of Premariacco, who was granted immediacy in 1110 by Holy Roman Emperor Henry V,[8][9][10] but this has yet to be confirmed.[11]

Fiore wrote that he had a natural inclination to the martial arts and began training at a young age, ultimately studying with “countless” masters from both Italic and Germanic lands.[2][3][4] He had ample opportunity to interact with both, being born in the Holy Roman Empire and later traveling widely in the northern Italian states. Unfortunately, not all of these encounters were friendly: Fiore wrote of meeting many “false” or unworthy masters in his travels, most of whom lacked even the limited skill he'd expect in a good student.[4] He further mentions that on five separate occasions he was forced to fight duels for his honor against certain of these masters who he described as envious because he refused to teach them his art; the duels were all fought with sharp longswords, unarmored except for gambesons and chamois gloves, and he won each without injury.[2][3]

Writing very little on his own career as a commander and master at arms, Fiore laid out his credentials for his readers in other ways. He stated that foremost among the masters who trained him was one Johane dicto Suueno, who he notes was a disciple of Nicholai de Toblem;[4] unfortunately, both names are given in Latin so there is little we can conclude about them other than that they were probably among the Italians and Germans he alludes to, and that one or both were well known in Fiore's time. He further offered an extensive list of the famous condottieri that he trained, including Piero Paolo del Verde (Peter von Grünen),[12] Niccolo Unricilino (Nikolo von Urslingen),[13] Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli (Galeazzo Gonzaga da Mantova),[14] Lancillotto Beccaria di Pavia,[15] Giovannino da Baggio di Milano,[16] and Azzone di Castelbarco,[17] and also highlights some of their martial exploits.[2][3]

Based on Fiore's autobiographical account, he can tentatively be placed in Perosa (Perugia) in 1381 when Piero del Verde likely fought a duel with Pietro della Corona (Peter Kornwald).[18] That same year, the Aquileian War of Succession erupted as a coalition of secular nobles from Udine and surrounding cities sought to remove the newly appointed Patriarch, Philippe II d'Alençon. Fiore seems to have sided with the secular nobility against the Cardinal as in 1383 there is record of him being tasked by the grand council with inspection and maintenance on the artillery pieces defending Udine (including large crossbows and catapults).[6][19][20] There are also records of him working variously as a magistrate, peace officer, and agent of the grand council during the course of 1384, but after that the historical record is silent. The war continued until a new Patriarch was appointed in 1389 and a peace settlement was reached, but it's unclear if Fiore remained involved for the duration. Given that he appears in council records five times in 1384, it would be quite odd for him to be completely unmentioned over the subsequent five years,[6][21] and since his absence after May of 1384 coincides with a proclamation in July of that year demanding that Udine cease hostilities or face harsh repercussions, it seems more likely that he moved on.

After the war, Fiore seems to have traveled a good deal in northern Italy, teaching fencing and training men for duels. In 1395, he can be placed in Padua training the mercenary captain Galeazzo Gonzaga of Mantua for a duel with the French marshal Jean II le Maingre (who went by the war name “Boucicaut”). Galeazzo made the challenge when Boucicaut called into question the valor of Italians at the royal court of France, and the duel was ultimately set for Padua on 15 August. Both Francesco Novello da Carrara, Lord of Padua, and Francesco Gonzaga, Lord of Mantua, were in attendance. The duel was to begin with spears on horseback, but Boucicaut became impatient and dismounted, attacking Galeazzo before he could mount his own horse. Galeazzo landed a solid blow on the Frenchman’s helmet, but was subsequently disarmed. At this point, Boucicaut called for his poleaxe but the lords intervened to end the duel.[22][20][14]

Fiore surfaces again in Pavia in 1399, this time training Giovannino da Baggio for a duel with a German squire named Sirano. It was fought on 24 June and attended by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, as well as the Duchess and other nobles. The duel was to consist of three bouts of mounted lance followed by three bouts each of dismounted poleaxe, estoc, and dagger. They ultimately rode two additional passes and on the fifth, Baggio impaled Sirano’s horse through the chest, slaying the horse but losing his lance in the process. They fought the other nine bouts as scheduled, and due to the strength of their armor (and the fact that all of the weapons were blunted), both combatants reportedly emerged from these exchanges unharmed.[16][23]

Fiore was likely involved in at least one other duel that year, that of his final student Azzone di Castelbarco and Giovanni degli Ordelaffi, as the latter is known to have died in 1399.[24] After Castelbarco’s duel, Fiore’s activities are unclear. Based on the allegiances of the nobles that he trained in the 1390s, he seems to have been associated with the ducal court of Milan in the latter part of his career.[20] Some time in the first years of the 1400s, Fiore composed a fencing treatise in Italian and Latin called "The Flower of Battle" (rendered variously as Fior di Battaglia, Florius de Arte Luctandi, and Flos Duellatorum). The briefest version of the text is dated to 1409 and indicates that it was a labor of six months and great personal effort;[4] as evidence suggests that two longer versions were composed some time before this,[25] we may assume that he devoted a considerable amount of time to writing during this decade.

Beyond this, nothing certain is known of Fiore's activities in the 15th century. Francesco Novati and D. Luigi Zanutto both assume that some time before 1409 he accepted an appointment as court fencing master to Niccolò III d’Este, Marquis of Ferrara, Modena, and Parma; presumably he would have made this change when Milan fell into disarray in 1402, though Zanutto went so far as to speculate that he trained Niccolò for his 1399 passage at arms.[26] However, while two surviving copies of "the Flower of Battle" are dedicated to the marquis, it seems more likely that the manuscripts were written as a diplomatic gift to Ferrara from Milan when they made peace in 1404.[23][20] C. A. Blengini di Torricella stated that late in life he made his way to Paris, France, where he could be placed teaching fencing in 1418 and creating a copy of a fencing manual located there in 1420. Though he attributes these facts to Novati, no publication verifying them has yet been located.[27] The time and place of Fiore's death remain unknown.

Despite the depth and complexity of his writings, Fiore de’i Liberi does not seem to have been a very significant master in the development of Italian fencing. That field was instead dominated by the tradition of his near-contemporary the Bolognese master Filippo di Bartolomeo Dardi. Even so, there are a number of later treatises which bear strong resemblance to his work, including the writings of Philippo di Vadi and Ludwig VI von Eyb. This may be due to the direct influence of Fiore or his writings, or it may instead indicate that the older tradition of Johane and Nicholai survived and spread outside of his direct line.

Contents

Treatise

Four illuminated manuscript copies of this treatise are currently known to exist (as well as a 17th century fragment), and there are records of at least two others whose current locations are unknown.[28] The MS Ludwig XV 13 and the Pisani Dossi MS are both dedicated to Niccolò III d'Este and state that they were written at his request and according to his design. The MS M.383, on the other hand, lacks a dedication and claims to have been laid out according to his own intelligence while the MSS Latin 11269 lost any dedication it might have had along with its prologue. Each of the extant copies of the Flower of Battle follows a distinct order, though both of these pairs contain strong similarities to each other in order of presentation. In addition, Philippo di Vadi's manuscript from the 1480s, whose second half is essentially a redaction of the Flower of Battle, provides a valuable fifth point of reference when considering Fiore's teachings.

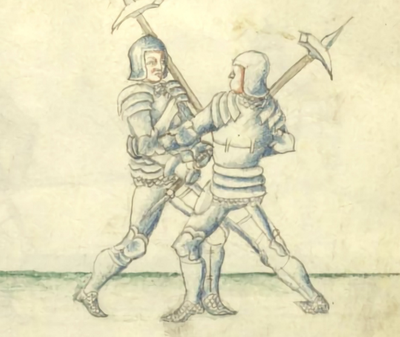

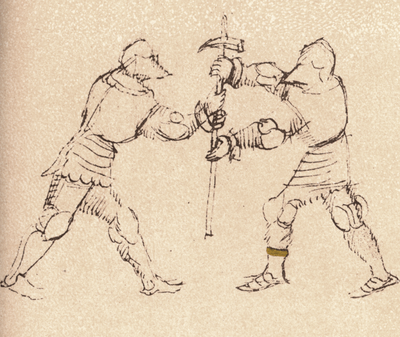

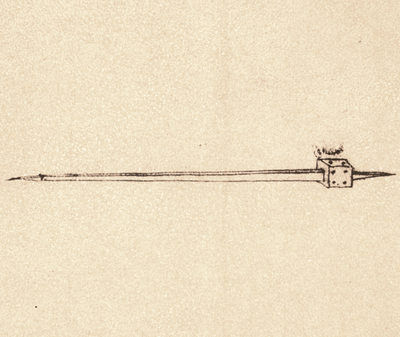

The major sections of the work include: abrazare or grappling; daga, including both unarmed defenses against the dagger and plays of dagger against dagger; spada a un mano, the use of the sword in one hand (also called "the sword without the buckler"); spada a dui mani, the use of the sword in two hands; spada en arme, the use of the sword in armor (primarily techniques from the shortened sword); azza, plays of the poleaxe in armor; lancia, spear and staff plays; and mounted combat (including the spear, the longsword, and mounted grappling). Brief bridging sections serve to connect each of these, covering such topics as bastoncello, or plays of a small stick or baton against unarmed and dagger-wielding opponents; plays of longsword vs. dagger; plays of staff and dagger and of two clubs and a dagger; and the use of the chiavarina against a man on horseback.

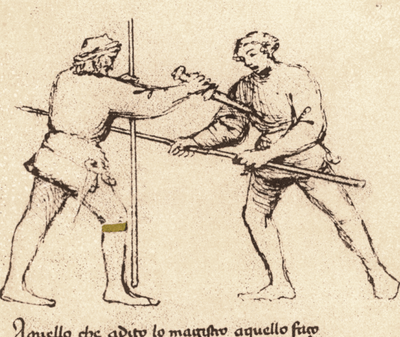

The format of instruction is largely consistent across all copies of the treatise. Each section begins with a group of Masters (or Teachers), figures in golden crowns who each demonstrate a particular guard for use with their weapon. These are followed by a master called "Remedio" (remedy) who demonstrates a defensive technique against some basic attack (usually how to use one of the listed guards to defend), and then by his various Scholars (or Students), figures wearing golden garters on their legs who demonstrate iterations and variations of this remedy. After the scholars there is typically a master called "Contrario" (counter), wearing both crown and garter, who demonstrates how to counter the master's remedy (and those of his scholars), who is likewise sometimes followed by his own scholars in garters. In rare cases, a fourth type of master appears called "Contra-Contrario" (counter-counter), who likewise wears the crown and garter and demonstrates how to defeat the master's counter. Some sections feature multiple master remedies or master counters, while some have only one. There are also many cases in which an image in one manuscript will only feature a scholar's garter where the corresponding image in another also includes a master's crown. Depending on the instance, this may either be intentional or merely an error in the art.

The concordance below includes Zeno's transcription of the Getty preface for reference, and then drops the (thereafter empty) column in favor of a second image column for the main body of the treatise. Generally only the right-side image column will contain illustrations—the left-side column will only contain additional content when when the text describes an image that spans the width of the page in the manuscripts, or when there are significant discrepancies between the available illustrations (in such cases, they sometimes display two stages of the same technique and will be placed in "chronological" order if possible). There are likewise two translation columns, with the the two manuscripts dedicated to Niccolò on the left and the two undedicated manuscripts on the right; in both columns, the short text of the PD and Paris will come first, followed by the longer paragraphs of the Getty and Morgan.

[] Images |

Illustrations |

Completed Translation (from the Getty and PD) |

Draft Translation (from the Paris) |

Morgan Transcription (1400s) |

Getty Transcription (1400s) |

Pisani Dossi Transcription (1409) |

Paris Transcription (1420s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[66] I want each of my students to know I am the Fifth Dagger Remedy Master who defends against the collar grab made by this player. Before he can strike me with his dagger I destroy his arm like this, because the grip he has on me is actually to my advantage. And I can do all of the covers, holds and binds of the other remedy masters and their students who came before me. And I say this from experience: all who study this art should be aware that you cannot successfully defend the collar grab unless you move quickly. |

You would grasp my chest. Thus far you have not been able to wound me. |

[38r-d] ¶ Io son Quinto Re Magistro per lo cavezzo tenudo di questo zugadore. Inanzi ch'ello mi traga cum sua daga, per questo modo gli guasto lo brazo, per che lo tenir ch'ello mi tene a mi e grande avantazo. Che io posso far tutte coverte prese e ligadure degl'altri magistri rimedii e di lor scolari che sono dinançi. Lo proverbio parla per exempio. Io voglio che ogn'un'ch'a scolaro in quest'arte sazza, che presa di cavezo nissuna deffesa no impaça. |

[10a-e] Io voio che çaschadun de mi magistro saça |

[33v-d] ¶ Pectore me prendis. Nec adhuc mihi ledere posses. | |||

[67] After striking against your elbow, I will continue on This is another way to destroy the arm. And from this play I can move to other plays and holds… |

I would now strike close by your elbow. You will then move past me, |

[38v-a] ¶ Questo e un altro modo di guastarte lo brazzo. E per venir in altri zoghi q e prese, io questo zogho fazo. Anchora digo che se fossi afferradi d'una lanza cum tal firir in lei, overo che me disferraria, overo che l'asta del ferro io partiria. |

[10a-f] Per questo ferire apresso el tuo cubito me conven lassar |

[34r-b] ¶ Te prope nunc cubitum feriam. me deinde relinques. | |||

[68] I will get rid of your spear with my arms in this way, …Also, if you are pinned by a spear then by making this strike against it you will either unpin yourself or break off the haft from the spearhead. |

[16b-d] Cum li braçi a'questo modo me voio disferare |

||||||

[69] If I want to get this spear off me, This is another way to make you let go, and is also a better method of breaking off the head of a spear… |

[38v-b] ¶ Questo e un altro far lassar anchora e meglor da disferar una lanza. Anchora digo che se cum forza io ti fiero in la zuntura dela man che mi tene per lo cavezzo, Io mi tegno certo che io te la dislogaro, se tu non la fuzi via. Lo contrario io lo voglio palentare. In quello che lo scolar vene zo cum gli brazzi per dislogar la mane delo zugadore, subito lo zugadore de tore via la mano del cavezzo delo scolar. E subito cum la daga in lo petto lo po guastar. |

[16b-c] Si de questa lança me voio disferare |

|||||

[70] By striking to your wrist or to your elbow, …Also if I strike you hard in the wrist joint of the hand holding my collar, I am certain to dislocate it unless you let go. I wish to tell you the counter. As the student strikes down with his arms to dislodge the player's hand, the player quickly withdraws his hand from the student’s collar, and he then quickly strikes the student in the chest with his dagger. |

Either I will strike over the elbow, or near the fist, |

[10b-a] Apresso tuo pugno feriro o sopra el cubito |

[34r-d] ¶ Vel supra cubitum feriam vel deprope pugnum. | ||||

[71] I am confident and certain that you will go to the ground, This play will make you let go of me. And in addition, if I advance my right foot behind your left foot, you will be thrown to the ground without fail. And if this play is not enough, I will try others on your dagger, because my heart and my eyes are never focused anywhere other than upon taking away your dagger quickly and without delay. |

I am able to safely believe that you will go into the ground now; |

[38v-c] ¶ Per questo modo in terra ti voglio butare inanzi che la daga mi vegna aproximare. E si la daga tua sara a'mezo camm per me ferire, Le prese ch'i'o lassaro e la tua daga voro seguire. Che tu no mi pora offender per modo che sia, che cum li zoghi deli rimedii ti faro vilania. |

[10b-c] De andar in terra tentene certo e seguro |

[34v-d] ¶ Tutus ut in terram nunc vadas, credere possum. | |||

[72] I choose to try this method of throwing you to the ground, I will throw you to the ground like this, before your dagger can get near me. And if your dagger comes down the center line to strike at me, I will release my grip and deal with your dagger, so that you will not be able to injure me in any way. Then with the remedy plays I will make you suffer. |

I put to the test where I would at once lay you sharply on your back.[30] |

[38v-d] ¶ Questo e un zogho di farse lassar, Salvo che si lo mio pe dritto dredo lo tuo stancho io faczo[!] avanzare, tu porissi andar in terra senza fallo. E si questo zogho a mi non basta, Cum altri, dela tua daga ti faro una tasta. Pero che'l mio chore e'l'ochio altro non guarda, che a tor ti la daga senza dimora e tarda. |

[10b-b] Per riverssarte in terra io voio provare aquesto modo |

||||

[73] You will find out that over my right shoulder This player had me grabbed by the collar, but before he could strike me with his dagger I quickly seized his left hand with my hands and pulled his arm over my shoulder so as to dislocate it, and then I completely dislocated it. But this play is safer to do in armor than unarmored. |

I will not have been cheated of breaking the left shoulder;[32] |

[15r-a] ¶ Questo zugadore mi tegniva per lo cavezzo. & io subito inanzi che ello tressi cum la daga, cum ambe le mie man presi la sua man stancha. E'l so brazzo stancho zitai sopra lo mio dritto per dislogargli lo ditto brazzo. Che ben gl'elo del tutto dislogado. Questo faria piu siguro armado che disarmado. |

[10b-d] Tu senti che sopra la mia drita spalla |

[35r-b] ¶ Non deceptus ero levum frangendo lacertum. | |||

[74] By the way I seize you and hold you, In this way I will hurl you to the ground without fail. And I will surely take your dagger. And if you are armored that may help you, since I will be aiming to take your life with your own dagger. But even if we are armoured, this art will not fail me. And if you are unarmored and very quick, other plays can be made besides this one. [In the Getty and Paris, the Scholar's right foot is inside (in front) of his opponent's left leg.] |

I hold you using this form, and I will catch the lamenting one; |

[15r-b] ¶ In questo modo te zitiro per terra che non mi po fallire. E la tua daga prendero a non mentire. Se tu saray armado, lo te pora zovare, che cum quella propia ti toro la vita. Se noii semo armadi, l'arte non o fallida. Ben che si uno e disarmado e sia ben presto, degl'altri zoghi po far asai & anchora questo. |

[10b-e] Per lo modo ch'io ti tegno e t'o preso |

[35r-d] ¶ Te tali teneo forma / prendoque gementem / | |||

[75] To take your dagger I make a cover like this, This cover is very good in armor or without armor. And against any strong man such a cover is good for covering an attack from below as well as from above. And from this play you can enter into a middle bind as shown in the third play of the First Dagger Remedy Master. And if the cover is made in response to an attack from below, the student will put the player into a lower lock also known as “the strong key”, as shown in the sixth play [38] of the Third [Dagger] Remedy Master who plays to the reverse hand attack. |

Now I make this cover, for which reason <read: in order that> I would be able to take away the dagger, |

[15r-c] ¶ Questa coverta in Arme e senz'arme e molto bona. E contra zaschun homo forte, tanto e bona a chovrir di sotto mane quanto di sopra. E questo zogho intra in ligadura mezana, çoe al terzo zogho del primo Re e rimedio di daga. E si la ditta coverta si fa sotto mane, lo scolaro mette lo zugadore in ligadura de sotto, zoe in la chiave forte ch'e sotto lo terzo Re e rimedio ch'e zoga a man riversa a lo Sesto zogho. |

[10b-f] Per tor tua daga tal coverta io faço |

||||

[76] If I can turn this arm of yours, If I can turn this arm I will be certain to put you into the lower lock also known as “the strong key”. I will however be able to do this more safely if I am armored. I could also do something else against you: if I grip your left hand firmly and seize you under your left knee with my right hand, then I will not lack the strength to put you to the ground. |

If I can now twist your shoulder while fighting, |

[15r-d] ¶ Si questo brazzo posso voltare io non mi dubito che in la ligadura de sotto e chiave forte ti faro intrare. Ben che siando armado piu sigura mente se poria fare. Ancho poria altro contra ti fare se io tegno la mane stancha ferma e cum la dritta ti piglio sotto al zinochio la gamba stancha per metter te in terra forza non mi mancha. |

[11a-a] Si io posso aquesto tuo braço voltare |

[35v-d] ¶ Volvere si possum tibi nunc certando lacertum / | |||

[77] Whether you try to strike at me from above or below, With arms crossed I await you without fear. And I don't care whether you come at me from above or below, because however you come at me, you will be bound. You will be locked either in the middle lock or the lower lock. And if I wished to make the plays of the Fourth Dagger Remedy Master, I would cause you great harm with these plays. And I will have no difficulty in taking your dagger. [In the Getty, the Scholar's left foot is forward.] |

[15v-a] ¶ Cum gli brazzi crosadi t'aspetto senza paura. Tra voii di sotto e voii di sopra che non fazzo niente cura, che per ogni modo che tu mi trara tu sarai ligado. O in la ligadura mezana, o in la sottana tu saraii serato. Ben che se volesse far la presa che fa lo quarto Re, rimedio di daga cum gli zogi soii, asai male te faria. E a torti la daga non mi mancharia. |

[11a-b] Si de soto, o de sovra tu te miti a'trare |

|||||

[78] By holding your arm with my two hands, This grip is sufficient to prevent you being able to touch me with your dagger. And from here I can do the play that comes after me. And I could also certainly do other plays to you. I disregard the other plays for now, however, because this one is good for me and very fast. |

Now because I am holding you using both hands during wrestling, |

[15v-b] ¶ Questa presa mi basta che cum tua daga non mi poii tochare. Lo zogho che m'e driedo quello ti voglo fare. E altri zoghi asaii ti poria fare sença alchun dubito. I'lasse gl'altri per che questo m'e bon e ben subito. |

[11a-c] Per lo tuo braço che cum due man e tegno. |

[36r-b] ¶ Nunc quia te manibus teneo luctando gemellis | |||

[79] The student who came before me did not make this play, This is the play referred to by the student who came before me, and I take away this dagger as he indicated. And to disarm him I push his dagger downwards and to the right as written above. And then by making a turn with his dagger I will thrust the point into his chest without fail. [In the Getty and Paris, the Scholar's left foot is forward, and his opponent's right foot is forward.] |

Now I teach taking the dagger away while wrestling the associate; |

[15v-c] ¶ Questo Scolaro che m'e denanzi questo e suo zogho pero che questo tore di daga io lo façço in suo logho, che cargo la sua daga inverso la terra dritto, per torgli la daga como si sopra e scritto. E per la volta che ala daga faro fare. La punta in lo petto gli mettero senza fallare. |

[11a-d] Lo scolar che denanci non fa suo zogho |

[36r-d] ¶ Tollere nunc doceo dagam ludendo sodalj. | |||

[80] So that this student cannot dislocate my arm, I pull it towards me and bend it. And the farther I pull it towards me and bend it, the better, because in this way I make the counter to the Remedy Master of the close play of the dagger. |

[15v-d] ¶ A ço che questo scolaro non mi possa lo Brazzo dislogare io lo tegno curto e linzinado. E si io li tignisse piu linçinado saria anchora meglio, per chi i faço lo contrario del Re e magistro del zogho stretto dela daga. |

[] Illustrations |

Illustrations |

Novati Translation |

Paris Translation |

Morgan Transcription (1400s) |

Getty Transcription (1400s) |

Pisani Dossi Transcription (1409) |

Paris Transcription (1420s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[81] There is no man who knows more about dagger versus dagger than I. I am the Sixth [Dagger Remedy] Master and I tell you that this cover is good either in armor or without armor. And with this cover I can cover attacks from all directions and enter into all of the holds and binds, and strike to finish, as the students who follow me will show. And each of my students will make this cover, and then they will make the plays shown after, as they are qualified to do. |

I do not recognize the man with whom I can’t play. |

[16r-a] ¶ Sesto Magistro che son digo che questa coverta e fina in arme e senç'arme. E cum tal coverta posso covrire in ogni parte. E intrare in tutte ligadure. E far prese e ferire segondo[35] che gli scolari miei vignirano a ferire finire. E questa coverta façça çaschuno mio scolaro. E poii faça li zoghi dredo che si po fare. |

[11a-e] De daga a daga non cognoscho homo che sia |

||||

[82] I made the cover of the Sixth [Dagger Remedy] Master who preceded me. And as soon as I have made this grip I will be able to strike you. And because I position my left hand in this way, I will not fail to take away your dagger. I can also put you in the middle bind, which is the third play [3] of the First Dagger Remedy Master. I could also make other plays against you, without abandoning my dagger. |

[16r-b] ¶ I'o fatta la coverta del Sesto Magistro che m'e denanzi. E subito io fici questa presa per ferir te che far la posso. E a torti la daga non mi mancha per tal modo teglo la mia man stancha. Anchora ti posso metter in ligadura me-[!] mezana ch'e lo terzo zogo del primo Magistro çoe rimedio di daga. Anchora d'altri zogi te poria fare, senza mia daga abandonare. |

||||||

[83] From the cover of my Master which is so perfect, I have made this half turn from the cover of my Sixth Master and I have quickly positioned myself to strike you. And even if you were armored I would care little, for in that case I would thrust this dagger in your face. However, as you can see, in this case I have thrust it into your chest because you are not armored and you do not know the close range game. |

[16r-c] ¶ Meza volta o fatta tegnando la coverta del mio Magistro Sesto. E a ferirte so stado ben presto. E si tu fossi armado, pocha di ti faria cura, che questa daga te meteria in lo volto a misura. Ben che mituda te l'o in lo petto, perche tu non e armado, ne saii zogo stretto. |

[11b-a] Per la coverta del magistro ch'e tanto perfeto |

|||||

[84] With my Master’s cover and with a half turn to the outside, I have not abandoned the cover of my Sixth [Dagger Remedy] Master. I turn my left arm over your right. And moving my right foot at the same time as my left arm I turn myself to the outside. You are now partly bound, and you will have to admit that you will quickly lose your dagger. And I make this play so quickly that I have no concern or fear of your counter. [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown, and both he and his opponent have their right feet forward.] |

[16r-d] ¶ Del Sesto mio Magistro non habandonaii la coverta. Lo mio brazzo stancho voltaii per di sopra lo tuo dritto. E concordando lo pe dritto cum Lo brazo stancho voltandome a parte riversa. Tu e, mezo ligado, e la tua daga tu poi dire io l'o tosto persa. E questo zogo io lo fazo si subito che de contrario non temo, ne non ho dubito. |

[11b-b] Per la coverta del magistro cum meça volta di'fora |

|||||

[85] From the cover my Master made Having made the cover of my Master, I made this grip. And I can strike you whether you are armored or unarmored. And I can also put you into the lower lock of the first scholar of the Fourth Dagger Remedy Master. |

[16v-a] ¶ Fatta la coverta del mio Magistro i'o fatta questa presa. Armado e disarmado ti posso ferire. E anchora ti posso metter in ligadura soprana del primo scolar del quarto Magistro rimedio di daga. |

[11a-f] Per la coverta che a fato el mio magistro |

|||||

[86] Without abandoning the cover of the Sixth [Dagger Remedy] Master, I make this turn [with my dagger]. Your right hand will lose the dagger, and seeing that you have been reversed, my dagger will quickly strike you, and your dagger will be lost to you. Also I can make a turn with my left arm and make you suffer in the lower lock. |

[16v-b] ¶ Non abandonando la coverta del Magistro Sesto, i' fazo questa volta. La mano tua dritta per perder e la daga, e vedi che tu la riversi, la mia subito ti ferira, e la tua daga da ti sera persa. Anchora tal volta cum lo brazo stancho posso fare che in la sotana ligadura ti faro stentare. |

||||||

[87] If you and I are both armored,

[This play has been moved to its proper location as given in Fiore's explanation.] |

[16v-d] ¶ Ben che sia posto dredo lo contrario del Sesto zogo io vo per rasone denançi de luii, per che io son so scolaro e questo zogo si e suo zoe del Magistro Sexto. E vale piu questo zogo in arme che senç'arme, pero fiero costuii in la mano, per che in quello logo non si po ben armare. Per che se uno e disarmato çercheria de ferirlo in lo volto o in lo petto. Overo in logo che pezo gl'avenisse. |

[12a-a] Siando ti armato e mi armato |

|||||

[88] With my left hand I will turn you and expose you I make the counter-remedy of the Sixth King [Dagger Remedy Master], turning your body with an elbow push, and in this way I can strike you, because with this elbow push that I quickly do, I will be able to defend against many close plays. And this is a particularly good counter-remedy to the all of the holds of the close-range game. |

|

[11b-d] Cum la man mancha e ti faro voltar o discovrire |

|||||

[89] With my left hand placed in my defense as shown, |

[11b-c] La man stancha o'metuda a'tal deffesa |

[] Illustrations |

Illustrations |

Novati Translation |

Paris Translation |

Morgan Transcription (1400s) |

Getty Transcription (1400s) |

Pisani Dossi Transcription (1409) |

Paris Transcription (1420s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[90] If I am armored this is a good cover to choose, |

I, well-fortified, make this cover in arms, |

[11b-e] Siando arma questa coverta voio pigliar |

[36v-c] ¶ Hanc ego tecturam facio munitus in armis | ||||

I am the Seventh [Dagger Remedy] Master and I play with arms crossed. And this cover is better made when armored than unarmored. The plays that I can do from this cover are the plays that came before me, especially the middle bind which is the third play of the first Dagger Remedy Master. Also I can turn you by pushing your right elbow with my left hand. And I can strike you quickly in the head or in the shoulder… |

[17r-a] ¶ Lo Setimo Magistro son che zogo cum le brazze incrosade, e piu vale questa coverta in arme che senç'arme. Quello che posso fare cum tal coverta gli miei zogi sono denançi, zoe la ligadura mezana ch'e lo terzo zogo del primo magistro rimedio di daga. Anchora te posso voltar pençando te cum la mia man stancha lo tuo dritto cubito. E poii ferirte in la testa o in le spalle di subito. E questa coverta e piu per ligare che per far altro, ed'e fortissima coverta contra daga. |

||||||

[91] In armour this is a very strong cover |

That movement certainly prevails over the dagger while held in the cross[ing], |

[12a-c] In arme aquesto e un fortissimo incrosar |

|||||

…And this cover is better for binding than any other cover, and is a very strong cover to make against the dagger. [In the Paris, this Scholar wears a crown.] |

|||||||

[92] You will not be able to put me into the middle bind, |

[11b-f] In la ligadura meçana non son per intrare |

| |||||

This is the counter remedy to the plays of the Seventh [Dagger Remedy] Master who came before me. With the push that I make to his right elbow, let me tell you that this counter-remedy is good against all close range plays of the dagger, the poleaxe, and the sword, whether in armor or unarmored. And once I have pushed his elbow I should quickly strike him in the shoulder. [In the Getty, the Master's right foot is forward.] |

[17r-b] ¶ Questo e lo contrario del Setimo Magistro che m'e denançi. Per la penta ch'io fazo al so destro cubito. Anchora digo che questo contrario si'e bon a ogni zogo stretto di daga, e d'azza, e de Spada in arme e senç'arme. E fatta la penta al cubito, lo ferir in le spalle vol esser subito. |

|

[] Illustrations |

Illustrations |

Novati Translation |

Paris Translation |

Morgan Transcription (1400s) |

Getty Transcription (1400s) |

Pisani Dossi Transcription (1409) |

Paris Transcription (1420s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[93] I am the Eighth [Dagger Remedy] Master and I cross with my dagger. And this cover is good both armored or unarmored. And some of my plays are shown before me, and some are shown after me… |

In this way, I carry my dagger while fighting during the cross[ing]. Any defense |

[17r-c] ¶ L'otavo Magistro son, e incroso cum mia daga. E questo zogo e bon in arme e senç'arme. E li miei zogi sono posti alchuni denanzi alchuni di driedo. Lo zogo chi m'e denanzi zoe lo quarto zogo çoe chi fere lo zugadore in la man cum la punta di sua daga per lo simile poria ferir costuii di sotta mano, come ello lo fere di sopra. Anchora poria piglar la sua mano in la zuntura cum la mia man stancha, e cum la dritta lo poria ben ferire, segondo che trovarete dredo di mi lo nono scolaro del nono Magistro, che fere lo zugadore nel petto. Anchora poria fare Lo ultimo zogo ch'e dredo abandonando la mia daga. |

[37r-a] ¶ Hac cruce porto meam dagam luctando. nec obstat | ||||

[94] …In the play that is shown before me, three plays back [72], the Zugadore was struck in his hand with the point of his opponent's dagger. Similarly in this play I could strike downwards to his hand just as in the earlier play I struck upwards to his hand. Also, I could seize his hand at the wrist with my left hand, and then strike him hard with my right hand, just as you will find demonstrated by the ninth student [108] of the Ninth [Dagger Remedy] Master, who strikes the Zugadore in the chest. Also, I could do the last play that follows after [109] where I drop my own dagger and take his. |

|||||||

[95] I am the counter-remedy to the Eighth [Dagger Remedy] Master that preceded me, and to all of his students… [This counter was moved before [97] and [98] because it is unclear how they relate to the Eight Master.] |

[17r-d] ¶ Io son lu contrario del otavo zogo che m'e dinanzi e di tutti soii scolari. E se io alungo la man mia mancha al suo cubito, penzerolo per força, a modo che lo poro ferire ala traversa. Anchora in quello voltare che gli faro, poria butargli lo brazo al collo e ferirlo per asaii modi che si po fare. |

||||||

[96] After this turn that I make you do …If I extend my left hand to his elbow, I can push it so strongly that I can strike him obliquely. Also, as I make him turn I can throw my arm around his neck and hurt him in a variety of possible ways. |

[12a-b] Per la volta che presta t'o fata far |

||||||

[97] This is a guard that is a strong cover in armor or unarmored. It is a good cover because from it you can quickly put your opponent into a lower lock or “strong key.” This is what is depicted by the sixth play [54] of the Third [Dagger Remedy] Master who defends against the reverse hand strike and who uses his left arm to bind the Zugadore’s right arm. |

[17v-a] ¶ Questa si e una guardia e si'e zogo forte in arme e senç'arme. & e bona per che la e subita de mettere uno in ligadura de sotto e chiave forte ch'e depenta lo Sexto zogo del terço Magistro che zoga a man riversa che tene lo zugadore ligado cum lo suo brazo stancho lo suo dritto. |

||||||

[98] This cover that I make like this with arms crossed is good in armor or unarmored. And my play puts the Zugadore into the lower lock, which is also called the “strong key,” which the scholar who preceded me told you about, namely the sixth play [54] of the Third Master who defends with his right hand against the reverse hand strike. And this play is made similarly to the play that immediately preceded me, but is begun in a slightly different way. And our counter–remedy again is the elbow push. [The Master in the right image is missing both garter and crown.] |

[17v-b] ¶ Questa coverta che io fazzo a questo modo cum li brazzi incrosadi, si'e bona in arme e senç'arme. El mio zogo si'e di metter questo zugadore in la ligadura di sotto, zoe quella ch'e chiamada chiave forte, in quella che dise lo scolaro che m'e denanzi, zoe in lo Sesto zogo del terço Re che zoga cum la mane dritta a man riversa. E questo zogo si fa simile mente che se fa questo primo che m'e denançi, ben che'l sia per altro modo fatto. E'llo nostro contrario si'e a pençere ve[!] lo cubito. |

[] Illustrations |

Illustrations |

Novati Translation |

Paris Translation |

Morgan Transcription (1400s) |

Getty Transcription (1400s) |

Pisani Dossi Transcription (1409) |

Paris Transcription (1420s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[100] From this grip that I have I can do many plays. I am the Ninth King [and Dagger Remedy Master] and I no longer have a dagger. And this grip that I make from the low attack is similar to the grip made by the Fourth King [and Dagger Remedy Master], only this one is made against the low attack instead of the high attack, and my plays are not the same as his. This grip is good whether in armor or unarmored, and from it you can make many good strong plays, as shown below. Whether in armor or unarmored there is no doubt of their effectiveness. |

[17v-c] ¶ Lo nono Re son, e piu non e di daga, e tal presa che io fazo de sotto, tale presa fa lo Quarto Re di sapramane ch'io faço di sotta. Ma gli miei zogi non si fano cum gli soi nigotta. Questa presa vale in arme e senza che io posso fare zogi assai e forti. E maxima mente quelli che mi fano seguito. In arme e senza di loro non è dubito. |

[12a-d] Per questa presa'che'i'o asaii zoghi posso far |

|||||

[101] If I rotate the dagger close to your elbow, I have followed on from the presa of the Ninth [Dagger Remedy] Master. Taking my right hand from the grip, I seize your dagger as shown and I rotate it upwards close to your elbow. And I will then thrust the point into your face for certain, or I will deal with you as the next student will demonstrate. |

[17v-d] ¶ Lo mio Magistro Nono cum la presa ch'ello ha fatta quella ho seguita Lassando la mia mano dritta dela presa, Piglai la tua daga commo io fazo per apresso lo tuo cubito gli daro volta in erto. La punta ti metero in lo volto per certo. Segondo che lo scolar fa chi m'e dredo. In quello modo ti faro come i'credo. |

[12a-e] Si io volto la daga per apresso tuo cubito |

|||||

[102] The first student of this Master I complete the play of the student who came before me, and from his grip this is how he should finish his play. Other students will make different plays from his grip. Watch those who follow, and you will see their techniques. |

The student will perhaps be able to make this play of that master [of yours], [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a Master's crown.] |

[18r-a] ¶ Questo zogo che fa lo scolar che m'e denanzi, io fazzo suo complimento, per che dela sua presa qui si finisse lo zogo suo. Ben che gl'altri soii scolari farano de tal presa altri zogi. Guardate dredo e vederete gli loro modi. |

[12b-c] De questo mio magistro lo primo suo scolar |

||||

[103] I can dislocate your arm like this, My Master's grip has already been demonstrated. Here my right hand leaves his grip. And if I grip you under your elbow, I can dislocate your arm. And also from this grip I can put you into a bind, namely the “strong key” [lower bind], which is one the third King and [Dagger Remedy] Master showed in his plays In his sixth play [38] he shows you how this one is done. [In the Getty, the Scholar's right foot is forward.] |

I can truly dislocate your shoulder in this same way; [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[18r-b] ¶ La presa del mio Magistro quella o fatta vista. E la mia man dritta lassai dela sua presa. E si t'o preso sotto lo tuo dritto cubito, Per dislogarte lo brazzo. E anchora cum tal presa ti posso metter in ligadura zoe in chiave forte. Che lo terço Re e magistro reze soi zogi. In lo Sesto zogho sono gli soi modi. |

[38r-c] ¶ Denodare modo simili tibi nempe lacertum | ||||

[104] If I can give your arm a half turn, I have arrived at this position from the grip of my Master [Ninth Dagger Remedy Master], and I do not remain in this grip but move into the lower bind, also known as the “strong key.” This I can do without difficulty, and I can then easily take your dagger. [In the Getty, the Scholar's right foot is forward.] |

I prepare to take away your life using the [In the Paris, the Scholar wears a crown.] |

[18r-c] ¶ Per la presa del mio magistro io son venudo in questa. E di questa presa non faro resta che te mettero in ligadura sottana çoe in chiave forte. Che a mi e pocha di briga. Ben che la tua daga ben possa avere senza fadiga. |

[12b-a] Si a tuo braço posso dare meça volta |

[38r-a] ¶ Inferiore tibi nexura tollere vitam | |||

[105] Without releasing my grip I enter underneath your arm, I have not abandoned the grip of my Master [the Ninth Dagger Remedy Master], but I have quickly entered under his right arm, to dislocate it with this grip. I can do this whether he is wearing armor or not, and once I have him held from behind and in my power, I will show him no mercy as I hurt him. |

Behold! I crossed beneath the shoulder during play, |

[18r-d] ¶ La presa del mio magistro non o abandonada. Anche subito intrai per sotto lo suo brazzo dritto per dislogargli quello cum tal presa. O armado o desarmado questo gli faria. E quando io lo tegniro dredo de lu'in mia bailia per mal fare no gli rendero cortesia. |

[12a-f] Non lassando la presa pasaii per soto tuo braço |

[37v-c] ¶ En ego transivj subter ludendo lacertum. | |||

[106] Although this play is not often employed, I did not abandon the grip of my Master [the Ninth Dagger Remedy Master] and the Zugadore saw that he could not break my grip on his arm. And as he pressed downwards towards the ground with his dagger, I quickly reached through his legs from behind and grabbed his right hand with my left hand. And once I had a good grip on his hand, I passed behind him. And as you can see in the picture, he cannot dismount his own arm without falling. And I can now also do the play that follows me. If I let go of the dagger with my right hand, and I grab his foot I will send him crashing to the ground, and I cannot fail to take his dagger. |

It is granted that this play could scarcely be learned by this art, |

[18v-a] ¶ La presa del mie magistro non abandonai in fin che questo zugador vidi vidi[42] che non lassava la presa. E luii se inchina cum la daga in verso terra E io subito piglai la sua mano cum la mia mancha per enfra le soi gambe. E quando la sua mano hebbe ben afferada, dredo de lu passai. Comomo possete vedere ch'ello non si po discavalcare sença cadere. E questo zogho che m'e dredo posso fare. La man dritta dela daga lassa, e per lo pe lo vegno a piglare, per farlo in terra del tutto andare, e a torgli la daga no mi po manchare. |

[12b-d] Ben che aquesto zogho non sia tropo usado |

[43r-a] ¶ Iste licet ludus vix sit hac cognitus arte, | |||

[107] The student who preceded me performed the first part of this play, and I make the finish by driving him into the ground, as has already been explained. Although this play is not commonly performed in the art, I wish to show you that I have a complete knowledge of it. |

[18v-b] ¶ Questo scolaro che m'e denanzi, a fatto lo principio. & io fazo del so zogho la fine, de mandarlo in terra como ello ha ben ditto. Per che questo zogho non habia corso in l'arte, volemo mostrare che in tutta liei habiamo parte. |

||||||

[108] I made the cover of my Master [the Ninth Dagger Remedy Master] and then quickly I gripped him in this way with my left hand. And then I drew my dagger and thrust it into his chest. And if I do not have time to draw my dagger, I will make the play that follows me. |

[18v-c] ¶ Del mio magistro fese sua coverta e subito cum mia mano stancha, presi la sua a questo modo. E cum la mia dagha gli fazo una punta in lo suo petto. E si la daga mia no fosse sufficiente, Faria questo zogo che a mi e seguente. |

||||||

[109] With this play I complete the play of the student who preceded me, who left his [sheathed] dagger where it was and instead decided to take your live dagger. I have already explained how this play is performed. |

[18v-d] ¶ Questo zogo complisco de questo scolaro che m'e denanzi che lassa la sua daga cativa e vole la tua bona. Questo che io ti fazo, a luii tu la rasona. |

||||||

| [No Image] | [110] The Counter-remedy to this Ninth [Dagger Remedy] Master's play is as follows: when the Zugadore with his left hand has seized your right hand that has the dagger, then you should quickly seize your dagger near the point and strongly draw or pull it back towards you so that he has to let go of it, or alternately press the dagger point into his elbow to make him think twice. |

[18v-f] ¶ Lo contrario dello Nono Magistro si'e questo, che quando lo zugadore a presa la man dritta cum la daga cum la sua man stancha, che subito lo zugadore, pigli la sua daga a presso la punta e tragala overo tiri in verso di si si forte che'la convegna lassare, overo gli daga penta al chubito per farlo svariare. |

Illustrations |

Novati Translation |

Paris Translation |

Morgan Transcription (1400s) |

Getty Transcription (1400s) |

Pisani Dossi Transcription (1409) |

Paris Transcription (1420s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

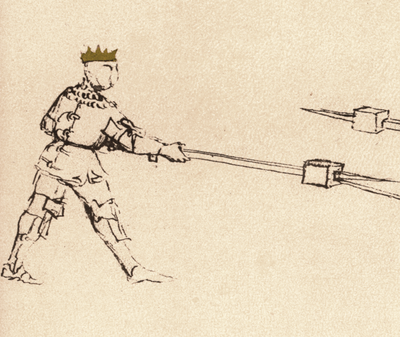

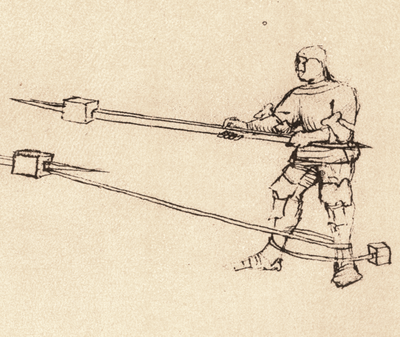

[1] The Stance of the Shortened Serpent I am the Shortened Stance, the Serpent, with axe in hand; I am the Short Serpent Guard and I consider myself better than the other guards. And whoever receives one of my thrusts will bear the scars.[43] This guard delivers a powerful thrust that can penetrate cuirasses and breastplates. Fight with me[44] if you want to see the proof. |

Behold, with grasping hands I am called the Short Spear Position |

· Posta breve serpentina ·

[35v-a] ¶ Io son posta breve la serpentina che megliore dele altre me tegno. A chi daro mia punta ben gli parera lo segno. Questa punta si'e forte per passare coraze e panceroni, deffende ti che voglio far la prova. |

[27a-a] Posta breve son la serpentina cum la aça in mano |

[8v-c] ¶ Manibus astringens Jaculum / brevis: en vocor inter | |||

[2] The Stance of the True Cross I am the strong stance called the Cross: I am named the Guard of the True Cross, since I defend myself by crossing weapons, and the entire art of fencing and armed combat is based on defending yourself with the covers of crossed weapons. Strike as you wish, I’ll be waiting for you. And just as the student of the First Remedy Master of the sword in armor does, so I can do with a step and a thrust with my poleaxe. |

Behold, I am a Position of strength, and I am called the Cross. No blow is |

· Posta de vera crose ·

[35v-b] ¶ Io son posta di vera crose, pero che cum crose me defendo. E tutta l'arte di scarmir[!] e de armizare se defende cum coverte dello armizare incrosare. Tra pur, che ben t'aspetto, che zo che fa lo scolar primo dello magistro remedio della spada in arme cum lu modo e cum lo passar tale punta cum la azza mia ti posso far. |

[27a-b] Io son posta forte chiamada la crose |

| |||

[3] [The Stance of the Queen] I am the Stance of the Queen, of pure loyalty: I am the Guard of the Lady, and I go against the Boar’s Tusk guard. If he waits for me, I will make a powerful strike at him, in which I move my left foot off the line, and then I pass forwards, striking downwards at his head. And if he blocks strongly under my poleaxe with his, then even if I can’t strike him in his head I will not fail to strike his arms or hands. |

Behold, I am pure of faith standing in the Position of the Woman. |

[35v-c] ¶ Posta de donna son contra dente zengiaro, Si ello mi aspetta uno grande colpo gli voglio fare, zoe che passaro lo pe stancho acressando fora de strada, e intraro in lo fendente per la testa. E si ello vene cum forza sotto la mia azza cum la sua, se non gli posso ferire la testa, ello no me mancha a ferirlo o in li[47] brazzi o en le man. |

[27a-c] Posta de dona son de lielta pura |

| |||

[4] [The Wild Boar's Tusk/Middle Iron Gate] I am the Boar's Tusk, full of daring: If my Middle Iron Gate is opposed by the Guard of the Lady, we both know each other’s game, for we have faced each other many, many times in battle with swords and with poleaxes. And let me tell you, what she claims she can do to me, I can do better against her. Also let me tell you that if I had a sword instead of a poleaxe, then I would thrust it into my opponent’s face as follows: when I am waiting in the Middle Iron Gate with my two-handed sword, if he attacked me with his poleaxe with a powerful downward strike from the Guard of the Lady, then I quickly advance forward striking him strongly under his poleaxe as I step off the line, and then I quickly grasp my sword in the middle with my left hand and make the thrust into his face. While there is little difference between we two guards, I am the more deceptive. |

I am the strong Boar’s Tooth and, horribly daring, [The Paris image resembles the Pisani Dossi.] |

[35v-d] ¶ Si posta di donna a mi porta di ferro mezana e contraria, io cognosco lo suo zogo e'llo mio. E piu e piu volte semo stade ale batagle e cum spada e cum azza. E si digo che quello ch'ella dise de poder fare, piu lo posso far a lei ch'ella lo po far a mi. Anchora digo che se io avesse spada e non Aza che una punta gli metteria in la fazza, zoe, che in lo trar che posta di donna fa cum lo fendente, e io son in porta de ferro mezana cum la spada a doii mane,[49] che subito in lo suo venire, io acresco e passo fora de strada, sotto la sua azza per forza io entro, E subito cum la mia man stancha piglio mia spada al mezo e'la punta gli metto in volto. Si che tra noii altro che de malicia e pocha conparacione. |

[27a-d] Dent de zenchiar son pieno de ardiment |

| |||

[5] [The Stance of the Long Tail] I am the Long Tail, used against the Window Guard, and I can strike at any time. With my downward strikes I can beat every poleaxe or sword to the ground, setting me up nicely for close play. As you see the plays that follow, please consider each one in sequence. |