|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Federico Ghisliero"

(→Temp) |

(→Temp) |

||

| Line 1,906: | Line 1,906: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>Similarly, when the enemy is in motion, we shall attack him by making a sortie in the fourth circumference, because while he is in motion he will not be able to respond with a wounding attack.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/110|3|lbl=96.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/110|3|lbl=96.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>A part of a good, well-armed soldiery is chosen to undertake the sortie and is secretly taken to the ''strada coperta''. The enemy is suddenly attacked, and then in order that the said soldiery may be secure in its retreat, the walls are armed and use the ''archibuseria'' to defend the soldiery.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/110|4|lbl=96.4}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/110|4|lbl=96.4}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>In the same way, we shall choose the best of the attacks and suddenly wound the enemy; for he, having seen us so far from his body, does not expect such an attack. But in order to be able to retreat in safety, we shall attack him with a ''riverso traversale''<ref>''Riverso traversale'' means a transverse or diagonal blow during retreat. “It’s equivalent to a ''riversa squalembrato'' or ''falso manco'', depending on whether ascending or descending.” [note from Henry Fox]</ref> on the retreat, which we shall make on the way to the ''strada coperta''.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/110|5|lbl=96.5}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/110|5|lbl=96.5}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>But the offense, which cannot be carried out against fortresses by day is easily carried out by night by gaining the bulwark [or battlements]. Consequently one arrives at the trench, and because the true offense is that which is carried out when one is sure of not being offended, one must pull the ropes and take the trenches. By this means and by covering oneself, one approaches the trench.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/110|6|lbl=96.6|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/111|1|lbl=97.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/110|6|lbl=96.6|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/111|1|lbl=97.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,927: | Line 1,927: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>So we, while we are offending our opponent, will always make with our dagger a semi-circle in motion, which will defend our body.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/111|2|lbl=97.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/111|2|lbl=97.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>The trench will dominate the corner of bulwark inside and must be attacked so that it will create a trap that the enemy, discovering the will of his opponent, does not have time to [discover] and defend himself.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/111|3|lbl=97.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/111|3|lbl=97.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| class="noline" | | | class="noline" | | ||

| − | | class="noline" | | + | | class="noline" | <p>So if our enemy tries to dominate us with the sword or the dagger (because our hands, which are our bulwarks, are mobile) we will not allow it. On the contrary, we will continuously dominate our opponent’s sword and dagger so that our body will not be wounded.</p> |

| class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/111|4|lbl=97.4}} | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/111|4|lbl=97.4}} | ||

Revision as of 00:39, 22 March 2024

| Federico Ghisliero | |

|---|---|

| Died | 1619 Turin, Italy |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) | Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (1587) |

Federico Ghisliero was a Bolognese soldier and fencer. Little is know about his early life, but he studied fencing under the famous Silvio Piccolomini.

In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii, dedicated to Ranuccio Farnese, who was 18 years old at the time of publication and would become Duke of Parma, Piacenza, and Castro. Ghisliero's manual is notable for his use of geometry in relation to fencing, and the incredibly detailed illustrations, using concentric circles centered on where the fencer has placed most of their weight (often, but not always, the back foot), and illustrating multiple versions of each figure in a plate, showing the progression of the movements he describes.

Treatise

Introduction

Antonio Pio Bonello

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Rules of many knightly[1] armies, Collected by Captain Frederico Ghisliero, in service to the Most Illustrious Lord Antonio Pio Bonello. In Parma. [published] by Erasmo Viotto. 1587. |

[+ⅰ] REGOLE DI MOLTI CAVAGLIERESCHI ESSERCITII. Raccolte dal Capitano Federico Ghisliero, ad instruttione dell' Illustrissimo Signor Antonino Pio Bonello. In Parma. Appresso Erasmo Viotto. 1587. | |

To the Most Illustrious Lord Antonio Pio Bonello, son of the most excellent Lord Girolamo Bonello, Marquis of Cassano. For two reasons, my Most Illustrious Sir, it has pleased me to direct to Your Most Illustriousness the present book of mine, which I have written here and now, and with good reason, on the use of arms. The first, so that with this new birth of mine I may wish you well, having intercepted with infinite pleasure the marriage which followed between you and the Most Illustrious Lady Octavia Bagliona: with which your Most Illustrious House may hope for a most happy succession: just as I desire that my birth, under the protection of your name, may live for a long time in safety. The other, so that by reading in this book, Your Illustriousness will be able to recognise in it those precepts, which perhaps up to now have been shown to you by a good Master in the handling of arms, your own virtue, which you have wished to adorn with many others in this most tender anchorage of yours. Therefore, let this effort of mine not be discouraging to you: for if it could be weak in itself, nevertheless, by reading it, Your Illustriousness will understand that you will be able to see much more than your own strength and merit would allow. I would like to thank Your Illustriousness for this letter. I kiss your hands. |

[+ⅱ] ALL'ILLVSTRISSIMO SIGNOR ANTONINO PIO BONELLO, Figliuolo dell'Eccellentissimo Signor Girolamo Bonello, Marchese di Cassano. PEr due rispetti; Illustrissimo Signor mio; m'è piaciunto d'indrizzare à Vostra Signoria Illustrissima il presente mio libro, che quasi pur hora, et con buona occasione hò scritto sopra l'essercitio dell' armi. L'uno, accioche con questo mio nuouo parto io augurassi bene à lei, hauendo intesso con infinito mio piacere il martimonio seguito tra lei, & l'Illustrissima Signora Ottuioa Bagliona: col quale l'Illustrissima casa sua potrà sperar felicissima suc- [+ⅱv.1] cessione: si come desidero io, che'l medesimo mio parto sotto la protettione del nome suo viva lungamente sicuro. L'altro, accioche leggendo Vostra Signoria Illustrissima in questo libro quei precetti, che forse fin'hora le saranno venuti mostrati da buono Maestro nel maneggiar l'armi, possa riconoscere in essi la propria virtù, della quale con molte altre hà voluto in questa sua anchor tenerissima età essere ornata. Non sia dunque discara à lei questa mia fatica: che se bene potesse essere per se stessa debole, nondimeno col leggerla Vostra Signoria Illustrissima, ella prenderà senza dubbio tanto spirito, che sperarà du poter vivere assai più, che'l proprio vigore, & merito non le permetterebbono. Con che raccommandandomi in buona gratia di Vostra Signoria Illustrissima le bacio le mani. | |

From Parma on April 22. 1587. Affectionate Servant Of Your Illustriousness, Federico Ghisliero. |

[+ⅱv.2] Di Parma gli 22. d'Aprile. 1587. Di Vostra Signoria Illustrissima affettionatissimo Servitore Federico Ghisliero. |

Ranuccio Farnese

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Rules of many knightly[1] armies, Collected by Captain Frederico Ghisliero, in service to the Most Serene Lord Ranuccio Farnese, Prince of Parma, & Piacenza, etc. In Parma. [published] by Erasmo Viotto. 1587. |

[+ⅰ] REGOLE DI MOLTI CAVAGLIERESCHI ESSERCITII. Raccolte dal Capitano Federico Ghisliero, per servitio del Sererenissimo Signore Ranuccio Farnese, Principe di Parma, & Piacenza, etc. In Parma. Appresso Erasmo Viotto. 1587. | |

To the Most Serene Lord Ranuccio Farnese Prince of Parma, Piacenza, etc. Most Gacious[2] and Serene Lord; when Your Highness reminded me of my service to you in the play of arms, that having worked with you only a little on one occasion; that I owed it to you to gather, almost in compendium, all about Theory and Practice. That I by showing in words, and by working with you struggled to obey you and to explain them. And I did that, not to believe that I will be perfectly aware of the profession of the use of arms (which is not really my profession, but is instead that of the military),[3] but by this means to show my gratitude to you. Because while I am deficient in many ways, if I may venture to be very brave, and rejoice very much, I have been noticed by the most illustrious Lord Silvio Piccolomini, for whom, and I hope always to show, that I owe the greatest gratitude to His Highness. How could I ever repay the receipt of this notice from? Even if I did, would I have put enough effort into the following work to warrant further regard from you? |

[+ⅱ] AL SERENISSIMO SIGNORE RANUCCIO FARNESE PRINCIPE DI PARMA, ET PIACENZA. &c. LA gratia, Serenissimo Signoro; che Vostra Altezza s’e degnata a di farmi col servir si di me nell’occasione del giocar d’armi, m’ha ricordato, che ‘essermi adoperato solo con la persona nella medesima occasione sia stato poco; & che percio mio debito fosse di fare una raccolta, quasi in compendio, di tutto quello, cosi circa la Theorica, come circa la Prattica, ch’io col mostrare in parole, & con l‘operare con la persona, mi sono affaticato volontieri, per ubbidire a lei, d’esplicarle. Et questo ho fatto non per credermi o di saper perfettamente la professione [+ⅱv.1] dell’ adoperar l’armi (che la profession mia veramente non e questa; ma e quella di militia) o di poter con questo mezzo ricompensar la medesima gratia: perche nell’uno so certo di mancare in molte cose, se ben posso tenermi a molta ventura, & rallegrarmi meco stesso d’esser stato fattura dell'Illustrißimo Signore Silvio Piccolomini, alla cortesissima humanita del quale, in cio sempre mostrata verso me, ne rendo quelle maggiori gratie, che da me si debbono: nell’altro, come potrei io mai ricompensare a Vostra Altezza il ricevuto, s’a farlo non mi bastrebbono mille fatiche, ch’io ne spendessi di piu? | |

I wish to provide you a sign of my loving inclination to you and that I will forever serve you in my life through this work. |

[+ⅱv.2] Ma questo hò voluto fare, accioch'ella habbia segno da me della mia affettuosissima inclinatione, ch'io ho di continuamente servirla, & d'adoperarmi per lei con l'opera, come sempre farei con la vita. | |

I add to this an ardent desire, which I too have together with your other faithful servants. Who is in this first flower of his age to want to provide to you the opportunity, which likewise from me can give you occasion, with this way shown by me, to become accustomed to the exercise: to your profit, and in a way that always protects your life and reassures those who worry about you.[4] |

[+ⅱv.3] Aggiungo a questo un'ardentissimo desiderio, ch'anch'io ho insieme con gli altri suoi fidelissimo servitori. Il qual'è in questo primo fiore dell'et à sua di volerla aiutare in quello, che parimente da me si puo, per sumministrarle, ancho con questa via da me mostrata, occasione, ond'ella possa assuefarsi all'essercitio della persona: il quale quanto pro- [+ⅲ.1] fitto faccia in universale alla piu sicura conservation della vita, lo mostrano coloro, che particolarmente hanno trattato di questo. | |

This can be seen in the old Gymnasium, and other places of the ancient emperors of Rome, (which we read about and know about their clothes) copied across many parts of Rome and the world, so that they and their people would take advantage of such exercise not just of the body but the soul. Such exercise makes it easier to be skilled in peace and war.[5] |

[+ⅲ.2] Lo mostrano tanti Gimnasii, & tanti altri luochi gia da gli antichi Imperatori (come si legge; & a nostri di ancho se ne veggono i vestigi) fabricati & in Roma, & in altre parti del mondo: affine che & essi medesimi, & i popoli loro ne prendessero essercitandosi in diverse maniere quella utilita, che dall'essercitio nasce non solo al corpo, ma ancho all'animo: dal qual commodo si vien poi con maggior facilita ad acquistare attitudine per adoperarsi nelle cose cosi di pace, come di guerra. | |

And while we can make this art[6] profit on a thousand other occasions, if only it delivers the following two benefits at the same time it could be considered worthy, and we can do it very well through practicing this art: firstly vigour and robustness of the soul and body; the other which should not be taken lightly, and is the principle reason for this study to be pursued, is being able to defend against any insult against your person.[7] |

[+ⅲ.3] Et se questo guadagno potiamo far con mill'altre occasioni, si potiamo molto ben farlo con la via di quest'arte della schrima: dalla quale in un tempo medesimo trahemo due frutti: l'uno e quel, ch'io dissi, il vigore, & la robustezza dell'animo, & del corpo. L'altro e o facendosi da scherzo, o da dovero adoperandosi, il sapersi difendere contra l'insulto di chi che sia: che questo e il principal fine di colui, che in questo studio s'essercita. | |

Therefore, Your Highness, in response to your kindness, what is most dear to me, and for your own good, this effort of mine to deliver to you the dearest of desires which can be achieved; the preservation of life, and the recreation of the mind. |

[+ⅲ.4] Accetti dunque Vostra Altezza per benignita sua [+ⅲv.1] questa mia fatica in quel medesimo grado, che si sogliono accettar le piu. care case; che cosa piu cara certo a noi non debbe essere, che quella, dalla quale si possono conseguire, & la conservatione della vita, & la recreatione della mente. | |

And the more willing you are to accept this gift of mine accompanied by very loyal advice (with which you may not always agree) that I do so with the example of the most serene Lord Duke ALESSANDRO, your father, which at the same age as Your Highness had spent time on this honourable pursuit and whose great name is well known. While his quality and greatness of name is not yet known to Flanders, all of Italy and almost all of the world is amazed at its incomparable value. |

[+ⅲv.2] Et tanto piu volontieri ella dovra accetar questo mio dono accompagnato da fidelissimo consiglio (che talhora ancho non si disdice al servitore di ben consigliare il Signor suo) quanto che debbiamo tener per certo, ch'ella sara per far cio con l'essempio del Serenissimo Signor Duca ALESSANDRO suo Padre: il quale senza dubbio nella medesima et a di Vostra Altezza dispensando il tempo in essercitii di questa honoratissima qualita, e finalmente giunto a quella grandezza di nome, & di fatti, della quale hoggi non pure e testimonio tutta la Fiandra; ma ancho tutta l'Italia, & quasi tutto il mondo stupisce dell'incomparabil suo valore. | |

The principles of such greatness in Your Highness will no doubt be reflected in your and everyone hopes to see you walk in his footsteps to be just as great as him. |

[+ⅲv.3] Al quale per gli principii, che tuttavia in Vostra Altezza manifestamente si scuoprono, non ha alcuno, che in fallibilimente non speri di veder lei caminar con le medesime vie di pari. | |

I am grateful to be abundantly committed to the serenity of your person and willing to help you through to this end. I kiss your hands with humble reverence. |

[+ⅲv.4] La qual gratia piaccia a Nostro Signor Dio d'essequire abon- [+ⅳ.1] dantemente nella Serenissima persona sua; & à me di compitamente vederla essequita. Et con humilissima riverenza le bacio le mani. | |

The Palace of Your Most Serene Highness in Parma, 22 April 1587. The most humble and devoted servant Of Your Most Serene Highness, Frederico Ghisliero. |

[+ⅳ.2] Del Palazzo di Vostra Altezza in Parma gli 22 d'Aprile 1587. Di Vostra Altezza Serenissima. Humilissimo & devotissimo Servitore. Federico Ghisliero. |

Theory

Chapter 1

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Rules of Many Knightly Armies Collected by Captain Federico Ghisliero, for the service of the Most Serene Lord RANUCCIO Farnese, Prince of Parma, & Piacenza, etc.[8] |

[1] REGOLE DI MOLTI CAVAGLIERESCHI ESSERCITII. Raccolte dal Capitano Federico Ghisliero, per servitio del Serenissimo Signore Ranuccio Farnese, Principe di Parma, & Piacenza, etc. | |

I have been considering several exercises of arms, which while different, contribute to the subtlety and nobility of the Cavalier;[9] for whom understanding how to use the sword, more than any other instrument, will be important to defend his honour, both in sudden assaults, as well as in close combat, so as to be the one who is victorious, and achieves honour through feats of arms. To avoid confusion, as many have done in writing about this art, we will begin with as the principle of all our exercises, by considering the nature of man when altered by the power of the soul and his passions, and how that hinders his reason. |

ⅠO mi sono preso a trattare di diversi essercitii d'armi, i quali se ben sono tra loro differenti, nondimeno tutti convengono alla sofficienza, & nobilta del Cavagliero: al quale piu d'ogn'altra sorte d'arme sta bene il sapere adoperare la spada, cosi per esser instrumento truovato prompriamente per difender l'honor suo, tanto ne gl'improvisi assalti, quanto nelli steccati da corpo a corpo: & finalmente per esser quella, che ne'fatti d'armi ha per fine la vittoria, & ne riporta honore; noi dunque da essa, come da principio di tutti i nostri essercitii incomniciaremo: & per non incorrere in confusione, come hanno fatto molti, i quali hanno trattato di quest'arte, avertiremo di consti- [2.1] una facultà, la quale si conformi alla natura dell’huomo, quando si truova alterato dalle potèze dell’anima, & sue passioni, che impediscono, che tal’hora l’huomo non possa operate con ragione. | |

The body of a man is composed of four simple elements.[10] The shape of the man’s body does not change the nature of these four elements, but the qualities and virtues of these natural elements change the man. These natures are: |

[2.2] ⅠL corpo dunque dell’huomo è còposto di quattro corpi semplici elemnetali; non che in esso si truovino conqiunti i quattro elemèti nelle proprie forme, & nature loro; ma vi sono in quanto vi concorrono con le proprie loro qualità, nelle quali sono le virtù delle dette nature: però che la natura della terra per esser fredda, & secca, genera nell’huomo vn’humor detto melancolia, ch’è pur fredda, & secca; l’acqua di natura fredda, & humida [bagnato] fà la flemma; l’aere di natura caldo, & humido fà il sangue; & finalmente il fuoco di natura caldo, & secco fà la colera. | |

And if the man, according to the common nature of his species, has a temperate character not given to any extreme, then this is in contrast to brutish animals, whose natures are greatly inclined to extremes according to the common nature of each species and what we understand of their particular passions. So we see that all hares are timid, all lions are bold, all dogs are irascible;[15] but man alone has natures common to all species, being timid, bold, irascible, and much subjected to passions. |

[2.3] Et se bene l’huomo, secondo la natura commune della sua specie, hà il corpo di complessione in maniera temperata, che non declina ad alcuno estremo; contra à quello, che fà la specie de gli animali brutti, i quali havendo le complessioni grandemente inclinate à gli estremi, sono tutti secondo la natura commune à ciascuna delle loro specie naturalmente molto soggetti; come si comprende da certe lo- [3.1] ro particolare passioni. Onde veggiamo che tutti i lepri sono timidi, tutti i leoni audaci, tutti i cani iracondi; ma gli huomini soli veggiamo secondo la natura commune à tutta la specie, effer per lo più ne timidi, ne audaci, ne iracondi, ne molto sottoposti alle passioni. | |

Nothing of those inclinations, which have not a second nature common to all species, have determined the particular nature of each man: because for those which are predominantly in choleric humour are naturally hot-tempered; others because they are abundant in blood, are cheerful and bold in nature; and other because they have melancholic humour in excess make sounds of pain and are timid; and there is almost no one who is in all part equal in all quarters of the humours that it results in the passions in all parts being temperate and equal. We are all inclined to one more than another in accordance with the character which is in each of us. |

[3.2] Nientedimeno quelle inclinationi, ch’effi non hanno secódo la natura cómune à tutte la specie, l’háno [ hanno] secódo la natura particulare di ciascuno huomo, percioche si truovano molti, i quali, perche in essi predomina molto humor colerico, sono naturalméte iracondi; altri, perche abbondano disangue, sono allegri, & audaci per natura; & altri, perche in essi l’humor melancolico supera, sonor dolenti, & timidi: & quasi niuno è nel quale siano cosi misurati gli humori, che ne risulti la cóplessione in tutte le parti téperata, & uguale. Onde avviene, che tutti siamo chi più ad una, chi più ad un’altra passione inclinati, cóforme alla complessione, che in noi signoreggia. | |

This is why, if the man is melancholic, he will be regarded as acting as an earthly element, being quiet, restrained, anxious and boring; it is as you see the earth, still, grave and narrow. |

[3.3] Di quì nasce, che se l’huomo sarà melancolico, si vedranno in lui gli atti, come nati d’elemento terreo, pendenti, ristretti, ansii, & noiosi; si come si vede effer la terra, pendente, grave, & ristretta. | |

The water’s motions,[16] because they’re also falling, if not as bad as the land, are nonetheless limited, and are phlegmatic, which corresponds with the element of water and in the body this quality prevails as timid, simple and humble. The ripples which are almost indulged in the body and cast a pall which brings him low, he turns away his face, and then such calm gives rise to fear. What does that mean? It demonstrates the humanity and the pain. |

[3.4] I moti dell’acqua, perche sono anchor essi cadenti, se bene non tanto, quanto i terrei, sono nondimeno manco ristretti, & fanno la flemma, la quale corrisponde all’elemento dell’acqua: & ne’corpi, ne’ [4.1] quali ella prevale, i moti riescono timidi, semplici, & humili: onde le mebra del corpo restano quasi abbandonate, & delinanti al basso; & per la pallidezza, ch’essa, insonde ne’volti, fà che alla flemma corrisponde la paura, ò il timore; che vogliam dire; & per la bianchezza cerulean dimonstra nbe gli humini il dolore. | |

If there is an increased tendency toward, and attempt to be temperate, and not stretch [the emotions],[17] there is a catch; what about the fire? For the sake of appealing elements, which comply with [the person’s will] is the death of the man’s blood (i.e. temperate, modest and real) to the emotions that correspond clearly to the passions of the soul; i.e. the love from which the beloved, the pleasure, the desire, and the hope is born. |

[4.2] L’aere hà u suoi mnoti tendenti all’alto, ma questo non fuor di modo, per esser temperate, & non dilatati, ne assatto storti; some sono quelli del fuoco; & per esser’essoi elemoento piacceuole sono conformi à [a] que sto i moti del sangue dell’huomo; cioè; temperate, modesti, & reali; a i medesimi moti corrispondono persettamente le passioni dell’animo; cioè; l’amore dal quale nasce il diletto, il piacere, il desiderio, & la speranza. | |

The nature of fire tends toward extreme emotions, as you can see from its flames they reach extreme heights and torture everyone. Similar to this is the emotion of cholera, because they are violent, impetuous and ferocious: and since the emotions are very in like with the two passions, Hate and Anger, they easily appear in the human body, in which this element is predominate. |

[4.3] Il fuoco ultimamente hà di natura i suoi moti tendenti, come si comprède dale sue fiamme, alla estrema altezza, & in eleuarsi tutti si vanno torcendo. Simili a questi sono i moti della colera, percioche sono violenti, impetuosi, and feroci: & essendo â questi moti molto conformi le due passioni, Odio, & Ira, esse perfettamente appariranno in quei corpi dell’huomo, ne’quali predominerà questo elemento.

| |

And because the art can overcome nature we will try to render the timid bold, while the bold man will continue to be bold. Ironically, even if slowly, we will reduce the choleric nature. |

[4.4] Et perche con l’arte si può supercar la natura, cercaremo con quella della scherma render’il timid audace; & l’huomo audace manterremo tale; al- [5.1] l’iracondo sminuiremo la colera, accioche non sia precipitoso. | |

While much fear, by its nature, can corrupt the judgement and impede [that ability of a person] to take advice, and the same can be applied to anger, then it would be easy for the timid to be bold and fear will diminish. The young must be more diligent because if you shy away from reason when increasing your capability with arms, these emotions will be more animated and will pose a danger because failure to manage fear will cause more fear. |

[5.2] Et se bene il timore corrompe in gran parte per sua natura il giudicio, & impedisce il consiglio; & se benne l’istesso essetto fà l’iracondia, nondimeno si sarà facile al timido far l’audace: la qual cosa si farà, sesminuiremo la paura; laquale, quando non è molto grande, adduce seco diligenza: perche se’l timido con la ragione delle cosa si farà capace della facultà dell’armi, esso sarâ più animoso: poiche il mancar la virtii in colui, che teme, è cagione del timore. | |

We will moderate cholera, and even the hot-tempered will be better able to use reason, if we operate with good austerity and he does not leave himself to the transports[18] of his passions. We’re going to show him how well he has to balance everything so that he can come back [from his passions] and help stop them. With a plan this can be achieved slowly and safely. |

[5.3] Parimente all’ iracondo moderaremo la colera, & losaremo più atto ad usar della ragione, se con buoni auertimenti operaremo, che egli non si lasci transportar dale passioni; magli mostraremo, come debba ben bilanciare tutto quello, che può tornarli in aiuto, ò che può dargli impedimento; & che debba porsi ne’pericoli col piè dubbioso, & intrarvi pian piano. | |

I should also like you to know that in imagining those things we have a great deal of hope, and good company, in whose such honourable members footsteps we can walk, to force, through the art of fencing and its practice, bend these emotions to our will and claim victory over them. |

[5.4] Sappisi anchora, che per l’imaginatione di quelle conse, che ci fanno parer l’imprese facili, nasce in noi molta speranza, dalla quale poi siamo fassi arditi per quegli auantaggi, che sono assolutamentre in poter nostro; come dir le forze, & l’arte della scherma; & di quì animosamente operiamo, & co ragio ne otteniamo il nostro fine, ch’è la sola vittoria. |

Chapter 2

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

To make it easier to learn this art, we will begin with Theory and after that, we’re going to deal with the Practice necessary to give respect to this profession. |

[6.1] Per mostrar dunque questa facilità nella presente nostra arte incominciaremo à trattare de’suoi Theoremi: Dopò i quali trattaremo della Prattica, necesarii sima a questa professione. | |

First of all, we must know that these particular circumstances or cognitions are those which are sought after in connection with the human condition; and although they are not intrinsic to the way a human works, they are always necessarily connected to the operation of man, in such a way that if he cannot do any of them, then he may not be able to do the rest of them:

|

[6.2] PRimieramente douiamo sapere, che fette circonstanze, ouer coditioni particolari sono quelle, che si ricercano intorno all'operationi humane: & benche non siano parte intrinseche dell'humane operationi, tuttauia sono sempre necessariamente intorno all'operationi dell'huomo, in modo ch'egli alcuna non ne può fare, che quelle non li siano d'intorno: & la prima e l'operante; la seconda l'opera, ouer'attione operata; la terza è la materia, intorno la quale s'opera ; la quarta è l'instruméto, col quale operiamo; la quinta è in che luoco; la sesta è il modo, secondo il quale operiamo; la settima sarà il fine per il quale si opera. | |

It will therefore be necessary for the knowledge of this science of arms, for which we consider the aforementioned circumstances [to be addressed in order]:

|

[6.3] Sara dunque necessario ad intelligentia di quefta nostra scientia dell'armi, che consideriamo le dette circonstanze, delle quali la prima è l'huomo; la secoda sarà quest'attione di fare alle coltellate; la terza il moto; la quarta la spada per offendere, & il pugnale per difendere; la quinta nelle strade publiche; la seita il modo, secondo, che offendiamo altri, [7.1] & difendiamo noi; lasettima il fine della vittoria. | |

In truth, the body of a human being is in proportion with itself and is well suited to do everything, [as can be proved] by the ancient architects who created almost all things, such as the building of houses, churches, castles, ships, and also all kinds of factories. Yes, as it was done in ancient times, so is it done in modern times. This principle is particularly shown in Book Ⅲ by Vitruvius.[23] |

[7.2] Truouasi il corpo dell’huomo compost di cosi misurata proportione; & qualunque parte consi ben rispondente co’l tutto, che gli antichi Architetti dalla proportione medesima cauarono la composition ne di quasi tutte le cose: come di edificar case, chiese, castella, navi, & in somma ogni sorte di fabrica: si come scriuono tutti gli antichi, & moderni, n che di ciò hanno trattato; tra quali in particolare è Vitruvio nel principio del libro Ⅲ. | |

There is a common, and true, belief by men that their strength[24] will come from their stature, but because some men are bigger in stature, and others are smaller. Each man should understand his stature, Vitruvius says that the foot is the sixth part of the stature of the human. |

[7.3] Questa proportione dell’huomo su giudicata ottima à far questo, ch’io dico, da questi valent’huomini; anchorche nella statura d’esso huomo nó sia certa, & determinate proportione: perche altri huomini sono maggiori di statura, altri minori: che douendo esser l’huomo di conueniente statura, haurebbe da esser di sei piedi humani: però che dice il medesimo Vitruvio, che il piede é la sesta parte della statura dell’huomo. | |

In this regard, Vegetio,[25] in the first book of the Art of War, says that Consul Mario celebrates the recruits; i.e. the new soldiers, at six feet high, had at least five feet, and ten inches, which are the ten parts of the twelve. It follows[26] on then that where the six-foot-high man was of average size; and he, who is more than that, being very tall. So the man, when he passes seven feet, is supernatural and is called a Giant, according to the rule of Marco Varrone, as Aulus Gellius puts it in book Ⅲ of The Attic Nights.[27] |

[7.4] A questo proposito Vegetio nel primo libro dell’arte della Guerra dice, che il console Mario eleggeua i tironi; cioè; i soldati nuoui di sei piedi d’altezza, ò almento di cinque, & deice oncie, che sono le dieci parti delle dodeci. Onde segue che l’huomo alto manco di sei piedi era tenuto di statura mediocre; & colui, ch’è di più di questa esser’altissimo. Onde l’huomo, quando pass ail numero di set- [8.1] te pie piedi, è riputato sopranaturale, è chiamato Gigáte, secondo la regola di Marco Varrone, come riferisce Aulogellio nel Ⅲ libro delle notti Attiche. | |

This conforms with what [Gaius] Suetonius [Tranquillus] says in the Life of the Octavians about the stature of the Emperor, who was mediocre being five feet and three quarters,[28] but this mediocrity is unknown except at the time and did not affect the fact he was a great man with many victories.[29] |

[8.2] Con questo si conforma quello, che Suetonio dice nella vita d’Ottaviano, parlando della statura di quello Imperiatore, la quale era mediocre essendo di cinque piedi, & d’vn dodrante, il quale è noue parti di dodeci: ma questa mediocrità non si conosceua, se non quando egli era vinino à qualche persona, che sosse grande. | |

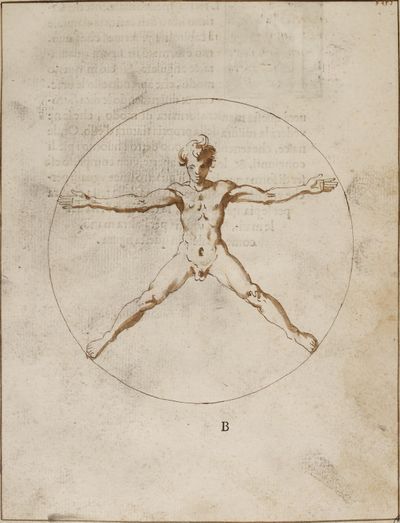

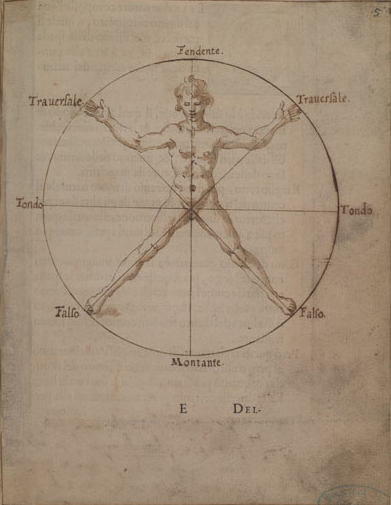

The old philosophers also speculated that the circular figure is the perfect man, and this truth can be understood and measured in this way; let the man lie down flat with his face up and spread his arms, hands and legs as far as they can stretch and draw a circle with the centre being the navel: It’s going to turn out to be round and perfect.[30] This gave Vitruvio himself the title of his third book, and the following figure. |

[8.3] Hanno poi speculando truouato i Filosofi antichi, che la figura circolare, che è più perfetta di tutte l’altre, si truova nell’huomo perfettamente, la qual cosa esser vera si comprende in questo modo; facciasi che l’huomo si distenda ben con la faccia in sù, & distenda parimiente le braccia, & le mani; le gambe, & i piedi quanto più può distendere, & prendasi vn compass, ò la misura d’vn piede del medesimo huomo, & si misura trahendo la misura dall’ombelico, come da centro: che all’hora si vendrà risultare vn circolo tondo, & perfetto. Questo hà auertito il medesimo Vitruvio nel predetto libro terzo, & lo dimostra questa figura, che segue. | |

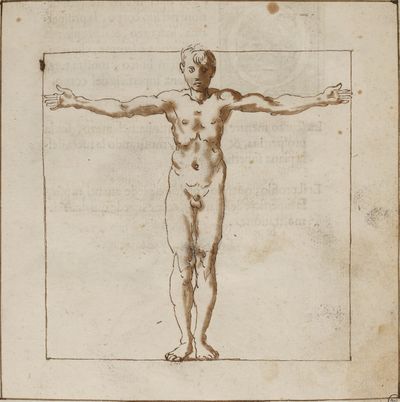

In Chapter 17 of Pliny’s[31] seventh book of natural history he writes,[32] man is a figure of squares and angles and by opening up your arms and by stretching your fingers you will see from this shape that you can measure the size of your height. In the same way by keeping the man’s feet together and open arms are included in the square form of four equal lines, because: the first line passes across the top of the head, the next line passes through where the feet touch the floor, the third line passes through one of the hands and the last line passes through the other hand, as shown in this figure. |

[10] PLinio medesimamente nel settimo libro dell’historia natural à capitol 17. scriue, che l’huomo è format di figurea quadrata, & angulate; & cio in questo modo, che aprendo esso le braccia, & distendendo le dita si trouerà questa maniera formata di modo, che se ne vederà la misura della propria statura d’esso. Onde nasce, che tenendo al modo detto l’huomo i piedi congiunti, & la braccia aperte, vien compreso esser di forma quadrata, di quattro line vguali: perche vna linea li passa per la cima della testa, l’altra per le piante de’piedi, la terza per l’una delle mani, & l’vltima per l’altra mano, come si palesa in questa figura. | |

|

Prospetiva Scortio Profilo

|

This fencer will have three proportions in his body; his front, his scurzo,[33] and his profile. When he stands in balance the front always shows the whole surface of the body. |

[12.1] QVest’ operante hà tre proportioni nel suo corpo, la prospettiua, lo scurzo, & il profile: la prospettiua è sempre, che stando egli in bilico, mostra tutta la piana superficie del corpo. |

The scurzo, while receding in the middle between the perspective[34] and the profile, shows the edge of the flat surface. |

[12.2] Lo scurzo mentre, che si ritruoua nel mezzo, fra la prospettiua, & il profile, mostrando la meta della piana superficie. | |

And the profile, when the right foot shows the surface of the side: as can be seen from the following demonstration.[35] |

[12.3] Et il profile, quando col dritto piede auanti mostra la superficie del fianco: come se vede quì dalla dimonstratione. | |

However, he cannot go from extreme to extreme unless he passes through the middle – the perspective and the profile, being the extremes of the scurzo – the fencer should not bring the body from one side to the other, instead should first bring it into the scurzo. |

[14.1] MA non potendosi passare da vn estremo all’altro, che non si passi per il mezzo; la prospettiua, & il profile essendo estremi dello scurzo non douerà l’operante portar il corpo dall’uno nell’altro, che prima non lo porti nello scurzo. | |

The proportion of the body is most effectively broken into three types of motion;

so as not be confused we can say this is the most important principle, and leave the rest up to the painter.[36] |

[14.2] Le dette proportioni dell corpo si effettuano per gli moti dell’huomo; il quali si diuidono in tre specie; cioè; nel moto di tutto il corpo insieme; nel moto delle braccia; & nel moto delle gambe; i quali essendo i più principali, & che più si confanno al nostro proposito, di quelli diremo, lasciando il rimanente, come quello, che spetta al pittore. | |

The body’s motions are born from its lengths, latitudes, and proportions; and when they are compressed, turned around, and joined together [the fencer] will gain understanding of what is possible; by turning and stretching [the body’s parts] can be extended long them turn and stretched that it is possible for them to the end of their chains. |

[14.3] Nascono dunque i moti del corpo dale lungezze, latitudini, & proportioni de’membri; & da loro oprimersi, & girarsi, & conuernirsi insieme con ragione, & possibiltà; & anchora da loro torcersi, volgersi, & slungarsi, sin’à tànto, che gliè possibile, secondo anchora le incatenature, & chiaui loro. | |

And[37] I will make some rules on these motions by categorising them into eight basic parts, which encompass the total movement of the body:

|

[14.4] Et per dar qualche regola di questi moti; dico, che essi da otto modi, che tiene il corpo di muouersi, nascono: e sono all’insu, all’ingiu, à destra, à sinistral, stendersi per di là, venir per di quà, volgersi dirando, & fermarsi. | |

Basically, for every motion it is necessary for the body to be supported by the foot, without this support, in the way of bodies, it would tend to fall. |

[15.1] In ogni moto, ò auanti, ò adietro, è bisogno, che il corpo sia sostentato dale basi: che altrimentri, per esser la natura de’corpi onderosi di tendere al centro, caderebbe. | |

So it is clear that the motions of the head are such that it is hard for a man to turn around in any part, unless he always has most of his body underneath him; and from this position he can move his weight from side to side and balance[39] so that either leg[40] can bear his weight. |

[15.2] Quindi s’è cauato, che i moti del capo sono tali, che à fatica giamai l’huomo non si volta in alcuna parte, che sempre nó habbia alcuna parte dell’auanzo del corpo posta sotto di se; dalla quale sia sostentato cosi graue peso; oueram ente, che non ponga dall’altra parte opposta, come vna bilancia, alcun membro, che risponda al peso. | |

Because the same can be seen, when someone extends his hand it supports some weight: once the foot is stopped, as the foundation of the balance, the other part of the body is opposed to equalize the weight. |

[15.3] Percioche il medesimo si vede, quádo alcuno distensa la mano sostiene qualche peso: pche fermato il piede, come fondamento della bilancia, tuttua l’altra parte del corpo si contrapone ad aguagliar il peso. | |

While, the man with evenly distant feet is in a state of rest from which the torso and leg extends up then the end of the chin will remain perpendicular to the tip of the foot. |

[15.4] Mentre, che in stato si trououa l’huomo co’ piedi pari; & che fá arco auanti di tutto il corpo, & delle gambe; l’estremitá del mento resterá á perpendicolo della punta de’ piedi. | |

If you put your hand straight out, from the fountain of the body [shoulder],[41] it will always be perpendicular to the feet. |

[15.5] Opprimendosi, ò á mano diritta, ò á mano manca la fontanella, sempre sará á perpendicolo delli detti piedi. | |

Whenever the body hangs over the part of the foot on which it poses, the shoulder will be perpendicular to the instep and the other leg will bear the body weight. |

[15.6] Ogni volta, che il corpo pende da quella parte del piede, che posa, la spalla sará á perpendicolo del collo del piede; & l’altra gamba sará per cotrapeso del corpo. | |

Always, that if he will raise his arm up, all the other parts of the body from that side down to the foot follow that motion of rising: in a manner that the heel of that foot will rise there from the floor, due to the motion of the same arm. |

[15.7] Sempre, che se alzerá in alto vn braccio, tutte l’al- [16.1] tre parti del corpo da quel lato insino al piede seguono quel moto d’alzarsi: di maniera, che il Calcagno anchora di quel piede si leuerá lá dal piano, per il moto del medesimo braccio. | |

A limb is never stretched out to one side, so that the others do not follow; nor does it oppress or constrict itself, so that the others do not follow the line towards the center. |

[16.2] Non si slunga mai un membro da bna parte, che gli altri non lo seguano; ne per incontro s’opprime, ò si serra, che gli altri non seguano quasi, com line verso il centro. | |

The legs operate in three kinds of motion, these are; straight, circular, and transverse. |

[16.3] Le gambe, ouer basi operano tre sorti di moto; cioè; retto, circolare, & traversale. | |

It is correct, that when turning the body back into perspective[42] the legs should be prepared to take the step. |

[16.4] Retto, ogni volta, che ritruouádolsi il corpo in prospettiua le nbasi si approno rettamente: come quando si forma vn passo. | |

While standing still with one foot, one foot can move the same distance as the other foot. |

[16.5] Circolare, ogni volta, che stando fermo il corpo con un piede, descriue con l’altro vna circonferenza. | |

Traverse movement, as long as it is perspective, is made of a motion, of a right or left hand. |

[16.6] Traversale, sempre che si stà in prospettiva; & si fá moto, á mano diritta, overo á mano manca. | |

Importantly, the legs in profile will not be able to open as much as the length of the body. |

[16.7] Le gambe in profile non si potranno aprire tanto, quanto importa la lunghezza del corpo. | |

This line, or quantity described by the opening of the circle of the body, could be divided into infinity: but sufficient for this art we will divide it into four parts, that is,

|

[16.8] Questa linea, overo quantità descritta dall’apertura del compass del corpo potrebbe esser diuisa in infinito: ma à sufficientia di questa nostr’arte, la diuideremo in quattro parti; cioè; in mezzo passo, in un passo, in un passo, e mezzo, & in due passi. | |

By placing [weight] on one leg, the other cannot go much further than the space[43] of one step. From these openings in the circle, there are five ways that the body can stand other than in rest. |

[16.9] Posandosi fvna gamba l’altra non potrà andarui auanti più di quanto importa lo spatio d’un piede. Da queste aperture di compass segue, che in cin- [17.1] que modi il corpo potrà trouarsi in stato, over in quiete. | |

Firstly, when the body is in the balance, so that, even with the feet joined, the body is perpendicular to the diameter of its circumference; and that in so standing is ready to move all parts [of the body]. |

[17.2] Nel primo, quando è in bilico; cioè; co i piedi pari giunti, & che allhora il pendicolare è nel diametro della sua circonferenza; & che in tale stato è atto di mouersi à tutte le parti. | |

Secondly, when the man stops, with all the weight of the body on his foot, the instep becomes the base of the Column – which is perpendicularly aligned with the fountain of the throat; this posture[44] was invented by the ancient Polykleitos.[45] |

[17.3] Nel secondo, quando l’huomo si ferma, con tutto il perso del corpo sopra à vn piede, à guise di base della Colonna, uil qual stà perpendicolarmente sottoposto all fontanella della gola, intendendo il collo del piede, & di questa postura fù l’inventore l’antico Policleto. | |

Thirdly, when man finds himself at rest in one step. |

[17.4] Nel terzo, quando l’huomo si truova in quiete in un passo. | |

Fourthly, while the body is in ‘step and a half’ which then forms an equilateral triangle. |

[17.5] Nel quarto, mentre che il corpo sia in vn passo, & mezzo, che allhora, forma triangolo equilatero. | |

Fifthly, when the body is stopped in two steps with the right front foot raised, which is called forced step. |

[17.6] Nel quinto, quando stà il corpo compassato in due passi andante, che si dice passo sforzato. | |

From these stills, the man forms six circles, two without setting himself in motion, & four after he has described one of the aforesaid quantities in forming a circle. |

[17.7] Da queste quieti forma l’huomo sei circoli, due senza, che egli si metta in moto; & quattro doppo, che sarà descritta vna delle quantità dette; & che formarà un circolo. | |

In the first of the two forms [figure 4] the man, when standing in the balance describes a circle around his feet, the center of which he stands perpendicular. |

[17.8] Il primo de i due forma l’huomo, quando stando in bilico si descriue vn circolo d’intorno à i suoi piedi, il centro del quale è il pendicolare. | |

Secondly it will be, when the man is in said circle, a circle distant from his body is described, how much its length impacts; the center of here will also be the slope: as you can see in this figure. |

[17.9] Il secondo sarà, quando stando l’huomo in detto circolo si descriue vn circolo distante dal suo corpo, [18] quanto immporta la sua lunghezza; il centra del qua le sarà pur il pendiiculare: come si vede in questa figura. | |

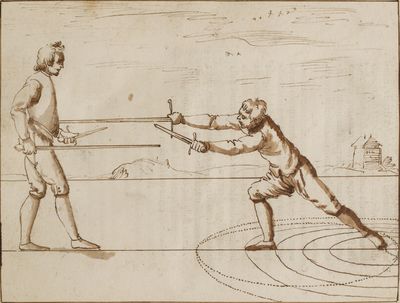

The first of the four forms of the man, when finds himself in the state of in stillness in the already mentioned position of second; and when his stance is not stable where the bodyweight resides, with one leg in the centre of the circle, it allows other leg to describe the edge of the circle, [this is the position] which we use to keep ourselves on guard. |

[19.1] ⅠL primo de’quattro forma l’huomo, quando egli si truova nello stato della seconda quiete già detta; & quando con la base manca stabile, sopra la quale reside il peso del corpo, con quella facendo centro, discriue con l’altra base mobile una circonferenza, della quale si seruiamo per mantenerci in guardia. | |

The second one, when you take one step, then standing in that quiet step, stopping your other foot from moving describe another circle: through this we enter a with traversal[46] motion to exit the points: it also forms the third, whereas, the fourth state is what we will enter when the attack is made, and when he moves into the fifth step, as this figure shows, it is what he will use to fight the enemy. |

[19.2] Ill secondo, quando si truova in un passo, che stante in quella quiete, fermando il piede manco con l’altro mobile, descriue un’altra circonferenza: & in questa entriamo di moto traversale per uscir fuori co’punti: parimente forma la terza, mentre, che si truouerà nel quarto stato, nella quale entriamo quando si fà la ferita: & la quarta, quando egli si trououerà nel quinto stato di passo sforzato: come dimostra questa figura: & con essa si mãteniamo il nemico lotano. |

Chapter 3

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Having said that we have the fencer, or the architect, it is good to continue to describe the matter; since the action of stabbing is self-evident. |

[21.1] Detto c’habbiamo dell’operante, overo artefice, è bene il seguitar di descriuer la materia; poiche l’attione di far alle coltellate è per se manifesta. | |

As the motion, and the matter, around which the man operates in this act of stabbing them, we have to know that movement, according to what Aristotle defends in the ninth text of his fifth book of the Physica,s[47] is a mutation, or transmutation: the types of which some want to be six; i.e. Generation, Corruption,[48] Augmentation,[49] Decreasing,[50] Alteration,[51] and Mutation[52] place-to-place. None other than Aristotle himself in the first section[53] concludes that there are no more than three [types of movement]; i.e. quantity, quality mutation, and location. Of these three types the last type is what we need to know for our art, in which movement is nothing more than transmutation that sometimes causes a body to move from one place to another; and the terms of the movement are two instants. |

[21.2] POiche il moto, e la materia, intorno alla quale si opera dall’huomo in quest’attione di faralle coltellate, debbiamo sapere, che il mouimento, secondo che Aristotile lo diffinisce nel quinto della Fisica, nel nono testo, è una mutatione, overo transmutatione: le specie della quale alcuni vogliono che siano sei; cioè; Generatione, Corrottione, Augumentatione, Diminuitione, Alteratione, & Mutatione di luogo à luogo: nientedimeno l’istesso Aristotile nel prealegato luogo conclude, che tre siano, & non più; cioè; di quantità, di mutation di qualità, & secondo il luogo: delle quali tre specie l’ultima è quella, la quale à noi fà bisogno di sapere per la nostra’arte: il qual mouimento non è altro, che quella transutatione, che alle volte fà mouere uncorpo da un luogo all’altro; & li termini del mouimento sono due instanti. | |

The instant in motion and the instant in time is, the Geometric bridge that is counted in magnitude; that is; which is not [just a] part, but is indisible [to it], and consequently is neither motion nor tempo, but it is the beginning and end of every movement and of each time it is finished; as Aristotle describes in the text of the fifth section of book six of the Physica. |

[21.3] L’instante nel moto, & l’instante nel tempo è, si conme il ponto Giometrico nella magnitudine; cioè; che non ar parte, ma è indiuisibile, & conseguen- [22.1] temente non è ne moto, ne tempo; ma è ben principio, & fine d’orgni mouimento; & d’ogni tempo terminato: come manifesta Aristotile nel sesto della Fisica al testo vigesimo quarto. | |

Movement sits between two stillnesses: and the stillness, true rest, is nothing more than the precondition of movement.[54] |

[22.2] Siede il mouimento fra due quieti: & la quiete, overo riposo, nó è altro, che priuatione del mouimento. | |

And there are three movements, two simple – the straight and the circular – and the third a compound of these two, which serves the compound line. |

[22.3] Et tre sono i movimentri, due semplici, i quali sono il retto, & il circolare: & il terzo composto di questi due, il qual serve all linea composta. | |

The two simple motions are either natural or violent. |

[22.4] I due moti semplici ò sono naturali, ò violenti. | |

Natural movement is when the weight of bodies move from a higher place, to a lower place perpendicularly, and without any violence.[55] Violent movement is what is applied forcefully upwards, here and there; to cause the possible movement. |

[22.5] Il mouimento naturale è quello, che fanno i corpi gravi da un luogo superiroe, ad un’altro inferiore perpendicularmente, & senza violenza alcuna. Mouimento violento è quello, che fanno sforzatamente di giù in sù; di quà, & di là, per causa d’alcuna possanza mouente. | |

In principle, natural motions are weak: and the more they continue the motion, the more they become stronger. |

[22.6] I moti naturali nel principio loro sono deboli: & quáto più vanno continuando il moto, tanto più diuengono di maggior forza. | |

In principle, violent movements are of great effect; the further away they move, the more their strength disappears, and they become weak. |

[22.7] I moti violenti sono di grand’effetto nel principio loro; dal quale quanto più s’allontanono, tanto più si scema la lor forza, & diuengono deboli. | |

And there are four strong local movements: One is called pushing, so we drive away the things we move, those on the other side we push: as we do in pushing the sword forward in a thrust. |

[22.8] Et di quattro forti sono i mouimenti di luogo à luogo: l’uno è spingimento chiamato, per cui scaccian do da noi le cose, che mouiamo, quelle in altra par te spingiamo: come facciamo nello spingere auanti la spada in stoccata. | |

The other [second] drawing is required, so unlike pushing, we make it pull and move towards us; as when we withdraw the sword. |

[23.1] L’altro tiramento è dimandato, per cui al contrario dello spingimento, la cosa à noi tirando, & mouendo, la facciamo à noi accostare: come quando à noi ritiriamo la spada. | |

The third bearing is named, therefore, not by us pushing or by us pulling but by carrying ourselves forward: yes, like he does when with the sword, still in a proportion with the motion of our body, we bring it to the tempo here and there. |

[23.2] Il terzo portamento è nominato, per cui non da noi discacciando, ne à noi discacciando, ne à noi tirando, ma con noi prortando, mouiamo: si come auuiene, quando con la spada ferma in una proportione col moto del cor corpo nostro portiamo quella hora quà, hora là. | |

The fourth revolution, or rotation, can be called that, when we move something in a circle, and that part of it towards us, and that part of it away from us, we turn in such a way that this movement is almost like a withdrawal, and almost like a springimento:[56] as we see in circular attacks. |

[23.3] Il quarto riuolgimento, ò rotamento si piò chiamar quello, per cui in cerchio, mouendo alcuna cosa, & quella parte verso noi accostando, & parte da noi rimouendo, giriamo in modo, che tale mouimento è quasi di ritiramento, & quasi di springimento cóposto: come si vede nelle ferite circolari. | |

And five are the circumferences, which with motion a man forms in order to injure, since in his body he has five centers:

|

[23.4] Et cinque sono le circonferencze, che col moto forma l’huomo per ferire, poiche nel suo corpo hà cinque centri: Et il primo è nel piede manco, col quale stando fermo, & inalzando il braccio diritto con tutto il restante del corpo in moto discriue una cir conferenza, la quale è la maggiore, che egli posta fare: & di questa si forma il taglio. | |

|

[23.5] La seconda circonferenza è formata dall’huomo, quá do compassato fà centro del cinto del corpo: & che co’l resto col braccio in alto descriue una circonferenza, della quale, si seruono molti in combatterealla bariera. | |

|

[24.1] La terza è fatta dall’huomo, mentre che si truova in uno de’cinque stati detti; & mentre che con tutto il corpo fermo facédo centro della spalla, & col braccio solo in moto descriue una circóferenza, & di qlla si seruiamo a fare i mádiritti in stato có le basi. | |

[24.2] La quarta è discritta dall’huomo, quando con tutto il corpo stabile facendo centro del gomito si mette in moto il restante del braccio, chiamato lacerto; & fa circonferenza; della quale si seruiamo per cauar le ferite, quando il nemico uà alla parata. | ||

|

[24.3] La quinta, & ultima si fà dall’huomo, mentre che contutto il corpo stabile facendo centro nella rascetta della mano, con quella sola descriue la minor circonferenza, che egli pssa descriuere; della quale si serviamo in far i groppi di mano. |

Chapter 4

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Where we say stay there to follow our order, that of the offensive, defensive instrument. |

[24.4] Restaci, per seguitar’il nostr’ordine, che dell’instrumento offensiuo, & difensiuo diciamo. | |

The offensive instrument is the sword, & the dagger is the defensive one and although sometimes the sword makes the dagger’s offering by parrying; and the dagger makes the sword’s offering by attacking, this happens by accident. |

[24.5] L’Instrvmento offensiuo è la spada, & iul pugnale è il difensiuo: & se bene alle volte la spada fà l’offitio del pugnale parando; & il pugnale fà l’offitio della spada ferendo, auuiene questo per accidente. | |

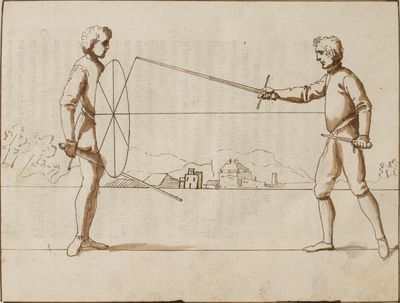

The sword, as an instrument of offense, is divided into the true edge,[62] and false edge, both of which end up in one place: and while a body’s surface contains and is discussed in all three dimensions, we must take it as a line in its operation. |

[24.6] La spada instrumento offensiuo è compartita in filo [25.1] buono, & in filo falso, i quali due finiscono inun póto: Et se bene è corpo contenuto da una superficie; il qual si potrebbe diuidere per tutte tre le dimensioni, nondimeno la debbiamo considerare nell’operation sua come linea. | |

And there are four ways you can hold the sword in your hand:

|

[25.2] Et in qnattro modi si può tener la spada in mano: Nel primo mettendo il detto pollice sopra la sua costa, accioche con questo aiuto si fenda con essa più rettamente: ma in tal mondo le punte non si operano bene; & la mano non fà tutta la sua forza, per esser meza aperta. | |

|

[25.3] Nel secondo si può pigliar in piano con la palma della mano verso terra. Et ciò si fà per haversela da fen tir più leggiera: atteso che la mano col braccio in tale stato opera quasi come appoggio del corpo, il qual fà la lieua al peso della spada: ma in tal modo non si ferisce di taglio; & si giuoca di cambiamento di linee; che è del tutto imperfetto. | |

|

[25.4] Nel terzo modo si prende la spada col pugno serrato per auanzare un dito di lunghesza. Ilche nell’instrumento è vero in effetto: ma ogni volta, che si operi la ferita, l’instrumento col braccio hà da formar linea retta, più che sia possibile; ilche non si può far con questa presa: atteso che cosi sempre si forma angolo ottusa, oltre che i tagli per lo più feriscono di piato. | |

|

[25.5] Nel quarto, & ultimo modo (il quale è il perfetto) [26.1] si piglia la spada col pugno serrato; & col dito indice si trauersa la croce del fornimento: & in tal modo hà tutte le perfettioni la presa. | |

This sword, by its beating, can resemble the wedge, on which the heavier the weight it strikes, the greater the beat. Furthermore, the longer the distance between the weight which strikes and the wedge, the greater the impact. |

[26.2] Questa spada, per la sua percossa, si può assomigliare al cuneo, sopra il quale quanto più sarà graue il peso, che percuote; táto più si farà la percossa maggiore. Et oltra acciò quanto più sarà lunga la distanza fra il peso, che percuote, & il cuneo; tanto più sarà maggior percossa. | |

So the weight of the sword will be heavier more than it will be for itself; and with the power that moves it.[64] |

[26.3] Cosi il peso della spada si potrà aggrauare più di quello che sarà per se stesso; & per la possanza movente. | |

For itself (because whenever the sword comes from a distance, the weight of the sword will become more acute, the more the motion will be greater) given that each serious item, while it moves, takes on more gravity [becomes heavier] when moved than when it is standing still; and the more it is moved from a distance, the greater the advantage. |

[26.4] Per se stesso: perche ogni volta, che la spada verrà da lontananza, il peso d’essa si aggrauerà tanto più, quanto più sarà maggior il moto: atteso che ciascuna cosa grave, mentre si muoue, prende più di grauezza mossa, che stando ferma; & di vantaggio più, quanto più da lontano vien mossa. | |

For the power moves in this way: because being able to form five circles [circumferences] (as we have said) conforming to those will increase the weight: because the first one, which is the largest, will be formed [with the most weight], the others will be made with a smaller and smaller weight since the circles will be smaller. |

[26.5] Per la possanza mouente in tal modo: perche potendo l’huomo formar cinque circonferenze (come habbiamo detto) conforme à quelle si aggrauerà il peso: perche formato che haurà la prima, la quale è la maggiore, si faranno l’altre; & si sminuira sem pre il peso: poiche le circonferenze saranno minori. | |

The defensive instrument, which I consider to be the dagger, has a resistant body; that has the pleasure of defending the body of the man; and can be held in the hand in three ways:

|

[26.6] L’instrumento difensiuo, chi io posi esser’il pugnale, è corpo resistente; il qual’ha’per offitio il difende- [27.1] re il corpo dell’huomo: & in tre modi si può tener in mano: Nel primo si tiene in mano di piatto, col dito grosso in mezo la lama: & diuidendo il corpo in due parti con un semicircolo di moto naturale si difende la parte diritta; & con un’altro semicircolo si difende la parte manca: & perciò và messo in presenza in proportione; affine ch’egli con questi moti faccia le dette difese: il che hà molte imperfettioni: l’una è che quella mano è sottoposta all’offesa: l’altra, se bene muouendo l’ultimo centra solo si discriue una piccola circóferenza, tuttauia la linea del pugnale con quella del braccio forma angolo, per ilquale possono entrar molte linee: oltre, che è sotto posto à molti inconvenienti così di dentro, come difuori; & così disotto, come disopra. | |

|

[27.2] Nel secondo tiensi in tal modo detto pugnale in mano accostandolo più alle parte diritte; & solo si procura di batter con esso in fuori: accioche preuenga la ferita, avanti che quella arrivi al corpo. Il che è falso: perche in vece di coprirlo, lo scuopre; & è mto violeno: oltra che ogni volta, che il pugno dorma un poco d’angolo, il pugnale cosi tenuto non vieterà, che quella spada non entri, & anch’egli è sottoposto all’inganno. | |

|

[27.3] Nel terzo, & ultimo (il quale è il perfetto) si tiene in mano il pugnale in modo, che con esso si poss fen- [28.1] dere bisognando: & di quì co’ moti naturali si difende il corpo coprendolo: il quale così tenuto sempre libero dall’offese, non è sottoposto à gli inganni. | |

In addition to this defending line, it will always dominate the opposing sword; and with its natural motions it will beat it, always helping the lines to their declination: because very little force adds new motion to any weight, which moves first. |

[28.2] Oltre che questa linea difendente dominerà sempre per disuori la spada contraria; & co’ moti naturali batterà, aiutando sempre le linee alle loro declinationi: perche pochissima forza aggiunge nuovo moto ad alcun peso, che prima si moueua. | |

Nevertheless, the last third of the sword will be beaten, since it is the debole[65] in this respect: although when it attacks, it is the strongest or best. This is because, moving with violent motion, the first part of any inanimate thing is easy to move to the other part, which must be understood in this way: since everything is continuously moving, it is very easy to make it move obliquely from those ends to which the mover is attached, since the other end is transported with great speed. |

[28.3] Si batterà nondimeno l’ultimo terzo della spada, per esser’ella parte più debole in quest’effetto: se bene, quando ferisce, è la più forte: perche muovendosi di moto violento, la prima parte di qual si voglia cosa inanimata è facile da muoversi nell’altra parte: ilche si deue intendere in questo modo, che essendo ogni cosa continua mossa, facilissimo sia il farla muouere obliquamente da quelle estremita, alle quali è congiunto il motore: perche l’altra estremità si transporta con grandissima celerità. | |

And just as in the case of things which are thrown or pulled, the motion weakens in the end; so the movement continues to be weaker at the debole and the resistance is less. And on that part [of the blade] things are more easily pushed as there is greater weakness, and therefore less resistance, which is undoubtedly in its end. |

[28.4] Et si come delle cose, che si getano, ò tirano, il moto indebolisce nel fine; così nel fine della cosa continua il moto diuiene più debole; & la resistenza minore: & da quella parte le cose più facilmente si spingono, nella quale è maggior debolezza; & perciò minor risistenza: ilche senza dubbio è nel suo fine. | |

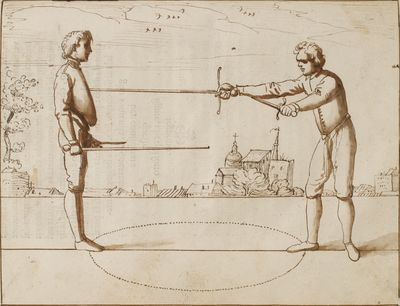

The dagger is a defensive instrument which should form a straight line with the arm; and the same should form a right angle with the surface of the body. And at this point, the view of the man should pass through the forte[66] of the dagger, with the [true] edge over the debole of the enemy’s sword.[67] |

[28.5] Questo pugnale instrumento difensiuo ci debbe for [29.1] mar col braccio una linea retta; & l’istessa hà da formar con la superficie del corpo angolo retto: & stante in questo termine la visuale dell’huomo hà da passar per il forte del pugnale; ferir sopra il debole della spada nemica. | |

Working in this way with the dagger, we will by necessity use our sword to cut through the circle of the enemy’s body. |

[29.2] Operandosi in questo modo col pugnale, necessariamente con la nostrqa spada tuouaremo il diamentro del circolo del corpo nemico. | |

And because the dagger always has to dominate the opponent’s sword, we must ensure that when we raise the sword to our enemy, we raise the dagger so that, always passing through it, we see the sword dominated from the inside [line]. |

[29.3] Et perche sempre deue iul pugnale dominar la spada del contrario, si hà d’auertire, che alzando la spada il nostro nemico, noi alzaremo il pugnale in modo, che sempre passando per esso la nostra visuale, veggiamo dominata la spada per di dentro. | |

The dagger strikes in straight lines; in oblique lines it removes lines; and in angular lines it strikes the edge. And in three ways it strikes the enemy’s line:

|

[29.4] Il pugnale alle linee rette batte; alle oblique toglie il camino; & alle angolari batte l’estrinseco. Et in tre modi si batte la linea nemica: Nell’uno di volontà; nel secondo di necessità; nel terzo di prosontione: nel volontario si batte in dentro, cauandosi la ferita per la maggior lunghezza. | |

If necessary, the sword is not beaten, but only by existing at the attack does he escape with the body, causing the attack to turn the false edge towards the ground. |

[29.5] Al necessitato non si batte; ma solo esistendo alla ferita si fà lo scanso col corpo, cauandosi la ferita convoltar il filo falso verso terra. | |

At the point of contact, the sword is beaten with an outward semicircular motion, when the opposite sword is parried in an oblique line in the presence under the center of the extended body, making sure of the greatest possible length: if the end of the line were to move contrary to the other, the said length would not be reached. |

[29.6] A quel di prosontione si batte con un semicircolo infuori, quando si truova la spada contraria parata in linea obliqua in presenza sotto il centro del corpo distesa, douendosi cauar la maggior lunghezza perferire: & se l’estremo della linea facesse moto con- [30.1] trario all’altro, non si cauarebbe la detta lunghezza. | |

The defending line must be used to bring the line opposite to the center from where it originates: but when it finds itself in the center it must be beaten, and when it is not there it must be helped, so that it may arrive more quickly at its decline through natural motion. |

[30.2] Ne si deue con la linea difendente portar la linea contraria al centro, donde nasce: ma si deue, quando ella si truova in esso, batterla: & quando non vi sia, si deue darle aiuto: accioche più presto di moto naturale arriui alla sua declinatione. |

Chapter 5

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

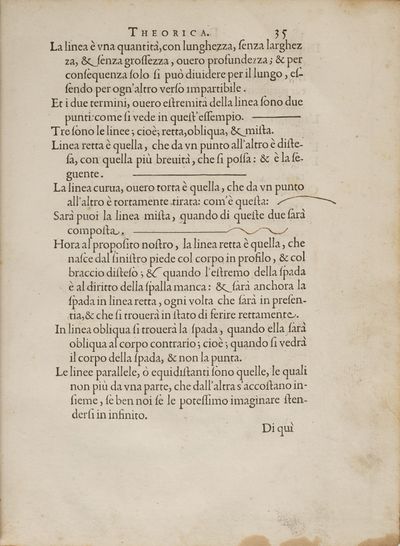

Now that we have dealt with the offensive & defensive instrument, we will continue to speak of the place. |

[30.3] Hor che dell’instrumento offensiuo, & difensiuo habbiamo trattato, seguitaremo à dir del luogo. | |

The place, therefore, will be every kind of site: and because most of the time duels are fought on the public streets of the Cities; which are often disastrous both for the dandies and for being uneven: therefore we must adapt ourselves to every kind of site: which we will do, if we keep the body balanced; and the weight of it well distributed in the legs. |

[30.4] IL luogo dunque farà ogni sorte di sito: & perche per il più si viene à duello nelle strade publiche delle Città; le quali spesso sono disastrose sì oer gli dandhi; sì per esser mal piane: perciò noi ci do ueremo accomodare ad ogni sorte di sito: il che faremo, se terremo unito il corpo; & ben compartito il peso d’esso nelle basi. | |

The sixth condition, which is the manner in which we offend others and defend ourselves, consists principally in securing our body against the enemy’s offense; and therefore the offense will never be taken if we are not first certain of the defense. Nor will we ever defend ourselves simply, if at the same time we do not offend, for the true defense is to offend, which we will do with resolution; and if we are always the first to execute the attack.[68] |

[31.1] LA sesta conditione, la quale è il modo, secondo che offendiamo altri, & difendiamo noi stessi, consiste principalmente nel’assicurar il nostro corpo dall’oddesa del nemico: & perciò l’offesa nó si fará mai, se prima noi non saremo sicuri della difesa; ne mai si idenderemo simplicemente, se nell’istesso tempo non offenderemo: perche la ver difesa è l’offendere: il che si farà con risolutione; & se saremo sempre i primi ad essequir la ferita. | |

These offenses give rise to two types of attacks: those of the cut and those of the point. |

[31.2] Da queste offese nascono due spetie di ferite: che sono di taglio, & di punta. | |

The cut has all these properties, that is to say, it is more natural to man than the point, since the motions of man are circular, it seeks a portion of the opposite body. It is a natural motion, and because it is more visible, it induces fear. It can also terminate in whatever part one wishes.[69] |

[31.3] Il taglio hà tutte queste proprietà; cioè; l’esser più naturale all’huomo, che la punta: atteso che i moti dell’huomo sono circolari: Ricerca maggior portione del corpo contrario: È moto naturale: Per esser più visibile, induce timore. Può anchor terminar in qual si voglia parte. | |

Nevertheless it has these imperfections; that is to say, it has the capacity to expose the right side of the body and the lower arm; and it is not mortal, since it resists the bones and the weapons; in addition to the figure of the body of the sword – which for not being spherical and therefore not being of equal weight – often resists the air and wounds flat; and the sword is prone to breaking. |

[31.4] Nientendimeno hà queste imperfettioni; cioè; di scuoprir il destro lato del corpo, & l’istensso braccio; & non è mortale, à quello risistendo l’ossa & l’armi: oltre che per la figura del corpo della spada, la quale per non esser sferica, & perciò di peso non vgual mente grave, molte volte risistendoui l’ aere ferisce di piatto: & la spada è soggetta al rompersi. | |

The point is drawn with the body covered; and it arrives sooner than it is seen: and therefore it is more irreparable and it is of less movement. And because of the shape of the sword, which is made in the shape of a wedge, it wounds more surely, and is more deadly: and it will therefore be better to use than the cut.[70] |

[32a.1] La punta si tira col corpo coperto; & prima arriua, che che sia veduta: & però è più irreparabile; & è di minor moto: & per la forma della spada, la qual è fatta à cuneo, ferisce più sicuramente, & è più mortale: sarà dunque meglio da usarsi, che il taglio. | |

The cut is divided into three simple and two compound natures. |

[32a.2] Il taglio poi si diuide in tre nature semplici, & due composte. | |

Of these three natures of the cut, And all these three natures are divided into dritti[74] and roversi;[75] the dritti are those which come from the lesser side. And these dritti and roversi divide the circle of man into eight equal parts, as can be seen in the figure below.[76] |

[32a.3] Di queste tre nature di taglio, il primo è il fendente; il secondo il traversale; il terzo il tondo: Et tutte questre tre nature si diuidono in diritti, & roversi: i diritti sono quelli, che vengono dalle parti dellato manco. Et questi diritti, & roversi diuidono il circolo dell’huomo in otto parti eguali: come quì si vede nella figura sequente. | |

Of the two compound natures, the first is the diritto ridoppiato,[77] which is started with the true edge of the sword underneath and goes to wound the tip of the enemy’s right shoulder. |

[32b.1] Delle due nature composte l’una è il diritto ridoppiato, il quale si parte col filo diritto della spada disotto, & và à ferir’alla punta della spalla diritta del nemico. | |

The second is the stramazzone,[78] which is made with the knot of the hand in the manner of a molinello:[79] and the reversi are so called because they are placed opposite; beginning on the left side and ending on the right, and are of the same nature as the mandritti. |

[32b.2] La seconda è lo stramazzone, il qual si fà col nodo di mano à guisa di molinello: & i riversi così si chiamano, perche sono posti à dirimpetto; cominciando dalle parti sinistre, & finendo nelle diritte: & sono delle medesime nature de’mandritti. | |

The straight cut, because of its descent of natural motion to the center of the world[80] [downwards due to gravity], is heavier than the other two: for it forms the line of direction to which the more its motions are connected with its weight, the more serious they are. |

[32b.3] Il taglio retto, per il suo descenso di moto naturale al centro del mondo, è più graue di gli altri due: poi che forma la linea della direttione, alla quale quan to più s’auicinano nelli suoi moti i pesi, tanto più sono gravi. | |

On the other hand, by occupying the imagined line, it does not allow a place for the opposite sword to enter in defense, as is the case with oblique cuts, which are all those lines that follow the angle formed by the line of the fendente and the tondo fendente. |

[32b.4] Oltra di questo occupando la linea imaginata non concede luogo, per il quale entri in difesa la spada contraria: come fanno i tagli obliqui, i quali sono tutte quelle linee, che segano l’angolo constituito dalla linea del diritto fendente retto, & del tondo fendente. | |

Therefore, the more these transversal cuts approach the perpendicular descent towards the center of the world; and the more they make an acute angle with the line of direction, the more they will approach the perfection of the cut. And on the contrary, the more they move away from it, and approach the horizontal line of the diritto tondo, the less they will make an acute angle; and consequently they will be more oblique; and therefore of less weight and strength. |

[32b.5] Però questi tagli traversali quanto più s’auicinaranno al perpendicolar descenso verso il centro del mondo; & quanto più faráno angolo acuto con la linea della direttione, tanto più si auicineranno alla per- [33b.1] fettione del taglio: & per il contrario quanto più se ne allontaneranno, & si approssimaranno alla linea Orizontale del diritto tondo, tanto meno formaranno anglo acuto; & per conseguenza saranno più obliqui; & perciò di minor peso, & forza. | |

From the description of the fendente tondo[81] and everything that has been said about mandritti, if it can be understood sufficiently, can be understood about the reversi, since they are of the same nature. |

[33b.2] Il fendente tondo dalla descrittione di questi due si può intendre à bastanza: & tutto quello, che si è detto de’mandritti, tutto quello si deue intendere de’roversi, poiche sono delle medesime nature. | |

All these cuts can be made by attacking with the wrist with a certain continuous motion; that is to say, aided from the beginning until the end by the power of the wrist. The man is more easily helped by the force of his body, (than by the force of his motion) and of the body as a whole; which then is aided by the reason of cutting through the middle;[82] which makes the wound greater. And, this has some good appearance, as the man in the process of being attacked is covered and lurches unevenly, and is more concerted in the operation.[83] |

[33b.3] Tutti questi tagli si possono essequire ferendo di polso con un certo moto continuo; cioè; aiutato dal principio, per sino al dine dalla possanza mouente: seruendosi più tosto l’huomo della forza del suo corpo, che di quella del moto, & del corpo insieme; il che poi s’aiuta con la ragione del segare; che fà la ferita maggiore: & ciò hà qualche apparenza buona: oltre che l’huomo in tral ferire è coperto; & si sbanda manco; & và più concertato nell’operatione. | |

But since the blow is a very strong force, as Aristotle declares in the ‘Decimation of the Mechanic Treatises’, we will conclude that all attacks, in order to be perfect, will be helped by the force of the body and by the blow. |