|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Fiore de'i Liberi"

| (180 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

| name = [[name::Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi]] | | name = [[name::Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi]] | ||

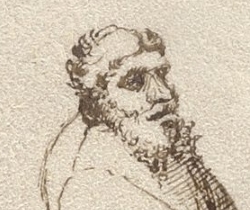

| image = File:Fiore delli Liberi.jpg | | image = File:Fiore delli Liberi.jpg | ||

| − | | imagesize = | + | | imagesize = 300px |

| − | | caption = This | + | | caption = This man appears sporadically throughout both the Getty and Pisani Dossi MSS, and may be a representation of Fiore himself. |

| pseudonym = | | pseudonym = | ||

| birthname = | | birthname = | ||

| − | | birthdate = | + | | birthdate = |

| − | | birthplace = Cividale del | + | | birthplace = Cividale del Friuli |

| − | | deathdate = | + | | deathdate = |

| − | | deathplace = | + | | deathplace = |

| resting_place = | | resting_place = | ||

| − | | occupation = {{plainlist | [[ | + | | occupation = {{plainlist |

| − | | language = {{plainlist | [[language::Middle Italian]] | [[language::Renaissance Latin]] }} | + | | [[Fencing master]]{{#set: occupation=Fencing master }} |

| + | | [[occupation::Mercenary]] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | | language = {{plainlist | ||

| + | | [[language::Middle Italian]] | ||

| + | | [[language::Renaissance Latin]] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| nationality = Friulian | | nationality = Friulian | ||

| ethnicity = | | ethnicity = | ||

| Line 19: | Line 25: | ||

| education = | | education = | ||

| alma_mater = | | alma_mater = | ||

| − | | patron = {{plainlist | Gian Galeazzo Visconti (?) | Niccolò | + | | patron = {{plainlist |

| + | | Gian Galeazzo Visconti (?) | ||

| + | | Niccolò Ⅲ d’Este (?) | ||

| + | }} | ||

| period = | | period = | ||

| − | | genre = {{plainlist | [[Fencing manual]] | [[Wrestling manual]] }} | + | | genre = {{plainlist |

| + | | [[Fencing manual]] | ||

| + | | [[Wrestling manual]] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| subject = | | subject = | ||

| movement = | | movement = | ||

| notableworks = ''The Flower of Battle'' | | notableworks = ''The Flower of Battle'' | ||

| − | | manuscript(s) = {{ | + | | manuscript(s) = {{collapsible list |

| − | | | + | | [[Trattato della scherma (MS M.383)|MS M.383]] (1400s) |

| − | + | | [[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|MS Ludwig ⅩⅤ 13]] (1400s) | |

| − | | | + | | [[Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)|Pisani Dossi MS]] (1409) |

| − | | | + | | [[Florius de Arte Luctandi (MS Latin 11269)|MS Latin 11269]] (1410s?) |

| − | | | + | | [[Fior di Battaglia (MS XXIV)|MS XXIV]] (1699) |

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

}} | }} | ||

| principal manuscript(s)= | | principal manuscript(s)= | ||

| Line 43: | Line 52: | ||

| partner = | | partner = | ||

| children = | | children = | ||

| − | | relatives = Benedetto de’i Liberi | + | | relatives = Benedetto de’i Liberi (father) |

| − | | influences = {{plainlist | [[Johannes Suvenus|Johane Suveno]] | [[Nicholai de Toblem]] }} | + | | influences = {{plainlist |

| + | | [[Johannes Suvenus|Johane Suveno]] | ||

| + | | [[Nicholai de Toblem]] | ||

| + | }} | ||

| influenced = [[Philippo di Vadi]] | | influenced = [[Philippo di Vadi]] | ||

| awards = | | awards = | ||

| signature = | | signature = | ||

| website = | | website = | ||

| − | | translations = {{ | + | | translations = {{collapsible list |

| + | | {{English translation|http://www.fioredeiliberi.org/morgan/}} | ||

| + | | {{English translation|https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/File:Getty_MS_Ludwig_XV_13_Scans_with_English_Translation.pdf}} | ||

| + | | {{English translation|http://www.fioredeiliberi.org/getty/}} | ||

| + | | {{English translation|https://www.aemma.org/onlineResources/liberi/wildRose/fiore.html}} | ||

| + | | {{English translation|http://www.the-exiles.org.uk/fioreproject/}} | ||

| + | | {{French translation|{{fullurl:{{PAGENAMEE}}/French}}|1}} | ||

| + | | {{Hungarian translation|http://www.middleages.hu/magyar/harcmuveszet/vivokonyvek/liberi.php|1}} | ||

| + | | {{Spanish translation|http://www.salafenix.eu/docs/biblio/tratados/Fiore_Dei_Liberi.Flos_Duellatorum.1410.es.pdf|1}} | ||

| + | }} | ||

| below = | | below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi de Cividale d’Austria''' (Fiore delli Liberi, Fiore Furlano, Fiore de Cividale d’Austria; | + | '''Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi de Cividale d’Austria''' (Fiore delli Liberi, Fiore Furlano, Fiore de Cividale d’Austria; fl. 1381 - 1409) was a late [[century::14th century]] knight, diplomat, and [[fencing master]]. He was born in Cividale del Friuli, a town in the Patriarchal State of Aquileia (in the Friuli region of modern-day Italy), the son of Benedetto and scion of a Liberi house of Premariacco.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan">[[Fiore de'i Liberi]]. ''Fior di Battaglia'' [manuscript]. [[Trattato della scherma (MS M.383)|MS M.383]]. New York City: [[Morgan Library & Museum]], ca. 1400. ff 1r-2r.</ref><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty">[[Fiore de'i Liberi]]. ''Fior di Battaglia'' [manuscript]. [[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|MS Ludwig ⅩⅤ 13]] (ACNO 83.MR.183). Los Angeles: [[J. Paul Getty Museum]], ca. 1400. ff 1r-2r.</ref><ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi">[[Fiore de'i Liberi]]. ''Flos Duellatorum'' [manuscript]. [[Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)|Pisani Dossi MS]]. Italy: Private Collection, 1409. f 1rv.</ref> The term ''Liberi'', while potentially merely a surname, more probably indicates that his family had Imperial immediacy (''Reichsunmittelbarkeit''), either as part of the ''nobili liberi'' (''Edelfrei'', "free nobles"), the Germanic unindentured knightly class which formed the lower tier of nobility in the Middle Ages, or possibly of the rising class of Imperial Free Knights.<ref>He is never given such a surname in any contemporary records of his life, and the term only appears when introducing his family in his own treatises.</ref><ref name="Mondschein 11">Mondschein, p 11.</ref><ref>Howe, Russ. “[http://ejmas.com/jwma/articles/2008/jwmaart_howe_0808.htm Fiore dei Liberi: Origins and Motivations]”. [[Journal of Western Martial Art]]. Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences, 2008. Retrieved 2015-11-23.</ref> It has been suggested by various historians that Fiore and Benedetto were descended from Cristallo dei Liberi of Premariacco, who was granted immediacy in 1110 by Holy Roman Emperor Heinrich V,<ref>Giusto Fontanini. {{Google books|929Oruf2qScC|Della Eloquenza italiana di monsignor Giusto Fontanini|page=274}}, vol. 3 (in Italian). R. Bernabò, 1736. pp 274-276.</ref><ref>Gian Guiseppe Liruti. {{Google books|swCiIpD6UeIC|Notizie delle vite ed opere scritte da' letterati del Friuli|page=27}}, vol. 4 (in Italian). Alvisopoli, 1830. p 27.</ref><ref>Novati, pp 15-16.</ref> but this has yet to be proven.<ref>Malipiero, p 80.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | Fiore wrote that he had a natural inclination to the martial arts and began training at a young age, ultimately studying with “countless” masters from both Italic and Germanic lands.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> He had ample opportunity to interact with both, traveling widely in the Italian states that formed the border of the Holy Roman Empire. Unfortunately, not all of these encounters were friendly: Fiore wrote of meeting many “false” or unworthy masters in his travels, most of whom lacked even the limited skill he'd expect in a good student.<ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> He further mentions that on five separate occasions he was forced to fight [[duel]]s for his honor against certain of these masters who he described as envious because he refused to teach them his art; the duels were all fought with sharp swords, unarmored except for gambesons and chamois gloves, and he won each without injury.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty"/><ref>15th century jurist [[Paride del Pozzo]], in discussing Italian dueling customs, dismisses unarmored duels as the ignoble domain of the rash and the hot-headed, contrasted with honorable dueling done in armor with the full range of military weapons. This might provide insight into Fiore's disposition as a young man. See Pozzo book 4, chapter 3, and also Leoni 2012, pp ⅹⅹⅳ-ⅹⅹⅴ.</ref> | ||

| − | Fiore | + | Writing very little on his own career as ''condottiero'', Fiore laid out his credentials for his readers in other ways. He stated that foremost among the masters who trained him was one [[Johannes Suvenus|Johane dicto Suueno]], who he notes was a disciple of [[Nicholai de Toblem]];<ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> unfortunately, both names are given in Latin so there is little we can conclude about them other than that they were probably among the Italians and Germans he alludes to, and that one or both were well known in Fiore's time. He further offered an extensive list of the famous ''condottieri'' that he trained, including Piero Paolo del Verde (Peter von Grünen),<ref>[http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-v/2660-piero-del-verde “PIERO DEL VERDE (Paolo del Verde) Tedesco. Signore di Colle di Val d’Elsa.”]. ''Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 - 1550''. Retrieved 2015-11-23.</ref> Niccolo Unricilino (Nikolo von Urslingen),<ref>Leoni, p 7.</ref> Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli (Galeazzo Gonzaga da Mantova),<ref name="Galeazzo">[http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-m/1450-galeazzo-da-mantova “GALEAZZO DA MANTOVA (Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli, Galeazzo Gonzaga) Di Mantova. Secondo alcune fonti, di Grumello nel pavese.”]. ''Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 - 1550''. Retrieved 2015-11-23.</ref> Lancillotto Beccaria di Pavia,<ref>[http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-b/630-lancillotto-beccaria “LANCILLOTTO BECCARIA (Lanciarotto Beccaria) Di Pavia. Ghibellino. Signore di Serravalle Scrivia, Casei Gerola, Bassignana, Novi Ligure, Voghera, Broni.”]. ''Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 - 1550''. Retrieved 2015-11-23.</ref> Giovannino da Baggio di Milano,<ref name="Malipiero 9496">Malipiero, pp 94-96.</ref> and Azzone di Castelbarco,<ref name="Jens">[https://talhoffer.wordpress.com/2013/04/24/fiore-his-master-and-his-students/ Fiore his masters and his students]. ''Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau.'' Retrieved 2015-11-23.</ref> and also highlights some of their martial exploits.<ref name="de’i Liberi Morgan"/><ref name="de’i Liberi Getty"/> |

| − | + | The only known historical mentions of Fiore appear in connection with the Aquileian War of Succession, which erupted in 1381 as a coalition of secular nobles from Udine and surrounding cities sought to remove the newly appointed patriarch (prince-bishop of Aquileia), Cardinal Philippe Ⅱ d'Alençon. Fiore seems to have supported the secular nobility against the cardinal; he traveled to Udine in 1383 and was granted residency in the city on 3 August.<ref>Malipiero, p 84.</ref> On 30 September, the high council tasked him with inspection and maintenance of city's weapons, including the [[artillery]] pieces defending Udine (large crossbows and catapults).<ref name="Mondschein 11"/><ref>Malipiero, p 85.</ref><ref name="Easton">[[Matt Easton|Easton, Matt]]. “[http://www.fioredeiliberi.org/fiore/ Fiore dei Liberi - Fiore di Battaglia - Flos Duellatorum]”. London: Schola Gladiatoria, 2009. Retrieved 2015-11-23.</ref> In February of 1384, he was assigned the task of recruiting a mercenary company to augment Udine's forces and leading them back to the city.<ref>Malipiero, p 86.</ref> This task seems to have been accomplished in three months or less, as on 23 May he appeared before the high council again and was sworn in as a sort of magistrate charged with keeping the peace in one of the city's districts. After May 1384, the historical record is silent on Fiore's activities; the war continued until a new Patriarch was appointed in 1389 and a peace settlement was reached, but it's unclear if Fiore remained involved for the duration. Given that he appears in council records four times in 1383-4, it would be quite odd for him to be completely unmentioned over the subsequent five years if he remained,<ref name="Mondschein 11"/><ref>Malipiero, pp 85-88.</ref> and since his absence from records coincides with a proclamation in July of that year demanding that Udine cease hostilities or face harsh repercussions, it seems more likely that he moved on. | |

| − | Based on | + | Based on his autobiographical account, Fiore traveled a good deal in northern Italy, teaching fencing and training men for duels. He seems to have been in Perugia in 1381 in this capacity, when his student Peter von Grünen likely fought a duel with Peter Kornwald.<ref>This is the only point when both men are known to have been in Perugia at the same time; Verde died soon after this in 1385. See [https://talhoffer.wordpress.com/2013/04/24/fiore-his-master-and-his-students/ Fiore his masters and his students], ''Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau'', in English and [http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-v/2660-piero-del-verde “PIERO DEL VERDE (Paolo del Verde) Tedesco. Signore di Colle di Val d’Elsa.”] and [http://www.condottieridiventura.it/index.php/lettera-c/971-pietro-della-corona “PIETRO DELLA CORONA (Pietro Cornuald) Tedesco. Signore di Angri.”], ''Note biografiche di Capitani di Guerra e di Condottieri di Ventura operanti in Italia nel 1330 - 1550'', in Italian. Retrieved 2015-11-23.</ref> |

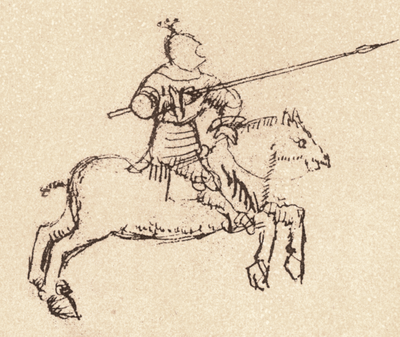

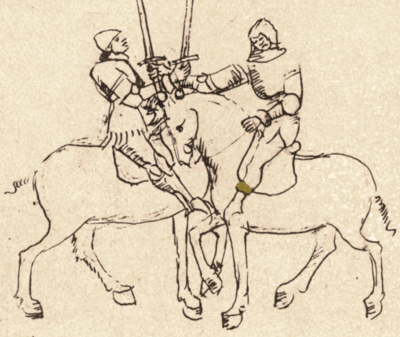

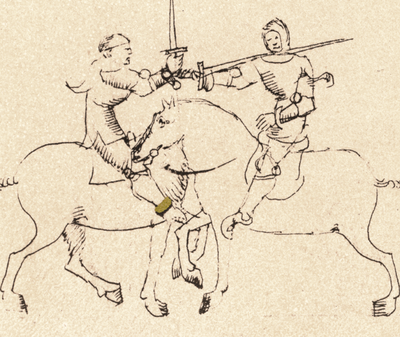

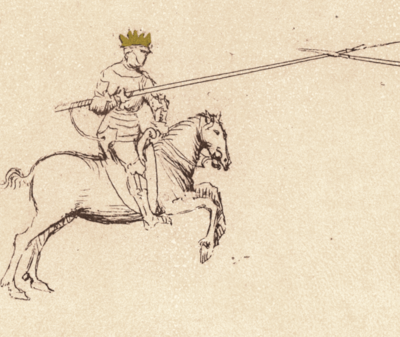

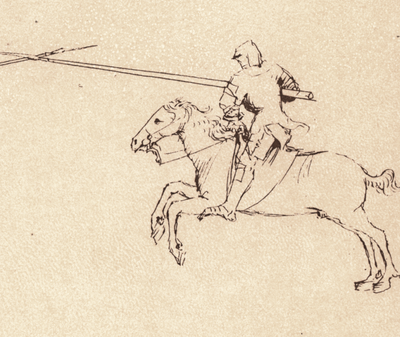

| − | + | In 1395, he can be placed in Padua training the mercenary captain Galeazzo Gonzaga of Mantua for a duel with the French marshal Jean Ⅱ le Maingre (who went by the war name “Boucicaut”). Galeazzo made the challenge when Boucicaut called into question the valor of Italians at the royal court of France, and the duel was ultimately set for Padua on 15 August. It was jointly hosted by Francesco Novello da Carrara, Lord of Padua, and Francesco Gonzaga, Lord of Mantua. The duel was to begin with [[spear]]s on [[:category:Mounted Fencing|horseback]], but Boucicaut became impatient and dismounted, attacking Galeazzo before he could mount his own horse. Galeazzo landed a solid blow on the Frenchman’s helmet, but was subsequently disarmed. At this point, Boucicaut called for his poleaxe but the lords intervened to end the duel.<ref>Malipiero, pp 55-58.</ref><ref name="Easton"/><ref name="Galeazzo"/> | |

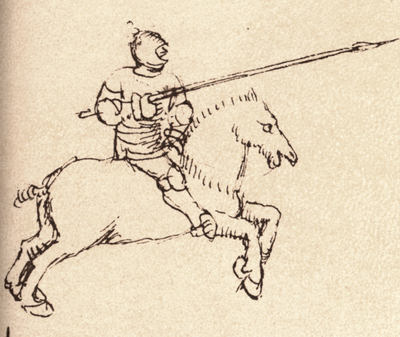

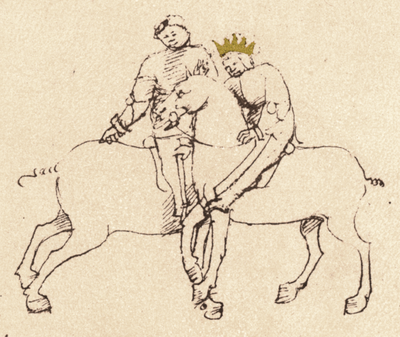

| − | Fiore | + | Fiore surfaced again in Pavia in 1399, this time training Giovannino da Baggio for a duel with a German squire named Sirano. It was hosted by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Duke of Milan, and fought on 24 June. The duel was to consist of three bouts of mounted lance followed by three bouts each of dismounted [[poleaxe]], [[estoc]], and [[dagger]]. They ultimately rode two additional passes and on the fifth, Baggio impaled Sirano’s horse through the chest, slaying the horse but losing his lance in the process. They fought the other nine bouts as scheduled, and due to the strength of their armor (and the fact that all of the weapons were blunted), both combatants reportedly emerged from these exchanges unharmed.<ref name="Malipiero 9496"/><ref name="Mondschein 12">Mondschein, p 12.</ref> |

| − | Fiore was likely involved in at least one other duel that year, that of his final student Azzone di Castelbarco | + | Fiore was likely involved in at least one other duel that year, that of his final student Azzone di Castelbarco against Giovanni degli Ordelaffi, as the latter is known to have died in 1399.<ref>Malipiero, p 97.</ref> After Castelbarco’s duel, Fiore’s activities are unclear. Based on the allegiances of the nobles that he trained in the 1390s, he seems to have been associated with the ducal court of Milan in the latter part of his career.<ref name="Easton"/> Some time in the first years of the 1400s, Fiore composed a fencing treatise in Italian and Latin called "The Flower of Battle" (rendered variously as ''Fior di Battaglia'', ''Florius de Arte Luctandi'', and ''Flos Duellatorum''). The briefest version of the text is dated to 1409 and indicates that it was a labor of six months and great personal effort;<ref name="de’i Liberi Pisani Dossi"/> since evidence suggests that at least two longer versions were composed some time before this,<ref>Fiore states in the preface to the [[Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)|Pisani Dossi MS]] that he had studied combat for fifty years, whereas the comparable statement in the [[Trattato della scherma (MS M.383)|MS M.383]] and [[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|MS Ludwig ⅩⅤ 13]] mention the slightly shorter "forty years and more".</ref> we may assume that he devoted a considerable amount of time to writing during this decade. |

| − | Beyond this, nothing certain is known of Fiore's activities in the 15th century. [[Francesco Novati]] and [[ | + | Beyond this, nothing certain is known of Fiore's activities in the 15th century. [[Francesco Novati]] and [[Luigi Zanutto]] both assume that some time before 1409 he accepted an appointment as court fencing master to Niccolò Ⅲ d’Este, Marquis of Ferrara, Modena, and Parma; presumably he would have made this change when Milan fell into disarray in 1402, though Zanutto went so far as to speculate that he trained Niccolò for his 1399 passage at arms.<ref>Zanutto, pp 211-212.</ref> However, while the records of the d’Este library indicate the presence of two versions of "the Flower of Battle", it seems more likely that the manuscripts were written as a diplomatic gift to Ferrara from Milan when they made peace in 1404.<ref name="Mondschein 12"/><ref name="Easton"/> C. A. Blengini di Torricella stated that late in life he made his way to Paris, France, where he could be placed teaching fencing in 1418 and creating a copy of a [[fencing manual]] located there in 1420. Though he attributes these facts to Novati, no publication verifying them has yet been located and this anecdote may be entirely spurious.<ref>In 1907, fencing master C. A. Blengini di Torricella mentioned that “In 1904, a historical work by [[Francesco Novati]], Director of the Academy in Milano and Gaffuri, Director of the graphical institute in Bergamo was published… These two prominent scholars uncovered documents, found in different archives, …''Rules for Fencing'' were printed by Fiore dei Liberi in 1420… And how could then dei Liberi have taught fencing lessons in Paris in 1418?” (translated from Norwegian by [[Roger Norling]]). See Blengini, di Torricella C. A. ''Haandbog i Fægtning med Floret, Kaarde, Sabel, Forsvar med Sabel mod Bajonet og Sabelhugning tilhest: Med forklarende Tegninger og en Oversigt over Fægtekunstens Historie og Udvikling.'' 1907. p 28.{{full}}</ref> |

| − | + | The time and place of Fiore's death remain unknown. | |

| + | Despite the extent and complexity of his writings, Fiore de’i Liberi does not seem to have been a very significant master in the evolution of fencing in Central Europe. That field was instead dominated by the traditions of two masters of the subsequent generation: [[Johannes Liechtenauer]] in Bavaria and [[Filippo di Bartolomeo Dardi]] in Bologna. Even so, there are a few later treatises which bear strong resemblance to his work, including the writings of [[Philippo di Vadi]] and [[Ludwig VI von Eyb]]. This may be due to the direct influence of Fiore or his writings, or it may instead indicate that the older tradition of Johane and Nicholai survived and spread outside of Fiore's direct line. | ||

| + | {{TOC limit|3}} | ||

== Treatise == | == Treatise == | ||

| − | + | The d’Este family owned at least three manuscripts by Fiore during the 15th century,<ref>There are two records in the [https://archive.org/details/giornalestoricod14toriuoft/page/18/mode/2up 1436 catalog] and two records in the [https://books.google.com/books?id=yz5FAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA219 1467 catalog], but only one of the manuscript descriptions is similar between the catalogs. The 1436 catalog lists one unbound Latin manuscript and one Italian manuscript in red leather; the 1467 catalog lists two Latin manuscripts, one of which was only 15 unbound folia (probably the same as the one from 1436) and one of which was 58 folia bound in white leather. From this, we might speculate that the Getty manuscript was present in 1436, the Paris manuscript in 1467, and the third (very short) manuscript is currently unknown to us. If there were an error in the 1467 catalog, then the unknown manuscript could be the Pisani Dossi, which currently consists of 35 unbound folia.</ref> and a total of four copies survive to the present. Of these, the [[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|MS Ludwig ⅩⅤ 13]] (Getty) and the [[Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)|Pisani Dossi MS]] (Novati) are both dedicated to Niccolò Ⅲ d’Este and state that they were written at his request and according to his design. The [[Trattato della scherma (MS M.383)|MS M.383]] (Morgan), on the other hand, lacks a dedication and claims to have been laid out according to his own intelligence, while the [[Florius de Arte Luctandi (MS Latin 11269)|MS Latin 11269]] (Paris) lost any dedication it might have had along with its prologue. Each of the extant copies of the ''Flower of Battle'' follows a unique specific sequence of plays, though the Getty and Novati contain strong similarities to each other in order of presentation, as do the Morgan and Paris. | |

| − | + | In addition, Philippo di Vadi’s manuscript from the 1480s, whose second half is essentially a redaction of the ''Flower of Battle'', provides a valuable fifth point of reference when considering Fiore’s teachings. (These is also a 17th century copy of the Morgan’s preface, transcribed by Apostolo Zeno, but it contributes little to our understanding of the text.) | |

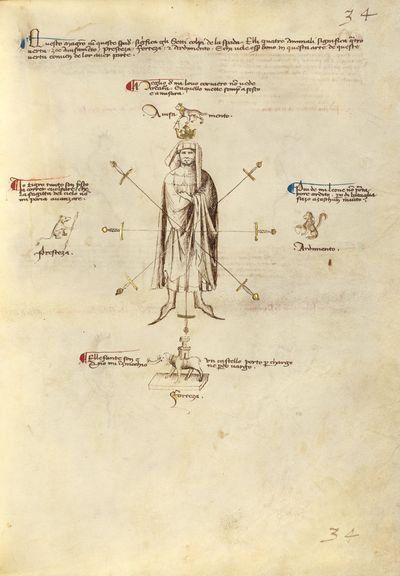

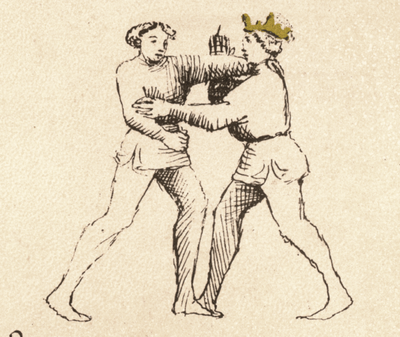

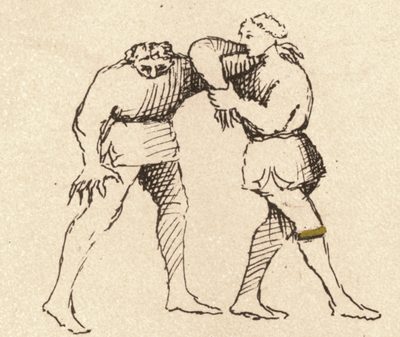

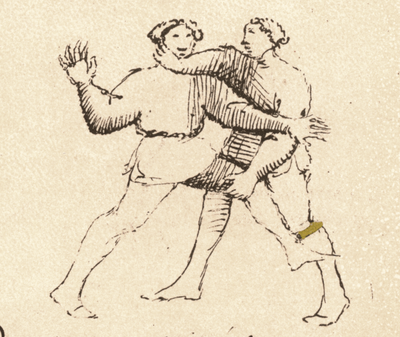

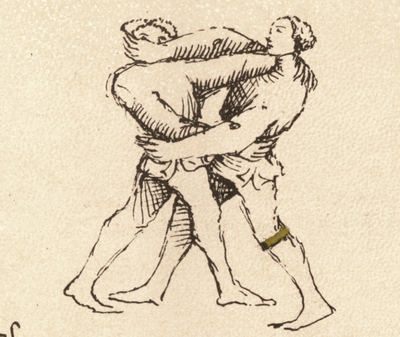

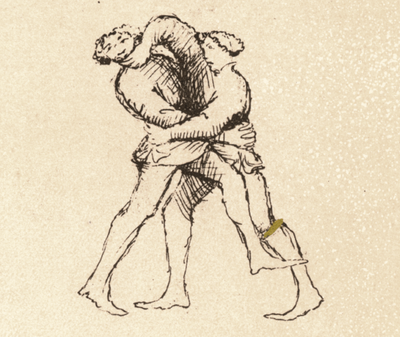

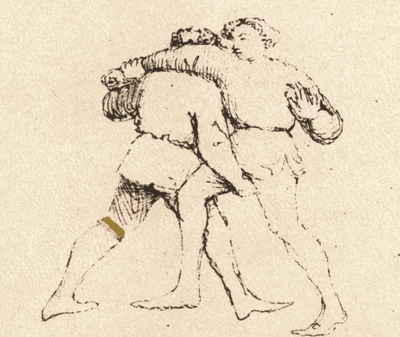

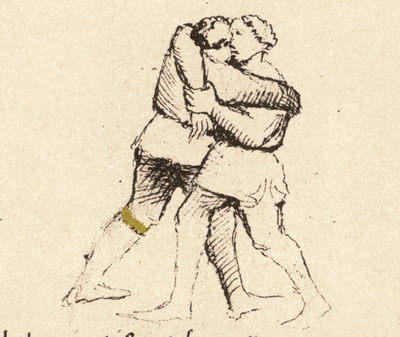

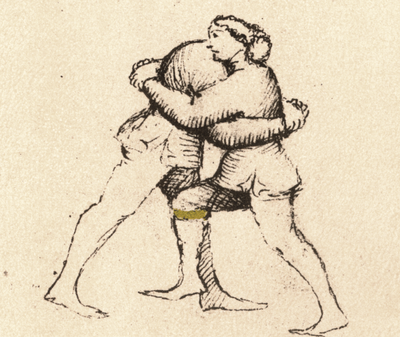

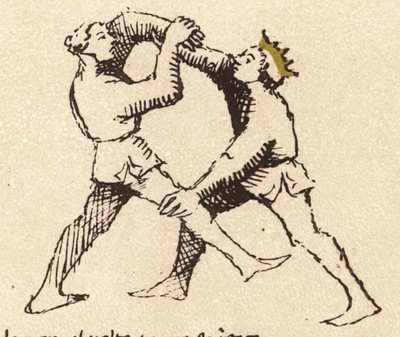

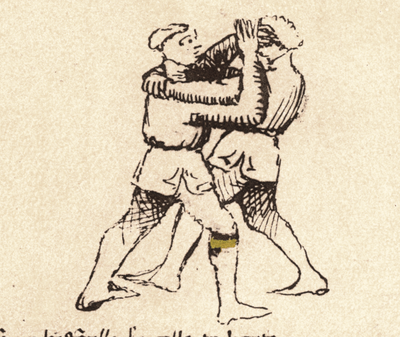

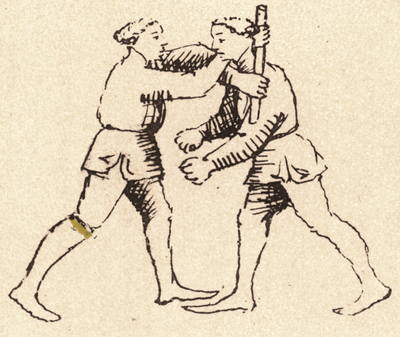

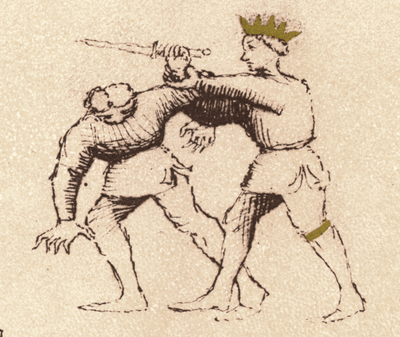

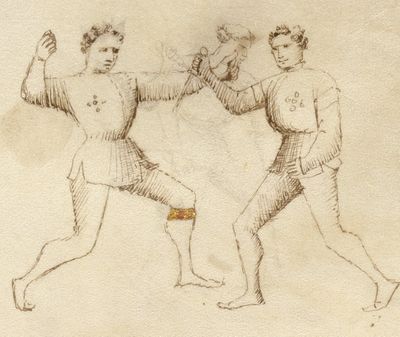

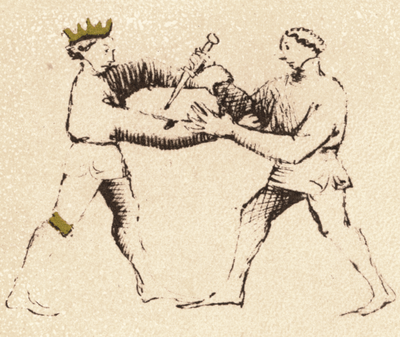

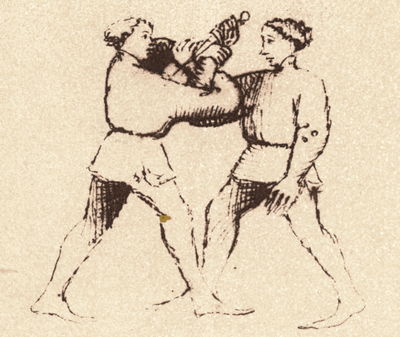

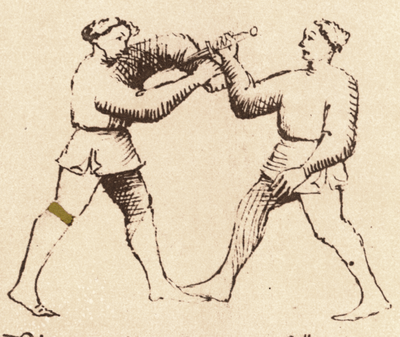

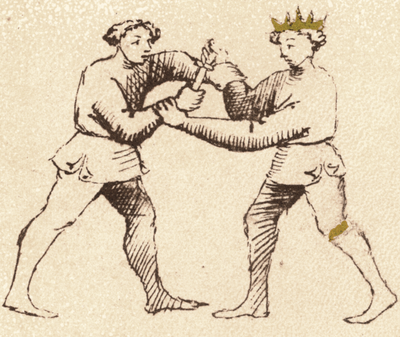

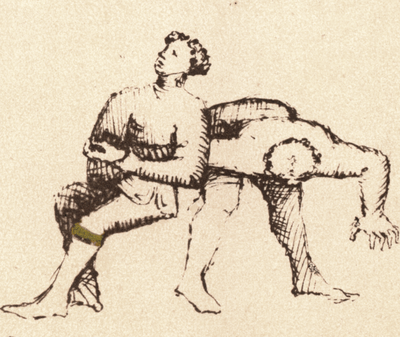

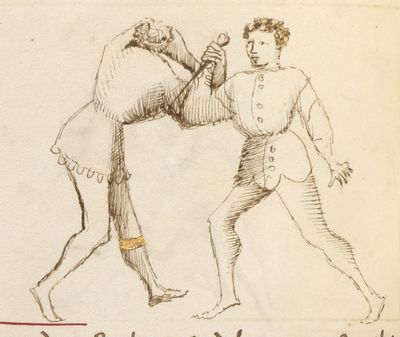

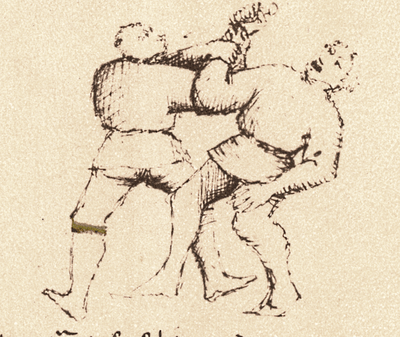

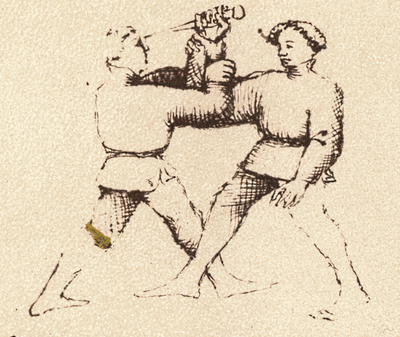

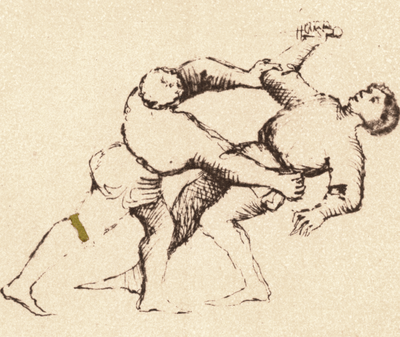

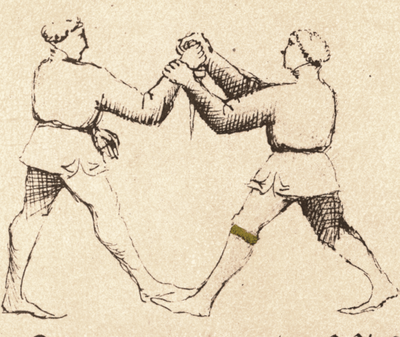

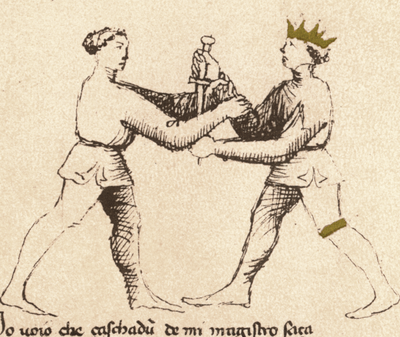

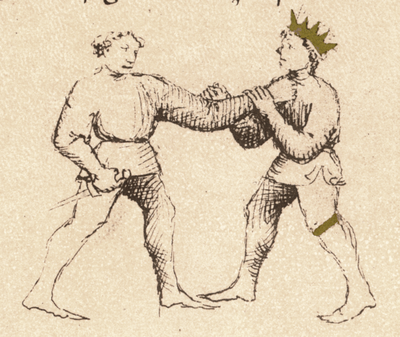

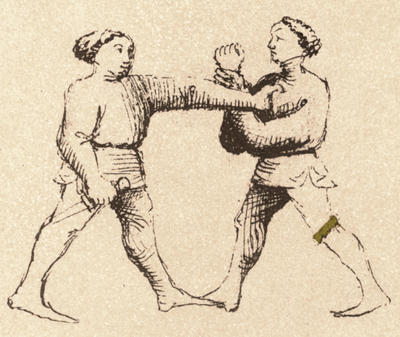

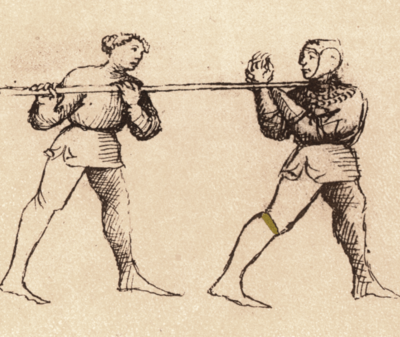

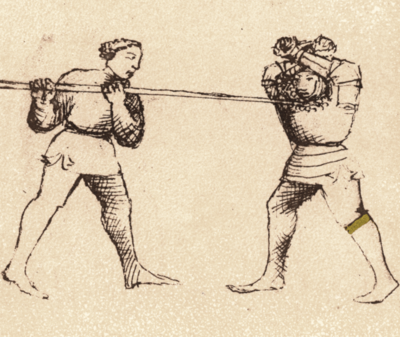

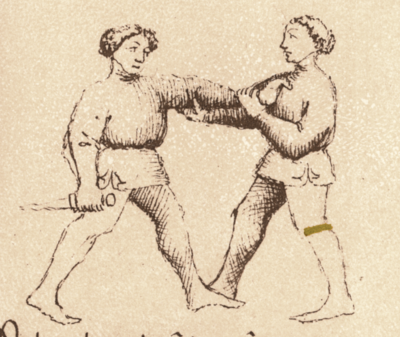

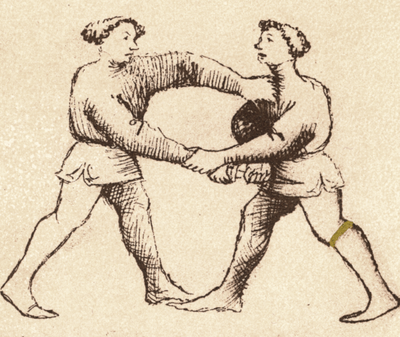

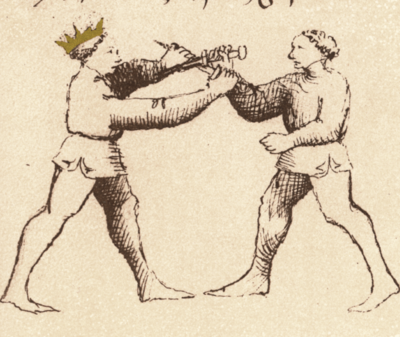

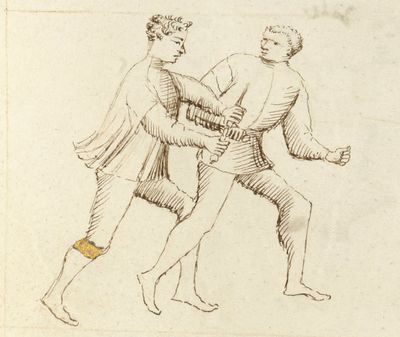

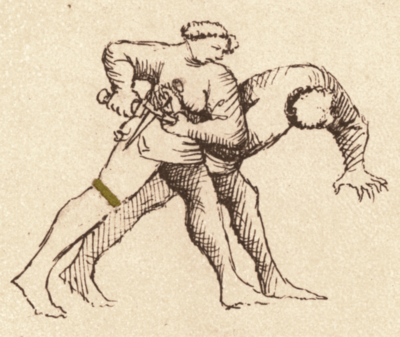

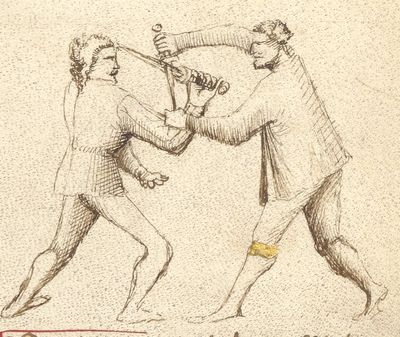

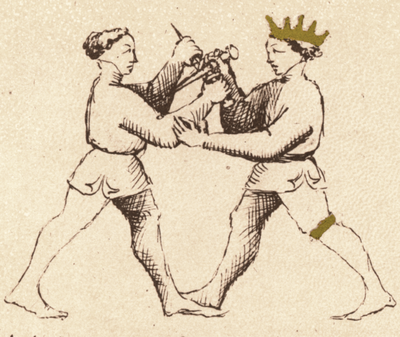

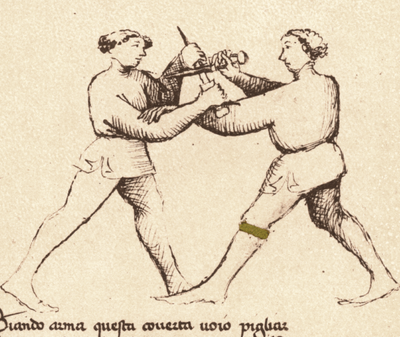

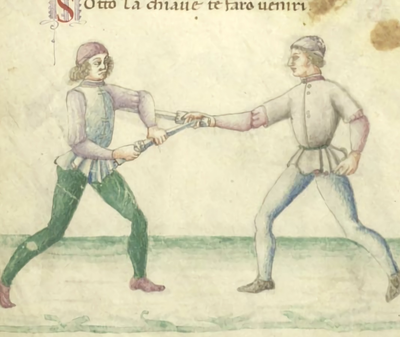

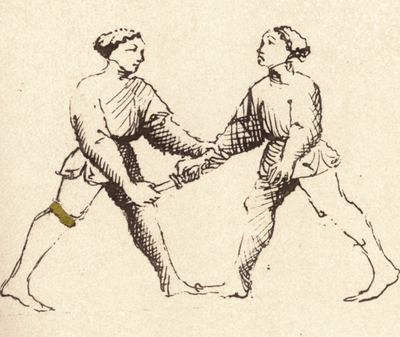

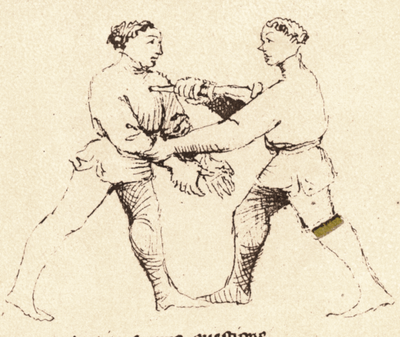

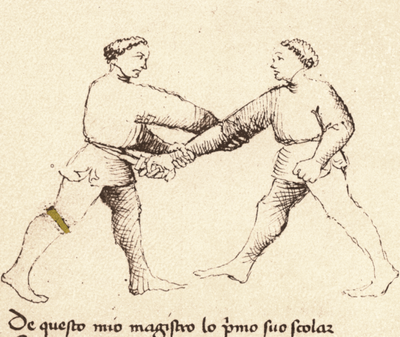

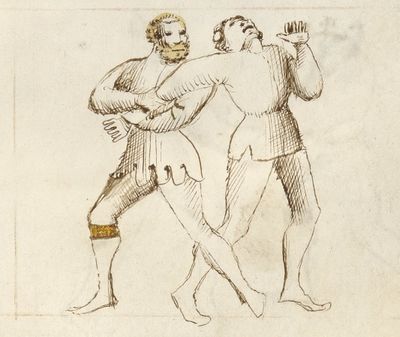

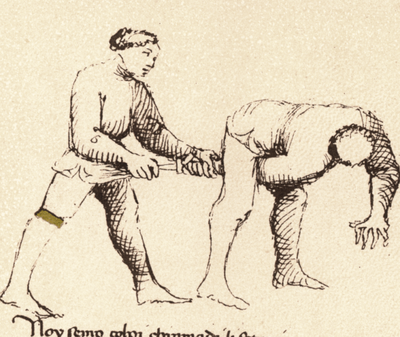

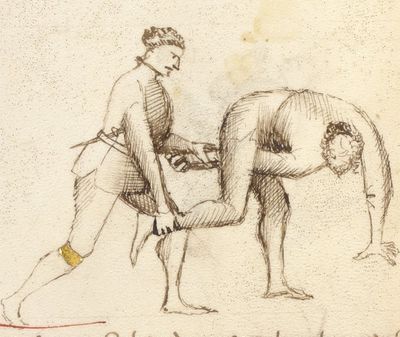

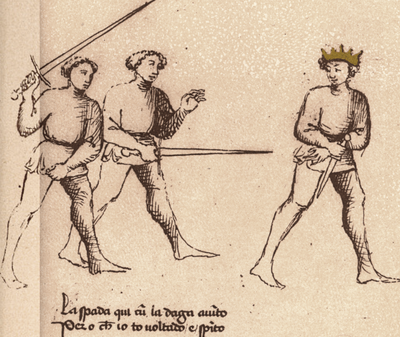

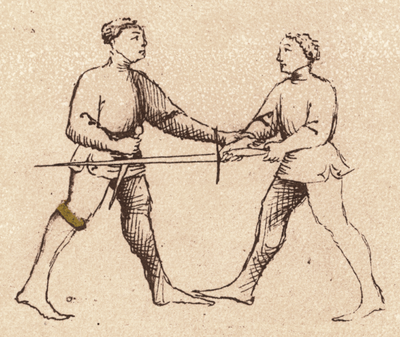

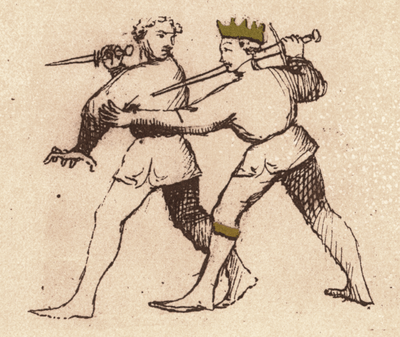

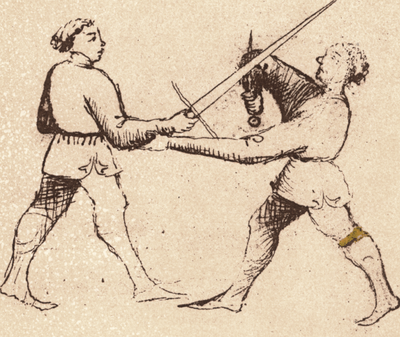

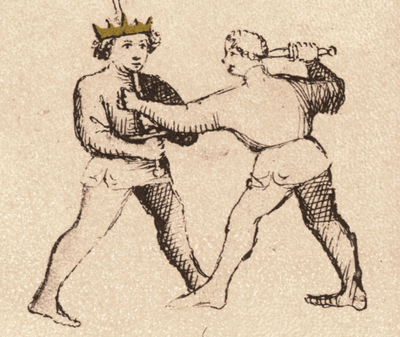

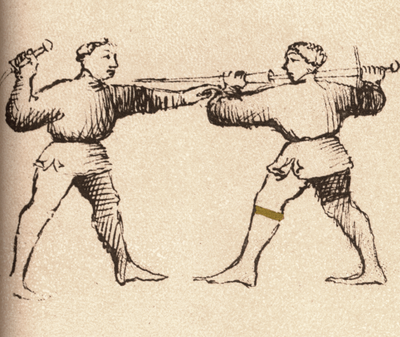

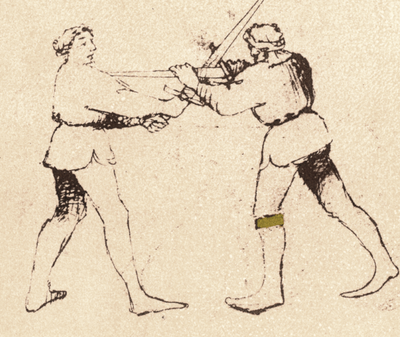

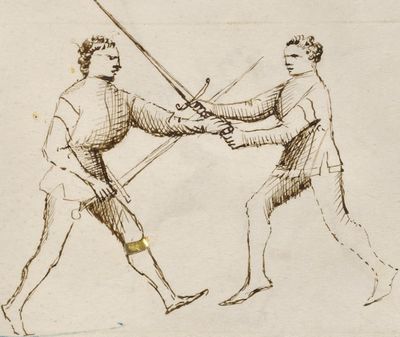

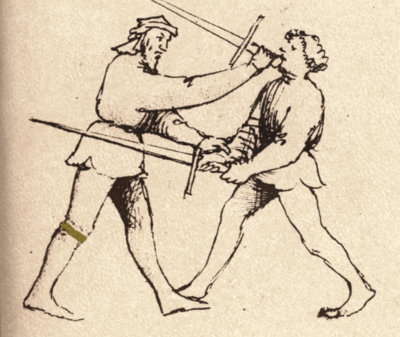

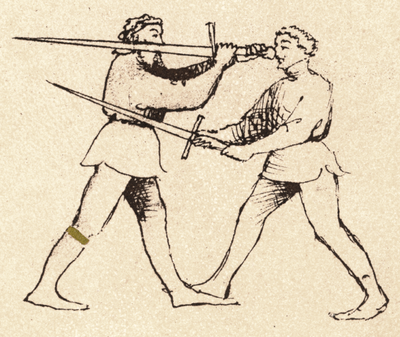

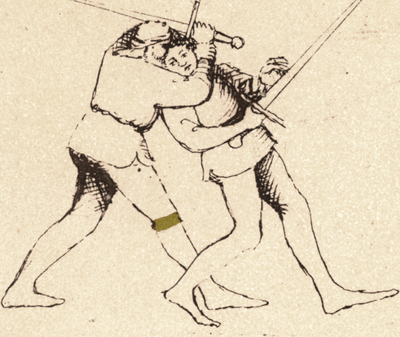

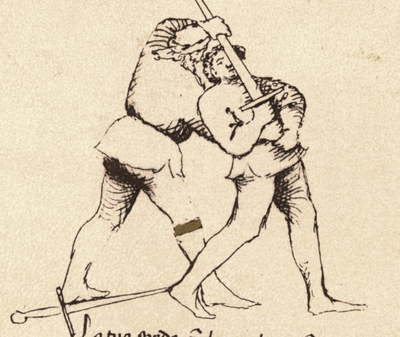

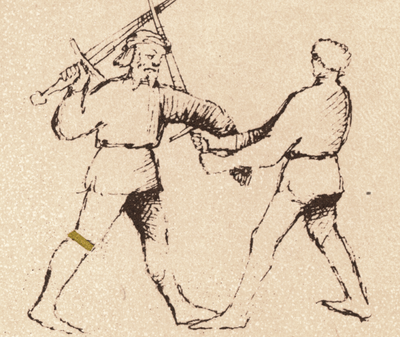

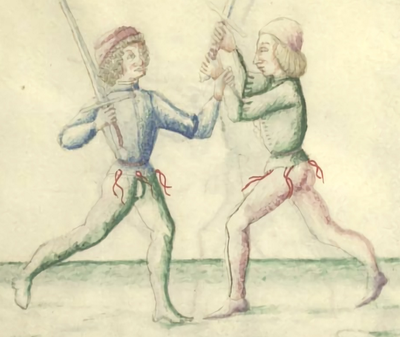

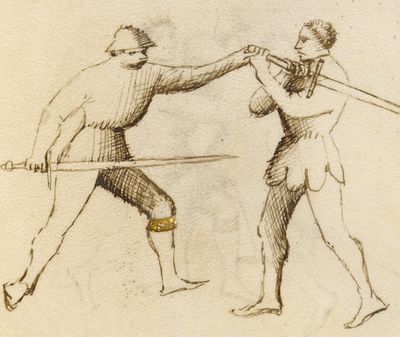

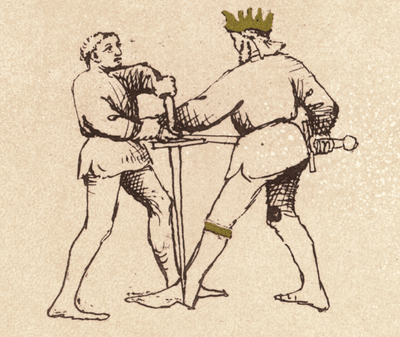

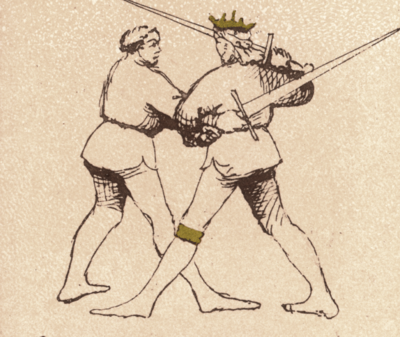

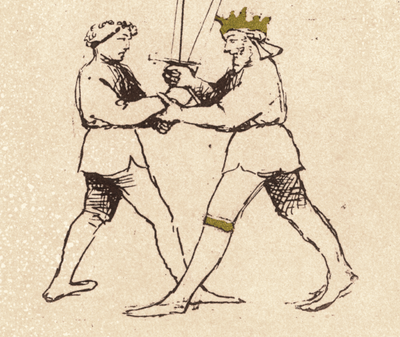

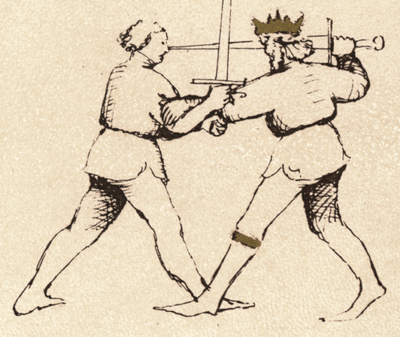

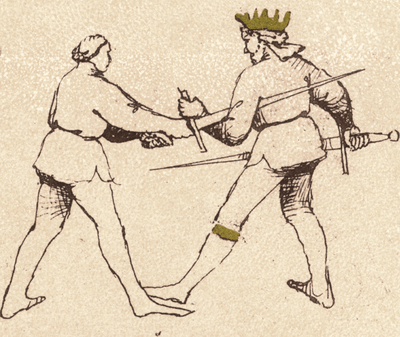

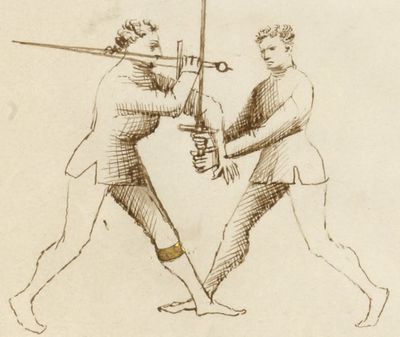

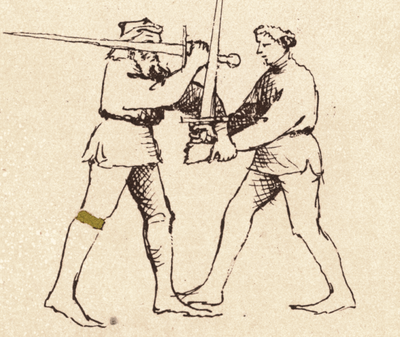

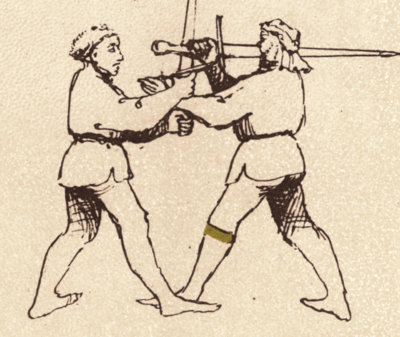

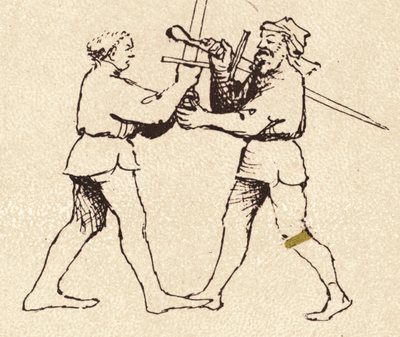

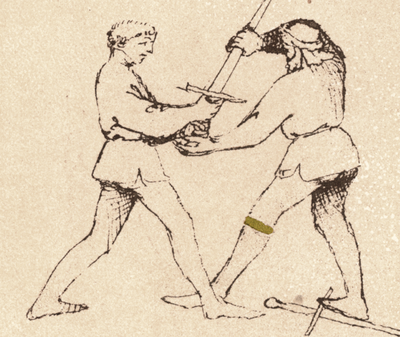

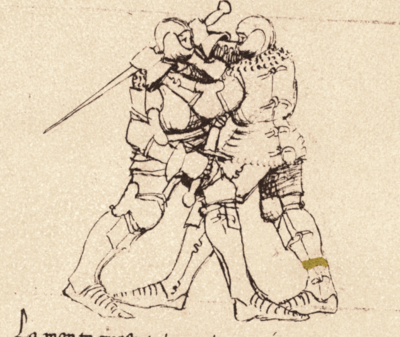

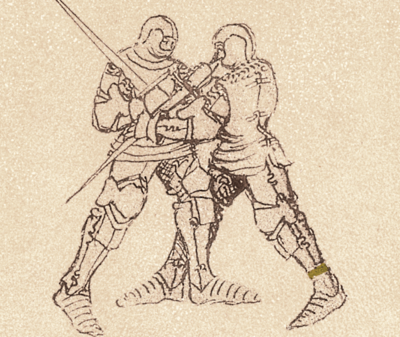

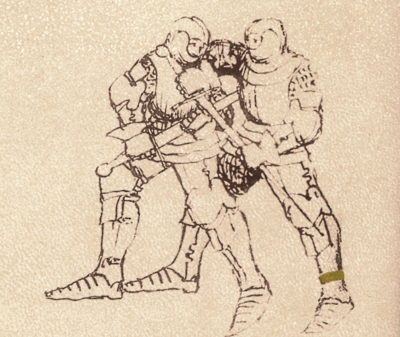

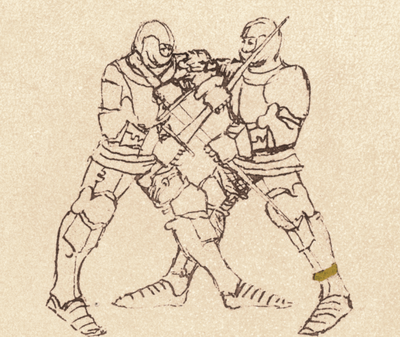

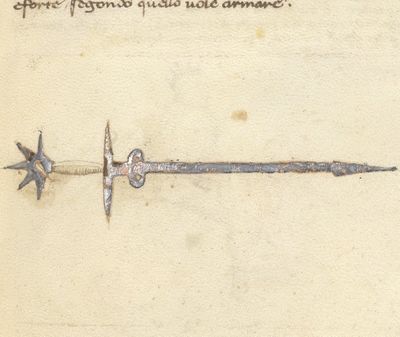

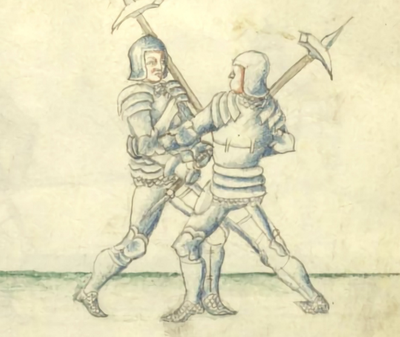

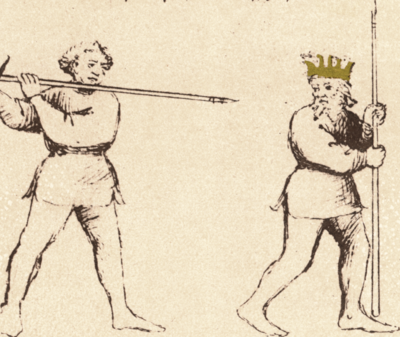

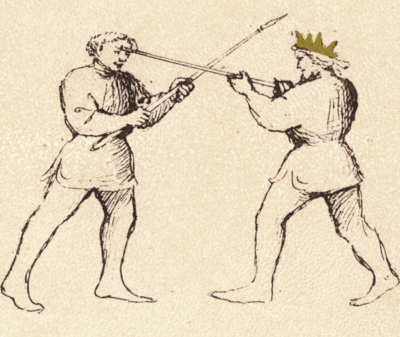

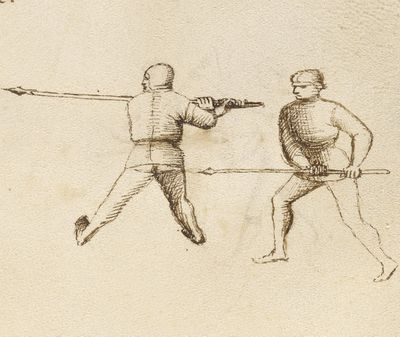

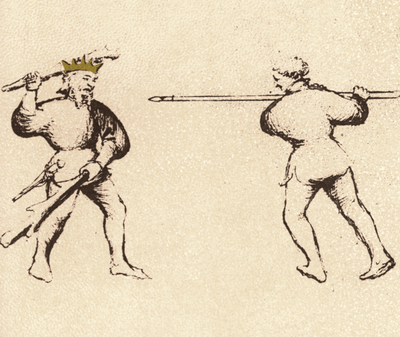

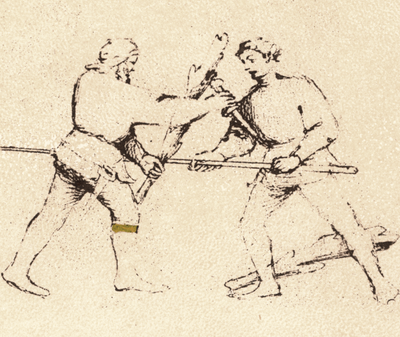

| − | The | + | The major sections of the work include: ''abrazare'' or [[grappling]]; ''[[dagger|daga]]'', including both unarmed defenses against the dagger and plays of dagger against dagger; ''spada a un mano'', the use of the [[sword]] in one hand (also called "the sword without the buckler"); ''spada a dui mani'', the use of the sword in two hands; ''spada en arme'', the use of the sword in [[armor]] (primarily techniques from the [[halfsword|shortened sword]]); ''azza'', plays of the [[poleaxe]] in armor; ''lancia'', [[spear]] and staff plays; and mounted combat (including the spear, the sword, and mounted grappling). Brief bridging sections serve to connect each of these, covering such topics as ''bastoncello'', or plays of a [[club (weapon)|small stick or baton]] against unarmed and dagger-wielding opponents; plays of sword vs. dagger; plays of staff and dagger and of two clubs and a dagger; and the use of the [[spear|chiavarina]] against a man on horseback. |

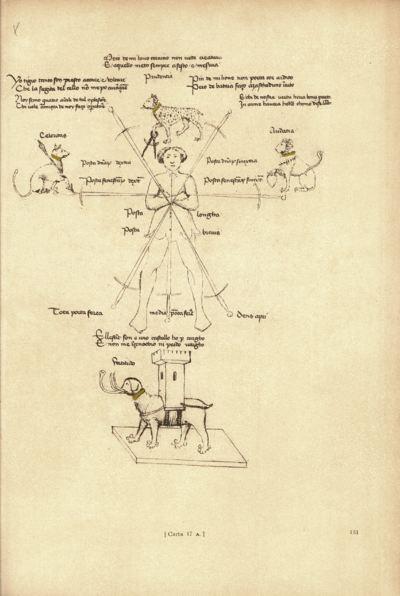

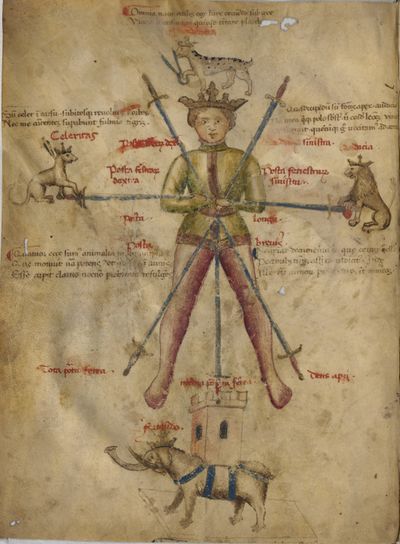

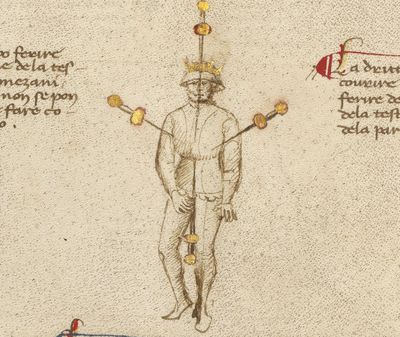

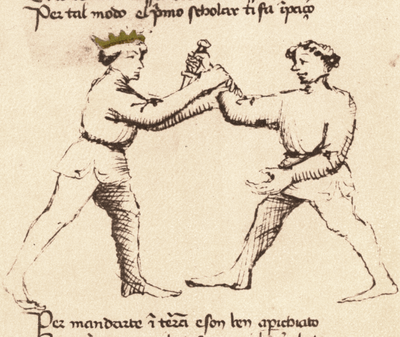

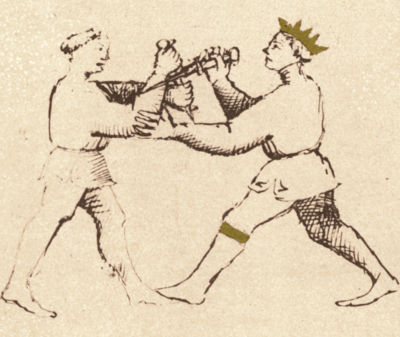

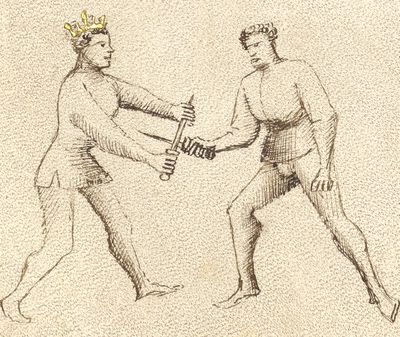

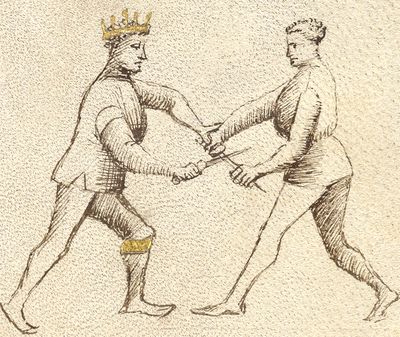

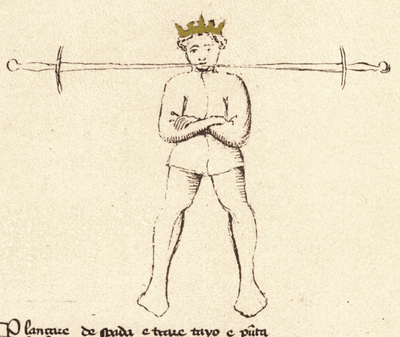

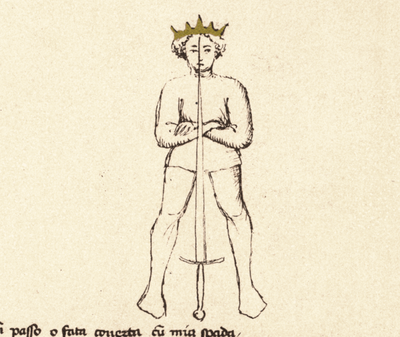

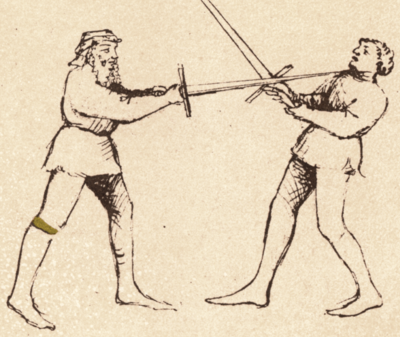

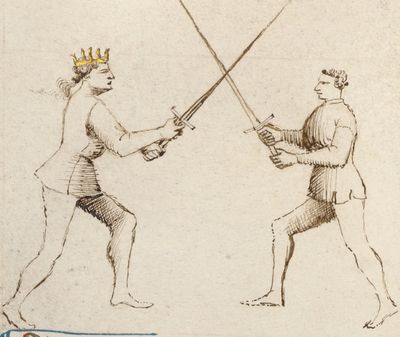

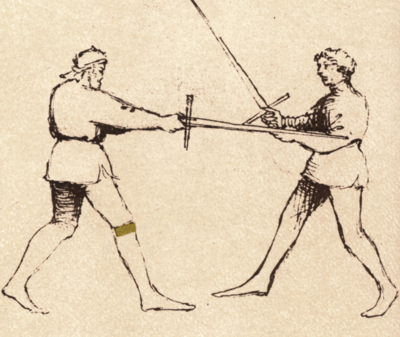

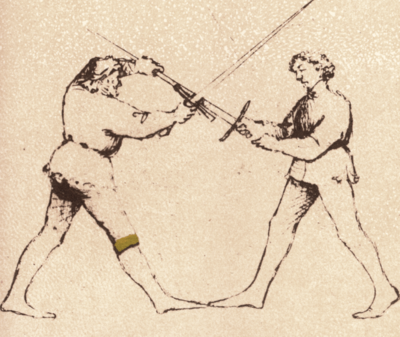

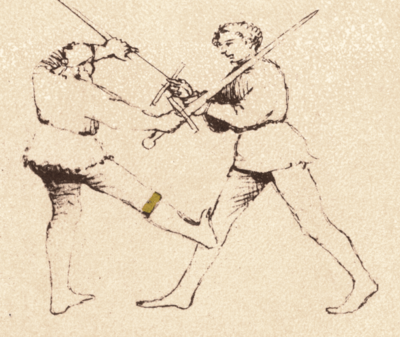

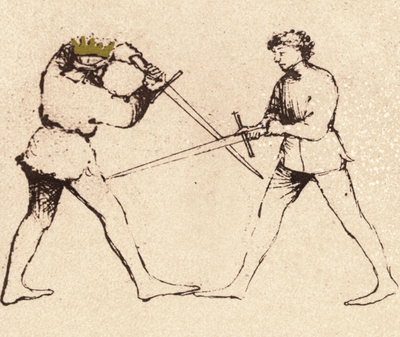

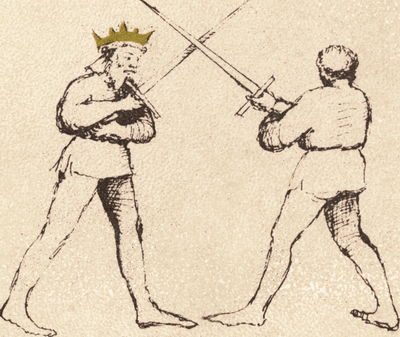

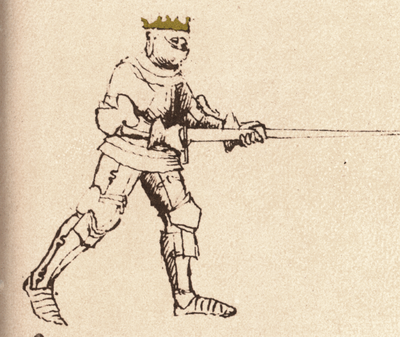

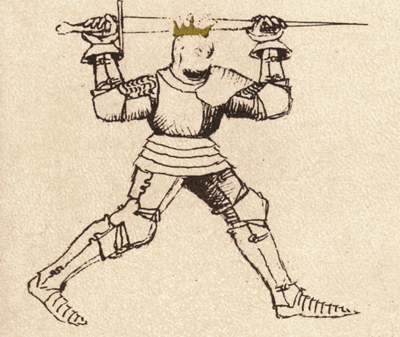

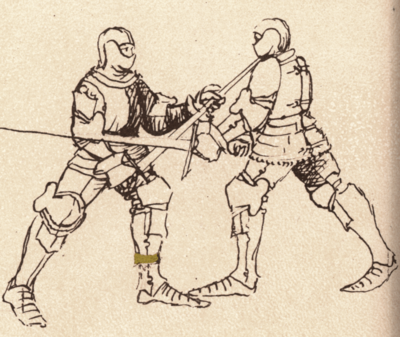

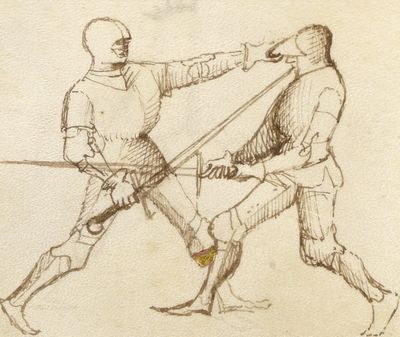

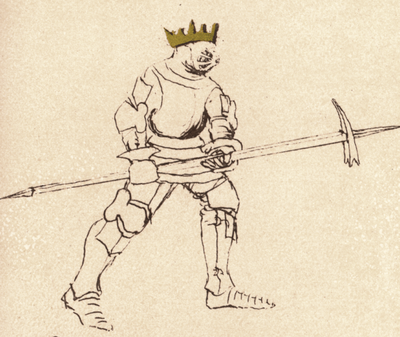

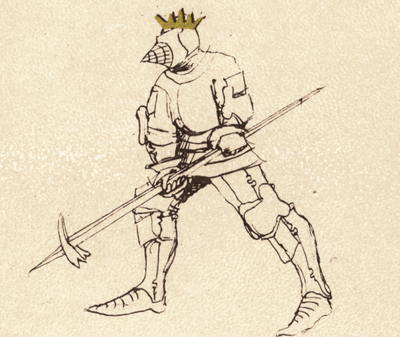

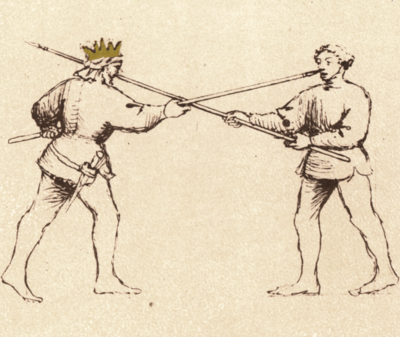

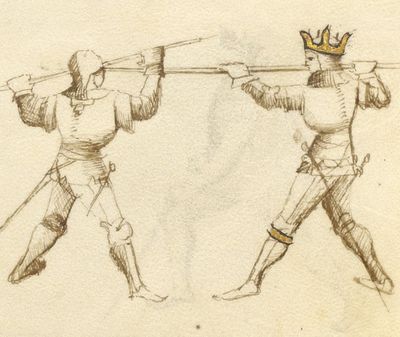

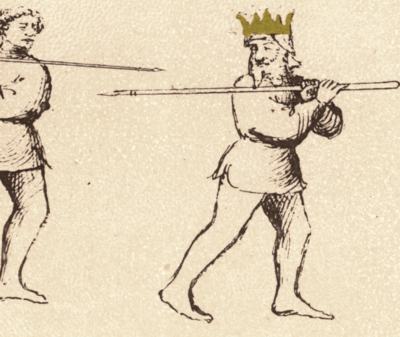

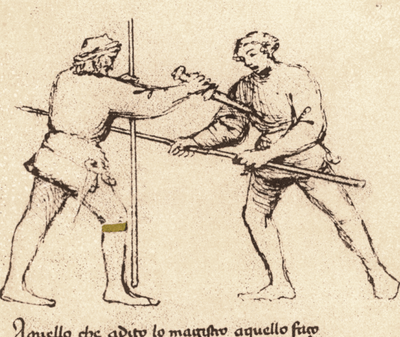

| − | The | + | The format of instruction is largely consistent across all copies of the treatise. Each section begins with a group of Masters (or Teachers), figures in golden crowns who each demonstrate a particular guard for use with their weapon. These are followed by a master called ''Remedio'' ("Remedy") who demonstrates a defensive technique against some basic attack (usually how to use one of the listed guards to defend), and then by his various Scholars (or Students), figures wearing golden garters on their legs who demonstrate iterations and variations of this remedy. After the scholars there is typically a master called ''Contrario'' ("Counter" or "Contrary"), wearing both crown and garter, who demonstrates how to counter the master’s remedy (and those of his scholars), who is likewise sometimes followed by his own scholars in garters. In rare cases, a fourth type of master appears called ''Contra-Contrario'' ("Counter-counter"), who likewise wears the crown and garter and demonstrates how to defeat the master’s counter. Some sections feature multiple master remedies or master counters, while some have only one. While the crowns and garters are used across all extant versions of the treatise, the specific implementation of the system varies; all versions include at least a few apparently errors in assignation of crowns and garters, and there are many cases in which an illustration in one manuscript will only feature a scholar’s garter where the corresponding illustration in another also includes a master’s crown (depending on the instance, this may either be intentional or merely an error in the art). Alone of the four versions, the Morgan seeks to further expand the system by coloring the metallic portions of the master or scholar’s weapon silver, while that of the player is left uncolored; this is also imperfectly-executed, but seems to have been intended as a visual indicator of which weapon belongs to which figure. |

| − | + | The concordance below includes Zeno’s transcription of the Morgan preface for reference, and then drops the (thereafter empty) column in favor of a second illustration column for the main body of the treatise. (The Zeno transcript is in the first transcription column even though it’s the youngest source so that the others can remain in the same position throughout.) Generally only the right-side column will contain illustrations—the left-side column will only contain additional content when when the text describes an illustration that spans the width of the page in the manuscripts, or when there are significant discrepancies between the available illustrations (in such cases, they sometimes display two stages of the same technique and will be placed in "chronological" order if possible). The illustrations from the Getty, Morgan, and Paris are taken from high-resolution scans supplied by those institutions, whereas the illustrations of the Pisani Dossi are taken from Novati’s 1902 facsimile (scanned by Wiktenauer). There are likewise two translation columns, with the the two manuscripts dedicated to Niccolò on the left and the two undedicated manuscripts on the right; in both columns, the short text of the PD and Paris will come first, followed by the longer paragraphs of the Getty and Morgan. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{master begin |

| − | | title | + | | title = Preface |

| − | | | + | | width = 100% |

| − | |||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{master subsection begin |

| − | + | | title = First Italian Preface | |

| − | + | | width = 240em | |

| − | |||

| − | | title | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {{ | + | {| class="master" |

| − | {{ | + | |- |

| + | ! <p>Illustrations</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|B|Completed Translation (from the Getty)}}<br/>by [[Colin Hatcher]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|B|Completed Translation (from the Morgan)}}<br/>by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>[[Fior di Battaglia (MS XXIV)|San Daniele del Friuli Version]] (1699){{edit index| Fior di Battaglia (MS XXIV)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>[[Trattato della scherma (MS M.383)|Morgan Version]] (1400s){{edit index|Trattato della scherma (MS M.383)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>[[Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)|Getty Version]] (1400s){{edit index|Fior di Battaglia (MS Ludwig XV 13)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>[[Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)|Pisani Dossi Version]] (1409){{edit index|Flos Duellatorum (Pisani Dossi MS)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>[[Florius de Arte Luctandi (MS Latin 11269)|Paris Version]] (1420s){{edit index|Florius de Arte Luctandi (MS Latin 11269)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Kendra Brown]] and [[Rebecca Garber]]</p> | ||

| − | + | |- | |

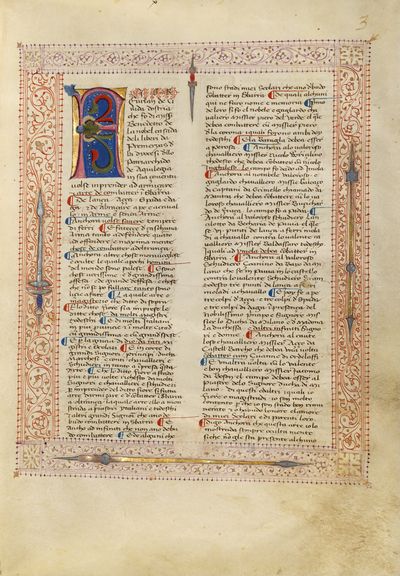

| − | + | | rowspan="4" | [[File:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|400px|center]] | |

| − | + | | <p>I, Fiore the Friulian,<ref>Fiore ''Furlan'' means “Fiore the Friulian”, i.e. “Fiore of Friuli”. Friuli is an area in the extreme north-eastern corner of Italy, to the | |

| − | + | north-east of Venice, with Austria to the north and Slovenia to the east.</ref> born in Cividale D’Austria, was the son of Sir Benedetto of the noble order | |

| − | + | of the free knights of Premariacco,<ref>Fiore the Friulian, of the free knights of Premariacco is usually referred to as Fiore dei Liberi (one translation would be “Fiore of the Free Knights”). We don’t know for sure whether “Fiore” (“Flower”) was his real name or a pen-name. “Fiore” certainly existed as a real name for a man in medieval Italy—it was a common unisex medieval Christian name derived from the Italian word for flower. Alternately “Flower of the Free Knights” also makes sense, meaning “The best of the free knights.” As to the question of whether “Liberi” is a family name or simply refers to the class of free knights, since the word is spelled in Fiore’s manuscripts, in Getty (“liberi”), Pisani-Dossi (“liberorum”) and Morgan (“liberi”), with a small “l” for “liberi”, I am translating this word not as a family name (“Liberi”) but as “free knights” (“milites liberi”).</ref> in the diocese of the Patriarchate of Aquileia.</p> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <p>As a young man I<ref>I have translated the entire Prologue into the first person “I”, rather than use the third person “Fiore”, so as to make it more friendly and direct to read.</ref> desired to learn armed fighting,<ref>“Armiçare” or “Armizare” means the art of armed fighting or fighting with weapons. Fiore refers to his martial art as both “L’Arte d’Armizare” (Art of Armed Combat) and “La Scientia d’Armizare” (Science of Armed Combat). However, you should note that the words ''Arte'' and ''Scientia'' do not necessarily have their modern meanings. ''Arte'' may mean simply “skill” and the word “''Scientia''” may mean simply “knowledge”. Thus “the skill and knowledge of armed fighting”.</ref> including the art of fighting in the lists<ref>Fiore is comparing the two kinds of fighting: sport/tournament (“combatter a sbarra”—“in the lists”) and mortal combat (“combatter adoltrança”—“to the death”). To fight “in the lists” was not however without serious risks of injury and/or death. Medieval knights took these tournaments very seriously as matters of honor, and renown was won and lost in such events. Fiore also appears to include duels of honor in his term “in sbara”. The fights he describes below include duels of honor.</ref> with spear, poleaxe, sword, dagger and unarmed grappling, on foot and on horseback, armored and unarmored.</p> | |

| − | + | | <p>Fiore Friulano de Cividale d'Austria, the son of Sir Benedetto of the noble house of the Liberi of Premariacco in the diocese of the Patriarchate of Aquileia, in his youth wanted to learn fencing and the art of combat in the barriers (that is, to the death); of lance, ax, sword, and dagger, and of wrestling, on foot and on horse, in armor and without armor.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783r.jpg|2|lbl=783r}} | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1r.jpg|1r.1|lbl=1r}} | |

| − | }} | + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.1|lbl=1r}} |

| − | {{: | + | | |

| − | {{ | + | | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | <p> In addition I wanted to study how weapons were made,<ref>“tempere di ferri” means literally “the tempering of iron”. I have translated this liberally to “the construction of weapons” to more clearly reflect what I believe Fiore means here. See also fn. 37 below.</ref> and the characteristics of each weapon for both offense and defense, particularly as they applied to mortal combat.</p> | |

| − | + | | <p>Also he wanted to know of the temper of iron, and the qualities of each weapon, as much for defense as for offense, and most of all matters of mortal combat.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783r.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | |

| − | }} | + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1r.jpg|1r.2|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{: | + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.2|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{ | + | | |

| + | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | <p>I also desired to learn the wondrous secrets of this art known only by very few men in this world.</p> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <p>And these secrets will give you mastery of attack and defense, and make you invincible, for victory comes easily to a man who has the skill and mastery described above.</p> | |

| − | + | | <p>Also other marvelous and occult things that are apparent to few men in the world, and are very true things and very great for offense and defense, and things that cannot fail you, so easy are they to do, which art and mystery is described above.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783r.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | |

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1r.jpg|1r.3|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS M.383 1r.jpg|1r.4|lbl=-|p=1}} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 | + | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.3|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.4|lbl=-|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | <p>I learned these skills from many German and Italian<ref>It is important to remember that when Fiore refers to “Germans” and “Italians” he is referring to language/cultures and not referring to nation states. Neither “Germany” nor “Italy” existed at this time.</ref> masters and their senior students, in many provinces and many cities, and at great personal cost and expense.</p> | ||

| + | | <p>And the aforesaid Fiore did learn the aforesaid things from many German masters. Also from many Italians in many provinces and in many cities, with great fatigue and with great expense, and by the grace of God from so many masters and scholars.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783r.jpg|5|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1r.jpg|1r.5|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.5|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>And by the grace of God I also acquired so much knowledge at the courts of noblemen, princes, dukes, marquises, counts, knights and squires, that increasingly I was myself asked to teach. My services were requested many times by noblemen, knights and their squires, who wanted me to teach them the art of armed combat<ref>Here is where Fiore names his martial art: “Arte d’Armizare”—“the Art of Armed Combat”.</ref> both for fighting at the barrier<ref>“in Sbarra” means literally “at the barriers”. In many medieval sporting events the combatants would fight with swords or spears over a fence (barrier). This prevented the combatants from closing to grapple and thus tested their long range fighting skills. Fiore uses this term to refer to sporting events as opposed to fights to the death. Fiore tells us he was asked to teach for both.</ref> and for mortal combat. And so I taught this art to many Italians and Germans and other noblemen who were obliged to fight at the barrier, as well as to numerous noblemen who did not actually compete.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>And below are the names and a little of the history of some of the noblemen who have been my students, and who were obliged to fight at the barrier.</p> | ||

| + | | <p>And in so many courts of great lords, princes, dukes, marquises and counts, knights, and squires did he undertake this art, that the aforesaid Fiore was more and more times retained by many lords and knights and squires for learning from the aforesaid Fiore to do the art of fencing and of combat in the barriers to the bitter end, which art he demonstrated to many Italians and Germans and other great lords that were obliged to combat in the barriers (and also to countless that were not obliged to combat). And of some that have been my scholars that have been obliged to combat in the barriers, of these I wish to name and make here a remembrance.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783r.jpg|6|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783v.jpg|1|lbl=783v|p=1}} | |

| − | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 | + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1r.jpg|1r.6|lbl=-}} |

| + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.6|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 169: | Line 186: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>The first of them was the noble and gallant knight Piero del Verde<ref>Piero del Verde (Getty), Piero dal Verde (Morgan), (lit. “Peter of the Green”), also named elsewhere as Paolo del Verde, Pietro del Verde and Pietro von Grünen, was a recorded German condottiero (mercenary) captain who died in 1384. His birth date is not known.</ref> who fought Piero della Corona.<ref>Piero della Corona (Getty), Piero dalla Corona (Morgan) (lit “Peter of the Crown”), also named elsewhere as Pietro della Corona, Peter Kornwald, Pietro Cornuald, was another recorded German ''condottiero'' (mercenary) captain who died in 1391. His birth date is not known.</ref> Both were German, and the fight took place in Perosa.<ref>Perosa/Perusia is now known as Perugia. It is situated about 100 miles north of Rome. The date of this duel is estimated between 1379 and 1381, when both knights are recorded as present in this region.</ref></p> |

| − | | | + | | <p>And the first notable and gallant knight is Sir Peter von Grünen, who was obliged to combat with Sir Peter Kornwald (who were both Germans). And the battle was required to be at Perugia.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1r.jpg|1r.7|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.7|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| − | + | |- | |

| | | | ||

| + | | <p> Next was the brave knight Niccolo Voriçilino,<ref>Nicolo Voriçilino (Getty), Nicholo Vnriçilino (Morgan), is named elsewhere variously as Niccolo Voricilino, Niccolo Borialino, Niccolo Waizilino, Nikolaus Weiss , and Nicholas von Urslingen. There is no historical record, however, as to who this person was.</ref> also a German, who was obliged to fight Niccolo Inghileso.<ref>Niccolo “Inghileso” (Getty and Morgan) translates as Nicholas “the Englishman”. However, there is no historical record as to | ||

| + | who this person was.</ref> The field of battle for this fight was Imola.<ref name="Imola">The city of Imola is about 120 miles south-west of Venice.</ref></p> | ||

| + | | <p>Also the valiant knight Sir Nikolo [illegible] (the German), who was obliged to combat with Nicolo (the English), and the field was given at Imola.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1r.jpg|1r.8|lbl=-}} |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.8|lbl=-}} | |

| − | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 183: | Line 207: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>Next was the well-known, valiant and gallant knight Galeazzo de Capitani da Grimello, known as da Mantova,<ref>Galeazzo de Capitani da Grimello da Mantova (Getty), Galeaz delli capitani de Grimello chiamado da Montoa (Morgan), also named Galeazzo de Mantova (eng. Mantua), Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli, and Galeazzo Gonzaga, was an Italian condottiero captain who died in 1406. We do not know his birth. | |

| − | | <p> | ||

| − | < | + | Significantly Galeazzo fought two duels against Buzichardo de Fraza, also known as Boucicault, one in 1395 that was stopped by the supervising Lord where the parties were evenly matched, and one in 1406, where Galeazzo defeated Boucicault. To be able to say that one of his students defeated the mighty Boucicault in single combat would have looked very impressive on Fiore’s resume.</ref> who was obliged to fight the valiant knight Buçichardo de Fraca.<ref>Buçichardo de Fraca (Getty), Briçichardo de Franza (Morgan), named elsewhere as Buzichardo de Fraza, also known as Boucicault, or Jean Ⅱ Le Maingre (1364-1421), was a French military general who was honored by King Charles VI as Marshall of France in 1391, and was a knight of great renown for his military skill, and his strength and athleticism in single combat. Apparently at a dinner at which both Boucicault and Galeazzo were present, Boucicault insulted Italians claiming he could beat any Italian knight in single combat. Galeazzo accepted the challenge, and the two fought with spears on foot in 1395, a duel that was a draw, when it was halted by the supervising lord, Francesco Gonzaga, Lord of Mantova. The enmity was not forgotten however, and the two repeated their duel in 1406, this time on horseback with lances, at which time Boucicault was defeated by Galeazzo.</ref> The field of battle for this fight was Padova.<ref>Padova (Padua) is about 20 miles west of Venice.</ref></p> |

| + | | <p>Also the notable, valiant, and gallant knight Sir Galeazzo Cattaneo dei Grumelli, called da Mantua, who was obliged to combat with the valiant knight Sir Boucicault (Jean Ⅱ le Maingre) of France, and the field was at Padua.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783v.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1r.jpg|1r.9|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.9|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | < | + | | <p>Next was the valiant squire<ref>A squire was a nobleman who was trained and skilled in the knightly arts, but who had not yet been knighted. Note the fighting abilities of the squire were not necessarily any different from the knight proper.</ref> Lancillotto da Becharia de Pavia,<ref>Lancillotto da Becharia de Pavia (Getty), Lanzilotto de Boecharia da Pavia (Morgan), also called Lancilotto Beccaria was an Italian condottiero captain who died in 1418. We do not know his birthdate.</ref> who exchanged six strikes with a sharpened steel lance<ref>Notice that although these are “sporting events” they were using real spears.</ref> against the valiant German knight Baldassarro,<ref>Baldassarro (Getty), Baldesar (Morgan) refers to the German knight Balthasar von Braunschweig-Grubenhagen (1336-1385)</ref> in a fight that took place in the lists at Imola.<ref name="Imola"/></p> |

| − | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 | + | | <p>Also the valiant squire Lancillotto Beccaria of Pavia. That was 6 thrusts of ground-iron lance<ref name="moladi">''Ferri moladi'' is an ambiguous term: ''molare'' means "to grind with a stone", but it's unclear whether this means the lance was sharp or blunt since both processes would involve a stone. However, another period account of Sirano's duel specifies that it was with ''lancee acute'' or sharp lances, so that's probably the grinding that Fiore meant.</ref> on horseback against the valiant knight Sir Balthasar von Braunschweig-Grubenhagen (a German), and also obliged to combat in the list, and this was at Imola.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783v.jpg|4|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.1|lbl=1v}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.10|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 197: | Line 229: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>Next was the valiant squire Gioanino da Bavo,<ref>Gioanino de Bavo (Getty), Zohanni de Baio (Morgan), also named Giovannino da Baio likely refers to the French knight Jean de Bayeux, who is recorded as being in the area at this time.</ref> from Milan, who, in the castle in Pavia,<ref>The city of Pavia is 20 miles south of Milan.</ref> fought three passes with a sharpened steel lance, against the valiant German squire Sram.<ref>The identity of the German squire named Sram (Getty and Morgan), Schraam, or Schramm, is not known.</ref> And then on foot he fought three passes with the axe, three with the sword and three with the dagger, in the presence of the very noble prince and lord the Duke of Milan, and his lady the Duchess, and numerous other lords and ladies.</p> |

| − | | <p> | + | | <p>Also the valiant squire Giovannino da Baggio of Milan, who in the castle in Pavia, with the valiant squire Sirano (the German), struck three thrusts of ground-iron lance<ref name="moladi"/> on horseback. And then on foot he made three blows of axe, and three blows of sword, and three blows of dagger, in the presence of the most noble lord Duke of Milan, and of the lady Duchess, and of countless other lords and lady.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783v.jpg|5|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.2|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.11|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| − | + | |- | |

| − | | | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Next was the cautious knight Sir Açço da Castell Barcho,<ref>Açço da Castell Barcho (Getty), Azo da Castelbarcho (Morgan), refers to Azzone Francesco di Castelbarco, an Italian condottiero captain who died in 1410. We do not know his birthdate.</ref> who was obliged to fight one pass against Çuanne di Ordelaffi,<ref>Çuanne di Ordelaffi (Getty), Zohanni di li Ordelaffig (Morgan) refers to Giovanni Ordelaffi, an Italian condottiero captain (1355-1399).</ref> and another pass against the valiant and good knight Sir Jacomo di Boson,<ref>Jacomo di Boson (Getty), Jacomo de Besen (Morgan), or Giacomo da Boson, likely refers to the German nobleman Jakob von Bozen.</ref> the location chosen by his eminence the Duke of Milan.</p> | ||

| + | | <p>Also the cautious knight Sir Azzone di Castelbarco, who once was obliged to combat with Sir Giovanni di Ordelaffi. And another time with the valiant and virtuous knight Sir Giacomo da Boson, and the field was set at the pleasure of the lord Duke of Milan.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783v.jpg|6|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783ar.jpg|1|lbl=783ar|p=1}} | |

| − | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 | + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.3|lbl=-}} |

| + | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.12|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 211: | Line 250: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>Of these and of others whom I, Fiore, have taught, I am very proud, because I have been well rewarded, plus I earned the respect and the affection of my students and also of their relatives.</p> |

| − | + | ||

| + | <p>Also, I should tell you that I always taught this art secretly, and so no one was present at my lessons except for the student and occasionally a close relative of his, and if anyone else was there by my grace or favor, they were only allowed to watch after swearing a sacred oath of secrecy, swearing by their faith not to reveal any of the techniques they saw me, Master Fiore, demonstrate.</p> | ||

| + | | <p>These and others have I, Fiore, taught, and I am very content because I have been well-remunerated and I have had the honor and the love of my scholars and of their relatives.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>Also I say that to whom I have taught this art, I have taught secretly, that there was no person other than the scholar and some close relative of his. Also that those who were present had sworn with sacrament that they would not reveal any play that they had seen from me, Fiore.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783ar.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.4|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 01r.jpg|1r.13|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.1|lbl=1v|p=1}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | < | + | | <p>More than anyone else I was careful around other Masters of Arms and their students. And some of these Masters who were envious of me challenged me to fight<ref>These were duels of honor, and were taken very seriously in these times.</ref> with sharp edged and pointed swords<ref>Fiore actually says that the swords are “di taglo e di punta” meaning literally “for cutting and thrusting”, or “sharp edged and |

| − | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 | + | pointed”.</ref> wearing only a padded jacket,<ref>A “çuparello darmare” or “zuparello d’armare” is an arming jacket, that is, a cloth padded jacket worn underneath armour as a foundation garment.</ref> and without any other armor except for a pair of leather gloves; and this happened because I refused to practice with them or teach them anything of my art.</p> |

| + | | <p>And most of all have I been wary of fencing masters and of their scholars. And they (that is, the masters), out of envy, challenged me to play at swords of sharpened edge and point, in arming jacket but without any other armor save for a pair of chamois gloves, and all of this was because I did not wish to practice with them, nor did I wish to teach them anything of my art.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783ar.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.5|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.2|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | | | + | | <p>And I was obliged to fight five times in this way. And five times, for my honor, I had to fight in unfamiliar places without relatives and without friends to support me, not trusting anyone but God, my art, myself, and my sword. And by the grace of God, I acquitted myself honorably and without injury to myself.<ref>We don’t know if this means he won all five duels, or simply acquitted himself well. But he says he was not |

| − | + | injured.</ref></p> | |

| − | | | + | | <p>And this incident, that I was so required, occurred 5 times. And 5 times, for my honor, I convened to play in strange places, without relatives and without friends, having no hope in anything other than in God, in the art, and in me, Fiore, and in my sword. And by the grace of God, I, Fiore, remained with honor and without lesions in my person.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783ar.jpg|4|lbl=-}} |

| − | | {{section|Page: | + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.6|lbl=-}} |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.3|lbl=-}} | |

| − | + | | | |

| + | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| − | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 | + | | <p>I tell my students who have to fight at the barrier that fighting at the barrier is significantly less dangerous than fighting with live swords wearing only padded jackets, because when you fight with sharp swords, if you fail to cover one single strike you will likely die.</p> |

| + | | <p>Also I, Fiore, said to my students that were obliged to combat in the barriers that combat in the barriers is a far lesser peril than combat with sword of sharp edge and point in arming jackets. Because for him that plays at sharp swords, on a single cover that fails, that blow gives him death.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.7|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.4|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| − | + | | <p>On the other hand, if you fight at the barrier and are well armored, you can take a lot of hits, but you can still win the fight. And here is another fact: at the barrier it is rare that anyone dies from being hit. So as far as I am concerned, and as I explained above, I would rather fight three times at the barrier than one time in a duel with sharp swords.</p> | |

| + | | <p>And one that combats in the barriers and is well-armored, he can receive several such strikes and can still win the battle.</p> | ||

| − | + | <p>Also, there is another thing: that only on rare occasions does someone perish because of grabs and holds. Thus I say that I would sooner combat three times in the barriers than just one time with sharp swords, as I said above.</p> | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 | + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.8|lbl=-}} |

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.5|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| − | + | | <p>Now I should add that a man may fight at the barrier well armored, with a knowledge of the art of combat,<ref>In addition to “L’Arte d’Armizare” (the art of armed fighting), L’Arte del Combattere (the art of combat) is a second name Fiore gives to his art.</ref> and may have all the advantages possible to have, but if he lacks courage he may as well just go ahead and hang himself. Having said that, I can say that by the grace of God none of my students have ever lost at the barrier. On the contrary, they have always acquitted themselves honorably.<ref>If they never lost and always acquitted themselves honorably, then presumably they always either won or drew.</ref></p> | |

| − | + | | <p>And I say that a man being well-armored for combat in the barriers, and knowing the art of combat, and having all the advantages that he can take, if he is not valiant then he will wish to hang himself. Well can I say that, for the grace of God, none of my scholars in this art have been lost—that always they remained with honor is this art.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS XXIV 783ar.jpg|5|lbl=-}} | |

| − | | <p> | + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.9|lbl=-}} |

| − | | {{section|Page:MS Ludwig XV 13 | + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.6|lbl=-}} |

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>I should also point out that the noble knights and squires to whom I showed my art of combat have been very satisfied with my teaching, and have never wanted any other instructor but me.</p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | <p>Also I say that I predict that these lords, knights, and squires to whom I have demonstrated this art of combat are content with my teachings, and did not wish any other master than the aforesaid Fiore.</p> |

| − | + | | | |

| − | <p> | ||

| | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:MS M.383 1v.jpg|1v.10|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS M.383 2r.jpg|2r.1|lbl=2r|p=1}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.7|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>In addition let me just say that none of my students, including those mentioned above, have ever owned a book about the art of combat, except for Galeazzo da Mantova. And he put it well when he said that without books you cannot be either a good teacher or a good student of this art. And I can confirm it to be true, that this art is so vast that there is no one in the world with a memory large enough to be able to retain even a quarter of it. And it should also be pointed out that a man who knows no more than a quarter of the art has no right to call himself a Master.</p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | <p>Also I say that none of these scholars here named had any book about the art of combat other than Sir Galeazzo di Mantua. Well did he say that without books no one will ever be a good master nor scholar in this art. And I, Fiore, confirm it: this art is so long that there is no man in the world with such a great memory that he can hold in mind, without books, even a fourth part of this art. And I grant that not knowing more than the fourth part of this art, I would not be a master.</p> |

| − | |||

| − | <p>I | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 2r.jpg|2r.2|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.8|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>Now I, Fiore, although I can read and write and draw, and although I have books about this art, and have studied it for 40 years and more, do not myself claim to be a perfect Master in this art, (although I am considered so by some of the fine noblemen who have been my students). But I will say this: if, instead of studying the Art of Armed Combat for 40 years, I had spent 40 years studying law, papal decrees,<ref>The word is decretali (Decretals). A Decretal is a Papal Constitution in letter form, i.e., a written decree from a Pope stating the Church’s legal position on a specific legal or moral issue.</ref> and medicine, then I would be ranked a Doctor in all three of these disciplines. And you should also know that in order to study the science of arms<ref>''Scientia d’Armizare'' is Fiore’s other term for his ''Arte d’Armizare''. ''Scientia'' means science or knowledge. Thus ''Scientia d’Armizare'' could translate as “Knowledge of Armed Combat” or “Science of Armed Combat.”</ref> I have endured great hardship, expended great effort and incurred great expense, all so as to be a perfect student of this art.</p> |

| − | + | | <p>Thus I, Fiore, knowing how to read and to write and to draw, and having books on this art, and having studied it for 40 years and more, yet I am not a very perfect master in this art. (Though I am well-held, by the great lords that have been my students, to be a good and perfect master in this art.) And I do say that if I had studied 40 years in civil law, in canon law, and in medicine, as I have studied in the art of fencing, then I would be a doctor in those three sciences. But in this science of fencing I have had great contentions and strain and expenses just to be a good scholar (as we said of others).</p> | |

| − | |||

| − | <p>I am the | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 2r.jpg|2r.3|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.9|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>It’s my opinion that in this art there are few men in the world who can really call themselves Masters, and it is my goal to be remembered as one of them. To that end I have created this book all about this martial art and the things related to it, including weapons, their applications,<ref>Fiore writes ''di ferri e di tempere'' which literally means “of iron and of tempering”, i.e., hardening of steel. However, since Fiore’s manuscript clearly does not show anything about blacksmithing or how weapons are actually made, this literal translation does not serve me. Thus I changed it to “weapons and their applications”.</ref> and other aspects too.</p> |

| − | |||

| − | <p> | + | <p>In doing this I have followed the instructions given to me by the nobleman I respect the most, who is greater in martial virtue than any other I know, and who is more deserving of my book because of his nobility than any other nobleman I could ever meet, namely, the illustrious and most excellent noble, the all-powerful prince, Sir NICCOLO, Marquis of Este, Lord of the noble cities of Ferrara, Modena, Reggio, Parma and others, and to whom may God grant long life and future prosperity, and victory over all of his enemies. AMEN.</p> |

| + | | <p>Considering, as I said before, that in this art I could find few masters in the world, and wishing that there be made a memory of me in this art, I will put all the art (and all things that I know of iron and of temper and of other things) in a book, following that which we know how to do for the best and for the most clarity.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS M.383 2r.jpg|2r.4|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.10|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>I am going to lay out this book according to the preferences of my lord Marquis, and since I will be careful to leave nothing out, I am sure that my lord will appreciate it, due to his great nobility and courtesy.<ref>It is not clear here whether Fiore is saying he actually consulted with Niccolo Ⅲ of Este prior to the creation of the book, that Niccolo indicated how he wants the book laid out, and that Fiore has decided to lay it out exactly as Niccolo has asked for it to be done, or simply that he knows what Niccolo likes.</ref></p> | |

| − | | <p | + | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.11|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>I will begin with grappling,<ref>I translate ''Abrazare'' or ''Abracare'' as “grappling” rather than “wrestling”, since wrestling suggests ground-fighting, and there is no ground fighting in Fiore’s system.</ref> of which there are two types: grappling for fun,<ref>The word ''solaço'' means “pleasure”. Fiore means grappling for sport. Fiore is distinguishing between fighting for fun and fighting to the death.</ref> or grappling in earnest,<ref>The expression ''da ira'' means “in anger”. Fiore is contrasting this with grappling for fun. Thus I have translated ''ira'' as “earnest”.</ref> by which I mean mortal combat, where you need to employ all the cunning, deceit<ref>Both ''ingano'' and ''falsita'' mean “deceit”. It is not clear why Fiore uses both, but any difference in these two words are lost in translation. I therefore translated ''ingano'' as “cunning” so that there were still three words as in the original.</ref> and viciousness<ref>The word ''crudelita'' means “cruelty”. I prefer the word “viciousness” here.</ref> you can muster. My focus is on mortal combat, and on showing you step by step how to gain and defend against the most common holds when you are fighting for your life.</p> | |

| − | | <p>''' | + | | |

| − | |||

| − | < | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.12|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>If you wish to grapple you should first assess whether your opponent is stronger or bigger than you, as well as whether he is much younger or older than you. You should also note whether he takes up any formal grappling guards<ref>The taking of guards would suggest he has some training and thus some skill in grappling.</ref> Make sure you consider these things first.</p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.13|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>And whether you are stronger or weaker than your opponent, be sure in either case that you know how to use the grapples and binds<ref>The words are ''prese'' (“holds”, “grips” or grapples”) and ''ligadure'' (“locks” or “binds”).</ref> against him, and how to defend yourself from the grapples your opponent attacks you with.</p> | |

| − | | <p>''' | + | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.14|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>If your opponent is not wearing armor, be sure to strike him in the most vulnerable and dangerous places, for example the eyes, the nose, the larynx,<ref>''inle femine sottol mento'' means literally “in the soft part below the chin”. Fiore means the throat/larynx.</ref> or the flanks.<ref>The ''fianchi'', the “flanks”, are the unprotected (“soft”) areas of the side of the torso, below the lower ribs but above the hips.</ref> And whether fighting in or out of armor, be sure that you employ grapples and binds that flow naturally together.</p> | |

| − | | <p>'' | + | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.15|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>In addition, to be a good grappler you need eight attributes,<ref>''ⅷ chose'' means literally “eight things”.</ref> as follows: [1] strength, [2] speed, [3] knowledge, by which I mean [3] knowing superior holds; [4] Knowing how to break apart arms and legs; [5] Knowing locks, that is how to bind the arms of a man in such a way as to render him powerless to defend himself and unable to escape; [6] Knowing how to strike to the most vulnerable points; [7] Knowing how to throw someone to the ground without danger to yourself. And finally [8] Knowing how to dislocate arms and legs in various ways.<ref>Note: attributes numbers 4 and 8 seem to be the same attribute. This is noted especially because in the earlier Pisani Dossi manuscript Fiore tells us there are {{dec|u|seven}} attributes (not eight as here in the Getty). ''Roture'' (“breaking”), ''Romper'' (“tearing apart”) and ''Dislogar'' (“dislocating”) arms and legs appear here to be duplicative.</ref></p> | |

| − | | <p>'' | ||

| − | <p>I | + | <p>As required, I will address all of these things step by step through the text and the drawings in this book.</p> |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 01v - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|1v.16|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.1|lbl=2r|p=1}} |

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 426: | Line 425: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>Now that I have discussed some general rules for grappling, I will discuss the grappling guards. There are a variety of grappling guards, some better than others. But there are four guards that are the best whether in or out of armor, although I advise you not to wait in them for too long, due to the rapid changes that take place when you are grappling.</p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page: | + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.2|lbl=-}} |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 436: | Line 435: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>The first four Masters that you will see with crowns on their heads will show you these four superior grappling guards. The first two are named “The Long Guard” and “The Boar’s Tooth” and they can be used to counter each other. The second two are named “Iron Gate” and “The Forehead Guard”,<ref>''Frontale'' means the front of the head, i.e., the forehead. Elsewhere Fiore comments that this guard is often named (by others) as ''Posta Corona'' (“The Crown Guard”), the “crown” referring to the top of the head.</ref> and they can also be used to counter each other. From these four guards, whether in or out of armor, you can do all of the eight things I listed earlier, namely holds, binds, dislocations, etc.</p> |

| − | |||

| − | <p>'' | + | <p>You will need to learn the guards of the Masters, how to distinguish the Students from the Players and the Players from the Masters, and finally the difference between the Remedy and the Counter. While a Counter will usually be presented after<ref>''Dredo'' means “Behind” but in this context it translates better as “after”, be cause we can see from the way the manuscript is laid out that the remedies are shown first, and the counters later.</ref> the Remedies are shown, sometimes there will be a special “Remedy”<ref>The “Special” Remedy that comes at the very end, that Fiore is referring to is a Counter to the Counter, which, as you will see below, Fiore calls ''Contra-contrario'' or the “Counter-counter”.</ref> that comes last of all. But let me make this clearer for you.</p> |

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.3|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | |

| − | + | | <p>The four guards or “posts” are easy to learn. Sometimes you’ll take a guard and face your opponent without making contact, waiting to see what your opponent will do. These are called the posts or guards of the first Masters of Battle.<ref>Literally “Masters of the Battle” or “Masters of the Fight”.</ref> And these masters wear a golden crown on their head, to signify that the guards they wait in provide them with a superior defense. And these four guards are best suited to apply the principles of my art of armed fighting, which is why these Masters choose to wait in these particular guards.</p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.4|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>Whether you call it a “post” or a “guard”, you are referring to the same stance. As a “guard” it is used defensively, that is you use it to protect yourself and defend yourself from the strikes of your opponent. As a “post” it is used offensively, that is, you use it to position yourself in such a way in relation to your opponent that you can attack him without danger to yourself.</p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.5|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>The next Master who follows the four guards comes to respond to these guards and to defend himself against a Player who makes attacks that flow from the four beginning guards shown earlier. And this Master also wears a crown, but he is named the Second Master of Battle.<ref>Fiore just calls him the “Second Master”, but Fiore means by this that he is the Second Master of Battle.</ref> He is also known as the Remedy Master, because he carefully selects his response to attacks flowing from the posts referred to above, and makes remedies that prevent him from getting struck.</p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.6|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>This second or Remedy Master has a group of Students<ref>Fiore here calls them ''Zugadori'' (Players) rather than ''Scolari'' (Students), but that is confusing, because the way the manuscript is visually structured, the students of the Remedy Master who wear the golden garter are named ''Scolari'' (Students), not ''Zugadori'' (Players). The ''Zugadori'' are drawn without any garter at all. Therefore here I translate ''zugadori'' as Students (''Scolari''), so as to be consistent with what is drawn.</ref> under him, who demonstrate the plays taught by the Remedy Master that follow the cover or grapple that he shows first as his remedy. And these Students wear a garter<ref>''Divisa'' means literally “device” but also refers to a uniform or insignia that marks a person's rank or position. I have chosen to translate the word ''divisa'' as “garter”. In the PD, Fiore refers to the golden ribbon worn around one leg by the Students as a ''lista doro''. A ''lista'' is a strip of material, like a ribbon, garter or scarf. ''Doro'' means ''D’oro'' - “of gold.”</ref> under their knee, to identify themselves. These Students will demonstrate all the remedies of the Remedy Master, until a third Master of Battle appears, who will show the Counters to the Remedy Master and his Students.</p> | |

| − | | <p>''' | + | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.7|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>And because he can defeat the Remedy Master and his students, this Third Master wears both the symbol of the Remedy Master—a golden crown, and the symbol of his students—a golden garter below the knee. And this King is named the Third Master of Battle, and he is also named the Counter Master, because he makes counters to the Remedy Master and his students.<ref>Fiore actually writes “The Remedy Master and his plays, but since the Counter Master also defects the Remedy Master’s students, who show all the plays, I decided to translate it as above.</ref></p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.8|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Finally let me tell you that in a few sections of this Art we will find a Fourth Master (or King) who can defeat the Third Master of Battle (the Counter to the Remedy). And this King, the Fourth Master, is named the Fourth Master of Battle. He is also known as the Counter-Counter Master. Be aware however that in this Art few plays will ever go past the Third Master of Battle, for to do so is very risky. But enough about this.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.9|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>As I have explained above, the guards of the Abrazare (shown by the First Master of Battle), the Second Master of Battle (the Remedy Master) and his Students, the Third Master of Battle (the Counter Remedy, that is the counter to the Second Master of Battle and his Students), and the Fourth Master of Battle (named the Counter-counter Master), represent the foundation of my Art of Grappling whether in and out of armor. Furthermore, these four Masters of Battle and their Students are also the foundation of the Art of the Spear, which has its own guards, Masters and Students. The same is true for the Art of the Pole-axe, the Sword in One Hand, the Sword in Two Hands and the Dagger.</p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.10|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p> In summary, these Masters of Battle and their Students, identified by their various devices, although first presented as governing principles of my Art of Grappling, are actually the foundation of my entire Art of Armed Fighting, whether on foot or on horseback, and whether in or out of armor.<ref>I’ve rearranged the sentences here to make my translation clearer. Thus the red and blue letters in the original don’t match up at all in my translation.</ref></p> | |

| − | | <p> | + | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Getty Ms. Ludwig XV 13 02r - Fiore dei Liberi - Decorated Text Page - Google Art Project.jpg|2r.11|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||