|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Gloss"

| (12 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

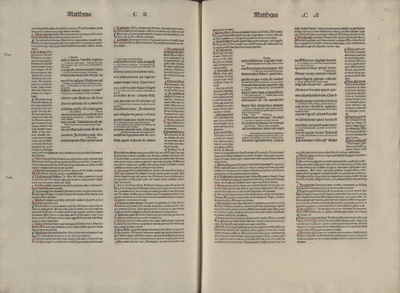

| − | [[file:Biblical gloss.png|400px|right|thumb|A Bible | + | [[file:Biblical gloss.png|400px|right|thumb|A Bible created in 1481 including the ''glossa ordinaria'']] |

| − | A '''gloss''' is an explanation of a piece of text. It can range from a simple translation for a word in a foreign language to an extensive commentary on a | + | A '''gloss''' is an explanation of a piece of text. It can range from a simple translation for a word in a foreign language to an extensive commentary on a longer passage. In the Medieval period, glosses would typically be written in between the lines of text (if they were short) or in the margins of manuscripts (if they were longer). The process of writing interpretations of existing texts is known as '''glossing'''. |

Glossing authoritative texts was a common practice in the Scholastic movement of the Middle Ages, and by the 12th century, comprehensive glosses for the entire Bible and many important Roman legal texts had been assembled from the writings of experts of centuries past. These were called ''glossae ordinariae'' ("standard glosses") and included both interlinear and marginal commentaries, typically dwarfing the actual text being discussed. The Jewish practice of recording ''Midrashim'' in the margins of the ''Tanakh'' is a parallel tradition that arose in this same period. | Glossing authoritative texts was a common practice in the Scholastic movement of the Middle Ages, and by the 12th century, comprehensive glosses for the entire Bible and many important Roman legal texts had been assembled from the writings of experts of centuries past. These were called ''glossae ordinariae'' ("standard glosses") and included both interlinear and marginal commentaries, typically dwarfing the actual text being discussed. The Jewish practice of recording ''Midrashim'' in the margins of the ''Tanakh'' is a parallel tradition that arose in this same period. | ||

| − | By the 14th century, the tradition of creating formal glosses of authoritative texts had faded away in Scholastic circles, and they were more likely to author entirely new treatises which merely referenced older authorities. However, the more famous glosses continued to be commonly reproduced and sold | + | By the 14th century, the tradition of creating formal glosses of authoritative texts had faded away in Scholastic circles, and they were more likely to author entirely new treatises which merely referenced older authorities. However for centuries thereafter, the more famous glosses continued to be commonly reproduced and sold as reference books—the ''glossa ordinaria'' of the Bible was even among the first books to be printed after the invention of moveable type. And the practice of recording one's personal thoughts in the margins of books, of course, continues until the present day. |

| − | When the Liechtenauer tradition arose in the 15th century, many of | + | When the Liechtenauer tradition arose in the 15th century, many of its early authors chose to treat his [[Recital]] as an authoritative text and fashion glosses to explain their interpretations of it in the manner of earlier generations of Medieval scholars. |

__TOC__ | __TOC__ | ||

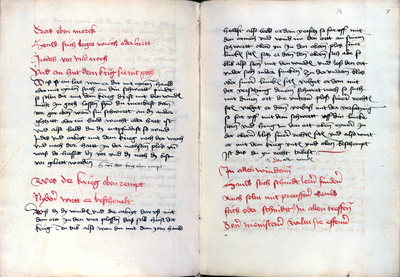

[[file:Codex Speyer gloss.png|400px|right|thumb|The Recital (red text) and Lew gloss (black text) from 1491]] | [[file:Codex Speyer gloss.png|400px|right|thumb|The Recital (red text) and Lew gloss (black text) from 1491]] | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

=== Major Glosses === | === Major Glosses === | ||

| − | The major glosses are equivalent to the ''glossa ordinaria'' discussed above: they include commentary on the entirety of one or more sections of the Recital. The major glosses are associated with two members of the [[ | + | The major glosses are equivalent to the ''glossa ordinaria'' discussed above: they include commentary on the entirety of one or more sections of the Recital. The major glosses are associated with two members of the [[Fellowship of Liechtenauer]], [[Peter von Danzig zum Ingolstadt]] and [[Sigmund ain Ringeck]]. |

Peter von Danzig's gloss is the shorter one, only commenting on the short sword fencing in armor. The only known copy is found in the [[Starhemberg Fechtbuch (Cod.44.A.8)|Cod. 44.A.8]]. | Peter von Danzig's gloss is the shorter one, only commenting on the short sword fencing in armor. The only known copy is found in the [[Starhemberg Fechtbuch (Cod.44.A.8)|Cod. 44.A.8]]. | ||

| − | The other major gloss is fragmented into multiple versions, including one attributed to [[Sigmund ain Ringeck]] and three others that are anonymous, though we assign their authors the nicknames [[Pseudo-Peter von Danzig]], [Jud] [[Lew]], and [[Nicolaus]] to make them easier to discuss. The Ringeck and Pseudo-Danzig glosses cover all three sections of the Recital, whereas the Lew gloss only covers the long sword and mounted fencing, and the Nicolaus gloss just covers the long sword. These are the only glosses that are known to exist in multiple copies (from six copies of Ringeck to ten copies of Lew), and Lew is the only gloss to | + | The other major gloss is fragmented into multiple versions, including one attributed to [[Sigmund ain Ringeck]] and three others that are anonymous, though we assign their authors the nicknames [[Pseudo-Peter von Danzig]], [Jud] [[Lew]], and [[Nicolaus]] to make them easier to discuss. The Ringeck and Pseudo-Danzig glosses cover all three sections of the Recital, whereas the Lew gloss only covers the long sword and mounted fencing, and the Nicolaus gloss just covers the long sword. These are the only glosses that are known to exist in multiple copies (from six copies of Ringeck to ten copies of Lew), and Lew is the only gloss to have been translated into a second language (Latin). |

| − | These four glosses are somewhat distinct, though they share bits of text freely between them (especially in the short sword and mounted fencing), and today they are generally treated as separate teachings that complement each other well.<ref>In HEMA parlance, they are referred to collectively as "RDL" or "RDLN".</ref> They are similar enough to each other that they almost certainly had a common origin, but it's impossible to say whether this was an original "gloss Q" that they were all modified from or whether they were all the works of a single author modifying his teachings | + | These four glosses are somewhat distinct, though they share bits of text freely between them (especially in the short sword and mounted fencing), and today they are generally treated as separate teachings that complement each other well.<ref>In HEMA parlance, they are referred to collectively as "RDL" or "RDLN".</ref> They are similar enough to each other that they almost certainly had a common origin, but it's impossible to say whether this was an original "gloss Q" that they were all modified from or whether they were all the works of a single author, either modifying his teachings for different audiences or writing at different periods in his life. Hans Medel's gloss (see below) refers to the Ringeck and Nicolaus glosses collectively as the ''gemainer gloss'' ("common gloss"). |

| + | |||

| + | As a final note on the major glosses, it's worth pointing out that only the Ringeck long sword includes an attribution (and the Lew mounted fencing has a statement sometimes interpreted as an attribution). The other three long sword glosses, two short sword glosses, and two mounted glosses are anonymous. The long sword gloss that usually accompanies the Lew mounted gloss tends to also be attributed to Lew, and the short sword and mounted glosses that typically accompany the Ringeck long sword tend to be attributed to him, and the remaining three glosses (which also usually appear together) are classified as pseudo-Danzig. These groupings by association are useful for easy reference, but it should be remembered that there's little evidence supporting them so it's possible we'll discover at some point that they're completely incorrect. | ||

=== Minor Glosses === | === Minor Glosses === | ||

| Line 27: | Line 29: | ||

The minor glosses offer commentary on shorter segments of the Recital. They are all anonymous. Despite their incomplete nature, they are valuable for study because they often present different interpretations from the major glosses and can help develop a more nuanced understanding of Liechtenauer's teachings. | The minor glosses offer commentary on shorter segments of the Recital. They are all anonymous. Despite their incomplete nature, they are valuable for study because they often present different interpretations from the major glosses and can help develop a more nuanced understanding of Liechtenauer's teachings. | ||

| − | The largest of the minor glosses is the one found in the [[Pol Hausbuch (MS 3227a)|Pol Hausbuch]] (MS | + | The largest of the minor glosses is the one found in the [[Pol Hausbuch (MS 3227a)|Pol Hausbuch]] (MS 3227<sup>a</sup>), whose author is nicknamed [[Pseudo-Hans Döbringer]]. This one seems to have been an aborted attempt at writing a major gloss; the verses were written into the manuscript with blank pages left between them to hold commentary, and the author described his work as a ''glossa generalis''. However, despite writing a long introduction to Liechtenauer's teachings, the author only glossed about half of the sections of the Recital on the long sword (and nothing on the short sword or mounted fencing) before abandoning the project. |

| − | + | Three other minor glosses are quite short: | |

| − | * The [[Dresden Gloss Fragment|Dresden gloss]] | + | * The [[Dresden Gloss Fragment|Dresden gloss]], found in [[Johan Liechtnawers Fechtbuch geschriebenn (MS Dresd.C.487)|MS Dresd.C.487]], covers three couplets of the Recital on the long sword (27-28 and 43). |

| − | * The [[Glasgow Gloss Fragment|Glasgow gloss]] | + | * The [[Glasgow Gloss Fragment|Glasgow gloss]], found in [[Glasgow Fechtbuch (MS E.1939.65.341)|E.1939.65.341]], covers the first seven couplets of the Recital on the short sword. |

* The [[Lew|Speyer Fragments]] are a series of nineteen paragraphs added as additional commentary in the copy of the Lew gloss in [[Codex Speyer (MS M.I.29)|MS M.Ⅰ.29]]. | * The [[Lew|Speyer Fragments]] are a series of nineteen paragraphs added as additional commentary in the copy of the Lew gloss in [[Codex Speyer (MS M.I.29)|MS M.Ⅰ.29]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, it can be argued that [[Joachim Meyer]] authored a minor gloss in his [[Joachim Meyers Fechtbuch (MS Bibl. 2465)|1561 manuscript]], covering verses 17-20, 36-54, 58-61, 66, 71, 75-76, 78, and 93 of the long sword. | ||

=== Meta-Gloss === | === Meta-Gloss === | ||

| − | The final entry in the Liechtenauer gloss tradition is that of [[Hans Medel|Hans Medel von Salzburg]]. | + | The final entry in the Liechtenauer gloss tradition is that of [[Hans Medel|Hans Medel von Salzburg]].<ref>This text was probably written by an anonymous student of Medel's rather than by the master himself.</ref> It seems to have been created as a major gloss, but only the only known copy (in [[Hans Medel Fechtbuch (Cod.I.6.2º.5)|Cod.Ⅰ.6.2º.5]]) is incomplete. It discusses the first 87 couplets of the long sword and then stops abruptly at the end of a quire with the title ''Von Zucken''; the remaining pages are lost. |

| − | However, what's most interesting about Medel | + | However, what's most interesting about the Medel gloss is that the author frequently quotes the glosses of Ringeck and Nicolaus verbatim, and sometimes even criticizes them and offers his own interpretations as counterpoint. He also offers a handful of teachings that he attributes to [[Hans Seydenfaden von Erfurt]], a member of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer from whom no other teachings are known to survive. This acknowledgement of and engagement with the prior glosses makes Medel's work unique in the gloss tradition. |

== Hans Lecküchner == | == Hans Lecküchner == | ||

| − | Inspired by the | + | Inspired by the Lew gloss, in the 1470s the priest [[Johannes Lecküchner|Hans Lecküchner]] apparently created his own Recital (expanded from Liechtenauer's) and a gloss to explain it. This text is far longer than any of the Liechtenauer glosses, and the longest single fencing teaching of the 15th century. |

== Jörg Wilhalm == | == Jörg Wilhalm == | ||

| Line 51: | Line 55: | ||

== Joachim Meyer == | == Joachim Meyer == | ||

| − | The final prominent author in the Liechtenauer tradition, [[Joachim Meyer]] owned copies of two of the major glosses (Ringeck and Lew) and | + | The final prominent author in the Liechtenauer tradition, [[Joachim Meyer]] owned copies of two of the major glosses (Ringeck and Lew), and this apparently inspired him to author not only his own minor gloss in 1561, but also an original teaching poem for the long sword based on Liechtenauer's Recital and a gloss of this poem. This is included as the long sword section of his 1568 manuscript and Part Three of the teachings on the long sword in his 1570 book. |

== References == | == References == | ||

Latest revision as of 22:30, 13 October 2024

A gloss is an explanation of a piece of text. It can range from a simple translation for a word in a foreign language to an extensive commentary on a longer passage. In the Medieval period, glosses would typically be written in between the lines of text (if they were short) or in the margins of manuscripts (if they were longer). The process of writing interpretations of existing texts is known as glossing.

Glossing authoritative texts was a common practice in the Scholastic movement of the Middle Ages, and by the 12th century, comprehensive glosses for the entire Bible and many important Roman legal texts had been assembled from the writings of experts of centuries past. These were called glossae ordinariae ("standard glosses") and included both interlinear and marginal commentaries, typically dwarfing the actual text being discussed. The Jewish practice of recording Midrashim in the margins of the Tanakh is a parallel tradition that arose in this same period.

By the 14th century, the tradition of creating formal glosses of authoritative texts had faded away in Scholastic circles, and they were more likely to author entirely new treatises which merely referenced older authorities. However for centuries thereafter, the more famous glosses continued to be commonly reproduced and sold as reference books—the glossa ordinaria of the Bible was even among the first books to be printed after the invention of moveable type. And the practice of recording one's personal thoughts in the margins of books, of course, continues until the present day.

When the Liechtenauer tradition arose in the 15th century, many of its early authors chose to treat his Recital as an authoritative text and fashion glosses to explain their interpretations of it in the manner of earlier generations of Medieval scholars.

Contents

Hans Liechtenauer

There are several different surviving glosses of Liechtenauer's Recital, and they can be broken down into major glosses and minor glosses. These texts all seem to have been created around the middle half of the 15th century, but the age of surviving copies varies quite a lot.

Major Glosses

The major glosses are equivalent to the glossa ordinaria discussed above: they include commentary on the entirety of one or more sections of the Recital. The major glosses are associated with two members of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer, Peter von Danzig zum Ingolstadt and Sigmund ain Ringeck.

Peter von Danzig's gloss is the shorter one, only commenting on the short sword fencing in armor. The only known copy is found in the Cod. 44.A.8.

The other major gloss is fragmented into multiple versions, including one attributed to Sigmund ain Ringeck and three others that are anonymous, though we assign their authors the nicknames Pseudo-Peter von Danzig, [Jud] Lew, and Nicolaus to make them easier to discuss. The Ringeck and Pseudo-Danzig glosses cover all three sections of the Recital, whereas the Lew gloss only covers the long sword and mounted fencing, and the Nicolaus gloss just covers the long sword. These are the only glosses that are known to exist in multiple copies (from six copies of Ringeck to ten copies of Lew), and Lew is the only gloss to have been translated into a second language (Latin).

These four glosses are somewhat distinct, though they share bits of text freely between them (especially in the short sword and mounted fencing), and today they are generally treated as separate teachings that complement each other well.[1] They are similar enough to each other that they almost certainly had a common origin, but it's impossible to say whether this was an original "gloss Q" that they were all modified from or whether they were all the works of a single author, either modifying his teachings for different audiences or writing at different periods in his life. Hans Medel's gloss (see below) refers to the Ringeck and Nicolaus glosses collectively as the gemainer gloss ("common gloss").

As a final note on the major glosses, it's worth pointing out that only the Ringeck long sword includes an attribution (and the Lew mounted fencing has a statement sometimes interpreted as an attribution). The other three long sword glosses, two short sword glosses, and two mounted glosses are anonymous. The long sword gloss that usually accompanies the Lew mounted gloss tends to also be attributed to Lew, and the short sword and mounted glosses that typically accompany the Ringeck long sword tend to be attributed to him, and the remaining three glosses (which also usually appear together) are classified as pseudo-Danzig. These groupings by association are useful for easy reference, but it should be remembered that there's little evidence supporting them so it's possible we'll discover at some point that they're completely incorrect.

Minor Glosses

The minor glosses offer commentary on shorter segments of the Recital. They are all anonymous. Despite their incomplete nature, they are valuable for study because they often present different interpretations from the major glosses and can help develop a more nuanced understanding of Liechtenauer's teachings.

The largest of the minor glosses is the one found in the Pol Hausbuch (MS 3227a), whose author is nicknamed Pseudo-Hans Döbringer. This one seems to have been an aborted attempt at writing a major gloss; the verses were written into the manuscript with blank pages left between them to hold commentary, and the author described his work as a glossa generalis. However, despite writing a long introduction to Liechtenauer's teachings, the author only glossed about half of the sections of the Recital on the long sword (and nothing on the short sword or mounted fencing) before abandoning the project.

Three other minor glosses are quite short:

- The Dresden gloss, found in MS Dresd.C.487, covers three couplets of the Recital on the long sword (27-28 and 43).

- The Glasgow gloss, found in E.1939.65.341, covers the first seven couplets of the Recital on the short sword.

- The Speyer Fragments are a series of nineteen paragraphs added as additional commentary in the copy of the Lew gloss in MS M.Ⅰ.29.

Finally, it can be argued that Joachim Meyer authored a minor gloss in his 1561 manuscript, covering verses 17-20, 36-54, 58-61, 66, 71, 75-76, 78, and 93 of the long sword.

Meta-Gloss

The final entry in the Liechtenauer gloss tradition is that of Hans Medel von Salzburg.[2] It seems to have been created as a major gloss, but only the only known copy (in Cod.Ⅰ.6.2º.5) is incomplete. It discusses the first 87 couplets of the long sword and then stops abruptly at the end of a quire with the title Von Zucken; the remaining pages are lost.

However, what's most interesting about the Medel gloss is that the author frequently quotes the glosses of Ringeck and Nicolaus verbatim, and sometimes even criticizes them and offers his own interpretations as counterpoint. He also offers a handful of teachings that he attributes to Hans Seydenfaden von Erfurt, a member of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer from whom no other teachings are known to survive. This acknowledgement of and engagement with the prior glosses makes Medel's work unique in the gloss tradition.

Hans Lecküchner

Inspired by the Lew gloss, in the 1470s the priest Hans Lecküchner apparently created his own Recital (expanded from Liechtenauer's) and a gloss to explain it. This text is far longer than any of the Liechtenauer glosses, and the longest single fencing teaching of the 15th century.

Jörg Wilhalm

An illustrated treatise from the early 16th century that exists in several manuscripts and is attributed to a hatter named Jörg Wilhalm seems to use the word "gloss" in a different way: the captions to its illustrations frequently end with the statement gloss merk. This is typically rendered "notice the gloss", which is apparently an instruction to refer to the illustration. Alternatively, it might mean "remember the gloss" and be telling the reader to think about the related lesson in one of the Liechtenauer glosses mentioned above, though the manuscripts themselves only include a fragment of the Nicolaus gloss that doesn't include all of the plays that would be referenced in that case.

Joachim Meyer

The final prominent author in the Liechtenauer tradition, Joachim Meyer owned copies of two of the major glosses (Ringeck and Lew), and this apparently inspired him to author not only his own minor gloss in 1561, but also an original teaching poem for the long sword based on Liechtenauer's Recital and a gloss of this poem. This is included as the long sword section of his 1568 manuscript and Part Three of the teachings on the long sword in his 1570 book.