Images

|

Draft Translation

by Nicole Boyd

|

Transcription

by Nicole Boyd

|

|

|

To make it easier to learn this art, we will begin with Theory and after that, we’re going to deal with the Practice necessary to give respect to this profession.

|

[6.1] Per mostrar dunque questa facilità nella presente nostra arte incominciaremo à trattare de’suoi Theoremi: Dopò i quali trattaremo della Prattica, necesarii sima a questa professione.

|

|

|

First of all, we must know that these particular circumstances or cognitions are those which are sought after in connection with the human condition; and although they are not intrinsic to the way a human works, they are always necessarily connected to the operation of man, in such a way that if he cannot do any of them, then he may not be able to do the rest of them:

- the first is the fencer [or operator][19]

- the second is the work, or the action performed

- the third is the matter around which we work;

- the fourth is the instrument with which we work;

- the fifth is the place where we work;

- the sixth is the manner in which we work;

- the seventh is the end [the reason, motivation] for which we work.[20]

|

[6.2] PRimieramente douiamo sapere,

che fette circonstanze, ouer coditioni particolari sono quelle, che si ricercano intorno all'operationi humane: & benche non siano parte intrinseche dell'humane operationi, tuttauia sono sempre necessariamente intorno all'operationi dell'huomo, in modo ch'egli alcuna non ne può fare, che quelle non li siano d'intorno: & la prima e l'operante; la seconda l'opera, ouer'attione operata; la terza è la materia, intorno la quale s'opera ; la quarta è l'instruméto, col quale operiamo; la quinta è in che luoco; la sesta è il modo, secondo il quale operiamo; la settima sarà il fine per il quale si opera.

|

|

|

It will therefore be necessary for the knowledge of this science of arms, for which we consider the aforementioned circumstances [to be addressed in order]:

- the first of which is man

- the second[21] is the act of stabbing

- the third is motion

- the fourth sword to offend and the man to defend

- the fifth in public roads[22] [or a private affair, a duelling field rather than a formal List]

- the sixth is the second way to offend others and defend ourselves I leave victory to the end.

|

[6.3] Sara dunque necessario ad intelligentia di quefta nostra scientia dell'armi, che consideriamo le dette circonstanze, delle quali la prima è l'huomo; la secoda sarà quest'attione di fare alle coltellate; la terza il moto; la quarta la spada per offendere, & il pugnale per difendere; la quinta nelle strade publiche; la seita il modo, secondo, che offendiamo altri, [7.1] & difendiamo noi; lasettima il fine della vittoria.

|

|

|

In truth, the body of a human being is in proportion with itself and is well suited to do everything, [as can be proved] by the ancient architects who created almost all things, such as the building of houses, churches, castles, ships, and also all kinds of factories. Yes, as it was done in ancient times, so is it done in modern times. This principle is particularly shown in Book Ⅲ by Vitruvius.[23]

|

[7.2] Truouasi il corpo dell’huomo compost di cosi misurata proportione; & qualunque parte consi ben rispondente co’l tutto, che gli antichi Architetti dalla proportione medesima cauarono la composition ne di quasi tutte le cose: come di edificar case, chiese, castella, navi, & in somma ogni sorte di fabrica: si come scriuono tutti gli antichi, & moderni, n che di ciò hanno trattato; tra quali in particolare è Vitruvio nel principio del libro Ⅲ.

|

|

|

There is a common, and true, belief by men that their strength[24] will come from their stature, but because some men are bigger in stature, and others are smaller. Each man should understand his stature, Vitruvius says that the foot is the sixth part of the stature of the human.

|

[7.3] Questa proportione dell’huomo su giudicata ottima à far questo, ch’io dico, da questi valent’huomini; anchorche nella statura d’esso huomo nó sia certa, & determinate proportione: perche altri huomini sono maggiori di statura, altri minori: che douendo esser l’huomo di conueniente statura, haurebbe da esser di sei piedi humani: però che dice il medesimo Vitruvio, che il piede é la sesta parte della statura dell’huomo.

|

|

|

In this regard, Vegetio,[25] in the first book of the Art of War, says that Consul Mario celebrates the recruits; i.e. the new soldiers, at six feet high, had at least five feet, and ten inches, which are the ten parts of the twelve. It follows[26] on then that where the six-foot-high man was of average size; and he, who is more than that, being very tall. So the man, when he passes seven feet, is supernatural and is called a Giant, according to the rule of Marco Varrone, as Aulus Gellius puts it in book Ⅲ of The Attic Nights.[27]

|

[7.4] A questo proposito Vegetio nel primo libro dell’arte della Guerra dice, che il console Mario eleggeua i tironi; cioè; i soldati nuoui di sei piedi d’altezza, ò almento di cinque, & deice oncie, che sono le dieci parti delle dodeci. Onde segue che l’huomo alto manco di sei piedi era tenuto di statura mediocre; & colui, ch’è di più di questa esser’altissimo. Onde l’huomo, quando pass ail numero di set- [8.1] te pie piedi, è riputato sopranaturale, è chiamato Gigáte, secondo la regola di Marco Varrone, come riferisce Aulogellio nel Ⅲ libro delle notti Attiche.

|

|

|

This conforms with what [Gaius] Suetonius [Tranquillus] says in the Life of the Octavians about the stature of the Emperor, who was mediocre being five feet and three quarters,[28] but this mediocrity is unknown except at the time and did not affect the fact he was a great man with many victories.[29]

|

[8.2] Con questo si conforma quello, che Suetonio dice nella vita d’Ottaviano, parlando della statura di quello Imperiatore, la quale era mediocre essendo di cinque piedi, & d’vn dodrante, il quale è noue parti di dodeci: ma questa mediocrità non si conosceua, se non quando egli era vinino à qualche persona, che sosse grande.

|

|

|

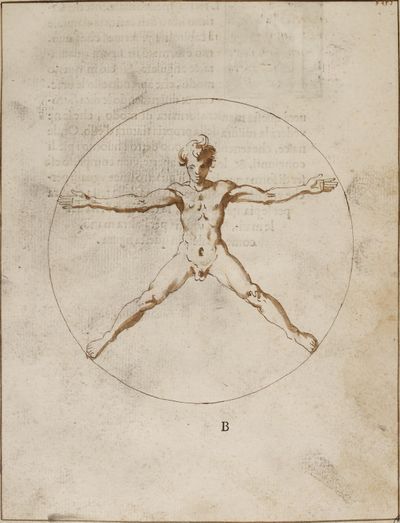

The old philosophers also speculated that the circular figure is the perfect man, and this truth can be understood and measured in this way; let the man lie down flat with his face up and spread his arms, hands and legs as far as they can stretch and draw a circle with the centre being the navel: It’s going to turn out to be round and perfect.[30] This gave Vitruvio himself the title of his third book, and the following figure.

|

[8.3] Hanno poi speculando truouato i Filosofi antichi, che la figura circolare, che è più perfetta di tutte l’altre, si truova nell’huomo perfettamente, la qual cosa esser vera si comprende in questo modo; facciasi che l’huomo si distenda ben con la faccia in sù, & distenda parimiente le braccia, & le mani; le gambe, & i piedi quanto più può distendere, & prendasi vn compass, ò la misura d’vn piede del medesimo huomo, & si misura trahendo la misura dall’ombelico, come da centro: che all’hora si vendrà risultare vn circolo tondo, & perfetto. Questo hà auertito il medesimo Vitruvio nel predetto libro terzo, & lo dimostra questa figura, che segue.

|

|

|

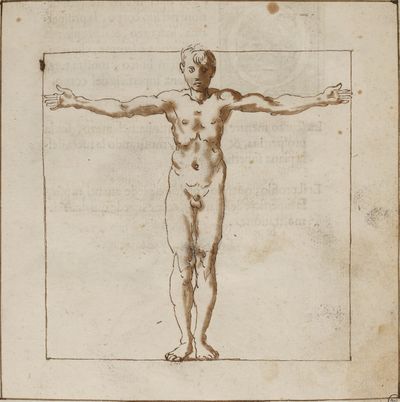

In Chapter 17 of Pliny’s[31] seventh book of natural history he writes,[32] man is a figure of squares and angles and by opening up your arms and by stretching your fingers you will see from this shape that you can measure the size of your height. In the same way by keeping the man’s feet together and open arms are included in the square form of four equal lines, because: the first line passes across the top of the head, the next line passes through where the feet touch the floor, the third line passes through one of the hands and the last line passes through the other hand, as shown in this figure.

|

[10] PLinio medesimamente nel settimo libro dell’historia natural à capitol 17. scriue, che l’huomo è format di figurea quadrata, & angulate; & cio in questo modo, che aprendo esso le braccia, & distendendo le dita si trouerà questa maniera formata di modo, che se ne vederà la misura della propria statura d’esso. Onde nasce, che tenendo al modo detto l’huomo i piedi congiunti, & la braccia aperte, vien compreso esser di forma quadrata, di quattro line vguali: perche vna linea li passa per la cima della testa, l’altra per le piante de’piedi, la terza per l’una delle mani, & l’vltima per l’altra mano, come si palesa in questa figura.

|

|

Prospetiva Scortio Profilo

|

This fencer will have three proportions in his body; his front, his scurzo,[33] and his profile. When he stands in balance the front always shows the whole surface of the body.

|

[12.1] QVest’ operante hà tre proportioni nel suo corpo, la prospettiua, lo scurzo, & il profile: la prospettiua è sempre, che stando egli in bilico, mostra tutta la piana superficie del corpo.

|

The scurzo, while receding in the middle between the perspective[34] and the profile, shows the edge of the flat surface.

|

[12.2] Lo scurzo mentre, che si ritruoua nel mezzo, fra la prospettiua, & il profile, mostrando la meta della piana superficie.

|

And the profile, when the right foot shows the surface of the side: as can be seen from the following demonstration.[35]

|

[12.3] Et il profile, quando col dritto piede auanti mostra la superficie del fianco: come se vede quì dalla dimonstratione.

|

However, he cannot go from extreme to extreme unless he passes through the middle – the perspective and the profile, being the extremes of the scurzo – the fencer should not bring the body from one side to the other, instead should first bring it into the scurzo.

|

[14.1] MA non potendosi passare da vn estremo all’altro, che non si passi per il mezzo; la prospettiua, & il profile essendo estremi dello scurzo non douerà l’operante portar il corpo dall’uno nell’altro, che prima non lo porti nello scurzo.

|

|

|

The proportion of the body is most effectively broken into three types of motion;

- the motion of the whole body together;

- then the motion of the arms;

- then the motion of the leg;

so as not be confused we can say this is the most important principle, and leave the rest up to the painter.[36]

|

[14.2] Le dette proportioni dell corpo si effettuano per gli moti dell’huomo; il quali si diuidono in tre specie; cioè; nel moto di tutto il corpo insieme; nel moto delle braccia; & nel moto delle gambe; i quali essendo i più principali, & che più si confanno al nostro proposito, di quelli diremo, lasciando il rimanente, come quello, che spetta al pittore.

|

|

|

The body’s motions are born from its lengths, latitudes, and proportions; and when they are compressed, turned around, and joined together [the fencer] will gain understanding of what is possible; by turning and stretching [the body’s parts] can be extended long them turn and stretched that it is possible for them to the end of their chains.

|

[14.3] Nascono dunque i moti del corpo dale lungezze, latitudini, & proportioni de’membri; & da loro oprimersi, & girarsi, & conuernirsi insieme con ragione, & possibiltà; & anchora da loro torcersi, volgersi, & slungarsi, sin’à tànto, che gliè possibile, secondo anchora le incatenature, & chiaui loro.

|

|

|

And[37] I will make some rules on these motions by categorising them into eight basic parts, which encompass the total movement of the body:

- upwards

- downwards

- to the right

- to the left

- to extend towards the opponent [forward][38]

- to come away [from the opponent]

- To turn [the body from profile to perspective], and

- to stop.

|

[14.4] Et per dar qualche regola di questi moti; dico, che essi da otto modi, che tiene il corpo di muouersi, nascono: e sono all’insu, all’ingiu, à destra, à sinistral, stendersi per di là, venir per di quà, volgersi dirando, & fermarsi.

|

|

|

Basically, for every motion it is necessary for the body to be supported by the foot, without this support, in the way of bodies, it would tend to fall.

|

[15.1] In ogni moto, ò auanti, ò adietro, è bisogno, che il corpo sia sostentato dale basi: che altrimentri, per esser la natura de’corpi onderosi di tendere al centro, caderebbe.

|

|

|

So it is clear that the motions of the head are such that it is hard for a man to turn around in any part, unless he always has most of his body underneath him; and from this position he can move his weight from side to side and balance[39] so that either leg[40] can bear his weight.

|

[15.2] Quindi s’è cauato, che i moti del capo sono tali, che à fatica giamai l’huomo non si volta in alcuna parte, che sempre nó habbia alcuna parte dell’auanzo del corpo posta sotto di se; dalla quale sia sostentato cosi graue peso; oueram ente, che non ponga dall’altra parte opposta, come vna bilancia, alcun membro, che risponda al peso.

|

|

|

Because the same can be seen, when someone extends his hand it supports some weight: once the foot is stopped, as the foundation of the balance, the other part of the body is opposed to equalize the weight.

|

[15.3] Percioche il medesimo si vede, quádo alcuno distensa la mano sostiene qualche peso: pche fermato il piede, come fondamento della bilancia, tuttua l’altra parte del corpo si contrapone ad aguagliar il peso.

|

|

|

While, the man with evenly distant feet is in a state of rest from which the torso and leg extends up then the end of the chin will remain perpendicular to the tip of the foot.

|

[15.4] Mentre, che in stato si trououa l’huomo co’ piedi pari; & che fá arco auanti di tutto il corpo, & delle gambe; l’estremitá del mento resterá á perpendicolo della punta de’ piedi.

|

|

|

If you put your hand straight out, from the fountain of the body [shoulder],[41] it will always be perpendicular to the feet.

|

[15.5] Opprimendosi, ò á mano diritta, ò á mano manca la fontanella, sempre sará á perpendicolo delli detti piedi.

|

|

|

Whenever the body hangs over the part of the foot on which it poses, the shoulder will be perpendicular to the instep and the other leg will bear the body weight.

|

[15.6] Ogni volta, che il corpo pende da quella parte del piede, che posa, la spalla sará á perpendicolo del collo del piede; & l’altra gamba sará per cotrapeso del corpo.

|

|

|

Always, that if he will raise his arm up, all the other parts of the body from that side down to the foot follow that motion of rising: in a manner that the heel of that foot will rise there from the floor, due to the motion of the same arm.

|

[15.7] Sempre, che se alzerá in alto vn braccio, tutte l’al- [16.1] tre parti del corpo da quel lato insino al piede seguono quel moto d’alzarsi: di maniera, che il Calcagno anchora di quel piede si leuerá lá dal piano, per il moto del medesimo braccio.

|

|

|

A limb is never stretched out to one side, so that the others do not follow; nor does it oppress or constrict itself, so that the others do not follow the line towards the center.

|

[16.2] Non si slunga mai un membro da bna parte, che gli altri non lo seguano; ne per incontro s’opprime, ò si serra, che gli altri non seguano quasi, com line verso il centro.

|

|

|

The legs operate in three kinds of motion, these are; straight, circular, and transverse.

|

[16.3] Le gambe, ouer basi operano tre sorti di moto; cioè; retto, circolare, & traversale.

|

|

|

It is correct, that when turning the body back into perspective[42] the legs should be prepared to take the step.

|

[16.4] Retto, ogni volta, che ritruouádolsi il corpo in prospettiua le nbasi si approno rettamente: come quando si forma vn passo.

|

|

|

While standing still with one foot, one foot can move the same distance as the other foot.

|

[16.5] Circolare, ogni volta, che stando fermo il corpo con un piede, descriue con l’altro vna circonferenza.

|

|

|

Traverse movement, as long as it is perspective, is made of a motion, of a right or left hand.

|

[16.6] Traversale, sempre che si stà in prospettiva; & si fá moto, á mano diritta, overo á mano manca.

|

|

|

Importantly, the legs in profile will not be able to open as much as the length of the body.

|

[16.7] Le gambe in profile non si potranno aprire tanto, quanto importa la lunghezza del corpo.

|

|

|

This line, or quantity described by the opening of the circle of the body, could be divided into infinity: but sufficient for this art we will divide it into four parts, that is,

- in half a step,

- in one step,

- in one and a half steps, and

- in two steps.

|

[16.8] Questa linea, overo quantità descritta dall’apertura del compass del corpo potrebbe esser diuisa in infinito: ma à sufficientia di questa nostr’arte, la diuideremo in quattro parti; cioè; in mezzo passo, in un passo, in un passo, e mezzo, & in due passi.

|

|

|

By placing [weight] on one leg, the other cannot go much further than the space[43] of one step. From these openings in the circle, there are five ways that the body can stand other than in rest.

|

[16.9] Posandosi fvna gamba l’altra non potrà andarui auanti più di quanto importa lo spatio d’un piede. Da queste aperture di compass segue, che in cin- [17.1] que modi il corpo potrà trouarsi in stato, over in quiete.

|

|

|

Firstly, when the body is in the balance, so that, even with the feet joined, the body is perpendicular to the diameter of its circumference; and that in so standing is ready to move all parts [of the body].

|

[17.2] Nel primo, quando è in bilico; cioè; co i piedi pari giunti, & che allhora il pendicolare è nel diametro della sua circonferenza; & che in tale stato è atto di mouersi à tutte le parti.

|

|

|

Secondly, when the man stops, with all the weight of the body on his foot, the instep becomes the base of the Column – which is perpendicularly aligned with the fountain of the throat; this posture[44] was invented by the ancient Polykleitos.[45]

|

[17.3] Nel secondo, quando l’huomo si ferma, con tutto il perso del corpo sopra à vn piede, à guise di base della Colonna, uil qual stà perpendicolarmente sottoposto all fontanella della gola, intendendo il collo del piede, & di questa postura fù l’inventore l’antico Policleto.

|

|

|

Thirdly, when man finds himself at rest in one step.

|

[17.4] Nel terzo, quando l’huomo si truova in quiete in un passo.

|

|

|

Fourthly, while the body is in ‘step and a half’ which then forms an equilateral triangle.

|

[17.5] Nel quarto, mentre che il corpo sia in vn passo, & mezzo, che allhora, forma triangolo equilatero.

|

|

|

Fifthly, when the body is stopped in two steps with the right front foot raised, which is called forced step.

|

[17.6] Nel quinto, quando stà il corpo compassato in due passi andante, che si dice passo sforzato.

|

|

|

From these stills, the man forms six circles, two without setting himself in motion, & four after he has described one of the aforesaid quantities in forming a circle.

|

[17.7] Da queste quieti forma l’huomo sei circoli, due senza, che egli si metta in moto; & quattro doppo, che sarà descritta vna delle quantità dette; & che formarà un circolo.

|

|

|

In the first of the two forms [figure 4] the man, when standing in the balance describes a circle around his feet, the center of which he stands perpendicular.

|

[17.8] Il primo de i due forma l’huomo, quando stando in bilico si descriue vn circolo d’intorno à i suoi piedi, il centro del quale è il pendicolare.

|

Secondly it will be, when the man is in said circle, a circle distant from his body is described, how much its length impacts; the center of here will also be the slope: as you can see in this figure.

|

[17.9] Il secondo sarà, quando stando l’huomo in detto circolo si descriue vn circolo distante dal suo corpo, [18] quanto immporta la sua lunghezza; il centra del qua le sarà pur il pendiiculare: come si vede in questa figura.

|

|

|

The first of the four forms of the man, when finds himself in the state of in stillness in the already mentioned position of second; and when his stance is not stable where the bodyweight resides, with one leg in the centre of the circle, it allows other leg to describe the edge of the circle, [this is the position] which we use to keep ourselves on guard.

|

[19.1] ⅠL primo de’quattro forma l’huomo, quando egli si truova nello stato della seconda quiete già detta; & quando con la base manca stabile, sopra la quale reside il peso del corpo, con quella facendo centro, discriue con l’altra base mobile una circonferenza, della quale si seruiamo per mantenerci in guardia.

|

The second one, when you take one step, then standing in that quiet step, stopping your other foot from moving describe another circle: through this we enter a with traversal[46] motion to exit the points: it also forms the third, whereas, the fourth state is what we will enter when the attack is made, and when he moves into the fifth step, as this figure shows, it is what he will use to fight the enemy.

|

[19.2] Ill secondo, quando si truova in un passo, che stante in quella quiete, fermando il piede manco con l’altro mobile, descriue un’altra circonferenza: & in questa entriamo di moto traversale per uscir fuori co’punti: parimente forma la terza, mentre, che si truouerà nel quarto stato, nella quale entriamo quando si fà la ferita: & la quarta, quando egli si trououerà nel quinto stato di passo sforzato: come dimostra questa figura: & con essa si mãteniamo il nemico lotano.

|