|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Federico Ghisliero"

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| − | | title = Introduction | + | | title = Introduction |

| + | | width = 100% | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Antonio Pio Bonello | ||

| width = 90em | | width = 90em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 40: | Line 44: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[file:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii Title (alt).png| | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii Title (alt).png|400px|center]] |

| <p>'''Rules of many knightly<ref name="Cavagliereschi">''Cavagliereschi'' is Corsican for "chivalrous", while the Italian is "knightly".</ref> armies,'''</p> | | <p>'''Rules of many knightly<ref name="Cavagliereschi">''Cavagliereschi'' is Corsican for "chivalrous", while the Italian is "knightly".</ref> armies,'''</p> | ||

| Line 56: | Line 60: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

| − | | <p>''From Parma on April 22. 1587.''</p> | + | | class="noline" | <p>''From Parma on April 22. 1587.''</p> |

<p> Affectionate Servant</p> | <p> Affectionate Servant</p> | ||

| Line 64: | Line 68: | ||

<p>   Federico Ghisliero. | <p>   Federico Ghisliero. | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii II (alt).png|2|lbl=+ⅱv.2}} | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii II (alt).png|2|lbl=+ⅱv.2}} |

|} | |} | ||

| − | {{master end}} | + | {{master subsection end}} |

| − | {{master begin | + | {{master subsection begin |

| − | | title = | + | | title = Ranuccio Farnese |

| width = 90em | | width = 90em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 80: | Line 84: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[file:Ghisliero_Title.jpg| | + | | rowspan="2" | [[file:Ghisliero_Title.jpg|400px|center]] |

| <p>'''Rules of many knightly<ref name="Cavagliereschi"/> armies,'''</p> | | <p>'''Rules of many knightly<ref name="Cavagliereschi"/> armies,'''</p> | ||

| Line 139: | Line 143: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

| − | | <p>''The Palace of Your Most Serene Highness in Parma, 22 April 1587.''</p> | + | | class="noline" | <p>''The Palace of Your Most Serene Highness in Parma, 22 April 1587.''</p> |

<p> The most humble and devoted servant</p> | <p> The most humble and devoted servant</p> | ||

| Line 147: | Line 151: | ||

<p>   Frederico Ghisliero.</p> | <p>   Frederico Ghisliero.</p> | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/13|2|lbl=+ⅳ.2}} | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/13|2|lbl=+ⅳ.2}} |

|} | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

{{master end}} | {{master end}} | ||

| Line 190: | Line 195: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>And if the man, according to the common nature of his species, has a temperate character not given to any extreme, then this is in contrast to brutish animals, whose natures are greatly inclined to extremes according to the common nature of each species and what we understand of their particular passions. So we see that all hares are timid, all lions are bold, all | + | | <p>And if the man, according to the common nature of his species, has a temperate character not given to any extreme, then this is in contrast to brutish animals, whose natures are greatly inclined to extremes according to the common nature of each species and what we understand of their particular passions. So we see that all hares are timid, all lions are bold, all dogs are irascible;<ref>Hot-tempered.</ref> but man alone has natures common to all species, being timid, bold, irascible, and much subjected to passions.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/16|3|lbl=2.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/17|1|lbl=3.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/16|3|lbl=2.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/17|1|lbl=3.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 196: | Line 201: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Nothing of those inclinations, which have not a second nature common to all species, have determined the particular nature of each man: because for those which are predominantly in choleric humour are naturally hot-tempered; others because they are abundant in blood, are cheerful and bold in nature; and other because they have melancholic humour in excess make sounds of pain and are timid; and there is almost no one who is in all part equal in all quarters of the humours that it results in the passions in all parts being temperate and equal. We are all inclined to one more than another in accordance with the character which is in each of us.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/17|2|lbl=3.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/17|2|lbl=3.2}} | + | | <p>This is why, if the man is melancholic, he will be regarded as acting as an earthly element, being quiet, restrained, anxious and boring; it is as you see the earth, still, grave and narrow.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/17|3|lbl=3.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>The water’s motions,<ref>''Moti'' has a number of meanings in modern Italian aside from "motion", including "motorcycle, bike, watercraft, riot, scooter".</ref> because they’re also falling, if not as bad as the land, are nonetheless limited, and are phlegmatic, which corresponds with the element of water and in the body this quality prevails as timid, simple and humble. The ripples which are almost indulged in the body and cast a pall which brings him low, he turns away his face, and then such calm gives rise to fear. What does that mean? It demonstrates the humanity and the pain.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/17|4|lbl=3.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/18|1|lbl=4.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If there is an increased tendency toward, and attempt to be temperate, and not stretch [the emotions],<ref>The use of square brackets [] shows the insertion of the translator to aid in clarity of meaning throughout the document.</ref> there is a catch; what about the fire? For the sake of appealing elements, which comply with [the person’s will] is the death of the man’s blood (i.e. temperate, modest and real) to the emotions that correspond clearly to the passions of the soul; i.e. the love from which the beloved, the pleasure, the desire, and the hope is born.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/18|2|lbl=4.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>The nature of fire tends toward extreme emotions, as you can see from its flames they reach extreme heights and torture everyone. Similar to this is the emotion of cholera, because they are violent, impetuous and ferocious: and since the emotions are very in like with the two passions, Hate and Anger, they easily appear in the human body, in which this element is predominate.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/18|3|lbl=4.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And because the art can overcome nature we will try to render the timid bold, while the bold man will continue to be bold. Ironically, even if slowly, we will reduce the choleric nature.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/18|4|lbl=4.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/19|1|lbl=5.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>While much fear, by its nature, can corrupt the judgement and impede [that ability of a person] to take advice, and the same can be applied to anger, then it would be easy for the timid to be bold and fear will diminish. The young must be more diligent because if you shy away from reason when increasing your capability with arms, these emotions will be more animated and will pose a danger because failure to manage fear will cause more fear.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/19|2|lbl=5.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>We will moderate cholera, and even the hot-tempered will be better able to use reason, if we operate with good austerity and he does not leave himself to the transports<ref>Contextually, ''transportar'' is in modern Italian ''trasporto'' and has been translated such.</ref> of his passions. We’re going to show him how well he has to balance everything so that he can come back [from his passions] and help stop them. With a plan this can be achieved slowly and safely.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/19|3|lbl=5.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | class="noline" | | ||

| + | | class="noline" | <p>I should also like you to know that in imagining those things we have a great deal of hope, and good company, in whose such honourable members footsteps we can walk, to force, through the art of fencing and its practice, bend these emotions to our will and claim victory over them.</p> | ||

| + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/19|4|lbl=5.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Chapter 2 | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicole Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Nicole Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>''To make it easier to learn this art, we will begin with Theory and after that, we’re going to deal with the Practice necessary to give respect to this profession.''</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/20|1|lbl=6.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''F'''irst of all, we must know that these particular circumstances or cognitions are those which are sought after in connection with the human condition; and although they are not intrinsic to the way a human works, they are always necessarily connected to the operation of man, in such a way that if he cannot do any of them, then he may not be able to do the rest of them:</p> | ||

| + | * the first is the fencer [or operator]<ref>Where the word ''operante'' which means the operator or the person taking action or more simply the will is used elsewhere, I translate it to fencer as operator has the wrong connotations in English for what Ghisliaro appears to wish to convey.</ref> | ||

| + | * the second is the work, or the action performed | ||

| + | * the third is the matter around which we work; | ||

| + | * the fourth is the instrument with which we work; | ||

| + | * the fifth is the place where we work; | ||

| + | * the sixth is the manner in which we work; | ||

| + | * the seventh is the end [the reason, motivation] for which we work.<ref>This is an application of Aristotle’s Causes, in some ways more easily explained due to the application of the sword (though this could be my fencer’s brain), especially as it develops. Ghisliero uses seven rather than four as Aristotle does, or at least using the same method of explanation. [Henry Fox]</ref> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/20|2|lbl=6.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>It will therefore be necessary for the knowledge of this science of arms, for which we consider the aforementioned circumstances [to be addressed in order]:</p> | ||

| + | * the first of which is man | ||

| + | * the second<ref>The spelling of ''secóda'' is ''seconda'' in modern Italian. This shortening of words through the removal of ‘n’ is common in documents of the period.</ref> is the act of stabbing | ||

| + | * the third is motion | ||

| + | * the fourth sword to offend and the man to defend | ||

| + | * the fifth in public roads<ref>Public roads means the location is a public road.</ref> [or a private affair, a duelling field rather than a formal List] | ||

| + | * the sixth is the second way to offend others and defend ourselves I leave victory to the end. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/20|3|lbl=6.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/21|1|lbl=7.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In truth, the body of a human being is in proportion with itself and is well suited to do everything, [as can be proved] by the ancient architects who created almost all things, such as the building of houses, churches, castles, ships, and also all kinds of factories. Yes, as it was done in ancient times, so is it done in modern times. This principle is particularly shown in Book Ⅲ by Vitruvius.<ref>Of Vitruvius’ Ten Books on Architecture. [This same book is referenced in Thibault] [note from Henry Fox]</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/21|2|lbl=7.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>There is a common, and true, belief by men that their strength<ref>Or capacity.</ref> will come from their stature, but because some men are bigger in stature, and others are smaller. Each man should understand his stature, Vitruvius says that the foot is the sixth part of the stature of the human.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/21|3|lbl=7.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>In this regard, Vegetio,<ref>Flavius Vegetius Renatus' ''On Roman Military Matters'' is likely the text to which he is referring. Which was a fourth century commentary on the training of Roman legions harking back to older methods. [note from Henry Fox]</ref> in the first book of the Art of War, says that Consul Mario celebrates the recruits; i.e. the new soldiers, at six feet high, had at least five feet, and ten inches, which are the ten parts of the twelve. It follows<ref>''Onde'' is Catalan. It is ''dove'' in Italian. Both mean ‘where’ in English.</ref> on then that where the six-foot-high man was of average size; and he, who is more than that, being very tall. So the man, when he passes seven feet, is supernatural and is called a Giant, according to the rule of Marco Varrone, as Aulus Gellius puts it in book Ⅲ of The Attic Nights.<ref>A second century book written by a Roman in the Attica region which encompasses the city of Athens.</ref></p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/17|3|lbl=3.3}} | + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/21|4|lbl=7.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/22|1|lbl=8.1|p=1}} |

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>This conforms with what [Gaius] Suetonius [Tranquillus] says in the Life of the Octavians about the stature of the Emperor, who was mediocre being five feet and three quarters,<ref>''Dodrans'' is a Latin contraction of ''de-quadrans'' which means “a whole unit less a quarter” or three-quarters.</ref> but this mediocrity is unknown except at the time and did not affect the fact he was a great man with many victories.<ref>Referencing the ‘ancients’ for authority was commonly used by authors of the time to demonstrate their comprehensive knowledge of the subject. It is intended to add gravitas to the treatise.</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/22|2|lbl=8.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

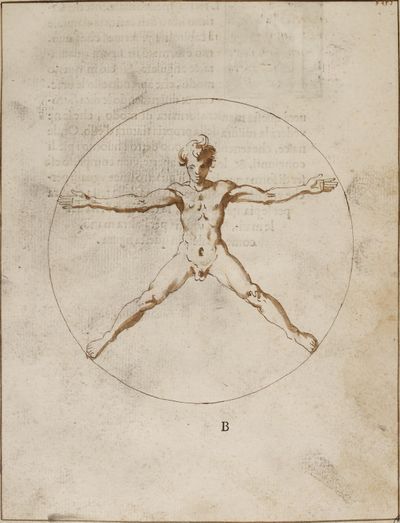

| + | | [[File:Ghisliero 01.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| + | | <p>The old philosophers also speculated that the circular figure is the perfect man, and this truth can be understood and measured in this way; let the man lie down flat with his face up and spread his arms, hands and legs as far as they can stretch and draw a circle with the centre being the navel: It’s going to turn out to be round and perfect.<ref>''All’hora'' is Catalan. Modern Italian is ''al tempo''.</ref> This gave Vitruvio himself the title of his third book, and the following figure.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/22|3|lbl=8.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

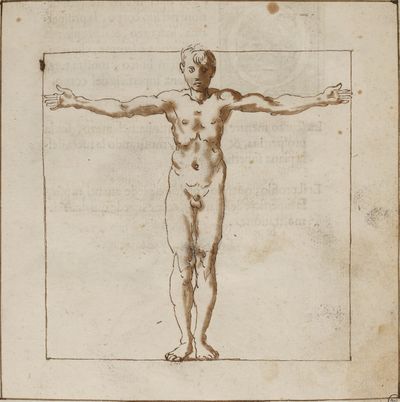

| + | | [[File:Ghisliero 02.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| + | | <p>'''I'''n Chapter 17 of Pliny’s<ref>The Elder.</ref> seventh book of natural history he writes,<ref>''Scriue'' is Catalan. Modern Italian is ''lui scrive''.</ref> man is a figure of squares and angles and by opening up your arms and by stretching your fingers you will see from this shape that you can measure the size of your height. In the same way by keeping the man’s feet together and open arms are included in the square form of four equal lines, because: the first line passes across the top of the head, the next line passes through where the feet touch the floor, the third line passes through one of the hands and the last line passes through the other hand, as shown in this figure.</p> | ||

| + | | {{pagetb|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf|24|lbl=10}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | rowspan="4" | [[File:Ghisliero 03.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| + | <div style="text-align: center;">''Prospetiva   Scortio   Profilo''</div> | ||

| + | | <p>'''T'''his fencer will have three proportions in his body; his front, his ''scurzo'',<ref>''Scurzo'', does not translate appropriately from Italian. As with a number of words in Ghisliero’s treatise, it is likely a Catalase word or a unique spelling. Analysis of other treaties such as Jarod Kirby’s ''Italian Rapier Combat'' (Kirby, 2004) shows the following two definitions, on page 14 of the text, of a similar sound word that is contextually a more likely approximation of what ''scurzo'' means; “''Scanso'', A voidance, any evasive manoeuvre that moves the body of the direct line” and “''Scanso del pie dritto'', A voidance made by moving the right foot slightly off the direct line while turning the body.” So for the purposes of this translation, scurzo will mean in this text the middle stance as shown in Figure 3, i.e. a partial voiding stance halfway between perspective and profile.</ref> and his profile. When he stands in balance the front always shows the whole surface of the body.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/26|1|lbl=12.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>The ''scurzo'', while receding in the middle between the perspective<ref>"Perspective" means front facing forward.</ref> and the profile, shows the edge of the flat surface.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/26|2|lbl=12.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>And the profile, when the right foot shows the surface of the side: as can be seen from the following demonstration.<ref>Also could be interpreted as "figure".</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/26|3|lbl=12.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>'''H'''owever, he cannot go from extreme to extreme unless he passes through the middle – the perspective and the profile, being the extremes of the ''scurzo'' – the fencer should not bring the body from one side to the other, instead should first bring it into the ''scurzo''.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/28|1|lbl=14.1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>The proportion of the body is most effectively broken into three types of motion;</p> | ||

| + | # the motion of the whole body together; | ||

| + | # then the motion of the arms; | ||

| + | # then the motion of the leg; | ||

| + | <p>so as not be confused we can say this is the most important principle, and leave the rest up to the painter.<ref>George Silver’s theory of the time for the hand and foot from his 1599 text Paradoxes of Defense mirrors this framework. [note from Henry Fox] (Silver, 1599)</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/28|2|lbl=14.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>The body’s motions are born from its lengths, latitudes, and proportions; and when they are compressed, turned around, and joined together [the fencer] will gain understanding of what is possible; by turning and stretching [the body’s parts] can be extended long them turn and stretched that it is possible for them to the end of their chains.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/28|3|lbl=14.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>And<ref>''Et'' is Latin for ‘and’ in English and ''e'' in Italian.</ref> I will make some rules on these motions by categorising them into eight basic parts, which encompass the total movement of the body:</p> | |

| + | # upwards | ||

| + | # downwards | ||

| + | # to the right | ||

| + | # to the left | ||

| + | # to extend towards the opponent [forward]<ref>This is not an exact translation – it is the best approximation based on context.</ref> | ||

| + | # to come away [from the opponent] | ||

| + | # To turn [the body from profile to perspective], and | ||

| + | # to stop. | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/28|4|lbl=14.4}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Basically, for every motion it is necessary for the body to be supported by the foot, without this support, in the way of bodies, it would tend to fall.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/29|1|lbl=15.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/ | + | | <p>So it is clear that the motions of the head are such that it is hard for a man to turn around in any part, unless he always has most of his body underneath him; and from this position he can move his weight from side to side and balance<ref>''Balancia'' translates into ‘balance’.</ref> so that either leg<ref>''Membro'' translates to ‘member’, but in English a better word is limb.</ref> can bear his weight.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/29|2|lbl=15.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Because the same can be seen, when someone extends his hand it supports some weight: once the foot is stopped, as the foundation of the balance, the other part of the body is opposed to equalize the weight.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/29|3|lbl=15.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/ | + | | <p>While, the man with evenly distant feet is in a state of rest from which the torso and leg extends up then the end of the chin will remain perpendicular to the tip of the foot.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/29|4|lbl=15.4}} | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If you put your hand straight out, from the fountain of the body [shoulder],<ref>''ò á mano manca la fontanella'' directly translates to something like ‘the hand missing the ''fontanelle''’. This made no contextual sense, so it has been translated to ‘from the fountain of the body’ as ''fonta'' can mean ‘source’ in modern Italian. In the it states that “''Fontánella'', a little fountaine. Also a fontanell or cauterie [something to cauterise wounds], or rowling [turning round about, whirling or turning round], used also for the chiefe vein of a man’s body.” (Florio, 1611)</ref> it will always be perpendicular to the feet.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/29|5|lbl=15.5}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Whenever the body hangs over the part of the foot on which it poses, the shoulder will be perpendicular to the instep and the other leg will bear the body weight.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/29|6|lbl=15.6}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Always, that if he will raise his arm up, all the other parts of the body from that side down to the foot follow that motion of rising: in a manner that the heel of that foot will rise there from the floor, due to the motion of the same arm.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/ | + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/29|7|lbl=15.7|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/30|1|lbl=16.1|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>A limb is never stretched out to one side, so that the others do not follow; nor does it oppress or constrict itself, so that the others do not follow the line towards the center.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/30|2|lbl=16.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/ | + | | <p>The legs operate in three kinds of motion, these are; straight, circular, and transverse.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/30|3|lbl=16.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>It is correct, that when turning the body back into perspective<ref>‘Perspective’ is forward facing as can be seen in Figure 3.</ref> the legs should be prepared to take the step.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/30|4|lbl=16.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/ | + | | <p>While standing still with one foot, one foot can move the same distance as the other foot.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/30|5|lbl=16.5}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Traverse movement, as long as it is perspective, is made of a motion, of a right or left hand.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/30|6|lbl=16.6}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Importantly, the legs in profile will not be able to open as much as the length of the body.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/30|7|lbl=16.7}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | + | | <p>This line, or quantity described by the opening of the circle of the body, could be divided into infinity: but sufficient for this art we will divide it into four parts, that is,</p> | |

| + | * in half a step, | ||

| + | * in one step, | ||

| + | * in one and a half steps, and | ||

| + | * in two steps. | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/30|8|lbl=16.8}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>By placing [weight] on one leg, the other cannot go much further than the space<ref>No good translation found, contextually translating ''spatio'' to ‘space’.</ref> of one step. From these openings in the circle, there are five ways that the body can stand other than in rest.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/30|9|lbl=16.9|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/31|1|lbl=17.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Firstly, when the body is in the balance, so that, even with the feet joined, the body is perpendicular to the diameter of its circumference; and that in so standing is ready to move all parts [of the body].</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/31|2|lbl=17.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Secondly, when the man stops, with all the weight of the body on his foot, the instep becomes the base of the Column – which is perpendicularly aligned with the fountain of the throat; this posture<ref>Polykleitos's ''Doryphoros'' is an early example of this position called ''contrapposto''. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polykleitos for examples of sculptures with this stance. (Wikipeadia, 2021)</ref> was invented by the ancient Polykleitos.<ref>Polykleitos wrote a lost treatise called ‘Artistic canons of body proportions’ in 5th Century Greece which provided a reference for standard body proportions. For more information https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artistic_canons_of_body_proportions (Wikipeadia, 2021)</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/31|3|lbl=17.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Thirdly, when man finds himself at rest in one step.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/31|4|lbl=17.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Fourthly, while the body is in ‘step and a half’ which then forms an equilateral triangle.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/31|5|lbl=17.5}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Fifthly, when the body is stopped in two steps with the right front foot raised, which is called forced step.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/31|6|lbl=17.6}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>From these stills, the man forms six circles, two without setting himself in motion, & four after he has described one of the aforesaid quantities in forming a circle.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/31|7|lbl=17.7}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 04.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| + | | <p>In the first of the two forms [figure 4] the man, when standing in the balance describes a circle around his feet, the center of which he stands perpendicular.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/31|8|lbl=17.8}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>Secondly it will be, when the man is in said circle, a circle distant from his body is described, how much its length impacts; the center of here will also be the slope: as you can see in this figure.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/31|9|lbl=17.9|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf|32|lbl=18|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | rowspan="2" class="noline" | [[File:Ghisliero 05.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| + | | <p>The first of the four forms of the man, when finds himself in the state of in stillness in the already mentioned position of second; and when his stance is not stable where the bodyweight resides, with one leg in the centre of the circle, it allows other leg to describe the edge of the circle, [this is the position] which we use to keep ourselves on guard.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/33|1|lbl=19.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | class="noline" | <p>The second one, when you take one step, then standing in that quiet step, stopping your other foot from moving describe another circle: through this we enter a with traversal<ref>The act or process of passing across, over, or through.</ref> motion to exit the points: it also forms the third, whereas, the fourth state is what we will enter when the attack is made, and when he moves into the fifth step, as this figure shows, it is what he will use to fight the enemy.</p> | ||

| + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/33|2|lbl=19.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Chapter 3 | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicole Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Nicole Boyd]]</p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 300: | Line 551: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

Revision as of 00:01, 20 March 2024

| Federico Ghisliero | |

|---|---|

| Died | 1619 Turin, Italy |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) | Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (1587) |

Federico Ghisliero was a Bolognese soldier and fencer. Little is know about his early life, but he studied fencing under the famous Silvio Piccolomini.

In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii, dedicated to Ranuccio Farnese, who was 18 years old at the time of publication and would become Duke of Parma, Piacenza, and Castro. Ghisliero's manual is notable for his use of geometry in relation to fencing, and the incredibly detailed illustrations, using concentric circles centered on where the fencer has placed most of their weight (often, but not always, the back foot), and illustrating multiple versions of each figure in a plate, showing the progression of the movements he describes.

Contents

Treatise

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Images | Bibliothèque nationale de France | ||

| Translation | Nicole Boyd | Society for Creative Anachronism | |

| Transcription | Nicole Boyd | Index:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) |

Additional Resources

The following is a list of publications containing scans, transcriptions, and translations relevant to this article, as well as published peer-reviewed research.

- Anglo, Sydney (1994). "Sixteenth-century Italian drawings in Federico Ghisliero's Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii." Apollo 140(393): 29-36.

- Gotti, Roberto (2023). "The Dynamic Sphere: Thesis on the Third State of the Vitruvian Man." Martial Culture and Historical Martial Arts in Europe and Asia: 93-147. Ed. by Daniel Jaquet; Hing Chao and Loretta Kim. Springer.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cavagliereschi is Corsican for "chivalrous", while the Italian is "knightly".

- ↑ La gratia is Catalan for "grace".

- ↑ Ghisliero is telling his reader that he is a soldier not a civilian swordsman, so it will have a different perspective to others, hence his later comments on siege craft. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ This and the previous paragraph are commending the work to the patron, justifying the work’s existence and its purpose, common in treatises of the period. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ It was common to refer to “ancients” in the justification of the art of swordsmanship. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ When ‘this art’ or ‘the art’ is referenced it means the art of fencing. [More expansively the arts militari (military arts) or for the more classical, the Arts of Mars, of which swordsmanship falls within.] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Further justification by demonstration of the benefits to those who practice the art in question, also common, especially referring to defense of the person and the realm. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The version dedicated to Antonino instead reads "...for the instruction of the Most Illustrious Lord Antonio Pio Bonello".

- ↑ Cavalier – cavaliere – knights – so indicating the noble nature of the art which he is presenting. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The Humours.

- ↑ Means sad.

- ↑ Means calm.

- ↑ Means optimistic.

- ↑ Means bad-tempered.

- ↑ Hot-tempered.

- ↑ Moti has a number of meanings in modern Italian aside from "motion", including "motorcycle, bike, watercraft, riot, scooter".

- ↑ The use of square brackets [] shows the insertion of the translator to aid in clarity of meaning throughout the document.

- ↑ Contextually, transportar is in modern Italian trasporto and has been translated such.

- ↑ Where the word operante which means the operator or the person taking action or more simply the will is used elsewhere, I translate it to fencer as operator has the wrong connotations in English for what Ghisliaro appears to wish to convey.

- ↑ This is an application of Aristotle’s Causes, in some ways more easily explained due to the application of the sword (though this could be my fencer’s brain), especially as it develops. Ghisliero uses seven rather than four as Aristotle does, or at least using the same method of explanation. [Henry Fox]

- ↑ The spelling of secóda is seconda in modern Italian. This shortening of words through the removal of ‘n’ is common in documents of the period.

- ↑ Public roads means the location is a public road.

- ↑ Of Vitruvius’ Ten Books on Architecture. [This same book is referenced in Thibault] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Or capacity.

- ↑ Flavius Vegetius Renatus' On Roman Military Matters is likely the text to which he is referring. Which was a fourth century commentary on the training of Roman legions harking back to older methods. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Onde is Catalan. It is dove in Italian. Both mean ‘where’ in English.

- ↑ A second century book written by a Roman in the Attica region which encompasses the city of Athens.

- ↑ Dodrans is a Latin contraction of de-quadrans which means “a whole unit less a quarter” or three-quarters.

- ↑ Referencing the ‘ancients’ for authority was commonly used by authors of the time to demonstrate their comprehensive knowledge of the subject. It is intended to add gravitas to the treatise.

- ↑ All’hora is Catalan. Modern Italian is al tempo.

- ↑ The Elder.

- ↑ Scriue is Catalan. Modern Italian is lui scrive.

- ↑ Scurzo, does not translate appropriately from Italian. As with a number of words in Ghisliero’s treatise, it is likely a Catalase word or a unique spelling. Analysis of other treaties such as Jarod Kirby’s Italian Rapier Combat (Kirby, 2004) shows the following two definitions, on page 14 of the text, of a similar sound word that is contextually a more likely approximation of what scurzo means; “Scanso, A voidance, any evasive manoeuvre that moves the body of the direct line” and “Scanso del pie dritto, A voidance made by moving the right foot slightly off the direct line while turning the body.” So for the purposes of this translation, scurzo will mean in this text the middle stance as shown in Figure 3, i.e. a partial voiding stance halfway between perspective and profile.

- ↑ "Perspective" means front facing forward.

- ↑ Also could be interpreted as "figure".

- ↑ George Silver’s theory of the time for the hand and foot from his 1599 text Paradoxes of Defense mirrors this framework. [note from Henry Fox] (Silver, 1599)

- ↑ Et is Latin for ‘and’ in English and e in Italian.

- ↑ This is not an exact translation – it is the best approximation based on context.

- ↑ Balancia translates into ‘balance’.

- ↑ Membro translates to ‘member’, but in English a better word is limb.

- ↑ ò á mano manca la fontanella directly translates to something like ‘the hand missing the fontanelle’. This made no contextual sense, so it has been translated to ‘from the fountain of the body’ as fonta can mean ‘source’ in modern Italian. In the it states that “Fontánella, a little fountaine. Also a fontanell or cauterie [something to cauterise wounds], or rowling [turning round about, whirling or turning round], used also for the chiefe vein of a man’s body.” (Florio, 1611)

- ↑ ‘Perspective’ is forward facing as can be seen in Figure 3.

- ↑ No good translation found, contextually translating spatio to ‘space’.

- ↑ Polykleitos's Doryphoros is an early example of this position called contrapposto. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polykleitos for examples of sculptures with this stance. (Wikipeadia, 2021)

- ↑ Polykleitos wrote a lost treatise called ‘Artistic canons of body proportions’ in 5th Century Greece which provided a reference for standard body proportions. For more information https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artistic_canons_of_body_proportions (Wikipeadia, 2021)

- ↑ The act or process of passing across, over, or through.