|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Federico Ghisliero"

(→Temp) |

(→Temp) |

||

| (32 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called ''[[Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero)|Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii]]'', dedicated to Ranuccio Farnese, who was 18 years old at the time of publication and would become Duke of Parma, Piacenza, and Castro. Ghisliero's manual is notable for his use of geometry in relation to fencing, and the incredibly detailed illustrations, using concentric circles centered on where the fencer has placed most of their weight (often, but not always, the back foot), and illustrating multiple versions of each figure in a plate, showing the progression of the movements he describes. | In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called ''[[Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero)|Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii]]'', dedicated to Ranuccio Farnese, who was 18 years old at the time of publication and would become Duke of Parma, Piacenza, and Castro. Ghisliero's manual is notable for his use of geometry in relation to fencing, and the incredibly detailed illustrations, using concentric circles centered on where the fencer has placed most of their weight (often, but not always, the back foot), and illustrating multiple versions of each figure in a plate, showing the progression of the movements he describes. | ||

| − | + | {{TOC limit|3}} | |

== Treatise == | == Treatise == | ||

| Line 490: | Line 490: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| rowspan="2" class="noline" | [[File:Ghisliero 05.jpg|400px|center]] | | rowspan="2" class="noline" | [[File:Ghisliero 05.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

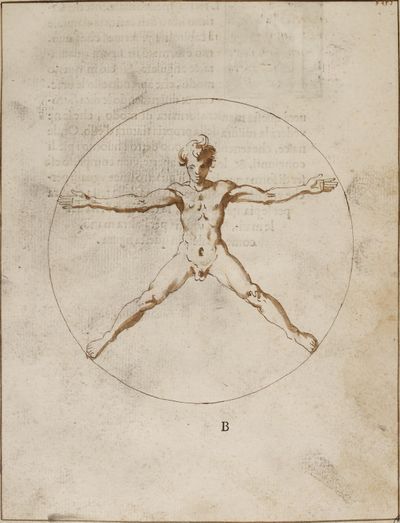

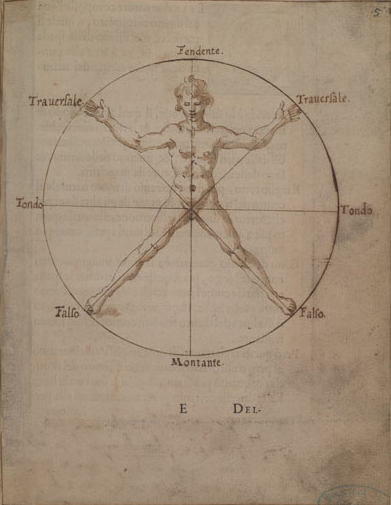

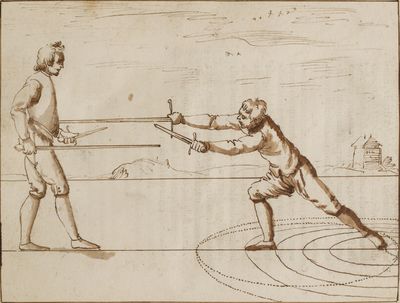

| − | | <p> | + | | <p>'''T'''he first of the four forms of the man, when finds himself in the state of in stillness in the already mentioned position of second; and when his stance is not stable where the bodyweight resides, with one leg in the centre of the circle, it allows other leg to describe the edge of the circle, [this is the position] which we use to keep ourselves on guard.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/33|1|lbl=19.1}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/33|1|lbl=19.1}} | ||

| Line 518: | Line 518: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p> | + | | <p>'''A'''s the motion, and the matter, around which the man operates in this act of stabbing them, we have to know that movement, according to what Aristotle defends in the ninth text of his fifth book of the ''Physica'',s<ref>Aristotle’s fifth book of the ''Physica'', which considers how motion occurs. “Book V classifies four species of movement, depending on where the opposites are located. Movement categories include quantity (e.g. a change in dimensions, from great to small), quality (as for colours: from pale to dark), place (local movements generally go from up downwards and vice versa), or, more controversially, substance. In fact, substances do not have opposites, so it is inappropriate to say that something properly becomes, from not-man, man: generation and corruption are not kinesis in the full sense.” (Aristotle, ''Physica'' (Book 5), (384–322 BC) 2007) “Generally things which come to be, come to be in different ways: (1) by change of shape, as a statue; (2) by addition, as things which grow; (3) by taking away, as the Hermes from the stone; (4) by putting together, as a house; (5) by alteration, as things which ‘turn’ in respect of their material substance.” Book 1, ''Physica'', Aristotle (Aristotle, ''Physica'' (Book 1), (384-322 BC) 2007)</ref> is a mutation, or transmutation: the types of which some want to be six; i.e. Generation, Corruption,<ref>Change of shape.</ref> Augmentation,<ref>By addition or by growing.</ref> Decreasing,<ref>Also taking away or removing.</ref> Alteration,<ref>Putting things together or building.</ref> and Mutation<ref>Change of material substance or alteration of its substance.</ref> place-to-place. None other than Aristotle himself in the first section<ref>“Three kinds of motion - qualitative, quantitative, and local” Book 5, ''Physica'', Aristotle (Aristotle, ''Physica'' (Book 5), (384–322 BC) 2007)</ref> concludes that there are no more than three [types of movement]; i.e. quantity, quality mutation, and location. Of these three types the last type is what we need to know for our art, in which movement is nothing more than transmutation that sometimes causes a body to move from one place to another; and the terms of the movement are two instants.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/35|2|lbl=21.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/35|2|lbl=21.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>The instant in motion and the instant in time is, the Geometric bridge that is counted in magnitude; that is; which is not [just a] part, but is indisible [to it], and consequently is neither motion nor tempo, but it is the beginning and end of every movement and of each time it is finished; as Aristotle describes in the text of the fifth section of book six of the ''Physica''.</p> | + | | <p>The instant in motion and the instant in time is, the Geometric bridge that is counted in magnitude; that is; which is not [just a] part, but is indisible [to it], and consequently is neither motion nor ''tempo'', but it is the beginning and end of every movement and of each time it is finished; as Aristotle describes in the text of the fifth section of book six of the ''Physica''.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/35|3|lbl=21.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/36|1|lbl=22.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/35|3|lbl=21.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/36|1|lbl=22.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 529: | Line 529: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Movement sits between two stillnesses: and the stillness, true rest, is nothing more than the precondition of movement.<ref>This same concept is present in Chapter 5 ‘Of | + | | <p>Movement sits between two stillnesses: and the stillness, true rest, is nothing more than the precondition of movement.<ref>This same concept is present in Chapter 5 ‘Of ''tempo''’ in [[Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli]]’s 1610 publication ''[[Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma (Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli)|Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma]]'' and can be translated into the actions of the fencer undertaking the correct movements - from ward (stillness) to attack or defence (movement) to ward (stillness) again. It propounds that the fencer should always end an action in a ward. The same concept is raised in [[Angelo Viggiani dal Montone]]’s 1551 (published 1575) text ''[[Lo Schermo (Angelo Viggiani)|Lo Schermo d'Angelo Viggiani]]'' (Montone, 1575) and [[Antonio Manciolino]]’s 1531 ''[[Opera Nova (Antonio Manciolino)|Opera Nova]]'' (Manciolino, 1531).</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/36|2|lbl=22.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/36|2|lbl=22.2}} | ||

| Line 571: | Line 571: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>The third bearing is named, therefore, not by us pushing or by us pulling but by carrying ourselves forward: yes, like he does when with the sword, still in a proportion with the motion of our body, we bring it to the tempo here and there.</p> | + | | <p>The third bearing is named, therefore, not by us pushing or by us pulling but by carrying ourselves forward: yes, like he does when with the sword, still in a proportion with the motion of our body, we bring it to the ''tempo'' here and there.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/37|2|lbl=23.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/37|2|lbl=23.2}} | ||

| Line 605: | Line 605: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

* The fifth and final one made by the man, while the whole body is stable by and centred on the hand’s wrist,<ref>“''Rascetta'', the wrist of one’s hand. Also a kind of fine silke-rash.” (Florio, 1611)</ref> describes the smallest possible circumference that he can describe; which we use to make holes in the knuckles. | * The fifth and final one made by the man, while the whole body is stable by and centred on the hand’s wrist,<ref>“''Rascetta'', the wrist of one’s hand. Also a kind of fine silke-rash.” (Florio, 1611)</ref> describes the smallest possible circumference that he can describe; which we use to make holes in the knuckles. | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/38|3|lbl=24.3}} | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/38|3|lbl=24.3}} |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 630: | Line 630: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p> | + | | <p>'''T'''he offensive instrument is the sword, & the dagger is the defensive one and although sometimes the sword makes the dagger’s offering by parrying; and the dagger makes the sword’s offering by attacking, this happens by accident.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/38|5|lbl=24.5}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/38|5|lbl=24.5}} | ||

| Line 759: | Line 759: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

| − | | <p>The defending line must be used to bring the line opposite to the center from where it originates: but when it finds itself in the center it must be beaten, and when it is not there it must be helped, so that it may arrive more quickly at its decline through natural motion.</p> | + | | class="noline" | <p>The defending line must be used to bring the line opposite to the center from where it originates: but when it finds itself in the center it must be beaten, and when it is not there it must be helped, so that it may arrive more quickly at its decline through natural motion.</p> |

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/44|2|lbl=30.2}} | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/44|2|lbl=30.2}} |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 788: | Line 788: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p> | + | | <p>'''T'''he sixth condition, which is the manner in which we offend others and defend ourselves, consists principally in securing our body against the enemy’s offense; and therefore the offense will never be taken if we are not first certain of the defense. Nor will we ever defend ourselves simply, if at the same time we do not offend, for the true defense is to offend, which we will do with resolution; and if we are always the first to execute the attack.<ref>Here Ghisliero’s methods conforms to common Italian approaches of defence to: always counter an opponent’s attacks with consideration for returning the attack, always attack with concern for defence, and not attack unless secure against the opponent’s attack. [note from Henry Fox]</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/45|1|lbl=31.1}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/45|1|lbl=31.1}} | ||

| Line 879: | Line 879: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

| − | | <p>''Punta riversa'' is that which parts [wounds] as it departs.</p> | + | | class="noline" | <p>''Punta riversa'' is that which parts [wounds] as it departs.</p> |

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/50|3|lbl=34.3}} | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/50|3|lbl=34.3}} |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 994: | Line 994: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

| − | | <p>In order to put an end to the seven circumstances, which are involved in all human operations, it remains to know brieflythe end, for which man dies in this action; and this is victory, which being known by itself, there is no need to say any more about it.</p> | + | | class="noline" | <p>In order to put an end to the seven circumstances, which are involved in all human operations, it remains to know brieflythe end, for which man dies in this action; and this is victory, which being known by itself, there is no need to say any more about it.</p> |

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/54|5|lbl=40.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/55|1|lbl=41.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/54|5|lbl=40.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/55|1|lbl=41.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,047: | Line 1,047: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

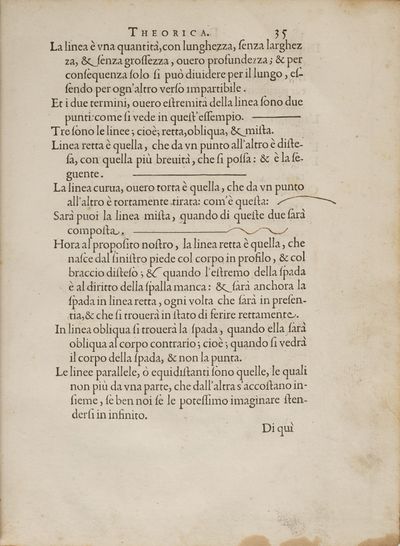

| − | | <p>And in this way we will consider the line in our operation abstracted from the matter of the sword, when it is not present; but when it is placed in a straight line, then we will consider the line applied to the matter of the sword.</p> | + | | class="noline" | <p>And in this way we will consider the line in our operation abstracted from the matter of the sword, when it is not present; but when it is placed in a straight line, then we will consider the line applied to the matter of the sword.</p> |

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/56|6|lbl=42.6|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/57|1|lbl=43.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/56|6|lbl=42.6|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/57|1|lbl=43.1|p=1}} | ||

|} | |} | ||

{{master subsection end}} | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| − | + | ||

{{master subsection begin | {{master subsection begin | ||

| title = Chapter 8 | | title = Chapter 8 | ||

| Line 1,067: | Line 1,067: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>''Turning now to other principles, I say to you that, just as in other human operations seven conditions are necessary, so in this particular action of arms the same seven conditions are involved, namely, will, knowledge, measure [distance], time, occasion, place, and weight.''</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/57|2|lbl=43.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''T'''he will is the one on which all our actions depend, since all the actions of the powers and of all the limbs are instruments of the will, which is the principal agent. This is in man, like a king who has a principal councillor, according to whose opinion he knows that he must do all things; and this is the intellect. He also has certain other subjects, who are like speculators; if they sometimes succeed in lying: and these are all the external, and internal senses. In addition to these, he has two other subjects, as his lieutenants; who must be ready to await the commands of the King, in order to obey him: which are the cognizable, & the irascible, which are appetitive powers: the office of which is to command the movement of the limbs. Lastly, the King has a minister, who is responsible for the execution of all that is imposed by him or by his lieutenants: and this executioner is the motivating force, who, according to his needs, uses the body and its parts as if they were instruments.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/57|3|lbl=43.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/58|1|lbl=44.1|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>Now, in order to apply this to our purpose, I say that it is necessary that in the act of arms we have the will ready, with all its officials; so that the deadly virtue operates according to what it is going to do: and that it be intent on the attack more quickly than on the parry.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/58|2|lbl=44.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>'''S'''cience is the knowledge of something by its causes: and the question is asked of that thing, from where comes the essence and what is its cause; and by this one can conveniently assign the reason, once it arrives.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/58|3|lbl=44.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>And just as in four ways, and no more, one can by reason dispel all doubts as to what effect it may have, or as to the producer of it, or as to the end of it; so there are only four kinds of causes of the effects; that is, the material, the formal, the factual, and the final.<ref>The effect of these causes is the fencer hitting their opponent using the technique. Poor technique means the fencer misses and/or dies.</ref></p> | ||

| | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/58|4|lbl=44.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/59|1|lbl=45.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>The material cause<ref>The material causes are the movements of the fencer’s body and sword.</ref> is that subject which, being under the form, is never dissolved from it until the form is sound, just as we shall say that motion is an example in these effects of our fencing.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/59|2|lbl=45.2}} | ||

| − | | | + | |- |

| − | + | | | |

| − | {{ | + | | <p>Formal [cause]<ref>The formal cause is how the fencer uses the movements of the material cause.</ref> is that figure, or form, or fulfillment, which gives the intrinsic mode, and being, and appropriateness to that compound, which makes it be, as it is required to be that, of which it is the form: as for example are the proportions of lines.</p> |

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/59|3|lbl=45.3}} | ||

| − | {{ | + | |- |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>The factual cause<ref>The factual cause is the fencer, with their measurements and proportions, and their ability to perform the material causes.</ref> is that cause from which comes the principle of that movement, and of that operation, which is necessary to the production of its effect: as for example, of the proportion of the straight line, the man who made it is the factual cause of that.</p> | |

| − | }} | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/59|4|lbl=45.4}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>The final cause<ref>The final cause is the actual technique the fencer is trying to achieve.</ref> is that usefulness, or rather that apparent good, by which every worker is induced and encouraged to do his work, in order not to work in vain: as can be seen in the example of the straight attack: the apparent good of obtaining victory by means of that attack is the final cause.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/59|5|lbl=45.5}} | |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>From matter, therefore, and from form, as from intrinsic causes, and proper essential parts, depend all things composed; so artificial, as natural: and likewise from that artificer [creator], who makes them, and from the end, which leads to them, as from extrinsic and external causes, they depend on their production.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/59|6|lbl=45.6|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/60|1|lbl=46.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>And in whatsoever kind of cause, or mode of that cause, one may consider the cause, as well as the effect. And this sometimes in power, or rather readiness to produce it; sometimes in action; that is to say, in readiness, and aptitude to be able to do it: but we shall not say that man is the actual cause of the said wound, since at present he has not produced it.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/60|2|lbl=46.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''T'''he measure [distance]<ref>Measure also often called distance. The measure of something is fluid due to the fencer’s, and their opponent’s, relative proportions in each combat and other considerations regarding weaponry. “The Spanish attempt to make it more certain by using proportionality, measuring against the length of the individual.” [note by Henry Fox] [[Gérard Thibault d'Anvers]] 1628 treatise Academie de l'Espée (d'Anvers, Academie de l'Espée, 1630) “…the Distances and Instances (i.e. steps in the process of fighting) to be observed in training (which are the basic foundations and support for all the following parts) proceed from the proportions of Man, therefore without this same awareness, they cannot be duly comprehended, nor practiced with confidence. And the same goes for the Steps and Approaches, short and long, required by the variety of positions in the performance of these Exercises. From which it is apparent that one must begin with a good knowledge of the proportion of limbs and body parts, that one may at least be able to make some reasonable judgement on the reach of each movement, proportionally to the limb, or limbs, on which the movement depends, and from which it must be continued, ended, turned, returned, released, bound, or changed in a thousand different ways.” (d'Anvers, Academie de l'Espée - – Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 1 –Philosophical Discussion; Construction and Mathematics of the Circle; Concerning the Sword: Proper Length and Introduction explanation of the first plate., 1630)</ref> by which we certify the quantity of the thing, is that quantity of ground, which is between the two combatants: and up to now they have tried to gain more or less knowledge of it by practice. And many have been accustomed to measure themselves, as the Spanish do: which is uncertain.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/60|3|lbl=46.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>But we, wishing to establish a certain and determinate measure [distance], will consider the circle, according to which the body is formed in the first circle: as we have stated above.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/60|4|lbl=46.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/61|1|lbl=47.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And if men are unequal in stature, nevertheless, in conformity with their size, they describe the second circle well: and provided that the enemy is greater in height, nevertheless he never exceeds so much that he can increase the advantage held by the one who stands in the first circle.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/61|2|lbl=47.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 08.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| + | | <p>We therefore conclude that in order for the enemy to reach the center of the circle he must reach the circumference with one of his feet, because the length of the sword, which is two arms long,<ref>Approximately 46 to 50 inches or 117cm to 127cm.</ref> together with the hand and arm, makes a length of three arms,<ref>Approximately 69 to 75 inches or 175cm to 191cm.</ref> which is the distance from the circumference to the center.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/61|3|lbl=47.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>Hence this fellow, who is in such a state, will be able to open his compasses, and stop his enemy at a distance from his circumference, as far as the opening of his compasses allows: as we see here in this figure.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/61|4|lbl=47.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''T'''ime is so closely related to, and connected with, motion, from which it can never be separated (for there can be no motion which is not slow or swift; and consequently made in more or less time) that it is necessary that it should be substantially or accidentally connected with motion; that is to say, that it should be one and the same thing; or that it should be an intrinsic accident.<ref>Distance can be measured by Time, and Time measured by Distance so in effect one is the other, and every action toward or away from an opponent is measured in both Time and Distance; he seems to say much the same thing further along. [note by Henry Fox]</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/63|1|lbl=49.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Therefore, since it is clear that if time were motion, it would follow that, just as speed and slowness are conjugated with one, so they would be conjugated with the other: for if it is true to say that this or that motion is either fast or slow, we shall not, nevertheless, call any motion fast or slow, since it is not possible to define anything as being the same: it remains, therefore, that it must at least be an accident.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/63|2|lbl=49.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And since those accidents, by their quantity, make known, and determine the quantity of some subject, they can for this reason be asked to measure that subject.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/63|3|lbl=49.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Tempo is therefore the number, or rather the measure [distance] of the movement, according to the fact that two instants, one before and the other after, determine the movement of both parties. And there are three times, past, present, and future; of these we need not speak of the past.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/63|4|lbl=49.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/64|1|lbl=50.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>The present time in the action of arms cannot be known by us except by accident, when it happens that the opposite operates according to the customs of others; of whom we have knowledge: for, if time is the measure of motion, we cannot have knowledge of such time, if we do not first consider the nature of motion.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/64|2|lbl=50.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>For when motion is made by his own free will, and when the other has to receive motion from him, he will not be able to set himself in motion at the same time that the other begins to move, but he will be able to do so later, and consequently he who first sets himself in motion will finish before the other who has to receive motion from him. Therefore we will not be able to have any knowledge of this measure [distance] of motion, which is called fixed time.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/64|3|lbl=50.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Since, therefore, we have knowledge of time, we will have to operate in two ways: in the first (since motion is born of stillness) we will consider the nature of the stillness of the enemy’s sword: and the stillness likewise of the enemy’s state: for these will show us future motion; and consequently we will have knowledge of its measure [distance]; that is, of future time, called premeditated [''tempo''].<ref>Aristotelian motion is the consideration of “a stillness and motion” and is used by Capo Ferro as a method of reading the opponent in Chapter 5 ‘Of Tempo’ (Cagli’, 1610) [note by Henry Fox]</ref></p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/64|4|lbl=50.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/65|1|lbl=51.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In addition to this, we will give the enemy the motion; for which we will require him to make another motion as well; and consequently we will have knowledge of future time.<ref>Obligatory motion is the beginning of second intention. The fencer moves in a particular way so that the opponent has to do something in response, and then the fencer can follow on with their plan. [Note by Henry Fox]</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/65|2|lbl=51.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In the meantime, we shall ascertain that the movement which we make in order to impart motion to the enemy should be of short duration, so that it may be completed before the enemy becomes aware of it: and that, if he wishes to injure, he must make a greater movement than we shall make in order to impart motion to him: which will be easy for us if we keep the body together, so that it may immediately obey our will.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/65|3|lbl=51.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And in order that we may know ''tempo''<ref>I will start using ''tempo'' from this point on instead of time when describing time as a measure of distance, to differentiate between it and the common use of the word time. Following Ghisliero’s explanation of ''tempo'', it will be easier to use ''tempo'' to encapsulate this meaning.</ref> immediately, we shall apply to the motion which we make with our legs the time which is the measure of song or music: and since we may be in a state with our left foot in front when we depart from that stillness, and with our right foot against it as we pass to the fourth circumference, the measure of this motion will be eight beats, which is as important as a maximum.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/65|4|lbl=51.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>With the right foot we can then make four openings, as we have said: and the first is when we find ourselves in the first circle with the right foot in motion, we take the forced step; that is when we reach the fourth circle: that this motion is of four beats, as is a lunge.<ref>Sometimes extended to ''botta lunga'', depending on the author [note by Henry Fox].</ref> We will only use this motion when the enemy is at a distance.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/65|5|lbl=51.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/66|1|lbl=52.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>When we then form the step in force, called an equilateral triangle (of which we use in making the attack) the measure of this motion consists of two beats: which is worth a short [''tempo''].</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/66|2|lbl=52.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>The measure of the step formed when the right foot touches the second circumference, which is made in motion, is one measure, which is worth one half-step.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/66|3|lbl=52.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In forming a half-step, we will measure a motion, which will be of half a beat: as is the minimum ''tempo''.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/66|4|lbl=52.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>That small opening of the compass which is made when the body is at its second rest, is a measure of ''tempo'', as is the value of a woman: that two together make a minimum.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/66|5|lbl=52.5}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Likewise, in order to give some rule for knowing the time of attacking, I say that it is when the opponent makes some movement, either with the sword alone, or with one of the legs, or with the right or the left, and when they make feints and provocations with the sword: all these movements, whether they be thrusts, or retreats, or turns, or provoking, always attack in those times.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/66|6|lbl=52.6}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And in three ways we attack, before the time, in the time, and after the time.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/66|7|lbl=52.7}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Forward in time it is called attack by premonition:<ref>“Attack into preparation” is what it is called in modern nomenclature, catching the opponent while they are preparing to act. [note by Henry Fox]</ref> and it is when the enemy is stationary with his sword parried, attacking him in that case on the nearest side.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/66|8|lbl=52.8|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/67|1|lbl=53.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In time, the enemy is attacked when he is in motion, executing the attack, or parrying: and in such a case he attacks the side which is in motion with the attack, which will be the right side, or the side which is in motion with the defense, which will be the left side.<ref>An action in half-time, because the action is in motion, thus not completed, interrupted. [note by Henry Fox]</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/67|2|lbl=53.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>After the time the attack is made, when the movement is at an end, returning to quietness, and the decline of the attack is followed. It is time to attack, when the sword leaves the imagined straight line, passing through our sight.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/67|3|lbl=53.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''L'''et all those who know that things must be done in their proper time and place, and never after that. We must therefore consider that, just as it is necessary to wait for it, and to choose it in order to act, so it is also necessary to take care not to let the point pass completely, at which it is good to give the thing we propose: which we call an opportunity, or conjunction; which, when lost, can rarely be regained.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/67|4|lbl=53.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And this occasion is a part of ''tempo'', which has in itself the opportunity to do something suitable. And this is considered in two ways: in the first, when the enemy provokes us with an injury; or when he makes feints or calls on us; or when he gives us a straight line; and in such a case one must not lose the opportunity to injure the enemy.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/67|5|lbl=53.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/68|1|lbl=54.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In the second mode of opportunity is when we ourselves procure it, but in the proper manner, and not in the said terms: which are errors: as we shall learn from what follows.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/68|2|lbl=54.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''P'''lace is nothing other than the interior and ultimate surface of that body which contains it: which on all sides touches and approaches the ultimate, extrinsic [outward] surface of the body which is contained.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/68|3|lbl=54.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Therefore, for our purpose, the superficial surface of the opposite body will be the one which touches on all sides the extrinsic [outward] and ultimate surface of the sword, which then wounds the body.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/68|4|lbl=54.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And because there are two ways of saying that something is found in this matter; that is to say, a common place of the attack will be the entire surface of the entire body: [but] the proper place will be a part of the surface, which ordinarily is that which lacks defense and which protrudes out the most.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/68|5|lbl=54.5}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And since the center of the body, in all the motions of the same body, is the part which is most immobile, we shall injure that part, as the proper place.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/69|1|lbl=55.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''S'''ince, as we have seen in the composition of man, he has his body composed of four elements, of which the two heavy ones cause the weight in him, which has the power to tend downwards; and also to resist contrary motion. That is to say, to those who would pull him backwards; and since the members of the body serve the will, as instruments of motivating virtue, we will not be able to obey them with the said elements, if the weight is not distributed in them, according to need.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/69|2|lbl=55.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>However, we must know that the weight of the body is distributed between the two columns [legs], and that it can be placed sometimes on one and sometimes on another. But this must be given with reason: since these two columns [legs] are the ends of the pendicular, which is in the middle; and since it is not possible to pass from one end to the other without passing through the middle, it will be necessary for the weight to be transported by these two columns [legs]; just as, if the weight is found on the missing leg, it will be transported to the right side, then it will be necessary first to place it in the middle, that is, in the pendicular, and then to unload it on the right side: and this will likewise be done from the right side to the left.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/69|3|lbl=55.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/70|1|lbl=56.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And because the part of the body that has to make any movement, whether it be upright or oblique, will not be able to do so comfortably if it is not relieved of its weight: therefore, the column [leg] that has to stand still, as if it were the leg of a compass, will always support the entire weight, so that the other relieved column [leg] can obey the will, carrying out the movement that will be commanded to do.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/70|2|lbl=56.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And by walking in an orderly manner with natural steps, the weight will be held together in action; so that it may be placed on one of the two legs as needed.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/70|3|lbl=56.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | rowspan="3" class="noline" | [[File:Ghisliero 09.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

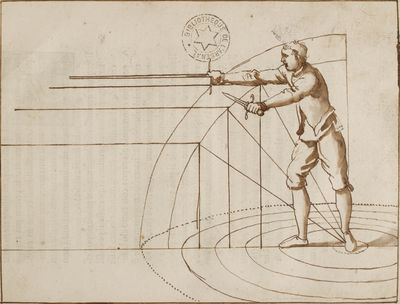

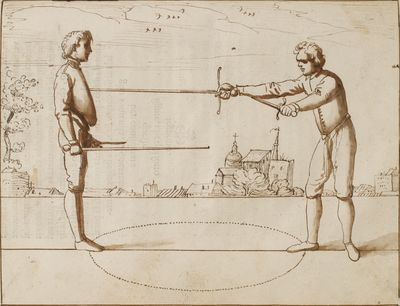

| + | | <p>In the same way, if a man wishes to gain ground on the right or left side, he must move by carrying the weight in the middle, and then the weight on the right leg, unloading it, and then gathering the missing leg in the first circle. However, he must never be bound to use both legs to move, except when he is walking.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/70|4|lbl=56.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>And in order that man may obtain the aforesaid particularity, we must know that the second circle, which he forms in motion, is divided into four right angles with two diameters: and while man is in the first of his circles, that is to say, in balance; and since it is necessary for him to leave, either with his right hand, or with his left hand, or forward, or backward, he will do so by moving only one of his legs, and with the other stable, remaining in the center of the first circle.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/70|5|lbl=56.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/71|1|lbl=57.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | class="noline" | <p>And it should be noted that while we find ourselves with our feet in the first circle, and that we leave the first circle with a leg, and that we enter the second circle, which is set in motion, then we will divide that second circle into four plane trilateral figures, closed, and contained by three straight lines. And considering each of the three circles by itself, each time that a man is placed in one of them, and wishes to enter into one of the others, he will have to return to the first circle, which is made when stationary: and then, according to need, he will go into one of the four said figures; which is demonstrated by the figure which follows.</p> | ||

| + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/71|2|lbl=57.2}} | ||

|} | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Chapter 9 | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>''Since we have declared the seven circumstances which concur in the operation of arms, we must know that in order for an action of ours to be dependent on virtue, it must have four conditions; that is, that it be spontaneous, consulted, chosen and willed.''</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/73|1|lbl=59.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''S'''pontaneously done is understood to mean that we do it of our own free will; and conversely, those actions which we do not do of our own free will can be said not to be spontaneous.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/73|2|lbl=59.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>From this it follows as a rule for us, that a man in the act of arms, will do all his actions voluntarily, being the first to make a firm commitment: and consequently he will act in such a way that his opponent will have to do everything against his will, forcing him to parry.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/73|3|lbl=59.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Consultation, as Aristotle determined, is about those things which can fall under human counsel.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/73|4|lbl=59.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Therefore, in this art of ours, we will well consult all the means that can lead us to our goal, which is victory.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/73|5|lbl=59.5}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Election [choice or discrimination] is nothing other than a consent or assent to those things which are placed within us: for since a thing is first consulted and then elected, if it is first consulted and then judged, it will reasonably be elected.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/74|1|lbl=60.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>So that from these two conditions, which I have joined together, we shall constitute a rule, that after having consulted the means of offense +& defense, we shall choose the best proportion of injury and defense, and that we shall continually operate.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/74|2|lbl=60.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Our will is ready to have regard to that end, which is not only truly good, but also apparent: for the acquisition of which we must then spontaneously within ourselves consult the means, which can lead us to it; and those, finally, choosing virtuously to operate; as we shall do in the battle of arms, which is fought from hand to hand. If, having regard to the true good, which in this action is to defend oneself and to offend the enemy, we shall consult and choose those things which we will animously put into execution, which otherwise will annul the whole art of arms. </p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/74|3|lbl=60.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | [[File:Ghisliero 10.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

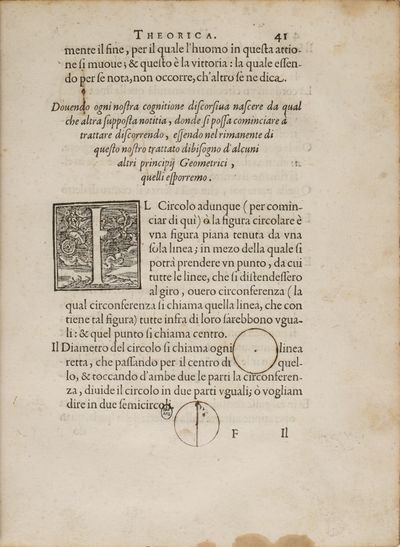

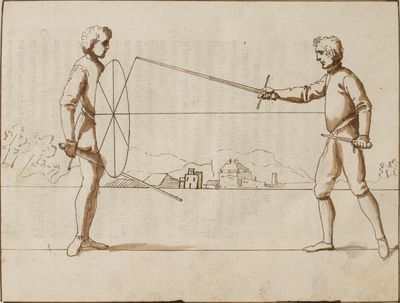

| + | | <p>And since from one point to another there is nothing but a straight line, and since one line is in the subject, the other cannot enter it, since two bodies cannot be in the same space at the same time, it remains that each time that two men come to combat each other, there will necessarily arise a circle of distance: which, starting from its diameter, and each of them forming a point, the one who first puts his sword into the diameter, which consequently becomes the straight line, will force the other to pass through it, so that he will have the offense as well as the defense, since the enemy’s sword will be parallel to his body. And so that this may be better understood, these figures, which follow below, should be well considered.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/74|4|lbl=60.4|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf|75|lbl=61|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''T'''he knowledge of arms being based on this, it has come to pass that the operations of those who have so far dealt with this matter have been various: they have either placed themselves in it, or else they have given the place, so that by parrying the enemy they might at the same time secure themselves by parrying; and by putting their sword in a straight line they might attack.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/77|1|lbl=63.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Those who have put their sword forward in a straight line have done so for the aforesaid reason, which is most important; and to keep themselves covered by the sword; and to keep the enemy at a distance: hence there are so, so many ways of gaining it.<ref>This is an important note; the sword is extended and the fencer is covered by the extension of the sword in a straight line. [note from Henry Fox]</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/77|2|lbl=63.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And the first, as is the custom in Spain and Italy, is to gain it by dividing the sword into three parts: of which the first, towards the fist, is the ''forte'',<ref>Strongest third of the blade from the hilt toward the middle.</ref> because it is closer to the moving power: and the last is ''debole'',<ref>Strongest third of the blade from the hilt toward the middle.</ref> because it is far from the moving power: but while it is weak in parrying it is very strong in attacking.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/77|3|lbl=63.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Proceeding in this way, one must have placed his sword above that of the enemy in the ''debole'',<ref>Note the positions of the weapons relative to one another. This is consistent with the Aristotelian and the Iberian approaches. [note | ||

| + | from Henry Fox]</ref> keeping his arm gathered, and the fist of his hand placed on the level, or rather a little lower than that of the enemy.<ref>The position of the hand and blade position in this initial stage is vital to the techniques that will follow. [note from Henry Fox]</ref> In such a way that, while waiting for the other hand to release it, at the same time one gains a straight line by extending the arm. As a rule, one should keep in mind that one should go to the sword at one moment, and at the enemy body at another.<ref>This appears to be discussing taking the line or ''stringeri''.</ref></p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/77|4|lbl=63.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/78|1|lbl=64.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In defense of this, which I have said, it was customary at the time when the sword was in motion, in order to overcome it, to stop it in said motion, and to free the sword,</p> | ||

| + | * by making a motion with the sword alone, or | ||

| + | * by using the disengaged joust, which is to carry the body from one leg to the other; or | ||

| + | * by withdrawing the left foot behind: and in this way proceeding from hand to hand, one against the other. | ||

| + | <p>But this is more likely to be used as a feint than as a real attack: since men are unequal in size and strength, just as swords are unequal in length and weight, an altered man is unable to discern the minutiae of the game; and since this game is founded on uncertain principles, it will also be uncertain.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/78|2|lbl=64.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Some of them prevent many of these inconveniences by finding themselves in said line with their swords; when the enemy goes to square them, at that time they carry their swords outside the straight line. When they meet the enemy’s sword out of the straight line, and then, by placing their shoulder on the wall, without separating their sword from the enemy’s, they cross the line with their foot and strike with a ''punta riversa''.<ref>A “reversed thrust” in this instance.</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/78|3|lbl=64.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Many of them, having considered that while they were gaining the weakness of the enemy’s sword, they could be attacked at the same time. In drawing their sword from the enemy, kept this order in going to the enemy’s sword, to bring the body towards it, so that if the enemy freed his sword, and attacked, he would find no place to attack: so that in that movement they put their sword into the attack in a straight line.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/79|1|lbl=65.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>But when the enemy’s sword had been raised high, they gave the same opportunity to the enemy, so that he might be attacked. And this they did with certain cuts of the sword with the weapon accompanied, and united, with the same movement of the body with the right hand, or with the left hand; and attacking the enemy they at that time either bound the enemy’s sword with a ''molinello'', and attacked with the dagger; or attacked by putting at that tempo of his sword in a straight line.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/79|2|lbl=65.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>It has also been customary, in order to distract this straight line from its posture, to make feints, either from inside, or from outside with points, or with cuts, in order to frighten that person, who finds himself with his sword ''in presentia'':<ref>‘''in presentia''’ means the sword is on the line of engagement. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí]</ref> so that, coming out of the line with his sword to parry, you would give him a place where he could put his sword into the enemy’s hand. But these people who make these feints first make a mistake in order to make the enemy make another one: which mistakes are then paid for by the loss of life.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/79|3|lbl=65.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/80|1|lbl=66.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And because he who finds himself in this posture, with every little movement will always maintain the said advantage, if he will always keep the point of his sword fixed in the right shoulder of the enemy; and wherever he will go he will follow it with the said vain hope. Hence many imagined not to retreat from that sword, pressing its weak point, but to overshadow it with their own; and so that they might have some distance to attack, they did so with the short foot in front: and they had to put their foot on the right side of the enemy’s foot, and the sword extended in a straight line to the level of the enemy; and having arrived at a distance, and with the right foot, increasing their wound.<ref>This explains the advantages of Ghisliero’s guard position, demonstrating that the guard is the foundation of a fencing system. [note by Henry Fox]</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/80|2|lbl=66.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>However, if he places himself in this line, if he makes a single movement with his right foot, he will injure the enemy: because when he is pursued by the enemy, he can be attacked by the ''punta scavizzata''<ref>''Punta scavizzata'' means hollow point.</ref> as it is called by these fencing masters, or by the ''gobba'';<ref>''Gobba'' means hump or hunchback.</ref> and when we provoke him from within, he can be attacked by the ''punta riversa'',<ref>''Puinta riversa'' is a spelling variation from ''punta riversa''.</ref> or by the ''incapocchiato''.<ref>''Incapocchiato'' does not translate, it suggests the word incapacitate. ''Incapocchiársi'' means ‘to become a doult or logger-head, to take a foolish conceite’ (Florio 1611) It might also mean encompassing in modern Italian.</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/80|3|lbl=66.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Others have based their actions on offense and defense, and have proceeded in various ways; or while the enemy is on guard, they have tried to make a strong blow with a cut, or a thrust, in order to provoke the enemy; so that by disconcerting themselves with the parry, or with the attack, they can parry and then attack.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/80|4|lbl=66.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/81|1|lbl=67.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>That is to say, when they found the sword present, they disconcerted it, either by beating it in its weakness with the true edge at the bottom, or with the false edge from the bottom upwards: so that they could attack at that time: in which way the parries, and attacks are reduced indefinitely: as can be seen in the books which have dealt with this.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/81|2|lbl=67.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Those who give an uncovered place do so in order to give the enemy an opportunity to attack, so that he may parry and attack; but the feints do great harm to them, and beyond that the same method is reduced indefinitely.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/81|3|lbl=67.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''B'''ut we, in order not to incur in these kinds of offences and defences, will not take care to put our sword in a straight line, nor, since there is that of the enemy, will we attempt to draw it in the said terms: on the contrary, we will act according to due reason. And because true science consists in knowing the causes of things; which, once known and removed, the effect is also removed, we shall consider the cause of such a line; which is the point of the enemy’s shoulder, and the point of our body at which the line is aimed: and each time the point of the line is removed from the extremity of our body, the effect of the line is consequently removed.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/81|4|lbl=67.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/82|1|lbl=68.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And this point can be recovered in two ways:</p> | ||

| + | * in the first, by not losing ground; and with the transversal path by going out or to the left; | ||

| + | * in the other, when ground is lost by retreating a step, and by striking the same point. | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/82|2|lbl=68.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>To take the point out of the straight line is done in this way; that is to say, having divided the body into two parts equal to the diameter of our circle, in each part we constitute a point; and of our own free will we place one of them at the extremity of the line; or the enemy is the one who places his sword in one of them. And when of our own free we place it, it will always be the right one, in order to make the attack easier and more comfortable: because in this way we will gain a certain amount of ground.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/82|3|lbl=68.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>When the enemy is the one who puts his sword into one of our two points, if by chance he puts it on the right side, we shall come out with the left foot; if on the left side, we shall come out with the right foot, so that by doing so we remove the effect of the enemy’s line.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/82|4|lbl=68.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In addition to annulling the enemy’s line, the re-movement of the forearm creates for us another line, in which, by drawing our sword, we can attack; and in this way our body salutes us, which, by running away from the first attacks...</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/82|5|lbl=68.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/83|1|lbl=69.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>...on our straight sides, will then withdraw them with a step backwards; and at the same time we will attack his arm: but attacking it on our left side, we will lose the ground with our left foot, and at that time we will attack. But we do not make use of this method, since we could operate in a better way.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/83|2|lbl=69.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 11.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| + | | <p>And since every kind of cause and every kind of object can be considered at times to be in the power of production, and at other times to be in action, so we will consider that line to be in action when it will not be there, but it will be capable of coming to us, since all lines in whatever kind of position they may be, are attacked in a straight line, as can be seen in these figures which follow.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/83|3|lbl=69.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>'''W'''e will distinguish, therefore, that our opponent will either be in one of two states, that is, at rest, or if he departs from that state, he will be in motion.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/85|1|lbl=71.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>While he is at rest, he will keep his sword in a straight line (that is, he will bring it forth) or, having it outside the said line, he will keep it in force [power, strength] to be ready to put it in said line.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/85|2|lbl=71.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>When he holds the sword in production (that is, in the straight line) we must consider that, in accordance with the opening of his compasses, the sword will come to the point of the straight shoulder, and consequently the point of our surface will be on the right side of that line: this line will always be called straight, until it reaches the right side of the center of our body.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/85|3|lbl=71.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>While our enemy holds his sword in power to put it in a straight line, it will be called an oblique line; which will either be in front (that is, in the presence) or behind (outside the presence).</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/85|4|lbl=71.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>The sword will be said to be oblique in presence in three ways:</p> | ||

| + | * In the first, when it is present in the diameter of our circle, but then lies below the center of our body. | ||

| + | * In the second, the enemy sword will be said to be oblique to our body when both are within the diameter of the circle of distance; and the point of the enemy sword will be outside our body, either high, low, or in whatever kind of proportion we wish: this will be the case when we hold the sword’s fist against its fingers or hands. | ||

| + | * In the third, the opposite sword is oblique to our body, while it forms an angle with the arm, and the point of the sword exceeds the center of our body. | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/85|5|lbl=71.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/86|1|lbl=72.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Outside the present, or behind, the enemy can hold his sword in two ways: either with his right foot forward, or with his left foot. With his right foot he will hold it either low and collected, or high and in the act of striking a blow. When he holds it with his left foot forward, he will either hold it high in a ''guardia di falcone'',<ref>''Guardia di falcone'' means "falcon’s guard". This is what the Bolognese authors call ''guardia alta''. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí]</ref> or low in a guard called by many ''coda lunga e larga''.<ref>''Coda longa, & larga'' or ''coda lunga e larga'' means "long and broad tail guard".</ref></p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/86|2|lbl=72.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And all these lines can be placed in an infinite number of proportions: and therefore it has come about that so many guards have been formed, because from all the principles of the attacks, from all their means, and from all their ends, postures can be formed. But so that we may not be confused, we shall refer only to these proportions, which we have said, in which the enemy will necessarily find himself: it doesn’t much matter whether they are a little higher or a little lower.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/86|3|lbl=72.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''R'''eturning now to the declaration of our art, I say that when the enemy finds himself in any kind of tranquillity in his posture, we must, in order to operate with knowledge, consider the four causes which cause the effects: first of all, the efficient cause, which is man; and this is the most general and remote cause in the action of this posture; but the most propitious and particular will be the act in which man finds himself; and this act shows us the effect which can arise from it.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/87|1|lbl=73.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>The formal cause, which is motion in general from its stillness, denotes to us the measure of the particular motion, which is to bring it into effect.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/87|2|lbl=73.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>The formal cause, which is the proportion of the enemy sword, reveals to us the effect of its attack.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/87|3|lbl=73.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>I want the final cause to be the one that we consider in this effect around the line of the sword, which in attacking has the purpose of striking our body. But the final cause will be the point on our surface.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/87|4|lbl=73.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And if the enemy finds himself with his sword in a straight line, but subjected to our dagger, as if he were on guard three and four, then, beating that line, and at the same time attacking, we will put our sword in a straight line: but with the sword alone we will come out with the short foot, attacking.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/87|5|lbl=73.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/88|1|lbl=74.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>While the enemy will hold his sword against us in a straight line, in a state of straight foot, or short foot in front, as in guarding the head, or in front of the face, or with the right foot in front of the head in a first and second guard, we will keep as a rule the rule of going out of that straight foot with transversal movement.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/88|2|lbl=74.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>When the enemy’s sword is oblique to our body, that is to say, in its first position under the center of our body, we must strike with our left foot in the same position, in order to ''scanso del corpo'',<ref>scanso del corpo means void the body. Basically, these are the body turns we use to take the body off the line of engagement. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí]</ref> and here I am speaking only of the sword, because if we have the dagger, we will place it in the imagined line, and we will strike in our usual manner.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/88|3|lbl=74.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If the enemy’s sword is oblique to our body in the second way (in this case we will see the body of the sword and not its point) we will always gain on our right hand, and escaping that length, and attacking, we will place our sword on the diagonal.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/88|4|lbl=74.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>But if the sword is oblique in the third way, we must distinguish that if the point of the angular line is at the right of our straight point, then we will act against it as if it were in a straight line; but if it were with the tip of the sword in the chest at our short point, we will cut it off, driving our sword in a straight line into the wound.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/88|5|lbl=74.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/89|1|lbl=75.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | class="noline" | | ||

| + | | class="noline" | <p>In the event that our opponent should hold his sword backwards, or in a fury of presence, with his foot straight forward, as some do when they hold their swords together in order to make the ''inquartata'':<ref>''Inquartata'' means quartering step. It is a voiding action of the body which closes the inside line.</ref> or when they are in ''guardia alta in coda lunga e larga''; or with their foot short forward in a ''guardia di falcone''; or in a ''coda lunga'';<ref>“Long and high tail” guard.</ref> And even if it is finally in any kind of proportion, even if it is out of the present; we will always take care to fight with the body; and we will try to move it with our straight sides, since it is (as Aristotle says) natural to all animals.</p> | ||

| + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/89|2|lbl=75.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Chapter 10 | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>''Now, since we have declared the proportions of the lines when they are still, we will say of those that are in motion.''</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/89|3|lbl=75.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''W'''e must therefore consider that they depart from one stillness and come to rest in another:<ref>The sequence of the combatant should always be ward – blow – ward, or stillness – motion – stillness, it is a common and practical method in quite a few treatises. [note from Henry Fox]</ref> for all attacks depart from the center of the shoulder, which is the origin of the straight line; and in the attack they also return to said center.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/89|4|lbl=75.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Because all the motions of a attacked man are mixed; since, for example, in order to make a hit, it is necessary first of all to make a circular motion in order to cause a straight line, and likewise because man, in forming a attack, does so with violent and natural motion (but violent is of greater force than natural), we shall distinguish that motion has a beginning, middle and end.<ref>Examine di Grassi’s (Grassi, 1570) diagram of the thrust and movement of the arm for an example of this motion. [note from Henry Fox]</ref></p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/89|5|lbl=75.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/90|1|lbl=76.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And in order that this treatise may be better understood, I, in this part which follows, postpone the oblique and violent movement which a man makes when he prepares his arm and brings it up and rests it in the state to make a cut or point, if it is time to attack his enemy. However, I intend to speak of the movement that is made when the arm, departing from that stillness, moves towards the attack; and this is that which is (as we have said) composed of violent and natural movement; violent with respect to the force of the moving force, which pushes and violates that weight as it descends; and natural with respect to the weight of the arm and of the sword, which by its nature tends towards the center of the earth.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/90|2|lbl=76.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||