|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Federico Ghisliero"

(→Temp) |

|||

| (25 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| language = [[Italian]] | | language = [[Italian]] | ||

| − | | nationality = | + | | nationality = |

| ethnicity = | | ethnicity = | ||

| − | | citizenship = | + | | citizenship = Bologna |

| education = | | education = | ||

| alma_mater = | | alma_mater = | ||

| − | | patron = | + | | patron = |

| period = | | period = | ||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

| notableworks = ''[[Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero)|Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii]]'' (1587) | | notableworks = ''[[Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero)|Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii]]'' (1587) | ||

| manuscript(s) = | | manuscript(s) = | ||

| + | | translations = {{English translation|https://msmallridge.files.wordpress.com/2023/07/ghisliero-1587-rules-of-many-knightly-exercises.pdf}} | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | Federico Ghisliero was a Bolognese soldier and fencer. Little is know about his early life, but he studied fencing under the famous [[Silvio Piccolomini]]. | + | Federico Ghisliero was a Bolognese soldier and fencer. Little is know about his early life, but he came from a Bolognese family and studied fencing under the famous [[Silvio Piccolomini]].{{cn}} He lead a long military career that included serving under the famous commander Alessandro, Duke of Parma, in Flanders in 1582. He was also a frind of Galileo Galilei and a prolific writer, though unfortunately most of his writings were destroyed in a fire at the University of Turin in 1904.<ref name="Anglo 30">Anglo 1996, p. 30.</ref> |

| − | In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called ''[[Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero)|Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii]]'', dedicated to Ranuccio Farnese, who was 18 years old at the time | + | In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called ''[[Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero)|Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii]]'' ("Rules for Many Knightly Exercises"); two versions of the first edition exist, and it's unclear which was created first. One is dedicated to dedicated to Antonio Pio Bonello, a well-known soldier and distance relative, and the other to Ranuccio Farnese, who was 18 years old at the time and Alessandro's heir.<ref name="Anglo 30"/> |

| + | |||

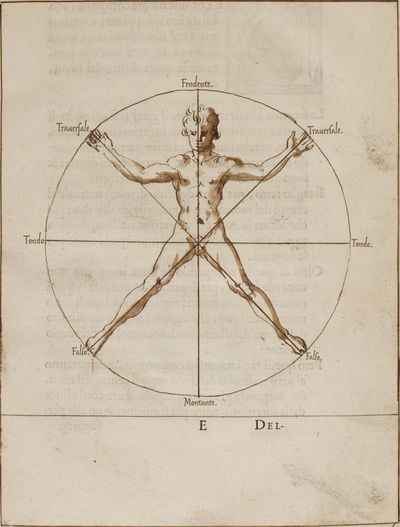

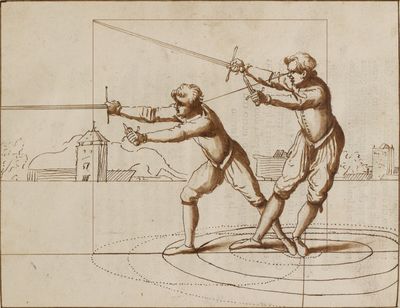

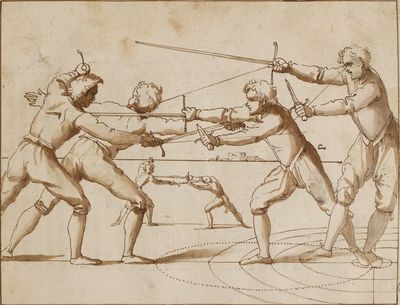

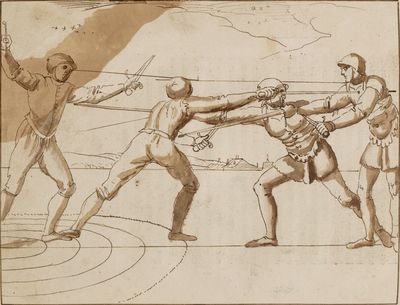

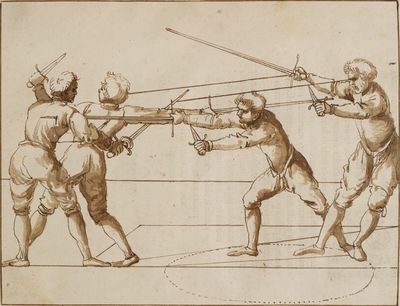

| + | Ghisliero's treatise is notable for his use of geometry in relation to fencing, using concentric circles centered on where the fencer has placed most of their weight (often, but not always, the back foot), and sometimes including multiple versions of each figure in an illustration to show the progression of the movements he describes. He also seems to be the first author to include a Vitruvian Man in a fencing treatise.<ref>Gotti 2023, pp. 130-133.</ref> However, his treatise is unique in that it was printed without any illustrations at all, and they had to be drawn in by hand. It's unclear whether this indicates that he intended to have printing plates made but was unable to do so, or that his plan from the start was to have the books vary based on how much art each buyer was willing to pay for. | ||

{{TOC limit|3}} | {{TOC limit|3}} | ||

== Treatise == | == Treatise == | ||

| Line 41: | Line 44: | ||

! <p>Images</p> | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| − | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[ | + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 81: | Line 84: | ||

! <p>Images</p> | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| − | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[ | + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 817: | Line 820: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="4" | [[File:Ghisliero 06'.jpg|400px|center | + | | rowspan="4" | [[File:Ghisliero 06''.jpg|400px|center]] |

| <p>Of these three natures of the cut,</p> | | <p>Of these three natures of the cut,</p> | ||

* the first is the ''fendente'',<ref>''Fendente'' means vertical cut.</ref> | * the first is the ''fendente'',<ref>''Fendente'' means vertical cut.</ref> | ||

| Line 823: | Line 826: | ||

* the third the ''tondo''.<ref>''Tondo'' – horizontal cut</ref> | * the third the ''tondo''.<ref>''Tondo'' – horizontal cut</ref> | ||

| − | <p>And all these three natures are divided into ''dritti''<ref>''Dritti'' – straight/forward [forehand cut, or natural cut, sometimes called ''mandritta''] [note from Henry Fox]</ref> and ''roversi'';<ref>''Roversi'' – reverse [backhand or cross-wise cut] [note from Henry Fox]</ref> the ''dritti'' are those which come from the lesser side. And these ''dritti'' and ''roversi'' divide the circle of man into eight equal parts, as can be seen in the figure below.<ref>The division for the cuts on most diagrams usually go through the navel, or heart rather than the groin in most treatise of the period. [note from Henry Fox] [[Gérard Thibault d'Anvers]]’ 1630 treatise ''[[Academie de l'Espée (Gérard Thibault d'Anvers)|Academie de l'Espée]]'' ‘Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 2 – Comparing the ideal figure to a real Figure; Sword Scabbards’ shows the division at the naval (d'Anvers, ''Academie de l'Espée'', 1630) – in the text it is found in the section that begins ''Pour venir à la Pratique de tout ce qui a efté discouru'', or “To come to the Practice of all that has been discussed” (d'Anvers, ''Academie de l'Espée'' – Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 1 – Philosophical Discussion; Construction and Mathematics of the Circle; Concerning the Sword: Proper Length and Introduction explanation of the first plate., 1630). [[Salvator Fabris | + | <p>And all these three natures are divided into ''dritti''<ref>''Dritti'' – straight/forward [forehand cut, or natural cut, sometimes called ''mandritta''] [note from Henry Fox]</ref> and ''roversi'';<ref>''Roversi'' – reverse [backhand or cross-wise cut] [note from Henry Fox]</ref> the ''dritti'' are those which come from the lesser side. And these ''dritti'' and ''roversi'' divide the circle of man into eight equal parts, as can be seen in the figure below.<ref>The division for the cuts on most diagrams usually go through the navel, or heart rather than the groin in most treatise of the period. [note from Henry Fox] [[Gérard Thibault d'Anvers]]’ 1630 treatise ''[[Academie de l'Espée (Gérard Thibault d'Anvers)|Academie de l'Espée]]'' ‘Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 2 – Comparing the ideal figure to a real Figure; Sword Scabbards’ shows the division at the naval (d'Anvers, ''Academie de l'Espée'', 1630) – in the text it is found in the section that begins ''Pour venir à la Pratique de tout ce qui a efté discouru'', or “To come to the Practice of all that has been discussed” (d'Anvers, ''Academie de l'Espée'' – Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 1 – Philosophical Discussion; Construction and Mathematics of the Circle; Concerning the Sword: Proper Length and Introduction explanation of the first plate., 1630). [[Salvator Fabris]], in his 1606 text, ''[[Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Sienza e Pratica d’Arme]]'' also has an illustration in the section ''Discorso sopra laprima guardia formata nel cauare la spada del fodero'' or “Discourse in the first guard formed in pulling the sword from the scabbard” demonstrates the where cuts should be made and these also shows the division at the navel rather than the groin. (Fabris, 1606)</ref> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/46|3|lbl=32a.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/46|3|lbl=32a.3}} | ||

| Line 1,165: | Line 1,168: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Tempo is therefore the number, or rather the measure [distance] of the movement, according to the fact that two instants, one before and the other after, determine the movement of both parties. And there are three times, past, present, and future; of these we need not speak of the past.</p> | + | | <p>''Tempo'' is therefore the number, or rather the measure [distance] of the movement, according to the fact that two instants, one before and the other after, determine the movement of both parties. And there are three times, past, present, and future; of these we need not speak of the past.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/63|4|lbl=49.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/64|1|lbl=50.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/63|4|lbl=49.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/64|1|lbl=50.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,181: | Line 1,184: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Since, therefore, we have knowledge of time, we will have to operate in two ways: in the first (since motion is born of stillness) we will consider the nature of the stillness of the enemy’s sword: and the stillness likewise of the enemy’s state: for these will show us future motion; and consequently we will have knowledge of its measure [distance]; that is, of future time, called premeditated [''tempo''].<ref>Aristotelian motion is the consideration of “a stillness and motion” and is used by Capo Ferro as a method of reading the opponent in Chapter 5 ‘Of | + | | <p>Since, therefore, we have knowledge of time, we will have to operate in two ways: in the first (since motion is born of stillness) we will consider the nature of the stillness of the enemy’s sword: and the stillness likewise of the enemy’s state: for these will show us future motion; and consequently we will have knowledge of its measure [distance]; that is, of future time, called premeditated [''tempo''].<ref>Aristotelian motion is the consideration of “a stillness and motion” and is used by Capo Ferro as a method of reading the opponent in Chapter 5 ‘Of ''Tempo''’ (Cagli’, 1610) [note by Henry Fox]</ref></p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/64|4|lbl=50.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/65|1|lbl=51.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/64|4|lbl=50.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/65|1|lbl=51.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,425: | Line 1,428: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>But when the enemy’s sword had been raised high, they gave the same opportunity to the enemy, so that he might be attacked. And this they did with certain cuts of the sword with the weapon accompanied, and united, with the same movement of the body with the right hand, or with the left hand; and attacking the enemy they at that time either bound the enemy’s sword with a ''molinello'', and attacked with the dagger; or attacked by putting at that tempo of his sword in a straight line.</p> | + | | <p>But when the enemy’s sword had been raised high, they gave the same opportunity to the enemy, so that he might be attacked. And this they did with certain cuts of the sword with the weapon accompanied, and united, with the same movement of the body with the right hand, or with the left hand; and attacking the enemy they at that time either bound the enemy’s sword with a ''molinello'', and attacked with the dagger; or attacked by putting at that ''tempo'' of his sword in a straight line.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/79|2|lbl=65.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/79|2|lbl=65.2}} | ||

| Line 1,752: | Line 1,755: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>In the fourth and last, one parries all attacks by guarding the head; and this method is safer than the third, since it is not subject to deceptions; and with it one responds to that attack which is more comfortable, by receiving the blow in the first third of the sword, in the forte of the sword; then, gathering up the short foot in the parry, one prepares it for the right; one may attack either by cutting straight on or by cutting ''riverso''.</p> | + | | <p>In the fourth and last, one parries all attacks by guarding the head; and this method is safer than the third, since it is not subject to deceptions; and with it one responds to that attack which is more comfortable, by receiving the blow in the first third of the sword, in the ''forte'' of the sword; then, gathering up the short foot in the parry, one prepares it for the right; one may attack either by cutting straight on or by cutting ''riverso''.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/96|3|lbl=82.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/96|3|lbl=82.3}} | ||

| Line 1,788: | Line 1,791: | ||

|- | |- | ||

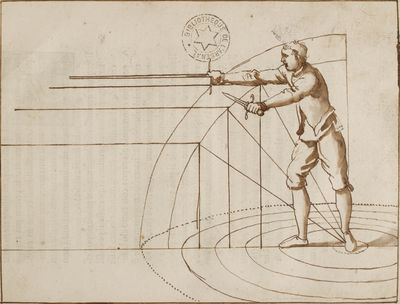

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 12'.jpg|400px|center | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 12''.jpg|400px|center]] |

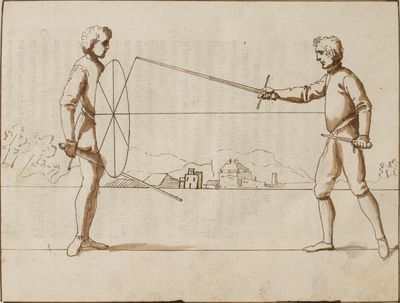

| <p>And since the sword, while it is in its natural state, denotes the future blow, we will place it in such a proportion that it will be able to make a single attack by the posture of the hand. It should therefore be placed in such a state that, when the body is in ''scurzo'' and the arm is raised in its natural state, the sword and arm form the same line with the body. So that when a line is drawn from the extreme point of the sword, a square figure is formed as shown by the posture.</p> | | <p>And since the sword, while it is in its natural state, denotes the future blow, we will place it in such a proportion that it will be able to make a single attack by the posture of the hand. It should therefore be placed in such a state that, when the body is in ''scurzo'' and the arm is raised in its natural state, the sword and arm form the same line with the body. So that when a line is drawn from the extreme point of the sword, a square figure is formed as shown by the posture.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/98|3|lbl=84.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/98|3|lbl=84.3}} | ||

| Line 2,054: | Line 2,057: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | < | + | | <p>Therefore, we will always keep our sword at the enemy’s side, and we will attack them with ''imbroccata aventata''<ref>''Imbroccata aventata'' means a hurling or forceful thrust given over the dagger.</ref> from above and below.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/116|3|lbl=102.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/116|3|lbl=102.3}} | ||

| Line 2,213: | Line 2,216: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

| − | | <p>''The end of the Theory.''</p> | + | | class="noline" | <p>''The end of the Theory.''</p> |

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/122|5|lbl=108.5}} | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/122|5|lbl=108.5}} |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,221: | Line 2,224: | ||

{{master end}} | {{master end}} | ||

| − | |||

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| title = Practice | | title = Practice | ||

| Line 2,238: | Line 2,240: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>'''On the Practice'''</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>''Our practice can be reduced to a few things, because by our action we negate all the principles of the various offenses that can be made.''</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/123|1|lbl=109.1}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/123|1|lbl=109.1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>'''T'''herefore, as soon as the enemy is seen from afar, the cloak should be dropped from the straight shoulder, and the dagger should be thrust forward on the straight flank with the left hand. Then, first, the sword will be drawn from the scabbard, and then the dagger, and at the same time the fists and teeth will be clenched and the eyes widened, showing prideful expression.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/123|2|lbl=109.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/123|2|lbl=109.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>After this, with the lowered arms thrust out from the body, and with natural steps we shall walk; and before we reach the distance we shall acknowledge the enemy; and we shall beware with which foot he comes forward, and with which weapon: for if he holds his dagger forward, this will be to defend himself; if his sword, to attack; however, if he does so in whatever way we choose, it will always be we who will decide and and give him the motion.<p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/123|3|lbl=109.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/123|3|lbl=109.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>And supposing that the enemy finds himself in a state with his sword in action in a straight line, but dominable by our dagger, as in the third and fourth guards, we shall place our body in perspective, and in the narrow position we shall enter into the first posture, in which, following the aforesaid rules, we shall be able to attack with a short stroke, and at the same time we shall be able to strike the enemy’s sword, and distort it from that line, helping it to decline.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/123|4|lbl=109.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/124|1|lbl=110.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/123|4|lbl=109.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/124|1|lbl=110.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 2,259: | Line 2,263: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>For if we consider the four causes which we have mentioned above, the first of which is the posture of the body, we can be certain that the body in motion can come in a straight line, and the proportions of the sword, the formal cause, show us that the attack is in a straight line. The material cause shows us that any other kind of movement that the enemy makes, either with his body or with his arm, either by pushing, or by retreating, or by bearing, or by turning, will be made in a longer ''tempo'' than would be the movement indicated by the posture; the final cause, which is the extreme point of that line, is now removed from the dagger, because the dagger, by beating, takes it away from its position.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/124|2|lbl=110.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/124|2|lbl=110.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>And in order that man may not be confused or mistaken, we must know that all the rules we have stated apply equally to the game of the sword and dagger as to that of the single sword: but they differ only in this: that when we have the dagger, and fight against straight lines, which are present, but subject to our dagger, then it is not necessary for us to take out the points, which are the final causes of these lines; for with the dagger we remove the effect of the attack by striking them.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/124|3|lbl=110.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|1|lbl=111.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/124|3|lbl=110.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|1|lbl=111.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 2,270: | Line 2,274: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>But with the sword alone, which is devoid of such a defense, when we fight against these proportions of lines, we will always be attacked, and we will do so with our left foot, since we need to remove the point with the movement of our body; since we do not have the dagger: and with our left hand we will close the return to the enemy’s sword, as shown by the two small figures in this first demonstration, which will follow below.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|2|lbl=111.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|2|lbl=111.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>And with the straight lines, in high ''fresentia'',<ref>No translation of this word is available.</ref> with the accompanying weapons and with the sword alone, we will operate in the same way.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|3|lbl=111.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|3|lbl=111.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>When fighting against oblique lines, we shall follow the same order: and only we shall differ in this, that with the sword alone, when we are attacked by necessity; that is, at the time when the enemy is attacking us, we shall do so in a straight line, with the body in profile.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|4|lbl=111.4}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|4|lbl=111.4}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | [[File:Ghisliero 16.jpg|400px|center]] |

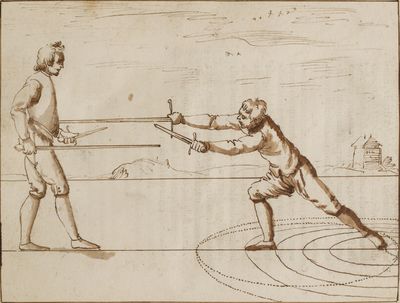

| − | | | + | | <p>And returning to the declaration of the Practice, I say that if we find the enemy in the third or fourth guard, either with his legs open or closed, we will present ourselves to him in perspective, and by placing ourselves in first guard with the foot not even in the diameter of the circle, immediately after our sight passes through the ''forte'' of our dagger and attacks the ''debole'' of the enemy’s sword, we will resolutely attack the right side of the sword in ''tempo'': as is shown in this figure, which follows, in which, as in all the others, it is only the guard with his dagger, which is made of will ahead of time: and there is also a certain line drawn from the fist of our posture, which signifies the attacking of necessity in time; that is, the manner of attacking, when the enemy attacks; furthermore that line, which arises from the fist of the opposite, denotes the first posture of the sword of the same enemy.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|5|lbl=111.5|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf|126|lbl=112|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/125|5|lbl=111.5|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf|126|lbl=112|p=1}} | ||

| Line 2,291: | Line 2,295: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>I will not hesitate to say that if our enemy was in a state with a straight line in front of him, but well extended, (as many do to keep the enemy at a distance), then we would strike that parried sword with the dagger, describing a semi-circle outwards with it, so that more length could be extracted from our body in the attack.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/128|1|lbl=114.1}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/128|1|lbl=114.1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>Whenever our opponent is placed in</p> |

| + | * the first or second guard, or | ||

| + | * the guard against the face, or | ||

| + | * in the entrance guard, | ||

| + | <p>the sword will be placed high up in a straight line. We will act against it in this way; we shall place our body in perspective in the first circle, and putting our foot straight ahead in the diameter of the circle, we shall of our own free will oppose the straight point, and with our left hand we shall move out of the circle into the second circle. We shall attack by striking with our dagger using the second guard either in ''tempo'' or ahead of ''tempo''.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/128|2|lbl=114.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/128|2|lbl=114.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>And there are three things that could make this contrary operation of ours possible;</p> |

| + | * the first is that in the appearance that we make, he could end up walking along that line attacking us, but we will attack him in the premeditated ''tempo''; | ||

| + | * the second is that he could attack us in the movement that we make, when we went out with the point of attacking us: which is not for knowledge; because our movement is of short duration: so that we will have acted first, before he has seen it. | ||

| + | * the third is that he may retreat when we strike the blow in perspective: his retreat will not be so great as our growth, since we are moving together; and in this case we shall attack as we usually do with a forward thrust. | ||

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/128|3|lbl=114.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/129|1|lbl=115.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/128|3|lbl=114.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/129|1|lbl=115.1|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 17.jpg|400px|center]] |

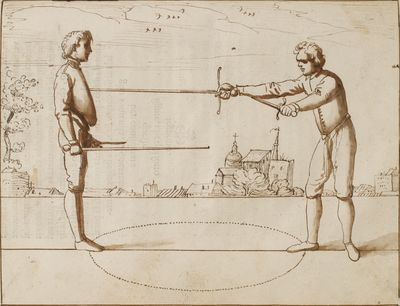

| − | | | + | | <p>If the enemy changes his guard after the man arrives in the straight, the manner in which he is to be placed will determine how we will proceed against him in accordance with the above rules.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/129|2|lbl=115.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/129|2|lbl=115.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>I have wished to give these few reasons for greater intelligence. It may not be necessary, because all the figures which are to be shown below are based on all the said rules, and this one, which now follows, demonstrates the effect of the second guard, and that line which comes out of the enemy’s shoulder, which signifies the proportion of the sword to the opposite, in which it is supposed to be.</p> |

| − | |||

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/129|3|lbl=115.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/129|3|lbl=115.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>If the enemy were to be placed in the same guards, but would keep his sword fixed on our left-hand point, we would immediately place our left foot of the same diameter as the right foot that held the enemy in front of us, and then, coming out with our right foot in a transversal movement in the second circle, we would form the third guard, and from above to below we would strike with our cross, leaving the defence to be carried out naturally by our left arm, as if it were one piece, with both hand and dagger.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/131|1|lbl=117.1}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/131|1|lbl=117.1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 18.jpg|400px|center]] |

| − | | | + | | <p>The enemy, when we go to attack, could change his sword underneath; but only by bringing the weight of the body back to the missing<ref>''Manca'' means missing, and probably means back or voided leg.</ref> leg, and with that alone making a small movement, will he beat that sword, and make the same attack.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/131|2|lbl=117.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/131|2|lbl=117.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>I will not repeat all the reasons, because what has been said of the first guard is also meant to be said of all the straight lines: it is sufficient that these figures demonstrate the effect, as does this one below, which demonstrates how it is done by being attacked before ''tempo'' and in ''tempo''.</p> |

| − | |||

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/131|3|lbl=117.3}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/131|3|lbl=117.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | [[File:Ghisliero 19.jpg|400px|center]] |

| − | | | + | | <p>But when the enemy has his sword in preference,<ref>This probably means that the sword has mechanical advantage in a thrusting position.</ref> but obliquely under the center of our body, we will then appear in the united state, and with the body well protected in the first guard, opposing the dagger, a body is resistant to the oblique line, so that it does not rise, we will choose the best attack possible that can be made. But we must prepare ourselves against all the danger that lies in the fact we are approaching the dagger when we strike it, and therefore, with the premeditated ''tempo'' (since the oblique line cannot be used in a short time for anything other than a straight line), we will place our dagger on the imaginary line, on which the sword must fall, and this imagined line appears below in this figure.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf|133|lbl=119|p=1}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf|133|lbl=119|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | [[File:Ghisliero 20.jpg|400px|center]] |

| − | | | + | | <p>If the enemy were to hold his sword obliquely in the second way, we would immediately, after having reached the diameter (with the body in perspective) enter the smallest circle of distance. [The smallest circle] is marked with dots, as is the other small circle which we also form in the state. And placing our feet on the cord<ref>''Corda'' means rope or cord, but in this context means the diameter of the circle.</ref> of the said large circle we would form the first guard: that thus gaining the distance (in case he attacks). We shall likewise attack, by placing our sword in the diagonal and our dagger in the imagined line; in which that sword must come obliquely, as this figure shows very well, in which we see the effect which our attack makes; and the effect which the enemy’s attack makes.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf|135|lbl=121|p=1}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf|135|lbl=121|p=1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | [[File:Ghisliero 21.jpg|400px|center]] |

| − | | | + | | <p>The opposite of ours may be found with the sword oblique to our body, in the third way, as has been said of the sword. That is to say, angular, but we shall have ascertained if the extremity of the sword is at the right angle to our left parts; and immediately on arriving at the distance we shall place ourselves in the fourth guard. And we shall attack with the greatest length of the body; moving it first; and then following the movement with the right foot we shall cut that line and we shall help it with the dagger to its circumference. We are certain that the sword, being in this angle, will be able to make a straight line, and that we, by carrying the weight of the body to the missing leg, will overcome it by attacking it on first guard. If, when we appear, the same angular line is made straight, we will return to the first circle on first guard, and we will operate as we have said, on first guard.</p> |

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/137|1|lbl=123.1}} | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/137|1|lbl=123.1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>But if the sword is at an angle, and it is placed on the right side of our straight sides, so that in such a position we see its body and not its point, we will go to the first guard, working against it as if it were a straight line.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/137|2|lbl=123.2}} | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/137|2|lbl=123.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | <p>The following figure shows very well the effect of the enemy and the effect of our posture.</p> |

| − | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/137|3|lbl=123.3}} | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/137|3|lbl=123.3}} |

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Chapter 16 | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | ! <p>Images</p> | |

| − | | | + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> |

| − | + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 22''''.jpg|400px|center]] |

| − | | | + | | <p>''Now that we have spoken of oblique lines in the present, it remains for us to come to the end of this treatise to discuss those lines, which will be found outside of the present, since the enemy can retreat into them in two ways, either with his right foot forward or with his left.''</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/139|1|lbl=125.1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>Since we have no intention of attacking our enemy every time that he holds his sword in the rear, the same facilitates our work. And we will keep as a rule that we must spread out from the enemy’s sword as far as it is from us and in doing so we will seek out the enemy’s body, and keeping the body in the rear, we will go out into the smallest part of the circle, and staying in the cord of the said circle, we will attack in front of the ''tempo'' and in ''tempo'' in the same way – as appears here in this figure which follows.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/139|2|lbl=125.2}} |

| − | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 23.jpg|400px|center]] |

| − | | | + | | <p>Finally, when the enemy returns to his stationary position with his left foot forward, in this posture he concedes only one point of his surface. However, when he wishes to attack, he must pass with the whole perspective of his body into the attack and this he will do with the greatest possible movement: which will be described in the ''tempo'' of a maxim, which is eight strokes. We shall therefore enter into the distance, placing ourselves in the lesser position to first guard our life, which will be closer to the profile than otherwise; and we shall hold the dagger high if the enemy is on falcon guard.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/141|1|lbl=127.1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>While we are doing this, we will move the enemy. We will</p> |

| − | | | + | * take out the point |

| − | | | + | * gain distance |

| + | * bring our sword closer to the enemy and | ||

| + | * with the dagger ready, which we will hold in such a way that it will dominate the sword, we will attack the enemy either in front of the point or in the point. | ||

| + | <p>In order that this chapter may be better understood, I have divided it and made two demonstrations, of which the first shows that when we attack with the will, then we no longer use our usual attack, but we do so with the body in profile, as we see in the following figure, and we attack the left parts.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/141|2|lbl=127.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | rowspan="3" | [[File:Ghisliero 24'.jpg|400px|center]] |

| − | | | + | | <p>Whenever we give motion to these, which are in a state of being with the left foot in front, they force themselves to adapt; because by raising the point we cover ourselves behind the line of their body: so that, not discovering a place where they can attack, they move. Therefore it will be time to attack them in that movement, either of the right foot or of the left.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/143|1|lbl=129.1}} |

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>But if they want to attack, we will, with our usual parry and attack, attack them on the straight side, which is the one that leads to attack, as we see in the following figure.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/143|2|lbl=129.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>All these things, which have been said, we must know how to reproduce, according to need. For if the enemy (for example) can put himself:</p> |

| − | | | + | * on guard to enter and then lower that line, and |

| − | | | + | * after that release it, and |

| + | * put it in an oblique line | ||

| + | <p>he will likewise be able to put it from one into another proportion. Therefore, by observing these rules, from one guard we will enter the other with great ease.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/145|1|lbl=131.1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>So far these considerations have made it clear that being on guard is very harmful. It follows, therefore, that in all our actions we must never give any indication of our will. But we must be resolute enough to place the dagger in the straight line we have imagined and with one stroke attack, either with the point, which will be a forward thrust, or with a slashing cut, with all our strength and length - making it necessary for the enemy to parry. We shall then immediately strike back with a cross-cut, aided by the force of the dagger, after which we shall again begin the first attack; and this cross-cut we shall make standing in the first opening, in step with the force we have used in the attack. But if the enemy loses ground through our first attack, we shall make this cross-cut, increasing with the left foot.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/145|2|lbl=131.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>And this way of doing things will be followed, provided that the distance and the attacking are one and the same.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/146|1|lbl=132.1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | |

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | <p>By putting this resolutely and swiftly, the enemy becomes occupied in defence and moreover he loses his counsel and his spirit, and consequently his strength. From this it is clearly seen that he will put himself in defence or will use some kind of involuntary attack - which are attacks made by necessity. Since we will be the one who forces him to act against his will we will easily resist [his attack] and this all the more so the more they are seen to be weak and imperfect.</p> |

| − | | | + | | class="noline" | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/146|2|lbl=132.2}} |

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Chapter 17 - Advertisements of the Sword and Dagger | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>'''ADVERTISEMENTS''' OF THE SWORD <small>AND DAGGER</small></p> |

| − | | | + | |

| + | <p>''If we want to use our first guard, there are five ways in which we could go against this posture: but all will be in vain if we operate according to reason and the knowledge of the weapon.''</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/147|1|lbl=133.1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | | <p>In the first way, he will try to approach from a distance, and with speed he will move his sword across, in order to attack with his dagger. But this is remedied by attacking the enemy in motion, before he reaches the distance. In addition, with every little movement we raise our sword, we will put it into the attack in a straight line. Moreover, we shall pass with our left foot and attack with our dagger.</p> |

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/147|2|lbl=133.2}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>In the second way, he will study the opposite of going to the sword, in order to attack with the reversed blow: but this is remedied by centring with the right foot: because in this way he will not be allowed to approach: so that in those movements we will be able to attack him; and supposing that he were to dig out the reversed attack, we will drive our sword in a straight line, with the body in profile, thus cutting that line.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | | + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/147|3|lbl=133.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/148|1|lbl=134.1|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>In the third way, with the low sword tilting, the apposite will be done by the ''inquartata'': and therefore we will move tilting above; and with the dagger we will hold back the sword so that it does not rise.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/148|2|lbl=134.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>In the fourth way, he will do the opposite, flowing up the sword by the middle, not to attack, but to drive out the ''punta riversa'', which is remedied in the same way.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/148|3|lbl=134.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| + | | <p>In the fifth way, he will put the point of the sword in his fist to prevent it from descending. We will not allow this if we are attacked immediately after the enemy’s sword reaches our body, but if we assume that the sword is already in our fist, we will make a little sign of retreat with the fist of the sword alone, because if he puts the sword back in that motion we will attack him.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/148|4|lbl=134.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If, in presenting himself, a man is deceived or disconcerted, he must withdraw by drawing a circular slash which cleaves the ground: and then, having recognized himself, he must recover.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/148|5|lbl=134.5}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>When the sword is impeded, one must yield to that force; and attack by that movement which the same force causes to be made, and this way of operating in arms is most perfect.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/148|6|lbl=134.6}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If the enemy counterattacks, we must also counterattack, and hence the latter has the advantage.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/148|7|lbl=134.7}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Since it is possible to attack with four fingers of the sword, we do not want or need to overdo it: because the first attack must be made while fleeing, especially when the enemy has a dagger.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/149|1|lbl=135.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In all attacks, the length of the body should be taken first, and then the movement of the feet should be added; and care should be taken to ensure that the point is fast enough in reach to attack.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/149|2|lbl=135.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Each time the dagger parries our attacks, we will repeat the blows, which will help us to strike the dagger; that is, we will not violate our arm from its natural position.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/149|3|lbl=135.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Whenever we agree with our posture, if the enemy withdraws (which is mostly the case), we will lower our weapons and begin the fight again in the same way: and if we seem to be on our guard, we will reduce the enemy as much as we can, putting him in need.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/149|4|lbl=135.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Chapter 18 - Advertisements of the Single Sword | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''Advertisements of the single sword'''</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Whenever the sword is engaged, it can be freed by withdrawing the left foot to the rear, and if the other side attacks it, it will be attacked at the same time.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/150|1|lbl=136.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If, by pulling on an attack, we come to half a sword, we will free ours; if we hold it inward, we will pull it upward, piercing the attack: and with our left hand we will catch the opposite sword in its hilt. But if we have it on the other side, we will take it out from underneath, drawing it into the angle formed by the two swords with our left arm crossed in defense; and we will attack with the point of the sword’s fist<ref>‘A reference to the ‘sword fist’ is made in [[Antonio Manciolino]]’s Opera Nova where it states “Of the narrow iron gate guard. The sixth guard is called “porta di ferro stretta”. In which the body must be arranged diagonally in such fashion that the right shoulder (as is said above) faces the enemy, but both the arms must be stretched out to encounter the enemy, so that the sword arm is extended straight down in the defense of the right knee, and so that the sword fist be near and centered on the aforesaid knee.” (Wiktenauer, 2022) It is then clear that ‘sword’s fist’ means the hand holding the hilt of the sword.</ref> upwards.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/150|2|lbl=136.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Chapter 19 - Treatise on the Sword and Cloak | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>'''Treatise on the sword and cloak'''<ref>''Cappa'' means both cloak and cape (there is no differentiation in Italian). I will use cloak for the purpose of consistency. The Spanish cloak or cape is short compared with what we normally consider to be a cloak. It is usually worn anywhere from below the shoulder blade length to the hip.</ref></p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>When we use the cloak for defense, we must always remember that it differs from the dagger in that it can be cut and pierced, which is not the case with the dagger, and therefore we will never parry with the cloak in the same way as with the dagger. And just as the dagger cannot be used to parry stabbings, so the cloak cannot be used to parry them. And since we try to keep the dagger free from injury, the cloak cannot be kept in the hands of the enemy.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/151|1|lbl=137.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>All the same reasons, and all the ways, which we have said above of the single sword, and of the sword accompanied by the dagger, serve us with the sword and cloak: and of this there is no other use, than to impede the enemy; so that he | ||

| + | may not have so easy an attack; and to cover the parts below.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/151|2|lbl=137.2|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/152|1|lbl=138.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And yes, as we close the return of the enemy sword with the hand at this time when we are attacked by the points, so with the cloak we can better achieve our goal.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/152|2|lbl=138.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And because when the man is without a cloak he can be harmed and defended against in two ways: one is to throw it [the cloak] into his face and the other is to throw it over his sword at its ''debole''; this [latter] is an easier way than the first. Therefore it [the cloak] will be taken with the flat hand and with the thumb only; and with a semicircular outward movement it will be collected in the fist, and united a man can take advantage of it at his pleasure and also deprive himself of it in order to come to grips with it.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/152|3|lbl=138.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Hence it may be understood that the same order must be followed in drawing the sword, and in turning the cloak into the fist, as is done with the sword and dagger, and that this must be done without giving the enemy any idea of his [the man’s] own will. This is to be done by proceeding with the sword down and the cloak out from the body, with caution, and distinguishing what the enemy will do, who, either stationary or in motion, will have to take advantage of it.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/152|4|lbl=138.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If the contrary is found to be the case, it will necessarily be in one of the acts, which we have already mentioned, but against those we will use one of those offenses, which we have declared above.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/152|5|lbl=138.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/153|1|lbl=139.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And if the same opponent holds his sword in front of him, we shall fight against him in the manner already indicated, but holding his cloak in front of him, we shall always use our natural motion with our straight hand; with cuts and points we shall nevertheless attack that fist facing away from the cloak and away from the enemy’s sword.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/153|2|lbl=139.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If, however, we find our opponent in motion, we shall act against him in accordance with the proportions of the attacks he inflicts: and, being either by cutting or by thrusting, we shall do the same offences and defences as if we had no cloak, except when we wish to parry, which we shall always do, not with the sword alone, but with the sword accompanied by the cloak, and in the second half we shall attack the right opposite sides.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/153|3|lbl=139.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If, then, we wish to wait for the enemy, we shall ascertain which foot he will use to move forward, and we shall try to do so with the other foot, different from the one used for the purpose. For if he moves forward with his right foot, we shall move forward with our left foot, and if he moves forward with his left foot, we shall do the same with our right foot.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/153|4|lbl=139.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>Acknowledging, that when the contrary is found with the right ahead, and that we with the left oppose it will then be with the intention of allowing all attacks to pass through; and to attack in the downward direction, with the accompaniment of the cloak.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/153|5|lbl=139.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/154|1|lbl=140.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>And if we stand with the left hand in front of us, and we stand with the right, then we will immediately parry with the hand, attacking the legs or the right arm or the ''punta riversa''.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/154|2|lbl=140.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>In this case we will be able to parry the cuts with our cloak alone, because we will parry the enemy’s rise [of his sword] with our own [parry] in the first third of the sword, before it is declines in strength.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/154|3|lbl=140.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>We must remedy the enemy’s attack with our sword, so that we can be sure of the attack outside of this tempo: and if we were to attack the enemy by chance at that time, it would be drawn in part, where the enemy’s cloak would entangle and impede our sword so that we would not recover it in time. Therefore, by securing ourselves against the enemy’s attack, we shall attack him secondarily in his right parts.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/154|4|lbl=140.4}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Ghisliero 25.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| + | | <p>In order to wait for the opposite, we shall place ourselves in this guard, which is shown below; that is to say, with the left foot forward in a half step, with the weight on the right leg, and with the sword across - then the point of is above our head with the fist at the level of the left shoulder and with the flat of the left hand wrapped in the cloak, and in the first strong point of the sword.</p> | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/154|5|lbl=140.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/155|1|lbl=141.1|p=1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p>In this posture, the enemy’s sword is always held inwards; and when he pulls, whatever he wishes, to make a strong attack (be it by a cut or a point), he is stronger with his left foot alone: and when he extends that line, he attacks himself, helping the sword with the strength of his left hand. As this figure demonstrates.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/155|2|lbl=141.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If, however, we allow the enemy to pass with a right hand, the respondent, taking advantage of this point of view will be able to make a mortal wound, leaving behind his cloak, which will close the way for the enemy’s sword.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/157|1|lbl=142.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If, while we are in this posture, the enemy does not resolve to attack us, but, putting himself on guard, waits until we are the first to attack; and if he stands with his foot straight forward, and with his sword in front of him, we with the ''stringeremo''<ref>''Stringeremo'' appears to mean the same as ''stringere'' or a drawing close posture. Most commonly used as ''stringere la spada'' where using the stronger part of the sword you engage with the weaker part of the opponent’s sword and take the line or advantage so the point of the opponent’s sword can no longer strike you.</ref> posture will hold him, wounding him with the same attack.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/157|2|lbl=142.2}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | <p>If, however, he should try with his left foot to strike our sword with his cloak, we shall return with our left foot to the centre, and go out to the first of the four guards we have proposed; and with that fist we shall attack with the point or the cut, or above, passing the point and entering the face.</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/157|3|lbl=142.3}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Temp == | ||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Chapter 20 - Treatise on the Buckler | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>Transcription<br/>by [[Nicola Boyd]]</p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 23:03, 23 March 2024

| Federico Ghisliero | |

|---|---|

| Died | 1619 Turin, Italy |

| Occupation |

|

| Citizenship | Bologna |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) | Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (1587) |

| Translations | Alternate English translation |

Federico Ghisliero was a Bolognese soldier and fencer. Little is know about his early life, but he came from a Bolognese family and studied fencing under the famous Silvio Piccolomini.[citation needed] He lead a long military career that included serving under the famous commander Alessandro, Duke of Parma, in Flanders in 1582. He was also a frind of Galileo Galilei and a prolific writer, though unfortunately most of his writings were destroyed in a fire at the University of Turin in 1904.[1]

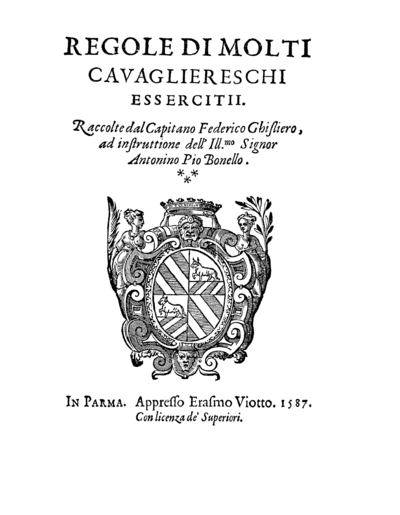

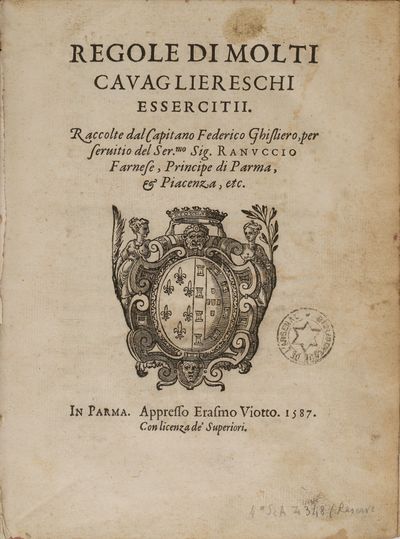

In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii ("Rules for Many Knightly Exercises"); two versions of the first edition exist, and it's unclear which was created first. One is dedicated to dedicated to Antonio Pio Bonello, a well-known soldier and distance relative, and the other to Ranuccio Farnese, who was 18 years old at the time and Alessandro's heir.[1]

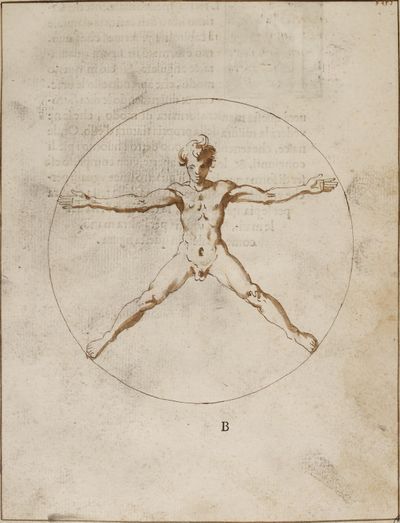

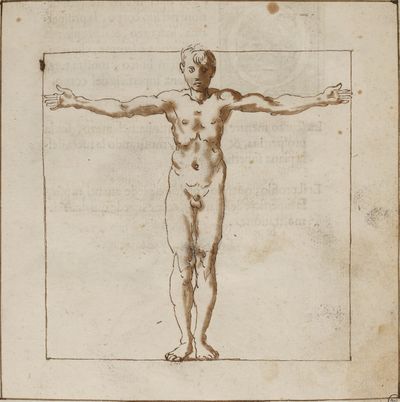

Ghisliero's treatise is notable for his use of geometry in relation to fencing, using concentric circles centered on where the fencer has placed most of their weight (often, but not always, the back foot), and sometimes including multiple versions of each figure in an illustration to show the progression of the movements he describes. He also seems to be the first author to include a Vitruvian Man in a fencing treatise.[2] However, his treatise is unique in that it was printed without any illustrations at all, and they had to be drawn in by hand. It's unclear whether this indicates that he intended to have printing plates made but was unable to do so, or that his plan from the start was to have the books vary based on how much art each buyer was willing to pay for.

Treatise

Temp

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Images | Bibliothèque nationale de France | ||

| Translation | Nicola Boyd | Rules of many knightly armies | |

| Transcription | Nicola Boyd | Index:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) |

Additional Resources

The following is a list of publications containing scans, transcriptions, and translations relevant to this article, as well as published peer-reviewed research.

- Anglo, Sydney (1994). "Sixteenth-century Italian drawings in Federico Ghisliero's Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii." Apollo 140(393): 29-36.

- Gotti, Roberto (2023). "The Dynamic Sphere: Thesis on the Third State of the Vitruvian Man." Martial Culture and Historical Martial Arts in Europe and Asia: 93-147. Ed. by Daniel Jaquet; Hing Chao and Loretta Kim. Springer.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Anglo 1996, p. 30.

- ↑ Gotti 2023, pp. 130-133.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cavagliereschi is Corsican for "chivalrous", while the Italian is "knightly".

- ↑ La gratia is Catalan for "grace".

- ↑ Ghisliero is telling his reader that he is a soldier not a civilian swordsman, so it will have a different perspective to others, hence his later comments on siege craft. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ This and the previous paragraph are commending the work to the patron, justifying the work’s existence and its purpose, common in treatises of the period. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ It was common to refer to “ancients” in the justification of the art of swordsmanship. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ When ‘this art’ or ‘the art’ is referenced it means the art of fencing. [More expansively the ars militari (military arts) or for the more classical, the Arts of Mars, of which swordsmanship falls within.] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Further justification by demonstration of the benefits to those who practice the art in question, also common, especially referring to defense of the person and the realm. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The version dedicated to Antonino instead reads "...for the instruction of the Most Illustrious Lord Antonio Pio Bonello".

- ↑ Cavalier – cavaliere – knights – so indicating the noble nature of the art which he is presenting. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The Humours.

- ↑ Means sad.

- ↑ Means calm.

- ↑ Means optimistic.

- ↑ Means bad-tempered.

- ↑ Hot-tempered.

- ↑ Moti has a number of meanings in modern Italian aside from "motion", including "motorcycle, bike, watercraft, riot, scooter".

- ↑ The use of square brackets [] shows the insertion of the translator to aid in clarity of meaning throughout the document.

- ↑ Contextually, transportar is in modern Italian trasporto and has been translated such.

- ↑ Where the word operante which means the operator or the person taking action or more simply the will is used elsewhere, I translate it to fencer as operator has the wrong connotations in English for what Ghisliaro appears to wish to convey.

- ↑ This is an application of Aristotle’s Causes, in some ways more easily explained due to the application of the sword (though this could be my fencer’s brain), especially as it develops. Ghisliero uses seven rather than four as Aristotle does, or at least using the same method of explanation. [Henry Fox]

- ↑ The spelling of secóda is seconda in modern Italian. This shortening of words through the removal of ‘n’ is common in documents of the period.

- ↑ Public roads means the location is a public road.

- ↑ Of Vitruvius’ Ten Books on Architecture. [This same book is referenced in Thibault] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Or capacity.

- ↑ Flavius Vegetius Renatus' On Roman Military Matters is likely the text to which he is referring. Which was a fourth century commentary on the training of Roman legions harking back to older methods. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Onde is Catalan. It is dove in Italian. Both mean ‘where’ in English.

- ↑ A second century book written by a Roman in the Attica region which encompasses the city of Athens.

- ↑ Dodrans is a Latin contraction of de-quadrans which means “a whole unit less a quarter” or three-quarters.

- ↑ Referencing the ‘ancients’ for authority was commonly used by authors of the time to demonstrate their comprehensive knowledge of the subject. It is intended to add gravitas to the treatise.

- ↑ All’hora is Catalan. Modern Italian is al tempo.

- ↑ The Elder.

- ↑ Scriue is Catalan. Modern Italian is lui scrive.

- ↑ Scurzo, does not translate appropriately from Italian. As with a number of words in Ghisliero’s treatise, it is likely a Catalase word or a unique spelling. Analysis of other treaties such as Jarod Kirby’s Italian Rapier Combat (Kirby, 2004) shows the following two definitions, on page 14 of the text, of a similar sound word that is contextually a more likely approximation of what scurzo means; “Scanso, A voidance, any evasive manoeuvre that moves the body of the direct line” and “Scanso del pie dritto, A voidance made by moving the right foot slightly off the direct line while turning the body.” So for the purposes of this translation, scurzo will mean in this text the middle stance as shown in Figure 3, i.e. a partial voiding stance halfway between perspective and profile.

- ↑ "Perspective" means front facing forward.

- ↑ Also could be interpreted as "figure".

- ↑ George Silver’s theory of the time for the hand and foot from his 1599 text Paradoxes of Defense mirrors this framework. [note from Henry Fox] (Silver, 1599)

- ↑ Et is Latin for ‘and’ in English and e in Italian.

- ↑ This is not an exact translation – it is the best approximation based on context.

- ↑ Balancia translates into ‘balance’.

- ↑ Membro translates to ‘member’, but in English a better word is limb.

- ↑ ò á mano manca la fontanella directly translates to something like ‘the hand missing the fontanelle’. This made no contextual sense, so it has been translated to ‘from the fountain of the body’ as fonta can mean ‘source’ in modern Italian. In the it states that “Fontánella, a little fountaine. Also a fontanell or cauterie [something to cauterise wounds], or rowling [turning round about, whirling or turning round], used also for the chiefe vein of a man’s body.” (Florio, 1611)

- ↑ ‘Perspective’ is forward facing as can be seen in Figure 3.

- ↑ No good translation found, contextually translating spatio to ‘space’.

- ↑ Polykleitos's Doryphoros is an early example of this position called contrapposto. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polykleitos for examples of sculptures with this stance. (Wikipeadia, 2021)

- ↑ Polykleitos wrote a lost treatise called ‘Artistic canons of body proportions’ in 5th Century Greece which provided a reference for standard body proportions. For more information https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artistic_canons_of_body_proportions (Wikipeadia, 2021)

- ↑ The act or process of passing across, over, or through.

- ↑ Aristotle’s fifth book of the Physica, which considers how motion occurs. “Book V classifies four species of movement, depending on where the opposites are located. Movement categories include quantity (e.g. a change in dimensions, from great to small), quality (as for colours: from pale to dark), place (local movements generally go from up downwards and vice versa), or, more controversially, substance. In fact, substances do not have opposites, so it is inappropriate to say that something properly becomes, from not-man, man: generation and corruption are not kinesis in the full sense.” (Aristotle, Physica (Book 5), (384–322 BC) 2007) “Generally things which come to be, come to be in different ways: (1) by change of shape, as a statue; (2) by addition, as things which grow; (3) by taking away, as the Hermes from the stone; (4) by putting together, as a house; (5) by alteration, as things which ‘turn’ in respect of their material substance.” Book 1, Physica, Aristotle (Aristotle, Physica (Book 1), (384-322 BC) 2007)

- ↑ Change of shape.

- ↑ By addition or by growing.

- ↑ Also taking away or removing.

- ↑ Putting things together or building.

- ↑ Change of material substance or alteration of its substance.

- ↑ “Three kinds of motion - qualitative, quantitative, and local” Book 5, Physica, Aristotle (Aristotle, Physica (Book 5), (384–322 BC) 2007)

- ↑ This same concept is present in Chapter 5 ‘Of tempo’ in Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli’s 1610 publication Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma and can be translated into the actions of the fencer undertaking the correct movements - from ward (stillness) to attack or defence (movement) to ward (stillness) again. It propounds that the fencer should always end an action in a ward. The same concept is raised in Angelo Viggiani dal Montone’s 1551 (published 1575) text Lo Schermo d'Angelo Viggiani (Montone, 1575) and Antonio Manciolino’s 1531 Opera Nova (Manciolino, 1531).

- ↑ "Violence" in this instance means outside force or against nature. The same concepts of natural and violent actions are used in Iberian swordsmanship, and they take higher guards to take advantage of this principle. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Springimento is likely Springáre means ‘yarke, kicke or winze’ (Florio, 1611). Which likely means in context a preparation or a marshalling of position prior to deployment.

- ↑ Fighting at the barriers was a form of tournament bout usually performed by armoured combatants in which: a fence, a barrier, was imposed between fencers, combatants fought over the fence, and blows below the waist did not count as tournament points. [note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ Bases mean "legs". I have used "legs" wherever relevant in the translation.

- ↑ “Lacertoi, the arme from the elbow to the pitch of the shoulder. Also the brawne of sinnewes or muskles of a mans armes or legges. Also a Lizard. Also a Muskle because it is like a Lizard. Also a certain disease in a harse amongs the muskles and sinnuewes. Also a fish that grunteth as a Hog. Some have taken it also for a makrell fish.” (Florio, 1611) Thus lacertoi will be translated as the arm from the elbow to the shoulder joint.

- ↑ Keeping the elbow near the body.

- ↑ “Rascetta, the wrist of one’s hand. Also a kind of fine silke-rash.” (Florio, 1611)

- ↑ Direct translation is ‘good blade’.

- ↑ Costa “the back of a knife or weapon.” (Florio, 1611) There isn’t a common English equivalent which is a single word.

- ↑ This is consistent with Giacomo di Grassi’s treatise Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l'Arme (Grassi, 1570) which states that there is more power existing at the circumference of a circle than there is closer to the centre. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Debole refers to the half of the blade from tip of the blade to one third down towards the hilt.

- ↑ Forte refers to the first third of the blade from the hilt to towards the tip.

- ↑ Placing the edge over the debole like this is the basis of the Italian gaining stringere of the sword, or the Spanish atajo. It's used to close and control the line to prevent the opponent from hitting us. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí]

- ↑ Here Ghisliero’s methods conforms to common Italian approaches of defence to: always counter an opponent’s attacks with consideration for returning the attack, always attack with concern for defence, and not attack unless secure against the opponent’s attack. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Justifications for use of the cut seem to be relatively rare in fencing treatise of the time. Ghisliero’s justifications may even be unique. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The same justification for the thrust is given for the thrust being used by the legionary with the gladius, remaining more covered and it being more deadly than the cut. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Fendente means vertical cut.

- ↑ Traversale – transversal or diagonal cut [sometimes squalembrato for downward or falso if rising] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Tondo – horizontal cut

- ↑ Dritti – straight/forward [forehand cut, or natural cut, sometimes called mandritta] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Roversi – reverse [backhand or cross-wise cut] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The division for the cuts on most diagrams usually go through the navel, or heart rather than the groin in most treatise of the period. [note from Henry Fox] Gérard Thibault d'Anvers’ 1630 treatise Academie de l'Espée ‘Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 2 – Comparing the ideal figure to a real Figure; Sword Scabbards’ shows the division at the naval (d'Anvers, Academie de l'Espée, 1630) – in the text it is found in the section that begins Pour venir à la Pratique de tout ce qui a efté discouru, or “To come to the Practice of all that has been discussed” (d'Anvers, Academie de l'Espée – Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 1 – Philosophical Discussion; Construction and Mathematics of the Circle; Concerning the Sword: Proper Length and Introduction explanation of the first plate., 1630). Salvator Fabris, in his 1606 text, Sienza e Pratica d’Arme also has an illustration in the section Discorso sopra laprima guardia formata nel cauare la spada del fodero or “Discourse in the first guard formed in pulling the sword from the scabbard” demonstrates the where cuts should be made and these also shows the division at the navel rather than the groin. (Fabris, 1606)

- ↑ Diritto ridoppiato literally means right redoubled or a falso traversale meaning a diagonal rising cut.

- ↑ Stramazzóne means a circular cut where the hand is the centre of rotation for the cut. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí] Florio describes it as ‘Stramazzóne, a downe-right blow. Also a rap, a cuffe or wherret on the cheeke.” (Florio, 1611)

- ↑ ‘Molinello, or Molinelli means a circular cut. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí] As an aside, the Molinello for flags described in Francesco Fernando Alfieri’s 1638 treatise La Bandiera “The molinello is delightful. To perform it comfortably, you should have the standard in your right hand. You complete a full turn above the head, then throw it up in the air, catching it around the middle of the standard as the figure shows. The molinello is then turned towards the rear foot. After several rotations, as the hand becomes fatigued, you should grip the butt of the flag with your other hand and repeat the same lesson, again throwing it in the air as described above.” (Alferi, 1638)