|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Federico Ghisliero"

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{infobox writer | {{infobox writer | ||

| name = [[name::Federico Ghisliero]] | | name = [[name::Federico Ghisliero]] | ||

| − | | image = | + | | image = File:Ghisliero portrait.jpg |

| − | | imagesize = | + | | imagesize = 300px |

| caption = | | caption = | ||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

| principal manuscript(s)= | | principal manuscript(s)= | ||

| first printed edition= | | first printed edition= | ||

| − | | wiktenauer compilation by= | + | | wiktenauer compilation by=[[Michael Chidester]] |

| signature = | | signature = | ||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

'''Federico Ghisliero''' (Ghislieri; d. 1619) was a Bolognese soldier and fencer. Little is know about his early life, but he came from a Bolognese family and studied fencing under [[Silvio Piccolomini]].<ref>Mentioned on [[Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/10|p. +ⅱ]] of his dedication to Ranuccio and again on [[Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/108|p. 94]].</ref> He lead a long military career that included serving under the famous commander Alessandro, Duke of Parma, in Flanders in 1582. He was also a friend of Galileo Galilei and a prolific writer, though unfortunately most of his writings were destroyed in a fire at the University of Turin in 1904.<ref name="Anglo 30">Anglo 1994, p. 30.</ref> | '''Federico Ghisliero''' (Ghislieri; d. 1619) was a Bolognese soldier and fencer. Little is know about his early life, but he came from a Bolognese family and studied fencing under [[Silvio Piccolomini]].<ref>Mentioned on [[Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/10|p. +ⅱ]] of his dedication to Ranuccio and again on [[Page:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) 1587.pdf/108|p. 94]].</ref> He lead a long military career that included serving under the famous commander Alessandro, Duke of Parma, in Flanders in 1582. He was also a friend of Galileo Galilei and a prolific writer, though unfortunately most of his writings were destroyed in a fire at the University of Turin in 1904.<ref name="Anglo 30">Anglo 1994, p. 30.</ref> | ||

| − | In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called ''[[Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero)|Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii]]'' ("Rules for Many Knightly Exercises"); two versions of the | + | In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called ''[[Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero)|Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii]]'' ("Rules for Many Knightly Exercises"); two versions of the book exist, and it's unclear which was created first. One is dedicated to Antonio Pio Bonello, a well-known soldier and distant relative of Ghisliero, and the other to Ranuccio Farnese, who was 18 years old at the time and Alessandro's heir.<ref name="Anglo 30"/> |

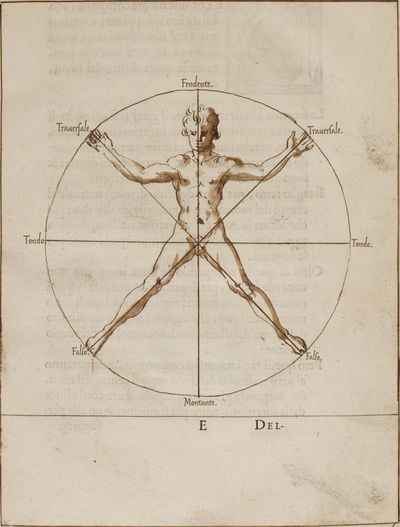

Ghisliero's treatise is notable for his use of geometry in relation to fencing, using concentric circles centered on where the fencer has placed most of their weight (often, but not always, the back foot), and sometimes including multiple versions of each figure in an illustration to show the progression of the movements he describes. He also seems to be the first author to reference the ''Vitruvian Man'' in a fencing treatise.<ref>See pp. 7-9. See also Gotti 2023, pp. 130-133.</ref> However, his treatise is unique in that it was printed without any illustrations at all, and they had to be drawn in by hand. It's unclear whether this indicates that he intended to have printing plates made but was unable to do so, or that his plan from the start was to have the books vary based on how much art each buyer was willing to pay for. | Ghisliero's treatise is notable for his use of geometry in relation to fencing, using concentric circles centered on where the fencer has placed most of their weight (often, but not always, the back foot), and sometimes including multiple versions of each figure in an illustration to show the progression of the movements he describes. He also seems to be the first author to reference the ''Vitruvian Man'' in a fencing treatise.<ref>See pp. 7-9. See also Gotti 2023, pp. 130-133.</ref> However, his treatise is unique in that it was printed without any illustrations at all, and they had to be drawn in by hand. It's unclear whether this indicates that he intended to have printing plates made but was unable to do so, or that his plan from the start was to have the books vary based on how much art each buyer was willing to pay for. | ||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

{{TOC limit|3}} | {{TOC limit|3}} | ||

== Treatise == | == Treatise == | ||

| + | |||

| + | The illustrations in this presentation are based on the copy in the [[Bibliothèque nationale de France]], but a few have been modified by [[Michael Chidester]] to include additional details present in the [[Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna]]'s copy in order to offer a single point of reference for the descriptions in the text. The unmodified illustrations can be viewed in the gallery on the [[Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero)|treatise page]]. | ||

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| Line 3,463: | Line 3,465: | ||

{{sourcebox | {{sourcebox | ||

| work = Translation | | work = Translation | ||

| − | | authors = [[Nicola Boyd]] | + | | authors = [[translator::Nicola Boyd]] |

| − | | source link = | + | | source link = https://wiktenauer.com/images/3/31/Rules_of_many_knightly_armies_%28Nicola_Boyd%29.pdf |

| − | | source title= '' | + | | source title= ''Rules of many knightly armies'' |

| license = noncommercial | | license = noncommercial | ||

}} | }} | ||

Latest revision as of 00:45, 29 March 2024

| Federico Ghisliero | |

|---|---|

| |

| Died | 1619 Turino |

| Occupation | Soldier |

| Citizenship | Bologna |

| Influences | |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) | Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (1587) |

| Manuscript(s) | M.A.M. Ghisliero MS (1585) |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | Alternate English translation |

Federico Ghisliero (Ghislieri; d. 1619) was a Bolognese soldier and fencer. Little is know about his early life, but he came from a Bolognese family and studied fencing under Silvio Piccolomini.[1] He lead a long military career that included serving under the famous commander Alessandro, Duke of Parma, in Flanders in 1582. He was also a friend of Galileo Galilei and a prolific writer, though unfortunately most of his writings were destroyed in a fire at the University of Turin in 1904.[2]

In 1587, he published a fencing treatise called Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii ("Rules for Many Knightly Exercises"); two versions of the book exist, and it's unclear which was created first. One is dedicated to Antonio Pio Bonello, a well-known soldier and distant relative of Ghisliero, and the other to Ranuccio Farnese, who was 18 years old at the time and Alessandro's heir.[2]

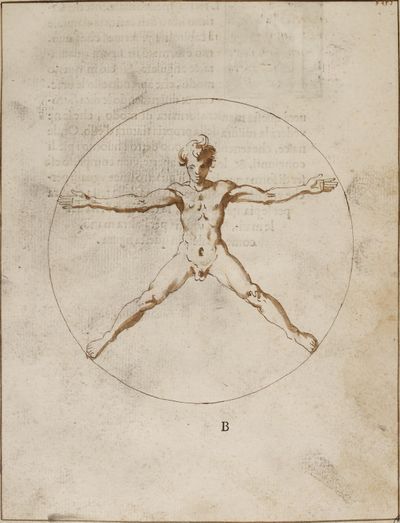

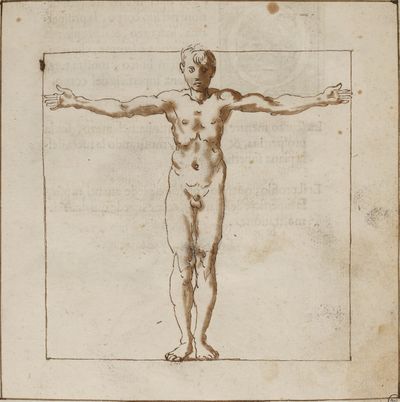

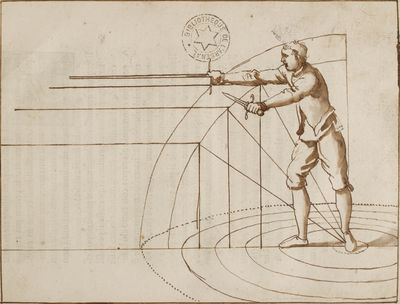

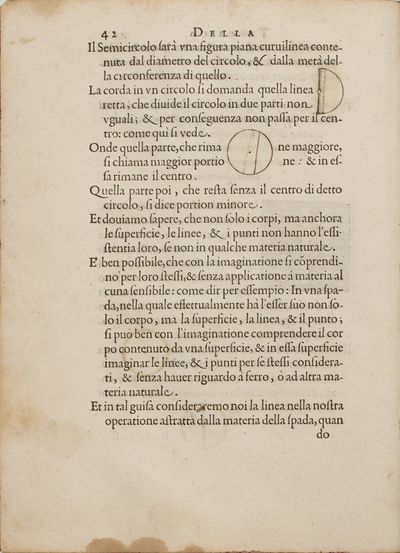

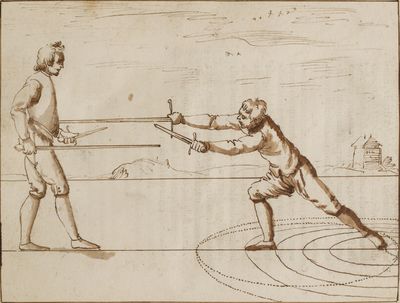

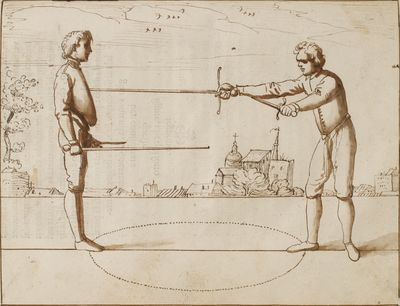

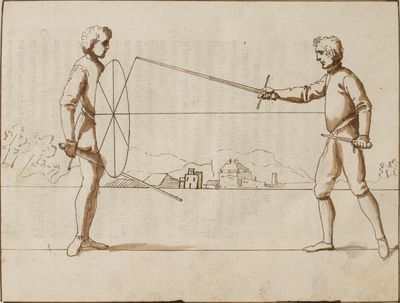

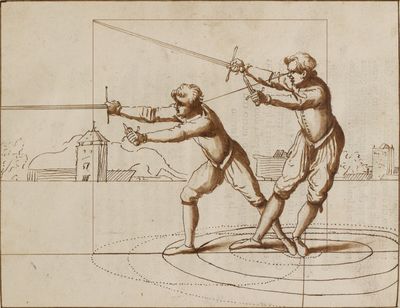

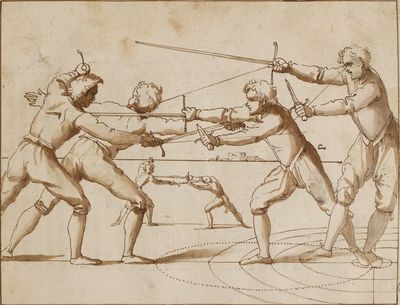

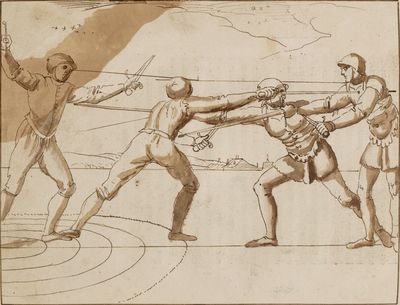

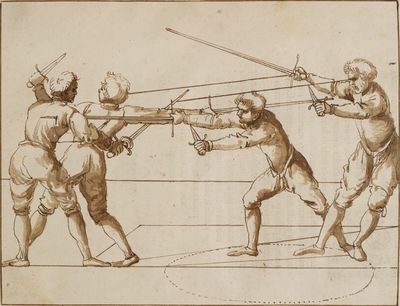

Ghisliero's treatise is notable for his use of geometry in relation to fencing, using concentric circles centered on where the fencer has placed most of their weight (often, but not always, the back foot), and sometimes including multiple versions of each figure in an illustration to show the progression of the movements he describes. He also seems to be the first author to reference the Vitruvian Man in a fencing treatise.[3] However, his treatise is unique in that it was printed without any illustrations at all, and they had to be drawn in by hand. It's unclear whether this indicates that he intended to have printing plates made but was unable to do so, or that his plan from the start was to have the books vary based on how much art each buyer was willing to pay for.

Ghisliero died in Turino in 1619.[2]

Contents

- 1 Treatise

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 Theory

- 1.3 Practice

- 1.4 Advertisements of the Sword and Dagger

- 1.5 Advertisements of the Single Sword

- 1.6 Treatise on the Sword and Cloak

- 1.7 Treatise on the Buckler

- 1.8 Treatise Against a Left-Handed Person

- 1.9 Combat at the Barriers

- 1.10 Treatise of a Fighter on Foot Against a Fighter on Horseback

- 1.11 Treatise of One on Horseback Against Another on Horseback

- 1.12 Copyright and License Summary

- 2 Additional Resources

- 3 References

Treatise

The illustrations in this presentation are based on the copy in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, but a few have been modified by Michael Chidester to include additional details present in the Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna's copy in order to offer a single point of reference for the descriptions in the text. The unmodified illustrations can be viewed in the gallery on the treatise page.

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Advertisements of the Sword and Dagger If we want to use our first guard, there are five ways in which we could go against this posture: but all will be in vain if we operate according to reason and the knowledge of the weapon. |

[133.1] AVERTIMENTI DI SPADA, ET PUGNALE. Volendo noi metterci nella nostra prima guardia, potrebbe il contrario in cinque modi operare contra la detta postura: ma tutto farà in vano, se noi operaremo secondo la ragione, et la scientia del givoco. | |

In the first way, he will try to approach from a distance, and with speed he will move his sword across, in order to attack with his dagger. But this is remedied by attacking the enemy in motion, before he reaches the distance. In addition, with every little movement we raise our sword, we will put it into the attack in a straight line. Moreover, we shall pass with our left foot and attack with our dagger. |

[133.2] NEl primo modo cercherà di accostarsi nella distantia; & con velocità s’aventerà alla apada cóla sua al traverso, per ferire col pugnale. Ma à questo si rimedia col ferire il nemico in moto, avanti che arrivi alla distantia. Oltra di questo con ogni poco moto alzando la nostra spada, la metteremo nella ferita in linea retta. Di più passaremo col manco piede, & feriremo col pugnale. | |

In the second way, he will study the opposite of going to the sword, in order to attack with the reversed blow: but this is remedied by centring with the right foot: because in this way he will not be allowed to approach: so that in those movements we will be able to attack him; and supposing that he were to dig out the reversed attack, we will drive our sword in a straight line, with the body in profile, thus cutting that line. |

[133.3] Nel secondo modo, studiarà il contrario d’andare alla spada, per ferire di ponta riversa: ma à questo si rimedia facendo centro col diritto piede: perche cosi non se li permetterà l’avicinarsi: avenga che in quei suoi moti lo potremo ferire; & presupposto, che egli cavasse la ferita riversa, noi cacciaremo la [134.1] nostra spada in linea retta, col corpo in profilo, che cosi segaremo quella linea. | |

In the third way, with the low sword tilting, the apposite will be done by the inquartata: and therefore we will move tilting above; and with the dagger we will hold back the sword so that it does not rise. |

[134.2] Nel terzo modo, con la spada bassa giostrando, il contrario farà l’inquartata: & perciò noi si moveremo giostrando per di sopra; & col pugnale riteneremo la spada che non monti. | |

In the fourth way, he will do the opposite, flowing up the sword by the middle, not to attack, but to drive out the punta riversa, which is remedied in the same way. |

[134.3] Nel quarto modo farà il contrario montare la spada per mezo, non per ferire: ma per cacciare la punta riversa, àche siu rimedia con l’istesso modo detto. | |

In the fifth way, he will put the point of the sword in his fist to prevent it from descending. We will not allow this if we are attacked immediately after the enemy’s sword reaches our body, but if we assume that the sword is already in our fist, we will make a little sign of retreat with the fist of the sword alone, because if he puts the sword back in that motion we will attack him. |

[134.4] Nel quinto modo, metterà il contrario la punta della spada nel pugno, per impedirla: accioche non descenda. A questo non consentiremo, se subio, che la spada nemica ci mostra il corpo, feriremo: ma presupposto, che già la spada sia messa nel nostro pugno, faremo un poco di segno di ritirata, solo col pugno della spada: perche s’egli rimetterà la spada in quel moto lo feriremo. | |

If, in presenting himself, a man is deceived or disconcerted, he must withdraw by drawing a circular slash which cleaves the ground: and then, having recognized himself, he must recover. |

[134.5] Se nell’appresentarsi l’huomo si fosse ingannato, ò si fosse sconcertato, deue ritirarsi tirando un riverso circolare, il quale fenda la terra: & poi riconosciutosi si debbe rimettere. | |

When the sword is impeded, one must yield to that force; and attack by that movement which the same force causes to be made, and this way of operating in arms is most perfect. |

[134.6] Quando si fente impedita la spada, si deue cedere à quella forza; & ferire di quel moto, che l’istessa forza fa fare, & questo modo di operare nell’ armi è perfettissimo. | |

If the enemy counterattacks, we must also counterattack, and hence the latter has the advantage. |

[134.7] Se il nemico contrapassa, bisogna che noi parimente contrapassiamo: & di quà il secódo hà avantaggio. | |

Since it is possible to attack with four fingers of the sword, we do not want or need to overdo it: because the first attack must be made while fleeing, especially when the enemy has a dagger. |

[135.1] Potendosi ferire con quattro dita di spada, non dbisogna voler soprafare: perche la prima ferita va fatta fuggendo, massime quando il nemico haurà il pugnale. | |

In all attacks, the length of the body should be taken first, and then the movement of the feet should be added; and care should be taken to ensure that the point is fast enough in reach to attack. |

[135.2] In tutte le ferite si farà prima la lunghezza del corpo; & poi si soggiungerà col moto de i piedi; & si procurerà, che il punto sia veloce per arrivarsi alla ferita. | |

Each time the dagger parries our attacks, we will repeat the blows, which will help us to strike the dagger; that is, we will not violate our arm from its natural position. |

[135.3] Ogni volta, che il pugnale pararà le nostre ferite, rifaremo le percosse; le quali ci aiuterà à fare la battuta del pugnale; cioè; noi non violentaremo il nostro braccio dal suo naturale. | |

Whenever we agree with our posture, if the enemy withdraws (which is mostly the case), we will lower our weapons and begin the fight again in the same way: and if we seem to be on our guard, we will reduce the enemy as much as we can, putting him in need. |

[135.4] Ogni volta, che accommetteremo con la nostra postura, se il nemico si ritirasse (ilche intraviene per lo più) noi abbassando l’armi di nuovo ricomminciaremo la zuffa col nostro medesimo modo: & se pure ci parerà di stare in guardia, anderemo restringendo il nemico, quanto più potremo, mettendolo in necessità. |

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Advertisements of the single sword Whenever the sword is engaged, it can be freed by withdrawing the left foot to the rear, and if the other side attacks it, it will be attacked at the same time. |

[136.1] AVERTIMENTI DI SPADA SOLA. OGni volta, che s’habbia la spada impegnata, ella potrà liberarsi ritirando il piede manco adietro: & se il contrario ferisse, in quel tempo medesimo si ferirà. | |

If, by pulling on an attack, we come to half a sword, we will free ours; if we hold it inward, we will pull it upward, piercing the attack: and with our left hand we will catch the opposite sword in its hilt. But if we have it on the other side, we will take it out from underneath, drawing it into the angle formed by the two swords with our left arm crossed in defense; and we will attack with the point of the sword’s fist[146] upwards. |

[136.2] Se tirandosi qualche ferita, si venisse à meza spada, liberaremo la nostra; se la teniremo di dentro, col tirarla per di sopra, piantando la ferita: & con la mano manca prenderemo la spada contraria nelli suoi fornimenti. Ma se l’hauremo per di duori, la caveremo per di sotto, cacciandosi dentro nell’angolo constituito dalle due spade col nostro braccio manco traversato alla difesa; & feriremo di punta col pugno della spada all’in su. |

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Treatise on the sword and cloak[147] When we use the cloak for defense, we must always remember that it differs from the dagger in that it can be cut and pierced, which is not the case with the dagger, and therefore we will never parry with the cloak in the same way as with the dagger. And just as the dagger cannot be used to parry stabbings, so the cloak cannot be used to parry them. And since we try to keep the dagger free from injury, the cloak cannot be kept in the hands of the enemy. |

[137.1] TRATTATO DI SPADA, ET CAPPA SEmpre, che si seruiremo della cappa per difesa, consideraremo che quella hà differenza dal pugnale: perche l’istessa può eser tagliata, & forata; ilche non aviene al pugnale: & perciò non pararemo mai con la cappa, nel modo istesso, come si faria col pugnale: & si come le coltellate col pugnale non si parano, cosi con la cappa non ei potra risistere à quelli: & poiche si cerca di tenere il pugnale libero dall’offese; consi la cappa nó si doura tener sottoposta al nemico. | |

All the same reasons, and all the ways, which we have said above of the single sword, and of the sword accompanied by the dagger, serve us with the sword and cloak: and of this there is no other use, than to impede the enemy; so that he may not have so easy an attack; and to cover the parts below. |

[137.2] Tutte le medesime ragioni, & tutti I modi, c’habbiamo detto di sopra di spada sola; & di spada accompagnata dal pugnale, ci seruono con la spada, & cappa: & di questo non si cava altr’utile, che d’impedire il nemico; affine, che’egli non hab- [138.1] bia cosi facile la ferita; & di coprire le parti da basso. | |

And yes, as we close the return of the enemy sword with the hand at this time when we are attacked by the points, so with the cloak we can better achieve our goal. |

[138.2] Et si come con la mano chiudiamo all’hora il ritorno alla spada nemica, quando uscendo coi punti feriamo; cosi con la cappa operando meglio otteniamo il nostro fine. | |

And because when the man is without a cloak he can be harmed and defended against in two ways: one is to throw it [the cloak] into his face and the other is to throw it over his sword at its debole; this [latter] is an easier way than the first. Therefore it [the cloak] will be taken with the flat hand and with the thumb only; and with a semicircular outward movement it will be collected in the fist, and united a man can take advantage of it at his pleasure and also deprive himself of it in order to come to grips with it. |

[138.3] Et perche con la cappa privandosi di questa l’huomo, in due modi si puo al contrario nuocere, & impedirlo: l’uno è il getarfliela nel viso: l’altro il buttar gliela sopra la spada nel suo più debole terzo; modo più facile del primp; perciò essa si piglierà con la mano piana, & col dito pollice solo; & tutta con un semicircolo per di fuori si raccoglierà nel pugno: accioche unita possa l’huomo à suo piacere, & seruirsene; & anchora privarsene per venire alle prese. | |

Hence it may be understood that the same order must be followed in drawing the sword, and in turning the cloak into the fist, as is done with the sword and dagger, and that this must be done without giving the enemy any idea of his [the man’s] own will. This is to be done by proceeding with the sword down and the cloak out from the body, with caution, and distinguishing what the enemy will do, who, either stationary or in motion, will have to take advantage of it. |

[138.4] Di quì può comprendersi, che s’haurà da tenere il me disimo ordine in cacciar mano alla spada, & in volgersi Ia cappa al pugno: come si fà nel modo di spada, & pugnale: & questo s’haurà da fare senza dar intentione al nemico dela sua volontà: ilche sarà col procedere con la spada bassa, & con la cappa fuori del corpo, accommettendo con cautela; & distinguendo quello, che farà il nemico, ilquale, ò in stato, ò in moto si dourà truovare. | |

If the contrary is found to be the case, it will necessarily be in one of the acts, which we have already mentioned, but against those we will use one of those offenses, which we have declared above. |

[138.5] Se si truoverà in stato il contrario, forzosamente sarà in uno de gl’atti, c’habbiamo già detto, però con- [139.1] tra quelli useremo una di quelle offese, che di sopra habbiamo dichiarato. | |

And if the same opponent holds his sword in front of him, we shall fight against him in the manner already indicated, but holding his cloak in front of him, we shall always use our natural motion with our straight hand; with cuts and points we shall nevertheless attack that fist facing away from the cloak and away from the enemy’s sword. |

[139.2] Etr se il medesimo contrario terrà la spada avanti, contra essa combatteremo co’modi già detti: ma egli tenendo la cappa avanti, sempre di moto nostro naturale à man diritta; con tagli & punte feriremo tuttavia quwl pugno volto dalla cappa, discostandosi dalla spada del nemico. | |

If, however, we find our opponent in motion, we shall act against him in accordance with the proportions of the attacks he inflicts: and, being either by cutting or by thrusting, we shall do the same offences and defences as if we had no cloak, except when we wish to parry, which we shall always do, not with the sword alone, but with the sword accompanied by the cloak, and in the second half we shall attack the right opposite sides. |

[139.3] Se poi peraventura noi truovassimo il nostro contrario in moto, noi operaremo contra lui, conforme alla proportione della ferita, che egli operasse: & essendo ò di taglio, ò di punta, l’istesse offese, & le difese, faremo, come se non havessimo la cappa: eccetto quando vorremo parare: che questo sempre non con la spada sola; ma con la spada accompagnata dalla cappa faremo, & di secondo tempo feriremo alle parti contrarie diritte. | |

If, then, we wish to wait for the enemy, we shall ascertain which foot he will use to move forward, and we shall try to do so with the other foot, different from the one used for the purpose. For if he moves forward with his right foot, we shall move forward with our left foot, and if he moves forward with his left foot, we shall do the same with our right foot. |

[139.4] Caso poi, che noi volessimo aspettare il nemico, avertiremo con qual piede egli si truoverà avanti: & noi si prefentaremo, con l’altro differente all’apposito: come, s’egli si truoverà col diritto avanti, noi col manco si metteremo all’incontro, s’egli col manco, & noi col diritto il simil faremo. | |

Acknowledging, that when the contrary is found with the right ahead, and that we with the left oppose it will then be with the intention of allowing all attacks to pass through; and to attack in the downward direction, with the accompaniment of the cloak. |

[139.5] Avertendo, che quando il contrario si truoverà col diritto avanti, & che noi col manco si opporremo sarà all’hora con intentione di lasciar passare [140.1] tutte le ferite; & di ferire nella declinatione, con l’accompagnamento di cappa. | |

And if we stand with the left hand in front of us, and we stand with the right, then we will immediately parry with the hand, attacking the legs or the right arm or the punta riversa. |

[140.2] Et stando il contrario col manco avanti; & noi col diritto, subito opponendoci col manco poi pararemo, ferendo alle gambe overo al braccio diritto, overo di punta riversa. | |

In this case we will be able to parry the cuts with our cloak alone, because we will parry the enemy’s rise [of his sword] with our own [parry] in the first third of the sword, before it is declines in strength. |

[140.3] In questo caso potremo parare i tagli con la cappa sola: perche con la cresciuta del nemico, & con la nostra pararemo nel primo terzo della spada, avanti che sia in declinatione in forza. | |

We must remedy the enemy’s attack with our sword, so that we can be sure of the attack outside of this tempo: and if we were to attack the enemy by chance at that time, it would be drawn in part, where the enemy’s cloak would entangle and impede our sword so that we would not recover it in time. Therefore, by securing ourselves against the enemy’s attack, we shall attack him secondarily in his right parts. |

[140.4] Si deue rimediare alla percossa nemica, con la nostra spada: accioche fuori di questa occasione si potiamo assicurare di tal ferita: & se ferissimo per ventura in quel tempo, per lo più si tirarebbe in parte, dove la cappa del nemico intricarebbe, & impedirebbe la nostra spada in modo, che non la riscoteressimo in tempo. Assicurando dunque noi stessi dalla ferita del nemico, lo feriremo di secondo tempo nelle sue parti diritte. | |

In order to wait for the opposite, we shall place ourselves in this guard, which is shown below; that is to say, with the left foot forward in a half step, with the weight on the right leg, and with the sword across - then the point of is above our head with the fist at the level of the left shoulder and with the flat of the left hand wrapped in the cloak, and in the first strong point of the sword. |

[140.5] Per aspettare poi il contrario, si metteremo in questa guardia, che quì di sotto si vede; cioè; col piede manco avanti in mezo passo, col peso sopra la base diritta, & con la spada traversale; la punta della quale superi il nostro capo; col pugno à livello della spalla manca, & con la mano [141.1] manca piana, involta nella cappa, & nel forte primo della spada messa. | |

In this posture, the enemy’s sword is always held inwards; and when he pulls, whatever he wishes, to make a strong attack (be it by a cut or a point), he is stronger with his left foot alone: and when he extends that line, he attacks himself, helping the sword with the strength of his left hand. As this figure demonstrates. |

[141.2] In questa postura si terrà sempre la spada nemica dominata in dentro; & tirando egli qual si voglia forte di ferita (sia ò di taglio, ò di punta) solo col manco piede si crescerà in passo sforzato: & distendendo quella linea si ferirà, con l’aiutar la spada con la forza della mano manca. Come dimostra questa figura. | |

If, however, we allow the enemy to pass with a right hand, the respondent, taking advantage of this point of view will be able to make a mortal wound, leaving behind his cloak, which will close the way for the enemy’s sword. |

[142.1] CAso poi che si concedesse, che il contrario passasse à mno diritta, il rispondente seruendosi del punto della prospettiua haurà da ferire d’imbroccatta, lasciando la cappa; la qual chiuda il ritorno alla spada del nemico. | |

If, while we are in this posture, the enemy does not resolve to attack us, but, putting himself on guard, waits until we are the first to attack; and if he stands with his foot straight forward, and with his sword in front of him, we with the stringeremo[148] posture will hold him, wounding him with the same attack. |

[142.2] Se mentre, che noi si truoveremo in detta postura, il nemica non si risoluerà à ferircil; ma mettendosi an ch’egli in guardia aspettarà, che noi siamo I primi à ferire; & esso si truoverà col pie diritto avanti; & con la spada in presentia, noi con la medesima postura lo stringeremo, ferendolo sempre con l’istessa ferita. | |

If, however, he should try with his left foot to strike our sword with his cloak, we shall return with our left foot to the centre, and go out to the first of the four guards we have proposed; and with that fist we shall attack with the point or the cut, or above, passing the point and entering the face. |

[142.3] Ma se col manco piede posto avanti cercasse il contrario d’adombrarci la nostra spada con la sua cappa, noi all’hora ritornado col manco piede nel centro, usciremo nella prima nostra guardia, tra le quattro c’habbiamo proposte; & à quel pugno di punta, overo di taglio feriremo: ò per di sopra, passando con la punta entreremo nel viso. |

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Treatise on the Buckler Many people have used the buckler in the same way as a dagger, and they have used it as a parry, accompanying it with the sword. However, since it is difficult for a man to show what he is capable of by means of some instrument, if he does not first make known what it belongs to, it is necessary, in order not to be mistaken, for them to know the quality and properties of the very instrument with which he intends to represent that essence. Since, therefore, we have to deal with the defensive instrument (as I said), we will begin by discussing it in this way. |

[144.1] TRATTATO DEL BROCCHIERO. EStato da molti adoperato il brocchiero nella guisa, che si farebbe un pugnale; é con esso háno parato, accompagnandolo con la spada; ma perche difficilméte può l’huomo mostrar qual che facultà col mezo di qualche instrumento, se prima non si fà conoscere ciò appartenente, bosogna per ogni via, affine di non incorrere in errore, che essi conoschino la qualità, & pro prietà del medesimo instrumento, col quale s’intende di rappresentare quell’essetto. Havendosi dunque da trattare del brocchiero instrumento (come dissi) difensivo, cosi prenderemo il principio di trattarne. | |

The buckler is a spherical, dense and opaque body, and in order for it to do its work properly, its surface must be less than a foot in diameter, since most men are a foot and a half wide: And because the effect of the buckler is to resist the sword, so that it cannot injure our body; since with this sword man can form different and infinite lines, which by similarity we can resemble the rays of the sun (a spherical and luminous body). Therefore we must know that there are two opaque bodies, that is to say, transparent: as are air, water and fire. |

[144.2] Il brocchiero è corpo sferico, denso, & opaco: & affine ch’egli faccia bene l’offitio suo, sarà nella curua superficie difuori di diametro d’un piede: atteso che per il piú gli huomini sono larghi un piede, & mezo: & perche l’effetto del brocchiero è di risi- [145.1] stere alla spada, accioche non possa ferire il nostro corpo; poiche con essa spada l’huomo può formare diverse, & infinite linee: le quali per similitudine potiamo assomigliare à i raggi del Sole, corpo sferi co, & luminoso: perciò debbiamo sapere, che due sono i corpi opaco; cioè, trasparente: come sono l’aere, l’acqua, & il fuoco. | |

Therefore perspective, as we read in the fourth proposition of the first part of the common perspective, wants a spherical, dense, opaque and consequently shadowy body to be considered in three ways with respect to another spherical, luminous and resplendent body. |

[145.2] Onde i prospettivi, si come si legge nella vigefima quarta propositione della prima parte della prospettiva commune, vogliono, ch’un corpo sferico, denso, & opaco, & conseguentemente ombroso, in tre modi possa esser considerato, rispetto ad un’altro corpo sferico, luminoso, & risplendente. | |

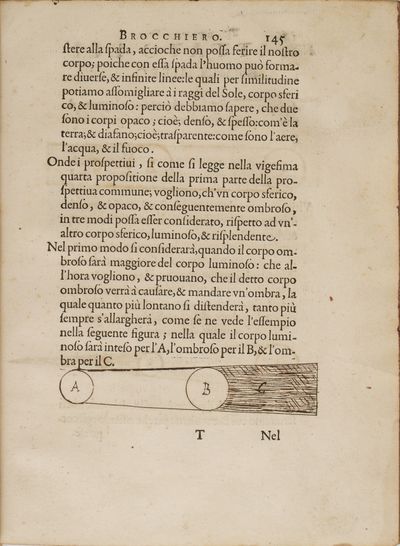

In the first way it will be considered, when the shadowy body is greater than the luminous body,; for then they will desire and demand that the said shadowy body will cause and cast a shadow, which, the farther it extends, the more it will grow larger and larger, as is shown in the following figure, in which the luminous body is understood as A, the shadowy as B, and the shadowed as C. |

[145.3] Nel primo modo si considerarà, quando il corpo ombroso sarà maggiore del corpo luminoso: che all’hora vogliono, & pruovano, che il detto corpo ombroso verrà à causare, & mandare un’ombra, la quale quanto più lontano si distenderà, tanto più sempre s’allargherà, come se ne vede l’essempio nella seguente figura; nella quale il corpo luminoso sarà inteso per l’A, l’ombroso per il B, & l’ombra per il C. | |

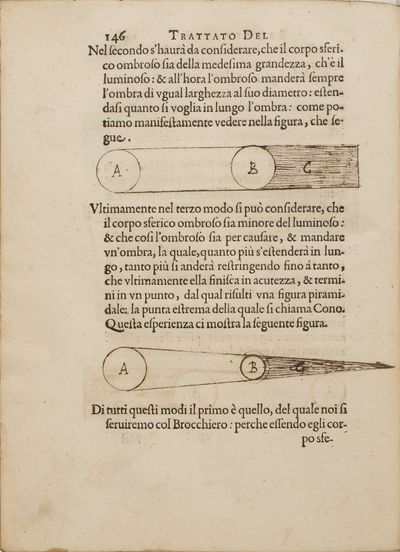

In the second, it must be considered that the spherical shadowed body is of the same size as the luminous one, and that the shadowed body will always send out a shadow of equal width to its diameter, and that the shadow may extend as far as one wishes, as we can clearly see in the following figure. |

[146.1] Nel secondo s’haurà da considerare, che il corpo sferico ombroso sia della medesima grandezza, ch’è il luminoso: & all’hora ombroso manderà sempre l’ombra di ugual larghezza al suo diamentro: estendasi quanto si voglia in lungo l’ombra: come potiamo manifestamente vedere nella figura, che segue. | |

Lastly, in the third way, we may consider that the spherical shadowy body is smaller than the luminous one, and that the shadowy one is thus to cause and send a shadow, which, the longer it extends, the more it shrinks until it finally ends in sharpness and ends in a point from which a pyramidal figure emerges, the extreme point of which is called the Cone. This experience shows us the following figure. |

[146.2] Ultimamente nel terzo modo si può considerare, che il corpo sferico ombroso sia minore del luminoso: & che cosi l’ombroso sia per causare, & mandare un’ombra, la quale, quanto più s’estenderà in lungo, tanto più si anderà restringendo fino à tanto, che ultimamente ella finisca in acutezza, & termini in un punto, dal qual risulti una figura piramidale: la punta estrema della quale si chiama Cono. Questa esperienza ci mostra la seguente figura. | |

Of all these ways, the first is the one which we will use with the buckler: because it is a spherical, opaque body, greater than the spherical, luminous body, or greater than the fist of the hand; from which, like the rays of the sun, arise the proportions of the lines which man forms with the sword, we will oppose it in such a way that it will cast a shadow, by which we will be covered and defended. |

[146.3] Di tutti questi modi il primo è quello, del quale noi si seruiremo col Brocchiero: perche essendo egli cor- [147.1] po sferico, opaco, maggiore del corpo sferico luminoso, ò maggiore del pugno della mano; dal quale, à guisa de raggi del Sole, sorgono le proportioni delle linee, le quali forma l’huomo con la spada, opporremo quello in modo, che manderà un’ombra, dalla quale noi saremo coperti, & difesi. | |

However, we shall note that on this occasion the sword will have the opposite effect, specifically in a straight line or in power; i.e. in an oblique line. When it is in a straight line, we shall regard it as a single ray of the Sun, and we shall oppose it with the at the same point; but when it is oblique to our body, we shall oppose it using the buckler at the body of the fist at the origin of the ray, or of the line, so that we will be covered by the shadow of the opaque body of the buckler. |

[147.2] DIstingveremo nondimeno in questa occasione, che il contrario overò haurà la spada in atto nella linea retta; overo in potenza cioè; in linea obliqua: quádo l’haurà in linea retta, questa consideraremo, come un raggio solo del Sole: & à quello nel punto istesso opporremo il Brocchiero: ma quando l’haurà obliqua al nostro corpo, opporremo il Brocchiero al corpo del pugno, come ad origine del raggio. Overo della linea: che cosi saremo coperti dall’ombra del corpo opaco del Brocchiero. | |

And just as many straight lines, which come from a centre, the further they move away from that centre, the more they dilate among themselves: so, that if we use the buckler to oppose the sword, either the sword will get stuck in it, or it will cut it, so that it will move further away from its centre and from our body. |

[147.3] Et si come molte linee rette, le quali vengono tutte da un centro, quanto più si allontanano da esso cétro, tanto più dilatano fra se medesime: cosi opponendo noi il Brocchiero alla spada, ò quella in esso s’intopperà, ò quello segarà: ond’ella più si allontanarà dal suo centro, & dal nostro corpo. | |

It will therefore be held in the hand with the thumb resting on it: so that this part does not fall inwards: otherwise our body would be exposed and offended: and so that it will always operate as a blurred body, we will hold it with the arm outstretched: so that the greater shadow will be caused by its distance from our body. |

[147.4] Si terrà dunque in mano col deto pollice messo per [148.1] appoggio: accioche quella parte non ceda in dentro: ch’altramente facendosi il nostro corpo verrebbe discoperto, & offeso: & accioche sempre operi, come corpo sfecrio, lo terremo col braccio disteso: onde venga causata per l’allontananza d’esso dal nostro corpo l’ombra maggiore. | |

So that with this, as with all other kinds of defensive weapons, we shall operate by committing ourselves, without giving the enemy any intention of our will: distinguishing that the enemy will either be in motion or in a stationary state of mind. |

[148.2] Di modo, che con questo si come con tutte l’altre sorti d’arme difensive, operaremo accommettendo, senza date intentione al nemico della nostra volontà: distinguendo, che il nemico, overo sarà in moto, overo sarà in stato. | |

If the enemy is in motion, he will either use a slash or a thrust: we shall make the same parries and attacks to these slashes as we have said; but when we parry them with the buckler, we shall proceed with the accompanied arms; and we shall follow the centre of the fist and counterattack with the left foot. |

[148.3] Se sarà in moto, ò tirerà di taglio, ò di punta: alle quali percosse di taglio, faremo l’istesse parate, & ferite; come habbiamo detto; ma parandole col Brocchiero, procederemo con l’arme accompagnate; & seguitaremo il centro del pugno, & col manco piede contrapasseremo. | |

I leave it to say that we may injure before, during and after tempo in the same manner as we have said in the treatise on the sword and dagger, but we must always put the buckler behind the fist of our sword, stretching out the arm and body, and covering ourselves with it. |

[148.4] Lascio di dire, che potremo ferire avanti tempo, & nel tempo, & dopò il tempo, con gl’istessi modi: come habbiamo detto nel trattato di spada, & pugnale: ma avertiremo di mettere sempre il Brocchiero appresso il pugno nostro della spada, distendendo bene il braccio, & il corpo; & coprendoci sotto à questo medesimo. | |

If the opponent thrusts with the point, he can make the same attacks and parries that have already been said; but since things can easily be moved while they are in motion, the same defence can be made with the buckler as if it were a dagger. |

[148.5] Se il contrario tirasse di punta, potrassi fare l’istesse ferite, & parate, che già si sono dette: ma perche alle cose, mentre che sono in moto, facilmente s’ag- [149.1] giunge nuovo moto, però si potrà far col Brocchiero l’istessa difesa, come se fosse un pugnale. | |

When the enemy is stationary, he may have his sword in front of him or behind him; if he has it in front of him or parallel with the ground in a straight line or at an angle. |

[149.2] Quando poi il nemico si tuova in stato, ò haurà la spada avanti in presentia, ò adietro: se l’hautà avanti in presentia, ò la terra in linea retta, ò in obliqua. | |

We shall oppose the buckler at the extreme point of each line, which will be high, and we shall pierce it underneath with our greatest length and in the same stroke. |

[149.3] A tutte le proportioni di linee, che saranno alte, noi gli opporremo nel punto suo estremo il Brocchiero; & feriremo per di sotto, con la nostra maggior lunghezza, & in una istessa battuta. | |

We shall oppose all straight lines which are at the right of the centre of our body (as in the case of the third and fourth guards) with the buckler at the extremity of the line; and above we shall put our sword to attack in a straight line. |

[149.4] A tutte le linee rette in presentia, le quali si truovano al diritto del centro del nostro corpo (come quando sono in guardia terza, & quarta) si opporrà il Brocchiero nel suo estremo; & per di sopra metterassi la nostra spada nella ferita in linea retta. | |

If, on the other hand, he holds his sword at an angle to our body, he will place the scabbard against his fist; and with the same stroke he will attack the nearest place above.

|

[149.5] Se il contrario terrà la spada in presentia obliqua al nostro corpo, si metterà il Brocchiero opposto al pugno; & con la medesima battuta si ferirà per di sopra al luoco più vicino. | |

If the opposite party holds the sword at an angle, the same offence will be carried out as if we had the dagger, helping the enemy’s sword to its inclination. |

[149.6] Caso, che il contrario tenesse la spada angolare, si farà l’istessa offesa, come se noi havessimo il pugnale, aiutando la spada del nemico alla sua inclinatione. | |

If we make the opposite move with the sword to the rear, we will seek out the enemy’s body in the aforesaid manner, and we will hold the buckler above our body in order to strike it, as if it were a dagger, thus necessitating the opposite sword to pass through it. |

[149.7] Mentre poiche truovaremo il contrario con la spada adietro, cercaremo il corpo nemico nel modo detto; & terremo il Brocchiero suori del nostro corpo per battere, come se fosse un pugnale, necessitando la spada contraria à passar per quello. | |

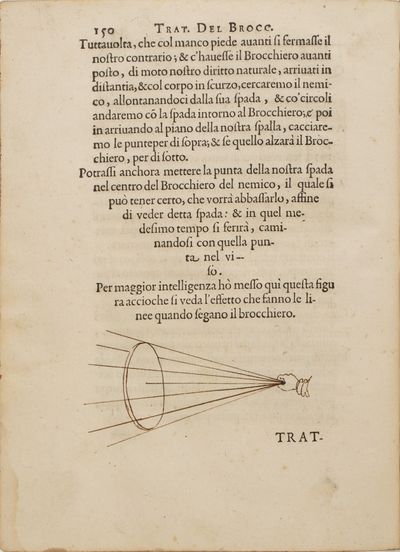

When we have stopped our opponent with our left foot in front and the buckler has been placed in front of us, we will, in our natural right hand, once we have arrived at a distance, and with our body in a dark position, seek out the enemy, moving away from his sword, and with our circles we will move the sword around the buckler, and then, arriving at the plane of our shoulder, we will throw our points upwards; and if he raises his buckler, we will do so below. |

[150.1] Tuttavolta, che col manco piede avanti si fermasse il nostro contrario; & c’havesse il Brocchiero avanti posto, di moto nostro diritto naturale, arrivati in distantia, & col corpo in scurzo, cercaremo il nemico, allontanandoci dalla sua spada, & co’circoli andaremo có la spada intorno al Brocchiero, é poi in arrivando al piano della nostra spalla, cacciaremo le punteper di sopra; & se quello alzarà il Brocchiero, per si sotto. | |

We may also place the point of our sword in the centre of the enemy’s scabbard, who may be certain to lower it in order to see the sword, and at the same time to wound himself by walking with the point in his face. |

[150.2] Potrassi anchora mettere la punta della nostra spada nel centro del Brocchiero del nemico, il quale si può tener certo, che vorrà abbassarlo, affine di veder detta spada: & in quel medesimo tempo si ferirà, caminandosi con quella punta nel viso. | |

For the sake of greater intelligence I have placed this figure here so that one may see the effect of the lines when they cut into the buckler. |

[150.3] Per maggior intelligenza hò messo quì questa figura accioche si vega l’essetto che fanno le linee quando segano il brocchiero. | |

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Treatise Against a Left-Handed Person[149] All the arguments of the single sword; of the sword and dagger; of the cloak; and of the buckler, serve the left-handed against the right-handed; as well as the right-handed against the left-handed. And the weapon of defence can serve no other purpose than to parry the blows, which are thrown from afar; & to close the line: because, when the right-handed man is fighting the left-handed man, both have their swords on one side and their bodies placed in such a way that all the points of their swords strike at an angle, so that they cannot be parried with a defensive weapon, and therefore they must be parried with the sword, since the weakness of the left-handed man’s sword will pass through the strength of the right-handed man’s sword. |

[151.1] TRATTATO CONTRA UN MANCINO. TUTTE le ragioni dette di spada sola; di spada é pugnale; di cappa; & di Brocchiero, seruono cosi al Mancino contra al diritto; come al diritto contra al Mancino: & dell’arme da difesa non potia mo seruirsi in altro, che in parare le botte, che di lontano sono tirate; & per chiudere il camino: perche venendo alla pugna il diritto contra al mancino tutti due hanno la spada da una parte, & il dcorpo posto in modo, che tutte le punte feriscono angolarmente: & perciò con l’arme difensiue non si possono parare, onde conuerrà, che con la spada si parino: atteso che il debole della spada del mancino passarà per il forte della spada del diritto. | |

Therefore, the right-handed sword should be held in such a way that it dominates the left-handed sword inwards; and with the body in profile and the good edge, it should drive the points to the nearest place to be attacked. |

[151.2] Terrà dunque la spada il diritto in stato, che domini la spada del mancino in dentro; & col corpo in profilo, & col filo buono si caccierà le punte al più prossimo luoco da ferire. | |

The right hand will never injure the left-hander from the inside; but if he is not in motion, he can be injured at that time. |

[152.3] Il diritto mai non ferirà per di dentro al mancino; saluo se egli non fosse in moto, che in tal tempo si potrà ferire. | |

The right-handed [person] must distinguish whether the left-handed person will hold his sword forward or backward; and will act against the left-handed person in the aforesaid manner; that is to say, dominating the sword when it moves forward, giving the left-handed person the power to attack in tempo; and when it moves backward, he will fight with his body ready to make the same attack, closing the way to the enemy’s sword with his defensive weapons. |

[152.1] Haurà da distinguere il diritto, se il mancino terrà la spada avanti, ò adietro; & operarà contra à quella col modo detto; cioè; dominando la spada, quando ella si truoverà avanti, dando il moto al mancino per ferire nel tempo; & quando si truoverà adietro, combatterà col corpo pronto à far l’istessa ferita, chiudendo il camino alla spada del nemico con l’arme difensive. | |

The right hand will allow all cuts to pass through, and will wound after the time of the slash; or it will help him to decline, and will attack backwards: it will also be able to parry covered, and will make all the same attacks, that we have said, that are made before the tempo. |

[152.2] A tutti i tagli il diritto lascierà passarli; & ferirà doppo il tempo di fendente; overo gli aiuterà alla declinatione, & ferirà di riverso: si potrà anchora parare coperto, & farà tutte l’istesse firite, che noi habbiamo detto, che si fanno avanti il tempo. |

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Treatise of a Fighter on Foot Against a Fighter on Horseback If a man on foot wishes to fight against a man fighting on horseback, he must act in accordance with the nature of the horse, which, being formed of a single body on four legs, has the natural movement of walking along the right side, and walking with any other kind of movement, that movement will be the centre of the legs in front of it. |

[172.2] TRATTATO D’UN COMBATTENTE A PIEDI CONTRA UNO A CAVALLO VOlendo l’huomo à piedi contrastare contro uno, che combatta á cavallo, conviene, ch’egli operi conforme alla natura del cavallo, il quale essendo formato di corpo lúgo sopra quattro basi, hà per moto naturale il caminare per il diritto: & caminando con ogn’altra sorte di moto, quel moto li sarà centro delle basi davanti. | |

It is therefore natural for all animals to flee from things which are harmful to their good being (since they are moved by the concupiscent power which nature grants them for this purpose), whence it follows that the horse, when struck in some part of its body, yields on the same side in order to escape from the offence: And if there be any offence in the flanks by the spurs, when, nevertheless, he is struck in another part of the body, which is nobler than the flanks, with greater offence than the spurs, he will yield on that side, in which he will receive greater offence. |

[172.3] Essendo dunque naturale di tutti gli animali il fuggir le cose, ch’apportano danno al ben’essere loro (percioche sono mossi dalla concupisceuole potenza, à [173.1] questo fine conceduta loro dalla natura) di quì nasce, che il Cavallo percosso in qualche parte del corpo, cede da quell’istessa banda per allontanarsi dall’offesa: & se neme sarà offesa ne’fiáchi da gli sproni, quando nondimeno egli sarà percosso in un’altra parte del corpo, che de’fianchi sia più nobile, con maggior offesa di quella, che fanno gli sproni, cederà da quella parte, nella quale riceverà maggior offesa. | |

The enemy, therefore, when he is on horseback, will try to strike the opposite side, putting the horse to flight; or he will try to take away the right hand of the horse in order to attack it with his sword. But he who fights on foot will seek to flee from that side with his own right hand, in order to get away from the enemy’s attack, and to approach the opposite side, as this figure shows. |

[173.2] Il nemico dunque poso à cavallo cercherà di urtare il contrario, mettendo il cavallo in fuga: overo cercherà di levare al medesimo la mano diritta, per poterlo ferire con la sua spada. Ma colui, che combatterà à piedi, chercherà di fuggir quella parte, col & dalla sua propria diritta, affine d’allontanarsi dalla ferita nemica, & approssimarsi al contrario: come dimostra questa figura. | |

In the same way, since the horse will never be able to strike us with its natural motion except by its right, we will always have to ride to the horse’s right: thus we will prevent the enemy from seeing us, who will be on horseback: and standing in mid-step, and united in strength, and placed with the sword outstretched, out of our body, and with the cloak drawn in the fist, so that, if we can deprive ourselves of it, we shall, as soon as the horse is at a distance, make a cut in the horse’s muzzle, or a thrust in the same place, passing from the right foot, followed by the left foot, to our right sides, and attacking the reins with a transverse blow. Then, placing ourselves in the middle of the circumference, which forms the horse in the state in which a circle is drawn around its body, we will stand here without more condemning the enemy, but continuously attacking either the horse or the man. |

[175.1] PArimente, perche il cavallo non potrà mai se non per il diritto urtarci di moto suo naturale, avertiremo di presentarci sempre al diritto del cavallo: che cosi impediremo la vista al nemico, il qual si truoverà à cavallo: & fermi in mezo passo, & uniti in forza, & posti có la spada distesa, fuori del nostro corpo, & có la cappa imbracciata nel pugno in modo, che bisognando se ne potiamo privare, subito, che il cavallo arriverà in distantia, tiraremo un taglio nel muso d’esso cavallo, overo una púta in quel medesimo tépo, passádo dal piede diritto, seguito dal manco alle nostre parti diritte, & ferendo d’un riverso traversale nelle redini. Poi mettédosi nel cétro della circonferenza, che forma il cavallo in stato, quádo có un circolo si firi il suo corpo, qui staremo séza più abbádonar il nemico, có ferir di cótinuo ò il cavallo, ò l’huomo. | |

It will also be possible to frighten the horse when it is at a distance with the cloak, or to pull it over the head, making the same passes and attacks. |

[175.2] Potrassi anchora in quel tempo, che il cavallo arriverà in distanza, spaventarlo có la cappa; overo tirarglie la sopra la testa, col far l’istesse passate, & ferite. | |

It will also be necessary to use the left hand on the bridle, or with the same hand to leverage his foot, and thus to dismount him. |

[175.3] S’avertirà ancho di dar della mano manca nella briglia; overo con la medesima mano dargli lieva sotto il suo piede; & cosi scavalcarlo. | |

And if the horse should pass against him, it will be necessary to make a cut in the bridle. |

[175.4] Et caso, che il cavallo contra passasse, se gli doverà all’hora tirare un taglio à i garetti. |

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Images | Bibliothèque nationale de France | ||

| Translation | Nicola Boyd | Rules of many knightly armies | |

| Transcription | Nicola Boyd | Index:Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii (Federico Ghisliero) |

Additional Resources

The following is a list of publications containing scans, transcriptions, and translations relevant to this article, as well as published peer-reviewed research.

- Anglo, Sydney (1994). "Sixteenth-century Italian drawings in Federico Ghisliero's Regole di molti cavagliereschi essercitii." Apollo 140(393): 29-36.

- Gotti, Roberto (2023). "The Dynamic Sphere: Thesis on the Third State of the Vitruvian Man." Martial Culture and Historical Martial Arts in Europe and Asia: 93-147. Ed. by Daniel Jaquet; Hing Chao; Loretta Kim. Springer.

References

- ↑ Mentioned on p. +ⅱ of his dedication to Ranuccio and again on p. 94.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Anglo 1994, p. 30.

- ↑ See pp. 7-9. See also Gotti 2023, pp. 130-133.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cavagliereschi is Corsican for "chivalrous", while the Italian is "knightly".

- ↑ La gratia is Catalan for "grace".

- ↑ Ghisliero is telling his reader that he is a soldier not a civilian swordsman, so it will have a different perspective to others, hence his later comments on siege craft. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ This and the previous paragraph are commending the work to the patron, justifying the work’s existence and its purpose, common in treatises of the period. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ It was common to refer to “ancients” in the justification of the art of swordsmanship. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ When ‘this art’ or ‘the art’ is referenced it means the art of fencing. [More expansively the ars militari (military arts) or for the more classical, the Arts of Mars, of which swordsmanship falls within.] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Further justification by demonstration of the benefits to those who practice the art in question, also common, especially referring to defense of the person and the realm. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The version dedicated to Antonino instead reads "...for the instruction of the Most Illustrious Lord Antonio Pio Bonello".

- ↑ Cavalier – cavaliere – knights – so indicating the noble nature of the art which he is presenting. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The Humours.

- ↑ Means sad.

- ↑ Means calm.

- ↑ Means optimistic.

- ↑ Means bad-tempered.

- ↑ Hot-tempered.

- ↑ Moti has a number of meanings in modern Italian aside from "motion", including "motorcycle, bike, watercraft, riot, scooter".

- ↑ The use of square brackets [] shows the insertion of the translator to aid in clarity of meaning throughout the document.

- ↑ Contextually, transportar is in modern Italian trasporto and has been translated such.

- ↑ Where the word operante which means the operator or the person taking action or more simply the will is used elsewhere, I translate it to fencer as operator has the wrong connotations in English for what Ghisliaro appears to wish to convey.

- ↑ This is an application of Aristotle’s Causes, in some ways more easily explained due to the application of the sword (though this could be my fencer’s brain), especially as it develops. Ghisliero uses seven rather than four as Aristotle does, or at least using the same method of explanation. [Henry Fox]

- ↑ The spelling of secóda is seconda in modern Italian. This shortening of words through the removal of ‘n’ is common in documents of the period.

- ↑ Public roads means the location is a public road.

- ↑ Of Vitruvius’ Ten Books on Architecture. [This same book is referenced in Thibault] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Or capacity.

- ↑ Flavius Vegetius Renatus' On Roman Military Matters is likely the text to which he is referring. Which was a fourth century commentary on the training of Roman legions harking back to older methods. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Onde is Catalan. It is dove in Italian. Both mean ‘where’ in English.

- ↑ A second century book written by a Roman in the Attica region which encompasses the city of Athens.

- ↑ Dodrans is a Latin contraction of de-quadrans which means “a whole unit less a quarter” or three-quarters.

- ↑ Referencing the ‘ancients’ for authority was commonly used by authors of the time to demonstrate their comprehensive knowledge of the subject. It is intended to add gravitas to the treatise.

- ↑ All’hora is Catalan. Modern Italian is al tempo.

- ↑ The Elder.

- ↑ Scriue is Catalan. Modern Italian is lui scrive.

- ↑ Scurzo, does not translate appropriately from Italian. As with a number of words in Ghisliero’s treatise, it is likely a Catalase word or a unique spelling. Analysis of other treaties such as Jarod Kirby’s Italian Rapier Combat (Kirby, 2004) shows the following two definitions, on page 14 of the text, of a similar sound word that is contextually a more likely approximation of what scurzo means; “Scanso, A voidance, any evasive manoeuvre that moves the body of the direct line” and “Scanso del pie dritto, A voidance made by moving the right foot slightly off the direct line while turning the body.” So for the purposes of this translation, scurzo will mean in this text the middle stance as shown in Figure 3, i.e. a partial voiding stance halfway between perspective and profile.

- ↑ "Perspective" means front facing forward.

- ↑ Also could be interpreted as "figure".

- ↑ George Silver’s theory of the time for the hand and foot from his 1599 text Paradoxes of Defense mirrors this framework. [note from Henry Fox] (Silver, 1599)

- ↑ Et is Latin for ‘and’ in English and e in Italian.

- ↑ This is not an exact translation – it is the best approximation based on context.

- ↑ Balancia translates into ‘balance’.

- ↑ Membro translates to ‘member’, but in English a better word is limb.

- ↑ ò á mano manca la fontanella directly translates to something like ‘the hand missing the fontanelle’. This made no contextual sense, so it has been translated to ‘from the fountain of the body’ as fonta can mean ‘source’ in modern Italian. In the it states that “Fontánella, a little fountaine. Also a fontanell or cauterie [something to cauterise wounds], or rowling [turning round about, whirling or turning round], used also for the chiefe vein of a man’s body.” (Florio, 1611)

- ↑ ‘Perspective’ is forward facing as can be seen in Figure 3.

- ↑ No good translation found, contextually translating spatio to ‘space’.

- ↑ Polykleitos's Doryphoros is an early example of this position called contrapposto. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polykleitos for examples of sculptures with this stance. (Wikipeadia, 2021)

- ↑ Polykleitos wrote a lost treatise called ‘Artistic canons of body proportions’ in 5th Century Greece which provided a reference for standard body proportions. For more information https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artistic_canons_of_body_proportions (Wikipeadia, 2021)

- ↑ The act or process of passing across, over, or through.

- ↑ Aristotle’s fifth book of the Physica, which considers how motion occurs. “Book V classifies four species of movement, depending on where the opposites are located. Movement categories include quantity (e.g. a change in dimensions, from great to small), quality (as for colours: from pale to dark), place (local movements generally go from up downwards and vice versa), or, more controversially, substance. In fact, substances do not have opposites, so it is inappropriate to say that something properly becomes, from not-man, man: generation and corruption are not kinesis in the full sense.” (Aristotle, Physica (Book 5), (384–322 BC) 2007) “Generally things which come to be, come to be in different ways: (1) by change of shape, as a statue; (2) by addition, as things which grow; (3) by taking away, as the Hermes from the stone; (4) by putting together, as a house; (5) by alteration, as things which ‘turn’ in respect of their material substance.” Book 1, Physica, Aristotle (Aristotle, Physica (Book 1), (384-322 BC) 2007)

- ↑ Change of shape.

- ↑ By addition or by growing.

- ↑ Also taking away or removing.

- ↑ Putting things together or building.

- ↑ Change of material substance or alteration of its substance.

- ↑ “Three kinds of motion - qualitative, quantitative, and local” Book 5, Physica, Aristotle (Aristotle, Physica (Book 5), (384–322 BC) 2007)

- ↑ This same concept is present in Chapter 5 ‘Of tempo’ in Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli’s 1610 publication Gran Simulacro dell'Arte e dell'Uso della Scherma and can be translated into the actions of the fencer undertaking the correct movements - from ward (stillness) to attack or defence (movement) to ward (stillness) again. It propounds that the fencer should always end an action in a ward. The same concept is raised in Angelo Viggiani dal Montone’s 1551 (published 1575) text Lo Schermo d'Angelo Viggiani (Montone, 1575) and Antonio Manciolino’s 1531 Opera Nova (Manciolino, 1531).

- ↑ "Violence" in this instance means outside force or against nature. The same concepts of natural and violent actions are used in Iberian swordsmanship, and they take higher guards to take advantage of this principle. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Springimento is likely Springáre means ‘yarke, kicke or winze’ (Florio, 1611). Which likely means in context a preparation or a marshalling of position prior to deployment.

- ↑ Fighting at the barriers was a form of tournament bout usually performed by armoured combatants in which: a fence, a barrier, was imposed between fencers, combatants fought over the fence, and blows below the waist did not count as tournament points. [note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ Bases mean "legs". I have used "legs" wherever relevant in the translation.

- ↑ “Lacertoi, the arme from the elbow to the pitch of the shoulder. Also the brawne of sinnewes or muskles of a mans armes or legges. Also a Lizard. Also a Muskle because it is like a Lizard. Also a certain disease in a harse amongs the muskles and sinnuewes. Also a fish that grunteth as a Hog. Some have taken it also for a makrell fish.” (Florio, 1611) Thus lacertoi will be translated as the arm from the elbow to the shoulder joint.

- ↑ Keeping the elbow near the body.

- ↑ “Rascetta, the wrist of one’s hand. Also a kind of fine silke-rash.” (Florio, 1611)

- ↑ Direct translation is ‘good blade’.

- ↑ Costa “the back of a knife or weapon.” (Florio, 1611) There isn’t a common English equivalent which is a single word.

- ↑ This is consistent with Giacomo di Grassi’s treatise Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l'Arme (Grassi, 1570) which states that there is more power existing at the circumference of a circle than there is closer to the centre. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Debole refers to the half of the blade from tip of the blade to one third down towards the hilt.

- ↑ Forte refers to the first third of the blade from the hilt to towards the tip.

- ↑ Placing the edge over the debole like this is the basis of the Italian gaining stringere of the sword, or the Spanish atajo. It's used to close and control the line to prevent the opponent from hitting us. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí]

- ↑ Here Ghisliero’s methods conforms to common Italian approaches of defence to: always counter an opponent’s attacks with consideration for returning the attack, always attack with concern for defence, and not attack unless secure against the opponent’s attack. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Justifications for use of the cut seem to be relatively rare in fencing treatise of the time. Ghisliero’s justifications may even be unique. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The same justification for the thrust is given for the thrust being used by the legionary with the gladius, remaining more covered and it being more deadly than the cut. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Fendente means vertical cut.

- ↑ Traversale – transversal or diagonal cut [sometimes squalembrato for downward or falso if rising] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Tondo – horizontal cut

- ↑ Dritti – straight/forward [forehand cut, or natural cut, sometimes called mandritta] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Roversi – reverse [backhand or cross-wise cut] [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The division for the cuts on most diagrams usually go through the navel, or heart rather than the groin in most treatise of the period. [note from Henry Fox] Gérard Thibault d'Anvers’ 1630 treatise Academie de l'Espée ‘Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 2 – Comparing the ideal figure to a real Figure; Sword Scabbards’ shows the division at the naval (d'Anvers, Academie de l'Espée, 1630) – in the text it is found in the section that begins Pour venir à la Pratique de tout ce qui a efté discouru, or “To come to the Practice of all that has been discussed” (d'Anvers, Academie de l'Espée – Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 1 – Philosophical Discussion; Construction and Mathematics of the Circle; Concerning the Sword: Proper Length and Introduction explanation of the first plate., 1630). Salvator Fabris, in his 1606 text, Sienza e Pratica d’Arme also has an illustration in the section Discorso sopra laprima guardia formata nel cauare la spada del fodero or “Discourse in the first guard formed in pulling the sword from the scabbard” demonstrates the where cuts should be made and these also shows the division at the navel rather than the groin. (Fabris, 1606)

- ↑ Diritto ridoppiato literally means right redoubled or a falso traversale meaning a diagonal rising cut.

- ↑ Stramazzóne means a circular cut where the hand is the centre of rotation for the cut. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí] Florio describes it as ‘Stramazzóne, a downe-right blow. Also a rap, a cuffe or wherret on the cheeke.” (Florio, 1611)

- ↑ ‘Molinello, or Molinelli means a circular cut. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí] As an aside, the Molinello for flags described in Francesco Fernando Alfieri’s 1638 treatise La Bandiera “The molinello is delightful. To perform it comfortably, you should have the standard in your right hand. You complete a full turn above the head, then throw it up in the air, catching it around the middle of the standard as the figure shows. The molinello is then turned towards the rear foot. After several rotations, as the hand becomes fatigued, you should grip the butt of the flag with your other hand and repeat the same lesson, again throwing it in the air as described above.” (Alferi, 1638)

- ↑ ‘World’ is translated from the word Mondo which means “the world, the universe. Also, a Mound or Globe, as Princes hold in their hands. Also, cleane, cleansed, pure, neate, spotlesse, purged. Also, pared, pilled. Also, winnowed, &c. Also, as we say, a world, a multitude or great quantitie.’ (Florio, 1611)

- ↑ Fendente tondo means the upper half of the circle as shown in figure 6B. When speaking of the reverses, he is speaking of the lower half of the circle in figure 6B.

- ↑ ‘Segáre, to sawe. Also to part, to cut or devide through the middle.’ (Florio, 1611)

- ↑ ‘Riversa’ [singular] t de’roversi, which means ‘to turn around, a reversion, reverting, reverse or a backblow. A powering down or overwhelmed’ – in short the riversa is a back-hand. (Florio, 1611) Note how even the cut from the wrist is aided by motion of the body, no doubt using the feet to move the body as the cut is made as well, all in their correct motion, to affect the cut. [Note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Imbroccata means a descending thrust. Stoccata, means a violent thrust ascending or rising. Punta riversa means a reverse thrust with the point of the sword.

- ↑ “Auentáta, a hurling, looke Auentáre.” (Florio, 1611) “Auentáre, to hurle, to fling, to dart or cast with violence. Also, to leape or seaze greedily upon, to souse downe as a hawke, also to fill or puff with winde.” (Florio 1611 Dictionary). Therefore imbroccata aventata or imbroccata aventate means to violently attack using a thrust of the rapier over the dagger.

- ↑ The first two lines on the page are printed, but the second two needed to be drawn in by the artist.

- ↑ Here the page numbers jump from 35 to 38, correcting the error of having two 32s and 33s

- ↑ This is the reason that the direct thrust from the shoulder in a straight line is the longest and most preferable and the reason to learn to thrust straight rather than aiming up toward the head. [Note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 92.3 92.4 92.5 There is a gap in the text here for a circle to be drawn in.

- ↑ The effect of these causes is the fencer hitting their opponent using the technique. Poor technique means the fencer misses and/or dies.

- ↑ The material causes are the movements of the fencer’s body and sword.

- ↑ The formal cause is how the fencer uses the movements of the material cause.

- ↑ The factual cause is the fencer, with their measurements and proportions, and their ability to perform the material causes.

- ↑ The final cause is the actual technique the fencer is trying to achieve.

- ↑ Measure also often called distance. The measure of something is fluid due to the fencer’s, and their opponent’s, relative proportions in each combat and other considerations regarding weaponry. “The Spanish attempt to make it more certain by using proportionality, measuring against the length of the individual.” [note by Henry Fox] Gérard Thibault d'Anvers 1628 treatise Academie de l'Espée (d'Anvers, Academie de l'Espée, 1630) “…the Distances and Instances (i.e. steps in the process of fighting) to be observed in training (which are the basic foundations and support for all the following parts) proceed from the proportions of Man, therefore without this same awareness, they cannot be duly comprehended, nor practiced with confidence. And the same goes for the Steps and Approaches, short and long, required by the variety of positions in the performance of these Exercises. From which it is apparent that one must begin with a good knowledge of the proportion of limbs and body parts, that one may at least be able to make some reasonable judgement on the reach of each movement, proportionally to the limb, or limbs, on which the movement depends, and from which it must be continued, ended, turned, returned, released, bound, or changed in a thousand different ways.” (d'Anvers, Academie de l'Espée - – Book 1 – Tableau/Plate 1 –Philosophical Discussion; Construction and Mathematics of the Circle; Concerning the Sword: Proper Length and Introduction explanation of the first plate., 1630)

- ↑ Approximately 46 to 50 inches or 117cm to 127cm.

- ↑ Approximately 69 to 75 inches or 175cm to 191cm.

- ↑ Distance can be measured by Time, and Time measured by Distance so in effect one is the other, and every action toward or away from an opponent is measured in both Time and Distance; he seems to say much the same thing further along. [note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ Aristotelian motion is the consideration of “a stillness and motion” and is used by Capo Ferro as a method of reading the opponent in Chapter 5 ‘Of Tempo’ (Cagli’, 1610) [note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ Obligatory motion is the beginning of second intention. The fencer moves in a particular way so that the opponent has to do something in response, and then the fencer can follow on with their plan. [Note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ I will start using tempo from this point on instead of time when describing time as a measure of distance, to differentiate between it and the common use of the word time. Following Ghisliero’s explanation of tempo, it will be easier to use tempo to encapsulate this meaning.

- ↑ Sometimes extended to botta lunga, depending on the author [note by Henry Fox].

- ↑ “Attack into preparation” is what it is called in modern nomenclature, catching the opponent while they are preparing to act. [note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ An action in half-time, because the action is in motion, thus not completed, interrupted. [note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ This is an important note; the sword is extended and the fencer is covered by the extension of the sword in a straight line. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Strongest third of the blade from the hilt toward the middle.

- ↑ Strongest third of the blade from the hilt toward the middle.

- ↑ Note the positions of the weapons relative to one another. This is consistent with the Aristotelian and the Iberian approaches. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ The position of the hand and blade position in this initial stage is vital to the techniques that will follow. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ This appears to be discussing taking the line or stringeri.

- ↑ A “reversed thrust” in this instance.

- ↑ ‘in presentia’ means the sword is on the line of engagement. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí]

- ↑ This explains the advantages of Ghisliero’s guard position, demonstrating that the guard is the foundation of a fencing system. [note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ Punta scavizzata means hollow point.

- ↑ Gobba means hump or hunchback.

- ↑ Puinta riversa is a spelling variation from punta riversa.

- ↑ Incapocchiato does not translate, it suggests the word incapacitate. Incapocchiársi means ‘to become a doult or logger-head, to take a foolish conceite’ (Florio 1611) It might also mean encompassing in modern Italian.

- ↑ Guardia di falcone means "falcon’s guard". This is what the Bolognese authors call guardia alta. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí]

- ↑ Coda longa, & larga or coda lunga e larga means "long and broad tail guard".

- ↑ scanso del corpo means void the body. Basically, these are the body turns we use to take the body off the line of engagement. [Note by Táriq ibn Jelal ibn Ziyadatallah al-Naysábúrí]

- ↑ Inquartata means quartering step. It is a voiding action of the body which closes the inside line.

- ↑ “Long and high tail” guard.

- ↑ The sequence of the combatant should always be ward – blow – ward, or stillness – motion – stillness, it is a common and practical method in quite a few treatises. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Examine di Grassi’s (Grassi, 1570) diagram of the thrust and movement of the arm for an example of this motion. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Nature means their passions.

- ↑ Parate – parade – often later used, especially in smallsword in place of ‘parry’. [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Mezzo mandritto means a half-leg cut.

- ↑ Mezzo riverso means a half-reversed cut.

- ↑ Garatusa is Spanish for thrust. In fencing it is a technique composed of nine movements, and the participation of two and three angles, that they make to [through, from] both parts [locations, sides], from the outside and from the inside, arrojando the sword with force to the sides, and from there they return to raise it [the sword] to wound with a thrust in the face or chest. It is not safe [sure]. (Ghost Sparrow Publications, 2021)

- ↑ Polykleitos's Doryphoros is an early example of this position called contrapposto. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polykleitos for examples of sculptures with this stance. (Wikipeadia, 2021)

- ↑ Pili (pilum or pila) was the javelin of which the Romans were armed with two along with their sword. [note by Henry Fox]

- ↑ Cortina means a long wall running level from one bulwark to another.

- ↑ A strada coperta is a close walk or passage made on the top of a counter-scarpe in which the besieged may cover themselves from the enemies (Florio 1610)

- ↑ Archibuseria likely is an alternative spelling of archibugiera, which are a wall with slits, in a fortress, through which a weapon can be fired.

- ↑ Riverso traversale means a transverse or diagonal blow during retreat. “It’s equivalent to a riversa squalembrato or falso manco, depending on whether ascending or descending.” [note from Henry Fox]

- ↑ Imbroccata aventata means a hurling or forceful thrust given over the dagger.

- ↑ Gabionate fortifications or fences made of Gabions – cages or baskets full of earth set with ordinance to hide and defend Cannoniers. (Florio 1611)

- ↑ Trincerone means a large, well-equipped trench.

- ↑ No translation of this word is available.

- ↑ Manca means missing, and probably means back or voided leg.

- ↑ This probably means that the sword has mechanical advantage in a thrusting position.

- ↑ Corda means rope or cord, but in this context means the diameter of the circle.

- ↑ ‘A reference to the ‘sword fist’ is made in Antonio Manciolino’s Opera Nova where it states “Of the narrow iron gate guard. The sixth guard is called “porta di ferro stretta”. In which the body must be arranged diagonally in such fashion that the right shoulder (as is said above) faces the enemy, but both the arms must be stretched out to encounter the enemy, so that the sword arm is extended straight down in the defense of the right knee, and so that the sword fist be near and centered on the aforesaid knee.” (Wiktenauer, 2022) It is then clear that ‘sword’s fist’ means the hand holding the hilt of the sword.

- ↑ Cappa means both cloak and cape (there is no differentiation in Italian). I will use cloak for the purpose of consistency. The Spanish cloak or cape is short compared with what we normally consider to be a cloak. It is usually worn anywhere from below the shoulder blade length to the hip.

- ↑ Stringeremo appears to mean the same as stringere or a drawing close posture. Most commonly used as stringere la spada where using the stronger part of the sword you engage with the weaker part of the opponent’s sword and take the line or advantage so the point of the opponent’s sword can no longer strike you.