|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Nicoletto Giganti"

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

| below = | | below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

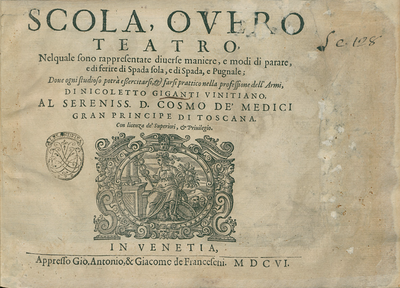

| − | '''Nicoletto Giganti''' (Niccoletto, Nicolat) was an [[nationality::Italian]] soldier and [[fencing master]] around the turn of the [[century::17th century]]. He was likely born to a noble family in Fossombrone in central Italy,<ref name="Terminiello 9"> | + | '''Nicoletto Giganti''' (Niccoletto, Nicolat) was an [[nationality::Italian]] soldier and [[fencing master]] around the turn of the [[century::17th century]]. He was likely born to a noble family in Fossombrone in central Italy,<ref name="Terminiello 9">Giganti 2013, p 9.</ref> and only later became a citizen of Venice.<ref>That he eventually became a Venetian citizen is indicated on the [[Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/5|title page]] of his 1606 treatise.</ref> Little is known of Giganti’s life, but in the dedication to his 1606 treatise he claims 27 years of professional experience, meaning that his career began in 1579 (possibly referring to service in the Venetian military, a long tradition of the Giganti family).<ref name="Terminiello 9"/> Additionally, the preface to his 1608 treatise describes him as a Master of Arms to the Order of Santo Stefano in Pisa, a powerful military order founded by Cosimo I de' Medici, giving some further clues to his career. |

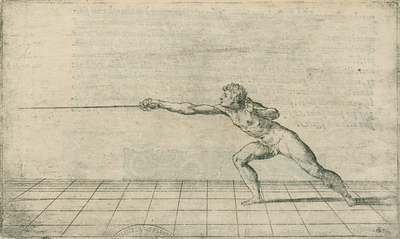

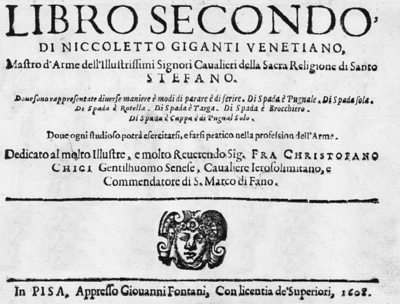

| − | In 1606, Giganti published a treatise on the use of the rapier (both single and with the dagger) titled ''[[Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti)|Scola, overo teatro]]'' ("School, or Theater"). It is dedicated to Cosimo II de' Medici. This treatise is structured as a series of progressively more complex lessons, and Tom Leoni opines that this treatise is the best pedagogical work on rapier fencing of the early 17th century.<ref> | + | In 1606, Giganti published a treatise on the use of the rapier (both single and with the dagger) titled ''[[Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti)|Scola, overo teatro]]'' ("School, or Theater"). It is dedicated to Cosimo II de' Medici. This treatise is structured as a series of progressively more complex lessons, and Tom Leoni opines that this treatise is the best pedagogical work on rapier fencing of the early 17th century.<ref>Giganti 2010, p xi.</ref> It is also the first treatise to fully articulate the principle of the lunge. Giganti also promised in this book that he would publish a second volume, a pledge he made good on in 1608.<ref>This treatise was considered lost for centuries, and as early as 1673 the Sicilian master [[Giuseppe Morsicato Pallavicini]] stated that this second book was never published at all. See ''[[La seconda parte della scherma illustrata (Giuseppe Morsicato Pallavicini)|La seconda parte della scherma illustrata]]''. Palermo, 1673. p V.</ref> Titled ''[[Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti)|Libro secondo di Niccoletto Giganti]]'' ("Second Book of Niccoletto Giganti"), it is dedicated to Christofano Chigi, a Knight of Malta, and covers the same weapons as the first as well as rapier and buckler, rapier and cloak, rapier and shield, single dagger, and mixed weapon encounters. This text in turn promises additional writings on the dagger and on cutting with the rapier, but there is no record of further books by Giganti ever being published. |

| − | + | While Giganti's second book quickly disappeared from history, his first seems to have been quite popular: reprints, mostly unauthorized, sprang up many times over the subsequent decades, both in the original Italian and, beginning in 1619, in French and German translations. The 1622 edition of this unauthorized dual-language edition also included book 2 of [[Salvator Fabris]]' 1606 treatise ''[[Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme]]''<ref>It's possible that the 1619 did as well, but there are no surviving copies that include it so we have to assume it didn't.</ref> which, coupled with the loss of Giganti's true second book, is probably what has lead many later bibliographers to accuse Giganti himself of plagiarism.<ref>This accusation was first made by [[Johann Joachim Hynitzsch]], who attributed the edition to Giganti rather than Zeter and was incensed that he gave no credit to Fabris.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | While Giganti's second book quickly disappeared from history, his first seems to have been quite popular: reprints, mostly unauthorized, sprang up many times over the subsequent decades, both in the original Italian and, beginning in 1619, in French and German translations. | ||

== Treatise == | == Treatise == | ||

| − | Giganti, like many 17th century authors, had a tendency to write incredibly long, multi-page paragraphs which quickly become hard to follow. Jacob de Zeter's 1619 dual-language edition often breaks these up into more manageable chunks, and | + | Giganti, like many 17th century authors, had a tendency to write incredibly long, multi-page paragraphs which quickly become hard to follow. Jacob de Zeter's 1619 dual-language edition often breaks these up into more manageable chunks, and in this concordance his paragraph breaks have also been applied to the Italian and English. |

| − | A [http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/109AF678 copy of the 1628 printing] | + | A [http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/109AF678 copy of the 1628 printing] of the first book which now resides in the [[Österreichische Nationalbibliothek]] was extensively annotated by a contemporary reader. Its annotations are beyond the scope of this concordance, but they have been [http://www.rapier.at/2018/07/20/a-transcription-of-annotations-in-the-onb-copy-211216-c-of-scola-overo-teatro-by-nicoletto-giganti/ transcribed] by [[Julian Schrattenecker]] and [[Florian Fortner]], and incorporated into [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]'s translation in a [https://labirinto.ca/translations/ separate document]. |

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| Line 748: | Line 746: | ||

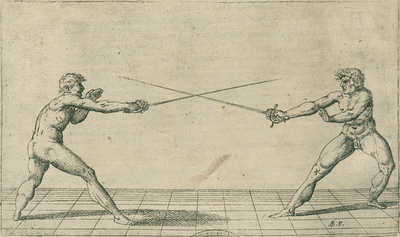

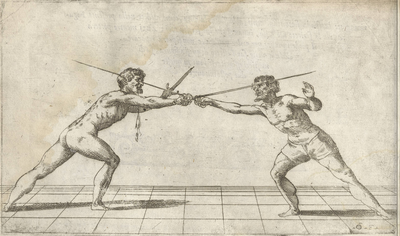

| <p>[46] ''The method of playing single sword against single sword with resolute thrusts''</p> | | <p>[46] ''The method of playing single sword against single sword with resolute thrusts''</p> | ||

| − | <p>In schools, there are many who resolutely come throwing thrusts, imbroccate, and cuts when they assail the enemy, giving no ''tempo'' and always throwing with fury and very great impetus. These things ordinarily confound and disorder every beautiful player and fencer, for which reason it is necessary to know how to defend oneself in such an occasion.</p> | + | <p>In schools, there are many who resolutely come throwing thrusts, ''imbroccate'', and cuts when they assail the enemy, giving no ''tempo'' and always throwing with fury and very great impetus. These things ordinarily confound and disorder every beautiful player and fencer, for which reason it is necessary to know how to defend oneself in such an occasion.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/61|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,234: | Line 1,232: | ||

| <p>'''Preface to the Lord Readers'''</p> | | <p>'''Preface to the Lord Readers'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>''It being the case that in my first book I discussed throwing the firm-footed thrust, and feints, and taught to defend against all the stoccate, in this, my second, I thought to be more universal, intending to teach you additional types of weapons and, more importantly, how all sorts of cuts are defended against and how they must be thrown, the method of passing with the foot, and everything in accordance with what I promised you in my First Book.''<p> | + | <p>''It being the case that in my first book I discussed throwing the firm-footed thrust, and feints, and taught to defend against all the ''stoccate'', in this, my second, I thought to be more universal, intending to teach you additional types of weapons and, more importantly, how all sorts of cuts are defended against and how they must be thrown, the method of passing with the foot, and everything in accordance with what I promised you in my First Book.''<p> |

<p>''It is necessary that someone who wishes to become perfect in the profession of arms not only know how to throw a thrust well, perform a beautiful feint, and pass well with both the right and left foot, but also that he know the counter to all these things—that is, how to gracefully defend against them. That given, someone who knows how to throw a thrust well and how to perform a pass but is then lacking in knowledge of how to defend can be said to know nothing, because if he disputes with another who knows how to throw a thrust as he does, both will be wounded. Thus, it is good to know how to throw a thrust and perform a pass but much better to know how to defend against it, as we will discuss in this book.''</p> | <p>''It is necessary that someone who wishes to become perfect in the profession of arms not only know how to throw a thrust well, perform a beautiful feint, and pass well with both the right and left foot, but also that he know the counter to all these things—that is, how to gracefully defend against them. That given, someone who knows how to throw a thrust well and how to perform a pass but is then lacking in knowledge of how to defend can be said to know nothing, because if he disputes with another who knows how to throw a thrust as he does, both will be wounded. Thus, it is good to know how to throw a thrust and perform a pass but much better to know how to defend against it, as we will discuss in this book.''</p> | ||

| Line 1,287: | Line 1,285: | ||

<p>If an unarmoured gentleman with only sword and dagger were by chance [attacked] by an armoured enemy with a heavy sword, attempting to parry with the dagger would be dangerous. This is because without gauntlets there is no doubt that if the hand catches it, the dagger will be thrown to the ground or, instead, the dagger will not withstand the great blow. Attempting to parry with the sword works well, but he will not be able to wound his adversary without notable danger because someone who is armoured has more courage than someone who is not, and more daringly drives himself forward and redoubles the cuts, which would endanger someone who is unarmoured. It can therefore be done in this way.</p> | <p>If an unarmoured gentleman with only sword and dagger were by chance [attacked] by an armoured enemy with a heavy sword, attempting to parry with the dagger would be dangerous. This is because without gauntlets there is no doubt that if the hand catches it, the dagger will be thrown to the ground or, instead, the dagger will not withstand the great blow. Attempting to parry with the sword works well, but he will not be able to wound his adversary without notable danger because someone who is armoured has more courage than someone who is not, and more daringly drives himself forward and redoubles the cuts, which would endanger someone who is unarmoured. It can therefore be done in this way.</p> | ||

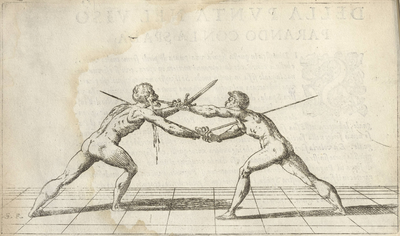

| − | <p>When the enemy throws the cut at your head, parry with the sword and dagger crossed as the figure shows, the dagger above and the sword below. In the same tempo, disengage the sword from under that of the enemy and throw a ''stoccata'' at his face, and return backward outside of measure. Parry and throw stoccate at his face in this way as many times as the adversary throws. A hundred cuts can be parried in this way and it is easy to wound him in the face because, throwing the cut, he comes forward with his face and head much more as the gentleman throws the ''stoccata'' as an imbroccata, extending the foot and then withdrawing outside of measure.</p> | + | <p>When the enemy throws the cut at your head, parry with the sword and dagger crossed as the figure shows, the dagger above and the sword below. In the same tempo, disengage the sword from under that of the enemy and throw a ''stoccata'' at his face, and return backward outside of measure. Parry and throw ''stoccate'' at his face in this way as many times as the adversary throws. A hundred cuts can be parried in this way and it is easy to wound him in the face because, throwing the cut, he comes forward with his face and head much more as the gentleman throws the ''stoccata'' as an ''imbroccata'', extending the foot and then withdrawing outside of measure.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|12|lbl=9|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|13|lbl=10|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|12|lbl=9|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|13|lbl=10|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,330: | Line 1,328: | ||

| <p>[9] '''The Method of Defending With the Sword Against the ''Riverso'' to the Leg'''</p> | | <p>[9] '''The Method of Defending With the Sword Against the ''Riverso'' to the Leg'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This is a safe way of parrying a ''riverso'' at the leg. While your enemy throws this ''riverso'' at you, parry with the edge of the sword, turning your wrist, and immediately throw a thrust by way of imbroccata at his face. It can occur that when you throw a ''stoccata'', your enemy parries it. In the instant he throws a ''riverso'' at your leg, parry with your sword in the above way, throw the ''stoccata'' at his face, and immediately return outside of measure.</p> | + | <p>This is a safe way of parrying a ''riverso'' at the leg. While your enemy throws this ''riverso'' at you, parry with the edge of the sword, turning your wrist, and immediately throw a thrust by way of ''imbroccata'' at his face. It can occur that when you throw a ''stoccata'', your enemy parries it. In the instant he throws a ''riverso'' at your leg, parry with your sword in the above way, throw the ''stoccata'' at his face, and immediately return outside of measure.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|22|lbl=19}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|22|lbl=19}} | ||

| Line 1,339: | Line 1,337: | ||

<p>In this, my Second Book, I did not intend to discuss cuts further because it would produce too large a volume if I wished to put all the ways they can be performed into figures. I will only briefly touch on all the ways that one can wound with cuts and how they must be defended against. Then, in another book that I will shortly publish, if it pleases the Lord, I will discuss the trickeries and deceptions that can be performed in throwing cuts. Therefore, I will say only this: In contending with or playing at arms, be advised not to throw both in the same tempo, but wait until the adversary’s cut to your leg or head has been defended from and then wound safely as said above. If the same enemy waits in guard for you to throw, however, you must throw at the part that appears most uncovered, taking care that your dagger or sword guards against the adversary’s sword while you throw, so that if he were also to throw in the same tempo you are able to parry and return outside of measure. I wish to teach you to defend yourself with cuts against two or three people in cases of necessity. If you are assaulted by two people, it often happens that if you throw a ''mandritto'' at one, the other throws at you in that tempo, and if you throw a ''stoccata'' at the other, you encounter a ''stoccata'' from the first. You would thus quickly find yourself dead, as has happened to many. Therefore, in order to defend yourself and offend, I want you to hold the sword high as if to throw a ''mandritto''. If both were to throw a ''stoccata'' at you in the same instant, throw a ''mandritto'' and then a ''riverso'' onto the swords. The ''mandritto'' must be thrown in this way: So that it almost wounds the enemy’s neck and arrives at your left side to wound again. This manner of ''mandritto'' produces two effects: it wounds and parries in the same tempo. The ''mandritto'' thrown, the ''vita'' and foot can be drawn back along with putting the sword under the left arm in order to throw the ''riverso''. Then immediately throw the ''riverso'' in this way: So that it begins wounding the adversary’s neck and arrives to wound anew at your right flank—which is to say the ''mandritto'' and ''riverso'' wound in the form of a cross. One parries and wounds in this way because your sword must necessarily find the enemies’ weapons, taking care that such ''mandritti'' and ''riversi'' must be thrown long, strong, quick, and wide, and must never stop at all. Rather, as soon as the ''mandritto'' is thrown it is necessary that the ''riverso'' occurs, and thus, on the contrary, as soon as the ''riverso'' is thrown do not delay at all in throwing the ''mandritto''. In conclusion, all must be performed like a wheel.</p> | <p>In this, my Second Book, I did not intend to discuss cuts further because it would produce too large a volume if I wished to put all the ways they can be performed into figures. I will only briefly touch on all the ways that one can wound with cuts and how they must be defended against. Then, in another book that I will shortly publish, if it pleases the Lord, I will discuss the trickeries and deceptions that can be performed in throwing cuts. Therefore, I will say only this: In contending with or playing at arms, be advised not to throw both in the same tempo, but wait until the adversary’s cut to your leg or head has been defended from and then wound safely as said above. If the same enemy waits in guard for you to throw, however, you must throw at the part that appears most uncovered, taking care that your dagger or sword guards against the adversary’s sword while you throw, so that if he were also to throw in the same tempo you are able to parry and return outside of measure. I wish to teach you to defend yourself with cuts against two or three people in cases of necessity. If you are assaulted by two people, it often happens that if you throw a ''mandritto'' at one, the other throws at you in that tempo, and if you throw a ''stoccata'' at the other, you encounter a ''stoccata'' from the first. You would thus quickly find yourself dead, as has happened to many. Therefore, in order to defend yourself and offend, I want you to hold the sword high as if to throw a ''mandritto''. If both were to throw a ''stoccata'' at you in the same instant, throw a ''mandritto'' and then a ''riverso'' onto the swords. The ''mandritto'' must be thrown in this way: So that it almost wounds the enemy’s neck and arrives at your left side to wound again. This manner of ''mandritto'' produces two effects: it wounds and parries in the same tempo. The ''mandritto'' thrown, the ''vita'' and foot can be drawn back along with putting the sword under the left arm in order to throw the ''riverso''. Then immediately throw the ''riverso'' in this way: So that it begins wounding the adversary’s neck and arrives to wound anew at your right flank—which is to say the ''mandritto'' and ''riverso'' wound in the form of a cross. One parries and wounds in this way because your sword must necessarily find the enemies’ weapons, taking care that such ''mandritti'' and ''riversi'' must be thrown long, strong, quick, and wide, and must never stop at all. Rather, as soon as the ''mandritto'' is thrown it is necessary that the ''riverso'' occurs, and thus, on the contrary, as soon as the ''riverso'' is thrown do not delay at all in throwing the ''mandritto''. In conclusion, all must be performed like a wheel.</p> | ||

| − | <p>To throw this kind of cut, it is necessary to practise throwing ''mandritti'' and ''riversi'' in order to prepare the arm and quicken and invigorate the leg by throwing two or three hundred cuts and, likewise, ''riversi'', without ever stopping. Everyone will thus also be able to parry all the stoccate of three or four, both wounding and keeping their enemies at a sword’s length by throwing long, quick, strong, and wide. This kind of cut has this property: If a gentleman were to find himself unarmoured with only a sword and is assaulted by his enemy, fully armoured and with sword and dagger who comes at him with stoccate and imbroccate, he will be able to defend his body in this way: He holds his sword as I said above, high as if to throw a cut, and while his enemy throws a cut he throws a ''mandritto'' at the enemy’s sword and immediately throws a ''riverso'' at his head or legs, then immediately returns backward outside of measure. This is for the reason that, throwing a ''mandritto'' onto the sword while the enemy throws the ''stoccata'', his sword will be thrown to the ground, and before [the enemy] recovers [the gentleman] will be able to throw not a single ''riverso'', but two or three, then return backward. If the enemy were to throw a hundred stoccate in a row at him, [the gentleman] will parry them all safely and be able to wound his enemy with the ''riverso'' to the face or leg. Furthermore, the cut thrown in this manner also has this property: That if an adversary were to throw said imbroccata or ''stoccata'', throwing a ''mandritto'' to parry it and finding the enemy’s arm weakened from having thrown the ''stoccata'', it will be easy to make the sword fall from his hand. Therefore, I urge everyone to practise this method of throwing cuts because it defends and wounds safely and other [methods] do not, as they only wound but do not defend if the enemy were to throw in the same tempo.</p> | + | <p>To throw this kind of cut, it is necessary to practise throwing ''mandritti'' and ''riversi'' in order to prepare the arm and quicken and invigorate the leg by throwing two or three hundred cuts and, likewise, ''riversi'', without ever stopping. Everyone will thus also be able to parry all the ''stoccate'' of three or four, both wounding and keeping their enemies at a sword’s length by throwing long, quick, strong, and wide. This kind of cut has this property: If a gentleman were to find himself unarmoured with only a sword and is assaulted by his enemy, fully armoured and with sword and dagger who comes at him with ''stoccate'' and ''imbroccate'', he will be able to defend his body in this way: He holds his sword as I said above, high as if to throw a cut, and while his enemy throws a cut he throws a ''mandritto'' at the enemy’s sword and immediately throws a ''riverso'' at his head or legs, then immediately returns backward outside of measure. This is for the reason that, throwing a ''mandritto'' onto the sword while the enemy throws the ''stoccata'', his sword will be thrown to the ground, and before [the enemy] recovers [the gentleman] will be able to throw not a single ''riverso'', but two or three, then return backward. If the enemy were to throw a hundred ''stoccate'' in a row at him, [the gentleman] will parry them all safely and be able to wound his enemy with the ''riverso'' to the face or leg. Furthermore, the cut thrown in this manner also has this property: That if an adversary were to throw said ''imbroccata'' or ''stoccata'', throwing a ''mandritto'' to parry it and finding the enemy’s arm weakened from having thrown the ''stoccata'', it will be easy to make the sword fall from his hand. Therefore, I urge everyone to practise this method of throwing cuts because it defends and wounds safely and other [methods] do not, as they only wound but do not defend if the enemy were to throw in the same tempo.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|24|lbl=21|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|25|lbl=22|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|26|lbl=23|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|24|lbl=21|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|25|lbl=22|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|26|lbl=23|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,347: | Line 1,345: | ||

| <p>[11] '''The Method of Parrying a ''Stoccata'' that Comes''' at the Face on the Outside</p> | | <p>[11] '''The Method of Parrying a ''Stoccata'' that Comes''' at the Face on the Outside</p> | ||

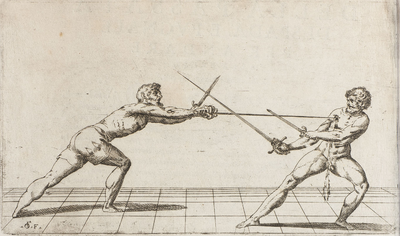

| − | <p>In my first book I promised you that I would discuss how one passes with the foot in order to attempt to wound, being that in it I only spoke of the firm-foot, with which someone knows how to play well and recognize the tempo. He will do those same things when passing. Therefore, I ready myself to keep the promise. If your enemy were to throw at you, whatever blow he wishes, either thrust or cut, you can pass with the foot, knowing how to take the tempo. When you have passed, disengage the sword, throw two or three stoccate, and immediately return backward outside of measure, as you will learn in this figure, which shows you that, being in guard with your right foot forward, if your enemy were to throw a thrust on the outside of your dagger, in the same tempo you parry with the dagger, pass your left foot forward, and throw the ''stoccata'' in the same tempo, as the figure shows. Once you have thrown the ''stoccata'', it is necessary to withdraw the ''vita'', disengage the sword, keep the dagger firm on your enemy’s sword, throw two or three stoccate, and withdraw outside of measure. Take care in leaping backward, however, to secure yourself with your sword on his so that in returning outside of measure your adversary does not throw you a ''stoccata'' where you are most uncovered, thus wounding you both, as often occurs. If in returning backward you place your sword over his, however, he will not be able to wound you. Therefore, I urge you in all passes you perform to keep your sword over the enemy’s until you are outside of measure again, because someone who knows how to perform a pass but does not know how to then disengage the sword and wound again or to escape from the enemy’s weapons can be said to be ignorant of this profession. This is for the reason that if they pass with the foot they come to grips and both end up in no small amount of danger if they do not know the method of doing so. Performing these kinds of passes, then, is not for everyone. Rather, it is only for those who are strong and dexterous, who know how to play from a firm foot well so that they recognize the tempo and measure, and who are well-practised, because it cannot be said that I wish to pass at the onset. First it is necessary to see what the enemy does, the tempo and occasion must be taken according to this, recognizing when it is time to throw from a firm foot, when from a pass, when with a ''stoccata'', and when with a cut.</p> | + | <p>In my first book I promised you that I would discuss how one passes with the foot in order to attempt to wound, being that in it I only spoke of the firm-foot, with which someone knows how to play well and recognize the tempo. He will do those same things when passing. Therefore, I ready myself to keep the promise. If your enemy were to throw at you, whatever blow he wishes, either thrust or cut, you can pass with the foot, knowing how to take the tempo. When you have passed, disengage the sword, throw two or three ''stoccate'' , and immediately return backward outside of measure, as you will learn in this figure, which shows you that, being in guard with your right foot forward, if your enemy were to throw a thrust on the outside of your dagger, in the same tempo you parry with the dagger, pass your left foot forward, and throw the ''stoccata'' in the same tempo, as the figure shows. Once you have thrown the ''stoccata'', it is necessary to withdraw the ''vita'', disengage the sword, keep the dagger firm on your enemy’s sword, throw two or three ''stoccate'', and withdraw outside of measure. Take care in leaping backward, however, to secure yourself with your sword on his so that in returning outside of measure your adversary does not throw you a ''stoccata'' where you are most uncovered, thus wounding you both, as often occurs. If in returning backward you place your sword over his, however, he will not be able to wound you. Therefore, I urge you in all passes you perform to keep your sword over the enemy’s until you are outside of measure again, because someone who knows how to perform a pass but does not know how to then disengage the sword and wound again or to escape from the enemy’s weapons can be said to be ignorant of this profession. This is for the reason that if they pass with the foot they come to grips and both end up in no small amount of danger if they do not know the method of doing so. Performing these kinds of passes, then, is not for everyone. Rather, it is only for those who are strong and dexterous, who know how to play from a firm foot well so that they recognize the tempo and measure, and who are well-practised, because it cannot be said that I wish to pass at the onset. First it is necessary to see what the enemy does, the tempo and occasion must be taken according to this, recognizing when it is time to throw from a firm foot, when from a pass, when with a ''stoccata'', and when with a cut.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|28|lbl=25|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|29|lbl=26|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|30|lbl=27|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|28|lbl=25|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|29|lbl=26|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|30|lbl=27|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,355: | Line 1,353: | ||

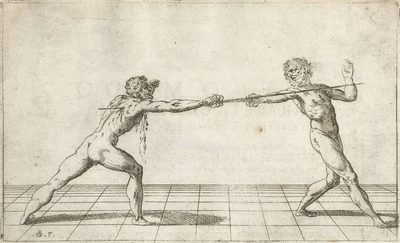

| <p>[12] '''The Method of Performing a Pass with the Foot when the Enemy''' Throws a Thrust on the Inside at the Face</p> | | <p>[12] '''The Method of Performing a Pass with the Foot when the Enemy''' Throws a Thrust on the Inside at the Face</p> | ||

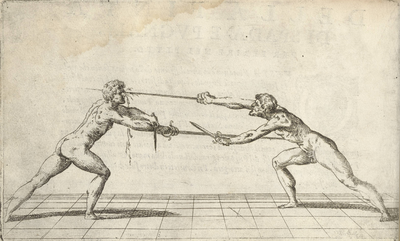

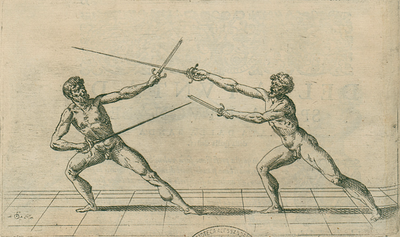

| − | <p>This figure shows you that if you are in guard with your right foot forward and your enemy throws a thrust at your face, you must parry with the dagger and in the same tempo pass with the left foot and throw a ''stoccata'' at the flank, as the figure shows, and immediately secure yourself well over your feet and disengage your sword and throw two or three stoccate while holding your dagger firm over your enemy’s sword. If he were to try to disengage it in order to throw additional blows, it is necessary that you follow it with the dagger while continuing to throw stoccate and return backward outside of measure, securing yourself with your sword over his.</p> | + | <p>This figure shows you that if you are in guard with your right foot forward and your enemy throws a thrust at your face, you must parry with the dagger and in the same tempo pass with the left foot and throw a ''stoccata'' at the flank, as the figure shows, and immediately secure yourself well over your feet and disengage your sword and throw two or three ''stoccate'' while holding your dagger firm over your enemy’s sword. If he were to try to disengage it in order to throw additional blows, it is necessary that you follow it with the dagger while continuing to throw ''stoccate'' and return backward outside of measure, securing yourself with your sword over his.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|32|lbl=29}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|32|lbl=29}} | ||

| Line 1,383: | Line 1,381: | ||

| <p>[16] '''The Method of Passing When the Enemy has Uncovered His Chest'''</p> | | <p>[16] '''The Method of Passing When the Enemy has Uncovered His Chest'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>If your enemy has uncovered his chest, his sword high or low, and stands in guard in order to wait for you, in a narrow guard with the sword inside go to bind him little by little until you are at measure. When you are at the designated point, pass in the above way, first throwing the sword arm where he is most uncovered, then passing with the foot, securing yourself from the enemy sword with your dagger as above, throwing the same stoccate and escaping in the same way. In this Second Book I did not wish to produce more than these three lessons for wounding when the enemy is in guard waiting for you, which, if I am not mistaken, will illuminate for you how to understand proceeding to pass in all guards that the enemy can produce by making use of the said method.</p> | + | <p>If your enemy has uncovered his chest, his sword high or low, and stands in guard in order to wait for you, in a narrow guard with the sword inside go to bind him little by little until you are at measure. When you are at the designated point, pass in the above way, first throwing the sword arm where he is most uncovered, then passing with the foot, securing yourself from the enemy sword with your dagger as above, throwing the same ''stoccate'' and escaping in the same way. In this Second Book I did not wish to produce more than these three lessons for wounding when the enemy is in guard waiting for you, which, if I am not mistaken, will illuminate for you how to understand proceeding to pass in all guards that the enemy can produce by making use of the said method.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|40|lbl=37}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|40|lbl=37}} | ||

| Line 1,390: | Line 1,388: | ||

| <p>[17] '''The Method of Parrying the Cut at the Head and Passing with the Foot, Crossing the Sword and Dagger'''</p> | | <p>[17] '''The Method of Parrying the Cut at the Head and Passing with the Foot, Crossing the Sword and Dagger'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This figure shows you that if your enemy were to throw a cut at your head, you must parry crossed, pass with the foot, give him a ''riverso'' to the leg along with three or four stoccate, and escape. It is done in this way: Standing in guard with the right foot forward, forward so that your enemy throws a cut at your head, cross the sword and dagger and go to meet the ''mandritto'', passing with your left foot as you see in the figure, and immediately throw the ''riverso'' at his leg along with pulling back the ''vita'', so that the adversary’s sword will remain on your dagger, throw three or four stoccate, and return outside of measure, securing your sword over his in the above way.</p> | + | <p>This figure shows you that if your enemy were to throw a cut at your head, you must parry crossed, pass with the foot, give him a ''riverso'' to the leg along with three or four ''stoccate'', and escape. It is done in this way: Standing in guard with the right foot forward, forward so that your enemy throws a cut at your head, cross the sword and dagger and go to meet the ''mandritto'', passing with your left foot as you see in the figure, and immediately throw the ''riverso'' at his leg along with pulling back the ''vita'', so that the adversary’s sword will remain on your dagger, throw three or four ''stoccate'', and return outside of measure, securing your sword over his in the above way.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|42|lbl=39}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|42|lbl=39}} | ||

| Line 1,400: | Line 1,398: | ||

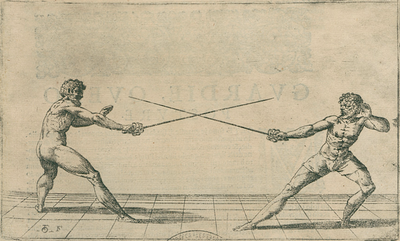

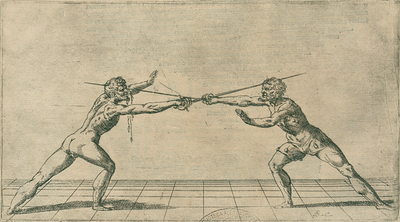

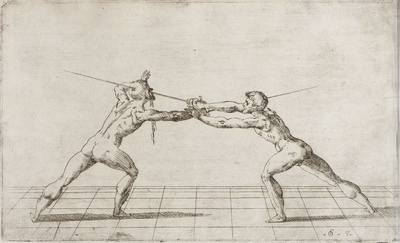

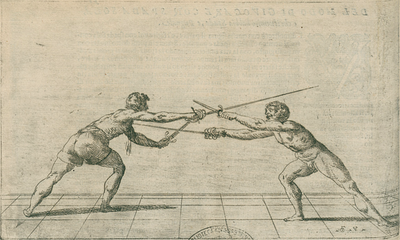

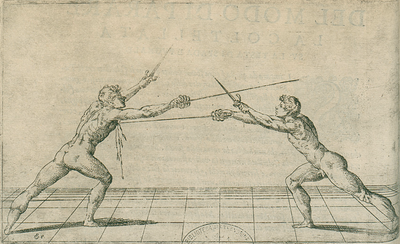

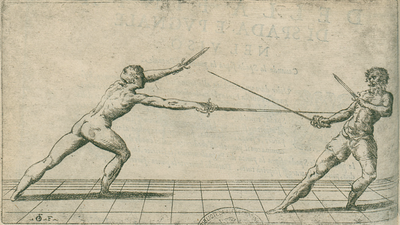

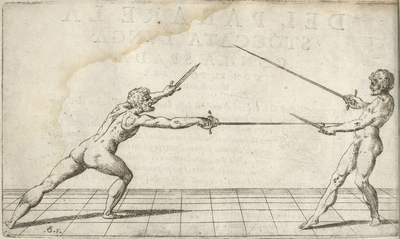

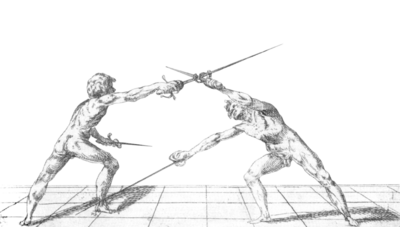

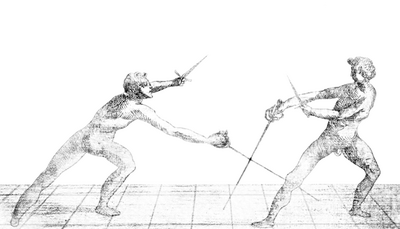

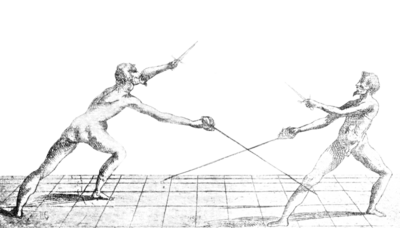

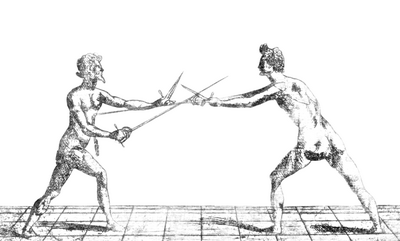

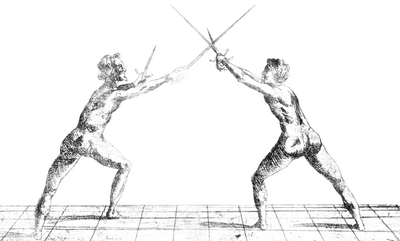

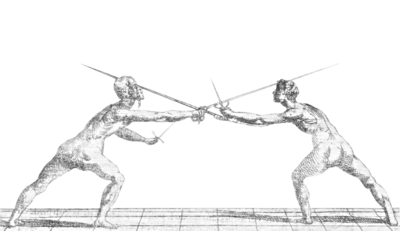

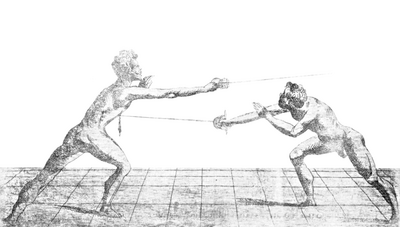

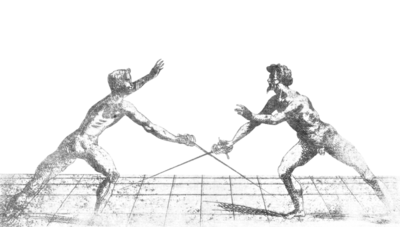

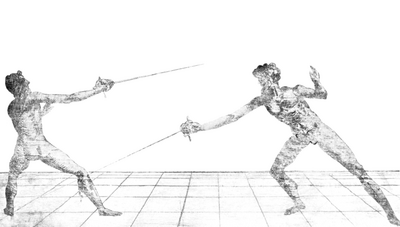

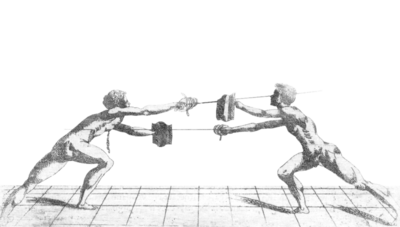

| <p>[18] '''The Method of Proceeding against all Guards and Wounding in Many Ways While the Enemy Disengages the Sword'''</p> | | <p>[18] '''The Method of Proceeding against all Guards and Wounding in Many Ways While the Enemy Disengages the Sword'''</p> | ||

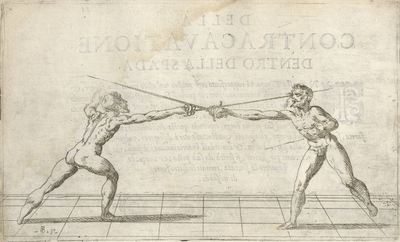

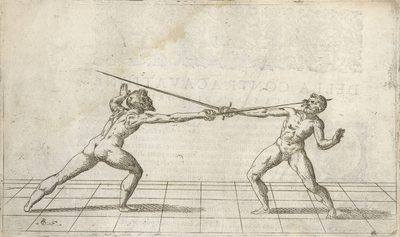

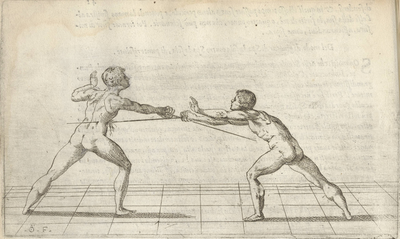

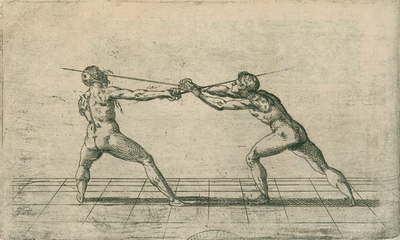

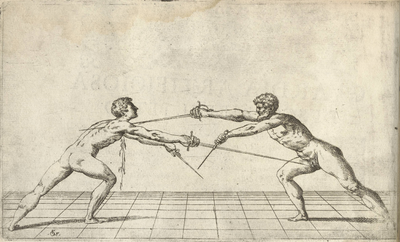

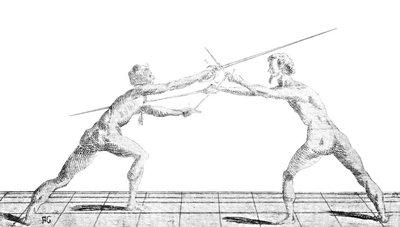

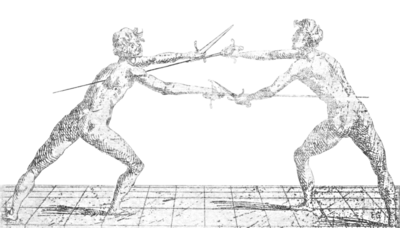

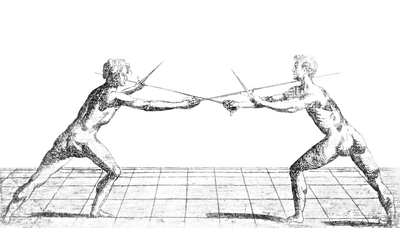

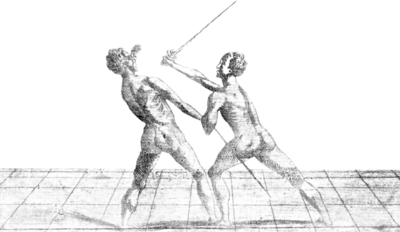

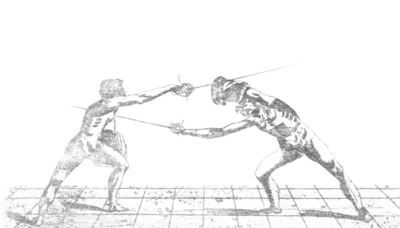

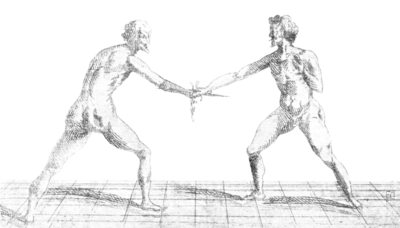

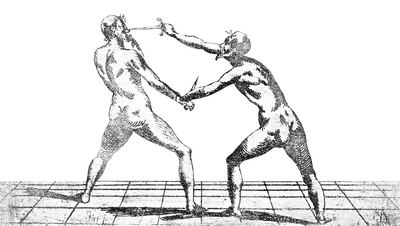

| − | <p>In these four figures I want to show you how one proceeds against every kind of guard. Two figures show you how one binds, the others how one wounds, because a valiant man who is a good and practised fencer will never endanger himself, but will be alert to what the enemy does and see to binding him against his guard. Advancing against the guards is done in this way: Finding the adversary in whatever guard he wishes, high or low or with the sword extended, cover the enemy’s sword with yours but in a way that he cannot wound if he does not disengage the sword, like you see with the two figures. After you have gone to cover the sword so that he cannot offend you if he does not disengage you are safe from every offence, since in disengaging it he can end up wounded in many manners, as you will learn. Finding your enemy with his sword forward, go to bind him with your sword on his like you see in the first figure. If your enemy were to disengage the sword in order to wound you, turn your wrist and parry strongly with your arm extended until the adversary’s sword is on the ground, as you see in the figure. In the same tempo, pass with the foot, place the dagger on the enemy’s sword and, throwing two or three stoccate at him, escape in the above way, securing yourself with your sword on his. This manner of wounding is performed when the enemy is in guard with the sword forward: Go to bind him with your sword on his, and if you see that he does not wish to disengage his sword and stays firm in guard, then disengage yours narrowly, parrying strongly with your arm, and pass with your left foot until the enemy’s sword is on the ground. Then you can place your dagger on his sword, throw some stoccate, and escape in the described way. Many things can be done when proceeding to bind your enemy in the way of the first two figures. If your enemy disengages the sword yet stays still in guard, go to bind him gently and when you are at measure throw with a firm foot where he is most uncovered and escape. You can pass with artifices you have learned. You can also do this: As you advance to bind your enemy, if the adversary disengages the sword in order to wound your face when you are at measure, parry in the same tempo with the dagger and, passing with the foot, throw your ''stoccata'' at his chest, keeping in mind that you must perform all three of these things in one same tempo—that is, while your enemy throws the thrust at your face, you must parry with the dagger, pass with the foot, and throw the ''stoccata''. Otherwise, the pass would not succeed. After, withdraw the ''vita'', throw two or three stoccate, and escape in the above way.</p> | + | <p>In these four figures I want to show you how one proceeds against every kind of guard. Two figures show you how one binds, the others how one wounds, because a valiant man who is a good and practised fencer will never endanger himself, but will be alert to what the enemy does and see to binding him against his guard. Advancing against the guards is done in this way: Finding the adversary in whatever guard he wishes, high or low or with the sword extended, cover the enemy’s sword with yours but in a way that he cannot wound if he does not disengage the sword, like you see with the two figures. After you have gone to cover the sword so that he cannot offend you if he does not disengage you are safe from every offence, since in disengaging it he can end up wounded in many manners, as you will learn. Finding your enemy with his sword forward, go to bind him with your sword on his like you see in the first figure. If your enemy were to disengage the sword in order to wound you, turn your wrist and parry strongly with your arm extended until the adversary’s sword is on the ground, as you see in the figure. In the same tempo, pass with the foot, place the dagger on the enemy’s sword and, throwing two or three ''stoccate'' at him, escape in the above way, securing yourself with your sword on his. This manner of wounding is performed when the enemy is in guard with the sword forward: Go to bind him with your sword on his, and if you see that he does not wish to disengage his sword and stays firm in guard, then disengage yours narrowly, parrying strongly with your arm, and pass with your left foot until the enemy’s sword is on the ground. Then you can place your dagger on his sword, throw some ''stoccate'', and escape in the described way. Many things can be done when proceeding to bind your enemy in the way of the first two figures. If your enemy disengages the sword yet stays still in guard, go to bind him gently and when you are at measure throw with a firm foot where he is most uncovered and escape. You can pass with artifices you have learned. You can also do this: As you advance to bind your enemy, if the adversary disengages the sword in order to wound your face when you are at measure, parry in the same tempo with the dagger and, passing with the foot, throw your ''stoccata'' at his chest, keeping in mind that you must perform all three of these things in one same tempo—that is, while your enemy throws the thrust at your face, you must parry with the dagger, pass with the foot, and throw the ''stoccata''. Otherwise, the pass would not succeed. After, withdraw the ''vita'', throw two or three ''stoccate'', and escape in the above way.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|45|lbl=42|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|46|lbl=43|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|45|lbl=42|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|46|lbl=43|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,408: | Line 1,406: | ||

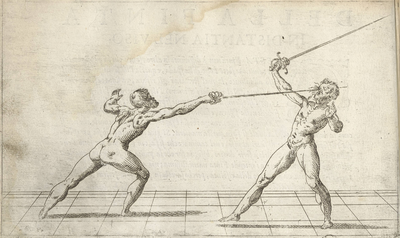

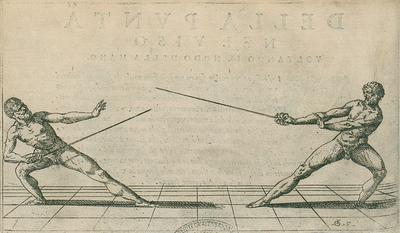

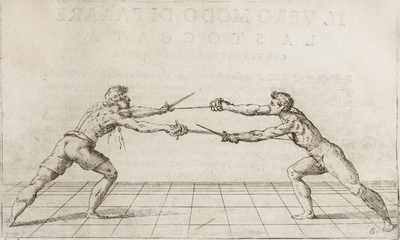

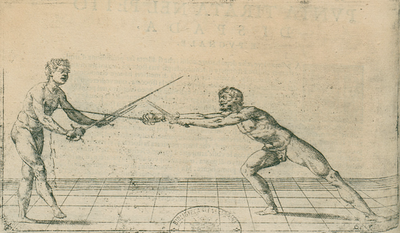

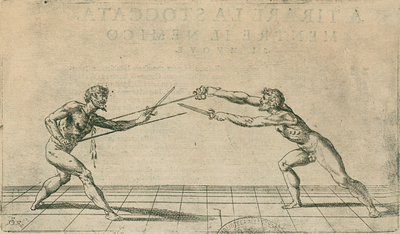

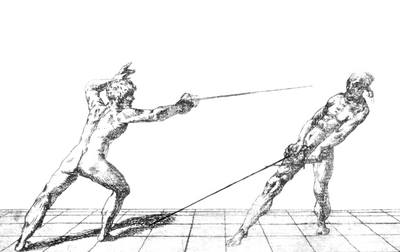

| <p>[19] '''The Method of Throwing the ''Punta Riversa'' at the Face'''</p> | | <p>[19] '''The Method of Throwing the ''Punta Riversa'' at the Face'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This is another kind of wound called a “''punta''”, which is performed in many ways. I will speak to you about this artifice alone. If your enemy were found in guard with the right foot forward and is desirous to wound you, also place yourself with your right foot forward and uncover your chest in order to give him an opportunity to throw at you. Hold the point of your sword toward his left flank so that the enemy guards against your sword with his dagger, and as the adversary throws the ''stoccata'', parry with the dagger and pass with your left foot, throwing the ''stoccata'' on the outside of his sword at his face as you see the figure. This manner of wounding greatly deceives the enemy because, holding the sword toward his left side, he will watch to parry it with the dagger, imagining that when you have parried you will throw the straight ''stoccata'' like he threw his. Whence, he is surprised to find the sword in his face. Having thrown the ''stoccata'', disengage the sword, withdraw your ''vita'', place your dagger on his sword, throw some stoccate, and escape in the above way.</p> | + | <p>This is another kind of wound called a “''punta''”, which is performed in many ways. I will speak to you about this artifice alone. If your enemy were found in guard with the right foot forward and is desirous to wound you, also place yourself with your right foot forward and uncover your chest in order to give him an opportunity to throw at you. Hold the point of your sword toward his left flank so that the enemy guards against your sword with his dagger, and as the adversary throws the ''stoccata'', parry with the dagger and pass with your left foot, throwing the ''stoccata'' on the outside of his sword at his face as you see the figure. This manner of wounding greatly deceives the enemy because, holding the sword toward his left side, he will watch to parry it with the dagger, imagining that when you have parried you will throw the straight ''stoccata'' like he threw his. Whence, he is surprised to find the sword in his face. Having thrown the ''stoccata'', disengage the sword, withdraw your ''vita'', place your dagger on his sword, throw some ''stoccate'', and escape in the above way.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|48|lbl=45}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|48|lbl=45}} | ||

| Line 1,417: | Line 1,415: | ||

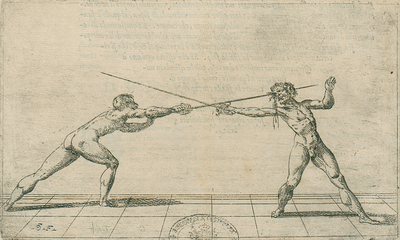

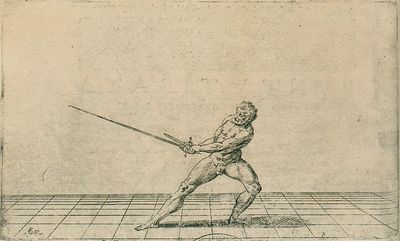

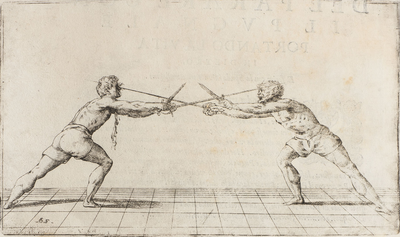

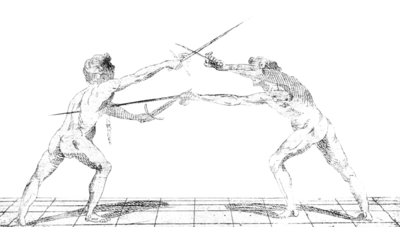

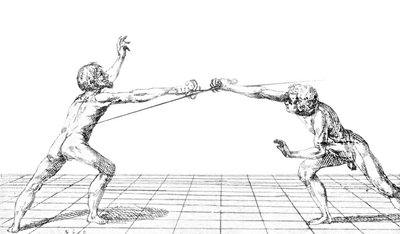

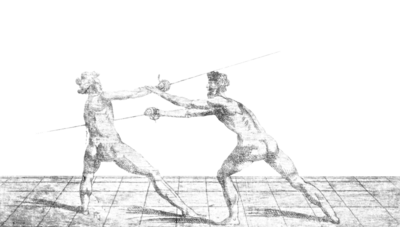

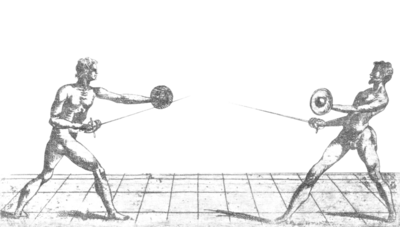

| <p>[20] '''Artificial Guard for Defending Against Furious Passes of the Left or Right Foot'''</p> | | <p>[20] '''Artificial Guard for Defending Against Furious Passes of the Left or Right Foot'''</p> | ||

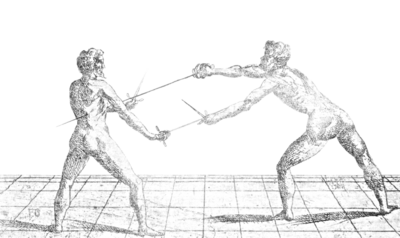

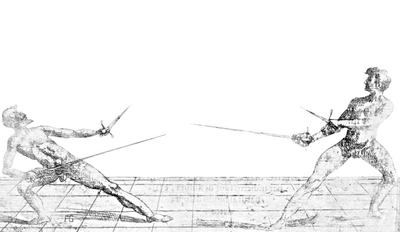

| − | <p>After you have learned to perform all kinds of passes it is necessary to learn how they must be defended against. If by chance someone knew fencing as well as or better than you and was stronger and more dexterous, it would be necessary to make use of the arts of deception, for the reason that it is not enough to know how to throw a graceful thrust, a feint, or a pass, but one must also make use of trickeries and deceptions, and to know from those how to be watchful in occasions, because the flower of this science boils down to trickery and deception. I will demonstrate that such is true thus: If two masters play, they do not make use of either thrusts or cuts, but of the usefulness of new trickeries and deceptions. These figures show you that if your enemy were with his left foot forward due to wishing to pass onto you, when he approaches binding you, place yourself in a guard with the right foot forward, artfully uncover your chest, and give him an opportunity to throw at your chest as you see with the first figures. Be careful that you do not let him come inside measure, and when you see that your enemy wishes to pass, parry with your dagger in the same tempo and bring back your right foot, ending up with your left foot forward as the second figure shows you. The enemy having passed and become similarly disconcerted, having parried his ''stoccata'' you will find it easy to give him as many stoccate as you wish. Give him the first thrust while he passes, parrying in the same tempo, bringing your ''vita'' and step backward and wounding. Then you can immediately disengage the sword again and, when you have thrown the stoccate you wish, return backward outside of measure and escape in the way mentioned above.</p> | + | <p>After you have learned to perform all kinds of passes it is necessary to learn how they must be defended against. If by chance someone knew fencing as well as or better than you and was stronger and more dexterous, it would be necessary to make use of the arts of deception, for the reason that it is not enough to know how to throw a graceful thrust, a feint, or a pass, but one must also make use of trickeries and deceptions, and to know from those how to be watchful in occasions, because the flower of this science boils down to trickery and deception. I will demonstrate that such is true thus: If two masters play, they do not make use of either thrusts or cuts, but of the usefulness of new trickeries and deceptions. These figures show you that if your enemy were with his left foot forward due to wishing to pass onto you, when he approaches binding you, place yourself in a guard with the right foot forward, artfully uncover your chest, and give him an opportunity to throw at your chest as you see with the first figures. Be careful that you do not let him come inside measure, and when you see that your enemy wishes to pass, parry with your dagger in the same tempo and bring back your right foot, ending up with your left foot forward as the second figure shows you. The enemy having passed and become similarly disconcerted, having parried his ''stoccata'' you will find it easy to give him as many ''stoccate'' as you wish. Give him the first thrust while he passes, parrying in the same tempo, bringing your ''vita'' and step backward and wounding. Then you can immediately disengage the sword again and, when you have thrown the ''stoccate'' you wish, return backward outside of measure and escape in the way mentioned above.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|51|lbl=48|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|52|lbl=49|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|51|lbl=48|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|52|lbl=49|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,428: | Line 1,426: | ||

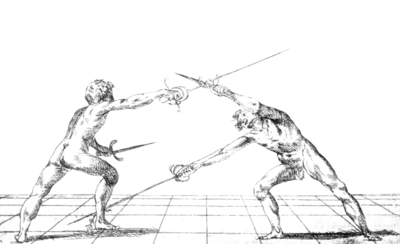

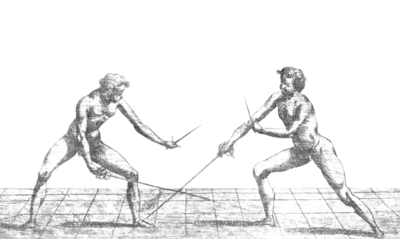

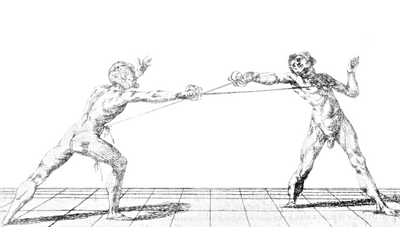

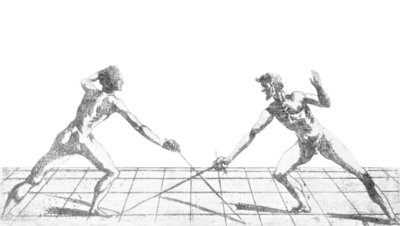

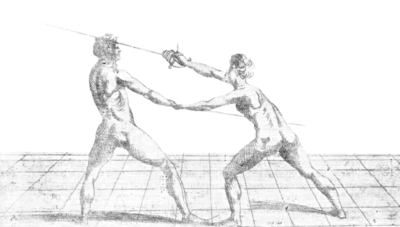

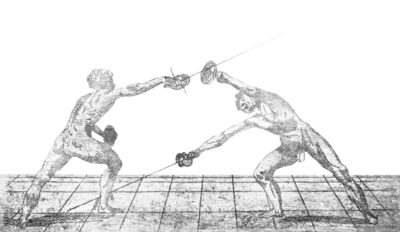

| <p>[21] '''Another Method of Artificial Guards for Deceiving the Enemy''' When He Wishes to Pass with his Right or Left Foot</p> | | <p>[21] '''Another Method of Artificial Guards for Deceiving the Enemy''' When He Wishes to Pass with his Right or Left Foot</p> | ||

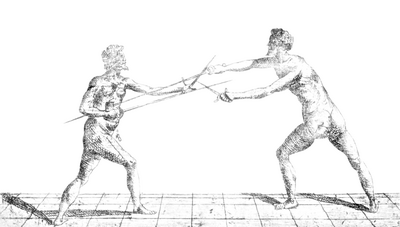

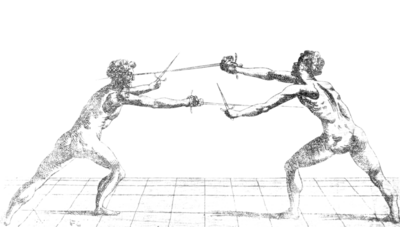

| − | <p>These figures are another way of deceiving the enemy when he wishes to pass onto you with either the right or left foot because even though these figures are seen with the left foot forward, they can nevertheless be defended against in the same way as the passes with the right foot forward. If you see your enemy wishes to come upon you with their left or right foot forward, place yourself in guard with the right foot forward, uncover your chest, and give him an opportunity to move to wound you. In that instant, in the same tempo he throws the ''stoccata'', parry with the sword, bring your foot and ''vita'' back, and wound like the figure. Immediately place your dagger on your enemy’s sword, throw the stoccate you wish, and return backward outside of measure and escape in the way repeatedly described.</p> | + | <p>These figures are another way of deceiving the enemy when he wishes to pass onto you with either the right or left foot because even though these figures are seen with the left foot forward, they can nevertheless be defended against in the same way as the passes with the right foot forward. If you see your enemy wishes to come upon you with their left or right foot forward, place yourself in guard with the right foot forward, uncover your chest, and give him an opportunity to move to wound you. In that instant, in the same tempo he throws the ''stoccata'', parry with the sword, bring your foot and ''vita'' back, and wound like the figure. Immediately place your dagger on your enemy’s sword, throw the ''stoccate'' you wish, and return backward outside of measure and escape in the way repeatedly described.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|55|lbl=52|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|56|lbl=53|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|55|lbl=52|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|56|lbl=53|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,463: | Line 1,461: | ||

| <p>[24] '''The Proper Method of Defending from the ''Inquartata'' With the Void of the ''Vita'''''</p> | | <p>[24] '''The Proper Method of Defending from the ''Inquartata'' With the Void of the ''Vita'''''</p> | ||

| − | <p>Everyone who desires to become perfect in this profession, in addition to knowing how to carry the ''vita'' well, parry well, and control the the sword, also needs to know how to void stoccate with the ''vita'' because it is not always possible to parry with the sword, and in case of necessity, recognizing the danger, one must void the ''vita''. I want to teach you two ways to defend from stoccate by voiding the ''vita'' and wounding the enemy. It is done in this way: Go to bind your enemy on the outside with your sword over his, stand with your ''vita'' straight, and give him occasion to wound you by ''inquartata''. In the tempo that he disengages his sword to wound you, quickly lower your ''vita'' so that his ''stoccata'' will miss and in the same tempo disengage the sword under the enemy’s sword hand so that you wound him in the flank, as you see the figure. Immediately place your left hand on the hilt of the enemy’s sword and disengage your sword so that you can wound with two or three stoccate and return immediately outside of measure, as usual.</p> | + | <p>Everyone who desires to become perfect in this profession, in addition to knowing how to carry the ''vita'' well, parry well, and control the the sword, also needs to know how to void ''stoccate'' with the ''vita'' because it is not always possible to parry with the sword, and in case of necessity, recognizing the danger, one must void the ''vita''. I want to teach you two ways to defend from ''stoccate'' by voiding the ''vita'' and wounding the enemy. It is done in this way: Go to bind your enemy on the outside with your sword over his, stand with your ''vita'' straight, and give him occasion to wound you by ''inquartata''. In the tempo that he disengages his sword to wound you, quickly lower your ''vita'' so that his ''stoccata'' will miss and in the same tempo disengage the sword under the enemy’s sword hand so that you wound him in the flank, as you see the figure. Immediately place your left hand on the hilt of the enemy’s sword and disengage your sword so that you can wound with two or three ''stoccate'' and return immediately outside of measure, as usual.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|62|lbl=59}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|62|lbl=59}} | ||

| Line 1,494: | Line 1,492: | ||

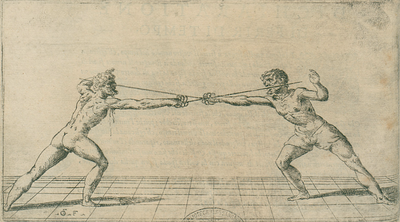

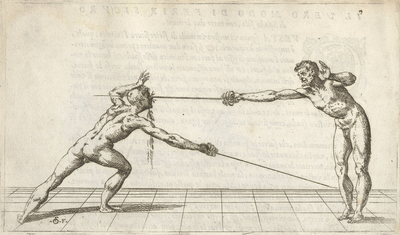

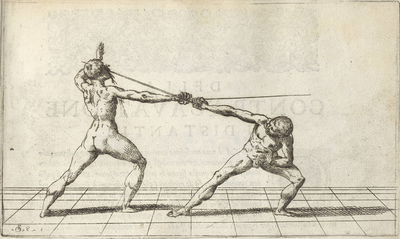

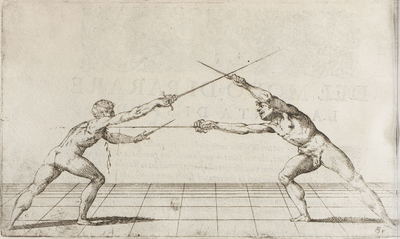

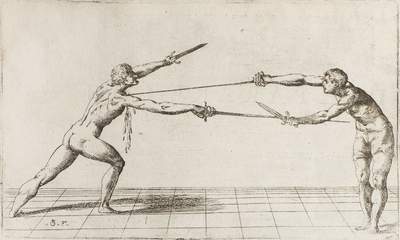

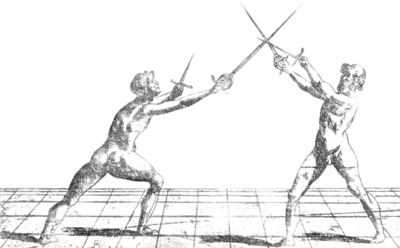

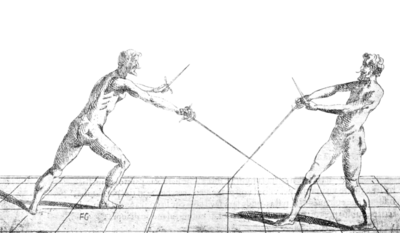

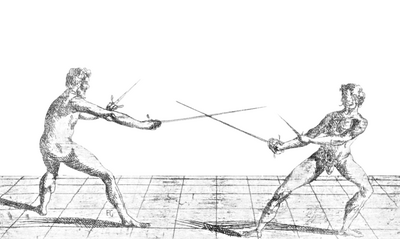

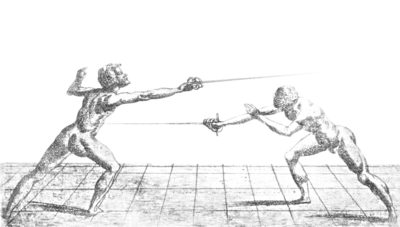

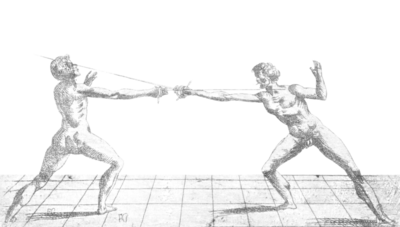

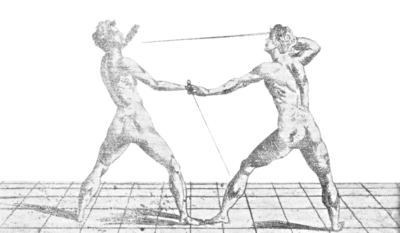

| <p>[28] '''The Method of Defending from the Pass of the Left Foot at a Distance''' with the Counterdisengage</p> | | <p>[28] '''The Method of Defending from the Pass of the Left Foot at a Distance''' with the Counterdisengage</p> | ||

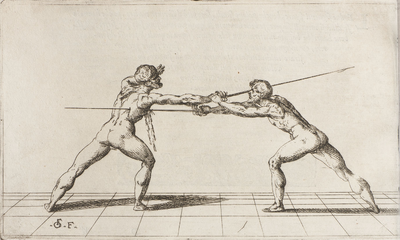

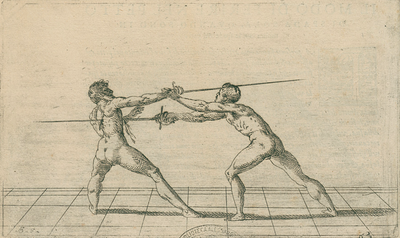

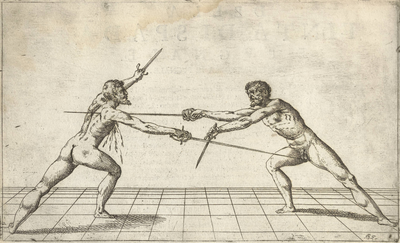

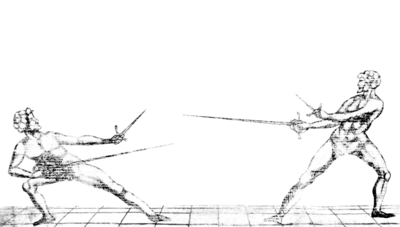

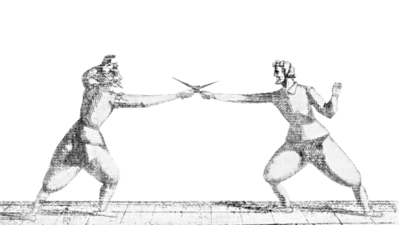

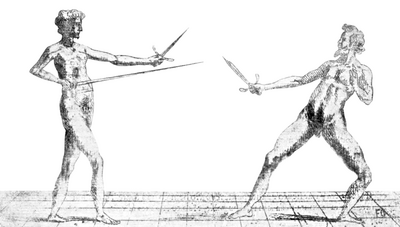

| − | <p>These figures that you see, one with his left foot forward in order to pass, the other with his right foot forward in order to defend and wound, are very useful, as you will learn. If the enemy were to place himself with his left foot forward in order to wound you and comes to bind you in order to seize the tempo to pass, place yourself in guard with your right foot forward and your sword forward, uncover your right shoulder, and give him a tempo so that he passes because he thinks that you will parry with the edge of your sword and trusts the quickness of throwing a ''stoccata''—that is, that his stoccate will arrive before you have time to parry. He will succeed every time he is at or inside measure, hence be careful not to let him come inside measure, and when you see he wishes to pass, in the same tempo disengage your sword under his hilt and withdraw the ''vita'' slightly, accompanied by the sword, so that you parry and wound in the same tempo as you see the figure has, and immediately return backward outside of measure with your sword over his.</p> | + | <p>These figures that you see, one with his left foot forward in order to pass, the other with his right foot forward in order to defend and wound, are very useful, as you will learn. If the enemy were to place himself with his left foot forward in order to wound you and comes to bind you in order to seize the tempo to pass, place yourself in guard with your right foot forward and your sword forward, uncover your right shoulder, and give him a tempo so that he passes because he thinks that you will parry with the edge of your sword and trusts the quickness of throwing a ''stoccata''—that is, that his ''stoccate'' will arrive before you have time to parry. He will succeed every time he is at or inside measure, hence be careful not to let him come inside measure, and when you see he wishes to pass, in the same tempo disengage your sword under his hilt and withdraw the ''vita'' slightly, accompanied by the sword, so that you parry and wound in the same tempo as you see the figure has, and immediately return backward outside of measure with your sword over his.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|71|lbl=68|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|72|lbl=69|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|71|lbl=68|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|72|lbl=69|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,516: | Line 1,514: | ||

| <p>[31] '''A Method of Coming to Grips''' and Giving a Cut to the Head</p> | | <p>[31] '''A Method of Coming to Grips''' and Giving a Cut to the Head</p> | ||

| − | <p>This grip you see is similar to the previous as far as passing, because this is also done with the same pass. After you have passed, then, and you are both with your swords equal, place your left hand on the furnishings of the enemy’s sword, pressing his sword arm with your hand as the present figure shows you, and in the same tempo strike him with a cut to the head that he will doubtless be unable to parry. Give two or three cuts, withdrawing your ''vita'', holding the enemy’s arm in place with your hand. You can give two or three stoccate and then return backward outside of measure in the above way. Performing these grips consists in knowing well how to seize the tempo to pass safely. It can be seized in many ways, such as uncovering the right side, giving the enemy an opportunity to throw a thrust, and immediately parrying with the ''forte'' of the sword, passing with the foot, straightening the point of the sword at the enemy’s face which, if he does not parry it, will land a thrust on his face and thus nothing further is done. Even if he parries it, though, you will be with your swords equal, and you will come to grips so that the furnishings of your sword make contact with his. Then you will be able to perform all four kinds of grips that I placed in this book. You can also go to bind your enemy on the outside of his sword and pass with the foot, seizing the tempo in the said way, since as long as you have your swords equal you perform one of these four grips—whichever most pleases you. You can also pass safely in this other manner: Go to bind your enemy on the inside with your sword over his and give him occasion to disengage in order to wound you. Then, while he disengages the sword, parry the enemy’s sword with the ''forte'' of your weapons and pass with the foot. Thus, if he does not defend from it, you strike him in the face, and, if he parries, you will be with your weapons equal. Given that, therefore, I said performing these grips consists in knowing how to choose the tempo to pass safely.</p> | + | <p>This grip you see is similar to the previous as far as passing, because this is also done with the same pass. After you have passed, then, and you are both with your swords equal, place your left hand on the furnishings of the enemy’s sword, pressing his sword arm with your hand as the present figure shows you, and in the same tempo strike him with a cut to the head that he will doubtless be unable to parry. Give two or three cuts, withdrawing your ''vita'', holding the enemy’s arm in place with your hand. You can give two or three ''stoccate'' and then return backward outside of measure in the above way. Performing these grips consists in knowing well how to seize the tempo to pass safely. It can be seized in many ways, such as uncovering the right side, giving the enemy an opportunity to throw a thrust, and immediately parrying with the ''forte'' of the sword, passing with the foot, straightening the point of the sword at the enemy’s face which, if he does not parry it, will land a thrust on his face and thus nothing further is done. Even if he parries it, though, you will be with your swords equal, and you will come to grips so that the furnishings of your sword make contact with his. Then you will be able to perform all four kinds of grips that I placed in this book. You can also go to bind your enemy on the outside of his sword and pass with the foot, seizing the tempo in the said way, since as long as you have your swords equal you perform one of these four grips—whichever most pleases you. You can also pass safely in this other manner: Go to bind your enemy on the inside with your sword over his and give him occasion to disengage in order to wound you. Then, while he disengages the sword, parry the enemy’s sword with the ''forte'' of your weapons and pass with the foot. Thus, if he does not defend from it, you strike him in the face, and, if he parries, you will be with your weapons equal. Given that, therefore, I said performing these grips consists in knowing how to choose the tempo to pass safely.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|78|lbl=75}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|78|lbl=75}} | ||

| Line 1,567: | Line 1,565: | ||

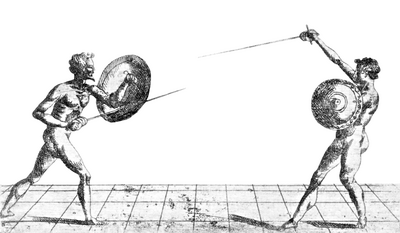

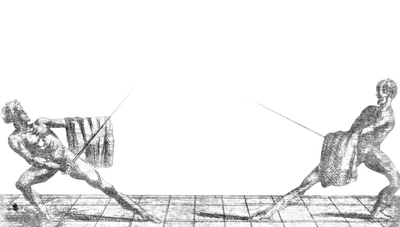

| <p>[36] '''The Proper Method of Holding the Rotella'''</p> | | <p>[36] '''The Proper Method of Holding the Rotella'''</p> | ||

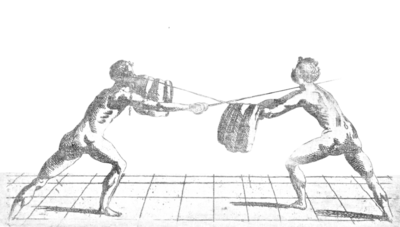

| − | <p>These four figures show you how the rotella must be held in the hand. The first two teach how one must stand in guard, and the other two show how one must defend and wound. The rotella is held with the fist upward, as you see in the figure, so that it burdens you less and so that you can more easily defend from all kinds of blows, either thrust or cut. If you were to hold the rotella with the arm extended, as many believe it must be held, you would tire your arm and be endangered. The rotella has wonderful characteristics for someone who knows how to hold it in hand and who is practised because, due to the great size of the rotella, it is easy to defend from both ''mandritto'' and ''riverso'' cuts with it. Every ''stoccata'' that touches it even slightly is defended from and, defended, it is then easy to wound. The ''mandritto'' is defended from with the surface of the rotella, the ''riverso'' with its edge, and the imbroccata with its surface. Other thrusts are defended against with its edge. As soon as one has defended, it is necessary to return to having the fist upward so that, while you defend on either the outside or inside, you partially watch your enemy to observe what he wishes to do. If you were to hold the rotella forward in parrying, you would be in danger because you would not see what your enemy is able to do. Stoccate that come underneath the rotella at the flank are parried with the sword, and then one wounds. I have produced these four figures: One stands in high guard and the other in low guard. The other two are he who is in high guard throwing imbroccata, the other who defends with the rotella and wounds in the same tempo, as described with the sword and dagger. The rotella is good at night when assaulted by more than one.</p> | + | <p>These four figures show you how the rotella must be held in the hand. The first two teach how one must stand in guard, and the other two show how one must defend and wound. The rotella is held with the fist upward, as you see in the figure, so that it burdens you less and so that you can more easily defend from all kinds of blows, either thrust or cut. If you were to hold the rotella with the arm extended, as many believe it must be held, you would tire your arm and be endangered. The rotella has wonderful characteristics for someone who knows how to hold it in hand and who is practised because, due to the great size of the rotella, it is easy to defend from both ''mandritto'' and ''riverso'' cuts with it. Every ''stoccata'' that touches it even slightly is defended from and, defended, it is then easy to wound. The ''mandritto'' is defended from with the surface of the rotella, the ''riverso'' with its edge, and the ''imbroccata'' with its surface. Other thrusts are defended against with its edge. As soon as one has defended, it is necessary to return to having the fist upward so that, while you defend on either the outside or inside, you partially watch your enemy to observe what he wishes to do. If you were to hold the rotella forward in parrying, you would be in danger because you would not see what your enemy is able to do. ''Stoccate'' that come underneath the rotella at the flank are parried with the sword, and then one wounds. I have produced these four figures: One stands in high guard and the other in low guard. The other two are he who is in high guard throwing ''imbroccata'', the other who defends with the rotella and wounds in the same tempo, as described with the sword and dagger. The rotella is good at night when assaulted by more than one.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|87|lbl=84|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|88|lbl=85|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|87|lbl=84|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|88|lbl=85|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,578: | Line 1,576: | ||

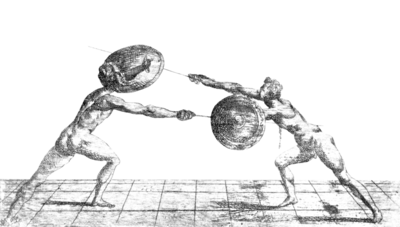

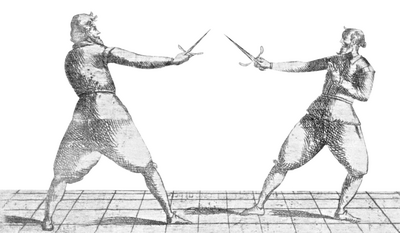

| <p>[37] '''The Proper Method of Holding the Targa'''</p> | | <p>[37] '''The Proper Method of Holding the Targa'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>The targa is an arm for defending which came from the Greeks, who still use it. Now it is in much use not only in Venice but in many cities in Lombardy, and it is quite useful in contentions because it easily defends from all ''mandritti'' and ''riversi''. Defending with the targa is little different from defending with the dagger because thrusts are defended with the edge of the targa which, due to having four sides, finds the enemies thrusts easily, and as soon as the sword is touched at all with the targa, they are defended. The targa is held in the way you see these first figures do. The ''mandritto'' and imbroccata are parried with the surface of the targa, and the stoccate that come on the inside or outside are parried with the edge, turning the targa as the dagger is. With the targa you can produce all guards and artifices that you learned to perform with the sword and dagger, but you must be experienced. These are four figures: Two in guard who teach you how the targa is held, while the other two show you how one parries and wounds. It may be positioned in many ways in parrying and wounding, but, as I said, those that you learned to do in sword and dagger can by done with sword and targa, although it is necessary to practise it.</p> | + | <p>The targa is an arm for defending which came from the Greeks, who still use it. Now it is in much use not only in Venice but in many cities in Lombardy, and it is quite useful in contentions because it easily defends from all ''mandritti'' and ''riversi''. Defending with the targa is little different from defending with the dagger because thrusts are defended with the edge of the targa which, due to having four sides, finds the enemies thrusts easily, and as soon as the sword is touched at all with the targa, they are defended. The targa is held in the way you see these first figures do. The ''mandritto'' and ''imbroccata'' are parried with the surface of the targa, and the ''stoccate'' that come on the inside or outside are parried with the edge, turning the targa as the dagger is. With the targa you can produce all guards and artifices that you learned to perform with the sword and dagger, but you must be experienced. These are four figures: Two in guard who teach you how the targa is held, while the other two show you how one parries and wounds. It may be positioned in many ways in parrying and wounding, but, as I said, those that you learned to do in sword and dagger can by done with sword and targa, although it is necessary to practise it.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|91|lbl=88|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|92|lbl=89|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|91|lbl=88|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|92|lbl=89|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,600: | Line 1,598: | ||

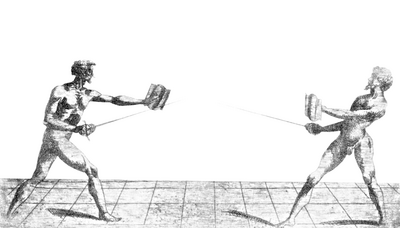

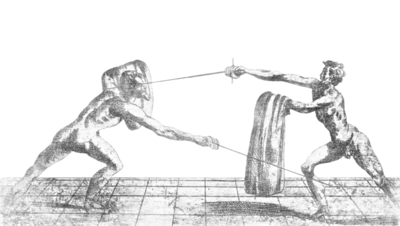

| <p>[39] '''Method of Holding the Cape, and the Method of Wounding'''</p> | | <p>[39] '''Method of Holding the Cape, and the Method of Wounding'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>To contend safely using sword and cape, first it is necessary to know how to play with the single sword, being that all cuts, and likewise all stoccate, are parried with the sword. Additionally, it is very useful to know how the cape must be held and what qualities it has, because there are many countries in which it is not permitted to carry the dagger and, therefore, everyone takes up the cape for defence. In occasions some are even found who, despite having the dagger at their side, by natural inclination deem it much better to take up the cape when suddenly attacked, and let the dagger be. There are many ways of holding the cape, just as there are men of many different temperaments. For brevity, in this Second Book I will teach you only two manners, being that it would produce two books if I wished to say all that can be said on this subject. From these two figures intelligent people will be able to learn many other manners. Firstly, to be well-made, the cape must be of cloth, given that if you had a cape of silk, you would receive harm in exchange for usefulness because you would not be able to defend against a cut at your head or legs as it approaches. Hence, I deem it better to make use of the single sword than the sword and silk cape. It should be of cloth, therefore. When you are attacked by the enemy, unfurl the cape with your left hand on the edge of the collar, let it fall over the arm to the elbow, and turn it once over the arm, as you see the two figures have, one with the right foot forward, the other with the left foot forward. After you have taken up the cape, it is necessary to position yourself forward with the sword rested on the cape as you see the figures do. In these guards you can defend against all types of blows that a man can throw. Being in a guard like you see, with the sword forward and either the right or left foot forward, if your enemy were to throw a thrust or imbroccata at you, go to parry with the sword, resting the cape hand on the sword so that you have greater strength in parrying the enemy’s ''stoccata'', then wound from a firm foot or with a pass, as you deem most convenient. When you have wounded, return backward outside of measure and escape, securing yourself with your sword of that of the enemy in the way mentioned above. If your enemy were to throw a cut at your head, you can defend in this way: While he throws the cut, go to parry with the sword, accompanied and fortified by the cape arm, so that you thus cause the enemy’s sword to fall, as you see in the figure. The blow thrown, return backward outside of measure in the above way. Being in a guard as you see, your cape draped down, your enemy throwing a cut at your leg, you can go to parry it with the cape and throw a thrust at his face, as I will describe below.</p> | + | <p>To contend safely using sword and cape, first it is necessary to know how to play with the single sword, being that all cuts, and likewise all ''stoccate'', are parried with the sword. Additionally, it is very useful to know how the cape must be held and what qualities it has, because there are many countries in which it is not permitted to carry the dagger and, therefore, everyone takes up the cape for defence. In occasions some are even found who, despite having the dagger at their side, by natural inclination deem it much better to take up the cape when suddenly attacked, and let the dagger be. There are many ways of holding the cape, just as there are men of many different temperaments. For brevity, in this Second Book I will teach you only two manners, being that it would produce two books if I wished to say all that can be said on this subject. From these two figures intelligent people will be able to learn many other manners. Firstly, to be well-made, the cape must be of cloth, given that if you had a cape of silk, you would receive harm in exchange for usefulness because you would not be able to defend against a cut at your head or legs as it approaches. Hence, I deem it better to make use of the single sword than the sword and silk cape. It should be of cloth, therefore. When you are attacked by the enemy, unfurl the cape with your left hand on the edge of the collar, let it fall over the arm to the elbow, and turn it once over the arm, as you see the two figures have, one with the right foot forward, the other with the left foot forward. After you have taken up the cape, it is necessary to position yourself forward with the sword rested on the cape as you see the figures do. In these guards you can defend against all types of blows that a man can throw. Being in a guard like you see, with the sword forward and either the right or left foot forward, if your enemy were to throw a thrust or ''imbroccata'' at you, go to parry with the sword, resting the cape hand on the sword so that you have greater strength in parrying the enemy’s ''stoccata'', then wound from a firm foot or with a pass, as you deem most convenient. When you have wounded, return backward outside of measure and escape, securing yourself with your sword of that of the enemy in the way mentioned above. If your enemy were to throw a cut at your head, you can defend in this way: While he throws the cut, go to parry with the sword, accompanied and fortified by the cape arm, so that you thus cause the enemy’s sword to fall, as you see in the figure. The blow thrown, return backward outside of measure in the above way. Being in a guard as you see, your cape draped down, your enemy throwing a cut at your leg, you can go to parry it with the cape and throw a thrust at his face, as I will describe below.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|99|lbl=96|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|100|lbl=97|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|99|lbl=96|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|100|lbl=97|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,608: | Line 1,606: | ||

| <p>[40] '''Another Method of Holding the Cape, Turning it Twice Around the Arm'''</p> | | <p>[40] '''Another Method of Holding the Cape, Turning it Twice Around the Arm'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This is another way of holding the cape. It is seized in the same way as above and wrapped twice around the arm so that it can withstand the strikes of cuts. Because most people do not know how to play at arms, they throw many cuts. Therefore, this way of holding the cape is quite necessary. With it, it is possible to wound safely as you see the figure has, who has parried the cut and in the same tempo throws a thrust. Parrying the cut, you can do many things, like throw a ''mandritto'' at him, or a ''riverso'' at his leg, or, in short, everything you will have learned to do with the sword and dagger. The cuts toward the leg are defended against in the way described with the sword and dagger and the stoccate are parried with the sword, as the imbroccate also are. One wounds with cut or thrust, as appears most appropriate.</p> | + | <p>This is another way of holding the cape. It is seized in the same way as above and wrapped twice around the arm so that it can withstand the strikes of cuts. Because most people do not know how to play at arms, they throw many cuts. Therefore, this way of holding the cape is quite necessary. With it, it is possible to wound safely as you see the figure has, who has parried the cut and in the same tempo throws a thrust. Parrying the cut, you can do many things, like throw a ''mandritto'' at him, or a ''riverso'' at his leg, or, in short, everything you will have learned to do with the sword and dagger. The cuts toward the leg are defended against in the way described with the sword and dagger and the ''stoccate'' are parried with the sword, as the ''imbroccate'' also are. One wounds with cut or thrust, as appears most appropriate.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|102|lbl=99}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|102|lbl=99}} | ||

| Line 1,615: | Line 1,613: | ||

| <p>[41] '''The Method of Defending Against [Cuts] to the Leg with the Cape'''</p> | | <p>[41] '''The Method of Defending Against [Cuts] to the Leg with the Cape'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This is the third manner of holding the cape that I promised to teach you, and in this way it is possible to defend against cuts toward the leg. The cape is seized by the collar and held suspended, as you see. If your enemy throws a thrust or cut at your head it is necessary to parry with the sword and wound, as described with the sword and dagger. Fighting with your enemy and knowing how to play with the single sword well, you will be able to do this: Parry stoccate and cuts with the sword and, while you parry, throw the cape at the adversary’s weapons or face so that you will obstruct it a way that it will be easy to then strike him where he is most uncovered before the cape has fallen from his weapons. The figure you see is two men desirous to throw at the leg. Hence, fighting with your enemy, when you stand with the sword advanced in order to parry and wound and the enemy throws a cut at your leg, go to meet your enemy’s cut with your cape so that in the same tempo you remove the strength from the and strike him in the face with a thrust, as you see the figure has, because while he throws at your leg it is necessary that he come forward, whence, you throwing at his face, it will be easy for you to wound it. The ''stoccata'' thrown, return backward outside of measure as usual.</p> | + | <p>This is the third manner of holding the cape that I promised to teach you, and in this way it is possible to defend against cuts toward the leg. The cape is seized by the collar and held suspended, as you see. If your enemy throws a thrust or cut at your head it is necessary to parry with the sword and wound, as described with the sword and dagger. Fighting with your enemy and knowing how to play with the single sword well, you will be able to do this: Parry ''stoccate'' and cuts with the sword and, while you parry, throw the cape at the adversary’s weapons or face so that you will obstruct it a way that it will be easy to then strike him where he is most uncovered before the cape has fallen from his weapons. The figure you see is two men desirous to throw at the leg. Hence, fighting with your enemy, when you stand with the sword advanced in order to parry and wound and the enemy throws a cut at your leg, go to meet your enemy’s cut with your cape so that in the same tempo you remove the strength from the and strike him in the face with a thrust, as you see the figure has, because while he throws at your leg it is necessary that he come forward, whence, you throwing at his face, it will be easy for you to wound it. The ''stoccata'' thrown, return backward outside of measure as usual.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|104|lbl=101}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti) 1608.pdf|104|lbl=101}} | ||

| Line 1,666: | Line 1,664: | ||

| <p>[45] '''Method of Defending with the Single Dagger against Sword and Dagger'''</p> | | <p>[45] '''Method of Defending with the Single Dagger against Sword and Dagger'''</p> | ||