|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Nicoletto Giganti"

m (NOW I'm done with this bit.) |

|||

| (30 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox writer | {{Infobox writer | ||

| name = [[name::Nicoletto Giganti]] | | name = [[name::Nicoletto Giganti]] | ||

| − | | image = File:Nicoletto Giganti | + | | image = File:Nicoletto Giganti.png |

| − | | imagesize = | + | | imagesize = 225px |

| caption = | | caption = | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

| below = | | below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

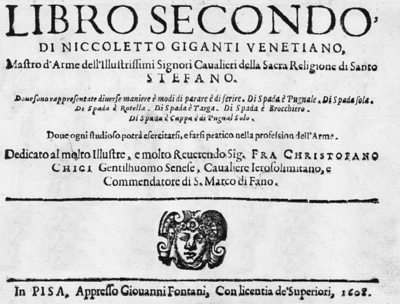

| − | '''Nicoletto Giganti''' (Niccoletto, Nicolat) was an [[nationality::Italian]] soldier and [[fencing master]] around the turn of the [[century::17th century]]. He was likely born to a noble family in Fossombrone in central Italy,<ref name="Terminiello 9"> | + | '''Nicoletto Giganti''' (Niccoletto, Nicolat) was an [[nationality::Italian]] soldier and [[fencing master]] around the turn of the [[century::17th century]]. He was likely born to a noble family in Fossombrone in central Italy,<ref name="Terminiello 9">Giganti 2013, p 9.</ref> and only later became a citizen of Venice.<ref>That he eventually became a Venetian citizen is indicated on the [[Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/5|title page]] of his 1606 treatise.</ref> Little is known of Giganti’s life, but in the dedication to his 1606 treatise he claims 27 years of professional experience, meaning that his career began in 1579 (possibly referring to service in the Venetian military, a long tradition of the Giganti family).<ref name="Terminiello 9"/> Additionally, the preface to his 1608 treatise describes him as a Master of Arms to the Order of Santo Stefano in Pisa, a powerful military order founded by Cosimo I de' Medici, giving some further clues to his career. |

| − | In 1606, Giganti published a treatise on the use of the rapier (both single and with the dagger) titled ''[[Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti)|Scola, overo teatro]]'' ("School or Theater"). It is dedicated to Cosimo II de' Medici. This treatise is structured as a series of progressively more complex lessons, and Tom Leoni opines that this treatise is the best pedagogical work on rapier fencing of the early 17th century.<ref> | + | In 1606, Giganti published a treatise on the use of the rapier (both single and with the dagger) titled ''[[Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti)|Scola, overo teatro]]'' ("School, or Theater"). It is dedicated to Cosimo II de' Medici. This treatise is structured as a series of progressively more complex lessons, and Tom Leoni opines that this treatise is the best pedagogical work on rapier fencing of the early 17th century.<ref>Giganti 2010, p xi.</ref> It is also the first treatise to fully articulate the principle of the lunge. Giganti also promised in this book that he would publish a second volume, a pledge he made good on in 1608.<ref>This treatise was considered lost for centuries, and as early as 1673 the Sicilian master [[Giuseppe Morsicato Pallavicini]] stated that this second book was never published at all. See ''[[La seconda parte della scherma illustrata (Giuseppe Morsicato Pallavicini)|La seconda parte della scherma illustrata]]''. Palermo, 1673. p V.</ref> Titled ''[[Libro secondo (Nicoletto Giganti)|Libro secondo di Niccoletto Giganti]]'' ("Second Book of Niccoletto Giganti"), it is dedicated to Christofano Chigi, a Knight of Malta, and covers the same weapons as the first as well as rapier and buckler, rapier and cloak, rapier and shield, single dagger, and mixed weapon encounters. This text in turn promises additional writings on the dagger and on cutting with the rapier, but there is no record of further books by Giganti ever being published. |

| − | + | While Giganti's second book quickly disappeared from history, his first seems to have been quite popular: reprints, mostly unauthorized, sprang up many times over the subsequent decades, both in the original Italian and, beginning in 1619, in French and German translations. The 1622 edition of this unauthorized dual-language edition also included book 2 of [[Salvator Fabris]]' 1606 treatise ''[[Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Lo Schermo, overo Scienza d'Arme]]''<ref>It's possible that the 1619 did as well, but there are no surviving copies that include it so we have to assume it didn't.</ref> which, coupled with the loss of Giganti's true second book, is probably what has lead many later bibliographers to accuse Giganti himself of plagiarism.<ref>This accusation was first made by [[Johann Joachim Hynitzsch]], who attributed the edition to Giganti rather than Zeter and was incensed that he gave no credit to Fabris.</ref> | |

| − | + | == Treatise == | |

| − | + | Giganti, like many 17th century authors, had a tendency to write incredibly long, multi-page paragraphs which quickly become hard to follow. Jacob de Zeter's 1619 dual-language edition often breaks these up into more manageable chunks, and in this concordance his paragraph breaks have also been applied to the Italian and English. | |

| − | + | A [http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/109AF678 copy of the 1628 printing] of the first book which now resides in the [[Österreichische Nationalbibliothek]] was extensively annotated by a contemporary reader. Its annotations are beyond the scope of this concordance, but they have been [http://www.rapier.at/2018/07/20/a-transcription-of-annotations-in-the-onb-copy-211216-c-of-scola-overo-teatro-by-nicoletto-giganti/ transcribed] by [[Julian Schrattenecker]] and [[Florian Fortner]], and incorporated into [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]'s translation in a [https://labirinto.ca/translations/ separate document]. | |

| − | + | Since scans of the only known copy of Giganti's second book are not available for public use, its illustrations have been redrawn by [[Monika E. B. Stankiewicz]]. | |

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| − | | title = | + | | title = First Book |

| + | | width = 100% | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Dedication | ||

| width = 150em | | width = 150em | ||

}} | }} | ||

{| class="master" | {| class="master" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! <p> | + | ! <p>Illustrations<br/>from the 1606</p> |

! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> | ||

| − | ! <p> | + | ! <p>[[Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti)|First Edition]] (1606){{edit index|Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> |

| − | ! <p>German (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>by [[Jan Schäfer]] | + | ! <p>German Translation (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Jan Schäfer]]</p> |

| − | ! <p>French (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | + | ! <p>French Translation (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| rowspan="4" | [[File:Giganti Title 1606.png|400x400px|center|Title Page]] | | rowspan="4" | [[File:Giganti Title 1606.png|400x400px|center|Title Page]] | ||

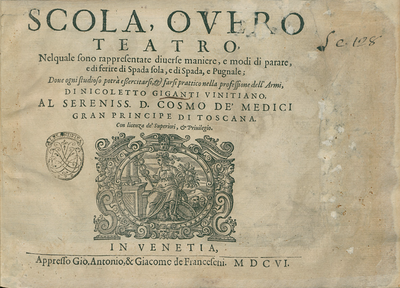

| − | + | | <p>'''School, or Theatre''' In which different manners and methods of parrying and wounding with the single sword and sword and dagger are represented; ''Where every scholar will be able to exercise and become practised in the profession of arms'' | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/5|1|lbl=i}} | |

| − | + | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|1|lbl=-}} | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/3|1|lbl=ii}} | |

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | <p>'''By Nicoletto Giganti, Venetian, To the Most Serene Don Cosimo de’ Medici, Great Prince of Tuscany'</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/5|2|lbl=-}} | |

| − | + | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|2|lbl=-}} | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/3|2|lbl=-}} | |

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|3|lbl=-}} | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/3|3|lbl=-}} | |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | <p>With license and privilege of the Superiors</p> | + | | <p>''With license and privilege of the Superiors''</p> |

| − | <p>'''In Venice'''<br/>Printed by Giovanni Antonio and Giacomo de Frenchesi. MDCVI</p> | + | <p>'''In Venice,'''<br/>Printed by Giovanni Antonio and Giacomo de Frenchesi. MDCVI</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/5|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/5|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| <p><br/></p> | | <p><br/></p> | ||

| Line 110: | Line 114: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti Medici Heraldry.png|400x400px|center|Arms of the Medici Family]] | | [[File:Giganti Medici Heraldry.png|400x400px|center|Arms of the Medici Family]] | ||

| − | | <p>'''To the Most Serene Don Cosimo de Medici Great Prince of Tuscany''' my only Lord</p> | + | | <p>'''To the Most Serene Don Cosimo de Medici, Great Prince of Tuscany,''' my only Lord</p> |

| − | <p>Just as iron extracted from the rough mines would be useless | + | <p>Just as iron extracted from the rough mines would be useless had it not received shape suited to human armies from industrious art, thus the same in the hands of the strong soldier can be of little profit if, accompanied by studious and wise valour, the way is not made clear for every difficult and triumphant success. In this way to a point, since the Good Shepherd welcomes the operation, and because almost all the noblest things proceeding from our actions receive appropriate material from His hands which, refined and dignified by the industry of the spirit, achieve miraculous and powerful effects. I am stunned to silence now that this tempering is wonderfully displayed in the excellence and illustrious greatness of Your Most Serene Highness. You retain the natural greatness returned to its peak from the invincible glorious works of Your ancestors, not only in the ancient and royal histories, but reflecting all the light of the present and past splendour in yourself, adorning them with your own virtues so that everyone admires that most divine temper, and with wonderment says that such a Most Serene Lord is no less fitting to that Most Serene State than such a Most Serene State to that Most Serene Lord. However, I will merely say that just as this proposition is demonstrated clearly in all the arts, so it is perceived evidently in exercising arms. Discussing the strength of steel, even if it is employed by a strong arm and agile body, if it is not conferred with observed rules and exercised study, it is shown to be perilous and of little valour, whereas if the art can be recognized as a wise captain and obeyed as a bold minister, they make marvelous prowess of it. Your testament serves as a clear example to us in which Heaven, needing to grant every level of perfect quality, as in the most complete illumination of the present age, has in the noblest proportion of stature, puissance, and vigour joined agility, promptness, and strength in order to draw with its highest ingenuity the finesse of industry, advice, time, and art that is able to make a Most Complete and Illustrious Captain a Most Serene and Singular Prince.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|7|lbl=iii|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|8|lbl=iv|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/9|1|lbl=v|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|7|lbl=iii|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|8|lbl=iv|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/9|1|lbl=v|p=1}} | ||

| Line 120: | Line 124: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Wherefore I, recognizing and admiring with humblest affection the mature splendour of | + | | <p>Wherefore I, recognizing and admiring with humblest affection the mature splendour of Your young and happy years, and reading in the face of the world the secure hopes and fruits of the future age, adoring that hand from which Italy and the entire world is taking safe rest and glorious protection, to that I offer and consecrate with humble dedication this small, I will certainly not say fruit, but work, of my labours, that will, therefore, have to please You, being on a subject You enjoy. In that, it will be dignified to bend Your Most Serene eye in order that many of your highest rays pass over where the baseness of my ingenuity with the exercise of this art that I have dealt with for twenty-seven years does not arrive. Let this work, humble in of itself, present itself happily to the view of the World. It will be effected with the action of my devotion, together with the fruit of your Most Serene mercy, who serving being the full glory, I pray that Heaven makes me a worthy, even lowest servant. In Venice February 10, 1606.</p> |

:Of Your Most Serene Highness, | :Of Your Most Serene Highness, | ||

| Line 130: | Line 134: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Introduction | ||

| + | | width = 150em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Illustrations<br/>from the 1606</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>[[Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti)|First Edition]] (1606){{edit index|Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>German Translation (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Jan Schäfer]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>French Translation (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | [[File:Nicoletto Giganti portrait.png|400x400px|center|Nicoletto Giganti]] |

| <p>'''To the Lord Readers, Almoro Lombardo,''' Son of the Most Renowned Lord Marco.</p> | | <p>'''To the Lord Readers, Almoro Lombardo,''' Son of the Most Renowned Lord Marco.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Desiring to write on the | + | <p>Desiring to write on the subject of arms, although the author does not mention that it is a science, to me it appears a necessary thing, Lord Readers, to treat with what share it has, and of which name it should be adorned so that everyone knows its greatness, dignity, and privilege.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Thus, before any scholar of this most noble science reads and discusses the most learned and easy observations of the valorous and knowledgeable expert, Nicoletto Giganti, in order to observe the rule and general precept of a person who wants to address anything, I will come to the definition and then to the general division of this word “science”. From these two things it will finally be recognized by everyone that this beautiful profession shows us it is a science.</p> |

| − | <p>Science, therefore, is a certain and manifest knowledge of things that the intellect acquires. It is of two | + | <p>Science, therefore, is a certain and manifest knowledge of things that the intellect acquires. It is of two sorts—that is, speculative and practical. Speculative is a simple operation of the intellect around its appropriate object. Practical only consists in actual workings of the intellect.</p> |

| − | <p>Speculative is divided in two | + | <p>Speculative is divided in two parts—that is, in real speculative and rational speculative. Real aims at the reality of its object, which shows its essence on its exterior. Rational consists in those things that only the intellect administers and does not extend itself further to other goals.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|11|lbl=vii|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|1|lbl=viii|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|11|lbl=vii|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|1|lbl=viii|p=1}} | ||

| Line 149: | Line 168: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Physics is a | + | | <p>Physics is a real speculative science that only aims at moving and natural things, like the elements. Mathematics is a real speculative science that only extends as far as the continuous and the discrete—continuous such as lines, circles, surfaces—the measures of which arithmetic deals with.</p> |

| − | <p>Grammar, | + | <p>Grammar, rhetoric, poetry, and logic are rational speculative sciences. </p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|5|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|5|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 158: | Line 177: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Practical | + | | <p>Practical science is further divided in two: active and productive. Ethics, politics, and economics are active. Productive can be separated into seven others, called mechanical, which are woolcraft, agriculture, soldiery, navigation, medicine, hunting, and metalworking.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|6|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|6|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 165: | Line 184: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Now, | + | | <p>Now, in order to come to what I promised above about this noble science, I will go over its qualities and nature, discussing whether it is speculative or practical science. I say that, in my opinion, it is speculative, and prove it with diverse reasons. There is no doubt that it is science because it is not acquired if not through the operation of the intellect, from which it springs. That it is speculative is certain, as it does not consist in more than the simple knowledge of its object, as I will further demonstrate below.</p> |

| − | <p>The object of this science is nothing more than parrying and wounding. The knowledge of those two things is a work of the intellect, and | + | <p>The object of this science is nothing more than parrying and wounding. The knowledge of those two things is a work of the intellect, and experts of this science do not with intelligence extend it further than the knowledge of them. They cannot be understood at all unless one first has knowledge of ''tempi'' and measures, nor feints, disengages, or resolutions without knowledge of ''tempi'' and measures. These are all operations of the intellect. Moreover, the intellect does not reach beyond this understanding because, as I have said, the aim of this profession is understanding parrying and wounding. We will see whether it is real speculative or rational speculative science, however.</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Thinking on this, it cannot be rational, and the reason is this: Even though it is an operation of the intellect, it nevertheless extends further, wherefore I find it to be real speculative science. Real, because the knowledge of its aim is shown to us outwardly by the intellect, since the understanding of wounding and parrying, along with ''tempi'', measures, feints, disengages, and resolutions, despite being operations of the intellect, cannot be understood if outwardly. This outward expression consists in the bearing of the body and sword in the guards and counterguards, which all consist of circles, angles, lines, surfaces, measures, and of numbers.</p> |

| − | <p>These things, which must be observed, can be read about in Camillo Agrippa and in many other | + | <p>These things, which must be observed, can be read about in Camillo Agrippa and in many other experts of this science. Note that, just as those operations of the intellect without an exterior operation cannot be shown, so these exterior operations cannot be understood without the prior operations of the intellect, in a way that this science, which derives from the intellect, cannot be understood if not outwardly. Neither can it be outwardly understood without operations of the intellect. These operations seek to understand the greatness, excellence, and perfection of this profession, and will always be seen united. As there will never be sun without day, nor day without sun, never will there be those without these, nor these without those. In the end we see that it is real speculative science.</p> |

| − | <p>This science of the | + | <p>This science of the sword, or of arms, is a real speculative mathematical science—of geometry, and arithmetic. Of geometry because it consists in lines, circles, angles, surfaces, and measures, and of arithmetic because it consists in numbers. There is no motion of the body that does not produce an angle or constraint, no motion of the sword that does not travel in a line, no guard or counterguard that does not proceed by number. The observations of these things all depend on knowledge of ''tempi'' and measures, whence I conclude that this most noble science is speculative real mathematical—of geometry and arithmetic—as I said a little above.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/13|1|lbl=ix|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/12|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/13|1|lbl=ix|p=1}} | ||

| Line 182: | Line 201: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Perhaps some inquisitive person arguing over this could say that the science of arms is a | + | | <p>Perhaps some inquisitive person arguing over this could say that the science of arms is a practical science with this reason: Practical science being a science that extends not only to the knowledge of its own object but to its operation, and the science of the sword being a science that applies not just to the knowledge of, but the operation of it, this science is therefore practical and not speculative. To this objection I respond: All things have some operation from nature. Our operations are of three sorts: Some are internal, and these exist in pure and simple intellect and derive from a rational speculative science. Some are internal and external, and these have a commonality inside and outside the intellect and arise from a real speculative science. Some are completely external, and these exist entirely outside the intellect and depend on a practical science. They are either active or productive.</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>Speculative productive real science is no different from practical science other than in this: Real speculative science, even though it operates outwardly in its object, it nevertheless furnishes the understanding of that in the intellect. Practical science not only cannot operate on its object if not outwardly, but also cannot even come to understand it if not outwardly. The science of arms obtains the knowledge of its object in the intellect and, even though it operates outwardly, cannot be said to be practical science. Rather, it is speculative real science.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/13|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/14|1|lbl=x|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/13|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/14|1|lbl=x|p=1}} | ||

| Line 191: | Line 213: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>We have therefore seen that it is a science and it is | + | | <p>We have therefore seen that it is a science and that it is mathematics—of geometry and arithmetic—since it consists in numbers, lines, and measures. The author does not make mention of this in his observations so that learned persons and those with no study may acquire some profit from him. From these figures and his renowned lessons, therefore, without learning to understand the multiplicity of lines, circles, angles, and surfaces which would instead confuse the mind of the reader that does not understand these studies, giving him no instruction, everyone will without doubt or effort learn to understand ''tempi'', measures, resolutions, feints, disengages, and the method of parrying and wounding.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/14|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/14|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|9|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|9|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 198: | Line 220: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>As for | + | | <p>As for learning circles, lines, and other things mentioned above, every studious person will come to understand them with practice. I will always advise everyone to apply himself to the study of letters before this profession, because someone who has studied to understand the necessary things around this science will better profit and become more excellent and perfect, greatly reducing his time to acquire the understanding of the aforesaid things: guards and counterguards, subtle and obvious. He who has not studied will not achieve so easily and, even though he can learn, will not acquire the understanding of this science without length of time and continuous exercise.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/15|1|lbl=xi}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/15|1|lbl=xi}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|10|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|10|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 205: | Line 227: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p> | + | | <p>How great is the dignity and esteem of this profession? What decorum does it seek? What reputation, and how much honour is it due? Under what obligation is someone who carries the sword and makes a profession of it? I say its dignity and consideration entirely derive from its qualities, by the division of which they can be understood.</p> |

| − | <p>This science of the sword is | + | <p>This science of the sword is separated into three parts, and the first is divided in two: natural and artificial.</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>Natural is a demonstrative discourse man makes use of naturally in parrying and wounding, since he proceeds with those goals extracting what mother nature administers to him for his needs with his own ingenuity. This is what many men of courage and spirit have shown great measure of in their contentions with men of great art and knowledge.</p> | ||

| − | |||

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/15|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/15|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|11|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|11|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 216: | Line 239: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>The | + | | <p>The artificial is that which with ingenuity and long use and practice finds different manners of parrying and wounding using the above noted things, encompassed by short rules and extraordinary methods. Accordingly, coming to some occasion, a man extracts the proper terms of safety from this. In his lessons, the author shows great understanding of those two qualities and the reader will be fully satisfied with them.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/15|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/15|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|12|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|12|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 223: | Line 246: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>The second part is this: | + | | <p>The second part is this: The artificial science of the sword is divided in two: demonstrative and practised. Demonstrative is that which shows the proper method and term of parrying and wounding, firm-footed just as with the pass, when one must bind the enemy, and when one must draw back by way of those lines, circles, or circumstances you remember from above, through which the intellect governs and imparts the various and multiple postures and counterpostures of the body. Practised is the same demonstrative which, now that we have acquired it, we apply to the understanding of a thousand warnings. There is no difference between them except that demonstrative is self-contained and practised serves the understanding of various things.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/15|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/16|1|lbl=xii|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/15|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/16|1|lbl=xii|p=1}} | ||

| Line 231: | Line 254: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>The third part is this: | + | | <p>The third part is this: The demonstrative science of the sword is divided in two: the first demonstrative consists of uncomplex terms—that is, simple terms—or composite, which combine multiple demonstrative terms of various circumstances, such as being outside of measure, with the arms open, the weapons high or low. These are called uncomplex terms—that is, terms not understood by the enemy. They are called simple because they are natural. They are called composite because they contain many considerations. These are divided into first and second concepts. </p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>First concepts are real things that are first grasped by the intellect, like parrying and wounding, and these function in first intention. Second concepts are formed by the intellect, and they produce our second intention, knowledge, in order to be capable of wounding and parrying. These are produced by means of the first, for as soon as our intellect has learned this aim of wounding and parrying, it immediately reasons out how it can be done in different manners and with different methods. </p> |

| − | <p>The second | + | <p>The second demonstrative consists in complex terms—that is, terms that combine multiple demonstrative terms—and these terms, either united at measure or separate at a distance, demonstrate their purpose, like how being in guard with the weapons closed demonstrates, either at a distance or at measure of the body’s posture (or counterposture, which is the point of that), how many things can be done with that. For this reason, it is seen how highly regarded this beautiful science is for its qualities and the terms it contains.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/16|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/17|1|lbl=xiii|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/16|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/17|1|lbl=xiii|p=1}} | ||

| Line 244: | Line 267: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p> | + | | <p>And so, this is of great dignity because it is real speculative mathematics—of geometry and arithmetic—and for the many qualities it is found to contain. Thus, I say that it requires decorum and reputation matching its own. It is also to be considered, o Readers, that this science is predominantly found in royal courts and with every prince, studied in the most famous cities by barons, counts, knights, and persons of great quality. This is for no other reason than because, just as it is noble, it excites and inflames our spirits to great things, to heroic feats and actions to measure up to the virtue of the spirit, the valour of the body, the vigour, the strength, and the skill of the person. It always requires an equal match and allows no impugnment of them. It wants to be understood and learned, but not professed, not taken up for every folly. It avoids the disputes of villainous persons. It does not do all that it can but shows itself at the time and place. It shirks the practices of excess and is of few words. It desires a serious comportment, an alert eye, an honoured dress, and a noble practice. This is enough about its decorum and reputation.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/17|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/17|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|15|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|15|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 251: | Line 274: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>In regard to the honour | + | | <p>In regard to the honour it is due, it is to be noted that the observance of all said things is an honour to this profession. It remains only to say what obligation someone who carries the sword is under.</p> |

| − | <p>We will pass | + | <p>We will pass over the terms of these “duellists” who, along with having badly understood said profession, I say that with many of their propositions they also degrade it and have reduced it to such an unhappy state that it not only casts aside the virtuous life, human discourse, and every reason that such a science demands but, forgetting the great God, and themselves as a consequence, their unjust aims only possess it for the damnation of their spirits, abandoning the divine church for their diabolical thoughts.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/17|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/17|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|16|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|16|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 260: | Line 283: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>This profession, o Readers, | + | | <p>This profession, o Readers, places someone who practises it the under obligation to understand that it desires to be used in four occasions: The first for faith, then for country, for defence of one’s own life, and finally for honour. It always wishes to be a champion of reason, never taken hold of in order to do wrong, and someone who does so injures this profession. Neither will a man of honour ever have held onto a wrong in order to fight but will only do so for the said things. It is necessary to have occasion because fighting without one is a thing of the foolish and drunk.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/18|1|lbl=xiv}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/18|1|lbl=xiv}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|17|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|17|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 268: | Line 291: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>Some as soon as they have acquired some beginning of this | + | | <p>Some, as soon as they have acquired some beginning of this, are wont to put the sword at their side and, using a thousand insolences, detain, wound, or sometimes kill some miserable person, believing themselves to have acquired honour and fame. They do evil because, more than harming the nobility of this, which must not be employed without reason, they offend the just God and themselves.</p> |

| − | <p>In order | + | <p>In order not to become tedious I will not continue, but only exhort each person to study such a noble and real science, beseeching him to heed the underwritten observations of our noble expert and to practise them, because with a short period of time no small profit will be acquired, observing how much this befits his own honour, glory, and greatness.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/18|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/18|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|18|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Nicoletto Giganti/1644 German|18|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/9|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/9|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{master subsection end}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{master subsection begin | ||

| + | | title = Clearance and copyright | ||

| + | | width = 90em | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {| class="master" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <p>Illustrations<br/>from the 1606</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> | ||

| + | ! <p>[[Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti)|First Edition]] (1606){{edit index|Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 279: | Line 315: | ||

| <p>'''COPY</p> | | <p>'''COPY</p> | ||

| − | <p>The underwritten Most Excellent Lord Captains of the most Illustrious Council of Ten have belief from the Lord Reformers of the Studio of Padua | + | <p>The underwritten Most Excellent Lord Captains of the most Illustrious Council of Ten have belief from the Lord Reformers of the Studio of Padua through the report of the two elected for such, that is, of the Reverend Father Inquisitor and of the Secretary of the Senate Zuane Maravegia, with oath, that in this book titled School, or Theatre by Nicoletto Giganti, Venetian, nothing contrary to the law is found, it is worthy of print, and they grant it licence to be printed in this city.</p> |

:Dated the 31st of October, 1605. | :Dated the 31st of October, 1605. | ||

| Line 287: | Line 323: | ||

::D. Santo Balbi<br/>D. Gio. Giacomo Zane<br/>D. Piero Barbarigo | ::D. Santo Balbi<br/>D. Gio. Giacomo Zane<br/>D. Piero Barbarigo | ||

| − | :::Most Illustrious Council of X. Secretary, Barth. Cominus. | + | :::Most Illustrious Council of X. Secretary,<br/>Barth. Cominus. |

:October 3, 1605 | :October 3, 1605 | ||

| Line 295: | Line 331: | ||

:::Giovanni Francesco Pinardo, Secretary | :::Giovanni Francesco Pinardo, Secretary | ||

| {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|19|lbl=xv}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|19|lbl=xv}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>December 23, 1605, in Senate</p> | |

| − | <p>The power is granted to our faithful Nicoletto Giganti, Venetian, that other than him or | + | <p>The power is granted to our faithful Nicoletto Giganti, Venetian, that other than him or someone at his behest, it is not permitted for the space of the next thirty years to venture to print in this city, nor any other city, land, or place of our domain, nor printed elsewhere to conduct or sell in our domain the book composed by him, titled School, or Theatre, under pain of losing the printed or conducted works, which are by the aforesaid Nicoletto Giganti, and being obliged to observe what is required by our law in matters of printing, of paying three hundred ducats: A third to our arsenal, a third to the magistrate that makes the execution, and the other third to the complainant.</p> |

| − | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|20|lbl=xvi}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| − | {{master end}} | + | {{master subsection end}} |

| − | {{master begin | + | {{master subsection begin |

| title = Rapier | | title = Rapier | ||

| width = 150em | | width = 150em | ||

| Line 316: | Line 348: | ||

{| class="master" | {| class="master" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | ! <p> | + | ! <p>Illustrations<br/>from the 1606</p> |

! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> | ! <p>{{rating|C}}<br/>by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> | ||

| − | ! <p> | + | ! <p>[[Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti)|First Edition]] (1606){{edit index|Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Jeff Vansteenkiste]]</p> |

| − | ! <p>German (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>by [[Jan Schäfer]]</p> | + | ! <p>German Translation (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Jan Schäfer]]</p> |

| − | ! <p>French (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>by [[Olivier Delannoy]]</p> | + | ! <p>French Translation (1619){{edit index|Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Olivier Delannoy]]</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 333: | Line 365: | ||

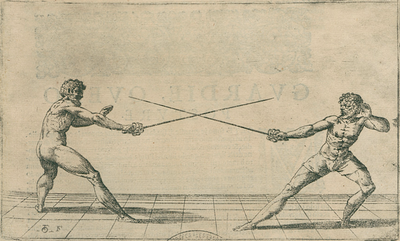

| <p>[1] '''Guards and Counterguards'''</p> | | <p>[1] '''Guards and Counterguards'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>It is necessary for someone | + | <p>It is necessary for someone wishing to become an expert on the science of arms to understand many things. To give my lessons a beginning, I will first begin to discuss guards and counterguards, or postures and counterpostures, of the sword. This because, coming to some incident of contention, it is first necessary to understand this to be able to secure oneself against the enemy. To position oneself in guard, therefore, many things must be observed, as seen in my figures: Standing firm over the feet, which are the base and foundation of the entire body, in a just pace, restrained rather than long in order to be able to extend, holding the sword and dagger strongly in the hands, the dagger now high, now low, now extended, the sword now high, now low, now on the right side, in place in order to parry and wound so that the enemy, throwing either a thrust or cut, can be parried and wounded in the same ''tempo'', with the ''vita'' disposed and ready because lacking its disposition and readiness it will be an easy thing for the enemy to put it into disorder with a ''dritto'', a ''riverso'', a thrust, or in some other manner, and even if such a person were to parry, they would remain in danger. It is advised that the dagger should guard the enemy’s sword because if the enemy throws, it will parry that, and that the sword should always aim at the uncovered part of the enemy so that he is wounded when throwing. This is all the artifice of this profession. Moreover, it must be noted that all motions of the sword are guards to those who know them, and all guards are good for the practised person, as, on the contrary, no motion is a guard to those who do not understand any, and they are not good for those who do not know how to use them.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|22|lbl=02|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|1|lbl=03|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|22|lbl=02|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|1|lbl=03|p=1}} | ||

| Line 343: | Line 375: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[2] This profession | + | | <p>[2] This profession requires nothing more than science and practice. Practised, it bestows the science. Placing oneself uncovered in guard is artifice and done so that the enemy disorders himself when throwing and ends up in danger. Placing oneself covered is also artifice because, binding the enemy, it is possible to wound. In this way, it can be understood that every guard aids those who understand and know, and no guard is valuable to those who do not understand or know. This is enough about guards.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/11|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/11|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 350: | Line 382: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[3] As for | + | | <p>[3] As for counterguards, it is advised that someone who has knowledge of this profession will never position himself in guard but will seek to position himself in a counterguard. Wanting to do so, know this: One must position oneself outside of measure—that is, at a distance—with the sword and dagger high, strong with the ''vita'', with a firm and stable pace, then consider the guard of the enemy. Afterwards, approach him little by little, binding with the sword to be safe—that is, almost resting your sword on his so that it covers it—because he will not be able to wound if he does not disengage the sword. The reason for this is that in disengaging he performs two actions: First, he disengages, which is the first ''tempo'', then wounding, which is the second. While he disengages, he can come to be wounded in many ways in the same ''tempo'' before he has time to wound, as will be seen in the figures of my book. If he changes guard due to the counterguard, it is necessary to follow him with the sword forward, with the dagger alongside always securing his sword, because in the first ''tempo'' he will always have to disengage the sword and necessarily ends up wounded. Neither will it ever be possible for him to wound if not with two ''tempi'', and from those parrying will always be a very easy thing. This is enough about guards and counterguards.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/23|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 359: | Line 391: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[4] '''Tempo and Measure'''</p> | + | | <p>[4] '''''Tempo'' and Measure'''</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>It is not through knowing how to position oneself in a guard or counterguard, nor how to throw a thrust, an ''imbroccata'', a ''mandritto'', or a ''riverso'', nor how to turn the wrist, nor how to carry the body well, nor how best to control the sword, that a person can be said to know how to parry and wound. Rather, it is by understanding ''tempo'' and measure. Someone who does not understand these, even though he parries and wounds, could not be said to understand how to parry and wound, because such a person can err and incur a thousand dangers in parrying as in wounding. </p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|1|lbl=04}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|1|lbl=04}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/12|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/12|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 368: | Line 400: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[5] | + | | <p>[5] Having therefore discussed guards and counterguards, it remains to discuss ''tempo'' and measure in order to then know how to accommodate a recognition of when one must parry and wound.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/12|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/12|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 375: | Line 407: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[6] | + | | <p>[6] Measure, then, means when the sword can reach the enemy. When it cannot, it is called being out of measure.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 384: | Line 416: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[7] Tempo is | + | | <p>[7] ''Tempo'' is recognized in this way: If the enemy is in guard, one needs to position oneself outside of measure and advance with one’s guard, securing oneself from the enemy’s sword with one’s own, and put one’s mind on what he wishes to do.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/25|1|lbl=05|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/24|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/25|1|lbl=05|p=1}} | ||

| Line 392: | Line 424: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[8] If he disengages, in the disengagement | + | | <p>[8] If he disengages, in the disengagement he can be wounded, and this is a ''tempo''. If he changes guard, while he changes is a ''tempo''. If he turns, it is a ''tempo''. If he binds to come to measure, while he walks before he arrives at measure is a ''tempo'' to wound him. If he throws, parrying and wounding in one ''tempo'' is also a ''tempo''. If the enemy stands still in guard in order to wait and you advance to bind him and throw where he is uncovered when you are at measure, it is a ''tempo''. This is because in every motion of the dagger, sword, foot, and ''vita'', such as changing guard, is a ''tempo'' in the way that all these things are ''tempi''—because they contain different intervals. While the enemy makes one of these motions, he will certainly be wounded because while one moves one cannot wound. It is necessary to learn this in order to be able to wound and parry. I will be demonstrating more clearly how one must do so in my figures.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/25|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/25|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/13|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/13|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 399: | Line 431: | ||

|- | |- | ||

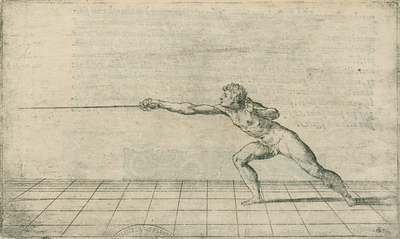

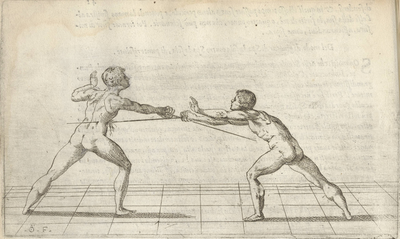

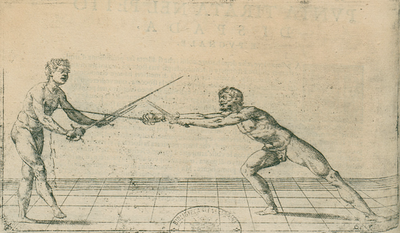

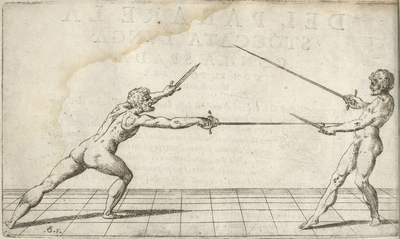

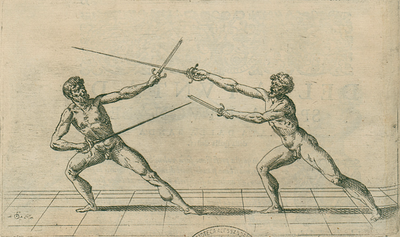

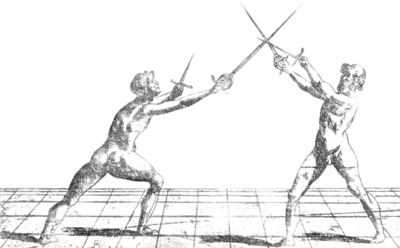

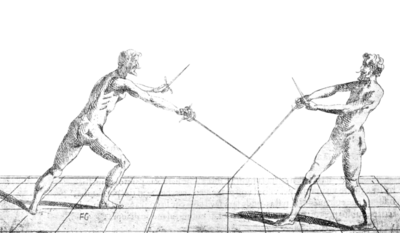

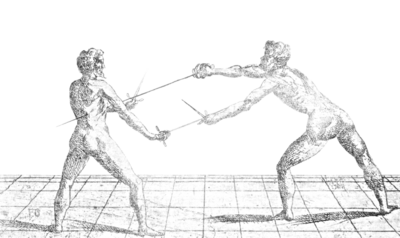

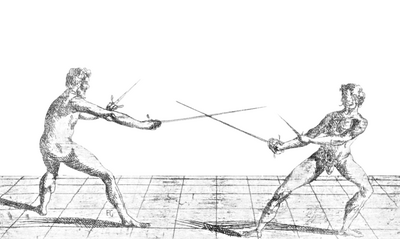

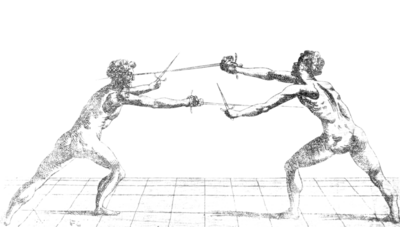

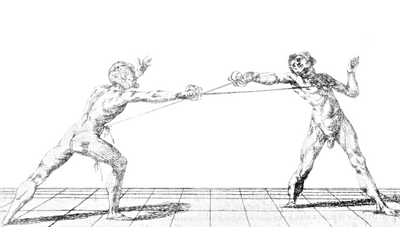

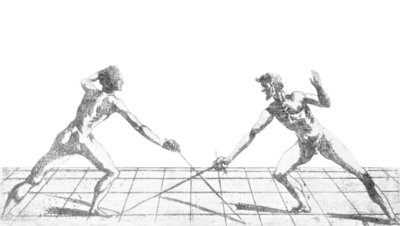

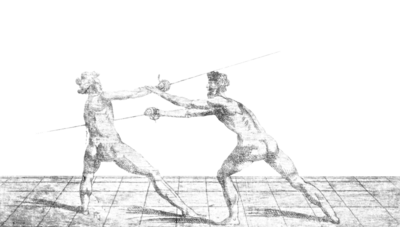

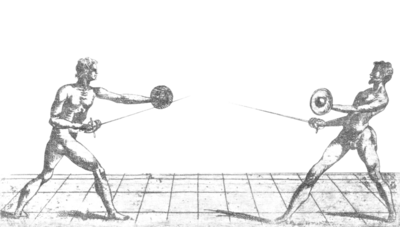

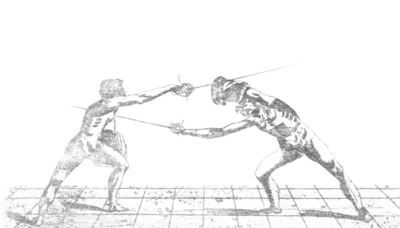

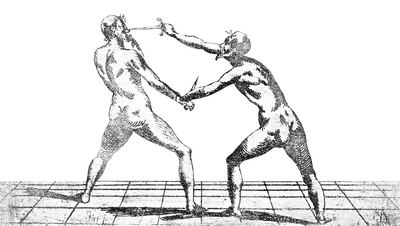

| [[File:Giganti 01.png|400x400px|center|Figure 1]] | | [[File:Giganti 01.png|400x400px|center|Figure 1]] | ||

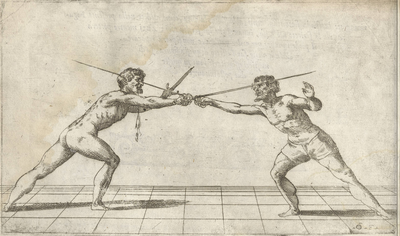

| − | | <p>[9] | + | | <p>[9] ''The method of throwing the ''stoccata</p> |

| − | <p>Now that we have discussed | + | <p>Now that we have discussed guards, counterguards, measures, and ''tempi'', it is necessary to demonstrate and make understood how one must carry the ''vita'' in order to throw a ''stoccata'' and escape, since, wishing to learn this art, it is first necessary to know how to carry the ''vita'' and throw long ''stoccate'', as seen in this figure. All lies in throwing long, brief, strong, and immediate ''stoccate'', withdrawing backward outside of measure. To throw the long ''stoccata'', one must position oneself in a just and strong pace, short rather than long in order to be able to extend and, in throwing the ''stoccata'', stretch the sword arm, bending the knee as much as possible. The proper method of throwing the ''stoccata'' is, after being positioned in guard, it is necessary to throw the arm first, then extend forward with the ''vita'' in one ''tempo'' so that the ''stoccata'' arrives and the enemy does not perceive it. If the ''vita'' were brought forward first, the enemy could notice it and, availing himself of the ''tempo'', be able to parry and wound in one ''tempo''.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|1|lbl=07}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|1|lbl=07}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/14|1|lbl=05}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/14|1|lbl=05}} | ||

| Line 408: | Line 440: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[10] In withdrawing backward one must first | + | | <p>[10] In withdrawing backward, one must first bring back the head, since behind the head will follow the ''vita'', and afterwards the foot. Bringing the foot back first and leaving the head and ''vita'' forward keeps them in great danger.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/14|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/14|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 415: | Line 447: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[11] Therefore, to learn this art well one must first practise throwing this stoccata. Knowing | + | | <p>[11] Therefore, to learn this art well, one must first practise throwing this ''stoccata''. Knowing this, the rest will be learned easily, and not knowing it, the contrary. Be advised, Lord Readers, that in my lessons I will place this method of throwing the ''stoccata'' many times where appropriate. This I know makes the lessons better understood. It is not said of me that I say one thing many times.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 424: | Line 456: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[12] | + | | <p>[12] ''Why begin with the single sword''</p> |

| − | <p>In my first book of arms I | + | <p>In this, my first book of arms, I intended to discuss only two kinds of weapons—that is, the single sword and the sword and dagger— setting aside discussion of some others. If it pleases the Lord, I will publish on all sorts of weapons as soon as possible. Because the sword is the most common and frequently used weapon of all, I wanted to begin with it, since one who understands playing with the sword well will also know a little of how to handle every other kind of weapon. Since it is not customary in every part of the world to carry the dagger, targa, or rotella, and as fighting with the single sword often occurs, I urge everyone to learn to play with the single sword first, in spite of everything that one might have in frays, such as the dagger, targa, or rotella, since occurring, as it many times does, that the dagger, targa, or rotella falls from his hand, it would be possible for a man to defend himself and wound the enemy with the single sword, and because one who is practised in playing with the single sword will know how to parry and wound just as well as if he had sword and dagger.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/27|4|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/16|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/16|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 433: | Line 465: | ||

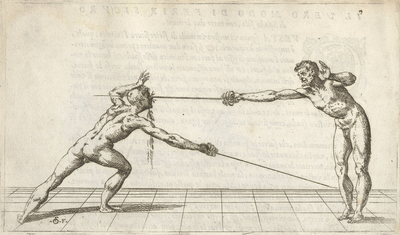

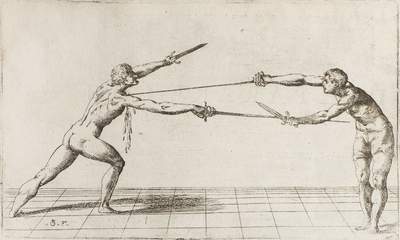

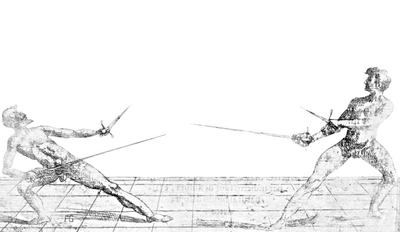

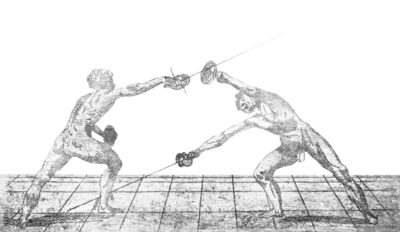

|- | |- | ||

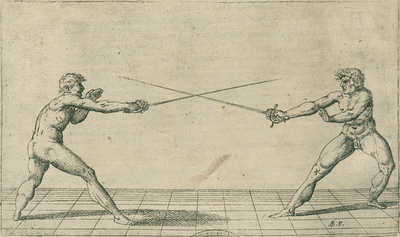

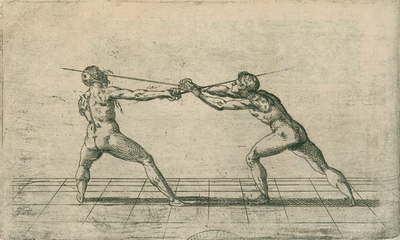

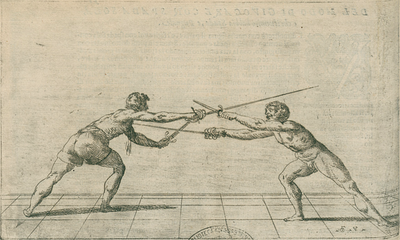

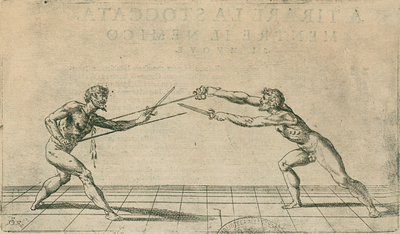

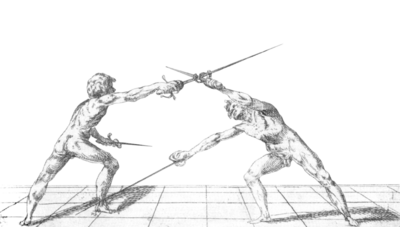

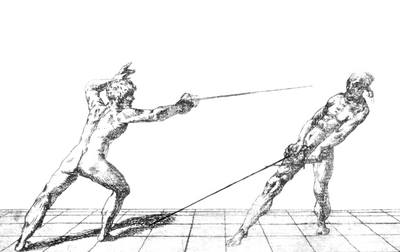

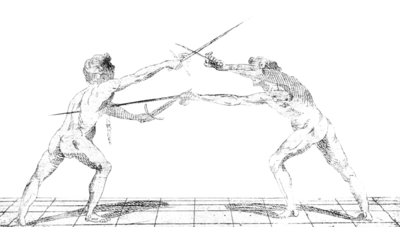

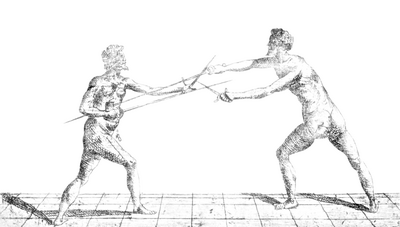

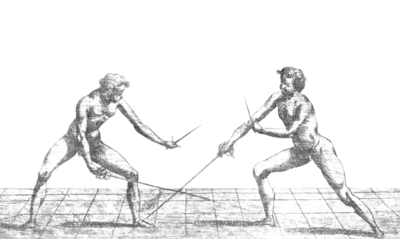

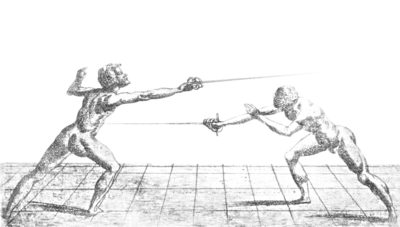

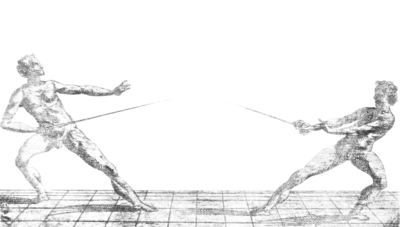

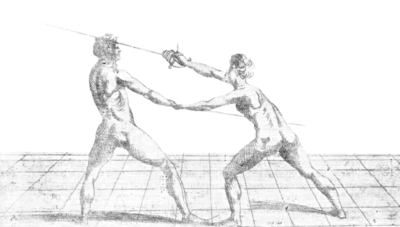

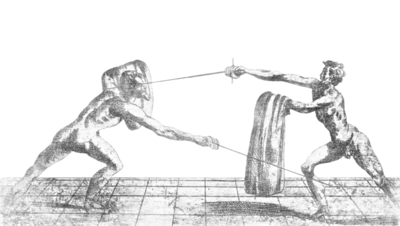

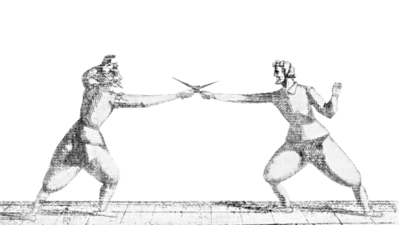

| [[File:Giganti 02.png|400x400px|center|Figure 2]] | | [[File:Giganti 02.png|400x400px|center|Figure 2]] | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

[[File:Giganti 03.png|400x400px|center|Figure 3]] | [[File:Giganti 03.png|400x400px|center|Figure 3]] | ||

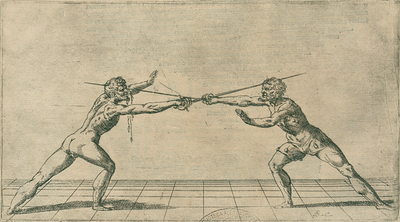

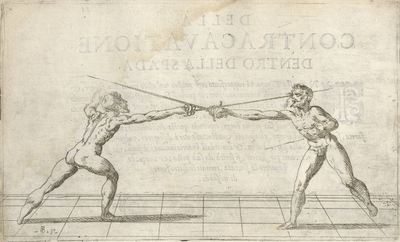

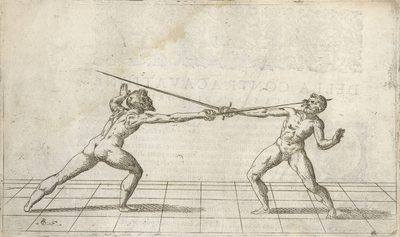

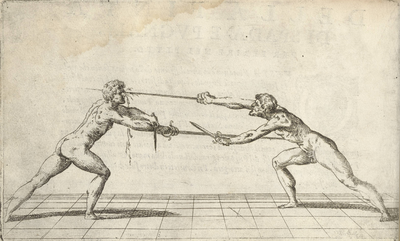

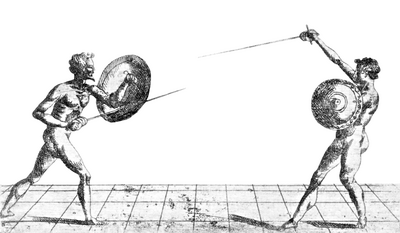

| <p>[13] '''Guards, or Postures'''</p> | | <p>[13] '''Guards, or Postures'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>Many are the guards of the single sword, and many still the counterguards. In my first book I will | + | <p>Many are the guards of the single sword, and many still the counterguards. In my first book I will teach no more than two sorts of guards and counterguards, which you will be able to avail yourself of for all lessons of the figures of this book. Therefore, before coming to do what you desire, you must go to bind the enemy outside of measure, securing yourself from his sword by placing your sword over his in a way that he cannot wound you if not with two ''tempi'': One will be the disengage of the sword, the other wounding you. You will arrange yourself in this way against all the guards, either high or low, according to how you see your enemy arranged, always taking care not to give him ease and opportunity to wound you in a single ''tempo''. You will do this if you take care that the point of his sword is not toward the middle of your ''vita'' so that, pushing his sword forward quickly and strongly, he cannot wound you. Therefore, cover the enemy’s sword with yours as you see in this figure so that the enemy’s sword is outside of your ''vita'' and he cannot wound you if he does not disengage his sword. Arrange yourself with your feet strong, stable with your ''vita'', with your sword arm extended and strong in order to parry and wound, as the figure shows you. If you were to see the enemy in a high or low guard and did not position yourself in a counterguard and secure yourself from his sword, you would be in danger even if your enemy had lesser science and lacked practice compared to you, since you could produce an ''incontro'' and both wound each other, or he could put you on the defensive, or rather, in obedience, with feints or disengages of the sword or other things that are possible. If you secure yourself from the enemy’s sword as I said above, he will not be able to move or perform any action that you will not perceive and be able to defend from with ease.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|30|lbl=10|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/31|1|lbl=11|p=1}} | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|30|lbl=10|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/31|1|lbl=11|p=1}} | ||

| Line 447: | Line 480: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[14] These figures here are two guards with the swords forward | + | | <p>[14] These figures here are two guards with the swords forward and two counterguards covering the sword. One is made going to bind the enemy on the inside and the other going outside, as these figures show you and as I will go about showing you in the subsequent lessons.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/31|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/31|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/20|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/20|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 454: | Line 487: | ||

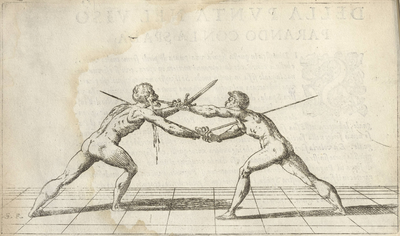

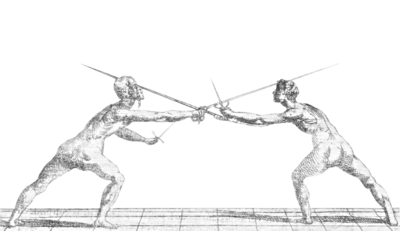

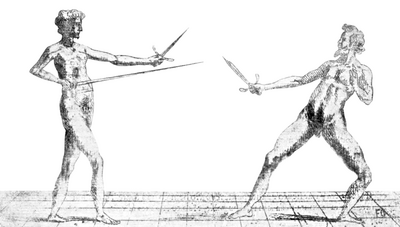

|- | |- | ||

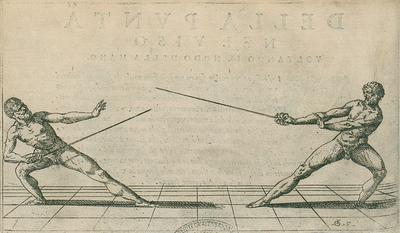

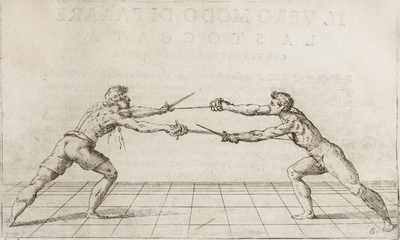

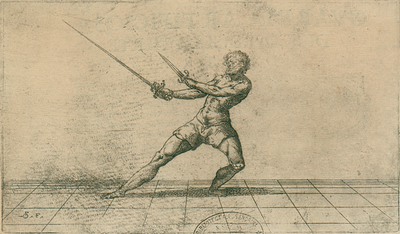

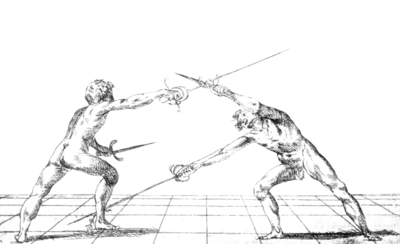

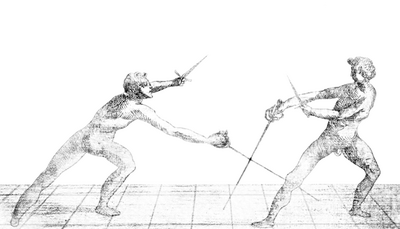

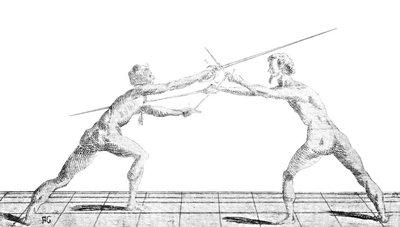

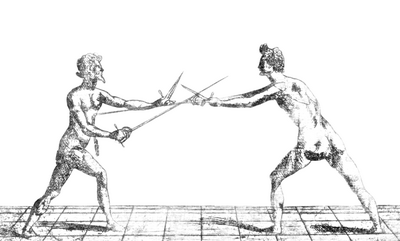

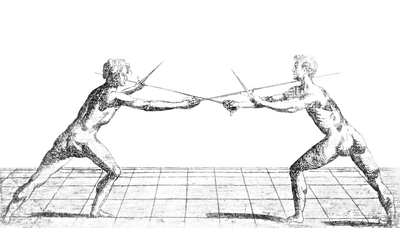

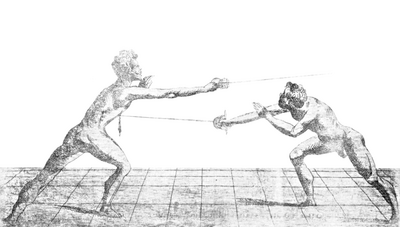

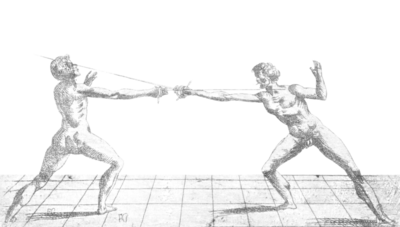

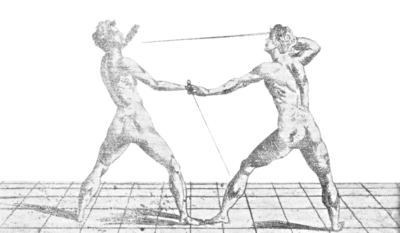

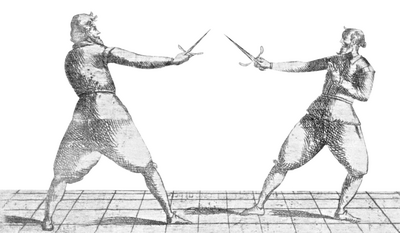

| rowspan="2" | [[File:Giganti 04.png|400x400px|center|Figure 4]] | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Giganti 04.png|400x400px|center|Figure 4]] | ||

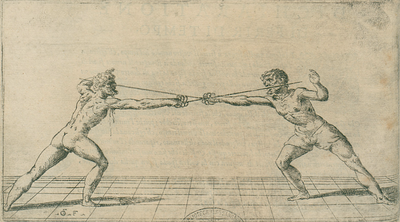

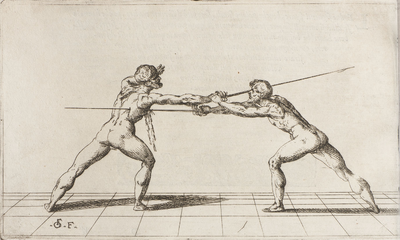

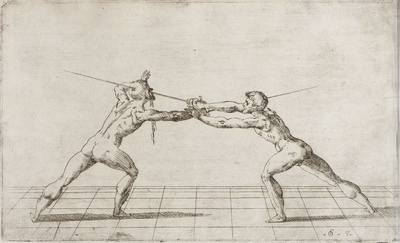

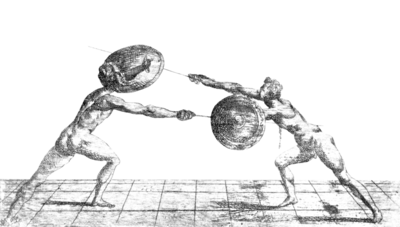

| − | | <p>[15] '''Explanation of Wounding in Tempo'''</p> | + | | <p>[15] '''Explanation of Wounding in ''Tempo'''''</p> |

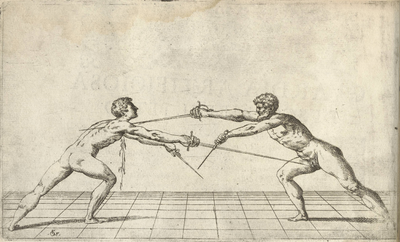

| − | <p>This figure teaches you to wound your enemy in the tempo he disengages his sword. You do this by approaching to bind the enemy outside of measure, placing your sword over his to the inside as the figure of the first guard shows you<ref>Although the plates depicting the guards and counterguards are somewhat less than clear, we know from this chapter that Figure 2 depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the inside.</ref> so that he will not be able to wound you if he does not disengage the sword. Then, in the same tempo that he disengages to wound you, push forward your sword, turning your wrist in the same tempo so that you wound him in the face as | + | <p>This figure teaches you how to wound your enemy in the ''tempo'' that he disengages his sword. You will do this by approaching to bind the enemy outside of measure, placing your sword over his to the inside as the figure of the first guard shows you<ref>Although the plates depicting the guards and counterguards are somewhat less than clear, we know from this chapter that Figure 2 depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the inside.</ref> so that he will not be able to wound you if he does not disengage the sword. Then, in the same ''tempo'' that he disengages to wound you, push forward your sword, turning your wrist in the same ''tempo'', so that you wound him in the face as seen in the figure. In the case that you were to attempt to parry and then wound, it would not be successful, since the enemy would have time to parry and you would be in danger, but if you enter immediately forward with your sword in the ''tempo'' that he disengages his, turning your wrist and parrying, the enemy will have difficulty defending himself.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|1|lbl=13}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|1|lbl=13}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|1|lbl=09}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|1|lbl=09}} | ||

| Line 469: | Line 502: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[17] In the case that the enemy does not disengage his sword to wound you, I want you to advance to bind him | + | | <p>[17] In the case that the enemy does not disengage his sword in order to wound you, I want you to advance to bind him inside of measure and immediately throw a thrust at him where he is uncovered, returning backward outside of measure and resting your sword over his.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/33|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/21|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 478: | Line 511: | ||

| <p>[18] '''The Proper Method of Going to Bind''' the Enemy and Strike Him while he disengages the sword</p> | | <p>[18] '''The Proper Method of Going to Bind''' the Enemy and Strike Him while he disengages the sword</p> | ||

| − | <p>From this figure you learn that if your enemy is in a guard with the sword on the left side, high or low, you approach him to bind him outside of his sword outside of measure, with your sword over his so that it barely touches it, with a just and strong pace, with your sword ready to parry and wound, with an alert eye, as you see in the second figure of the guards and counterguards.<ref>Figure 3, which we know from the description of this chapter’s action depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the outside.</ref> You being | + | <p>From this figure you learn that if your enemy is in a guard with the sword on the left side, high or low, you approach him to bind him on the outside of his sword from outside of measure, with your sword over his so that it barely touches it, with a just and strong pace, with your sword ready to parry and wound, and with an alert eye, as you see in the second figure of the guards and counterguards.<ref>Figure 3, which we know from the description of this chapter’s action depicts binding the enemy’s sword on the outside.</ref> You being arranged in this way, your enemy will not be able to wound you with a thrust if he does not disengage the sword. While he disengages, turn your wrist and in the same ''tempo'' throw a ''stoccata'' at him as the fourth figure teaches you. Having thrown this ''stoccata'', in the same ''tempo'' immediately return backward outside of measure, resting your sword over his so that if he were to attempt to disengage anew, you will throw the same ''stoccata'' at him again, turning your wrist as above and returning outside of measure. As many times as he disengages, that many times you will use the same method of turning your wrist and throwing the ''stoccata'' at him.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|1|lbl=15}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|1|lbl=15}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/23|1|lbl=10}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/23|1|lbl=10}} | ||

| Line 485: | Line 518: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[19] | + | | <p>[19] Much practice is required to perform this play well, since from this one learns to parry and wound with great skill and speed. Take care to always be balanced with your ''vita'' and to parry strongly with the ''forte'' of your sword because, if your enemy throws strongly at you, parrying strongly will make him disconcerted and you will be able to wound him where he is uncovered. This must be the first lesson that one learns with the single sword, since all the others that I have placed in this book arise from it. Knowing how to do this in ''tempo'' teaches you to parry all the cuts and resolute thrusts that can come for the head, which I will teach hand in hand in the subsequent lessons.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/36|1|lbl=16|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/35|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/36|1|lbl=16|p=1}} | ||

| Line 497: | Line 530: | ||

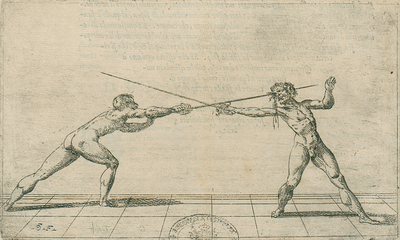

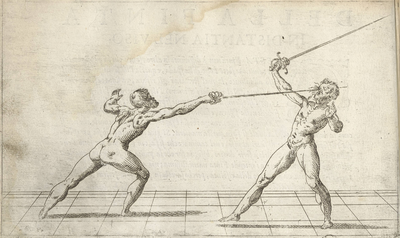

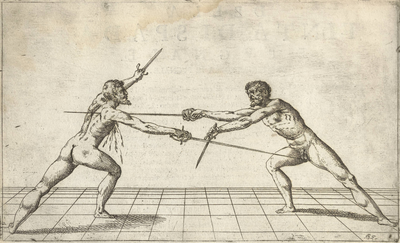

| <p>[20] '''The Proper Method of Disengaging the Sword'''</p> | | <p>[20] '''The Proper Method of Disengaging the Sword'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>The two figures | + | <p>The two figures placed above taught to wound the enemy while he disengages his sword. Because I would not leave a thing in my lessons that is not more than clear, I want to show you the method of disengaging the sword. Note, however, that your enemy being positioned in whichever sort of guard he wants, you having gone to bind him, throw a ''stoccata'' at him where he is uncovered and, if he knows as much as you, your swords will always be equal. I want you then to disengage the sword under the hilt of that of the enemy, quickly turning your wrist and throwing a thrust where you find him uncovered in the same ''tempo''. This is the proper and safe method to disengage the sword and wound in one ''tempo''. If you were to disengage your sword without turning your wrist, you would give the enemy a ''tempo'' and place to wound you, as you will see quite well in practising and trying it yourself. If the enemy were to parry, disengage again in the aforesaid way, always turning your wrist. As many times as he parries, disengage just as many other times in the above way, which is safest, then throw the ''stoccata'' at him in the ''tempo'' that you disengage. This method of disengaging is no less necessary than what was taught in the explanation of the previous figure on the method of parrying, since this is the main thing required in handling the single sword. Therefore, I exhort everyone to practise these two things well since, being at measure against the enemy, as soon as it is the ''tempo'' to disengage the sword, one should know how to disengage quickly and well, and as soon as it is the ''tempo'' of parrying, know how to parry similarly well.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/36|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|37|lbl=17|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/36|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|37|lbl=17|p=1}} | ||

| Line 507: | Line 540: | ||

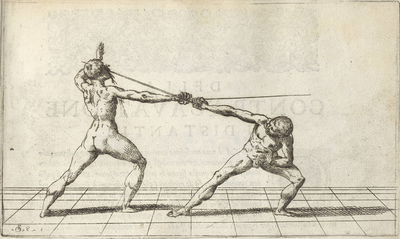

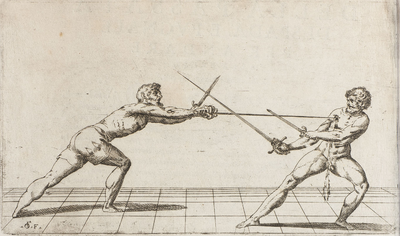

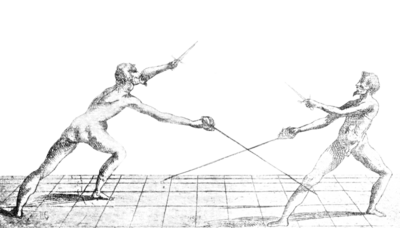

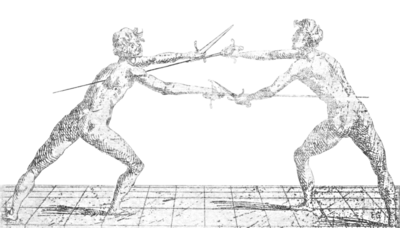

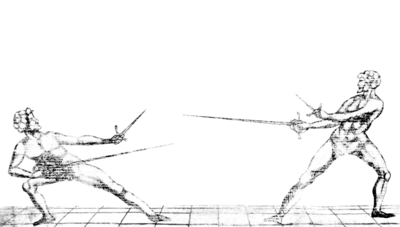

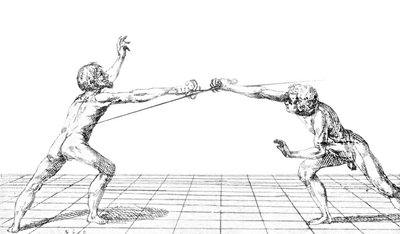

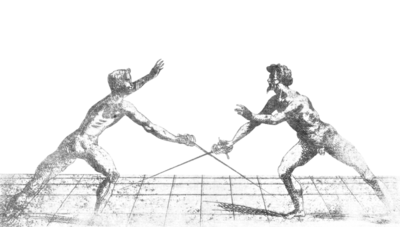

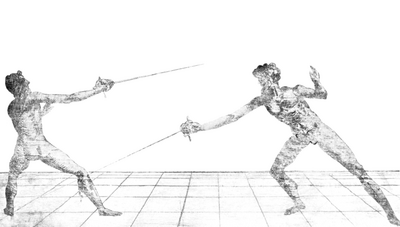

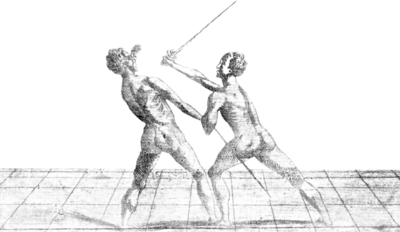

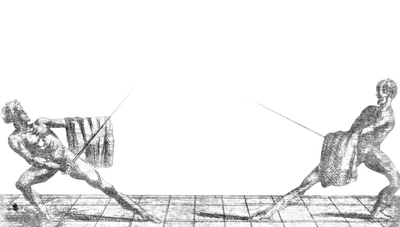

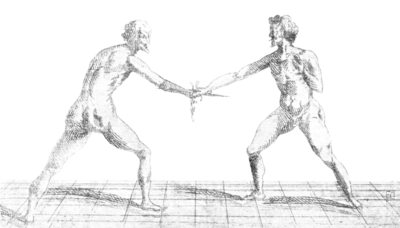

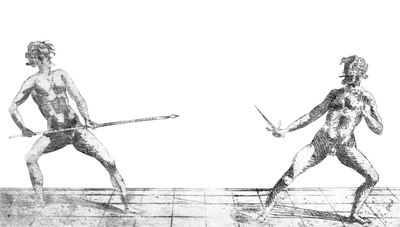

|- | |- | ||

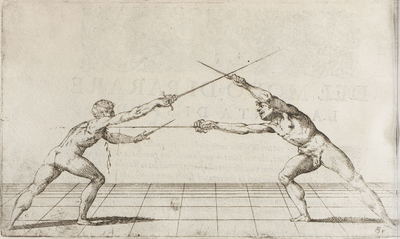

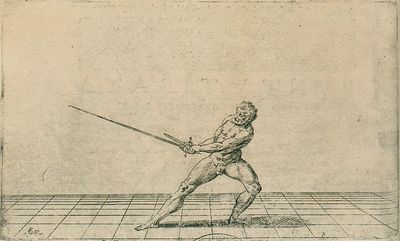

| [[File:Giganti 06.png|400x400px|center|Figure 6]] | | [[File:Giganti 06.png|400x400px|center|Figure 6]] | ||

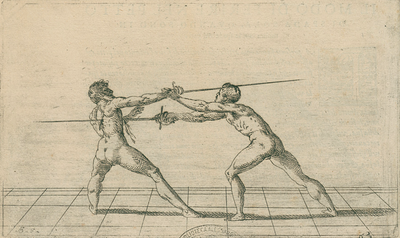

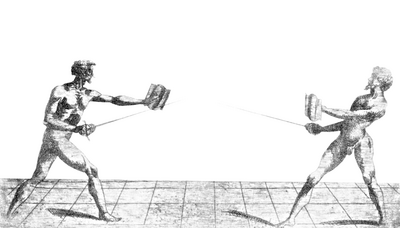

| − | | <p>[21] '''The Inside | + | | <p>[21] '''The Counterdisengage Inside of the Sword'''</p> |

| − | <p>In this figure<ref>Reading the text, Figures 6 and 7 appear to be swapped, meaning this lesson’s text refers to Figure 7. Interestingly the plate order does not appear to be corrected in subsequent printings, even in Jakob de Zeter’s German/French version (1619), which uses entirely new plates created by a different artist.</ref> another method of parrying and | + | <p>In this figure,<ref>Reading the text, Figures 6 and 7 appear to be swapped, meaning this lesson’s text refers to Figure 7. Interestingly, the plate order does not appear to be corrected in subsequent printings, even in Jakob de Zeter’s German/French version (1619), which uses entirely new plates created by a different artist.</ref> I depict and show you another method of parrying and wounding—by way of counterdisengage. It is done in this way: Having covered your enemy’s sword so that if he wishes to wound you, he must disengage, while he disengages, I want you also to disengage so that your sword returns to its first position, covering that of the enemy. But, in disengaging, availing yourself of the ''tempo'', throw a ''stoccata'' at him where he is uncovered, turning your ''vita'' a little toward the right side and holding your arm stretched forward so that if he comes to wound you, he will wound himself of his own accord. Having thrown the ''stoccata'', return backward outside of measure.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|39|lbl=19}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|39|lbl=19}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/26|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/26|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 518: | Line 551: | ||

| <p>[22] '''The Counterdisengage of the Sword on the Outside'''</p> | | <p>[22] '''The Counterdisengage of the Sword on the Outside'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>This method of wounding<ref>This lesson’s text refers to Figure 6.</ref> by | + | <p>This method of wounding<ref>This lesson’s text refers to Figure 6.</ref> by means of an outside counterdisengage is similar to the inside counterdisengage, only there is a difference: Your enemy being in guard and you coming to bind, being outside of measure, you must position yourself in a counterguard, securing yourself from his sword on the outside and making the enemy resolve himself to disengage. While he disengages, you disengage again in the same ''tempo'', turning the point of your sword under his along with your wrist, resting the ''forte'' of the edge of your sword and going along its edge, holding your arm long and extended, loosening the ''vita'' and lengthening the pace, as seen in the figure, so that you come to wound him without him perceiving it.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/41|1|lbl=21}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/41|1|lbl=21}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/28|1|lbl=13}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/28|1|lbl=13}} | ||

| Line 525: | Line 558: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[23] | + | | <p>[23] Be advised, though, that if the enemy throws the sword strongly, wishing to disengage yours so that the enemy does not reach and wound you, you must hold your ''vita'' back in your disengage so that you stay safe. Supposing the enemy had thrown strongly, he would disconcert himself and come to be wounded on your sword and you will stay superior to him, being able to wound him where you see fit, taking care to always hold your sword outside of your ''vita'' so that he cannot wound you.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/41|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/41|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/28|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/28|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 534: | Line 567: | ||

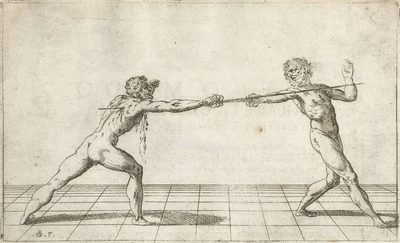

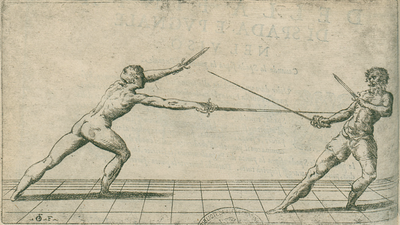

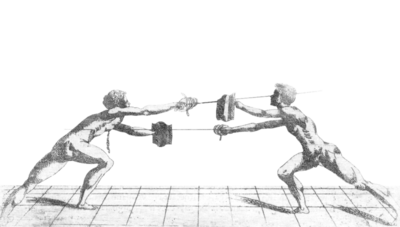

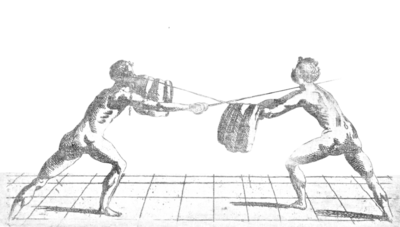

| <p>[24] '''Explanation of the Feint,''' ''Making a show of disengaging the sword with your wrist''</p> | | <p>[24] '''Explanation of the Feint,''' ''Making a show of disengaging the sword with your wrist''</p> | ||

| − | <p>The ways of wounding are various and consequently my lessons are also various. | + | <p>The ways of wounding are various and, consequently, my lessons are also various. Do not at all expect me to recount all things that are possible in this profession, however. Those being infinite, my work would be too long and bring tedium to its Readers. However, I will untangle those things that to me appear most beautiful, artificial, and useful, from which arise many others easier and less artificial.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|1|lbl=23}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|1|lbl=23}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/30|1|lbl=14}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/30|1|lbl=14}} | ||

| Line 541: | Line 574: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[25] Therefore, among all the methods of wounding | + | | <p>[25] Therefore, among all the methods of wounding with artifice, in my opinion the feint exceeds all others. This is nothing more than hinting at doing one thing and doing another. It is done in different ways, and they are these: I want you to position yourself standing on the right side, with the sword forward and your right arm extended in order to give your enemy occasion to come bind you. As he comes to measure with you, observe whether he wants to wound you from a firm foot or instead with a pass. You will recognize this at the disengage you perform with the sword. Disengage the sword with your wrist and feign throwing a thrust at his face but throw wide of the enemy’s sword so that it does not find yours. If the enemy does not parry, throw it resolutely so that you wound him. If he parries, in his parrying redisengage the sword and wound as you see in this figure, where the enemy carelessly wounds himself. In redisengaging, take care that you do not let the sword be found because then your plan would fail, and, in disengaging, bring the head and ''vita'' back a little in order to see what the enemy does because if he were to throw and you had not pulled back, he could produce an ''incontro'' and you would wound each other. Moreover, you must be advised to run with the right edge of your sword along the edge of the enemy’s sword, turning the inside of your wrist upwards in wounding with your sword over the ''debole'' of that of the enemy. As soon as the ''stoccata'' is given, either resolute or feinted, return backward outside of measure, securing yourself as I showed you above.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|1|lbl=24|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/43|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|1|lbl=24|p=1}} | ||

| Line 551: | Line 584: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[26] The feint is therefore performed in this way: | + | | <p>[26] The feint is therefore performed in this way: First the sword is presented to either the face or chest of the enemy, then the arm is extended without stepping. Whence, if the enemy attempts to parry, you disengage the sword in the same ''tempo'', accompanying it forward with the step so that you wound him unawares.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 558: | Line 591: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[27] If he does not parry, | + | | <p>[27] If he does not attempt to parry, extend the pace and strike him. This is the method of wounding by feint.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf/44|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 565: | Line 598: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[28] | + | | <p>[28] Even though they appear similar, the following two figures are nevertheless different from each other because they contain different methods of feinting. Although they contain almost the same end to their wounding, and it would have sufficed to place a single figure with which to discuss and teach different methods of feinting in order to wound, in order to show clearly the different ways of feinting I wanted to put two of them here that differ widely from each other, which I show you in their explanations.</p> |

| {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|45|lbl=25}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Scola, overo teatro (Nicoletto Giganti) 1606.pdf|45|lbl=25}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|4|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Escrime Novvelle ou Theatre (Nicoletto Giganti) Book 1 1619.pdf/32|4|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 572: | Line 605: | ||

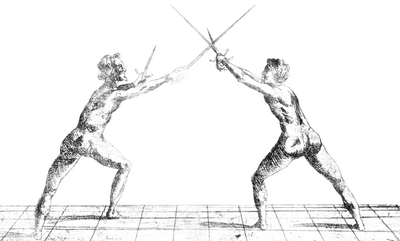

|- | |- | ||

| [[File:Giganti 09.png|400x400px|center|Figure 9]] | | [[File:Giganti 09.png|400x400px|center|Figure 9]] | ||