|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Sebastian Heußler"

| Line 930: | Line 930: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | {{reflist}} | + | {{reflist|1}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT: Heußler, Sebastian}} | {{DEFAULTSORT: Heußler, Sebastian}} | ||

{{Liechtenauer tradition}} | {{Liechtenauer tradition}} | ||

Revision as of 22:41, 24 August 2020

| Sebastian Heußler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1581 Nuremberg |

| Died | after 1645 (?) |

| Spouse(s) | Sabina Prünsterer |

| Relative(s) | Leonhard Heußler (father) |

| Occupation |

|

| Movement | Freifechter |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | Johann Daniel Lange |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Early New High German |

| Notable work(s) |

|

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

Sebastian Heußler was a 17th century German Freifechter. A native of Nuremberg, Germany, he was the eldest son of printer Leonhard Heußler, and as a youth he was trained in his father's craft. It is unclear if he was apprenticed to Christoph Lochner, but he was working as a type-setter in Lochner's workshop by 1599. He married Sabina Prünsterer in 1601 and purchased a house in Nuremberg in 1603. Heußler probably certified as a master printer during this time, and he was listed in the records of the printing guild from 1601-04 and again in 1607.[1]

In 1608 at the age of 27, Heußler abandoned his craft and henceforth devoted himself to studying the Chivalric Art of Fencing that had captivated him since childhood (he may also have been focused on fencing during his sabbatical from printing in 1605-06).[2] Heußler seems to have originally been a student of Hans Wilhelm Schöffer von Dietz, the fencing master of Marburg, which is also where his education in the style of Salvator Fabris began.[citation needed] He ultimately left his native Germany, where he said that the arts were less cherished, and traveled through Italy, France, England, and the Netherlands.[3] Heußler is described as both a Kriegsmann (man-at-arms) and monatsreiter ("month-rider"), which seems to indicate that like many fencing masters he supported himself as a mercenary.[4] He likely held the elite position of color guard in his unit,[2] as he would later author a book on the art of flag-waving. It's unclear how much time Heußler spent in Nuremberg after 1608; he moved his wife to a new home in 1615, but in 1617 when the old home was sold, his wife negotiated the deal in his absence.[4]

In 1615, Heußler authored a fencing manual entitled Neu Kunstlich Fechtbuch ("New Illustrated Fencing Manual"), illustrated by noted Nuremberg engraver Gabriel Weyer and printed by the son of his former master, Ludwig Lochner. The book treats the use of the rapier, a system described as being in the style of the famous Italian masters Ridolfo Capo Ferro da Cagli and Salvator Fabris.[3] The following year he co-authored his New Kůnstlich Fahnenbůchlein ("New Illustrated Flag-Waving Manual") with Johannes Renner. Heußler's fencing manual was apparently well-received, and was reprinted at least seven times (in whole or in part) over the subsequent fifty years.

Little is known of Heußler's life after the publication of his books. Some sources assume him dead by 1630, but there is record of a General Sebastian Heußler serving the King of Denmark in 1645;[4] it cannot be determined at this time whether this is a reference to the fencing master or not.

Contents

Treatise

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

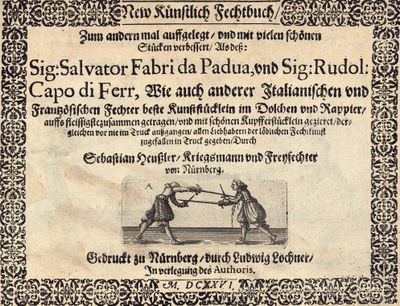

| New Illustrated Fencing Manual, remastered from other times/ and with many fine Techniques Revised/ From:

Sig: Salvator Fabris da Padua, and Sig: Ridolfo Capo Ferro, also how other Italian and French Fencers have diligently summarized the best Artful Techniques in Dagger and Rappier, and with beautiful copperplates adorned, the likes of which, have never before in print been done, All Lovers of the praiseworthy Fencing arts are given this laid out in Print Through: Sebastian Heussler, Kriegsmann and Freifechter from Nuremberg |

||

| The main Thrusts are Four, of the Italian Manner: Prima, Secunda, Tertia, Quarta | ||

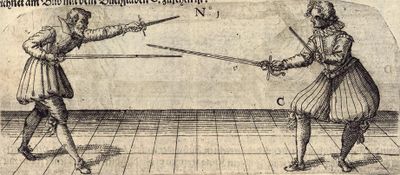

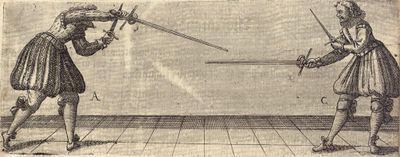

| Firstly, how you should position yourself in the Guard

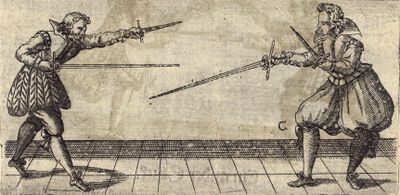

1 When one presents the half body, then with your right side, turn forward, how in this Image with the number 1. is reported, and can be seen by the figure with the Letter C. |

||

| When you now have thus positioned yourself, and you think that you will be in the Measure, thus step with the Right foot straight in at him, and stab with the Quart inside at his right breast with a step to of the right foot, how is seen in figure D. | ||

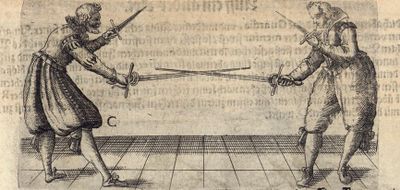

| 2. When the thrust comes, thus step with your right foot again, back, and take your Blade inside in these that you step back with, be over his blade, thus is his blade; Stringiret, how this is shown by the following Figure C. | ||

| As soon as he would again try to go under and around your blade, thus pay careful attention to the Timing, when he tries to go under and around, that you with the Tertia outside thrust straight over the half strong of his rappier, in to his right breast, stepping to him with your right foot. | ||

| 3. When the thrust comes, thus step back, again with your right foot, and take your Blade again outwards and above his, thus is his blade yet again; Stringiret, as soon as he would go under and around with his blade, thus pay careful attention to the Timing, of his goings, that you thrust quickly with the Quarta inwards at his right breast, with a step to him of your right foot, how in the forgoing Image, it can be seen. | ||

| On another Art

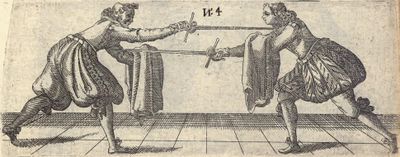

4. Position yourself again in your Guardia, and with your Blade go at him inwards on his Blade when you thus think that you will be in the Measure, thus stab a stiff thrust inwards at the opponents right breast. As soon as the Thrust occurs, thus step with your right foot back again, and take your Blade inwards over and above his, thus is his Blade once more, Stringiret, and give to him a little opening outside and above your right arm, thus as soon as he will thrust in at you outside and over your right arm with his Tertia, thus parry his thrust away, above his right side, and stab in at his right Breast, with the reverse (rivers) outside above his right arm, with a step to of the right foot. How this image with the Figure marked D is showing. |

||

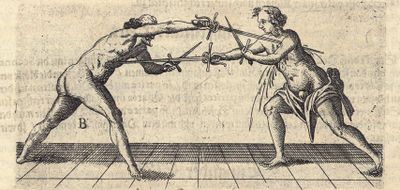

| Follow now how you should thrust in Contra Tempo

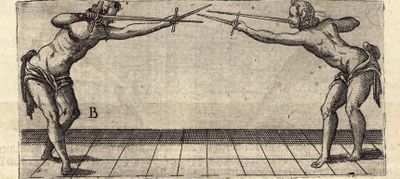

5. Position yourself in your Guardia, how you are shown in the previous figure 1. as soon as he then stabs in at you, thus parry away his thrust under towards your right side and thrust with the Second Contra Tempo, at the same time as him towards his upper body, how the Image with the Letter B shows, with a step to of the right foot, parry with the Dagger, and thrust, this must always happen in a timing: |

||

| 6. If he then would make a Finda under your dagger, and would thereafter quickly thrust in, outwards over your Dagger, thus pay great attention to his thrusts from over your dagger, and that you turn your upper body, and parry his thrust away with your Dagger above towards your left side, and thrust with the Quarta at the same time as him underneath towards his right breast with a step to of the right foot, how you are shown in this picture with the letter D. | ||

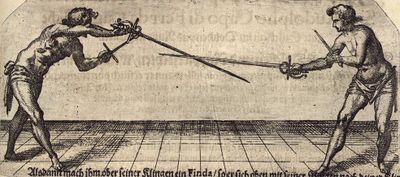

| Follow how one should make the basic Finda

7. When someone will extend their dagger well towards you, and give you the opening under his dagger, thus go at him with the point of your Rapper forwards against his Dagger, battire then with you right foot, when you think that you will be in the Measure, thus perform a Finda, hard inwards by his Dagger, how in this Figure you see. |

||

| As soon as he will take out the Finda with his Dagger from under towards his left side, Thus cavire close and tight under his Dagger and thrust with the Second outwards above his Dagger how you will see in the following Figure, and with a step to of the right foot, with your dagger Parry away his thrust down towards your right side. B Follows? | ||

| Follow how you should perform a Finda outside and above his Dagger

6 If one should give to you the opening outside and above his Dagger, thus go also with your Rappier's point forward and against his Dagger, as soon as you think that you will be in the Measure, thus Battire with the right foot and perform a Finda with the Secunda outside and over his dagger, how you are shown in the following image with the letter B. |

||

| As soon as he now will try to take you out with his Dagger using the same Finda, above towards his left side, thus cavire wind inwards and under his Dagger, and thrust with the Quarta outside under his left arm, how the preceeding Figure with the number 2 can be seen. | ||

| 7. When the Thrust occurs, thus fall with your kl: (Klingen?) wind him inwards on his Blade, thus you hinder him in his counter thrust, and stringire in the same his kl: thereby, thus as soon as he goes through under your Blade, or outside over your blade and means to thrust in, thus parry away his thrust with your Dagger, above towards your right side, and thrust with the Riversa outwards above his right Arm, how you can see in the Image with the Letter B. | ||

| And this mark especially as a certain rule. When you thrust in, on someone under his dagger or between his rappier and dagger, that as soon as the thrust occurs, that you always fall on his blade from the inside, that he then cannot thrust at you. | ||

| Follow how one should perform the Double Finda

8 If someone lies before you with outstretched Dagger, and gives you the opening under his dagger, thus go at him with your Rappiers point forward at his Dagger, when you then think that you will be in the Measure, thus battire with your right Foot and perform on a him a Finda with the Secunda, hard inwards by his dagger, thus when he then will take you out with his dagger, from under towards your left side, then Cavire close and tight under and around his dagger, and perform in on him a Finda with the Secunda outside and over his Dagger, if he would then drive up towards his left side with his dagger, thus stab swiftly the Quarta outside and under his dagger, how you here can see in the Image marked with the Letter D. |

||

| From another Art

9. If one gives you his opening outside and over his dagger, thus go at him also with the point against his Dagger, battire then with the right foot, and perform the Finda on him, with the Secunda outwards and above his Dagger, if would do the same to you with his Dagger from above towards his left side and try to take you out, cavire quickly through, from under his Dagger, and perform a Finda on him, outwards under his Dagger, would he do the same with His Dagger, to parry you out, also under towards his left side, thus stab in quickly with the Secunda outwards while over his Dagger, with a step to of the Right foot, and with your Dagger, parry away his Blade under towards your right side, how the Image with the Letter B shows. |

||

| Follow now how one should perform the Finda from Below.

10. When someone lies before with outstretched Dagger, and gives you the outside opening under his dagger, so face him thusly, allow your rappiers point to sink a little underneath, how you see in the Image with the Letter C: and go in at him a little to his left side. |

||

| Then, when you think that you will be in the Measure, thus battire with your right foot, and let your point fly in, from below, and at the same time perform a Finda with it outside of his Dagger, as soon as he would take you out with his dagger, above towards his left side, thus heave your point in over his Dagger, thus would he with his Dagger make the mistake, thrust in with the Quarta between his rappier and dagger, towards his right breast, how in this Image with the Letter D can be seen. | ||

| Another Device

11 Position yourself once again, how it is instructed above, when you then think that you will be in the Measure, and he gives you his opening to his inside body, thus battire with the right foot, and let your blade fly in from below, and perform a Finda in at him against his face, if he would then do the same Finda with his Dagger take you out, from above towards his right side, thus heave your Blade in, over his Dagger, and thrust with the Secunda over his Dagger, and with your dagger however, parry away his Blade down towards your right side, you can also very well from here perform the Finda from below towards his face, and if he would not take you out with his dagger, thus allow your Rappiers' point to quickly again sink down, and thrust with the Quarta inwards towards his right breast. |

||

| How one should from perform a Finda with the Secunda before his Dagger

12 If he positions himself with his dagger rather far from him, outstretched, thus go at him a little to his left side, when you then think that you will be in the Measure, then battire with your right foot and go at him with a finda with the Secuda under his Dagger, as soon as he would do the same Finda with his dagger towards his right side, and parry you out, thus step in to him deep with your right foot, and thrust in with the Quarta between his rappier and dagger towards his right breast, how it can be seen in the preceding image Number 6 with the letter D.: When the thrust occurs, thus fall quickly again with your Blade inwards on his blade; and stringire bind him on his blade with it. |

||

| Now follow how you should cut to his right leg

13 If he positions himself with his Dagger well to you outstretched, thus perform in to him an outward Finda over his Dagger and remain with your Blade on his dagger, as soon as he would thrust inwards towards you, then parry away his thrust with your dagger, down towards your right side, and allow your blade to run off from your right side, cut then with a step to of the right foot, towards his right leg or ear, how the following Image shows. |

||

| On another Art

14. Position yourself in your guardi, and someone would thrust in at you, thus parry away his thrust down towards your right side, quickly let this run off then from your right side, and cut him outwards at his right leg, how it is intructed above, as soon as the cut occurs, spring quickly again backwards, and see that, with this, you come in the over Secunda, would he then quickly thrust with the same inwards on you, thus parry away his thrust down towards your right side, and thrust in with the Prima or Secunda Contra Tempo, at the same time as him, how it can be seen in the preceding image marked number 7. |

||

| 16. When the thrust occurs, thus step with the right foot again rearwards, and position yourself with your Rappier in the Quarta Guardi, how you will be shown in the following Image. | ||

| As soon as he then will thrust in from the outside, over your right Arm, thus parry away his thrust with your Dagger above, towards your right side, and thrust in with the Riversa from outside and over his right arm, how it is seen in the preceding image with the Number 8. | ||

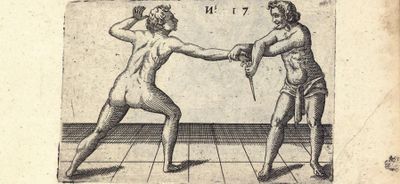

| 17 When the same thrust also occurs, thus step with your right foot again rearwards, and position yourself in your Guardia, How it is seen in the preceding Image with the Number 1. | ||

| As soon as he will thrust in, after you, thus parry his thrust away with your Dagger, down towards your right side, and thrust with the Secunda Contra tempo along with him, with a step to of the Right foot, how in the preceding image with the number 5 it is recorded: | ||

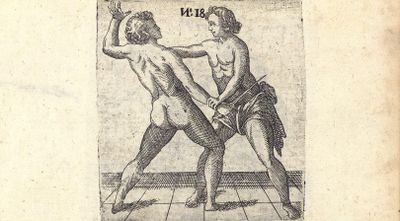

| 18 That he would do the same Chiamata as you would do to him, but he will not thrust after, thus battiren quickly with your right foot, and perform the Finda inside by his Dagger, would he also this same Finda parry out towards his left side, thus cavire tight and close under his Dagger, and thrust in with the Secunda outside, over his dagger with a step to of the right foot | ||

| Follow how you should perform a Chiamata inside by his dagger

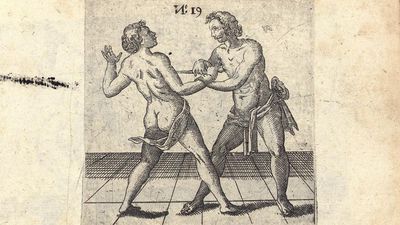

19 If one gives you his opening inside of his Dagger, then thrust in Hard with the Secunda inside by his dagger, this thrust however, don’t do fully, but rather step with your right foot quickly again rearwards, and pull your Blade towards you nearly in the high Secunda, and expose your inside Body with that, thus as soon as he will thrust to the opening, then parry his thrust away with your dagger down towards your right side, and thrust along with him, with the Secunda Contra tempo, towards his inside opening, with a step to of the right foot. |

||

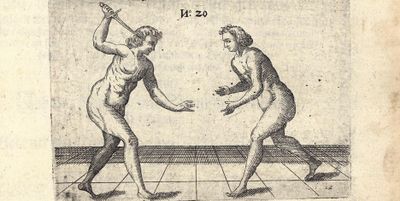

| 20 But when he would not thrust in to the opening that you invited him to with the chiamata, thus perform the Finda (in) again how it is instructed inside hard by his Dagger. Thus as soon as he would take you out with his dagger, then Cavir through with your blade under his dagger, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and over his dagger, and with your Dagger parry his blade away down towards your right side. | ||

| How you should perform the Chiamata to someone, under his Dagger

21 If someone lays before you with outstretched Dagger, and give you the opening under his dagger, then, when you think you will be in the measure, thus battire with your right foot and perform a Chiamata under his dagger, quickly then pull your Blade again towards you, nearly in the lower Secunda, and also with your right foot, step a little rearwards, as soon as he then would thrust above to the opening, thus parry away his thrust with your dagger above towards your right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside under his blade, towards his right Breast, how this Image with the Letter B shows: |

||

| 22 When he then thrusts to you above to the opening, and when you have performed the Chiamata, thus you can also parry away his thrust with your Dagger, above towards your right side, and with the riversa outside over his right Arm, thrust in well to his right breast, with a step to of the right foot, how the other Image with the number 6, can be seen as listed. | ||

| How One can use the Retrahiren

24 Retrahire your upper body, and with your blade retrahire also at the same time with it, how you can see in this image; thus you have exposed your outside altogether with it. |

||

| As soon as he would then thrust outside to the opening, then parry away his thrust with your dagger above towards your right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his Blade towards his upper body, how in the preceding Image numbered 9 can be seen. | ||

| 25 You can also do well, with the Riversa: thrust in from outside over his right Arm when you have thus parried away his blade up towards your right side, with a step to of the right foot. | ||

| 26 And he who would not thrust high at your face, after you have exposed yourself to him, and generally would thrust to your lower body, thus parry away his Blade with your Dagger down towards your right side, and thrust in with the Secunda Contra Tempo along with him, outside and over his Dagger. | ||

| 27 You can also do very well, when he thrusts outside to your opening, quickly thrust the Quarta along with him but towards his inward turned body, or if you want, you can also with the Quarta, Voltiren on him. | ||

| 28. You can also do well, when he thrusts outside to your opening, and with your Blade from your left to the right, under his thrust caviren through, and fall on him with your blade, inside on his Blade, without Hope, thrust then with the Quarta inside towards his right Breast with a step to of the right foot. | ||

| On another Art

29 Retrahire once more, thus your Blade, and would he then stringiren outside on your Blade, thus pay strict attention to his stringiret on you, and that you quickly cavirest through under his Blade and thrust in with the Quarta towards his inward turned Body, how you have seen in the preceding Image with the Number 2. |

||

| Another Technique

30 When you thus have retrahiret his blade, and he also stringirete outside on your Blade, thus pay careful attention to, his stringiret on you, and that you quickly caviret through, under his blade, and battire then with the right foot, and perform in on him a Finda inside by his Dagger, as soon as he would with his dagger, drive with the same, to his right side, thus cavire through quickly under his Dagger and thrust in with the Secunda outside and over his Dagger, and with your Dagger parry away his blade down towards your right side. |

||

| On another Art

31 When one positions himself with his dagger a little back away from you, but with his Blade he is rather long, how it is shown in the preceding image with the Number 1: thus stringere his Blade outside, then once he would caviren through under your Blade, pay careful attention to his going through, and that you thrust in with the Tertia outside and over the half strong of his Blade, towards his upper body. |

||

| 32 There he who would lead with his Blade back and above you, when you thrust in on him with the Tertia outside and over the half strong of his Blade, and he performs a Quarta on you, thus parry away his thrust with your Dagger down towards your right side, and thrust with the Secunda Contra tempo towards his upper body, where you will see the Best Opening, how it can be seen in the preceding Image with the Number 9. | ||

| When one would thrust on you, and How you should conduct the Mensur

34 Position yourself in your Guardi, and when he would thrust inside towards your right breast, thus step with the right foot completely back, thus that you come with your left foot forward, and in this back stepping, then parry away his Blade with your dagger above towards your right side, quickly step again into him with your right foot, and thrust in with the Rivers outside and over his right arm, how in this Image it is seen. |

||

| How one should use the Retrahiren

35 You can also do very well, when he then thrusts inside and in on you, and you step back with the right foot, parry away his thrust with the dagger up towards your right side, and in this Parrying, thus wind your Blade upwards in the Secunda, step then with your right foot again into him, and thrust with the Secunda Contra Tempo along with him, towards his upper body, how it is seen in this Image. |

||

| If one thrusts in from well low under his dagger, and would he your same thrust parry away and thrust at you inside quickly after, thus step back again with your right foot, and parry his thrust with your dagger up towards your right side, step then with your right foot again into him, and thrust in with the Riversa outside over his right Arm, how this Image shows. | ||

| Several Techniques from the High Secunda

36. When one is positioned before you with outstretched dagger, thus position yourself in the High Secunda, and with the point, go at him outside over his dagger, then, as soon as he would thrust inside and in on you, and will push out your Blade with his dagger up, towards his left side, thus parry away his thrust with your dagger down towards your right side, and thrust in with the Secunda Contra Tempo outside his dagger. |

||

| 37 And there, he who would not thrust, thus quickly perform a Finda with the Quarta under his dagger, as soon as he will parry this same, thus cavire through again under his dagger, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and over his dagger, and with the Dagger parry away his Blade again towards the right side. | ||

| 38 However, if he holds his dagger away from you, and exploits to you his right side then position yourself in the High Secunda, and go at him well in the measure, so soon as he would thrust inside and in on you, then parry away with the dagger down towards the right side, and thrust with the Secunda Contra Tempo towards his upper body. | ||

| How you should Mutiren with the Flying Blade

39 When one is postioned in his Guardi, thus mutire him down through, with flying Blade under his blade, and with the right foot battire at the same time, when you then think that you will be in the measure, then thrust with the Quarta inside towards his right breast. |

||

| 40 Mutire then thus with flying Blade under his Blade and Dagger, and with the right foot battire, when you then think that you will be in the correct measure, thus cavire through with your blade under his dagger, and then thrust in with your blade outside over his dagger, and with your dagger, parry away his Blade down towards your right side. (((huh???))) | ||

| 41 When the thrust occurs, then step back again with the right foot, and pull your Blade to you in the High Secunda, as soon as he would thrust inside and in to the opening, thus parry him away with your dagger down towards your right side, and thrust with the Secunda Contra Tempo towards his inward turned body. | ||

| On another Art

42 Mutire on one then with the flying blade under his Blade and Dagger, would he then thrust high to the opening, in your mutieresting? thus parry him away with the dagger down towards your right side, and in your parrying, thus cavire through with your Blade under his dagger, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and over his Dagger. |

||

| How you should perform the Finda inside by his Blade

43 When one is positioned with his blade outstretched, straight ahead at you, and with his Dagger is away from you, thus battire with the right foot, and perform a Finda inside with the Tertia, hard by his Blade, would he then want to take out your Finda with his blade towards his left side, thus pay careful attention to the Tempo, and in his taking outs, you quickly cavirest through under his Blade, with that he does not reach your blade, but rather you thrust with the Tertia outside over the Half Strong of his Blade and into his right side. (((?))) |

||

| 44 There he who would against your Tertia outside and over the Half Strong of his blade quickly cavirest through from his left towards his right under your blade, thus work quickly from the Tertia in the Quarta how you can see in this following Image. | ||

| 45 When you thus have thrust in with the Tertia outside and over the Half Strong of his Blade, he quickly Voltirets the Quarta, and would thrust in with the Quarta under your blade, towards the right side, thus pay careful attention to Quarta that he makes, and that you parry away this same with your dagger down towards the right side, and thrust with the Secunda Contra Tempo towards his upper body. | ||

| 46 There he who would lead with his blade back and above you, (against) your thrusting in with the Tertia outside and over the half strong of his blade, thus parry away his Blade with the Dagger up towards the right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his dagger, towards his right side or to his Chest. (((?))) | ||

| Another Technique

46 [47] When one is positioned before you with his dagger well outstretched. And when you then think that you will be in the measure, then battire with the right foot and perform a finda with the Secunda outside on his Dagger, how this Image with the Letter B shows. |

||

| Would he then parry out your finda with his dagger up towards his right side, thus remain with your Blade laying still, and as soon as he would again go back with his Dagger, then step quickly with the right foot into him and thrust with the Quarta towards his right side. | ||

| 48 Position yourself with your dagger almost in the middle Secunda, and leave the point to be seen straight out before you with your body hunched rearward, and with it, give him a little opening of your inward turned body, battire then with the right foot and also strongly to the opponent, will he then to your upper body thrust, thus parry him away with the dagger up towards your right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his dagger, towards his right Breast. | ||

| 49 You can also do very well when you are thus positioned and he would thrust towards your upper body, and parry out his thrust above towards your right side, and thrust in then with the Riversa outside and over his right arm: | ||

| 50 There he who would never thrust to your lower body, when you are postiioned in the aforesaid Guardi, thus parry with the dagger down towards his right side, and thrust with the Secunda Contra tempo at once towards his upper body, where you see the best openings. | ||

| 51 there he who would thrust on you, when you are positioned with the reported Guardi, thus press in, well inside when you then think that you are within reach of his blade, and he lays not to high with his blade, thus step with the left foot in to him, and parry his blade with your dagger down towards your right side, and thrust with the Secunda Contra Tempo towards his upper body. | ||

| 25 [52] There he who would but with his blade lay rather high, and you are positioned in the aforesaid Guardi, then also press in well to him when you then think that you can reach his middle blade, then step into him with the left foot, and parry away his blade with your dagger up towards your right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his Dagger, towards his right Breast. | ||

| How you should perform (on one), a Finda over his Dagger

53 If you go at one with your Blade inside his blade and stringire, his blade with this, as it were, when you then think, that you will be in the correct measure, thus battire with the right foot and perform a Finda with the Secunda in over his dagger, will he with his dagger up towards his left side want to take you out, thus cavire quickly again in over his dagger, and thrust with the Secunda inside towards his Chest. |

||

| How you should perform the Finda as it were, in a half circle

54 If one is positioned with his dagger a little above you, outstretched, thus position yourself with your Blade in the High Secunda, when you then think, that you will be in the measure, thus battire with your right foot, and make as if you would perform in the Finda with the Secunda inside by his dagger, as soon as he will take you out with his dagger, thus cavire with the Secunda like in a half circle, as it were, under and through his Dagger, and do unto him a Finda with the Secunda outside and over his dagger towards his left Eye, will he then do to you the same, and drive with his dagger up towards his left side, then thrust in quickly with the Quarta outside and under his dagger towards his left side. |

||

| How you should thrust outside and over his Dagger

55 If you see the opening outside and over his dagger, then oppose him thusly, go with your Blade outside his Blade, when you then think, that you will be in the measure, thus cavire with your Blade under his Blade and Dagger down through, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and over his dagger, with the dagger however, parry his Blade, in that you pass off, down and away towards the right side. |

||

| 56 If one thrusts in on your inside, thus pay careful attention to his thrusts, that you with the right side or foot step back behind the left foot, and parry his thrust with the Blade, will he quickly again go through under the Blade, and will thrust in over your blade with the Tertia outside, so step back then with the left foot and parry his thrust with the Blade, will he quickly once again go through towards your inward turned body, thus voltire quickly the Quarta, and thrust with the Quarta towards his inward turned body, how this Image shows. | ||

| On another Art

57 If one thrusts in on you to the inside, thus step back with the right foot, and parry his thrust with the Blade, will he quickly again go through, and thrust outside, thus step back with the left foot, and parry that then with your Blade, as soon as he will once again go through, and will thrust inside to your inward turned body, thus parry with the dagger down towards the right side, and thrust with the Secunda Contra Tempo towards his upper body, how this Image shows: |

||

| Another Technique

58 If one thrusts in under his dagger, and when this thrust occurs, then step back with the right foot quickly, and leave your inward turned body open, will he quickly thrust inside to the opening, thus step back with the left foot, and parry away his thrust with your Blade towards his left side, will he quickly again go through, and thust in at you from the outside over your Blade, thus voltire quickly in the Quarta, and thrust under his Blade towards his right side. |

||

| On Another Art

59 Stretch your Dagger well out from you, and position yourself with your Blade in the Secunda, rather high, so that his Blade and your Blade almost come together, and give him the opening under your dagger, as soon as he will thrust in under your dagger, thus parry away with the dagger down towards the left side ???and thrust after that, once you have parried the Quarta inside towards the right side??? |

||

| 60 If he thrusts in however from the outside and over your Dagger, then parry with the Dagger up towards the left side, and you must therewith turn your body well, and with the dagger come back thus will you so much the better thrust????? desto ?ieffer stossen | ||

| Another Technique

61 Position yourself then partly, and he will then perform on you a Finda under the dagger, or will thrust in under your dagger, thus pay careful attention to his thrusts or Finda, that you yourself quickly wind, and thrust with the Quara inside towards his right Breast, his Blade you should not parry with your Dagger. |

||

| How you should stringiren the Blade inside and here in are six techniques to memorize

62 If your Adversarius is positioned with the Blade long before you, and holds his dagger somewhat away from you, so oppose him thusly, when you think that you will be just within the measure, then step away with the left foot straight towards your left side, and when you set down your left foot, thus see that you go inside and on his Blade, at once, step then into him with the right foot, thus will you correctly Stringiren his Blade, and with that come into the Measure, your upper body stretched well before you, will he then quickly go through under your dagger, and thrust in from your outside, over your Blade, thus parry him away quickly with your dagger up towards the right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his Blade. |

||

| 63 You can also do well, when you thus have stringirt, and he quickly goes through under your Blade, and would thrust in on you from the outside and over your Blade, thus parry away his thrust with your dagger up towards his right, and thrust the Riversa. | ||

| 64 You can also do well when he goes through, and will thrust in to you from outside and over your Blade, takeout his thrust with your blade towards the right side, quickly fall then with your dagger outside and on the weak of his Blade, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his blade, how this Image shows: | ||

| 65 When you however, have thus stringirt him, and he goes quickly through and under the Blade, thus have good attention on the tempo, and his going through, that you with the Tertia correctly thrust in, outside and over the half strong of his blade. | ||

| 66 When you have thus Stringirt him, and he would not go through, thus step quickly into him, and thrust into him with the Quarta inside, towards his right Breast. | ||

| On another Art

76 [67] Stringire him then thusly, and as soon as he will go through and under your Blade, and thrust into you, from your outside, over your Blade, then Voltire quickly the Quarta, and thrust in under his Blade, into his inward turned body. |

||

| How you should Stringiren outside

68 If one is positioned in the middle Secunda, and he appears that his point is a little to his left side, thus stringire his blade outside, as soon as he goes through under your Blade, towards your inward turned body, thus parry away his Blade with your dagger down towards the right side, |

||

| 69 There he who would not go through, when you have thus stringiret him, when you then think that you can reach his Blade with your dagger, thus parry away his blade with your Dagger up towards the right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his Blade. | ||

| When one stands with his left foot forward and How you should oppose him

70 Go at him quickly with the Secunda outside his Dagger, quickly then hunch yourself?? (bucke dich) when you think that you will be in the measure, and perform a Finda on him, under his dagger, will he with his dagger take you out, down towards his left side, thus go quickly through once again under his dagger, and thrust in over, with the Secunda outside his dagger. |

||

| 71 You can also do well when you go at him with the Secunda outside and over his dagger, and perform the double Finda, firstly do a find to him under his dagger, and when he will take this out, thus perform them in quickly from outside with the Secunda over his dagger, will he also take this out, then thrust in with the Quarta under his dagger, towards his left side. | ||

| How you should do a Lure to who would thrust after you

72 If one thrusts in right Low under his dagger, and when the thrust occurs, then step with the right foot completely back, thus that your left foot is forward, and with the Blade you come nearly in the guards, like the Caminiren, in the bout, thus will your outside be completely exposed, as soon as he then will thrust to the opening, then parry him with the dagger down towards the right side, and in this parrying, step with the right foot into him, and thrust in with the Secunda Contra Tempo over his dagger. |

||

| 73 You can also do well when you are stepping back with the right foot, and he would thrust in to your opening from the outside, and would thrust rather high, then pay careful attention to his thrust, that you with the right foot step into him, and parry his thrust with your dagger quickly then thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his Blade, with your dagger however, parry away his Blade up towards the right side. | ||

| 74 You can also do well when you thus are stepping back, and your outside is exposed, he then would not thrust in to the opening, thus step with the right foot quickly into him, and perform in on him a Finda with the Tertia outside and over his Blade, as soon as he will take you out with his blade towards his right, thus you parry him away with your dagger up towards the right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his Blade. | ||

| How you should use the Quarta

75 if one thrusts in right low under his dagger, quickly spring back, and expose your outside over the right arm, as soon as he will thrust in to the opening, then Voltire quickly the Quarta and thrust in with the Quarta under his dagger, towards his inward turned body. |

||

| 77 if one positions himself with the Blade long before you, and when you are then still outside the Measure, then step with the left foot straight on into him, and cut inside on his blade, with such cutting will you in the Measure come, and see that you come into the stance with crossed body, as soon as he then will caviren through and under your Blade, and thrust outside over your right arm, thus parry with the Blade, quickly step then with the right foot into him, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his Blade, with your dagger however, parry away his Blade up towards the right side. | ||

| 78. Position yourself nearly in the high Secunda, and give a little opening of your inward turned body, as soon as he then will thrust inside to the opening, then parry with the blade, and unexpectedly thrust then with the Quarta inside towards his Chest, how this Image it can be seen. | ||

| 79. Position yourself in the middle Secunda, and give with it a little opening of your inward turned body, as soon as he will thrust in to the inside opening, then sink your upper body a little behind you, and cavire through with your Blade under his thrust, and thrust in with the Tertia outside and over the half strong of his blade. | ||

| 80 There he who would lead then with his blade above you, when you cavirest through and under his thrust, then parry away his blade up towards your right side, and thrust in with the secunda outside and under his blade. | ||

| When one cuts on you and how you should pull your Blade.

81 Will one cut in on you, and still not be in the measure, thus pay careful attention to his cut, and that you retrahirest your upper body, and your blade pull away towards your right side, and your body pull also to you, therewith he does not cut at your left hand, thus will he completely cut, thrust then quickly with the Secunda towards his upper body, and with the dagger fall outside on his blade. |

||

| How you should cut outside towards his right thigh and hereafter use the thrust with it.

82 Perform a Finda with the Quarta outside his Blade, well to his right Eye, and with a step to of the right foot, then as soon as he will this same, take out with his blade up towards his right side, then step back with the right foot once again, and cut outside towards his right thigh, when you have accomplished the cut, then remain with your blade pointed at the ground, as soon as he then would thrust to the opening, then parry him away with the Dagger up towards the right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his blade. |

||

| 83 You can also do well when you have cut outside towards his right thigh, and he then would thrust quickly to you in the upper opening, parry away his thrust with your dagger up towards your right side and with the Riversa thrust in, from outside and over his right Arm. | ||

| 84 You can also do well when you have cut outside towards his right side, and he then thrusts inside to the openings, then parry him away with the dagger down towards the right side and thrust in with the Secunda Contra Tempo along with him, outside and over his dagger. | ||

| 85 There he who would not thrust to the opening, when you have cut outside at his right thigh, and remained with your blade pointed at the Ground, thus perform quickly a Finda with the Tertia outside his blade, as soon as he will take you out with his blade outside towards his right side, then Passire outside on him, and with the dagger parry away his blade up towards the right side and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his dagger. | ||

| How you should lay your Blade outside on his Dagger

86 If one positions himself with his dagger well outstretched before you, thus lay your blade on his dagger from the outside, as soon as he then will press out your blade up towards his left side, and thrust in quickly at your inward turned body, then parry away his blade with your dagger down towards the right side, and thrust in with the Secunda or Tertia Contra Tempo under his dagger. |

||

| 87 There he who also remains when you have layed and remained on his Blade, thus battire with the right foot and perform a Finda with the Tertia under his dagger, as soon as he will take this same out, with his dagger down towards his left side, and he would quickly thrust inside, thus cavire through under his blade and thrust in with the Secunda outside and over his dagger, with the dagger however, parry away his blade down towards the right side. | ||

| 88 If one is positioned with his dagger outstretched well before you, and thus holds his Blade right under his dagger, how this Image shows: | ||

| As soon as he will parry down towards his left side, thus cavire through and under his blade, and parry away his blade with your dagger down towards the right side, and thrust in with the Secunda Contra tempo outside and over his dagger. | ||

| 89 There he who would with his dagger remain positioned and still, and would not parry, thus battire with the right foot and perform a Finda outside and above his dagger, as soon as he will drive this same up with his blade towards his left side, then thrust in quickly with the Quarta under his dagger. | ||

| How you should position yourself in the Quarta Guardi

90 Position yourself with the Quarta Guardi, and you expose your outside, above your right arm with it, how this Image with the Letter D shows. thus pay careful attention, as at once he will thrust to the outside opening, and that you cavirest under and through his thrust with the balde from the left to the right, and thrust with the Quarta inside towards his right Breast, you may also use the false step as you want. |

||

| On another Art

91 Position yourself once again in the Guardi, as soon as he will thrust in to your opening, and would thrust rather high, towards your right breast, thus parry his thrust away with the dagger up towards the right side, quickly fall then in this which you have parried, with your blade also outside of his blade, and when you are with your blade outside of his blade, thus step with the right foot outside into him, and fall on his blade with your dagger also outside, thrust then with the Secunda towards his upper body, where the Best opening is. |

||

| 92 Position yourself again in the aforementioned Guardi, and if one would thrust in to the outside opening, thus parry his thrust with the short edge, and cut then quickly with the full edge up towards his face, and in cutting, thus cut to the left side also, and with this, retrahiren your upper body, as soon as he then will thrust outside to the opening, thus parry him away with the dagger up towards the right side, and thrust in with the Secunda outside and under his blade. | ||

| 93 Postion yourself again in the Quarta Guardi and one would thrust to your outside opening, thus parry once again with the half edge, quickly step then with the left foot into him from outside, and fall with your dagger on his blade, and thrust then with the Secunda towards his upper body. | ||

| How you should stringiren his blade outside

94 If you see that your opponents' point appears a little towards his left side, thus go at him with the Blade outside his blade and stringire him with the Secunda, when you with the Secunda have stringirest, girest/ thus see that you go a little high with your blade, that your Blade's crossguard, stays nearly even with the right breast, as soon as he then under your blade will caviren through, thus pay attention to his going through, and that you parry him away with your dagger down towards the right side and thrust the Secunda Contra Tempo towards his right Breast. |

||

| How you should stringiren his blade inside

95. If one postitions himself with his Blade rather long before you, thus bedn yourself a little, and stringire his Blade inside, as soon as he will go through under your blade, and means to thrust in at you from outside and over your right arm, thus parry him away with your dagger up towards the right side, and with your Blade fall away under his Blade, and thrust with the Secunda towards his inward turned body. |

||

| Used frequently reported technique ?? lol

96 When to you, one under your Blade, will fall away, thus step with the right foot in that he falls back? and parry away his thrust with the dagger, down towards your right side, and thrust with the Secunda Contra Tempo towards his upper body. |

||

| On another Art

97 If one stays with his left foot forward, thus pay careful attention to that which he will in the Furia on your Passiern, thus go at him with the blade's point nearly before or under his dagger, in his passirt, thus turn yourself quickly with your false step with him towards his inward turned body. |

||

| Another Technique

98 Place yourself with crossed body, and with the blade position yourself in the lower Secunda, and your Cross hold just a little higher than your right knee, and your blade's point leave to be seen straight out before you, thus then you would the inside opening give, and your dagger stretch way out well before you, how this Image shows |

||

| Will he then under your dagger thrust in, thus parry him away with the Dagger down towards his left side, and thrust quickly with the Quarta along with him, with a step to of the right foot inside his blade, towards his right breast. | ||

| On another Art

99 Position yourself once again thusly, and he would not thrust in under your dagger, inside towards the right breast, thus parry away with the dagger up towards the right side and thrust quickly thereafter with the Quarta, that is in with the Riversa, from the outside and over his right arm, towards his right breast how this Image reveals. |

||

| On Another Art

100 When one stays in his guardi and exploits to you his right side, thus hunch yourself hurryingly, and make as if you would thrust inside onto his blade, when you this same Finda with your blade perform, thus stretch the right arm well with it, and will he then with his blade, travel after yours, thus cavire quickly close and tight in his after traveling, under and through his blade, and thrust in with a step to of the right foot with the Tertia outside and over his right arm, you must with the point right under his right hand fall through, and thus outside and over his right arm, Thrust in. |

||

| On another Art

101 If one stays once again with crossed body, and stretches his dagger well out before you, thus hunch yourself once again, going as if would thrust in under his dagger, and stretch the right arm also well with this, when you the finda performs, and make only a half step, will he then with his dagger travel after your blade, thus cavire through under his dagger, and thrust in with the Secunda outside over his dagger, with your dagger parry his blade down towards your right arm throughout |

||

| On another Art

102 Position yourself in the High Secunda with your blade and with short arm, and exploit to him the right side and thrust nearly with behind crossed body, your daggers point leave above you to be seen, and your left arm hold not too wide from you outstretched, and the rear knee should stay bent, and the forward one straight, will he then thrust in to the inside, thus parry away with your dagger down towards the right side, and in this parrying, step into him with the left foot from outside, and thrust in with the Secunda Contra tempo outside his dagger, battiren, thrusting, must all at the same time occur. |

||

| 103 you can also do well when he thus thrusts in on you, and you parry him away with the dagger down towards the right side, quickly leave then runn off to the right side, and cut with a step to of the fight foot outside towards his right ear. | ||

| Several Nice Lectiones from the Prima Guardi

104 Postion yourself in the prima, and sink your body further well before, thus that you yourself look somewhat buckled, therewith the body well in the middle will be withdrawn, how these Images show. |

||

| Will then your Opponent thrust in to the opening inside to your right breast, thus Ligir? his blade quickly with your blade, and in a Tempo thrust with the Secunda straight into his inward turned body. | ||

| 105 there he who will take you out with his dagger up towards his right side, thus pay attention to his attacks to your blade, that you quickly thrust your blade over his dagger with the Secunda onto his left breast, and with your dagger, parry away his blade down towards your right side. | ||

| On Another Art

106 If one is positioned with his blade long before you, and with his blade somewhat behind, thus go at him towards, with the Prima, quickly perform on him outwards on his blade a Ligation, und in a tempo, thurst with the Seucnda on his upper body, with a step to of the right foot. (?) |

||

| 107 there he who would again parry your blade up towards his right side, thus leave quickly your blade go around the head, and cut to his left ear, then as the cut occurs, so spring quickly back, or pull the right foot quickly somewhat to the body, retrahir the body and blade so that you come in to the Quarta Guardi, thus he will thrust also over the right arm to the opening, then thrust quickly the Riversa, and with your dagger parry away his blade up towards the right side. | ||

| How you should perform the double Dinda with the Prima

108 If your opponent is positioned with his blade long, and somewhat behind, thus perfom on him the Prima firstly a Ligation outwards on his blade who in these Images it is seen, |

||

| And then do to him over his Blade a finda, that he will drive up with his blade towards your blade, thus do the other to him below, and in a tempo thrust in quickly with the Prima over his blade toward his upper body | ||

| NOW FOLLOW of the WIDELY FAMOUS Mr. Rudolpho Capo di Ferr da Cagli several good devices in dagger and Rappier fencing;.

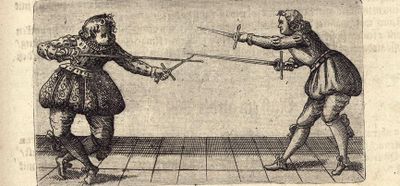

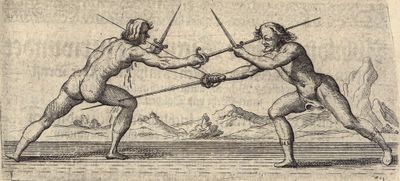

Portraits of the Dagger and rappier fencing, which shows how one should stringiren the Opponent's Rappier, when he lies firstly high above and turned inwards, especially when the opponent goes with his point at your right Shoulder, thus must you lie outwards, the same as one should make the other guards traditionally. |

||

| 1 the following Images show that dagger and Rappierfencing, primarily exhibits that it is of the opponents' Rappier to Stringiren, thus firstly lay high, but still all Guards cannot be suggested by an Image, namely high and behind to lay, inwards and outwards to stringiren, | ||

| Therefore one who is an informed reader will attribute, alone it is looked upon, that when the opponents' point winds against your right side, should you oppose outside, and when oppose that you should the lower guards Stringiren, so must it happen with the Weapon in hanging blade, thus well in the third?, than in the fourth, how in these Images can be seen. | ||

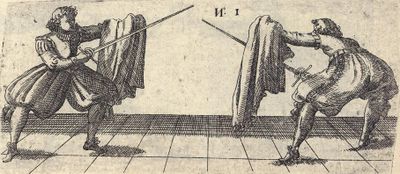

| Image which shows how one can takes out with the dagger and harm the enemy in three places, namely in the Angesicht, to the Heart, and Thigh. | ||

| 2. This following Image shows what is skillful, that one in three different points the enemy can be thrusted, from only one taking out with the dagger, which from the following knowledge should happen, When your opponent his guard inside have bound upon, be in the type of guard that it may, thus inwards it is neatly to stringirest? he can take you out and in two different ways thrust you in the face and chest. The when he has cavirted to wound you, then must you inside with the dagger take out his rappier over your right Arm, and in the first opportunity, you can from high above thrust behind, namely in the face or under the shoulder to the Chest, or thigh, in the other united only in the face or Thigh,. how this Image witnesses. | ||

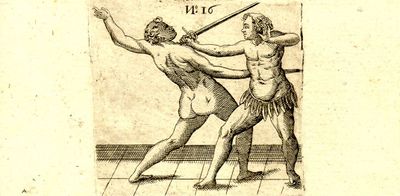

| Illustration of a figure that wounds their opponent, in on the right arm or chest and makes him the weapon to deploy, through ausswindung with his weapon and dagger | ||

| From this Image can one easily understand and learn the the Weapon from the hand to take, and also in this same thing the tempo with the Point on the Chest to thrust, namely: | ||

| When you find yourself in Terita with drawn arm, and the dagger with the Weapon are together, and when you find the enemy in the Quarta or in your same guard, thus cut on inwards to his blade with your Quarta to stirngiren, and leave your dagger against his right side straight in ahead or Obliqua Lines sink down, thus when your enemy goes through to harm your chest with the Quarta, thus parry in the same Tempo with the flat of your dagger from outside to underneath you, and with winding around his point, heave the Crossguard of your Weapon aboveyou, so you harm him outside on the body and oppose in that he his weapon with power must let fall. ??? How this following Image shows. | ||

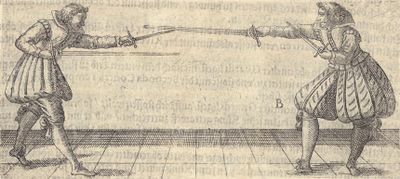

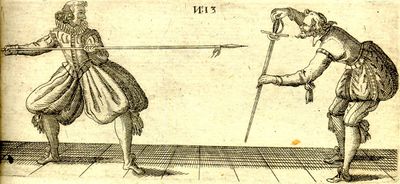

| Illustration of a figure that is parrying inside and high with the dagger and wounds his opponent on the right Leg with a Revers and with the Quarta to the Chest. | ||

| When you find yourself in Quarta with your dagger high, and your Opponent in whatever Guard he wants, still with your right foot forward, that one can bind on him inside, thus hew into him inwards, to stringiren with the Quarta and thus when he cavirts you to harm you with his Quarta to the face, then parry inside with your dagger above your right Arm, thus you can harm him with a revrsa to his leg, or with the Quarta under the Arm, how the following Image shows. | ||

| E N D E |

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

| Nº. 1 | ||

| Nº. 2 | ||

| Nº. 4 | ||

| Nº. 5 | ||

| Nº. 6 | ||

| Nº. 7 | ||

| Nº. 8 | ||

| Nº. 9 | ||

| Nº. 10 | ||

| Nº. 11 | ||

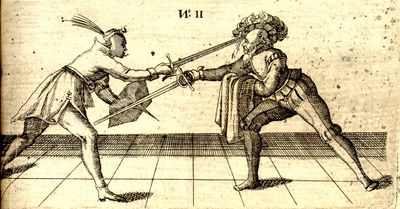

| Nº. 13 |

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

| Nº. 16 | ||

| Nº. 17 | ||

| Nº. 18 | ||

| Nº. 19 | ||

| Nº. 20 |

Images |

Transcription | |

|---|---|---|

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

| Work | Author(s) | Source | License |

|---|---|---|---|

| Images | Gabriel Weyer | Wiktenauer | |

| Translation | Kevin Maurer | Meyer Frei Fechter Guild | |

| Transcription |

Additional Resources

References

- ↑ Steiner, Harald. Das Autorenhonorar: seine Entwicklungsgeschichte vom 17. bis 19. Jahrhundert. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1998. p35. (Translated by Kevin Maurer)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Maurer, Kevin. Sebastian Heussler (1581 - 1645) Buchdrucker, Freifechter and Kreigsmann, from Nürnberg. Meyer Frei Fechter Guild, 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Steiner, Harald. Das Autorenhonorar: seine Entwicklungsgeschichte vom 17. bis 19. Jahrhundert. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1998. p37. (Translated by Kevin Maurer)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Boesch, Hans. "Der Monatsreiter, Fechter und Fahnenschwinger Sebastian Heußler zu Nürnberg". Mitteilungen aus dem Germanischen Nationalmuseum. Nuremberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nürnberg, 1904. p137. (Translated by Kevin Maurer)