|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Salvator Fabris"

| (51 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

| subject = | | subject = | ||

| movement = | | movement = | ||

| − | | notableworks = ''[[Scienza | + | | notableworks = ''[[Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Scienza d'Arme]]'' (1601-06) |

| manuscript(s) = {{collapsible list | | manuscript(s) = {{collapsible list | ||

| [[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040]] (1601) | | [[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040]] (1601) | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

| below = | | below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Salvator Fabris''' (Salvador Fabbri, Salvator Fabriz, Fabrice; 1544-1618) was a 16th – [[century::17th century]] [[nationality::Italian]] knight and [[fencing master]]. He was born in or around Padua, Italy in 1544, and although little is known about his early years, he seems to have studied fencing from a young age and possibly attended the prestigious University of Padua.{{cn}} The French master [[Henry de Sainct Didier]] recounts a meeting with an Italian fencer named "Fabrice" during the course of preparing his treatise (completed in 1573) in which they debated fencing theory, potentially placing Fabris in France in the early 1570s | + | '''Salvator Fabris''' (Salvador Fabbri, Salvator Fabriz, Fabrice; 1544-1618) was a 16th – [[century::17th century]] [[nationality::Italian]] knight and [[fencing master]]. He was born in or around Padua, Italy in 1544, and although little is known about his early years, he seems to have studied fencing from a young age and possibly attended the prestigious University of Padua.{{cn}} The French master [[Henry de Sainct Didier]] recounts a meeting with an Italian fencer named "Fabrice" during the course of preparing his treatise (completed in 1573) in which they debated fencing theory, potentially placing Fabris in France in the early 1570s<ref>[[Henry de Sainct Didier|Didier, Henry de Sainct]]. ''[[Les secrets du premier livre sur l'espée seule (Henry de Sainct Didier)|Les secrets du premier livre sur l'espée seule]]''. Paris, 1573. pp 5-8.</ref>, although that piece of evidence is [https://blog.subcaelo.net/ensis/sainct-didier-fabris/ particularly slim]. In the 1580s, Fabris corresponded with Christian Barnekow, a Danish nobleman with ties to the royal court as well as an alumnus of the university.<ref name="Leoni">[[Salvator Fabris|Fabris, Salvator]] and Leoni, Tom. ''Art of Dueling: Salvator Fabris' Rapier Fencing Treatise of 1606''. Highland Village, TX: [[Chivalry Bookshelf]], 2005. pp XVIII-XIX.</ref> It seems likely that Fabris traveled a great deal during the 1570s and 80s, spending time in France, Germany, Spain, and possibly other regions before returning to teach at his alma mater.{{cn}} |

It is unclear if Fabris himself was of noble birth, but at some point he seems to have earned a knighthood. In fact, he is described in his treatise as ''Supremus Eques'' ("Supreme Knight") of the Order of the Seven Hearts. In Johann Joachim Hynitzsch's introduction to the 1676 edition, he identifies Fabris as a Colonel of the Order.<ref>[[Salvator Fabris|Fabris, Salvator]] and Leoni, Tom. ''Art of Dueling: Salvator Fabris' Rapier Fencing Treatise of 1606''. Highland Village, TX: [[Chivalry Bookshelf]], 2005. p XXIX.</ref> It seems therefore that he was not only a knight of the Order of the Seven Hearts, but rose to a high rank and perhaps even overall leadership. | It is unclear if Fabris himself was of noble birth, but at some point he seems to have earned a knighthood. In fact, he is described in his treatise as ''Supremus Eques'' ("Supreme Knight") of the Order of the Seven Hearts. In Johann Joachim Hynitzsch's introduction to the 1676 edition, he identifies Fabris as a Colonel of the Order.<ref>[[Salvator Fabris|Fabris, Salvator]] and Leoni, Tom. ''Art of Dueling: Salvator Fabris' Rapier Fencing Treatise of 1606''. Highland Village, TX: [[Chivalry Bookshelf]], 2005. p XXIX.</ref> It seems therefore that he was not only a knight of the Order of the Seven Hearts, but rose to a high rank and perhaps even overall leadership. | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

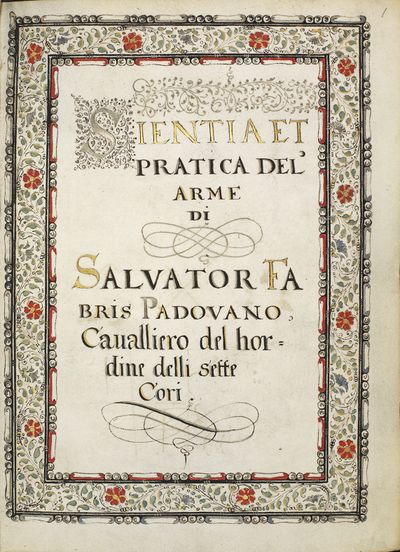

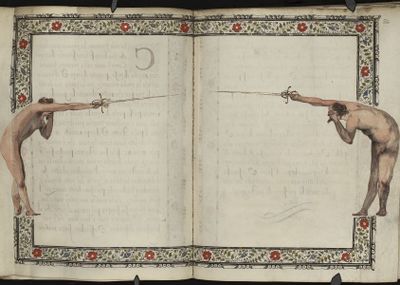

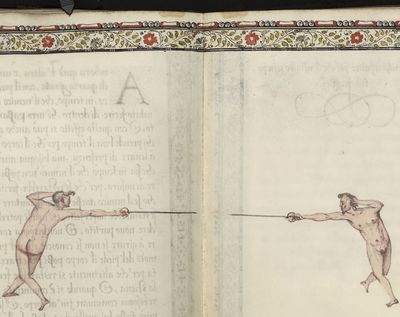

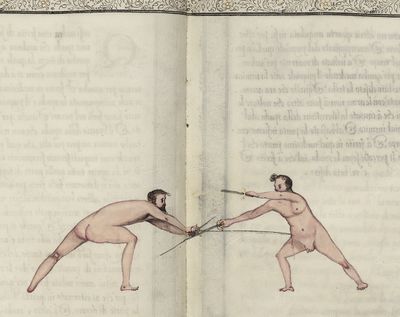

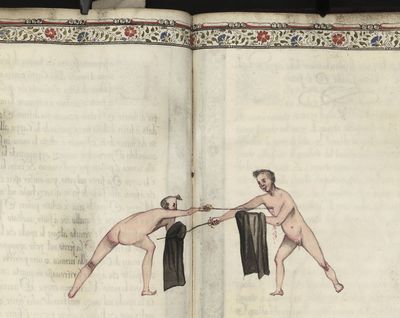

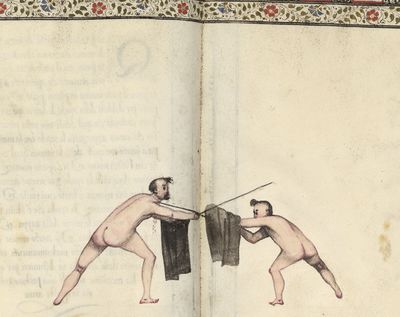

What is certain is that by 1598, Fabris had left his position at the University of Padua and was attached to the court of Johan Frederik, the young duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp. He continued in the duke's service until 1601, and as a parting gift prepared a lavishly-illustrated, three-volume manuscript of his treatise entitled ''Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme'' ([[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|GI.kgl.Saml.1868 4040]]).<ref name="Leoni"/> | What is certain is that by 1598, Fabris had left his position at the University of Padua and was attached to the court of Johan Frederik, the young duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp. He continued in the duke's service until 1601, and as a parting gift prepared a lavishly-illustrated, three-volume manuscript of his treatise entitled ''Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme'' ([[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|GI.kgl.Saml.1868 4040]]).<ref name="Leoni"/> | ||

| − | In 1601, Fabris was hired as chief [[rapier]] instructor to the court of Christianus Ⅳ, King of Denmark and Duke Johan Frederik's cousin. He ultimately served in the royal court for five years; toward the end of his tenure and at the king's insistence, he published his opus under the title '' | + | In 1601, Fabris was hired as chief [[rapier]] instructor to the court of Christianus Ⅳ, King of Denmark and Duke Johan Frederik's cousin. He ultimately served in the royal court for five years; toward the end of his tenure and at the king's insistence, he published his opus under the title ''De lo Schermo, overo Scienza d'Arme'' ("On Defense, or the Science of Arms") or ''Sienza e Pratica d’Arme'' ("Science and Practice of Arms"). Christianus funded this first edition and placed his court artist, [[Jan van Halbeeck]], at Fabris' disposal to illustrate it; it was ultimately published in Copenhagen on 25 September 1606.<ref name="Leoni"/> |

| − | Soon after the text was published, and perhaps feeling his 62 years, Fabris asked to be released from his six-year contract with the king so that he might return home. | + | Soon after the text was published, and perhaps feeling his 62 years, Fabris asked to be released from his six-year contract with the king so that he might return home.{{cn}} In 1608 Fabris was in Paris, France, where [[Joachim Köppe]] recounts meeting him in 1609.<ref>Troyes,Claude I de. https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/UD/FRAN_IR_043571/c1p74y7y7sfv--1o1nfgiiyd2pc [[Minutes et répertoires du notaire Claude I de TROYES, janvier 1603 - décembre 1612 (étude CXXII)]] 20th September, 1608 MC/ET/CXXII/1565, fol. IIII/XX/XI Retrieved 2025-07-28.</ref><ref>[[Joachim Köppe|Joachim Köppe]]. ''[[Newer Discůrs Von der Rittermeszigen und Weitberůmbten Kůnst des Fechtens (Joachim Köppe)|Newer Discůrs Von der Rittermeszigen und Weitberůmbten Kůnst des Fechtens]]''. Magdeburg, 1619. pp. 21-2 Antwort.</ref> Ultimately, he received a position at the University of Padua and there passed his final years. He died of a fever on 11 November 1618 at the age of 74, and the town of Padua declared an official day of mourning in his honor. In 1676, the town of Padua erected a statue of the master in the Chiesa del Santo.{{cn}} |

The importance of Fabris' work can hardly be overstated. Versions of his treatise were reprinted for over a hundred years, and translated into German at least four times as well as French and Latin. He is almost universally praised by later masters and fencing historians, and through the influence of his students and their students (most notably [[Hans Wilhelm Schöffer]]), he became the dominant figure in German fencing throughout the 17th century and into the 18th. | The importance of Fabris' work can hardly be overstated. Versions of his treatise were reprinted for over a hundred years, and translated into German at least four times as well as French and Latin. He is almost universally praised by later masters and fencing historians, and through the influence of his students and their students (most notably [[Hans Wilhelm Schöffer]]), he became the dominant figure in German fencing throughout the 17th century and into the 18th. | ||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

! class="double" | <p>{{rating|C|Draft Translation (from the archetype)}} (ca. 1900)<br/>by [[translator::A. F. Johnson]] (transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]])</p> | ! class="double" | <p>{{rating|C|Draft Translation (from the archetype)}} (ca. 1900)<br/>by [[translator::A. F. Johnson]] (transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]])</p> | ||

! class="double" | <p>[[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|Prototype]] (1601)<br/></p> | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|Prototype]] (1601)<br/></p> | ||

| − | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scienza | + | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Archetype]] (1606){{edit index|Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> |

| − | ! class="double" | <p>German Translation (1677){{edit index|Sienza e pratica | + | ! class="double" | <p>German Translation (1677){{edit index|Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

| [[File:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) Title 1.png|400px|center]] | | [[File:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) Title 1.png|400px|center]] | ||

| <p>[1] '''Fencing''', or '''the Science of Arms''' by Salvator Fabris.</p> | | <p>[1] '''Fencing''', or '''the Science of Arms''' by Salvator Fabris.</p> | ||

| − | | | + | | {{paget|Page:GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040|1r|jpg}} |

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|3|lbl=I}} |

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf|6|lbl=I}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

| <p>[2] </p> | | <p>[2] </p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | | |

| + | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|1|lbl=*|p=1}}<ref>This second title page is an interesting anomaly. It was not printed as part of the main book the way the other title page was, and is instead printed on a single sheet that was glued into the binding. Of 24 copies surveyed by Michael Chidester, 14 had only the first title page, 3 had only the second title page, 16 had both title pages, and 1 had neither (instead, a second copy of page 151 was glued into the beginning of the book to serve as a title page). It's unclear what these anomalies indicate about the process of printing the book.</ref> | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 112: | Line 113: | ||

| <p>[3] </p> | | <p>[3] </p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|5|lbl=V}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 118: | Line 119: | ||

| | | | ||

| [[File:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) Heraldry.jpg|400px|center]] | | [[File:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) Heraldry.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| − | | <p>[4] To His Serene Majesty, the most Powerful Christian IV., King of Denmark, Norway, Gothland and Vandalia, Duke of Schleswig Holstein, Stormarn and Ditmarsch, Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst, &c. | + | | <p>[4] To His Serene Majesty, the most Powerful Christian IV., King of Denmark, Norway, Gothland and Vandalia, Duke of Schleswig Holstein, Stormarn and Ditmarsch, Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst, &c.</p> |

| − | <p>I am confident that all who read this work of mine will recognise that the many benefits received from your Serene Highness are the cause, which has urged and impelled me to publish to the world these my labours. I have wished also to help professors of the science of arms by showing them those instructions and rules, which after long use and continual practice and from observing the errors of others I have found to be good. I hope then that a work based on such principles will find merit, especially as it is under the protection of your Serene Highness - a work as worthy by reason of the excellence of its subject as it is glorious through the approval of your high judgment. To you, therefore, my benefactor, my king and a prince of incomparable valour as much in civil government as in the practice of arms, a true hero of our times, I have dared to dedicate my work; for since its inception is due to you, I am bringing it forth to the sight of men under the same protection. I know moreover how useful to the world and necessary to good men this art is, bringing honour to anyone who practises it aright either in the defence of his prince, his country, the laws, his life or his honour. Will your Serene Majesty therefore deign to receive into your favour not only the work, but the devotion with which, your humble and obedient servant, dedicate it. Meantime I will pray the Divine grace that long life may be granted you for the well-being of your blessed subjects and the good of the world, and that by grace you may obtain salvation in the world to come. | + | <p>I am confident that all who read this work of mine will recognise that the many benefits received from your Serene Highness are the cause, which has urged and impelled me to publish to the world these my labours. I have wished also to help professors of the science of arms by showing them those instructions and rules, which after long use and continual practice and from observing the errors of others I have found to be good. I hope then that a work based on such principles will find merit, especially as it is under the protection of your Serene Highness - a work as worthy by reason of the excellence of its subject as it is glorious through the approval of your high judgment. To you, therefore, my benefactor, my king and a prince of incomparable valour as much in civil government as in the practice of arms, a true hero of our times, I have dared to dedicate my work; for since its inception is due to you, I am bringing it forth to the sight of men under the same protection. I know moreover how useful to the world and necessary to good men this art is, bringing honour to anyone who practises it aright either in the defence of his prince, his country, the laws, his life or his honour. Will your Serene Majesty therefore deign to receive into your favour not only the work, but the devotion with which, your humble and obedient servant, dedicate it. Meantime I will pray the Divine grace that long life may be granted you for the well-being of your blessed subjects and the good of the world, and that by grace you may obtain salvation in the world to come.</p> |

<p>Your Serene Majesty's</p> | <p>Your Serene Majesty's</p> | ||

| Line 128: | Line 129: | ||

<p>'''Salvatore Fabris'''</p> | <p>'''Salvatore Fabris'''</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|7|lbl=VII}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 138: | Line 139: | ||

<p>Marvel not, Reader, if you see a man of the sword, unaccustomed to the schools or the circles of literary men, presuming to write and print books; rather rejoice at seeing the science of arms and the knowledge of the sword reduced to rules and precepts, and like the other arts to a teachable form, wherein the curious and eager men of arms may learn by turning the leaves. More than others should men of arms rejoice, in that men of learning and science have never translated their arts from theory to practice, as now a man of arms has brought his from practice to true theory. To him is owed much greater faith, because he has had a thousand experiences in his own case and in that of others of what he has written. Here then, Reader, is my book on the science of arms, illustrated with plates suitable to each case; to these plates and dumb images, as it were, our words give life; the plates will demonstrate and our words will interpret the effects and principles treated of in the book. We have written in our mother tongue, Italian, dispensing with flowers of rhetoric and elegance of style, not thinking shame to acknowledge our little learning, or, following the example of a very famous captain of our age, to declare that in our youth we could not wield both the sword and the pen. We believe however that we have dealt adequately with what is required in this art and have tried as far as in us lay to avoid obscurity and prolixity, although in so subtle a subject it is difficult to preserve the necessary brevity. We have shunned the use of geometrical terms, although swordsmanship has its foundations more in geometry than in any other science. Simply and as naturally as possible we have tried to bring the art within the capacity of all. For what we have written and demonstrated we require no praise or reward, for it was never our intention to publish it to the world; but if in it there is anything worthy of merit, it should be ascribed to his Serene Majesty our King, through whom we have written this work, and at whose command this book is brought to the light of day. We will not speak of the nobility and excellence of this profession, for it is in itself so glorious and resplendent that it has no need of our words, nor is there any man so ignorant as not to know, that by its[!] kingdoms are defended, religion spread abroad, injustice avenged, peace and the prosperity of nations established. We wish only to say that after acquiring this inestimable knowledge a man should not become puffed up nor use it violently to the detriment of others, but always with moderation and justice in all cases, thinking that the last victory of all rests not in his own hand, but in the just will of God; and may He grant us abundance of his saving grace.</p> | <p>Marvel not, Reader, if you see a man of the sword, unaccustomed to the schools or the circles of literary men, presuming to write and print books; rather rejoice at seeing the science of arms and the knowledge of the sword reduced to rules and precepts, and like the other arts to a teachable form, wherein the curious and eager men of arms may learn by turning the leaves. More than others should men of arms rejoice, in that men of learning and science have never translated their arts from theory to practice, as now a man of arms has brought his from practice to true theory. To him is owed much greater faith, because he has had a thousand experiences in his own case and in that of others of what he has written. Here then, Reader, is my book on the science of arms, illustrated with plates suitable to each case; to these plates and dumb images, as it were, our words give life; the plates will demonstrate and our words will interpret the effects and principles treated of in the book. We have written in our mother tongue, Italian, dispensing with flowers of rhetoric and elegance of style, not thinking shame to acknowledge our little learning, or, following the example of a very famous captain of our age, to declare that in our youth we could not wield both the sword and the pen. We believe however that we have dealt adequately with what is required in this art and have tried as far as in us lay to avoid obscurity and prolixity, although in so subtle a subject it is difficult to preserve the necessary brevity. We have shunned the use of geometrical terms, although swordsmanship has its foundations more in geometry than in any other science. Simply and as naturally as possible we have tried to bring the art within the capacity of all. For what we have written and demonstrated we require no praise or reward, for it was never our intention to publish it to the world; but if in it there is anything worthy of merit, it should be ascribed to his Serene Majesty our King, through whom we have written this work, and at whose command this book is brought to the light of day. We will not speak of the nobility and excellence of this profession, for it is in itself so glorious and resplendent that it has no need of our words, nor is there any man so ignorant as not to know, that by its[!] kingdoms are defended, religion spread abroad, injustice avenged, peace and the prosperity of nations established. We wish only to say that after acquiring this inestimable knowledge a man should not become puffed up nor use it violently to the detriment of others, but always with moderation and justice in all cases, thinking that the last victory of all rests not in his own hand, but in the just will of God; and may He grant us abundance of his saving grace.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|8|lbl=VIII}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 158: | Line 159: | ||

! class="double" | <p>{{rating|C|Draft Translation (from the archetype)}} (ca. 1900)<br/>by [[translator::A. F. Johnson]] (transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]])</p> | ! class="double" | <p>{{rating|C|Draft Translation (from the archetype)}} (ca. 1900)<br/>by [[translator::A. F. Johnson]] (transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]])</p> | ||

! class="double" | <p>[[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|Prototype]] (1601)<br/></p> | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|Prototype]] (1601)<br/></p> | ||

| − | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scienza | + | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Archetype]] (1606){{edit index|Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> |

| − | ! class="double" | <p>German Translation (1677){{edit index|Sienza e pratica | + | ! class="double" | <p>German Translation (1677){{edit index|Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Alex Kiermayer]]</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 168: | Line 169: | ||

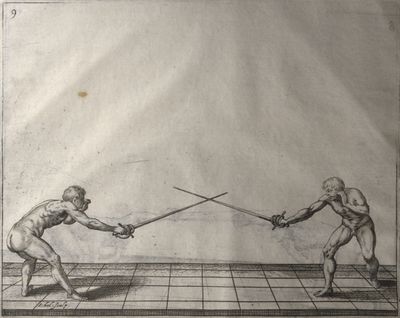

<p>In opening our promised work we shall begin with the sword alone, for on the knowledge of the sword depend the principles of all other arms. Many rules will be given which may serve excellently for the sword accompanied by the dagger or any other arm. He who can use the sword alone well will easily learn to use it in conjunction with other arms. You must know then that the rules of the sword are founded on four guards in which are formed all the positions and counter positions. From them arise the ''times'', ''counter-times'', disengagements, counter-disengagements, double disengagements, half disengagements, and re-engagements; nor in short can anything be done in attack or defence which does not partake of the nature of one of these four guards. They are differently formed, as will be seen in the accompanying plates. These we have introduced in order that you may recognise with what variations of position of the sword, feet and body, they are made. We shall describe the nature of each guard in its place and the plates will show the results which may arise from them. The discourses will be such that you will easily see when to apply the various rules, and how to the best advantage you must approach your adversary in order to come within presence. Though one who understands the art may approach as he pleases, since in whatever position he is he will succeed by his knowledge of distances, weak and strong positions, exposed and unexposed parts. Nevertheless it is certain that one position is better than another, and a man may approach with more security when he parries his arms in the proper manner. When within distance he must proceed in various ways, according to the changes made and the opportunities offered by his adversary, and according to the distance in which he finds himself. The distances are two, and what is good in the one is not so in the other. These distances control the whole attack and defence, as we shall explain. First we shall describe the four principal guards, why they are called, ''prime'', ''seconde'', ''tierce'' and ''quarte'', and the origin of these names. Then we shall treat of the divisions of the sword, then of counterpositions, distances, and some other matters which we consider necessary and useful to the good student of this art.</p> | <p>In opening our promised work we shall begin with the sword alone, for on the knowledge of the sword depend the principles of all other arms. Many rules will be given which may serve excellently for the sword accompanied by the dagger or any other arm. He who can use the sword alone well will easily learn to use it in conjunction with other arms. You must know then that the rules of the sword are founded on four guards in which are formed all the positions and counter positions. From them arise the ''times'', ''counter-times'', disengagements, counter-disengagements, double disengagements, half disengagements, and re-engagements; nor in short can anything be done in attack or defence which does not partake of the nature of one of these four guards. They are differently formed, as will be seen in the accompanying plates. These we have introduced in order that you may recognise with what variations of position of the sword, feet and body, they are made. We shall describe the nature of each guard in its place and the plates will show the results which may arise from them. The discourses will be such that you will easily see when to apply the various rules, and how to the best advantage you must approach your adversary in order to come within presence. Though one who understands the art may approach as he pleases, since in whatever position he is he will succeed by his knowledge of distances, weak and strong positions, exposed and unexposed parts. Nevertheless it is certain that one position is better than another, and a man may approach with more security when he parries his arms in the proper manner. When within distance he must proceed in various ways, according to the changes made and the opportunities offered by his adversary, and according to the distance in which he finds himself. The distances are two, and what is good in the one is not so in the other. These distances control the whole attack and defence, as we shall explain. First we shall describe the four principal guards, why they are called, ''prime'', ''seconde'', ''tierce'' and ''quarte'', and the origin of these names. Then we shall treat of the divisions of the sword, then of counterpositions, distances, and some other matters which we consider necessary and useful to the good student of this art.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/9|1|lbl=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 179: | Line 180: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/9|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/10|1|lbl=2|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 190: | Line 191: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/10|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/11|1|lbl=3|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 196: | Line 197: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

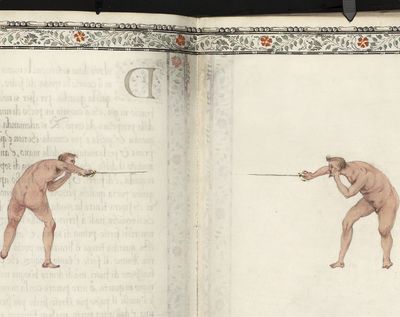

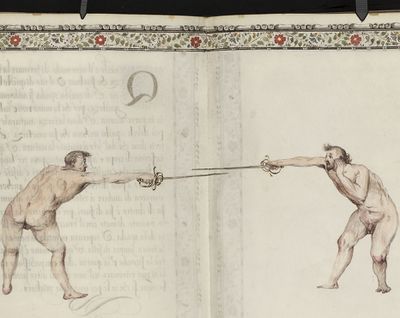

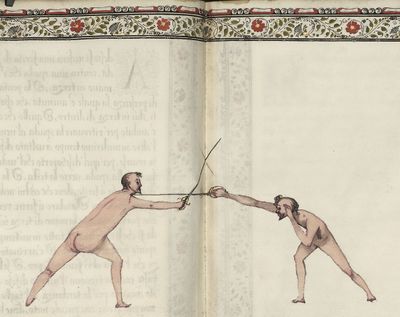

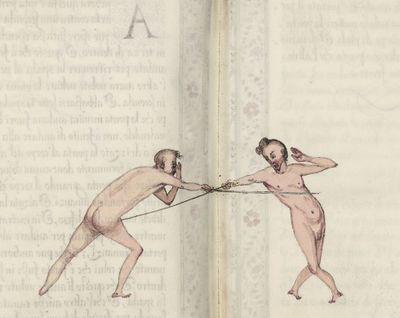

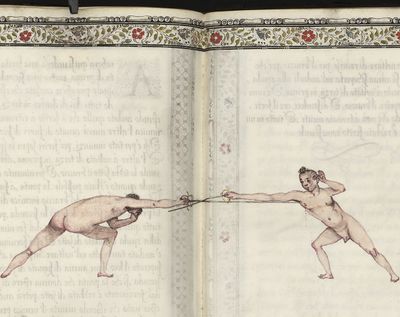

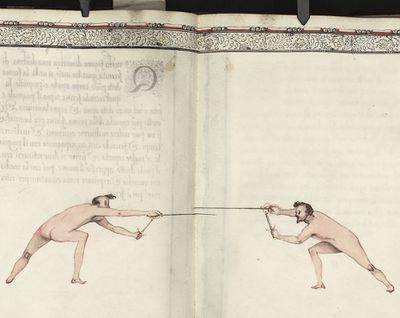

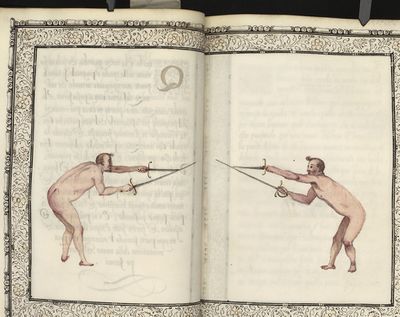

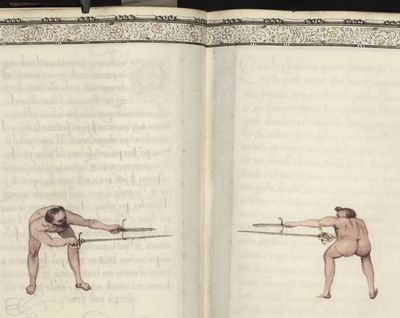

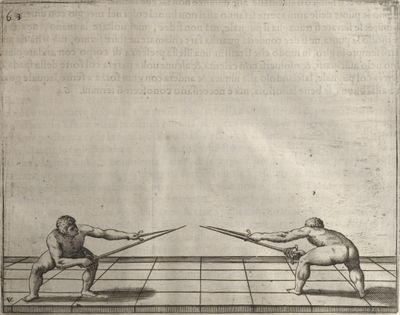

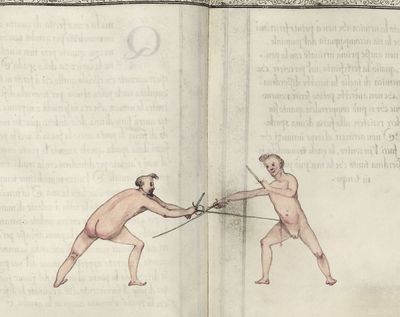

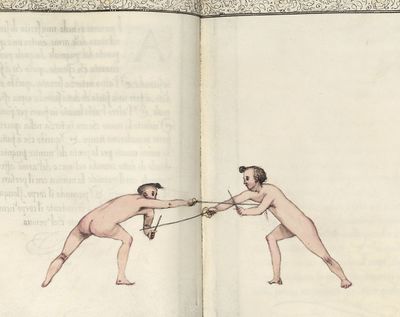

| − | | <p>[4] '''Method of forming the counter-positions,''' showing '''The position of the arms and the body, and when they are to be formed.'''</p> | + | | <p>[4] '''Method of forming the counter-positions,''' showing '''The position of the arms and the body, and when they are to be formed.'''<br/><br/></p> |

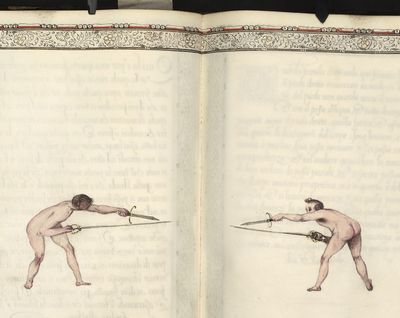

<p>If you wish to form a sound counter-position, the position of the body and arms must be such that without touching the adversary's sword you are defended in the straight line from the point of his sword to your body, so that without making any movement of the body or the sword you are sure that your adversary cannot hit you in that line, but that if he wishes to attack he must move his sword elsewhere, with the result that his ''time'' is so long, that there is every opportunity to parry. But in forming this position care must be taken that your sword is held in such a way as to be stronger than your adversary's, so that it may offer resistance in defence. This rule can be observed against all positions and changes of your adversary, whether accompanied by the dagger or any other defensive weapon, or when you use the sword alone. He who can most subtly maintain this guard will have a great advantage over his adversary.</p> | <p>If you wish to form a sound counter-position, the position of the body and arms must be such that without touching the adversary's sword you are defended in the straight line from the point of his sword to your body, so that without making any movement of the body or the sword you are sure that your adversary cannot hit you in that line, but that if he wishes to attack he must move his sword elsewhere, with the result that his ''time'' is so long, that there is every opportunity to parry. But in forming this position care must be taken that your sword is held in such a way as to be stronger than your adversary's, so that it may offer resistance in defence. This rule can be observed against all positions and changes of your adversary, whether accompanied by the dagger or any other defensive weapon, or when you use the sword alone. He who can most subtly maintain this guard will have a great advantage over his adversary.</p> | ||

| Line 202: | Line 203: | ||

<p>But it often happens that when you form this guard, your adversary forms another against it. Often also this guard is formed so far out of distance that your adversary can wait until you begin to move your foot against him, and at the moment of year advance change his line, so that you are disconcerted by another counter-position. Therefore you must be full of devices and be able in a moment to take up another position of advantage against that of your adversary and make a fresh guard, unless you are so far within distance that you can hit him daring this change, and if in changing he has not retired, since if he had retired you could not hit him even if you had been within distance. You must then take up another counter-position and approach at the same time, to regain the same distance as before. In forming this counter-position you must bear in mind the rule, that the body must be so far distant that the adversary cannot hit, or, if you have approached within distance so that he could hit by advancing his foot, you must form the counter-position without moving the feet. In this way, if the adversary should attempt to hit during the movement, you could parry and hit him, or break ground;<ref>This seems like a mistranslation of ''rompere di misura'' at first blush, but according to Kevin Murakoshi, this is an archaic piece of fencing jargon that was still current in the early 20th century. It means to "break measure" or withdraw. ~ Michael Chidester</ref> in the latter case his sword, would not reach. But if in moving your weapons to take up this advantage, you have moved slowly, you could then abandon your object and hit at the very moment in which your adversary advanced to attack, parrying at the same time. So that if the first movement is made without violence, you can abandon your attempt and make another, as opportunity offers. In short, if you wish to get within distance with some safety, you must first form the counter-position, and if disconcerted by your adversary's counter-position, it will be better to break ground than to approach, until there is an opportunity to get an advantage.</p> | <p>But it often happens that when you form this guard, your adversary forms another against it. Often also this guard is formed so far out of distance that your adversary can wait until you begin to move your foot against him, and at the moment of year advance change his line, so that you are disconcerted by another counter-position. Therefore you must be full of devices and be able in a moment to take up another position of advantage against that of your adversary and make a fresh guard, unless you are so far within distance that you can hit him daring this change, and if in changing he has not retired, since if he had retired you could not hit him even if you had been within distance. You must then take up another counter-position and approach at the same time, to regain the same distance as before. In forming this counter-position you must bear in mind the rule, that the body must be so far distant that the adversary cannot hit, or, if you have approached within distance so that he could hit by advancing his foot, you must form the counter-position without moving the feet. In this way, if the adversary should attempt to hit during the movement, you could parry and hit him, or break ground;<ref>This seems like a mistranslation of ''rompere di misura'' at first blush, but according to Kevin Murakoshi, this is an archaic piece of fencing jargon that was still current in the early 20th century. It means to "break measure" or withdraw. ~ Michael Chidester</ref> in the latter case his sword, would not reach. But if in moving your weapons to take up this advantage, you have moved slowly, you could then abandon your object and hit at the very moment in which your adversary advanced to attack, parrying at the same time. So that if the first movement is made without violence, you can abandon your attempt and make another, as opportunity offers. In short, if you wish to get within distance with some safety, you must first form the counter-position, and if disconcerted by your adversary's counter-position, it will be better to break ground than to approach, until there is an opportunity to get an advantage.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/11|2|lbl=-}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 208: | Line 209: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

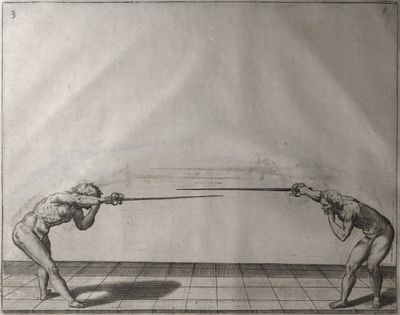

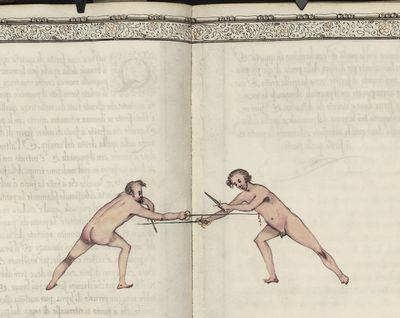

| − | | <p>[5] '''Explanation of the two distances, wide and close, and how to acquire the one or the other with least danger.'''</p> | + | | <p>[5] '''Explanation of the two distances, wide and close, and how to acquire the one or the other with least danger.'''<br/><br/></p> |

<p>You are within wide distance when by advancing the rear foot to the front you can make a hit. After forming the counter-position a little out of distance, you must begin to advance the foot in order to get within the required distance. But you must be on your guard, lest your adversary, being steady, at the moment when you move your foot to advance it, should advance his too and hit at the same time. Therefore, you must move it very carefully, remembering that your adversary may effect something during the movement. After forming the counter-position you must endeavour to throw him into disorder, or at least make some feint in order to have an opportunity to hit. Thus prepared for what may happen you are more guarded and can better resist attack. When you are within wide distance and your adversary makes some movement of his foot, provided he does not break ground, you can hit him in the nearest exposed part, even if he has not moved his weapons. This could not be done if he moved his weapons and stood firm on his feet, the reason being that a movement of the foot is slower than that of the weapons, and therefore he could parry before your sword arrived, while he remained steady; if there were no other way he could protect himself by breaking ground, so that your sword could not reach. Being thrown into disorder you would then be in danger of being hit before you had recovered. Therefore whenever he gives an opportunity without moving his feet, it would be better to approach within close distance in that time. In that distance you can reach with the sword by merely bending the body, without moving the feet, and the adversary is forced to retire to get out of such danger. If he does not move you could hit him even though he retained the advantage of the counter-position. If your adversary does not move, you can sometimes make a hit by judging the distance from the point of your sword to your adversary's body and the distance from the ''forte'' of his sword. If you consider both how much you must advance the point and how far you must move it from the adversary's ''forte'', and understand that the time required for him to parry is the same as for you to hit, the sword will arrive before he has parried by the advantage of having moved first. If you see that his body is little exposed, as may happen, since one guard covers more than another, you can then attempt to hit in the exposed part, and as he moves to the defence change your line and hit in the second exposed part.</p> | <p>You are within wide distance when by advancing the rear foot to the front you can make a hit. After forming the counter-position a little out of distance, you must begin to advance the foot in order to get within the required distance. But you must be on your guard, lest your adversary, being steady, at the moment when you move your foot to advance it, should advance his too and hit at the same time. Therefore, you must move it very carefully, remembering that your adversary may effect something during the movement. After forming the counter-position you must endeavour to throw him into disorder, or at least make some feint in order to have an opportunity to hit. Thus prepared for what may happen you are more guarded and can better resist attack. When you are within wide distance and your adversary makes some movement of his foot, provided he does not break ground, you can hit him in the nearest exposed part, even if he has not moved his weapons. This could not be done if he moved his weapons and stood firm on his feet, the reason being that a movement of the foot is slower than that of the weapons, and therefore he could parry before your sword arrived, while he remained steady; if there were no other way he could protect himself by breaking ground, so that your sword could not reach. Being thrown into disorder you would then be in danger of being hit before you had recovered. Therefore whenever he gives an opportunity without moving his feet, it would be better to approach within close distance in that time. In that distance you can reach with the sword by merely bending the body, without moving the feet, and the adversary is forced to retire to get out of such danger. If he does not move you could hit him even though he retained the advantage of the counter-position. If your adversary does not move, you can sometimes make a hit by judging the distance from the point of your sword to your adversary's body and the distance from the ''forte'' of his sword. If you consider both how much you must advance the point and how far you must move it from the adversary's ''forte'', and understand that the time required for him to parry is the same as for you to hit, the sword will arrive before he has parried by the advantage of having moved first. If you see that his body is little exposed, as may happen, since one guard covers more than another, you can then attempt to hit in the exposed part, and as he moves to the defence change your line and hit in the second exposed part.</p> | ||

| Line 217: | Line 218: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|12|lbl=4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/13|1|lbl=5|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 230: | Line 231: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/13|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|14|lbl=6|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/15|1|lbl=7|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 245: | Line 246: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/15|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|16|lbl=8|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/17|1|lbl=9|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 264: | Line 265: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/17|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|18|lbl=10|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/19|1|lbl=11|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 277: | Line 278: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/19|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|20|lbl=12|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/21|1|lbl=13|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 294: | Line 295: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/21|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|22|lbl=14|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 304: | Line 305: | ||

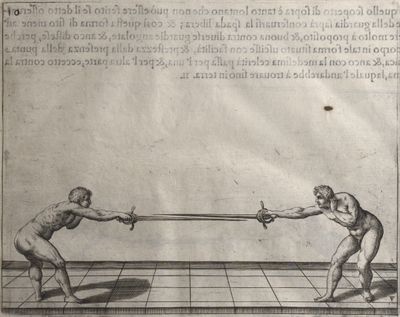

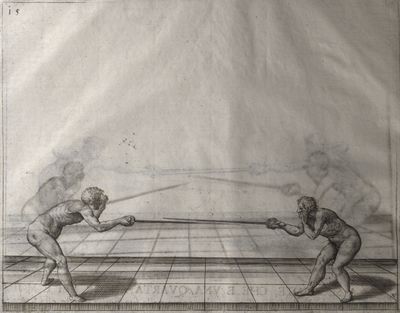

<p>When your adversary attempts to engage your sword or to beat it, and you change from one line to another, before he can beat or engage, you are said to make a disengagement in ''time''. If, while your adversary is disengaging, you follow his movement, which he has begun in order to get the superiority, and let your sword go after his, so that you engage him in the same line as before, that is called a counter-disengagement. If you have disengaged and your adversary has also disengaged and you then deceive his engagement, that is a double disengagement. If, without completing the change from one line to another, you leave your sword under the adversary's, you make a half disengagement. If you disengage and, when your adversary moves to engage or to make a hit, you engage again where you were before, you are said to re-engage - - -. To make a successful disengagement you must bend forward — so that, when the disengagement is completed, the lunge is completed, if you wish to hit, otherwise you will not be in time. If you follow this principle, your adversary will not be able to parry, if you have taken the ''time'', though he may counter-disengage, if that was his intention in seeking to engage. If he had meant simply to get the superiority or to beat he would certainly be hit. If in seeking to engage your sword, the adversary remains steady, then you must disengage in order to free your sword. This gives him an opportunity for a counter-disengagement, for he has moved at the same time as you disengaged. Then to protect yourself you must make a double disengagement and thrust in the same ''time'', in which he has meant to hit you with a counter-disengagement. Some remain steady in seeking to engage in order to make the adversary disengage and so hit him in the straight line, before he has completed the disengagement. In such a case if the adversary, who has begun to disengage, returns to the same line as before, carrying his ''forte'' to your ''faible'' and thrusting on to the body, he will save himself and certainly hit at the moment you meant to hit. The half disengagement is used when you are in doubt that the adversary may pass to your body, before you have completed,[!] the disengagement, since your point would be out of presence and could not hit. Therefore you make a half disengagement to save time, and remain below the adversary's sword in order to hit, removing your body out of presence, as we shall explain in its place. Such a half disengagement is not always used in the first passes, but more often in the second and third movements, as the distance is shortened. The effects produced by these disengagements will be seen in the plates.</p> | <p>When your adversary attempts to engage your sword or to beat it, and you change from one line to another, before he can beat or engage, you are said to make a disengagement in ''time''. If, while your adversary is disengaging, you follow his movement, which he has begun in order to get the superiority, and let your sword go after his, so that you engage him in the same line as before, that is called a counter-disengagement. If you have disengaged and your adversary has also disengaged and you then deceive his engagement, that is a double disengagement. If, without completing the change from one line to another, you leave your sword under the adversary's, you make a half disengagement. If you disengage and, when your adversary moves to engage or to make a hit, you engage again where you were before, you are said to re-engage - - -. To make a successful disengagement you must bend forward — so that, when the disengagement is completed, the lunge is completed, if you wish to hit, otherwise you will not be in time. If you follow this principle, your adversary will not be able to parry, if you have taken the ''time'', though he may counter-disengage, if that was his intention in seeking to engage. If he had meant simply to get the superiority or to beat he would certainly be hit. If in seeking to engage your sword, the adversary remains steady, then you must disengage in order to free your sword. This gives him an opportunity for a counter-disengagement, for he has moved at the same time as you disengaged. Then to protect yourself you must make a double disengagement and thrust in the same ''time'', in which he has meant to hit you with a counter-disengagement. Some remain steady in seeking to engage in order to make the adversary disengage and so hit him in the straight line, before he has completed the disengagement. In such a case if the adversary, who has begun to disengage, returns to the same line as before, carrying his ''forte'' to your ''faible'' and thrusting on to the body, he will save himself and certainly hit at the moment you meant to hit. The half disengagement is used when you are in doubt that the adversary may pass to your body, before you have completed,[!] the disengagement, since your point would be out of presence and could not hit. Therefore you make a half disengagement to save time, and remain below the adversary's sword in order to hit, removing your body out of presence, as we shall explain in its place. Such a half disengagement is not always used in the first passes, but more often in the second and third movements, as the distance is shortened. The effects produced by these disengagements will be seen in the plates.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|23|lbl=15}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 327: | Line 328: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|24|lbl=16|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/25|1|lbl=17|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 350: | Line 351: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/25|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|26|lbl=18|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|27|lbl=19|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 367: | Line 368: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|28|lbl=20|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|29|lbl=21|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/30|1|lbl=22|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 384: | Line 385: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/30|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/31|1|lbl=23|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 405: | Line 406: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/31|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|32|lbl=24|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/33|1|lbl=25|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| Line 412: | Line 413: | ||

| | | | ||

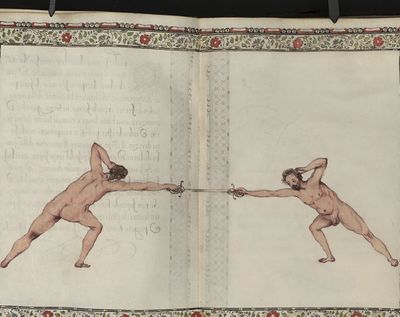

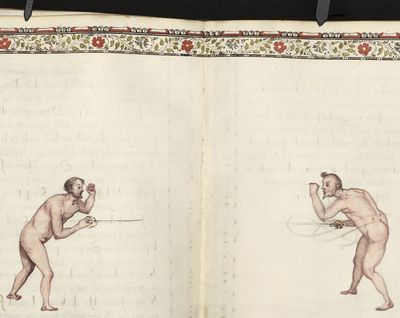

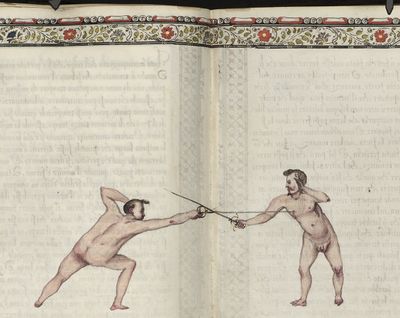

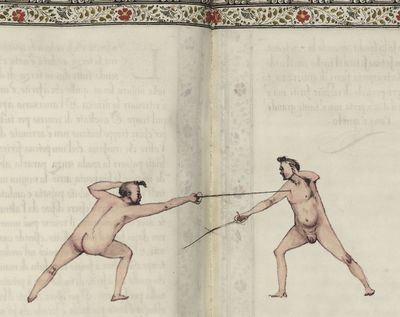

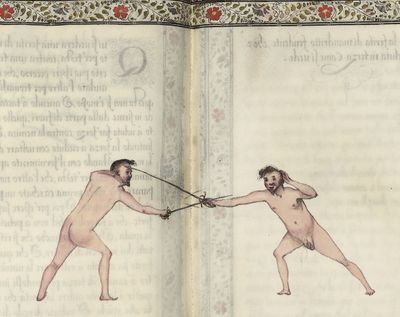

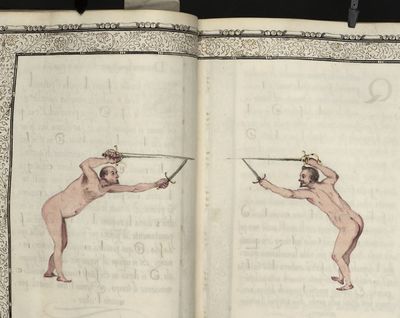

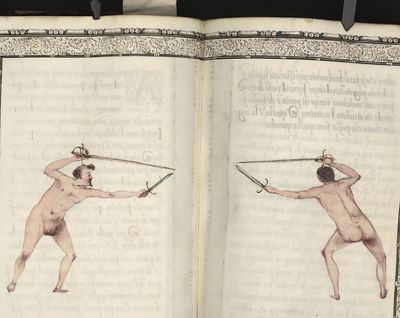

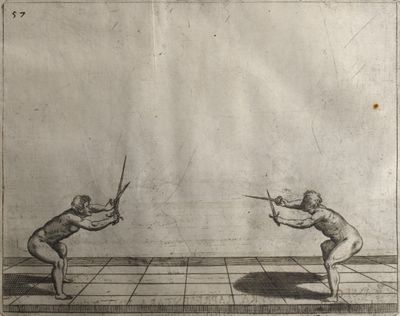

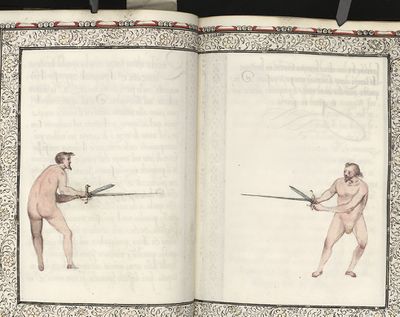

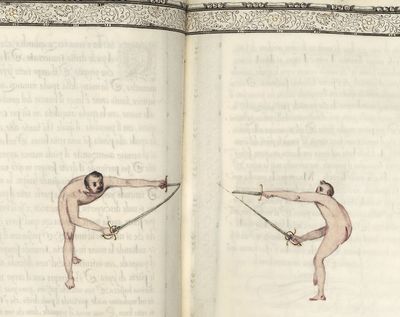

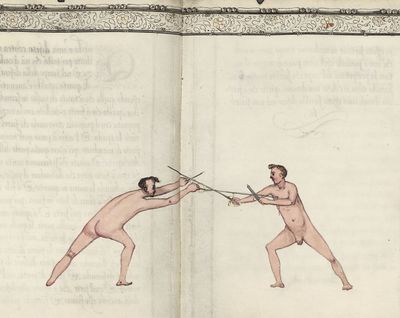

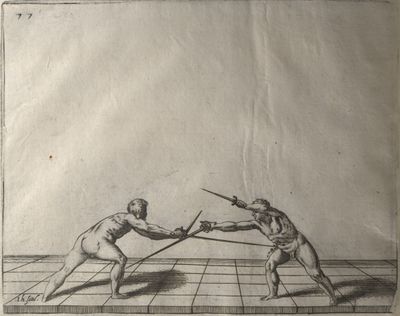

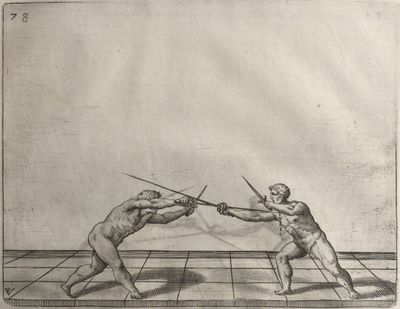

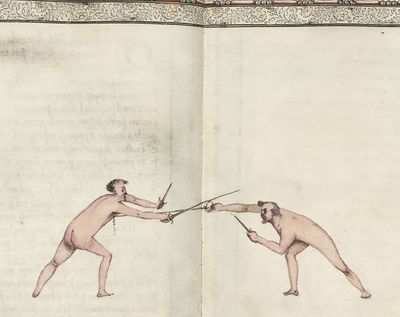

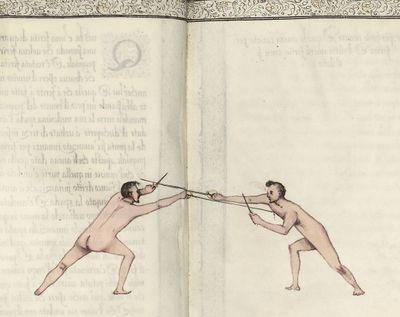

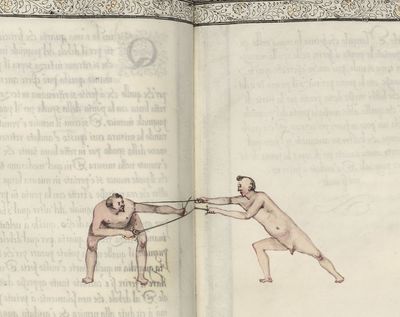

| <p>[17] '''General discourse on the guards.'''</p> | | <p>[17] '''General discourse on the guards.'''</p> | ||

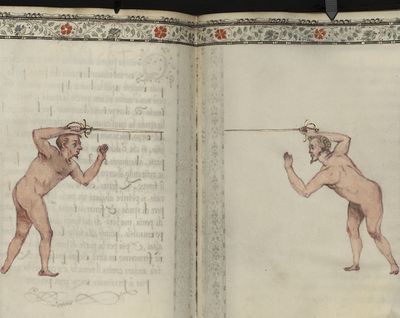

| + | |||

| + | <p><br/></p> | ||

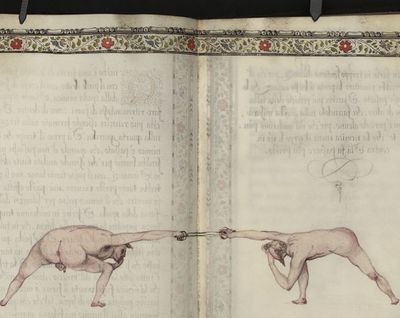

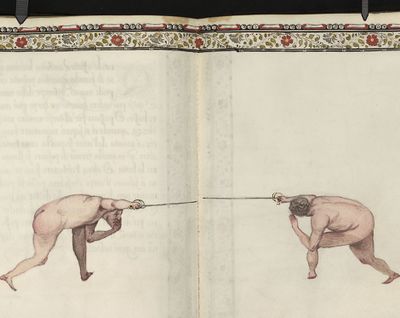

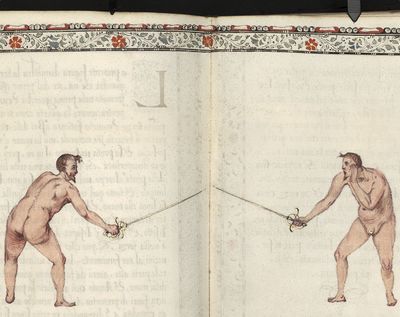

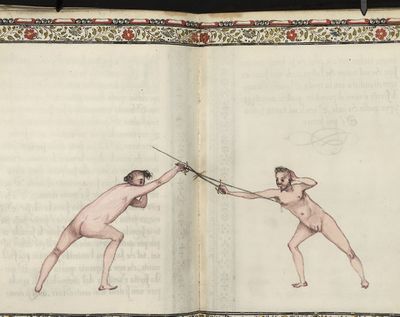

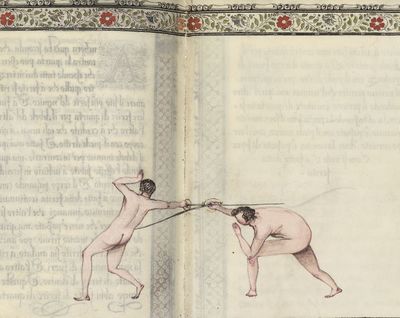

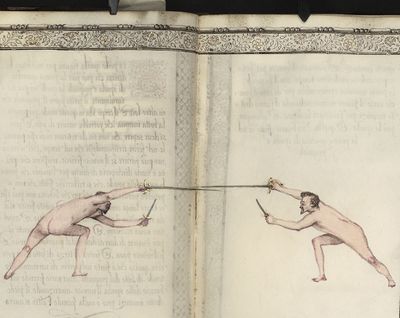

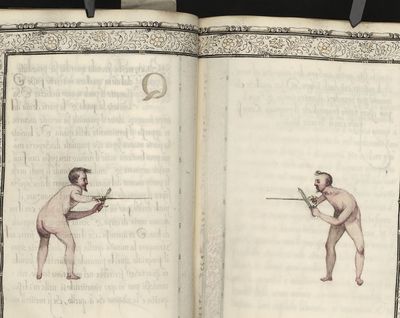

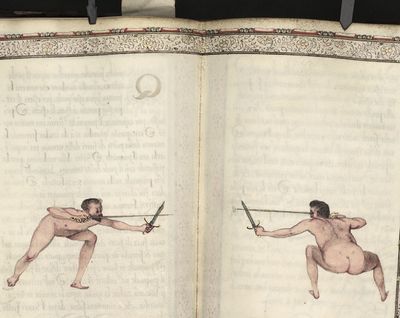

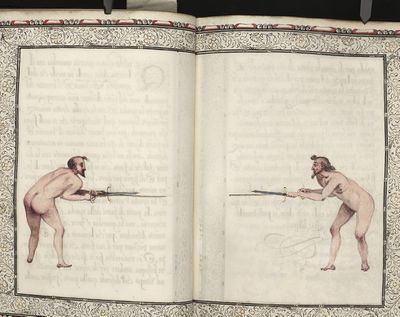

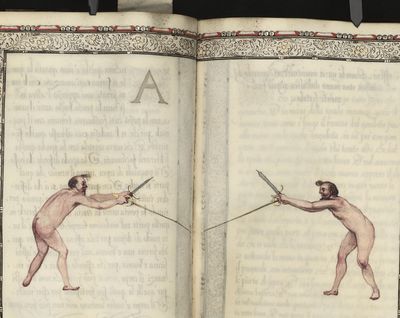

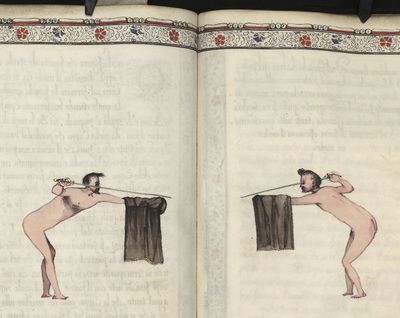

<p>We have now reached the point when we must treat of the formation of the principal guards, and movements and the results obtained in arms. We must first warn the reader not to wonder if he sees two figures illustrating one result. This is done to represent the right and the left side of the body. On the other hand we have thought it unimportant and idle to treat of many other guards of which some authors have written; for instance a guard with the dagger extended and the sword thrown behind, now on one foot and now on the other, now high, now low, which seems to us to defend the rear rather than the front. Others with the sword alone have kept it so far back and low, that the point was near the point of their feet, and also they held the sword across the legs and with the point almost on the ground, and all this that the sword might not be engaged. Sometimes on guard they take the blade in the left hand to give it strength, in order to beat the adversary's sword and hit. All these things we have omitted as inappropriate and, more often harmful than useful, and in any case tedious to the reader. Perhaps it had been better to have passed them in silence, but some might have thought we had not seen or considered such things; - therefore we have made some mention of them, as of the practice of throwing the sword at the adversary, when fighting with the sword alone; some think this an essential movement, but we deem it of little value; it may succeed against those who leave the sword free or hold their own too stiff, but against those who engage their adversary's sword and can disengage, it effects nothing, rather he who adopts this method will always be beaten. Therefore we shall not treat of it further in the present work, but shall try to give such discourses, as when well considered can bring you such counsel and judgment, that, when you see your adversary approaching sword in hand in whatever manner, you will recognise the principles he is following as well as he himself. These results are illustrated by plates, from which you may expect great benefit. To these are added the discourses not only as an explanation of the results, but also in order that you may discover the intention of one who uses them and so anticipate your adversary's thoughts and prepare yourself before the result follows.</p> | <p>We have now reached the point when we must treat of the formation of the principal guards, and movements and the results obtained in arms. We must first warn the reader not to wonder if he sees two figures illustrating one result. This is done to represent the right and the left side of the body. On the other hand we have thought it unimportant and idle to treat of many other guards of which some authors have written; for instance a guard with the dagger extended and the sword thrown behind, now on one foot and now on the other, now high, now low, which seems to us to defend the rear rather than the front. Others with the sword alone have kept it so far back and low, that the point was near the point of their feet, and also they held the sword across the legs and with the point almost on the ground, and all this that the sword might not be engaged. Sometimes on guard they take the blade in the left hand to give it strength, in order to beat the adversary's sword and hit. All these things we have omitted as inappropriate and, more often harmful than useful, and in any case tedious to the reader. Perhaps it had been better to have passed them in silence, but some might have thought we had not seen or considered such things; - therefore we have made some mention of them, as of the practice of throwing the sword at the adversary, when fighting with the sword alone; some think this an essential movement, but we deem it of little value; it may succeed against those who leave the sword free or hold their own too stiff, but against those who engage their adversary's sword and can disengage, it effects nothing, rather he who adopts this method will always be beaten. Therefore we shall not treat of it further in the present work, but shall try to give such discourses, as when well considered can bring you such counsel and judgment, that, when you see your adversary approaching sword in hand in whatever manner, you will recognise the principles he is following as well as he himself. These results are illustrated by plates, from which you may expect great benefit. To these are added the discourses not only as an explanation of the results, but also in order that you may discover the intention of one who uses them and so anticipate your adversary's thoughts and prepare yourself before the result follows.</p> | ||

| Line 418: | Line 421: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/33|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/34|1|lbl=26|p=1}} |

| − | | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/76|2|lbl=59}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/77|3|lbl=60}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/77|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/78|4|lbl=61|p=1}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/78|5|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/78|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 436: | Line 439: | ||

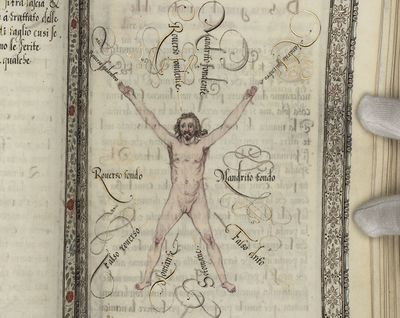

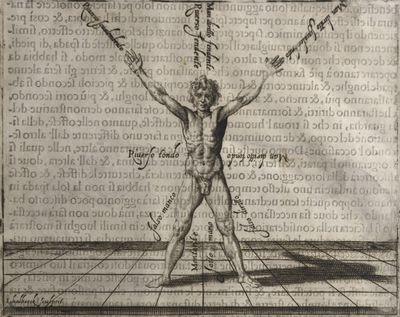

<p>This plate shows the nature of all the cuts, which a hand can make. The names are placed against them so that you may see where each of them naturally hits, although they may hit higher or lower according to whether they are made with the hand or the arm. At least their path is seen, and from a knowledge of that follows a knowledge of the second point, what sort of defence can he made in order to parry them and hit at the same time. Therefore the names on the plate are placed not in the part from which the cuts are delivered, but where they hit; for the cut of ''mandiritto'' is delivered from the right and hits the adversary's left shoulder, and the cut of ''riverso'' is delivered from the left and hits somewhere on the right side, as may be seen. Whoever examines and ponders on these cuts, will easily discover the principles of proceeding against each one of them, bearing in mind that even if all the cuts are made by the same arm they may not have the same strength, and therefore against the stronger it is necessary to find a stronger defence in order to resist and hit. Although it might appear that we should here treat of the differences in the cuts, still we think we have treated of them sufficiently in speaking of the defence and the attack, and of thrusting and cutting. It is our intention to base our instruction, not on these, but on more subtle and profitable principles.</p> | <p>This plate shows the nature of all the cuts, which a hand can make. The names are placed against them so that you may see where each of them naturally hits, although they may hit higher or lower according to whether they are made with the hand or the arm. At least their path is seen, and from a knowledge of that follows a knowledge of the second point, what sort of defence can he made in order to parry them and hit at the same time. Therefore the names on the plate are placed not in the part from which the cuts are delivered, but where they hit; for the cut of ''mandiritto'' is delivered from the right and hits the adversary's left shoulder, and the cut of ''riverso'' is delivered from the left and hits somewhere on the right side, as may be seen. Whoever examines and ponders on these cuts, will easily discover the principles of proceeding against each one of them, bearing in mind that even if all the cuts are made by the same arm they may not have the same strength, and therefore against the stronger it is necessary to find a stronger defence in order to resist and hit. Although it might appear that we should here treat of the differences in the cuts, still we think we have treated of them sufficiently in speaking of the defence and the attack, and of thrusting and cutting. It is our intention to base our instruction, not on these, but on more subtle and profitable principles.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/34|2|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/35|1|lbl=27}} |

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/79|3|lbl=62|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/80|4|lbl=63|p=1}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/80|5|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 451: | Line 454: | ||

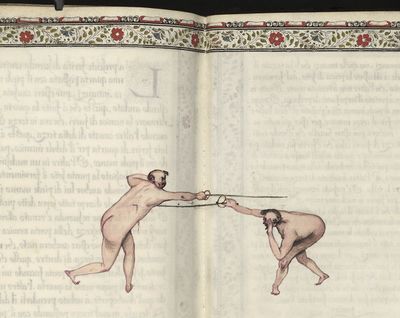

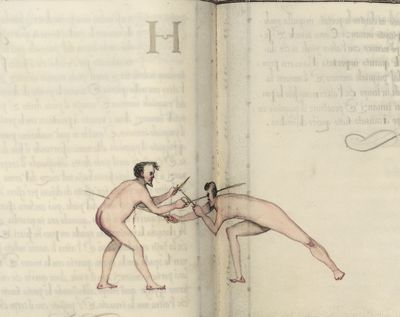

<p>This plate (the second in order) shows the position into which the hand goes in drawing the sword from the scabbard, wherefore its name of the guard in ''prime''. It cannot be held to be very secure, since the sword is too much withdrawn and the body entirely exposed owing to the height of the sword, which brings the ''forte'' very far from the body, so that it cannot defend the exposed part below in time. In this case you would have to defend with the hand, unless you broke ground, otherwise you would be hit before parrying. If you wished to hit after the parry you could lower the point a little, abandoning his sword, and make a cut, or a rush, but as this would be a hit in two ''times'' it would not be very successful. As to the head it is sufficiently defended by the guard, and more on the outside than the inside. But we shall form another guard which is safer, with which you can await your adversary or advance. With the present one an advance would be very dangerous; therefore this position of the body and the sword should be used on breaking ground rather than at any other time.</p> | <p>This plate (the second in order) shows the position into which the hand goes in drawing the sword from the scabbard, wherefore its name of the guard in ''prime''. It cannot be held to be very secure, since the sword is too much withdrawn and the body entirely exposed owing to the height of the sword, which brings the ''forte'' very far from the body, so that it cannot defend the exposed part below in time. In this case you would have to defend with the hand, unless you broke ground, otherwise you would be hit before parrying. If you wished to hit after the parry you could lower the point a little, abandoning his sword, and make a cut, or a rush, but as this would be a hit in two ''times'' it would not be very successful. As to the head it is sufficiently defended by the guard, and more on the outside than the inside. But we shall form another guard which is safer, with which you can await your adversary or advance. With the present one an advance would be very dangerous; therefore this position of the body and the sword should be used on breaking ground rather than at any other time.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/35|2|lbl=-}} |

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/80|6|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/81|4|lbl=64|p=1}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/81|5|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/81|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 466: | Line 469: | ||

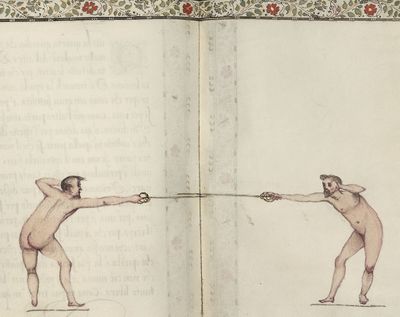

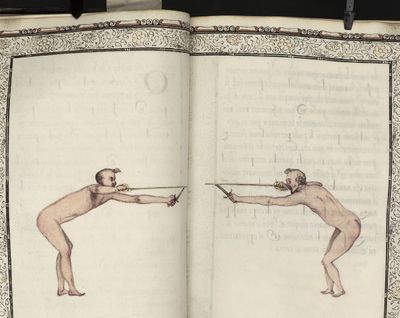

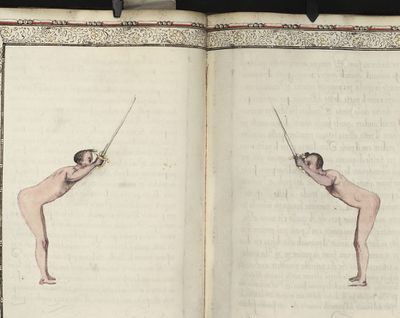

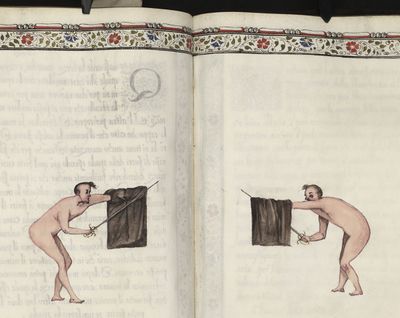

<p>If you wish to form a sound guard in ''prime'' the position of the body and sword must be as shown in the plate, the feet close together, body bent, arm extended, with the sword in front with the point as straight as possible; for the point will naturally incline towards the ground. Thus your adversary cannot thrust over the sword; this part being the weaker must be better defended. Moreover you must keep the feet together and the body bent, so that the lower parts may be so far withdrawn that the adversary cannot reach them without penetrating with his head half the sword's length. Your sword will have to defend only the head and part of the chest, which it can easily do, as the ''forte'' is already so far advanced that the adversary's sword can never extend so far as not to be always nearer the forte than the body. This guard is excellent against cuts, for with it you can defend and attack without turning the hand. It would be as good as any other guard in fencing if it were not so laborious for the arm, that you cannot long endure this position. With this guard you can advance to engage and harass your adversary's sword without changing guard, always approaching so as to hit on the outside over the sword, or below, in case your adversary disengages, by lowering your body still further, moving the feet apart, and keeping the arm in the same guard; as soon as you have hit, bring the feet together again and try to engage his sword above, even though his sword is on the inside, and push it out. This you can easily do, for your adversary cannot resist, as in this line your guard is strongest.</p> | <p>If you wish to form a sound guard in ''prime'' the position of the body and sword must be as shown in the plate, the feet close together, body bent, arm extended, with the sword in front with the point as straight as possible; for the point will naturally incline towards the ground. Thus your adversary cannot thrust over the sword; this part being the weaker must be better defended. Moreover you must keep the feet together and the body bent, so that the lower parts may be so far withdrawn that the adversary cannot reach them without penetrating with his head half the sword's length. Your sword will have to defend only the head and part of the chest, which it can easily do, as the ''forte'' is already so far advanced that the adversary's sword can never extend so far as not to be always nearer the forte than the body. This guard is excellent against cuts, for with it you can defend and attack without turning the hand. It would be as good as any other guard in fencing if it were not so laborious for the arm, that you cannot long endure this position. With this guard you can advance to engage and harass your adversary's sword without changing guard, always approaching so as to hit on the outside over the sword, or below, in case your adversary disengages, by lowering your body still further, moving the feet apart, and keeping the arm in the same guard; as soon as you have hit, bring the feet together again and try to engage his sword above, even though his sword is on the inside, and push it out. This you can easily do, for your adversary cannot resist, as in this line your guard is strongest.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|36|lbl=28}} |

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/82|2|lbl=65|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/83|5|lbl=66|p=1}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/83|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 479: | Line 482: | ||

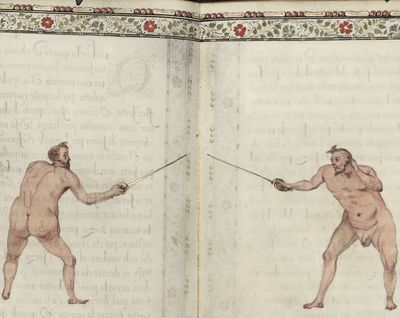

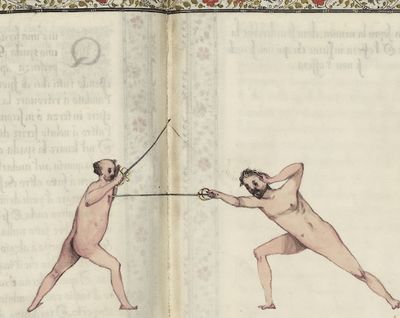

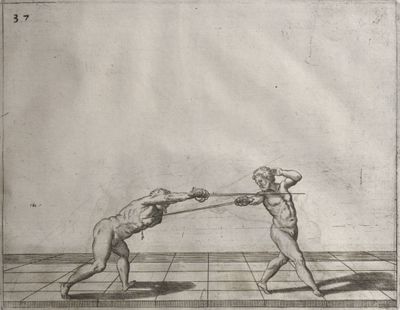

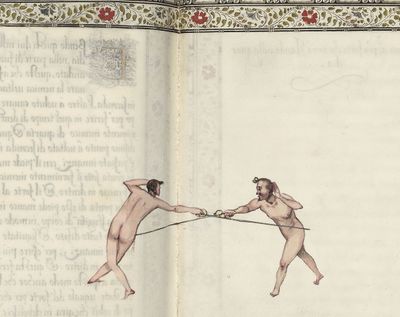

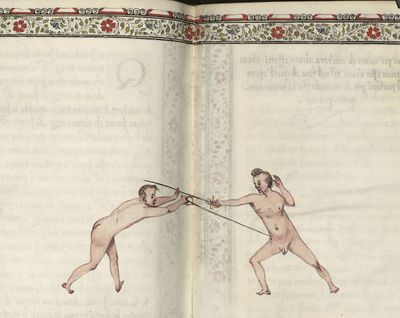

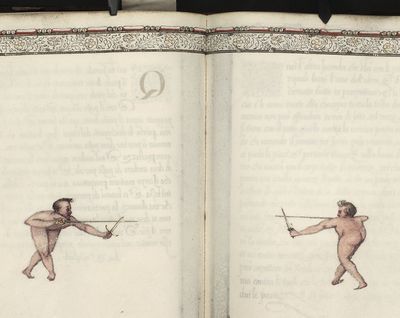

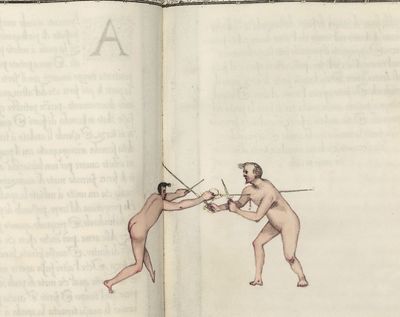

<p>From the position of the hand in drawing the sword from the scabbard arises this guard, with the arm somewhat lowered and turned downwards. This has caused a slight change in the front of the body. It is called the guard in ''seconde'' because it is the first movement which the hand can make in changing from the guard in ''prime.'' It is easier than the guard in ''prime'', as the arm is not so strained; owing to the change of the position of the hand the weak part has changed. In the first it was above, now it is on the outside. It is true that as the feat are rather far apart the leg is in some danger towards the knee; still if you can keep your sword free, your adversary will only with difficulty hit you so low before he is himself hit above. Although in this guard the arm is somewhat withdrawn, the ''forte'' is so far forward that it can parry excellently both on the outside and the inside; but the hand must be turned in ''quarte'', or you must parry with the hand. If the feet are kept closer together this guard will be safer on both sides. But we shall form another guard like the first but much better.</p> | <p>From the position of the hand in drawing the sword from the scabbard arises this guard, with the arm somewhat lowered and turned downwards. This has caused a slight change in the front of the body. It is called the guard in ''seconde'' because it is the first movement which the hand can make in changing from the guard in ''prime.'' It is easier than the guard in ''prime'', as the arm is not so strained; owing to the change of the position of the hand the weak part has changed. In the first it was above, now it is on the outside. It is true that as the feat are rather far apart the leg is in some danger towards the knee; still if you can keep your sword free, your adversary will only with difficulty hit you so low before he is himself hit above. Although in this guard the arm is somewhat withdrawn, the ''forte'' is so far forward that it can parry excellently both on the outside and the inside; but the hand must be turned in ''quarte'', or you must parry with the hand. If the feet are kept closer together this guard will be safer on both sides. But we shall form another guard like the first but much better.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|37|lbl=29}} |

| − | | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/83|7|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/83|8|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/84|3|lbl=67|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 491: | Line 494: | ||

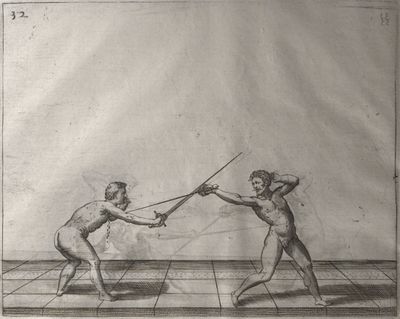

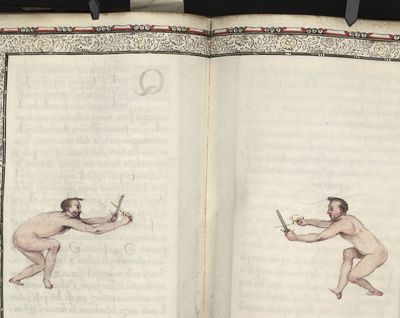

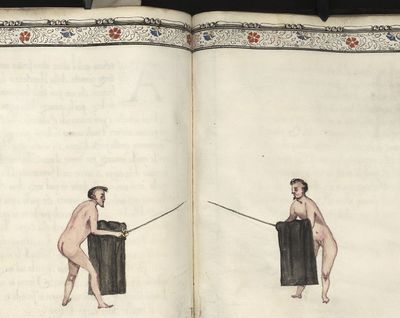

<p>This is the position in which you should form the guard in ''seconde'' for greater safety. Although it is fatiguing, it is less so than the guard in ''prime,'' for the arm is somewhat lower. Its weakest part is on the outside, therefore you must hold the point so straight that your adversary cannot come in there. Although it is the most covered part, only a little of the head showing above the right arm, your adversary might come in there, put you to the necessity of defending the spot, and then proceed to hit below. If then he should attack on the outside you should disengage, without advancing, if you have not been able to hit whilst he was moving on the outside. The lower parts are still more secure than with the guard in ''prime''. The defences are somewhat different, for you must defend the ''mandiritto tondo'' by turning into ''quarte'', as also the ''sottomano''. All the others are parried with the guard <sup>of</sup> ''seconde'' except some thrusts on the inside, which are likewise parried with a turn to ''quarte''. You will do well with this guard, as your sword is advanced and straight. If you understand its principles you will find it excellent and advantageous; it leaves little uncovered for the adversary to hit, and the body is so far withdrawn that he cannot reach it without first subjecting your sword, which is difficult as the disengage is with this guard made with little movement and quickly. But as we have said above it is somewhat laborious to maintain for long.</p> | <p>This is the position in which you should form the guard in ''seconde'' for greater safety. Although it is fatiguing, it is less so than the guard in ''prime,'' for the arm is somewhat lower. Its weakest part is on the outside, therefore you must hold the point so straight that your adversary cannot come in there. Although it is the most covered part, only a little of the head showing above the right arm, your adversary might come in there, put you to the necessity of defending the spot, and then proceed to hit below. If then he should attack on the outside you should disengage, without advancing, if you have not been able to hit whilst he was moving on the outside. The lower parts are still more secure than with the guard in ''prime''. The defences are somewhat different, for you must defend the ''mandiritto tondo'' by turning into ''quarte'', as also the ''sottomano''. All the others are parried with the guard <sup>of</sup> ''seconde'' except some thrusts on the inside, which are likewise parried with a turn to ''quarte''. You will do well with this guard, as your sword is advanced and straight. If you understand its principles you will find it excellent and advantageous; it leaves little uncovered for the adversary to hit, and the body is so far withdrawn that he cannot reach it without first subjecting your sword, which is difficult as the disengage is with this guard made with little movement and quickly. But as we have said above it is somewhat laborious to maintain for long.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|38|lbl=30}} |

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/84|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/85|4|lbl=68|p=1}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/85|5|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/85|6|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/86|3|lbl=69|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 509: | Line 512: | ||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza | + | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|39|lbl=31|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/40|1|lbl=32|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/86|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/87|6|lbl=70|p=1}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/87|7|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/87|8|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/87|9|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/87|10|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/88|3|lbl=71|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

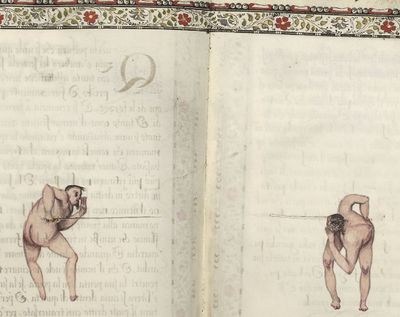

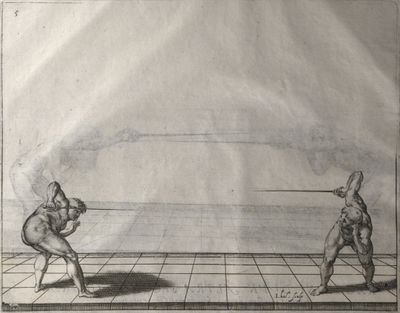

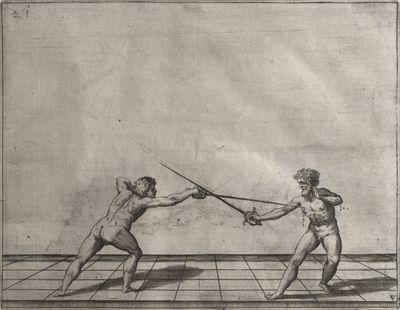

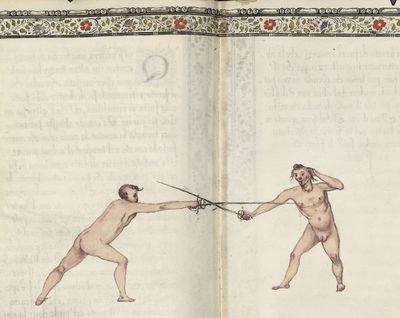

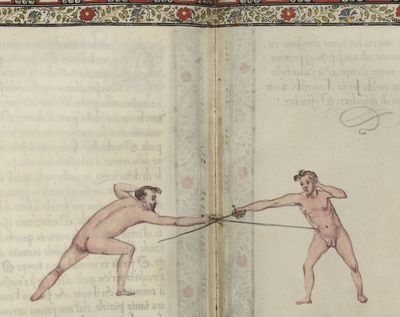

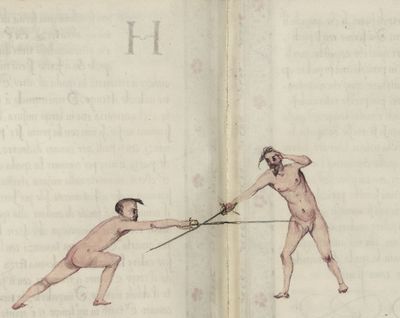

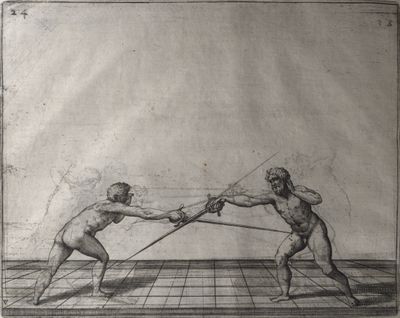

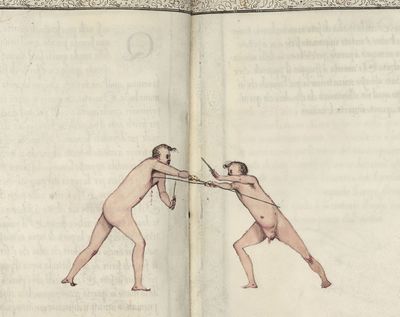

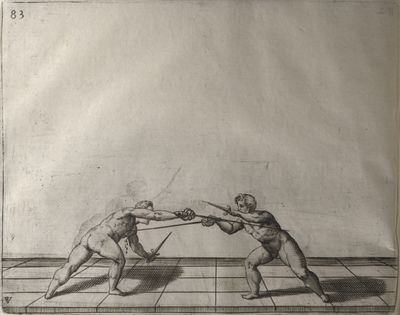

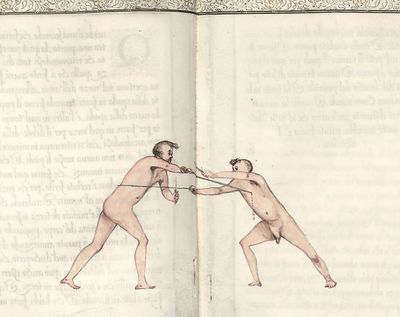

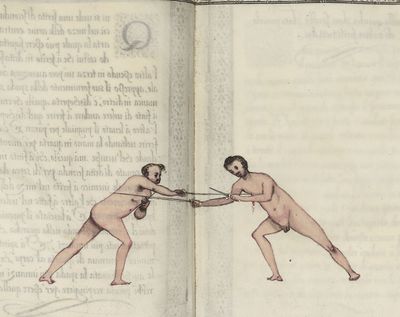

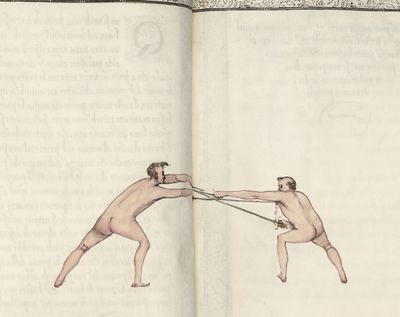

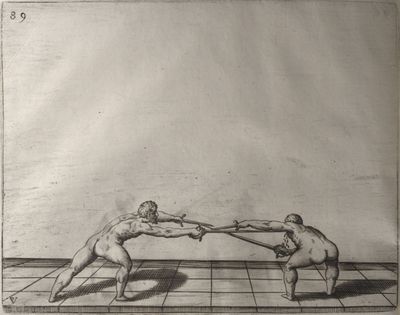

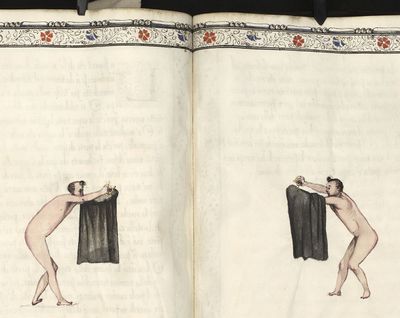

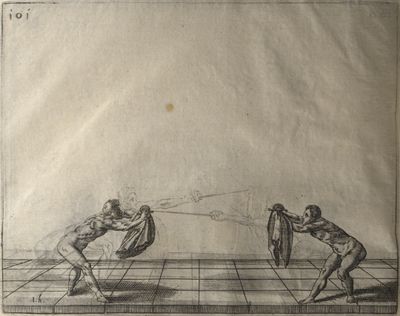

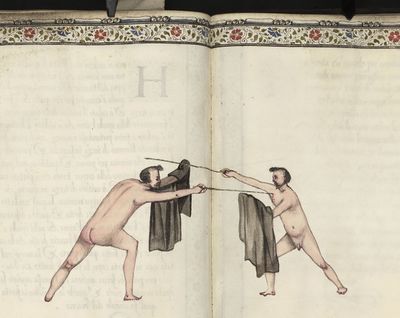

| [[file:GKS 1868 1 detail 13.jpg|400px|center]] | | [[file:GKS 1868 1 detail 13.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| [[file:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) 006.jpg|400px|center]] | | [[file:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) 006.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

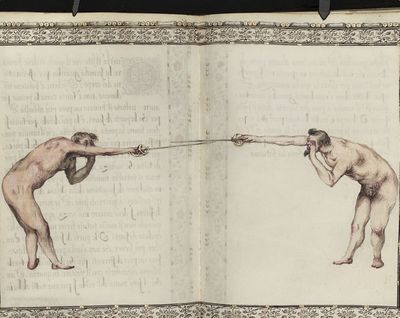

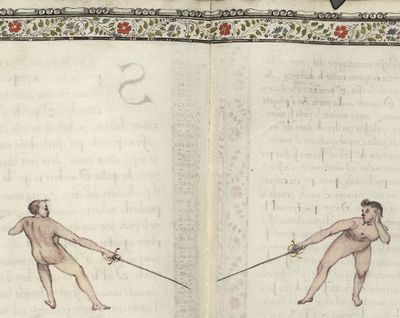

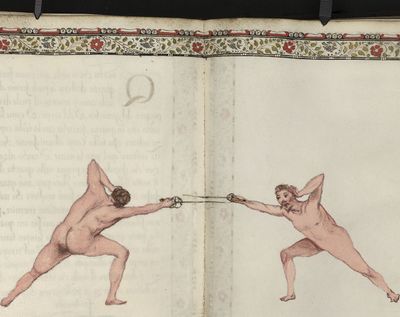

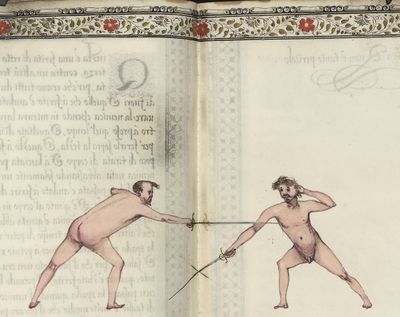

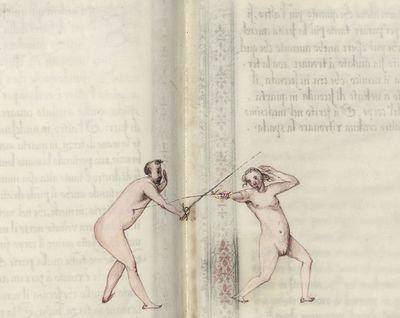

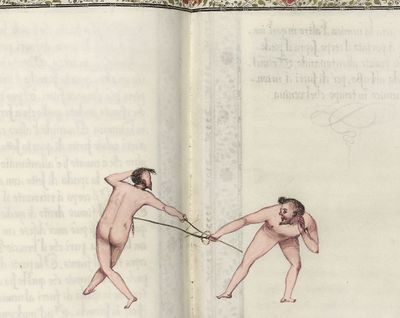

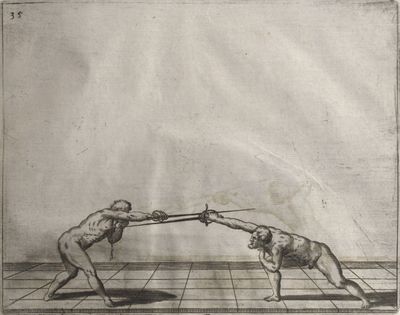

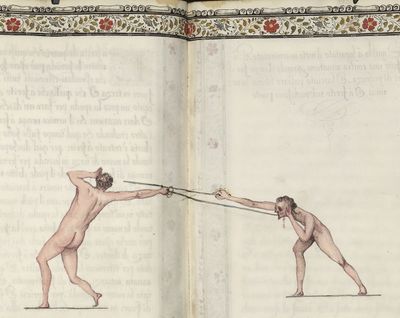

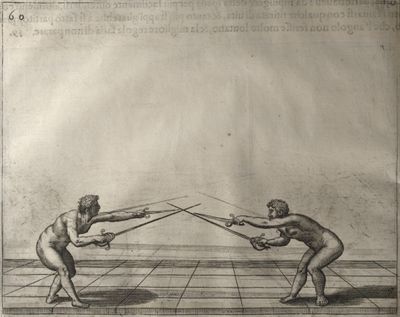

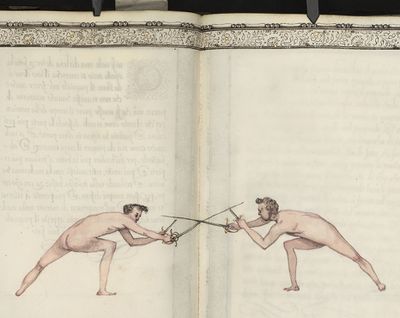

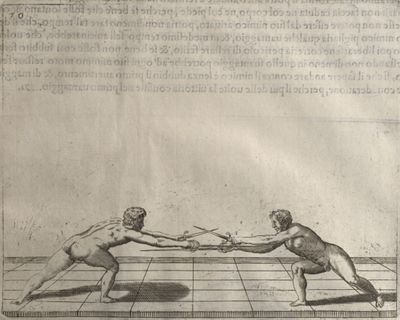

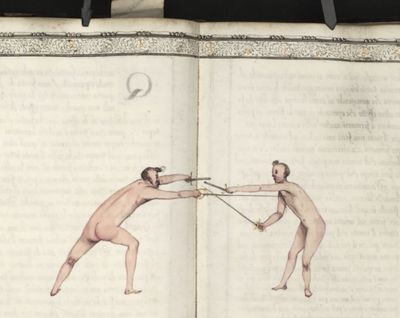

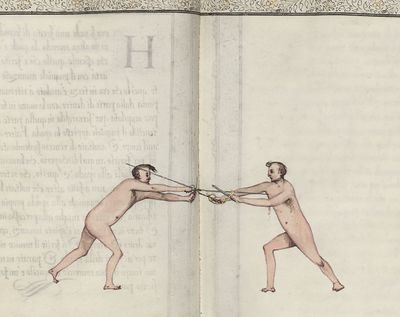

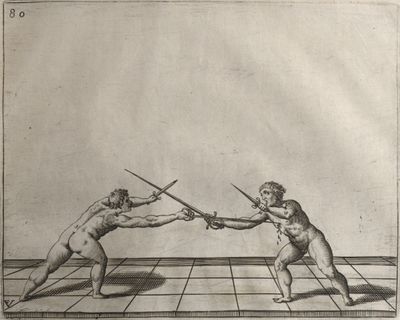

| − | | <p>[24] | + | | <p>[24] <br/><br/></p> |

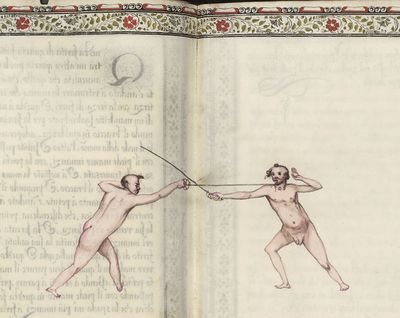

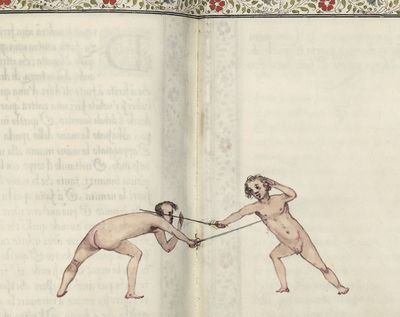

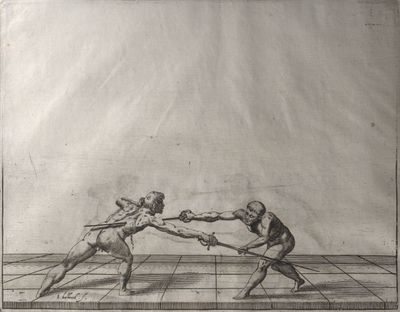

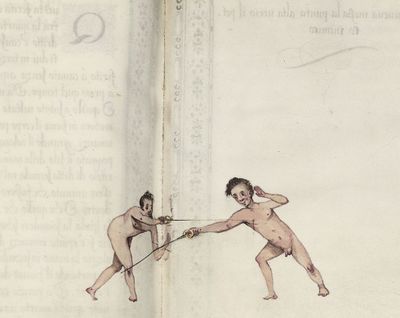

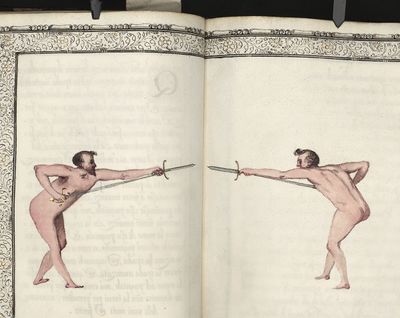

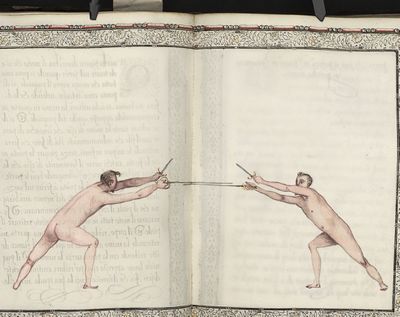

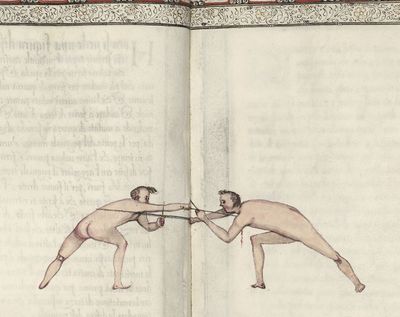

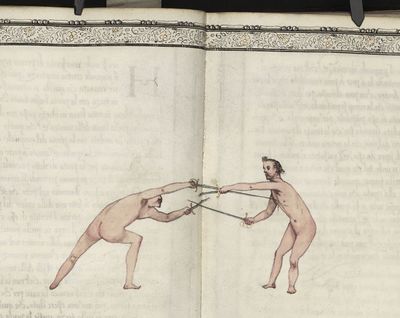

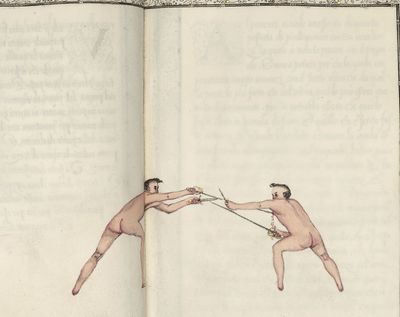

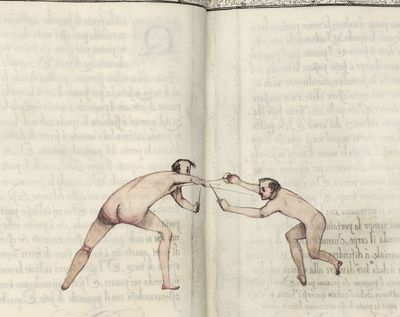

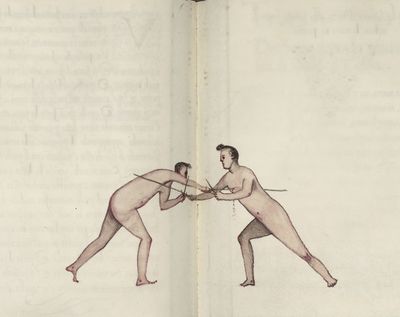

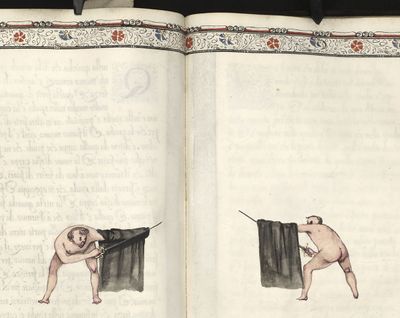

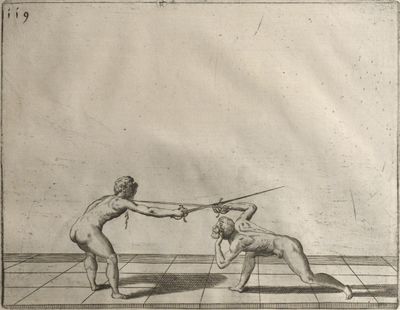

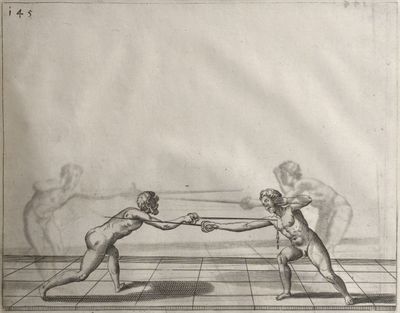

| − | <p>In this plate the sword is shown foreshortened, and the left side as far forward as the right. You have formed a guard in ''tierce'' and changed into ''seconde''. The sword is turned so far to the left as to be quite | + | <p>In this plate the sword is shown foreshortened, and the left side as far forward as the right. You have formed a guard in ''tierce'' and changed into ''seconde''. The sword is turned so far to the left as to be quite fore-shortened, and therefore only the cross or hilt is seen. This movement has been made in order to let the adversary approach. The body is bent forward so that it may not be hit save on the head and chest, and if the adversary attempts to hit you can parry with the left hand, which is held before the face, hitting with the same movement of the body and extending your sword into ''seconde''. If you have completed the position when your adverysary[!] advances, you can change to ''quarte'' and hit below or above his sword, according as he comes low or high, and can carry the body out of line without parrying, though you may parry and hit with this ''seconde''. If your adversary does not respond to this ''appel'', you must not remain in this position, but change your line, remaining steady on your feet, so that he may not take the ''time'' on that change; for if your feet were being brought together you could not parry, but if you were withdrawing it would be well to parry, since your adversary could be sure of making a hit. If when he took the ''time'', you were steady, you could advance or retreat according to the distance and intention of the adversary, because you would have adapted yourself for attack or defence at the same time.</p> |

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/40|2|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/41|1|lbl=33|p=1}} |

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/88|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/89|5|lbl=72|p=1}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/89|6|lbl=-}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 542: | Line 545: | ||

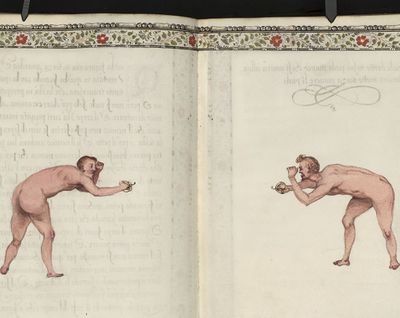

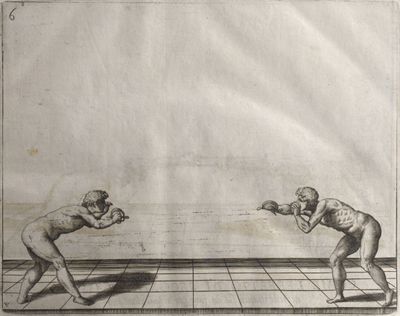

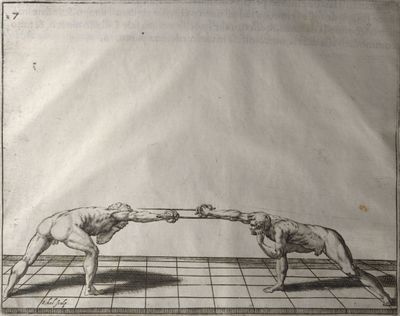

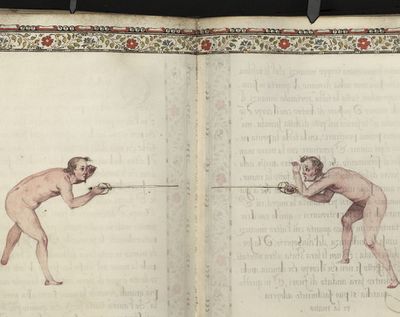

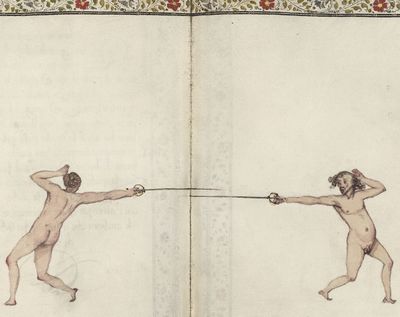

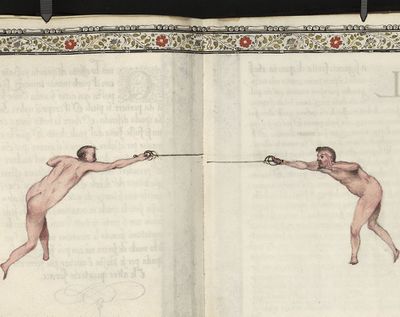

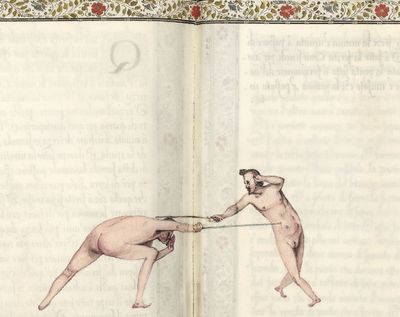

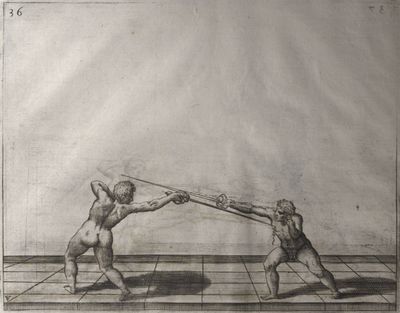

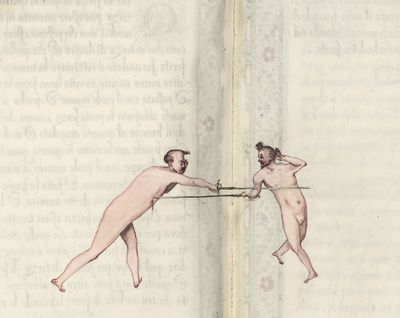

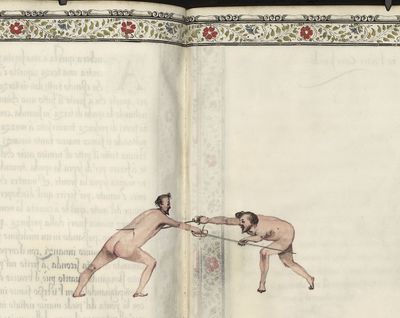

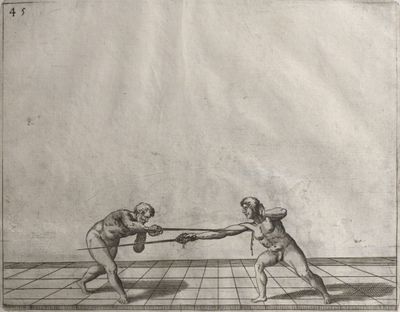

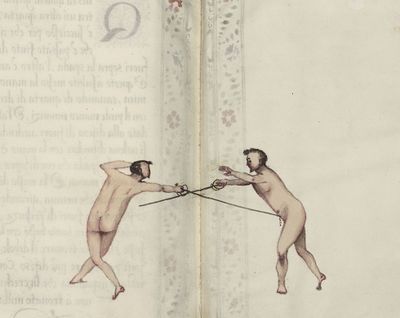

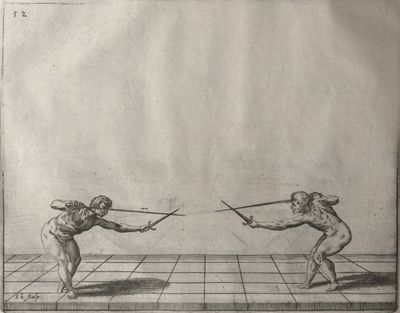

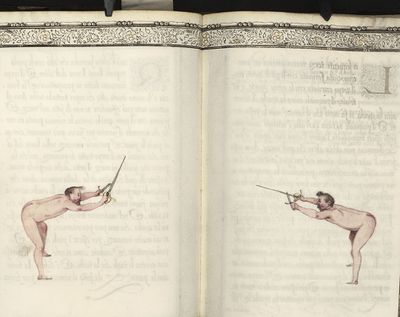

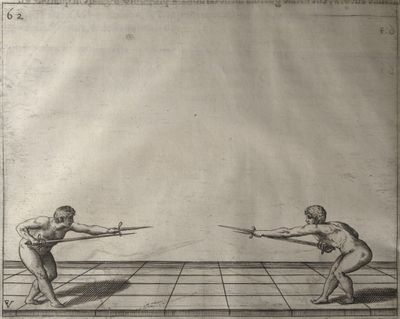

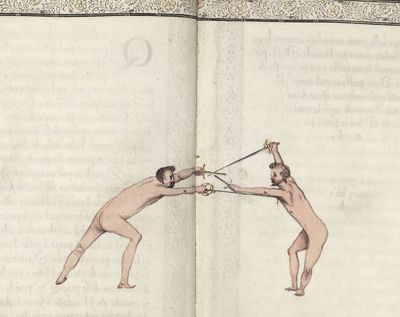

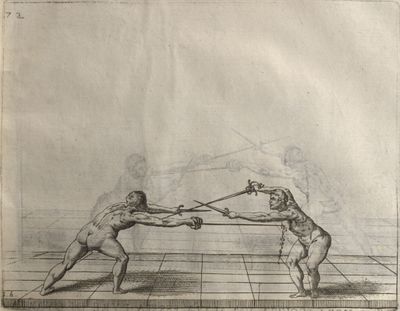

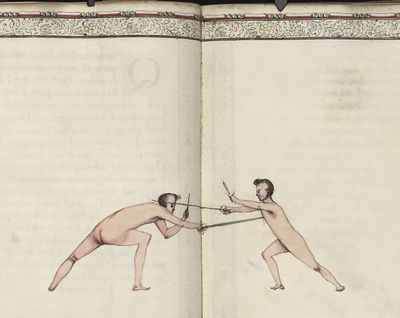

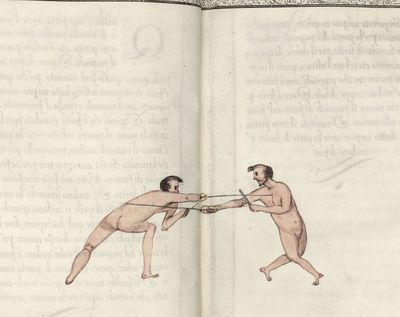

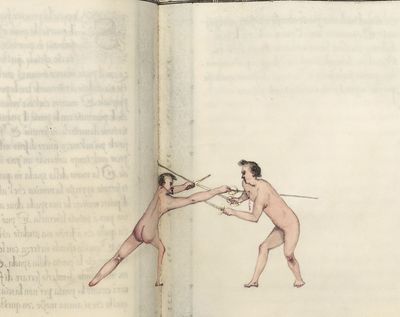

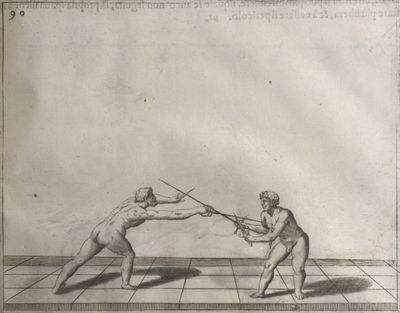

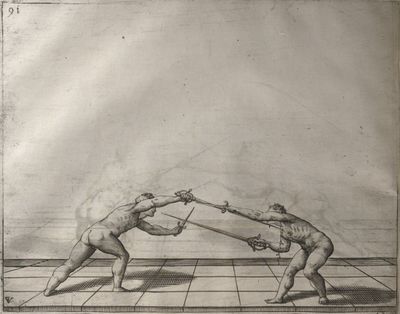

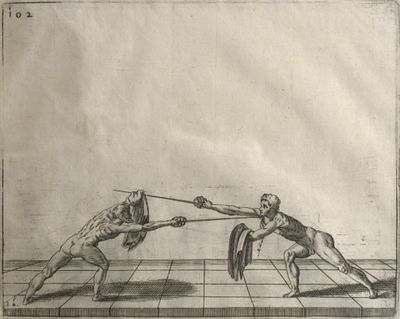

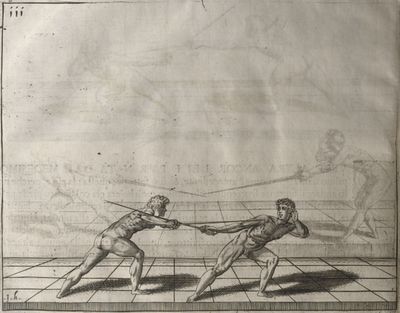

<p>The extension seen in this plate is made in ''seconde'' with the right foot, and can be made on the inside or the outside of the adversary's sword in the time when he is passing. The lunge is made with the idea of letting his sword pass in the air without parrying, if, as might be, he is in a guard of ''tierce'' or ''quarte''; but if he is in ''seconde'' you will not succeed with this lunge. If the adversary does not pass, it is not a good movement, for the body is so low and the feet so far apart that you cannot recover quickly enough to protect yourself. You should certainly make this stroke if your adversary passes in order to save yourself from the impact of his sword without parrying, and hit him at the moment of his passing. If you realise the opportunity it is quite safe, because the body is so low, that the knee and the head are covered under the line of the arm in such a way, that even if the adversary attempts to hit at the centre of your body, he will pass far above. Thus the position deceives the adversary; but you must have a care not to form it at too great a distance, for he could then lower his point again before it had passed, and your head would be in greater danger than before. If the movement is made within the proper distance this danger ceases, for at the moment when your adversary's sword approaches, your body goes to meet him and causes his sword to pass with even greater celerity.</p> | <p>The extension seen in this plate is made in ''seconde'' with the right foot, and can be made on the inside or the outside of the adversary's sword in the time when he is passing. The lunge is made with the idea of letting his sword pass in the air without parrying, if, as might be, he is in a guard of ''tierce'' or ''quarte''; but if he is in ''seconde'' you will not succeed with this lunge. If the adversary does not pass, it is not a good movement, for the body is so low and the feet so far apart that you cannot recover quickly enough to protect yourself. You should certainly make this stroke if your adversary passes in order to save yourself from the impact of his sword without parrying, and hit him at the moment of his passing. If you realise the opportunity it is quite safe, because the body is so low, that the knee and the head are covered under the line of the arm in such a way, that even if the adversary attempts to hit at the centre of your body, he will pass far above. Thus the position deceives the adversary; but you must have a care not to form it at too great a distance, for he could then lower his point again before it had passed, and your head would be in greater danger than before. If the movement is made within the proper distance this danger ceases, for at the moment when your adversary's sword approaches, your body goes to meet him and causes his sword to pass with even greater celerity.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{section|Page:Scienza | + | | {{section|Page:Scienza d'Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf/41|2|lbl=-}} |

| − | | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/89|7|lbl=-}} |

| − | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/89|8|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf/90|2|lbl=73}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 554: | Line 557: | ||