|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Sigmund ain Ringeck"

m (Michael Chidester moved page Sigmund Schining ein Ringeck to Sigmund Schining ain Ringeck over redirect) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{active development}} | {{active development}} | ||

{{infobox writer | {{infobox writer | ||

| − | | name = [[name::Sigmund Schining | + | | name = [[name::Sigmund Schining ain Ringeck]] |

| image = File:Sigmund Ringeck.png | | image = File:Sigmund Ringeck.png | ||

| imagesize = 250px | | imagesize = 250px | ||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

| below = | | below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Sigmund Schining | + | '''Sigmund Schining ain Ringeck''' (Sigmund ain Ringeck, Sigmund Amring, Sigmund Einring, Sigmund Schining) was a 14th or [[century::15th century]] [[nationality::German]] [[fencing master]]. While the meaning of the surname "Schining" is uncertain, the suffix "ain Ringeck" may indicate that he came from the Rhineland region of south-eastern Germany. He is named in the text as ''Schirmaister'' to Albrecht, Count Palatine of Rhine and Duke of Bavaria. Other than this, the only thing that can be determined about his life is that his renown as a master was sufficient for [[Paulus Kal]] to include him on his memorial to the deceased masters of the [[Society of Liechtenauer]] in 1470.<ref>The Society of Liechtenauer is recorded in three versions of [[Paulus Kal]]'s treatise: [[Paulus Kal Fechtbuch (MS 1825)|MS 1825]] (1460s), [[Paulus Kal Fechtbuch (Cgm 1507)|Cgm 1570]] (ca. 1470), and [[Paulus Kal Fechtbuch (MS KK5126)|MS KK5126]] (1480s).</ref> |

The identity of Ringeck's patron remains unclear, as four men named Albrecht held the title during the fifteenth century. If it is [[wikipedia:Albert I, Duke of Bavaria|Albrecht I]], who reigned from 1353 to 1404, this would signify that Ringeck was likely a direct associate or student of the grand master [[Johannes Liechtenauer]]. However, it may just as easily have been [[wikipedia:Albert III, Duke of Bavaria|Albrecht III]], who carried the title from 1438 to 1460, making Ringeck potentially a second-generation master carrying on the tradition.<ref>[[Christian Henry Tobler]]. "Chicken and Eggs: Which Master Came First?" ''In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts''. Wheaton, IL: [[Freelance Academy Press]], 2010.</ref> [[wikipedia:Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria|Albrecht IV]] claimed the title in 1460 and thus also could have been Ringeck's patron; this seems somewhat less likely in light of Ringeck's apparent death within that same decade, meaning the master would have had to have penned his treatise in the final few years of his life. In its favor, however, is the fact that Albrecht IV lived until 1508 and so both the Dresden and Glasgow versions of the text were likely created during his reign. | The identity of Ringeck's patron remains unclear, as four men named Albrecht held the title during the fifteenth century. If it is [[wikipedia:Albert I, Duke of Bavaria|Albrecht I]], who reigned from 1353 to 1404, this would signify that Ringeck was likely a direct associate or student of the grand master [[Johannes Liechtenauer]]. However, it may just as easily have been [[wikipedia:Albert III, Duke of Bavaria|Albrecht III]], who carried the title from 1438 to 1460, making Ringeck potentially a second-generation master carrying on the tradition.<ref>[[Christian Henry Tobler]]. "Chicken and Eggs: Which Master Came First?" ''In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts''. Wheaton, IL: [[Freelance Academy Press]], 2010.</ref> [[wikipedia:Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria|Albrecht IV]] claimed the title in 1460 and thus also could have been Ringeck's patron; this seems somewhat less likely in light of Ringeck's apparent death within that same decade, meaning the master would have had to have penned his treatise in the final few years of his life. In its favor, however, is the fact that Albrecht IV lived until 1508 and so both the Dresden and Glasgow versions of the text were likely created during his reign. | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

| <p>[1] {{red|b=1|Here begins the interpretation of the record}}</p> | | <p>[1] {{red|b=1|Here begins the interpretation of the record}}</p> | ||

| − | <p>In this, the knightly art of the long sword lay written; that Johannes Liechtenauer, who was a great master in the art, composed and created. By the grace of god he had let the record be written with obscure and disguised words, therefore the art shall not become common. And Master Sigmund | + | <p>In this, the knightly art of the long sword lay written; that Johannes Liechtenauer, who was a great master in the art, composed and created. By the grace of god he had let the record be written with obscure and disguised words, therefore the art shall not become common. And Master Sigmund ain Ringeck, fencing master to the highborn prince and noble Lord Albrecht, Pfalzgraf of Rhein and Herzog of Bavaria had these same obscure and disguised words glossed and interpreted as lay written and pictured<ref>The phrase "and pictured" is omitted from the Dresden.</ref> here in this little book, so that any one fencer that can otherwise fight may well go through and understand.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{paget|Page:MS Dresd.C.487|010v|png|lbl=10v|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS Dresd.C.487 011r.png|1|lbl=11r|p=1}} | {{paget|Page:MS Dresd.C.487|010v|png|lbl=10v|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS Dresd.C.487 011r.png|1|lbl=11r|p=1}} | ||

Revision as of 19:37, 29 June 2015

|

Caution: Scribes at Work This article is in the process of updates, expansion, or major restructuring. Please forgive any broken features or formatting errors while these changes are underway. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. Stay tuned for the announcement of the revised content! This article was last edited by Michael Chidester (talk| contribs) at 19:37, 29 June 2015 (UTC). (Update) |

| Sigmund Schining ain Ringeck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | date of birth unknown |

| Died | before 1470 |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Nationality | German |

| Patron | Albrecht, Duke of Bavaria |

| Movement | Society of Liechtenauer |

| Influences | Johannes Liechtenauer |

| Influenced | |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Early New High German |

| Archetype(s) | Hypothetical |

| Manuscript(s) |

|

| First printed english edition |

Tobler, 2001 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

Sigmund Schining ain Ringeck (Sigmund ain Ringeck, Sigmund Amring, Sigmund Einring, Sigmund Schining) was a 14th or 15th century German fencing master. While the meaning of the surname "Schining" is uncertain, the suffix "ain Ringeck" may indicate that he came from the Rhineland region of south-eastern Germany. He is named in the text as Schirmaister to Albrecht, Count Palatine of Rhine and Duke of Bavaria. Other than this, the only thing that can be determined about his life is that his renown as a master was sufficient for Paulus Kal to include him on his memorial to the deceased masters of the Society of Liechtenauer in 1470.[1]

The identity of Ringeck's patron remains unclear, as four men named Albrecht held the title during the fifteenth century. If it is Albrecht I, who reigned from 1353 to 1404, this would signify that Ringeck was likely a direct associate or student of the grand master Johannes Liechtenauer. However, it may just as easily have been Albrecht III, who carried the title from 1438 to 1460, making Ringeck potentially a second-generation master carrying on the tradition.[2] Albrecht IV claimed the title in 1460 and thus also could have been Ringeck's patron; this seems somewhat less likely in light of Ringeck's apparent death within that same decade, meaning the master would have had to have penned his treatise in the final few years of his life. In its favor, however, is the fact that Albrecht IV lived until 1508 and so both the Dresden and Glasgow versions of the text were likely created during his reign.

Ringeck is often erroneously credited as the author of the MS Dresd.C.487. While Ringeck was the author of one of the core texts, a complete gloss of Liechtenauer's Recital on unarmored longsword fencing, and perhaps also the anonymous glosses of his armored and mounted fencing, the manuscript contains an assortment of treatises by several different masters in the tradition (not just Ringeck), and it is currently thought to have been composed in the early 16th century[3] (well after the master's lifetime). Regardless, the fact that he authored one of the few glosses of Liechtenauer's verse makes Ringeck one of the most important masters of the 15th century.

While it was not duplicated nearly as often as the more famous gloss of Pseudo-Peter von Danzig, Ringeck's work nevertheless seems to have had a lasting influence. Not only was it reproduced by Joachim Meÿer in his final manuscript (left unifinished at his death in 1571), but in 1539 Hans Medel von Salzburg took it upon himself to create an update and revision of Ringeck's Bloßfechten gloss, integrating his own commentary in many places.

Contents

Treatise

Images |

Translation (from the Dresden) |

Dresden Transcription (1504-19) |

Glasgow Transcription (1508) |

Rostock Transcription (1563-71) |

Fragments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[1] Here begins the interpretation of the record In this, the knightly art of the long sword lay written; that Johannes Liechtenauer, who was a great master in the art, composed and created. By the grace of god he had let the record be written with obscure and disguised words, therefore the art shall not become common. And Master Sigmund ain Ringeck, fencing master to the highborn prince and noble Lord Albrecht, Pfalzgraf of Rhein and Herzog of Bavaria had these same obscure and disguised words glossed and interpreted as lay written and pictured[4] here in this little book, so that any one fencer that can otherwise fight may well go through and understand. |

[10v] Hie hept sich an die vßlegu~g der zedel In der geschriben stett die Ritterlich kunst des langes schwerts Die gedicht vnd gemacht hat Johannes lichtenawer der ain grosser maiste~ in der kunst gewesen ist dem gott genedig sÿ der hatt die zedel laußen schrÿbe~ mitt verborgen vñ verdeckte~ worten Daru~b dz die kunst nitt gemain solt werde~ Vnd die selbige~ v°borgneñ vñ verdeckte wort hatt maister [11r] Sigmund ain ringeck der zÿt des hochgeborne~ fürsten vñ herreñ herñ aulbrecht pfalczgrauen bÿ Rin vñ herczog in baÿern schirmaiste~ Glosieret vñ außgelegt alß hie in disem biechlin her nach geschrÿben stät dz sÿ ain ÿede~ fechter wol verömen vnd vestan mag der da ande~st fechten kan etc~ ~ |

[22r] Merck die zettl / dar in geschribñ stett / die kunst des langen schwerch die Johannes liechtñawen hat lassen schreiben mit verporgen vnd verdachtñ wortñ / die w selbigñ wort hat Maist~ Sigmund Emring verklert vnd aus gelegt / als In[5] diessem puech geschribñ stett vnd gemalt / vnd hat das gethon daru~b daz fu~rstñ vnd herrñ Ritter vnd knecht den die kunst zu gehõrt dester grosser lieb darzu habñ su~llen Anno dm~ 1508 |

[06r] Hie hebẽ sich an die Zedttel In den geschrieben stedt die Ritterlich kunst, des langen schwerdts die gedicht vnnd gemacht hat Johannes Liechtennaur der ein großer meister In der kunst gewesen ist. Dem gott gnedig sey, der hatt die Zedtel lasen schreiben mitt verborgen vnd verdackten wortten, darumb das die kunst nicht gemeyns solt werden, vnd dieselbigen verborgen vnd verdagkten worten der Zedtel, Die hat meister Sigmundt Einring zu derselbigenn zeit des hochgeboren fursten vnd herren herren Albrechts Pfaltzgraff bey Rein vnd hertzog in Bayernn schiermeister gewesen ist, also glossirt vnnd ausgelegtt, als sie den in diesem buchlein hernach geschrieben, vnd gemalt stehnn, das sie ein Jeder fechter wol vernemen vnd verstehen mag, der da anderß recht fechten kan. |

||||

[2] The foreword of the record

|

Die vor red der zedel ~ Jungk ritter lere |

Das Ist die vorredt. Junckh Ritter lere |

|||||

[3] This is the text of many good common lessons of the long sword

Note the gloss. This is the first lesson of the long sword: That you shall learn to make[8] the cuts properly from both sides, that is, if you otherwise wish to fence strongly and correctly. Understand it thusly: When you wish to cut from the right side, so see that your right foot stands forward. If you then cut the over-cut from the right side, so follow-after the cut with the right foot. If you do not do that, then the cut is false and incorrect, because your right foot remains there behind. Therefore the cut is too short and may not reach its correct path below to the correct other side in front of the left foot. |

Das ist der text von vil gu°tter gemainer lere des langen schwerts Willtu kunst schowen Glosa Merck dz ist die erst lere des [12r] langes schwercz dz du die hew võ baÿden sÿtten recht solt lernen hawen Ist dz du annders starck vñ gerecht fechten wilt Dz ver nÿm allso Wenn du wilt howe~ von der rechten sÿtten So sich dz dein k lincker fu°ß vor stee Vñ wenn du wilt howe~ võ der lincken sÿtten so sich dz dein rechter fu°ß vor stee Haw Häustu dann den ober haw° von der rechten sÿtten so folg dem haw nach mitt dem rechten fu°ß tu°st du dz nicht / so ist der how falsch vnd vngerecht wann dein [12v] rechte sÿten pleibpt dahinden Daru~ ist der haw zu° kurcz vñ mag sein rechten gang vndersich zu° der rechten sÿten andere~ sÿtten vor dem lincken fu°ß nicht gehaben |

[06v] Das ist der Textt von viel gutten gemeinen lere des lang~ schwerdts. Wiltu kunst schauen Glosa. Merck das ist die erste lere des langen schwerdts, das du die hew von beyden seitten recht solst lernen hauen, Ist das du anderst starck vnnd gerecht fechten wilt, das vernym also wen du wilt hauen, von der rechten seiten, so sich das dein lingker fueß vorstee, vnnd wen du wilt hauen, von der lincken seytten so sich das dein rechter fuß vorstee, hastu dan den vberhaw von der rechten seiten, so volge dem haw nach, mit dem rechten fuß, thustu das nicht so ist der haw falsch vnd vnrecht, wenn dein rechte seiten bleibet dahinden, darumb ist der haw zw kurtz vnd mag seinen rechten ganng vnder sich zw der andernn seiten vor dem lincken fueß nicht gehaben, |

|||||

The same when you cut from the left side and [you] do not follow-after the cut with the left foot. Thus the cut is also false. Therefore note from whichever side you cut, that you follow-after with the same foot, so you may execute all your plays with strength and all other cuts shall be hewn thusly as well. |

Des glÿchen wenn du haw°st von der lyncken sÿtten vnd dem haw nicht nachfolgest mitt dem lincken fu°ß so ist der haw° och falsch Daru~ so merck von welcher sÿtten du haust / dz du mitt dem selbige~n fu°ß haw° nachfolgest so magstu mitt sterck alle dein stuck gerecht trÿbeñ Vnnd also süllen alle andere hew° [13r] och gehawen werden ~:· |

deßgleichen wen du haust von der lincken seiten, vnd dem haw nicht nach volgest mit dem lincken fueß, So Ist der haw auch falsch, Darumb so merck von welcher seitten du hawest, das du mit dem selbig~ fueß, dem haw nachvolgest, so magstu mit stercke alle deine stucke gerecht treiben, vnd also sollen all ander hew auch gehauen werdenn. |

|||||

[4] Again, the text about a lesson

Glosa When you come against him in Zufechten you shall not await his attack, and neither shall you wait to see what he is thinking about doing to you. All fencers who are hesitant and wait for the incoming attack, and do nothing other than to ward it away, they gain very little joy from this sort of practice because they are often beaten. |

Der text aber võ aine~ lere Wer nach gat haw°en / Glosa Wenn du mitt dem zu°fechten zu° im kumpst so solt du vff sein hew nicht sechen noch warten wie er die gegen dir trÿbt wann alle fechte~ die do sechen vñ warten vff aines anderen hew Vnnd wellend anderß nichtß nicht~ thon [13v] dañ verseczen die durffen sich söllicher kunst wenig fröwen wann sÿ werden do bÿ offt geschlagen |

Der Textt aber von einer Lehre Wer nach gehet hauen [07r] Glosa. Mercke das ist wen du mit dem zufechten zw im kumbst, so soltu auff sein hew nicht sehen auch noch wartten, wie ehr die gegen dir treybtt wenn alle fechter die da sehen vnd wartten, vff eines andern hew, vnnd wöllen anderst nicht thun, wen versetzen die bedurffen sich solcher kunst wenig freuen wann sie werden dabey offtt geschlagen. |

|||||

Always fight with the strength of the whole body! Cut close into him, to the head and to the body, so he cannot change-through in front of your point. And when the cut ends up in the bind you shall not hesitate but shall quickly and fluently make attacks against the nearest opening, using the five strikes and other techniques that will be described later. |

Item du solt mercken alles dz du fechten wilt dz trüb mitt ganczer störck deines lÿbs Vnnd haw im do mitt nahent ein zu° kopff vñ zu° lÿb so mag er vor dinem ort nicht durch wechslen Vñ mitt dem haw° solt du im den anbinden des schwerts der zek zeckru°re nicht vermyden zu° der nächsten blöß di dir hernach in den fünff hewen vnd in anderen stucken vßgericht [14r] werden ~~ :· |

Item merck alles was du fechten wilt, das treib mitt gantzer sterck deines leybes, vnnd haw im damit nahẽt zw dem kopff, vnd zu dem leyb, So mag ehr von deinem ort nicht durch gewechselnn vnd mit dem haw soltu in dem anbinden des schwerdts der Zweck rur nicht vermeydenn zẅ der negsten blöße die dir hernach in denn funff hewenn vnd In andern stucken ausgericht werdenn. |

|||||

[5] Another lesson.

Glosa This lesson applies to two types of people: those who are left-handed and those who are right-handed. When you come against him in Zufechten, if you are right-handed and want to strike him, you must not throw your first cut from your left side. That is because this is weak and cannot bring strength to bear if he binds the strong of his blade against you. Therefore, cut from your right side, so you can be strong and skillful in the bind and can do as you will. Similarly, if you are left handed, do not cut from the right, because the art is pointless when a left-hander tries to fence from the right side. Likewise this statement applies to a right-hander fencing from the left side. |

aber ain lere Höre waß du schlecht ist / Glosa Mörck die lere trifft an zwu° personen aine~ lincken vnd ain grechten / vñ mainest den man zu° schlagen So haw° den ersten haw° Das vernÿm also. Wann du mitt zu° fechten zu° im kumpst Bist du dann gerecht vñ mainest den man zu° schlachen So haw den erste~ haw° nicht von der lingen sÿtten Wann der ist schwach vnd magst damitt nicht [14v] wider gehalten wann man dir starck daruff bindt Darum so haw der rechten sÿtten / so magst du starck am schwert mitt kunst arbaÿten waß du wilt Des gelichen Bist du linck so haw° och nitt von der rechtt~ wenn die kunst ist gar wild aine~ lincken ze triben von der rechten sÿtten Des glich ist es och aine~ rechten von der lincken sÿtten ~ |

Aber ein lehre. Hor was da schlecht ist Glosa. Merck die lehre trifft an zwo p~son einem lingcken vnd einem rechten, vnd das vernym also wen du mit zufechten zw im kumbst, bistu den gerecht, vnd meinst, den man zu schlagen, so haw den ersten haw nicht, von der lincken seyten wan ehr ist schwach vnd magst damit nit wyderhalten wan man dir starck darauff bindt darumb so haw von der rechten seiten so magstu starck am schwerd mit kunst arbeiten was du wilt, |

|||||

[6] A lesson about "Before" and "After".

Glosa Mark well that more than anything else you must understand "Before" and "After", because these two concepts are the grounding from which all fencing comes. |

Daß ist der text vñ lere ain lere von vor und nach Vor vñ nach die zwaÿ dinck / Glosa Merck dz ist dz du vor allen sachen wol solt verston daß vor und daß nach / wann die zwaÿ ding sind ain vrspru~g do alle kunst des fechtenß außgät Daß vernÿm also Daß for das vor daß ist dz du all weg solt vorkum~en mitt aine~ haw° ode~ mitt aine~ sch stich Im zu° der blöß Ee wann er dir zu der deinen so mu°ß er dir verseczen / so arbaÿt in der versachung behentlich für dich mitt dem schwert |

||||||

[7] Mark also: "Before" means that you shall always perform a strike or thrust against his openings, before he does the same to you. Then he must defend against you! And work deftly both in the defence and in moving your sword from one opening to another, so he cannot have the chance to perform his own techniques between yours. But if he rushes in close to you, deal with him through wrestling. |

[15v] von ainer be blöß zu° der andere~ so mag er vor deiner arbaÿt zu° seine~ stucken nicht kom~en Aber laufft er dir ein eÿnn So kom~e fo vor mitt dem ringen ~~~≈~~~~~~~ |

||||||

[8] Mark, that which is called "After". Mark, that if you cannot come in the "Before", wait for the "After". This will defeat all techniques that he does against you. When he comes at you so that you must defend yourself against him, so work deftly "in the Instant" with your defence against his nearest opening, so strike him before he can finish his technique. Thus you win the "Before" and he is left in the "After". You shall also know how you can use "the Instant" against his "weak" and "strong" parts of the sword. |

Hie mörck was da haÿsst daß nach Mörck magstu zu° dem vor nitt kom~en So wart uff dz nach dz sÿnd die brüch uff allen stu°ck die er vff dich trÿbt Das vernÿm also Wann er vorkumpt daß du ihm verseczen mu°st So arbait mitt der versäczung / Indes behentlich für dich zu° der nächsten blöß So triffestdu in ee Wann [16r] er sein stuck verbringtt Also gewinstu aber dz f vor Vñ er blÿpt nach Auch soltu in dem vor vñ nach mörcken wie du mitt wort /in des/ arbaitten solt nach der schwech vnd nach der störck seines schwertß Vnd das vernÿm Also Von dem gehulcze des schwerts by biß in die mitten der clingen Hatt dz schwert fin sin störcke dar mitt du wol magst wide~ gehalten wann man dir dar an bindt Vñ fürbaß von der mitt biß an den ort hat es sein schwöch da magst nitt nicht wider |

||||||

[9] From the hilt of the sword to the blade's centre the sword is "strong", and with this you can meet against his blade when you bind against it. And further, from the middle to the point the sword is "weak", which should not be brought against his blade. And when you really understand these things you can work skillfully and defend yourself well, and later teach princes and lords, so that they with these same skills can protect themselves well in play and earnest. But if you become frightened easily you should not learn fighting arts, because a weak and frightened heart—it does not help you—it defeats all of your skills. |

[16v] gehalten Vñ wenn du die ding recht verstest So magstu mitt kunst wol arbaitten vñ dich darmitt wören vñ fürbaß lerne~ fürsten vñ her~eñ dz sÿ mitt der selbige~ kunst wol mügen besten In schim~pff vñ in ernst Aber erschrckstu gern so saltu die kunst des fechtens nitt lerne~ Wann ain blöds verzags hercz dz tu°t kain gu°t wann es wirt bÿ aller kunst geschlagen ~ ~ ~ |

||||||

[10] The Five cuts.

Glosa Mark well, the teaching verses present five secret cuts, which many swordmasters do not know to speak about. You will learn not to strike any other cuts when you come from the right side against one who stands against you in defence. And try if you can to hit an opponent with the first strike using one of these five cuts. The one who can counter with these against an opponent without being hurt will be praised by the master of the markverses, and his skill shall reward him more than another fencer who cannot fence with the five cuts. And how you shall throw the five cuts you will find hereafter recorded in the verses that talk about these same five cuts. |

Der text võ den fünf hewen Fünff hew° lere dem wir geloben / in kunsten gern zu° lonen ~:· Merck die zedel seczt fünff verborgne hew° Da von vil maiste~ des schwerts nicht wissen zuo zu° sagen Die soltu anders nicht lerne~ hawen wann võ der rechten sÿtten gege~ dem der sich gegen dir stöllet zu° der were Vñ versu°ch öb du mitt aine~ haw vsß den fünffen den man mitt dem ersten schlag mügest treffen Wer dir die brechenn kan on seine~ schaden / so wirt im gelopt Von dem maiste~ der zedeln daß im siner kunst [17v] bas gelonet soll werde~ dann aine~ andern fechtern der wÿde~ die funff hew nicht fechten kann Vñ wie du die fünff hew howen solt / dz fündest du in den selbigen funff hewen her nach geschriben / |

[07v] Das ist der Text von denn funff hewenn. Funff hewe lehre Glosa. Merck die zedtel setz verbo[r]gen hew daruon viel meister des schwerdts nit wissen zu sagen die soltu anderst nicht lerne[n] hauen wan von der rechten seytten gegen de[n] der sich gegen dir stellet zur wehre vnnd ve[r]such ob du mitt einem haw aus denn funff[?] den man mit dem ersten schlag mugst treffe[n] wer dir die brechen kan, an sein schaden den soll wirt gelobett vonn dem meister der zetel da[s] im sein kunst böß gelonet sol werd~, wen einem anndernn fechter der wider die funff haw nit fechtenn kann, vnnd wie du die funf hew hawen solt, das vindestu hernach geschribenn. |

|||||

[11] The techniques of the markverses.

Glosa Here are listed the correct and most important techniques in fighting with the longsword, they are named specifically so that you may understand them better. They are seventeen in number and begin with the five cuts. |

Das ist der võ den stucken de~ zedeln Zorn haw · krump · zwerch Glosa [18r] Mörck hie werden genampt die rechten haüptstucke der kunst deß langen schwerts wie ÿettlichs besunde~ haist mit dem namen / daß du die dester baß ver sten kündest Der ist sibenzechen an der zal Vnd heben sich an den funff hewen an / ~~ Item num nun mörck der erst haw haist der zorn haw |

||||||

The first cut is called the wrath strike, |

[18v] hütten |

||||||

| And how you will perform the hanging and windings, and how you shall perform all these named techniques, all this you will find written hereafter. | Vnnd wie du dich mitt den heng~ und winden enplösen solt Vnd wie du alle vorgenampte stuck trÿben solt daß vindestu alles her nach geschriben ~ ~ ~ ~ :· | ||||||

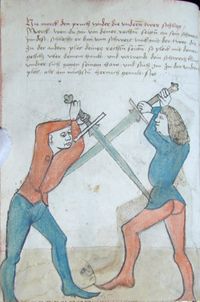

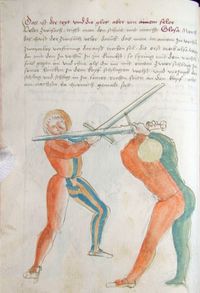

[12] Do the Zornhau with these techniques.

Glosa When someone cuts against you from above from their right side, so cut with a strong Zornhau (wrath strike) with the long edge from your right shoulder. If he is weak in the bind, thrust in with the point along his blade to his face, and threaten to stab him. |

[19r] Das ist der zorn haw° mitt sinen stucken ~ Wer dir ober haw°et Glosa Daß vernÿm also Wann dir ainer von siner rechten sÿtten oben oben [!] ein hawet so haw ainen zorn haw mitt der langen schnide~ och von diner rechte~ achslen mitt im starck ein Ist der dann waich am schwert / so schüß Im den ort für sich lang ein zu° dem gesicht Vnnd träw im zu° stechen ·~·:·~· |

Das ist der Zornhaw mitt seinenn stuckenn. Wer die oberhawet Glosa. Das vernim also, wenn dir einer vonn seiner Rechtenn seiten obin inhawet, So haw einenn Zorenhaw mit der lanngenn schneyden auch vonn der rechten achselnn mit Im starck, Ist er dann waich am schwert, So scheus im den ort fursich, lanng im zu dem gesicht, vnd dro Im zu stechenn, als hernach am nechsten gemachtt stehet. |

|||||

[13] Another technique from the Zornhau.

Glosa When you thrust after a Zornhau and he becomes aware of the point and strongly defends against the thrust, twitch your sword up, over and away from his sword and cut him on the other side of his sword up into his head. |

Aber ain stuck vß dem zorn haw° Wirt er es gewar Glosa Wann du mitt dem zorn haw den ort ein schüst wirt er dann deß orts gewar vñ verseczt den stich mit störcke So ruck dein schwert übersich oben ab von dem sinen Vñ haw im zu° der andren sÿtten an sine~ schwert wider oben ein zuo dem kopffe ~~ |

Aber ein stuck aus dem Zornhaw. [08r] Wirtt es gewar, Glosa. das ist, wenn du Im mit dem Zornhaw denn ortt inschust, als vor am nechstenn gemachtt stet, Wirt er dan des orttes gewar, vnnd versetzt denn stich mit sterck So ruck dein schwert vbersich oben ab von dem seinen vnnd haw im zu der Anndernn seitenn ann seinẽ schwert wider oben in zu dem kopff als hie gemachtt stett. |

|||||

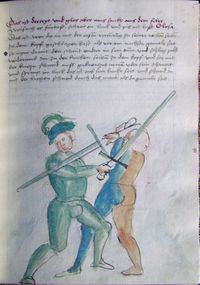

[14] Another technique from the Zornhau.

Glosa When you cut in against him with a Zornhau and he defends himself and holds backs, strong against you in the bind, so become strong again against him in the bind and push up with the "strong" of the sword against the "weak" of his sword, and wind your hilt high in front of your head, and thrust down from above into his face. |

Aber ein stuck vß de~ zornhaw° Biß störcker wider / Glosa Wenn du im mitt dem zornhaw° Inhaw°st verseczt er dir daß vñ pleibt dir damitt [20r] starck am schwert So bÿß gen im wider starck am schwert Vñ far uff mit der störck dines schwerts in die schwöchi sines schwerts vnd wind am schwert de din gehülcz f~ vorne~ für dein hopt haupt vñ so stich in oben zu° dem gesichte ~ |

Aber ein stuck aus dem Zornhaw. Bis stercker wider, Glosa. Merck das ist, wenn du Im mit dem Zorenn inhawest, als vorn am nechstenn gemacht stet, Versetzt er dir das, vnnd bleibt dir damit starck am schwert, So biß gen Im wider starck am schwert, Vnnd far auf mit der sterck deines schwerts, Inn die schweche seines schwerts, vnnd winde am schwerte dein gehiltz, vorn vor deinem haupt, vnnd stich Im oben in zu dem gesicht als hie gemalt stet. |

|||||

[15] Another technique from the Zornhau. When you use the winding against him and thrust down from above—as mentioned already—and he pushes up high with the hands and uses the hilt to defend against your upper thrust, so stand in the winding and thrust your point downwards between his arms and chest. |

Aber ain stuck vß dem zornhaw° Wann du Im mitt dem winden oben ein stichst / alß vor stett / fört er den hoch vff mitt den henden vñ versetzt mitt dem gehülcze den obern sttich stich so plÿb alst also sten in dem winden vnd setz im den ort [20v] niden zwischen sinen armen vñ der brust ~ ~~ |

Aber ein stuck aus dem Zornhaw. Wenn du Im mit dem winden obein instichst, als vor gemalt stet, fert er dann hoch auf mit den hendenn, Vnnd versetzt mit dem gehiltz den oberstich. So beleib also stehenn in dem winden, vnnd setz im den ortt niden zwischen seinen armen ann die brust, als hie vnden gemalt stet. |

|||||

[16] A counter to the taking-away. When you bind strongly against him and he twitches away his sword up and over your sword and in the bind cuts against you on the other side of your sword to your head, so bind (strike) strongly with the long edge in against his head. |

Ain bruch wide~ daß abneme~ Mörck wenn du mitt ainem starck am schwert bindest Ruckt er dan sein schwert übersich oben abe von dine~ schwert vñ haw~t dir zu° der andere~ sÿtten am schwert wider eÿn zuo dem kopffe So bind starck mitt der langen schnÿden Im oben eÿn zu° dem kopffe ~~ |

Ein bruch wider das abnemenn. [08v] Merck du wenn du mit einẽ starck an sein schwert bindest, ruckt er dann sein schwert vbersich oben ab, vonn deinem schwert, vnd hawt dir zu der anndern seitenn am schwert wider in zu dem kopff, So wind starck mit der lang~ schneiden im oben in zu dem kopff. | |||||

[17] A good lesson.

Glosa When one binds against your sword with a cut or thrust or anything else, you must find out whether he is soft or hard in the bind. And when you find this, you will "Instantly" know what is best to do, to attack him with "Before" or "After". But in the attack you shall not be too hasty to go into close combat, because close combat is nothing other than the windings in the bind. |

Hie mörck ain gu°tte lere Das öben mörck / Glosa Daß ist dz du gar eben mörcken solt wann du dir aine~ mitt ainem haw~ oder mit aine~ stich oder sunst an din schwert bintt bindet ob er am schwert waich oder hört ist vñ wenn du das enpfunden hast So solt du /In das/ wissen welchses dir am beste~ sÿ ob du mitt dem vor oder mitt dem nach an in hurten solt Abe~ du solt dir mitt dem an hurten nicht zu° gauch laussen sÿn mitt dem krieg wenn der krieg ist nicht anders dann die winden am [21v] schwert |

Hie merck ein gute lehre. Das eben merck Glosa. Das ist, das du gar ebenn mercken solt, wẽ dir einer mit einem haw oder mit einem stich, oder sonst ann dein schwert bindet, ob er am schwert waich oder hert ist, vnnd wen du das empfunden hast, So solt in dan wissen, welches da am besten sey, ob du mit dem vor, oder mit dem nach arbeiten solt, aber du solt dir damit nit zu goch lassen sein, mit dem krieg, wen der krieg nit anderst ist, wen das windenn am Schwert. |

|||||

Perform close combat like this: when you cut against him with a Zornhau, when he defends himself quickly, you shall go up in an orderly fashion with the arms and wind against his sword with your point in against the upper opening. If he defends against this thrust, stand in the winding and thrust with the point into the lower openings. If he follows further after the sword in self defence, go under his sword with the point through to the other side and hang your point over in against the other opening on his right side. In this way he will be cut down in close combat both above and below, because you (unlike he) can perform the movements correctly. |

Item den krieg trÿb also Wam [!] du Im mitt dem zorn haw~ In haw~est Alß bald er dann verseczt so far wol vff mitt den armen vñ wind im den ort am schwert ein zu° der obern blöß verseczt er denn den stich So blÿb sten in de~ winden vñ stich mitt dem ort die vnder blöß folgt er dann fürbaß mitt der versaczu~ge dem ss schwert nach so far mitt dem ort vnde~ sÿn schwert durch vñ heng im den ort oben ein zu° de~ andere~ blöß sine~ rechten sÿtten Also wirt er mitt dem krieg oben vñ vnden beschämpt Ist daß du die ge/ [22r] fört andrest recht kanst trÿben ~ |

Item denn krieg treib also, wenn du Im mit dem Zornhaw inhawest, als bald er denn versetzt, so far wol auf mit denn Armen, vnnd windt im den ort am schwert in zu der obern bloß, versetzt er dan den stich, so beleib sten in dem winden, vnnd such mit dem ort die vntern bloß. Volgt er dann furbas mit der versatzung deinem schwert nach, so far mit dem ortt vnter sein schwert durch, vnd heng Im denn ort oben [09r] in zu der anndern ploß seiner rechten seiten, also wirt er mit dem krieg oben vnd vnden beschemet, ist das du du [sic] gefert anders recht kannst treybenn. |

|||||

[18] How one in all windings shall find correct cuts and thrusts.

Glosa That is to say that you should in all windings find the correct cut, thrust or slice in this manner: when you wind, you shall become immediately aware of which the three will work best for you to use. This is so that you do not cut when you should thrust, and that you do not slice when you should cut, and so that you do not thrust when you should slice. And mark: when your opponent defends against the one, you should strike with the other. Also: if one defends against your thrust then use the cut. If he rushes in towards you, use the lower slice against his arm. Remember this in all fights and binds with the sword, if you want to defeat the masters who set themselves against you. |

Wie man In allen winden hew° stich recht vinden sol ~ In allen winden Glosa Daß ist daß du in allen winden hew stich vñ schnitt recht finden solt Also wenn du windest dz du da mitt zu° handt solt brüffen weches dir vnder den de drÿen daß best sÿ zu° triben al also dz du nicht hav~est wann du steche~ solt vñ nit schnidest wañ du hawen solt vñ nicht stechest [22v] wann du schniden solt Vñ mörck wan man dir der aÿnes verseczt dz du in mitt dem andern treffest Also / versecz man dir den stich so trÿb treÿb den haw° Laufft man dir eÿnn so treÿb den vndern schnitt In sin arm des morck in allen treffen vñ anbinden der schwert wilt du anderst die maister effen die sich wider dich seczen ~~ : ~ :· |

Wie mann in den winden hew, stich gerech[t] findenn sol. Inn allenn windenn Glosa. Das ist, das du in allen windenn, hew stich vnnd schnit recht findenn solt, Also wenn du windest, das du damit zu hand prufen, welches dir vnter den treyẽ das beste sey zu treybenn, der hew, oder stich, od~ schnit, also das du nit hawest, wen du stechenn solt, Vnnd nit schneidest, wenn du hawen solt. Vnnd merck, wen man dir der eins versetzt, das du In mit dem andern triffest, das merck in allen treffen, vnnd anbinden der schwert, wiltu anders die meister effen die sich wider dich setzenn. |

|||||

[22] The four openings.

Glosa Here you will learn about people's four openings, against which you will always fence. The first opening is on the right sight, the second on the left side, above the man's belt. The other two are likewise on the right and left sides under the belt. Always pay attention to the openings in Zufechten. His openings you shall skillfully seek without danger: with thrusts with the the outstretched point, with travelling after and with all other techniques. And do not pay heed to what he tries to do with his techniques against you, but fence with belief and throw strikes that are excellent and that do not allow him to come at you with his own techniques. |

Von den vier blossen Vier bloß wisse / Glosa Hie soltu morcken die vier blossen an dem man da du all wegen zu° fechten [23r] solt Die erst bloß ist die recht sÿtt seÿtt die ander ist die link seÿtt oberhalben der girtel deß manß Die ander zwuo sind och die recht vnd die linck seÿtten vnderhalben der girtel Der blossen nÿm eben war in dem zu°fechten mitt welcher er sich gege~ dir enblösse der selbigen reme künstlichen on far mitt einschiessen des langen orts mit nachraisen vñ sunst mit allen geförten vñ acht nitt wie er mit sÿne~ geförten gegen dir bar gebar So vichtest du gewisß vnnd schlechst schlege daruß die do treffenlich sind vnd lau laust in domitt zu° seine~ stucken nitt komen ~~~ : ~ |

Vonn denn vier blossenn. Vier blosse wiß Glosa. Hie soltu merckenn die vier blossenn ann dem man da du alleweg zu fechtenn solt, die erste bloß ist, die recht seytenn, die ander die linck oberhalb der gürtel des mans, die anndernn zwo sind auch die recht, vnnd die linck seyt vnterhalb der gürtel. Der blossenn [09v] nim ebenn war in dem zufechtenn, mit welcher er sich gegenn dir emplöst, derselbenn reine [sic] kunlich an far mit inschiessenn des langenn orts mit nachreysenn, Vnd auch mit denn Winden am schwert, vnnd sonst mit allenn gefertenn, vnnd Achte nicht, wie er mit seinenn geferttenn gegenn dir gepar. So fichstu gewiß, vnnd schlechst schleg daraus die da treflich sindt, vnnd lest in damit zu seinenn stucken nicht kummenn. |

|||||

[23] Explanation of doubling and mutating: how these break the four openings.

Glosa When you would like to skillfully break up the four openings for him, use the doubling against the upper openings and the mutating against the other openings. Certainly I say to you that he cannot defend himself against this, and can succeed with neither cut nor thrust. |

[23v] Der text vnd die gloß von de~ dupliern vnd von dem mutierñ Wie die brechen die vier blossen ~~ Wilt du rechen Glosa Daß ist Wann du dich an eine~ rechen wilt also / dz du im die vier blossen mitt kunst wilt brechen d So trÿb dz dupliern zu° der oberen bo blössen gen de~ störcki seines schwerts vñ daß mutiern zu° der anderen blösß [24r] So sag ich dir für war daß er sich dar von nitt schüczen kan vnd mag weder zu° schlachen noch zu° stechen komen ~ |

Der text vnnd die gloss von dem dupliern vnnd von mutiern, wie die prechenn die vier blossenn. Wiltu dich rechenn, Glosa, das ist wenn du dich Rechen wilt, an einẽ, also das du Im die vier blossenn mit kunst balde wilt brechenn, So treib das dupliern zu der obernn bloß, gegenn der sterck seines schwerts, Vnnd das mutiern zu der Andernn bloß, So sag Ich dir fur war, das er sich darvor nicht behuetẽ kann, vnd mag weder zu schlegenn noch zu stichen kummenn. |

|||||

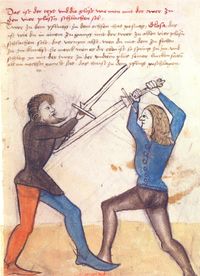

[24] Doubling. When you cut in with a Zornhau or another Oberhau and he defends himself strongly, so "Instantly" thrust your pommel in under your right arm with your left hand, and cut him in the bind over the face with crossed hands, between the sword and the man. Or cut him with the sword in the head. |

Daß dupliern Item wann du in mitt dem zorn haw° / oder sunst oben eÿn haw~st verseczt er dir mit stöck So stos /In des/ deines schwerts knopff vnder deine~ rechte~ arm mitt der lincken hand vñ schlach in mitt gecruczten henden am schwert hinder sines schwerts cli klingen zwischen de~ schwert Vñ dem mann vff durch daß maul Oder schlach im mit dem stück vff den kopff ~ |

Das dupliernn. Merck wenn du Im mit dem Zornhaw, oder sonst oben in hawest, versetzt er dir nit starck, So stos |

|||||

[25] Mutating. When you bind against his sword with an Oberhau or something similar, so wind the short edge against his sword and go up in an orderly fashion with the arms; and hang your sword blade over his sword on the outside and thrust into him through the lower openings. This can be done on both sides. |

Mörck daß mutiern [24v] Daß mutiern treÿb also. Wenn du im mitt dem obern haw° ode~ sunst an daß schwert bindest So winde die kun kurcze~ schnide~ an sin schwert vñ far wol vff mit den armen vñ heng im dein schwerczs ? clingen vssen über sein schwert vñ stich v im zu° der vndern blösse vñ dz trÿb zu° baÿden sÿtten ~ |

||||||

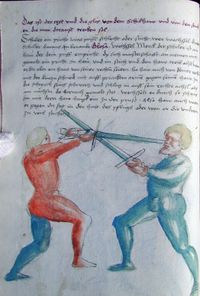

[26] Do the Krumphau (crooked strike) with these techniques.

Glosa This is how you shall strike the Krumphau against the hands. When he cuts from his right side against an opening with an Oberhau or Underhau, take a spring away from the strike with your right foot, far out to his left side; and cut with crossed arms with the point to the hands. And even try this technique against him when he stands against you in the Ox guard. |

Der krumphaw° mitt sine~ stüken stucken Krump vff behende / Glosa Daß ist wie du krump solt haw°en zu° den henden vñ daß stuck trÿb also wenn er dir von deine~ recht~ sÿtten mitt aine~ obern ode~ vndern haw~ zu° der blöss haw~et So [25r] spring vsß dem haw° mitt dinem recht~ fu°ß gege~ im wol vff sin Lincke sÿtten vñ schlach in mit gecrüczenten arme~ mitt dem ort vff die hende vñ dz stuck trÿb och gem [!] im wenn er gen dir stätt staut In der hüt deß ochsen ~ |

[18v] wend do mit krieg man den vchsen vnd auch den eber vnd den unter haulb tribe also Wan du mit dem zu vechten zu dem man kümpst stett er dan gegen dir vnd helt sin schwertt vor dem kopff in der hut des vchsen vff siner lincken siten so setz den lincken fus fur vnd halt din messer schwert an diner rechten achselln in der hut vnd vß der hůt spring mit dem rechten fus [19r] wol vff die rechten siten vnd schlag in mit der langen schniden vß gekrutzten armen vber sin hende ~[11] | |||||

[27] Another technique from the Krumphau.

Glosa This is how you shall set aside all Oberhau attacks with the Krumphau. When he cuts in from above against your openings from his right side, step with your right foot out to his left side and throw your blade across his sword with the point to the ground in the Barrier guard. Test this on both sides. And from this setting aside you can cut him in the head. |

Aber ain stuck vß dem krumphaw° Krump wer wol seczet Glosa Daß ist wie du mitt dem komp krump haw° die obern häw abseczen solt daß stuck trÿb also Wann er dir von sÿme sine~ rechten sÿtten oben ein hawet zu° der blosß so schrÿt mitt dem rechten fu°ß vff sÿn lincke sÿten v~ber sin schwert / mit dem ort [25v] vff die erden In die schranckhüte dz trÿb zu° baÿden sÿtten Och magstu In vß dem abseczen vff dz haupt schlachen ~ |

||||||

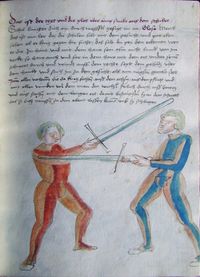

[28] Another technique from the Krumphau.

Glosa When you want to weak a master, use this technique: when he cuts in against you from above from his right side, strike crookedly with crossed hands against his cut above the sword. |

Aber ain stuck vsß dem krumhaw° Haw krump zu° den flechen / Glosa Daß ist Wenn du aine~ maiste~ schwechen wilt So trÿb dz stuck also weñ er dir oben einhawt võ sine~ rechten sÿtten So haw~ kru~ mit gekreucztem gekrentzten hende~ gege~ sime sine~ haw vff sin schwert ~ |

||||||

[29] Another technique from the Krumphau.

Glosa When you cut a Krumphau onto his sword, so cut immediately back up from the sword with the short edge, in and down from above onto his head. Or wind the Krumphau with the short edge against his sword and thrust into his breast. |

Aber ain stuck vß dem krumhaw° Wenn es kluczt oben / Glosa Dast ist wenn du im mitt dem krumphaw~ vff sin schwert hawst So schlache vom schwert mitt de~ kurczen schnide~ [26r] bald wider vff / im oben ein zu° dem kopff Oder windt Im mitt dem krumphaw° die kurczen schnÿden an sin schwert vñ stich im zu° der brust ~ ~ |

||||||

[30] Another technique from the Krumphau.

Glosa When he wants to cut in from his right shoulder, pretend that you want to bind against his sword with a Krumphau. Cut short; and go through with the point under his sword and wind your hilt to your right side over your head, and stab him in the face. |

Aber ain stuck vß dem krumphaw° Krum nicht kurcz haw° / Glosa Das ist wenn er dir von siner rechten achseln oben ein will howen So tu° alß ob du mitt dem krumphaw° an sin schwert wöllest binden Vnnd kurcz vnd far mitt dem ort vnde~ sn sine~ schwert durch vnd wind vff din rechte sÿttenn dein gehülcz über din höppt vnd stich im zu° dem gesicht ~ ~ |

[10r] oben In wilt hawenn, so thu als du Im mit dem krumphaw ann sein schwert wollest winden, vnd haw kurtz vnnd far mit dem ort vnter seinem schwertt durch, vnnd wind auf dein recht seit deinẽ gehiltz vber dein haupt, vnnd stich im zu dem gesicht, als hie gemalt stet, vnd das stuck bricht die. |

|||||

[31] How one should counter the Krumphau.

Glosa When you cut against him from above or from below, from your right side; if he also cuts crookedly from him right side with crossed arms to your sword and thus foils your strike, so bind strongly with your sword. And shoot your point against his breast under the long edge of his sword. |

Mörck wie man den krumphaw° brechen sol ~ [26v] Krump wer dich Irret / Glosa Daß ist Wann du im von diner rechten sÿtten ober ode~ vnden zu° haw~est Hawt er dann och von sÿner rechten sÿtten mit gekreutzen armen krump vff din schwert Vñ verir°et dir do mitt dein hew~ So blÿb mitt dine~ schwert starck an dem sine~ Vnnd schüß im vnde~ dem schwert den ort lang ein zu° der brust etc~ |

||||||

[32] Another counter against the Krumphau. When you cut in against him from above from your right side and he also cuts crookedly from his right side with crossed arms onto your sword and thus presses it down towards the ground, wind towards your right side; go with your arms up over your head. And thrust with your point from above against his breast. Glosa If he defends himself against this, stand with your hilt in front of your head, and work deftly with the point from one opening to the other, this is called "the Noble War." With this you will confuse him so totally that truthfully he will not know where he will find himself. |

Ain andern brüch über den krumphaw° ~~ Mörck wenn du im von diner rechten sÿtten oben ein hawst Hawt er deñ och võ sine~ recht~ sÿtten mit gekrenczten armen komp [12] [27r] Vff dein schwert vnd drückt dir das da mit vnder sich gen der erden So wind ge deiner rechten syte~ vnd far mit den arme~ wol vff v~ber dein hau°pt vnd secze Im dein ort obe~ an dei die brust Glosa Versetzt er dir das so plÿb also sten mit dem gehu~lcz vo° dem hau~pt vnd arbait behendtlich mit dem ort von aine~ bloß zu° der andere~ Das hayset der edel krig Da mit verwirstü In so gar Das er nit waysst wo er vor dir blibe~ sol fur war |

Aber ein bruch wider den krumphaw. Merck wenn du Im den ort vnter seinẽ schwert ein scheust zu seiner brust, als vor geschriben vnd gemalt stet, druckt er dann mit dem krumphaw dein schwert vntersich zu der erdenn, So wind gen deiner rechtenn seittenn, vnnd far mit dem Arm wol auf vber dein haupt, vnd setz im den ort oben an die brust, Als hernach gemalt ist, versetzt er dir das, so beleib also stehenn mit dem gehiltz, vor dem haupt, vnd arbayt behentlich mit dem ort, vonn einer bloß zu der andernn, das heist der odel krieg, damit verwirrest du Inn so gar, das er nicht weis, wo er vor dir beleybenn sol. |

[20v] Item ein bruch wider den krümpt haulb so du im den ortt vnter sin schwertt in schuest zu siner brust druck er dan mit dem krümpt haulb din schwertt vnter sich zu der andern erden so wind gegen siner rechten siten vnd far mit dem arm woll vff vber dem hauptt vnd setz im den ortt oben an sin brust versetz er dir dz so pleib also stett mit dem gehultz vor dem hauptt vnd arbeitt behendeglich mit dem ort von eÿner plos zu der andern dz [21r] heist der krieg do mit verirrest In so gar dz er nit weiß wo er sich hutten soll ~ [13] | ||||

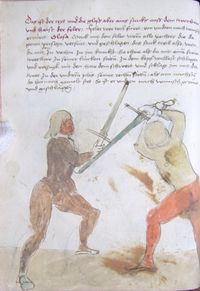

[33] Do the Zwerchau (crosswise strike) with these techniques.

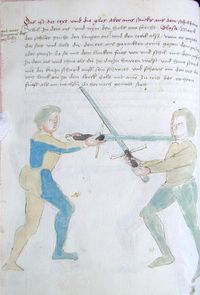

Glosa The Zwerchau counters all strikes that cut down from above. When he cuts in from above against your head, spring with the right foot against him away from the cut, out to his left side. And as you spring turn your sword—with the hilt high in front of your head, so that your thumb comes under—and cut him with the short edge against his left side. So you catch his strike with your hilt and strike him in the head. |

Der zwerhaw° mit sine~ stucken Zwerch benÿmp Glosa Merck de~ zwerhaw bricht alle hew die võ oben nÿder gehawe~ werde~ vnd den haw trÿb also We~ er dir oben In hawet zu° dem kopf So spring mit dem rechte~ fu°ß [27v] gen Im vß dem hawe Vff Sin lincken sytten vnd im springen verwent din schwert mit de~ gehu~ltz houch vor deine~ haupt das din dou~m vnnde~ kome vmd [!] schlach In mit der kurtze~ schnide~ zu° siner lincken sytten So vaschdü sine~ haw In din gehu~ltz vnd triffest In zu° dem kopff ~~ |

Der Twer haw. + Twer benimpt, Glosa. Merck denn Twer haw pricht alle hew, die vonn obenn nider gehawenn werden, vnnd denn haw treib also, Stehe mit dem linckenn fus vor, vnnd halt dein schwert an deiner rechtenn Achsel, vnnd [10v] wann er dir obenn inhawet zu dem kopf, so spring mit dem rechtenn fus gen Im wol aus dem haw auf sein lincke seittenn, vnnd im springenn verwendt dein schwerd mit dem gehiltz, hoch vor deinem haupt, das dein dawme vnden komme, vnd schlag in mit der kurtzenn schneidenn, zu seiner linckenn seytten, fechstu seinen haw in dem gehiltz, vnnd truckst in zu dem kopf, als hie gemalt ist. |

|||||

[34] A technique from the Zwerchau.

Glosa This is how you shall work with the "strong" from the Zwerchau. When you cut against him with the Zwerchau, think that you shall strike powerfully with the sword's "strong" against his. Hold him thus strongly in the bind then cut with crossed arms behind his sword blade, from above against the head, or cut him with the sword to the face. |

[27v] Ain stuck vß dem zwerhaw° Zwer mit der stoerck Glosa Das ist wie dü mit der stoerck auss der zwer arbaite~ solt vnd dem thu°n also / we~ dü Im mit der zwer zu° hauest So gedenck das dü Im mit der zwer sterck deines schwerts starck In das Sin Helt den er starck wyder So schlach In am schwert mit gekrütte~ gekru~czte~ arme~ hinder seines schwertz klinge~ vff den kopff [28r] oder schnÿd In mit dem stuck dürch das mau°l ~~ |

Ein stuck aus dem Twerhaw. Twer mit der sterck, Glosa. Das ist, wie du mit sterck aus der Twer arbaittenn solt, vnnd den thu also, wen du Im mit dem Twer zu hawest, So gedenck das du Im mit der sterck deines schwerts starck windest an das sein, helt er dann stark wider, so schlag in am schwert mit gecreutztenn Armen hin seines schwerts klingenn auf denn kopff, als hie ist gemacht, oder schneid im mit dem stuck durchs maul. |

|||||

[35] Another technique from the Zwerchau. When you bind against his sword from the Zwerchau with your sword's "Strong"; hold him strongly, then push his sword away from you with your hilt, down and out to your right side, and strike immediately round with the Zwerchau against his right side, against the head. |

aber ain stuck vß dem zwerhaw° Merck we~ du Im vß der zwer mit der stoerck deines schwerts an sin Schwert bindest helt den er starck wÿder So stoss mit deine~ gehülcz sin schwert võ dir vnderisch vff dein rechte~ sytte~ vnd schlach bald mit der zwer wyderu~ gen siner rechte~ syten Im zu° dem kopffe ~ |

Aber ein stuck auf dem Twerhaw. Merck wenn du im auß dem Twer mit der sterck deines schwerts ann sein schwert bindest, halt er dann starck bey dir, so stoß mit deinem gehiltz sein schwert vonn dir vntersich, auf dein rechte seyttenn, als hie gemalt stet, vnnd schlag balde mit [11r] der Twer wider vmb genn seiner rechtenn seyttenn im zu dem kopff. |

|||||

[36] Another technique from the Zwerchau. When you bind against his sword with the Zwerchau, if he is weak in the bind, so lay the short edge against the right side of his neck and spring with the right foot behind his left; and pull him over it with the sword. |

Aber/ain stuck vß dem zwerhaw° Itm~ wan dü Im mit der zwer an sin schwert bindest Ist da er waich am schwert So leg Im die kurtze~ schnÿde~ zu° seine~ rechte~ sytten an den halß vnd spring mit dem rechte~ fu°ß hinder seine~ lincke~ vnd ru~cke In mit dem schwert daru~ber ~etc~ |

||||||

[37] Another technique When you bind against his sword with the Zwerchau, if he is weak in the bind, so press down on his sword with the Zwerchau; and lay the short edge behind his arms in front of his neck. |

Ain ander stuck [28v] Itm~ wen dü Im mit der zwer an sin schwert bindest Ist er dan waich am schwert So truck mit der zwer sin schwert nÿde° vnd leg Im die kurtze~ schnÿde~ hinde~ sinen arme~ vorne~ an den halß |

||||||

[38] A counter against the upper Zwerchau. When you bind against his sword from the right side with an Oberhau or similar attack, if he strikes round with the Zwerchau against your other side, do the same back to him, throw a Zwerchau under his sword against his neck. |

ain bruch wider den obern zwerhaw° Itm~ wã dü Im võ deiner rechte~ sytte~ mit aine~ obere~ haw / ode~ sunst an sin schwert bindest Schlecht er dan mit der zwer vmb dir zu° der andere~ sytten so kom vor au~ch mit der zwerch vnder sin schwert Im an den halß ~~ |

[01r] Hie merck den pruch der wider den õbern twer haw Merck wen du im von deiner reichtn seittñ mit ainem ober haw oder sunst an sein schwert pindest / schlecht er dan mit der twer vmb / dir zu der andern seittñ / so kum vor auch mit der twer vndter seinem schwert im an den hals / als am nãchstn hernach gemalt stett / so schlecht er sich selber mit deinem schwert / |

Ein bruch wider den ober Twer haw. Merck wenn du im von deiner rechtenn seytten, mit einem oberhaw, oder sonnst ann sein schwert windest, schlecht er denn mit dem mit der Twer vmb dir zu der anndernn seittenn, so kum vor auch mit der Twer vnter seinem schwert im an den hals als hie stet gemalt. |

[21v] Item ein bruch wider den zwerch ober haulb so du Im von diner rechten siten mit eynen ober haulb an sin schwertt bindest schlecht er mit der zwierch vmb sich so küm auch vor mit dem zwerch haulb vnter sin schwertt an den hals ~ [14] | |||

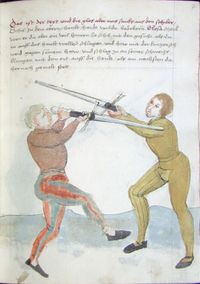

[39] Here mark the breaking of the lower Cross Strikes Mark if you bind at his sword from your right side and he strikes out of the binding across to the other opening of your right side, so stay with your hilt-guard over your head and reverse your sword's blade downwards at his strike, and thrust at his lower opening, as painted here next. |

[01v] Hie merck den pruch wider die vnderñ twer schleg / Merck / wen du im von deiner rechtñ seittñ an sein schwert pindest / schlecht er dan vom schwert vmb mit der twer dir zu der andern plõs deiner rechtñ seittñ / so pleib mit deinem gehiltz vber deinem haubt / vnd verwendt dein schwertz kling vndter sich gegen seinem haw / vnd stich im zu der vndtern plõs / als am nachstñ hernach gemalt stet / |

Ein stuck wider ein vnter Twerhaw. Merck wenn du Im vonn deiner rechtenn seyttenn ann sein schwert windest mit einem oberhaw, schlecht er dann vom schwert vmb mit der Twer dir zu der vnternn bloß deiner rechtenn seittenn, So beleib mit deinem gehiltz ober deinem haupt, vnd verwẽdt dein schwert clingenn vntersich gen seinem haw, vnnd stich im zu der vntern bloß als hie gemalt stet. |

|||||

[40] How one shall strike against the four openings with the Zwerchau.

Glosa This is how you shall strike against the four openings with the Zwerchau when you go against someone. When you come against him in Zufechten; when it becomes suitable for you, spring against him and cut with the Zwerchau against the lower opening on his left side. This is called "to strike against the plough". |

Wie man zu° den vier blossen mitt der zwer schlache~ soll Zwer zu° dem pflu°g / Glosa das ist wie dü In aine~ zu° gang [29r] mit der zwer zu° den vier blossen schlagen solt Das vernÿm also Wã dü mit dem zu°fechte~ zu° Im kompst So merck wan es dir eben ist So spring zu° Im vnd schlag In mit der zwer zu° der vndere~ bloß siner lincken sytte~ Das hayst zu° dem pflu°g geschlagen ~ |

[02r] Das ist der text vnd die glõß wie man mit der twer zu den vier plõssn schlachen sol / Twer zu dem pflueg / Glosa / das ist wie du in ainem zu gang mit der twer zu allen vier plõsn schlachen solt / das vernym also / wen du mit dem zu fechtn zu im kumbst / So merck wen es dir eben ist so spring zu im / vnd schlag im mit der twer zu der vndterñ plõs seiner lincken seittñ / als am nechstn gemalt stet / das haist zu dem pflug geschlagen / |

|||||

[41] Another technique from the Zwerchau. When you have cut against the lower opening with the Zwerchau, so strike immediately with the Zwerchau against the other side upwards into the head. This is called "to strike against the ox". And continue to strike quickly a Zwerchau against the ochs and another against the plough, crosswise from one side to the other. And cut him after with an Oberhau in against the head and thus draw yourself back from him. |

Aber ain stuck vß dem zwerhaw° Wen dü Im mit der zwer zu° der vndere~ bloß geschlagen hast so schlag bald vff mit der zwer Im zu° der andere~ sytten oben In zu° dem kopff das haisst zu de~ ochse~ geschlage~ vnd schlach denn fürbas behendtlich ainen zwerch schlag zu° dem ochse~ vnd den andere~ zu° dem pflug cru~czwÿß võ ainer sytte~ zu der andere~ vnd haw Im do mit aine~ obere~ haw obe~ ein zu° dem kopffe vnd zu~ch dich damit ab ~ |

[02v] Aber ein stuck auß dem twer haw / Merck / wen du im mit der twer zu der vndterñ plõss geschlagen hast / als vor am nãchstn gemalt stet / so schlag pald auff mit der twer im zu der anderñ seittñ oben ein zu dem kopf / das haist zu dem ochssen geschlagen / vnd schlag den fu~rbas behentlich albeg ainen twer schlag zu dem ochsn / vnd den andern zu dem pflu~eg / creu~tz weis von ainer seittñ zu der andern / vnd haw im ein ober haw oben ein zu dem kopf / vnd zeuch dich damit ab / |

|||||

[42] This is the text and the teaching thereof.

That is to say, that in all of your Zwerchau strikes you shall take a proper spring out to the side where you want to strike him. So you can strike him well in the head. And see to it in the spring that you are properly protected from above with your hilt above and in front of your head. |

[29v] Waß sich wol zwerch Glosa das ist das dü mit ainem yden zwerschlage wol vß solt springe~ Im vff die sytte~ / do dü Im zu° schlage~ wylt so mag stü In wol treffe~ zu° siene~ haupt vnd wart das dü In dem spru~ng oben vor dine~ haupt mit diene~ gehu~ltze~ vol bedeck sÿest |

[03r] Das ist der text vnd ein ler dau~on Was sich wol twer / Glosa das ist / das du mit einem yeden twer schlag wol auß solst springen / Im auff die seittñ do du im zu schlagen wild / So magstu in wol zu dem haubt treffen / vnd wart das du in dem oben / vor deinem haupt mit dem gehiltz wol bedeckest seiest / |

|||||

[43] A further technique from the Zwerchau, and it is called the feint (Feler).

Glosa With the feint all fencers who quickly leap to the defence are mislead and defeated. When you come against him in Zufechten, pretend that you want to cut him with perhaps an Oberhau to his left side. In this manner you can strike him underneath however you want and defeat him. |

Hie nach mörck aber ain stuck vß der zwer vñ das haÿsset der feler Feler wer wol furet Glosa Das ist mit dem feler werde~ alle fechter die da gern fersetze~ ver fyrt vnd geschlache~ das stuck trib also Wã du mit dem zu° fechte~ zu° Im kompst So thu° alß ob dü In mit aine~ fryen ober haw zu° siner lincke~ sÿtte~ So ist er vnnde~ nach [30r] wu°nsch geru~ret vnd geschlage~ |

[03v] Das ist der text vnd die gloß aber ains stucks auß dem twerhaw vnd haist der feler / Feler wer wol fu~ret / Glosa Merck mit dem feler werñ alle vechter die da geren versetzn verfu~rt vnd geschlagen / das stuck treib also / wen du mit dem zu vechtn zu im kumbst / So thue als du mit eine~ freien twerhaw zu seiner lincken seittñ zu dem kopf wellest schlagen vnd verzugk mit dem haw dein schwert vnd schlag im mit der twer zu der vndterñ plõs / seiner rechtñ seittñ / als am nachstñ da hernach gemalt stet / So ist er vndten nach wunsch geru~rt vnd geschlagen / |

Das ist aber ein stuck aus der Twer das heist der Feler. Feler wer furet, Glosa. Merck mit dem feler werenn al fechter die do gernn versetzenn verfurt vnnd geschlagen, das stuck treib also, wen du mit dem zu fechtenn zu Im kombst, So thu als du in mit einem [11v] freyenn oberhaw zu seiner linckenn seitten zu dem kopff wollest schlagenn, vnnd wend mit dem haw dein schwert, vnnd schlag in mit der Twer, zu der vndern bloß seiner rechtenn seyttenn oder linckenn als hie gemalet stet, so ist er vnten nach wunsch gerurt vnnd geschlagenn. |

||||

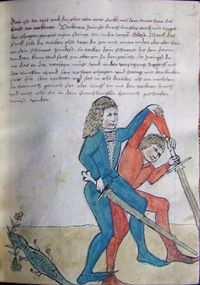

[44] Another technique from the Zwerchau, and it is called the turner (Verkehrer).

Glosa When you bind against his sword with an Oberhau or Underhau, turn your sword so that your thumb comes underneath, and thrust him down from above into the face. In this way you force him to defend himself. And in the defence, grip his right elbow with your left hand and spring with your left foot in front of his right, and stab him over it. Or use the turner to rush through and grapple, in the same way that you will be told for running through. |

aber ain stuck vsß dem zwerhaw° vnd daß haÿsst der verkerer ~~ Verkerer zwinget Glosa Merck das stu~ck soltü also trÿbere~ wen dü In mit aine~ vnde~ oder oben haw an sin schwert bindest So verker dein schwert das din dou~me vnde kome vnd stich Im obe~ In zu° de~ gesichte So zwingstu In das er dir versetze~ mu°ß Vnd In der verseczung begriff mit de~ lincken hand sin rechte~ eleboge~ vnd spring mit dem lincken fu°sse für sine~ rechte~ vnd stosß In also dariber / Oder lauff In mit dem verkerrer durch vnd ringe / alß dü In dem durch lauffen her nach wirst finde~ |

[04r] Das ist der text vnd die glos aber ains stucks aus dem twerhaw das haist der verkerer / Verkerere zwinget Glosa / Merck das stuck solt du treiben also / Wen du im mit ainem vndter oder ober haw an sein schwert pindest / so verker dein schwert das dein dawm vndten kum vnd stich im oben ein zu dem gesicht / So zwingst du in das er dir versetzn mu°ß / vnd in der versatzung Begreiff mit der lincken hand sein rechten elpogen / vnd spring mit dem lincken / fues fu~r sein rechten / vnd stos in also daru~ber / als am nãchsten da hernach gemalt stet / oder lauff im mit dem verkerer durch vnd ring / als du in dem durchlauffen hernach geschriben wirst vinden / |

|||||

[45] Another technique from the feint.

Glosa This is called the double feint, because in the Zufechten you shall be misleading two times. Do the first like this: when you come against him in Zufechten, take a spring with the foot against him and pretend that you will cut with a Zwerchau against the left side of his head. And change the direction of the cut, to the right side of his head. |

[30v] Aber ain stuck von aine~ feler Feler zwÿfach Glosa Merck das haysst der zwÿfach feler darümbe das mã In aine~ zu° fechte~ zwaÿerlaÿ ferfÿrung daru~ß trÿbe~ sol die erste~ tryb also we~ dü mit dem zu° fechte~ zu° Im kompst So spring mit dem fu°ß ge~ Im vnd thu°n alß dü Im mit aine~ zwer schlage~ zu° siner lincken sÿtten zu° dem kopff schlage~ welest vnd ferzu~ck den schlag Im zu° siner rechte~ sÿtten an de~ kopff ~~ |

[04v] Das ist der text vnd die glos aber von ainem feler Veler zwifach / Glosa Merck das haist der zwifach veler / daru~b das man in ainem zu vechtñ zwayerlay verfu~rung darauß treiben sol / die erst treib also / wen du mit dem zu vechtñ zu im kumbst / so spring mit dem rechtñ fu~es gegen im vnd thue als du im mit einem zwerschlag zu seiner lincken zu dem kopf schlagen welst / vnd verzuck den schlag vnd schlag in zu seiner rechtn seittn an den kopf / als am nãchstn da hernach gemalt stett / |

|||||

[46] Another technique from the feint.

Glosa That is to say, when you have struck to the right side of his head with the first misleading—about which has just been written—so strike immediately round to the other side of the head, and go with the short edge with outstretched crossed arms over his sword: and "Imlincke", that is to say on the left side, and cut in with the long edge over the face. |

Aber ain stuck vß dem feler Zwyfach es fyrbas Glosa Das ist wã dü Im mit der erste~ verfÿrunge zu° siner rechten sytte~ zu° dem kepff geschlage~ [31r] hau~st / alß am neste~ gemelt ist So schlach bald wyderu~mb Im zu° der rechte~ sytte~ zu° dem kopff vnd far mit der kurtze~ schnÿde~ mit auß gecru~tzten arme~ v~ber sin schwert vnd spring Imlincke das ist auff dein lincke~ sÿtte~ vnd schnyd In mit der lange~ schnÿde~ durch das maul ~~ |

[05r] Das ist der text vnd glos aber ains stucks aus dem feler / Zwifach es fu~rbaß / Glosa / Das ist wen du in mit der erstñ verfu~ru~g zu seiner rechtñ seittñ zu dem kopf geschlagen hast / als vor am nachstn gemalt stet so nym damit den schnit vndten in sein arm~ / vnd schlag pald widerumb im zu der lincken seittñ zu dem kopf / vnd far mit der kurtzn schneid auß gekreutznt arme~ vber sein schwert vnd spring im linck das ist auf sein lincke seitt / vnd schneid in mit der langen schneid durch das maul / als da gemalt stet / |

|||||

[47] Do the Schielhau (squinting strike) with these techniques.

Glosa The Schielhau is a strike which counters cuts and thrusts from the buffalos—those who take their mastery through violent strength. Do the strike like this: when he cuts in against you from his right side, you should also cut from your right side with the short edge with the arms outstretched against his cut, against the "weak" of his sword and cut him on his right shoulder. If he changes through, shoot in with the cut, long edge against the breast. And you can also strike this, when he stands against you in the Plough guard [Pflug] or when he wants to thrust into you from below. |

Der schilhaw° mitt sine~ stucken Schiller ein bricht Glosa Hie merck Der schiller ist ain haw der dem buffle~ buffeln die sich maysterschafft an nem~e~ mit gwalt In bricht In hawe~ vnd steche~ vnd da den haw trÿb also Wã er dir obe~ ein hawet [31v] võ siner rechte~ sytte~ So haw och võ dener rechte~ sytte~ mit der kurtze~ schnÿde~ mit vff gerechte~ arme~ ge sine~ hawe In die schwech sinenes schwerts vnd schlag In vff sine~ rechte~ achsel Wechselt er du~rch So schyß In mit dem hawe lang In zu° der bru~st vnd also haw aoch wan er gen dir stat In der hu~tte de pflu~gs Oder we~ er dir vnde~ s zu° wyll steche~ |

[05v] Das ist der text vnd die glõs von dem Schilhaw vnd von den stucken die man darauß treiben sol / Schiler ein pricht Glosa / Wechssel Merck der schiler ist ain haw der dem pu~ff einpricht dy sich maisterschafft an nemen mit gewalt ein pricht in hew vnd in stich vnd den haw treib also / Wen er dir oben ein haut von seiner rechtñ seitten / So haw auch von deiner[15] rechtñ mit der kurtzn schneid mit auff gerackten arme~ gegen seine~ haw in die schwech seins schwertz vnd schlag in auff sein rechte achsl / als am nãchstn da hernach gemalt stet / wechsselt er durch so scheu~s im mit dem haw langk ein zu der prust / Also haw auch wen er gegen dir stet in der hutt des pflu~gs / oder wen er dir vndten zu wil stechen / |

Das ist der Schilhaw mit seinẽ stucken. + Schilherein [sic] pricht, Glosa. Merck der Schilher ist ein haw, der denn Pufflen die sich meisterschafft an nemen, mit gewalt ein pricht in hawenn vnnd in stechenn, den haw treib also, wenn er dir obenn ein hawt von seiner rechtenn seyttenn, so haw auch von deiner rechtenn, mit der kurtzen schneid, gegenn seinem haw, also schlechstu vnnd versetzt miteinander, vnnd trifst in mit dem hew, als hie gemalt stet. |

||||

[48] Another technique from the Schielhau.

Glosa This is a lesson: you shall search with the look and notice carefully, if he fights close to you. This you shall mark when he cuts against you and his arm does not stretch out in the cut, so you will strike too. And in the strike go with the point under his blade to the other side, and thrust in against the face. |

Aber ain stuck vß dem schill~ Schill kurßt er dich an Glosa Merck das ist ain lerre Das schillern solt mit dem gesichte vnd gar ebe~ seche~ ober kurtz gen dir vicht Das solt bÿ de~ erkene~ wã er dir zu° hawet vnd sin arm mit dem haw nicht lanck streckt So haw / [32r] och Vnd far In dem haw mit dem ort vnder seine~ schwert du~rch vnd stiche In zu° de~ gesicht ~~ |

[06r] Das ist der text vnd die glos aber ains stucks aus dem schiler / Schil kurtzt er dich an / Glosa Merck das ist ain ler daz du schilen solt mit dem gesicht / vnd gar eben sehen ob er kurtz gegen dir ficht / das solt du pey dem erkennen / wen er dir zu haut vnd mit dem haw sein arm~ nicht lanck von im reckt / so haw auch vnd far in dem haw mit dem ort vndter seine~ schwert durch vnd windt auff dein rechte seytt dein gehiltz vber dein hau~bt vnd stich im zu dem gesicht / als am nãgstñ gemalt stett / |

|||||

Itm~ allen vechterñ die da kurtz fechtñ / auß dem ochsn / aus dem pflueg / vnd mit allen winden vor dem man / den wechsl frõlich durch / auß hawen vnd aüs stechñ mit dem langen ort / damit bestengistu~ (?) sy an dem schwert das sy dich mu~essñ zu dem abent lassen kume~ / vnd sy schlagen |

|||||||

[49] Another technique from the Schielhau.

Glosa Mark well; to strike the Schielhau breaks the long point; and then do this: when he stands against you and holds the point with outstretched arms towards the face or chest, so stand with the left foot forward and search with the gaze against the point, and pretend as if you want to strike against the point; and strike powerfully with the short edge above his sword, and thrust with the point along with the blade against the neck with a step towards him with the right foot. |

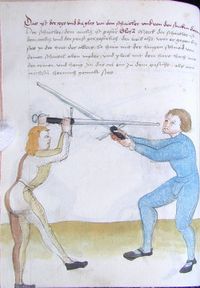

Abe~ ain stuck uß dem schillhaw° Schill zu° dem ort Glosa Merck der schiller bricht den lange~ ort vnd den tryb also we~ er ge dir stat vnd helt dir den ort usß gerachte~ arme~ ge~ dem gesÿchte oder der bru~st So stand mit de~ lincke~ fu°sß fu~r / Vnd schill mit de~ gesicht zu° dem ort vnd thu°n alß dü Im zu° dem ort hawe~ welest Vnd haw starck mit der kurtze~ schnÿde~ vff sin schwert vnd schu~ß Im den ort / darmit lang In zu° dem halß mit aine~ zu°trytt des rechte~ fu°ß ~:etc~ |

[06v] Das ist der text vnd die glos / Aber ains stucks aus dem schilhaw Schil zu dem ort / Glosa / Merck der schiler pricht den langen ort‡ vnd den treib also / wen er gegen dir stett vnd helt dir den ort aus gerackten arme~ gegen dem gesicht oder prust / So ste mit dem lincken fu~es vor vnd schil mit dem gesicht zu dem ort / vnd thue als du~ Im darzu hawen welst / vnd haw starck mit der kurtzn schneid auff sein schwert vnd schews im den ort da mit lanck ein zu dem lanck hals / mit aine~ zu tritt des rechten fu~eß / als am nãchstñ da hernach gemalt stett ^‡ mit ainer betrugnus des gesichtz |

Aber ein stuck aus dem Schilher. Schilh zu dem ort, Glosa. Merck der Schilher pricht denn langenn ort, vnnd denn treib also. Wenn er gegenn dir stehet, vnnd helt dir denn ort aus gerechten armenn gegenn dem gesicht, oder gegen der brust, [12r] so stehe mit dem linckenn fus vor, vnnd schilh, mit dem gesicht, vnnd thu als du im zu dem ort wollest hawenn Vnnd haw starck, mit der kurtzenn schneid auff sein schwert, vnnd schewß im denn ort, damit langkem zu dem hals, mit einem zu trit des rechten fuß. |

||||

[50] Another technique from the Schielhau.

Glosa When he wants to cut in against you from above, so search with the gaze as if you want to hit him above the head. And strike with the short edge against his cut, and strike along his blade with the point onto the hands. |

[32v] Aber ain stuck vß de~ schillhaw° Schill zu° dem obere~ Glosa Merck we~ er dir oben will In hawe~ So schill mit de~ gesicht alß dü In vff das haupt wylt schlage~ Vnd n haw mit de° kurtze~ schnÿde~ ge~ sine~ haw Vnd schlag In an siner schwertz klinge~ mit dem ort vff die hend ~~ |

[07r] Das ist der text vnd die glos aber ains stucks aus dem schiler / Schil zu dem obern / Glosa Merck Wen er dir oben ein wil hawen / So schil mit dem gesicht / als du in auff das haubt wellest schlagen / vnd haw mit der kurtzen schneid gegen seinem haw / vnd schlag in an seiner schwertzs klingen mit dem ort auff die hendt / als am nãchsten da hernach gemalt stett / |

|||||

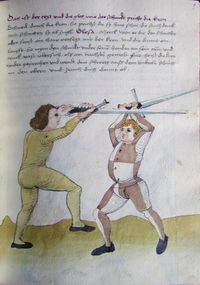

[51] Do the Scheitelhau (the parting strike) with these techniques.

The parter is dangerous for the face and the breast. When he stands against you in the fool's guard [Alber], cut with the long edge from the "long parting" from above and down; and keep the arms high in the cut, and hang with the point in against the face. |

Der schaÿteler mitt sine~ stucken Der schaytler / Glosa Hie merck der schaÿtler ist dem antlÿtz vnd der bru~st gefaerlich den tryb also We~ er gen dir stat In der hu°t aulber So haw mit der langen schnÿde võ der lange schaÿttlen obe~ nÿder vnd belÿb [33r] mit dem haw hoch mit de~ arme~ vnd heng Im mit de~ ort ein zu° dem gesÿchte |

[07v] Das ist der text vnd die glos von dem schaittler / vnd von den stucken daraus Der schaittler / Glosa Merck der schaittler ist dem antlitz vnd der prust gar gefãrlich / den treib also / wen er gegen dir stett in der huet des albers / So haw mit der langen schneid von deiner schaittel oben nyder / vnd pleib mit dem haw hoch mit den armen / vnd heng im das ort ein zu dem gesicht / als am nãchstñ hernach gemalt stett / |

Das ist der Schatler mit seinen stucken. Der Schatler Glosa. Merck denn Schaytler treyb also, Haw mit der langenn schneydt, oben nider vonn deiner Schaytel, Im zu dem kopff, versetzt er, so heng im denn ort, mit der langenn schneid, vber sein gehiltz, vnnd stich im zu dem gesicht, als hie gemalt stet. |

||||

[52] A technique from the parter.

Glosa When you cut from above with the Scheitelhau and hang your point in his face, if he defends himself against your point by pushing it up and away with the hilt, then turn your sword with the hilt high in front of your head and stab him downwards into the chest. |

Ain stuck vß dem schaiteler Mit siner ker / Glosa das ist wen dü Im den ort mit dem schaitler oben ein hengst zu° dem gesicht Stost er dich dir denn den ort In der versatzu~ng mit dem gehu~ltz vascht yber sich So verker dein schwert mit de~ gehu~ltz hoch fyr din haupt vnd setz Im den ort vnde~ an die brust etc |

[08r] Aber ain stuck aüs dem schaittler

Itm~ versetzt er dir mit dem gehu~ltz vast vbersich den schaittler / so verker dein schwert mit dem gehu~ltz hoch fu~r dein haubt vnd setz im dein ort vndten an die prüst / als dan da gemalt stet / |

Item stost er dir denn ortt, mit seinem gehiltz fast vber sich, so verwendt dein schwert mit dem gehiltz, hoch für dein hauptt, das dein dawmen vnden kum, vnnd setz im den ort vnder seinen hendenn ann die prust, als hie gemaltt stet. |

[28v] Item merck so du im mit dem schittler oben yn haulbest vnd gehengt zu dem gesicht stost er dan mit dem gehultz den ort vast vbersich so verkere din schwertt mit dem gehultz fast vber sich fur din hauptt vnd setz im den ortt vnten an sin brust ~ [16] | |||

[53] How the Crown counters the parter.

Glosa When you cut in against him from above with the Scheitelhau, if he defends himself with the hilt over his head: this defence is called the Crown. And with that he can rush in close to you. |

Wie die kron den schaÿtler bricht Waß võ Im komp / Glosa Merck wan dü Im mit dem schaittler oben ein hawest / versetzt er mit de~ gehulcze hoch ob [33v] ob sine~ haupt Die versatzu~ng hayst die kron vnd laufft dir do mit eÿm |

[08v] Ain ander Stück |

Ein annder Stuck. Was vonn Im kumpt, Glosa. Merck wenn du Im mit dem Schaytler, obenn einhawest, versetzt er mit dem gehiltz hoch ob seinem haupt, die versatzung heist die kran, vnd laufft dir damit ein, |

||||

[54] How the slice counters the Crown.

Glosa When he defends against the Scheitelhau or some other cut with the Crown and tries to rush in against you, pull the slice under his hands in his arm and press hard upwards, to break the Crown. And turn your sword from the under slice to the over slice, and thus draw back. |

Wie der schnitt die kron bricht Schnid du~rch die krone / Glosa Merck we~ er dir den schailtler order su~nst aine~ haw vesetzt mit der kron / vnd dir da mit ein lau~fft / So nÿm de~ schnit vnder sin hende~ In sin arm Vnd tru~ck vast v~ber sich so ist die kron wyder gebroche~ Vnd wende din schwert vß de~ vndere~ schnit In den obere~ vnd zu~ch dich da mit abe |

[09r] Das ist der text vnd die glos wie der schnidt pricht die kron Schneid durch die kron / Glosa / Merck Wen er dir den schaittler oder sunst ain haw versetzt mit der kron / vnd dir damit einlaufft So nym den schnidt vnder seine~ henden an sein arm~ vnd truck vast vbersich / als am nachstñ gemalt statt / So ist die kron wider geprochen vnd wendt dein schwert auß dem vndterñ schnitt in den obern vnd zeuch dich damit ab / |

so nim denn vnternn [12v] schnit, vnder sein hendenn in sein Arm, vnnd druck fast vbersich, so ist die kron wider gebrochenn. |

[28v] Item merck wan er dir den schittler oder sünst ein haulb versetzt mit der kron vnd dir do mitt yn laufft so nym den schnitt vnder sin henden in sin arme vnd druck vast vber sich so ist die kron wol gebrochen vnd wind din schwertt in den obern schnidt vnd zuch do mit abe ~~[16] | |||

[55] The four guards.