|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Johannes Liechtenauer"

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

Liechtenauer's teachings are preserved in a brief poem of rhyming couplets called the ''Zettel'' ("Recital"). These "secret and hidden words" were intentionally cryptic, probably to prevent the uninitiated from learning the techniques they represented; they also seem to have offered a system of mnemonic devices to those who understood their significance. The Recital was treated as the core of the Art by his students, and masters such as [[Sigmund ain Ringeck]], [[Peter von Danzig zum Ingolstadt]], and [[Jud Lew]] wrote extensive [[gloss]]es that sought to clarify and expand upon these teachings. | Liechtenauer's teachings are preserved in a brief poem of rhyming couplets called the ''Zettel'' ("Recital"). These "secret and hidden words" were intentionally cryptic, probably to prevent the uninitiated from learning the techniques they represented; they also seem to have offered a system of mnemonic devices to those who understood their significance. The Recital was treated as the core of the Art by his students, and masters such as [[Sigmund ain Ringeck]], [[Peter von Danzig zum Ingolstadt]], and [[Jud Lew]] wrote extensive [[gloss]]es that sought to clarify and expand upon these teachings. | ||

| − | + | Seventenn manuscripts contain a presentation of at least one section of the Recital as a distinct (unglossed) section; there are dozens more presentations of the verse as part of one of the several glosses. The longest version of the Recital by far is found in the gloss from the [[Nuremberg Hausbuch (MS 3227a)|Nuremberg Hausbuch]], which contains almost twice as many verses as any other. However, given that the additional verses tend to either consist of repetitions from elsewhere in the Recital or use a very different style from Liechtenauer's work, they are generally treated as additions by the anonymous author or his instructor rather than being part of the standard Recital. The other surviving versions of the Recital from all periods show a high degree of consistency in both content and organization, excepting only the version attributed to Beringer (which is also included in the writings of [[Hans Folz]]). | |

| − | The following tables include only those | + | The following concordance tables include only those texts that quote Liechtenauer's Recital in an unglossed form.<ref>A fragment of the short sword is often given as a preamble to the [[short sword]] teachings of [[Martin Huntfeltz]], and the figures for the [[gloss]] of [[Jud Lew]], but those instances will not be included below and instead treated as part of said treatises.</ref> Most manuscripts present the Recital as prose, and those have had the text separated out into the original verses to offer a consistent view. For ease of use, this page breaks the general Wiktenauer rule that column format remain consistent across all tables on a page; the sheer number of Liechtenauer sources made this convention entirely unworkable, so instead the long sword table uses one layout, the mounted and short sword tables use another, and the figures use a third. |

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| Line 1,110: | Line 1,110: | ||

{{master end}} | {{master end}} | ||

| − | |||

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| title = Mounted Fencing | | title = Mounted Fencing | ||

| width = 283em | | width = 283em | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | {| class=" | + | {| class="floated master" |

|- | |- | ||

! style="width:31em;" | <p>{{rating|A}}<br/>Rome Version by [[Christian Tobler]]</p> | ! style="width:31em;" | <p>{{rating|A}}<br/>Rome Version by [[Christian Tobler]]</p> | ||

| Line 1,457: | Line 1,456: | ||

{{master end}} | {{master end}} | ||

| − | |||

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| title = Short Sword | | title = Short Sword | ||

| Line 1,618: | Line 1,616: | ||

== temp division == | == temp division == | ||

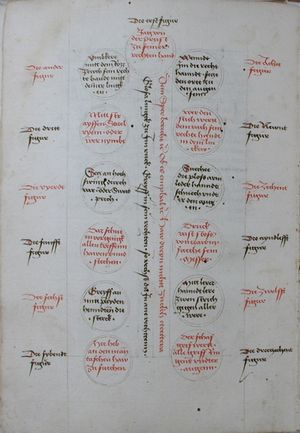

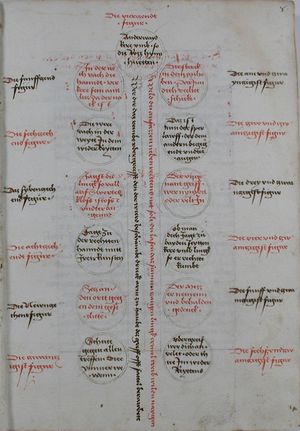

| − | In addition to the verses on mounted fencing, several treatises in the Liechtenauer tradition include a group of twenty-six ''figuren'' | + | In addition to the verses on mounted fencing, several treatises in the Liechtenauer tradition include a group of twenty-six "figures" (''figuren'')—single line abbreviations of the longer couplets, generally drawn in circles, which seem to sum up the most important points. The precise reason for the existence of these figures remains unknown, as does the reason why there are no equivalents for the armored fencing or unarmored fencing verses. |

One clue to their significance may be a parallel set of teachings first recorded by [[Andre Paurñfeyndt]] in 1516, called the "Twelve Teachings for the Beginning Fencer".<ref>[[Andre Paurñfeyndt]], et al. [[Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey (Andre Paurñfeyndt)|Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey]]. [[Hieronymus Vietor]]: Vienna, 1516.</ref> These teachings are also generally abbreviations of longer passages in the Bloßfechten, and are similarly repeated in many treatises throughout the 16th century. It may be that the figures are a mnemonic that represent the initial stage of mounted fencing instruction, and that the full verse was taught only afterward. | One clue to their significance may be a parallel set of teachings first recorded by [[Andre Paurñfeyndt]] in 1516, called the "Twelve Teachings for the Beginning Fencer".<ref>[[Andre Paurñfeyndt]], et al. [[Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey (Andre Paurñfeyndt)|Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey]]. [[Hieronymus Vietor]]: Vienna, 1516.</ref> These teachings are also generally abbreviations of longer passages in the Bloßfechten, and are similarly repeated in many treatises throughout the 16th century. It may be that the figures are a mnemonic that represent the initial stage of mounted fencing instruction, and that the full verse was taught only afterward. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| title = Figures | | title = Figures | ||

| − | | width = | + | | width = 196em |

}} | }} | ||

{| class="wikitable floated master" | {| class="wikitable floated master" | ||

| Line 1,634: | Line 1,630: | ||

! <p>[[Talhoffer Fechtbuch (MS Chart.A.558)|Gotha Version]] (1443)<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ! <p>[[Talhoffer Fechtbuch (MS Chart.A.558)|Gotha Version]] (1443)<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ||

! <p>[[Codex Danzig (Cod.44.A.8)|Rome Version]] (1452)<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ! <p>[[Codex Danzig (Cod.44.A.8)|Rome Version]] (1452)<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ||

| − | |||

! <p>[[Glasgow Fechtbuch (MS E.1939.65.341)|Glasgow Version]] (1508)<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ! <p>[[Glasgow Fechtbuch (MS E.1939.65.341)|Glasgow Version]] (1508)<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ||

! <p>[[Goliath Fechtbuch (MS Germ.Quart.2020)|Krakow Version]] (1510-20)<br/></p> | ! <p>[[Goliath Fechtbuch (MS Germ.Quart.2020)|Krakow Version]] (1510-20)<br/></p> | ||

| − | |||

! <p>[[Rast Fechtbuch (Reichsstadt "Schätze" Nr. 82)|Augsburg Version II]] (1553)<br/></p> | ! <p>[[Rast Fechtbuch (Reichsstadt "Schätze" Nr. 82)|Augsburg Version II]] (1553)<br/></p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| rowspan="14" | [[File:Cod.44.A.8 7v.jpg|300px|center]] | | rowspan="14" | [[File:Cod.44.A.8 7v.jpg|300px|center]] | ||

| − | | | + | | |

The 1st Figure: | The 1st Figure: | ||

{{red|Charge from the breast to his right hand.}} | {{red|Charge from the breast to his right hand.}} | ||

| − | | | + | | |

'''[22v]''' [1] | '''[22v]''' [1] | ||

Jag võ der prust zu seiner rechtñ hant | Jag võ der prust zu seiner rechtñ hant | ||

| − | | | + | | |

'''[7v]''' Die erst figur | '''[7v]''' Die erst figur | ||

{{red|Jag von der prust zu seiner rechten hand}} | {{red|Jag von der prust zu seiner rechten hand}} | ||

| − | | | + | | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

'''[74r]''' {{red|1}} | '''[74r]''' {{red|1}} | ||

Jag von deiner prust zw seiner rechten handt | Jag von deiner prust zw seiner rechten handt | ||

| − | | '''[165v | + | | |

| − | + | '''[165v]''' | |

| | | | ||

| Line 1,673: | Line 1,663: | ||

| {{red|Die ander figur}} | | {{red|Die ander figur}} | ||

Vmbkere mitt dem Rozz Zewch sein rechte handt mitt deiner lingken | Vmbkere mitt dem Rozz Zewch sein rechte handt mitt deiner lingken | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|2}} | | {{red|2}} | ||

Vmb ker mit dem roß / zeuch sein rechte handt mit deiner lincken | Vmb ker mit dem roß / zeuch sein rechte handt mit deiner lincken | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,688: | Line 1,675: | ||

| Die dritt figur | | Die dritt figur | ||

{{red|Mitt strayffen Satel ryem • oder wer nymbe}} | {{red|Mitt strayffen Satel ryem • oder wer nymbe}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|3}} | | {{red|3}} | ||

Mit Straÿffen satel riem / oder wer nymbt | Mit Straÿffen satel riem / oder wer nymbt | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,703: | Line 1,687: | ||

| {{red|Die vyerdt figur}} | | {{red|Die vyerdt figur}} | ||

Setz an hoch swing durch var • oder Swert prich | Setz an hoch swing durch var • oder Swert prich | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|4}} | | {{red|4}} | ||

Setz an hoch / schwing / durchfar / oder schwert prich | Setz an hoch / schwing / durchfar / oder schwert prich | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,718: | Line 1,699: | ||

| Die funfft figur | | Die funfft figur | ||

{{red|Daz schuten vorgeñgk allen treffenn hawen vnnd stechen}} | {{red|Daz schuten vorgeñgk allen treffenn hawen vnnd stechen}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|5}} | | {{red|5}} | ||

Das schutten / vor geng allen treffen / hawen stechen | Das schutten / vor geng allen treffen / hawen stechen | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,733: | Line 1,711: | ||

| {{red|Die sechst figur}} | | {{red|Die sechst figur}} | ||

Greyff an mitt payden henndten die sterck | Greyff an mitt payden henndten die sterck | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|6}} | | {{red|6}} | ||

Greyff an mit paiden henden die sterck | Greyff an mit paiden henden die sterck | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,748: | Line 1,723: | ||

| Die sybendt figur | | Die sybendt figur | ||

{{red|Hie heb an den mañ taschen haw zu suechen}} | {{red|Hie heb an den mañ taschen haw zu suechen}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|7}} | | {{red|7}} | ||

Hie heb an den man taschen haw zw suechen | Hie heb an den man taschen haw zw suechen | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,763: | Line 1,735: | ||

| {{red|Die Achtt figur}} | | {{red|Die Achtt figur}} | ||

Wenndt Im die recht hanndt • setze den ortt zu den augen sein | Wenndt Im die recht hanndt • setze den ortt zu den augen sein | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|8}} | | {{red|8}} | ||

Went im die recht handt setz dein ortt zw seinem gesicht | Went im die recht handt setz dein ortt zw seinem gesicht | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,778: | Line 1,747: | ||

| Die Newnt figur | | Die Newnt figur | ||

{{red|Wer den stich wertt dem vach sein rechte handt in dein lincken}} | {{red|Wer den stich wertt dem vach sein rechte handt in dein lincken}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|9}} | | {{red|9}} | ||

Wer den stich went dem vach sein rechte handt in dem glincke / | Wer den stich went dem vach sein rechte handt in dem glincke / | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,793: | Line 1,759: | ||

| {{red|Die Zechent figur}} | | {{red|Die Zechent figur}} | ||

Suechee die ploss arm leder hanndtschuech vndtir den augen | Suechee die ploss arm leder hanndtschuech vndtir den augen | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|11}} | | {{red|11}} | ||

Suech die plos arm~ leder handt schuech vndter den augen | Suech die plos arm~ leder handt schuech vndter den augen | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,808: | Line 1,771: | ||

| Die ayndlifft figur | | Die ayndlifft figur | ||

{{red|Druck vast stoss von tzawm • sueche sein Messer}} | {{red|Druck vast stoss von tzawm • sueche sein Messer}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|10}} | | {{red|10}} | ||

Drück vast stoß vom zaüm vnd suech sein messer | Drück vast stoß vom zaüm vnd suech sein messer | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,823: | Line 1,783: | ||

| {{red|Die Zwolfft figur}} | | {{red|Die Zwolfft figur}} | ||

Mitt lerer hanndt lere zwen strich gegen aller were | Mitt lerer hanndt lere zwen strich gegen aller were | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|12}} | | {{red|12}} | ||

Mit lerer handt lern straich gegen aller were / | Mit lerer handt lern straich gegen aller were / | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,838: | Line 1,795: | ||

| Die dreitzechent figur | | Die dreitzechent figur | ||

{{red|Der schaf grif wertt • alle griff Ringens vndter augenn}} | {{red|Der schaf grif wertt • alle griff Ringens vndter augenn}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| '''[74v]''' {{red|13}} | | '''[74v]''' {{red|13}} | ||

Der Schaffgriff werdt alle griff ringes vndter auge~ | Der Schaffgriff werdt alle griff ringes vndter auge~ | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,852: | Line 1,806: | ||

| {{red|Dein Sper bericht etc Ob es emphal etc Haw dreyn nichtt Zuckch etcettera}} | | {{red|Dein Sper bericht etc Ob es emphal etc Haw dreyn nichtt Zuckch etcettera}} | ||

Glosa lingck zu Im ruck • Greyff in sein rechten • so vechst du In ane vechttenn | Glosa lingck zu Im ruck • Greyff in sein rechten • so vechst du In ane vechttenn | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,866: | Line 1,818: | ||

| '''[8r]''' {{red|Die viertzendt figur}} | | '''[8r]''' {{red|Die viertzendt figur}} | ||

Anderwayd kere vmb • so die Rozz hynn hurtten | Anderwayd kere vmb • so die Rozz hynn hurtten | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|14}} | | {{red|14}} | ||

| − | An der weidt ker vmb / so die roß hyn hurttñ / | + | An der weidt ker vmb / so die roß hyn hurttñ / |

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,881: | Line 1,830: | ||

| Die funfftzend figur | | Die funfftzend figur | ||

{{red|In der nech vach die hanndt • verkere sein anttlitz da der nack ist}} | {{red|In der nech vach die hanndt • verkere sein anttlitz da der nack ist}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|15}} | | {{red|15}} | ||

In der nech fach die handt verker sein antlutz do der nacke ist | In der nech fach die handt verker sein antlutz do der nacke ist | ||

| '''[166r]''' | | '''[166r]''' | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,896: | Line 1,842: | ||

| {{red|Die sechtzechend figur}} | | {{red|Die sechtzechend figur}} | ||

Die were vach in der weytt • In dem wider Reytten | Die were vach in der weytt • In dem wider Reytten | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|16}} | | {{red|16}} | ||

Die weer fach in der weitt in dem wider reÿttñ | Die weer fach in der weitt in dem wider reÿttñ | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,911: | Line 1,854: | ||

| Daz sybentzechend figur | | Daz sybentzechend figur | ||

{{red|Jagst du lingk so vall auf Swertes Kloss • stoss vndter augenn}} | {{red|Jagst du lingk so vall auf Swertes Kloss • stoss vndter augenn}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|18}} | | {{red|18}} | ||

Jagstu linck fall aüfs schwertz knopf stos vndter augen | Jagstu linck fall aüfs schwertz knopf stos vndter augen | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,926: | Line 1,866: | ||

| {{red|Die achttzechendt figur}} | | {{red|Die achttzechendt figur}} | ||

Jage Zu der rechtten hanndt mitt Iren Kunsten | Jage Zu der rechtten hanndt mitt Iren Kunsten | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|17}} | | {{red|17}} | ||

Jag zw der rechtñ handt / mit irñ kunstñ | Jag zw der rechtñ handt / mit irñ kunstñ | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,941: | Line 1,878: | ||

| Die Nëwntzechent figur | | Die Nëwntzechent figur | ||

{{red|Setz an den ortt gegen dem gesichtte}} | {{red|Setz an den ortt gegen dem gesichtte}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|19}} | | {{red|19}} | ||

| − | Setz an den ortt gegen dem gesicht | + | Setz an den ortt gegen dem gesicht |

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,956: | Line 1,890: | ||

| {{red|Die tzwaintzigist figur}} | | {{red|Die tzwaintzigist figur}} | ||

Schutt gegen allen treffen • Diee ymmer werdenn | Schutt gegen allen treffen • Diee ymmer werdenn | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|20}} | | {{red|20}} | ||

Schutt gegen allen treffen die ym~er werdñ | Schutt gegen allen treffen die ym~er werdñ | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,971: | Line 1,902: | ||

| Die ain vnd tzwayntzigist figur | | Die ain vnd tzwayntzigist figur | ||

{{red|Die sterck in dem anheben • Dar Inn dich rechtt schicke}} | {{red|Die sterck in dem anheben • Dar Inn dich rechtt schicke}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|21}} | | {{red|21}} | ||

Die stercke in dem an hebñ daryn dich recht schick / | Die stercke in dem an hebñ daryn dich recht schick / | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,986: | Line 1,914: | ||

| {{red|Die tzwo vnd tzwaintzigst figur}} | | {{red|Die tzwo vnd tzwaintzigst figur}} | ||

Das ist nun der sper lawff • der dem andern begegendt vndter augen | Das ist nun der sper lawff • der dem andern begegendt vndter augen | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|22}} | | {{red|22}} | ||

Das ist nun der sper lauff der dem anderñ begegnet vndter augen / | Das ist nun der sper lauff der dem anderñ begegnet vndter augen / | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 2,005: | Line 1,926: | ||

| Die drey vnd tzwaintzigist figur | | Die drey vnd tzwaintzigist figur | ||

{{red|Der vngenant griff • wer nymbtt oder velt In}} | {{red|Der vngenant griff • wer nymbtt oder velt In}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|23}} | | {{red|23}} | ||

Der vngenant griff weer ny~t oder felt in | Der vngenant griff weer ny~t oder felt in | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 2,020: | Line 1,938: | ||

| {{red|Die vier vnd tzwaintzigist figur}} | | {{red|Die vier vnd tzwaintzigist figur}} | ||

ob man dich Jagt zu° bayden seytten kere vmb lingk so er rechtte kumbt | ob man dich Jagt zu° bayden seytten kere vmb lingk so er rechtte kumbt | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|24}} | | {{red|24}} | ||

Ob man dich jagt von paidñ seÿttñ ker vmb linck so er recht kumbt | Ob man dich jagt von paidñ seÿttñ ker vmb linck so er recht kumbt | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 2,035: | Line 1,950: | ||

| Die funff vnd tzwaintzigist figur | | Die funff vnd tzwaintzigist figur | ||

{{red|Der Mezzer nemenn • vnd behalden gedenck}} | {{red|Der Mezzer nemenn • vnd behalden gedenck}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| '''[75r]''' {{red|25}} | | '''[75r]''' {{red|25}} | ||

Der messer nemen vnd behalden gedenck | Der messer nemen vnd behalden gedenck | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 2,050: | Line 1,962: | ||

| {{red|Die sechßvndtzwaintzigist figur}} | | {{red|Die sechßvndtzwaintzigist figur}} | ||

vbergreif wer dich anvelet • oder thue Im wider Reyttens | vbergreif wer dich anvelet • oder thue Im wider Reyttens | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| {{red|26}} | | {{red|26}} | ||

Vber greÿff wer dich an felt oder thue im wider reÿttens / | Vber greÿff wer dich an felt oder thue im wider reÿttens / | ||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 2,064: | Line 1,973: | ||

| {{red|Wild du anfazzen neben reittens nit solt du lasen daz sunnen tzaigen lingk ermel treib wildu naygen}} | | {{red|Wild du anfazzen neben reittens nit solt du lasen daz sunnen tzaigen lingk ermel treib wildu naygen}} | ||

Wer dir daz rembt vbergreifft den der wierd beschämbt druck arm zu haubt der griff offt sattel berawbett | Wer dir daz rembt vbergreifft den der wierd beschämbt druck arm zu haubt der griff offt sattel berawbett | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

Revision as of 22:04, 3 July 2017

|

Caution: Scribes at Work This article is in the process of updates, expansion, or major restructuring. Please forgive any broken features or formatting errors while these changes are underway. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. Stay tuned for the announcement of the revised content! This article was last edited by Michael Chidester (talk| contribs) at 22:04, 3 July 2017 (UTC). (Update) |

| Die Zettel | |

|---|---|

| The Recital | |

| |

| Full Title | A Recital on the Chivalric Art of Fencing |

| Ascribed to | Johannes Liechtenauer |

| Illustrated by | Unknown |

| Date | Fourteenth century (?) |

| Genre | |

| Language | Middle High German |

| Archetype(s) | Hypothetical |

| Manuscript(s) |

Cod.44.A.8 (1452)

|

| First Printed English Edition |

Tobler, 2010 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

Johannes Liechtenauer (Hans Lichtenauer, Lichtnawer) was a German fencing master in the 14th or 15th century. No direct record of his life or teachings currently exists, and all that we know of both comes from the writings of other masters and scholars. The only account of his life was written by the anonymous author of the Nuremberg Hausbuch, one of the oldest texts in the tradition, who stated that "Master Liechtenauer learnt and mastered the Art in a thorough and rightful way, but he did not invent and put together this Art (as was just stated). Instead, he traveled and searched many countries with the will of learning and mastering this rightful and true Art." He may have been alive at the time of the creation of the fencing treatise contained in the Nuremberg Hausbuch, as that source is the only one to fail to accompany his name with a blessing for the dead.

Liechtenauer was described by many later masters as the "high master" or "grand master" of the art, and a long poem called the Zettel ("Recital") is generally attributed to him by these masters. Later masters in the tradition often wrote extensive glosses (commentaries) on this poem, using it to structure their own martial teachings. Liechtenauer's influence on the German fencing tradition as we currently understand it is almost impossible to overstate. The masters on Paulus Kal's roll of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer were responsible for most of the most significant fencing manuals of the 15th century, and Liechtenauer and his teachings were also the focus of the German fencing guilds that arose in the 15th and 16th centuries, including the Marxbrüder and the Veiterfechter.

Additional facts have sometimes been presumed about Liechtenauer based on often-problematic premises. The Nuremberg Hausbuch, often erroneously dated to 1389 and presumed to be written by a direct student of Liechtenauer's, has been treated as evidence placing Liechtenauer's career in the mid-1300s.[1] However, given that the Nuremberg Hausbuch may date as late as 1494 and the earliest records of the identifiable members of his tradition appear in the early 1400s, it seems more probable that Liechtenauer's career occurred toward the beginning of the 15th century. Ignoring the Nuremberg Hausbuch as being of indeterminate date, the oldest version of the Recital appears in the MS G.B.f.18.a, dating to ca. 1418-28 and attributed to an H. Beringer, which both conforms to this timeline and suggests the possibility that Liechtenauer was himself an inheritor of the teaching rather than its original composer (presentations of the Recital that are entirely unattributed exist in other 15th and 16th century manuscripts).

Contents

Treatise

Liechtenauer's teachings are preserved in a brief poem of rhyming couplets called the Zettel ("Recital"). These "secret and hidden words" were intentionally cryptic, probably to prevent the uninitiated from learning the techniques they represented; they also seem to have offered a system of mnemonic devices to those who understood their significance. The Recital was treated as the core of the Art by his students, and masters such as Sigmund ain Ringeck, Peter von Danzig zum Ingolstadt, and Jud Lew wrote extensive glosses that sought to clarify and expand upon these teachings.

Seventenn manuscripts contain a presentation of at least one section of the Recital as a distinct (unglossed) section; there are dozens more presentations of the verse as part of one of the several glosses. The longest version of the Recital by far is found in the gloss from the Nuremberg Hausbuch, which contains almost twice as many verses as any other. However, given that the additional verses tend to either consist of repetitions from elsewhere in the Recital or use a very different style from Liechtenauer's work, they are generally treated as additions by the anonymous author or his instructor rather than being part of the standard Recital. The other surviving versions of the Recital from all periods show a high degree of consistency in both content and organization, excepting only the version attributed to Beringer (which is also included in the writings of Hans Folz).

The following concordance tables include only those texts that quote Liechtenauer's Recital in an unglossed form.[2] Most manuscripts present the Recital as prose, and those have had the text separated out into the original verses to offer a consistent view. For ease of use, this page breaks the general Wiktenauer rule that column format remain consistent across all tables on a page; the sheer number of Liechtenauer sources made this convention entirely unworkable, so instead the long sword table uses one layout, the mounted and short sword tables use another, and the figures use a third.

Featured Translation (from the Rome) |

Gotha Transcription (1443) |

Rome Transcription (1452) |

Copenhagen Transcription (1459) |

Wolfenbüttel I Transcription (ca. 1465-80) |

Munich I Transcription (ca. 1470) |

Vienna Transcription (1480s) |

Dresden Transcription (ca. 1504-19) |

Krakow Transcription (1510-20) |

Munich II Transcription (1523) |

Augsburg I Transcription (1523) |

Glasgow Transcription (1533) |

Augsburg II Transcription (1553) |

Munich III Transcription (1556) |

Wolfenbüttel II Transcription (ca. 1588) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Here begins the epitome on the knightly art of combat that was composed and created by Johannes Liechtenauer, who was a great master in the art, God have mercy on him; first with the long sword, then with the lance and sword on horseback, and then with the short sword in armoured combat. Because the art belongs to princes and lords, knights and squires, and they should know and learn this art, he has written of this art in hidden and secret words, so that not everyone will grasp and understand it, as you will find described below. And he has done this on account of frivolous fight masters who mistake the art as trivial, so that such masters will not make his art common or open with people who do not hold the art in respect as is its due. |

[18r] Hye hebt sich an meister liechtenawers chunst Deß lengen swerts Anno domini xlviij Jar etc |

[3r] Alhÿe hebt sich an dye zedel der Ritterlichen kunst des fechtens dye do geticht vnd gemacht hat Johans Liechtenawer der ain hocher maister In den künsten gewesen ist dem got genadig seÿ |

[104v] [A]lhie hebt sich an die zetl der ritterlichen chunst des fechtens die geticht vnd gemacht hat hanns liechtenauer der ein hocher maister in den künsten gewessenn ist dem got genadig sey des ersten mit dem lanngen swert darnach mit dem spies vnd darnach mit dem swert zw ross vnd darnach mit dem kurczen swert zw ross kampf vnd dar vmb das die kunnst fürsten vnd herrenn rittern vnd chnechten zw gehort das sy wissenn vnd lernen sullenn so hat er die ritterlichen chunst yedleich pesunder lassen schreibenn mit verporgen vnd verdackten worten dar vmb das Sy yeder man nit versten müg vnd hat das getan durch der schirmmaister willen die ir chunst ring wegen das von den selbm sein chunst nit geoffenwart werd lewtten die die chunst nicht in wierden chünen haldenn als den chunnsten zue gehört |

[03r] JN sant Jörgen namen höbt an die kunst deß fechtens die gedicht vnd gemacht hat Johanns liechtnawer der ain hocher maister In den kunste~ gewesen ist dem gott genädig sÿ Deß ersten mitt dem langen schwert Dar nach mitt dem spieß Vnnd dem schwert zu° roß Vnnd och mitt dem kurczen schwert zu° dem kampf als her nach geschriben stat ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This is the Prologue

|

Junck ritter lere |

Das ist dy vor red Junck ritter lere |

[IIIr] Junck ritt° leren |

[45r] Junger Ritter lern |

Jüngk ritte~ lere / |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This is a general teaching of the long sword

|

Das ist eyn gemeine ler des swertz etc wiltu kunst schawen |

Das Ist ein gemaine ler des langen Swerttes ·:~Wildu kunst schauen |

¶ Wiltu kunst schawe~ |

Ain gemaine lere Wildw kunst schawn |

Das ist ein gemaine ler des langenn Swercz vnnd ist das die vor redt [W]Ild dw chunnst schauen |

Das ist ain gemain lere des langen schwerts Wilt du kunst schawen |

[43r] Ein gutt gemain for des langen schwerts Wilstu kunst schawen |

[42br] Ein gutt gemain ler des langen schwertz Wilttu kunst schawen |

[48r] Ein gutte gemaine lesr des langen schwerts Wiltu kunst schauwen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This is the text:

|

funf hew leren |

ffünff häw lere |

¶ ffunff haw dei leren |

funff hew lern |

Fünff hew lere |

Funff hewe lere |

funnf haw lernen |

funnff hew lernen |

und 5 hauw lehrnen, | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Wrath Stroke

|

Das ist der text an dy außlegu~g Zoren hawe kru~p twirg |

Der zoren haw ·W·er dir öberhäwtzorenhaw ort dem drawt wirt er es gewar Nÿm oben ab öne far Piß starck her wider wind stich sicht leger waich oder hers nÿm es nyder Das eben merck haw stich leger waich oder hert Inndes vnd var nach an hürt Dein krieg sey nicht gach oben nÿden wirt er beschempt In allen winden Haw stich schnÿdt lere vinden Auch soltu mit prufen Haw stich oder schnÿd In allen treffen den maisteren wiltu sy effen ~ |

Tarnhaw kru~phaw thwere |

|

[Z]orn haw twer |

Das ist der texte Zorn hawe krumpt were [05r] Nÿm oben ab an far / biß störcks storckñ wider wennde sthich / sicht er es nÿm es nider Daß eben mörcke Haw° sthich leger waich ode~ hörte In des Vnnd far nach an herte dein krieg sÿ mnitt gach oben In den wirt er beschemet In allen treffen den maister wilt du sÿ effenn In allen winden Hew° st stich schnitt lern finden Auch solt du mitt briefn brieffe hew stich oder schnitt ~ ·:· ~ |

Text von denn Stucken der Zetl Zornnhaw, Krump, Twir,

[02r] Wer dir oberhaut

Zonhau[!] ort dem drawt, Wirt er es gewar Nim oben ab öne far Piß starck herwider Wind stich sicht ers nim es wider Das ebenn merck Hau stich leger waich oder hert Inndes und var nach an hurt dein krig sei nich gach oben niden wirt er beschempt In alln winden. Haw stich schnidt lerre finden, auch soltu mit prüsen[!] hau stich oder schnÿd in alln treffen den maistern wiltu sie effen |

Das ist der text und die auslagung der schaittler Zornhaw krumphaw zwerch |

+ Das ist der text vnd die auslegung der schaitler Zornhaw krumphaw zwerch |

[15r] Der zornhaw Wer dir vberhaut,zornhaw, ort dem traw, wirt er es gewar nym oben ab ane vor, bis sterckher wieder wind stich sicht er es, nym es nyder, das oben merckh, haw stich beger weich oder hert jm des, vnnd vor nach an hurt dem krieg sey nit gach, oben Nider wirt er beschemet, jn allen winden, haw stich schnite leere winden, auch soltu Brrueffen, mit hawe stich oder schnite, jm allem treffen, den maistern wilt du si treff Effen, |

Das ist der tex und die aus richtung der schaitter Zornhauw, krumhauw, Zwerch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The War

|

Das ist võ czorn hawe dÿ außrichtu~g Wer dir obñ hawtczorn haw ort Im drvet Wirt er eß gewar ny~ obñ ab anefar biß starck hin wider wint stich sicht erß ny~ eß nÿder das ebñ merck haw stich leger weich oder hert In deß vnd var vnd nach an hurt den krieck sey nicht czu gahe etc Das ist der krieck Was der krieck remetobñ nyder wird beschemet In allñ winte~ hawe stich snytt ler winde~ auch soltu mit prufe~ haw stuch oder snyt In allm~ treffen dÿe meister wiltu sye effñ |

Dÿe vier plossen Vier plössen wisse |

wen dir oben hauwz

Tzoharnort em drowz wert er es gewar Nym es oben ane var wys starck wid° en wir° stich schicher ny~ es nyden Das eben merke vñ warte haw stich s leg° weich od° harte — Indes far nach An hurt dein krig sey nich gach Obin nider wirt veschempt ¶ In allen winden hau stich ler en vinde~ In allen zu dreffen Dey meisters wiltu sey effen |

Zorn haw Wer dier oberhautzorn ort dem trät wirt er es gewar nym oben ab ame [!] far pis stercker wider windt stich sicht ers nym es nyder das eben merck haw stich leger waich oder hert Inndes vnd far nach an hurt dein krieg sey nit gach oben nyden wirt es verschemet in allen winden Haw stich schnit lere finden auch sold dw nit [!] prüffen hew stich schnit in allenn treffen den maistern wildw sy affenn |

Die vier blossen zu° breche~ Vier blossen wisse |

Die vir Ples Vier Plössen wisse |

Das ist die ausrichtung vom Zornhaw Wilstu merckhen wer dir oberhawttZornortt ein darott Ser wider wind stich sichters so nim es nider das eben merckh haw stich legr waich oder hörtt Indes vor und nach dem krieg seÿ dir nit gach der wirtt oben ösche[ ]tt In allen winden haw und f[ ] stich [43v] Schneide finden auch so soltt du nit nieden hau stich schneide zuckg in alem treffen wiltu den maister Effen |

+ Das ist die ausrichtung vom zornhaw Wilttu merckhen wer dir oberhawttzornortt ein dratt herwider wind stich sicht ers so nim es wider das eben merckh haw stich legr~ waich oder hörtt Indes vor vnd nach dein krieg seÿ dir nit gach der wirtt oben bschemett In allen winden haw vnd stich schneide finden auch so soltt du nit meiden haw stich schneide zuckh in allem treffen wilttu den maistr~ Effen |

Die vier plössen, Vier plösse,,,,wisse |

Das ist die ausrichtung vom Zornhauw Wiltu merckhen wan dir oben hautzornortt, im tritt herwider windt sticht sicht was so nim es wider dz eben merkh hauw. stich leger waich oder hart in dz vor und nach dem krieg sei dir nit gach der wirt oben beschemet in allem windt hauwe und stich schneidt finden auch so soltu nit meiden, hauw stich schneiden zuckh in allen trefen wiltu dem maister essen. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Four Openings

|

[19r] Das ist võ den vier ploßenn Vier ploß wiß |

Dye vier plossen zw prechen Wildu dich rechen |

¶ Veyr blos dey wisse |

[62r] Vier blosse wisze |

die vier plossenn [V]Ier plosse wisse |

|

[02v] wisse |

Das ist von den vier blössen Die einer blöss wis |

[42vb] Das ist von den 4 blösen + Die vier blöss wisse |

Die vier plössen zubrechen Wiltdu dich rechen |

Das ist von den 4 blossen Die 4 blos wiss | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

To Counter the Four Openings

|

Das ist wie mã dÿ vier ploßenn sol prechñ Wiltu dich rechenn |

Der krump haw Krump auff behende |

wiltu dich rechen |

wild dich rechen |

Die vier blossen zu° brechen Wilt du dich rechen |

Die vir Plössen zu prechen Wildu dich rechen |

Das ist wie man die vier blöss brechne sol Wilstu dich Rechen |

+ Das ist wie man die 4 blöss brechen sol Wilttu dich Rechen |

Der krumbhaw Krumb auff behende |

Das ist wie man die 4 blos brechen soll. Wiltu dich rechen, | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Crooked Stroke

|

Das ist vom chrump haw dÿ außrichtu~g chru~p auff behendt |

|

¶ krum uff bohe~de |

[66v] krumpf auf Behende |

[K]rump auf Behende |

Der Km Krumphaw° Krump vff behende |

Krumphau Krump auff behende |

Das ist die ausrichtung vom krumphaw Krumphaw auff behend |

+ Das ist die ausrichtung vom krumphaw Krumphaw auff behend |

|

Das ist die ausrichtung vom krummhauw[13] Krum hauw auf behend, | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Thwart Stroke

|

Das ist võ twi°g haw dye außrichtu~g Twirg benymet |

Der twer haw Twer benympt |

Twirch bonimpt |

Der twer haw [T]wer[14] benimpt |

Der zwerchhaw° Zwerch benimpt |

Twerhaw Twer benimpt |

Die ausrichtung vom Zwerchhaw Die Zwerchhaw benimptt |

+ Die ausrichtung vom zwerchhaw Die zwerchhaw benimpt |

Der Twer haw Twer benymbt, |

Die ausrichtung vom zwerchauw Die zwerchauw nimpt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Der schilhaw Schiler ain pricht |

Scheller ein bricht |

|

|

|

|

|

+ Die ausrichtung vom schilthaw Schilcher enibricht |

Der von schilhaw Schiller einpricht, |

Die ausrichtung vom schilthauw Scheleher einbricht | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Squinting Stroke

|

[19v] Das ist võ schilhaw dy außrichtu~g Schiler enpricht |

Der schaittelhaw Der scheitlar |

Der scheitler |

der schilhaw [Sch]ilcher ein pricht |

Der schilhaw° Schiller In bricht |

Schilhaw Schiler am[!] pricht |

Die ausrichtung vom schilthaw Schilchr ein bricht |

Der scheitler Der sheitler |

Die ausrichtung vom schaitelhauw. Der schaitler | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Scalp Cut

|

Das ist võ dem schilthaw dy außrichtu~g Der scheÿtler |

|

¶ veir leger alleyn |

[D]er schaitler |

Der schaittelhaw° Der schille~ |

Schaittelhau [04r] Der scheitler |

Die ausrichtung von dem schaitelhaw Der schaitler |

[43r] + Die ausrichtung von dem schaitelhaw Der schaitler |

|

Die ausrichtung von den 4 legern Die 4 leger allain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Four Guards

|

Das ist von den vier leger dÿ außrichtung Vier leger alben |

Dÿe vier leger Vier leger allain |

¶ veir sint vorsetzen |

[58r] Die erste hute haist der ochse |

Die vier leger [V]ier leger allain |

Die vier leger Vier leger allain |

Vir leger Vir leger allain |

Die ausrichtung von den vier legern Die vier leger allain |

+ Die ausrichtung von den vier legern Die vier leger allain |

Die vier leger Vier Leger allein, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Four Oppositions

|

Das ist võ den vier versetze~ dy außrichtung Vier sint der vor seczen |

Dye vier vor Setzen Vier sind vor setzen |

nachreisen lere |

Die vier verseczenn [V]Ier seind der verseczen |

Die vier verseczen Vier sind verseczten |

Vier vörsetzen [04v] Vir seind vörsetzen |

Die ausrichtung von den vier versetsen Vier sind der versetsen |

+ Die ausrichtung von den vier versetzenn Vier sind der versetzen |

Die vier versecz[en] Vier sind verseczen, |

[49r] Die ausrichtung von den 4 versetzen Vier seind der versetzen, | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chasing

|

Das ist võ dem nach reÿse~ dÿ außrichtu~g Nach reyßenn lere |

Von Nach Reÿsen N·ach raisen lere |

wer vnde~ ramz // |

[65v] Nachreýsen zwýfacht |

von nachraisen nach raissenn lern |

Von Nachraÿsen Nachraÿsen lere / |

Nachraisen Nachraisen lere |

Die ausrichtung vom schilthaw Schilchr ein bricht |

+ Von dem nachRaisen Nachraisen lere |

Von Nachraisen, Nachraisen Leere, |

Von dem nachraisen Nachraisen lehren | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Overrunning

|

[20r] Von vber lauff dy außrichtu~g ~Wer vndenn remet |

von überlauffen ·W·er vnnden rempt |

ler aff setze~ // |

Von vberlauffenn er vnden rempt |

Von v°berlauffen ~ [08r] Wer vnden rempt / |

Uberlauffen Wer unden rempt |

[44v] Das die ausrichtung von dem uberlauffen Der unden Remet |

Die ausrichtung von dem l vberlauffen Der vnden Römett |

Von vberlauffen, Wer vnnden remet |

Die ausrichtung von dem uberlauffen Der unden renet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Setting Aside

|

leren abseczenn |

Von absetzen Lere absetzen |

Dorch wessel lere |

von abseczenn Lern ab seczenn |

Von abseczen Lere abseczen |

Absetzen Lere absetzen |

Die ausrichtung von dem absetsen Lere absetsen |

+ Die ausrichtung von dem absetzen Lere absetzen |

[16v] Von abseczen, Leere abseczen, |

Die ausrichtung von dem absetzen Lehren absetzen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Changing Through

|

Das ist võ durch wechsel dy außrichtu~g Durch wechsel lere |

Von durchwechselen Durchwechsel lere |

Drit nachet i~ binden |

[66r] Dúrchwechsel lere |

Vom durchwechsl Durch wechsel lere |

Von durchwechslen Durchwechslen lere / |

[05v] Durchwechseln Durchwechsell lerre |

Von dem durchwechsell Der durchwechsel lere |

[43v] + Von dem durchwechsel Der durchwechsel lere |

Von Durchwechsel, Durchwechsel Leere, |

Von dem durchwechsel Der durchwechsel lehren | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pulling

|

Das ist võ zuckenn dy außrichtu~g Trit nahent In bunde |

von zucken Trit nahent Inn pinden |

Page:Ms.Thott.290.2º 004v.jpg |

Dorloff das hange~ |

Von zuckenn drit nachet in punndenn |

[08v] von Zucken Tritt nahent Inbinden / |

Zucken Trit nahent in pinden |

Die ausrichtung von dem Treffn und Zuckn Dritt mein die binden |

Die ausrichtung von dem treffen vnd zuckhe[n] Dritt nein die binden |

Von zucken, Trit nahendt in pinde, |

Die ausrichtung von treffen, treffe und zukhen Tritt man die binden | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Running Through

|

Das ist võ Durch lauffung dy außrichtu~g Truckdurch//lauffñ |

von Durchlauffen Durchlauff las hangen |

Snid aff dei hertzen |

von zwain hengen von durchlauffen

|

von durchlau°ffen Durchlauff laß hangen |

Durchlauffen [06r] Durchlauffen las hangen |

Die ausrichtung von dem durchlauffen Durchlauff las hengen |

+ Die ausrichtung von dem durchlauffen Durchlaüff lass hengen |

Von Durchlauffen, Durchlauff laß hangen, |

Die ausrichtung von dem durchlauffen [49v] Durchlauffen las langen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Slicing Off

|

Das ist võ ab sneydenn dÿe außrichtu~g Sneyd ab dy hertt |

von abschneiden Schneid ab dÿ herten |

|

von durchlauffenn durchlauf laß hangen |

von abschnÿden Schnid ab die hertt~ / |

Abschneiden Schneit ab die Hertten, |

Die ausrichtung von dem abschneiden Sschneidt ab die hertte |

Die ausrichtung von dem abschneiden Schneid ab die hörtte |

Von abschneiden Schneid ab die hannd, |

Die ausrichtung von dem abschneiden Schneid die hänte | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pressing Hands

|

Das ist võ hent truckñ dy außrichtu~g

|

von hend drucken [6r] |

|

sneid ab die herten |

[09r] von hende trucken

|

Hend druckhen.

|

Von dem hend truckhen Das schwertt bind |

+ Von dem hendt truckhen Das schwertt bind |

Von hennd truckhen,

|

Von den hend trucken Das schwert binden | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Two Hangings

|

Das ist võ czweÿen henge~ dy außrichtu~g

|

von tzwaien hengen

|

¶ Spreck vinster mache |

|

von zwaÿen hengen

|

[06v] Zwei henngen

|

Von den Zwaien hengen die ausrichtung

|

Von den zwaien hengen die ausrichtung

|

[17r] Von zwayen hengen

|

Von den 2 hengen die ausrichtung

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Speaking Window

|

[20v] Das ist võ sprech fenster dy außrichtu~g Sprech venster mach |

von sprechfenster Sprechfenster mach |

Page:Ms.Thott.290.2º 005r.jpg |

wer wol bricht // |

[70v] Sprechfinster[!] mach |

sprechfenster mache |

von sprechfenster Sprechfenste~ mach |

Sprechfennster Sprechfennster mach. |

[45r] Von dem sprechfenstr die ausrichtung Das sprechfenster machen |

Von dem sprechfenstr~ die ausrichtgung Das sprechfenster machen |

Von Sprechvenster Sprechvenster machen, |

Von den sprechfenster die ausrichtung Das sprechfenster mach | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This is the Conclusion of the Epitome

|

Das ist dy beslißu~g der gancze~ kunst Wer wol pricht |

Das ist die beschliessung der zedel Wer wol fürt vnd recht pricht |

Et[c] & finis |

besliessúnge der gantzen zettel |

der zetl pesliessung [W]er wol fueret vnd recht pricht |

[09v] Die beschliessung der zedel Wer wol füret Vñ recht bricht |

.Bßießung[!] der Zetl. Wer woll furt, unnd recht bricht |

Das ist die ausrichtung und die beschliesung der grunsn kunst wer vol sicht |

Das ist die ausrichtung vnd bschliesung der gantzen kunst wer wol sicht |

Das ist die beschliessung der zetl Wer wol furet vnd recht bricht, |

Das ist die ausrustung und die beschliessung de gantzen kunst, wer wol ficht | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thus ends Master Liechtenauer's Art of the Long Sword | ennd des text der Fechtzetl. |

also endett sich maister Liechtnauers kunst des langen schwertts |

also endett sich maistr~ liechtnauers kunst des langen Schwertz |

also ender sich Maister Liechtenauers kunst des langen schwerts. |

Featured Translation |

Nuremberg Transcription (1400s) |

Gotha Transcription (1443) |

Rome Transcription (1452) |

Vienna Transcription I (1480s) |

Salzburg Transcription (1491) |

Krakow Transcription (1510-20) |

Vienna Transcription II (1512) |

Augsburg Transcription II (1553) |

Rostock Transcription (1570-71) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This is Master Johannes Liechtenauer’s Fighting on Horseback | [53r] Hie hebt sich nu an das fechten zu Rosse in harnüsche / mit sper vnd swerte etc~

JVng / Ritter lere · |

[21Av] Alhye hebt sich an dy chunst deß langñ swerts deß Roß vechtenn |

[06r] Das Ist Maister Johansen liechtenäwer ross vechten |

[105r] Maister hannsen liechtenauers ross fechtenn |

[017r] Das ist das Ross fechten das junger Ritter leern |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

~:DEyn sper berichte · das swert keyn swerte wit wirt gehandelt / Recht fasse dy sterke · taschenhawe du in süchen merke / lere wol stark schoten · alle treffen ane var / mit nöten / An setze ane vare · wer stroiff heng in zu dem hare / Wiltu geruet · lang iagen sere müet / wer das nü weret · zo wind das selbe awge vorseret / Wert her das vörbas · vach den zawm weze nicht las / Bedenke dy bloßen · suche messer nicht warte klößen / In aller were · deyn ort / keyn der bloßen kere / Zwene striche lere · mit lerer hant keyn der were / Der schofgriff / weret · alle griffe vndern awgen veret / Der schofgriff / weret · alle griffe vndern awgen veret / ¶ Auch merke dy seiten · do du of vorteil gerest reiten / Wer of dich wil hawen · vorsetzen saltu dich frawen / Vnd vinden snete · hinden vnd vorne stich sere mete / Dornoch abehawe · zawm hant / recht beyn zonder drawe / Wen du erst windest · ruche ansetzen / etwas du vindest ¶ wer of dich synnet · vnd synt swert zu durchrynnen gewynnet / An zweiuel wint an · wiltu keynen schaden von im han / Dy link seite merke · deyn erbeit auch mete sterke / winden vorsetzt · swert lang / los hangen zo ist her geletzt / Dornoch in blende · der dich mit vorsetzen wil schenden / Ane sorge nym war · var im balde vnder arm dar / Recht lang los hangen · das lobe ich ganz wiltu rangen / Drük vast mit stössen · vom zawm / süche messer reme der blossen / ¶ Übe dy kunst zu vorne · in schimpf · zo gedenkstu ir in zorne / [57v] DEr schofgrif weret · wer ringens sich zu dir keret / Als vndern awgen · ane greife lere mete flawgen / Wer dich an fellet / weder reitens der wirt gefellet / Hangens zur erden · öbergreif in recht mit geberden / Zu beiden seiten · du in an ler dich al weder reiten / Der schofgrif mit lobe · wert alle griffe vndern ogen / Der schofgrif mit lobe · wert alle griffe vndern ogen /</noinclude> [58r] Ab du wilt reiten · roslawfens zur andern seiten / der sterke schote · ane setze do mete nöte / wer weret dir das · weite swert vach natrag der handlas / Ader vmbe kere · ruet zu iagen der were / Mit allen künsten · der iagt den schicke noch günsten / Ab du voriagest · vnd ane danke linke iagst / Seyn swert auf taste / vnd rangen stoz sere mete vaste / [58v] Iagt man rechtens · halb kere link / warte vechtens / Mit armen vahen · zo mag dir· keyn schade nahen / kere anderweit vmbe / ab dy roz nü hin sprüngen /

behalden ler ane schemen / den vngenanten · dy starken in io vorwanten / Irslaen irstechin / vorterbet an alle fechten / [59r] UIltu[23] an fassen · neben reitens nicht saltu lassen / Das zunne zeigen · linke ermel treib wiltu neigen / Das vorhawp taste · kegen nacken drük zere vaste / das her sich swenket · selten weder auf/sich gelenket / wer dir do remet · öbirgreif den der X[24] wirt beschemet / Druk arm an hawpt · der grif ofte zatel rawbet / Wilt aber dy masen · des vahens leicht von dir lasen / Ringens den fure · gevangen hin ane snüre / Den vorgrif merke · der bricht vörbas syne sterke / |

Dein sper bericht behalten lere an schame dem vngnnten dem starckenn in jo ver wante Ir slagñ Ir stechenn verderbt in alles vechtñ wiltu a neben reÿtens nicht soltu loßen das sonne~ czeigñ linck ermel I treibt wiltu neig das võ hewbt dast gege~ nack truck ser vast das er sich swencket vnd selten wider auff lencket wer dir das remet vber greiff den der wirt beschemet truck an czu heubt der greifft offt satell raw~pt wiltu aber dich maßenn deß vahens leich von dir laßenn lãgens den fur gefangenn hin ane var den vor griff merck der pricht fur pas sein sterck |

[006v] Dein sper berichtGegen reiten mach zu nicht Ob es empfalle Dein end ÿm ab schnalle Haw drein nicht zucke Von schaiden link zw ÿm rucke Greiff in sein rechten So fechstu in ane fechten Das gleffen stechen fechten Sittigklich an hurt lere prechen Ob es es sich vor wandelt Das swert gegen swert wirt gehandelt Recht vaß dÿ sterck taschen haw tü süch vnd merck ler wol starck schütten Allen treffen an far do mit nött in An setz an far wer straifft heng im zu dem har wiltu gerüt lanck jagen das sere müt wer das nu wert So wind das aug vorsert wert ers fürpas Vach zawm vnd wes nicht las Bedenck die plöß Suech plöss messer nicht wartt klöss Zwen strich ler Mit lärer hant gegen di der wer Der schaff grif weret wer sich ringens Zu dir keret Als vnder augen Angreif in recht mit flaugen wer dich an felt wider reittens der wirt gefelt Hangens zw der erden über greiff in recht mit geperden Zw paiden seitten Dw in an ler dich alle wider reitten Ab du wilt reiten Ross lauffs zw der anderen seÿten Dÿe sterck schütte An setz da mit in nöte wer wert dir das weit swert vach trag na der handt haß Oder vmb ker geruet zu jagen der were Mit allen künsten Der jagt der schick nach günsten Ab dw ver jagst vnd an danck linck iagst Sein swert auff taste vnd ring stös mit [007r] faste Jagt man rechtens Halt ker vmb wart vechtens Mit armen vahen So mag dir kain schad nachen Dÿe messer nemen Behalten ler an schomen Den vngenatten den starcken In verwant Ir slacher ir stechen verdirbt an als vechten wiltu anfassen Neben reittens soltu nicht lassen Das sunnen zaigen linck ermel treib wiltu naigen Das vor haubt taste Gegen nack drvck sere faste Das er sich swencket vnd selden wider auff gelencket wer dir das rempt vber greiff den der wirt beschempt Druck arem zw haubt Der griff offt satel beraupt wiltu aber dich massen des vahens liecht von dir lassen Ringens den gefangen hin ane schnure Den vor griff merck Der pricht furpas sein sterck ~~~~ |

[105v] dein Sper bericht |

[163r] Dein sper bericht,Gegenreiten mach zu nicht ob es empfalle dein end im abschnalle haw drein nicht zuck, von schneiden linck zu im rucke. Greif im sein rechten, so fechstu in one fechtn das glefen stechn, fechtn sittiglich an hurt lere prechen. ob es sich vorwandelt, das schwert gegen schwert wirt gehandelt, recht vas die sterck, taschen hau du such und merck, lere woll starch schutten allen treffen an far do [163v] mit nöt in Ansetz anfar wers straifft heng im zu dem har wiltu gerüt lanck iagn das sere müt wer das nu wert so windt das aug ver sert wert er das furvas[!] vach zaum und wes nicht las Bedenck die plös suech messer nicht wart klöß zwen strich lere mit lerer hand gegen der wer, der schaffgriff weret, wer sich ringens zu dir keret, als under augen angreif im recht mit flaugen, wer [164r] dich an felt widerreittens der wirt gefelt Hangens zu der erden ubergreif in recht mit geperden zu peiden seittn dw in an ler dich alle widerreiten, ab du wilt reitn roßlauffs zu der andern seitn, die sterck schutte ansetz domit in note wer wert dir das weit schwert vach trag na der hant haß oder umb ker geruet zu iagen der were mit allen kunsten der iagt der schick nach gunsten Ab du veriagst und an danck [164v] linck iagst, sein schwert auff taste und ring stos mit faste iagt man rechtens, halt ker umb wart vechtens, mit armen vohen, so mag dir kein schad nahen Die messer nemen, behalten lere an schomen den ungenanten den starcken in verwant ir schlacher ir stechn verdirbt an als vechtn wiltu ann fassen neben reittens soltu nicht lassen Das sunnen zeigen linck ermel treib wiltu naign das vorhaupt taste gegen nack druck sere faste das er sich sch= [165r] wencket und selden wider auff gelencket wer dir das rempt ubergreiff den der wirt beschempt druck arm zu haupt der griff offt sattle beraupt wiltu aber dich massen das vahens liecht von dir lassen ringens den gefangen hin ane schnure Dein vorgriff merck, der pricht fürpas sein sterck. |

[17r] Dein sper berichte, [17v] Ob sich verwanndlt,das schwert gegenn schwert wirt gehandlt Recht fassen, die sterkh tasten, haw du jm suczhe vnd morchk Lere wol starrkh schitten allen treffen, on vor damit [v]otier jn, Ansecz on vare, strafft heng jm zu dem hare, wiltdu gerürt, lang jagen, das sere muet, wer das im wört. so wind das augen verzort, wört er das furbas, fach zaum vnd roß nit laß, bedenkh die plossen, zeuch messer nit, wart Glossen z[wen] strichen leere, nit lerer hannd geg(en) der wöhre, Der schaffgriff wöhret, wer sich Ringens zu dir keret, als vnnder augen, angreiff in recht mit schlaen, wer dich anfeltet wieder reittens der wirt geföllet hangens zu der erden, vbergreiff in recht mit geprech zubaid seiten, du an jn ler dich all widerreiten, ob du wilt Reitten, Ros lauffens zu der anndern seiten, die sterckh schütt an secz domit, Neten wer wört dir das, weit schwert fach trag nach der hannd Haß oder vmker gerütt zu jag(en) der wer mit allen Kunsten der jagt, der sickh nach gunsten vnd ob [v]er jagest, vnd on dankh linkh jagest, dem schwert auff Taste, vnd fangen stoß serr mit faste Jait man rechtens, halb ker [vnmir] linckhe warte fechtens, mit armen fahen, so mag dir kain schad nahen, Die messer nehmen, behalten lerre an schemen, den ungenant die starck(en) ja verwand(en) jr schla[g(en)] jr stech(en) verderbt an allen fecht(en) [18r] Wilt du ane fassen, Wiltdu aber die maassen, |

Featured Translation |

Nuremberg Transcription (1400s) |

Gotha Transcription (1443) |

Rome Transcription (1452) |

Vienna Transcription I (1480s) |

Salzburg Transcription (1491) |

Krakow Transcription (1510-20) |

Vienna Transcription II (1512) |

Augsburg Transcription II (1553) |

Rostock Transcription (1570-71) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Here begins the Art with the Short Sword in Dueling, of Master Johannes Liechtenauer, God have mercy on him,

|

[60r] WEr abesynnet · |

[48v] Kampffechten hebt sich Hye an

Wer absynnet |

[08v] Hye hebt sich an Maister Johansen Liechtenawers kunst Dem got genädig sey mit dem kurtzen swert zu kampff

Wer absynt |

[105v] ob sich verwandelt |

[199r] Hie hebt sich an der Text unnd die Auslegung des Kampffechtn Text Wer absinet [199v] stechen |

[18v] Fechten Im Harnasch zu fussen

Wer aber synnet [19r] Ort, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This is the wrestling in dueling

|

[61v] Das ist nü von Ringen / etc~ ~ AB du wilt ringen · das swert keyn sper wirt gezukt / Der strich io war nym · sprink vach ringens yle zu ym / link lang von hant slach · sprink weislich vnd den vach / Ab her wil zücken · von scheiden vach vnd drük in / das her dy blöße mit swertes orte vordröße / leder vnde hantschuch · vnder dy awgen dy bloße recht zuch / Vorboten ringen · weislichen zu lere brengen / Zu fleißen vinde ·dy dy starken do mete vinde / In aller lere · den ort kegen der bloßen kere / [60v] WO man von scheiden · swert zücken siet von in beiden / Do sal man sterken · dy schrete eben mete merken / Vor · noch · dy zwey dink · sint alle/ prüfe mit lere abesprink / Volge allen treffen · den starken wiltu sye / effen / Wert her zo zücke · stich · wert her ia zu ym rücke / Ab her lank fichtet · zo bistu künslich berichtet / greift her · auch sterke an · das sciße schißen sigt ym an / Mit synem slaen · harte · schützt her sich · trif ane forte / Mit beiden henden · zum awgen ort lere brengen · Des fürdern fußes · mit slegen du hüten müsest / |

ab du wilt ringñ |

Das sind dye ringen zu champff Ob dw wild ringen |

[105v] der schafgriff weret |

[129r] Die zÿttel weist ringen züm kanff zu fußOb du wilt ringen das schwert genyn [?] wurt gezueckett der stich vernÿm Spring vach ringes eyl zu Im Linck lang von hant schlag Spring weyßlichen dem vach Ob er wil zuecken von scheiden vach vnd drueckenn das er die ploß Mit schwertz ort ver droß Leder vnd hantschuch vnder augen bloß recht suech [129v] Verborgen ringen Weyßlich ler zu springenn Ernstlichen wendte dÿ starcken do mit vber windt In aller lere den ort gen dem gesicht kere Wie man von scheydenn Swert zucken sich von ÿn beydenn So sol man sterckenn die schutten eben recht mercken vor vnd noch dÿ zweÿ ding Bruff weyßlich ler mit ab spring Volg allem treffenn den starckenn wiltu sie effenn Werter so zueck Stich / wert er / zu ym rueck Ob er lang vicht So bistü künstig bericht Griff er auch starck an daß schiessenn gie sich ym an Mit sinem schliechendenn ortt Schutz er sich trifft on vorcht [130r] Mit beden hendenn dein ort zu den ougen lere wendenn des vorderenn fusses Mit schlegenn du hueten muest |

[200r] Von paiden henndenob du mit künst gerest enden, ob es sich verruckht, Das schwert gegen schwert wirt gezuckht, Der stich ia war nimb, Spring vach ringenns eill, zu Im linckh lanng, von hant schlag, Spring weislich und den vach, Aber will zucken von schaiden vach, Und druckh in, das er die plos, Mit schwerts ort verdros Leder unnd hanntschuch unnder augen plös recht [200v] such,Verpotne ringen, Weislich zu lernne Springen, zu schliessen viennde, die Starckhen damit ÿberwinde, in aller lere, Dein ort gegen der plös kere, ~Wo man von der schaiden, schwert zucken sicht von in baiden, so sol man stercken, die schutn eben mercken, Vor und nach die zwai ding, Prief weislich lere mit ob spring Volg ~Allen trefen Den Starcken ~Wil= [201r] tu sÿ effn |

[100v] Ein anders Ob du wilt ringen |

Von Ringen, Ob du wilt ringen, [19v] Ob er linkh ficht, |

[74v] Aber ein losung, wen ir baide schwert oder habt angesetzt, so greif mitt deiner linckenn handt aussenn vber sein lincke vnnd tzeuch denn ort ein, vnnd stich von Vntenn auf in sein lincke dener. [75r] gerst endenn, Ob es sich verrucket,das schwert gegenn schwert würd getzuckett, die sach Je vernim, spring fahe ringes al tzu im, linck lanck von hant schlag, Spring weislich dem fach, Ob er wil tzuckenn, von schaidenn vach tzu truckenn, das er die ploß, mit schwertes ort verdroß, Leder vnnd hantschuch, vnter augenn ploß recht such, verporgenn Ringen, weislich ler tzu springenn, zu schliessenn finde, die starckenn damit vberwinde, In aller ler, den ort gen dem gesicht ker, wie man von schaiden, vntertzuckenn vonn In baidenn, So sol man sterckenn, die schuttẽ ebenn recht merckenn, Vor Nach die tzway dingk, bruf weislich ler mit abspring, Volg allen treffen, den starckenn wiltu sie effenn, Wert er so tzucke, ob er langk vicht, so bistu künstig bericht, reift er auch starck an, das schliessen gesigt im an, mit seinem schleichendenn [!] ort, schützt er sich one forcht, mit beden henden, dein ort tzu den Augen ler wenden, des vordern fusses, mit schlegẽ du hutẽ mussest. |

temp division

In addition to the verses on mounted fencing, several treatises in the Liechtenauer tradition include a group of twenty-six "figures" (figuren)—single line abbreviations of the longer couplets, generally drawn in circles, which seem to sum up the most important points. The precise reason for the existence of these figures remains unknown, as does the reason why there are no equivalents for the armored fencing or unarmored fencing verses.

One clue to their significance may be a parallel set of teachings first recorded by Andre Paurñfeyndt in 1516, called the "Twelve Teachings for the Beginning Fencer".[25] These teachings are also generally abbreviations of longer passages in the Bloßfechten, and are similarly repeated in many treatises throughout the 16th century. It may be that the figures are a mnemonic that represent the initial stage of mounted fencing instruction, and that the full verse was taught only afterward.

Images |

Gotha Version (1443) |

Rome Version (1452) |

Glasgow Version (1508) |

Krakow Version (1510-20) |

Augsburg Version II (1553) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The 1st Figure: Charge from the breast to his right hand. |

[22v] [1] Jag võ der prust zu seiner rechtñ hant |

[7v] Die erst figur Jag von der prust zu seiner rechten hand |

[74r] 1 Jag von deiner prust zw seiner rechten handt |

[165v] |

||

| The 2nd Figure:

Turn around with the horse, pull his right hand with your left. |

[2]

vmbker mit roß sein rechte hant mit deyner lincken |

Die ander figur

Vmbkere mitt dem Rozz Zewch sein rechte handt mitt deiner lingken |

2

Vmb ker mit dem roß / zeuch sein rechte handt mit deiner lincken |

|||

| The 3rd Figure:

Upon the encounter, take the stirrup-strap or the weapon. |

[3]

mit stechñ satel In oder ver plent |

Die dritt figur

Mitt strayffen Satel ryem • oder wer nymbe |

3

Mit Straÿffen satel riem / oder wer nymbt |

|||

| The 4th Figure:

Plant upon him high, swing, go through or break the sword. |

[4]

Secz an hoch swenck durch var oder swert pricht |

Die vyerdt figur

Setz an hoch swing durch var • oder Swert prich |

4

Setz an hoch / schwing / durchfar / oder schwert prich |

|||

| The 5th Figure:

The defense precedes all meetings, striking, or thrusting. |

[5]

des schute~ vorgeng allen treffenn hawe~ stechen |

Die funfft figur

Daz schuten vorgeñgk allen treffenn hawen vnnd stechen |

5

Das schutten / vor geng allen treffen / hawen stechen |

|||

| The 6th Figure:

Take the strong with both hands. |

[6]

Greiff mit peyde~ henden an dye strick |

Die sechst figur

Greyff an mitt payden henndten die sterck |

6

Greyff an mit paiden henden die sterck |

|||

| The 7th Figure:

Now begin to seek the opponent with the Slapping Stroke. |

[9]

Hye hebt mã den tasche~ hawe czu such |

Die sybendt figur

Hie heb an den mañ taschen haw zu suechen |

7

Hie heb an den man taschen haw zw suechen |

|||

| The 8th Figure:

Turn his right hand, set the point to his eyes. |

[7]

Went Im dy recht hant secz dein ort czu seine~ gesicht |

Die Achtt figur

Wenndt Im die recht hanndt • setze den ortt zu den augen sein |

8

Went im die recht handt setz dein ortt zw seinem gesicht |

|||

| The 9th Figure:

Who defends against the thrust, grasp his right hand in your left. |

[8]

weyl der stich wert den vahe sey~ rechte hant dey~ lincke |

Die Newnt figur

Wer den stich wertt dem vach sein rechte handt in dein lincken |

9

Wer den stich went dem vach sein rechte handt in dem glincke / |

|||

| The 10th Figure:

Seek the openings: arms, leather, gauntlets, under the eyes. |

[11]

such dy ploß arm dÿ hant scheuch vnter dÿ auge~ |

Die Zechent figur

Suechee die ploss arm leder hanndtschuech vndtir den augen |

11

Suech die plos arm~ leder handt schuech vndter den augen |

|||

| The 11th Figure:

Press hard, push from the reins and seek his messer. |

[10]

truck vast stoß von czam vnd such sey~ meßer |

Die ayndlifft figur

Druck vast stoss von tzawm • sueche sein Messer |

10

Drück vast stoß vom zaüm vnd suech sein messer |

|||

| The 12th Figure:

With the empty hand learn two strokes against all weapons. |

[12]

mit lerer hant lere czwen stich gege~ aller wer |

Die Zwolfft figur

Mitt lerer hanndt lere zwen strich gegen aller were |

12

Mit lerer handt lern straich gegen aller were / |

|||

| The 13th Figure:

The Sheep Grip defends against all wrestling grips under the eyes. |

[13]

Der schaff griff weret alle griff rings vnt° augñ |

Die dreitzechent figur

Der schaf grif wertt • alle griff Ringens vndter augenn |

[74v] 13

Der Schaffgriff werdt alle griff ringes vndter auge~ |

|||

| Direct your spear etc, If it falls etc, Strike in, don't pull, etc.

Pull to his left, grasp in his right, so you catch him there without fencing. |

Dein Sper bericht etc Ob es emphal etc Haw dreyn nichtt Zuckch etcettera

Glosa lingck zu Im ruck • Greyff in sein rechten • so vechst du In ane vechttenn |

|||||

| The 14th Figure:

Turn around again to where the horses hasten. |

[23r] [14]

Anderweyt kere vmb so dy roß hin hurtñ |

[8r] Die viertzendt figur

Anderwayd kere vmb • so die Rozz hynn hurtten |

14

An der weidt ker vmb / so die roß hyn hurttñ / |

|||

| The 15th Figure:

Up close, catch the hand, turn over his face to where the nape is. |

[15]

In der auch so vach dy hant v°ber sein antlicz do der nack ist |

Die funfftzend figur

In der nech vach die hanndt • verkere sein anttlitz da der nack ist |

15

In der nech fach die handt verker sein antlutz do der nacke ist |

[166r] | ||

| The 16th Figure:

Catch the weapon from afar while you ride against him. |

[16]

dye wer fach in der weyt in dem wider treibñ |

Die sechtzechend figur

Die were vach in der weytt • In dem wider Reytten |

16

Die weer fach in der weitt in dem wider reÿttñ |

|||

| The 17th Figure:

If you charge to the left, then fall to the sword pommel, jab under the eyes. |

[20]

Jagstu linck so greiff auff des swertes ploß stoß In vntter augenn |

Daz sybentzechend figur

Jagst du lingk so vall auf Swertes Kloss • stoss vndter augenn |

18

Jagstu linck fall aüfs schwertz knopf stos vndter augen |

|||

| The 18th Figure:

Charge to the right side with its skill. |

[19]

Jag czu seiner rechte~ hant mit Irenn chunstenn |

Die achttzechendt figur

Jage Zu der rechtten hanndt mitt Iren Kunsten |

17

Jag zw der rechtñ handt / mit irñ kunstñ |

|||

| The 19th Figure:

Plant the point upon him to the face. |

[17]

Secz Im dein ort gege~ dem gesicht |

Die Nëwntzechent figur

Setz an den ortt gegen dem gesichtte |

19

Setz an den ortt gegen dem gesicht |

|||

| The 20th Figure:

Shatter against all hits that ever happen. |

[18]

Schut gege~ allenn treffenn dye ÿmer werdenn |

Die tzwaintzigist figur

Schutt gegen allen treffen • Diee ymmer werdenn |

20

Schutt gegen allen treffen die ym~er werdñ |

|||

| The 21st Figure:

The strong in the beginning position yourself therein correctly. |

[23]

dÿ strich zum anhebñ dar Inn schick dich recht |

Die ain vnd tzwayntzigist figur

Die sterck in dem anheben • Dar Inn dich rechtt schicke |

21

Die stercke in dem an hebñ daryn dich recht schick / |

|||

| The 22nd Figure:

He who rushes the spear to the other is met beneath the eyes. |

[24]

das ist nwe der sper lauff der de~ andñ begege~t vnt° augñ |

Die tzwo vnd tzwaintzigst figur

Das ist nun der sper lawff • der dem andern begegendt vndter augen |

22

Das ist nun der sper lauff der dem anderñ begegnet vndter augen / |

|||

| The 23rd Figure:

The Unnamed Grip takes the weapon or fells him. |

[21]

dye vngnnten griff wer nym oder fell In |

Die drey vnd tzwaintzigist figur

Der vngenant griff • wer nymbtt oder velt In |

23

Der vngenant griff weer ny~t oder felt in |

|||

| The 24th Figure:

If an opponent charges you to both sides, turn around left and thus he rightly comes. |

[22]

ob mã dich jagt võ peyde~ seÿte~ ker linck vmb so er rech ku~pt |

Die vier vnd tzwaintzigist figur

ob man dich Jagt zu° bayden seytten kere vmb lingk so er rechtte kumbt |

24

Ob man dich jagt von paidñ seÿttñ ker vmb linck so er recht kumbt |

|||

| The 25th Figure:

Be mindful to take and hold the messer. |

[25]

Der meßer neme~ vnd behaltñ gedenck |

Die funff vnd tzwaintzigist figur

Der Mezzer nemenn • vnd behalden gedenck |

[75r] 25

Der messer nemen vnd behalden gedenck |

|||

| The 26th Figure:

Grasp over an opponent who falls upon you or ride against him. |

[26]

vber greiff wer dich an velt thue In wider treyben |

Die sechßvndtzwaintzigist figur

vbergreif wer dich anvelet • oder thue Im wider Reyttens |

26

Vber greÿff wer dich an felt oder thue im wider reÿttens / |

|||

| If you want to grasp, you should not fail to ride beside him. Execute the Sun Pointer to the left sleeve if you want to bend.

Who attacks you with that, grasp over against him and he will be shamed. Press the arm to the head. This grip often robs the saddle. |

Wild du anfazzen neben reittens nit solt du lasen daz sunnen tzaigen lingk ermel treib wildu naygen

Wer dir daz rembt vbergreifft den der wierd beschämbt druck arm zu haubt der griff offt sattel berawbett |

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

Additional translation notes: In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts ©2010 Freelance Academy Press, Inc.

Additional Resources

- Hils, Hans-Peter (in German). Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes. P. Lang, 1985. ISBN 978-38-204812-9-7

- Tobler, Christian Henry. In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9825911-1-6

- Tobler, Christian Henry. In Service of the Duke: The 15th Century Fighting Treatise of Paulus Kal. Highland Village, TX: Chivalry Bookshelf, 2006. ISBN 978-1-891448-25-6

- Tobler, Christian Henry. Secrets of German Medieval Swordsmanship. Highland Village, TX: Chivalry Bookshelf, 2001. ISBN 1-891448-07-2

- Hull, Jeffrey, with Maziarz, Monika and Żabiński, Grzegorz. Knightly Dueling: The Fighting Arts of German Chivalry. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1581606744

- Wierschin, Martin (in German). Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des Fechtens. Muunich: C. H. Beck, 1965.

- Żabiński, Grzegorz. The Longsword Teachings of Master Liechtenauer. The Early Sixteenth Century Swordsmanship Comments in the "Goliath" Manuscript. Poland: Adam Marshall, 2010. ISBN 978-83-7611-662-4

- Żabiński, Grzegorz. "Unarmored Longsword Combat by Master Liechtenauer via Priest Döbringer." Masters of Medieval and Renaissance Martial Arts. Ed. Jeffrey Hull. Boulder, CO: Paladin Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58160-668-3

- Anzeiger für Kunde der deutschen Vorzeit (in German). Nuremberg: Verlag der Artistisch-literarischen Anstalt des Germanischen Museums, 1854.

References

- ↑ Christian Henry Tobler. "Chicken and Eggs: Which Master Came First?" In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press, 2010. p6

- ↑ A fragment of the short sword is often given as a preamble to the short sword teachings of Martin Huntfeltz, and the figures for the gloss of Jud Lew, but those instances will not be included below and instead treated as part of said treatises.

- ↑ This couplet might instead have been intended to be combined with the previous one as two very long lines of a single couplet: "ettlich biderman in anden hanten veder ben / kunt er chunst er mocht wol eren erwerb".

- ↑ This couplet might instead have been intended to be combined with the previous one as two very long lines of a single couplet: "ettlich in andern hanten verderben / kündt er kunst er möcht ere erwerben".

- ↑ First letter almost illegible.

- ↑ First letter illegible.

- ↑ Text terminates at this point. The leaves with the rest of the text are missing.

- ↑ kam

- ↑ deinen

- ↑ faler

- ↑ There is no space between "Dupliere" and "doniden", the "D" was possibly added later.

- ↑ Corrected from »Im«.

- ↑ The text doubles the title of this section.

- ↑ Corrected from »wir«.

- ↑ Corrected from »twir«.

- ↑ haust

- ↑ These three fragments of lines were probably intended to be combined into a single line: "Zwifach mit macht virbas".

- ↑ Talhoffer adds an additional couplet: [4r] Page:Ms.Thott.290.2º 004r.jpg

- ↑ Hier hat der Schreiber offensichtlich ein Häkchen vergessen.

- ↑ should be "dreffen"

- ↑ This section is followed by one titled "Von durchlauffen ab seczen", which repeat the verse on Absetzen.

- ↑ Illegible word. Could be read as either ‘zo’ or ‘w’. In the glosses on 37r it says ‘zw’.

- ↑ A guide letter “w” is visible under the “U” (apparently ignored by the rubricator), making the intended word “Wer”.

- ↑ Covering a deletion.

- ↑ Andre Paurñfeyndt, et al. Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey. Hieronymus Vietor: Vienna, 1516.