|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Andre Lignitzer"

| Line 1,026: | Line 1,026: | ||

|- | |- | ||

! <p>Images</p> | ! <p>Images</p> | ||

| − | ! <p>{{rating|B|Completed Translation (from | + | ! <p>{{rating|B|Completed Translation (from Rome and Dresden)}}<br/>by [[Keith Farrell]]</p> |

! <p>[[Codex Danzig (Cod.44.A.8)|Rome Transcription]] (1452){{edit index|Codex Danzig (Cod.44.A.8)}}<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ! <p>[[Codex Danzig (Cod.44.A.8)|Rome Transcription]] (1452){{edit index|Codex Danzig (Cod.44.A.8)}}<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ||

! <p>[[Codex Lew (Cod.I.6.4º.3)|Augsburg Transcription]] (1460s){{edit index|Codex Lew (Cod.I.6.4º.3)}}<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ! <p>[[Codex Lew (Cod.I.6.4º.3)|Augsburg Transcription]] (1460s){{edit index|Codex Lew (Cod.I.6.4º.3)}}<br/>by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p> | ||

| Line 1,046: | Line 1,046: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[1] {{red|b=1| | + | | <p>[1] {{red|b=1|Hereafter stand written the pieces with the buckler}}<ref>The Rome version says: “Here begin the pieces with the buckler that the master Andre Lignitzer has written hereafter”.</ref><br/><br/><br/></p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>The first piece with the buckler, from the ''Oberhaw'':<ref>''Oberhaw'' could be translated as “downward cut” for ease of use and clarity in English.</ref> when you drive the ''Oberhaw'' to the man, set your sword with the pommel inside your buckler and at your thumb, and thrust in from below up to his face, and turn against his sword and let it snap-over. This goes to both sides.<ref>This instruction is present in the Dresden version, but missing from the Rome version.</ref></p> | ||

| − | |||

| {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080r.jpg|1|lbl=80r}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080r.jpg|1|lbl=80r}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Cod.I.6.4º.3 084r.jpg|1|lbl=84r}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.I.6.4º.3 084r.jpg|1|lbl=84r}} | ||

| Line 1,074: | Line 1,075: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[2] {{red|b=1|The second | + | | <p>[2] {{red|b=1|The second piece}}</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Item, from the ''Underhaw'':<ref>''Underhaw'' could be translated as “upward cut”. Can be done with the back edge or false edge, and can also be directed either at the man or at the sword. In this stuck, it appears to be a rising action to meet his sword.</ref> when he cuts in at you from above from his right shoulder,<ref>Dresden version specifies from his right shoulder, missing from Rome version.</ref> so turn against him to your left side to your ''schilt'', so that you stand in “two shields”,<ref>The position called the ''schilt'' is one described for longsword in the [[Fechtregeln (MS Best.7020 (W*)150)|Kolner Fechtbuch]] and some of the other ''gemeinfechten'' sources, and is somewhat similar to what Liechtenauer would call an ''Ochs'', although the point can be upward, potentially like quite a high ''Pflug''. With the buckler in the left hand, standing like this in “two shields” with the sword in the ''schilt'' position and the shield covering the right hand, it looks very reminiscent of the ''schutzen'' position in the [[Walpurgis Fechtbuch (MS I.33)|MS I.33]]. Following this line of thinking, the instruction to turn the sword to the right (out of the ''schutzen'') and to reach (slice) through his mouth is very reminiscent of the follow-up action that the MS I.33 recommends from the ''schutzen obsesseo'', and is also similar to what the Liechtenauer ''Zedel'' and glosses refer to as the ''Alten Schnitt''.</ref> then turn uncovered<ref>This instruction to ''wind bloß'' (“turn uncovered”) seems to have the sense of separating your sword and buckler while still pushing with both, keeping the hands more or less in front of the shoulders (as if sitting behind a steering wheel in a car with the hands at the “ten to two” position). The body probably has to move and turn in order to support this action, to keep the hands in front of the body rather than going out to the sides.</ref> to your right side, and reach out to his mouth. If he defends against this and lifts<ref>Dresden has “holds his shield up”, Rome has “lifts his shield up”. Both could mean more or less the same thing, but I prefer “lifts” as an instruction.</ref> his shield up, take the left leg. This goes to both sides.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080r.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,103: | Line 1,104: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[3] {{red|b=1|The third | + | | <p>[3] {{red|b=1|The third piece}}</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Item, from the buckler, from the ''Wechselhaw'':<ref>''Wechselhaw'' could be translated as “changing cut”, because it goes up and down, side to side.</ref> ''Streÿch''<ref>''Streÿchen'' could be translated as “strikes”, but in this context are specifically those striking actions from below, sweeping up with the short edge, perhaps “streaking” up from the ground to the opponent or to his sword.</ref> firmly upward from the buckler from the left side, into his sword, and then cut in from the left side to the head. And turn uncovered,<ref>The same idea of separating your sword and buckler while still pushing both, keeping the hands more or less in front of the shoulders (as if sitting behind a steering wheel in a car with the hands at the “ten to two” position).</ref> and push<ref>Probably with a thrust, but potentially with any other pushing technique.</ref> in to the mouth. If he lifts with shield and sword, and defends against this, then cut with the long edge to the right leg. This goes to both sides.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080r.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080r.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| {{section|Page:Cod.I.6.4º.3 084v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.I.6.4º.3 084v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| Line 1,131: | Line 1,132: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[4] {{red|b=1|The fourth | + | | <p>[4] {{red|b=1|The fourth piece}}</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Item, from the ''Mittelhaw'':<ref>''Mittelhaw'' could be translated as “middle cut”, going across from one side to the other.</ref> make the ''Zwer''<ref>''Zwerch'' could be translated as “across”, in the sense of slanting across from one side to another or slanting across from one height to another, or going diagonally across from one place to another. It also has the sense perhaps of going across something, perhaps slanting across or athwart a boat, or going across your opponent’s blade or leg as opposed to simply coming onto it in whatever fashion. The ''Zwer'' is an example of a ''Mittelhaw'', but it is important to note that the thumb is beneath the blade and the cut is performed with hand high.</ref> to both sides, and the ''Schaittler''<ref>''Schaittler'' could be translated as “parter”, in the sense of being something which parts another thing in two, or dividing something in two.</ref> with the long edge, and thrust in from below to him.</p> |

| | | | ||

{{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080r.jpg|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080v.jpg|1|lbl=80v|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080r.jpg|4|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080v.jpg|1|lbl=80v|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,160: | Line 1,161: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[5] {{red|b=1|The fifth | + | | <p>[5] {{red|b=1|The fifth piece}}</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Item, from the ''Sturtzhaw'':<ref>''Sturtzhaw'' could be translated as “dropping cut”, in the sense of a ball dropping back to earth when it has been thrown upward.</ref> pretend as if you want to thrust over his shield into his left side, and go with the point under and through, and thrust inside his shields<ref>The treatise says ''schilts'', plural, meaning that you thrust inside both sword and shield.</ref> to the body,<ref>Dresden version specifies to the body, missing from Rome version.</ref> and turn ''Indes''<ref>If this gloss follows the Liechtenauer method of understanding the five words ''Vor'', ''Nach'', ''Schwöch'', ''Störck'', ''Indes'' and their relationship to each other, then we should look to the ''Blossfechten'' gloss for the meaning of ''Indes''. However, there is no guarantee that this means exactly the same thing, so the word ''Indes'' could just mean “immediately” when removed from its technical context. There does not seem to be as much ''Winden'' involved with this sword and buckler treatise as there is in the ''Blossfechten'' gloss, although it is still quite possible to perform ''Winden'' with shorter blades (look at Leckuchner’s ''messerfechten'', for example), and Lignitzer was a member of the ''Gessellschaft Lichtenawers'' and so was probably quite well aware of Liechtenauer’s understanding of the five words and how they relate to fighting.</ref> to your left side. If he defends against this, take his right leg with the long edge.</p> |

| {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080v.jpg|2|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,190: | Line 1,191: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p>[6] {{red|b=1|The sixth | + | | <p>[6] {{red|b=1|The sixth piece}}</p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>Item: take the blade to the buckler in your left hand, and turn against him with the half sword. If he cuts or thrusts at you from above to the face or from below to the legs, let your right hand go from the bind<ref>Although both the Dresden and Rome versions say ''bind'', what they probably mean is the fastening of the hand, or the grip upon the sword.</ref> and ''Versetz''<ref>The instruction to ''Versetz'' could mean “to obstruct”.</ref> with shield and with sword, and grip with your right hand to the shield, well below to his right side, and twist out to your right side. Thus, you take the shield from him.<ref>More correctly, both the Dresden and Rome versions say: “Thus, you have taken the shield from him.” However, the sudden change of tense seems a little abrupt and awkward, so I prefer to maintain the same tense as the rest of the instruction, for stylistic reasons.</ref></p> |

| {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080v.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | | {{section|Page:Cod.44.A.8 080v.jpg|3|lbl=-}} | ||

| | | | ||

Revision as of 03:47, 18 May 2020

| Andre Liegniczer | |

|---|---|

| Born | date of birth unknown Legnica, Poland |

| Died | before 1452 |

| Relative(s) | Jacob Liegniczer (brother) |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Movement | Fellowship of Liechtenauer |

| Genres | |

| Language | Early New High German |

| Manuscript(s) |

MS KK5126 (1480s)

|

| First printed english edition |

Tobler, 2010 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

Andre Liegniczer (Andres Lignitzer) was a late 14th or early 15th century German fencing master. His name might signify that he came from Legnica, Poland. While Liegniczer's precise lifetime is uncertain, he seems to have died some time before the creation of Codex Danzig in 1452.[1] He had a brother named Jacob Liegniczer who was also a fencing master,[2] but there is no record of any treatise Jacob may have authored. The only other fact that can be determined about Liegniczer's life is that his renown as a master was sufficient for Paulus Kal to include him, along with his brother, in his list of members of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer in 1470.[2]

An Andres Juden (Andres the Jew) is mentioned as a master associated with Liechtenauer in Pol Hausbuch,[3] and Codex Speyer contains a guide to converting between long sword and Messer techniques written by a "Magister Andreas",[4] but it is not currently known whether either of these masters is Liegniczer.

Andre Liegniczer is best known for his teachings on sword and buckler, and some variation on this brief treatise is included in many compilation texts in the Liechtenauer tradition. He also authored treatises on fencing with the short sword, dagger, and grappling, though these appear less frequently. Liegniczer's sword and buckler teachings are sometimes attributed to Sigmund ain Ringeck due to their unattributed inclusion in the MS Dresden C.487, but this is clearly incorrect.

Contents

Treatises

Note that the Augsburg and Salzburg versions of Liegniczer's treatise on short sword fencing are erroneously credited to Martin Huntfeltz.

Images |

Rome Transcription (1452) |

Augsburg Transcription (1460s) |

Vienna Transcription (1480s) |

Salzburg Transcription (1491) |

Dresden Transcription (1504-1519) |

Glasgow Transcription (1508) |

Krakow Transcription (1535-40) |

Graz Transcription (1539) |

Dresden (Mair) II Transcription (1542) |

Munich (Mair) I Transcription (1550s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

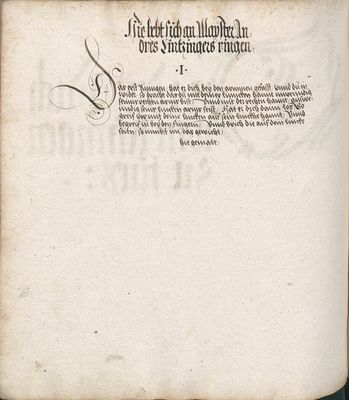

[1] Here you rise to the art of Master Andres, known as the Lignitzer and well respected, in the shortened sword in the ready hand as an effective knightly weapon. Note: take the sword with the right hand on the grip, and with the left grasp the middle of the blade, and go strongly to the man, so he must stab or strike. Indeed, come before to quickly engage forcefully and stay close. |

[73r] ·:~Hÿe hebt sich an Maister Andres Kunst genant der lignitzer Dem got genadig seÿ Das kurtz swert Zw gewappenter hant zu° geleicher ritterlicher were |

[70r] Hie hebt sich an das kurtz swert zum kampff als es meister mertein hundsfelder gesatzt hat. [70v] kumm vor pis resch greiff frölichen vnd pleib nahent. |

[137r] Hie heb sich an das kürtz swert in dem kanpff als es meinster mertein hündsfelder gesait hatt ~

|

[252v] [253r] Nÿmb das schwert, mit der rechten hannt, beÿ dem pinnt, unnd mit der linkchen greif mitten in die clingen, und gee vasst inn man, So mues er stechen oder schlagen, doch kumb vor, pis rasch, greif ferlich, unnd bleib ~ nahenndt. |

[244r] Die Kampfstuckh zü fuo°ß Imm Schwert |

||||||||

[2] The First Play. Note: stab him inward to his face, when he wards you, then drive through and attack him outward to his face. If he wards you again, and so strikes your point off, then twist with your pommel around over his right shoulder, and spring with your right leg behind his left, and throw him back over. |

Item nÿm das swert mit der rechten hant peÿ dem pint vnd mit der lincken greif mitten in die klingen vnd gee vast in man So mues er stechen oder slahen Doch kum vor piß rasch greif färlich vnd pleib nahent ~ |

Item Stich Im Inwendig zum gesicht Wert er dir das So far durch vnd setz Im an außwendig an sein gesicht Wert er dir fürpas vnd streichet dir den ort ab So winde mit deinem knauff Im über sein rechte achseln vnd spring mit deinem rechten pain über sein linckes vnd würffe In über ruck. |

Das erst stuck

Itm~ Stich Im Inwendig zu synen gesicht wirt er dir daß So far durch vnd setz im an außwendig an sin gesicht wirtt er daß furbaß vnd stichet dir den ort ab so wind mit dine~ knopff in vber sin rechte achsell vnd spring mit dine~ rechte~ peyn hinder sin linckes vnd wurff in vber ruck ~ |

Das erst stuckh:~ Stich im innwenndig zu seinem gesicht, wert er dir das, so far durch, unnd setz im auswenndig in sein gsicht, wert er dir das furpas, unnd streicht dir den ort ab, So winnt mit deinem knopf ime, yber sein rechte agsl, unnd spring mit dem rechtn pain, hinter sein linckhs, unnd wirf in ÿberruckhs. |

Item nymb das schwert beÿ Der rechten hannd Beÿ dem pind vnnd mit der linnckh`en greiff Im mitten Inn die klinngen vnnd gee fasst zům Mann so můoß er schlagen oder stechen da kům vor biß Resch greiff Frolichen vnnd bleib nahent |

||||||||

[3] The counter against Note: as one does this to you and has thrust the pommel onto your neck, then from below drive up with the left hand between both his arms, and grab him by his right arm, and force yourself from him on your right side, and throw him over the hip. |

Das erst stuck Item stich ÿm Inwendig zw° seine~ gesicht Wert er dir das So var durch vnd setz ym auswendig in sein gesicht Wert er dir das fürpas vnd streicht dir den ort also ab so wind mit deinem knopf ym vber sein rechte achsel vnd spring mit dem rechten pain hinder sein lincks vnd würf ÿn vber ruck ~ |

Item wer dir das tut vnd hat dir den knauf an den hals geworffen so far mit deiner lincken hant von vnden auf zwischen seinen baiden [71r] armen vnd swing dich dann von Im auf dein rechte seitten vnd würf In über die hüff. |

Ein bruch

Item wer dir daß thut vnd hat dir den knaupff an den hals geworffen so far mit dine~ lincke~ hant von vnte~ avff zwischen sinen peynde~ arme~ vnd schwing dich dan von Im auff din rechte~ site~ vnd wurff yn vber die hueff ~ |

Der bruch Hat er dir den knopf also an den hals geworffen, So var mit der linnckhen hannt, von unnten auf, zwischen seinen baiden armen, und begreif in peÿ seinem rechtn arm, unnd schwing dich von im auf dein recht seittn, und wirf in ÿber die huf. hernach gemalt Stuck und pruch. |

Item stich Im Innwendig zům gesicht wehrt er dir das so far durch vnnd setz Im an aůßwenndig an sein gesicht wehrt er dir fůrbas vnnd streichet dir den ort ab so wennde mit deinnem knopff Im vber seinn rechten Achsel vnnd sprinng mit deinnem Rechten pain vber seinn linnckes vnnd wirff In vber růckh |

||||||||

[4] Yet a counter to the first play Note: when he would thrust his pommel around your neck, then grasp forward with the left hand, and grab behind his right hand onto the grip and take the pommel, and shove it below, and attack him where you wish with your sword. |

Der wider pruch Item wer dir das tu°t vnd hat dir den knopf an den hals geworfen So var mit der lincken hant von vnden auf zwischen seinen paiden arm~ vnd begreif ÿn pey seine~ rechten arm~ vnd swing dich deñ von ym auf dein rechte seitten vnd würff In vber die hüf ~ [73v] Item wenn er dir den knopf vmb den hals wil werfen So greiff mit der linckñ hant von dir vnd greiff hinder sein rechte hant an das pint vnd nÿm den knopf vnd zeuch den vndersich vnd setz ym mit deinem swert an wo du wild |

Item wenn er dir den knauf vmb den hals wil werffen So greiff mit der lincken hant von dir vnd greiff hintter sein rechte hant an das pind vnd nym den knopf vnd zeuch den vnttersich vnd setze Im an mit deinem swert wo du wilt |

Item wan er dir den knopff vmb den hals will werffen So griff mit der lincken hant von dir vñ griff vnter sin rechte hant an daß pntt vnd an den knapff vnd züch den vnder sich vnd setz ÿm an mit dyn schwertt wo dü willt ~ |

[244v] Item wann Er dir den knopff vmb den hals will werffen so greiff mit der linncken hannd von dir vnnd greiff hinder seinn rechte hand ann das pind vnnd nimb den knopff vnnd zeůch den vnndersich vnnd setz Im an mit deinem schwert wa du willt |

|||||||||

[5] A counter against the counter Note: when he has grabbed your pommel, then twist with your pommel up and outward from below around his left hand, and stride ahead with your right leg, and thrust your blade to his left arm. |

Ein pruch da wider den pruch Item wenn er dir knopf begriffen hat So wind mit deinem knopf von vnden auf auswendig vmb sein lincke hant vnd schreit mit deinem rechten pain für dich vnd stos ÿn mit deiner klingen an sein linken arm~ ~ |

Item wenn er dir den knopf begriffen hat So winde mit deinem knauf von vnden auf außwendig vmb sein lincke hant vnd scheube mit deinem rechten pain [71v] fürsich vnd stos In mit deiner clingen an sein lincken arm. |

[137v] Item wen er dir den knaupff begriffen hat So wind mit dine~ knaupff von vnde~ auff außwendig vmb sin lincke hant vnd schub mit dine~ rechte~ pÿn fursich vnd stoß in mit diner clinge~ an sin lincke~ arm |

Item wann Eer dir den knopff begriffen hat so winde mit dennem knopff von vnnden aůf aůßwenndig vmb sein lincke hannd vnnd scheůb mit deinem rechten pain fursich vnnd stoß Inn mit deinner klinngen an sein linncken Arm |

|||||||||

[6] The second play Note: stab him just like the first stab[5] to his face, and go to the second one as if you would stab inward to his face. Just then drive through, and attack him outward to his face when he wards it. Then stride behind his left leg with your right, and thrust him with the hilt in his left armpit, and thrust a little upward so he falls. |

Das ander stuck Item stich ym aber den ersten stich zw seinem gesicht vnd thu°e zw dem anderñ mal als du ym aber Inwendig zw seinem gesicht wöllest stechen Inndes var durch vnd setz ÿm auswendig zw° seinem gesicht an wenn er dir das wert So schreit mit deinem rechten pain hinder sein lincks vnd stoß in mit dem gehültz in sein lincke vchsen vnd stos ein wenig vber sich so veltt er ~ |

Das ander stuck Item Stich Im aber zum ersten stich Inwendig zu seinem gesicht vnd thue zum andern mal als du Im zum gesicht stechen wöllest In des far durch vnd setze Im außwendig zum gesicht Wenn er dir das weret so schreit mit deinem rechten pein hintter sein linckes vnd stos In mit dem gehültz In sein lincke üchsen vnd stos Inwendig über sich so velt er. |

Das ander stueck

Item Stich ÿn vber den ersten stich inwendig zu sin gesicht vnd thün zu dem andern mall als du ÿm aber zu dem gesichtt stechen wilt Indes far durch vnd satz ÿm vswendig zu sine~ gesicht wen er dir dz werett so schrit mit dine~ rechte~ pey~ hinder sine~ lincks vnd stos ÿn mit dem gehultz in sin lincke vchschen vnd stoß inwendig so felt er ~ |

[254r] |

Das annder stückh Item stich Im aber zům ersten Innwenndig zů sein nem gesicht vnnd thů zům anndern mal alls dů Im zů dem gesicht stechen wollest Indes far důrch vnnd setz Im aůßwenndig zům gesicht wenn er dir das wehret so schreit mit deinnem Rechten pain hinder sein linnckes vnnd stoß In mit dem gehůltz Inn sein Linkcke Vchsen vnnd stoß Inwendig vbersich so fellt er |

||||||||

[7] The counter against Note: if one does this to you, then stride with your left leg behind you, and block the thrust on the blade between both your hands, and twist with the pommel from below up between both his arms, and twist your pommel up from below over his left hand, and spring with your left leg behind his right, and thrust the whole sword over his neck, thus you have won his back. |

Der widerpruch Item wer dir das tu°t So schreit mit deinem lincken pain hinder dich vnd vach den stos zwischen dein paide hende in die klingen vnd wind mit dem knopf von vnden auf zwischen sein paide [74r] arm~ vnd wind mit deine~ knopf von vnden auf vber sein lincke hant vnd spring mit deine~ lincken pain hinder sein rechtz vnd stos ÿm paide swert vber sein hals So hastu ÿm den ruck an gewunnen ~ |

Bruch Item wer dir das tut So schreitt [72r] mit deinem lincken pain hinttersich vnd vach den stos zwischen dein baide hende In die klingen vnd wind mit dem knopff von vnten auf über sein lincke hant vnd spring mit deinem lincken pain hintter sein rechtes vnd stos Im beide swert über sein hals So hastu den ruck angewunnen etc. |

Item wo er dir daß thutt so schrit mit dine~ lincke~ peyn hinder dich vnd vohe den stoß zwüschen din beyde hant in die clingen vnd wind mit dem knaupff von vnde~ auff zwischen vber sin lincke hant vnd spring mit dine~ linck peyn hintter sin rechtes vnd stoß ÿm beÿde swertt vber sin hals so hastu ÿm den rueck an gewunen ~ |

[254v] |

[245r] Bruch Item wo er dir das thut so shcreit mit deinnem Lincken pain hidersich vnnd fach den stöß zwische deinne baide hennd Inn die klingen vnnd winnd mitt dem knopff vonn vnnden aůf zwischen sein baid Arm vber sein linncke hannd vnnd spring mit deinem linncken pain hinder sein Rechts vnnd stoß Im baide schwert vber sein hals so hastů Im den Růckh abgenommen |

||||||||

[8] A further counter against this Note: as one would thrust the whole sword over your neck, then openly stand with your right leg still, and let go of your sword's grip, and with your right arm grasp around his back, and pull him by the middle, thus you throw him. |

Ein wider pruch wider den Item wer dir paide swert über den hals wil stossen So stee freÿleich still mit deinem rechten pain vnd laß dein swert faren peÿ dem pind vnd greif mit deinem rechten arm~ hinden vmb seinen ruck vnd ruck ÿn peÿ der mitt So wurfstu in an zweifel ~ |

Widerpruch Item wer dir beide swert über den hals wil stossen so stee streitlich still mit deinem rechten pain vnd las dein swert farn pej dem pind vnd greiff mit deinem rechten arm hintten vmb sein ruck vnd ruck zu dir So hastu In on zweifel etc. |

Widerprüch Item wer dir bede schwert vber den hals woll stossen So stee streitlich still mit deinnem rrechten pain vnnd laß dein schwert faren beÿ dem půnd vnnd greiff mit deinnem rechten Arm hinder vmb sein Růcken vnd růckh zů dir so hastů In on zweifel |

||||||||||

[9] The third play Note: stab him inward to his face, and just then drive through the other's stab, and stab him outward to the face, but if he wards this, then stride with the left leg between both of his, and with your pommel reach outside over his left leg to his knee joint, and stand yourself with the left shoulder up hard onto him, and lift yourself up strongly, and push to his left side. |

Das dritt stuck Item stich ÿm aber Inwendig zu° seinem gesicht vnd var in dem anderñ stich durch vnd stich ym auswendig zw dem gesicht Wert er dir das aber So schreit mit dem lincken pain zwischen seine paide vnd greif mit deinem knopff aussen vber sein lincks pain in sein knÿepüg vnd leg dich mit der lincken achsel oben fast in ÿn vnd heb vnden fast auf vnd druck auf sein lincke seitten ~ |

[72v] Das dritt stucke Item Stich Im aber zu seinem gesicht Inwendig vnd far In dem andern stich durch vnd stich In außwendig zum gesicht. Weret er dir das aber So scheub mit deinem lincken pain zwischen sein beide pein vnd greiff mit deinem knauff aussen über sein linckes pein In sein kniepüg Vnd leg dich mit deiner lincken achseln oben vast vmb In vnd heb vnden vast auff vnd druck auf sein lincke seitten. |

Das drÿtt stuck

Item Stich im aber zu sinem gesicht in wenig vnd far in den andern vnd stich ÿm vßwendig zu sine~ gesicht wirtt er dir daß aber So schub mit dem lincken peyn zwueschen sin beÿde hende vnd griff mit dine~ knaupff außen vber sin linckes peyn in sin knÿepug vnd leg dich mit diner lincke~ achsell oben fast vmb yn vnd hebe vnt fast auff vnd truck auff sinen lincke sytenn ~ |

Stich im aber innwenndig zu dem gesicht, und var in dem anndern stich durch, und stich im auswenndig zum gsicht, wert er dir das aber, So schreit mit deinem linnckhen pain zwischen sein baide, und greif mit dem knopf, aussen ÿber sein linnckhs pain in sein kniepug, unnd leg dich mit der linckhen agsl, oben fast in in, und heb unnthen fast auf, und druckh auf sein linckhe, seitn. |

[245v] Das dritt stuckh Item stich Im aber zu seinnem gesicht Innwendig Vnnd far Inn dem anndern stich durch vnnd stich In aůßwenndig zů dem gesicht wehret er dir aber das so scheůb mit deinnem lincken pain zwischen seine baiden pain vnd greiff mit deinnem knopff aůssen vber sein linkcks pain Inn sein kniepůg vnnd leg dich mit deiner linncken Achsel oben fast vmb In vnnd heb vnnden fast aůf vnnd trůckh aůf seinn lincken seiten |

||||||||

[10] The counter against Note: if he will drive the pommel to your knee joint then grasp with your left hand to his arm behind his left hand, and grasp with your right hand from below up around his elbow, so that your fingers stand above, and throw him on his face. |

Der widerpruch Item wer dir mit dem chnopf wil varen in die knÿepüg dem greif mit deiner lincken hant hinder sein lincke hant peÿ dem arm~ vnd greif mit dein° rechtñ [74v] rechten hant von vnden auf ÿm an den elpogen vnd das dein vinger oben ste vnd würf yn auf das maul ~ |

Item wer dir mit dem knauf wil farn In die kniepüg dem greiff mit deiner lincken hant hintter [73r] sein lincke hant pej dem arm vnd greiff mit deiner rechten von vnden auf Im an den elnpogen vnd das dein vinger oben steen so würfstu In auf das antlütz etc. |

[138r] Item Wer dir mit dem knaupff will faren in die knÿebug dem griff mit diner lincken hant hintter sin lincke hant bÿ dem arm vnd griff mit diner rechte~ von vnte~ auff ÿm an den elnboge~ vnd das din finger oben sten so wuerfftü ÿnauff daz antlutz |

Der Bruch. Wer dir mit dem knopf will faren ine die kniepug, dem begreif, mit deiner linnkchen hannt, hinter sein linckhe hannt beÿ, dem arm, unnd greif mit deiner rechtn, hant von unthen auf, ime an den elbogen, Unnd das dein vinger oben stee, unnd wirf in auf das maul. Stuck Und Pruch |

Item wer dir mit Dem knopf will faren Inn die kniepug dem greiff mit deiner linnckhen hannd hinder sein lincken hannd beÿ dem Arm vnd greiff mit deinner Rechten von vnnden aůf Im an Elnpogen vnnd das dein fin ger oben steen so wirfstů In aůf das Antlitz |

||||||||

[11] The fourth play Note: when you stab him inward to the face, and he also to you, then strike flat against his sword, and grab his sword in your hand by the blade and set your point in him under his left shoulder, if he wards this, and also grabs your sword like you have his, then work from a wrench which stands described (below) as you wish. |

Das vierd stuck Item wenn du Im Inwendig zw dem gesicht stichest vnd er dir wider So sich eben auf sein swert vnd begreiff sein swert pey der klingen in die hant vnd setz im den ort an vnder sein lincks vchsen Wert er dir das vnd begreifft dir dein swert auch als dw das sein hast So arbait aus einem reissen als hernach geschriben stet aus wellichem du wild |

Das vierd stuck Item wenn du Im Inwendig zum gesicht stichest vnd er dir wider So gang eben auf sein swertt vnd begreiffe sein swert pej der clingen In die hant vnd setz In des den ort an vntter sein lincke üchsen Wert er dir das vnd begreifft dir dein swert auch als du das sein hast So arbeit auß einem reisßen als hernachgeschrieben stet etc. |

Die vierde stuck

Item Wen dü ÿm Inwendig zu dem gesicht stichest vnd er dir wider so gang oben auff sin swertt vnd begriff sin schwertt py der clinge~ in die hãt vnd setz Indes den ort an vnter sin lincke vchsen Wertt er dir daß vnd begrifft din swertt auch als du das syn hast so arbeÿtt auß eyne~ riessen als hernach geschriben statt ~ |

[256v] |

[246r] Das viert stückh Item wann du Im Innwendig zum gesicht stichst vnnder dir wider so ganng eben aůf sein schwert vnnd begreiff sein schwert bey der klinngen Inn die hannd vnnd setz Inndes den ort an vnnder sein lincken Vchslen wehrt er dir das vnnd begreifft dir dein schwert aůch alls dů das seinn hast so arbait aůß ainnem Reÿssen alls hernach geschriben steet |

||||||||

[12] The first wrench Note: stab him inward to the face, if he wards this, and sets your stab aside, then twist your pommel up from below on your left side, and up over his sword's blade between both his hands, and wrench strongly to you. Thus you wrench his left hand from his blade, then stab him to the torso, if he is too strong and you can't wrench his hand from the sword, then twist the pommel still up from below on your right side over his left hand, and thrust the blade from you to his left side. |

Das erst reißen Item stich ÿm Inwendig zw dem gesicht Wert er dir das vnd setzt dir den stich ab So wind mit deine~ knopf von vnden auf auf deine lincke seittñ vnd oben vber sein swertz klingen zwischen sein paide hend vnd reiß vast an dich So reistu in sein lincke hant von der klingen So stich ÿm denn zw° dem gemächt Ist er dir zw starck das dw Im die hant von dem swert nicht gereissen magst So wind mit deinem knopf aber von vnden auf auf dein rechte seittñ vber sein lincke hant vnd stos in mit der klingen in sein lincke seitten von dir ~ |

[73v] Das erst reissen Item Stich Im Inwendig zum gesicht Weret er dir das vnd setzt den stich ab So winde mit deinem knauf von vnden auf dein lincke seitten von oben über sein swertz clingen zwischen seinen baiden henden vnd reisß vast an dich so reistu Im sein lincke hant von der clingen vnd stich Im den zum gemechtt Ist er dir zu starck das du Im die hant vom swert nicht gereissen machst So winde mit deinem knauf aber von vntten auf dein rechte seitten über sein lincke hant vnd stos In mit der clingen In sein lincke seitten von dir etc. |

*[138v] Das ander reissen

Item Stich ÿm Inwendig zu dem gesicht wirtt er dir dz vnd setz dir den stich ab So wind mit dine~ knaupff von vnden auff din lincke site~ von oben nider in sin swertz clingen zwische~ sin beyde~ hende~ vnd rüßt an dich So rieß im sin lincke hant von der clingen vnd stich ÿm dan zu dem gemecht ist er dir zü starck dz du ÿm die hant vom dem swert nit geriessen magst So wind mit dine~ knaupff aber von vnden auff / auff din rechte site~ vber sin lincke hant vnd stos yn mit der clingenn in sin lincke site~ haulb von dir dan ~ |

[257r] |

Das erst Reÿssen Item stich Im Innwendig zům gesicht wehrt er dir das vnnd setzt den stich ab so winnde mit deinem knopf von vnnden aůf dein linncken seitten vnd oben vber sein schwerts klingen zwischen seinnen baiden hennden vnnd reÿß fast an dich so reist dů Im sein linncken hannd von der klinngen vnnd stich Im denn zům gesicht Ist er dir zu starckh das dů Im die hannd vom schwert nit reÿssen magst so winde mit deinnem knopff aber von vnnden aůf dein rechte seiiten vber sein lincke hannd vnnd stoß In mit der klingen Inn sein linncken seitten hart von dir danne |

||||||||

[13] The second wrench Note: stab him inward to his face, but twist with the pommel from your left side up from below over his blade between his hands and wrench strongly to you, and then stab him to the torso, if he wards this and fights your sword, and does so that both swords are caught, then thrust your sword's pommel around his right side, and spring with your right leg behind his left, and take the back, and lift across him with fingers high above the ground, and hit with your right foot outward to his right ankle, and throw him onto his right side. |

[75r] Das ander reÿssen Item stich ÿm Inwendig zu° seinem ge [75r] sicht vnd wind aber mit dem knopf auff dein lincke seitten von vnden auf vber sein klingen zwischen seiner hant reÿß aber vast an dich vnd stich ÿm aber zu° seinem gemäch Wert er dir das vnd vecht dir das swert vnd dw das sein das paide swert gefangen sein So würff dein swert mit dem knopf ÿm in sein rechte seitten vnd spring mit deinem rechten pain hinder sein lincks vnd nym den ruck vnd heb in deñ eines tzwerchen fingers hoch von der erden vnd slach in mit deinem rechten fueß auswendig an sein rechten enckel vnd wurff in auf sein rechte seitten ~ |

[74r] Das ander reisßen Item Stich Im Inwendig zum gesicht vnd wind aber mit dem knauf auf dein lincke seitten von vntten auf über sein klingen zwieschen seiner hant reiß aber vast an dich stich Im zu seinem gemecht. Wert er dir das vnd fecht das swert dir vnd du auch das sein das baide swert gefangen sein So würff dein swert mit dem knopf Im In sein rechte seitten vnd spring mit deinem rechten pain hintter sein linckes vnd nym den ruck vnd heb In eins zweren vingers hoch auf von der erden vnd slag In mit deinem rechten fus außwendig an sein rechten enckel vnd würfe In auf sein rechte seitten. |

*[138r] Das erst reissen

It~ Stich Im Inwendig zu sine~ gesicht vnd wind aber mit dem knaupff auff din lincke siten von vnden auff vber sin clingen zwischen siner hant / reisß aber vast an dich stich ÿm zü syne~ gemecht wertt er dir dz vnd fach dir dz schwe~t vnd du daß sin dz beÿd swe~t gefange~ syn So würff din swert mit dem knaupff ym In sin rechte site~ vnd spring mit dine~ rechte~ peyn vnder sin linckes vnd nÿm den rueck vnd heb ÿn hoch auff von der erden vnd schlag In mit dinem rechte~ fuß außwendig an / an sine~ rechte~ enckel vnd wurff ÿn auff sin rechte syte~ ~ Sr das and~ riessen |

[257v] |

[246v] Das annder Reyssen Item stich Im Innwendig zům gesicht vnnd winnd aber mit dem knopff aůf dein Linncken seitten von vnden aůf vber sein klinngen zwischen zwischen seinner hannd Reÿß aber fast an dich stich Im zů seinnem gemecht wehrt er dir das vnnd fächt dir dz schert vnnd dů aůch das sein das baide schwert gefanngen seind so wirff dein schert mit dem knopff Im Inn sein rechte seitten vnnd spring mit deinem Rechten pain hinnder sein linnckes vnnd Nimb den růckh vnnd heb In ainnes zwern fingers hoch aůf von der erden vnnd schlag In mit deinnem rechten fůoß Aůßwenndig an sein rechten ennckel vnnd wirff zu aůf sein rechten seitten |

||||||||

[14] The third wrench Note: do to him just like as described above, and if both swords become caught, then thrust around over the head on his right side, and spring with the right leg behind his left, and with your right hand grab him by his left rear fauld, and with the left hand grab up from below to his bevor, and pull below to you, and thrust up from you, so he falls on his back. |

Das dritt reÿßen Item thu°e ÿm geleich als oben geschriben stet vnd ob paide swert gefangen wärñ So würf ÿm aber den knopf in sein rechte seitten vnd spring mit dem rechten pain hinder sein lincks vnd greiff in mit deiner rechten hant ÿn pey seine~ lincken arspacken vnd greiff mit dein° lincken hant von vnden auf ym an seinen kinpacken vnd zeuch vnden an dich vnd stos oben von dir So felt er an den ruck |

[74v] Das dritt reissen Item thue Im gleich als oben geschrieben stet vnd ob die baide swert gefangen wern so würff Im aber dein knauf In sein rechte seitten vnd spring mit dem rechten pein hintter sein linckes vnd greif Im mit deiner rechten hant In pej seinem arschpacken vnd greiff mit deiner lincken hant von vnden auf Im an sein kinpacken vnd zeuch vnden an dich vnd stos oben von dir So felt er an den ruck etc. |

[138v] Das tritt reissenn

Item Dün im glich als oben geschreben stott vnd ob beÿde swert gefangen wer So würff ÿm aber sÿn knaupff in sin rechte site~ vnd spring mit dine~ rechte~ peÿn hinder sin lincke vnd griff im mit diner rechte~ hant in sÿn peÿde ars backen vnd grif mit diner lincken hant von vnte~ auff ÿm an sin kÿnbacken vnd zuch vnden an dich vnd stos oben von dir so felt er an den rueck ~ |

[258r] |

Das dritt Reÿssen Item thüo Im Gleÿch als ob geschrinben steet vnnd ob die paide schwert gefanngen weren so wirff Im aber dein knopff Inn sein rechten seitten vnnd sprinng mit dem rechten pain hinder sein linckes vnnd greiff Im mit deinner rechten hannd In beÿ seinem Arßbacken vnnd greiff mit deiner lincken hannd von vnnden aůf Im an sein kinpacken vnd zeůch vnden an dich vnnd stoß oben von dir so felt er ann den Růcken |

||||||||

[15] The counter against Note: if one drives with the left hand under your bevor, and has you by the left rear fauld with his right hand, and would throw you over backward, then grasp with your left hand up around his left, and grab him by the fingers, and break his hand away to the left side, and drive with your right hand on his left elbow, and take his weight. |

Der widerpruch Item wer dir mit der lincken hannt vert vnder den kinpacken vnd dich [75v] mit seiner rechten hant pey dem lincken arspacken hat vnd wil dich vber ruck werffen So greif mit deiner lincken hant ÿm auf sein lincke vnd begreif ÿn peÿ den fingerñ vnd prich im die hant auf dein lincke seitten vnd var mit deiner rechtñ hant an sein lincken elpogen vnd nÿm im das gewicht ~ |

Der vierd pruch Item wer dir mit der lincken hant fert vntter den kinpacken vnd dich [75r] mit seiner rechten hant pej dem lincken arschpacken hat vnd will dich über ruck werffen So greiff mit deiner lincken hant Im auff sein lincke vnd begreiffe In pej den vingern vnd prich Im die hant auf dein lincke seitten vnd far mit seiner rechten hant an sein lincken elnpogen Vnd nym Im das gewicht |

Der vierde bruch

Itm~ Wer dir mit der lincken hant fert vnder din kÿnbacken vnd nÿmpt dich mit diner rechte~ hant peÿ dem lincken arsbacken vnd wil dich vber rueck werffen So griff mit diner lincken hant ÿm auff sin lincke vnd griff In bÿ den fingern vnd prich ÿm die hant auff din lincke site~ vnd var mit dsiner rechte~ hant an sin lincken elnboge~ vnd nÿm ÿm dz gewiechtt ~ |

[258v] |

[247r] Der viert Bruch Item wer dir mit der Lincken hannd fert vnnder Dein kin packen vnnd dich mit seinner Rechten hannd beÿ dem glinncken Arßbacken hat vnd wilt dich vber růckh werffen so greiff mit deinner linncken hannd Im aůf sein lincke vnnd begreiff In beÿ den finngern vnnd brich Im die hannd aůf dein linncken seitten vnnd far mit seinner rechten hannd an sein linncken Elenpogen vnd Nimb dz gewicht |

||||||||

[16] The fourth wrench Note: this is if both swords are caught, then thrust your pommel up around his right side, and spring with your right leg behind his left, and grab him with your left hand behind his left hand on his arm, and with your right hand grab him by the elbow and take the weight. |

Das vierd reÿssen Item ist das aber paidew swert gefangen sein So würf ÿm aber deinen knopf in sein rechte seitten vnd spring Im mit dem rechten pain hinder sein lincks vnd begreif in mit deiner lincken hant hinder seiner lincken hant peÿ dem arm~ vnd greif mit deiner rechten hant in peÿ seinem elpogen vnd nÿm das gewicht ~ ~ |

Das vierd reissen Item ist aber das baide swert gefangen sein Würffe Im aber deinen knauf In sein rechte seitten vnd spring Im mit deinem rechten pain hintter sein linckes vnd begreiff In mit deiner lincken hant pej dem arm vnd greiff mit deiner rechten hant In pej seinem [75v] elnpogen vnd nÿm Im das gewichte. |

[139r] Daß vierd reÿssen

Item Ist aber das peÿd schwertt gefange~ sin würff ÿm aber din knaupff in sin rechte site~ vnd spring ÿm mit dinem rechte~ peyn hintter sin linckes vnd begriff ÿn mit diner lincken hant peÿ dem arm vnd griff mit diner rechte~ hant ÿn beÿ sinem elnboge~ vnd nÿm Im daß gewiecht ~ |

[259r] |

Das viert Reyssen Item ist aber das baide schwert gefanngen sein Wirff Im aber deinnen knopff Inn sein rechte seitten vnnd sprinng Im mit deinnem Rechten pain hinder seinn Linnckes vnnd begreiff In mit deinner linccken hannd beÿ dem Arm vnnd greiff mit deinier Rechten hannd In beÿ seinnem Elenpogen vnnd Nemb Im das gewicht |

||||||||

[17] The fifth wrench Note: when he has caught your sword, and you his, then go through both swords on his left side, then twist outward around his sword so that he must let yours go, if he holds his sword and lets yours go, then do as if you would stab him to the torso, if he wards this, and grabs at the sword with his left hand, then stab below through his sword on his right side around over his right arm onto his chest, thus you break his sword around out of his hand, then thrust his sword with the point toward him, and attack with your sword in the high guard. |

Das fünfft reÿssen Item wenn er dir dein swert gefangen hat vnd du das sein So gee durch paidew swert auf dein lincke seittñ So windestu ÿm sein swert aus das er dir das lassen mues Helt er denn sein swert vnd lest dir das dein So thu°e als dw In zw° dem gemächt wöllest stechen Wert er dir das vnd greift mit sein° lincken hant nach dem swert So stich vnden durch sein swert auf sein rechte seitten ÿm vber sein rechten arm~ an sein prust so prichstu ÿm sein swert [76r] aus seiner hant So würf sein swert mit dem ort gegen ÿm vnd mit deine~ swert fall in die öber hu°t ~ |

Das funfft reissen Item wenn er dein swert gefangen hat vnd du das sein So gee durch beide swert auf dein lincke seitten so gewinstu Im sein swert aus das er dir das lassen muß Behelt er denn sein swert vnd lest dir das dein So thue sam du Im zum gemecht wöllest stechen Wer er dir das vnd greifft mit seiner lincken hant nach dem swert So stich vnden durch durch sein swert auf sein recht seitten Im über sein rechten arm an sein prust so prichstu Im sein swert aus seiner hant so würff sein swert [76r] mit dem ort gegen Im vnd mit deinem swert falle In die obern hut etc. |

Das fünfft reyssenn

Itm~ Wan er din swertt gefangen hat vnd du dz sin so ge durch beyde swert auff din lincke site~ So gewinestü ÿ~ sin swert auß dz ers dir also loßen müß behelt er dan sin swertt vnd lest dir dz din So tün sam dü ÿm zu dem gemecht stechen wolst wertt er dir dz vnd griff mit siner lincke~ hant noch dem swertt So stich vnte~ durch durch sin swert auff sin rechte sitenn ÿm vber sin rechte~ arm an sin rechte prust So prichstu ÿm sin swe~t auß siner hant So wurff sin swert mit dem ortt gegen ÿm vnd mit dine~ swertt vall in die obern huett |

[247v] Das Fünft Reÿssen Item wann Er dein Schwert gefanngen hat vnnd dů das sein so gee důrch baide schwert auf die linncken seiten so gewinndstů Inn dein schwert ab das er dirslassen můoß behellt er dann seinn schwert vnnd last dir das deinn so thůo samm dů Im zum gemecht wollest stechen wehret er dir das vnnd greifft mit seinner Linncken hannd nach deinnem schwert so stich vnnden důrch seinn schwert aůf sein Rechten seitten Im vber seinn Rechten Arm ann seinn průst so prichstů Im sein schwert aůß seiner hannd so wirff seinn schwert mit dem Ort gogen Im vnnd mit deinnem schwert fall Inn die obern hůt |

|||||||||

[18] The counter against Note: if one does this to you, and will stride through both swords to you, then thrust both swords over his neck, and make them shears. |

Der widerpruch Item wer dir das thu°et vnd dir durch paidew swert lauffen wil So stos ÿm paide swert vber den hals vnd mach die scher ~ |

Der widerpruch Item wer dir das tut vnd dir durch bede swert lauffen wil Stos Im pede swert über den hals vnd mach dich scher. |

Ein bruch

Item wer dir dz thuett vnd dir dürch peÿde~ swertt lauffen will / Stoß ÿm beyde swertt vber den hals vnd mach die scher ~ |

[260v] |

Der widerprüch Item wer dir das thut Vnnd dir důrch beide schwert důrchlaůffen will stoß Im baide schwert vber den hals vnnd mach die scher |

||||||||

[19] |

|||||||||||||

[20] A counter against the counter Note, when he has made shears, then in the bind grab up from below with your right hand behind his right so that your fingernails are above and thrust your sword hard from you on your left side, and turn yourself against him also on your left side and twist your pommel out over his right hand, and hit him where you will with the pommel and the hilt. |

Ain widerpruch wider den pruch Item wenn er dir die scher hat gemacht so greif mit deiner rechten hant von vnden auf hinder sein rechte in das pindt das dein negel an den fingerñ vbersich sten vnd würf denn dein swert vast von dir auf dein lincke seitten vnd ker dich gegen ÿm auch auf dein lincke seittñ vnd wind mit seinem knopf aussen vber sein rechte hant vnd slach ÿn mit dem knopf vnd mit dem gehültz wo dw hyn wild ~ |

Ein widerpruch Item wer dir die scher hat gemacht So greiff mit deiner rechten hant von vnden auf hintter sein rechte In das pinde das dein negel an dein vingern oben steen Vnd würff denn dein swert vast von dir auff [76v] dein lincke seitten vnd kere dich gegen yn auf dein lincke seitten vnd winde mit deinem knauf aussen über sein rechte hant vnd slage In mit dem knopf vnd mit dem gehültz wo du wilt. |

Ein wider brüch

Item Wer dir die scher hat gemacht so griff mit diner rechte~ hant von vntte~ auff hintter sin rechte~ in daß peÿn / daß den negell vnd den fingern [139v] oben sten vnd würff den din swertt fast von dir auff din lincke site~ vnd ker dich gegen ÿm auch auff din lincke site~ vnd wend mit dine~ knopff aussen vber sin rechte hant vnd schlag ÿn mit dem knaupff vnd mit dem gehultz wo dü willtt |

[248r] Einn widerprüch Item wer dir die scher hat Gemacht so greiff mit deinner rechten hannd von vnnden aůf hinnder sein rechten Inn das pinde das dein negel an den fingern oben steen vnnd wirff dein schwert fast vonn dir aůff deinner Lincken seitten vnnd kere dich gogen Im aůf dein Linncken seitten vnnd winde mit deinnem knopf aůssen vber sein rechte hannd vnnd schlag In mit dem knopff vnnd mit dem gehůltz wo dů wildt |

|||||||||

[21] The sixth wrench Note, when both the swords are caught, then thrust the pommel hard from you on your right side, and up around his left side and spring with your right leg behind his left, and grasp with your right hand up from below to his right armpit, and so lift his sword upward, thus you throw him to your right side which is the best, and the last of the wrenches. |

Das sechst reissesn Item wenn die swert paide gefangen sein so würf den chnopf vast von dir auf dein rechte seitten vnd ym auff sein lincke seitten vnd spring mit deinem rechten pain hinder sein lincks vnd greif mit deiner rechten hannt von vnden auf in sein rechte vchsen vnd heb mit seine~ swert vber sich So würfstu in auf dein rechte seitten das ist das pest vnd das letzt vnder den reÿssen |

Das sechst reissen Item wenn die swert beide gefangen sein So würff dein knopff fast von dir auf dein rechte seitten vnd Im auf sein lincke seitten vnd spring mit deinem rechten pain hintter sein linckes Vnd greiff mit deiner hant von vnden auf Im In sein rechte üchsen vnd heb mit seinem swert übersich So würfestu In auf sein rechte seitten, das ist das pest vnd letzt vntter den reissen |

Das sechst reÿssenn

Itm~ Wen die schwertt beyd gefange~ sint so wurff den knoupff fast von dir auff dine rechte site~ vnd auff sin lincke site~ vnd spring mit dine~ rechte~ peyn hinter sein linckes vnd griff mit diner hant von vnte~ auff ÿm In sein rechte vchsen vnd heb mit dine~ swertt vber sich So wurfstu ÿn auff sein rechte syten dz ist dz best vnd dz lest vnder den reÿssen ~ |

[261r] |

Das sechst Reyssen Item wann die schwert baide Gefanngen sein so wirff dein knopff fast vonn dir aůf dein rechte seitten vnnd spring mit deinnem rechten pain hinnder sein Linnckes vnd greiff mit deinner hand von vnnden aůf Im Inn sein rechte Vchsen vnd heb mit seinnem schwert vbersich so wirfstů In aůf sein rechte seitten dz ists pöst vnd letzt vnder den Reyssen |

||||||||

[22] This is but a play Note, if he breaks through to your torso, then stab him first also to the torso, The second stab, stab from above down over his left hand between both arms, and twist the pommel up from below to his right side, stride with your left leg behind his left, and throw him over your thigh(?). |

[76v] Das Ist aber ein stuck Item sticht er dir zw dem gemächt So stich im auch zw dem gemächt einen stich Den anderñ stich Stich von oben nÿder vber sein lincke hant zwischen sein paiden arm~ vnd wind mit dem knopf von vnden auf in sein rechte seitten schreit mit deine~ rechten pain hinder sein lincks vnd würf In vber dein diech ~ |

[77r] Das ist aber ein stuck Item Sticht dir einer zum gemecht So stich Im auch zum gemechtt einen stich Den andern stich von oben nider auf sein lincke hantt zwischen sein beiden armen vnd wind mit dem knauff von vntten auf In sein rechte seitten Schreit mit deinem rechten pain hintter sein linckes vnd würffe In uber den dich. |

Das ist ein stück

Item Sticht dir eyner zu der gemecht so stich ÿm auch zu dem gemecht eine~ stich den andern stich von oben nider auff sin lincke hant zwischen sein beyde~ armen vnd wind mit dem knopff von vnte~ auff ÿn sin rechte site~ / Schrit mit dine~ rechten peyn hinter sine~ linckes vnd wurff in vber de~ rueck |

[261v] |

[248v] Das ist aber ain stückh Item sticht dir ainer zům gemecht stich Im aůch zů dem gemecht einenr stich den anndern stich von oben nider aůf sein linncken hannd zwischen seinnen baiden armen vnnd winnd mit dem knopff vonn vnnden aůf Inn sein rechte seitten schreit mit deinem rechten pain hinder sein linnckes vnd wirff In vber den diech |

||||||||

[23] The counter against Note, if one does this to you then let your sword go from the blade, and grasp with your left hand behind and over his shoulder, and grab your sword once again by the blade, and pull him close to you, and swing yourself from him on your right side |

Der widerpruch Item wer dir das tu°t so laß dein swert gen pey der klingen vnd greif mit deiner lincken hant hinden vber sein schulter vnd begreif dein swert wider peÿ der klingen vnd druck yn vast zu° dir vnd swing dich von Im auf dein rechte seittñ ~ |

Der widerpruch Item wer dir das tut So las dein swert gen pej der clingen vnd begreiff mit deiner lincken hant über sein scheilter [?] Vnd begreif dein swert wider pej der clingen vnd [77v] druck yn vast zu dir vnd swinge dich von Im auf dein rechte seitten. |

Ein brüch

Item wer dir thutt so loß din swertt gen peÿ der clinge~ vnd begriff mit diner lincken hant hinten vber sin schultern vnd begriff din swe~t wider bÿ der clinge~ vnd druck ÿn vast zu dir vnd schwing dich von ÿm auff din rechte sÿtenn ~ |

[262r] |

Der widerprüch Item wer dir das thüet so laß dein schwert geen beÿ der klinngen vnnd greiff mit deinner linncken hand hinden vber sein schůlter vnnd begreiff dein schwert wider beÿ der klinngen vnnd trůckh In fast zů dir vnnd schwinng dich von Im aůf dein rechten seitten |

||||||||

[24] Yet a play Note, if he works high with you, and stabs you to the face, then stab up from below between both his arms, and over his left shoulder, grasp with your left hand behind his left, and thrust your sword's grip onto your left shoulder, and grasp with your right to his left elbow hard up from below, and take his weight, then the sword stays under his left arm and between both of yours. |

Aber ein stuck ☹ Item arbait er mit dir hoch vnd sticht dir zw dem gesicht So stich von vnden auf zwischen seinen paiden armen vnd vber sein lincke achsel begreiff ÿn mit deiner lincken hant hinder seine° linckñ vnd würf dein swert mit dem pint auf dein lincke achsel vnd greif mit deiner rechten in sein lincken elpogen stos vast von vnden auf vnd nÿm ÿm das gewicht So pleibt das swert vnder seinem lincken arm~ zwischen ewer paider ~ |

[77v] Aber ein stuck Item arbeit er mit der höhe vnd sticht dir zum gesicht So stiche von vnden auf zwischen sein baiden armen vnd über sein lincke achsel Begreiff In mit deiner hant hintter seiner lincken vnd würff dein swert mit dem pind auf dein lincke achseln vnd greiff mit deinem rechten Im an sein lincken elnpogen Stos vast von vnden auf vnd nym das gewicht so bleibt das swert vntter seinem lincken arm zwischen ewer beider. |

[140r] Ein stueck

Item Arbeÿt er mit dir hoch vnd stich dir zu dem gesicht so stich von vnte~ auff zwischen sine~ beÿde~ armen vnd vber sin lincke achsell / begriff ÿm mit diner hant hintter seyne lincke vnd wurff din schwe~t mit dem pÿntt auff din lincke achsell vnd griff mit diner rechte~ ym yn sin rechte~ elnboge~ / stoß vast von vnte~ auff vnd nim dz gewichtt so plybt dz swe~t vnder seyne~ lincken arm zwüschen uwer peÿde~ ~ |

[262v] |

[249r] Aber ainn stückh Item arbait er mit der hoche vnnd sticht dir zů dem gesicht so stich vonn vnnden aůf zwischen seinnen baiden Armen vnnd oben sein linncke Achsel begreiff In mit deinner hand hinnder seinner linncken vnnd wirff dein schwert mit dem pind aůf dein linncen Achselen vnd greiff mit deinner Rechten Im an seinnen linncken Elennpogen stoß fast von vnnden aůf zwischen seinnen baiden armen vnnd Nim das gewicht so bleibt das schwert vnnder seinnem linncken Arm zwischen ewůr baider |

||||||||

[25] Yet a play Note, if he works high with you, then stab up from below between both his arms, and let your left hand drive from the blade, and grasp over his sword's weak, and grip your sword by the blade again and then thrust both swords well above over his neck back and behind him to both knee joints, and wrench well below to you, and with your head thrust well ftom you so you throw him onto his back. |

Aber ein stuck [77r] Item arbait er aber hoch mit dir So stich aber vnden auf zwischen sein paidñ arm~ vnd laß dein lincke hant varñ von der clingen vnd greif oben vber sein swert vasch vnd begreif dein swert wider pey der clingen vnd stos ÿm paide swert denn vber den hals hinden vber seinen rucken gar obhin in sein paide knÿepüg vnd reiß vast vnden an dich vnd mit dem haubt stos oben vast von dir so würfstu In auf den ruck ~ |

[78r] Aber ein stuck Item arbeit er aber hoch mit dir So stich aber vnden auf zwischen sein beide arme vnd las dein lincke hant farn von der clingen vnd greiff oben über sein swert resch Vnd begreiff dein swert wider pej der clingen vnd stos Im bede swert denn über den hals hintten über sein rucke gar abhin In sein beide kniepüg vnd reiß vast vntten an dich Vnd mit dem haubt stos oben vast von dir So würfstu In auf den ruck. |

Aber ein stück

Item Arbeit er aber hoch mit dir so stich aber vnte~ auff zwuschen sine~ beÿde~ armen vnd loß din lincke hant varn von der clingen vnd griff obñ zu vber din swertt riesch vnd begriff din swe~t wider bÿ der clinge~ vnd stos ÿm beÿde swertt vber den hals hinten vber sin ruck gar ab hÿn ÿn sein beÿd knÿebug vnd reiß vast untte~ an dich vnd mit dem haupt stoß vast von dir so wurfstu ÿn auff den ruck ~ |

[263r] |

Aber ainn stuckh Item arbait Er aber höch Mit dir so stich aber vnnden aůf zwische seinne bed Arm vnnd laß dein linncke hannd faren von der klinngen vnnd greiff oben zů ober sein schwert vnnd begreiff dein schwert wider beÿ der klinngen vnnd stoß Im baide schwert vber den hals hinnden vber sein růcken gar abhin Inn seinne baide kniepůg vnnd Reyß gast vnnden arm dich vnnd mit dem haůpt stoß oben gast von dir so wirfstů Inn aůf den rucken |

||||||||

[26] A counter against it Note, if one does this to you, and will thrust both swords over your neck, then drive with the right hand to his left side around his back, and stride with your right leg ahead in front of his left leg, and throw him over your hip. This goes for both sides. |

Ein pruch da wider Item wer dir das tu°t vnd wil dir paide swert vber den hals stosen So var mit deiner rechten hant In sein lincke seittñ vber seinen ruck vnd schreit mit deine~ rechten pain vorñ für sein lincks pain vnd würf in vber die hüff Der pruch get zw paiden seitten ~ |

Ein pruch dawider Item wer dir das tun wil vnd [78v] wil dir baide swert über den hals stossen So far mit deiner rechten hant In sein lincke seitten über sein ruck vnd schreit mit deinem rechten pain forn für sein linckes pain vnd würffe In über die hüff Der pruch geet zu baiden seitten zu etc. |

Ein bruch dar wider

Itm~ Wer dir dz thün will vnd will dir die beÿde swe~t vber den hals stoßen so far mit diner rechtenn hant in sein lincke site~ vber sin ruck vnd schrit mit dine~ rechte~ peÿn vorn fur sein linckes peÿn vnd würff yn vber die hueff der bruch gett zu beÿden site~ zu° ~ |

[263v] |

[249v] Ein prüch darwider Item wer dir das thon will Vnnd will dir baide schwert vber den hals stössen so far mitt deinner rechten hannd Inn seinn linncken seitten vber den Růckh vnnd schreit mit deinnem rechten pain forn fůr seinn linncks pain vnnd wirff In vber die hůff der grůch geet zů baiden seitten zů |

||||||||

[27] Yet a play Note, stab him inward to the face, and then in the left hand hold his sword by the blade against your sword, and twist the pommel up from below behind his right hand, and then lift hard upward, and then wrench to your right side, thus keeping his sword on your right arm. This is a sword taking. |

Aber ein stuck Item stich ym Inwendig zw dem gesicht vnd begreiff denn sein swert peÿ der clingen zw deinem swert in dein lincke hant vnd wind mit dem knopf von vnden auf hinder sein rechte hant vnd heb denn vast vber sich vnd reÿß denn auf dein rechte seitten So pleibt dir sein swert auf deinem rechtñ arm~ das ist das swert nemen ~ |

[140v] Ein stueck

Item Stich ÿm Inwendig zu dem gesicht vnd begriff dan syn swert peÿ der clinge~ zu deinem swertt in din lincke hant vnd windt mit dine~ knaupff von vnte~ auff vber sin rechte hant vnd heb dan vast vber sich vnd reiß den auff din rechte~ site~ So blytt dir din swe~t auff dem rechte~ arm das ist dz swert nemen |

[264r] |

Aber ainn stuckh Item stich Im Innwenndig zům gesicht vnnd begreiff seinn schwert beÿ der klinngen zů deinnem schwert Inn dein linncken hannd vnnd winnd mit deinnem knopff von vnnden aůf vber seinn rechte hannd vnnd heb dann fast vbersich vnnd reÿß dann aůf dein Rechte seiten so bleibt dir dein schwert aůf deinnem Rechten arm das ist das schwertnemen |

|||||||||

[28] Yet a play Note, when you advance to him, stab him outward to the face, and with the left hand grasp his sword's blade between both his hands, and let your own sword fall, and with your right hand grip behind his left also on his sword's blade, and with your right hand jerk his sword hard to your right side, then grab with your left hand down from below between both his arms behind around his right hand on his grip, and wrench his pommel up from below between both his arms, thus you take his sword. |

Aber ein stuck [77v] Item wenn du ÿm ein laufst so stich ÿm auswendig zw dem gesicht vnd greif mit dein° lincken hant Im zwischen sein paide hende in sein swertz klingen vnd laß denn dein swert fallen vnd greif mit dein° rechten hant hinder sein lincke auch in sein swertz clingen vnd druck mit deiner rechten hant sein swert vast zw dir in dein rechte seitten So greif denn mit deiner lincken hant von oben nÿder zwischen seiner paider arm~ ÿm hinder sein rechte hant in sein pint vnd wind denn mit seinem chnopf von vnden auf zwischen sein paide arm~ so nÿmpstu Im sein swert ~ |

[79r] Aber ein stuck Item wenn du Im ein lauffest So stich Im außwendig zu seinem gesicht vnd greiff mit der lincken hant Im zwischen sein beide hende In sein swertz klingen Vnd las denn dein swert fallen vnd greif mit deiner rechten hant hintter sein lincke auch In sein swertzclingen vnd truck mit deiner rechten hant sein swert fast zu dir In dein rechte seitten so greiff denn mit deiner lincken hant von oben nider zwischen sein baiden arm So nympstu Im das swert |

Aber ein stueck

Itm~ Wan dü ÿm ÿn lauffest so stich ÿm vßwendig zu° sinem gesicht vnd griff mit dÿner lincken hant ÿm zwuschen sin |

[264v] |

[250r] Aber ainn stückh Item wann du Im einlaůffest so stich Im aůßwenndig zů seinnem gesicht vnnd greiff mit der linnckhen hand Im zwischen seinn baid hennd Inn sein schwert klingen vnnd laß dein schwert fallen vnnd greiff mit deinner rechten hannd hinder sein linncke aůch Inn sein schwerts klinngen vnnd tzůckh mit deinner rechten hannd sein schwert fast zů dir Inn dein rechte seitten so greiff dann mit deinner linncken hand vonn oben nider zwischen sein baid arm So nimpstů Im das Schwert |

||||||||

[29] A counter against Note, if one does this to you, and takes your sword, and would twist out, Then grasp with your right hand behind his right, and your left hand behind his right elbow, then you have him around his back. |

Ein wider pruch Item wer dir das tu°t vnd dir das swert nemen vnd auswinden wil So greif mit deiner rechten hant hinder sein rechte vnd mit deiner lincken hinder sein rechten elpogen So gewingstu ÿm den ruck an |

Ein widerpruch Item wer dir das tut vnd dir [79v] das swert nemen vnd auß winden wil mit deiner rechten handt hintter sein rechte vnd mit deiner lincken hintter sein rechten elnpogen So gewinstu Im den ruck an |

Ein wider brüch

Item Wer dir daß thutt vnd dir dz swert will nemen vnd auß winden will mit dyner rechten hant sin rechte vnd mit dÿner hintter sin rechten elnbogen So gewinstu Im den ruck ann |

Ainn widerprüch Item wer dir das thüt Vnnd dir das schwert nemen vnnd aůßwinnden will mit deinner rechten hannd hinder seinn rechte vnnd mit deinner lincken hinnder sein rechten Elenpogen so gewinstů Im ab den růckh |

|||||||||

[30] Yet a play Note, when you both fight around the sword, then strive so that you have your left hand behind his right on his grip, and your right hand between both his hands on his sword's blade, then grip with your left hand behind his right, and then grasp with your right from below up under his right arm, and stride with your right leg behind his left if he pulls the leg behind himself, then stride between both his legs, and thrust his arm to his left side from you with your left hand, and with your right arm shove him on his right arm, and a little upward on your right side so he falls. |

Aber ein stuck Item wenn ir paide vmb ein swert kriegt So tracht das dw hast dein lincke hant hinder seiner rechten in seinem pint vnd dein rechte hant zwischen seiner peiden hendt in seiner swertz klingen So begreif in denn mit deiner lincken hant hinder seinem rechten vnd greif denn mit deiner rechten von vnden auf vnder sein rechten arm~ vnd schreit mit deinem rechten pain hinder sein lincks [78r] Zucht er das pain hindersich So schreitt zwischen seine paide pain vnd stos ÿm dann sein arm~ mit der lincken hant von dir auf dein lincke seitten vnd zeuch Im mit der rechten hant sein rechten arm~ vast an dich vnd ein wenig vber sich auf dein rechte seitten so feltt er ~ |

Aber ein stuck Item Wenn ir baide vmb ein swert kriegt So tracht das du habst dein lincke hant hintter rechten In seinen pind vnd In dein rechte hant zwischen seiner pej der (?) hende In swertzclingen So begreiff In denn mit deiner lincken hant In seiner rechten vnd greif denn mit deiner rechten von vnden auff vntter sein rechten arm vnd schreit mit deinem rechten pein hintter [80r] sein linckes. Zuckt er das pain an sich so schreit zwischen sein bede pein vnd stos Im denn sein arm mit deiner lincken hant von dir auf dein lincke seitten vnd zeuch Im mit der rechten sein rechten arm fast an dich vnd einwendig übersich auff dein rechte seitten. |

Aber ein stuck

Itm~ Wan ir beyde vmb ey swert vmb ein schwert kryegt So tracht dz dü chabpst din lincke hant hintter [141r] sÿner rechten in sÿnem bÿndt Vnd din rechte hantt zwueschen seinen beÿden hende~ in sÿns schwerts clingen So begriff ÿn dan mit dÿner lincken hant yn syne rechte vnd griff dan mit dÿner rechte~ von vnte~ auff sein rechte~ arm vnd schrytt mÿt dyne~ rechte~ peÿn hÿnder synen lÿnckes / zueck er das pein hindersich So schrÿtt zwueschen sÿn beyde peyn vnd stos ÿn dan sÿn arm mit diner lincken hant von dir auff din lincke sytenn vnd zuch ÿn mit der recht / sÿn rechte~ arm vast an dich vnd ein wenig vber sich vff din rechte sÿtenn |

[265r] |

[250v] |

||||||||

[31] Here you rise to the mortal strike The first mortal strike: step close to him, and do as if you would stab him inward to the face, and then let your right hand drive from the grip, and thereby come to help the left hand on the sword's blade, and strike him with the pommel or with the hilt, or with the grip to his head. |

Hÿe heben sich an die mortschleg Der erst mortschlag · trit vast In in vnd tu°e sam dw in Inwendig zw dem gesicht wellest stechen vnd laß denn dein rechte hant varen vonn deinem pint vnd kum do mit deiner lincken hant zw° hilff in die swertz klingen vnd slach in mit dem knopf oder mit dem gehültz oder mit dem pint zu° seine~ haubt ~ |

Hie heben sich an die mortschlege. Item der erst mortslag Triff fast In yn vnd thue sam du Inwendig zum gesicht wöllest stechen [80v] las dann dein rechte hant faren von deinem pind vnd kumme damit deiner lincken hant zu hilff In die swertz clingen vnd slahe In mit dem knopf oder mit dem gehültz oder mit dem pind zu seinem haubt. |

[265v] |

[251r] Die Mortschleg

Item der erst Mortschlag Tritt fast Inn In vnnd thůe sam dů Im Inwendig zum gesicht wollest stechen laß dan dein rechten hannd faren von deinnem pind vnnd kom damit deinner linkcen hannd zů hilff Inn die schwerts klinngen vnnd schlag In mit dem knopff oder mit dem gehůltz oder mit dem pind zů seinnem haubt |

|||||||||

[32] A counter against it Note, if one strikes to your head, then block the strike between both hands on your sword's blade, and twist the pommel to your left side over his hilt, and pull close to you, thus forcing his sword out of his hands. |

Ein pruch do wider Item wer dir zw dem kopff slecht So vach den slack zwischen deine~ paiden henden in dein swertz clingen vnd wind mit dem knopf auf dein lincke seitten vber sein gehültz vnd ruck vast an dich So zeuchstu im das swert aus seinen henden ~ |

Hie heben sich an die mortschlege. Item der erst mortslag Triff fast In yn vnd thue sam du Inwendig zum gesicht wöllest stechen |

[266r] |

Ain prüch darwider Item wer dir züm kopff schlecht so fache den schlag zwischen deinne baid hend Inn dein schwerts klinngen vnnd wind mit dem knopff aůff dein linncken seitten vber sein gehůltz vnnd zeůch fast an dich so zeůchst Im das schwet aůß seinnen hennden |

|||||||||

[33] The second mortal strike <pNote, stab him inward to his face, but let your sword drive with the grip, and now grasp your sword with both hands on the blade, and strike him with the pommel to the left shoulder. |

Der ander mortschlagk Item stich ym aber Inwendig zw dem gesicht vnd laß aber dein swert varñ [78v] mit dem pindt vnd begreif aber dein swert mit paiden henden peÿ der clingen vnd slach ÿn mit dem chnopf zw der lincken achsel ~ |

Item Stich Im aber Inwendig zum [81r] gesicht vnd las aber dein swert farn mit dem pind vnd begreiffe aber dein swert mit beden henden pej der clingen vnd vach Im mit dem knauf zu der lincken achseln. |

[266v] |

[251v] Item stich Im aber Innwendig zům gesicht vnnd laß aber dein schwert faren mit dem pind vnnd begreiff aber dein schwert mit baiden hennden beÿ der klinngen vnnd fach In mit dem knopff zů der lincken Achseln |

|||||||||

[34] A counter against it Note, block the strike on the blade between both your hands, and twist the pommel down over his hilt from above, and pull close to you, thus you take his sword just like before. |

Ein pruch da wider Item vach den slagk zwischen dein paide hend in die clingen vnd wind mit dem knopf von oben nÿder vber sein gehultz vnd ruck vast an dich So nÿmpstu ÿm aber sein swert als vor ~ |

Der ander mortschlag Item vah den slag zwischen beide hende In die clingen vnd windt mit dem knauff von oben nider über sein gehültz vnd ruck vast an dich So nympstu Im aber das swert als vor etc. |

[267r] |

Der annder Mortschlag Item fach den schlag zwischen baiden hennd Inn die klinngen vnnd winnd mit dem knopff von oben nider vber sein gehiltz vnnd růckh fast ann dich so nimpst dů Im aber das schwert alls vor |

|||||||||

[35] The third mortal strike The third mortal strike is done to his left elbow, and counter it the same way as the two earlier counters. |

Der dritt mortschlagk Den dritten mortschlagk den thu°e zw seinem lincken elpogen vnd den prich als dw die vorigen zwen geprochen hast |

Der dritt mortslag Item den du zu seinem lincken elnpo= [81v] gen den prich als du die vorgenantten zwen geprochen hast |

[267v] |

Der dritt Morttschlag Item den thüo zů seinnem linncken Elenpogen den prich als dů die vorgenamment zwen geprochen hast |

|||||||||

[36] The fourth mortal strike Note, do as if you would stab to his face, and strike with the pommel to his left knee joint. |

Der vierd mortschlagk Item tu°e sam dw In zw° seinem gesicht wöllest stechen vnd slach in mit dem knopf an sein lincke knÿepüg ~ |

Der vierde mortslag Item thue als du Im zum gesicht wöllest stechen vnd slahe In mit dem knauff an sein lincken kinpack. |

[268r] |

[252r] Der viert Mortschlag Item thüo alls dů Im zům gesicht wollest stechen vnd schlag In mit dem knopff an sein linncken kinpacken |

|||||||||

[37] The counter against it If one strikes to your left knee joint, then block the strike on your sword's blade between both your hands, so that your pommel stands toward the ground, and twist up from below on your right side, and pull hard behind you, thus you take his sword. |

Der pruch da wider Wer dir zw der lincken knÿepüg slecht So vach den slagk zwischen dein paide hend in dein swertz clingen vnd das dein knopf gegen der erden stee vnd wind auf dein rechte seittñ von vnden auf vnd ruck vast hindersich So nÿmpstu ÿm sein swert ~ |

Der ander pruch dawider Item wer dir zum lincken kinpack schlecht So fah den slag zwischen dein baid hende In die swertzclingen Vnd das der knopf gegen der erden stee Vnd wind von vntten auf dein rechte seitten vnd ruck fast [82r] hinttersich So benÿmpstu Im das swert etc. |

[268v] |

Der annder prüch Darwider Item wer dir zum Lincken Kin packen schlect so fach den schlag zwischen deinne beed hennd Inn die schwerts klinngen vnnd das der knopff gogen der erden stee vnnd wind von vnnden aůf dein rechten seitten vnnd růckh fast hinnder sich so nimstů dz Schwert |

|||||||||

[38] The fifth mortal strike Note, do as if you will attack him inward to his face, and strike him with the pommel below to his left ankle. |

Der fünfft mortslagk Item tu°e aber sam du ÿm wilt an setzen [79r] Inwendig in das gesicht vnd slach In mit dem knopf nÿden in seine~ lincken enckel |

Der funfft mortslag Item thue aber Sam du Im wilt ansetzen Inwendig In das gesicht vnd slahe In mit dem knauf vnden an sein lincken enckel. |

[269r] |

[252v] Der Fünnfft mortschlag Item thůo aber sam du Im wolst ansetzen Innwendig zum das gesicht vnnd schlagInn mit dem knopff vnnden an seinnen enckel |

|||||||||

[39] A counter against it Note, if one strikes to your left ankle, then let your sword drive by the pommel, and with the grip to the ground, thus you fight the strike with the hilt, and spring quickly with your right leg behind his left side, thus you win his back. |

Ein pruch da wider Item wer dir zw dem lincken enckel slecht So laß dein swert varñ pey dem knopf vnd mit dem pint in die erd So vechstu den slagk in das gehultz vnd spring rasch mit deine~ rechten pain hinder sein lincke seitten So gewinstu ÿm den ruck an |

Der pruch dawider Item wer dir zum enckel slecht so las dein swert vorn pej dem knauf vnd mit dem pind In die erde So vechstu den slag In das gehültz vnd spring resch mit deinem rechten pein hintter sein lincke seitten so gewinstu Im den ruck an. |

[269v] |

Der průch darwider Item wer dir zům Enckel schlecht so laß dein schwert vornen beim knopff vnnd mit dem pind Inn die Erde so fachstů den schlag Inn das gehůltz vnnd sprinng resch mit deinnem rechten pain hinnder sein linncken seitten so gewinstů Im den růckh ab |

|||||||||

[40] Four attacks Go quickly to him, and attack him to the face, or to the throat, or to the chest, or under his left armpit. |

Vier an setzen Gee rasch in In vnd setz ÿm an sein gesicht oder an den hals oder an sein prust oder vnder sein linckes vchsen ~ |

[82v] Vier ansetzen Item Gee In yn vnd setz Im an sein gesicht oder an den hals oder an sein prust oder vntter sein linckes ṽchsen. |

[270r] Vier ansetzen. Gee rasch in ine, Unnd setz im an sein gesicht, Oder ann hals, Oder an seinn prust, Oder unnder sein linckh ÿgsen. |

[253r] Vier ansetzen Item gee Resch Inn In vnnd setz Im an sein gesicht ofer an den hals oder an seinn průst oder vnnder sein linncke vchsen |

|||||||||

[41] A counter If he attacks you with his sword to your chest, then drive with the left hand down from above to his sword, and hold it fast by the point, and then stab your sword behind his left leg, and shove with your chest a little ahead of you and extract your body off of his point, and thrust with your left hand under his face, or on his chest back over your sword. |

Ein pruch Hat er dir an gesetzt mit seine~ swert an dein prust So var mit der lincken hant von oben nÿder auf sein swert vñ halt das vest peÿ dem ort vnd stich den mit deine~ swert hinder sein lincks pain vnd schewb mit deiner prust ein wenig für dich vnd zuck denn deinen leib pald ale aus seinem ort vnd stos ÿn mit deiner lincken hant vnder sein gesicht oder an sein prust hinder sich vber dein swert ~ |

Ein pruch Item hat er dir angesetzt mit seinem swert an dein prust So far mit deiner lincken hant von oben nider auf sein swert vnd halt das vest pej dem ort vnd stich dem mit deinem swert hintter sein linckes pein vnd scheub mit deiner prust ein wenig für dich vnd ruck denn deinen leip bald auß seinem ort Stos In mit deiner lincken hant vntter sein gesicht oder an [83r] sein prust hinttersich über dein swert. |

Hat er dir an prust anngesetzt. Hat er dir in die prust angesetzt, mit seinem schwert, so var mit der linnckhenn hannt, von oben nider, auf sein schwert, unnd halt das vesst beÿ dem ort, unnd stich denn mit deinem schwert hinnter sein linnckhs pain, unnd scheub mit deiner brust ein wennig fur dich, Unnd zuckh deinnen leib palt aus seinem ort, Unnd stos in mit deinner linnckhen hannt under sein gesicht, oder an sein prust, hinntersich ÿber dein schwert. |

Ainn prüch darwider Item hat er dir angesetzt Mit seinnem schwertz an dein průst so far mit deinner linncken hannd von oben Nider aůf sein schwert vnnd halt das feest beÿ dem Ort vnnd stich den mit deinnem schwert hinnder sein linnckes pain vnnd scheůb mit deinner průst ainwenig fur dich vnnd ruckh denn deinner leib bald aůß seinnem Ort [253v] Stoß In mit deiner Linncken hannd vnnder seinn gesicht oder ann seinn průst hinndersich vber dein schwert |

|||||||||

[42] A second counter Note, if he attacks your face, and you also to him, then stab with your sword behind his gauntlet, and step ahead of yourself to his left side. |

Ein ander pruch Item Hat er dir aber an gesetzt vnd du ÿm auch So stich mit deine~ swert hinder [79v] seinen Hantschu°ch vnd lauf für dich auf sein lincke seitten ~ |

Item hat er dir aber angesetzt vnd du Im auch So stich mit deinem swert hintter seinen hantschuch vnd lauff für sich auff dein lincke seitten etc. |

Ein ander Bruch. Hat er dir aber an gesetzt unnd du im auch, so stich mit deinnem schwert, hinter seinen hanntschuch, und lauf fur dich auf sein linckhe seitn. |

Item hat er dir aber angesetzt vnnd dů Im aůch so stich mit deinnem schwert hinnder seinnen henndschůch vnnd laůf fůrsich aůs dein linncken seitten |

|||||||||

[43] But a closing Note, when both your swords have engaged, then grasp with your left hand out over his left, and wrench his point once, and stab up from below to his left armpit(?). |

Aber ein lösung Item wenn ir paide swert habt an gesetzt So greif mit deiner lincken hant aussen vber sein lincke vnd zeuch den ort ein vnd stich von vnden auf in sein lincken tenär ~ |

Aber ein losung Item wenn ir baide swert habt angesetzt So greiff mit deiner lincken hant aussen über sein lincke vnd zeuch den ort ein vnd stich von vnden auf In sein lincken tener. |

[270v] |

Aber ainn Loßüng Item wann Ir beed das schwert habt angesetzt so greiff mit deinner linncken hannd aůssen vber seinn linncke vnnd zeůch den Ort ein vnd stich vonn vnnden aůf Inn seinn linncken seitten |

|||||||||