|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Hans Talhoffer

| Hans Talhoffer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Occupation |

|

| Patron |

|

| Movement | Marxbrüder (?) |

| Genres | |

| Language | Early New High German |

| Archetype(s) |

|

| Manuscript(s) |

MS KK5342 (1480-1500)

|

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

| Signature |  |

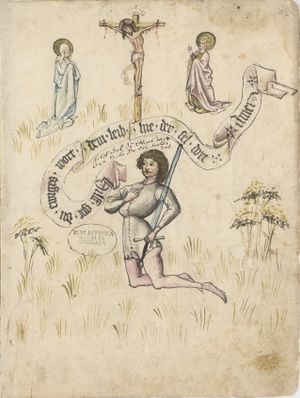

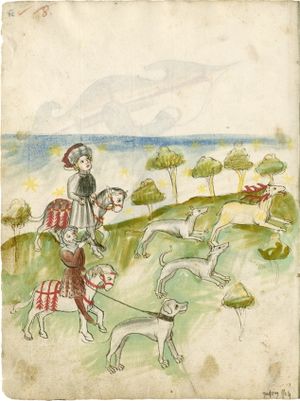

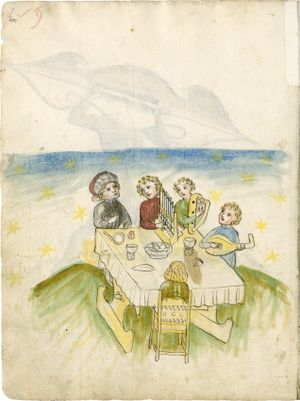

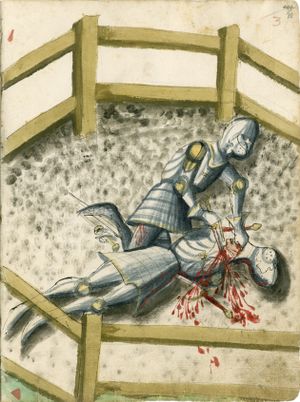

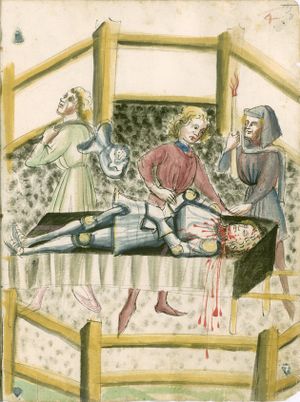

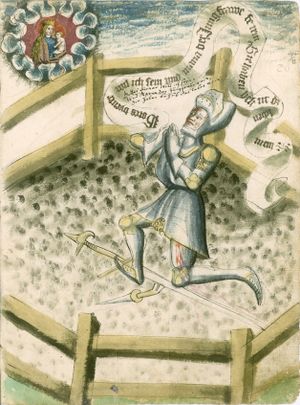

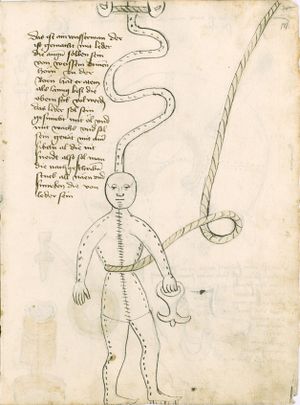

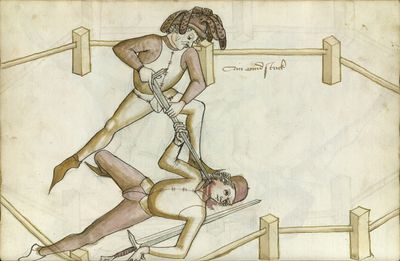

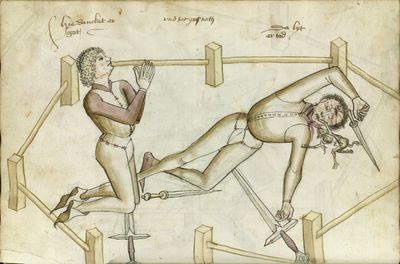

Hans Talhoffer (Dalhover, Talhofer, Talhouer, Thalhoffer; fl. 1433-67) was a 15th century German fencing master. His martial lineage is unknown, but his writings make it clear that he had some connection to the tradition of Johannes Liechtenauer, the grand master of the German school of fencing. Talhoffer was a well educated man, who took interest in astrology, mathematics, onomastics, and the auctoritas and the ratio. He authored at least five fencing manuals during the course of his career, and appears to have made his living teaching, including training people for martial dueling and trial by combat.

The first historical reference to Talhoffer is in 1433, when he represented Johann Ⅱ von Reisberg, archbishop of Salzburg, before the Vehmic court. Shortly thereafter in 1434, Talhoffer was arrested and questioned by order of Wilhelm von Villenbach (a footman to Albrecht Ⅲ von Wittelsbach, duke of Bavaria) in connection to the trial of a Nuremberg aristocrat named Jacob Auer, accused of murdering of his brother Hans. Talhoffer subsequently confessed to being hired to abduct Hans von Villenbach, and offered testimony that others hired by Auer performed the murder.[1] Auer's trial was quite controversial and proved a major source of contention and regional strife for the subsequent two years. Talhoffer himself remained in the service of the archbishop for at least a few more years, and in 1437 is mentioned as serving as a bursary officer (Kastner) in Hohenburg.[2]

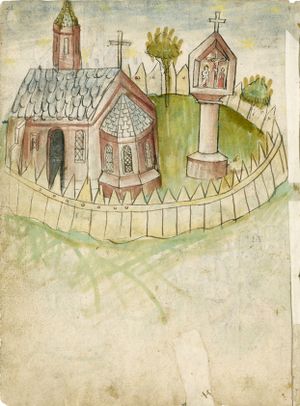

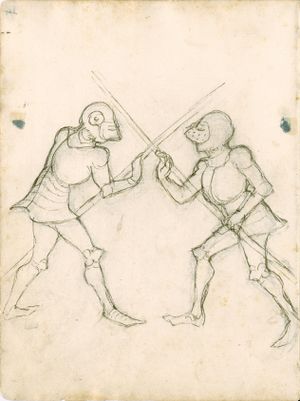

The 1440s saw the launch of Talhoffer's career as a professional fencing master. He purchased (and perhaps contributed to) the MS Chart.A.558, an anthology created in ca. 1448. The fencing portion is largely text-less and it may have been designed as a visual aid for use in teaching; in addition to these illustrations, the manuscript also contains a treatise on name magic and a warbook that might be related to Konrad Kyeser's Bellifortis. While Talhoffer's owner's mark appears in this manuscript,[3] his level of involvement with its creation is unclear. It contains many works by other authors, in addition to plays that are somewhat similar to his later works, and shows evidence of multiple scribes and multiple artists. It is possible that he purchased the manuscript after it was completed (or partially completed), and used it as a basis for his later teachings.[4]

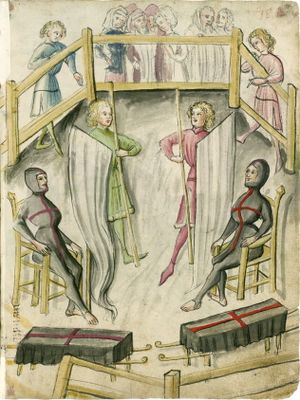

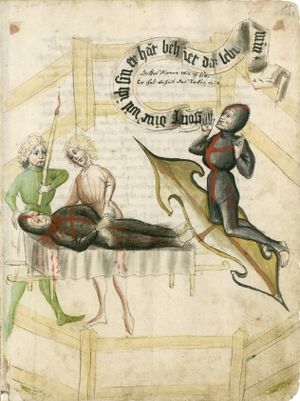

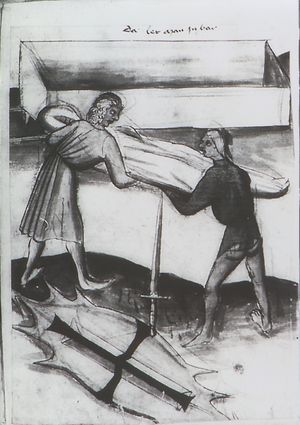

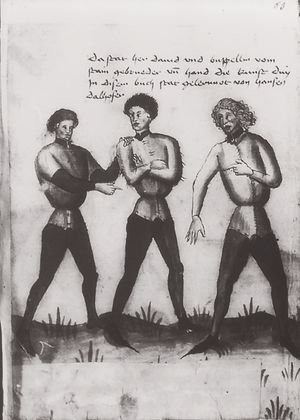

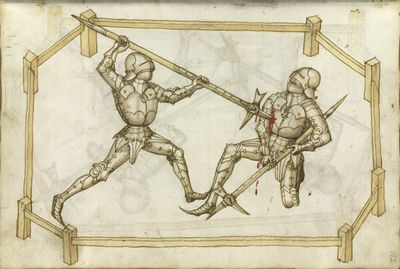

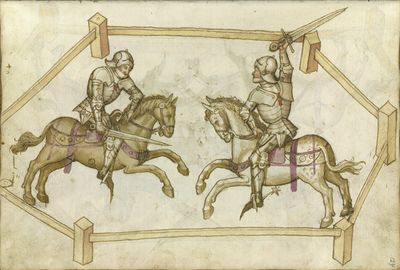

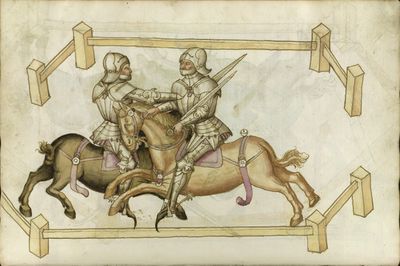

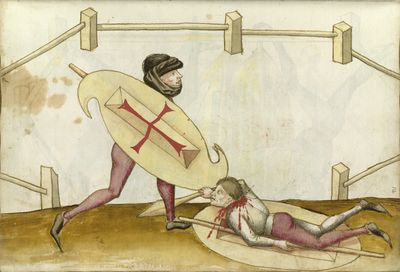

Most notable among the noble clients that Talhoffer served in this period was the Königsegg family of southern Germany, and some time between 1446 and 1459[5] he produced the MS ⅩⅨ.17-3 for this family. This work depicts a judicial duel being fought by Luithold von Königsegg and the training that Talhoffer gave him in preparation, but it seems that this duel never actually took place.[6] He seems to have passed through Emerkingen later in the 1450s, where he was contracted to train the brothers David and Buppellin vom Stain; he also produced the MS 78.A.15 for them, a significantly expanded version of the Königsegg manuscript.[7]

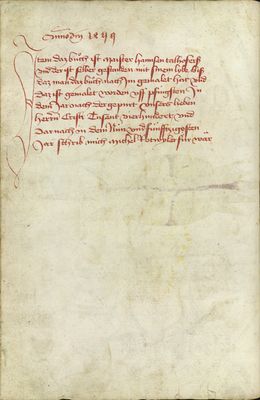

In 1459,[8] Talhoffer commissioned the MS Thott.290.2º, a new personal fencing manual along the same lines as the 1448 work but expanded with additional content and captioned throughout. He appears to have continued instructing throughout the 1460s, and in 1467 he produced his final manuscript, Cod.icon 394a, for another of his noble clients, Eberhardt Ⅴ von Württemberg, count of Württemberg-Urach (who later became Eberhardt Ⅰ when the reunified Württemberg was elevated to a duchy in 1495).[9] This would be his most extensive work, and the count paid 10 Guilder as well as quantities of rye and oats for the finished work.[10]

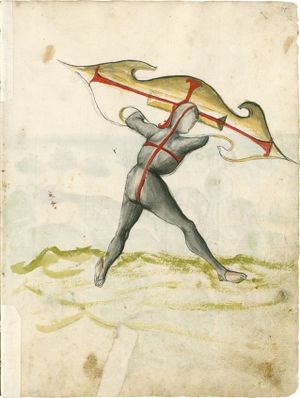

While only a few facts are known about Talhoffer's life, this has not stopped authors from conjecture. The presence of the Lion of St. Mark in Talhoffer's 1459 coat of arms (right) has given rise to speculation that he may have been an early or even founding member of the Frankfurt-am-Main-based Marxbrüder fencing guild, though there is no record of their existence prior to 1474.[citation needed] Additionally, much has been made of the fact that Talhoffer's name doesn't appear in Paulus Kal's list of members of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer.[11] While some have speculated that this indicates rivalry or ill-will between the two contemporaries, it is more likely that Talhoffer simply didn't participate in whatever venture the fellowship was organized for.

Various otherwise-unidentified fencing masters named Hans have also been associated by some authors with Talhoffer. The 1454 records of the city of Zürich note that a master (presumed by some authors to be Hans Talhoffer) was chartered to teach fencing in some capacity and to adjudicate judicial duels; the account further notes that a fight broke out among his students and had to be settled in front of the city council, resulting in various fines.[12] In 1455, a master named Hans was retained by Mahiot Coquel to train him for his duel with Jacotin Plouvier in Valencienne; if this were Talhoffer, his training did little good as Coquel lost the duel and died in brutal fashion.[citation needed]

Contents

- 1 Treatises

- 1.1 First Manuscript (1448)

- 1.2 Königsegg Treatise (1446-59)

- 1.3 Personal Manuscript (1459)

- 1.3.1 Opening

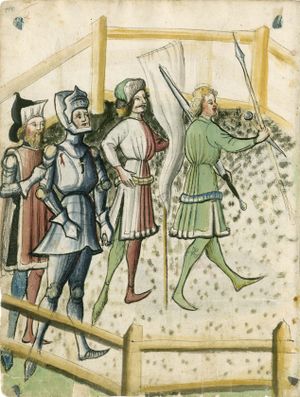

- 1.3.2 Rules for dueling

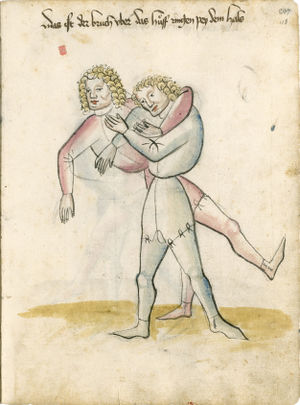

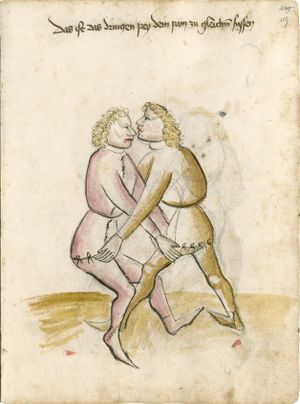

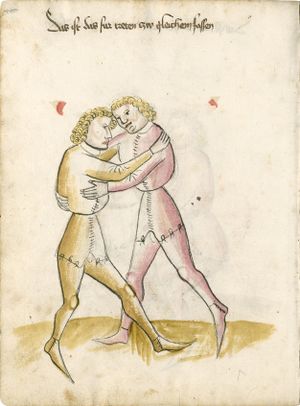

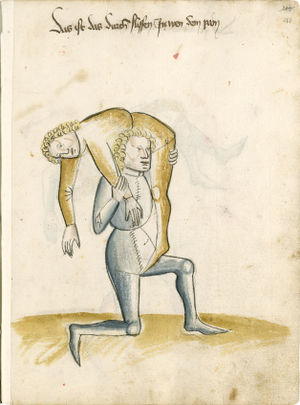

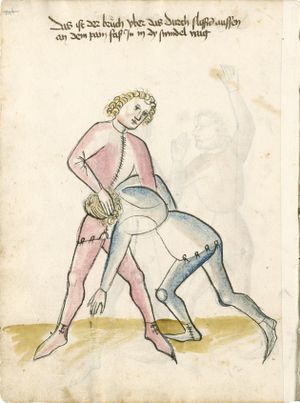

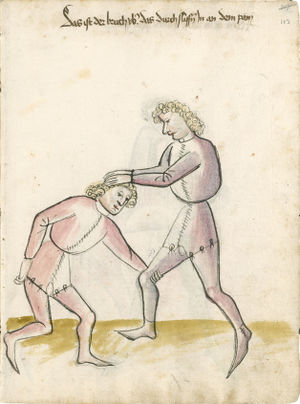

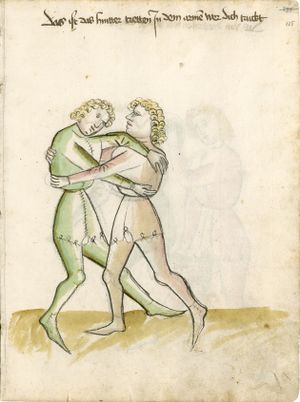

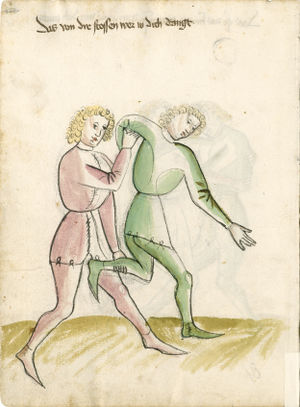

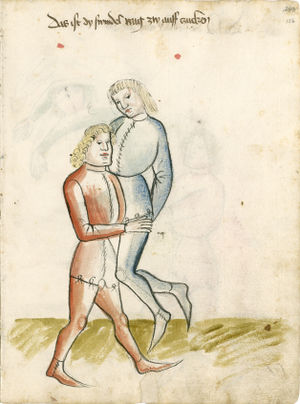

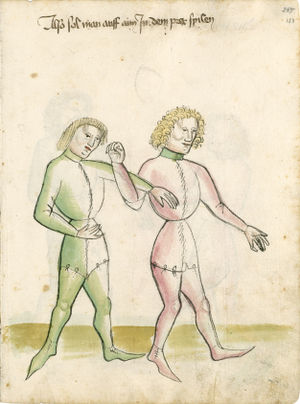

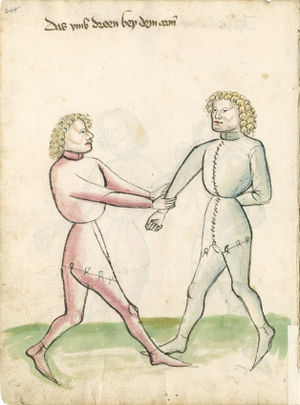

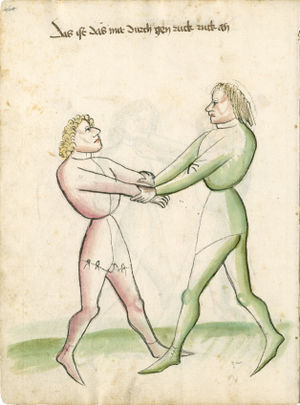

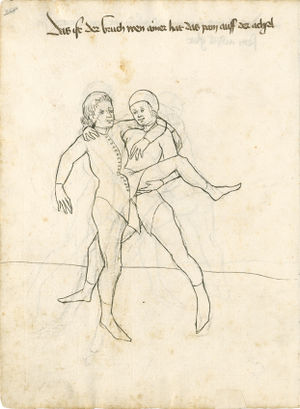

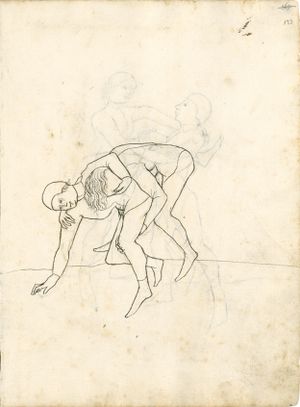

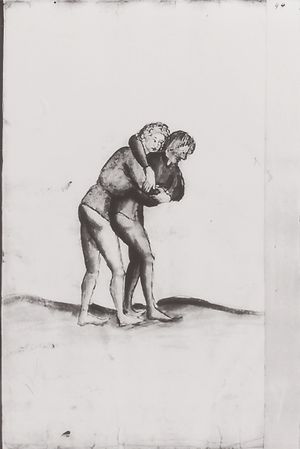

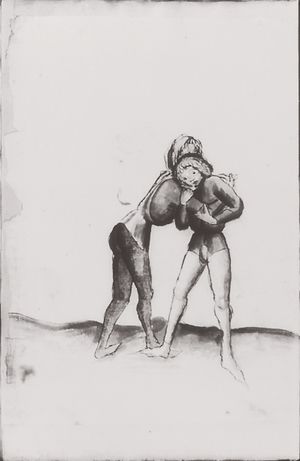

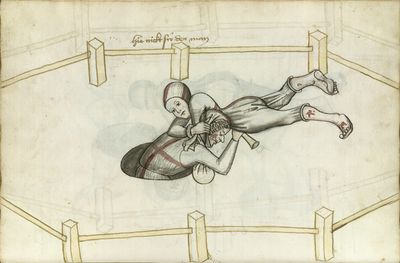

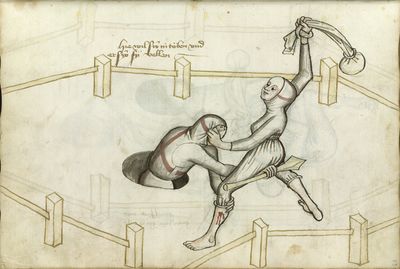

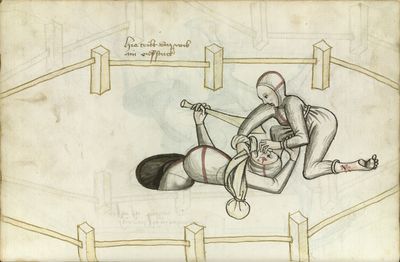

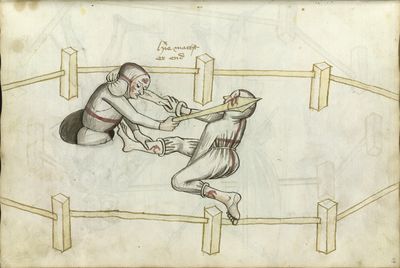

- 1.3.3 Grappling

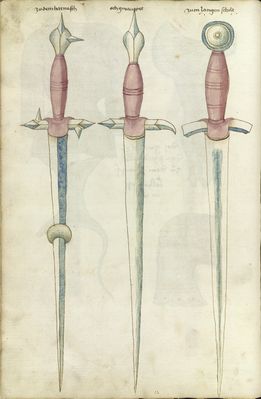

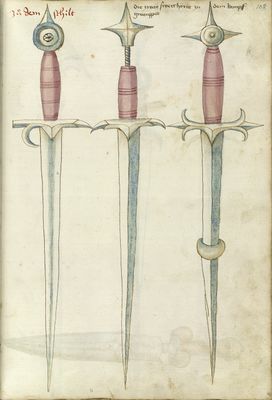

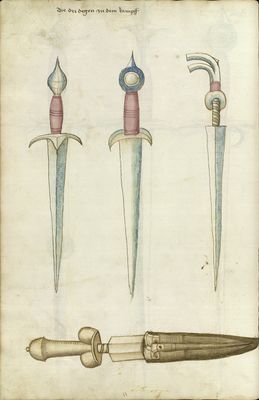

- 1.3.4 Dagger

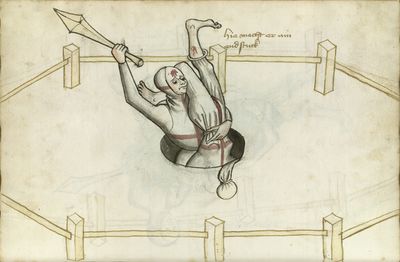

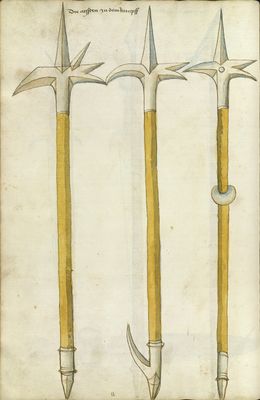

- 1.3.5 Poleaxe

- 1.3.6 Mixed Weapons

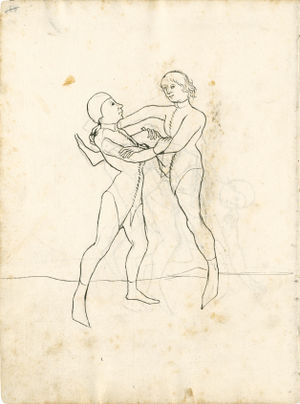

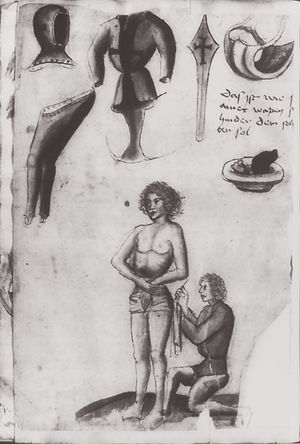

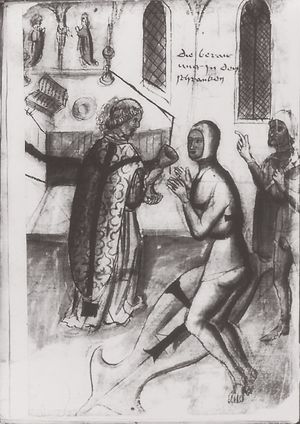

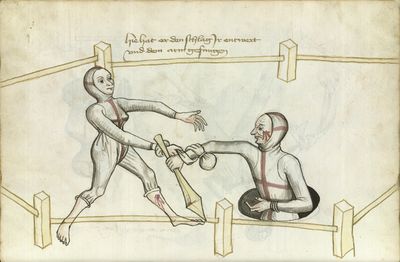

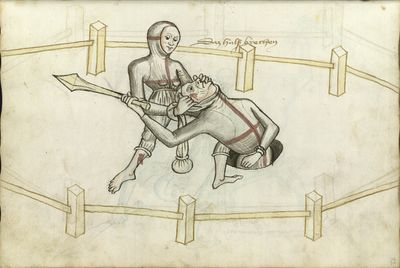

- 1.3.7 Duel between a man and a woman

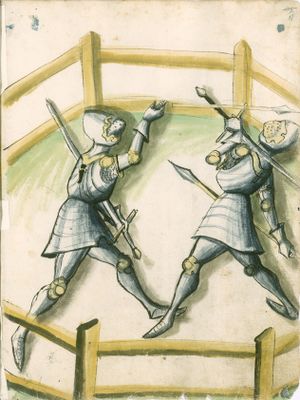

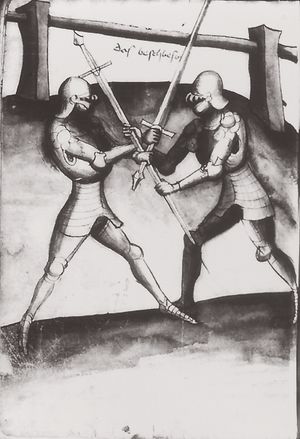

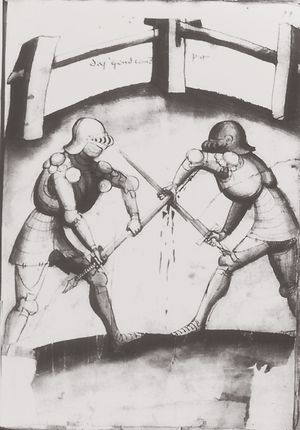

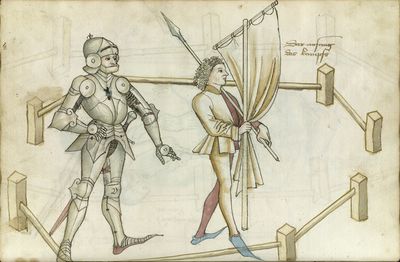

- 1.3.8 Armored fencing

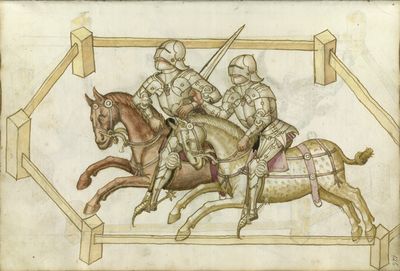

- 1.3.9 Mounted fencing

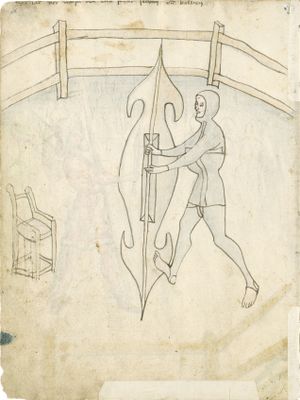

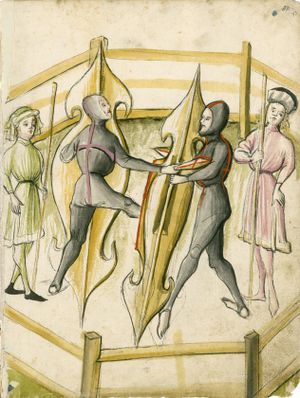

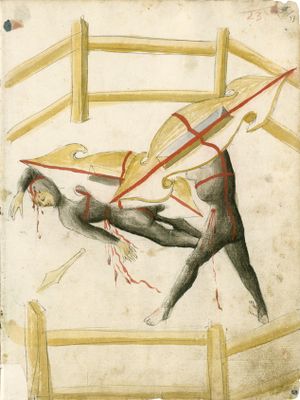

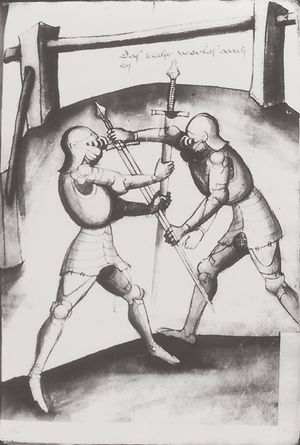

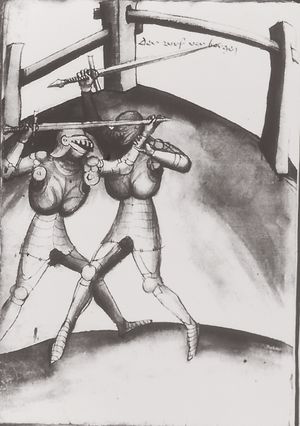

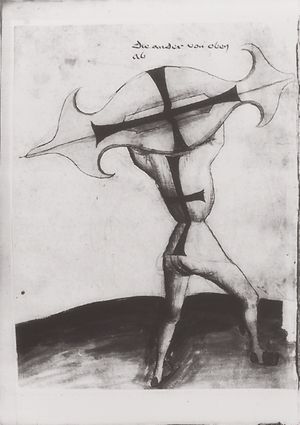

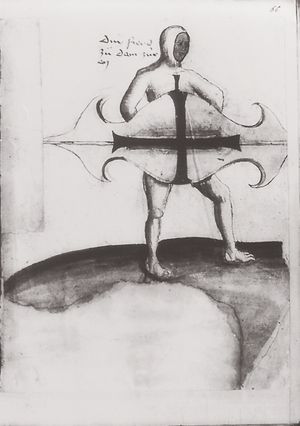

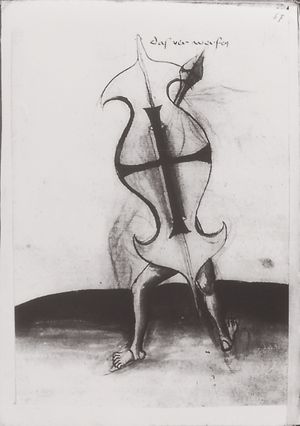

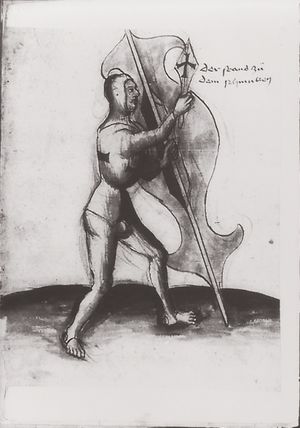

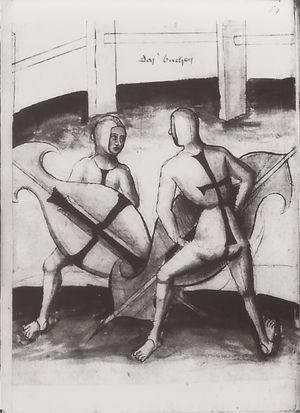

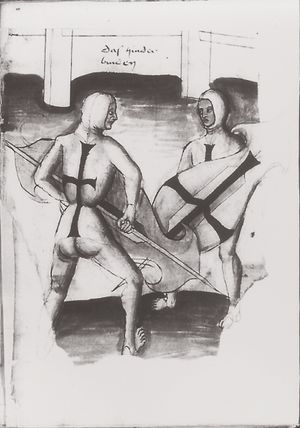

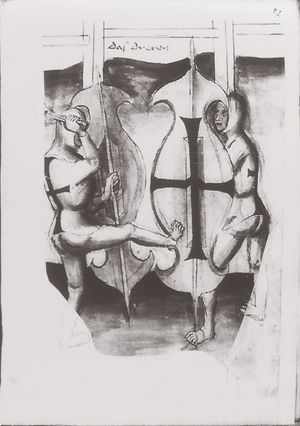

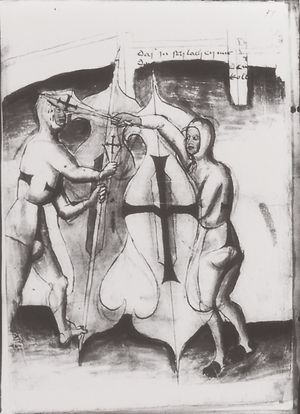

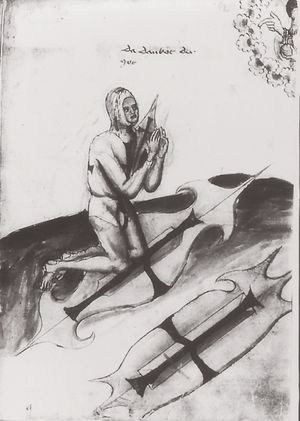

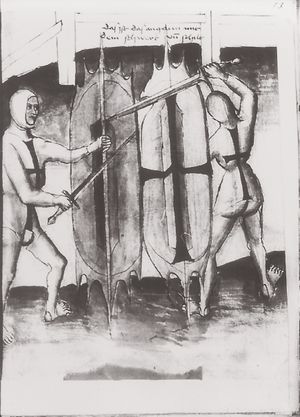

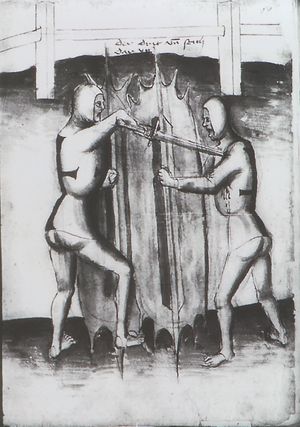

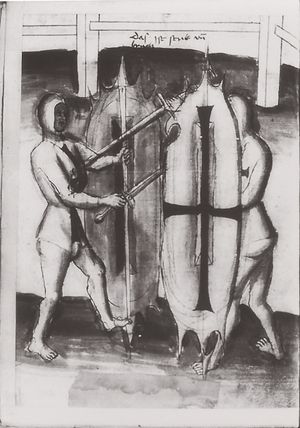

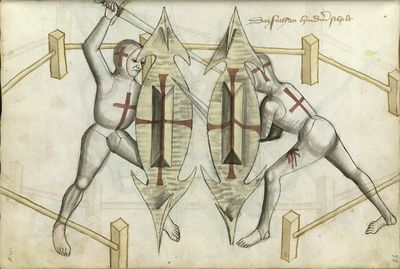

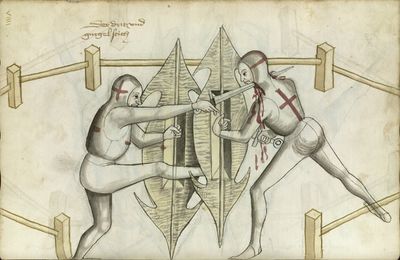

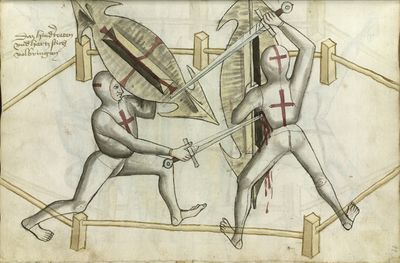

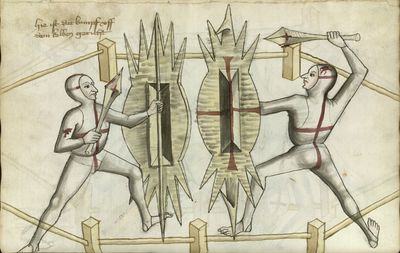

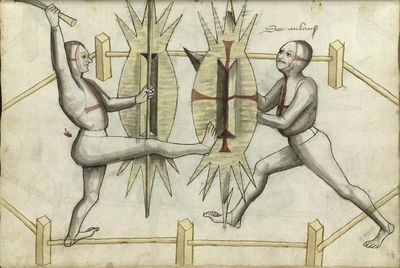

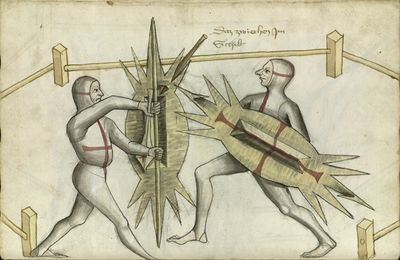

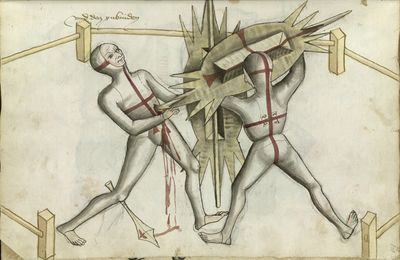

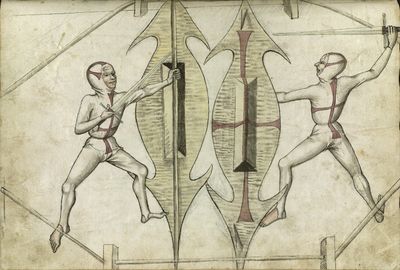

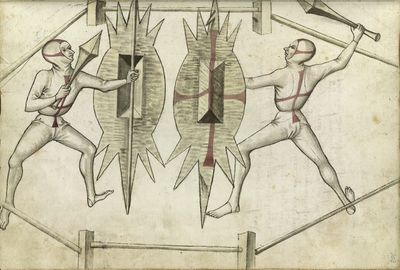

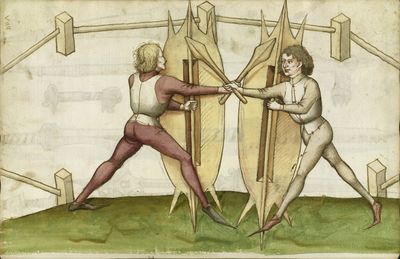

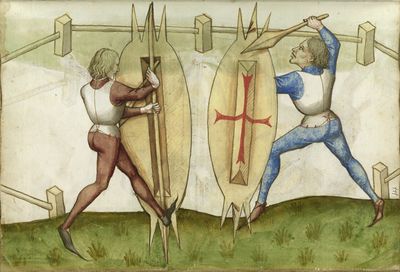

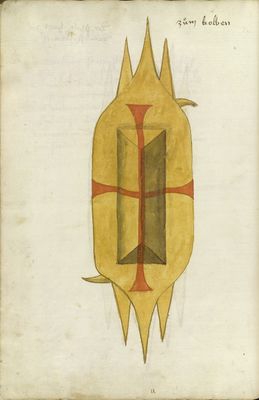

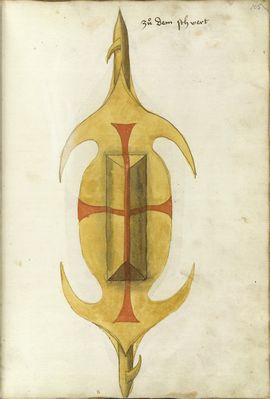

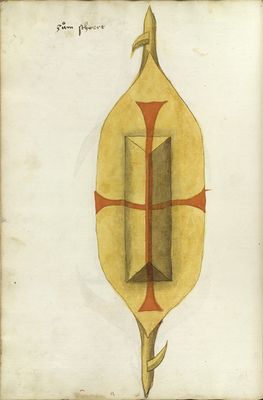

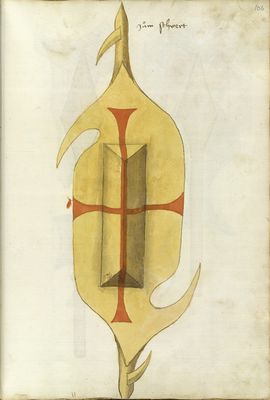

- 1.3.10 Longshield

- 1.3.11 Talhoffer's owner's mark

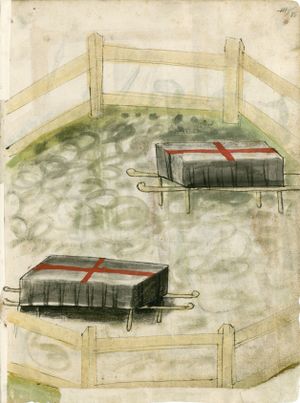

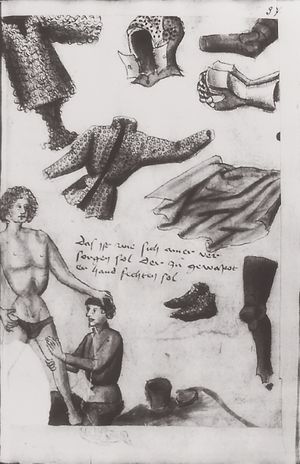

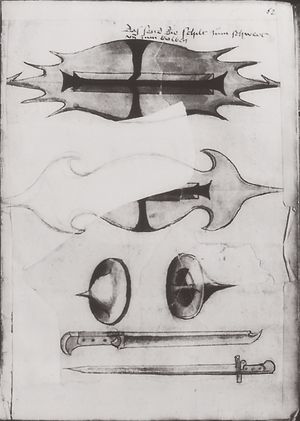

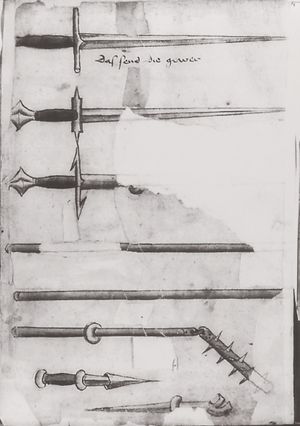

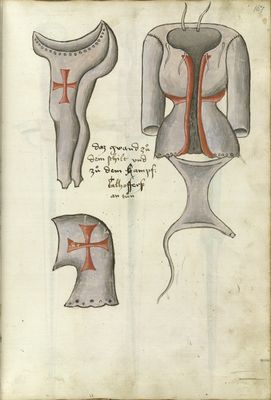

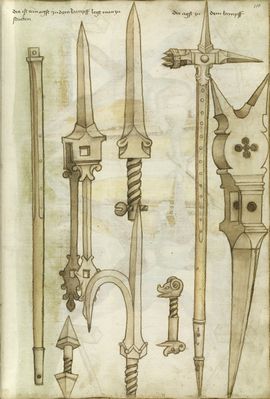

- 1.3.12 Equipment for dueling

- 1.3.13 Sword and buckler

- 1.3.14 Closing

- 1.4 Württemberg Treatise (1467)

- 1.5 Copyright and License Summary

- 2 Additional Resources

- 3 References

Treatises

Not only did Talhoffer produce at least three distinct treatises in his lifetime, but his writings have been reproduced in every century up to the present. They exist in well over a dozen manuscripts created in the fifteenth through nineteenth centuries; they have also been published a number of times in facsimiles beginning in 1887, including translations into English and French.

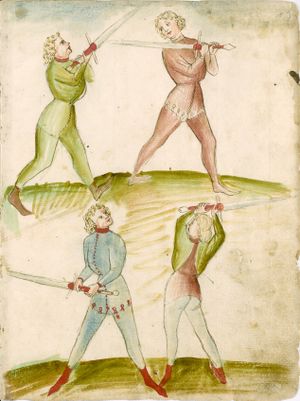

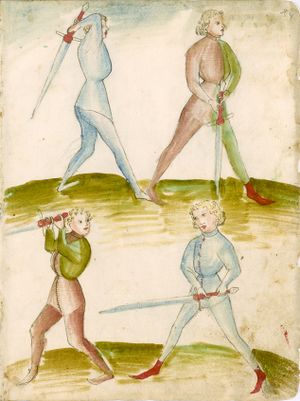

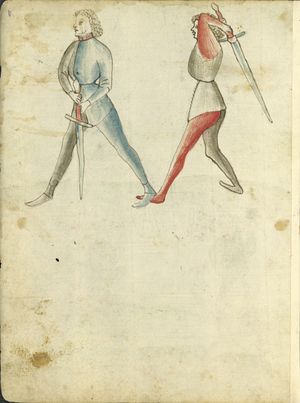

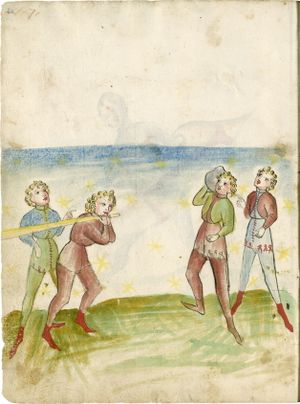

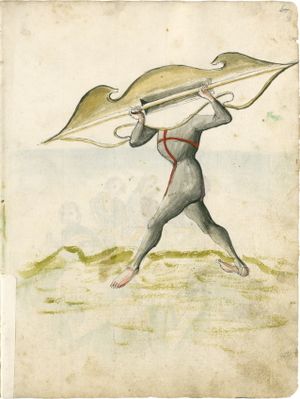

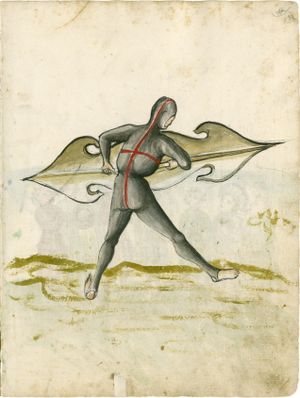

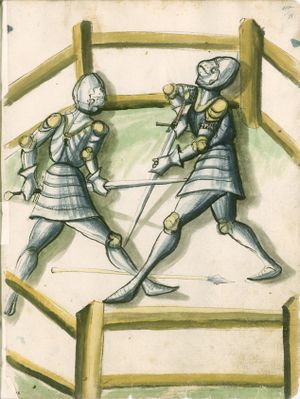

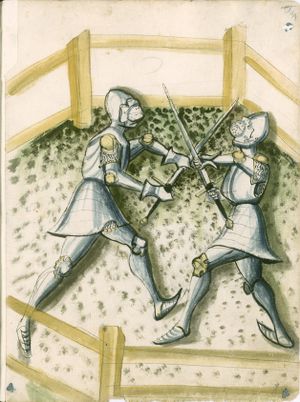

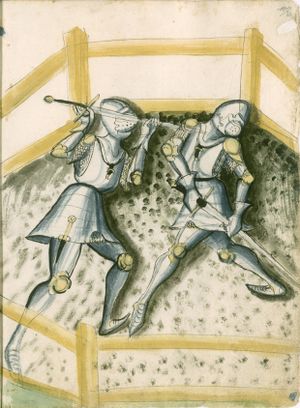

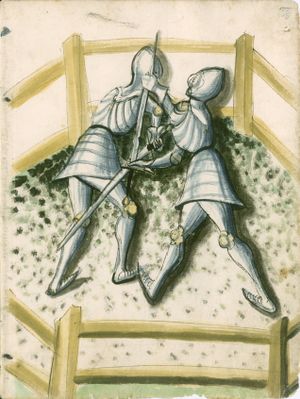

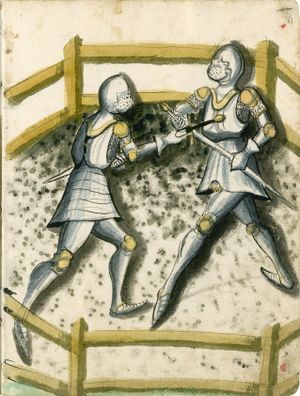

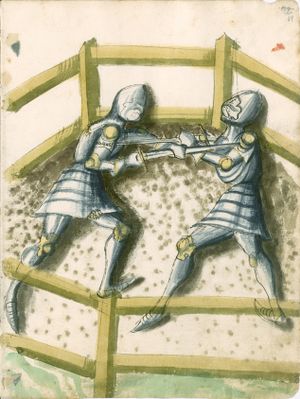

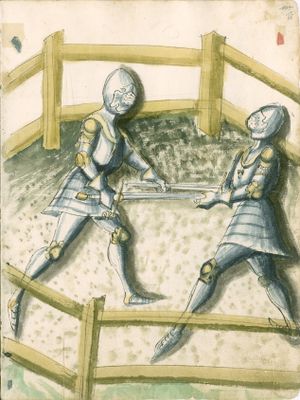

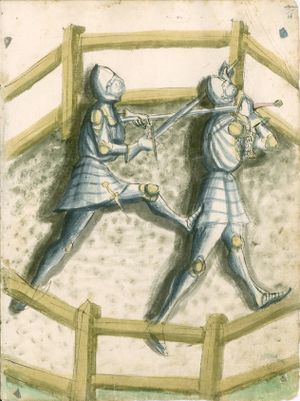

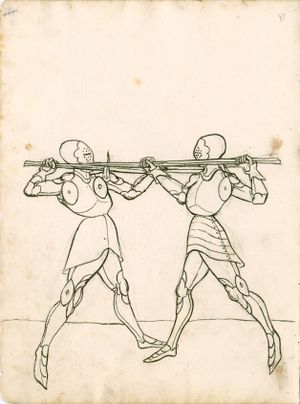

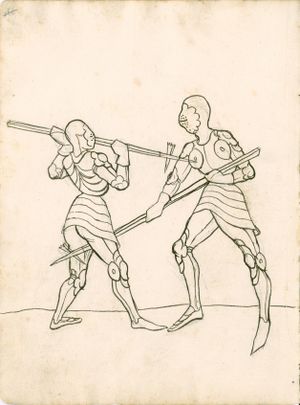

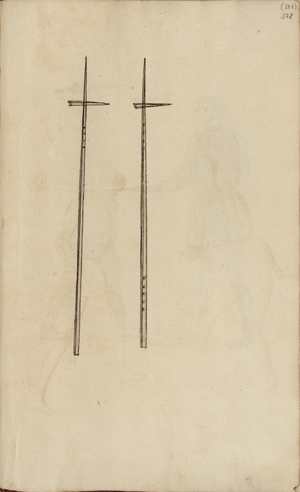

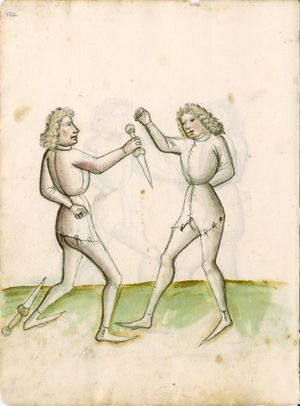

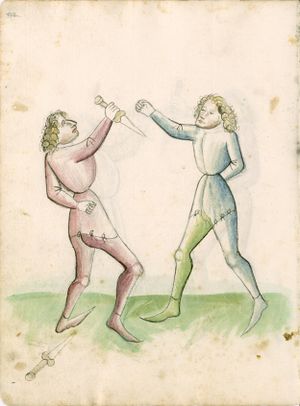

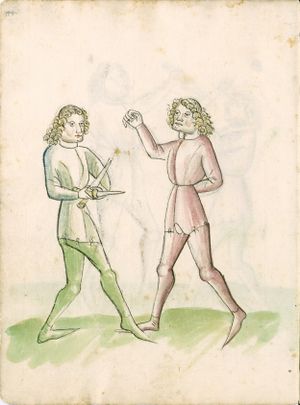

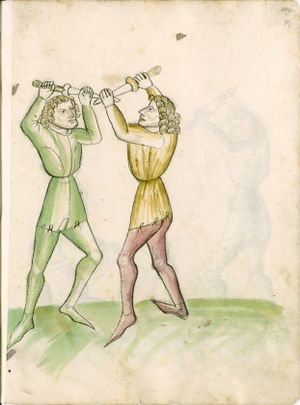

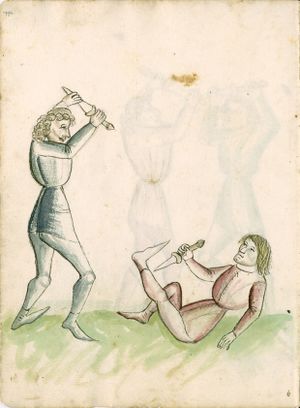

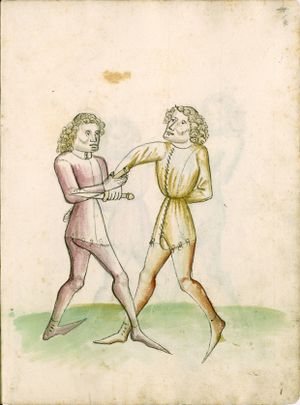

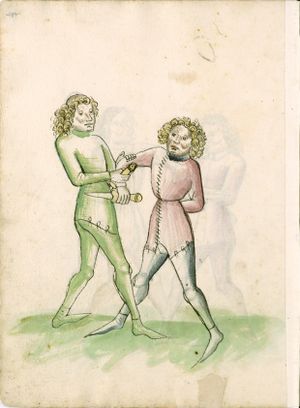

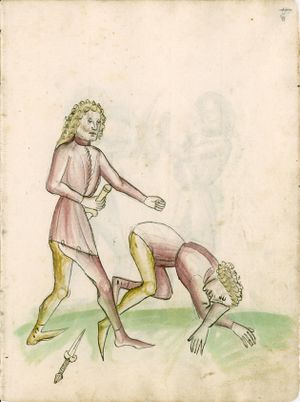

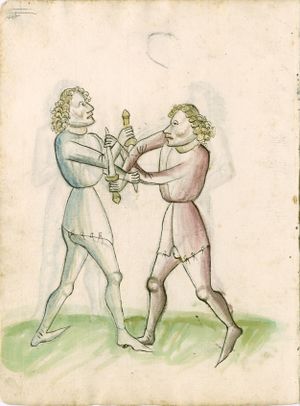

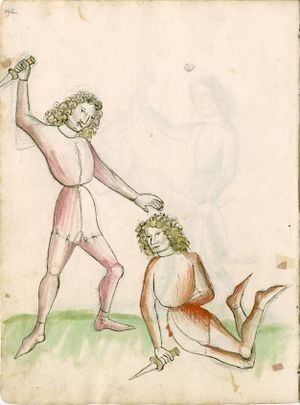

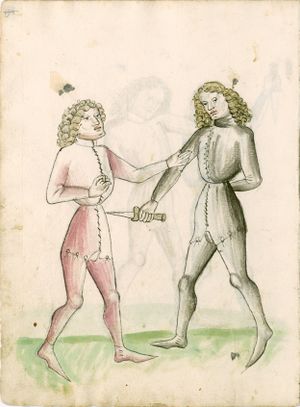

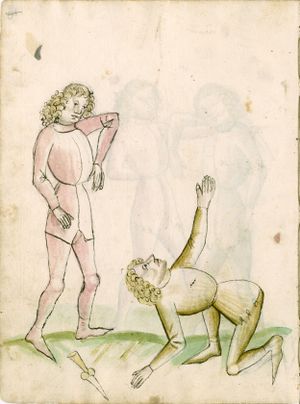

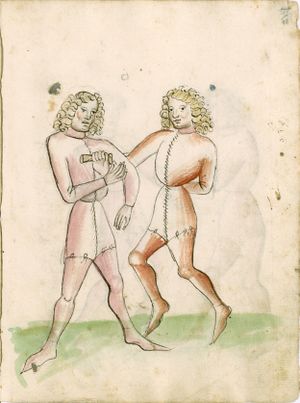

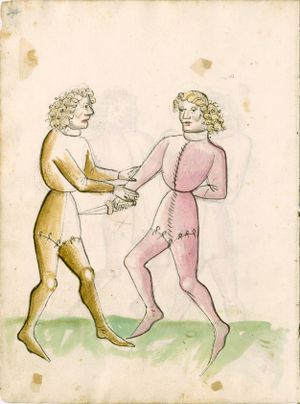

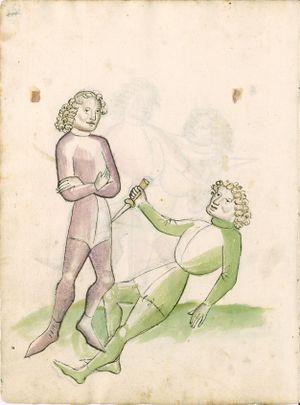

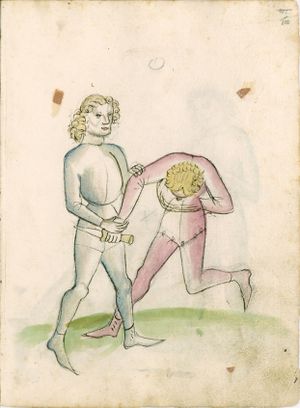

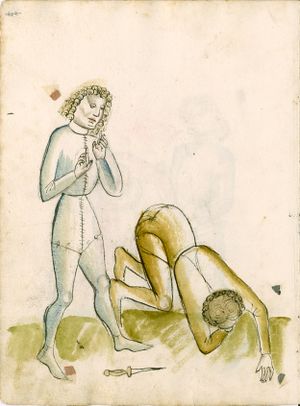

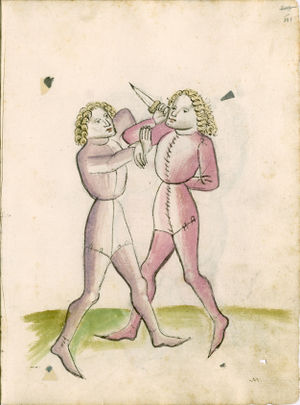

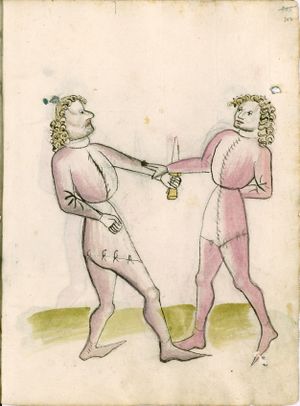

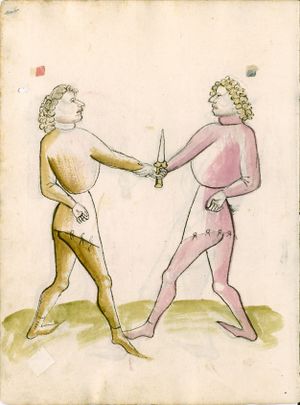

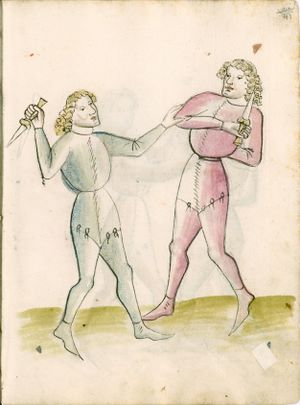

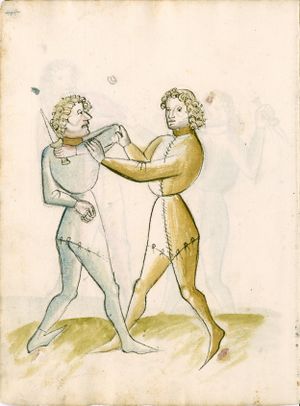

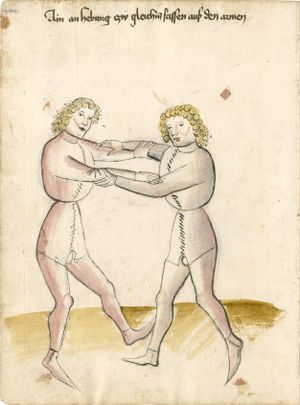

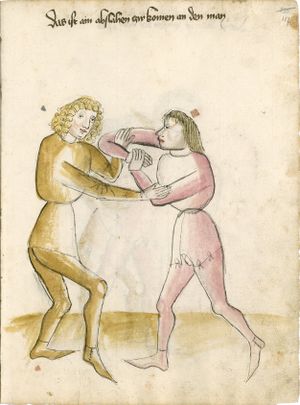

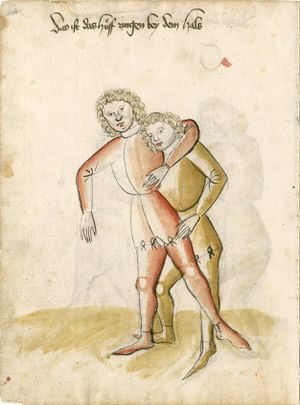

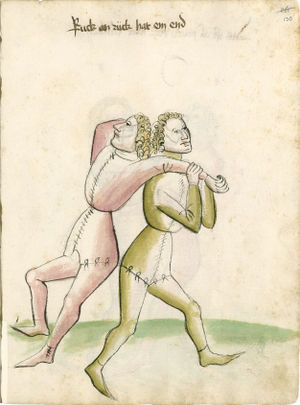

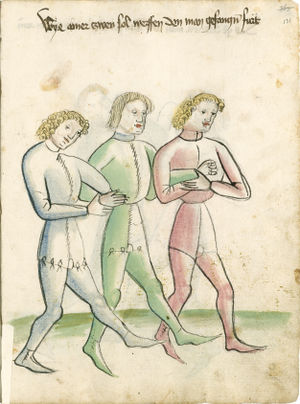

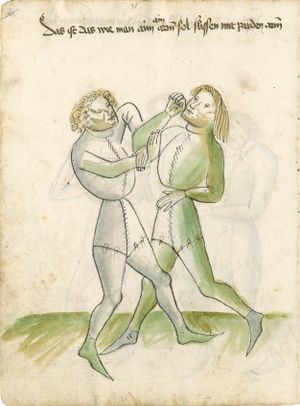

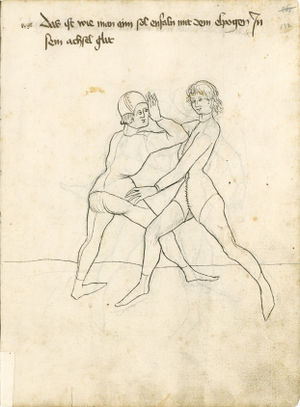

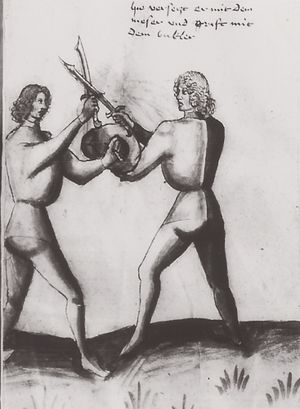

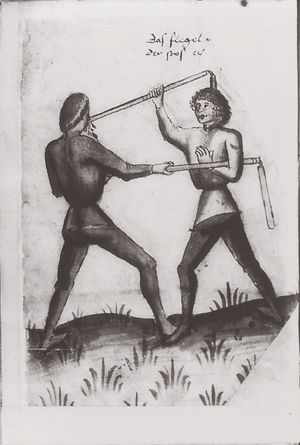

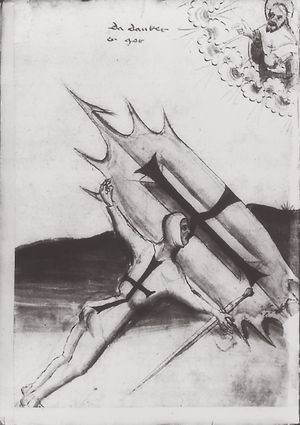

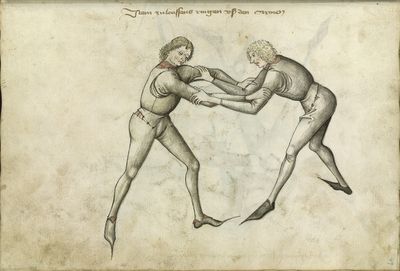

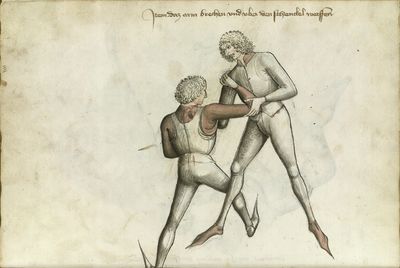

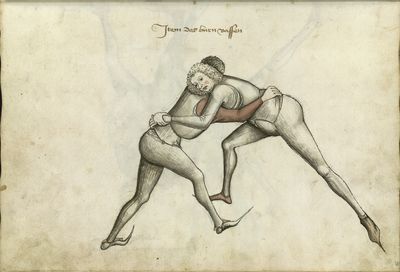

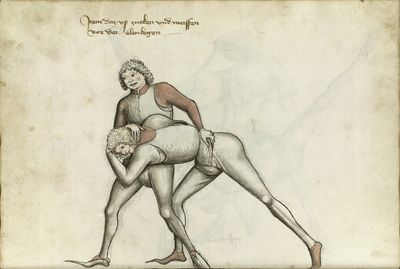

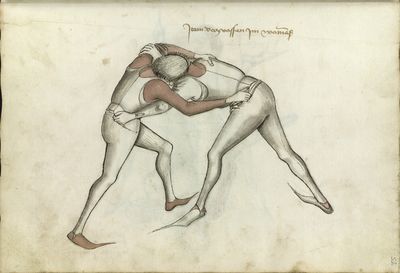

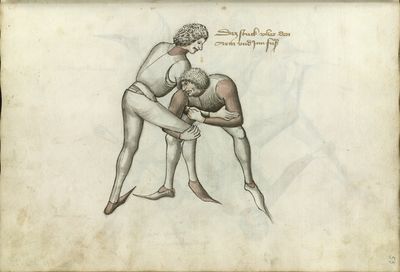

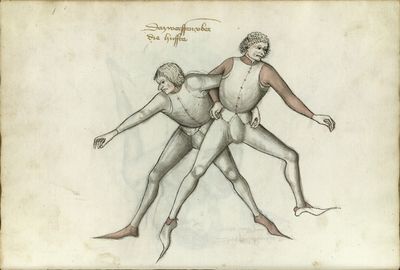

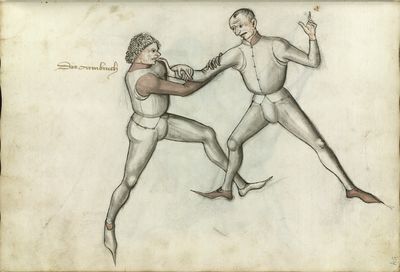

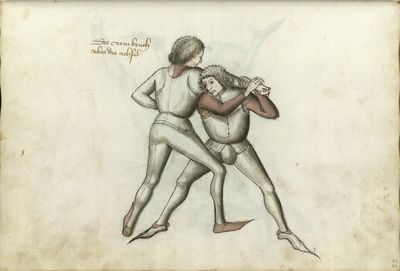

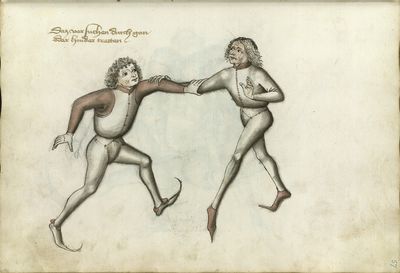

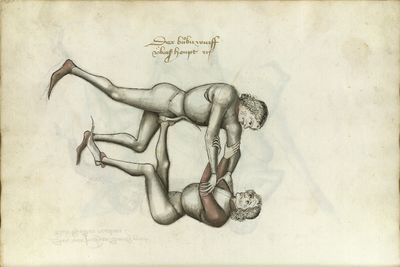

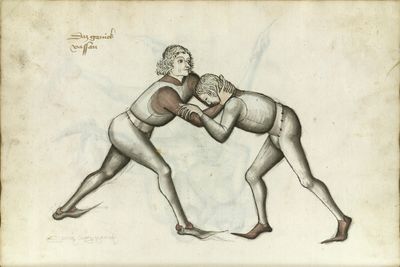

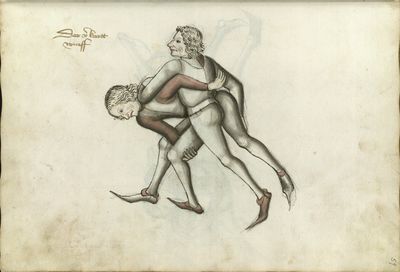

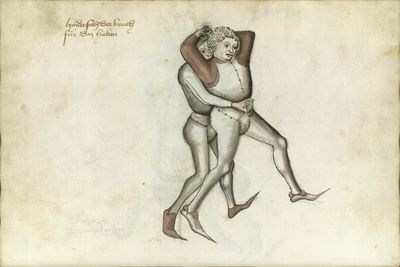

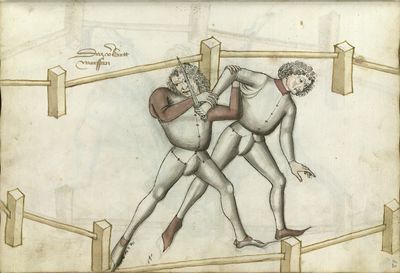

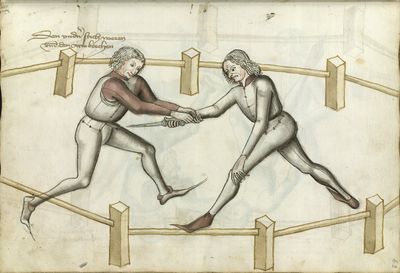

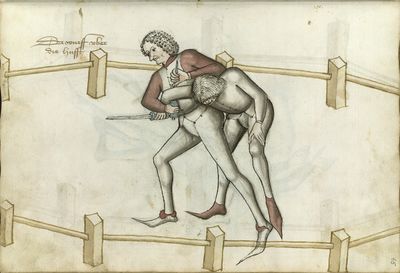

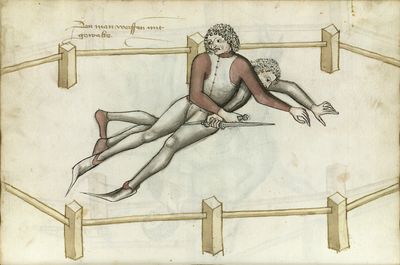

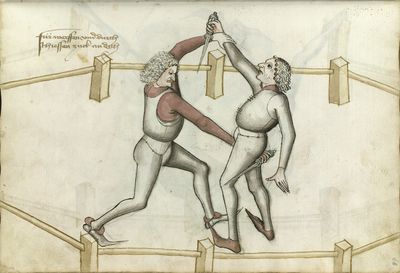

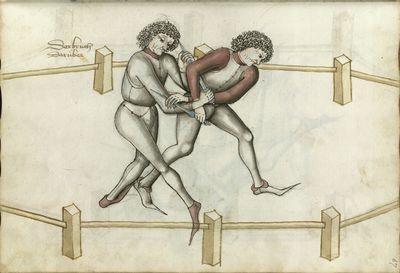

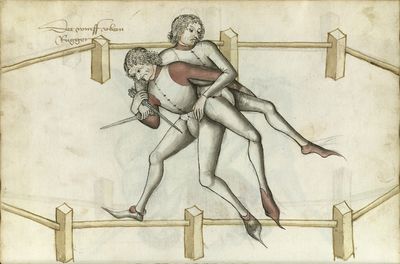

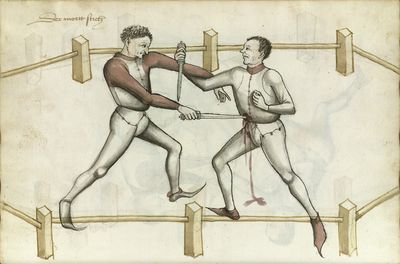

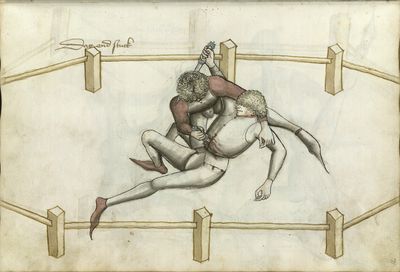

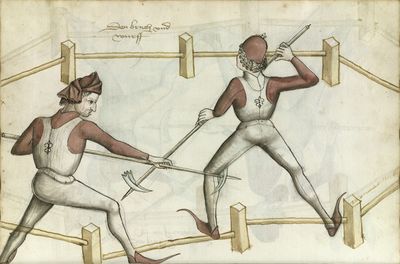

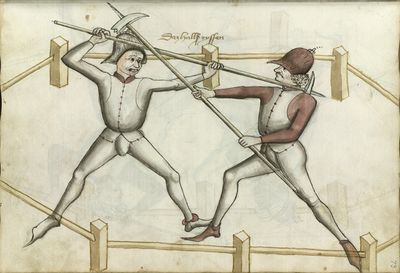

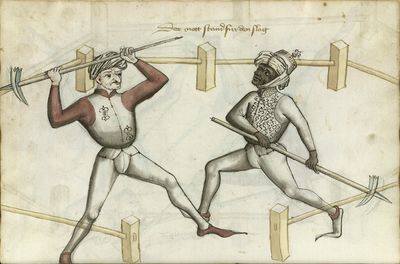

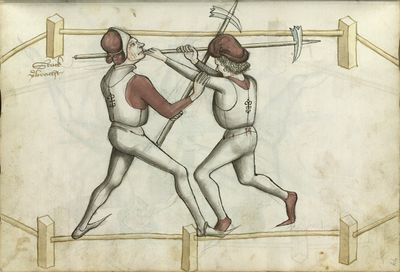

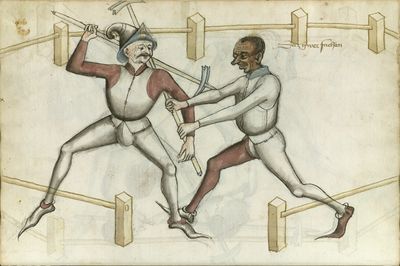

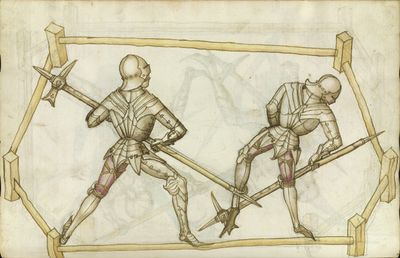

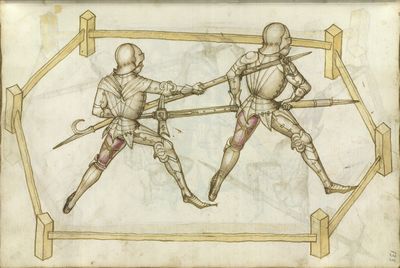

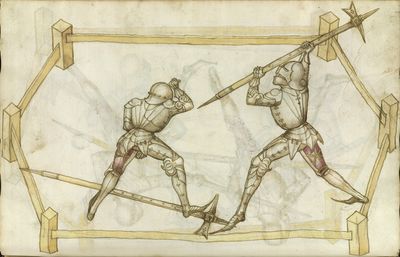

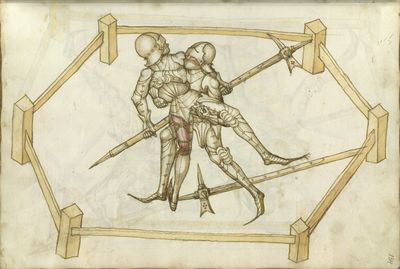

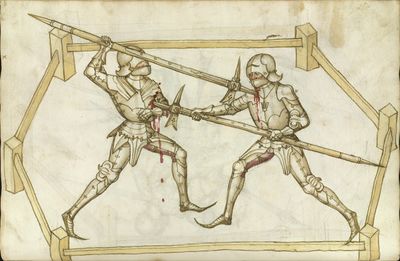

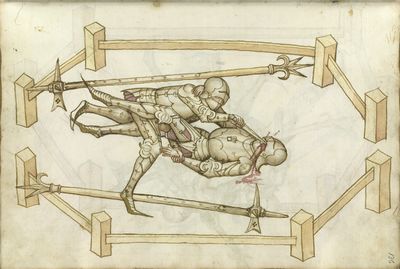

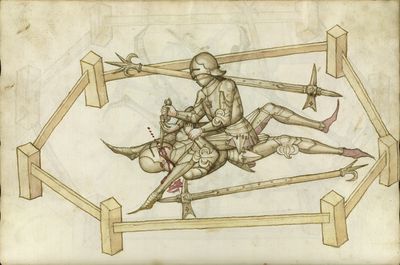

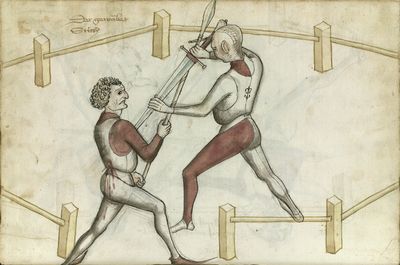

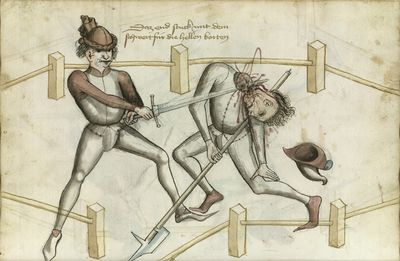

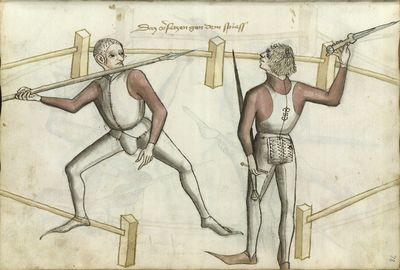

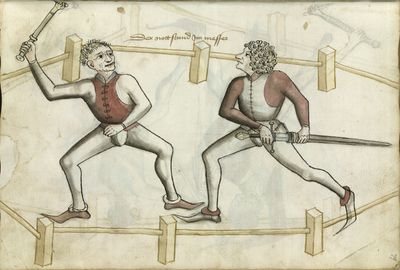

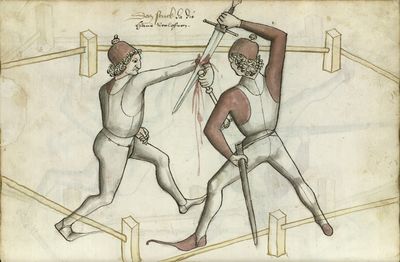

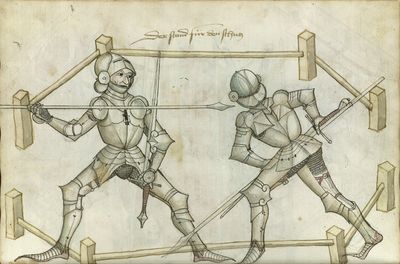

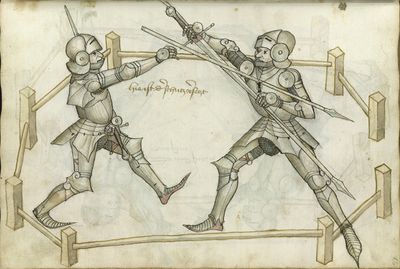

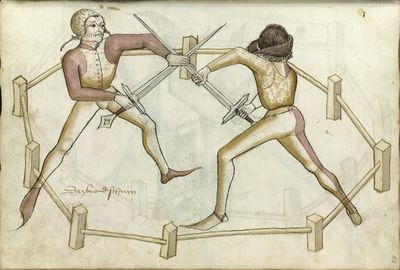

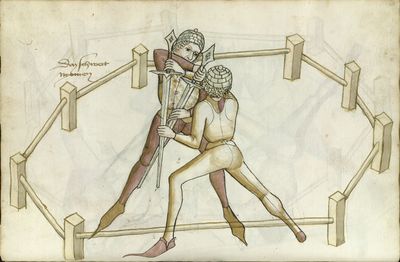

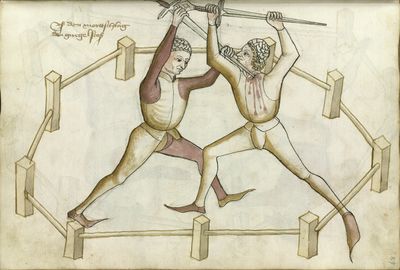

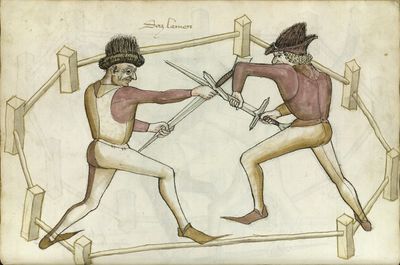

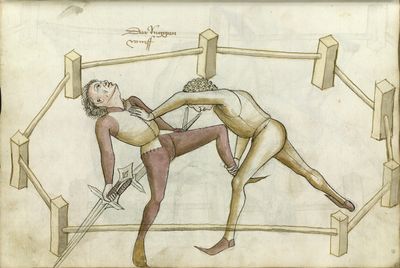

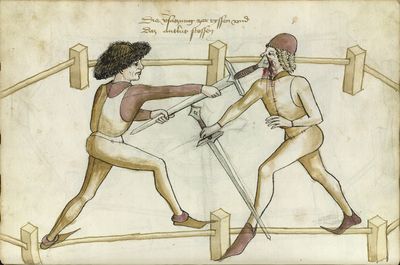

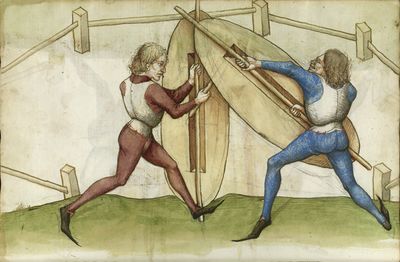

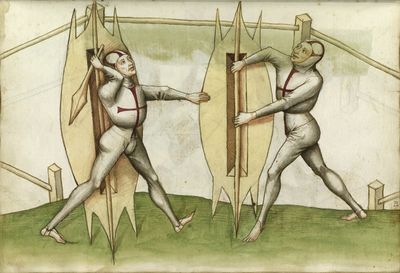

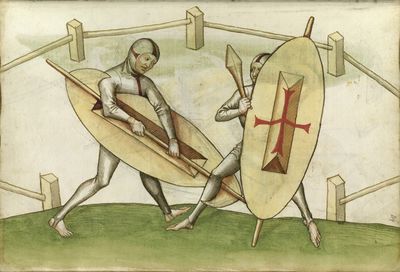

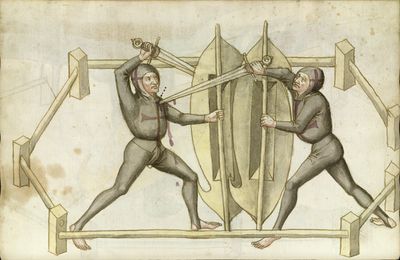

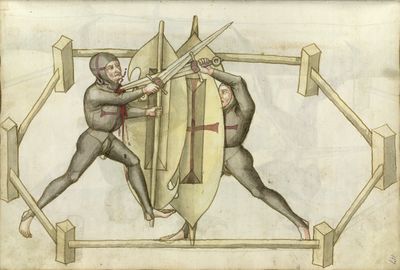

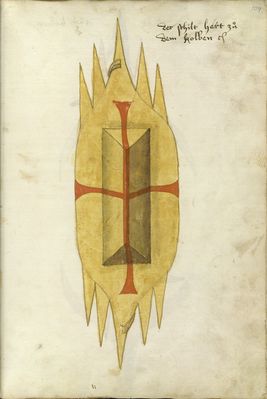

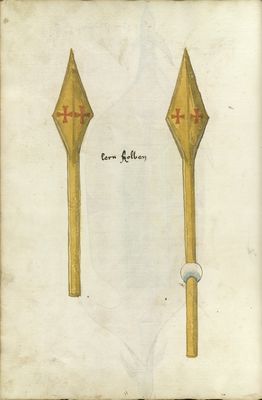

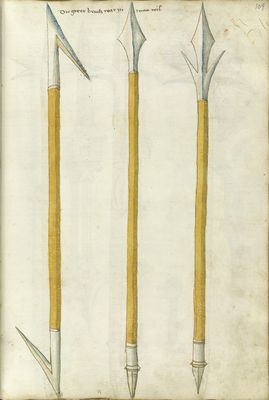

Talhoffer's writings cover a wide assortment of weapons, including the buckler, crossbow, dagger, flail, Messer, longshield, mace, poleaxe, spear, sword, and unarmed grappling, often both armored and unarmored, on horse and on foot, and in scenarios including tournaments, formal duels, and unequal encounters implying urban self-defense. Despite the obvious care and detail that went into the artwork, the manuscripts generally have only a few words captioning each page (and in many cases none at all); some were likely teaching aids and would need no detailed explanation, while the treatises for Königsegg, Stain, and Württemberg were probably intended as memory aids to review his teachings after he left.

Though there is considerable overlap in the specific plays Talhoffer teaches, the organization and exact contents differ in each of the main treatises. For this reason, they are listed separately below (along with their derivative copies) rather than being combined into one giant mixed concordance that fails to capture the organization of any of them. Though his authorship of his first manuscript, the Gotha, cannot be proven, it is included below because it is a useful reference to compare to his authenticated works.

In addition to the four manuscripts which reproduce most or all of the contents of the Gotha version, there are three others that only reproduce single sections.

Wolfenbüttel Ⅰ (1465-80) reproduces only 15 of the 34 illustrated wrestling plays, and also omits their captions. These are not exact copies of the plays in the archetype, but are often depicted mirrored or with minor differences in hand or foot position.

Conversely, the Wolfenbüttel Ⅱ and Coburg versions (which date to the 17th and 18th centuries, respectively) contain the full section on trial by combat with longshields, and they exceed the other versions in that they add captions for many of the illustrations. It's unclear who wrote this text or when it was written, but it's possible that the text is original to the treatise and the archetype for all later versions is just a draft or incomplete copy from another manuscript, now missing. In the absence of more information, it seems prudent to treat the text as authentic.

To streamline the concordance, these additional sources are included at the far-right side of the respective tables and not included in any other sections.

The earlest known copy made from the archetype, which was previously Cod.Ser.Nov.2978, was sold to an unknown private collector in the late 20th century and is no longer available for study. For this reason, it cannot be included in the concordances below. The Göttingen, Wolfenbüttel Ⅱ, and Coburg versions only include plays of the duel between man and woman, so to make the tables easier to read, they are omitted from all other sections and included at the far right side of that one.

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

Additional Resources

The following is a list of publications containing scans, transcriptions, and translations relevant to this article, as well as published peer-reviewed research.

- Der Königsegger Codex. Die Fechthandschrift des Hauses Königsegg (2010). Ed. by André Schulze; Johannes Graf zu Königsegg-Aulendorf. Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-3753-3.

- Alte Armature und Ringkunst: The Royal Danish Library Ms. Thott 290 2º (2020). Trans. by Rebecca L. R. Garber. Ed. by Michael Chidester; Dieter Bachmann. Somerville: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-04-5.

- Acutt, Jay (2019). Swords, Science, and Society: German Martial Arts in the Middle Ages. Glasgow: Fallen Rook Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9934216-9-3.

- Becker, Paul (2020). "Hans Talhoffer: Insights into the Life of a Fencing Master in the 15th Century." Alte Armature und Ringkunst: The Royal Danish Library Ms. Thott 290 2º: 47-68. Ed. by Michael Chidester. Somerville: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-04-5.

- Burkart, Eric (2014). "Die Aufzeichnung des Nicht-Sagbaren. Annäherung an die kommunikative Funktion der Bilder in den Fechtbüchern des Hans Talhofer." Das Mittelalter 19(2): 253-301. Ed. by Christian Jaser; Uwe Israel. doi:10.1515/mial-2014-0017.

- Burkart, Eric (2018). "Body Techniques of Combat: The Depiction of a Personal Fighting System in the Fight Books of Hans Talhofer (1443-1467 CE)." Killing and Being Killed: Bodies in Battle: 109-130. Bielefeld: Transcript-Verlag. doi:10.14361/9783839437834-008.

- Clarke, Stuart (2010). Medieval Fight Book [Television]. Wild Dream Films.

- Deacon, Jacob Henry (2016). "Prologues, Poetry, Prose and Portrayals: The Purposes of Fifteenth Century Fight Books According to the Diplomatic Evidence." Acta Periodica Duellatorum 4(2): 69-90. doi:10.36950/apd-2016-014.

- Elema, Ariella (2012). Trial by Battle in France and England [Unpublished dissertation]. University of Toronto. https://hdl.handle.net/1807/67806

- Elema, Ariella (2019). "Tradition, Innovation, Re-enactment: Hans Talhoffer's Unusual Weapons." Acta Periodica Duellatorum 7(1): 3-25. doi:10.2478/apd-2019-0001.

- Hagedorn, Dierk (2016). "German Fechtbücher from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance." Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe: 247-279. Ed. by Daniel Jaquet; Karin Verelst; Timothy Dawson. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31241-8.

- Hagedorn, Dierk (2020). "Talhoffer Galore." Alte Armature und Ringkunst: The Royal Danish Library Ms. Thott 290 2º: 69-88. Ed. by Michael Chidester. Somerville: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-04-5.

- Hergsell, Gustav; Hans Talhoffer (1887). Talhoffers Fechtbuch (Ambraser Codex) aus dem Jahre 1459. Prague: J.G. Calve.

- Hergsell, Gustav; Hans Talhoffer (1887). Talhoffers Fechtbuch aus dem jahre 1467: Gerichtliche und andere zweikämpfe darstellend. Prague: J.G. Calve.

- Hergsell, Gustav; Hans Talhoffer (1889). Talhoffers Fechtbuch (Gothaer Codex) aus dem Jahre 1443. Prague: J.G. Calve.

- Hergsell, Gustav; Hans Talhoffer (1890, 1901). Livre d'escrime de Talhoffer (manuscrit d'Ambras), de l'an 1459. Prague: Chez L'Auteur.

- Hergsell, Gustav; Hans Talhoffer (1893, 1901). Livre d'escrime de Talhoffer (codex Gotha) de l'an 1443. Prague: Chez L'Auteur.

- Hergsell, Gustav; Hans Talhoffer (1894, 1901). Livre d'escrime de Talhoffer de l'an 1467. Prague: Chez L'Auteur.

- Hermann, Hans-Georg (2017). "Die prozessuale Konfiguration des spätmittelalterlichen Zweikampfes als Deutungskontext von Fechtbüchern." Die Kunst des Fechtens: 23-76. Ed. by Matthias Johannes Bauer; Elisabeth Vavra. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8253-6699-5.

- Hils, Hans-Peter (1983). "Die Handschriften des oberdeutschen Fechtmeisters Hans Talhoffer: ein Beitrag zur Fachprosaforschung des Mittelalters." Codices manuscripti & impressi 8: 97-121.

- Hull, Jeffrey; Grzegorz Żabiński; Monika Maziarz (2007). Knightly Dueling: The Fighting Arts of German Chivalry. Boulder: Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1-581606744.

- Israel, Uwe (2017). "Die Fechtbücher Hans Talhofers und die Praxis des gerichtlichen." Die Kunst des Fechtens: 93-132. Ed. by Matthias Johannes Bauer; Elisabeth Vavra. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8253-6699-5.

- Jaquet, Daniel (2017). "Les Arts Magiques et les Arts du Combat: Étude du Recueil de 1448 Attribué à Hans Talhoffer." De Frédéric à Rodolphe II: Astrologie, divination et magie dans les cours (XIIIe–XVIIe siècle): 271–294. Ed. by Jean-Patrice Boudet; Martine Ostorero; Agostino Paravicini Bagliani. Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo. ISBN 978-88-8450-808-9.

- Jaquet, Daniel (2018). "Six Weeks to Prepare for Combat: Instruction and Practices from the Fight Books at the End of the Middle Ages, a Note on Ritualised Single Combats: Perspectives on Fighters in the Middle Ages." Killing and Being Killed: Bodies in Battle: 131-164. Bielefeld: Transcript-Verlag. doi:10.14361/9783839437834-009.

- Kirchhoff, Chassica (2018). "Visualizing the Fight Book Tradition: Collected Martial Knowledge in the Thun-Hohenstein Album." Acta Periodica Duellatorum 6(1): 3-45. doi:10.2478/apd-2018-0001.

- Knight, Hugh T., Jr (2009). The Ambraser Codex by Master Hans Talhoffer. Self-published. ISBN 978-0-557-38531-7.

- Muhlberger, Steven (2005). Deeds of Arms. Highland Village: Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-44-7.

- Muhlberger, Steven; Will McLean (2019). Murder, Rape, and Treason: Judicial Combats in the Late Middle Ages. Wheaton: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-1-937439-41-5.

- Müller, Jan-Dirk (1992). "Bild – Verse – Prosakommentar am Beispiel von Fechtbüchern. Probleme der Verschriftlichung einer schriftlosen Praxis." Pragmatische Schriftlichkeit im Mittelalter. Erscheinungsformen und Entwicklungsstufen: 251-282. Ed. by Hagen Keller; Klaus Grubmüller; Nikolaus Staubach. München: Fink.

- Stangier, Thomas (2009). "'Ich hab ein hertz als ein leb…'. Zweikampfrealität und Tugendideal in den Fechtbüchern Hans Talhoffers und Paul Kals." Ritterwelten im Spätmittelalter. Höfisch-ritterliche Kultur der Reichen Herzöge von Bayern-Landshut: 73-93. Landshut: Museen der Stadt Landshut.

- Sørensen, Claus F. (2015). "Et senmiddelalderligt tysk fægtemesterhånd-skrift på Det Kongelige Bibliotek. Ms. Thott 290 2º." Fund og Forskning i Det Kongelige Biblioteks Samlinger 50: 159-189. doi:10.7146/fof.v50i0.41246.

- Talhoffer, Hans (2000). Medieval Combat: A Fifteenth-Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat. Trans. by Mark Rector. Barnsley: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1853674181.

- Talhoffer, Hans (2018). Medieval Combat in Colour: Hans Talhoffer's Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat from 1467. Ed. by Dierk Hagedorn. Barnsley: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-78438-285-8.

- Tobler, Christian Henry (2020). "Addenda and Esoterica in the Thott Talhoffer Codex." Alte Armature und Ringkunst: The Royal Danish Library Ms. Thott 290 2º: 179-186. Ed. by Michael Chidester. Somerville: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-04-5.

- Tobler, Christian Henry (2022). Lance, Spear, Sword, & Messer: A German Medieval Martial Arts Miscellany. Wheaton: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-1-937439-64-4.

- Verelst, Karin (2023). "Medicine, Logic, or Metaphysics? Aristotelianism and Scholasticism in the Fight Book Corpus." Acta Periodica Duellatorum 11(1): 91-127. doi:10.36950/apd-2023-006.

- Welle, Rainer (1993). '…und wisse das alle höbischeit kompt von deme ringen'. Der Ringkampf als adelige Kunst im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert. Pfaffenweiler: Centaurus-Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 3-89085-755-8.

References

- ↑ Jens P. Kleinau. "1434 March 20th – Talhoffer’s confession in Salzburg". Hans Talhoffer ~ A Historical Martial Arts blog by Jens P. Kleinau, 18 May 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Jens P. Kleinau. "Hans Talhoffer’s life". Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ↑ See folio 1r.

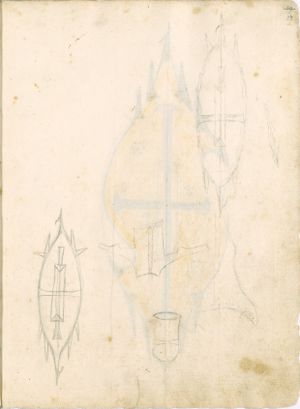

- ↑ The only other evidence that he was involved in the creation of the manuscript is the charge on the shield on folio 28r, which matches his presumptive heraldry on folio 102r of MS Thott.290.2º (1459); on the other hand, the escutcheon and the mantling are quite different between the two, so they cannot be said to be the same arms.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Hils. Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes. Peter Lang, 1985. p 73.

- ↑ Jens P. Kleinau. "Who was Luithold of Königsegg?". Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ↑ Hans-Peter Hils. Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes. Peter Lang, 1985. p42.

- ↑ Internally dated on folio 103v.

- ↑ Internally dated and dedicated on folio 16v.

- ↑ Jens P. Kleinau. "1467 The price of a fencing master". Hans Talhoffer ~ as seen by Jens P. Kleinau. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ↑ The Fellowship of Liechtenauer is recorded in three versions of Paulus Kal's treatise: MS 1825 (1460s), Cgm 1507 (ca. 1470), and MS KK5126 (1480s).

- ↑ Hans-Peter Hils. Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes. Peter Lang, 1985. p176.

- ↑ Illustration is traced from bleed-through from the other side, and then painted.

- ↑ Unleserliche Streichung. Illegible deletion.

- ↑ Verblasst oder übermalt, ergänzt nach Wolfenbüttel. Faded or painted over, completed according to Wolfenbüttel.

- ↑ Illustration is traced from bleed-through from the other side.

- ↑ Partly cut off.

- ↑ Or possibly kend.

- ↑ Difficult to decipher because of damage.

- ↑ Difficult to decipher because of damage.

- ↑ The right margin is lost due to clipping; the page seems to have been glued in subsequently.

- ↑ Rest cut off.

- ↑ Prefaced by "Der stat in der vndern hut vn dem dritten stich"

- ↑ Prefaced by "Hie hat er verseczt Im die schäre"

- ↑ A portion of the page is missing.

- ↑ Parts of the text are illegible in my present copy since they are written on a dark background.

- ↑ The manuscript is missing three pages prior to the current first page, preceding the Recital

- ↑ Preceded by a version of the Recital.

- ↑ Verhalten has multiple meanings, including “to lurk”, “wait for”, and “to hold fast to, maintain something”.

- ↑ Or “gauntlets”

- ↑ Schranken/Schränken means to close off a space by blocking entry and/or exit. Lexer lists one possibility as specifically relating to tournaments [turnieren].

- ↑ Muotwille is the drive to carry something out, which can equally have positive or negative roots, justifications, outcomes. According to Lever and Grimm, in the case of legal writing only, mutwille is represented as “the opposite of that which is demanded by law”.

- ↑ Mort = murder = premeditated killing in secret in ENHG, as listed in Grimm. However, there is also influence from the French morte, which simply means to kill (without the association with murder).

- ↑ Or “treachery”.

- ↑ Kämplich ansprechen = die förmliche Herausforderung zum Zweikampfe according to Lexer, which includes the “provocatio ad certamen” (challenge to combat) according to Grimm. This is not mere insult. This is a formal declaration.

- ↑ Lit. “baptismal”.

- ↑ This is not three different locations, but three successive meetings of the same court.

- ↑ Or “writing”.

- ↑ Lehrtage is a specific period of time prior to a single combat. Grimm: LEHRTAGE, m. plur. lehrzeit, lernzeit: (man soll) jhm sein lehrtag zum kampf zugeben, ... nemlich sechs wochen und drei tag. kolbenrecht bei Schottel 1238.

- ↑ I.e. has been called/labeled illegitimate, unauthentic, has lost legal rights derived from legal birth or marriage.

- ↑ Ertzögen: possibilities from Lexer: 1) could be the participial form from erziehen [Lexer] drawing a sword specifically upward, or raising/training humans and animals. 2) erzöugen = to show/demonstrate. 3) er zöugen = ehre zeigen to display honor. Possibilities from Grimm: 4) erziehen = to raise a sword, to swing a sword or axe, to educate, bring up, train up, to lift up.

- ↑ Or “mood”.

- ↑ Or “overseers”.

- ↑ Or “injured”.

- ↑ Vrum from Lexer includes pretty much all of the virtues of a knight: tüchtig, brav, ehrbar, gut, trefflich, angesehn, vornehm, wacker, tapfer, that is, capable, virtuous, honorable, good, excellent, respected, genteel (well-bred), brave, and courageous.

- ↑ Or “abridge”.

- ↑ I.e. student.

- ↑ Literally “information-gathering”.

- ↑ Probably onomancy based on his baptismal name (which is included in an earlier manuscript Talhoffer owned) and/or astrology based on his date of baptism.

- ↑ Schränken are the barriers used to form the ring/square/space for combat.

- ↑ This is a religious confession to a priest, in case he dies.

- ↑ St. John the Apostle was known for blessing a poisoned cup of wine, where the poison left in the form of a snake. Johannesminne or Johanneswein became customary throughout Germany in the 12th c. Numerous examples are found in: Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli: Handwörterbuch des deutschen Aberglaubens, Bd. 4, Berlin 1932, Sp. 745–760.

- ↑ I.e. within the boundaries of the combat ring.

- ↑ The sun travels clockwise.

- ↑ Sessel usually refers to a seat of honor, generally a chair with a back and arms.

- ↑ Or “extend”.

- ↑ A Bahre is a horizontal means of carrying something, and may refer to both a Tragbahre, a litter for the injured, and also a Totenbahre, a litter for the dead. “Bier”, which is a cognate, has a narrower definition than the original.

- ↑ Or “keep in mind”.

- ↑ General note for verbs: verbal noun phrases (das + verb), will be translated as “the [action]”, not as gerunds.

- ↑ Schenckel can specifically indicate the thigh/upper leg (its precise meaning), or simply the leg.

- ↑ This is specifically the piece of defensive clothing that covers the buttocks. The picture shows a short, sleeve-less piece of clothing, like a jerkin, while the word refers to the longer piece of clothing, the gambeson.

- ↑ This could potentially be a dislocation of the shoulder.

- ↑ Hals refers to the soft parts of the neck.

- ↑ Or “strangle”.

- ↑ Bube is both a male child, a servant, squire, an undisciplined man, or a professional dice player. Multiple references to Buben and dice (Würfel) in the literature make this a likely pun. Lexer: Buobe, der würfel machet buoben vil Ls. 3. 231,15. 480,116; Mart. 56, 91. 73,1. 206,85. Pass. K. 161,41. Marlg. 222, 296. 362,75.

- ↑ Or “encompassing”.

- ↑ Or “violence”.

- ↑ Or “swaying”, “rocking”; Waben is related to honeycomb and bees, and to the back-and-forth, up-and-down movement of water. Even the relationship to wëben is through bees and honeycomb, not weaving, which has different roots to get to weben.

- ↑ MHG mort/mord was another form of “dead”, loaned/borrowed from French morte. However, in ENHG, it does have a more violent aspect than tot. It is not until modern German that Mord picks up the sense of “murder”.

- ↑ Erstechen implies a mortal wound, beyond the mere thrust of stechen.

- ↑ Hals here indicates the back of the neck/shoulder.

- ↑ Or “tear”.

- ↑ The earlier meaning of nôt is to be threatened, hemmed in, imperiled; however, it can also be used as a replacement for the term battle/combat, as that state already implies peril and threat. Nothstand is a later compound, and is both a predicament/peril/threat, and a state of being under predicament/peril/threat. Interestingly, it is also used in the north in a very narrow meaning for the horizontal crosspiece that stands behind a dyke gate (Balkensiel as opposed to a culvert) that prevents the gate from opening.

- ↑ Or “The combative stance prior to the blow”.

- ↑ Or “The cut from above forward of the thrust”.

- ↑ Toben/täuben: to force, tame, subdue, deafen, with an aspect of irrational fury.

- ↑ Or “The fire (spark) protection”. Schiure, schûren: schützen, beshützen, in connection with schirmen; schüren: to stimulate, poke the fire to burn higher; scheuern, fegen = scouring away, sweep.

- ↑ Mair's note?

- ↑ This is Kittelvers: there are 4 major beats in each line, with a lot of unstressed syllables, particularly in the first line.

- ↑ Or “the flight/fleeing ones”.

- ↑ In a banner

- ↑ In a banner.

- ↑ Pentecost in 1459 fell on May 14th.

- ↑ Literally "burn-shears".

- ↑ Or lemen?

- ↑ Literally "hand-shoe".

- ↑ opposition

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 "Bochen" is a guard.

- ↑ guard

- ↑ Or possibly "wirg"

- ↑ Korrigiert aus »ihm«. Corrected from “ihm”.

- ↑ Over-hasty, miss-the-mark

- French Translation

- Hungarian Translation

- Slovenian Translation

- Spanish Translation

- Translation

- CC BY-SA 4.0

- Public Domain

- Copyrighted

- CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- GNU GPLv3

- Masters

- German

- Archery

- Arming Sword

- Armored Fencing

- Dagger

- Flail

- Grappling

- Longshield

- Longsword

- Man vs. Woman

- Messer

- Mounted Fencing

- Physical Training

- Pole Weapons

- Staff Weapons

- Sword and Buckler