|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Martin Huntsfeld"

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

== Textual History == | == Textual History == | ||

| + | [[file:Huntsfeld stemma.png|400px|left|thumb|Provisional stemma codicum expanded from Jaquet and Walczak]] | ||

| + | It's difficult to say when Huntsfeld's treatise was written, and the original is certainly lost at present. | ||

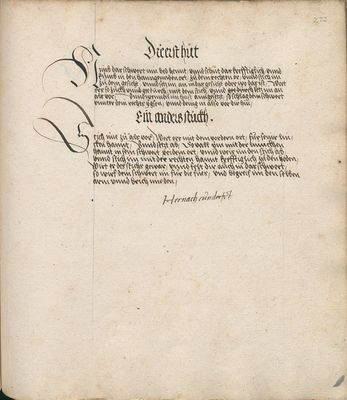

| − | + | The oldest extant copy of any of Huntsfeld's works is the [[Starhemberg Fechtbuch (Cod.44.A.8)|Rome version]] (1452); this is also the only manuscript to include all three texts attributed to him. The [[Goliath Fechtbuch (MS Germ.Quart.2020)|Kraków version]] (1535-40) was probably based on this manuscript (or one just like it),<ref>Welle (2017), p. 45.</ref> though it shows occasional expansions by a later author, especially in the grappling treatise; the scribe also adds two references to illustrations in the short sword and eleven in the grappling, but these were never executed. The relationship of [[Glasgow Fechtbuch (MS E.1939.65.341)|Glasgow version Ⅰ]] (1508) to Rome is unclear, but it also attributes the sword and buckler text to Lignitzer, and is the only manuscript apart from Rome and Kraków to include the grappling text. Both Glasgow Ⅰ and the [[Johan Liechtnawers Fechtbuch geschriebenn (MS Dresd.C.487)|Dresden version]] (1504-19), which only includes the sword and buckler but has a very complete copy of it (apart from being unattributed), might descend independently from the original Lignitzer text. | |

| − | |||

| − | The oldest extant copy of any of Huntsfeld's works is the [[Starhemberg Fechtbuch (Cod.44.A.8)|Rome version]] (1452); this is also the only manuscript to include all | ||

The second-oldest extant copy is [[Codex Lew (Cod.I.6.4º.3)|Augsburg version Ⅰ]], dated to the 1460s, which is based on an earlier manuscript possibly commissioned by [[Lew]].<ref>Jaquet and Walczak (2014), p. 121.</ref> and only includes the armored fencing, which it attributes to [[Martin Huntsfeld]], and a fragment of the sword and buckler text, which it leaves unattributed. The [[Codex Speyer (MS M.I.29)|Salzburg]] (1491), [[Pirckheimer's Fechtbuch (Pirckh.Papp.353)|Nuremberg]] (ca. 1500), [[Oplodidaskalia sive Armorvm Tractandorvm Meditatio Alberti Dvreri (MS 26-232)|Vienna Ⅱ]] (ca. 1505), [[Über die Fechtkunst und den Ringkampf (MS 963)|Graz]] (1539), [[Maister Liechtenawers Kunstbuech (Cgm 3712)|Munich]] (1556), and [[Fechtbuch zu Ross und zu Fuss (MS Var.82)|Rostock]] (1565-70) versions also descend from this lost Lew manuscript in some way, but their relationships to each other aren't always clear<ref>Jaquet and Walczak (2014), p. 122.</ref>—Munich's sword and buckler is based on Augsburg and Vienna Ⅱ is based on Nuremberg, but the others seem to descend independently from earlier lost versions (and have more complete copies of the sword and buckler than Augsburg and Munich). | The second-oldest extant copy is [[Codex Lew (Cod.I.6.4º.3)|Augsburg version Ⅰ]], dated to the 1460s, which is based on an earlier manuscript possibly commissioned by [[Lew]].<ref>Jaquet and Walczak (2014), p. 121.</ref> and only includes the armored fencing, which it attributes to [[Martin Huntsfeld]], and a fragment of the sword and buckler text, which it leaves unattributed. The [[Codex Speyer (MS M.I.29)|Salzburg]] (1491), [[Pirckheimer's Fechtbuch (Pirckh.Papp.353)|Nuremberg]] (ca. 1500), [[Oplodidaskalia sive Armorvm Tractandorvm Meditatio Alberti Dvreri (MS 26-232)|Vienna Ⅱ]] (ca. 1505), [[Über die Fechtkunst und den Ringkampf (MS 963)|Graz]] (1539), [[Maister Liechtenawers Kunstbuech (Cgm 3712)|Munich]] (1556), and [[Fechtbuch zu Ross und zu Fuss (MS Var.82)|Rostock]] (1565-70) versions also descend from this lost Lew manuscript in some way, but their relationships to each other aren't always clear<ref>Jaquet and Walczak (2014), p. 122.</ref>—Munich's sword and buckler is based on Augsburg and Vienna Ⅱ is based on Nuremberg, but the others seem to descend independently from earlier lost versions (and have more complete copies of the sword and buckler than Augsburg and Munich). | ||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

[[Paulus Hector Mair]]'s three manuscripts—[[Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica (MSS Dresd.C.93/C.94)|Vienna]] (1540s), [[Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica (Cod.icon. 393)|Munich]] (1550s), and [[Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica (Cod.10825/10826)|Vienna]] (1550s)—are unique in a few ways. They are also descended from the original Lew manuscript, though Jaquet and Walczak suggest that Mair may have accessed multiple different copies of the short sword treatise and attempted to unify them.<ref>Jaquet and Walczak (2014), pp. 118-120.</ref> The dagger treatise, meanwhile, seems to have been copied from Egenolff. Mair's initial compilation manuscript (Dresden) was subsequently translated into Latin, and this text is found in Munich and Vienna (which has both languages), marking the first time Liechtenauer texts were translated into Latin. | [[Paulus Hector Mair]]'s three manuscripts—[[Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica (MSS Dresd.C.93/C.94)|Vienna]] (1540s), [[Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica (Cod.icon. 393)|Munich]] (1550s), and [[Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica (Cod.10825/10826)|Vienna]] (1550s)—are unique in a few ways. They are also descended from the original Lew manuscript, though Jaquet and Walczak suggest that Mair may have accessed multiple different copies of the short sword treatise and attempted to unify them.<ref>Jaquet and Walczak (2014), pp. 118-120.</ref> The dagger treatise, meanwhile, seems to have been copied from Egenolff. Mair's initial compilation manuscript (Dresden) was subsequently translated into Latin, and this text is found in Munich and Vienna (which has both languages), marking the first time Liechtenauer texts were translated into Latin. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Treatises == | == Treatises == | ||

Revision as of 02:44, 7 May 2025

| Martin Huntsfeld | |

|---|---|

| Born | date of birth unknown |

| Died | before 1452 |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Nationality | German |

| Movement | Fellowship of Liechtenauer |

| Genres | |

| Language | Early New High German |

| Notable work(s) |

|

| Manuscript(s) |

MS M.I.29 (1491)

|

| First printed english edition |

Tobler, 2010 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

Martin Huntsfeld (Martein Hündsfelder, Huntfelt[1]) was an early 15th century German fencing master. Based on his surname, his family likely comes from the village of Hundsfeld, about 20 km east of Würzburg (alternatively, he might be from Psie Pole, a district of present-day Wrocław). While Huntsfeld's precise lifetime is uncertain, he seems to have died some time before the creation of the Starhemberg Fechtbuch in 1452.[2] The only other thing that can be determined about his life is that his renown as a master was sufficient for Paulus Kal to include him in the list of members of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer in 1470.[3]

Huntsfeld authored treatises on armored fencing (both with the short sword and unarmed), dagger, and mounted fencing; some manuscripts (including the Augsburg, Salzburg, Nuremberg, Graz, Munich, and Rostock versions) erroneously credit to his armored teachings to Lew, while ascribing the armored fencing treatise of Andre Lignitzer to Huntsfeld instead.[4]

Beginning with the Augsburg version (and later also in the works of Mair), the mounted fencing gloss attributed to Lew concludes with the poem that begins Huntsfeld's mounted teachings. It's likely that the manuscript was planned to include the entire mounted fencing treatise, but it was either never completed or, since the poem falls at the end of a quire, that the final quire containing it was later lost from the manuscript. The Vienna and Rostock versions further complicate the matter by including the poem separately from the Lew gloss but not including the Huntsfeld section either. The fact that the poem was eventually transmitted separately from either work suggests that it might not be the work of Huntsfeld at all. These versions are all listed here for lack of a better claim to authorship.

Contents

Textual History

It's difficult to say when Huntsfeld's treatise was written, and the original is certainly lost at present.

The oldest extant copy of any of Huntsfeld's works is the Rome version (1452); this is also the only manuscript to include all three texts attributed to him. The Kraków version (1535-40) was probably based on this manuscript (or one just like it),[5] though it shows occasional expansions by a later author, especially in the grappling treatise; the scribe also adds two references to illustrations in the short sword and eleven in the grappling, but these were never executed. The relationship of Glasgow version Ⅰ (1508) to Rome is unclear, but it also attributes the sword and buckler text to Lignitzer, and is the only manuscript apart from Rome and Kraków to include the grappling text. Both Glasgow Ⅰ and the Dresden version (1504-19), which only includes the sword and buckler but has a very complete copy of it (apart from being unattributed), might descend independently from the original Lignitzer text.

The second-oldest extant copy is Augsburg version Ⅰ, dated to the 1460s, which is based on an earlier manuscript possibly commissioned by Lew.[6] and only includes the armored fencing, which it attributes to Martin Huntsfeld, and a fragment of the sword and buckler text, which it leaves unattributed. The Salzburg (1491), Nuremberg (ca. 1500), Vienna Ⅱ (ca. 1505), Graz (1539), Munich (1556), and Rostock (1565-70) versions also descend from this lost Lew manuscript in some way, but their relationships to each other aren't always clear[7]—Munich's sword and buckler is based on Augsburg and Vienna Ⅱ is based on Nuremberg, but the others seem to descend independently from earlier lost versions (and have more complete copies of the sword and buckler than Augsburg and Munich).

The Vienna Ⅰ (1480s) and Ortenburg (late 1400s) versions only include Lignitzer's treatises on sword and buckler and the dagger and are unattributed. Andre Paurenfeyndt's 1516 book Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey ("Foundation of the Chivalric Art of Swordplay") also includes these two treatises and is textually close to Vienna Ⅰ and Ortenburg, but Jaquet and Walczak demonstrate that it was not copied from Vienna and instead likely derived from the same earlier source;[8] it may instead have come from Ortenburg, which they didn't have access to. Paurnfenydt's book was later translated into French and published in Antwerp in 1538 by Willem Vorsterman under the title La noble science des ioueurs d'espee ("The Noble Science of Swordplay"); this was the first time a Liechtenauer text was translated into a second language. Additionally, Christian Egenolff included Paurnfeyndt's entire text in his compilation Der Allten Fechter gründtliche Kunst ("The Ancient Fencer's Foundational Art"), which was published in four editions between 1530 and 1558. And the Augsburg version Ⅱ is a faithful manuscript copy of Paurnfeyndt's book executed by Lienhart Sollinger in 1564. Glasgow version Ⅱ a fragment of dagger that also seem to descend from this branch, and this was copied into Munich alongside the sword and buckler fragment from Augsburg Ⅰ.[9]

Paulus Hector Mair's three manuscripts—Vienna (1540s), Munich (1550s), and Vienna (1550s)—are unique in a few ways. They are also descended from the original Lew manuscript, though Jaquet and Walczak suggest that Mair may have accessed multiple different copies of the short sword treatise and attempted to unify them.[10] The dagger treatise, meanwhile, seems to have been copied from Egenolff. Mair's initial compilation manuscript (Dresden) was subsequently translated into Latin, and this text is found in Munich and Vienna (which has both languages), marking the first time Liechtenauer texts were translated into Latin.

Treatises

Short Sword

Illustrations |

Rome Version (1452) |

Augsburg Version Ⅰ (1460s) |

Vienna Version (1480s) |

Ortenburg Version (late 1400s) |

Salzburg Version (1491) |

Nuremberg Version (ca. 1500) |

Glasgow Version (1508) |

Kraków Version (1535-40) |

Graz Version (1539) |

Dresden Version (Mair) (1542) |

Vienna Version-German (Mair) (1550s) |

Munich Version (Mair) (1550s) |

Vienna Version-Latin (Mair) (1550s) |

Augsburg Version Ⅱ (1553) |

Munich Version (1556) |

Rostock Version (1570) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[1] Here you rise to well respected Master Martin Hundfeldt's art of combat with the shortened sword in harness from four guards

|

[87r.1] Hie hebt sich an Maister Marteins Hundtfeltz kunst Dem got genädig seÿ Mit dem kurtzen swert zu° champf In harnasch aus vier hu°ten |

[54r] Hie hebt sich an meister lewen kunst fechtens In harnasch auß den vier hutten zu fus vnd zu kampffe etc. w[11] Er ab synnet |

[124v.1] Das seind maister marteins Hunczfeld fechtenn Im harnasch aus den vier hüetten |

[130r] Item hie hebet sich an meinster lulben künst fechtes ÿn harnisch aüß den vier hüten zü füß vnd zü kanff ~ Wer ab sÿnnett |

[100v.1] Das ist Maister Merteins hüncz feldes Fechten In harnckh auß vier hutñ |

[254r] Die vier hutten zu Fůoß Im Harnasch zů Kempffen Wer absinnet |

[19v.1] Das fechten jnn harnasch aus vier hueten, |

[58r] Hie hernach hebt sich an meister lebenn [58v.1] kunst fechtens im harnisch aus den vier hutenn tzu fus vnnd tzu kampff. Wer absinnet, fechtens zu fus beginnet, der schick sein sper, tzu Iglichem anhebenn recht wer, Nim denn Vorstich on forcht, spring vnnd setz im an, Widertzuck das gesigt im an, wiltu vor stechenn, mit tzuckenn wer ler brechenn mer wil er tziehenn, von schaidenn wil fliehenn, so solt im nohenn, vnd weislich wart des vohenn. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[2] Mark that this is the first guard: Take your sword in both hands and do so strongly, and come into the hanging point to the right ear, and stab at his face, and attack him in the face or anywhere else, if he wards then disengage, and go through with the stab, and attack him as before, and when you have reached him, then set your sword under your right armpit, and thus force him ahead of you. |

[87r.2] Merck das ist die erst hu°t Nÿm das swert in paid hend vnd schüt das krefftigcleich vnd kum in den hangenden ort zw dem rechten ör vnd stich ÿm zw dem gesicht vnd setz ÿm an in das gesicht oder wo das ist Wert ers so zuck vnd gee durch mit dem stich vnd setz Im an als vor vñ wenn du ÿm hast an gesetzt So schlach dein swert vnder dein rechtzs vchsen vnd dring ÿn also von dir hÿn ~ |

[54v.1] Item das ist die erst hut Nÿm dein swert In baide hende vnd schütt das krefftiglichen vnd komme In den hangenden ort zum rechten or vnd stich In zum gesicht vnd setze Im an das gesicht oder wo das ist Wert ers so zuck vnd gee durch mit dem stich vnd setze Im an hals vor Vnd wenn du Im hast angesetzet so slach dein swert vntter dein rechte üchsen vnd dring In also von dir hin etc. |

[124v.2] dy erst huett [125r.1] nymb das swert in paid hennt vnd schüt das krefftiklich vnd chum in den hangenden ort zw dem rechtenn or vnd stich im zw dem gesicht vnd secz im an in das gesicht oder wo das ist wert ers so zuck vnd ge durch mit dem stich vnnd secz im an als vor vnd wenn dw im hast angeseczt so schlach dein swert vnder dein rechtz vechsenn vnd vonn dir als vor |

[130v.1] Die erst hutt Item Nÿm din schwertt In beyde hende vnd schutt daß krefftiglichen vnd küm in den hangendenn ortt zu dem rechten or vnd stich ÿm zu dem gesicht oder wo das ist Wertt ers so zuck vnd gee durch mit dem stich vnd setz im an hals vnd wenn du hast Im an gesetz so schlag din schwertt vnter den rechten vchsenn vnd tring In also vor dir hÿnn ~ |

[100v.2] It~m das ist diey erst hüt Nÿm das swert payde hendt Vnd schucze das kreftikliche~ vnd küm In den hange~den Ort / zu dem Rechtñ Or / Vnd stich Im zü dem gesicht Vnd secz im an in das gesicht Oder wo das ist weret ers so zück Vnd gee durch mit dem stich Vnd secz im an als vor vnd wen dü im hast an geseczt so schlach dein swert vnder dein rechcz vchsen vnd dring In also von dier hin : |

[272r.1] Die erst hut Nimb das schwert inn bed hennt, unnd schut das krefftiglich, unnd kumb in den hanngennden ort, zu dein rechten or, unnd stich im zu dem gesicht, unnd setz im an in das gesicht oder wo das ist, Wert ers so zuckh unnd gee durch, mit dem stich, unnd gee durch setz im an als vor, Unnd wenn du im hast anngesetzt, so schlag dein schwert unnter dein rechts ÿgsen, unnd dring in also vor dir hin. |

[254v.2] Item das Ist die erst hüt Nimb dein schwert Inn baid hennd vnnd schůt das krefftigelichen vnnd kům Inn den hanngen den Ort zům rechten ohr vnnd stich Im zum gesicht vnnd setz Im an das gesicht oder wa das ist weert ers so zůckh vnnd gee durch mit dem stich vnnd setze Im ann hals vor vnnd wann dů Im hast angesetzet so schlag dein schwert vnnder dein Rechten Vchsen vnnd trinng In allso vonn dir hin |

[19v.2] Item die erst huet, nym das schwert jnn baide hennd, vnd schütt das Krefftigelich, vnd kum jnn dem hangenden ort, zu dem rechten Or, vnd stich jm zu dem gesicht, vnd secz jm an jn das gesichtt, oder wo das ist, wört er es, so zuckh, vnd gee durch mit dem stich, vnd secz jm an als vor, vnd wenn du jm hast angeseczt, so schlach dein schwert vnder dein rechts Ichssen, vnd dring in also von dir hin, |

[58v.2] Item das ist die erst hut, nim dein schwertt in beid hendt, vnnd schut das kreftiglichenn vnnd kum in denn hangendenn ort, tzu dem Rechtenn or, vnnd stich in tzu dem gesicht, vnd setz im ann in das gesicht, oder wo das ist, wert ers, so tzuck vnnd gehe durch mit dem stich, vnnd setz im an hals vor, vnnd wenn du im hast angesetztt, so schlag dein schwert, vnter dein Rechte vchsenn, vnd dring in also vor dir [59r.1] hin. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

[3] A second play Stab to him as before, if he wards it with the forward point before his left hand, and sets it aside, then follow him with the left hand on his sword by the point, and push his stab off, and stab strongly to his crotch with the right hand. If he is wary of the stab, and also drops to your sword, then throw your sword in front of his feet, and push him or grab with the same arm, and then break him. |

[87r.3] Ein anders stuck Stich Im zu° als vor Wert ers mit dem voderñ ort fur seiner lincken hant vnd setzt an So val ÿm mit der lincken hant in sein swert peÿ dem ort vnd weis ÿm den stich ab vnd stich ÿm mit der rechten hant krefftigklich zw den hoden Wirt er des stichs gewar vnd felt dir auch in das swert So würf dein swert ÿm für die fuess vnd vach Im oder begreif ÿm den selbigen arm~ vnd prich ÿm den ~ |

[54v.2] Item ein anders Stich Im zu dem hals vor Wert ers mit dem vordern ortt von seiner lincken hantt vnd setz ab So fall Im mit der lincken hant In sein swert pej dem ort vnd weiß Im den stich ab vnd stich In mit der rechten hant kreff= [55r.1] tiglichen zu den hoden Wirt er des stichs gewar vnd fellt dir auch In das swert So las dein swert Im für die füs fallen vnd vach vnd begreiff denselben arm vnd prich Im den als du wol waist etc. |

[125r.2] Das annder stuck stich im zue als vor wert ers mit dem vnndern ort vonn seiner tenncken hannd so secz ab vnd fal im mit der tenncken hand in sein swert bey dem ort vnd reyb im denn stich ab vnd stich in zw der rechtenn hannd krefftikleich zw denn höden wirt er des stichs gewar vnd felt dir auch in das swert so würff dein swert im fur die füeß vnd begreyff in bey dem selbenn arm vnnd prich im denn also |

[130v.2] Item Ein anders Stich im zu dem halß als vor wertt ers mit dem vordern ortt von siner lincken hant vnd setz ab so fal im mit der lincken hant an sin schwertt bÿ dem ortt vnd wieß im den stich ab ~ vnd stich ym mit der rechten hant krefftiglichenn zu den hodenn wurtt er des stichs gewar vnd valt dir auch in das schwertt So loß im din schwertt fur die fuß vallenn vnd foch oder begriff den selben arm vnd brich ÿn ÿm als du dan woll weÿßtt |

[100v.3] It~m ein ander stich im Zu als vor / Weret ers mit dem voderñ ort sein lingen hant / vnd secz ab so fall Im mit der linggen handt In sein swert pei dem ort vnd weiß Im den stich ab vnd stich in mit der rechten hãdt crefftiklichñ Zü den hodñ Wiert er des stichß gewar vñ Feldt dier In das swert so Wirf dein swert Im fir die fieß vnd fach in oder be greiff im den selbñ arm~ vñd prich in[12] im als du wol wayst : |

[272r.2] Ein anders stuckh. Stich ime zu als vor, Wert ers mit dem vordern ort, fur seinr lincken hannt, Unnd setzt ab, So vall ÿm mit der linnckhen hannt in sein schwert pei dem ort, unnd weis im den stich ab, unnd stich im mit der rechten hannt kreffiglich zu den hoden, Wirt er des stichs gewar, unnd felt dir auch in das schwert, so wirf dein schwert im fur die fues, und begreif im den selben arm unnd brich ime den. Hernach runderfet[!] |

[254v.3] Item ain annders Stich Im zů dem hals vor wehret ers mit dem vordern orth seinner linncken hand vnnd setzt ab so fall Im mit der linncken hannd aůs sein schwert beÿ dem orth vnnd weÿs Im den stich ab vnnd stich In mit der Rechten hannd krefftigclichen zů den hoden wirt er des stichs gewar vnnd fellt dir aůch Inn das schwert so lass dein schwert Im fůr die fůess fallen Fach vnnd begreiff den selben Arm vnnd prich Im den als dů wol waist |

[19v.3] Item ein annders, stich jm zu als vor, wört er es mit dem fordern ort, von seiner linckhen hannd, vnd seczt ab, so fall jm mit der linckhen hannd jnn sein schwert, bei dem Ort, vnd weise jm den stich ab, vnd stich jm mit der rechten hannd Krefftigelich zu den hennHoden wirt er des stichs gewa, vnd fellt dir auch jnn das schwert, so wirff dein schwert jm für die fuß vnd fach jn oder begreiif jm den arm, vnd brich jm in als du wol waist |

[59r.2] Item ein anders, stich im tzu dem hals vor, wert ers mit dem vordernn ort, von seiner lincke[n] handt, vnnd setzt ab, so fal im mit der linckenn handt in sein schwert bey dem ort, vnnd weis Im denn stich ab, vnnd stich in mit der Rechten handt kreftiglich zu denn hoden, wirt er des stichs gewar vnnd felt dir auch in das schwert, so las dein schwert im fur die fus fallenn, vnnd fahe oder begreif denn selbenn arm, vnnd prich in Im als du wol weist. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

[4] Another You also want to strike him to the throat with the pommel from the high guard, or on the arm joint of the forward hand, or in the knee joint of the forward foot, and if he will ward this, when you strike him against the knee joint, and will over-reach you above, then displace his strike at the hilt, and put your point in his face. |

[87r.4] Ein anders Auch magstu aus der oberñ hu°t mit dem kloß des swertz im zw dem haubt [87v.1] schlahen oder auf die arm~ püg der vor gesatzten hant oder in die knÿepüg des voderñ fuess vnd wil er dir das werñ wenn dw In schlechst nach der knÿepüg vnd wil dich oben vberlauffen So vorsetz ÿm den schlack mit dem gehultz vnd setz Im den ort in sein gesicht ~~~ |

[55r.2] Dunderslege Item ein anders Auch magstu aus der obern hut mit dem knopf des swertz In zum haubt slahen oder auf die arm bug des vordern fußes Vnd wil er dir das wern wann du Im schlechst nach den kniepügen vnd will dich oben über lauffen So versetze Im den slag mit dem gehültz vnd setz Im den ort In sein gesichte etc. |

[125r.3] Auch magstu aus der obern huet mit dem chnopf des swercz im zw dem hawbt slachenn oder auf die armpüg der vor gesaczten hand oder in die chnyepug des vodernn fuess vnd wil er dir dann wern wenn dw im slechst nach der chnyepug vnd wil dich obenn vberlauffenn so versecz im denn slag mit dem gehilcz vnnd setz Im denn ort in sein gesicht |

[130v.3] Item Ein anders Auch machstu auß der obern hutt mit dem knopff des schwertes ym zu dem haupt schlagenn Oder auff die arm bug des vorderenn fusses Vnd will er dir dz werenn wen du ym schlechst noch den dem kniebogenn vnd wil dich obenn vber lauffenn so versetz Im den schlag mit dem gehultz ab vnd setz Im den ort in sin gesichtt |

[100v.4] It~m ein anders auch magstu auß der oberñ hüt mit dem kloß des swertes In zü dem haubt schlachñ ode° die arm~ pich X des foderñ fusses vnd wil er dier des weren wen du in stichst nach der knie püg vñ wil dich obñ yber lauffen so ver secz Im den schlag mit dem hilcz vnd secz in den ort in sein gesicht |

[273r] Ein annders. Auch magstu aus der obernn huet, mit dem klos des schwerts, in zu dem haubt schlahen, Oder auf die armpug, der vor gesatztn hannt, Oder in die kniepug, des vordern vues, ~ Unnd will er dir das wern, Wenn du im schlechst nach der khniepug, unnd will dich oben ÿberlauffen, So versetzt im den schlag mit dein gehultz, und setz im den ort in sein gsicht. |

[255r.1] Dunderschleg Item ain annders Auch magstů auß den obern hůtten mit dem knopff des schwerts Inn zum haůpt schlachen oder aůf die armpůg des fordern fůoß vnnd will er dir das wehren wann dů Im schlecht nach den kniepůgen vnnd will dich oben vberlaůffen so versetz Im den schlag mit dem gehůltz vnd setz Im den Ort Inn seinn gesicht |

[20r.1] Item einannders, auch magstu aus der obern huet, mit dem Glos des schwerts jn zu dem haubt schlahen, oder auff die arm, peug der vorgeseczten hannd, oder jm die knyepüg des fordern fueß, will er dir das wöhrn, wenn du jm schlechst nach der knyepüg, vnd wil dies oben vberlauffen, so versecz jm den schlag mit dem gehilcz, vnd secz jm den ort jnn sein gesicht, |

[59r.3] Item ein anders, auch magstu aus der oberhut mit dem knopff des schwerts in tzu dem haupt schlagenn, oder auff die arm pug des fordernn fus, vnnd wil er dir das werenn, wen du Im schlechst, nach dem knypogenn, vnd wil dich obenn Vberlauffenn, so versetz im den schlag mitt dem gehiltz, vnnd setz im denn ort in sein gesicht. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

[5] Note: That which one strikes with the pommel, is known as the thunder strike which you also want for under the eyes, striking to the visor with it. |

[87v.2] Item was man mit dem knopf schlecht das haissen die doner sleg dw magst In auch vnder die augen in das visir do mit slachen |

[55v.1] Item Was man mit dem knauff slecht das heissen die dvnder sleg Du magst In auch vntter die augen In das visir damit slahen |

[125r.4] was man mit dem chnopf slecht da magst dw in auch vnder die augenn in das gesicht mit slachenn |

[130v.4] Item was man mit dem knauff schlecht dz heissent [131r.1] die dünder schleg du ein auch vnder die ougenn schlagenn in daß visier ~ |

[100v.5] It~m Was man mit dem knopff schlecht das hayssñ die demer schlech du magst in auch vnder die augen in das visier da mit schlachen ~ |

[273v.1] Was mit dem knopt schlecht, das haissen die donner schleg, du magst in auch unnther die augen schlahen, in das visir domit schlahen. |

[255r.2] Item was man Mit dem knopff schlecht das haissen die Donnerschleg du magst Inn aůch vnnder die aůgen Inn das Visier damit schlagen |

[20r.2] Item was man mit dem knopff schlacht, das haisset die Donnerschlag, du magst in auch vnder die augen, jnn das fisier damit schlagen, |

[59r.4] Item was mann mit dem knopff schlecht, das heissenn die donerschleg, du magst in auch vnter die augenn das visir damit schlagenn. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

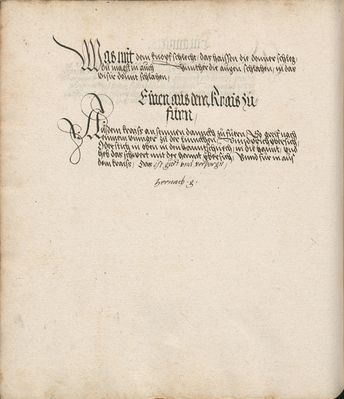

[6] Note: Mark when one leads in a circle at his pleasure, So attack to the left against a finger, and break upward, or stab him above into the gauntlet and in the hand, and lift the sword upward with the hand, and lead him in a circle, know that this is good, and also secret. |

[87v.3] Item merck einen aus dem kraiß zu° füren an seinen danck So greif nach eine~ vinger zw° der lincken vnd prich vber sich Oder stich In oben in den hantschuech in die hant vnd heb daz swert mit der hant vber sich vnd für In aus dem kraiss wisse das ist gu°t vnd auch ver porgen ~ |

[55v.2] Ein verporgen stuck Item merck Wiltu einen über sein danck Im kreiß vmb füren so greiff nach einem vingern zu der lincken hant vnd prich übersich oder stich Im oben zu den hantschuchen In die hant vnd heb das swert mit der hant übersich vnd für In aus dem krais Das ist gut vnd auch verporgen etc. |

[125r.5] Wild dw ainem aus aus [!] dem chrais vnder seinen danck farenn so greyf nach einem vinger aucz [?] der tennckenn hannd vnd prich vbersich oder stich in obenn in denn hanntschuech In die hannd vnnd heb das swert mit der hannd vber sich vnd far im aus dem chraiss |

[131r.2] Item merck wiltu eynenn vber danck in dem kreiß vmb furenn so griff nach eynem finger zu der lincken hant vnd brich vbersich oder stich ym obenn zu dem hantschuch in die hant vber sich vnd fur In auß dem kreiß dz ist gut vnd auch vorborgen |

|

[273v.2] Einen aus dem Krais zufurn. Aus dem kraiß an seinnen dannckh zu fuern, So greif nach einnem vinnger zu der linnckhen, Unnd prich ÿbersich, Oder stich in oben in den hanntschuech, in die hannt, und heb das schwert mit der hennt ÿbersich, Unnd fur in aus dem kraiß. Das ist guet und verporgn. hernach gemalt |

[255v.1] Ain verporgen stuckh Item merckh willtu Ainnen ober sein dannckh Im Kraiß vmb fieren so greiff nach ainnen finger zu der linncken hannd vnnd brich obersich oder stich Im oven zů den hanndschůchen Inn die hannd vnnd heb das schwert mit der hannd vbersich vnnd fier In aůß dem krais das ist gůt vnnd aůch Verporgen |

|

[59r.5] Item [59v.1] merck wiltu einenn vber sein danck Inn dem kreiß vmbfurenn, so greif nach einem finger tzu der linckenn handt vnnd prich vbersich, oder stich im obenn tzu denn handt schuchenn in die hanndt vbersich, vnnd fur in aus dem kreiss das ist gut vnnd auch verborgenn. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

[7] Note: If you will throw a man who has attacked you, then grasp over with the left hand over his left, and take the weight by his left elbow, this is good. |

[87v.4] Item wildu einen man werfen der dir hat an gesetzt So vbergreif mit der lincken vber sein lincke vnd nÿm das gewicht peÿ seinem lincken elpogen das ist gu°t ~ |

[56r.1] Niderwerffen Item Wiltu einen man werffen der dir hat angesetzt So übergreiff mit der lincken hant über sein lincken Vnd nÿm das gewicht pej seinem lincken elnpogen. |

[125r.6] Wild dw einenn werffenn der dir hat angeseczt so vber greyff mit der tennckenn sein tenncke vnd nym das gewicht bey seinem tenncken elpogenn |

[131r.3] Item wiltu eynen man werffenn der dir hat an gesetz so vber griff mit der lincken hant vber sin lincke vnd nym daß gewiechtt peÿ synem lincken elnbogen |

[101r.2] It~m Wiltu einen man werffe~ der dier hat an gesacz so vber greyff mit linckñ vber sein lincke vnd nim das gewicht pey seinem lincken elpoge~ vnd das ist g[ut] |

[255v.2] Niderwerffen Item wiltü ainen Man werffen der dir hat angesetzt so vbergreiff mit der linncken hannd vber seinn linncken vnnd Nim das gewicht beÿ seinnem linncken Elenvogen |

[20r.4] Item wiltdu einen werffen, der dir hat angeseczt, so vbergreiff mit der linckhen, vber sein linckhe, vnd nym das gewicht bey seinem linckhen Elnbogen |

[59v.2] Item wiltu einenn man werffenn der dir hat angesetzt so vbergreif mit der linckenn handt vber sein lincke, vnnd nim das gewicht bey seinem linckenn Elnpogenn. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[8] Counter it thus When he will grasp through, then counter his hand ahead with your sword by the vambrace. |

[87v.5] Also prich das Wenn er durch greiffen wil So prich ÿm die hant vorñ peÿ dem gelied mit deine~ swert ~ |

[56r.2] Bruch. Item wider das Wann er greiffen will So prich Im die hant forn pej dem glid mit dem swert. |

[125r.7] Ein pruch wider das wenn er durch wil wil [!] greyffenn so prich im die hannd vor pey dem glid mit deinem swertt |

[131r.4] Item wider daß wan er griffen will so prich im die hant vorn bÿ dem glitt mit dem schwertt |

[101r.3] It~m ein pruch wider das / wen er durch greÿffen will so prich Im die handt vore~ pey dem~ gelidt mit deinem swert |

[256r.1] Brüch Item wider das Wann er greiffen will so prich Im die hannd vornen beÿ dem glid mit dem schwert |

[20r.5] Item ein pruch wider das, wenn er durch greiffen will so prich jm die hannd vorn bey dem Glid, mit deinem Schwert, |

[59v.3] Item vnder das wenn er greiffenn wil, so prich im die handt vorn bey dem glid mit dem schwert. Item die and~ hut. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[9] This is the second guard for combat in harness Take the sword in both hands, and hold it over your knee, and go to the man. If he then stabs below to you then don't ward him but attack him to his face. |

[87v.6] Das ist die ander hu°t In harnasch zu° kampf Nÿm das swert in paide hend vnd haldes vber dein knÿe vnd gee zu° dem mann Sticht er dir denn vnden zu° so wer ÿm nicht sunder setz ÿm an sein gesicht |

[56r.3] Item die ander hut. Item Nym das swert In beid hend vnd halt es über dein knie vnd gee zum man Sticht er dir vnden [56v.1] zu so wer Im nicht Sunder setze Im an sein gesicht etc. |

[125r.8] Das ist die ann der huet zw champf in harnasch nym das swert In paid hennd vnd halt es vber dem chnye vnd ge zu dem man sticht er dir vndenn zue so wer im nicht Sunnder secz im in sein gesicht |

[131r.5] Die ander hut Item Nÿm daß schwert in beidenn hend vnd halt es vber dyn knye vnd gee zu dem man Sticht er dir vnten zu wind im nicht Sunder setz ym an sin gesicht |

[101r.4] Das ist die ander huet Nym das swert in paÿde hende vñ halde es vber dein knÿe vnd gee zu dem man / sticht er dier vnden zü so wer im nicht / sunder secz im an sein gesicht |

[274v.1] Das ist die annder huet ~ Nimb das schwert in baide hennt unnd halts ÿber dein knie, Unnd gee zum man, ~ Sticht er dir dann unnden zu so wer im nicht, sunder setz ime an sein gsicht. |

[256r.2] Die annder hüt Item nimb das schwert Inn baid hennd vnnd hallt es ober dein knie vnnd gee zům asann sticht er dir vnnden zů so wehr Im nit sonnder setz Im an sein gesicht |

[20v.1] Das ist Nun der ander huet Nym das schwert jnn baide hennd vnd halt es vber den knye, vnd gee zu dem man sticht er dir vnden zu so wöhre jm nicht, sunder secz jm an sein gesicht, |

[59v.4] Die annder hut & Item nim das schwert in beid hendt, vnnd halt es vber dein knie, vnnd gehe tzu dem mann, sticht er dir vntenn tzu, so wer im nicht, sonder setz im ann sein gesicht. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

[10] Or if he stabs above be it to your face or anywhere else, then set his stab off with the forward part of your sword, and attack him to the face, or to the throat, and set your sword under your armpit, and force him ahead of you. |

[87v.7] Oder [88r.1] Sticht er dir oben zu° es sei zu° dem gesicht oder wo es ist So secz ÿm den stich ab mit dem voderñ tail deines swertz vnd setz ÿm an in das gesicht oder an die drossel vnd schlach dein swert vnder dein vchsen vnd dring für dich |

[56v.2] Item Sticht er dir oben zu es sej zum gesicht oder wo es ist das soltu weren vnd setze Im den stich ab mit dem vordern teil deins swertz vnd setze Im In das gesichte oder an den trüssel vnd slag dein swert vntter dein ṽchsen vnd dringe für dich. |

[125r.9] sticht er dir denn aber obenn zue es sey zw dem gesicht oder wo das das sey das sold dw wernn vnd seczenn Inn denn stich ab von dem vodernn tayl des swertz an die prüst vnd secz Im das gesicht oder in die trossel vnd schlach dein swert vnder dein vechsen vnd dring in fur dich |

[131r.6] Item sticht er obenn zu Eß sy zu dem gesicht oder wo es sÿ daß soltu werenn vnd setz ym den stich ab mit dem vordern teill dines schwertes vnd setz Im In daß gesicht oder in den druessell vnd schlag din swertt vnter dÿn vchßenn vnd dring vor dich |

[101r.5] It~m sticht er dier obñ zu es sey zu dem gesicht oder wo es ist das soltu were~ |

[274v.2] Oder sticht et dir oben zu, wo das sey. So setz im den stich ab mit dem vordern tall[!] deins schwerts, unnd setz im an in das gesicht, Oder an die drossell, ~ Unnd schlag dein schwert unnter dein ÿgsen, Unnd dring fur dich, |

[256r.3] Item sticht Er dir oben zů zům gesicht oder wa Es ist das soltů wehren vnnd setz Im den stich ab mit dem vordern thail deinnes schwerts vnnd setz Im In das gesicht oder an den trůssel vnd schlag dein schwert vnnder dein linncken Vchsen vnnd tring fůr dich |

[59v.5] Item sticht er dir oben tzu, es sey tzu dem gesicht, oder wo es ist, das [60r.1] soltu werenn, vnnd setz im denn stich ab, mit dem vordernn teil deines schwerts, oder setz im in das gesicht oder ann denn drüßel, vnd schlag dein schwert vnnter dein Vchsenn, vnnd dring fur dich. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[11] Or set it aside between your two hands, and drive the pommel around his neck, and put your right foot in front of him, and so he falls. |

[88r.2] Oder setz ab zwischen deinen zwaien henden vnd var Im mit dem knopf vmb sein hals vnd vor setz ÿm mit deine~ rechten fuess vnd fell In also ~ |

[56v.3] Item oder setz ab zwischen deinen baiden henden vnd far Im mit dem knopff vmb sein hals vnd fürsetze Im mit deinem rechten fus vnd felle In also |

[125r.10] oder secz ab zwischenn den zwainen hennden vnd far im mit dem chnopf vmb sein hals vnd versecz im mit deinem rechtn fueß vnd fel in also // |

[131r.7] Item Oder setz ab zwuschen dinen beyden henden vnd far ym mit dem knopff vmb sin hals vnd vor setz ym mit dynem rechten fuß vnd fell in also ~ |

[101v.1] It~m oder secz ab zwischen deinem zweÿen henden Vnd far Im mit dem knopff vmb sein halß vnd versecz Im mit deine~z Rechtñ fueß vnd fell in also |

[274v.3] Oder setz ab zwischen deinen zwaien hennden, Unnd far im mit dem khnopf umb seinn hals, Unnd fursetz im mit deinem rechtn fues so velt er. |

[256v.1] Item oder setz ab zwischen baiden hennden vnd far Im mit dem knopff vmb sein hals vnnd fůrsetz Im mit deinnem rechten fůoß vnnd feel In allso |

[60r.2] Item oder setz im ab tzwischenn deinenn baiden hendenn vnd far im mit dem knopf vmb sein hals, vnnd fürsetz im mit deinem Rechtenn fus, vnnd fel in also. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[12] A counter against this Take the arm well, and wrench around and try the arm break. |

[88r.3] Ein pruch wider das Nÿm des ar~ms war vnd raid vmb vnd treib den arm~ pruch |

[57r.1] Bruch Item Nym des arms war vnd treib vmb vnd treib den arm pruch |

[125r.11] Ein pruch wider das Nym des arms war vnd reyb vmb vnd treyb denn armpruch |

[131v.1] Ein bruch Item Nym daß arms war vnd drÿtt vmb vnd tribe den arm bruch |

[101v.2] It~m ein prüch Wider das Nÿm des arm~es war vnd reid vmb vnd treib den arm pruch |

[275r.1] Bruch.. Nimb des arms war, unnd raid umb, Unnd treib den armpruch. |

[256v.2] Bruch Item Nimb des Arms wahr vnnd treib vmb vnnd treib den Armprůch |

[60r.3] Item nim des arms war, vnd trit vmb vnnd treib denn Armpruch. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[13] Note: When you displace then drive above with the handle over his forward driven handle, and pull it to you, and counter, and attack. |

[88r.4] Item wenn du vor setzt so var vber mit der hanthab vber sein vor gesatztew hanthab vnd zeuch zu° dir vnd prich vnd setz an |

[57r.2] Item aber far über mit der hanthab über sein vorgesatzte hant Vnd zeuch In zu dir vnd prich vnd setze an etc. |

[125r.12] vnd far vber mit der hannd vber vorgeseczte hannd vnnd zeuch zw dir vnd prich vnd secz ann |

[131v.2] Item Aber far vber mit der hantt vber syn vor gesetzen hant vnd zuch In zu dir vnd brich vnd setz Im ann ~ |

[101v.3] It~m oder Far vber mit der hant hab vber sein vor gesaczte handt vnd zuch zu dier vnd prich vnd secz an |

[275r.2] Wenn du versetzt, so far ÿber mit der hannthab, ÿber sein vor gesetzte hannthab, unnd zeuch zu dir, unnd prich unnd setz an, |

[256v.3] Oder far ÿber Mit der hanndthabe ÿber sein vorgesetzte hannd vnnd zůck In zů dir vnnd prich vnnd setz an |

[60r.4] Item aber far vber mit der hant, vnnd tzeuch in tzu dir, vnnd prich vnnd setz ann. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[14] Or change through, and set aside with the pommel. |

[88r.5] Oder wechsel durch vnd setz ab mit dem kloß |

[57r.3] Item oder wechsel durch vnd setz ab mit dem klossen. |

[125r.13] oder wechsel durch vnnd secz mit dem chnopf |

[131v.3] Item oder wechsell vnten durch vnd setz ab mit dem kloßem |

[101v.4] It~m oder wechsel durch vnd secz ab mit dem kloß |

[275r.3] ~ Oder wechsl durch, unnd setz ab mit dem klos. |

[257r.1] Item oder Wechsel důrch vnnd setz ab mit dem klossen |

[60r.5] Item oder Wechsel durch vnd setz ab mit dem klössen. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[15] Break this thus: Take the pommel well with the left hand and thrust back behind the sword, and stab, below to the testes. |

[88r.6] Also prich das Nÿm des klosses war mit der lincken hant vnd stos Im das swert hinder ruck vnd stich vnden zu° den hoden ~ |

[57r.4] Bruch Item prich das also Nÿm des klosses war mit der lincken hant vnd stos Im das swert In den ruck vnd stich Im vnden zu den hoden etc. |

[125r.14] also prich das nym des chnopfs war mit der tennckenn vnd stöß im das swert vber ruck vnd stich vnnden zw denn hodenn |

[131v.4] Ein bruch Item bich dz Nym des kloßes war mit der lincken hant vnd stos ym dz swertt in den ruckenn vnd stich Im vnden zu den hodenn ~ |

[101v.5] It~m also prich das Nÿm klosses war mit der lincke~ vnd stoß Im das swert hinder ruck vnd stich vnden zu den hodñ |

[275r.4] also prich das. Nimb des clos war, mit der linckhen hannt, Unnd stos ime das schwert hinnter ruckh, und stich unden ~zu den hodenn ~ |

[257r.2] Brüch Item prich das allso Nimb des klosses war mit der Linncken hannd vnnd stöß Im das schwert Inn den růcken vnnd stich Im vnnden zů den hoden |

[60r.6] Item prich das also nim des klosses war mit der linckenn handt, vnnd stoß Im das schwert in denn Ruck, vnnd stich im vntenn tzu denn hodenn. Die drit hut. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[16] This is the third guard for combat in harness Take the sword in both hands, and stand in your hanging by the right side so that the left foot stands forward, and when someone stabs to you, or will strike with the pommel, or will attack to you, then stab him to his forward hand. |

[88r.7] Das ist die dritt hu°t Zu° kampff In harnasch Nÿm das swert in paide hend vnd stee in dem geheng peÿ der rechten seittñ also daz der linck fues vor stee vnd wenn Jenär auf dich sticht oder wil slachen mit dem kloß oder wil dir an setzen so stich ÿm zu° seiner vorgesatzten hant ~ |

[57v.1] Die dritt hut. Item Nym das swert In baid hende vnd stee Im gehenck pej der rechten seitten also das der linck fus vor stee vnd gener auf dich stichett oder wolt slahen mit dem klos oder wil dir ansetzen so stich Im zu seiner versatzten hant etc. |

[125r.15] Die trit huet zw champf in harnasch nym das swert in paid hennd vnd ste in dem gehenng bey der rechtenn seytenn also das der tennck fues vor ste vnnd wenn ainer auf dich sticht oder wil slachn mit dem chnopf oder wil dir anseczen so stich zw deiner vorgesaczten hand durch |

[131v.5] Die dritte hutt Item Nÿm dz swertt in bede hende vnd ste in dem gehenck bÿ der rechten sytenn Also das der linck fuß fur stee vnd generer vff dich stichett oder wolt schlagen mit dem kloß oder will dir an setzen so stich im zu sÿner versatzung in die hant ~ |

[101v.6] Das ist die dritt huett It~m Nim das swert In payde hendt vnd ste In dem gehenge pey der Rechtñ Seytñ also das der linck fueß for / Stee vnd wen gener auff dich sticht oder will schlagñ Zu deiner vorgesacztñ handt |

[275r.5] Die drit huet. Nimb das schwert in bede hennt, Unnd stee in dem gehenng, beÿ der rechten seittn, also das der linckh vues vorstee, Unnd wenn er auf dich sticht, Oder will dir schlahen, mit dem glos, oder will dir ansetzen, ~ So stich im zu seinr vor gesatztn hannt. |

[257r.3] Die drit hüt Item nimb das schwert Inn baid hennd Vnnd stee Im gehennckh beÿ der rechten seitten allso das der Linnck fůoß vor stee vnnd wen Iene[r] aůf dich sticht oder wollt schlagen mit dem kloß oder will dir ansetzen so stich Im zů seiner versetzten hannd |

[60r.7] Die drit hut. Item nim das schwert in beid hendt, vnnd stehe in dem gehenck bey der Rechtenn seittenn, also das der linck fus vor stehe, vnnd gener auf dich stichett, oder wolt schlagenn, mit dem kloß, oder [60v.1] wil dir ansetzenn, so stich im tzu seiner vorsatzten handt. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[17] Another Or stab through over his hand, and over his sword, and push the pommel to the ground, and attack. |

[88r.8] Ein anders Oder stich vber seiner hant durch vnd vb° sein swert vnd druck den knopf zw der erden vnd setz an ~ |

[57v.2] Item oder stich über sein hant durch vnd über sein swert vnd druck den knopf zu der erden vnd setz an. |

[125r.16] vnd ṽber sein swert vnd druck denn chnopf zw der erdenn vnnd secz an |

[131v.6] Item oder stich vber sin hant duech vnd vber sin swertt vnd druck den knopff zu der erdenn vnd setz Im an |

[101v.7] It~m Oder stich Vber seiner handt durch Vnd vber sein swert durch vn druck den knopff zu der erdñ vnd secz an |

[275v.1] Ein annders... Oder stich ÿber seinner hannt durch, unnd ÿber sein schwert, unnd druckh den knopf zu der erden unnd setz an. |

[257v.1] Item oder stich Vber sein hannd důrch vnd vber sein schwert vnnd truckh den knopff zů der Erden vnnd setz an |

[60v.2] Item oder stich vber sein handt durch, vnd vber sein schwert, vnnd truck den knopff tzu der erdenn vnnd setz an. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[18] Yet another Or strike through to his forward driven elbow with the pommel. |

[88r.9] Aber ein anders [88v.1] Oder slach Im zu° mit dem knopf zu° dem vorgesatzten elpogen |

[57v.3] Item oder slag mit dem knauff zu dem vorgesatzten elnpogen |

[125r.17] Oder slach im zue mit dem chnopf zw dem vorgesacztenn elpogenn |

[131v.7] Item nÿm vnd schlag mit dem knopff zu dem vor gesatzttem elnbogenn |

[101v.8] It~m Oder schlach Im züu mit dem knopff zu dem vorgesaczñ elpogñ |

[275v.2] aliud Oder schlag ime zu dem vorgesatzten elbogen mit dein knopff, oder unden zu dem elbogen, |

[257v.2] Item Nim schlag Mit dem knopff zů tem vorgesatzten Elenpogen |

[60v.3] Item nim vnd schlag mit dem knauff tzu dem vorgesatztenn Elnpogenn. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[19] Or below to the elbow, and against the sword hard on the blade, and under the right armpit or onto the knee. |

[88v.2] oder vnden zw° dem elpogen vnd das swert wider gefast peÿ der klingen vnd vnder das recht vchsen oder auf das knÿe |

[57v.4] Item oder slag In vnden zum elnpogen [58r.1] Vnd das swert wider gefast pej der clingen vnd vntter der gerechten üchsen oder auff das knie etc. |

[125r.18] oder slach vndenn zw dem chnopf elpogenn vnd das swert wider geuast zw dem der chlingenn vnnd vnder das recht vechsenn oder auf das chnye |

[131v.8] Item oder schlag Im vnden zu dem elnbogem vnd dz swertt wider gefast by der klÿngem vnd vnder [132r.1] der gerechten vchsenn oder vff dz knye ~ |

[101v.9] It~m oder schlach Im vndn zuu dem elpogen Vnd das swerdt wider gefast pey der klingñ vñ vnter das recht vchsen oder auff das knÿe / |

[257v.3] Item oder schlag In Vnden zům Elennpogen vnnd das schwert wider gefast beÿ der klingen vnnd vnnder der rechten Vchsen oder das knie |

[60v.4] Item oder schlag in vntenn tzu dem Elnpogenn vnnd das schwert wider gefast bey der klingen, vnnd vnter der gerechtenn vchsenn oder auf das knie. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

[20] Note if he attacks on the middle of your sword to your face strong from the edge then quickly shove out. |

[88v.3] Item felt er dir in das swert in der mitt das geschicht gerñ von tzagkeit so zewnn ims rasch aus |

[58r.2] Item felt er dir In das swert In der mitten das geschicht gern von zagheit So rausch auf. |

[125r.19] velt er in das swert In der mitt das geschicht gern von zaghait so zwen im resch |

[132r.2] Item felt er dir in dz swertt in der mitten das geschiecht gern von zagheitt so rausch auch auff |

[102r.1] It~m Feldt er dier In das swerdt in der mitte das geeschicht gerñ võ zagkaÿt so zew°n im rasch auß / |

[275v.4] Felt er dir in das schwert in der mit, So zeün imbs aus. |

[257v.4] Item fellt er dir Inn das Schwert Inn der mitten das gschicht geren vonn zagkait so raůsch aůf |

[60v.5] Item felt er dir in das schwert in der mittenn, das geschicht gernn von tzaghait, so rausch auff. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[21] Note if he attacks you on the point then lift the sword over the head, and take the sword in both hands, and pull to you and strike him to his forward hand that he holds ahead to the attack, or to the knee joint, and grasp the sword again by the blade, and take advantage of the knee. |

[88v.4] Item felt er dir in die spitz so heb das swert vber das haubt vnd nym das swert in paide hende vnd ruck an dich vnd slach ÿm zw° der voderñ hant die er hat vor geseczt oder zu° der knÿepüg vnd begreif wider das swert mit der klingen vnd gelegt auf das knÿe ~ |

[58r.3] Item felt er dir In die spitzen so heb das swert über das haubt vnd nym das swert in beid hende vnd ruck an dich vnd slag Im zu der vordern hant die er hat fürgesetzt oder zu der kniepüg vnd begreiff wider das swert mit der clingen vnd gelegt auf das knie. |

[125r.20] Wenn er dir in denn spicz velt so heb das swert vber das haubt vnd nym das swert in In [!] ped hennd vnd ruck an dich vnd schlach in zw der vodernn hannd die er hatt vir geseczt oder zue der chnye pug vnd begreyff das swertt wider bey der chlingenn vnd gelegt auf das chnye chnye [!] |

[132r.3] Item felt er dir in die spitzenn so hab dz swertt vber daß haupt vnd nÿm dz schwertt in beyde hende vnd rück an dich vnd schlag In zu der vordern hant die er hat fier gesetz oder zu der knÿepug vnd griff wider dz schwertt mit der clingem vnd geleg vff daß knye ~ |

[102r.2] It~m feldt er dier in die spitz so heb das swert vber das haubt Vñ nym das swertt in payde hendte vñ ruck an dich Vñ schlach Im zuu der forderñ handt dye er hat fyr geczt Oder zuw der knie pich Vnd pegreÿff Wider das swert mit klingñ Vnd gelegt auff das knye |

[275v.5] Felt er dir in die spitz. So heb das schwert, ÿber das haubt, unnd nimb das schwert in baide hennt, Unnd ruckh an dich, und schlag im zu der fordern hannt, die er hat vorgesetzt, oder zu der khniepug, und begreif wider das schwert, mit der clinngen und legs auf das khnie. |

[258r.1] Item fellt er dir Inn Die spitzen so heb das schwert vber das haůpt vnnd nimb das schwert Inn baid hennd vnnd růckh ann dich vnd schlag Im zů der vordern hannd die Erhat fůrgesetzt oder zu der kniepůg vnnd begreiff wider das schwert mit der klinngen vnnd gelegt aůf das knie In die hůt |

[60v.6] Item felt er dir in die spitzen, so heb das schwert vber das haupt, vnnd nim das schwert in baid hendt, vnnd Ruck an dich, vnnd schlag im tzu der fordernn handt, die er hat furgesetzt, oder tzu der kniepug, vnd greif wider das schwert mit der klingenn, vnnd gelegt auf das knie in die hut. Die viert hut. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[22] This is the fourth guard for combat in harness Take the sword under the right armpit, and go to the man with an attack, and attack him to the face, If he wards then disengage or attack him to the throat or to the shoulder, or under the armpit and force him thus from you, and when you have attacked then let him not come off, and if he then will come to you with strikes, and will work with the pommel, then follow him by pressing after, and don't let him come off to attack or stab again, when he does he will be short, this is an art to know. |

[88v.5] Das ist die vierd hu°t zu° kampf In harnasch Nÿm das swert vnder das recht vchsen vnd gee an den mann mit an setzen vnd setz ÿm an · an das gesicht Wert ers so zuck oder setz Im an die drossel oder an die achsel oder vnder die vchsen vnd dring in also von dir hin vnd wenn du hast an gesatzt so lass in nicht ab kömen vnd wil er denn mi zu° dir mit slegen vnd mit dem knopf arbaitten so volg Im nach mit nach raisen vnd lass In nicht ab kömen so mag er weder geschlahen noch gestechñ wenn er wirt ÿm zu° kurtz das ist die kunst das wisse ~ |

[58v.1] Die vierd hut Item das swert nym vntter die rechten ṽchsen vnd gee an den man mit ansetzen vnd setze Im an das gesicht Wert ers so ruck oder setz Im an den rüssel oder an die achsel oder vntter die ṽchsen vnd tring In also von dir hin Vnd wann du hast angesetzt So las In nit abkommen so mag er weder geslagen noch gestechen Wenn es würt Im zukurtz vnd das ist die kunst das wisse. |

[125r.21] Die vierd huet zw champf in harnasch nym das swert vnder das recht vechsenn vnnd ge ann denn man mit anseczenn vnd secz ann das gesicht wert ers so zuchk vnnd secz im an denn drossenn oder an die achsel oder vnnder die vechsenn vnnd drinng In also vonn dir hin dann vnnd dw hast abgeseczt so las in nicht abchömen vnd will er zw [125v.1] Dier mit slegenn vnd mit dem chnopf arbaitenn volg im nach mit nachraysen vnnd laß nit ab chumenn so mag er weder ge slahenn noch gestechenn wann es wierd zw churcz |

[132r.4] Die vierde hut Item Nÿm das schwertt vnter die rechten vchsen vnd ge an den man mit an setzen vnd setz ÿm an daß gesicht wertt ers so ruck oder setz ym an den drÿssell oder an die achssell oder vnder die vchsen vnd dring yn also von dir hÿn vnd wenn du hast an gesetzett so loß ÿn nicht ab kümenn so mag er weder geschlagenn noch gestechen wan es wirtt ÿm zu kurtz vnd dz ist die künst daß wiesse ~ |

[102r.3] Dye Vyert huodt / It~m Nÿm das swertt vnder das recht vchsen vnd gee an den man mit an seczñ vnd secz Im an an das gesicht / wert erß so zuck oder secz Im an dye drossel Oder an dye achselñ oder vnd° die vchsñ vnd dring in also von dier hin vnd wen du hast an gescztt so laß in nicht ab ku~en vñ wil er dier den zu dier mit schlegñ vñ mit den knopff arbettñ Volg Im nach mit nach rayssñ vñ laß in nich kume~ so mach er weder geschlagñ noch gestechñ wan es wiert im zu kurcz vñ das ist die kunst das wisse / |

[276r.1] Die Viert Huet Nimb dein schwert unnder das recht ÿgsen, Unnd gee an den man mit ansetzen, unnd setz ime an, in das gsicht, ~Wert ers, so zuckh oder setz ime an die drossel, oder an die agsel Oder unnther die ygsen, und tring in also vor dir hin, und wenn du hast angesetzt, so laß in nit abkhumben, Und will er dann zu dir mit schlegen, Unnd mit dem knopf arbaitn, ~So volg im nach mit nachraisen, und laß in nit abkhumen, somag er weder schlahen noch stechen, Wenn er wirt im zu kurtz, das ist die kunst das Wisse. |

[258r.2] Die wiert hüt Item das schwert Nimb vnnder die rechten Vchsen vnnd gee an den asan mit ansetzen vnnd setz Im an das gesicht wehrt ers so růckh oder setz Im an den trůfel oder an die Achsel oder vnnder die Vchsen vnnd trinng In also vonn dir hin vnnd wann dů hast angesetzt so laß In mit abkummen so mag Er nieder schlagen noch stechen wann Es wirt Im zů kurtz vnnd das ist die kůnst das Wisse |

[60v.7] Die vierdt hut. Nim das schwert vnnter das Recht vchsenn [61r.1] vnnd gehe ann denn mann mit annsetzenn, vnd setz im an das gesicht, wert ers, so ruck oder setz im ann denn drüssel, oder ann die achselnn, oder vnter die vchsenn, vnnd dring in also vonn dir hin, Vnnd wann du hast anngesetzt, so las inn nit abkummenn, so mag er weder geschlagenn noch gestechenn, Wann es wirt im tzu kurtz, vnnd das ist die kunst das wiß. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[23] Of attacking Mark all who would attack to do so, to the face or to the throat and to the left shoulder, or under the armpit, and thus force him. |

[88v.6] Von an setzen Merck alles das du wil an setzen das [89r.1] setz an · an das gesicht oder an die drossel oder an die linck achsel oder vnder die vchsen vnd dring in also ~ |

[58v.2] Item merck alles das du wilt ansetzen das setze an das gesicht oder an den trüssel oder an die [59r.1] lincken achsel oder vntten an die üchsen vnd albeg vntter die rechten ṽchsen vnd dring In also von dir hin weck etc. |

[125v.2] was dw an seczenn wild das secz an das gesicht ann die drussel oder an die tennck achsel oder vnnder die ṽechsenn vnd dring in also von dir hin / |

[132r.5] Item merck alles daß dü willt ansetzen daß setz in das gesicht oder an den druessel oder an die lincke achsell oder vnten an die vchsen vnd alweg vnten die die rechten vchsen vnd dring In also vor dir hin wegtt |

[102r.4] Daß ist von an seczñ It~m merck alles das du an wild secze~ das secz an an das gesicht Oder an dye drossel oder an dye linck achksel Oder vnder vichsen vñ dring In also von dyer hin |

[258v.1] Item merckh altes das du wilt ansetzen Das setz an das gesicht oder an den trůfel oder an die Linncken achsel oder vnnden an die Vchsen vnnd alweg vnnder die rechten Achsen vnnd trinng Inn allso von dir hinnweckh |

[61r.2] Item merck alles das du wilt ansetzenn, das setz ann das gesicht, oder ann denn drussel, oder ann die linckenn achselnn, oder vntenn ann die vchsenn, vnd dring in also vonn dir hinwegk. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

[24] Note: Mark, as you attack him to his left side then step off with the left foot. Or if you attack him to his right side then step off with the right foot, and stride ahead, and hit him on a side, if he withdraws the side then stab him to the head, know this is the best offense against people. |

[89r.2] Item merck eben setztu Im an · an sein lincke seitten so tritt ab mit dem lincken fuess Oder setzstu Im an · an der rechten seitten so tritt ab mit dem rechten fuess vnd lauf für dich vnd druck In auf ein seitten vnd lest er dir die seitten so stos in auf die hauben Wiße das ist das chranckist an dem menschen ~ |

[59r.2] Item merck eben Setzestu Im an die rechten seitten so dritt ab mit dem lincken fus Oder setzstu Im an die lincken seitten So dritt ab mit dem rechten fus vnd lauff für dich vnd truck In auf ein seitten vnd lest er dir die seitten so stos In auf die hauben. Wisß das ist das krenckest am menschen etc. |

[125v.3] Item merck ebenn seczt im ann die rechtenn seytenn so trit ab mit dem tennckenn fueß seczt dw im an die rechten seytenn so trit ab mit dem rechtn fues secz dw im ann der tennckenn seytenn so tritt ab mit dem rechtenn fueß vnd lauf im durch vnd druck In an ein seytenn vnd lät er dier dy seytenn stoß in an die haubenn das ist das chrennckist an dem mennschenn |

[132v.1] Nota Item Merck eben setz du Im an die rechte syten so tritt so trit ab mit dem lincken fuß oder setz du Im an den lincken siten So tritt ab mit dem rechten fuß vnd lauff fier dich vnd truck In vff ein siten vnd lest er die siten so stos in vff die hauben wis daß ist das krenckest an dem menschen |

[102v.1] It~m merck ebñ secz tu im an / an die rechtñ seitñ so trit ab mit dem linckñ fueß oder secztu Im an / an der lincke~ seÿtñ so trit mit dem rechtñ Fueß vnd lauff Fyr dich vnd druck In auff ein seÿttñ vnd lest er dier die seyttñ so stoß in auff dye haubñ Wisse das ist das crenkist an dem menschñ / |

[276r.2] ansetzen. |

[258v.2] Item merkch oben Setz dů Im an die rechten seitten so trit ab mit dem linncken fůoß oder setzstů Im an die linncken seitten so trit ab mit dem Rechten fůoß vnnd laůf fůr dich vnnd trůckh Inn aůf ain seiiten vnnd last Er die seitten so stoß In aůf die haůben wiß das ist das krennckest am mentschen |

[61r.3] Item setztu im an die rechtenn seittenn, so trit ab mit dem linckenn fus, oder setzt im an der linckenn seittenn, so trit ab mit dem Rechtenn fus, vnnd lauf fur dich, vnnd truck in auf ein seittenn, vnnd lest er dir die seittenn, so stoß in auff die haubenn, wiß das ist das krenckest ann dem menschenn. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[25] Note: Mark, when you have attacked, and he is longer, then at the same time you hit ahead of yourself so that his point goes off upward, and he is fully attacked in the gorget. |

[89r.3] Item merck wenn du Im hast an gesetzt vñ ist er lenger wenn du so druck also geleich für dich hin ab das der ort vber sich auf gee vnd Im wol in die ring gesatzt seÿ |

[59r.3] Item merck Wann du Im hast angesetzt vnd ist er lenger denn du [59v.1] so druck also gleich für dich hin das der ort übersich auf gee vnd In wol In die ring gesetzt |

[125v.4] Wenn dw im hast an geseczt vnd ist er lenger wenn dw so druck also geleich fur dich hin ab das der ort also geleich vber sich ge vnd im wol in die ring geuast |

[132v.2] Item Merck wen du Im hast an gesetz vnd ist er lenger dan du So truck also glich fur dich hin dz der ort vber sich auff gee vnd In woll in die ringenn gesetz ~ |

[102v.2] It~m merck wen du Im hast an gesecz vnd ist er lenge~ den du so druck also gleich Fÿr dich hin ab das der ort vber sich auf gee vnd Im wol in die ringe geseczt |

[258v.3] Item merkch wann Du Im hast angesetzt vnnd ist er lennger dann dů so trůckh allso gleich fůr dich hinn das der Ort vber sich aůf gee vnnd In wol Inn die rinng gesetzt |

[61r.4] Item merck wen du Im hast angesetzt, vnnd ist der lenger dann du, so [61v.1] truck also gleich fur dich hin das der ort vbersich auf gehe, vnnd In wol in die Ring gesetzt. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

[26] Note: When he is shorter then you let your sword sink off below to the right hip, and as before go out upward with the point, and below the gorget is well attacked as before, and don't let him come off, he will then work with the pommel so observe the pressing after with the point so he can come to nothing as you observe, and is good. |

[89r.4] Item ist er kurtzer wenn dw so lass dein swert mit der hant absincken vncz auf die recht hüf vnd als vor vber sich auf mit dem ort vnd vntter die ring wol gesatzt als vor vnd lass In nicht ab chöm~en Wil er denn mit dem kloss arbaitten so merck das nachvolgen mit dem ort so kan er zu° kainen dingen ku~men das ist zu° merckñ vnd ist gu°t ~ |

[59v.2] Item vnd ist er kürtzer denn du so las dein swert mit der hant absincken pis auf die rechten hüff vnd also far über sich auf mit dem ortt vnd vntter die ring die ring [!] wol gesatzt als vor vnd las In nit abkommen Vnd will er dann mit dem klos arbeitten So mercke das nachuolgen mit dem ort so kan er zu kainen dingen kommen Vnd das ist gut etc. |

[125v.5] yst er churczer wenn dw so las dein swert mit der hannd absinckenn vncz auf die recht huff vnnd also var auf vbersich mit dem ort vnd vnder die ring wol gesaczt als vor vnnd laß In nit ab chömen vnnd wil er denn mit dem chnopf arbaitenn so merck das nach volgenn mit dem ort so chann er zw chainem ding nicht chumenn |

[132v.3] Nota Item Vnd ist er kurtzer dan du So loß din swertt mit der hant ab sinckenn bis auff die rechte hueff vnd also far vber sich vff mit dem ortt vnd vnder die ring wol gesatz als vor vnd loß in nicht ab kümen vnd wil er dan mit dem kloß arbeyten so merck dz noch volgenn mit dem ortt So kan er zu keynem andern kümen vnd ist gutt ~ |

[102v.3] It~m Vnd ist er kyrcze~ wen du so laß dein swert mit der hant ab sinckñ vncz auff die recht hyff vnd also far yber sich auff mit dem ortt vñ vntter dye ring wol gesaczt als vor vñ laß nit ab ku~en vñ wil er den mit dem kloß arbaitten so merck das nach volgñ mit dem ortt so kan er zu kaine~z dingñ kume~ das ist zu merckñ vñ ist guett |

[259r.1] Item vnnd ist Er kůrtzer dann dů so lass dein schwert mit der hannd ab stůcken biß aůf die rechten hůfft vnnd also far vbersich aůf mit dem Ort vnnd vnnder die rinng wol gesatzt als vor vnnd laß In nit abkommen vnnd will Er dann mit dem kloß arbaiten so merckh das nachůolgen mit dem ort so kan er zů kainnen dingen kommen vnnd das ist gůt |

[61v.2] Item vnnd ist er kurtzer dann du so las dein schwert mit der hanndt absinckenn, biß auf die Rechte hüf, vnnd also far vbersich auf mit dem ort, vnd vnter die ring wol gesatzt als vor, vnnd las in nicht abkummenn, vnnd wil er dann mitt dem kloß arbeittenn, so merck das nachfolgen mit dem ort, so kann er zu keinen dingenn kummen, vnnd das ist gut |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

[27] Mark the counter against the attack to the face or wherever it may be Stab him below to the hand that he has set forward on the blade, and thus lead him from the circle. |

[89r.5] Merck wider die an setzen in das gesicht oder wo das seÿ das prich also Stich ÿm vnden in die hant die er hat für gesetzt auf der klingen vnd für in also aus dem kraiss |

[59v.3] Item merck wider das ansetzen In das gesicht oder wo das sej [60r.1] Das prich also Stich In vntten In die hant die er hat fürgesatzt auf der clingen vnd für In also auß dem kreis etc. |

|

[132v.4] Ein bruch wider die ansetzüng Item Merck wider daß ansetzüng In das gesicht oder wuer daß sÿe daß brich also Sstich in vnten in die hant die er hat vor gesetz auff die clingen vnd fier In also avß dem kreyß ~ |

[102v.4] It~m merck wider das an secze~ / in das gesigt oder wo das seÿ das prich also stich in vnden in dye handt dier er hat fyr geseczt auff der klingñ vñ fyer In alsso auß den krayß / |

[276r.3] Merckh setztu in an sein linnckhe seittn, so trit ab mit dem linnckhen vues, Oder setztu im an die recht seitn so trit ab mit dem rechten fueß, Unnd lauf fur dich unnd druckh in auf ein seitten, ~ Unnd lesst er[20] dir die seittn, so stos in auf die hauben, Wiß das ist das chrannckhest am menschen. |

[259r.2] Ein pruch wider das annsetzen Item merckh wider das Ansetzen Inn das gesicht oder wa das seÿ das prich allso stich In vnnden Inn die hannd die er hat fůrgesetzt aůf der klinngen vnnd fůer In also aůß dem krayß |

[61v.3] Ein bruch wider die ansetzunng. Item merck wider das annsetzenn in das gesicht, oder wo das sey, das prich also, stich in vntenn in die handt, die er hat furgesatzt, auff der klingenn, vnnd fur in also aus dem kreiß, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[28] Note: Or stab him over his forward hand, and punch the sword down toward the ground with the pommel, and attack him. |

[89r.6] Item oder stich Im vber sein vorgesatztew [89v.1] Hant vnd druck das swert mit dem knopf nider zu° der erden vnd setz ÿm an ~ |

[60r.2] Item oder stich In über sein vorgesatzte hant vnd durch das swert vnd truck den knopff nider zu der erden vnd setze Im an. |

[125v.7] oder stich im vber sein vorgesaczte hand vnnd durch das swert vnd druck denn chnopf nyder zu der erdenn vnd secz ann |

[133r.1] Item Oder stich In vber seyn vor gesatzten hantt vnd druck dz swertt vnd den knopff nÿder zu der erden vnd setz Im ann ~ |

[102v.5] It~m oder stich Im vber seine forgesaczte handt vnd dürch das swerdt vñ durch den knopff nider zuder erden vñ secz Im an / |

[276r.4] Wider die ansetzn, in das gsicht oder wo das seÿ. Stich im unnden in die hannt, die er hat furgesetzt, auf der clingen, und fur in also aus dem krais, [276v.1] gesetzte hannt, unnd druckh das schwert, mit dem knopf nider zu der erden, und setz im an. |

[259r.3] Item oder stich In vber seinn vorgesetzten hannd Vnnd trůck dz schwert trůckh den knopf nider zů der Erden vnnd setz Im an |

[61v.4] Item oder stich in vber sein vorgesatzte handt, vnnd durch das schwert, vnnd truck den knopf nider zu der erdenn vnnd setz im an. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[29] Note: Or set him aside between both your hands, and with the pommel thrust before the throat, and below with the right leg set behind his left, he is then thrown over. |

[89v.2] Item oder setz ÿm ab zwischen deine~ zwaien henden vnd mit dem knopf gestossen für den hals vnd vnden mit dem rechten pain getretñ hinder sein lincks vnd dar über geworffen ~ |

|

[125v.8] oder secz im ab zwischenn deinen paidenn hennden vnd mit dem chnopf gestossenn fur den hals vnnd Vnnden mit dem rechtn pain getretn hinder sein tenckenn vnnd dar vber geworffenn |

[133r.2] Item Oder setz Im ab zwischen dÿnen beÿdenn henden mit dem knopff gestossen fur den hals vnd vnten mit dem rechten peÿn getretten hinter syn linkes vnd dan vber geworffen |

[103r.1] It~m oder secz Im ab zwische~ deine~ paÿden hendñ vnd mit dem knopff gestossen fir den halß vñ vnden mit dem rechtñ payn getretten hinders sein linckes vnd dar vber gbarffen / |

[276v.2] Stuckh [S]etz im ab, zwischen deinen zwaien hennden, unnd mit dem khnopf gestossen vier den hals, unnd unnden mit dem rechten bain getretten, hinter sein linckhs, Und daruber geworffen. |

[259v.1] Oder setz Im ab Zwischen deinnen zwaien hennden mit dem knopff gestossen fůr den hals vnnd vnden mit dem rechten pain getretten hinnder seinn linkes vnd darůber geworffen |

[61v.5] Item oder setz im an tzwischenn seinenn tzweien [62r.1] hendenn, mit dem knopf gestossenn fur den hals, vnnd vntenn mit dem Rechtenn pain getretenn hinter sein linckes, vnnd darüber geworffen. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[30] Note: Or set him aside with the point, and attack him to his face. |

[89v.3] Item oder setz ÿm ab mit dem ort vnd ym angesetzt an sein gesicht |

[60v.1] Item oder setz In ab mit dem ortt vnd Im angesatzt an sein gesicht |

[125v.9] oder secz im ab mit dem ort vnd im angesicht an sein gesicht |

[133r.3] Item oder setz Im ab mit dem ort vnd Im angesetz an sin gesichtt |

[103r.2] It~m oder seczt Im ab mit dem ort vnd Im ab vñ Im an gesaczt an sein angesicht / |

[259v.2] Item oder setz Im ab mit dem Ort vnnd Im angesatzt an seinn gesicht |

[62r.2] Item oder setz inn ab mit dem ort, vnnd Im angesatzt ann sein gesicht. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

[31] Or change through with the pommel, and set it aside with it. |

[89v.4] Oder wechsel durch mit dem knopf vnd setz da mit ab |

[60v.2] Item oder durchwechsel mit dem knopff vnd setz damit ab. |

[125v.10] Item der durchwechsel mit dem chnopf vnd secz da mit ab |

[133r.4] Item Oder durch wechsell mit dem knopff vnd setz Im do mit ab ~ |

[103r.3] It~m der durch wechsel / mit dem knopff vñ seczt da mit ab / |

[259v.3] Item oder dürchwechsel mit dem knopff vnnd setz damit ab |

[62r.3] Item oder durchwechsel mit de[m] knopf, vnnd setz damit ab. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

[32] Or if he has turned the hand around on the blade then stab him above in the fingers, and lift out upward. |

[89v.5] Item ob er die hant hat vmb gewant auf der klingen so stich in oben in die finger vnd heb vber sich auf ~ |

[60v.3] Item ab er die hanthab vmb gewant auf der clingen stich Im oben In die vinger ubersich auff |

|

[133r.5] Item Ob er die hant hatt vmb gewantt auff des clingen / stich ym oben In die finger vbersich auff ~ |

[103r.4] It~m ob er dye hant hat vmb gewant auff der klinge~ so stich In obe~ in dye finger vnd heb vber sich auff / |

[277r.1] Widers ansetzn Ob er die hannt hat umb gewennt, auf der clingen, so stich in oben in die finger, und heb ÿbersich auf. |

[259v.4] Item ob er die hanndthab Vmb gewandt aůf der klinngen stich In oben Inn die finnger vbersich aůf |

[62r.4] Item ob er die handt hat vmbgewentt auf der klingenn, stich in obenn in die finger vbersich auff. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

[33] Note, yet a counter against the attack: Stab him below through his hand, and over his sword, and send the pommel over his left hand and pull down with it, and attack. |

[89v.6] Item aber ein pruch wider das an setzen stich ÿm vnden durch sein hant vnd vber sein swert vñ er pür den knopf vber sein lincke hant vñ ruck do mit nider vñ setz an |

[60v.4] Ein pruch wider die ansetzung Item wider das ansetzen Stich Im vnden durch sein hant vnde [61r.1] über sein swert vnd slag den knauf über sein lincke hant vnd rucke damit nider vnd setze Im an. |

[125v.12] aber ein pruch wider das annseczenn Stich vndenn durch sein hannt vnd vber sein swert Enpur dein hannd chnopf vber sein tencke hannt vnd ruck domit nyder vnnd secz ann |

[133r.6] Ein bruch wider die ansetzüng Item wider daß an setzenn Stich Im vntten durch sint hant vnd vber sin swertt vnd schlag den knauff vber sin lincke hant vnd druck do mit nider vnd setz Im ann ~ |

[103r.5] It~m aber ein pruch wider das an seczen stich Im vnden dürch sein handt vñ vber sein swerdt vñ erpuer den knopff vber sein linke handt vñ ruck da mit Inder vñ secz Im an / |

[260r.1] Ein prüch wider Die ansetzůnng Item wider das ansetzen stich Im vnnden důrch seinn hannd vnnd vber sein schwert vnnd schlag den knopf vber seinn linncke hand vnnd ruckh damit nider vnd setz Im an |

[62r.5] Ein bruch wider die annsetzung. Item wider das ansetzenn stich im vntenn durch sein hant, vnnd vber sein schwert, vnd schlag de[n] knauff vber sein lincke handt, vnnd Ruck damit nider vnnd setz im an. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

[34] Note: When one will drive the pommel over your right shoulder and around the neck, then grab his elbow with the left hand, and thrust him from yourself, and stab strongly with the right hand. |

[89v.7] Item wenn dir ein° wil mit dem knopf vmb den hals varñ vber dein rechte achsel So begreif im den elpogen mit der lincken hant vnd stos in von dir vnd stich mit der lin rechtñ hant krefftigklich ~ |

[61r.2] Item wenn dir einer wil mit dem knauff vmb den hals farn über sein recht achseln So begreiffe Im den elnpogen mit deiner lincken hant vnd stos In von dir vnd stich mit der rechten hant krefftiglichen hinden zu. |

[133r.7] Item wen dir eÿner mit dem knaüff vnder den hals faren vber din rechte achsell So begriff Im den elnbogen mit diner lincken hant vnd stos In von dir vnd stich mit der rechten hantt krefftliglichenn hinden zu ~ |

[103r.6] It~m wen dier einer wil mit dem knopff vmb den halsß faren vber dein rechte achssel so pegreyff Im den elpogñ mit deiner lincken handt vñ stoß In fon dier vñ stich mit der rechtñ handt krefftichklich hindñ züe |

[260r.2] Item wann dir Ainner mit dem knopff will vmb den hals faren vber seinn rechten Achsel so bergreiff Im den Elnpogen mit deinner linncken hannd vnnd stoß In vonn dir vnnd stich mit der rechten hannd krefftigclichen hinnden zů |

[62r.6] Item wenn dir einer wil mit dem knopf vmb denn hals farn, vber sein Rechte achselnn, so begreif im denn Elnpogenn mit deiner linckenn handt, vnd stoß i[n] vonn dir, vnnd stich mit der Rechtenn hanndt kreftiglichenn hindenn tzu. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

[35] Note: Or grab his right with the right hand, and take his weight with the left on his elbow. |

[89v.8] Item oder begreif mit der rechten hant sein rechte vnd mit der lincken nÿm im das gewicht peÿ seinem elpogen ~ |

[61r.3] Oder begreiff mit der rechten hant sein rechte vnd mit der lincken nÿm das gewicht pej seinem elnpogen. |

[133v.1] Item Oder begriff mit der rechten hant vnd mit der lincken nÿm dz gewicht bÿ seynem enlbogenn ~ |

[103r.7] It~m oder pegriff mit der rechtñ handt sein rechte vnd mit der linckeñ nim ym das gewicht pey seine~ elpogñ |

[260r.3] oder begreiff mit der rechten hannd seinn rechte vnnd mit der linncken Nimb das gewicht beÿ seinnen Elenpogen |

[62r.7] Oder begreif mit der Rechtenn handt sein Rechte, vnnd mit der linc[k]enn nim das gewicht, bey seinem Elnpogenn. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

[36] Note: Pull him to yourself with the right hand, and grasp his body and take the side, and lift him, and strike him below from the foot so he falls, this is good too. |

[89v.9] Item ruck in zw dir mit sein° rechten hant vnd begreif ym den leip vnd gewinn ym die seitt an vnd erheb ÿm vnd slach ÿm vnden aus den fües so felt er daz ist auch gut |

[61r.4] Item ruck In zu dir mit seiner rechten hant vnd begreiff Im den leip vnd [61v.1] gewÿnne Im die seitten an vnd erhebe In vnd slag Im vntten auß den fus So felt er das ist gut |

[133v.2] Nota Item Rück in zü dir mit sÿner rechten hantt vnd begriff im den lÿp vnd gewind im die syten an vnd erheb Im vnd schlag im vnden auß sin fuß so felt er dz ist gutt |

[103r.8] It~m Ruck In zü der mit seiner rechtñ handt vnd begreyff Im den leyb vnd gebin Im die seytñ an vnd erheb In vnd schlach im vndñ auß den fueß so felt er vñ das ist güett / |

[260v.1] Item ruckh Inn zu dir Mit seinner rechten hannd vnnd begreiff Im den Leÿb vnnd gewinn Im die seitten an vnnd erheb In vnnd schlag Im vnnden aůß den fůoß so fellt er das ist gůt |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[37] Note: When he stabs then stab at the same time as him to his left side, and clasp his sword to your sword with your left hand, and twist the right hand down through his sword, and then strike him with both swords. |

[90r.1] Item wenn er sticht so stich mit ÿm geleich ein zu° seiner lincken seitten vnd begreif sein swert zw deine~ swert mit deiner lincken hant vnd mit der rechten hant wind vnden durch sein swert vnd slach In denn mit paiden swerten ~ |

[61v.2] Item wenn er sticht So stich mit Im gleich zu seiner lincken seiten vnd begreiff sein swert zu deinem swert mit der lincken hant vnd mit der rechten hant wind vnden durch sein swert vnd slag denn mit beiden swertten etc. |

[133v.3] Item wan er sticht so stich mit Im glich zu siner lincken syten vnd begriff syn swertt zu dinem swertt mit der lincken hant vnd mit der rechten var vntten durch sin swertt vnd schlag dan mit beÿden swertternn ~ |

[103r.9] It~m Wen er sticht so stich mit im gleich ein zü seiner linckñ seytñ vnd pegreyff sein swert zu deine~z swert mit deine~r swert linckñ handt mit der rech[tñ?] handt windt vnde~ durch sein swert so schlag in dan mit paydñ swerten |

[260v.2] Item wann er sticht so stich Mit Im gleich zů seiner Linncken seitten vnnd begreiff sein schwert zů deinnem schwert mit der linncken hannd vnnd mit der rechten hannd winnd vnden durch seinn schwert vnnd schlag den mit baiden schwertern |

[62v.2] Item wenn er sticht, so stich mit Im gleich tzu seiner linckenn seittenn, vnnd begreif sein schwert tzu deinem schwert, mit der linckenn hanndt, vnnd mit der Rechtenn handt windt vntenn durch sein schwert, vnnd schlag dann mitt beidenn schwerttenn. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

[38] Note: When one has attacked you, and you also to him, then this will counter near him as in forcing with the side to which he has attacked you, and grasp forward with your left hand to his sword by the point, and force him back to you, thus you take his side. |

[90r.2] Item wenn dir ein° hat an gesetzt vnd dw Im auch das prich also nahen ÿm als mit eine~ dringen mit der seitten an die er dir hat gesetzt vnd greif mit dein° lincken hant vorñ an sein swert pey dem ort vnd vrbering ruck in nach dir so gewingstu ÿm die seitt an ~ |