|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Paulus Hector Mair

| Paulus Hector Mair | |

|---|---|

"Mair", Cod.icon. 312b f 64r | |

| Born | 1517 Augsburg, Germany |

| Died | 10 Dec 1579 (age 62) Augsburg, Germany |

| Occupation |

|

| Movement |

|

| Influences | |

| Genres | |

| Language | |

| Manuscript(s) |

Cod. 10825/10826 (1540s)

|

| First printed english edition |

Knight and Hunt, 2008 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

| Signature | |

Paulus Hector Mair (Paulsen Hektor Mayr, Paulus Hector Meyer; 1517 – 1579) was a 16th century German aristocrat, civil servant, and fencer. He was born in 1517 to a wealthy and influential Augsburg patrician family. In his youth, he likely received training in fencing and grappling from the masters of Augsburg fencing guild, and early on developed a deep fascination with fencing treatises. He began his civil service as a secretary to the Augsburg City Council; by 1541, Mair was the city treasurer, and in 1545 he also took on the office of Master of Rations.

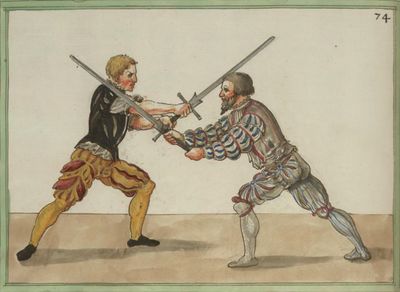

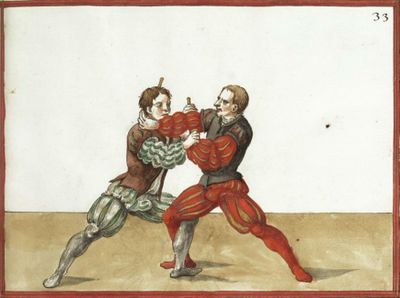

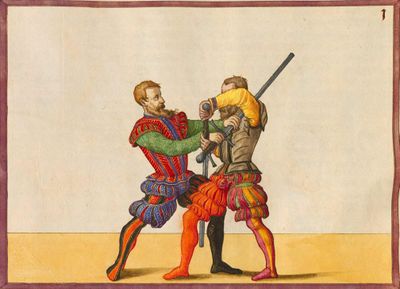

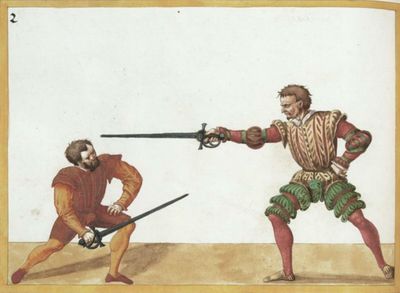

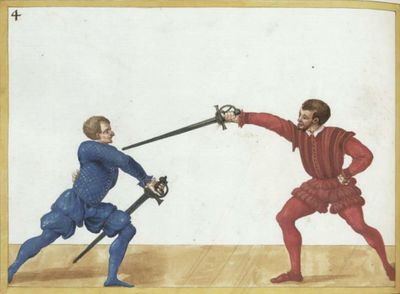

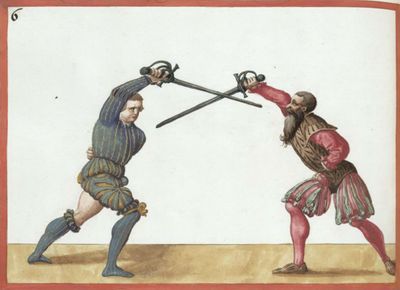

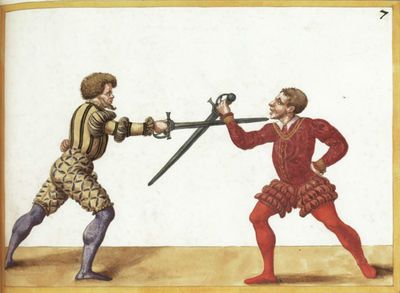

Mair's martial background is unknown, but as a citizen of a free city he would have had military obligations whenever the city went to war, and as a member of a patrician family he likely served in the cavalry. He was also an avid collector of fencing treatises and other literature on military history. Like his contemporary Joachim Meyer, Mair believed that the Medieval martial arts were being forgotten, and he saw this as a tragedy, idealizing the arts of fencing as a civilizing and character-building influence on men. Where Meyer sought to update the traditional fencing systems and apply them to contemporary weapons of war and defense, Mair was more interested in preserving historical teachings intact. Thus, some time in the latter part of the 1540s he commissioned what would become the most extensive compendium of German fencing treatises ever made, a massive two-volume manuscript compiling virtually every fencing treatise he could access. He retained Jörg Breu the Younger to create the illustrations for the text,[1] and hired two Augsburg fencers to pose for the illustrations.[2] This project was extraordinarily expensive and took at least four years to complete. Ultimately, three copies of this compendium were produced, each more extensive than the last; the first (MSS Dresden C.93/C.94) was written in Early New High German, the second and most artistically ambitious (Cod.icon. 393) in New Latin, and the rougher third version (Cod. 10825/10826) incorporated both languages.

Beginning in the 1540s, Mair began purchasing older fencing manuscripts, some from fellow collector Lienhart Sollinger (a Freifechter who lived in Augsburg for many years) and others from auctions. Perhaps most significant of all of his acquisitions was the partially-completed treatise of Antonius Rast, a Master of the Long Sword and three-time Captain of the Marxbrüder fencing guild. The venerable master left it incomplete when he died in 1549, and in 1553 Mair produced a complete fencing manual (Reichsstadt "Schätze" Nr. 82) based on his notes. Ultimately, he owned over a dozen fencing manuscripts over the course of his life, including the following:

- Codex I.6.2º.1 - A copy of one of Hans Talhoffer's fencing manuals, possibly the MS XIX.17-3.

- Codex I.6.2º.2 - A compilation of Jörg Wilhalm's longsword treatise and Lienhart Sollinger's manuscript reproduction of Ergrundung Ritterlicher Kunst der Fechterey.

- Codex I.6.2º.3 - A copy of Codex I.6.4º.5 with descriptive text by Hutter.

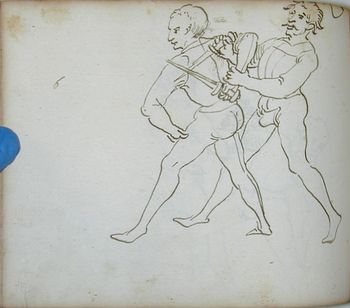

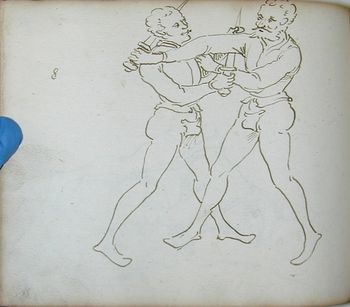

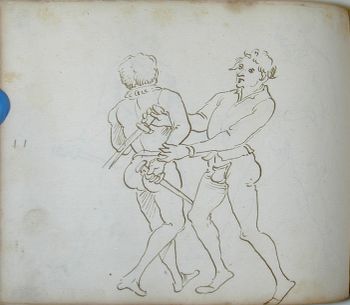

- Codex I.6.2º.4 - Jörg Breu's draftbook for his work on Mair's treatises.

- Codex I.6.2º.5 - A compilation of records of the Marxbrüder fencing guild, Hans Medel's gloss of Liechtenauer's Recital, Medel's additional teachings, and fencing prints by Maarten van Heemskerck.

- Codex I.6.4º.2 - A compilation of two treatises from the Nuremberg Group and a much older, uncaptioned series of fencing drawings known as pseudo-Gladiatoria.

- Codex I.6.4º.5 - Jörg Wilhalm's draftbook.

- MS E.1939.65.354 - Gregor Erhart's fencing manual. (Formerly Codex I.6.4º.4.)

- Reichsstadt "Schätze" Nr. 82 - The expanded and finished version of Antonius Rast's fencing notes.

He also used several printed books as source material for his compendia, and presumably owned copies, including Der Allten Fechter gründtliche Kunst (printed by Christian Egenolff), Opera Nova by Achille Marozzo, and Ringer Kunst by Fabian von Auerswald.

Mair not only spent incredible sums of money on his fencing interests, but generally lead a lavish lifestyle and maintained his political influence with expensive parties and other entertainments for the burghers and patricians of Augsburg. This habit of living far beyond his means for decades exhausted his family's wealth, eventually leading him to sell the Latin version of his fencing manuscript (netting the princely sum of 800 florins) and finally to begin embezzling money from the Augsburg city coffers. This embezzlement was not discovered for many years (or perhaps was overlooked due to the favor his parties garnered), until finally in 1579 a disgruntled assistant reported him to the Augsburg City Council and provoked an audit of his books. Mair was arrested, tried, and hanged as a thief at the age of 62. After Mair's death, his effects (including his library) were sold at auction to recoup some of the funds he had embezzled.

Whether viewed as an unwise scholar who paid the ultimate price for his art or an ignoble thief who violated his city's trust, Mair remains one of the most influential figures in the history of Kunst des Fechtens. By completing the fencing manual of Antonius Rast, Mair gave us valuable insight into the Nuremberg fencing tradition; his own works are impressive on both an artistic and practical level, and his extensive commentary on the fencing illustrations in his collection serves to make potentially useful training aids out of what would otherwise be mere curiosities. Finally, in purchasing so many important fencing treatises he succeeded in preserving them for future generations; they were purchased by the fabulously wealthy Fugger family after his death and ultimately passed to the Augsburg University Library, where they remain to this day.

Contents

- 1 Treatise

- 1.1 Preface

- 1.2 Contents

- 1.3 Long Sword

- 1.4 Dussack

- 1.5 Staff

- 1.6 Lance/Pike

- 1.7 Halberd

- 1.8 Scythe

- 1.9 Flail

- 1.10 Peasant Stick

- 1.11 Mixed Weapons I

- 1.12 Sickle

- 1.13 Dagger

- 1.14 Grappling

- 1.15 Mixed Weapons II

- 1.16 Rapier

- 1.17 Poleaxe

- 1.18 Sword, Speard, and Longshield

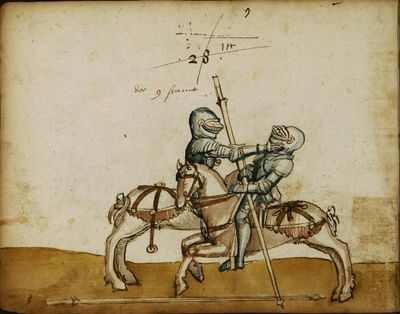

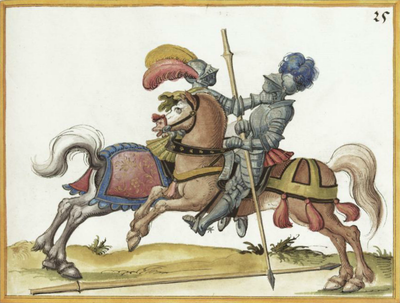

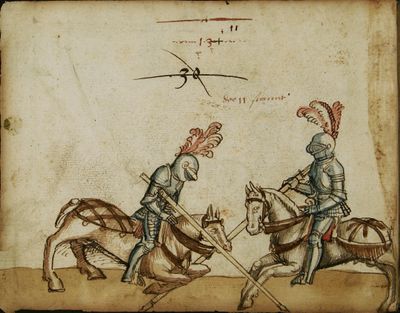

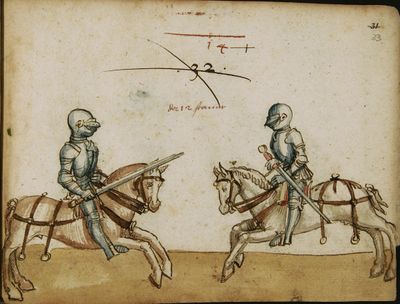

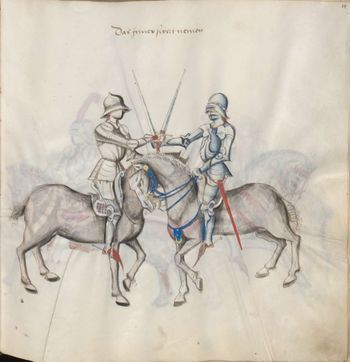

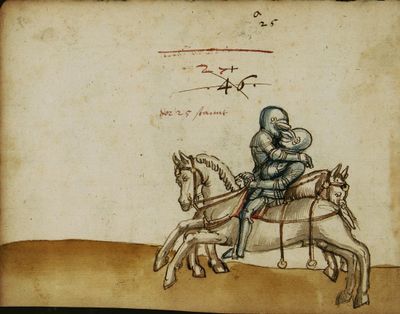

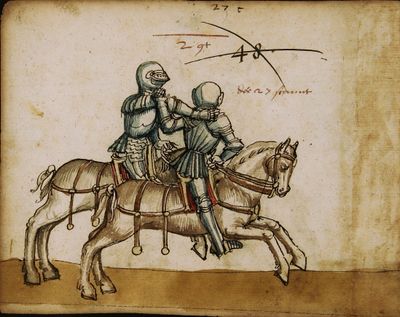

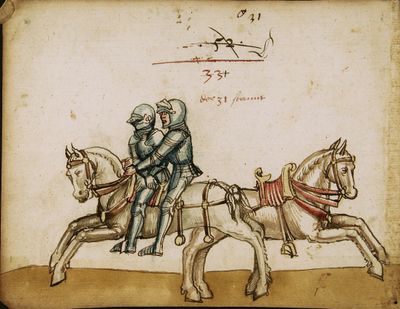

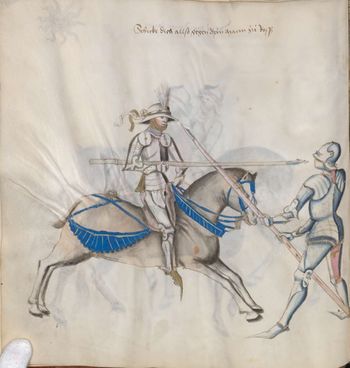

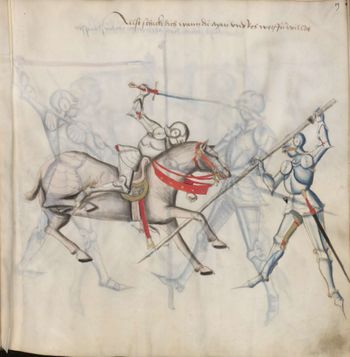

- 1.19 Mounted Fencing

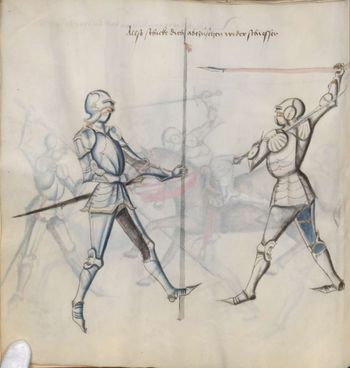

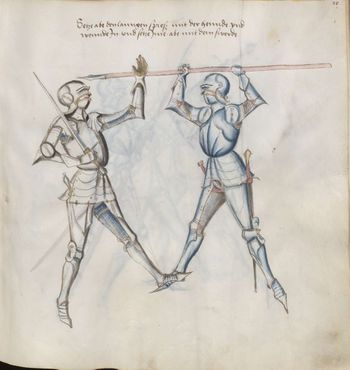

- 1.20 Armored Fencing

- 1.21 Conclusion

- 1.22 Copyright and License Summary

- 2 Additional Resources

- 3 References

Treatise

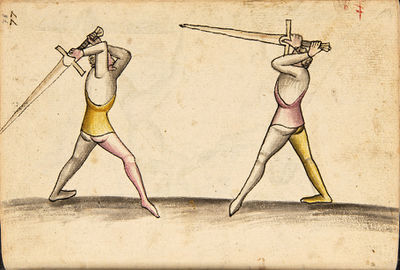

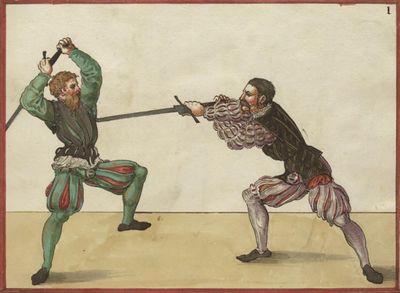

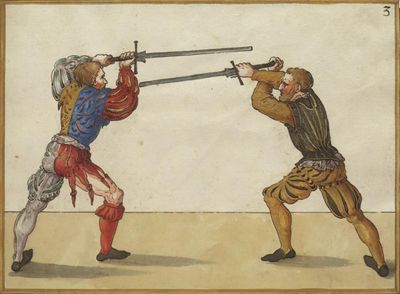

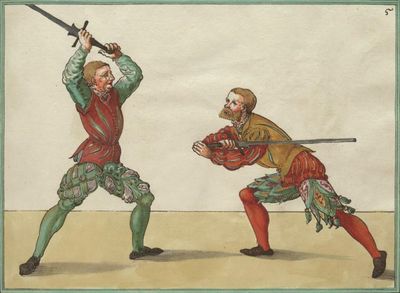

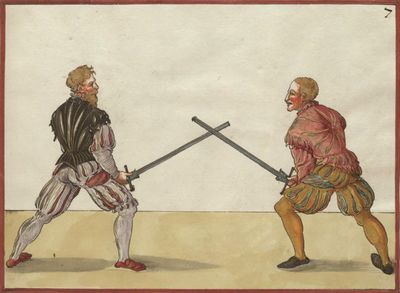

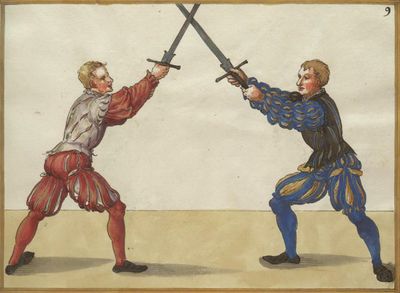

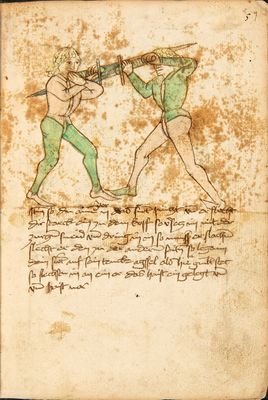

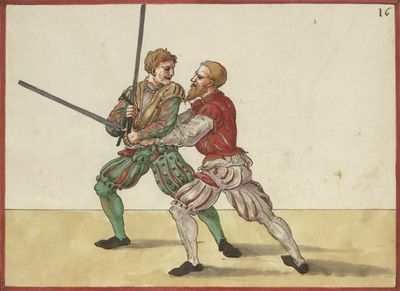

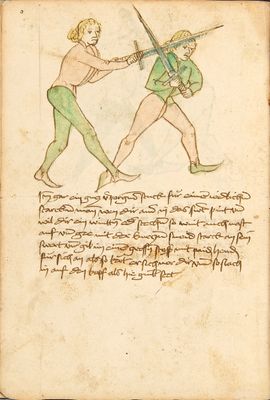

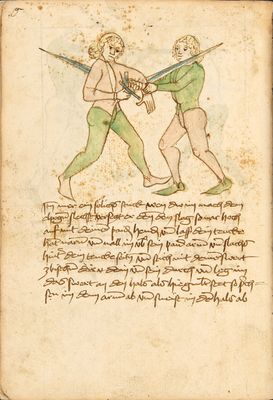

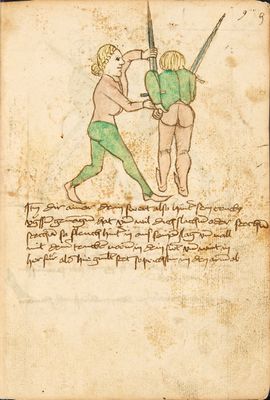

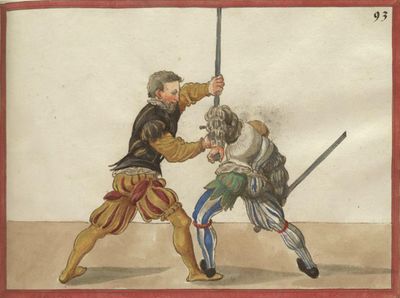

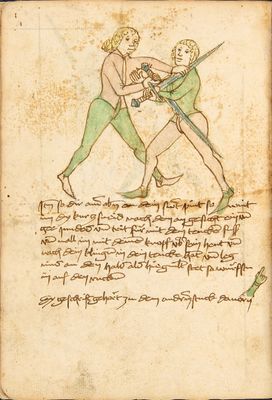

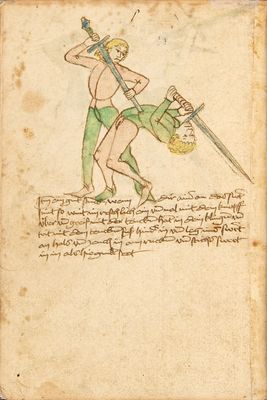

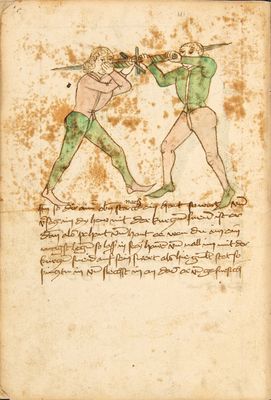

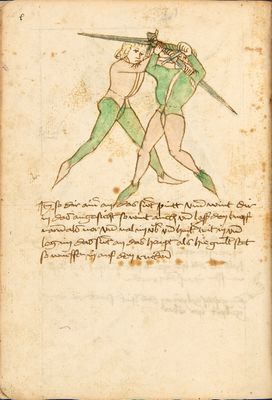

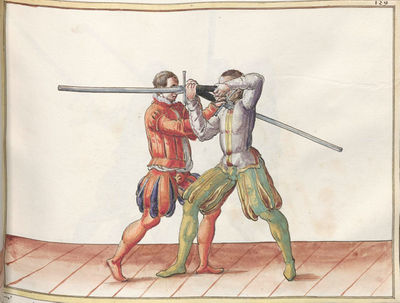

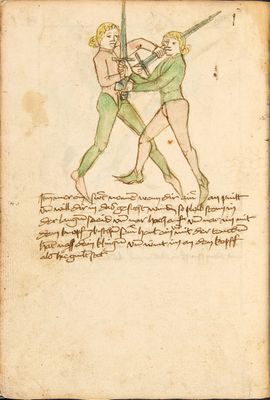

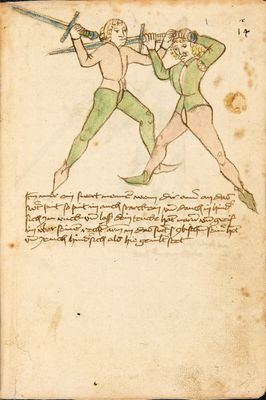

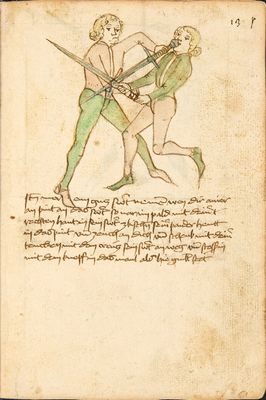

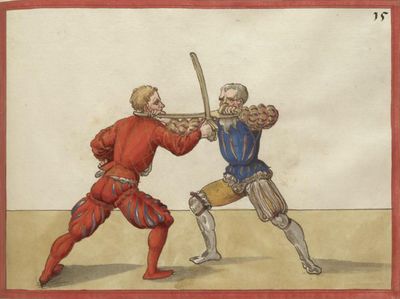

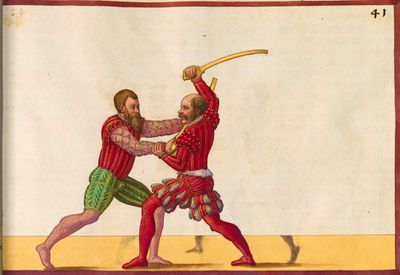

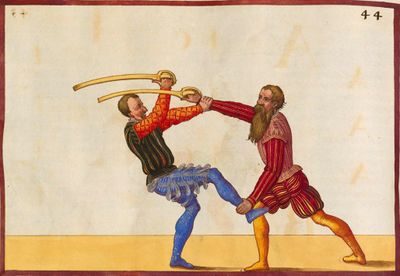

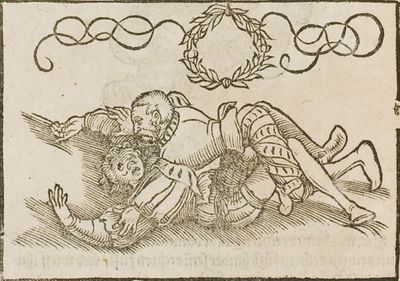

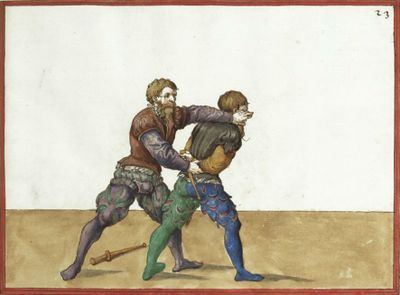

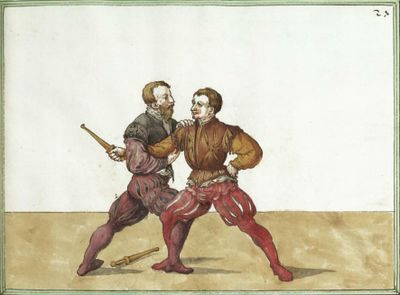

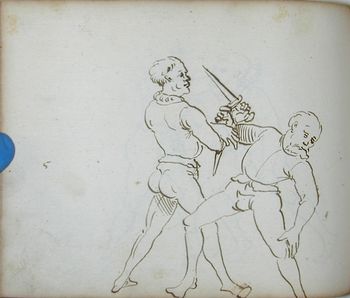

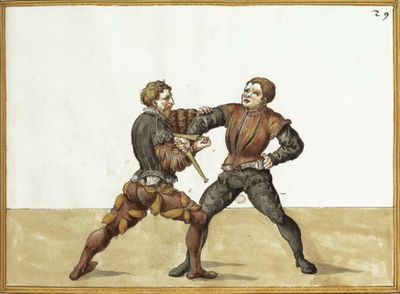

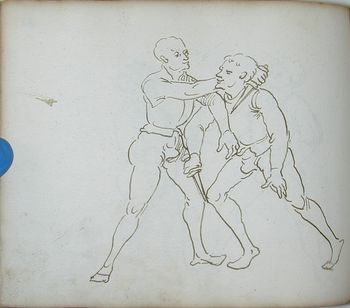

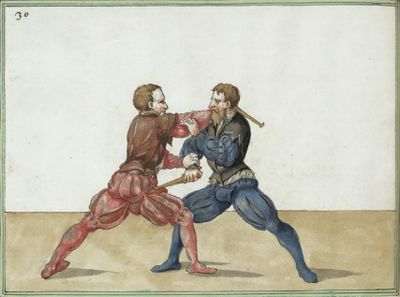

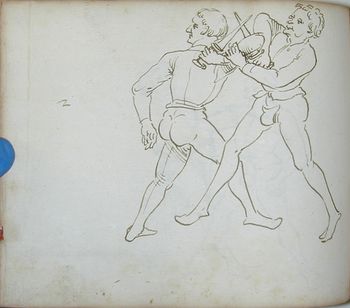

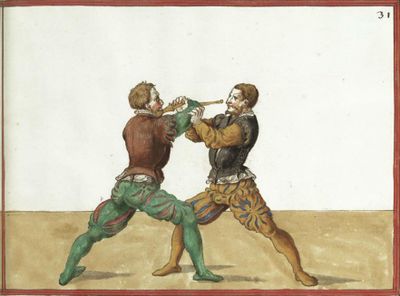

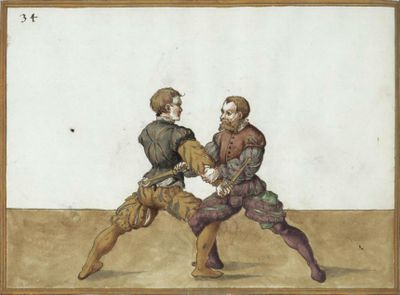

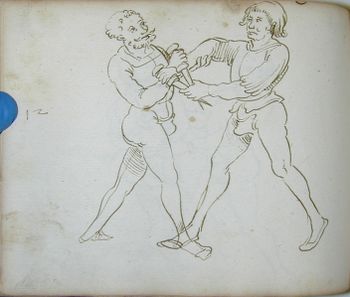

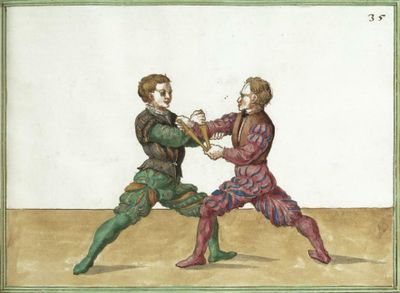

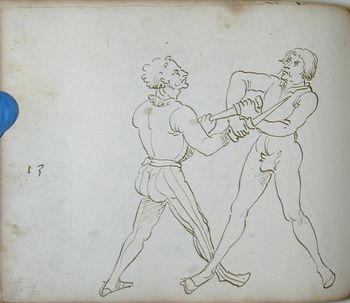

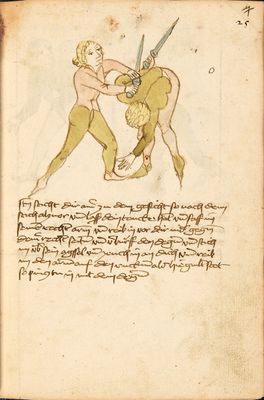

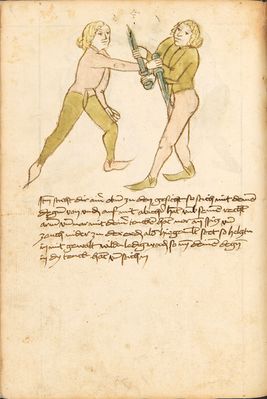

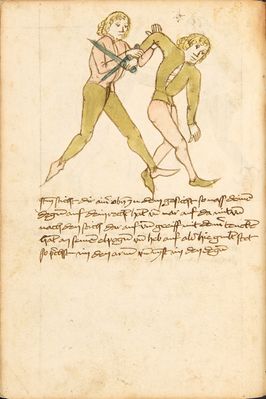

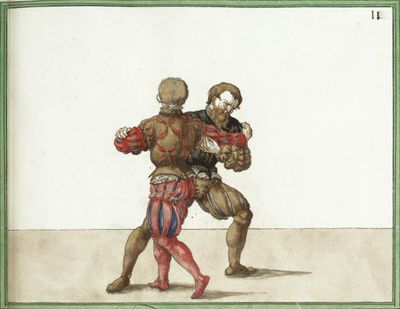

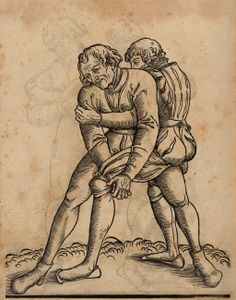

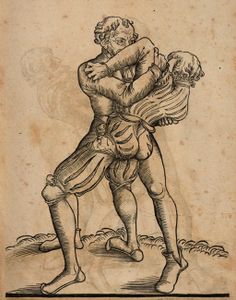

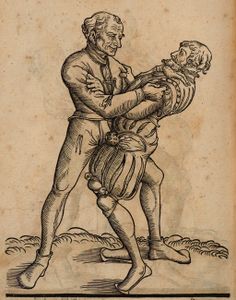

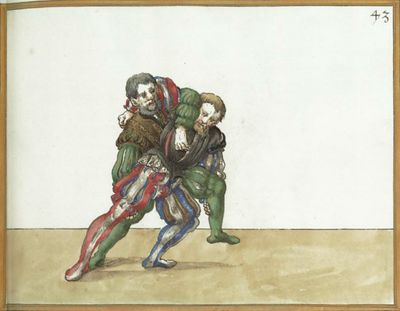

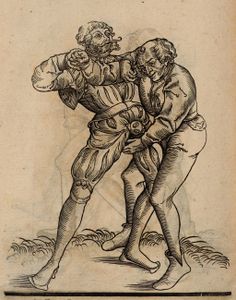

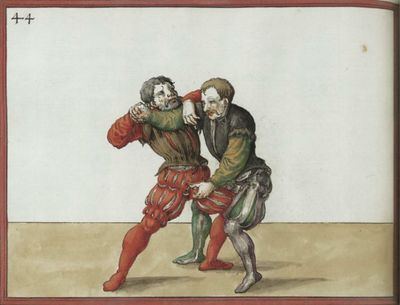

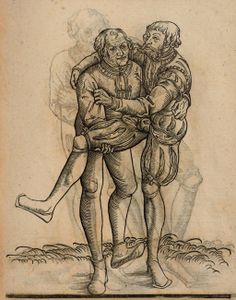

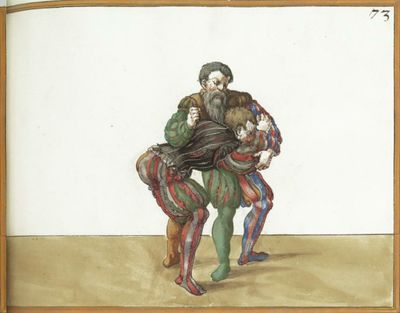

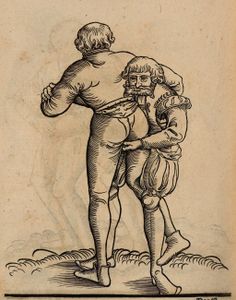

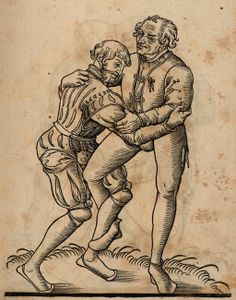

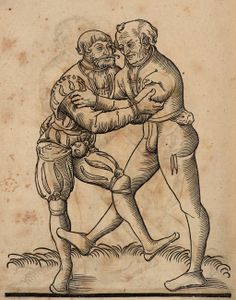

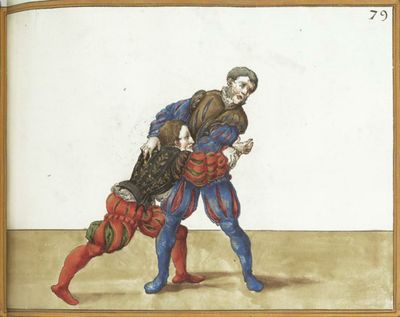

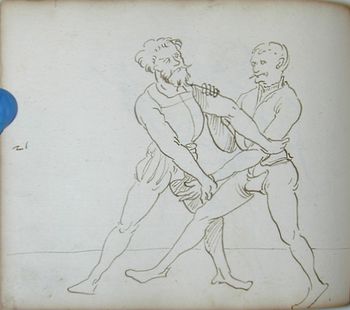

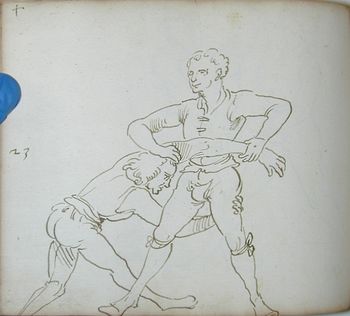

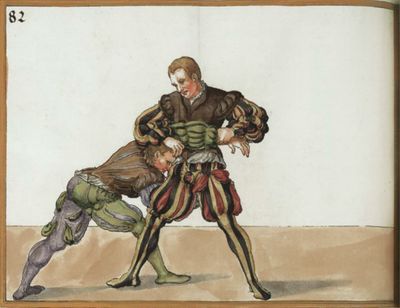

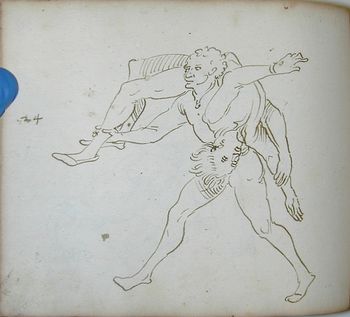

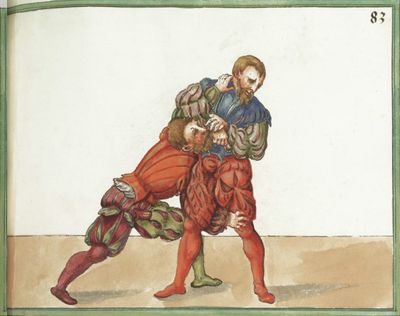

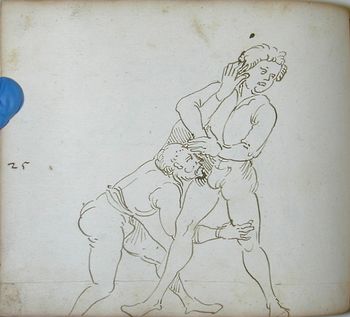

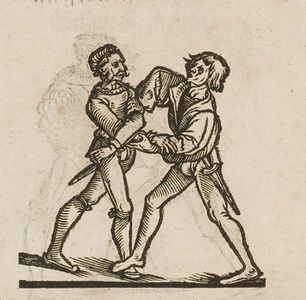

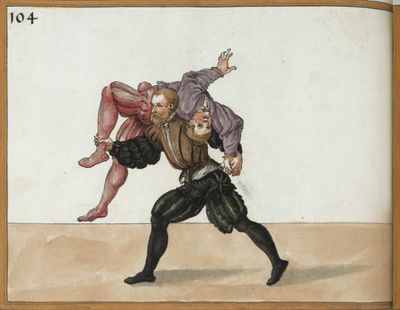

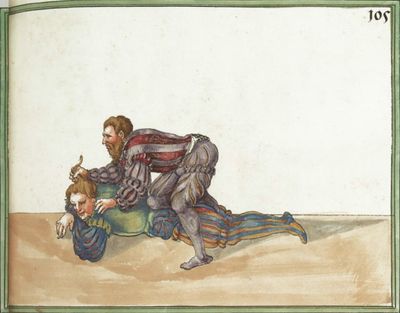

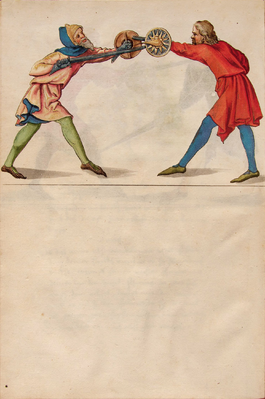

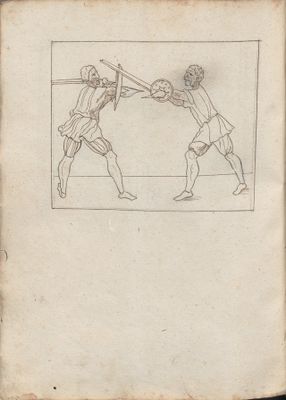

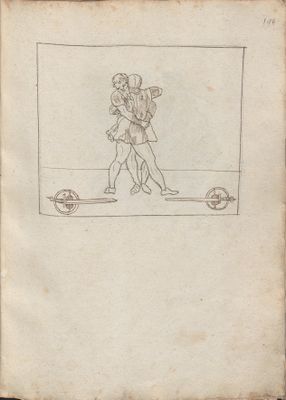

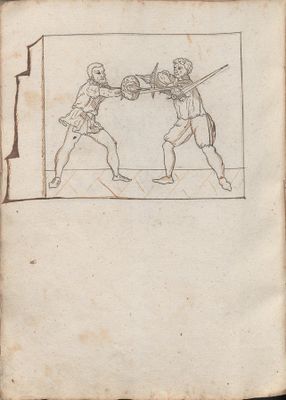

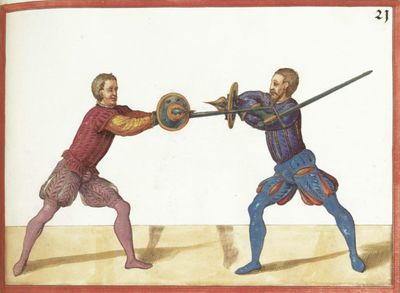

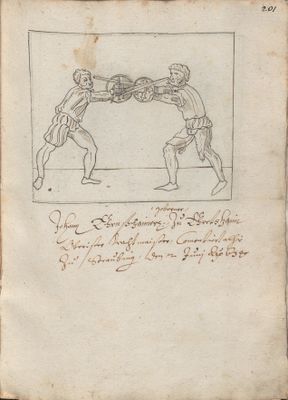

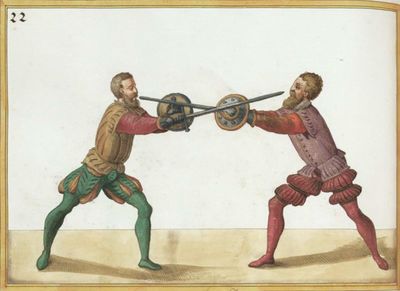

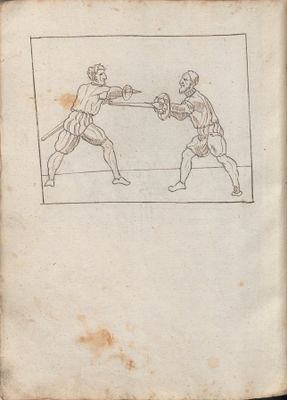

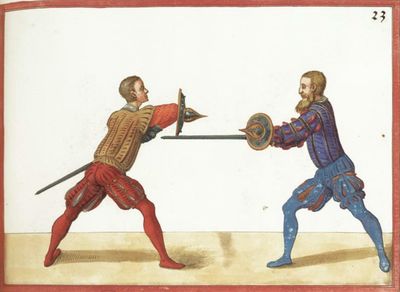

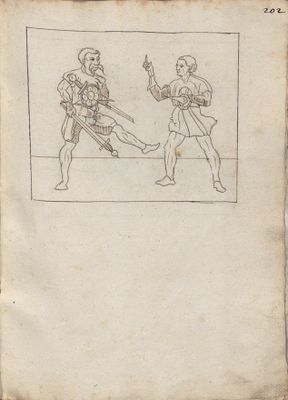

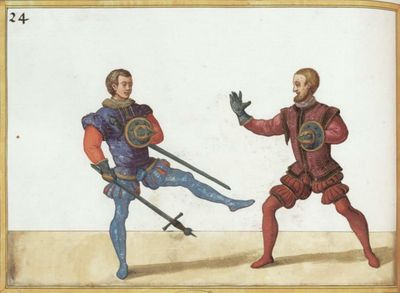

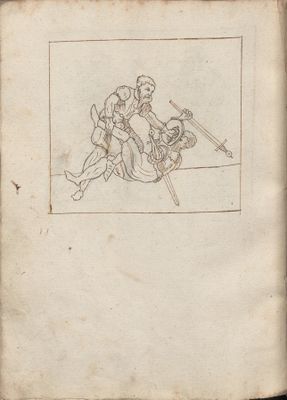

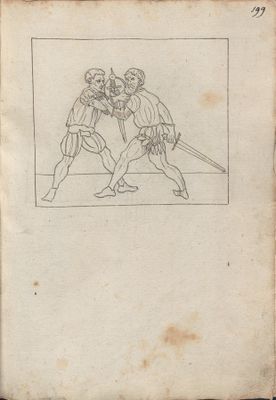

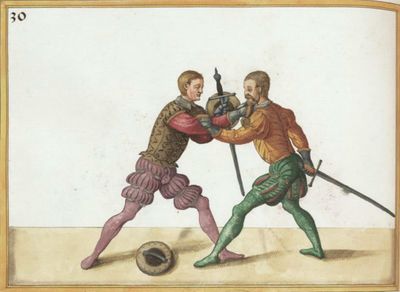

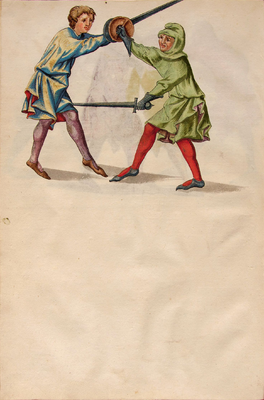

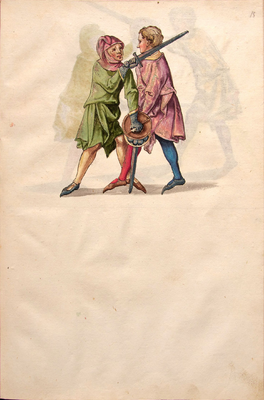

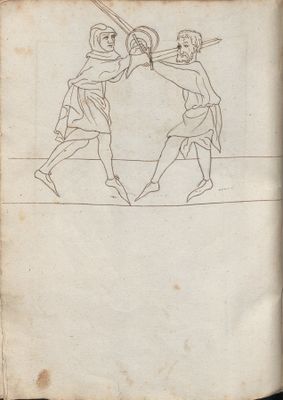

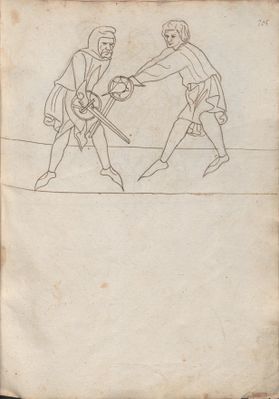

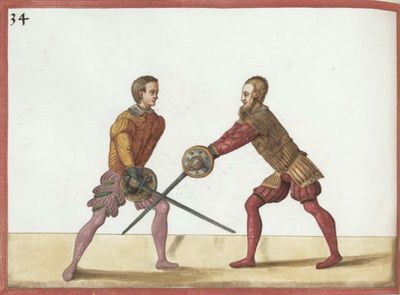

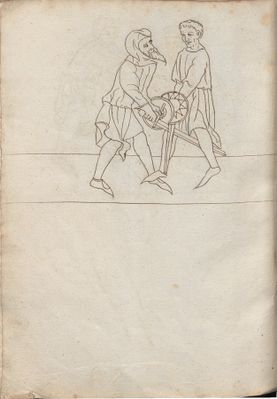

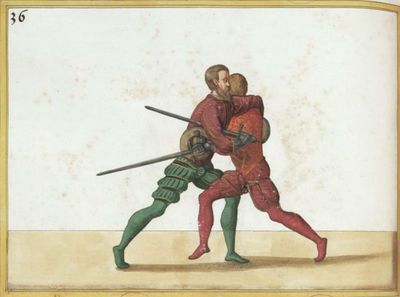

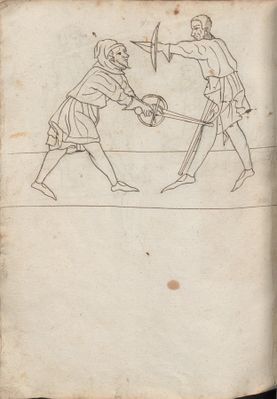

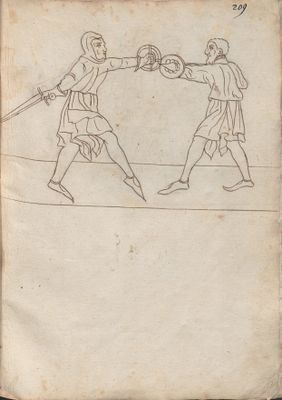

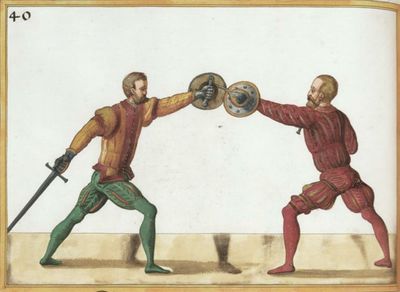

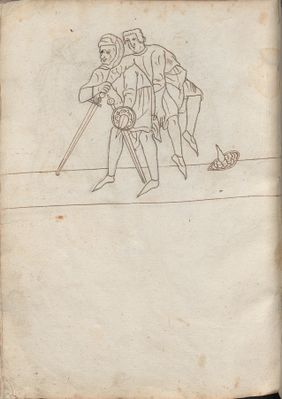

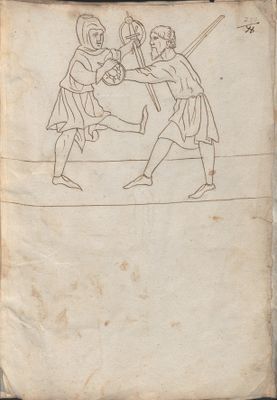

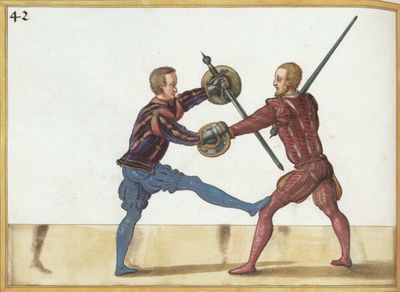

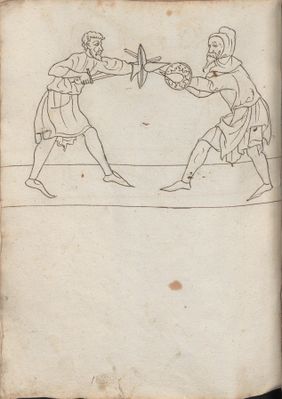

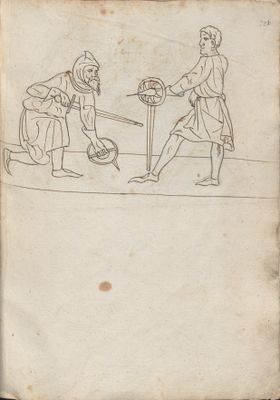

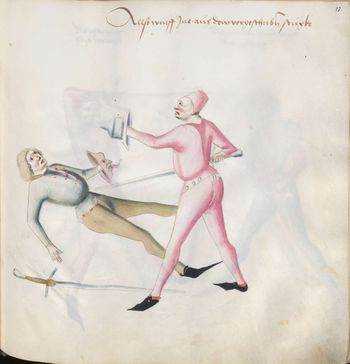

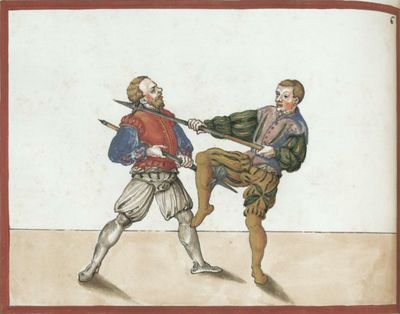

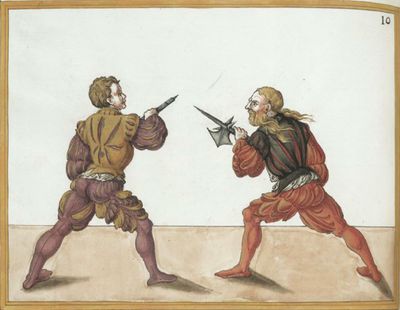

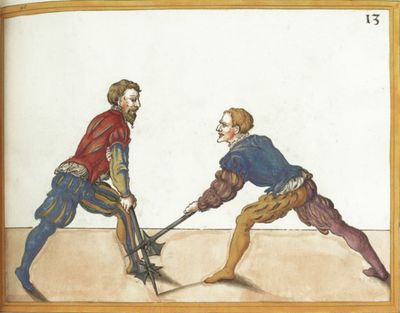

Much of Mair's content represents his revision and expansion of the older treatises listed above, including adding descriptive content to uncaptioned illustrations. Where available, these illustrations are displayed in the left-most column, labeled "Source Illustrations", for comparison purposes. Mair's own illustrations appear in the second column, alongside the translation.

The Dresden version contains the fewest devices and artwork most reminiscent of Breu's style, and appears therefore to be the original copy. The Munich adds additional plays and sections on top of the Dresden's contents, and the Vienna likewise augments the Munich, suggesting that this is likely order of creation; conversely, the Dresden has no unique content, and the only unique plays in the Munich are in the section on jousting. To give a visual sense of this evolution of the work, the Dresden illustrations are used wherever possible; the Munich illustrations appear only in those plays that are omitted from the Dresden, and the Vienna in those that are unique to that work.

Source Illustrations |

Illustrations |

Dresden Ⅰ Version (1540s) |

Vienna Ⅰ Version [German] (1550s) |

Munich Ⅰ Version (1540s) |

Vienna Ⅰ Version [Latin] (1550s) |

Draftbook Version (1540s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The First Part of the Fechtbuch |

[001r] Der Erst Tail diß Fechtbuch |

[005*r] Vorred in das Fechtbuch. |

[001r] In hoc libro continentur artis athleticae non solum habitus selectissimi atque approbatissimi verum etiam vitandi et inferendi ictus subtilior quedam ratio, et scientia quibus si quis rite usus fuerit, facile in palestra, equestri concursu, et torneamentis victoriam obtinebit. Tum etiam complectitur figuras gladiatorum concertantium exornatissimas declarationibus habituum adiunctis. Addita item sunt torneamenta ante annos quingentos in Germania exercita isti itaque habitus a doctoribus gladiatorum peritissimis excogitati et accersiti per Paulum Hectorem Mair civem Augustanum non citra magnus labores et sumptus in honorem principum heroum atque artis gladiatoriae amantium nunc demum in lucem editi sunt. |

||||

|

Preface It would only be right and proper, and I would have thought it good and advisable, for me to publish this knightly book of honour without any preface, as to the knowledgeable each art can with good reason defend and speak for itself. But as I become aware and notice, that this manly art of fencing, as other arts besides, which profit the beloved fatherland as useful and honourable, and by the learned are praised for men to study, are by those who out of idleness and neglect fail to respect the good virtues and arts, and those that do neither love nor feel inclination to learn, not just failing to support, but the same that from an ignorant, impertinent and lazy carelessness use disdainful words of mockery to besmirch them (as I during the long time during which I have compiled this work of honour, myself had to experience, and such things did often have to hear to my vexation). Therefore, moved and instigated against my will that I would order and place here a little preface and apology of the noble knightly art of fencing, to all beloved honourable men, be they of noble birth or otherwise. To this end I would not look on the cost, just as I did not with the other work and zeal that I put into this work, with unwavering hope that this preface would succeed to serve as good and comprehensible instruction for the reader. |

[002r] Vorred Es were wol recht vnnd billich Vnnd hette mich auch fur guet vnnd Ratsam angesehen · Das ich dises Ritterlich Eernbuch · dieweil sich Jede kunst · beÿ allen verstenndigen · mit gutem grund selbs verthedingen vnnd versprechen kan · on alle vorred von mir außgeen lassen · sollte · Dieweil ich aber merckh · sihe vnnd briefe · das dise manliche Kunst des Fechten · wie annder kunsten mer· so dem geliebten Vatterlannd als fur nutzlich vnnd Eerlich · den mentschen durch die gelerten geprisen vnd zulernen furgestellt sein· von den Ihenigen · so auß faulkait vnnd hinlessigkait · der guten tugenden vnnd kunsten nicht achten · auch dieselben zulernen kain liebe noch naigung nicht allain nit tragen · sonder dieselben vil mer auß vnwissender frechen faulen leichtuertigkait · mit verachtlichen schmachworten · besudlen vnnd belegen ( · wie ich dann die lannge zeit · als ich dises Eernnwerckh zusamen geordnet · selbs erfaren · vnnd solches offtermalen mit verdruß hab hören muessen · ) Derhalben ich wider meinnen willen verursacht vnnd bewegt worden · das ich der Edlen Ritterlichen kunst des Fechtens vnnd allen geliebten Eerlichen vom Adel vnnd sunst · so sich der manlichen Kunst · dem Eerliebenden Vatterlannd zu Eern · nutz vnnd wolfart gebrauchen · ein klaine Vorred vnnd verthedigung vorher hab setzen vnnd ordnen wellen Daran mich auch neben annderer muhe vnnd arbait · so ich auf dises werckh gelegt · der vncost gar nicht betauren soll ungezweifleter hoffnung · das dise Vorrede dem leser zu gutem verstenndigem bericht raichen vnnd gedeichen werde / · |

[006*r] Vorred. Es were nur recht und billich, und hette mich auch für gut und ratsam angesehsen, Das Ich dises ritterliche Eerenbuch, Dieweil sich jede kunst bey allen verstendigen, mit gutem grundt selbst vertheidigen und versprechen kan, on alle vorred, von mir aussgeen lassen solte. Dieweil ich aber merck, sihe und briefe, das dise manliche kunst des fechten, wie ander künsten mer, so dem geliebten vatterland, als für nutzliche und eerliche, den menschen durch die gelerten geprisen, und zu lernen furgestalt sein, von denjhenigen, so aus faulkait und hinlessigkait, der gutten tugenden und kunsten nicht achten, auch dieselben zu lernen kain liebe noch naigung, nicht allain nit tragen, sondern dieselben vilmer aus unwissender frechen, faulen leichtvertigkait, mit verachtlichen schmachworten, besudeln, und belegen (wie ich dann die lange zeit, als ich dises Eerenwerck zusamen geordnet, selbst erfahren, und solches offtermalen mit verdruss hab horen mussen) Derhalben ich wider meinen willen verursacht und bewegt worden, das ich der Edlen ritterlichen kunst des fechtens, und allen gelibten Eerlichen vom adel und sonst, so sich der manlichen kunst, dem Eerliebenden vatterland zu eeren, nutz und wolfart gebrauchen, ein klaine vorred und vertheidigung vorher hab setzen und ordnen wollen. Daran mich auch neben anderer muse und arbait, so ich auf dises werck gelegt, der unkost gar nicht beschauen soll, Ongezweiffelter hoffnung, das dise vorredt, dem leser zu gutem verstandigen bericht reichen und gedeihen werde. |

[002r] Praefatio in Athleticam Commodum et consultum mihi primum videbatur, hunc librum excellentem artis Athleticae in lucem sine ulla praefatione edere: praesertim cum quolibet artes liberales et honestae seipsas facile remota omni dubitatione defendere, nec non omnibus gratas efficere possint. Cum vero hactenus eo ipso tempore, quo ista omnia haud sine magnus laboris, sudore, atque negotio summa cum diligentia comportavi, eam ipsam Athleticam quae patriam nostram communem ornat potius, quam ut deformet (quam etiam ut discamus multi eruditissimi viri nos exhortantur) ab hominibus temerariis, ignavis, et petulantibus, quibus optime quoque virtutes, et exercitia honesta non curae sunt, contemni atque eam prorsus contaminari animo iam dudum prospexissem, et eorum calumniis ob istis meos prope sysiphos labores provocatus: motus sum tandem invitus ipsorum calumniis respondere, et operi praefationem premittere, in gratiam eorum qui summo amore eam artem prosequuntur ii, sive sint Nobiles, sive alias claris parentibus progeniti, qui communis patriae defendae causa Athleticam discunt, amant atque exercent. Neque vero me laboris neque expensorum penitebit unquam, tametsi mihi magno ista constiterint. Lectori autem multum proderit eam praefationem legisse, praesertim ei, qui Gymnicis certaminibus delectatur. |

[001*r] Prefatio in athleticam |

|||

|

The ancient and modern Greek, Latin and German historians have put much zeal and effort into the question, in numerous points and articles, from which basis and causes, in which time, and in what land and situation, and by whose instigation, the knightly sport of fencing first took its origin and source, but in the cause and the tale of years, or in place and situation, they all are in agreement, that this knightly art of fencing was in the beginning established with the purpose of serving to the honour, virtue and stimulation to the youth of both high and low birth, and also to the protection and preservation of the fatherland. But in the question of naming who was the first inventor of this art, they are found somewhat discordant and of differing opinions. |

Es haben sich die alten vnnd Newen Griechischen / Lateinischen vnnd Deutschen Historici · ob dem Ritterspil des Fechtens · Inn etlichen puncten vnnd Articulen Namlich auß was grund vnnd vrsachen · auch zu welcher zeit · Inn was Lannd vnnd gelegenhait vnd auch durch wen sie anfengcklich Jren vrsprung empfanngen · vnnd hergeflossen seÿe · seer vast bemuehet · aber Inn der vrsach vnnd Jarzal · auch Ort vnnd gelegenhait sie alle vast vberain stimmendt · vnnd zugleich bekennen Das dise Ritterliche kunst des Fechtens · der Jugent von hochen vnnd Nidern stennden zu eernzucht vnnd anraitzung guter Mannlicher tugent · auch zu schutz vnnd erhalltung des Vatterlanndts · sampt aller Redlichkait Im anfanng gefundiert auch die zu lernen furgenomen worden seÿ Noch werden sÿ allain Inndem · welcher der erst erfinder diser Kunst zubenennen were · etwas mißhellig vnd vngleicher mainung befunden · |

Es haben sich die alten und neuen Griechischen, Lateinischen und Teutschen historici, ob dem ritterspil des fechtens, in etlichen puncten und articulen, menlich aus mass grund und ursachen, auch zu welcher zeit, in was land und gelegenhait, und auch durch wen, sie anfanglich iren ursprung entpfangen, und hergeflossen sey, seer vast bemuehet, aber in der ursach und jartzal, auch ortt und gelegenhait, sie alle cast uberain stimmend, und zugleich bekommen, das dise ritterliche kunst des fechtens, der jugent von hohen und nidern standen, zu Eeren, zucht und anraitzung gutter manlicher tugend, auch zu schutz und erhaltung des vatterlands, sambt aller redlichkait, im anfang gefundiert, auch die zu lernen fürgenomen worden sey. Noch werden sie allain in dem, welcher der erst erfinder diser kunst zu benennen were ettwas misshellig und ungleicher meinung befunden. |

Porro[3] historici probati ex Graecis, Latinis, atque Theutonicis plerique consentiunt de inventoribus istius artis, nec non origine, et quo tempore ea primum sit inventa, quibusque regionibus fuerit in usu. Atqui affirmant Athleticam in utilitatem iuventutis et omnium virtutum excitationem, tum etiam ad tutandam patriam esse repertam, non solum nobilium, verum etiam eorum qui humili de stirpe nati sunt, attamen in hoc nonnihil dissentire videntur, qui dubitant, qui primus omnium fuerit eius artis author. |

||||

|

And while many of the learned say that this art of the knightly sport, as other arts beside, must have come among men to influence[?] their appetites and pleasure, from above, i.e. from God and celestial influence of the stars, as is well believable. Besides this, some say that Pollux, who was honoured by the Romans, was an instigator of this honourable art; others would attribute the honour of such invention to Mercury. But both these statements must be found somewhat obscure and uninstructive from the fact that they do not explain what use or profit they would have made from this art, or which lords they took as their disciples that would have learned the art from them and in turn passed it on. But the majority of the same historiographers state and testify that Probas, the famous fencer and teacher of Theseus, the king of Athens in Greece, in which realm the knightly art in the beginning and for a long time thereafter did much prosper, was the first inventor and establisher of this art. For this same Probas did to the highest extent praise and commend the knightly exercise to king Theseus with fair and rigorous argument, to the kingdom and fatherland, to all ordered conduct and honesty, and all that serves the preservation of the liberty of the fatherland, as a highly expedient medicine against the useless, inert and recreant slothfulness and other frivolity. Which instruction said king Theseus took to heart and in consideration of that this knightly art and exercise of fencing in times of peace may be an honourable and manly exercise for the young, but in times of distress and danger may serve and succeed towards the fatherland's honour, advantage and prosperity, he put belief in Probas and himself together with some of the most noble of his court, undertook it to learn this knightly art of fencing, to which end Probas was highly assiduous. And thus the honourable art of fencing prospered from the cause that each [practitioner] was found that much more competent and able to support the fatherland in its need. Said king Theseus did build, to considerable cost, many sumptuous houses dedicated for the exercise of this art, in Athens and elsewhere in his realm, which was the beginning of the general [systematic] tuition in fencing. These events under the reign of the Athenian king Theseus, who according to the reckoning of the Urspergian[4] reigned for thirty years, took place and occurred approximately in the year 1224 before the birth of our saviour Jesus Christ, and from this circumstance it follows that this art, which has been founded by kings, and by many of royal and noble kin and blood besides, which served to themselves as a noble exercise and towards honour, advantage and necessity for the fatherland, may well and truly be called a noble and knightly sport. But what zeal and considerable cost was invested by the ancients in the knightly art of fencing, and in what earnest and honourable reputation its exercise was held, furthermore what high persons undertook to learn this art, and to what good consequence this art served in all lands and kingdoms, this I will also tell and describe. |

[002v] Vnnd wiewol etlich der Gelerten sagen das dise kunst des Ritterspils · wie annder kunsten mer Inn die mentschen zu kumen · seinen einflus · begird vnd lust · von oben herab · das ist von gott vnnd Himlischer Influentz · des Gestirens haben mueß · welchs dann auch wol zu glauben Hieneben sagen ainstails das Polux · welchen die Römer geeret haben · ein anfenger diser Eerlichen kunst gewesen seÿ · Anndere wo°llen solche erfindung vnnd Eher dem Mercurio zu aignen · Es werden aber baider anzaigung · auß der vrsach das nicht befunden wirt · was nutz vnd frucht sie Inn diser kunst geschafft · auch welch herren sie zu Schueler gehabt · die Kunst von Inen gelernet · vnd hinder Inen verlassen haben · etwas dunckel vnnd vnleerhafftig befunden · Aber der merertail Derselben Historiographeÿ sagen vnd zeugen · das Probas · welcher beruempter Fechter · vnnd ain lermaister Teseÿ · des Kunigs zu Athen Inn Griechenlannd · Inn welchem Reÿch die Ritterliche kunst Im anfanng · vnnd lannge zeit hernach vast · geplueet hat · gewesen ist · der erst erfinder vnnd aufrichter diser Kunst gewesen seÿ · Dann diser Probas die Ritterliche übung dem Kunig Teseÿ · mit so scho°nen grundtlichen Argumenten · dem Kunigreich vnnd Vatterlannd · auch allem ordenlichem wesen vnnd redlichkait · sampt allem was zu erhaltung der Freÿhait des Vatterlannds diennet · als ain hoch nutzliche Artzneÿ wider die vnutzen hinlessige faige faulkait · vnnd anndrer leichtuertigkait · zu dem ho°chsten geprisen · vnnd gelobet welches bemellter Kunig Teseus zu hertzen gefiert · vnnd hat Inn bedennckung · das dise Ritterliche Kunst vnnd übung des Fechtens · zu fridlichen zeiten der Jugent ein Eerliche vnnd manliche vbung seÿe Vnnd aber Inn der nott vnnd geferlichkait dem Vatterlannd zu ehrn · nutz vnnd wolfart raichen vnnd gedeihen mo°g · dem Probas · glauben geben vnnd darauf selbs · sampt etlichen der seinen vom hof des po°sten Adels · dise Ritterliche kunst des Fechtens zulernen vnnderstannden · Inn welchem Probas · hochbeflissen gewesen · Vnnd hat sich also die Eerliche Kunst des Fechtens · auß vrsachen das Jeder dem Vatterlannd · Inn der not zu helffen · dester Kunnder vnnd geschickter befunden wurd dermassen so vast zugenomen · Das bemelter Kunig Teseus · etliche ko°stliche heuser zu der übung diser Kunst · zu Athen vnnd annderstwo Inn seinem Reich · nicht mit wenigem uncosten · reichlich gebawen hat · Welches dann ein anfanng der lernung des Fechtens Inn gemain gewesen ist · Es haben sich aber dise ding beÿ dem zehenden Kunig [003r] der Athenienser Teseus genannt Welcher nach der Rechnung Vrspergensis 30 · Jar · geregiert · vngeuarlich Anno · 1224 · vor der geburt vnnsers hailannds Jhesu Christi · sich zugetragen · vnnd verloffen · vnnd von dannen her dise kunst · weliche die Kunig fundiert vnnd noch vil von Kunigelichem vnnd Furstlichem geschlecht vnnd gebluet · dasselbig Inen selbs zu ainner Adenlichen Vbung · dem vatterland zu Eern nutz vnnd notturfft geprauchen · auch billich ein Adelichs Ritterspil warhafftig genent werden mag · / Was aber fur fleÿs Vnnd Reichlicher vncosten von den alten auf dise Ritterliche Kunst des Fechtens gelegt · auch mit was ernst · vnnd Eerlichem ansehen dise übung gehalten worden · zudem was fur hohe personnen sich diser kunst zulernen vnnderfangen · vnd das auch dise Kunst allen Lannden vnnd Kunigreichen zu gutem geraicht habe · will ich auch erzelen vnd beschreiben · |

Und wiewol etlich der gelerten sagen, das dise kunst des ritterspils, wie andere künsten mer, unn die menschen zukomen, seinen einfluss, begird ud lust, von oben herab, das ist von Gott und himlischer inflyentz des Gestirns haben muess, malchs dann auch wol zu glauben, Hineben sagen ainsstails, das Polux, welchen die Römer geeret haben, ein anfenger diser Eerlichen kunst gewesen sey. Andere wollen solchen erfindung und eer, dem Mercurio zuaignen. Es werden aber beide antzeignung aus der ursach, das nicht befunden wirt, was nutz und frucht sie in diser kunst geschaft, auch welche herren sie zu schueler gehabt, die kunst von inen gelernet und hinder inen verlassen haben, etwas tunckel und unlerhafftig befunden. Aber der merentail derselben Historiographi, sagen und zeugen, das Probas, welcher berumbter fechter und lermaister Teseii des kunigs zu Athen in Griechenland in welchem raich die ritterliche kunst im anfang, und lange zeit hernach, vest geplüt hat, gewesen ist, der erst erfinder und aufrichter diser kunst gewesen sey. Dan diser Probas die ritterliche übung dem künig Teseii mit so schönen grüntlichen argumenten dem künigreich und vatterland auch allem ordentlichen wesen und redlichkeit, sambt allem was zu erhaltung der freiheit des vatterlands dienet, als ain hoch nützliche artzney wider die unnützen hinlessige faige faulhaitt [006*v] und andere liechtvertigkait, zu dem höchsten gebrisen und gelobet. Welches beelter kunig Teseus zu hertzen gefiert, und hat in bedenckung das dise ritterliche kunst und übung des fechtens zu fridlichen zeiten der jugent ein Eerliche und manliche ubung seye und aber in der not und geferlichkait dem vatterland zu eeren nutz und wolfart raichen und gedeihen mag, dem Probas glauben geben, und darauf selbs sambt etlichen der seinen vom hof des besten Adels, dise ritterliche kunst des fechtens zu lernen understanden, in welchem Probas hochbeflissen gewesen. Und hat sich also die Eerliche kunst des fechtens, ausz ursachen, das jeder dem vatterland, in der not zuhelffen dester künder und geschickter befunden wurd, dermassen so vast zugenomen. Das bemelter künig Teseus, etliche köstliche heuser zu der übung diser kunst, zu Athen und anderstwo in seinem Reich, nicht mit wenigen unkosten, reichlich gebauen hat. Welch dann ein anfang der lernung des fechtens in gemain gewesen ist. Es haben sich aber dise ding bey dem zehanden kunig der Athenienser Teseus genant, welcher nach der rechnung Ursperpensis, dreissig jar geregiert, ungefärlich anno .1224. vor der geburt unsers heilands Jhesu Christi, sich zugetragen und verlauffen, und von dannenher dise kunst welche die künig fundiert, und noch vil von küniglichen und fürstlichen geschlecht und gebluet, dasselbig inen selbst zu einer Adelichen übung, dem vatterland zu Eeren nutz und notturfft gebrauchen, auch billich ein Adeliges ritterpil warhafftig genent werden mag. Was aber für fleis und reichlicher unkosten von den alten, auf die ritterliche kunst des fechtens gelegt, auch mit was ernst, und eerlichem ansehen die übung gehalten worden, zudem was für hohe personen sich diser kunst zu lernen underfangen, und das auch dise kunst allen landen und künigreichen zu zu gutem gewirckt haben, will ich auch erzelen und beschreiben. |

[002v] Quidam eruditi Athleticam ex influentia astrorum certorum in mentes hominum delabi volunt, atque ex Deo eius desiderium fluere, quod quidem non incredibile et mihi videtur, quandoquidem omnia sunt in ipso, et per ipsum (attestante Apostolo). Sunt autem qui existimant Pollucem, quem Romani coluerunt, autorem certaminis istius fuisse primum, alii vero credunt a Mercurio Athleticam originem traxisse. Sed tamen obscure ab Autoribus traditur, quamobrem ea ab utroque sit reperta, quem ad usum, item quos predicti discipulos habuerint, atque post se reliquerint. In hoc tamen plerique Historiographorum consentiunt atque affirmant, quod Phorbas, qui celebris fertur fuisse Athleta, eiusque atris peritissimus, et Thesei Athenarum regis, Athletici certaminis praeceptor (Athenis igitur longo tempore eam floruisse attestantur, nec non originem indefluxisse) Primus artis inventis fuerit. Nam is Phorbas id exercitii genus Regi Theseo Multis probabilibus argumentis in utilitatem patriae tuendae descripsit, tum etiam in usum totium Regni accommodum, ad excitanda honorem ingenia ad omnes virtutes, contra desidiosos, et fortitudinem contemnentes. Quod certe exercitium Theseus intellexit iuventuti cedere ad omnis generis virtutes, cum temporibus pacatis tum vero magno usui fore rebus bellicis, atque salutem patriae ex hoc exercitio profluere. Quare ipse rex pariter cum nobilioribus, qui eius aulam sequebantur, athleticam didicit, et plures, qui id exercitii genus ad patriam defendendam aptum et utile esse cognoverunt, quod essent ad quaevis certamina subeunda habiliores. Ex ea igitur, ratione tantum Athletica incrementi sumpsit, ut Theseus aliquot aedes constituerit. In quibus iuventus hav in re exerceretur, non solum Athenis, verumetiam in aliis locis Atticis, non minimis sumptibus. Porro id exercitium sub Theseo Athenarum Rege decimo institutum est, qui iuxta Ursbergensis supputationem regnavit ante Christum redemptorem nostrum annis MCCXIIII. Quantam autem diligentiam et operam veteres in hoc exercitio insumpserint et qui viri nobiles gymnica certamina didicerint quantis sumptibus, quidque utilitatis inde fluxerit, in sequentibus ordine demonstrabo. |

||||

|

Because the human nature of budding youth may not rest or be idle, and because this knightly exercise as a manly virtue was well praised and held in high honour, not alone in Greece but all over the world, thus in the land of Greece, and in other places besides, and especially in the province of Boeotia, by the strong and widely famous fencing master Cercioni, places and sites were chosen and cleared where one could fence, wrestle, duel and practice other knightly games, which were given by him the name of Palestra, which name is still in use by the Latins. This example was followed by the mighty cities, such as Athens, Argis, Sparta, Corinth, and other peoples besides, which in the interest of beloved brevity I will refrain from describing. After the knightly art made entrance in Italy, the Romans with unspeakable cost very great and artful houses were constructed and called Theatrum, that is "show-houses", and the prize among these was attained by the Roman Consul Staurus, who built such an artful Theatrum, which stood on three hundred and sixty marble pillars, and full hundred fencers might therein fence, in honour of the god Jupiter. In these show-houses the fencing-masters would at appropriate times, specifically on holidays, assemble and hold such exercise of the knightly sport, dedicated to the honour of the gods, in the exercise of fencing, wrestling, running, both on horse and on foot. The exercise of fencing was also performed with such honourable and respectable virtuous order, that sessiones were held and introduced in which everyone, i.e. providing he was of nobility, or held an office of state, could sit and watch the knightly sport. That the Roman people loved the knightly sport to such an extent, and was assiduous to learn and visit it, that they once in such great number came to the Theatrum and show-houses, that these, in spite of being built with art and strength, could not endure such zest of the population that, as Livius writes, at Fidena such a house due to the great weight did collapse and fell to the ground, killing two thousand men.[5] Even in the current day, in many places such former and collapsed show-houses can be seen in Greece, Italy and Lombardy, especially in Rome and in Verona. |

Nachdem die mentschliche Nattur Inn der plueende Jugent nicht ruwen · oder feiren kan · Vnnd aber dise Ritterliche übung · als ain manliche tugendt nicht allain Inn · Grecia · sonnder Inn aller weelt größlich gelobt · vnnd Inn hochen Eern gehallten ward Do wurden Inn den lannden Grecia · vnnd anndern orten mer · vnnd besonders Inn der Lanndtschafft Boecia von dem starcken vnnd weit beruembten Fechtmaister Cercioni [003v] platz vnnd ort · darauf man Fechten Ringen Kempffen vnnd annder Ritterspil üben sollt erwelt vnnd gefreiet · die den namen Palestra · von Im empfanngen · vnd des die Lateiner noch zunennen Im geprauch haben · Dennen haben nachgeuolget · die gewaltigen Stet als Athen · Argis · Sparta · Corinthon · vnnd anndere völcker mer · die ich vmb geliebter kurtze willen · zu beschreiben vnderlassen · will Nachdem aber die Ritterliche Kunst Inn Italian eingetreten · seind von den Römern gar kunstliche grosse heuser · mit vnseglichem vncosten · Reichlich erbawet · vnnd · Theatrum · das ist Schawheuser genannt worden · vnnder welchen erbawungen · der Römisch Consul Staurus · welcher ein solichen kunstlichen Theatrum · der auf · 360 · Marbelstainen seulen stunde · vnnd hundert bar fechter darInnen Fechten mochten · dem Gott Jouis zu eern erbawet · den preis erlannget hat Inn welchen Schawheusern dann die Fechtmaister zu bequemblicher zeit · vnnd sonderlich an den Festtägen · darauf dann soliche übung des Ritterspils · den Go°ttern zu ehern gestifftet was · zusamen kamen · vnnd alsda Ir vbung des Fechtens Ringens lauffens · baides zu Roß vnnd fuoß hielten · Es wurden auch der vbung des Fechtens · mit so ainer Eerlichen ansehlichen züchtigen Ordnung zugesehen · das Sessiones · wohin Ieder dem Ritterspil zuzesehen . Namlich · nachdem er geadlet · oder Inn des Rats Ämbtern gewesen · sitzen sollt · gemacht vnnd geordnet wurden · dann das Römisch volckh diß Ritterspil dermassen geliebt vnnd das zulernen vnnd zubesuechen · so hoch beflissen gewesen das sÿ etwann mit so grosser anzal Inn die Theatrum · vnnd Schawheuser zusamen · kumen das die gemellte gebew · unangesehen · das sie von kunst vnd sterck so fleissig gemacht · solchen last des volckhs · nicht hat ertragen mo°gen Vnnd wie Liuius schreibt das zu Fidena · ein solch haus · von wegen des grossen lasts ernider ganngen · zu boden gefallen · vnnd ob · 2000 · · Mentschen · erschlagen hab Es werden aber noch heutigstags an vil orten · solche anzaigung der verganngne vnnd zerfalne Schawheuser Inn Griechen · Italia vnnd Lombardia · vil gesehen vnnd Innsonders zu Rom vnd Diethrichs Bern noch heutigstags · gute anzaigung von sich geben · |

Nachdem die menschliche Natur der plüende jugend nicht ruwen, odere feiren kan unnd aber dise ritterliche übung als ain manliche tugend, nicht allain in Grecia, sondern in aller Welt, grosslich gelobt, und in hohen eeren gehalten ward, So wurden in den Landen Grecie, und andern orten mere und besonders in der Landschaft Boecia, von dem starcken und weitberumbten fechtmeister Cercioni, plätz und ort, darauf man fechten, ringen, kampggen, und andere ritterspil üben solt, erwelt und gefreiet, die den namen Palestra von im empfangen, und dass die Lateiner noch zunennen im gebrauch haben. Denen haben nachgevolget die gewaltigen stet, Als Athen, Argis, Sparta, Corinthon, und andere Volcker mer, die ich umb geliebter kurtze willen zubeschreiben underlassen will. Nachdem aber die ritterliche kunst in Italia eingetretten, sind von den Römern gar künstliche grosse heuser, mit unseglichen kosten, wirklich erbauet, und Theatrum, das ist Schauheuser genant worden, under welchen verbauungen, der römisch Consul Staurus, welcher ein sollichen künstlichen Theatrum, der auff dreihundert und sechtzig marmolstainen seulen stunde, und hundert bar fechter darinnen fechten mochten, dem Got Jovis zu eeren erbauett, den preis erlanget hat. In welchen schauheusern dann die fechtmaister zu bequemlicher zeit, und sonderlich an den festtagen, darauff dann sollche übung des ritterspils, den Göttern zu eeren gestifftet war, zusamen kamen, und alda in übung des fechtens, ringens, lauffens, baides zu ross und fuss, hielten. Es wurde auch der übung des fechtens mit so einer eerlich ansehlichen züchtigen ordnung zugeschen, das sessiones, wohin jeder dem ritterspil zugesehen, namlich nach dem eer geadelt, oder in des rats ämbteren gewesen, sitzen solt, gemacht und geordnet wurden. Dann das römisch volck disen ritterspil dermasen geliebt und das zulernen und zubesuchen, so hochbeflissen gewesen, das sie ettwan mit so grosser antzal inn die Theatrum und schaufhauser zusamen kamen, das die bemelte geben unangesehen das sie [007*r] von kunst und sterck so fleissig gemacht solchen lust des volcks nicht haben ertragen mugenn, und wie Livius schreibt, das zu Fidena ein solch haus von wegen des grossen lasts, ernider gang zu boden gefallen, und ob zwaitausent menschen erschlagen hab. Es werden aber noch heuttigen tags an vil orten solche antzaignung der vergangene und zerfalne scheuhauser in Griechen, Italia, und Lombardia, vil gesehen, und insonders zu Rom und Diettrichs Bern noch heuttigentags gute antzaignung von sich geben. |

[2] Natura hominum ita constituta est, praecipue autem iuventutis, ut [003r] nunquam esse ociosa possit, sed animum ad aliquod negotium subinde adiungat, quare factum est, cum Athletica iam non solum in Grecia verumetiam in toto terrarum orbe celebraretur, ut certa loca in Graecia, et maxime in Boeotia ad eam artem exercendam destinarentur per cercionem Athletam strenuum, quibus luctae, Certamina Gymnica et alia honesta exercitia agerentur, dictique ii loci sunt palestre quod nomen et apud nos hodie obtinuerunt. Hos postea imitati sunt Athenienses, Argivi, Lacedaemonii, Corinthii et alii populi quamplurimi, quorum breviati studens, mentionem hoc loco facere non licet. Postquam veri in Italiam Athletica translata est Romanique in primis, sumptibus et impensis ineffabilibus Romani aedes splendidas ad eam artem exercendam construxere, easque amplissimas, que postea Theatra adpellari coeperunt, quorum Scaurus Consul Romanus unum construxit, trecentis et sexaginta columnis marmoreis nitens, in quo poterant Athletae ducenti invicem concertare, erat autem id Theatrum in Honorem Iovis aedificatum. In iis igitur Theatris pugnabantur certis temporibus diebus scilicet solennibus iisque qui Deorum honoribus addicti erant. Varia autem erant certamina, cursus nimirum, luctarumque dimicationes pariter pedestres et equestres. Ad eas spectandas certae sedes distribuebantur iuxta cuiusvis dignitatem spectantium. Populus Romanus tanto amore, tantaque voluptate ista certamina prosequutus est, ut ita frequentes in Theatris convenerint, ut etiamsi ea essent firmissime coagmentata, aliquando prae multitudine et turba spectantium collapsa sint. Livius quoque scripsit Fidenis Theatrum corruisse, atque viginti milia hominum [003v] oppressisse, qui spectandi gratia convenerant. Caeterum multis in locis hodie vestigia collapsorum Theatrorum visuntur in Graecia, Italia Lombardia, Romae et Veronae. |

||||

|

Above we have heard how this knightly art of manhood was afforded and established by the learned and wise, also by the kings and princes as leaders of lands and kingdoms, which was done for the reason that land and people, widows and orphans would be kept in peace, calm and liberty, protected and saved from tyrants. For this to have its perfect and prosperous success, the highest heads, i.e. kings, princes, consuls and senators, did themselves undertake, learn and practice this knightly art, so as to present an example and motivation for their subjects, and there would be a great number of high potentates, i.e. emperors, kings, princes and noblemen, to be named at this point, which I have foregone, particularly in the case of the Greeks, not to put too much of a burden on the kind reader, and only alone the most notable Romans will I most briefly introduce and describe as a testimonial on the topic. |

Zuuor ist gehört Wie das dise Ritterliche Kunst · der Mannlichkait · von den geleert verstenndigen auch von den Kunigen vnnd Fursten · als vorsteeher der lannden vnd Kunigreichen · selbes herfur gebracht · vnnd fundiert worden seÿ · welchs dann auß vrsachen · das Lannd vnnd Lewt · [004r] Witwen vnnd Waisen · beÿ friden · ruw · vnnd Freÿhaiten beleiben · vnnd vor den Tÿrannen · beschutzt vnnd errettet werden mögen · beschechen ist · Hat aber solchs seinnen volkumnen außganng fruchtbarlich haben söllen · so haben die höchsten ha°ubter · als Kunig · Fursten · Consules vnd Senatores · dise Ritterliche Kunst · selbs fur die hand nemmen · leernen · vnnd Inn das werckh pringen · vnnd damit also anndern Iren vnnderthanen · ein Exempel der anraitzung · von sich geben muessen · vnnd weren Inn disem faal der hochen Potentaten · als · Kaiser · Kunig · Fursten vnnd Herren · seer vil zubenennen · welchs Jch / auf das der guthertzig Leser nicht zuuil beschwert werde · Vnnd Innsonders der Griechen zumelden vnnderlassen · Aber allain die Namhafftigesten Römer · zu zeugknuß der sach · zudem kurtzisten einfiern vnd beschreiben will ·/· |

Zuvor ist gehört, Wie das dise ritterliche kunst der manlichkait, von den gelert verstendigen, auch von den künigen und fürsten, als vorsteer der landen und künigreichen, selbs herfürgebrachtt und fundiert worden sey, welchs dann aus ursachen das Land und leut, witwen und waisen bey friden, ruw, und freihaiten beleiben, und von den Tyrannen beschützt und errettet werden mugen, beschehen ist. Hat aber solchs seinen volkommen ausgang fruchtbarlich haben sollen, So habenn die höchsten häubten, als künig, fürste, Consules und Senatores, dise ritterliche kunst selbs für die hand nemen, lernen, und in das werck bringen, und damit also under anderen iren underthanen, ein Exempel der anraitzung von sich geben muessen, Und weren in disem fall der hohen potentaten, als kaiser, künig, färsten, und herren, seer vil zu benennen, welchs ich, auff das der guthertzig Leser nicht zuvil beschwert werde, und insonders der Griechen, zumelden underlassen, (aber allain die namhafftigsten Römer, zum zeugknus der sach, zu dem kürtzesten einfieren, und beschreiben will. |

Supra commemoratum est, Gymnica Certamina a doctis viris, regibus, principibus atque gubernacula rerum publicarum sustinentibus in lucem esse aedita, et ad usum traducta defendi regna, Imperia et communem libertatem, quod autem ista felicius procederent et eventum prosperiorem adipiscerentir, reges ipsi, principes consules senatoresque ipsa exercitia, quibus de agimus, didicerunt adque curaverunt, ea in usum iuventutis produci, exemploque aliis se esse voluerunt ut ii se aemularentur. |

||||

|

Romulus, the first founder and lawmaker of the city of Rome, and king thereat, according to the description by Plutarch, did hold himself so praiseworthy and fairly by his strength, swiftness and art of fencing in the war against the Fidenates that the enemy was beaten and the name of Rome did receive much praise, profit and honour. |

Romulus. der erste Stiffter vnnd Gesatzgeber · der Stat Rom · vnd Kunig daselbst · hat sich nach beschreibung Plutarche · durch sein sterckh · geschwindigkait vnnd kunst des Fechttens · Im streit wider die Fidenates · so loblich vnnd Redlich gehallten · das die feind geschlagen vnd dardurch · dem Römischen namen grossers lob · Nutz vnnd Eer widerfaren ist / |

Romulus der erst stiffter und gesatzgeber der stat Rom, und künig daselbst, hat sich nach beschreibung Plutarchi, durch sein sterck, geschwindigkait und kunst des fechtens, im strait wider die Fidenates, so loblich und redlich gehalten, das die feind geschlagen, und dadurch dem römischen namen grosses lob, nutz und eer widerfaren ist. |

Romulus primus Romanorum Rex, conditor urbis, et legislator contra Fidenates tanta pugnandi arte, robore et velocitate pugnasse dicitur (Plutarcho teste) ut omnes ultra vires humanas certasse eum faterentur, et in eo Proelio maxima pars caedis soli Romulo attribueretur. |

||||

|

But that the worthy Romans did place their trust, hope and refuge in the knightly art of fencing even at the time of most dire need is testified by Julius Caesar himself, and by Crispus Palustinus and even by the entire worship of writers. |

Das aber die werden Römer ir vertrauen, hoffnung und zuflucht in die ritterlichen kunst dess fechtens, ja auch in der zeit der höchsten not gesetzt haben, bezeugt Julius Cesar selb, auch Crispus Palustinus,[6] und schier die gantz schar der Scribenten. |

||||||

|

The said Julius Caesar writes that as he undertook his quick march upon Rome, that Pompey was in such need to flee Rome and so fearful that he did call to him and exhort the masters of the knightly art of fencing together with their school disciples and their family for his protection and led them away with him. With this masterful move Pompey did imagine that he had create for himself a double profit, firstly by keeping around him valiant persons experienced in such knightly art and secondly that he by this would vex Julius his enemy by reducing, breaking and divesting him of his strength and support. |

Bemelter Julius Cesar schreibt, als er seinen schnellen zug auf Rom furgenommen, das dem Pompeio so notig von Rom zu fliehen, auch so furchtsam gewesen, das Er die maister der ritterlichen kunst des fechtens, sambt irer schul discipel und geschlechter in die vil beruefft, auffgemanet, und zu seinem beschutz, mit im hinweg gefuert hab. Mit herllichem stuck pompaiens vermainet, ime zwen nütz geschaffet haben, Erstlich, das er mit sollichen ritterlich kunst, erfarene tapffere personen bey ime behalten, und damit desterbass benarrt wurde, fur das ander, das dem Julio seinem feind, sein sterck und hilff geringert, zerbrochen und entzogen wurde. |

||||||

|

Likewise the Roman senator Palustrinus writes on the Roman insurgence and rabblement of Catilinus that the most famous prince of all orators, Cicero, at the time Roman mayor and keeper of the city of Rome, upon whom the entire senate of the city of Rome laid the burden of the Roman public interest so that the city would not take ruinous damage by the impudent rabblement of Catilinus, among other prudent actions did order to assemble all valiant and honest masters of the sword, and their associated families and disciples, who in all weapons had learned, been instructed and exercised in how to use them to full advantage, not just in the city of Rome but also in Capua and other cities of Italy, which thereafter did receive the Roman freedom, so that they in the most dire need of the city of Rome did handsomely perform the most urgent office of the night-watch, which council the worthy Romans took in this and in similar pernicious riots, so that the noble Romans did ever and always hold this knightly art in highest honour so that they might rely on the same in times of acute need, from which their might, power and glory did increase daily.[7] |

Dessgleichen schreibt der römisch senatore Palustinus in der römischen aufrur und rottierung Catalini auch, das der hochberuembt fürst aller Oratores Cicero, diser zeit römischer Burgermaister und erhalter der stat Rom, Als im von dem gantzen senat der stat Rom, auff das die stat von der frechen Rottierung Catalini nicht verderblichen schaden empfinge, die gantz bürde des romischen gemainen nutz auferlegt worden, Welcher under anderen waisslichen furschungen geordert hat, namlich, das alle tapffer und redliche maister des schwerts, und derselben zugethanen geschlechter oder discipel, welliche in allen gewherenn mit allem vortail dieselben zugebrauchen gelert, underwisen, und geubt gewesen, nicht allain in der stat Rom, sonde zu Capua und allen andern stetten in Italian die sich dann der römischen freihait gebrauchen, zusamen beruffen, und denselben in solcher der stat Rom [007*v] höchster not, das allersorgklichest ambt, als die nacht schiltwacht, durch welliche alle rottirung leichtlich abgetriben werden mag, statlich beholfen hat, wellicher ratschlag dan werden Römern in diser und anderen dergleichen verderblichen auffruern, wol verschlossen hab, derhalben die Edlen Römer dise ritterliche kunst auff das sie derselben in der zeit furfallender nott gemessen mochten, je und allwegen hohen eeren gehalten, dadurch dann ir macht, gwalt und herrlichkait, taglich zugenomen. |

||||||

|

Julius, the first Roman emperor, did entrust his life to his body-guard, native Germans and famous fencers, more than four hundred in number, and to no-one else, and in Rome on the field of Mars he did himself fence, and did donate several treasures and prizes to the fencers shortly before his death. Likewise did emperor Augustus with great delight support and help the fencers, which example of love for the knightly art was freely followed by Tiberius the third Roman emperor, as is all recorded by Suetonius Tranquillus[8] and by others besides in their accounts. |

Julius · der erst Römische Kaiser · Hat seinnes Leibs Gwardia · so geboren Teutschen · vnnd beruembte Fechter · deren auch vber vierhundert gewesen · seinen leib allain · vnd sunst niemand annders vertrawen wo°llen vnnd zu Rom auf dem platz Marcio · selbs gefochten · auch etlich Clainat vnnd gewinnet er den Fechtern kurtzlich vor seinem Tod aufgeworffen · Deßgleichen · [004v] hat auch · Augustus · der Kaiser mit grössem Lust · selbs gethon · die Fechter angericht · darzu geholffen . vnnd zugesehen · welchem dann Tiberius der drit · Römisch Kaiser Inn liebe der Ritterlichen Kunst Reichlich nachgeuolget hat · welchs alles Suetonius Tranquillus vnnd annder mer Inn Iren beschreibungen melden · |

Julius der erst römisch kaiser, hat seines leibs guardia, so geboren Teutschen und beruembte fechter, davon auch uber vierhundert gewesen, seinen Leib allain, und sonst niemand anders vertrauen wollen, und zu Rom auff dem platz Marcio selbs gefochten, auch etliche Clainat unnd gewinnet er den fechtern kurtzlich vor seinem tod auffgeworffen. Deszgleichen hat auch Augustus der kaiser mit grossem lust selbs gethan. Die fechter angericht, dartzuo geholffen unnd zugesehen. Welchem dann Tiberius der dritt römisch kaiser in liebe der ritterlichen kunst reichlich nachgevolget hat, welches alles Suetonius Tranquillus und andere mer inn iren beschreibungen melden. |

Civilis primus Romanorum Imperator sui corporis custodibus usus est Germanis athleticorum certaminum peritissimis, quorum quadringenti numeri fuere is in Campo Martio Romae aliquando pugilem se exhibuit, nec non paulo ante obitum suum Athletis, qui victoriam obtinerent, brabea danda curavit. Idem etiam Augustus fecit, nam non modo ista certamina athletica instituit, sed etiam ea praesentia [004r] sua ornavit, utque omnia agerentur, summa diligentia mandavit, quem item Tiberius imperator Romanorum tertius egregiae aemulatus est, quorum Suetonius Tranquillus fraequenter mentionem facere solet. |

||||

|

The Romans were had the custom in spiritual matters of honouring the gods with this exercise of the knightly sport on their customary fest-days. In the month of March did they honourably hold a great feast lasting five days, of which three days of fencing for Pallas as a goddess of war. During these three days a special captain was designated who should instruct the youth in the upholding of manly honesty in fencing with all weapons twice daily, in the morning and in the evening. As the funeral of the body of Brutus should be held, his two sons Marcus and Decius did ordain abundant prizes and treasures for the fencers for which they should fence. Likewise as the emperor Probus won his victory against the Germans and did triumph he did let fence a total of three hundred[9] naked fencers in front of the public. |

Die Römer · hetten ein gewonhait das Sie Inn Gaistlichen sachen die Götter mit diser vbung des Ritterspils · auf gewonlichen Festtagen · vereereten · Im monat Martio · haben sie der Palladj · als ainner Göttin des Kriegs · ein gro°ß Fest namlich Funff tag lanng darunder dreÿ tag mit Fechten volbracht wurden · ganntz Eerlich gehallten · Inn welchen dreien tagen was ein besonderer Hauptman verordnet · der die Jugent zuerhaltung der manlichen redlichkait Im Fechten · Inn allen whoren zwaÿmal Im tag zu mörgens vnnd abents vnnderweisen sollt · als die leicht Brutj. vnnd sein begrebnuß beganngen werden sollt · haben seine zwen Sune Marcus · vnd Decius · den Fechtern gewinneter vnnd Clainnater · darumb zu Fechten reichlich verordnet · desselben gleichen · als · Probas · der Kaiser wider die Teutschen den sig erlanngt vnnd Triumphiert · hat er den Göttern zu Eern · neben anndern vierhundert bar Fechter · vor der gemaind Fechten lassen · |

Die römer hetten ein gewonhait das sie in gaistlichen sachen die Götter mit diser übung des Ritterspils auf gewonlichen festtagen vereereten. Im Monat Martio haben sie der Palladi als ainer Göttin des kriegs ein grosz fest nemlich fünff taglang darunder drey tag mit fechten volbracht wurden gantz eerlich gehalten. In welchen dreien tagen was ein besonderer haubtman verordnet, der die Jugent zu erhaltung der manlichen redlichkeit, im fechten mit allen wheren zwaymal im tag zumorgens und abends, underweisen solt. Als die leicht Bruti und sein begrabung begangen werden sollt haben seine zwen süne Marcus unnd Decius, den fechtern gewinneter unnd Clainater darumb zu fechten raichlich verordnet. Desselben gleichen als Probus der kaiser wider die Teutschen den sig erlangt unnd triumphiert, hat er den Göttern zu eeren neben anderen dreihundert bar fechter vor der gemaind fechten lassen. |

Romanis consuetudo fuit, multorum testimonio, ut Deos suos (vetusti praemissimus paulo ante) diebus festis huiusmodi Athleticas certaminibus colerent. Mense martio quinque diebus continuis certabatur, in honorem Palladis deae bellicae, quorum tres Athletae pulcherrimis congressibus mutuis consumerbant, quo tempore Centurio selectus erat, qui iuvenes in praedictis certaminibus variis armis bis silgulis diebus mane scilicet et vestperi exerceret. In funere Bruti, filii eius Athletis brabea constituerunt magnifica, pro quibus certaretur, Marcus nempe et Decius. Item Probus cum Germanos vicisset proelio, atque de iis triumphasset, in honorem Deorum, per quos victoriam obtinuisset trecenta paria Athletarum qui mutuo congrederentur in populi conspectu, constituit. |

||||

|

Likewise, Dominicanus by night and Gordianus at one time five hundred naked fencers, and after him emperor Philip the Arab, in a spectacle for the Roman people and in honour of his triumph did let fence a full thousand naked fencers on a single day.[10] Of such examples and histories would be many others to be told, but I feel that this should suffice for a general indication. |

Gleÿchsfals · Domicianus · etwann beÿ der Nacht · vnd Gordianus auf ein zeit Funffhundert Bar Fechter · vnnd hernaher Kaiser Philippus · der Arabier · Inn ainnem Schawspil · dem Römischen volckh vnnd seinem Triumph zu ehrn Tausent Bar Fechter · auf ain tag hat Fechten lassen · Deren Exempel · vnnd geschichte~ weren noch vil zuerzelen · aber mich bedunckt das dißmals zu ainer anzaigung gnug seÿ · |

Gleichfals Dominicanus etwann bey der nacht und Gordianus auff ein Zeit fünffhundert bar fechter, unnd hernach kaiser Philippus der Arabier, in einem schauspiel dem römischen volck und seinem Triumph zu eeren Tausent bar fechter auff einen tag hat fechten lassen. Deren Exempel unnd geschichten, weren noch vil zu erzelen, aber mich bedünckt das deszmals zu einer antzaigung genug sey. |

Idem fecisse Domitianum ferunt aliquando noctis tempore, Gordianus quandoque quingenta Athletarum paria ordinavit, quod imitatus Philippus Arabus mille paria eodem Theatro et Spectaculo congredi mandavit. Quarum rerum exempla ubique etiam apud probatos authores extant, quare ista hoc loco recitasse satis sit. |

||||

|

There was however in the beginning and during that time a different mindset in fencing, and as each judicious fencer may gauge for himself, the artful plays and hidden holds, steps and strikes may in origin not have been worked out as they have now, but over time, as the learned, whom I shall name below, also kings, princes and noblemen did dedicate themselves to the knightly exercise, by their assiduity were discovered the best artful plays and advantages with which a man might win in all tasks and cases of necessity, and this has gone on for such a time that in the end they were set down in epitomes or books, with figures and writing, so that one may still in this current day consult the experience of those ancients who did love the art. |

[005r] Es hat aber Im anfanng Vnnd zu diser zeit · ein anndere Mainung Inn dem Fechten gehabt · vnnd nachdem ein Jeder verstenndiger Fechter selbs ermessen kan · so haben die Kunstliche stuckh vnnd verborgne griff · trit vnnd straich Im anfanng nicht wie Jetzund · herfurgethan werden mögen · aber mit der Zeit · als sich die gelerten · die ich hernach benennen will · Auch die Kunig / Fursten vnnd herren · sich der Ritterlichen übung angenommen · alda seind die bösten Kunstlichsten stuckh vnnd vortail · damit der mann Inn allem thun vnnd faellen der nott · gewunnen werden möcht · durch Iren vleÿß herfurkumen · vnnd hat solches so lanng gewehret · das sie zuletst Inn Zettel oder Buecher · mit bossen vnnd schrifften · gebracht worden sein · als man dann beÿ den alten · so die Kunst geliebt noch heutigs tags · Inn der erfarung sihet · |

Es hat aber im anfang und zu diser zeit ein anderer meinung in dem fechten gehabt, und nach dem ein jeder verstandiger fechter selbs ermessen knn, so haben die künstliche stück und verborgene griff, tritt und straich, im anfang nicht wie jetzund, herfür gethan worden mugen, aber mit der zeit, als sich die gelerten, die ich hernach benennen will, auch die künig, fürsten unnd herren, sich der ritterlichen übung angenomen, alda seind die besten künstlichsten stück und vortail, damit der mann in allem thun und fällen der not, gewunnen werden möcht, durch iren fleis herfürkomen, und hat solches so lang geweret, das sie zuletzt in zettel oder büchern, mit bossen und schrifften, gebracht worden sein, als man dann bey den alten, so die kunst geliebt, noch heutigs tags in der erfarung sihet. |

Caeterum eo tempore, ubi primum Athletica exerceri coepit longe [004v] alia Ictuum, congressuum et aliorum eius artis habitum ratio fuit, nam ab initio statim ea tam atrificiose, ut nunc in usu sunt, excogitari non poterant, verum succedenti tempore in melius cessere, cum reges, principes et heroes eam artem ipsi coepissent tractare et exercere, tum optima quemque eius artis antea incognita atque occulta in luce prodierunt. Ea itaque ratione contigit, ut imagines athletarum habitibus certis in certaminibus mutuis utentium, tabulis insculperentur, nec non libris inscriberentur ut adhuc nostro saeculo videre licet. |

||||

|

In addition, the ancients, and especially the Greeks, did have such desire and love for the knightly exercise, that they did forego any kind of sweet food or drink several days before they would fence, likewise the lust of women besides all else that weakens the body and makes for heavy breathing, and did peruse such foods, as meat and other kinds, as do strengthen the body. On this matter did the learned medici, and especially the most famous Galen,[11] repeatedly and artfully discuss, whether austerity and abstinence or the practice of fencing would profit more for the life of man. Also Saint Paul does report such an example in his epistle where he says, you see that those who would fence and fight over a transient honour or treasure are wont to forego all lust, as if he would say, why do not you the same, as pious Christians who are fighting not for an earthly but for a heavenly honour in this world.[12] And therefore all those who love this knightly art do well to consider that in those times there were no drunken and immodest but sober, apt and most artful fencers. Also, it is rarely found in writing that among the ancients fencing was undertaken out of envy or hatred, as in our times regrettably occurs often, but out of love and artfulness. After the ancients did chastise themselves as they were expecting the day of fencing, they and the weapons with which they would fence were transported in all honesty on wagons to the fencing place or Theatrum, and for them the prizes and treasures were painted in fine likeness and carried before them, and also beforehand publicly posted on the market-place, and thus made known to the common man. This custom is attributed by the historiographers with great praise to Terentius Lucanus, who on three consecutive days did permanently have thirty naked fencers on the field, and when the fencers, masters and disciples entered the fencing place they put down their weapons in proper order (as is still the custom today); then the names of all fencers were written on pieces of paper and then with great assiduity the lot was drawn arbitrarily, and those two who were drawn by the lot then did have to fight most artfully and honourably for the treasure. For this, each of the fencers did most assiduously invoke their god, one Hercules, the other Mercury, yet others Pollux and Castor, and so forth, and pray that the lot would pair them with good and artful fencers, and not immodest ones who were not well experienced in the art. All of this does illustrate that the ancients did fence above all for art and knightly virtue and honour than for any other things, for which reason, for the later generations of fencers and for the honour of the knightly art, the fight-schools as they were held and the promenading houses and halls of the rich were painted in their likeness, and those who held them, and those who won the prize were finely depicted, and the highest prize in this was retained by the freedman of emperor Nero who at Antium at the great imperial palace and promenade did most artfully and gracefully depict the likeness of the fencing-schools and fencers.[13] |

Zudem haben die alten Unnd Innsonders die Griechen · ein solchen lust vnnd liebe der Ritterlichen vbung gehabt · das sie sich etlich tag zuuor emalen sie haben Fechten wo°llen · etlicher schleckhafftiger speiß vnnd getrannckh · auch vor dem wollust der weiber · sampt allem was den Leib schwecht vnnd schweren athem machet / enthallten, vnnd sich der speis · als flaisch vnnd annders so den leib sterckt/ gebraucht · Derhalben die gelerten · Medicj ·vnnd Innsunder der weitberuembt · Galenus · mermalen daruon Kunstlich disputiert haben · ob der abpruch vnnd abstinentz · oder die vbung des Fechtens · dem leben des Mentschens nutzer seÿe · Der hailig Paulus meldet solichs Exempels weis auch Inn seinner Epistel da er sagt Ir Sehent das sich alle die · welche vmb ein zeitlich zergenngckliche Eer vnnd klainat Fechten vnnd streiten wo°llen · sich von allem wollust enthallten · Als wollt er sagen · warumb nit Ir als fromen Christen · auch , die nit vmb ein Irdisch · sonder vmb ein Himlische Eer Inn diser wellt streitten ?? Vnnd haben derhalben alle liebhaber diser Ritterlichen Kunst · wol zugedenncken · das es diser Zeit nit volle trunckne · vnnd vnbeschaidne · sonnder nuechtere geschickte · vnnd ganntz Kunstliche Fechter geben hat · Man findt auch sellten Inn schrifften · das beÿ den vrallten auß neid vnd haß · sonder auß lieb vnnd Kunst gefochten worden seÿ als laider zu vnnser Zeit vil beschicht · Wann die alten sich gecastigeÿet vnnd also den tag des Fechtens erwartet haben Da hat man dann die Fechter mit Iren gewho°ren darInnen sie haben Fechten sollen · ganntz Eerlich auf we°gen zu dem Fechtplatz oder · Theatrum · gefuert · vnnd Inen die gewinneter vnnd Clainat fein abgemalt Conterfect · [005v] vorher getragen · auch solchs am marckt zuuor Angeschlagen dem gemainen man solches damit zu wissen gethon · Disen gebrauch geben die Historischreiber dem Terencio Lutano · welcher dreÿ tag nachainannder alweg dreÿssig bar Fechter auf dem platz zu fechten gehallten · mit grossem lob zu vnnd wann dann die Fechter · Maister vnnd Junger auf den Fechtplatz komen · haben sie dann die gewho°ren (· wie dann noch Im geprauch ist ·) nach ordnung nider gelegt · alß dann seind aller Fechter Namen auf zettelin von pappir geschriben worden · vnnd darnach das loß ganntz vngeuarlich mit höchsten vleÿß gehallten · Vnnd welche zwen dann mit dem loß heraus komen sein · haben dann vmb die klainat · ganntz kunstlich vnnd Eerlich Fechten muessen · Inndem haben die Fechter Jeder sein gott · ainner den Herculem · der annder den Mercurium · die anndern Polux · vnnd Castorem · vnd also furtan · mit höchstem fleyß angeruffen vnnd gebeten · das Inen gute kunstliche · vnnd nicht vnbeschaidne · die der Kunst nicht wol erfaren · Fechter · Im loß zugeschickt · vnnd beschert werden solt · Welchs dann alles ein anzaigung von sich gibet · Das die alten mer durch kunst · vnnd von · Ritterlicher Zucht vnnd Eern · dann vmb annderer sachen wegen gefochten haben · vmb disen willen den nachkomenden Fechtern · vnnd der Ritterlichen Kunst zu eern · die Fechtschuolen · wie die gehallten worden · an die Spacierheuser vnnd Sael der reichen Contrafectisch abgemalt · vnnd wer die gehalten · vnnd den preis erlangt · fein beschriben worden · seind · vnnder welchen der Libertus des Kaisers Neronis · welcher zu Ancio · an dem grossen Kaiserlichen pallast vnnd spacierhaus · die Fechtschuolen vnnd Fechter gar artlich vnnd zierlich hat abconterfecten lassen · den preiß behallten · |

[008*r] Zudem haben die alten, und insonders die Griechen, ein solchen lust und liebe zu der ritterlichen übung gehabt, das sie sich etlich tag zuvor, eemalen sie haben fechten wollen, etlicher schleckhaftiger speis und getranck, auch von dem wollust der weiber, sambt allem was den leib schwechet, und schweren athem machet, enthalten, und sich der speis, als flaisch und anders, so den leib sterckt, gebraucht. Derhalben die gelerten Medici, und insonder der weitberuembt Galenus, mermalen davon kunstlich disputiert haben, ob der abpruch und abstinentz, oder die übung des fechtens, dem leben das menschens nutzer seie. Der hailig Paulus meldet solchs Exempelsz wais auch in seiner Epistel da er sagt, ir sehent das sich alle die, welche umb ein zergengkliche Eer unnd Clainat, fechten und streitten wollen, sich von allem wollust enthalten, als wolt er sagen, warumb nit ir als fromme Christen auch, die nit umb ein irdisch, sonder umb ein himmlische eer in diser welt streitten ·/· Und haben derhalben alle liebhaber diser ritterlichen kunst, wol zugedencken, das es diser zeit nicht wolle truncken, und onbeschaiden, sonder nüchtern, geschickte, unnd gantz künstliche fechter geben hatt. Man findet auch selten in schrifften, das bey den uralten aus neid und hasz, sonder aus lieb unnd kunst, gefochten worden seig, als laider zu unser zeit viel beschihet. Wann die alten sich gekastigiret, und also den tag des fechtens erwartet haben, da hat man dann die fechter mit iren gewhören darinnen sie haben fechten sollen gantz eerlich auff wägen zu dem fechtplatz oder Theatrum, gefüert, und inen die gewinneter unnd Clainaten fein abgemalt Conterfect vorher getragen, auch solchs am markt zuvor angeschlagen, dem gemainen mann solchs damit zu wissen gethan. Disen gebrauch geben die historischreiber dem Terencio Lucano, welcher drey tag nacheinander allweg dreissig bar fechter auf dem platz zu fechten gehalten, mit grossem lob zu, und wann dann die fechter, maister und jünger auff den fechtplatz komen, haben sie dann die gewehren (.wie dann noch in gebrauch ist.) nach ordnung nidergelegt, alsz dann saind aller fechter namen auff zedelen von papir geschriben worden und darnach das losz gantz ongefarlich mit höchstem flais gehalten, uind welche zwen dann mit dem losz herausz komen sein, habend dann umb die klainat, gantz künstlich und eerlich fechten müessen. In dem haben die fechter ieder sein Gott, ainer den Herculem, der andere den Mercurium, die anderen Pollucem unnd Castorem, und also furtan, mit höchstem fleis angeruffen unnd gebetten, das iren gutte künstliche, und nicht onbeschaiden, die der kunst nit wol erfaren, fechter, in losz zugeschickt und beschert werden solt. Welchs dann alles ain antzaignung von sich gibt, das die alten mer durch kunst, und von ritterlicher zucht und eeren, dann umb andrer sachen wegen, gefochten haben, umb dessen willen den nachkomenden fechtern und der ritterlich kunst zu eeren, die fechtschulen wie die gehalten worden, and die spatzierhäuser und säl der reichen contrafectisch abgemalt, und wer die gehalten, und den preis erlangt, fein beschreiben wordenn seind, under welchen der Libertus des kaisers Neronis, welcher zu Ancio an dem grossen kaiserlichen pallast und spatzierhaus, die fechtschulen und fechter, gar artlich und zierlich, hat abconterfecten lassen, den preisz behalten. |

Antiquos et Grecos Athletica tantopere delectavit, ut antequamque in certamina gymnica descenderent omnis generis deliciis quem corporis vires exhaurirent, abstinerent, praecipue autem sibi a Venere cavebant, etiam ab iis quae spiritus difficultatem redderent, contra autem carnibus et aliis cibis qui corpus corroborant, vescebantur. Idcirco saepe Medici exellentiores interse disceptarunt, et Galenus ille peritissimus disputavit, num abstinentia, vel exercitum Athleticum vitae humanae commodius et utilius sit. Et Paulus mentionem eius rei facit in Epistola prima ad Corinthios inquirens: “nonne videtis quod qui pro Corona peritura decertant per omnia sunt temperantes? “ Innuens, ut nos quemadmodum pios Christianos deced, pro corona aeterna et non tantum peritura decertemus. Et hoc loco monendi sumus, ad Athleticam ebriosos, immodestas, et furiosos, ineptos plane esse: contra vero sobrios et temperantes, nam veteres non ex invidia et odio moti concitatique mutuo concertarunt sed potius amore mutuo, atque ipsius artis delectatione. Cum tempus decertandi Athleticae advenisset, Athletae Curribus praeciosis in Theatra vectabantur iis prabea splendide atque eleganter picta, priusquam vero id adornaretur, publice affigebatur, quo tempore inituri esset Athletae certamen, quo eius populus certior redderetur, seque ad id spectandum conferret, eum morem Terentio Lucano at [005r] tribuere historiographi videntur, qui tribus continuis diebus triginta paria Athletarum confligere mutuis certaminibus more Athletico curavit in palaestra. Quum igitur in locis consuetis pugiles, atque ipsorum discipuli convenissent, ordine sicuti fortes et peritos Athletas decebat, omnis generis arma humi disposuerunt, quod et hodie in usu remansit. Post eorum, nômina papyro inscripta in urnam iniecta sunt, et qui simul educti essent duo aitem una educebantur sine fraude, ii mutuo congrediebantur, atque pro brabeo interse artificiose et more Athletico pugnabant. Quorum alii Herculeum alii Mercurium, alii vero Pollucem et Castorem, et alii alios invocacere, ut sibi in Gymnicis certaminibus contingerent Athletae periti, impolluti, atque ab omni fraude alieni; quaecerta et manifesta sunt iuditia, qui veteres magis propter temperatos moderatosque mores, tum propter ipsam virtutem concertarint, quam ob alias res acquirendas. Quapropter Palestrae concertantium in honorem artis Athleticae, amplis diutius aulis et aedibus necnon ambulacris ornatissime adpingebantur, quique obtinuerint victoriam eleganter descripti: inter quos primas tenuit Neronis libertus, qui palaestras adhibitis Athletis Antii, elegantissime depingi curavit. |

||||

|

So did also the learned philosophers write about this knightly art, and the same were not ashamed to learn its, and among them Pythagoras, who was held a good fencer, was the foremost, as he did win the prize with his artful fencing at the celebration of the 48th Olympiad. Likewise did do many other excellent philosophers, without necessarily naming them all. So does Marcus Tullius Cicero, the Roman mayor and eventually administrator of the entire Roman empire write on the praise of fencing [T. q. folio.125.] I consider and trust entirely that nobody at all can be counted among the number of the learned orators who were not well versed and experienced in all arts that are knightly and even if we do not employ them in speaking, nor is it possible to discern this in us, if we are exercised in knightly sports, but the agility and the bearing of the body does concord and correspond with the agility of the voice, both in cheerful and in lamentable topics, such that it appears all the more agreeable to the listener. This is confirmed by the most learned orator Quintilianus who says that the persons who are given to praise and do not have contempt for the knightly sport of fencing and takes this as the cause that the same have great advantage and furtherance in the art of being well-spoken due to their agility Anacharsis[14] who lived at the time of king Croesus in Lydia, at the time when Rome had stood for 194 years, wrote that he did greatly marvel at how the Greeks were such stern judges while the fencers did bear themselves so heartily and well with[?] open spaces, houses, prizes, treasures and highest praise, as if he would say that the Greeks do well uphold the law and give to each man his due, to one his due praise and to the other his due punishment. Many more similar pronouncements furthering the honour of fencing could be mentioned, but as I feel that no amount would suffice for those who disparage this art, it should suffice for the present time. |

So haben sich auch die Geleerten Philosopi von diser Ritterliche Kunst zu schreiben vnnd dieselben selbs zulernen gar nicht geschemet · vnnder denen Pithagoras · den man fur ein guten Fechter gehabt hat · der erst gewesen sein soll · dann er an dem Fest der XLVIII Olympiadis · mit seinen kunstlichen Fechten · den preiß erlanngt hat · deßgeleichen vil anndere treffennlich Philosophi mer, on nott alle zumelden · gethan haben Marcus Tulius Cicero der Römisch Burgermaister vnnd etwann verwallter des gantzen Römischen Reichs · [006r] schreibet von dem lob des Fechtens also · Ich achte vnnd setze genntzlich · das niemand vnnd gar kainner Inn die zal der gelerten wolredner gerechnet werden soll · welcher nicht in allen kunsten · die den Rittermessigen zugeho°ren · abgericht · vnnd deren erfaren seind · vnnd ob wirs schon vnnder der Red · die nit gebrauchen · noch sicht man vnns solchs an · ob wir Inn Ritterlichen spilen geubt seinn oder nicht Dann die beweglichkait vnnd geberden · des leibs · sich mit der beweglichkait der stimm · In Frölichen oder kläglichen sachen Concordiern vnnd vergleichen · vnnd solches dem zuho°rer vil dester annemlicher erscheinet · Welches der Hochgelert Redner Quintilianus · bestettigt vnnd sagt · das die Personnen · so des Ritterspils des Fechtens sich gebrauchen · zu loben · vnnd gar nicht zuuerachten seien · vnnd setzt dessen vrsach · das dieselben zu der kunst der wolredenhait der beweglichkaithalben ein grossen vortail vnnd furdernus haben · Anarchus · der zu der Zeit Cresÿ · des Kunigs In Lidia · der Zeit als Rom · 194 · Jar gestannden · was · gelebt hat · schreibet · das In groß verwundere Dieweil die Griechen so trefflich Richter seien · vnnd darneben die Fechter · so einannder beschedigen · mit plaetzen · heusern · gewinneter clainnater · vnnd höchstem lob · so herrlich vnnd wol hallten · als wolte er sagen · Die Griechen halten gute Fecht · vnd erziechen Ir Jugent Inn aller manlicher Ritterlicher vbung · die zuerhalltung der Freÿhait diennet · vnnd geben Jedem was sich geburt · baide disem das lob · Jhenem die straff &c Dergleichen spruch so dem Fechten zu Eern furderlich seind · weren noch vil zu beschreiben · bedunckt mich auß vrsachen · das dem Lesterer diser kunst Nimmer guuegsam beschicht · auf dißmals · Inn disem faal gnug sein · |

So haben sich auch die gelerten philosophi von diser rittrerlich kunst zu schreiben, und dieselben selbs zu lernen, gar nicht geschemet, under denen Pithagoras, den man für ein gutten fechter gehabt hat, der erst gewesen sein soll, dann er an dem fest der XLVIII. Olympiadis, mitt seiner künstlichen fechten, den preis erlangt hat, deszgleichen vil andere treffliche philosophi mer, on not alle zumelden, gethan haben. Marcus Tullius Cicero der römisch bürgermaister unnd etwan verwalter des gantzen römischen reichs, scheibt von dem lob des fechtens also.T. q. folio.125. Ich achte unnd setze gentzlich, das niemand und gar kainer, in die zal der gelerten wolredner gerechnet werden soll, welcher nicht in allen künsten, die den rittermessigen zugehören, abgericht [008*v] unnd deren erfaren seind. Unnd ob wirs schon under der red die nit gebrauchen, noch sicht man uns solchs an, ob wir in ritterlich spilen geübt sein oder nicht, dann die beweglichkait und die geberden des leibs, sich mit der beweglichkait der stimm, in fröhlich oder cläglich sache, concordieren unnd vergleichen unnd solches dem zuhörer vil dester annemlicher scheinet. Welches der hochgelert redner Quintilianus bestettigt unnd sagt das die personen so des ritterspils des fechtens sich gebrauchen zu loben unnd gar nicht zu verachten seinen unnd setzt dessen ursach das dieselben zu der kunst der wolredenhait der beweglichkait halben ein grossen vortail unnd fürdernus haben. Anacharsis der zu der zeit Cresii des künigs in Lidia der zeit als Rom 194 jar gestannden was gelebt hat schreiben das in grosz verwundere dieweil die Griechen so strefflich richter seien unnd darneben die fechter so einander beschedigen nit plätzen, heusern, gewinneter, clainater, und hochstem lob, so herzlich und wol hallten als wolte er sagen die Griechen halten gute recht, unnd geben jedem was sich gebürt, baide disem das lob, jenem die straff ·/· Dergleichen sprüch so dem fechten zu eeren, fürderlich seind, weren noch vil zu beschreiben, bedünckt mich aus ursachen das dem lesterer diser kunst nimmer gnüegsam beschicht auf diszmals in disem fall gnug sein ·/· |