|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Johannes Liechtenauer"

| Line 77: | Line 77: | ||

The following concordance tables include only those texts that quote Liechtenauer's Recital in an unglossed form.<ref>The figures are often given as a preamble for the [[gloss]] of [[Lew]], and a fragment of the short sword to the teachings of [[Martin Huntsfeld]], but those instances will not be included below and instead treated as part of those treatises.</ref> Most manuscripts present the Recital as prose, and those have had the text separated out into the original verses to offer a consistent view. For ease of use, this page breaks the general Wiktenauer rule that column format remain consistent across all tables on a page; the sheer number of Liechtenauer sources made this convention entirely unworkable, with more columns empty than filled, so instead the long sword table uses one layout, the mounted and short sword tables use another, and the figures use a third. | The following concordance tables include only those texts that quote Liechtenauer's Recital in an unglossed form.<ref>The figures are often given as a preamble for the [[gloss]] of [[Lew]], and a fragment of the short sword to the teachings of [[Martin Huntsfeld]], but those instances will not be included below and instead treated as part of those treatises.</ref> Most manuscripts present the Recital as prose, and those have had the text separated out into the original verses to offer a consistent view. For ease of use, this page breaks the general Wiktenauer rule that column format remain consistent across all tables on a page; the sheer number of Liechtenauer sources made this convention entirely unworkable, with more columns empty than filled, so instead the long sword table uses one layout, the mounted and short sword tables use another, and the figures use a third. | ||

| − | ''Note: This article includes a | + | ''Note: This article includes a version of Christian Tobler's translation. It was also published in 2021 by Freelance Academy Press as part of ''The Peter von Danzig Fight Book''; it can be purchased in [http://www.freelanceacademypress.com/ThePetervonDanzigFightBook.aspx hardcover].'' |

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| Line 737: | Line 737: | ||

}} | }} | ||

{| class="master" | {| class="master" | ||

| − | + | <tr> | |

| − | + | <th class="FImages0"><p>Images<br/>from the [[Starhemberg Fechtbuch (Cod.44.A.8)|Rome Version]]</p></th> | |

| − | + | <th class="FTobler0"><p>{{rating|A|Featured Translation (from the Rome)}}<br/>by [[Christian Tobler]]</p></th> | |

| − | + | <th class="FNuremberg0"><p>[[Pol Hausbuch (MS 3227a)|Nuremberg Version]] (ca. 1400)<br/>Transcribed by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p></th> | |

| − | + | <th class="FGotha0"><p>[[Talhoffer Fechtbuch (MS Chart.A.558)|Gotha Version]] (1448){{edit index|Talhoffer Fechtbuch (MS Chart.A.558)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p></th> | |

| − | + | <th class="FRome0"><p>[[Starhemberg Fechtbuch (Cod.44.A.8)|Rome Version]] (1452){{edit index|Starhemberg Fechtbuch (Cod.44.A.8)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p></th> | |

| − | + | <th class="FGlasgow0"><p>[[Glasgow Fechtbuch (MS E.1939.65.341)|Glasgow Version]] (1508){{edit index|Glasgow Fechtbuch (MS E.1939.65.341)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Dierk Hagedorn]]</p></th> | |

| − | + | <th class="FKrakow0"><p>[[Goliath Fechtbuch (MS Germ.Quart.2020)|Krakow Version]] (1535-40){{edit index|Goliath Fechtbuch (MS Germ.Quart.2020)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Per Magnus Haaland]]</p></th> | |

| − | + | <th class="FAugsburgb0"><p>[[Rast Fechtbuch (Reichsstadt "Schätze" Nr. 82)|Augsburg Ⅱ Version]] (1553){{edit index|Rast Fechtbuch (Reichsstadt "Schätze" Nr. 82)}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Werner Ueberschär]]</p></th> | |

| + | </tr> | ||

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 04:19, 12 June 2025

| Die Zettel | |

|---|---|

| The Recital | |

| |

| Full Title | A Recital on the Chivalric Art of Fencing |

| Ascribed to | Johannes Liechtenauer |

| Illustrated by | Unknown |

| Date | Fourteenth century (?) |

| Genre | |

| Language | Early New High German |

| Archetype(s) | Hypothetical |

| Principal Manuscript(s) |

|

| Manuscript(s) |

Cgm 1507 (ca.1470)

|

| First Printed English Edition |

Tobler, 2010 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

Johannes Liechtenauer (Hans Lichtenauer, Lichtnawer) was a late-14th century German fencing master. The only account of his life was written by the anonymous author of the Pol Hausbuch, arguably the earliest text in the tradition, and he may have been alive at that time.[1] The text reads:

First and foremost, you should notice and remember that there's only one art of the sword, and it was discovered and developed hundreds of years ago, and it's the foundation and core of all fencing arts. Master Liechtenauer understood and practiced this art completely and correctly; he did not discover or invent it himself (as has been written previously), but rather traveled through many lands and searched for the true and correct art for the sake of experiencing and knowing it.[2]

Liechtenauer was described by many later masters as the "high master" or "grand master" of the art, and authored a long poem called the Zettel ("Recital"). Later masters in the tradition often wrote extensive glosses (commentaries) on this poem, using it to structure their own martial teachings. Liechtenauer's influence on the German fencing tradition as we currently understand it is almost impossible to overstate. The masters on Paulus Kal's roll of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer were responsible for most of the most significant fencing manuals of the 15th century, and Liechtenauer and his teachings were also the focus of the German fencing guilds that arose in the 15th and 16th centuries, including the Marxbrüder and the Veiterfechter.

Additional facts have sometimes been presumed about Liechtenauer based on often-problematic premises. The Pol Hausbuch, often erroneously dated to 1389 and presumed to be written by a direct student of Liechtenauer's, has been treated as evidence placing Liechtenauer's career in the mid-1300s.[3] However, given that the Pol Hausbuch may date as late as 1494 and the earliest records of the identifiable members of his tradition appear in the mid 1400s, it seems more probable that Liechtenauer's career occurred toward the beginning of the 15th century. Ignoring the Pol Hausbuch as being of indeterminate date, the oldest version of the Recital that is attributed to Liechtenauer was recorded by Hans Talhoffer in the MS Chart.A.558 (ca. 1448), which further supports this timeline.[4]

Contents

Treatise

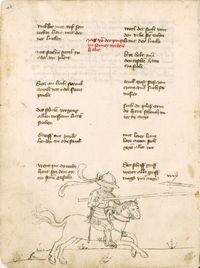

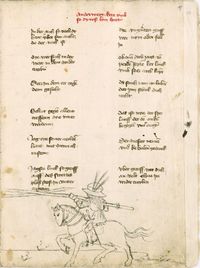

Liechtenauer's teachings are preserved in a long poem of rhyming couplets called the Zettel ("Recital"), covering fencing with the "long" or extended sword (i.e. with both hands at one end of the sword), the "short" or withdrawn sword (i.e. with one hand at either end), and on horseback. These "obscure and cryptic words" were designed to prevent the uninitiated from learning the techniques they represented; they also seem to have offered a system of mnemonic devices to those who understood their significance. The Recital was treated as the core of the Art by his students, and masters such as Sigmund ain Ringeck, Peter von Danzig zum Ingolstadt, and Lew wrote extensive glosses that sought to clarify and expand upon these teachings.

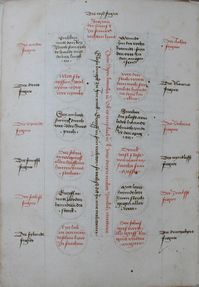

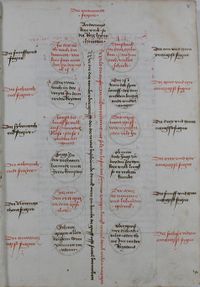

In addition to the verses on mounted fencing, several treatises in the Liechtenauer tradition include a group of twenty-six "figures" (figuren)—phrases that are shorter than Liechtenauer's couplets and often arranged into the format of a Medieval tree diagram. These figures seem to encode the same teachings as the verses of the mounted fencing, and both are quoted in the mounted glosses. However, figures follow a very different structure than the Zettel does, and seem to present an alternative sequence for studying Liechtenauer's techniques. It is not known why the mounted fencing is the only section of the Recital to receive figures in addition to verse.

Seventeen manuscripts contain a presentation of at least one section of the Recital as a distinct (unglossed) section; there are dozens more presentations of the verse as part of one of the several glosses. The longest version of the Recital by far is actually found in one of these glosses, that of Pseudo-Hans Döbringer, which contains almost twice as many verses as any other; however, given that the additional verses tend to either be repetitions from elsewhere in the Recital or use a very different style from Liechtenauer's work, they are generally treated as additions by the anonymous author or his instructor rather than being part of the original Recital. The other surviving versions of the Recital from all periods show a high degree of consistency in both content and organization, excepting only the much shorter version attributed to H. Beringer (which is also included in the writings of Hans Folz).

The following concordance tables include only those texts that quote Liechtenauer's Recital in an unglossed form.[5] Most manuscripts present the Recital as prose, and those have had the text separated out into the original verses to offer a consistent view. For ease of use, this page breaks the general Wiktenauer rule that column format remain consistent across all tables on a page; the sheer number of Liechtenauer sources made this convention entirely unworkable, with more columns empty than filled, so instead the long sword table uses one layout, the mounted and short sword tables use another, and the figures use a third.

Note: This article includes a version of Christian Tobler's translation. It was also published in 2021 by Freelance Academy Press as part of The Peter von Danzig Fight Book; it can be purchased in hardcover.

Gotha Version (1448) |

Rome Version (1452) |

Copenhagen Version (1459) |

Wolfenbüttel Ⅰ Version (ca. 1465-80) |

Munich Ⅰ Version (ca. 1470) |

Vienna Version (1480s) |

Dresden Version A (ca. 1504-19) |

Dresden Version B (ca. 1504-19) |

Krakow Version (1535-40) |

Munich Ⅱ Version (1523) |

Augsburg Ⅰ Version (1523) |

Glasgow Version (1533) |

Augsburg Ⅱ Version (1553) |

Munich Ⅲ Version (1556) |

Wolfenbüttel Ⅱ Version (ca. 1588) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[1] The Record[6] of the chivalric art of fighting, which was composed and created by Johannes Liechtenauer (God rest his soul),[7] grand master of the art, begins here: first with the extended sword,[8] then with the lance and sword on horseback and with the retracted sword in the duel. Since the art belongs to princes, lords, knights, and soldiers, and they should learn and know it, he allowed this art to be written down. But because of frivolous fencing masters[9] who would trivialize the art, it’s written in obscure and cryptic words[10] (as you’ll find written below) so that not just anyone will learn or understand it, and that way those masters can’t make his art common or open among people who won’t treat it with proper respect. |

[1] Here Begin the Notes on the Knightly Art of Combat That Was Composed and Created by Johannes Liechtenauer, Who Was A Great Master in the Art, God Have Mercy on Him; first with the long sword, then with the lance and sword on horseback, and then with the shortened sword in armoured combat. Because the art belongs to princes and lords, knights and squires, and they should know and learn this art, he has written of this art in hidden and secret words, so that not everyone will grasp and understand it, as you will find described below. And he has done this on account of frivolous fight masters who mistake the art as trivial, so that such masters will not make his art common or open with people who do not hold the art in respect as is its due. |

[1] |

[1] |

[18r.1] Hye hebt sich an meister liechtenawers chunst Deß lengen swerts Anno domini xlviij Jar etc |

[03r.1] Alhÿe hebt sich an dye zedel der Ritterlichen kunst des fechtens dye do geticht vnd gemacht hat Johans Liechtenawer der ain hocher maister In den künsten gewesen ist dem got genadig seÿ |

[104v.1] [A]lhie hebt sich an die zetl der ritterlichen chunst des fechtens die geticht vnd gemacht hat hanns liechtenauer der ein hocher maister in den künsten gewessenn ist dem got genadig sey des ersten mit dem lanngen swert darnach mit dem spies vnd darnach mit dem swert zw ross vnd darnach mit dem kurczen swert zw ross kampf vnd dar vmb das die kunnst fürsten vnd herrenn rittern vnd chnechten zw gehort das sy wissenn vnd lernen sullenn so hat er die ritterlichen chunst yedleich pesunder lassen schreibenn mit verporgen vnd verdackten worten dar vmb das Sy yeder man nit versten müg vnd hat das getan durch der schirmmaister willen die ir chunst ring wegen das von den selbm sein chunst nit geoffenwart werd lewtten die die chunst nicht in wierden chünen haldenn als den chunnsten zue gehört |

[03r.1] JN sant Jörgen namen höbt an die kunst deß fechtens die gedicht vnd gemacht hat Johanns liechtnawer der ain hocher maister In den kunste~ gewesen ist dem gott genädig sÿ Deß ersten mitt dem langen schwert Dar nach mitt dem spieß Vnnd dem schwert zu° roß Vnnd och mitt dem kurczen schwert zu° dem kampf als her nach geschriben stat ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[2] The Preface[11][12][13][14]

|

[2] This is the Prologue

|

[2] |

[2] |

[18r.2] Junck ritter lere |

[03r.2] Das ist dy vor red Junck ritter lere |

[Ⅲr.1] Junck ritt° leren |

[45r] Junger Ritter lern |

|

[03r.2] Jüngk ritte~ lere / |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[3] This is a General Teaching of the Long Sword

|

[3] Talhoffer teaches here a general teaching about the long sword from the Zettel, etc.

|

[3] A general lesson in the Long Sword.

|

[18r.3] Das ist eyn gemeine ler des swertz etc wiltu kunst schawen |

[03v.2] Das Ist ein gemaine ler des langen Swerttes ·:~Wildu kunst schauen |

[02r.1] Hie lert der talhofer ain gemaine ler in dem langen Schwert von der zetel etc. Wiltu kunst schowen |

[Ⅲr.2] ¶ Wiltu kunst schawe~ |

[104v.3] Das ist ein gemaine ler des langenn Swercz vnnd ist das die vor redt [W]Ild dw chunnst schauen |

[03v.2] Das ist ain gemain lere des langen schwerts Wilt du kunst schawen |

[01r] Ein gemayne ler des lanngen Schwertz Wildu kunst schauen, |

[43r.1] Ein gutt gemain for des langen schwerts Wilstu kunst schawen |

[42br.1] Ein gutt gemain ler des langen schwertz Wilttu kunst schawen |

[48r.1] Ein gutte gemaine lesr des langen schwerts Wiltu kunst schauwen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[4]

|

[4]

|

[4]

|

[18v.2] funf hew leren |

[03v.3] ffünff häw lere |

[02v.1] Die tailung der kunst nach dem text den nähsten weg zuo dem mann zuo schlahen oder zuo stossen Zorn how du krumo wer |

[Ⅲr.3] ¶ ffunff haw dei leren |

[104v.4] funff hew lern |

[04v.2] Fünff hew lere |

[01v.2] Funff hewe lere |

[43r.2] funnf haw lernen |

[42br.2] funnff hew lernen |

[48r.2] und 5 hauw lehrnen, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[5] This is the text:

|

[5] The division of the art according to the text the nearest path to strike or to thrust at the man

|

[5] Text on the recital's parts

|

[18v.3] Das ist der text an dy außlegu~g Zoren hawe kru~p twirg czorn haw ort Im drvet Wirt er eß gewar ny~ obñ ab anefar biß starck hin wider wint stich sicht erß ny~ eß nÿder das ebñ merck haw stich leger weich oder hert In deß vnd var vnd nach an hurt den krieck sey nicht czu gahe etc Das ist der krieck Was der krieck remetobñ nyder wird beschemet In allñ winte~ hawe stich snytt ler winde~ auch soltu mit prufe~ haw stuch oder snyt In allm~ treffen dÿe meister wiltu sye effñ |

[04r.2] Der zoren haw ·W·er dir öberhäwtzorenhaw ort dem drawt wirt er es gewar Nÿm oben ab öne far Piß starck her wider wind stich sicht leger waich oder hers nÿm es nyder Das eben merck haw stich leger waich oder hert Inndes vnd var nach an hürt Dein krieg sey nicht gach oben nÿden wirt er beschempt In allen winden Haw stich schnÿdt lere vinden Auch soltu mit prufen Haw stich oder schnÿd In allen treffen den maisteren wiltu sy effen ~ Dÿe vier plossen Vier plössen wisse |

[02v.2] Das ist von dem zornhow der underschid wer dier uberhowtzornhow ortt dem trowt und wirt erß gewar Nymß obnen ab vnd folfar biß stercker wind wÿder stich sicht erß // so nymß nider daz also eben merck Ob sin leger sy waich oder hört Jn dem far nach hört an krieg sy dir nit gauch der wirt obnen nider geschempt du machst in allen hewen winden Im how ler stich vinden ouch soltu mit mercken stich oder schnit In allen treffen wiltu den maister effen |

[Ⅲr.4] Tarnhaw kru~phaw thwere wen dir oben hauwz Tzoharnort em drowz wert er es gewar Nym es oben ane var wys starck wid° en wir° stich schicher ny~ es nyden Das eben merke vñ warte haw stich s leg° weich od° harte — Indes far nach An hurt dein krig sey nich gach Obin nider wirt veschempt ¶ In allen winden hau stich ler en vinde~ In allen zu dreffen Dey meisters wiltu sey effen |

|

[104v.5] [Z]orn haw twer zorn ort dem trät wirt er es gewar nym oben ab ame [!] far pis stercker wider windt stich sicht ers nym es nyder das eben merck haw stich leger waich oder hert Inndes vnd far nach an hurt dein krieg sey nit gach oben nyden wirt es verschemet in allen winden Haw stich schnit lere finden auch sold dw nit [!] prüffen hew stich schnit in allenn treffen den maistern wildw sy affenn |

[04v.3] Das ist der texte Zorn hawe krumpt were [05r.1] Nÿm oben ab an far / biß störcks storckñ wider wennde sthich / sicht er es nÿm es nider Daß eben mörcke Haw° sthich leger waich ode~ hörte In des Vnnd far nach an herte dein krieg sÿ mnitt gach oben In den wirt er beschemet In allen treffen den maister wilt du sÿ effenn In allen winden Hew° st stich schnitt lern finden Auch solt du mitt briefn brieffe hew stich oder schnitt ~ ·:· ~ Die vier blossen zu° breche~ Vier blossen wisse |

Zornhaw° Im [56r.1] drawet Wirt er daß gewar / nims oben ab vnd far Biß störcker wider / wind such sicht ers so nÿms wider Das eben mörck / hew° stich / leger / waÿch oder hert In allen winden / hew° / stich / lern finden Vier blöß wiß dich zu° remen So schlechst du gewiß |

[01v.3] Text von denn Stucken der Zetl Zornnhaw, Krump, Twir,

[02r.1] Wer dir oberhaut

Zonhau[!] ort dem drawt, Wirt er es gewar Nim oben ab öne far Piß starck herwider Wind stich sicht ers nim es wider Das ebenn merck Hau stich leger waich oder hert Inndes und var nach an hurt dein krig sei nich gach oben niden wirt er beschempt In alln winden. Haw stich schnidt lerre finden, auch soltu mit prüsen[!] hau stich oder schnÿd in alln treffen den maistern wiltu sie effen |

[43r.3] Das ist der text und die auslagung der schaittler Zornhaw krumphaw zwerch Zornortt ein darott Ser wider wind stich sichters so nim es nider das eben merckh haw stich legr waich oder hörtt Indes vor und nach dem krieg seÿ dir nit gach der wirtt oben ösche[ ]tt In allen winden haw und f[ ] stich [43v.1] Schneide finden auch so soltt du nit nieden hau stich schneide zuckg in alem treffen wiltu den maister Effen |

[42br.3] + Das ist der text vnd die auslegung der schaitler Zornhaw krumphaw zwerch zornortt ein dratt herwider wind stich sicht ers so nim es wider das eben merckh haw stich legr~ waich oder hörtt Indes vor vnd nach dein krieg seÿ dir nit gach der wirtt oben bschemett In allen winden haw vnd stich schneide finden auch so soltt du nit meiden haw stich schneide zuckh in allem treffen wilttu den maistr~ Effen |

[15r.1] Der zornhaw Wer dir vberhaut,zornhaw, ort dem traw, wirt er es gewar nym oben ab ane vor, bis sterckher wieder wind stich sicht er es, nym es nyder, das oben merckh, haw stich beger weich oder hert jm des, vnnd vor nach an hurt dem krieg sey nit gach, oben Nider wirt er beschemet, jn allen winden, haw stich schnite leere winden, auch soltu Brrueffen, mit hawe stich oder schnite, jm allem treffen, den maistern wilt du si treff Effen, Die vier plössen, Vier plösse,,,,wisse |

[48r.3] Das ist der tex und die aus richtung der schaitter Zornhauw, krumhauw, Zwerch zornortt, im tritt herwider windt sticht sicht was so nim es wider dz eben merkh hauw. stich leger waich oder hart in dz vor und nach dem krieg sei dir nit gach der wirt oben beschemet in allem windt hauwe und stich schneidt finden auch so soltu nit meiden, hauw stich schneiden zuckh in allen trefen wiltu dem maister essen. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[6] The Wrath Stroke

|

[6] This is the distinction about the Wrath cut[97]

|

[6] -Zornhau Follows-

|

[19r.1] Das ist võ den vier ploßenn Vier ploß wiß |

[04r.3] Dye vier plossen zw prechen Wildu dich rechen |

[03r.1] von den vir plößen vier plöß wisse |

[Ⅲr.5] ¶ Veyr blos dey wisse |

[62r] Vier blosse wisze |

[104v.6] die vier plossenn [V]Ier plosse wisse |

[56r.2] Wilt du dich rechen / |

[02r.2] Die vir Ples Vier Plössen wisse |

[43v.2] Das ist von den vier blössen Die einer blöss wis |

[42vb.1] Das ist von den 4 blösen + Die vier blöss wisse |

[48r.4] Das ist von den 4 blossen Die 4 blos wiss |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[7] The Four Openings

|

[7] About the four exposures

|

[7] The Four Openings

|

[19r.2] Das ist wie mã dÿ vier ploßenn sol prechñ Wiltu dich rechenn |

[04r.4] Der krump haw Krump auff behende |

[03r.2] Die vier plöß brechen wiltu dich rechen |

[Ⅲr.6] wiltu dich rechen |

|

[104v.7] wild dich rechen |

[05v.2] Die vier blossen zu° brechen Wilt du dich rechen |

[56r.3] Krump vff behende / |

[02v.2] Die vir Plössen zu prechen Wildu dich rechen |

[43v.3] Das ist wie man die vier blöss brechne sol Wilstu dich Rechen |

[42bv.2] + Das ist wie man die 4 blöss brechen sol Wilttu dich Rechen |

[15r.3] Der krumbhaw Krumb auff behende |

[48r.5] Das ist wie man die 4 blos brechen soll. Wiltu dich rechen, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[8]

|

[8] To Counter the Four Openings

|

[8] Breaking the four exposures

|

[8] Breaking the four Openings

|

Das ist vom chrump haw dÿ außrichtu~g chru~p auff behendt |

|

von krumen // wie die schnyd da kummen werff. krum uff sin hende |

¶ krum uff bohe~de |

[66v] krumpf auf Behende |

[K]rump auf Behende |

Der Km Krumphaw° Krump vff behende |

[56v] dich Irrt / |

Krumphau Krump auff behende |

Das ist die ausrichtung vom krumphaw Krumphaw auff behend |

+ Das ist die ausrichtung vom krumphaw Krumphaw auff behend |

|

Das ist die ausrichtung vom krummhauw[121] Krum hauw auf behend, |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[9] The Crooked Stroke

|

[9] About the Crooked [cut]; how the slices come from there

|

[9] Arc Strike

|

Das ist võ twi°g haw dye außrichtu~g Twirg benymet |

Der twer haw Twer benympt Schiler ain pricht |

[3v] Die tailung der kunst nach dem text den Rechten weg und die uß richtung der zwierhin Die zwierh benympt Schylher ain bricht |

Twirch bonimpt |

|

Der twer haw [T]wer[138] benimpt |

Der zwerchhaw° Zwerch benimpt |

Zwerch benimpt / |

Twerhaw Twer benimpt |

Die ausrichtung vom Zwerchhaw Die Zwerchhaw benimptt |

+ Die ausrichtung vom zwerchhaw Die zwerchhaw benimpt Schilcher enibricht |

Der Twer haw Twer benymbt, Schiller einpricht, |

Die ausrichtung vom zwerchauw Die zwerchauw nimpt Scheleher einbricht |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[10] The Thwart Stroke

|

[10] The division of the art according to the text about the right way, and the instruction about the Cross-wise cuts

|

[10] Cross Strike

|

[19v] Das ist võ schilhaw dy außrichtu~g Schiler enpricht |

Der schaittelhaw Der scheitlar |

Der scheitler |

der schilhaw [Sch]ilcher ein pricht |

Der schilhaw° Schiller In bricht |

Der schaittler |

Schilhaw Schiler am[!] pricht |

Die ausrichtung vom schilthaw Schilchr ein bricht |

|

Der scheitler Der sheitler |

Die ausrichtung vom schaitelhauw. Der schaitler |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[11] The Squinting Stroke

|

[11] This is the instruction about the Squinter cuts

|

[11] Glance Strike

|

Das ist võ dem schilthaw dy außrichtu~g Der scheÿtler |

|

Daz ist von dem schaittler Die ussrichtung etc. Der schaittler |

¶ veir leger alleyn |

[D]er schaitler |

Der schaittelhaw° Der schille~ |

Vier leger alain |

Schaittelhau [04r] Der scheitler |

Die ausrichtung von dem schaitelhaw Der schaitler |

[43r] + Die ausrichtung von dem schaitelhaw Der schaitler |

|

Die ausrichtung von den 4 legern Die 4 leger allain |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[12] The parter

|

[12] The Scalp Cut

|

[12] Vertex Strike

|

Das ist von den vier leger dÿ außrichtung Vier leger alben |

Dÿe vier leger Vier leger allain |

von den vier leger Vier leger alain |

¶ veir sint vorsetzen |

[58r] Die erste hute haist der ochse |

Die vier leger [V]ier leger allain |

Die vier leger Vier leger allain |

Vier sÿnd der vorseczen / |

Vir leger Vir leger allain |

Die ausrichtung von den vier legern Die vier leger allain |

+ Die ausrichtung von den vier legern Die vier leger allain |

Die vier leger Vier Leger allein, |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[13] The Four Guards

|

[13] Four stances

|

Das ist võ den vier versetze~ dy außrichtung Vier sint der vor seczen |

Dye vier vor Setzen Vier sind vor setzen |

von den vir versetzen vier sind versetzen |

nachreisen lere |

Die vier verseczenn [V]Ier seind der verseczen |

Die vier verseczen Vier sind verseczten |

[57r] leczen |

Vier vörsetzen [04v] Vir seind vörsetzen |

Die ausrichtung von den vier versetsen Vier sind der versetsen |

+ Die ausrichtung von den vier versetzenn Vier sind der versetzen |

Die vier versecz[en] Vier sind verseczen, |

[49r] Die ausrichtung von den 4 versetzen Vier seind der versetzen, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[14] Displacement

|

[14] The Four Oppositions

|

[14] About the four counteractions

|

[14] Four displacements

|

Das ist võ dem nach reÿse~ dÿ außrichtu~g Nach reyßenn lere |

Von Nach Reÿsen N·ach raisen lere |

wer vnde~ ramz // |

|

von nachraisen nach raissenn lern |

Von Nachraÿsen Nachraÿsen lere / |

Nachraÿsen lere / |

Nachraisen Nachraisen lere |

Von dem Nachraisenn Nachraisen lere |

+ Von dem nachRaisen Nachraisen lere |

Von Nachraisen, Nachraisen Leere, |

Von dem nachraisen Nachraisen lehren |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[15] Pursuit

|

[15] Chasing

|

[15] This is about the chasing

|

[15] Following After

|

[20r] Von vber lauff dy außrichtu~g ~Wer vndenn remet |

von überlauffen ·W·er vnnden rempt |

von dem überlouffen wer des lybß unden remet |

ler aff setze~ // |

Von vberlauffenn er vnden rempt |

Von v°berlauffen ~ [08r] Wer vnden rempt / |

Wer vnden remet / |

Uberlauffen Wer unden rempt |

[44v] Das die ausrichtung von dem uberlauffen Der unden Remet |

Die ausrichtung von dem l vberlauffen Der vnden Römett |

Von vberlauffen, Wer vnnden remet |

Die ausrichtung von dem uberlauffen Der unden renet |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[16] Overrunning

|

[16] Overrunning

|

leren abseczenn |

Von absetzen Lere absetzen |

vom absetzen kanstu die rechtn absetzen |

Dorch wessel lere |

von abseczenn Lern ab seczenn |

Von abseczen Lere abseczen |

Lern abseczen / |

Absetzen Lere absetzen |

Die ausrichtung von dem absetsen Lere absetsen |

+ Die ausrichtung von dem absetzen Lere absetzen |

[16v] Von abseczen, Leere abseczen, |

Die ausrichtung von dem absetzen Lehren absetzen |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[17] Setting Aside

|

[17] Parrying

|

Das ist võ durch wechsel dy außrichtu~g Durch wechsel lere |

Von durchwechselen Durchwechsel lere |

vom durch wechsel Durchwechsel lere |

Drit nachet i~ binden |

[66r] Dúrchwechsel lere |

Vom durchwechsl Durch wechsel lere |

Von durchwechslen Durchwechslen lere / |

Durchwechsel lere / |

[05v] Durchwechseln Durchwechsell lerre |

Von dem durchwechsell Der durchwechsel lere |

[43v] + Von dem durchwechsel Der durchwechsel lere |

Von Durchwechsel, Durchwechsel Leere, |

Von dem durchwechsel Der durchwechsel lehren |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[18] Changing Through

|

[18] About the changing through

|

[18] Changing Through

|

Das ist võ zuckenn dy außrichtu~g Trit nahent In bunde |

von zucken Trit nahent Inn pinden |

vom zucken alle treffen tuo nahet eyn binden |

Dorloff das hange~ |

Von zuckenn drit nachet in punndenn |

[08v] von Zucken Tritt nahent Inbinden / |

|

Zucken Trit nahent in pinden |

Die ausrichtung von dem Treffn und Zuckn Dritt mein die binden |

Die ausrichtung von dem treffen vnd zuckhe[n] Dritt nein die binden |

Von zucken, Trit nahendt in pinde, |

Die ausrichtung von treffen, treffe und zukhen Tritt man die binden |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[19] Pulling

|

[19] About pulling all hits

|

[19] Disengaging

|

Das ist võ Durch lauffung dy außrichtu~g Truckdurch//lauffñ |

von Durchlauffen Durchlauff las hangen |

vom durch louff Durch louff lauß hengen |

Snid aff dei hertzen |

von zwain hengen von durchlauffen

|

von durchlau°ffen Durchlauff laß hangen |

|

Durchlauffen [06r] Durchlauffen las hangen |

Die ausrichtung von dem durchlauffen Durchlauff las hengen |

+ Die ausrichtung von dem durchlauffen Durchlaüff lass hengen |

Von Durchlauffen, Durchlauff laß hangen, |

Die ausrichtung von dem durchlauffen [49v] Durchlauffen las langen |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[20] Running Through

|

[20] About the running through

|

[20] Charging Through

|

Das ist võ ab sneydenn dÿe außrichtu~g Sneyd ab dy hertt |

von abschneiden Schneid ab dÿ herten |

vom abschniden Schnid ab die hörte |

|

|

von durchlauffenn durchlauf laß hangen |

von abschnÿden Schnid ab die hertt~ / |

Schnÿd ab die hört |

Abschneiden Schneit ab die Hertten, |

Die ausrichtung von dem abschneiden Sschneidt ab die hertte |

Die ausrichtung von dem abschneiden Schneid ab die hörtte |

Von abschneiden Schneid ab die hannd, |

Die ausrichtung von dem abschneiden Schneid die hänte |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[21] Slicing Off

|

[21] About the slicing off

|

[21] Cutting Off

|

Das ist võ hent truckñ dy außrichtu~g

|

von hend drucken [6r] |

vom hennd trucken

|

|

sneid ab die herten |

[09r] von hende trucken

|

Hend druckhen.

|

Von dem hend truckhen Das schwertt bind |

+ Von dem hendt truckhen Das schwertt bind |

Von hennd truckhen,

|

Von den hend trucken Das schwert binden |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[22] Pressing Hands

|

[22] Hand hitting

|

Das ist võ czweÿen henge~ dy außrichtu~g

|

von tzwaien hengen

|

von den zwain hengen wer dir zestarck welle sin |

¶ Spreck vinster mache |

|

von zwaÿen hengen

|

[06v] Zwei henngen

|

Von den Zwaien hengen die ausrichtung

|

Von den zwaien hengen die ausrichtung

|

[17r] Von zwayen hengen

|

Von den 2 hengen die ausrichtung

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[23] Two Hangings

|

[23] About the two hangings

|

[23] Two Hangings

|

[20v] Das ist võ sprech fenster dy außrichtu~g Sprech venster mach |

von sprechfenster Sprechfenster mach |

von sprech venster Sprechfenster mache |

wer wol bricht // |

[70v] Sprechfinster[!] mach |

sprechfenster mache |

von sprechfenster Sprechfenste~ mach |

Sprechfennster Sprechfennster mach. |

[45r] Von dem sprechfenstr die ausrichtung Das sprechfenster machen |

Von dem sprechfenstr~ die ausrichtgung Das sprechfenster machen |

Von Sprechvenster Sprechvenster machen, |

Von den sprechfenster die ausrichtung Das sprechfenster mach |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[24] The spreading window[230]

|

[24] The Speaking Window

|

[24] About the spreading[238] window

|

[24] Window Breaker

|

Das ist dy beslißu~g der gancze~ kunst Wer wol pricht |

Das ist die beschliessung der zedel Wer wol fürt vnd recht pricht |

Die besliessung der zetel wer wol bricht |

Et[c] & finis |

besliessúnge der gantzen zettel |

der zetl pesliessung [W]er wol fueret vnd recht pricht |

[09v] Die beschliessung der zedel Wer wol füret Vñ recht bricht |

.Bßießung[!] der Zetl. Wer woll furt, unnd recht bricht |

Das ist die ausrichtung und die beschliesung der grunsn kunst wer vol sicht |

Das ist die ausrichtung vnd bschliesung der gantzen kunst wer wol sicht |

Das ist die beschliessung der zetl Wer wol furet vnd recht bricht, |

Das ist die ausrustung und die beschliessung de gantzen kunst, wer wol ficht |

Images |

Nuremberg Version (ca. 1400) |

Gotha Version (1448) |

Rome Version (1452) |

Glasgow Version (1508) |

Krakow Version (1535-40) |

Augsburg Ⅱ Version (1553) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Figures of the Fight on Horseback |

[165v.1] Figuren des Roßfechtens |

||||||||||

Direct your spear etc, If it falls etc, Strike in, don't pull, etc. Gloss: Pull to his left, grasp in his right, so you catch him there without fencing. |

[07v.1] Dein Sper bericht etc Ob es emphal etc Haw dreyn nichtt Zuckch etcettera Glosa lingck zu Im ruck · Greyff in sein rechten · so vechst du In ane vechttenn |

[18r.14] Dein sper bericht &c wer es entfalle, den end im abschnalle. Hau drein nicht zuckhe, glest linkh &c vnd fach sein rechte. | |||||||||

The 1st Figure: Charge from the breast to his right hand. |

[22v.1] Jag võ der prust zu seiner rechtñ hant |

[07v.2] Die erst figur Jag von der prust zu seiner rechten hand |

[74r] 1 Jag von deiner prust zw seiner rechten handt |

[165v.2] Jag vonn der rechten brust, zu seinner rechtn hannt.~ |

[18r.1] Jag von derr prust zu seiner recht handt | ||||||

The 2nd Figure: Turn around with the horse, pull his right hand with your left. |

[53r.10] ·greif im seyn rechte · |

[22v.2] vmbker mit roß sein rechte hant mit deyner lincken |

[07v.3] Die ander figur Vmbkere mitt dem Rozz Zewch sein rechte handt mitt deiner lingken |

2 Vmb ker mit dem roß / zeuch sein rechte handt mit deiner lincken |

[165v.23] Umbkere mit dem roß zeuch sein rechte hannt mit deiner lincknn |

[18r.2] Vmbker mit dem Roß zeuch sein recht hand mit deiner linkhen | |||||

The 3rd Figure: Upon the encounter, take the stirrup-strap or the weapon. |

[22v.3] mit stechñ satel In oder ver plent |

[07v.4] Die dritt figur Mitt strayffen Satel ryem · oder wer nymbe |

3 Mit Straÿffen satel riem / oder wer nymbt |

[165v.4] Mit straiffenn sattel ryem oder wer nimpt |

[18r.3] Mit streffen satel rien[g] oder were Nymbt, | ||||||

The 4th Figure: Plant upon him high, swing, go through or break the sword. |

[53r.8] Wiltu abesetzen · |

[22v.4] Secz an hoch swenck durch var oder swert pricht |

[07v.5] Die vyerdt figur Setz an hoch swing durch var · oder Swert prich |

4 Setz an hoch / schwing / durchfar / oder schwert prich |

[165v.5] Setz ann hoch schwing durch var oder schwert prich |

[18r.4] Secz an, hoch schwing durch vor oder schwert pricht | |||||

The 5th Figure: The defense precedes all meetings, striking, or thrusting. |

[22v.5] des schute~ vorgeng allen treffenn hawe~ stechen |

[07v.6] Die funfft figur Daz schuten vorgenngk allen treffenn hawen vnnd stechen |

5 Das schutten / vor geng allen treffen / hawen stechen |

[165v.6] Das schutten vorgenngk allenn treffenn hauenn und stechenn |

[18r.5] Das Schutten volg genckh allen treffen hawen vnd stechen | ||||||

The 6th Figure: Take the strong with both hands. |

[22v.6] Greiff mit peyde~ henden an dye strick |

[07v.7] Die sechst figur Greyff an mitt payden henndten die sterck |

6 Greyff an mit paiden henden die sterck |

[165v.7] Greiff ann mit paiden henden die sterck |

[18r.6] Greiff an mit baiden, henden, die sterkh, | ||||||

The 7th Figure: Now begin to seek the opponent with the Slapping Stroke. |

[22v.9] Hye hebt mã den tasche~ hawe czu such |

[07v.8] Die sybendt figur Hie heb an den mann taschen haw zu suechen |

7 Hie heb an den man taschen haw zw suechen |

[165v.8] Hie heb ann dem mann taschenn hau zu suchenn |

[18r.7] Hie heb an, den mann dass er fare zu suchen | ||||||

The 8th Figure: Turn his right hand, set the point to his eyes. |

[22v.7] Went Im dy recht hant secz dein ort czu seine~ gesicht |

[07v.9] Die Achtt figur Wenndt Im die recht hanndt · setze den ortt zu den augen sein |

8 Went im die recht handt setz dein ortt zw seinem gesicht |

[165v.9] Wennt im die recht hannt setze den ort zu denn augenn sein |

[18r.8] Wend jm die recht hannd secz im den ort zu den augen sein | ||||||

The 9th Figure: Who defends against the thrust, grasp his right hand in your left. |

[22v.8] weyl der stich wert den vahe sey~ rechte hant dey~ lincke |

[07v.10] Die Newnt figur Wer den stich wertt dem vach sein rechte handt in dein lincken |

9 Wer den stich went dem vach sein rechte handt in dem glincke / |

[165v.10] Wer denn stich weret dem vach sein rechte hannt mit deiner linckn |

[18r.9] Wer den stich wert dem fach sein rechten hand in dein linckhe, | ||||||

The 10th Figure: Seek the openings: arms, leather, gauntlets, under the eyes. |

[22v.11] such dy ploß arm dÿ hant scheuch vnter dÿ auge~ |

[07v.11] Die Zechent figur Suechee die ploss arm leder hanndtschuech vndtir den augen |

11 Suech die plos arm~ leder handt schuech vndter den augen |

[165v.11] Such die plös arm leder handschuh unnther den augenn |

[18r.10] Such die ploß arm lert hand stich vnder die augen | ||||||

The 11th Figure: Press hard, push from the reins and seek his messer. |

[55r.13] Drük vast mit stössen · |

[22v.10] truck vast stoß von czam vnd such sey~ meßer |

[07v.12] Die ayndlifft figur Druck vast stoss von tzawm · sueche sein Messer |

10 Drück vast stoß vom zaüm vnd suech sein messer |

[165v.12] Druck vast stoß vonn zaum suche sein messerr |

[18r.11] Druckh vast stoß vom zaum vnd such sein messer | |||||

The 12th Figure: With the empty hand learn two strokes against all weapons. |

[22v.12] mit lerer hant lere czwen stich gege~ aller wer |

[07v.13] Die Zwolfft figur Mitt lerer hanndt lere zwen strich gegen aller were |

12 Mit lerer handt lern straich gegen aller were / |

[165v.13] Mit lerer hant lere zwen streich gegn der wer |

[18r.12] Mit leerer hand leer zwen straich gen allen wöhr, | ||||||

The 13th Figure: The Sheep Grip defends against all wrestling grips under the eyes. |

[55r.3] Der schofgriff / weret · [57v.2] Der schofgrif mit lobe · |

[22v.13] Der schaff griff weret alle griff rings vnt° augñ etc |

[07v.14] Die dreitzechent figur Der schaf grif wertt · alle griff Ringens vndter augenn |

[74v] 13 Der Schaffgriff werdt alle griff ringes vndter auge~ |

[165v.14] Der schopfgrif weret alle grif ringenns unnther augenn |

[18r.13] Der schaffgriff wört alle griff ringens vnder augen, | |||||

The 14th Figure: Turn around again to where the horses hasten. |

[23r.1] Anderweyt kere vmb so dy roß hin hurtñ |

[08r.1] Die viertzendt figur Anderwayd kere vmb · so die Rozz hynn hurtten |

14 An der weidt ker vmb / so die roß hyn hurttñ / |

[165v.15] Ann der weit kere umb so die ros hin hurtenn |

[18v.1] Ander weit ker vmb so dir Ross hin hurtten, | ||||||

The 15th Figure: Up close, catch the hand, turn over his face to where the nape is. |

[23r.2] In der auch so vach dy hant v°ber sein antlicz do der nack ist |

[08r.2] Die funfftzend figur In der nech vach die hanndt · verkere sein anttlitz da der nack ist |

15 In der nech fach die handt verker sein antlutz do der nacke ist |

[166r.1] Inn der nehe vach die hant verker sein antzlig do der nack ist |

[18r.2] Im der nch vach die hand, verker sein antlicz do sein nackh ist, | ||||||

The 16th Figure: Catch the weapon from afar while you ride against him. |

[23r.3] dye wer fach in der weyt in dem wider treibñ |

[08r.3] Die sechtzechend figur Die were vach in der weytt · In dem wider Reytten |

16 Die weer fach in der weitt in dem wider reÿttñ |

[166r.2] Die were vach in der weit in dem widerreittenn |

[18r.3] Die wöhr vach jm der weit Im dem wider raiten | ||||||

The 17th Figure: If you charge to the left, then fall to the sword pommel, jab under the eyes. |

[23r.7] Jagstu linck so greiff auff des swertes ploß stoß In vntter augenn |

[08r.4] Daz sybentzechend figur Jagst du lingk so vall auf Swertes Kloss · stoss vndter augenn |

18 Jagstu linck fall aüfs schwertz knopf stos vndter augen |

[166r.3] Jagsts du lingk so vall auf schwerts kloß stos unnther augen |

[18r.4] Jagstu linckh so fall auf schwerts Clos, stoß vnder augen, | ||||||

The 18th Figure: Charge to the right side with its skill. |

[23r.6] Jag czu seiner rechte~ hant mit Irenn chunstenn |

[08r.5] Die achttzechendt figur Jage Zu der rechtten hanndt mitt Iren Kunsten |

17 Jag zw der rechtñ handt / mit irñ kunstñ |

[166r.4] Jag zu der rechtenn hannt mit yrenn kunnstn |

[18r.5] Jag zu der rechten hand mit jren kunsten | ||||||

The 19th Figure: Plant the point upon him to the face. |

[23r.4] Secz Im dein ort gege~ dem gesicht |

[08r.6] Die Nëwntzechent figur Setz an den ortt gegen dem gesichtte |

19 Setz an den ortt gegen dem gesicht |

[166r.5] Setz ann denn ort gegenn dem gesichterr |

[18r.6] Secz an den ort gegen dem gesicht, | ||||||

The 20th Figure: Shatter against all hits that ever happen. |

[23r.5] Schut gege~ allenn treffenn dye ÿmer werdenn |

[08r.7] Die tzwaintzigist figur Schutt gegen allen treffen · Diee ymmer werdenn |

20 Schutt gegen allen treffen die ym~er werdñ |

[166r.6] Schut gegenn allenn treffenn die ÿmer werdenn |

[18r.7] Schut gegen allen treffen die jmmer merkch | ||||||

The 21st Figure: The strong in the beginning position yourself therein correctly. |

[23r.10] dÿ strich zum anhebñ dar Inn schick dich recht |

[08r.8] Die ain vnd tzwayntzigist figur Die sterck in dem anheben · Dar Inn dich rechtt schicke |

21 Die stercke in dem an hebñ daryn dich recht schick / |

[166r.7] Die sterck in dem anheben darin dich rest schick |

[18r.8] Die sterch jm dem anheben dar jm du dich recht schickh | ||||||

The 22nd Figure: He who rushes the spear to the other is met beneath the eyes. |

[23r.11] das ist nwe der sper lauff der de~ andñ begege~t vnt° augñ |

[08r.9] Die tzwo vnd tzwaintzigst figur Das ist nun der sper lawff · der dem andern begegendt vndter augen |

22 Das ist nun der sper lauff der dem anderñ begegnet vndter augen / |

[166r.8] Das is nunn der sperr lauff der dem anndern begegnet unther augenn |

[18r.9] Das ist nun der sper lauf der dem andern begegnet vnder augen, | ||||||

The 23rd Figure: The Unnamed Grip takes the weapon or fells him. |

[23r.8] dye vngnnten griff wer nym oder fell In |

[08r.10] Die drey vnd tzwaintzigist figur Der vngenant griff · wer nymbtt oder velt In |

23 Der vngenant griff weer ny~t oder felt in |

[166r.9] Der ungenant griff wer nÿmbt oderr velt in |

[18r.10] Der vngenant griff wer nymbt oder felt jn, | ||||||

The 24th Figure: If an opponent charges you to both sides, turn around left and thus he rightly comes. |

[23r.9] ob mã dich jagt võ peyde~ seÿte~ ker linck vmb so er rech ku~pt |

[08r.11] Die vier vnd tzwaintzigist figur ob man dich Jagt zu bayden seytten kere vmb lingk so er rechtte kumbt |

24 Ob man dich jagt von paidñ seÿttñ ker vmb linck so er recht kumbt |

[166r.10] Ob mann dich iagt zu peidenn seitenn kere umb linck so er recht kumbt |

[18r.11] Ob man dich jagt von baiden seiten, ker umb linkh so er recht kunst | ||||||

The 25th Figure: Be mindful to take and hold the messer. |

[23r.12] Der meßer neme~ vnd behaltñ gedenck |

[08r.12] Die funff vnd tzwaintzigist figur Der Mezzer nemenn · vnd behalden gedenck |

[75r] 25 Der messer nemen vnd behalden gedenck |

[166r.11] Der messer nemenn unnd behaltenn gedenck |

[18r.12] Der messer nemmen vnd behalten gedenckh, | ||||||

The 26th Figure: Grasp over an opponent who falls upon you or ride against him. |

[23r.13] vber greiff wer dich an velt thue In wider treyben |

[08r.13] Die sechßvndtzwaintzigist figur vbergreif wer dich anvelet · oder thue Im wider Reyttens |

26 Vber greÿff wer dich an felt oder thue im wider reÿttens / |

[166r.12] Ubergreiff werr dich ann vellet oder thue im widerreittenns |

[18r.13] Vbergriff wer dich anfellt, oder thue jm vnderreittens | ||||||

If you want to grasp, you should not fail to ride beside him. Execute the Sun Pointer to the left sleeve if you want to bend. Who attacks you with that, grasp over against him and he will be shamed. Press the arm to the head. This grip often robs the saddle. |

[08r.14] Wild du anfazzen neben reittens nit solt du lasen daz sunnen tzaigen lingk ermel treib wildu naygen Wer dir daz rembt vbergreifft den der wierd beschämbt druck arm zu haubt der griff offt sattel berawbett |

[18r.14] Wilt du anfassen, neben raiten nicht soltu lassen, das zum len &c Werr dir das remt &c druck arm zu haubt, der grif oft selten beraubt. |

Nuremberg Version (1400s) |

Gotha Version (1448) |

Rome Version (1452) |

Vienna Ⅰ Version (1480s) |

Salzburg Version (1491) |

Krakow Version (1535-40) |

Vienna Ⅱ Version (1512) |

Augsburg Ⅱ Version (1553) |

Rostock Version (1570-71) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This is Master Johannes Liechtenauer’s Fighting on Horseback | [53r.1] Hie hebt sich nu an das fechten zu Rosse in harnüsche / mit sper vnd swerte etc~ JVng / Ritter lere · |

[21Av] Alhye hebt sich an dy chunst deß langñ swerts deß Roß vechtenn |

[06r] Das Ist Maister Johansen liechtenäwer ross vechten |

[105r] Maister hannsen liechtenauers ross fechtenn |

[17r] Das ist das Ross fechten das junger Ritter leern |

||||||||||||||||||

|

[53r.2] ~:DEyn sper berichte · |

Dein sper bericht |

[06v] Dein sper bericht |

[105v] dein Sper bericht |

[163r] Dein sper bericht, |

Dein sper berichte, |

|||||||||||||||||

[53v] ¶ Vör allen sachen · |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[55r.1] Ab sichs vorwandelt · |

ab sich verwandelt |

Ob es es sich vor wandelt |

ob sich verwandelt |

ob es sich vorwandelt, |

[17v] Ob sich verwanndlt, |

|||||||||||||||||

|

[55r.2] Zwene striche lere · |

Der Schaff griff weret |

Der schaff grif weret |

der schafgriff weret |

der schaffgriff weret, |

Der schaffgriff wöhret, |

|||||||||||||||||

|

[55r.7] Wen du erst windest · |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

[57v] DEr schofgrif weret · |

ab du wilt reytñ |

Ab du wilt reiten |

ob dw wild rewten |

[164r] dich an felt |

ob du wilt Reitten, |

|||||||||||||||||

|

[58r] Ab du wilt reiten · |

iagt man rechtens= |

[07r] faste |

Jagt man rechtens |

ab

du wilt reitn |

Jait man rechtens, |

|||||||||||||||||

|

[58v] Iagt man rechtens · |

dÿ |

Jagt man rechtens |

die messer nemen |

iagt man rechtens, |

Die messer nehmen, |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Dy messer nemen · |

[22r] messer neme~ |

Dÿe messer nemen |

wildw an wassenn |

Die

messer nemen, |

||||||||||||||||||

|

[59r] UIltu[240] an fassen · |

wiltu a |

wiltu anfassen |

wild dw dich aber massen |

wiltu ann fassen |

[18r] Wilt du ane fassen, |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Wilt aber dy masen · |

wiltu aber dich maßenn |

wiltu aber dich massen |

Das seind maister hansen liechtenauers fechtenn im harnasch zum champf

wer absinnet |

wiltu aber

dich massen |

Wiltdu aber die maassen, |

Nuremberg Version (1400s) |

Gotha Version (1448) |

Rome Version (1452) |

Vienna Ⅰ Version (1480s) |

Salzburg Version (1491) |

Krakow Version (1535-40) |

Vienna Ⅱ Version (1512) |

Augsburg Ⅱ Version (1553) |

Rostock Version (1570-71) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Here begins the Art with the Short Sword in Dueling, of Master Johannes Liechtenauer, God have mercy on him,

|

[60r] WEr abesynnet · |

[48v] Kampffechten hebt sich Hye an

Wer absynnet |

[08v] Hye hebt sich an Maister Johansen Liechtenawers kunst Dem got genädig sey mit dem kurtzen swert zu kampff

Wer absynt |

[105v] Das seind die Ringen zu dem champf [O]b dw wild ringenn |

[199r] Hie hebt sich an der Text unnd die Auslegung des Kampffechtn Text Wer absinet |

[18v] Fechten Im Harnasch zu fussen

Wer aber synnet |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

This is the wrestling in dueling

|

[61v] Das ist nü von Ringen / etc~ ~ AB du wilt ringen · |

ab du wilt ringñ |

Das sind dye ringen zu champff Ob dw wild ringen |

[105v] ob es sich ver ruckt |

[129r] Die zÿttel weist ringen züm kanff zu fuß Ob du wilt ringen |

Das sein die Ringenn zu Kampf. Ob du willt ringen, |

[100v] Ein anders Ob du wilt ringen |

Von Ringen, Ob du wilt ringen, |

[74v] Ob du wilt ringenn, | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

[59v] Ab sich vorrukt ·das swert keyn sper wirt gezukt / Der strich io war nym · sprink vach ringens yle zu ym / link lang von hant slach · sprink weislich vnd den vach / Ab her wil zücken · von scheiden vach vnd drük in / das her dy blöße mit swertes orte vordröße / leder vnde hantschuch · vnder dy awgen dy bloße recht zuch / Vorboten ringen · weislichen zu lere brengen / Zu fleißen vinde ·dy dy starken do mete vinde / In aller lere · den ort kegen der bloßen kere / |

ab sich verruckt |

Ob es sich vor ruckt |

verpotne ringen |

Ab es sich ver rucket |

ob

es sich verruckht, |

[100v] Ob es sich verruckest |

Ob sich verruckht |

Ob es sich verrucket, | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

[60v] WO man von scheiden · |

vechtñ ringen |

Verpotne ringen |

wo man von schaiden |

Wie man von scheydenn |

Verpotne ringen, |

verborgen ringen / |

verboden ringen, |

verporgenn Ringen, |

For further information, including transcription and translation notes, see the discussion page.

Additional translation notes: In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts ©2010 Freelance Academy Press, Inc.

Additional Resources

The following is a list of publications containing scans, transcriptions, and translations relevant to this article, as well as published peer-reviewed research.

- Alte Armature und Ringkunst: The Royal Danish Library Ms. Thott 290 2º (2020). Trans. by Rebecca L. R. Garber. Ed. by Michael Chidester; Dieter Bachmann. Somerville: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-04-5.

- Kunst und Zettel im Messer: Bavarian State Library Cgm 582 (2021). Ed. by Michael Chidester. Somerville: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-16-8.

- The Fencing Art (2022). Trans. by Mike Smallridge. Ed. by Stephen Cheney. Self-published. ISBN 978-0-47-366116-8.

- Acutt, Jay (2019). Swords, Science, and Society: German Martial Arts in the Middle Ages. Glasgow: Fallen Rook Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9934216-9-3.

- Ain ringeck, Sigmund (2003). Sigmund Ringeck's Knightly Art of the Longsword. Trans. by David Lindholm. Boulder: Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1-58160-410-8.

- Ain ringeck, Sigmund (2006). Sigmund Ringeck's Knightly Arts of Combat. Trans. by David Lindholm. Boulder: Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1-58160-499-3.

- Alderson, Keith (2010). "On the Art of Reading: An Introduction to Using the Medieval German 'Fightbooks'." In the Service of Mars: Proceedings from the Western Martial Arts Workshop, 1999-2009: 251-286. Wheaton: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-9825911-5-4.

- Alderson, Keith (2014). "Arts and Crafts of War: die Kunst des Schwerts in its Manuscript Context." Can These Bones Come to Life? Insights from Reconstruction, Reenactment, and Re-creation 1: 24-29. Wheaton: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-1-937439-13-2.

- Bauer, Matthias Johannes (2014). "Ein Zedel Fechter ich mich ruem/Im Schwert un Messer ungestuem. Fechtmeister als protagonisten und als (fach)literarisches Motiv in den deutschsprachigen Fechtlehren des ittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit." Das Mittelalter 19(2): 302-325. Ed. by Christian Jaser; Uwe Israel. doi:10.1515/mial-2014-0018.

- Bauer, Matthias Johannes (2014). "Fechten lehren 'mitt verborgen vnd verdeckten worten'. Fachsprache, Dialekt, Verballhornung und Geheimsprache in frühneuhochdeutschen Zweikampftraktaten." Das Schwert – Symbol und Waffe: 163-172. Ed. by Lisa Deutscher; Mirjam Kaiser; Sixt Wetzler. Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidorf GmbH. ISBN 978-3-89646-795-9.

- Bauer, Matthias Johannes (2016). 'Der Alten Fechter gründtliche Kunst' – Das Frankfurter oder Egenolffsche Fechtbuch. Untersuchung und Edition. München: Herbert Utz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8316-4559-6.

- Bergner, Ute; Johannes Gießauf (2006). Würgegriff und Mordschlag. Die Fecht- und Ringlehre des Hans Czynner (1538). Graz: Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt. ISBN 978-3-201-01855-5.

- Burkart, Eric (2016). "The Autograph of an Erudite Martial Artist: A Close Reading of Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Hs. 3227a." Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe: 451-480. Ed. by Daniel Jaquet; Karin Verelst; Timothy Dawson. Leiden and Boston: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004324725_017. ISBN 978-90-04-31241-8.

- Burkart, Eric (2020). "Informationsverarbeitung durch autographe Notizen: Die ältesten Aufzeichnungen zur Kampfkunst des Johannes Liechtenauer als Spuren einer Aneignung praktischen Wissens." Mittelalter. Interdisziplinäre Forschung und Rezeptionsgeschichte S2: 117-158. doi:10.26012/mittelalter-25866.

- Cheney, Stephen (2020). Ringeck • Danzig • Lew Longsword. Self-published. ISBN 979-8649845441.

- Chidester, Michael (2021). The Long Sword Gloss of GNM Manuscript 3227a. Somerville: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-13-7.

- Chidester, Michael; Dierk Hagedorn (2021). 'The Foundation and Core of All the Arts of Fighting': The Long Sword Gloss of GNM Manuscript 3227a. Somerville: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-05-2.

- Chidester, Michael; Dierk Hagedorn (2024). Pieces of Ringeck: The Definitive Edition of the Gloss of Sigmund Ainring. Medford: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-41-0.

- Fabian, Martin (2024). Fechtbuch Fabian. Self-published. ISBN 978-80-570-6163-2.

- Finley, Jessica (2021). "'What's in a Name?' A Comparative Analysis of the Nomenclature of Johannes Lecküchner and Johannes Liechtenauer." Kunst und Zettel im Messer: Bavarian State Library Cgm 582: 157-174. Ed. by Michael Chidester. Somerville: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-16-8.

- Finley, Jessica; Christian Henry Tobler (2022). "Warp and Weft: The Bauman Fight Book's Place in the Tapestry of German Fechtkunst." Bauman's Fight Book: Augsburg University Library Ⅰ.6.4º 2: 85-102. Ed. by Michael Chidester. Medford: HEMA Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-953683-27-4.

- Gaite, Pierre (2018). "Exercises in Arms: the Physical and Mental Combat Training of Men-at-Arms in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries." Journal of Medieval Military History XVI. Ed. by Kelly DeVries; John France; Clifford J. Rogers. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781783273102.

- Hagedorn, Dierk (2008). Transkription und Übersetzung der Handschrift 44 A 8. Herne: VS-Books. ISBN 978-3-932077-34-0.

- Hagedorn, Dierk (2016). "German Fechtbücher from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance." Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe: 247-279. Ed. by Daniel Jaquet; Karin Verelst; Timothy Dawson. Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-31241-8.

- Hagedorn, Dierk (2017). Jude Lew: Das Fechtbuch. Herne: VS-Books. ISBN 978-3-932077-46-3.

- Hagedorn, Dierk (2021). Albrecht Dürer. Das Fechtbuch. Herne: VS-Books. ISBN 9783932077500.

- Hagedorn, Dierk; Helen Hagedorn; Henri Hagedorn (2021). Renaissance Combat. Jörg Wilhalm's Fightbook, 1522-1523. Barnsley: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-78438-656-6.

- Hagedorn, Dierk; Christian Henry Tobler (2021). The Peter von Danzig Fight Book. Wheaton: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-1-937439-53-8.

- Hagedorn, Dierk; Daniel Jaquet (2022). Dürer's Fight Book: The Genius of the German Renaissance and his Combat Treatise. Barnsley: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-784438-703-7.

- Hagedorn, Dierk (2023). Das Ortenburger Fechtbuch. Herne: VS-Books. ISBN 978-3-932077-53-1.

- Hergsell, Gustav; Hans Talhoffer (1889). Talhoffers Fechtbuch (Gothaer Codex) aus dem Jahre 1443. Prague: J.G. Calve.

- Hergsell, Gustav; Hans Talhoffer (1893, 1901). Livre d'escrime de Talhoffer (codex Gotha) de l'an 1443. Prague: Chez L'Auteur.

- Hils, Hans-Peter (1985). Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes. Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang. ISBN 978-38-204812-9-7.

- Hull, Jeffrey; Grzegorz Żabiński; Monika Maziarz (2007). Knightly Dueling: The Fighting Arts of German Chivalry. Boulder: Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1-581606744.

- Kellett, Rachel E. (2015). "'...Vnnd schuß im vnder dem schwert den ort lang ein zu der brust': The Placement and Consequences of Sword-blows in Sigmund Ringeck's Fifteenth-Century Fencing Manual." Wounds and wound repair in Medieval culture: 128-150. Ed. by Larissa Tracy; Kelly DeVries. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004306455_007.

- Lecküchner, Johannes (2015). The Art of Swordsmanship by Hans Lecküchner. Trans. by Jeffrey L. Forgeng. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 9781783270286.

- Medel, Hans (2025). Hans Medel’s Fencing. Trans. by Martin Fabian. Self-published. ISBN 978-80-570-6960-7.

- Muhlberger, Steven (2005). Deeds of Arms. Highland Village: Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-44-7.

- Muhlberger, Steven; Will McLean (2019). Murder, Rape, and Treason: Judicial Combats in the Late Middle Ages. Wheaton: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-1-937439-41-5.

- Muhlberger, Steven (2020). Formal Combats in the Fourteenth Century. Witan Publishing. ISBN 979-8-662749-75-7.

- Müller, Jan-Dirk (1992). "Bild – Verse – Prosakommentar am Beispiel von Fechtbüchern. Probleme der Verschriftlichung einer schriftlosen Praxis." Pragmatische Schriftlichkeit im Mittelalter. Erscheinungsformen und Entwicklungsstufen: 251-282. Ed. by Hagen Keller; Klaus Grubmüller; Nikolaus Staubach. München: Fink.

- R., Harry (2019). Peter von Danzig. Self-published. ISBN 978-0-36-870245-7.

- Tobler, Christian Henry (2001). Secrets of German Medieval Swordsmanship. Union City: Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-07-2.

- Tobler, Christian Henry (2006). In Service of the Duke: The 15th Century Fighting Treatise of Paulus Kal. Highland Village: Chivalry Bookshelf. ISBN 978-1-891448-25-6.

- Tobler, Christian Henry (2010). In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts. Wheaton: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-9825911-1-6.

- Tobler, Christian Henry (2011). Captain of the Guild: Master Peter Falkner's Art of Knightly Defense. Wheaton: Freelance Academy Press. ISBN 978-1-937439-09-5.

- Verelst, Karin (2016). "Finding a Way through the Labyrinth: Some Methodological Remarks on Critically Editing the Fight Book Corpus." Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe: 117-188. Ed. by Daniel Jaquet; Karin Verelst; Timothy Dawson. Leiden and Boston: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004324725_008. ISBN 978-90-04-31241-8.

- Vodička, Ondřej (2019). "Origin of the oldest German Fencing Manual Compilation (GNM Hs. 3227a)." Waffen- und Kostümkunde 61(1): 87-108.

- Wallhausen, James (2010). Knightly Martial Arts: An Introduction to Medieval Combat Systems. Self-published. ISBN 978-1-4457-3736-2.

- Welle, Rainer (2017). "Ein unvollendetes Meisterwerk der Fecht- und Ringkampfliteratur des 16. Jahrhunderts sucht seinen Autor: der Landshuter Holzschneider und Maler Georg Lemberger als Fecht- und Ringbuchillustrator?." Codices manuscripti & impressi S12. Purkersdorf: Verlag Brüder Hollinek. ISBN 0379-3621.

- Welle, Rainer (2021). Albrecht Dürer und seine Kunst des Zweikampfes: auf den Spuren der Handschrift 26232 in der Albertina Wien. Kumberg: Sublilium Schaffer, Verlag für Geschichte, Kunst & Buchkultur. ISBN 9783950500806.

- Wierschin, Martin (1965). Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des Fechtens. München: C. H. Beck.

- Żabiński, Grzegorz (2008). "Unarmored Longsword Combat by Master Liechtenauer via Priest Döbringer." Masters of Medieval and Renaissance Martial Arts: 59-116. Ed. by John Clements. Boulder: Paladin Press. ISBN 978-1-58160-668-3.

- Żabiński, Grzegorz (2010). The Longsword Teachings of Master Liechtenauer. The Early Sixteenth Century Swordsmanship Comments in the 'Goliath' Manuscript. Poland: Adam Marshall. ISBN 978-83-7611-662-4.

References

- ↑ When German writers were aware that a person was dead, they would add a formulaic blessing after their name (i.e., "God have mercy on him"); this manuscript doesn't, but 15th century manuscripts do.

- ↑ See folio 13v, trans. by Michael Chidester.

- ↑ Christian Henry Tobler. "Chicken and Eggs: Which Master Came First?" In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts. Wheaton, IL: Freelance Academy Press, 2010. p6

- ↑ There is one version of the Recital that predates Talhoffer's, recorded in MS G.B.f.18a (ca. 1418-28) and attributed to an H. Beringer; this also conforms to a 15th century timeline and suggests the possibility that Liechtenauer was himself an inheritor of the teachings contained in the Zettel rather than its original composer (presentations of the Recital that are entirely unattributed exist in other 15th and 16th century manuscripts). Alternatively, the Beringer verse, which includes only portions of the Recital on the Long Sword, may represent just one of the teachings that Liechtenauer received and compiled over the course of the journeys described in the Pol Hausbuch.

- ↑ The figures are often given as a preamble for the gloss of Lew, and a fragment of the short sword to the teachings of Martin Huntsfeld, but those instances will not be included below and instead treated as part of those treatises.

- ↑ Zettel is a tricky word to translate. The closest English cognate is “schedule” (both come from the Latin schedula), but only in the more obscure legal sense of a formal list, not the familiar sense of a timetable. It’s commonly used in modern German to denote a short list or a scrap of paper that could hold a list (like a receipt). I translate Zettel as “record” here (and capitalize and italicize it as the title of a written work), but other common translations include “epitome”, “notes”, and “recital”.

- ↑ More literally ‘dem Gott gnädig sei=may God grant him grace’. When German writers were aware that a person was dead, they would add this formulaic blessing after their name.

- ↑ The direct translation here would be “long sword”, but since it isn’t the sword that’s long and instead it’s holding the sword with both hands on the grip that ‘lengthens’ it, “extended sword” seems clearer. Compare “retracted sword” in the dueling lessons, which refers to placing the left hand on the blade. An alternative interpretation might be that the amount of blade extending in front of the hands is long in the langen Schwert grip and short in the kurtzen Schwert grip.

- ↑ The spelling ‘Schirmeister’ is ambiguous. A Schirmmeister is a fencing teacher, using the late medieval term for fencing (schirmen rather than fechten). A Schirrmeister is an aristocrat’s stablemaster, or a logistics officer in a military setting in charge of animals and anything pulled by animals (wagons, cannon, etc.). ‘Schirmeister’ could be a spelling of either one; Hans Medel reads it as the former. The Leichmeistere ridiculed by the author of ms. 3227a in their introduction, often translated as “dance masters” or “play masters”, might be a shortening of this phrase (leichtfertigen schirmaister).

- ↑ There seem to be many levels of obscure and cryptic words in the Record. While the most obvious one is that the verses rarely give any clear, actionable instructions and instead merely describe ideas which the student can link to actions, the terms themselves seem to often be selected in order to be deceptive. Many terms used in the Record have multiple significant meanings which seem to be simultaneously operative (as described below). Hans Medel further teaches that the names of the five strikes are specifically intended as cryptic names to conceal basic strikes; he explains four of them: ‘Zornhaw=wrath cut’ is the cryptic name for the ‘Oberhaw=cut over/from above’; ‘Twerhaw=crosswise cut’ is the cryptic name for the ‘Mittelhaw=middle cut’; ‘Schilhaw=cockeyed cut’ is the cryptic name for the ‘Wechselhaw=change cut’; and ‘Schaitelhaw=part cut’ is the cryptic name for the ‘sturtzhaw=plunge cut’. While Hans Medel doesn’t give a common name to go with the cryptic name ‘Krummhaw=crooked cut’, Christian Trosclair has pointed out that the other four names are all included in Andre Lignitzer’s five strikes, and the remaining strike is the ‘Unterhaw=cut under/from below’. These five strikes also appear in the Salzburg witness to an Anonymous 15th Century Poem, while the København witness (probably prepared by Hans Talhoffer) replaces the lines referencing those ‘common strikes’ with different lines referencing Liechtenauer’s five hidden strikes. Christian Henry Tobler has identified some or all of these strikes in a number of non-Liechtenauer treatises, and speculates that they represent a widespread fencing teaching which was incorporated into Liechtenauer’s teachings.

- ↑ The individual section headings don’t seem to be part of Liechtenauer’s original Record—or at least, the scribes seem to have treated them as non-authoritative and freely expanded, contracted, modified, or omitted them entirely. They are only included here in abbreviated form and can be hidden along with the footnotes for easier reading.

- ↑ Jay Acutt has pointed out that the structure of the Record of the extended sword could be framed in terms of Classical rhetoric following Cicero and others, in which case this preface is the exordium, the introduction that appeals to the audience by declaring the speaker/writer’s ethos.

- ↑ Some version of this preface to the Record appears in most 15th cen. witnesses but is absent from most from the 16th; it’s generally included as part of the teaching on fencing with the extended sword, but the author of ms. 3227a and Antonius Rast include abbreviated versions of it at the beginning of the mounted dueling verses, and Pseudo-Peter von Danzig includes it in their gloss of the retracted sword. Given this, and the fact that its teachings reference weapons only covered in the dueling section, I consider it a general preface to both sections of the Record.

- ↑ Note that though the preface is quoted by the glossators, it’s rarely discussed by them (see the notes below for exceptions).

- ↑ The Lew gloss is unique in adding ‘Jungfrauen=maidens/virgins/unmarried women’ alongside ‘Frauen=women/married women’.

- ↑ “That I laud” is an addition to the text to serve the rhyme.

- ↑ Jens P. Kleinau has pointed out that in the first couplet, the second line is much longer than most in the Record, while in this second couplet, the version used by the Lew gloss only includes the first line and has lere instead of ere (as does the Dresden witness to Sigmund ain Ringeck’s gloss, though it retains ere) whereas the version appearing in H. Beringer and Hans Folz only includes the second line. This may be evidence of a ‘seam’ in the Record where two early proto-Records were merged together, each of which only mentioned loving god in the first couplet and had honoring women as the first line of the second couplet, which would look like this in rhyme:

- Young knight, learn what I teach to you:

Have love for God, and reverence true

For ladies and for maidens show.

- Increase your learning/honor well and know (Lew)

- Practice chivalry and know (Beringer)

- Young knight, learn what I teach to you:

- ↑ Whenever the Record mentions ‘Kunst=art, craft, skill’, a minority of witnesses instead have ‘ding=thing’. This word is obviously so broad as to be almost meaningless, but here it should probably be understood in the context of the Latin terms ‘ars=art’ vs ‘res=thing’ (as Jay Acutt points out). The res is the idea, concept, or subject matter, while the ars is the skill of putting the idea into practice.

- ↑ “In play” is an addition to the text to clarify that this line seems to refer to honors and glory won through demonstrations of individual prowess in deeds of arms, jousts, tournaments, etc.

- ↑ In the same blog post, Jens P. Kleinau points out that the mention of Ehre (rendered “fame” in this line to avoid repetition) may be a later addition to the text, since some witnesses have sehre instead of zu Ehre, which makes the phrase and meter smoother; additionally, the idea of warfare as an avenue of increasing one’s honor is mostly absent from contemporary literature. Hofieren is to serve, often in a feudal or courtly sense, so the alternate rhymed version would be “And serve you well in war some day”.

- ↑ Messer is a term that we often associate with the iconic machete-like German long knife taught by Johannes Lecküchner and others, but both historically and today it can refer to any kind of knife; mentions of it in the Record are usually interpreted as referring to daggers by the glossators.

- ↑ More literally “manly”, not “gallant”, but I’ve used ungendered language for the most part in this translation because I want readers to be able to more easily see themselves and their training partners in it regardless of their genders. Kendra Brown points out that there’s a possible intended parallel between this line and the line above about honoring women; they aren’t parallel constructions, but both seem to emphasize gender expectations.

- ↑ Bederben and verderben could be read as synonyms in Early New High German (ENHG), both meaning “to destroy”, but that doesn’t make sense in context so we tend to read bederben as the Middle High German (MHG) ‘biderben=to use or utilize’. H. Beringer uniquely has ‘bedurfen=need or make use of’, which reinforces this reading and could represent an earlier, less ambiguous phrasing.

- ↑ H. Beringer’s version of the preface ends here, as do those recorded in Paulus Kal’s manuscripts (the Vienna witness and the Bologna witness, though the latter adds an additional couplet at the end which is unique to it and Hans Talhoffer’s Gotha manuscript). Jens P. Kleinau sees a division here where the moralistic/inspirational address to the young knight ends and practical advice to a fencing student begins. I disagree, and think couplets 6–9 are still about mindset and morality in fighting.

- ↑ I will generally translate the verb hauwen as “to cut” since that’s the common parlance, but remember that there’s no connotation that the intent is to cleave anything or otherwise directly hit your opponent. The word is instead often used to describe a cutting motion that will set up further techniques (such as cutting in order to hit with a thrust).

- ↑ More literally “Charge in, let it hit or pass”.

- ↑ Couplet 6 isn’t directly glossed, but is invoked by the author of ms. 3227a in their gloss of the common lesson.

- ↑ The Lew gloss replaces couplet 7 with a completely different one:

- So that your art and skill surely

Will then be praised as masterly.

- So that your art and skill surely

- ↑ This word pair is translated in all kinds of ways, from the abstract/geometric (dimension and extension) to the colloquial (time and place, weighed and measured) to the fencing-specific (distance and reach). My translation goes with a more moralistic read: outlining two qualities the young knight needs to develop, both of which point to the cardinal virtue of temperance. This couplet isn’t directly glossed, but is invoked by the author of ms. 3227a in their gloss of the common lesson and their summary of the art; it’s also invoked and connected to teachings in sword section of the Augsburg Group manuscripts.

- ↑ The author of ms. 3227a includes 62 additional couplets in their presentation of the Record of fencing with the extended sword; some are repetitions of Liechtenauer’s couplets from other sections, some are remixes of multiple different couplets, and some seem to be entirely original compositions. These will not be included in this translation since there are so many of them, and they don’t occur in an unglossed statement of the Record, but they can be read in their article.

- ↑ This couplet might instead have been intended to be combined with the previous one as two very long lines of a single couplet: "ettlich biderman in anden hanten veder ben / kunt er chunst er mocht wol eren erwerb".

- ↑ Text adds an additional couplet: "kündt er kunst er möcht ere erwerben".

- ↑ First letter almost illegible.

- ↑ First letter illegible.

- ↑ Classical rhetoric would label this section the narratio, the statement of basic facts and the nature of the things being discussed. This would suggest that this section is describing the basic model of how a ‘fight’ works: one fencer attacks with a downward blow from the proper side using proper footwork and threatens their opponent with the point, provoking a parry (the author of ms. 3227a terms this a ‘Vorschlag=Leading Strike’); after this, the attacker progresses to the skirmish, attacking whatever target the parry has exposed (termed a ‘Nachschlag=Following Strike’).