|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Ott Jud

| Ott Jud | |

|---|---|

| Born | date of birth unknown |

| Died | 1448-52 (?) |

| Occupation | Wrestling master |

| Ethnicity | Jewish |

| Patron | princes of Austria |

| Movement | Fellowship of Liechtenauer |

| Genres | Wrestling manual |

| Language | Early New High German |

| Manuscript(s) |

Cod.I.6.4º.3 (1460s)

|

| First printed english edition |

Tobler, 2010 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

Ott Jud was a 15th century German wrestling master. His name signifies that he was a Jew, and several versions of his treatise (including the oldest one) state that he was baptized Christian.[1] In 1470, Paulus Kal described him as the wrestling master to the princes of Austria, and included him in the membership of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer.[2] While Ott's precise lifetime is uncertain, he may have still been alive when Hans Talhoffer included the Gotha version in his fencing manual in ca. 1448, but seems to have died some time before the creation of the Rome version in 1452.[3]

Ott's treatise on grappling is repeated throughout all of the early German treatise compilations and seems to have become the dominant work on the subject within the Liechtenauer tradition.

Contents

Textual History

Manuscripts

It is difficult to say when Ott's treatise was written, and the original is certainly lost at present. It is also unclear how much of the material in the existing versions should be attributed to him directly. Jessica Finley has pointed out that the first 31 plays form a coherent progression, whereas the subsequent 38 plays are disorganized. Furthermore, there are a number of copies that are limited to one half or the other, including Vienna and the prose Wassmannsdorff for the first part and Dresden and the poetic Wassmannsdorff for the second; these copies of only the second part make no mention of Ott in their introductions. It's possible that these two halves of the text had separate origins, with the first being written by Ott and the second mistakenly attributed to him early on, a mistake that persisted in the tradition ever after.

The oldest extant copy is the Gotha version, which was included in a manuscript in the 1440s alongside works by Johannes Hartlieb, Hans Talhoffer, and others. The Gotha version appears incomplete compared to other early renditions, which may suggest that Ott was not directly involved despite its proximity to his career. Gotha was copied into several further manuscripts along with the other contents of the manuscript, including the New York (16th century), the Göttingen (17th century), and the third Munich (ca. 1820) versions; since these are all direct copies, they offer little additional help in understanding Ott's work (apart from being evidence of its continued transmission).

Two copies of Ott's work date to the mid-15th century, the Rome (1452) and Augsburg (1460s) versions. These both contain plays not found in Gotha but also show differences from each other, indicating that the textual tradition had already diverged into two branches (though Augsburg is only a fragment of its branch). Of the later 15th century copies, Vienna Ⅰ (1480s) and Ortenburg (late 1400s) follow Rome, and Salzburg (1491) is a complete version of the text appearing in Augsburg—indeed, Rainer Welle describes Salzburg as the most detailed version of the treatise up to that time.[4] Likewise, in the 16th century, Dresden (1504-19), Glasgow (1508), and Kraków (1535-40) follow Rome, while Vienna Ⅱ (1512), Wassmannsdorff (1539), Munich Ⅱ (1556), and the works of Paulus Hector Mair follow Augsburg (Mayr's manuscripts and Munich Ⅱ even have the same gaps as the Augsburg fragment).

Establishing the relationships between these versions is very problematic. The pattern of which plays are present in each of the early versions and which plays are missing doesn't match the later versions in each branch—for example, Vienna Ⅰ has plays not present in Rome, Salzburg has far more than the fragmentary Augsburg, and there are a few plays present in both Vienna and Salzburg that are in neither one of those first versions. Either some later versions were created by combining multiple earlier ones, or there are many missing links in this chain. Furthermore, certain plays have descriptions that gain extra pieces of clarifying text as time passes, especially in the Rome branch.[5] This is especially apparent in Kraków, which has expanded versions of more than half of the plays (and was also intended to be augmented with illustrations for the first time). This expanding text might be evidence that the early copies are all incomplete fragments and the expanded versions are the correct ones, but it may equally suggest that Ott's treatise received additional input and clarifications from other knowledgeable wrestlers over the course of time.

Finally, there were two notable transformations of Ott's treatise in the 16th century. First, Wassmannsdorff's now-lost 1539 manuscript contains two versions of Ott: one a fragment of the first 24 plays, the other covering the final 20 plays (49-69) but also including plays 50-55 recomposed as poems. This rewriting of a core text is otherwise unprecedented in the Liechtenauer tradition, and the author appears to be anonymous. The second transformation of the text occurred in the 1540s, when Mayr had it translated into Latin.

Most texts in the Liechtenauer corpus seem to have ossified immediately and been preserved without any intentional changes after they were initially written. The expansions to Ott's core plays and the poetic rewrite of part of the text both buck this trend, and make his treatise a unique example of a living textual tradition that may mirror a living teaching tradition.

Modern HEMA

Several books related to Ott were published in the 19th century which would be influential once HEMA was established, including Wassmannsdorf's transcription of the Augsburg version (and his own manuscript) in 1870, published as Die Ringkunst des deutschen Mittelalters, and Hergsell's transcription and modernization of the Gotha version in 1889, titled Talhoffers Fechtbuch (Gothaer Codex) aus dem Jahre 1443 (which was then translated to French and published in 1893 and 1901 as Livre d'escrime de Talhoffer (codex Gotha) de l'an 1443.

Ott was likewise represented at the very beginning of HEMA in Martin Wierschin's 1965 opus Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des Fechtens, which included a transcription of the the Dresden manuscript (attributed entirely to Sigmund ain Ringeck, an error that would then persist in HEMA thought for half a century). Wierschin's catalog also includes more than half of the currently-known copies of Ott: Gotha, Rome, Augsburg, Vienna Ⅰ, Salzburg, Dresden, Dresden Ⅱ, Vienna Ⅲ, Munich Ⅱ, and Munich Ⅲ. Of those that were left out, Vienna Ⅱ, Kraków, Munich Ⅰ, and Göttingen were added by Hans-Peter Hils in his 1985 update Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen Schwertes.

Of the remaining three known copies, the Glasgow Fechtbuch was identified in Sydney Anglo's 2000 opus as merely "[R. L.] Scott's Liechtenauer MS",[6] but had been fully profiled by 2008 when Rainer Leng published his catalog. The New York version has mostly been left out of scholarly literature, though it was known by many HEMA researchers and was even the subject of an essay by Daniel Jaquet published by the Met in 2018.[7] Finally, the Ortenburg Fechtbuch was discovered by Hils in the 80s, only to be lost again ever after; microfilm scans that Hils bought at the time were finally the subject of an extensive book by Dierk Hagedorn published in 2023 as Das Ortenburger Fechtbuch, including the first transcription, modernization, and other analysis.

The earliest work on Ott is inseparable from work on Ringeck, because of the previously-mentioned attribution of the Dresden manuscript to Ringeck. Thus, the first transcription of any part of the text would be Wierschin's transcription of the Dresden version in 1965, the first German modernization was made by Christoph Kaindel in the 1990s, and the first English translation was authored in 1999 by Alex Kiermayer. Another English translation was produced by Christian Tobler and published in 2001 by Chivalry Bookshelf in Secrets of German Medieval Swordsmanship, and a third English translation was produced by David Lindholm and published in 2005 by Paladin Press as part of Sigmund Ringeck's Knightly Arts of Combat: Sword-and-Buckler Fighting, Wrestling, and Fighting in Armor.

Possibly the first dedicated work on Ott (under his own name) was done by Monika Maziarz, who transcribed the Rome, Augsburg, Salzburg, and Kraków versions between 2002 and 2004 and posted them on the ARMA-PL site.

The first English and Solvenian translations of a complete version of Ott (rather than the Dresden fragment) were created by Gregor Medvešek in 2010.

In 2015, Kendra Brown, Nicole Brynes, Michael Chidester, Rebecca Garber, Mark Millman, members of the Cambridge HEMA Society (CHEMAS), transcribed and translated the German and Latin versions of Ott in Paulus Hector Mair's Vienna Ⅲ. The transcriptions were donated to Wiktenauer but the translation was saved until it could be edited and refined.

In 2017, Laurent Ott completed a new transcription of the Rome version and a French translation, posting it on the Gagschola site.

However, most work on Ott has been done as part of larger projects processing an entire manuscript. In 2006, Carsten Lorbeer, Julia Lorbeer, Andreas Meier, Marita Wiedner, and Johann Heim, working as part of the Gesellschaft für pragmatische Schriftlichkeit, authored a complete transcription of the Vienna Ⅰ manuscript as part of their Paulus Kal project (which was eventually posted on that site). Also in 2006, Dierk Hagedorn authored a new transcription of the entire Rome manuscript as well as a German modernization, posting both on the Hammaborg site. These were subsequently published by VS-Books in Transkription und Übersetzung der Handschrift 44 A 8 in 2008. Over the subsequent decade, Dierk would go on to likewise transcribe the entirety of the manuscripts containing the Gotha, Augsburg, Vienna Ⅰ, Dresden Ⅰ, Glasgow Ⅰ, and Vienna Ⅱ, all of which were likewise released on Hammaborg. In 2012, Pierre-Henry Bas transcribed large sections of the Dresden version of Mair's work for his dissertation and released them on his blog REGHT, including Ott.

In 2010, Christian Henry Tobler's complete English translation of the Rome manuscript was published by Freelance Academy Press as In Saint George's Name: An Anthology of Medieval German Fighting Arts; this translation was also used by Jessica Finley in her 2014 book on Ott, also published by Freelance. In 2017, Rainer Welle published a complete transcription of the Kraków manuscript in Codices manuscripti & impressi (Supp. 12) as "Ein unvollendetes Meisterwerk der Fecht- und Ringkampfliteratur des 16. Jahrhunderts sucht seinen Autor: der Landshuter Holzschneider und Maler Georg Lemberger als Fecht- und Ringbuchillustrator?"

Several of Dierk Hagedorn's transcriptions also turned into books. His Augsburg transcription was published in 2017 by VS-Books in Jude Lew: Das Fechtbuch along with modernizations and English translations by various others; Ott's section was modernized and translated by Anneka Fleischhauer. He combined his Rome transcription with Tobler's English translation to create The Peter von Danzig Fight Book, published by Freelance Academy Press in 2021. His Vienna Ⅱ transcription and German modernization was published by VS-Books as Albrecht Dürer. Das Fechtbuch in 2021, and was published by Greenhill Books along with his English translation as Dürer's Fight Book: The Genius of the German Renaissance and his Combat Treatise in 2022.

Treatise

Teachings of Ott Jud

| Illustrations from the Kraków |

Draft Translation (from the Rome) by Gregor Medvešek |

Incomplete Translation (from the Dresden) by Alex and Almirena |

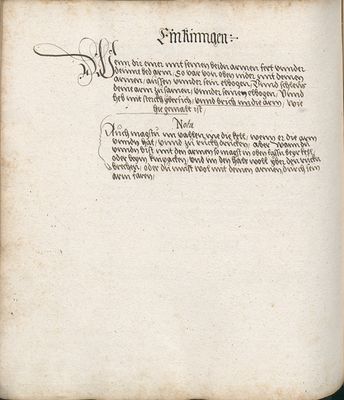

Gotha Version (1448) Transcribed by Dierk Hagedorn |

Rome Version (1452) Transcribed by Dierk Hagedorn |

Augsburg Version (1460s) Transcribed by Dierk Hagedorn |

Vienna Version Ⅰ (ca.1480) Transcribed by Dierk Hagedorn |

Ortenburg Fechtbuch (1400s) | Salzburg Version (1491) Transcribed by Dierk Hagedorn |

Dresden Version (1504-1519) Transcribed by Dierk Hagedorn |

Glasgow Version Ⅰ (1508) Transcribed by Dierk Hagedorn |

Vienna Version Ⅱ (1512) Transcribed by Dierk Hagedorn |

Kraków Version (1535-40) Transcribed by Monika Maziarz |

Wassmannsdorff Version (1539) Transcribed by Karl Wassmannsdorff and Michael Chidester |

Dresden (Mair) Version (1540s) Transcribed by Pierre-Henry Bas |

Vienna (Mair) German Version (1550s) Transcribed by Nicole Brynes, Rebecca Garber, Mark Millman |

Munich (Mair) Version (1540s) Transcription open for editing |

Vienna (Mair) Latin Version (1550s) Transcribed by Kendra Brown, Rebecca Garber |

Munich Version Ⅱ (1556) | New York Version (1500s) | Göttingen Version (1600s) | Munich Version Ⅲ (ca. 1820) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[1] |

[1] Here begins the wrestling as taught by master Ott, the wrestling master of the noble dukes of Austria, may God have mercy on his soul. |

[1] |

[1] |

[109v.1] Verzund hernach so hebt sich an dÿ maß czu allem Ringñ dye stuck dann gemacht hat Ott der ey~ tauffter Jud ist gewesñ |

[100v.1] Hÿe heben sich an die ringen die do gesatz hat maister Ott dem got genädig seÿ der hochgeborñ fürsten von Österreich ringer gewesen ist |

[85r.1] Hie heben sich an die Ringen die Maister Ott gedicht hat der ein getauffter Jud gewesen ist |

[122v.8] Die her nach geschribenn ringen hat gemacht ein tauffter Jud genant maister ott der herrnn vonn oster reich ringer |

[53r.2] |

[119r.1] Item Hie hebt sich an das Ringenn zu° fueß |

[67r.1] Das sind die Ringen die der Ott gemacht hat der ain tauffter Jüd gewessen ist / |

|||||||||||||

[2] What is necessary to know about Wrestling Note that in all wrestling there are three things one must pay great attention to: the first is the art itself, the second speed, and the third is how to use your strength at the right place and time. But by far speed is the best, since speed allows for no countermoves. Apart from that you must know that you can wrestle however you wish with those who are weak(er than you), and if you are weaker than your opponent, you must carefully watch after your opponent's weak spots. Furthermore, if you are weaker than your opponent you must also be fast, and take heed to (catch) his knees, and if you are equally matched you must use the scales. |

[2] [A good common teaching] Every wrestling must consist of three things. The first one is skill, the second one is speed, and the third one is the proper application of strength. Keep in mind that the best of them is speed as it prevents your opponent from countering you. It is also important to attack a weaker opponent first,[9] an equally strong opponent at the same time as he attacks you,[10] and a stronger opponent after his attack.[11] When you attack first use your speed, when you attack at the same time as the opponent use your balance and when you act after your opponent pay attention to his knee-bendings. |

[2] |

[2] |

[109v.2] merck ein ler In allenn ringñ sullenn sein drew ding das erst ist kunst das ander Ist snellikayt das dritt ist rechtew abgevng der sterck dar vmb so sol man merckñ das das pest ist snellikayt dy lat nicht czu pruchen komenn Darnach soltu merckenn das mã den kranckenn sol vor ringñ vnd allenn gleichñ sol mã mit ringenn vnd allenn \starcken/ sol man nach ringenn vnd In allñ gleichñ vor ringñ so wart der snellikayt In allem mit ringñ so wart der wag Vnd czu allem nach ringñ so wart der knyepug |

[100v.2] In allen ringen süllen sein drew dingk Das erst ist kunst das ander ist schnelligchait Das dritt ist rechte anlegung der sterck dar vmb soltu mercken das das pest ist Schnellichait die lest nicht zu° prüche kumen Darnach soltu mercken das man allen chrancken sol vor ringen vnd allen geleichen sol man mit ringen vnd allen starcken sol man nach ringen vnd In allen vor ringen wart der schnellichait In allen mit ringen wart der wag vnd in allen nach ringen wart der knÿepüg ~ |

[85r.2] ITem In allen Ringen süllen sein drej dingk. Das erst kunst. Das ander schelligkeit.[!] Daz dritt ist recht anlegung der sterck Darümb soltu mercken das pest ist schnelligkeit die nit lest zuprüchen kommen Darnach soltu mercken das man allen krancken sol vor Ringen vnd allen starcken nachringen Vnd In allem vorringen wardt der schnelligkeitt In allen mitringen wart der wog Vnd In allen nachringen wartt der kniepüg. |

[122v.9] In allenn ringenn sullenn sein drew ding das erst ist chunnst das ander schnel lichait das tritt ist rechte anlegung der sterck vnd wis das dy snellichait das pest ist die lät nichtz zw prechenn chumenn auch sol man allenn chranckenn vor ringen allenn geleichenn sol man mit ringen allenn starcken sol man nach ringenn vnd in allenn vor ringen wartt der snellichait vnd in allem mit ringen wart [!] vnd in allem nach ringen wart der chnyepug |

[53r.2] |

[119r.2] Item In allen Ringenn sollen syn drÿ ding Das erst künst das ander schnellikeytt das tritt ist recht an legu°ng der sterck darümb soltu mercken / das best ist schnellikeÿtt die nit zu bruchen lest kumen Dar noch soltu merckenn daß man allen krancken sol vorr ringenn vnd allen starcken noch ringenn vnd in allem vor ringen wart der schnellikeytt In allen mit ringenn wart der wag vnd In allem vnd ringnn wart der knye bueg |

[67r.2] Ain gemaine guette Ler Item allen ringen sullen sein dreu ding / das erst ist kunst das ander ist schnellikait / das dritt ist rechte anlegung der sterck / daru~b soltü mercken / das das pest ist schneligkait die last nit zu pruchen kumen / darnach soltu mercken / das man allen krancken sol vor ringen / Vnd allen gleichñ sol man mit ringen / Vnd allen starcken sol man nach ringen / vnd in allen vor ringen wart der schnelikait / In allen mit ringen wart der wag / vnd in allen nach ringen wart der knye pueg |

[100v.8] Ringung Item In allem ringen Sollen sein drÿg ding das erst kunst das ander schnelleklichen das dritt ist rech an legung der stercke dar vmb soltu mercken das erst ist schnellickeyt die do mit lust [!] zu brechen kummen darnoch soltu mercken das man allen krancken sol vor ringen vnd allenn starcken nach ringen vnd in allem vor ringen wart der schnellickeyt In allenn mit ringen der wage vnd in allem nach ringen der knübuge wartt |

[131r.2] ~ Die ersten ~ In allen rinngen sollen sein, dreu ding, daß erst ist kunst, Daß ander ist schneligkeit, Daß drit ist rechter anlegunng, der sterckh Darumb merckh, das besst ist schneligkeit, die lest nit zu bruch kummen, Darnach soltu mercken, das man allen kranncken soll vor rinngen, Unnd allen gleichen soll man mit rinngenn, Unnd allen starcken soll mann nachrinngen, ~: Unnd in allen vor rinngen wart der schnelligkeit: · In allenn mitrinngen wart der wag: ~ Unnd in allen nachrinngen wart der kniebug. |

[1] Item[12] In allen Ringen füllen drei ding sein Das erst kunst Das ander Schnelligkeit. Daz dritt ist recht anlegung dr schritt[!] Darümb soltu mercken das pest ist schnelligkeit die laß nit zu brauchen komen Darnach soltu mercken das man allen krancken sol vor Ringen vnd allen starcken nachringen vnd In allem vorringen wardt der schnelligkeitt In allē mit ringen wart der wag vnd In allē nachringen wart der kniepüg. |

[114r.2] Die Rinngen Item Inn allen Rinngen sollen sein drey dinng. das erst kunnst. das annder schnelligkait. das drit ist recht. anlegunng der sterckh. Darumb soltu mercken das pöst ist schnelligkait. die nit last zu pruchen kommen. Darnach soltu mercken. das man allen kranncken. soll vor rinngen. vnd allen starcken. nachrinngen. vnnd Inn allen vorrinngen. wart der schnelligkait. Inn allem mitrinngen wart der wag. vnnd Inn allem nachrinngen. wart der kniepug. |

[87r.1] Erinnerunng dess Rinngens. Inn Allen Rinngen sollen drei dinng sein: das erst ist Kunnst, Das annder Schnelligkeit, Unnd das drit Rechte anlegunng der Sterckh, Darumb soltu mercken, das pesst ist Schnelligkeit, die nit lesst zu brüchen kommen, darnach solltu mercken, das man allen kranncken solle vorrinngen unnd aller starcken nachrinngen, unnd inn allen vorrinng warrt der Schnelligkeit, In allem mitrinngenn warrt der Wag, unnd in allem Nachrinngen warrt der Kniebüg. |

[292r.1] Exhortatio qua quoquisque athleta modo in luctis uti debeat docetur Tria in omnie luctae genere maxime observentur: primum est ars ipsa. secundum celeritas in agendo, tertium ut viribus tuis suo loco et tempore rite utaris. Quorum longe optimum est celeritas quae minime admittit, ut habitus tui in luctando in nihilum redigantur. Post observandum est, ut infirmos facile quibusvis habitibus vincas utendo. Infirmi vero magnopere curent ut prospiciant diligenter ubi hostis sit vincendus. Infirmi item celeriter agant, et poplitem hostis observent, colluctationi libra opus erit. |

[104r.1] Exhortatio qua quo quisque athleta modo in luctis uti debeat docetur. Tria in omnj luctae genere maxime observentur, primum est ars ipsa: secundum, celeritas in agendo, tercium, ut viribus tuis suo loco et tempore rite utaris, Quorum longè optimum est celeritas, quae minime admittit, ut habitus tuj in luctando in nihilum redigantur, Pòst observandum est, ut infirmos facile quibusvis habitibus vincas utendo, Infirmi vero magnopere curent, ut prospiciant diligenter, ubi hostis sit vincendus, Infirmi item celeriter agant, et poplitem hostis observent, colluctationj libra opus erit. |

||||||

[3] Wrestling while holding at each others' arms When you wish to wrestle your opponent by holding his arms, always remember to hold him at the muscle(probably the biceps) of his right arm with your left hand, and with your right hand on the outside of his left, and the left hand that holds his muscle, push him backwards forcefully, and with your right hand grab hold in front of his left hand pull it towards you, and when you have someone in this grip, then use the wrestling techniques written hereafter. |

[3] This is a teaching When you want to wrestle with someone, make sure you always grab him with your left hand by the muscle of his right arm and with your right hand by the outer side of his left arm. Quickly push back his right arm, which you have grabbed by the muscle, grab lower on his left arm with your right hand and pull it forcefully towards yourself. When you have grabbed someone in this manner continue with whichever wrestling technique of here described you see fit. |

[3] |

[3] |

[100v.3] Das ist ein lere Wenn dw mit einem ringen wild aus den armen So gedenck albeg das du in fast mit deiner lincken hant in der maus seins rechten arm~s vnd mit der rechten hant in faß aus wendig seins lincken arm~s vnd mit der lincken hant die du in der maus hast druck frisch zw° ruck vnd mit der rechten hant begreif ÿm sein k lincke hant foren vnd zeuch fast zw° dir vnd wenn du einen also gefast hast so treib die ringen die hernach geschriben sten welches dich am pesten dunckt ~ |

[85r.3] Item wenn du mit einem Ringen wilt auß den armen So gedenck albeg das du In fassest mit deiner lincken hant In der mauß seines rechten armes vnd mit deiner [85v.1] rechten hant In fassest außwendig seins lincken armes vnd mit der lincken hant die du In der mauß hast truck frisch zu rucke vnd mit deiner rechten hant begreif Im sein lincke hant vorn vnd zuck vast zu dir Vnd wann du einen also geuast hast So treib die ringen die hiernach geschrieben sten welches dich am pesten duncket |

[122v.10] wann dw mit einem ringenn wild [123r.1] Aus dem arm so gedennck albeg das dw in vast mit der tenckenn hannd in der maus seins rechtenn arm vnnd mit der rechtenn hand in vast auswendig seins tenncken arms vnd mit der tenncken hand die do In in twiest hast druckt vast zu ruck vnd mit der rechtenn hannd begreyf sein tencke hand vorn vnd zeuch die vast zw dir vnd wenn dw ainen also geuast hast so treyb die her nach geschribenn ringenn |

[53r.4] |

[119r.3] Itm~ wan du mit eynem Ringenn willt vß den armenn So gedenck allwegenn daß du In vassest mit der lincken hantt In der mauß synes rechtenn arms vnd mit diner rechte~ hantt vßwendig sines lincken arm vnd mit der linckenn hantt die du in der mauß hast druck Frisch zu° rueck vnd mit diner rechte~ hantt begriff im sin lincke hantt vorn vnd zuck vast zu dir vnd wan du eynenn also gefast hast So tribe die ringenn die hernoch geschribenn sten welche dir gefallenn ~~ |

[67r.3] Merck die fassen in den armen / Wen du mit ainem ringen wild auß den armen / so gede~ck albeg das du in vast mit deiner lingken handt / in der maus seins rechten arms / vnd mit der rechte~ hand in vast auß wendig seins lincken arms / vnd mit der lincken die du in der mauß hast / druck frisch zu ruck / vnd mit der rechten handt begreiff im sein lincke handt forn vnd zeuch vast zu dir / vnd wen du ain also gefast hast / so treib die ringen die hernach geschriben stend / welchs dich am pestñ dünckt / |

[100v.9] Item Wan du mit einem ringen willt auß dem arm So gedenck alwegen das du Im fassest mit der lincken hand Inder mauß außwendig seynes lincken arms vnd mit der lincken hand die du in der maüß hast durch frisch zu ruck vnd mit deiner rechten hand begriff In sein lincke hand forn vnd zuck fast zu dir vnd wann du einen also gefasset hast So reybe die ringüng die her nach geschriben sten |

[131r.3] .·Ein ler. Wenn du mit einnem rinngen willt, aus den armen, so gedennckh albeg das du in fasst, mit deinner linncken hant in der mauß, seinns rechten arms, ~ Unnd mit der rechten hannt faß in auswenndig seins linncken arms, unnd mit der linncken hannt (die du in der maus hast, [131v.1] druck frisch zu ruckh, unnd mit der rechten hannt begreif im sein linncken hannt vornnen, unnd zeuch vast zu dir, unnd wenn du ainen also gefasst hast, so treib die ringen die hernach geschriben steen welchs dich am besten dunckht. |

Item wenn du mit einem Ringen wilt auß den armen So gedenck albeg das du In fassest mit deiner lincken haut du mans seines rechten armes vnd mit deiner rechten hant In außwendig fasset seinen lincken armes vnd mit dr linckē haut, die du dan der mauß hast, truck frisch zu rucke vnd mit deinr rechten hant begreif Im sein lincke hant vorn vnd zuck vast zu dir vnd wann du in einen also gevast hast, So treib die ringen die hienach geschrieben sein welches dich am pesten dunket. |

[114v.1] Ausz den Armen zu Rinngen. Item wann du Mit ainnem Rinngen wilt. ausz den Armen so gedennckh alweg das du In fassest mit deinner linncken hannd Inn der Maus seinnes Rechten Arms vnnd mit deinner rechten hannd In fassest auszwenndig seinns Linncken Arms. vnnd mit der Linncken hannd. die du Inn der Mausz fassest. truckh frisch zu rucken vnnd mit deinner rechten hannd begreiff Im seinn linncken hannd. fornen vnnd zuckh fast zu dir. vnnd wann du ain also gefassest. so treib die Rinngen die hernach geschriben stehen. welches dich am Posten dunncket. |

[87r.2] Auß den Armen Rinngen. Item. Wann mit ainem Rinngen willt auß den Armen, so gedennck allweg, das du im fassest mit deiner linnggen hannd, im der mauß seines rechten arms, unnd mit deiner rechten hannd im fassest auswenndig seines linnggen arms, unnd mit der linnggen hannd, die du in der mauß fassest druck frisch zu rugg, Vnnd mit deiner rechten hand [87v.1] begreif imm sein linngge hannd vornen vnnd zucke fasst zu dir vnnd wann du ainnen allso gefasst hast so treib die Rinnggen die hernach geschriben steen wölches dich am pessten dunnckht. |

[292r.2] Ratio luctandi ex brachiis ut infra declarabitur Quum voles adversarium lucta adgredi ex brachiorum correptione, tum memineris semper ut musculum dextri brachii hostis manu tua sinistra adprehendas, dextra autem brachium ipsius sinistrum externe, atque sinistra qua musculum ipsius contines, retrorsum reprimas pro viribus, dextra vero manum adversarii anterius adprehendas, nec non adtrahas. Si igitur quempiam praescripta ratione corripueris, iis luctarum habitibus qui subsequenter iam describuntur utitor |

[104r.2] Ratio luctandi ex brachijs ut infra declarabitur. Quum voles adversarium lucta adgredi ex brachiorum correptione, tum memineriius semper, ut musculum dextri brachij hostis, manu tua sinistra adpraehendas, dextra autem brachium ipsius sinistrum externè: atque sinistra, qua musculum ipsius contines, retrorsum reprimas pro viribus, dextra vero, manum adversarij anterius adprehendas, nec non adtrahas, Si igitur quempiam praescripta ratione corripueris, ijs luctarum habitibus, qui subsequenter iam describúntur, utitor. |

|||||||

[4] The first grip When you have him in this grip thus, then put your left hand on his right arm grab hold of him underneath his right hand, where you hold his left hand. Push his arm away from you, and it will be dislocated. |

[4] [The first wrestling] When you have grabbed him in this manner—with the left hand by the muscle of his right arm and with the right hand low on his left arm—slide your left hand around his right arm, grab his right elbow from below and pull it towards yourself. Use your right arm—with which you have grabbed his left arm—to push away. This is how you twist his arm. |

[4] |

[4] |

[109v.2] Wann du In also geuast hast so var mit deiner tenckñ hãt auß seine~ rechtñ arm vnd begreiff Im vndenn seine~ rechten elbogenn vnd zeug den czu dir vnd mit sem rechtñ do du dein dencke hant In hast stoß Im den arm võ dir so ver ruckest du Im den arm |

[101r.1] Das erst wenn du In also gefast hast mit der lincken hant in der maus seins rechten arm~s vnd mit der rechten hant vorñ peÿ seiner lincken So var mit deiner lincken hant aus seine~ rechten arm~ vñ begreif ÿm vnden seinen rechten elpogen vnd zeuch den zu° dir vnd mit der rechten do du sein lincke hant Inn hast stos Im den arm~ von dir so verenckstu Im den arm~ ~ |

[123r.2] wenn dw in geuast hast mit der tennckenn hand in der maus seins rechtenn arms vnd mit der rechtenn vorn bey seiner tenckenn so far mit deiner rechtenn hannd auf seinen rechtenn arm vnd begreyff inn vnd seinen rechtenn elpogenn vnd zeuch denn domit zue dir vnd mit der rechten da dw Im sein /+tenncke/ hannd in hast stoß im denn arm //// von dir// |

[53r.5] [53v.1] |

[119v.1] Das erst Ringenn Itm~ wan du yn also gefast hast So far mit diner linckenn hantt vff sinem rechte~ arm vnd begriff im vnder sinem rechte~ elnbogenn vnd zuck den zu dir vnd mit der rechte~ hantt so du sin lincke hantt ynn hast Stoß den arm von dir so ver°uckstu ÿm den arm |

[67r.4] Das Erst stuckt Wen du in also gefasst hast mit der lincken hant in der maus seins rechten arms vnd mit der rechten handt vorñ [67v.1] vorñ[!] pey seinem lincken / so var mit deiner[14] lincken handt auß seinem rechten arm~ / vnd bereiff im vndten sein rechtñ arm~ olpogñ vnd zeuch in zu dir / vnd mit der rechten handt da du sein[15] lincke handt in hast stos im den arm~ von dir / so verrenckst du im denn arm~ |

[100v.10] Die erst Wann du Im also gefasset hast So far mit deiner lincke hand auff sein rechten arm vnd begriff In vnden sein rechten elenwogen vnd zucken den zu dir vnd mit der rechten hand do du sein lincke hand Ime hast stost den arm von dir So verruckestu Im den arm |

Item Das erst stuck wann du In also geuasset hast So far mit deiner lincken hant auß seinem rechten arm vnd begreiff (In vnnter seiner rechten hand vnd zeug dan czu dir vnd mit der rechten hant) die du sein lincke hant Innen hast Stos Im den arm von dir So verruckstu Im den arm. |

[114v.2] Das erst fassen Item das Erst stuckh. wann du In also gefasset hast. so far mit deinner Linncken hannd. auf sein rechten arm. vnnd begreiff Inn vnnder seinner Rechten hannd. da du sein linncken hand Innen hast. stosz Im den Arm. von dir. so verrenckest du Im den Arm. |

[87v.2] Das erst fassen. Item Das erst struck wann du ine allso gefasst hast, so far mit deiner linnggen hannd, auf seinen rechten arm, vnnd begreif ime vnndter seiner rechten hannd, da du sein linngge hannd innenn hast, stoss ime den Arm von dir, so verrennckstu ime den Arm. |

[292r.3] Ratio adprehendendi hostem prima Si corripueris adversarium iniecta brachio hostili dextro manu [292v.1] tua sinistra atque sub manu eius dextra complectitor ubi ipsius sinistram contines. Inde, si brachium propuleris brachium adversarii infirmabis. |

[204r.3] Ratio adprehendendi hostem prima. Si corripueris adversarium, iniecta brachio hostili dextro, manu tua sinistra, atque sub manu eius dextra complectitor ubi ipsius sinistram contines, inde si brachium propuleris, brachium adversarij infirmabis. |

||||||||

[5] The second Push up your opponent's left arm with your right hand, and go through with your head underneath it. Then quickly put it over the back of your neck and with your right hand grab hold of the back of his knee, and throw him behind your back. |

[5] Another When you have grabbed him as described before use your right hand to lift his left arm up, duck with your head under his left arm and pull it onto your neck. With your left hand, grab his left leg by the bending of the knee and throw him over your back. |

[5] |

[5] |

[109v.4] Ain Ander stuck Heb Im auff dem tenckenn arm mit deiner rechtñ hant vnd var Im mit dem hewpt vnder den arm vnd zeuch In den vber deine~ hals vnd mit der tenckenn hant begreiff Im sein tenckeß pain in der knyepug vnd wurff ir In alßo vber deine~ ruck |

[101r.2] Ein anders Item wenn du In gefast hast als vor so heb ÿm auf den lincken arm~ mit deiner rechten hant vnd var Im mit dem haubt durch den arm~ vnd zeuch den vber deinen hals vnd mit der lincken begreif ÿm sein lincks pain in der knÿepüg vnd wurf In also vber deinen ruck ~ |

[85v.3] Item ein anders auß den vassen. Heb Im auf den lincken arm mit deiner rechten hant Vnd far Im mit dem haubt durch den arm [86r.1] vnd zuck Im den über deinen hals vnd mit der lincken hant begreiff Im sein linckes pein In der kniepiegung vnd würff In also über den rucke. |

[123r.3] wenn dw in geuast hast mit deiner tenncken handt in der maus seins rechten arms vnd mit der rechtenn vor bey seiner tennckenn so heb im auf denn techkenn[16] arm vnd dem vber seinen hals vnd mit der tencken hand begreyff sein techtz[17] pain in der chnye pug vnnd würff in also vber dich Ober |

[53v.2] |

[119v.2] Ein anders Itm~ vß dem vassenn heb ym vff den linckenn arm mit diner rechte~ hantt vnd ge im mitt dem haupt durch denn arm vnd zück In dan vber dins hals vnd mit der lincke~ hantt begriff Im sein linckes pein in der kneulbbueg vnd wurff in also vber denn Rurck ~ |

[67v.2] Ains anders Item / Wen du in gefast hast als vor heb in auff den lincken arm~ mit deiner rechtñ handt / vnd far im mit dem haubt durch den arm~ / vnd zeuch in dan vber dein hals / vnd mit der lincken handt pegreiff im sein lincks pain in der knyepueg / vnd wurff in also vber den rück |

[100v.11] Das ander Auß dem fassen Hab Im auf den lincken arm mit deiner rechten hand Im mit dem haupt durch den vnd zuck In dan über den halß vnd mit der lincken hand begriff sein linckes beyn Inder knüpuge vnd wirff im alß über dein ruck |

[132v.1] |

Item ein anders auß den vassen. Heb Im auf den lincken arm mit deiner rechten hant vnd schleuss mit dem haubt durch den arm vnd zuck Im den über den hals vnd mit der lincken hant begreiff Im sein linckes pein In der kniepiegūg vnd würff In also über den rucke. |

[115r.1] Ainn annders Fassen Item ain annders Ausz den fassen. heb. Im auf den Linncken Arm mit deinner Rechten hannd vnnd far Im mit dem haupt. durch den arm. vnnd zuckh Im den vber deinnen hals. vnnd mit der linncken hannd begreiff Im seinn Linnckes pain Inn der kniepuge. vnnd wirff In allso vber den rucken. |

[87v.3] Ein anders fassen. Item hebe ime auf, den linnggen arm mit deiner rechten hannd, und fare ime mit dem haubt durch den arm, unnd zuck ime den über deinen halß unnd mit der linnggen hannd begreif ime sein lingger bain inn der kniebüge, unnd wirf ime allso über den rucken. |

[292v.2] Secunda ratio Manu dextra brachium hostis sinistrum sublevato, atque caput sub brachio eodem transmittas. Inde brachium celeriter collo tuo circuminiicias, sinistra vero manu sinistrum itidem hostis pedem adprehendas in ipso poplite, atque ea ratione usus per dorsum hostem praecipites. |

[104r.4] Secunda ratio Manu dextra brachium hostis sinistrum sublevato, atque caput sub brachio eodem transmittas, inde brachium celeriter collo tuo circumijcias, sinistra vero manu, sinistrum itidem hostis pedem adprehendas in ipso poplite, atque ea ratione usus, per dorsum hostem praecipites. |

[38r.4] Page:Cgm 3712 038r.jpg [38v.1] Page:Cgm 3712 038v.jpg | |||||

[6] Another Another technique from the arm hold. Raise your opponent's left arm with your right hand, with your left hand grab hold under his (right?) elbow, and pull him towards you, and with the right hand above push away from you, and step behind his right foot with your left and throw him over your left leg. |

[6] Another wrestling from the first hold Use your right hand to lift his left arm. Grab his elbow from below with your left hand and pull it towards yourself. Use your right hand to push his arm up and away from yourself. Spring with your left leg behind his right leg and throw him over your left thigh. |

[6] |

[6] |

[109v.5] Aber ein ander Stuck Heb Im auff /sey~\ tenckenn arm mit deiner tenckñ hant vndenn [110r.1] an deine~ elpogñ vnd zeuch da mit czu dir vnd mit der rechtñ stoß obenn võ dir vnd spring mit dem tenckñ fuß vnd wurff in ausß dem fueß vber dein tenckes pain |

[101r.3] Aber ein ringen aus dem erstñ fassen Item heb ÿm auf den lincken arm~ mit der rechten hant vnd greif Im mit der lincken vnden an seinen elpogen vnd zeuch do mit zu° dir vnd mit dem rechten stos Im den arm~ oben von dir vnd spring mit deine~ lincken fuess hinder seinen rechten vnd würf In aus dem fuess vber dein lincks pain ~ |

[86r.2] Item ein anders auß dem fassen Heb Im auf den lincken arm mit deiner rechten hant vnd greiff Im mit deiner lincken hant vnden In sein elenpogen vnd zuck damit zu dir vnd mit der rechten stos oben von dir vnd spring mit deinem lincken fuß hintter seinen rechten fuß vnd würff In auß dem fuß über dein linckes pein etc. |

[123r.4] heb im auf denn tenncken arm mit deiner rechten hannd vnd greyff im mit deiner tenckenn vnden an seinen elpogenn vnd zeuch do mit zw dir vnd mit der rechten stos obenn von dir vnd spring mit dencken fues fur sein rechtenn vnd würff in aus dem fueß vber sein denncks pain |

[53v.3] |

[119v.3] Itm~ vß dem vassenn heb in vff den linckenn arm mit diner rechte~ hantt vmb griff ym mit der lincke~ vnder In sein elboge~ vnd zu°ck do mit zu dir vnd mit der rechtenn stos obenn von dir vnd spring mit dinem linckenn fuß hinter sinen rechtenn fuß vnd wurff in vß dem fvß vber dein linckes peÿnn ~ |

[100v.12] Ein anderß auf den fassen Heb Im auf den lincken arm mit deiner r. handt vmb griff Im mit der lincken hand vnd in sein elenbogen vnd zuck do mit zu dir vnd spring mit deinem l. hinder sein r fuß vnd wirf In auff dein fuß über dein linckes bein |

[135r.1] |

Item ein anders auß dem fassen. Heb Im auf den lincken arm mit deiner rechten hant vnd greiff Im mit deiner lincken hant vnden an sein elenpogen vnd zuck damit zu dir vnd mit der rechten stos oben von dir vnd spring mit deinem lincken fuß hintter seinen rechten fuß vn̄ würff In über dein linckes pein &c. |

[115r.2] Ainn annders fassen. Item ain annders Ausz dem fassen. heb Im auf den Linncken Arm mit deinner rechten hannd. greiff Im mit deinner linncke hand vnnde Inn sein Elennpogen. vnnd zuckh damit zu dir. vnnd mit der Rechten stosz oben vonn dir. vnnd spring mit deinnem Linncken fuosz hinder seinnen rechten fuosz vnnd wirff. In ausz dem fuosz vber dein Linnckes pain |

[87v.4] Ein anders fassen. Item heb ime auf den linnggen arm mit deiner rechten hannd, unnd greif ime mit deiner linngg [88r.1] hannd unnden in seinen Elenbogen, unnd zucke damit zu dir, unnd mit der rechten stosse oben von dir unnd sprinng mit deinem linnggen fuß hinndter seinen rechten fuß unnd wirf ime auß dem fuß über dein linngges bain. |

[292v.3] Alia species Rursus manu dextra brachium hostis sinistrum sustollas verum sinistram manum inferne cubito eius iniicias, atque eo modo versum te attrahas, dextra autem superne propellito, inde si sinistrum pedem prosiliendo hostis dextro postposueris, per eundem eum prosternas. |

[104r.5] Alia Speties Rursus manum dextra brachium hostis sinistrum sustollas, Verum sinistram manum infernè cubito eius inijcias, atque eo modo versum* te adtrahas, dextra autem supernè propellito, inde si sinistrum pedem prosiliendo, hostis dextro postposueris, per eundem eum prosternas. |

|||||||

[7] Another grip Another technique out of the first hold: hold firmly with your right hand on your opponent's left, and put your left hand on your right for support and hold steady with both hands. Then, if you turn around to your right under his arm, you have him captured. |

[7] Another wrestling from the first hold Firmly hold his right arm with your left hand and reach with your left hand to help your right.[19] Hold his arm firmly with both of your hands and turn through[20] alongside his arm to his right side. This is how you defeat him from the back. Alternatively, you can turn through to your left side. |

[7] |

[7] |

[110r.2] Halt Im vest mit der rechtñ hant vnd greyff Im da mit sey~ tencke hant d vnd greiff mit der tenckñ hant dein° rechtenn czu hilff vnd halt vest mit peydñ hentñ vnd wendt dich durch seine~ arm auff dein rechtew seyten so gewinst du Im den ruck an |

[101r.4] Aber ein ringen aus dem ersten vassen [101v.1] Item halt in fest mit der lincken hant sein rechte vnd greif mit der lincken hant dein° rechten zu° hilf vnd halt sein arm~ fest mit paiden henden vnd wendt dich durch sein arm~ auf sein rechte seitten so gewingstu Im den ruck an oder wendt dich durch auf dein lincke seitten ~ |

[86r.3] Item aber eins ausß dem erstenn fassen Halt In vest mit deiner rechten hant sein lincke vnd greif mit deiner lincken hant deiner rechten zuhilff vnd halt vest mit [86v.1] beden henden Vnd wende dich durch seinen arm auf dein rechte seitten So gewÿnnestu Im den ruck an. |

[123r.5] mer ein ringenn aus dem erstenn vassenn halt in vast mit der rechtenn hand sein dencke vnd greyff mit der tencken der rechtn zw hilf vnd halt vest mit paidn henndenn vnd went dich durch sein arm auf sein rechte seyten so prichst dw Im arm vnd gewinngst im denn ruck ann |

[53v.4] [54r.1] |

[119v.4] Itm~ vß dem vassenn halt yn vest mit diner rechtenn hantt sine lincke vnd griff mitt diner lincke hant diner rechtenn zu hilff vnd [120r.1] halt vest mit beÿdenn hendenn vnd wende dich durch seynn arm vß diner rechte~ sittenn So gewinstu ym den m ruckenn an ~ |

[67v.4] Aber aus dem ersten fassen ains Item Halt im vest mit der lincken handt sein rechte handt vnd greiff mit der lincken handt deiner rechtñ handt zu hilff vnd halt vest mit paiden henden / vnd wend dich dürch sein arm~ auff dein rechte seyttñ / so gewnistu im den rück an / |

[100v.13] Aber einß auß dem fassen Halt Im ffest mit deiner r. hand sein lincke hand vnd mit deiner lincke hand deyner rechten zu hilff vnd halt vest mit beyden handen vnd wende dich durch sein arm auß deiner rechten seyten So gewinestu In dem rucken ann |

[133r.1] |

Item aber eins ausß dem erstenn fassen Halt In vest mit deiner rechten hant sein lincke vnd greif mit deiner lincken hant deiner rechten zu hilff und halt In [!] vest mit beden henden vnd wende dich durch feinen arm auf dein rechte seitte So gewynnestu Im den ruck an. |

[115v.1] Ainn annders fassen Item aber ains ausz dem Ersten. fassen halt Inn feest mit deinner Rechten hannd. sein linncke vnnd greiff mit deinner linncken hannd deinner rechten zu hilff. vnnd hallt feest mit baiden hennden vnnd wennd dich durch seinn Arm auf dein rechte seitten. so gewinnstu Im den ruckh ab. |

[88r.2] Ein annders fassen. Item hallt ime fesst mit deiner rechten hannd sein linngge, unnd greif mit deiner linnggen hannd deiner rechten zuhilf, unnd hallt fesst mit beden henden unnd wende dich durch seinen arm, auf dein rechte seitten, so genemmstu ime den ruggen ab. |

[293r.1] Alia Effigies Alius ex prima correptione habitus: dextra manu ipsius adversarii sinistram fortiter teneas, tum vero sinsitram dextrae opem laturus adiungas, itaque firmissime manu utraque teneas. Inde, si sub brachio ipsius te in latus dextrum tuum converteris, partes potiores obtinebis. |

[104r.6] Alia effigies. Alius ex prima correptione habitus: dextra manu ipsius adversarij sinistram fortiter tenas, tum vero sinistram, dextrae opere laturus adiungas, itaque firmissime, manu utraque tenas, inde si sub brachio ipsius te in latus dextrum tuum converteris, partes potiores obtinebis. |

||||||

[8] Counter If someone goes through you, then go through with him, and use whatever wrestling device you wish. |

[8] This is how you counter the turning through When he turns through at your side, turn through yourself and use whichever wrestling you see fit. |

[8] |

[8] |

[110r.3] Also prich das vor geschribenn Stuck Wer dir durch get gee mit durch vnd val In ain ringenn In welcheß du wilt |

[101v.3] Also prich das durch wenden Item wer dir durch geht do ge mit durch vnd fall in ein ringen In welches du wild ~ |

[86v.2] Bruch Item wer dir durch gee dem gee mit durch vnd vall In ein ringen In welches du wilt. |

[123r.6] Also prich das wer dir durch get da ge mit durch vnd fall in welches ringenn dw wild |

[54r.2] |

[120r.2] Ein bruch Itm~ Wer dir durch geth / dem ge mit durch vnd val in ein ringen In welches du willtt |

[67v.5] Also prich das Wer dir durch geet da gee mit durch / vnd fall in ain ringñ in welchs du wilst |

[100v.14] Ein bruch dor(?) wider Item wer dir durch gett dem gee mit durch vnd in ein ringen vnd wechsel es welches du wilt |

[134r.1] Also prich das durchwenten [W]er dir durch get da gee mit durch unnd fal in ein ringenn weliches du wilt |

Bruch. wer dir durch gee dem gee mit durch vnd vall In ein ringe In welches du wilt. |

[115v.2] Bruch Item wer dir durchgeet. dem gee mit Durch vnnd fall Inn ain rinngen Inn welches du wilt. |

[88r.3] Bruch. Item Wer dir durch geet, dem gee mit durch unnd fall in ein rinngen in wölches du willt. |

[293r.2] Destructio Si quis habitu superiori contra te utatur, tu eodem vicissim utitor et post speciem luctandi eligas, quaecunque placuerit. |

|||||||

[9] Another counter technique Hold his left hand as hard as you can with both your hands, and turn around to your left in under his arm. That way you will put a stop to his device, and you may also throw him and as well as dislocate his arm. |

[9] |

[9] |

[9] |

[110r.4] Halt Im vast mit paydñ hentñ sein tencke hant vnd went dich durch sein arm auff dein tencke seytñ |

[86v.3] Item halt In vest mit beden henden sein lincke vnd wend dich durch sein arm auf dein lincke seitten. |

[120r.3] Itm~ Halt in vest mit bedenn hendenn sin lincke hãtt vnd wend dich durch sin arm uff din lincke site~ |

[67v.6] Aber ain stuck [68r.1] Item halt Im vest mit paidñ hendtñ sein lincke handt vnd wend dich durch sein arm~ auff dein lincke seyttñ |

[100v.15] Ein anderß Item halt Im vest mit beyden henden sein lincke hand vnd wende dich durch sein arm auf dein lincken seytten vnd wirff Im |

Item halt In vast mit beden henden sein lincke vnd wend dich durch sein arm auf dein lincke seitten. |

[115v.3] Ainn andrer pruch Item halt In feest mit baiden hennden. sein lincke vnd wennd dich durch seinn Arm auf dein linncken seiten. so prichstu Im seinn furnemen. Magst Im auch Im werffen sein arm prechen. |

[88r.4] Ein annderer Bruch. Item hallt ime fesst mit beden hennden, sein linngge unnd wennde dich durch seinen arm auf dein lingge seitten, So brichstu ime sein fürnarmmen, magst ime auch innm werffen, seinen arm brechen. |

[293r.3] Alius destructionis habitus Manu tua utraque firmissime, quantum poteris, ipsius adversarii sinistram contineas, atque te sub brachio sinistrorsum convertas, et ea ratione propositum eius conturbatis, insuper etiam brachium ipsius in praecipitatione poteris disrumpere. |

[104r.8] Alius destructionis habitus. Manu tua utraque firmissimè quantum poteris, ipsius adversarij sinistram contineas, atque te sub brachio sinistrorsum convertas, et ea ratione propositum eius conturbabis, in super etiam brachium ipsius in praecipitatione poteris disrumpere. |

||||||||||

[10] Another counter technique Hold the left hand of your opponent firmly with both hands and turn to your left in under his arm. Then, put his left arm over your right shoulder and pull down. |

[10] |

[10] |

[110r.5] Halt Im sein tencke hant vest mit den paydenn henttñ vñ went dich durch sey~ tenckñ arm auff dein tencke seÿtem [!] vnd zeuch Im den arm vber dey~ rechtew achsell vnd ruck vntter sich |

[101v.2] Ein anders Item hald im sein lincke hant fest mit paiden henden vnd wendt dich durch sein arm~ auf sein lincke seitten vnd zeuch Im den lincken arm~ vber dein rechte achsel vnd prich vndersich ~ |

[86v.4] Also brich das. Item halt Im sein lincke hant vest mit deinen baiden henden vnd wend dich durch sein arm auf dein lincke seitten vnd zuck Im den lincken arm über dein rechte achselnn vnd ruck vnttersich. |

[123r.7] Ein arm pruch Halt dein swert [!] in deiner tenncken hand vest mit paiden hennden vnd went Im sein arm auf sein tencke seytenn vnd zeuch Im den tenckenn arm vber sein rechte achsel vnd ruck vndersich |

[54r.3] |

[120r.4] Also prich daß Itm~ halt im sin lincke hantt vest mit beden hende~ vnd wendt dich durch sin arm vff din lincke site~ vnd zuck Im den lincken arm vber din rechte achsell vnd ruck vndersich ~ |

[68r.2] Also prich das Item halt Im sein lincke fest mit deine~ paidñ hendñ vnd wendt dich durch sein arm~ auff sein lincke seyttñ / vnd zeuch Im den lincken arm~ vber dein rechte achsel vnd ruck vnder sich / |

[100v.16] Also brich das Item halt Im sein lincke hand fest mit deynen beyden henden vnd wend dich durch sein arm vnd zuck Im den lincken arm vber dein recht achsel |

[133v.1] |

Also brich das. halt Im sein lincke hant vest mit deinen baidē henden vnd wend dich durch sein arm auf dein lincke seitten vnd zuck Im den lincken arm über dein rechte achseln vnd ruck übersich. |

[116r.1] Also prich das Item halt Im seinn Linncken hannd Veest mit deinnen baiden hennden. vnnd wennd dich durch sein arm auf dein linncken seiten vnnd zuckh Im den linncken arm yber dein Rechten Ahslen. vnnd ruckh vnndersich. |

[293v.1] Antecedentem item habitum hac ratione destruas Sinistram adversarii manum utrisque tuis manibus firmiter teneas, atque inde sub brachio eius sinistrorsum te convertas. Post si brachium postis sinistrum per humerum dextrum pertraxeris supprimas et potiores partes obtinebis. |

[104r.9] Antecedentem item habitum hac ratione destruas. Sinistram adversarij manum utrisque tuis manibus firmiter teneas, atque inde sub brachio eius sinistrorsum te convertas, pòst si brachium hostis sinistrum per humerum dextrum pertraxeris, supprimas, et potiores partes obtinebis. |

||||||||

[11] Another wrestling device If someone holds you by the arms, and you hold him likewise, and he then has a loose grip, then strike loose his left hand loose with your right hand from above, and then grab outside of his left arm(?) in the back of his knee and with your left hand push him in the left side of his chest, then he will fall. |

[11] Another wrestling If someone grabs you by the arms and you do the same but he holds you loosely, thrust his left arm downwards with your right arm, grab his left leg by the bending of the knee and pull it towards yourself. With your left arm strike to the left side of his chest, so that he must fall. |

[11] |

[11] |

[111r.4] Wann dich einer geuast hat pey den arme~ vnd thu In wider vnd helt er dich// laß// so slag Im seine~ tenckenn arm auß mit dein° rechtñ hant vnd obenn nyder vnd pegreiff Im da mit sey~ tencks pain in der knÿepug vnd zeuch czu dir vnd mit d° tencke hant stoß In vorn an dye prust an sein° tencken seÿ seytenn so mueß er vallñ |

[103r.3] Aber ein ringen Item wenn dich ein° gefast hat peÿ den armen vnd du In wider Helt er dich denn loß So slach ÿm sein lincken arm~ aus mit deiner rechtñ hant von oben nÿder vnd begreif im do mit sein lincks pain in der knÿepüg vnd zeuch zu° dir vnd mit der lincken hant stos In vorñ an die prüst an seiner lincken seitten so mües er vallen ~ |

[89r.2] Aber ein Ringen Item wann dich einer gefast hat pej den armen vnd du In wider Helt er dich dann lose, so slag Im sein lincken arm auß mit deiner rechten hant von oben nider vnd begreif Im damit sein linckes pein In der kniepiegung vnd zuck zu dir Vnd mit der lincken hant stos In vorn an die prust an seiner lincken seitten So muß er vallen |

[123v.3] wenn dich ainer geuast hat bey dem arm vnd dw in wider vnd helt er dich lose so slach im den tenckenn arm aus mit deiner rechtenn hanndt von obenn nyder vnd begreyff im do mit sein tenncks pain In der chnyepug vnd zeuch zw dir vnd mit der tenncken stos in vorn an die prust an seiner tencken seytenn so mues er vallenn |

[55r.3] |

[120r.5] Itm~ wen dich einer gefassett hat by dem arm vnd du in wider / helt er dan dich loß so schlag im sin lincken arm vß mit diner rechte~ hantt von oben nider vnd begriff ym do mitt sin lincks peÿn in der kneübüg vnd zuck zu° dir vnd mit der linckenn hantt stos in vorn an dÿ bruest an sinenn linckenn so müß er vallenn ~ |

[69r.3] Aber ain ringen Item Wen dich ainer gefast hat peÿ den arm~ / vnd du in wider / vnd halt er dich loß / so schlag im sein lincken auß mit deiner rechtñ handt von oben nÿder vnd begreiff im damit seins lincks pain in der knÿe pueg vnd zeuch zu dir / vnd mit der lincken handt stos in vorñ an die prust an seiner linckñ seyttñ so muß er fallñ / |

[100v.17] Ein anders Item wann dich einer gefasset hatt bey deym arm vnd an In wider hellt er dich dan also so schlach Im den lincken arm auß mit deyner rechten hand von oben nider vnd begriff im do mit sein linckes bein in der knübug vnd zuck zů dir vnd mit l. hand stoß Im vorn an sein brust an sein lincken muß er fallen |

[137v.1] |

Aber ein Ringen. Item wann dich einer gefast hat mit payden armen vnd du In widr Helt er dich laß, so slag Im sein lincken arm auß mit deiner rechten hant von oben nider vnd begreif Im damit sein linckes pein In der kniepiegung vnd zuck zu dir vnd mit der lincken hant stos In vorn an die prust an seiner lincken seitten So muß er vallen. |

[118r.2] Aber ainn Rinngen Item wann dich ainner Gefasst hat bey den armen. vnnd du Inn wider. heelt er dich dann lose. so schlag Im seinn Linncken Arm ausz mit deinner Rechten hand von oben nider. vnnd begreiff Im damit seinn linnken Arm. ausz mit deinner rechten hannd. von oben nider. vnnd begreiff Im damit sein linnckes pain Inn der kniepuge vnnd zuckh zu dir. vnd mit der linncken hannd stosz In vornen ann die prust an seiner linncken seitten. so muosz Er fallen. |

[90r.2] Aber ain Rinngen. Item wann dich ainer gefasset hab, bej den Armen, vnnd du ime wider, hellt er dich dann loß, so schlage ime seinen linnggen arm auß mit deiner rechten hannd, von oben nider, vnnd begreif ime damit seinen linngen arm auß, mit deiner rechten hannd, von oben nider, vnnd begreif ime damit[24] sein linngges Bain, in der kniebüge, vnnd zucke zu dir, vnnd mit der linnggen hannd stosse ime vornen an die brust, an seiner linnggen seitten, so muß er fallen. |

[295r.2] Aliud luctae genus Quum quispiam brachia tua corripuerit atque tu ipsius vicissim et si is leviter te contineat, tum brachium ipsius sinistrum manu tua dextra super excutito deorsum demittendo, atque inde manu dextra poplitem medis sinistri hostilis corripito externe atque attrahas, sinistra deinde manu si pectus de latere sinistro concusseris, hostis concidere cogetur. |

[104v.3] Aliud Luctae genus. Quum quispiam brachia tua corripuerit, atque tu ipsius vicissim, et si is leviter te contineat, tum brachium ipsius sinistrum manu tua dextra supernè excutito, deorsum demittendo, atque inde manu dextra poplitem pedis sinistri hostilis corripito externè, atque adtrahas, sinistra deinde manu si pectus de latere sinistro concusseris, hostis concidere cogetur. |

||||||

[12] Counter to the above If someone grabs you up front in the chest with his left hand, then grab his left hand with your left hand and turn around, and with your right hand lock his left elbow. |

[12] This is how you counter it When someone grabs you with his left hand by your chest from the front, grab his left arm with your left hand, and break his balance with your right hand by grabbing his elbow. |

[12] |

[12] |

[111r.5] Also prich das Wann dir einer var greifft an dy prust mit seiner tenckñ [111v.1] hant So begreiff Im sein tencke hant mit deiner tencken vnd reyt Im vmb vnd mit deiner rechtñ hant ny~ Im das gewicht pey dem tenckenn elpogñ |

[103r.4] Also prich das Merck wenn dir einer greift mit der lincken hant vorñ an dein prust so begreif ym sein lincke hant mit deiner lincken vnd nÿm Im das gewicht peÿ dem elpogen mit der rechten |

[89r.3] Also brich das Item wenn dir einer greifft vorn [89v.1] an die prust mit seiner lincken hant So begreiff Im sein lincke hant mit deiner lincken vnd reibe vmb vnd mit deiner rechten hant nÿm Im das gewicht pej dem lincken elenpogen. |

[123v.4] also pruch das wenn dir ainer greyfft vorn an die prust mit seiner tennckenn hannd so begreyff Im sein tenncke hannd mit seiner dencken vnd mit deiner rechtenn hand nym im das gewicht bey dem tencken elpogenn |

[55r.4] |

[120r.6] Also prich daß Itm~ Wen dir eyner griff vorn an din bru°st mit siner linckenn hantt So begriff ym syn lincke [120v.1] hant mit diner linckenn vnd reÿb vmb vnd mit diner rechte~ hantt nym ym dz gewÿchtt by dem linckenn elbogenn ~ |

[69r.4] Der prüch da wider Item / Wen dir ainer greifft vorñ an die prust mit seiner lincken hant / so begreiff im sein lincke hant mit deiner lincken vnd reib vmb vnd mit deiner rechtñ hant nÿm das gewicht peÿ dem lincken elpogñ |

[100v.18] Also brauch das Wen dir einer grifft var an die brust mit seiner l. hand so begriff Im sein lincke hand mit deiner l. hand vnd reyb vmb vnd mit deiner rechten hand nim das gewicht bey dem lincken ellenbogen |

[138r.1] also prich das Mergk wann dir ainer greift mit der lingken hant vornen an die prust so begreif im sein lingke hand mit deiner lingken und nim im das gwicht bey den elenbogen mit der rechtenn |

Also brich das. Item wenn dir einer greifft vorn an die prust mit seiner lincken hant So begreiff Im sein lincke hant mit deiner lincken vnd reibe vmb vnd mit deiner rechte hant nym Im das gewicht pej dem lincken elenpogen. |

[118v.1] Allso prich das Item wann dir ainner Greyfft. vornen ann die Prust. mit seinner linncken hand. so begreyff Im seinn linncken hannd mit deinner linncken vnnd treyb vmb vnd mit deinner Rechten hannd Nimb das. gewicht bey dem linncken ~ Elnpogen. |

[90r.3] Allso brich das. Item wann dir ainer greifft vornen an die brust, mit seiner linnggen hannd, so begreif ime sein lingge hannd, mit deiner linnggen, vnd treib vmb, vnnd mit deiner rechten hannd nimme das gewicht bej dem linnggen elenbogen. |

[295r.3] Destructio antecedentis Si quis pectus tuum manu sinsitra anterius adprehenderit tu manum adversarii laeva itidem tua corripito atque inde circumflectas eam dextra autem ei pondus auferas, id est cubitum laevum pro viribus sursum propellas. |

[104v.4] Destructio antecedentis. Si qu~is pectus tuum manu sinistra anterius adpraehenderit, tu manum adversarij, laeva itidem tua corripito, atque inde circumflectas eam, dextra autem ei pondus auferas, id est cubitum laevum pro viribus sursum propellas. |

||||||

[13] Or, if you rather, thrust his left elbow upwards with your right hand and turn him thus away from you. |

[13] [Another wrestling] Or thrust his left elbow straight up with your right arm and turn him away from you. |

[13] |

[13] |

[111v.2] Ain anders ringenn Oder stoß Im mit deiner rechtñ hant seine~ tencken ellpogñ vber sich vnd wendt in also von dir |

[103r.5] Oder stos Im mit dein° rechten hant seinen lincken elpogen slecht vber sich aus vñ wendt In also von dir ~ |

[89v.2] Item oder stos In mit deiner rechten hant seinen lincken elenpogen übersich vnd wend In also von dir etc. |

[123v.5] oder stos Im mit deiner rechtenn hannd denn tennckenn elpogen vbersich vnnd wennt in also vonn dier |

[55r.5] |

[120v.2] Item oder stos yn mit dyner rechten hant sinen linckenn elbogenn vbersich vnd wendt ÿn also von dir ~ |

[69r.5] Itm~ Oder stos Im mit deiner rechtñ hant seine~ lincken elpogñ vber sich / vnd wend in also von dir |

[100v.19] oder stoß Im mit deiner rechten hand sein lincken ellenbogen übersich vnd wend Im also von dir etc |

[138r.2] Oder stos im mit dainer rechtenn hant seinen lingken elenbogen schlecht ubersich aus und went in also von dirr |

Item oder stos mit deiner rechtē hant seinen lincken elenpogen über sich vnd wend In also von dir &c. |

[118v.2] Oder stosz In mit deinner Rechten hannd. seinnen. Linncken Elennpogen ybersich vnnd wennd In also von ~ Dir. |

[90v.1] Oder stosse ime, mit deiner rechten hannd, seinen linnggen elenbogen übersich, unnd wennd ine allso von dir. |

[295v.1] Vel si mavis, dextra manu sursum pellas cubitum hostilem sinistrum, atque ipsum adversarium abigas. |

[104v.5] Vel si mav~is, dextra manu sursum pellas cubitum hostilem sinistrum, atque ipsum adversarium abigas. |

||||||

[14] A device with moving your hand underneath his elbow and the counter to it When someone has taken hold of your left hand with his right and is about to move his left hand under your elbow in order to lock it, or, he wants use his right hand for support and turn in underneath it, when he moves his left hand towards his right for support, or towards the elbow, then move your right hand over his left on his right side and take hold of his rib, step behind his left foot with your right and throw him from your left foot over your left leg. |

[14] Remember this technique well as it breaks all wrestling derived from the first teaching described above When someone grabs your left arm with his right hand and seeks to grab your elbow from below with his left hand to twist your arm or if he tries to help his right hand with his other arm and turn through alongside the arm, pay attention: if he is strengthening his right arm with his left or if he wants to grab your elbow with it, move your right arm to his right side above his left arm, grab him around the body, spring with your right leg behind his left leg and throw him over your right thigh. |

[14] |

[14] |

[110r.6] Ain ander stuck Wenn dir ayner hat gefast sein tencke hant mit seiner rechtñ hant vnd wil mit seiner tencken hãt vndenn durch greiffñ an deine~ elbogñ vnd wil dir den verruckñ oder wil sein° rechtew hant czu hilff kome~ vnd sich durch den arm [110v.1] wendenn dÿ weil er mit der tenckenn hant der rechtñ czu hilff greifft oder nach dem elbogñ In dem selbenn so vor im mit deinem rechtenn arm obñ vber sein tenckenn in sein rechtew seytenn vnd vaß in In der wuest vnd spring mit dem rechtenn fueß hinter seine~ tenckñ fuß vnd wuff [!] In auß dem fuß vber dein rechcz pain etc |

[101v.4] Merck das stuck pricht alle ringen die von ersten an geschriben sten Item wenn dir ein° hat gefast dein lincke hant mit seiner rechten vnd wil mit sein° lincken vnden durch greiffen an deinen elpogen vnd wil dir den vorrencken oder wil seiner rechten hant zu° hilff chu~men vnd sich durch den arm~ wenden So merck die weil er mit der lincken der rechten zu° hilff greifft oder do mit nach dem elpogen greift in dem selben so var Im mit deine~ rechten arm~ vber sein lincken in sein rechte seitten vnd faß in In der wüst vnd spring mit dem rechten fuess hinder sein lincken vnd würff [102r.1] In aus dem fuess vber dein rechtz pain ~ |

[87r.1] Item Wann dir einer hat geuast dein lincke hant mit seiner rechten vnd will mit seiner lincken hant vntten durchfarn an deinem elenpogen vnd will dir den verrencken oder wil seiner rechten hant zuhilff kommen vnd sich durch den wenden die weil er mit der lincken der rechten zuhilff greiffet oder nach dem elenpogen In dem selben so far Im mit deinem rechten arm oben über sein lincken In sein rechte seitten vnd faß In In der wüst vnd spring mit deinem rechten fuß hintter sein lincken fuß vnd würff In auß dem lincken fuß über dein rechtes pein etc. |

[123r.8] Ein pruch wider die erstenn stuckh wenn dir ainer hat geuast dein tencke hannt mit seiner rechtenn vnd wil mit seiner tenncken vnden durch greyffenn an dein elpogen vnd wil dir denn ver rencken oder wil seiner rechtenn hand zw hilf chumenn vnd sich durch durch [!] denn arm wennden die weyl er mit dem rechtenn der tennckenn ze hilf greyff oder nach dem elpogenn In dem selbenn far im mit deinem rechtenn arm oben vber sein tennckenn vnnd vaß in In der wüest vnd spring mit deinem rechtenn fueß hinder seinenn tennckenn vnd würff in aus dem fueß vber dein rechtz pain |

[54r.4] |

[120v.3] Itm~ wan dir eÿner hat gefast din lincke hantt mitt siner rechtenn vnd will mit siner lincken hantt vnden durch griffenn an dinen elbogenn vnd will den verrenckenn oder will siner rechte~ zu hilff kümenn vnd sich durch dy wenden die weyll er will mit der lincken der rechten zu hilff griffett oder noch dem elnbogenn In dem selben so var ym mit dynen rechte~ arm oben vber sin lincken in syn rechte sytenn vnd vaß yn by der wuste vnd spring mit dine~ rechte~ fuß hynder synen lincken fuß vnd wurff yn usser dem fuß vber dyn rechtes peyn ~ |

[68r.3] Ein pruch wider die erstñ Stuck Item Wen dir ainer hat gefast dein lincke handt mit seiner rechtñ / vnd wil mit seiner lincken handt vndtñ durch greiff an deine~ elpogñ / vnd wil dir den verrencken / Oder wil seiner rechtñ handt zu hilff kume~ vnd sich durch den arm~ wendñ / So merck die weil er mit der lincken der rechtñ zu hilff greifft / Oder nach dem elpogñ in dem selbñ / so far im mit deine~ rechtñ arm~ oben vber sein lincke~ in sein rechte seittñ / vnd faß In in der wust / vnd spring mit deine~ rechtñ fues hindter sein lincken fuß / vnd wurff in auß dem fues vber dein rechts pain / |

[134r.2] Das stuck pricht alle ringen die von ersten an geschriben sten [W]ann dir ainer hat gefast dein lingke hannt mit seiner rechtenn unnd wil mit seiner lingkhen unnden durch greiffenn ann deinen elenpogen unnd will dir denn verreruckenn[!] oder will seiner rechtn hant zu hilf khumenn unnd sich durch den arm wennten, so mergk dieweil er mit der lincken der[25] rechtenn zu hilff greifft[26] oder domit nach dem elnnpogen greifft, im dem selbenn, so far im mit dainem rechten arm behendiglich uber seinen lingkenn in sein rechte seytenn unnd fas in in der wuest ~ Unnd spring mit dem rechtenn fus hinder seinenn lingkhenn unnd wirff in aus dem vues ÿber dain rechts pain ~ Wiedann hernach gemalt. |

Ein anders wann dir einer hat genast dein lincke hant mit seiner recht‾ vnd will mit seiner linken hant vntten durch greiffen an deinem elenpogen vnd will dir den vrrencken oder wil seiner rechten hant zuhilff kom̄en vnd sich durch den winden die weil er mit der lincken der rechten zuhilff greiffet oder nach dem elenpogen In dēselben so far Im mit deinem rechtē arm oben über sein lincken In sein rechte seitten vnd faß In In dr wieste vnd spring mit deinem rechten fuß hintter sein lincken fuß vnd würff In auß dem lincken fuß über dein rechtes pein &c. |

[116r.2] Vnden durch Faren. Item wann dir ainner hat fasst dein Linnckhannd. mit seinner Rechten. vnnd will mit seiner linncke hannd vnnden durch faren. an deinnen Elenpogen vnnd will dir den verzenncken. oder seinner rechten hannd. zu hillf kommen. vnnd sich durch den wennden Dieweil er mit der linncken der rechten zu hillf greifft. oder nach dem Elennpogen Inn dem selben so far Im mit deinnem rechten arm. aber vber sein linncke. Inn seinn rechte seitten. vnnd fasz In Innder wust. vnnd spring mit deinnem Rechten fuosz hinnder sein linncken. vnnd wirff In ausz dem Linncken fusz vber dein rechtes pain. |

[88v.2] Unndten durchfarn. Item Wann dir ainer hat gefasst, dein linngee hand mit seiner rechten, unnd will mit seiner linngeen hannd unndten durchfarn, an deinen elebogen, unnd will der den verrenncken, oder seiner rechten hand zu hilf kommen, unnd sich durch den wennden, dieweil er mit der linnggen der rechten zu hilf greifft, oder nach deinr elenbogen, In denselben, so fare ime mit deinem rechten arm, aber über seinen linnggen, in seinen rechte seitten, unnd fasse im, in der wüsten unnd sprinng mit deinem rechten fuß hinndter seinen linnggen, unnd wirf ine auß dem linngen fuß über dein rechtes bain. |

[293v.2] Ratio transmittendi manum inferne ad cubitium atque eiusdem destructio Quum quispiam manum sinistram tuam corripuerit dextra coneturque inferne sinistram transmittere in cubitum, eumque circumflectere vel cupiat dextrae manui opem ferre, tu igitur dum is dextrae auxiliari molitur sinistra vel cubitum corripere conatur, subito brachium tuum dextrum sinisto hostis brachio superiniicias, laterique dextro adplices nec non firmiter corripito manu eadem costas, post dextrum pedem pedi hostis sinistro postponas atque per dextrum hostem prosternas. |

[104r.10] Ratio transmittendi manum inferne ad cu~bitum, atque eiusdem destructio. Quum quispiam manum sinistram tuam corripuerit dextra, coneturque infernè sinstram transmittere in cubitum, eumque circumflectere, vel cupiat dextrae manui oper?e ferre, tu igitur, dum is dextrae auxiliari molitur sinistra, vel cubitum corripere conatur, subito brachium tuum dextrum, sinistro hostis brachio superinijcias, laterique dextro adplices, nec non firmiter corripito manu eadem costas, post dextrum pedem, pedi hostis sinistro postponas, atque per dextrum hostem prosternas. |

|||||||

[15] When someone grabs your arm forcefully When someone takes hold of your arm, and holds it hard, so that you cannot do anything, then move your right arm outside over his left arm near by his hand and grab hold with your left on your right, and press down his hand with both your hands firmly to your chest. |

[15] Another wrestling When someone grabs your upper arm with strength, holds you firmly and wants to push you, reach with your right hand from the outside over his arm, grab your right arm with your left hand and press his arm strongly onto your chest with both arms. |

[15] |

[15] |

[110v.2] Ein Ander Stuck Greyfft dich einer obenn an in den armenn mit sterck vnd helt dich vest vnd wil dich ringñ so vwar mit deine~ rechtñ arm võrn aussen vber seine~ tenckenn arm vorn pain seiner hant vnd pegreiff mit seiner der tenckñ dein rechte vnd druck mit paydenn sein hant vast an dÿ prust |

[102r.2] Aber ein Ringen Item greift dich ainer an oben in die arm~ mit sterck vnd helt dich vest vnd wil dich dringen So far mit deinem rechten arm~ aussen vber sein lincken vorñ peÿ seiner hant vnd begreif mit deiner lincken hant dein rechte vnd druch mit paiden henden sein hant fast an dein prust |

[87r.2] Item Greifft dir einer oben In die arm mit sterck vnd hat dich vest vnd wil dich dringen So far mit deinem rechten arm aussen über sein lincken arm vorn pej seiner [87v.1] hant vnd begreiff mit der lincken dein rechte vnd druck mit beden sein hant vast an dein prust |

[123r.9] Wenn dich ainer an greyft obenn in die arm mit sterck vnnd helt dich vest vnd wil dich dringen so far im mit deinem rechten arm von aussenn vber sein tennckenn vorn bey seiner hand vnd begreyff mit der tencken sein rechte vnd druck mit paidenn henndenn fest ann die prüst |

[54r.5] |

[120v.4] Item Grifft dich eÿner an oben In die sterck vnd helt dich vast vnd will dich tringe~ So far mit dinem rechte~ arm aussen vber synen lincken arm vorn by syner hantt vnd begriff mit der lincken den rechtenn vnd trück mit beÿdenn synen hendenn vast an dyn bru°st ~ |

Greifft dich einer oben an neben die arm mit sterck vnd helt dich vest vnd wil dich daugen So far mit deinem rechten arm aussen über sein lincken arm pej seiner hant vnd begreiff mit der lincken sein rechte vnd druck mit beden sein henden vast an die brust. |

[116v.1] So dir ainner mit Sterckh Inn arm greifft. Item greyft dir ainner oben Inn die arm mit sterckh. vnnd hat dich veest vnnd will dich trinngen. so far mit deinnem rechten arm auszen vber sein linncken arm vornen bey seiner hannd vnnd begreiff mit der linncke dein Rechte vnnd truckh mit baiden hennden seinn hannd fast an dein prust. |

[88v.3] So dir ainer mit sterkin arm greifft. Item Greifft dir ainer oben in die Armen, mit sterck, unnd hat dich fesst, und will dich drinngen, So fare [89r.1] mit deinem rechten arm aussen über seinen linnggen arm, vorrnen bei seiner hannd, unnd begreif mit der linnggen dein rechte unnd druck mit bedenn hennden sein hannd fasst an dein brus~t. |

[293v.3] Destructio cum quis pro viribus brachium corripiat Si quis superne brachia tua totis viribus corripiat fortiterque [294r.1] teneat, nec non coartare conetur, tum brachium dextrum tuum superiniicias adversarii sinistro externe iuxta ipsius manum sinistra autem dextram tuam corripias, atque post manu utraque ipsius manum firmiter adprimas pectori. |

[104r.11] Destructio, cum is quis pro Viribus brachium corripiat. Si quis supernè brachia tua totis viribus corripiat, fortiterque teneat, nec non coartare conetur, tum brachium dextrum tuum superinijcias adversarij sinistro externè iuxta ipsius manum, sinistra autem dextram tuam corripias, atque pòst manu utraque, ipsius manum firmiter adprimas pectori. |

|||||||||

[16] Pay attention to your opponent's fingers If your opponent extends his fingers on the hand that you have pressed to your chest, then grip them with your left hand. Then heave him upwards to your left, and with your right hand lock him by the elbow. |

[16] |

[16] |

[110v.3] Streckt er dy vinger an der hant dÿe du Im an dy prust prust [!] druckst so greiff Im dy vinger mit deiner tenckñ hant vnd heb vber sich auf dein tenckñ seytenn vnd mit der rechtñ hendt ny~ Im das gewicht bey dem elbogenn |

[102r.4] Ein anders ·M·erck wenn du Im mit deinen paiden henden sein hant vorñ an dein prust druckst helt er denn die hant offen vnd reckt die finger So begreif In peÿ den fingerñ mit dein° lincken hant vnd heb vbersich auf dein lincke seitten vnd mit der rechten hant nÿm Im das gewicht peÿ dem elpogen ~

|

[87v.2] Item strecket er dir die vinger an der hant die du Im an der prust druckest So greiff Im In die vinger mit deiner lincken hant vnd heb übersich auf dein lincke seitten vnd mit der rechten hant nÿm das gewicht bej dem elenpogen. |

[123r.10] wenn er streckt die finger an der hannd die dw im an prust druckst so greyff Im die vinger mit deiner tennckenn hand vnd heb vbersich auf dein tenncke seytenn vnd mit der rechtenn hannd nym im das gewicht bey dem elbogenn |

[54r.6] [54v.1] |

[121r.1] Item Streck er dir die finger an din hantt die du Im an die brust truckest so griff in dye finger mit diner lincken hantt vnd heb vber sich auff dyn lincke siten vnd mit der rechten hant In daß gewiechtt bÿ dem elnbogenn ~ |

[68v.1] Itm~ Streckt er die finger an der handt / die du Im an sein prust druckst / So greiff im die finger mit deiner linckñ handt vnd heb vbersich auff dein lincke seÿttñ / vnd mit der rechtñ handt nym im das gewicht peÿ dem elpogen |

Bruch. Item strecket er dir die vinger an der hant die du Im an der prust druckest So begreiff die fingr mit deiner lincken hant vnd heb übersich auf dein lincke seitten vnd mit der rechtē hant nym Ime das gewicht bej dē elenpogen. |

[116v.2] Auf die finger Zu mercken Item streckt er die finnger ann der hand Die du Im an der prust truckest. so greiff Im Inn die Finnger. mit deiner Linncken hannd. vnnd heb vbersech auf deinn Linncken seiten vnnd mit der Rechten hannd nim das gewicht bey dem Elnpogen. |

[89r.2] Auf die Finngerzumercken. Item streckt er der finnger an der hannd, du du an der brust ime druckest, so greif ime in die dinnger mit deiner linnggen hannd vnnd heb über sich auf dein linngge seitten, vnnd mit der rechten hannd nime das gewicht, bei dem elenbogen. |

[294r.2] Ratio observandorum digitorum hostis Quum adversarius digitos eius manus quam pectori admovisti porrexerit, tunc eos corripito manu sinistra. Inde, sinistrorsum subleves, atque dextra pondus illi auferas iuxta cubitum, id est, sursum torqueas cubitum. |

[104r.12] Ratio observandorum digitorum hostis. Quum adversarius digitos eius manus, quam pectori admovisti, porrexerit, tunc eos corripito manu sinistra, inde sinistrorsum subleves, atque dextra pondus illi auferas iuxta cubitum, id est, sursum torqueas cubitum. |

|||||||||

[17] If he holds his hand on your chest If he holds the hand on your chest, then step behind with left foot with your right and grab with your left hand at the back of his left knee and lift up, and with your right hand push him away from you, then he will fall. |

[17] |

[17] |

[110v.4] Helt er aber dy hant czue an der prust so spring mit dem rechtñ fueß hinter sein tenckñ vnd greiff mit der tencken hant In dye knyepug seines tencken fueß vnd heb da mit auff vnd mit der rechten hant stoß In obm~ võ dir so velt er |

[102r.3] Merck hat er dÿ hant zu° an deiner prust so spring mit dem rechten fuess hinder sein lincken vnd greif im mit dein° lincken hant in die knÿepüg seines lincken fuess vnd heb do mit auf vnd mit der rechten hant stos in oben von dir so felt er ~ |

[87v.3] Item helt er aber die hant zu an deiner prust So spring mit deinem rechten fuß hintter seinen lincken vnd greiff mit deiner lincken in die kniepiegung seins lincken fusses vnd heb damit auf vnd mit der rechten hant stos In oben von dir So vellet er. |

[123r.11] Item helt er aber die hannt zu deiner prüst so spring mit dem rechtenn hinder seinen tenncken vnd begreyff mit deiner tencken In die chnyepüg seins tennckenn fueß vnd heb domit auf vnnd mit der rechtenn stoß in oben vonn dir//so felt er |