|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Joachim Meyer"

| Line 1,438: | Line 1,438: | ||

| class="noline" | <p>Thus you understand that the third part of fencing is nothing other than the right Practice, as was reported above, the first two Lead parts in fencing, which will be taught though Practice, where you change at every opportunity, namely in the first Lead Part with the stances and strikes, flowing off, changing through, flying off, and letting miss. That such strikes can be trapped with displacement and clearing, likewise in the second Lead Part, displacement, teach the Practice of how you displace, follow after him, cut, punch, etc. Therewith you will end the strikes that he sends to you, or at the least prevent them from reaching their intended destination. And that is the sum of all Practice, namely that you firstly engage your opposing fencer through the stances, with manly strikes and without damage to your target, by showing cunning and agile misleading as can be shown, and after you then engage him to break through with the obligatory or similar handwork, from which you either securely withdraw at your pleasure, or where he must retreat from you and you follow ahead after him. Since going forward such Practice will be needed and extended in many arts to be the same both in name and in fencing, as you found fully described before here in the handwork chapter, I will now drive further to describe fencing from the stances.</p> | | class="noline" | <p>Thus you understand that the third part of fencing is nothing other than the right Practice, as was reported above, the first two Lead parts in fencing, which will be taught though Practice, where you change at every opportunity, namely in the first Lead Part with the stances and strikes, flowing off, changing through, flying off, and letting miss. That such strikes can be trapped with displacement and clearing, likewise in the second Lead Part, displacement, teach the Practice of how you displace, follow after him, cut, punch, etc. Therewith you will end the strikes that he sends to you, or at the least prevent them from reaching their intended destination. And that is the sum of all Practice, namely that you firstly engage your opposing fencer through the stances, with manly strikes and without damage to your target, by showing cunning and agile misleading as can be shown, and after you then engage him to break through with the obligatory or similar handwork, from which you either securely withdraw at your pleasure, or where he must retreat from you and you follow ahead after him. Since going forward such Practice will be needed and extended in many arts to be the same both in name and in fencing, as you found fully described before here in the handwork chapter, I will now drive further to describe fencing from the stances.</p> | ||

| class="noline" | | | class="noline" | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/80|3|lbl=Ⅰ.30r.3|p=1}} | + | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/80|3|lbl=Ⅰ.30r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/81|1|lbl=Ⅰ.30v.1|p=1}} |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,455: | Line 1,455: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | '''Fencing from the Stances | + | | '''Fencing from the Stances''' |

| + | |||

| + | Chapter 11 | ||

| + | |||

Since much now concerns the Stances, I will thus not keep you long in each for the same reason they were given still only half composed, but going onward, since you will need to know, when you present your sword and (while you are twitching off the guard he aimed to you) you would strike, as soon as you come out from the farthest point (where you have begun to pull back your sword), then from here on you should lead your sword against him again with agility, like how it will be handled from the Guard of the Roof, the Guard through which you bring about the Downstrike. Thus when you move to the Downstrike (to do such) you will then in the outermost point of this move come to be in the guard named Roof, you can now not only (just as you seek to strike) strike then and thus drive ahead with your Downstrike, but can also persist to stay. This is the reason, namely just that you not yet undertake any strike unplanned, but even as soon you have allowed the same considered strike to be drawn against them, you should now lead the strike on from even from here so that as you stay for only an eyeblink at the obvious outermost point, so consider ahead if your chosen strike can either still be led usably to fulfillment, or if through it you can attain a better opportunity applicable elsewhere, where you thus change to a second strike accordingly at the outermost point and thus conclude the Downstrike which you have drawn out with a Traverse. This is the underlying reason for the development of the Stances and is why you stay while in one Guard: to see what the other will take ahead (and then rightly know how to overtake his chosen part) and prevent such just by being certain to see here what his chosen part will be, and such waiting is a great art and experience. Because you now need to know onward how to engage your opponent’s oncoming strikes from the Roof with your Sword, I have set the following examples both of when he would strike, or stay and not strike. | Since much now concerns the Stances, I will thus not keep you long in each for the same reason they were given still only half composed, but going onward, since you will need to know, when you present your sword and (while you are twitching off the guard he aimed to you) you would strike, as soon as you come out from the farthest point (where you have begun to pull back your sword), then from here on you should lead your sword against him again with agility, like how it will be handled from the Guard of the Roof, the Guard through which you bring about the Downstrike. Thus when you move to the Downstrike (to do such) you will then in the outermost point of this move come to be in the guard named Roof, you can now not only (just as you seek to strike) strike then and thus drive ahead with your Downstrike, but can also persist to stay. This is the reason, namely just that you not yet undertake any strike unplanned, but even as soon you have allowed the same considered strike to be drawn against them, you should now lead the strike on from even from here so that as you stay for only an eyeblink at the obvious outermost point, so consider ahead if your chosen strike can either still be led usably to fulfillment, or if through it you can attain a better opportunity applicable elsewhere, where you thus change to a second strike accordingly at the outermost point and thus conclude the Downstrike which you have drawn out with a Traverse. This is the underlying reason for the development of the Stances and is why you stay while in one Guard: to see what the other will take ahead (and then rightly know how to overtake his chosen part) and prevent such just by being certain to see here what his chosen part will be, and such waiting is a great art and experience. Because you now need to know onward how to engage your opponent’s oncoming strikes from the Roof with your Sword, I have set the following examples both of when he would strike, or stay and not strike. | ||

| − | | | + | | |

| − | + | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/81|2|lbl=Ⅰ.30v.2|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf|82|lbl=Ⅰ.31r|p=1}} | |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 1,464: | Line 1,467: | ||

| '''The First Part''' | | '''The First Part''' | ||

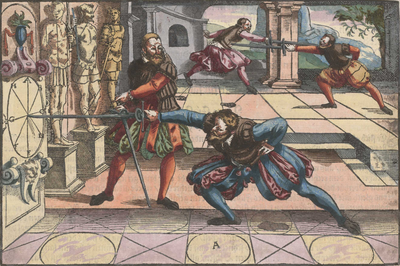

And firstly when you come before your opponent and, while striking out or otherwise pulling your sword back (to downstrike) to bring it high above you, he strikes just then to your left at your head, then burst full away from his strike against his left and somewhat toward him, and strike with an outward flat against his incoming strike to meet his sword strongly on the strong so that the forward part of your blade will swing inward over his sword to his head, which is then certainly hit. When you slash at the same time as him and your sword comes to be over his, to hit or not on his strike, then twitch your sword off over yourself again, and strike diagonally upward from below to his right arm, in this strike step out with your left foot full against his right side and arc yourself with your head fully behind your sword’s blade, from there nimbly twitch again upward and flit the short edge to his left ear, if you see that he will wipe against this, then don’t let the impact fail or flow off, but soon cross your hands in the air (the right over the left) and slash him with the short edge deep to his right ear and then traverse over and pull out. Mark here when he would nimbly follow after the Understrike just taught and thus would be hard onto the roof so that you can’t come to flow off, then pay attention just then if he would twitch off from your sword, then follow after him with a cut to the arm. | And firstly when you come before your opponent and, while striking out or otherwise pulling your sword back (to downstrike) to bring it high above you, he strikes just then to your left at your head, then burst full away from his strike against his left and somewhat toward him, and strike with an outward flat against his incoming strike to meet his sword strongly on the strong so that the forward part of your blade will swing inward over his sword to his head, which is then certainly hit. When you slash at the same time as him and your sword comes to be over his, to hit or not on his strike, then twitch your sword off over yourself again, and strike diagonally upward from below to his right arm, in this strike step out with your left foot full against his right side and arc yourself with your head fully behind your sword’s blade, from there nimbly twitch again upward and flit the short edge to his left ear, if you see that he will wipe against this, then don’t let the impact fail or flow off, but soon cross your hands in the air (the right over the left) and slash him with the short edge deep to his right ear and then traverse over and pull out. Mark here when he would nimbly follow after the Understrike just taught and thus would be hard onto the roof so that you can’t come to flow off, then pay attention just then if he would twitch off from your sword, then follow after him with a cut to the arm. | ||

| − | | | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/83|1|lbl=Ⅰ.31v.1}} |

| − | |||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 1,471: | Line 1,473: | ||

| '''The Second Part''' | | '''The Second Part''' | ||

However if he strikes at your left from below, then step quickly out to his left and strike with the long edge onto the strong of his sword, as soon as your sword moves or glides on his, twitch your sword high above yourself again and slash down with the short edge quickly and deeply to his left ear while stepping forward out to his left, he will then want to rush to displace and then drive above against it, so then strike nimbly with the long edge over again to his right ear and in this slashover step full against his right like before, yet stay with the cross high over your head, and mark as soon as he slashes over then fall further with a cut to his arm, if he is not hurt by this but would evade your work, then follow after him (staying on his arm), and when he makes the smallest extraction, then let fly to another opening and strike him away from you. | However if he strikes at your left from below, then step quickly out to his left and strike with the long edge onto the strong of his sword, as soon as your sword moves or glides on his, twitch your sword high above yourself again and slash down with the short edge quickly and deeply to his left ear while stepping forward out to his left, he will then want to rush to displace and then drive above against it, so then strike nimbly with the long edge over again to his right ear and in this slashover step full against his right like before, yet stay with the cross high over your head, and mark as soon as he slashes over then fall further with a cut to his arm, if he is not hurt by this but would evade your work, then follow after him (staying on his arm), and when he makes the smallest extraction, then let fly to another opening and strike him away from you. | ||

| − | | | + | | |

| − | + | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/83|2|lbl=Ⅰ.31v.2|p=1}} '''[XXXIIr]''' Kopff / und merck als bald er umbschlecht / so fall jhm mit dem Schnit abermal auff die Arm / will er den auch nit leiden / sonder will sich ledig arbeiten / so volg jhm (auff seinen Armen bleibent) nach / und wann ers am wenigsten versihet / so laß abfliegen einer andern Blöß zu / und hauw dich von jhm ab. | |

|- | |- | ||

Revision as of 15:37, 12 April 2021

| Joachim Meyer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | ca. 1537 Basel, Germany |

| Died | 24 February 1571 (aged 34) Schwerin, Germany |

| Spouse(s) | Appolonia Ruhlman |

| Occupation |

|

| Citizenship | Strasbourg |

| Patron |

Heinrich von Eberst (?)

|

| Movement | Freifechter |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Early New High German |

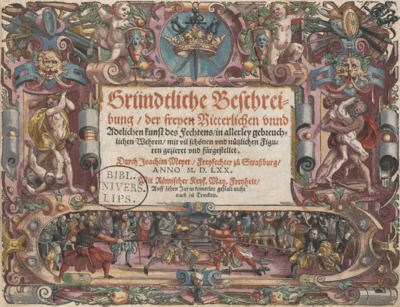

| Notable work(s) | Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (1570) |

| Manuscript(s) |

|

| First printed english edition |

Forgeng, 2006 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

| Signature | |

Joachim Meyer (ca. 1537 - 1571)[1] was a 16th century German Freifechter and fencing master. He was the last major figure in the tradition of the German grand master Johannes Liechtenauer, and in the last years of his life he devised at least three distinct and quite extensive fencing manuals. Meyer's writings incorporate both the traditional Germanic technical syllabus and contemporary systems that he encountered in his travels, including Italian rapier fencing.[2] In addition to his fencing practice, Meyer was a Burgher and a master cutler.[3]

Meyer was born in Basel,[4] where he presumably apprenticed as a cutler. He writes in his books that he traveled widely in his youth, most likely a reference to the traditional Walz that journeyman craftsmen were required to take before being eligible for mastery and membership in a guild. Journeymen were often sent to stand watch and participate in town and city militias (a responsibility that would have been amplified for the warlike cutlers' guild), and Meyer learned a great deal about foreign fencing systems during his travels. It's been speculated by some fencing historians that he trained specifically in the Bolognese school of fencing, but this doesn't stand up to closer analysis.[5]

Records show that by 4 June 1560 he had settled in Strasbourg, where he married Appolonia Ruhlman (Ruelman)[1] and was granted the rank of master cutler. His interests had already moved beyond smithing, however, and in 1561, Meyer petitioned the City Council of Strasbourg for the right to hold a Fechtschule (fencing competition). He would repeat this in 1563, 1566, 1567 and 1568;[6] the 1568 petition is the first extant record in which he identifies himself as a fencing master.

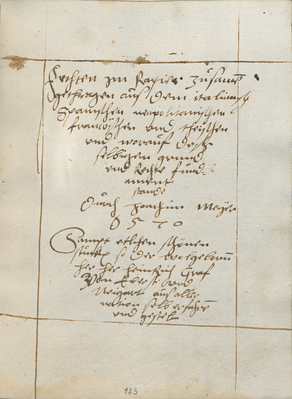

Meyer probably wrote his first manuscript (MS A.4º.2) in either 1560 or 1568 for Otto Count von Sulms, Minzenberg, and Sonnenwaldt.[7] Its contents seem to be a series of lessons on training with long sword, dussack, and rapier. His second manuscript (MS Var.82), written between 1563 and 1570 for Heinrich Graf von Eberst, is of a decidedly different nature. Like many fencing manuscripts from the previous century, it is an anthology of treatises by a number of prominent German masters including Sigmund ain Ringeck, pseudo-Peter von Danzig, and Martin Syber, and also includes a brief outline by Meyer himself on a system of rapier fencing based on German Messer teachings. Finally, on 24 February 1570 Meyer completed (and soon thereafter published) an enormous multi-weapon treatise entitled Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens ("A Thorough Description of the Art of Combat"); it was dedicated to Johann Casimir, Count Palatine of the Rhine, and illustrated at the workshop of Tobias Stimmer.[8]

Unfortunately, Meyer's writing and publication efforts incurred significant debts (about 1300 crowns), which Meyer pledged to repay by Christmas of 1571.[1] Late in 1570, Meyer accepted the position of Fechtmeister to Duke Johann Albrecht of Mecklenburg at his court in Schwerin. There Meyer hoped to sell his book for a better price than was offered locally (30 florins). Meyer sent his books ahead to Schwerin, and left from Strasbourg on 4 January 1571 after receiving his pay. He traveled the 800 miles to Schwerin in the middle of a harsh winter, arriving at the court on 10 February 1571. Two weeks later, on 24 February, Joachim Meyer died. The cause of his death is unknown, possibly disease or pneumonia.[6]

Antoni Rulman, Appolonia’s brother, became her legal guardian after Joachim’s death. On 15 May 1571, he had a letter written by the secretary of the Strasbourg city chamber and sent to the Duke of Mecklenburg stating that Antoni was now the widow Meyer’s guardian; it politely reminded the Duke who Joachim Meyer was, Meyer’s publishing efforts and considerable debt, requested that the Duke send Meyer’s personal affects and his books to Appolonia, and attempted to sell some (if not all) of the books to the Duke.[1]

Appolonia remarried in April 1572 to another cutler named Hans Kuele, bestowing upon him the status of Burgher and Meyer's substantial debts. Joachim Meyer and Hans Kuele are both mentioned in the minutes of Cutlers' Guild archives; Kuele may have made an impression if we can judge that fact by the number of times he is mentioned. It is believed that Appolonia and either her husband or her brother were involved with the second printing of his book in 1600. According to other sources, it was reprinted yet again in 1610 and in 1660.[9][10]

Contents

- 1 Treatises

- 1.1 Dedication and Foreword

- 1.2 Sword

- 1.2.1 Contents

- 1.2.2 1 - Of Man and His Divisions

- 1.2.3 2 - Of the Sword and its Divisions

- 1.2.4 3 - Of the Stances or Guards

- 1.2.5 4 - Of The Strikes

- 1.2.6 5 - Of Displacing

- 1.2.7 6 - Of the Withdrawal

- 1.2.8 7 - A Lesson in Stepping

- 1.2.9 8 - Of Before, After, During, and Indes

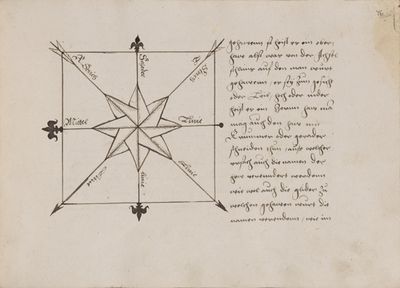

- 1.2.10 9 - A Guide to the Elements

- 1.2.11 10 - How one shall fence to the four Openings

- 1.2.12 11 - Fencing from the Stances

- 1.2.13 Third Part/Lund

- 1.3 Dussack

- 1.4 Rapier

- 1.5 Additional cutting diagrams

- 1.6 Dagger

- 1.7 Polearms

- 1.8 Copyright and License Summary

- 2 Additional Resources

- 3 References

Treatises

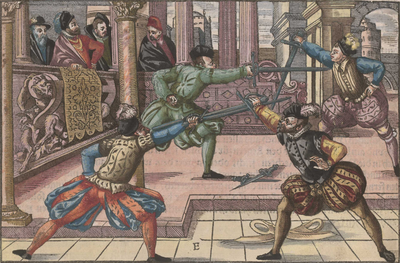

Joachim Meyer's writings are preserved in two manuscripts prepared in the 1560s, the MS A.4º.2 (Lund) and the MS Var 82 (Rostock); a third manuscript from 1561 has been lost since at least the mid-20th century, and its contents are unknown.[11] Dwarfing these works is the massive book he published in 1570 entitled "A Thorough Description of the Free, Chivalric, and Noble Art of Fencing, Showing Various Customary Defenses, Affected and Put Forth with Many Handsome and Useful Drawings". Meyer's writings purport to teach the entire art of fencing, something that he claimed had never been done before, and encompass a wide variety of teachings from disparate sources and traditions. To achieve this goal, Meyer seems to have constructed his treatises as a series of progressive lessons, describing a process for learning to fence rather than merely outlining the underlying theory or listing the techniques. In keeping with this, he illustrates his techniques with depictions of fencers in courtyards using training weapons such as two-handed foils, wooden dussacks, and rapiers with ball tips.

The first part of Meyer's treatise is devoted to the long sword (the sword in two hands), which he presents as the foundational weapon of his system, and this section devotes the most space to fundamentals like stance and footwork. His long sword system draws upon the teachings of Freifechter Andre Paurñfeyndt (via Christian Egenolff's reprint) and Liechtenauer glossators Sigmund ain Ringeck and Lew, as well as using terminology otherwise unique to the brief Recital of Martin Syber. Not content merely to compile these teachings as his contemporary Paulus Hector Mair was doing, Meyer sought to update—even reinvent—them in various ways to fit the martial climate of the late sixteenth century, including adapting many techniques to accommodate the increased momentum of a greatsword and modifying others to use beats with the flat and winding slices in place of thrusts to comply with street-fighting laws in German cities (and the rules of the Fechtschule).

The second part of Meyer's treatises is designed to address new weapons gaining traction in German lands, the dussack and the rapier, and thereby find places for them in the German tradition. His early Lund manuscript presents a more summarized syllabus of techniques for these weapons, while his printed book goes into greater depth and is structured more in the fashion of lesson plans.[12] Meyer's dussack system, designed for the broad proto-sabers that spread into German lands from Eastern Europe in the 16th century,[13] combines the old Messer teachings of Johannes Lecküchner and the dussack teachings of Andre Paurñfeyndt with other unknown systems (some have speculated that they might include early Polish or Hungarian saber systems). His rapier system, designed for the lighter single-hand swords spreading north from Iberian and Italian lands, seems again to be a hybrid creation, integrating both the core teachings of the 15th century Liechtenauer tradition as well as components that are characteristic of the various regional Mediterranean fencing systems (including, perhaps, teachings derived from the treatise of Achille Marozzo). Interestingly, Meyer's rapier teachings in the Rostock seem to represent an attempt to unify these two weapon system, outlining a method for rapier fencing that includes key elements of his dussack teachings; it is unclear why this method did not appear in his book, but given the dates it may be that they represent his last musings on the weapon, written in the time between the completion of his book in 1570 and his death a year later.

The third part of Meyer's treatise only appears in his published book and covers dagger, wrestling, and various pole weapons. His dagger teachings, designed primarily for urban self-defense, seem to be based in part on the writings of Bolognese master Achille Marozzo[14] and the anonymous teachings in Egenolff, but also include much unique content of unknown origin (perhaps the anonymous dagger teachings in his Rostock manuscript). His staff material makes up the bulk of this section, beginning with the short staff, which, like Paurñfeyndt, he uses as a training tool for various pole weapons (and possibly also the greatsword), and then moving on to the halberd before ending with the long staff (representing the pike). As with the dagger, the sources Meyer based his staff teachings on are largely unknown.

The long sword material in the Lund manuscript closely mirrors the "Third Part" of Meyer's Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens, so they are both included in the compilation below. Though the current translation is based on the Lund, in the future we will expand it with a full translation of both, footnoting the differences.

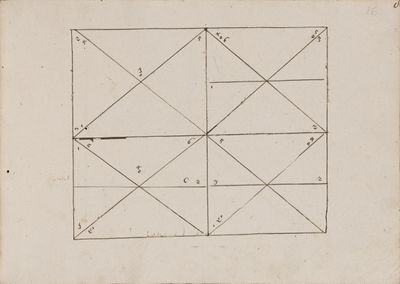

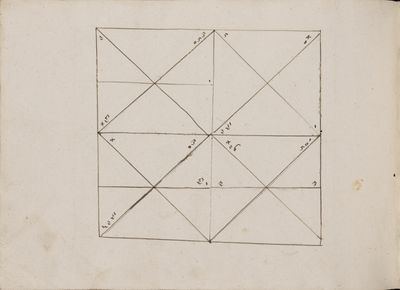

Figures |

||

|---|---|---|

Figures |

||

|---|---|---|

The fifth and last part of this book, in which will be taught and briefly handled the fencing of the Staff, the Halberd, and the Long Spear.

|

[Ⅲ.16r] Das fünffte und letste theil dises Buchs in welchem gelehrt und auffs kürtzest gehandelt wirt, von dem Fechten in der Stangen, Helleparten, unnd vom langen Spieß. DIse drey Wehr hab ich derenhalben zusamen in ein Figur gatiert, dieweil der Spieß seiner lenge halben und nach der perspectiva sich also oben in Figuren am besten geschickt hat, derenhalben dieweil dann ein jede Figur wie bißher auch geschehen, mit einem sondern Buchstaben vermerckt, sol sich der fleissige Leser das nicht irren lassen, unnd wil also die halbe Stangen als ein Fundament aller langen Wehren, zum ersten für die hand nemen, und erstlich anzeigen wie vil der Leger, demnach wie du dieselbigenins werck richten solt, lehren und beschreiben. | |

Of the Lyings or Guards. There are five principal lyings, namely the Upper Guard, straight upward before you outstretched and to both sides; the Lower Guard also to both sides; furthermore you thus also have two Near Guards and a Middle Guard; lastly the Tiller Guard. |

Von den Legern oder Huten. DEr Leger aber sein fürnemlich fünffe, nemlich die Oberhut, gerad ubersich vor dir außgestreckt unnd zu beiden seiten, demnach die Underhut auch zu beiden seiten, ferner so hastu auch zwo Nebenhuten und ein Mittelhut, letstlich die Steirhut. | |

Upper Guard Arrange yourself in the Upper Guard like this: stand with the left foot forward and hold your staff with the rear part at your chest, so that the fore end stands straight up toward the sky. You should direct it to both sides in the Work, like you are now doing it straight in front of you. If you shall always stand well with the left foot forward, then you must not have your feet too far apart, so that you could always have a step forward. |

[Ⅲ.16v] Oberhut. IN die Oberhut schicke dich also, stand mit dem Lincken fuß vor, halt dein Stangen mit dem hinderen theil an deiner Brust, also das der vordern ort gerad ubersich gegen dem Himmel stande, wie du nun solche gerad vor dir anschickest, also soltu sie auch zu beiden seiten in das werck richten, und ob du wol alwegen mit dem Lincken fuß vor bleiben solt, so mustu doch mit den füssen nicht zu weit von einander komen, auff das du mit dem Lincken fuß alwegen ein fürtrit haben könnest. | |

Lower Guard Do it like this: stand with your left foot forward and hold your staff with the rear part at your flank and with the fore end outstretched in front of you on the ground. When you hold the butt at your right flank like this it is the same, whether you hold or direct the point outstetched to left or right or straight ahead; whichever you may change to, either after his thrust, or after your techniques are performed. |

Underhut. DIe mach also, stand aber mit dem Lincken Fuß vor, halt dein Stangen mit dem hindern ort an deiner Weiche, und mit dem vordern ort vor dir außgestreckt auff die erden, wann du nun also den hindern ort an deiner rechten Weiche behaltest, so gilt es demnach gleich ob du den vordern ort zur Lincken oder Rechten oder gerad vor dir außgestreckt haltest, oder führest, welches außstrecken du wandlen magst, eintweders nach seinem herfechten oder nach deinen fürgenomenen stucken. | |

Near Guard and Middle Guard For these, arrange yourself like this: stand with the right foot forward and hold your staff with the middle part at your left hip, so that the shorter end and the butt point toward your opponent, but the longer end points behind you. Show your right side to him well, as you see in the lower picture in Figure A on the right hand side. The Middle Guard is the straight defence in front of the opponent, from which most fence. |

Nebenhut und Mittelhut. ZU deren schicke dich also, stand mit dem Rechten Fuß vor, halt dein Stangen mit dem mitleren theil auff deiner Lincken hüfft, also das das kurtzer ort und hinder ort gegen dem Man, das lenger aber hinder dir außstehe, beut ihm also die Recht seiten wol dar, wie dich solches das [Ⅲ.17v] under Bild in der Figur A. zur Rechten hand lehrt, die Mittelhut ist die gerade versatzung vor dem Mann, daraus man dann am meisten ficht. | |

Tiller Guard In this, arrange yourself like this: stand with the left foot forward and hold your staff with the fore end in front of your left foot on the ground, and the butt with outstretched arms in front of your face, all such as you can see in the second picture on the left hand side in the previous picture. You should also do the guard like this: stand with right foot forward and hold your staff behind you, also with the fore end on the ground, so you can strike deftly. |

Steürhut. IN dise schicke dich also, stand mit dem lincken Fuß vor, unnd halt dein Stangen mit dem vorderen ort für deinem lincken Fuß auff die erden, und den hindern ort mit außgestreckten Armen vor deinem gesicht ubersich, aller ding wie du solches an dem anderen Bild zur Lincken hand in obgedachter Figur sehen kanst, Auch soltu dise Hut also machen, stand mit dem Rechten Fuß vor, und halt dein Stangen hinder dir, auch mit dem vordern ort auff die erden, so bistu geschickt zum streich. | |

Of the binds and the defences of the staff; also its parts. The staff is divided into four parts, just as was taught previously of the other weapons. There are also four binds, and the first bind is performed at the fore end or outermost part of the staff; the second in front of the hand which is foremost on the staff; the third in the middle of the staff; the fourth will be performed with the butt end through the entering. You should especially be aware and take care of these parts and binds, because different techniques are appropriate to different parts, namely, in the first part and bind, the blow and flying thrust, in the second, staying in the winding and travelling after, and furthermore in the second entering and wrestling. |

Von dem anbinden und der Stangen versatzungen, auch ihrer theilung. DIe Stangen wirt auch in vier theil getheilt, gleichfals wie bißher von andern Wehren gelehrt, Derenhalben hastu auch vier anbind, und geschicht das erste anbinden am vordern oder eussern theil der Stangen, Das ander vor der hand, welche er in der Stangen vor führet, Das dritte in der mitte der Stangen, Das vierdte aber wirt durch das einlauffen mit dem hindern ort zu wegen gebracht, auff solche theilung und anbinde soltu sonderlich acht nehmen unnd haben, dann es sonst sorglich ist, wo man sich nicht befleißt in einem jeden theil des selbigen zugehörete stuck zu Fechten, als nemlich im ersten theil und anbind die schleg und fliegende stöß, im andern die bleiben Winden und nachreisen, und ferner in den andern die einlauffen und Ringen. | |

There are also four principle defences with the staff, like the binds: the first with the fore end of the staff from both sides, the second in front of the hand, the third in the middle, and the fourth is performed with the butt end. The while all such in techniques is enough to understand, is without ?? difficulties ??? to handle. |

[Ⅲ.18r] Der Versatzung aber in der Stangen seind fürnemlich auch wie der anbinden vier, deren dann die erste mit dem vorderen theil deiner Stangen von beiden seiten, Die ander vor der hand, Die dritte in der mitte, Und die vierte mit dem hindern ort volbracht wirt, Dieweil aber solche alle in stucken gnugsam zu verstehn, ist ohn von nöten von deren eim jeden in sonderheit zuhandeln. | |

Upper Guard In the approach put yourself in the Upper Guard, and notice as soon as he thrusts toward your left side, then step on your right side away from his thrust, and thrust in at him at the same time he thrusts at you, then wind the long edge against his staff; so he misses with his blow, and you connect with yours. |

Oberhut. Im zufechten schicke dich in die Oberhut, und nim wahr als bald er dir gegen deiner Lincken seiten zu sticht, so trit du auff dein Rechte seiten von seinem stoß aus, und Stich mit ihm zugleich hinein, im hinein stechen aber, so wende die Lange schneide gegen seiner Stangen, so felt er mit seinem stoß, und triffestu mit dem deinen. | |

However, if he thrusts toward your right, then step away from his thrust toward your left side, and thrust in with him again the same as before. |

Stoßt er dir aber gegen deiner Rechten, so trit aus seinem stoß gegen deiner Lincken seiten, und stoß abermal wie vor gleich mit ihm hinein. | |

The second piece from the Upper Guard Mark, in the approach place yourself in the Upper Guard. If he thrusts from above or below to the body, then step (when he thrusts to one side of you) away from his thrust to the other side, and strike while stepping out at the same time from above downward on his forward hand, and mark diligently, if he draws back the same, then thrust straight ahead toward his face. |

Das ander stuck auß der Oberhut. Merck, im zu fechten schicke dich in die Oberhut, Sticht er als dann auff dich her es sey unden oder oben zum leib, so trit ihm (wann er dir zu einer seiten hersticht) aus seinem stoß gegen der andern seiten, und schlag gleich in solchem austretten von oben nider auff sein vordere hand, und merck fleissig in dem er dieselbige zuckt, so stoß gerad vor dir hin gegen seinem gesicht. | |

Another, how you should strike him from above down through his staff, and tear out, and strike with one hand. In the approach place yourself in the Upper Guard to the left, that is, so that the fore end or longer part of your staff stands up over your left shoulder, and thus step toward him with your left foot forward; if he thrusts toward your face or chest, then spring well away from his thrust toward his right side, and strike down from above with your staff (which you should be holding fast in both hands) full through on the middle of his staff, so that through this blow you come into the Right Lower Guard; from this (where he would further thrust to your face) tear with the half edge up toward your left shoulder again. While you tear upward like this, give your staff a swing with your left hand, and in this swing let go of the staff with your left hand, and strike with one hand from your right over across toward his temple. The upper blow should quickly happen together with the tear, as soon and while this blow connects, then grip your staff with your left hand again, and bring it back into the straight defence. |

[Ⅲ.18v] Ein anders, wie du ihm von Oben nider durch seine Stangen schlagen, und wider ubersich außreissen, unnd mit einer hand nach schlagen solt. IM zufechten schicke dich in die Oberhut zur Lincken, das ist das dein Stangen mit dem vordern ort, oder langeren theil uber deiner Lincken Achsel auffstehe, trit also mit dem lincken Fuß vor zu ihm, stoßt er gegen deiner Brust oder deinem gesicht zu, so spring wol aus seinem stoß gegen seiner Rechten seiten, und schlag ihm mit deiner Stangen (die du dann zu beiden henden gefast behalten solt) von Oben nider, auff die mitte seiner Stangen gantz durch, also das du durch solchen schlag mit deiner Stangen in die rechte Underhut komest, von deren (wo er ferner deinem gesicht aber zu würde stechen) Reiß mit halber schneid wider ubersich gegen deiner Lincken Achsel, gleich mit in dem du also ubersich reissest, so gibe mit deiner lincken Hand deiner Stangen den schwung, in disem schwung laß die lincke Hand ab von deiner Stangen, unnd schlage mit einer hand von deiner Rechten uberzwerch gegen seinem schlaff, der oberschlag sampt dem Riß sollen behend auff einander geschehen, als bald und in dem diser schlag antrifft, so ergreiff mit deiner lincken Hand dein Stangen wider, und verzucke die in die gerade Versatzung. | |

Another. Mark, when you strike from above through his staff like this, and after you have torn up again from below, and your left hand together with the fore end of your staff has come upright again, then at once turn up your right hand together with the butt as well, and ? the same ?, lower the fore end with your left hand near your left out to the side, and turn the forward longer part of the staff again up toward his right. This must all happen in a ?. Thrust as then further with a step out straight toward his face, but be careful that you don't turn your right hand downward again to your chest in thrusting, but rather shift the same also well at your chest and inward at your left arm in thrusting ahead of you in to him. So, from the Upper Guard you have learned: firstly, how you should step out and thrust at the same time at him; secondly, striking at his staff down from above and thrusting afterward; thirdly, how you break down through against his staff from above, and tear up from below; lastly, how you should make a deceptive thrust. |

Ein anders. MErck wann du ihm also nun von Oben durch sein Stangen geschlagen, und dernach auch wider von Unden ubersich ausgerissen hast, und mit deiner lincken Hand sampt dem vor= [Ⅲ.19r] dern theil deiner Stangen wider ubersich komen bist, so wende als bald dein Rechte hand zu sampt dem hindern ort auch ubersich, unnd lasse dieselbige weil, dein vordern ort mit der lincken hand neben deiner Lincken zur seiten aus wider undersich sincken, unnd wende hiemit den vordern lengern theil deiner Stangen widerumb von unden ubersich gegen seiner Rechten, dises alles muß in einem huy geschehen, stoß als dann ferner mit einem austrit gerad gegen seinem gesicht, aber hab acht das du nicht allein im hinein stossen dein rechte Hand wider undersich zu deiner Brust wendest, sondern dieselbige auch wol an deiner Brust und inwendig an deinem lincken Arm im stossen für dir hin zu ihm hinein schiebest, Also hastu aus der Oberhut erstlich wie du austretten und mit im zugleich stossen solt, Zum anderen im sein Stangen von oben nider ausschlagen und nachstechen, Zum dritten wie du ihm gegen seiner Stangen von oben nider durchbrechen, unnd von unden ubersich ausreissen, auch wie du letstlich ein verführten stoß machen solt, gelehrt. | |

How you should thrust together with him from the Lower Guard. Mark, when you hold your right hand together with the butt of your staff at your right side in the approach, and you have lain your point well ahead of you out on your right side on the ground, observe as soon as he thrusts toward your face, then step step out with your right foot toward your right side, and with your left further toward his left to him; thrust in this way to his face above his left arm while he directs his thrust. You should also duck your head well down toward your right side over your staff while you thrust with him thus, away from his flying thrust, so you are the better defended. |

Wie du aus der Underhut mit ihm zugleich hinein stechen solt. MErck, wann du nun also im zufechten dein Rechte hand sampt dem hindern ort deiner stangen, an deiner Rechten weiche haltest, und dein vordern ort mit wol fürsich nach gehencktem leib, vor deiner Rechten zur seiten aus auff der erden ligen hast, so nim war als balt er gegen deinem gesicht hersticht, so trit mit deinem Rechten Fuß gegen deiner Rechten seiten auß, unnd mit deinem Lincken ferner gegen seiner Lincken zu ihm, stiche ihm also in dem er seinen stoß herführet, oberhalb seinem Lincken Arm zu seinem gesicht, auch soltu hiemit in dem du also mit ihm [Ⅲ.19v] hinein stossest, deinen Kopff wol von seinem herfliegenden stoß uber dein Stang gegen deiner Rechten seiten undersich sencken, so bistu desterbas versetzt. | |

Another, how you should strike out his thrust, and thrust afterward. In the approach place yourself again in the Lower Guard as before, with your forward knee bent, so that your upper body is well sunk to your staff, and mark as soon as he thrusts, then strike his staff from your right side toward your left in a jerk out, as far as the straight defence, and before he can recover himself from his thrust, thrust with a spring out toward his face. |

Ein anders, wie du ihm sein stoß außschlagen, unnd nach stossen solt. IM zufechten schicke dich abermals mit wol fürsich gebogenem Kni, also das dein oberer leib der Stangen wol nach gesenckt sey, in die Underhut wie vor, unnd merck als bald er her stoßt, so schlage ihm seine Stangen von deiner Rechten gegen deiner Lincken in einem ruck aus, doch also das du dich mit deiner Stangen in solchem ausschlagen nicht ferner verschlagest dann bis in die gerade Versatzung, unnd ehe dann er sich von solchem stos wider erholt und ermant, so stos ihm mit einem aussprung gegen seinem gesicht. | |

Another. Mark, when you fallen into the Left Lower Guard in the approach, and he strikes with one hand from above toward your head, then raise both your arms, and with this spring in well under his stroke, thus parrying his blow with your staff between your hands. As soon as and while the blow lands on your staff, and is still touching, draw the butt toward you with your right hand, letting the point drop downward, direct the same between his hands under his staff to his body, and thus thrust below his staff between his hands in front of his chest. While you are thrusting in like this, turn the butt of your staff together with your right hand down again, and could drive in inside your right arm. After the thrust is performed you should be nimble with the bind again on his staff; therewith you may the better protect yourself from what he does afterward. |

Ein anders. MErck wann du dich im zufechten in die Lincke Underhut verfallen hast, und er schlecht dir mit einer hand von Oben herein gegen deinem Kopff, so fahre mit beiden Armen ubersich auff, mit solchem aufffahren spring ihm wol under seinen streich hinein, versetze ihm also seinen schlag zwischen dein beide hend auff dein Stangen, als bald unnd in dem der schlag auff dein Stangen bocht, und noch im zusamen rühren ist, so zuck mit deiner Rechten hand den hindern ort zu dir, auch lasse hiemit den vorderen ort undersich sincken, führe im dasselbige zwischen seinen beiden henden under seiner Stangen zum leib, und stosse ihm also underhalb seiner Stan= [Ⅲ.20r] gen zwischen seinen beiden henden, für sein Brust, in dem du aber also hinein stossest, so wende deinen hinderen ort zu sampt deiner Rechten hand wider undersich, gegen deiner Brust, auff das du mit derselbige den stoß hart an deiner Brust, und inwendig an deinem Rechten arm hinein führen könnest, nach volbrachtem stoß soltu behend mit dem band wider an seiner Stangen sein, damit du dich dester baß vor seinem nachfechten schützen mögest. | |

How you should yield to his thrust from the Left Lower Guard, and thrust together with him. In the approach, step with your left foot forward, hold the butt of your staff together with your right hand at your right flank, and let the point of your staff lie outstretched in front of you on the ground, a little out to the left side, and mark as soon as your opponent thrusts at you, then step with your right foot behind your left out to the side, a little toward his right side, and as you set down your right foot in stepping behind, step quickly with your left foot also toward his right side further toward him, and thrust over his right arm (while he thrusts) to his face. |

Wie du ihm aus der Lincken Underhut auß seinem stoß weichen, und mit ihm zugleich hinein stossen solt. IM zufechten trit mit deinem Lincken Fuß vor, halt dein hindern ort sampt der Rechten hand in der Rechten weiche, unnd lasse den vordern ort deiner Stangen gegen deiner Lincken ein wenig zur seiten aus, vor dir ausgestreckt auff der erden ligen, unnd merck aldo als bald dein gegenfechter auff dich her stoßt, so trit mit deinem Rechten fus hinder deinem Lincken zur seiten aus, ein wenig gegen seiner Rechten seiten, und in dem du deinen Rechten fus im hinder tretten noch also nider setzest, so trit eilents mit deinem Lincken fus auch gegen seiner Rechten seiten fürter zu im, und stoß ihm oberhalb seinem Rechten arm (in dem er her stoßt) gegen seinem gesicht. | |

How you should strike out his thrust from your Left Lower Guard and thrust afterward. Or when you stand in the said way in the Right Lower Guard, then step again as before, while he thrusts, toward his right side away from his thrust, and strike off his staff together with him from your left toward your right, and afterward thrust nimbly again as before (before he can recover) to his face. |

Wie du ihm seinen stoß von deiner Lincken underhut ausschlagen und nach stechen solt. ODer wann du auff gemelte weiß in der Rechten Underhut stehest, so trit abermals wie vor, in dem er her sticht gegen seiner Rechten seiten aus seinem stoß, und schlag ihm gleich mit sei= [Ⅲ.20v] ne Stangen von deiner Lincken gegen deiner Rechten ab, demnach stosse ihm behend abermals wie vor (ehe dann er sich wider erholt) gegen seinem gesicht. | |

How you should take out from your left upward with the long edge, and thrust again through the Roses from your right side up from below to his face.

|

Wie du mit Langer schneide von deiner Lincken ubersich außnemen, und durch die Rosen wider von deiner Rechten unden auff gegen seinem gesicht stechen solt. IM zufechten schicke dich in die Underhut zur Lincken wie vor, stost er dann auff dich her, so fahre mit beiden Armen auff, und schlage im seinen stoß mit dem vordern theil deiner Stangen von deiner Lincken ubersich, gegen deiner Rechten mit Lnager schneide aus, also das du in solchem ausschlagen mit deiner Stangen gantz ubersich durch kommest, wende demnach dein Stangen wider neben deiner Rechten von unden auff, unnd stich von derselbigen wider ubersich gegen seinem gesicht. | |

How you should jerk his staff out and thrust afterward.

|

Wie du ihm sein Stangen außrucken und nach stechen solt. MErck wann du im zufechten in der Underhuten eine kommest, unnd er nicht arbeiten noch stossen will, so laß dich mit geberden mercken und ansehen, als woltestu dich aller erst umb sehen was dir für stuck zu Fechten seyen, als bald und in dem er aber sein Stangen also von ihm ausstreckt, so rucke ihm die in einem uhnversehenen ruck oder schlag aus, unnd stoß ihm behend (all dieweil er nach mit seiner Stangen vom genomnen stoß daumelt) gegen seinem gesicht, in [Ⅲ.21r] disem ausschlagen soltu fleissig wahr nemen, das du dich (wie nechst auch angeregt) nicht mit deiner Stangen dem ausschlagen nach zu weit auff die seiten verfahrest, sonder schlage ihm die seine (wie gelehrt) in einem ruck aus, auff das du mit deiner Stangen behend wider gerad vor seinem gesicht seyest, und also den stoß volbringest ehe dann er sich wider ermant. | |

How you should fence from the Middle Guard. In the approach place yourself in the Middle Guard, such as is shown in the large picture printed in Figure A on the right hand side, and take care as soon as you can reach him, throw your staff with your right hand overthwart across his face, and in the throw give your staff a strong swing with your left hand, and loose the same from the staff, so that your staff can the swifter fly across his face and around your head; while your staff is thus flying through his face and around your head, step to him with your left foot forward, and grip under your staff again with your left hand, while your staff is still flying through the air, and strike to the other from your left to your right through the face; also against his staff through where he drives before him, this blow should be performed with both hands, so that you end in the Right Lower Guard after the blow. While your staff thus in this blow falls into the Lower Guard, if he would nimbly thrust at your face (which would be left open by this movement), then step with your right foot quickly on your right side, and thrust in with him at the same time also to his face, so that you have turned the rear part of your staff together with the long edge against his, and pulled your head well away over your staff, so you are defended. |

Wie du auß der Mittelhut fechten solt. Im zufechten schicke dich in die Mittelhut, auff solche weiß wie das grosser Bild in hievor getruckter Figur A. zur Rechten hand anzeigt, unnd nim wahr als bald du ihn erlangen kanst, so wirff ihm dein Stangen mit deiner Rechten hand uberzwerch durch sein gesicht, zu solchem wurff gibe deiner Stangen mit deiner Lincken hand ein starcken schwung, unnd laß dieselbige hiemit von der Stangen ab, auff das deine Stangen in disem wurff dester geschwinder durch sein gesicht und umb dein Kopff fliegen könne, in dem aber, das dein Stang also durch sein gesicht und umb dein Kopff fleugt, so trit auch mit deinem Lincken Fuß fürt zu ihm, unnd greyff under des, dieweil dein Stangen im herumb fliegen noch in der lufft ist, mit deiner Lincken hand wider an dein Stangen, und schlage ihm zum andern von deiner Lincken gegen seiner Rechten durch das gesicht, auch gegen seiner Stangen durch wo er die vor ihm führet, diser schlag soll mit beyden henden verricht werden, also das du nach endt des schlags in die Rechte Underhut kommest, dieweil dein Stangen aber also in disem schlag in die Underhut verfallet, wirt er dir behendiglichen gegen deinem gesicht (welches dann mit solchem verfallen enblöst wirt) herstossen, deren halben so trit mit deinem Rechten Fuß eilents auff dein Rechte seiten, unnd stoß mit im zugleich auch gegen seinem gesicht hinein, doch das du im hinein stossen die Lange schnei= [Ⅲ.21v] de sampt dem hindern theil der Stangen gegen der seinen gewendet, unnd deinen Kopff wol aus seinem stoß uber dein Stangen entzuckt habest, so bistu versetz. | |

Or after you have fallen into the Right Lower Guard after this blow, and he has thrust at the opening offered, then tear out his flying staff upward with the half edge toward your left shoulder; at the same time drive your staff above around your head, and strike him outside over his left arm from your right; you should also drive this blow around with both hands; herein beware that he (while you thus drive your blow around) will thrust to the face; as soon as he does so, move the butt of your staff around lower before your face, and let the blow fly the faster. If he parries your blow with hanging staff, then mark the moment your staff lands on his or misses, then at once turn the butt end upward, and thrust above or below his staff to the body. |

Oder nach dem du also durch disen schlag in die Rechte Underhut verfallen bist, und er deiner gegebenen Blösse zu stost, so Reisse mit halber schneide ihme sein herfliegende Stangen ubersich, gegen deiner Lincken Achsel aus, zugleich mit solchem Ausreissen führe dein Stangen oben umb dein Kopff, und schlage ihm von deiner Rechten aussen uber seinem Lincken Arm, disen schlag soltu auch mit beiden henden herumb führen, hie zwischen hab acht ob er dir (dieweil du disen schlag also herumb führest) zum gesicht stossen wölle, so bald er dann solches thut, so führe den hinderen ort im herumb fahren dester niderer vor deinem gesicht herumb, unnd lasse den schlag dester geschwinder fliegen, Versetzt er dir aber den schlag mit hangender Stangen, so merck in dem dein Stang auff die seine bocht oder felt, so bald wend auch den hindern ort ubersich, und stoß ihm ober oder underhalb seiner Stangen zum leib. | |

Another, how you should invert before him, or give over, take out, and strike after. In the approach place yourself in the said manner in the Middle Guard to the left side, and step with the left foot behind your right toward him, so that in the movement you turn your back to him. While you thus turn in front of him, he will quickly thrust to your face, meaning to overtake you; then in your backward stepping lift both your hands nimbly upward together with the butt of your staff, outstretched toward his left side, so that the point hangs toward the ground, and as you turn strike his oncoming thrust with your hanging staff from your right out toward your left side, and let the same move through a full swing around your head. While it thus moves through the swing, let go with your left hand (after you have given the staff a strong swing with the same) and strike with one hand a strong swift stroke to his left ear. This is a swift piece which goes well in the first attack; if you provoke his thrust with your turn, then you take his staff out in the time of the turn, and surely hit him, if he has thrust in earnest. |

Ein anders, wie du dich vor ihm verkehren, oder ubergeben, ausnemen und nachschlagen solt. IM zufechten schicke dich auff obgemelte form, in die Mittelhut zur Lincken seiten, unnd trit also bald mit deinem Lincken Fuß hinder deinem Rechten zu im, also das du in solchem umbwenden, ihme den Rucken zu wendest, in dem du dich aber also vor ihm umbwendest, wirt er dir eilents gegen deinem gesicht herstechen, in meinung das zu ereylen, derenhalben so erhebe in solchem hindersich treten dein beide hend zu sampt dem hinderen theil deiner Stangen, also das das vorder theil derselbigen gegen der erden hanget, behendiglich ubersich ausgestreckt gegen [Ⅲ.22v] seiner Lincken, und schlag ihm in solchem deinem umbwenden, seinen herkommenden stoß mit deiner hangenden Stangen von deiner Rechten gegen deiner Lincken zur seiten aus, und laß die selbige durch ein schwung vollend umb den Kopff fahren, in dem du aber also mit deiner Stangen herumb fahrest, so laß die Lincke hand (nach dem du mit derselbigen deiner Stange einen sterckern schwung gegeben hast) ab, und schlag mit einer hand einen starcken geschwinden streich zu seinem Lincken ohr, Dises ist ein geschwind stuck, welches im ersten angriff wol angeht, dann mit deinem umbwenden reitzestu ihn zu stossen, stost er dann, so nimstu ihm gleich in solchem umbwenden sein Stangen aus, und triffst ihn gewiß, so er ernstlichen gestossen hat. | |

The techniques learned up to now from the side lyings, I wanted to first set down, since you were to arrive in the same through striking aback, thrusting away, or fending off, so the more smoothly you know how to recover again, also the better you know how to do the techniques that follow; the same with these long weapons as with the weapons previously handled; in full fencing always from one into another, in which you need not first long consider what you are to do, but rather press on with the next technique. |

Dise bißher gelehrte stuck aus den seiten Legern, hab ich darumb erstlich setzen wöllen, damit wann du durch Verschlagen, Verstossen oder Versetzen in derselben eines ankomen werest, dich dester füglicher wissest wider zu ermanen, auch dich in folgende stuck dester baß wissest zu richten, dann in disen langen Wehren komstu gleichfals wie auch in bißher verrichten Wehren, in vollem Fechten immer aus einem in das ander, in welchen du dich demnach nicht lang erst bedencken must was dir zu thun sey, sonder mit den nechst fürfalleten stucken fürtringen. | |

Now in the straight defence as I have named it here, position yourself in the approach as shown by the pair in the previous figure. |

Nun in die gerade Versatzung aber, wie ich sie hie genent hab, schicke dich im zufechten also, wie dich die zwen bossen in hievor getruckter Figur fürbilden und lehren. | |

The first technique in the outermost bind. When you bind with the outermost part of your staff on the outermost part of his, then press the same in a sudden strong jerk out to the side, such that yours does not move after the pressing out, but rather thrust nimbly off from his staff ahead to his face, and that quickly before he has recovered himself from the pressing out. |

Das erste stuck im eussersten anbinden. SO du ihm mit deinem eussersten theil deiner Stangen an das eusserste der seinen anbindest, so truck ihm dieselbige in einem uhnversehenen starcken ruck zur seiten aus, soch also das du mit der deinen dem austrucken nach nicht verfahrest, sonder stoß im behendiglichen, von seiner Stangen ab, für dir hin zu seinem gesicht, und das eilents ehe dann er sich vom austrucken erholt hat. | |

Another, how you should move through and thrust on the other side after the jerking out. When you become aware in the pressing out that he is coming on nimbly with his staff, so that you cannot overtake him with the thrust you were taught, then do this: Jerk his staff again on one side as before, and let yourself seem as if you want to thrust as before, but as soon as and while he speeds his staff again toward yours, meaning to parry your thrust, then meanwhile go through under his staff, and with a spring out thrust to his face with great speed and force. This is a swift passage, when you thus unexpectedly jerk someone's staff out, and nimbly go through under, and thrust in on the other side. |

[Ⅲ.23r] Ein anders, wie du nach dem außrucken durchfahren und auff der andern seiten stossen solt. SO du aber in solchem ausrucken gewahr wirst, das er mit seiner Stangen so behend wider ankompt, also das du ihn mit gelehrtem stoß nit ereylen kanst, so thu ihm also, Ruck im seine Stangen abermal auff ein seiten wie vor auch, und laß dich mercken als woltestu wie vor stossen, aber als bald und in dem er mit seiner Stangen wider her zu gegen deiner eylet, in meinung deinen stoß zuversetzen, so fahr du dieweil er noch herwischt, under derselbigen seiner Stangen durch, und stoß ihm auff der andern seiten mit einem aussprung eilents unnd gewaltig zum gesicht, Dises ist ein geschwinder durchgang, wann du einem also sein Stang ohnversehens außruckest, demnach behend unden durch fahrest, und auff der andern seiten hinein stost. | |

Another, how you should press out his staff and strike to his forward leg. In the approach bind from your left hand side, with the outermost part of your staff on the outermost of his, and press his out with a sudden jerk toward his left side, and draw your staff nimbly back again, toward your left around your head. Let go of the staff with your left hand, and strike with one hand strongly from your right overthwart, with a wide step of your right foot through his feet; grip your staff again with your left hand while the same is thus moving through in the stroke, and then strike the other with both hands through to his right shoulder, so that you end in the Right Lower Guard; from this thrust to his face after the manner described above. |

Ein anders, wie du ihm die Stangen außrucken, und zu seinem fürgesetzten bein schlagen solt. IM zufechten bind ihm von deiner Lincken hand, mit deinem eussersten theil an das eusserste seiner Stangen, und truck ihm die in einem unversehenen ruck gegen seiner Lincken hand auß, unnd zucke dein Stangen behend wider zu ruck, gegen deiner Lincken umb deinen Kopff, laß hiemit dein Lincke hand von der Stangen ab, unnd schlage mit einer Hand von deiner Rechten starck uberzwerch, mit einem weiten zutrit deines Rechten fusses durch sein füß, ergreiffe demnach dein Stangen dieweil dieselbige im streich noch also durch fahrt, wider mit deiner Lincken hand, und schlage als dann den andern mit beiden henden, von deiner Lincken schlims [Ⅲ.23v] gegen seiner Rechten achsel durch, also das du nach ende des schlags in die rechte Underhut kommest, von deren stoß ihm nach obgeschriebener form zu seinem gesicht. | |

Or when you thus strike through overthwart to his forward leg, then look that you grip your staff again on your left side with your left hand; as soon as you have gripped it, draw the butt back to your right at your chest, and move the left well along the staff with outstretched arm; while you draw your hands apart thus on the staff, turn the staff toward his, and strike out the same (while he thrusts), so that you strongly and forcefully come again into the straight defence with left arm stretched far out, and then thrust nimbly straight ahead to his face. |

Oder wann du also zu seinem fürgesetzten bein uberzwerch durchschlechst, so schauw das du dein Stangen im durchschlagen wider auff deiner Lincken seiten mit deiner Lincken hand ergreiffest, als bald du die ergriffen hast, so zuck dein hindern ort zu deiner Rechten an dein Brust, und mit der Lincken fahr wol mit ausgestrecktem Arm in die Stangen hinein, in dem du aber dein hend also in der Stangen von einander zeuchst, so wende dein Stangen gegen seiner, und schlag im dieselbige (in dem er her stöst) auch auß, also das du dein Stangen gewaltig und starck mit außgespanenem Lincken Arm wider in die gerade Versatzung bekommest, und stoß als dann behendiglich gerad für dir hin zü seinem gesicht nach. | |

A piece, how you should make the Brain Blow. Do it like this: in the approach bind the tip of your staff with the tip of his; let yourself seem as if you are earnestly looking where or how you want to thrust to his face. As soon as he notices, he will diligently take care on your leaving the bind, that he could nimbly thrust while you leave. When you place yourself earnestly, like you want to thrust, then quickly jerk the butt of your staff upward, and swing the staff back with your left hand toward your left around your head, and thus unexpectedly strike straight from above to his head, and if he would yet thrust under this, then the same does not serve, for then you are too swift with the blow to his head. This and the like pieces have the more part in the Practice, namely that you outrace your opponent with unexpected speed, when he makes the slightest mistake. |

Ein stuck wie du den Hirnschlag machen solt. DEn treib also, im zufechten binde im mit deinem eussersten theil deiner Stangen in sein eusserste an, aldo laß dich mit geberden mercken als sehest du dich ernstlich umb, wo oder wie du ihm gegen seinem gesicht stechen wöllest, als bald er das mercken wirt, so wirt er fleissig war nemen auff dein abgohn, auff das er dir behend in dem du abgehest nach stossen könne, Derhalben wann du dich am aller ernstlichen stellest, sam du alben zu stechen wollest, so ruck dein hindern ort eilents ubersich, und mit der Lincken hand aber schwing die Stangen zu ruck, gegen deiner Lincken umb den Kopff, unnd schlag ihm also mit einer hand ohnversehens gerad von oben zu seinem Kopff, unnd ob er under dessen schon herstechen wirde, so geht ihm derselbige doch nicht an, dann du bist ihm zu geschwind mit dem schlag auff seinem Kopff, Dise und derglei= [Ⅲ.24r] chen stuck stand den mehren theil in der Practick, nemlich da du dein wider fechter mit ohnversehener behende ubereylest, wann er sich dessen am wenigsten versicht. | |

Another, with the skewed stroke. Mark, when you have bound your opponent as taught above, then surreptitiously invert your right hand on your staff, and deceive him meanwhile by appearance, so that he doesn't notice what you are doing, and when he makes the slightest mistake, then step toward him quickly with the right foot, and strike a swift and powerful stroke over the hand, straight from above to his head, so that your upper body is sunk well down after the blow, then nimbly move your staff up again, and at the same time step back again with the right foot, and grab your staff with your left hand again, so that you can strongly defend yourself again. You can move to this skewed stroke as you do the aforesaid brain blow, namely when you first jerk out his staff, or else when you can hinder him with some other technique, so that you can hit him with the skewed stroke before he can come up again. |

Ein anders mit dem schöfferstreich. MErck wann du deinem gegenmann wie bißher gelehrt, angebunden hast, so verkehre dein Rechte hand heimlich an deiner Stangen, unnd verführe ihn dieweil mit geberden, auff das er dein fürnemen nicht mercke, als dann wan er sich des am wenigsten versicht, so trit mit dem Rechten Fuß eilents zu im, und schlag hiemit uber die hand einen gewaltigen und geschwinden streich, gerad von Oben zu seinem Kopff, also das du mit deinem obern leib dem schlag nach wol undersich gesenckt standest, fahre als dann behendiglich mit deiner Stangen wider auff, unnd trit zugleych auch mit deinem Rechten Fuß wider zu ruck, auch greyff underdes mit deiner Lincken hand wider an dein Stangen, damit du dich wider mit versatzung stercken mögest, Zu dem vorgehenden Hirnschlag, Zu disem Schöfferstreich kanstu dir auch raumen, nemlich wann du ihm die Stangen erstlich ausruckest, oder ihn sonst mit andern stucken hinderst, auff das du ihn mit dem Schöfferschlag ereylest ehe dann er wider auffkompt. | |

How you should strike around from his staff and shoot over. Further, when you can reach the tip of his staff with the tip of yours, and he is hard on your staff, the be aware as soon as he wants to press you out to the side with force, then draw back your staff nimbly (while he is pressing out) around your head with both hands, and strike outside over his left arm to his head with a step out. As soon as this blow connects, quickly shift your staff over his near his hands, as you can see shown hereafter in Figure G; when you have thus found and barred his staff, then you may go in and thrust with the butt of your staff, or strike in front of his face with the longer part; if he moves his point up, and works it out under your staff, then follow after from below with thrusting, winding, or pressing. |

Wie du von seiner Stangen umbschlagen und uberschiessen solt. WEyter wann du im zufechten sein eusserste theil der Stangen mit deinem eussersten erlangen kanst, und er ist dir hart an deiner Stangen, so hab acht als bald er dir mit gewalt zur seiten austrucken wil, so zuck dein Stangen behendiglich (in dem er dir solche außtruckt) umb [Ⅲ.25r] deinen Kopff mit beiden henden, und schlag in mit solcher aussen uber seinen Lincken Arm, mit einem außtrit zum Kopff, als bald diser schlag antrifft, so schiebe dein Stangen eilents uber die seine nach bey seinen henden, wie du solches in der Figur G. hernach gezeichnet sehen kanst, wann du ihm also sein Stangen gefast und gespert hast, so magstu ihm also dann mit dem hindern ort eingehn und stossen, oder mit dem langen theil für sein gesicht schlagen, fehrt er aber mit dem ort auff, und arbeit sich under deiner Stangen herfür, so folge im von unden nach, es sey mit stossen Winden oder trucken. | |

How you should go through him. Mark, if your opponent is hard on your staff in the bind, and presses away from him, then go under through, and thrust on the other side. Or while he thus presses out your staff with his hard bind, again go hard on his staff (while he is still pressing) through under, and jerk him out with a ? blow from the other side, and thrust nimbly before he has recovered. |

Wie du ihm durchgehn solt. MErck ist dein gegen fechter mit seinem band hart ahn deiner Stangen, und truckt von im, so fahr unden durch, und stoß auff der andern seiten, Oder in dem er dir also dein Stangen austruckt mit seinem harten anbinden, so fahr abermal hart an seiner Stangen (dieweil er noch also truckt) unden durch, und Ruck ihm die mit einem neydlichen schlag von der andern seiten auß, und stoß behendiglich nach, ehe dann er sich ermant hat. | |

Another. If someone binds hard on your staff, then hold hard against him with your bind; if he also presses against yours, then quickly go through below, and act as if you want to thrust, but don't; rather draw through below again, and thrust to the side which you were originally bound on. |

Ein anders. Bindet dir einer hart an dein Stangen, so halt ihm mit deinem band hart wider, truckt er auch gegen der deinen, so fahr eilents unden durch, und thu sam du stossen woltest, thus aber nicht sonder zuck wider unden durch, unnd stoß ihm zu der seiten gegen welche du ihm erstlich angebunden hast. | |

How you should learn missing in the bind. Mark diligently, when you have bound with someone from your left side, then diligently observe and feel just as soon as he leaves the bind, to go through below or to work otherwise, then thrust while he is thus leaving, straight ahead to his face. |

[Ⅲ.25v] Wie du in den Banden fehlen leren solt. Das mercke fleissig wann du einem von deiner Lincken seiten angebunden hast, so nim fleissig wahr und fühle eben, als bald er von deinem Band abgeht, es sey unden durch oder sonst zu arbeiten, so stosse ihm dieweil er noch also abgeht, gerad für dir hin gegen seinem gesicht. | |

Another is a counter to the former. When you become aware in the bind, that your opponent is watching for your leaving, and wants to thrust to the opening while you are leaving, then let yourself seem by your appearance as if you earnestly want to move away from his staff and thrust, and when you think that he is ready to thrust, then move off his staff to the side, as if you wanted to thrust as said, but don't; rather, while he rushes in with his thrust, strike it up out to the side, and thrust in as first ?, then when he rushes in, you can easily take his staff out, and overtake him well before he can recover himself again. |

Ein anders ist der bruch auff das vorige. WAnn du im Band gewahr wirst, das dir dein gegen Fechter auff dein abgehn acht nimpt, und dir dieweil du abgehest zur Blöß stossen will, so laß dich mit geberden mercken als wollestu ernstlich von seiner Stangen abgehn und stossen, und wann du vermeinest das er sich am aller besten zum nachstossen geschickt hab, so gehe mit deiner Stangen gehlingen auff die seite aus, ab, von der seinen, sam du wie gesagt stossen wöllest, thus aber nicht, sonder in dem er mit seinem stoß hereylet, so schlag ihm den auff die seiten aus, und stoß als dann erst vervollen hinein, dann wann er so gehlingen hereylet, kanstu ihm sein Stangen leychtlichen ausnemen, und ihn wol ereylen ehe er sich wider erholet. | |

Thus you should mark and be aware of what your opponent wants to fence and drive to you, so that you catch him just in his own technique, as next herefore at this one then inclined true soon after to thrust [???]. Then you must expose yourself cautiously and warily to the same, and place yourself in such a way with the appearance, as resist befalling the approximate and ignorant [???], or you have wasted your ? thrust after with reluctance, so that through this he will be all the more incited to thrust, with which thrust or blow he fails and exposes himself, as close that he so agile hardly against comes up and may recover himself [???], before then you have overtaken him. This will be expanded on further on by example in the halberd. |

Also soltu auff mercken und wahrnemen, was dein gegen Fechter auff dich Fechten und treiben wölle, das du ihn eben in seinen eigenen stucken fangest, als nechst hievor an disem der dann geneygt wahre bald nach zustechen, Derenhalben mustu dich vor demselben fürsichtlich unnd gewahrsam blössen, unnd zu solchem blössen dich mit geberden also stellen, als wehre dir das ungefehr unnd unwissen widerfahren, oder habest dich deinem begirigen stoß nach mit unwillen verfallen, auff das er hiedurch dester ehr unnd begirlicher zu stossen angereitzt werde, mit welchem stossen oder schlagen er sich selber vergibt unnd blöst, als fast das er so behendt [Ⅲ.26r] schwerlich wider auff komen und sich erholen mag, ehe dann du ihn ereylet habest, Dises aber wirt in der Helleparten noch weiter durch Exempel ausgeführt werden. | |

A deceptive piece. When you have bound with someone in the approach, and neither of you will leave the other's staff, then thrust to his leading foot with a serious appearance, exposing your face, to which he will nimbly thrust, then step out to the side with your lead foot, followed by the right, and thrust under his staff from below (while the same flies in the thrust) to his face, and pull your head well away from his thrust behind your staff, so you hit him (while he is thrusting) in the face. Or when you thrust or strike to his foot, and meanwhile he thrusts to your face, then strike out his flying thrust, and at the same time spring out to the side away from his thrust, and thrust quickly and nimbly. |

Ein verfüher stuck. IM zufechten wann du mit einem angebunden hast, und keiner wil von des andern Stangen abgehn, so stich im mit ernsthafften geberden zu seinem fürgesetzten fuß, damit blössestu dein gesicht, zu welchem er behendiglich her stossen wirt, als bald, und in dem er dann herstost, so trit du mit dem vordern Fuß zur seiten aus, folge mit dem Rechten, und stoß ihm von unden uberhalb seiner Stangen (in dem dieselbige zum stoß herfleugt) gegen seinem gesicht, und entzucke ihm auch hiemit deinen Kopff wol von seinem stoß hinder dein Stangen, so triffestu ihn (dieweil er noch hersticht) in sein gesicht, Oder wann du ihm zu seinem Fuß stöst oder schlechst, und er dieweil deinem gesicht zu stost, so schlage ihm sein herfliegenden stoß aus, und springe zugleich in solchem ausschlagen zur seiten aus seinem stoß, und stoß behend und eilents nach. | |

How you should thrust with one hand out over his left arm to his face, wind through with the butt end of your staff, and strike to the right shoulder. If you have bound someone ahead from your left against his right, but he stays still and does not work, then step with your rear right foot to your right side, and go with your point hard on his staff through below, and thrust nimbly and unexpectedly from your right over his left arm to his face. In thrusting, let go of your staff with your left hand, and give the right side the thrust, so that you reach in the further. In this thrust turn up your right hand together with the butt of your staff toward your left side, and draw your staff around your head, and in this drawing around spring in nimbly on your left side. Strike thus wickedly to his right shoulder. This blow together with the thrust should be done nimbly one after another and together. Then spring back, so that you may be sure to catch and grip your staff again. |

[Ⅲ.26r] Wie du mit einer hand aussen uber seinen Lincken arm zu seinem gesicht stossen, mit dem hindern ort durchwinden, und zur Rechten achsel schlagen solt. HAstu einem vornen von deiner Lincken gegen seiner Rechten angebunden, er aber ligt still und arbeit nicht, so trit mit deinem hindersten Rechten fuß auff dein Rechte seiten, und gehe hiemit auch mit deinem vordern ort hart an seiner Stangen unden durch, unnd stoß ihm behents und ohnversehens von deiner Rechten uber seinem Lincken arm zu seinem gesicht, im hin= [Ⅲ.26v] ein stossen aber, so laß die Lincke hand von der Stangen, und gib die Rechte seiten dem stoß wol nach, auff das du von uberzwerch dester weiter hinein langest, in solchem stossen wende die rechte hand mit sampt dem hindern theil der Stangen ubersich gegen deiner Lincken, und zuck dein Stangen hiemit umb dein Kopff, auch spring in disem umbzucken behends auff dein Lincke seiten, schlage ihm also schlims gegen seiner Rechten achsel, Diser schlag zu sampt dem stoß sollen behends auff einander und zusamen getrieben werden, spring als dann zu ruck, auff das du dein Stangen wider sicher mit deiner Lincken hand aufffangen und ergreiffen mögest. | |

Another, how you should wind through with the thrust. Do it like this: if you find yourself in the straight defence in the approach, then thrust straight from your right to his left hand, that he has placed forward on his staff; but in the beginning, let yourself seem by your appearance as if you wanted to thrust to his face. When you come near his hand with your point, go through below his staff and step with your left foot well out to his right side, and take your head well aside with you, and turn your point thus in thrusting through outside over his right arm to the face - turn your open right hand well upward, inside your left arm, so the thrust goes the deeper. |

Ein anders, wie du mit dem stoß durchwinden solt. DEm thu also, im zufechten so du ihn in gerader versatzung findest, so stoß ihm gericht von deiner Rechten gegen seiner Lincken hand, die er dann in der Stangen vor führet, im anfang aber, so laß dich doch mit geberden mercken als woltestu ihm in sein angesicht stossen, wann du nun mit deinem vordern ort nahet an sein hand komest, so fahre under seiner Stangen durch und trit hiemit auch mit deinem Lincken Fus wol gegen seiner Rechten seiten aus, in solchem aus tretten nim dein Kopff wol mit, und wende also deinen vordern ort im durchstossen aussen uber seinem Rechten Arm zum gesicht, im hinein stechen aber, wende dein Rechte offene hand wol ubersich, an deinem inwendigen Lincken arm hinein, so gehet der stoß desto dieffer. | |

A swift and artful thrust against one who does not work, but rather lies strongly in the defence.

|

Ein künstlichen und geschwinden stoß gegen dem der nicht arbeiten, sonder starck in der versatzung ligt zu brauchen. MErck wann du im zufechten deinen gegenpart in gerader Versatzung findest, so schicke dich auch also, und laß dich mit geberden mercken, als woltestu dich aller erst umbsehen was dir [Ⅲ.27r] zu fechten sey, under des aber, wann er sich dessen am wenigsten versihet, so trit mit deinem rechten Fuß eilents gegen seiner Lincken seiten aus, und stosse ihm oberhalb seiner Lincken hand (die er dann in der Stangen vor führet) gerichts seiner Brust zu, doch also das du sein Stangen mit der deinen nit rührest, in disem stoß führe dein Rechte hand wol gegen deinem Lincken arm, und auff demselbigen hinein, zu dem so wende hiemit dein Lincke offene hand ubersich umb, so geht der stoß dester dieffer, und triffst eben auff solche weiß an, wie dir solches an dem Bilde zur Lincken hand in der Figur E. fürgestelt. | |

Another: how you thrust upward through his face.

|

Ein anders, wie du mit einem stoß ubersich durch sein gesicht stossen. TRinget dein gegenfechter im band auff dich, so bleibe mit deiner Stangen auch hart an der seinen, als bald ihr beide so nahet komen seind, also das die Stangen im anfang des anderen theils zusamen rühren, so bleibe under des mit dem band hart an seiner Stangen, und stosse den hindern ort mit deiner Rechten hand von dir, also das dein vorderer ort auff seiner Stangen gegen seiner Rechten achsel aussehe, zu dem so trit auch mit deinem Rechten Fuß wol auß gegen seiner Lincken seiten, und stosse ihm mit deiner Stangen (doch das du mit deren hart auff der seinen bleibest) gegen seiner Rechten achsel, im hinein stossen aber, wende dein Rechte hand mit dem hindern ort wider zu dir, gegen deiner Brust umb, also das deine Finger an deiner brust und die offene hand oben stehe, wann du also, dieweil du mit deiner Stangen hart auff der seinen bleibest, gegen seiner Rechten achsel stossest, und im hin stossen dein hindern ort wider zu dir wendest, so gehet dein stoß ubersich, und triffst ihn in sein gesicht, er muß aber sehr behendt und mit sterck ins werck gericht und volführet werden. | |

At the same time as you make this thrust, lift your staff with both hands, and strike nimbly from above down to his face, and in this blow spring further toward his left side with your right foot. |

[Ⅲ.27v] Zugleich mit disem stoß führe dein Stangen mit beiden henden ubersich, und schlage behend von oben nider gegen seinem gesicht wider nider, in solchem schlag aber, spring mit deinem rechten Fuß noch ferner gegen seiner Lincken seiten umb. | |