|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Salvator Fabris"

| (107 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

| patron = {{plainlist | | patron = {{plainlist | ||

| Christianus Ⅳ of Denmark | | Christianus Ⅳ of Denmark | ||

| − | | Johan Frederik of Schleswig-<br/> | + | | Johan Frederik of Schleswig-Holstein-<br/>Gottorp |

}} | }} | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

| below = | | below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Salvator Fabris''' (Salvador Fabbri, Salvator Fabriz, Fabrice; 1544-1618) was a 16th – [[century::17th century]] [[nationality::Italian]] knight and [[fencing master]]. He was born in or around Padua, Italy in 1544, and although little is known about his early years, he seems to have studied fencing from a young age and possibly attended the prestigious University of Padua.{{cn}} The French master [[Henry de Sainct Didier]] recounts a meeting with an Italian fencer named "Fabrice" during the course of preparing his treatise (completed in 1573) in which they debated fencing theory, potentially placing Fabris in France in the early 1570s | + | '''Salvator Fabris''' (Salvador Fabbri, Salvator Fabriz, Fabrice; 1544-1618) was a 16th – [[century::17th century]] [[nationality::Italian]] knight and [[fencing master]]. He was born in or around Padua, Italy in 1544, and although little is known about his early years, he seems to have studied fencing from a young age and possibly attended the prestigious University of Padua.{{cn}} The French master [[Henry de Sainct Didier]] recounts a meeting with an Italian fencer named "Fabrice" during the course of preparing his treatise (completed in 1573) in which they debated fencing theory, potentially placing Fabris in France in the early 1570s<ref>[[Henry de Sainct Didier|Didier, Henry de Sainct]]. ''[[Les secrets du premier livre sur l'espée seule (Henry de Sainct Didier)|Les secrets du premier livre sur l'espée seule]]''. Paris, 1573. pp 5-8.</ref>, although that piece of evidence is [https://blog.subcaelo.net/ensis/sainct-didier-fabris/ particularly slim]. In the 1580s, Fabris corresponded with Christian Barnekow, a Danish nobleman with ties to the royal court as well as an alumnus of the university.<ref name="Leoni">[[Salvator Fabris|Fabris, Salvator]] and Leoni, Tom. ''Art of Dueling: Salvator Fabris' Rapier Fencing Treatise of 1606''. Highland Village, TX: [[Chivalry Bookshelf]], 2005. pp XVIII-XIX.</ref> It seems likely that Fabris traveled a great deal during the 1570s and 80s, spending time in France, Germany, Spain, and possibly other regions before returning to teach at his alma mater.{{cn}} |

It is unclear if Fabris himself was of noble birth, but at some point he seems to have earned a knighthood. In fact, he is described in his treatise as ''Supremus Eques'' ("Supreme Knight") of the Order of the Seven Hearts. In Johann Joachim Hynitzsch's introduction to the 1676 edition, he identifies Fabris as a Colonel of the Order.<ref>[[Salvator Fabris|Fabris, Salvator]] and Leoni, Tom. ''Art of Dueling: Salvator Fabris' Rapier Fencing Treatise of 1606''. Highland Village, TX: [[Chivalry Bookshelf]], 2005. p XXIX.</ref> It seems therefore that he was not only a knight of the Order of the Seven Hearts, but rose to a high rank and perhaps even overall leadership. | It is unclear if Fabris himself was of noble birth, but at some point he seems to have earned a knighthood. In fact, he is described in his treatise as ''Supremus Eques'' ("Supreme Knight") of the Order of the Seven Hearts. In Johann Joachim Hynitzsch's introduction to the 1676 edition, he identifies Fabris as a Colonel of the Order.<ref>[[Salvator Fabris|Fabris, Salvator]] and Leoni, Tom. ''Art of Dueling: Salvator Fabris' Rapier Fencing Treatise of 1606''. Highland Village, TX: [[Chivalry Bookshelf]], 2005. p XXIX.</ref> It seems therefore that he was not only a knight of the Order of the Seven Hearts, but rose to a high rank and perhaps even overall leadership. | ||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

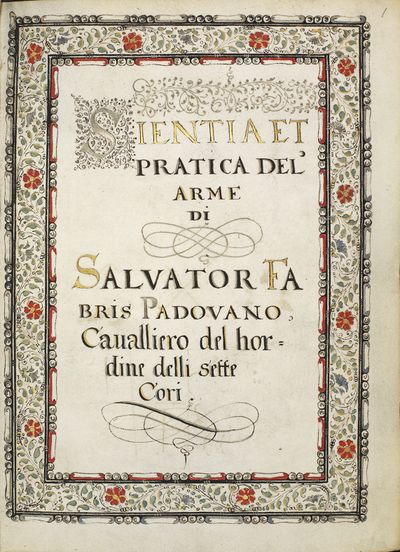

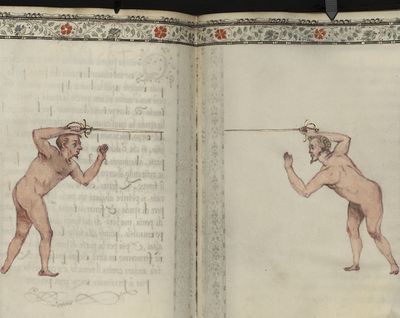

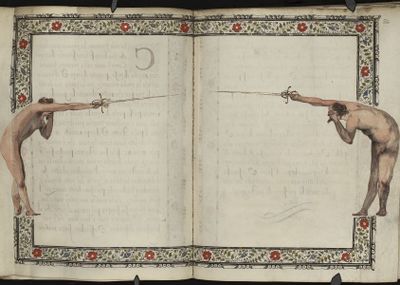

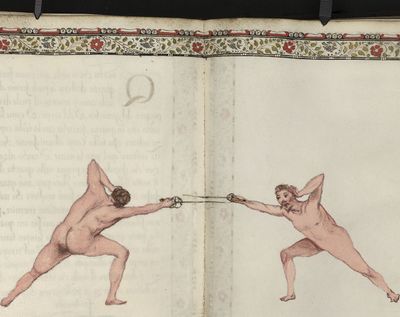

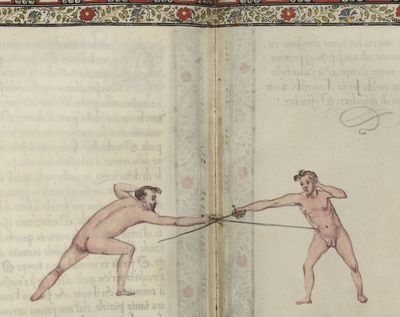

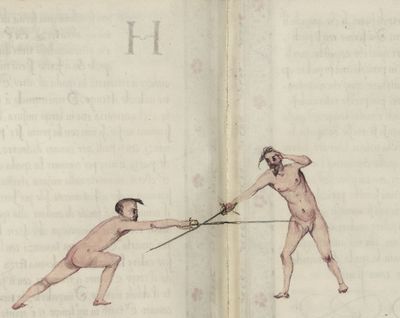

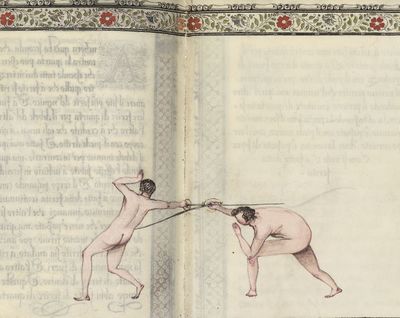

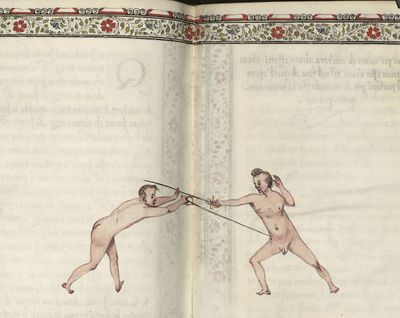

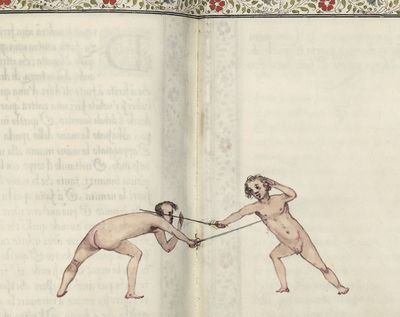

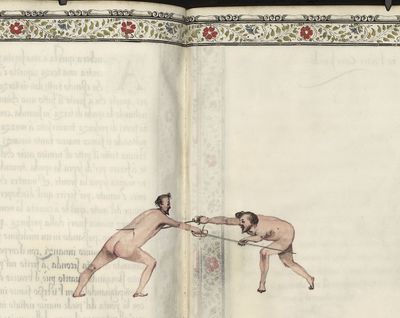

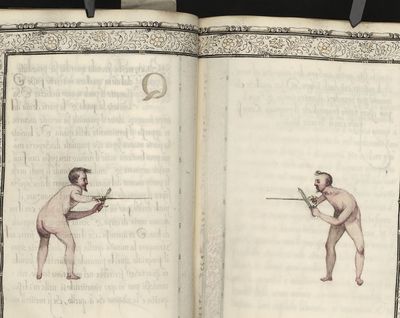

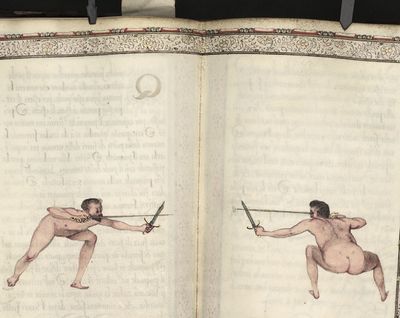

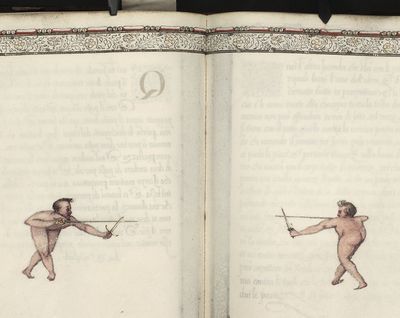

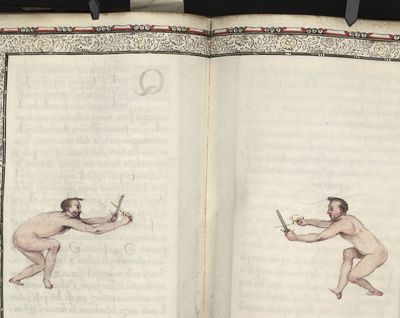

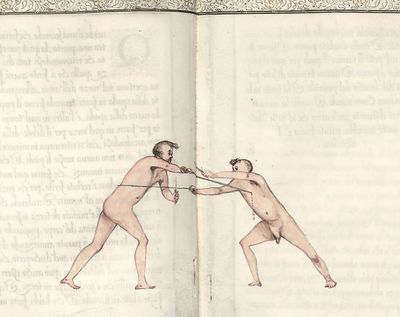

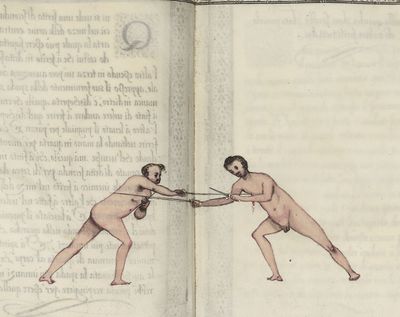

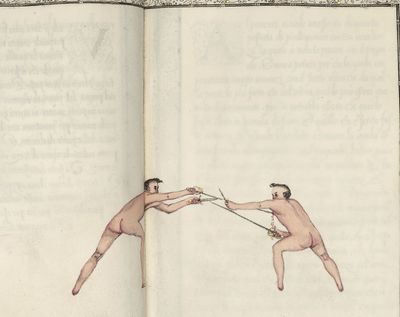

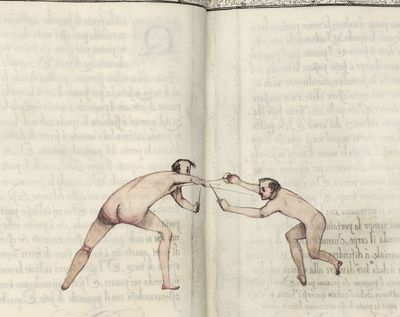

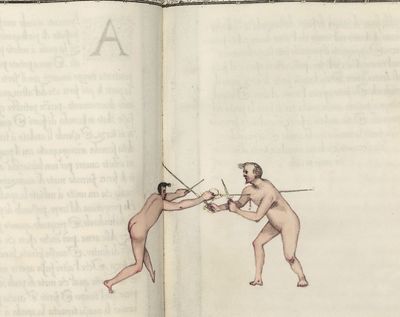

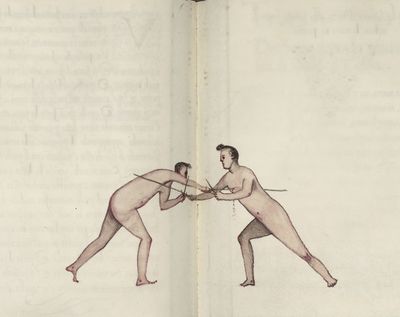

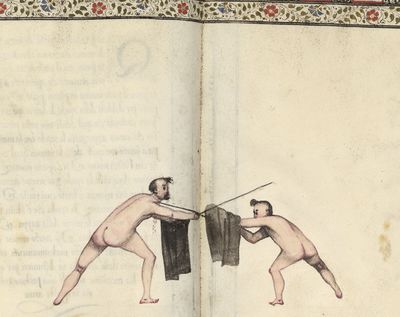

What is certain is that by 1598, Fabris had left his position at the University of Padua and was attached to the court of Johan Frederik, the young duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp. He continued in the duke's service until 1601, and as a parting gift prepared a lavishly-illustrated, three-volume manuscript of his treatise entitled ''Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme'' ([[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|GI.kgl.Saml.1868 4040]]).<ref name="Leoni"/> | What is certain is that by 1598, Fabris had left his position at the University of Padua and was attached to the court of Johan Frederik, the young duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp. He continued in the duke's service until 1601, and as a parting gift prepared a lavishly-illustrated, three-volume manuscript of his treatise entitled ''Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme'' ([[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|GI.kgl.Saml.1868 4040]]).<ref name="Leoni"/> | ||

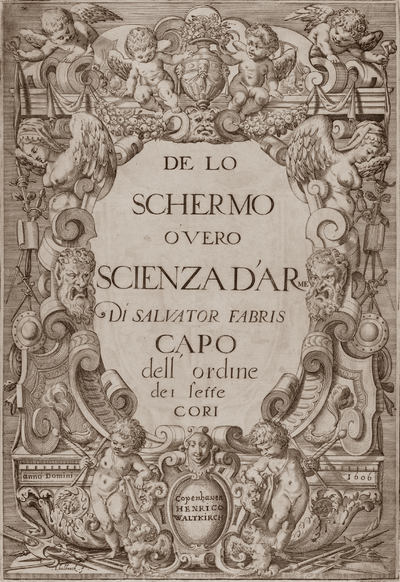

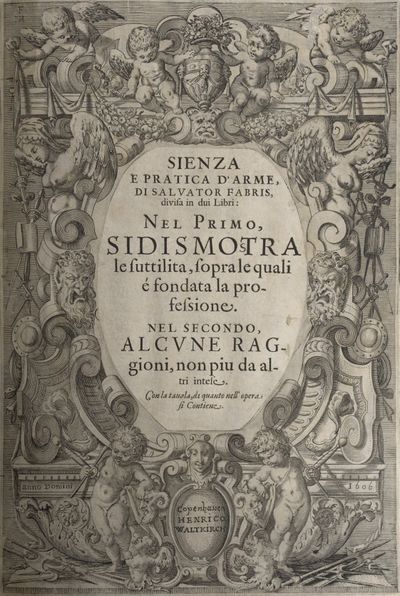

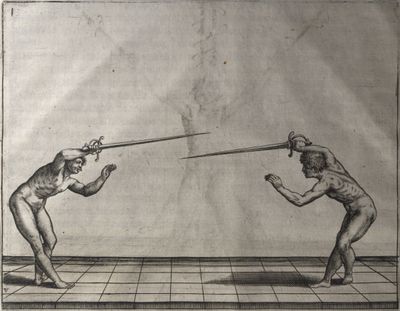

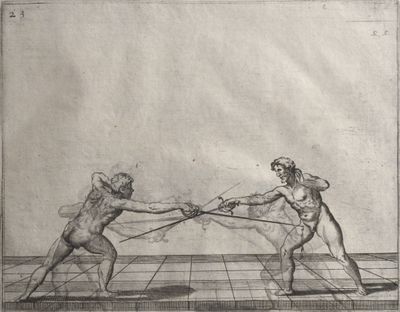

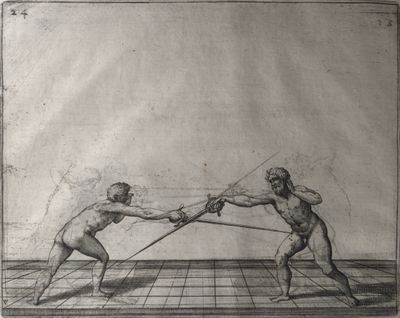

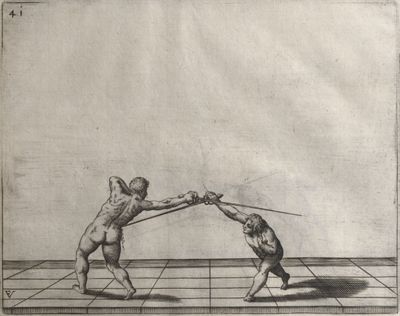

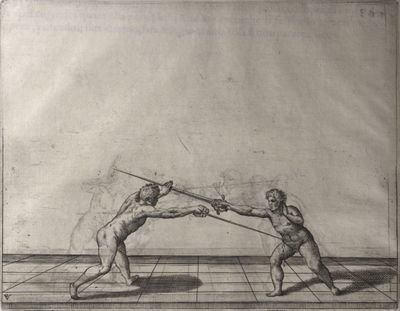

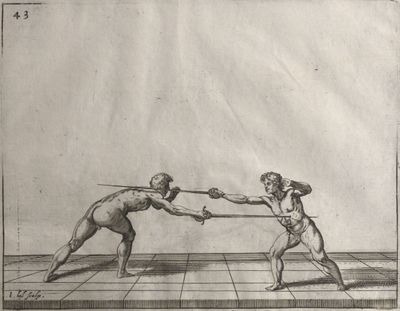

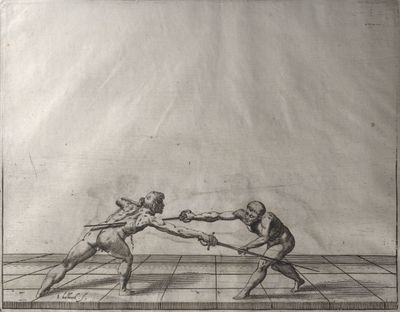

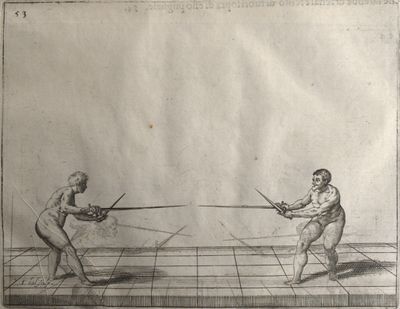

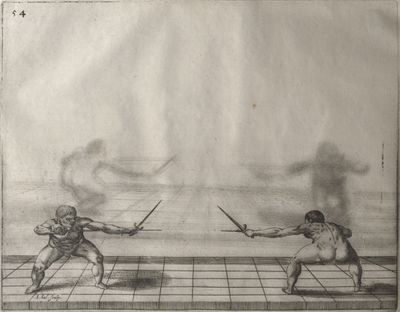

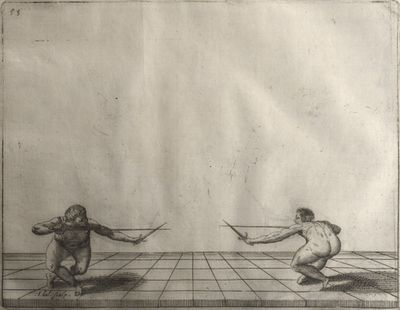

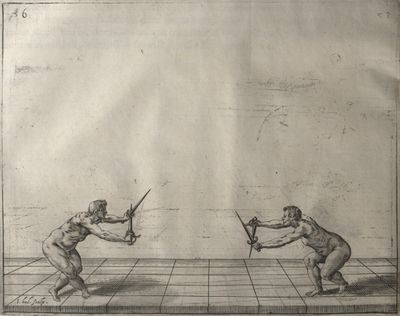

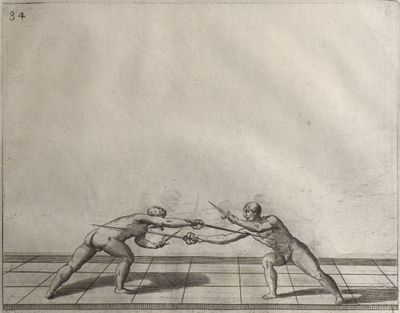

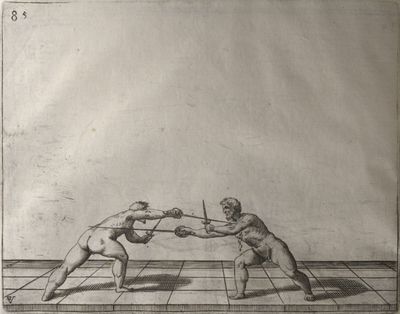

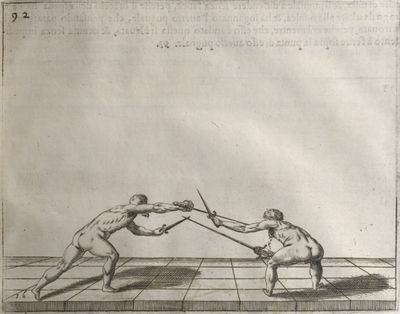

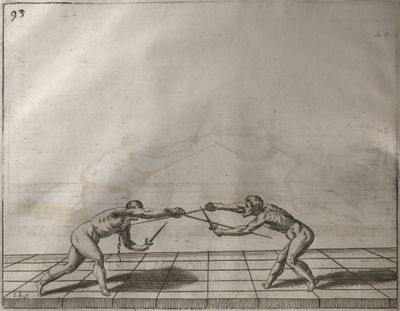

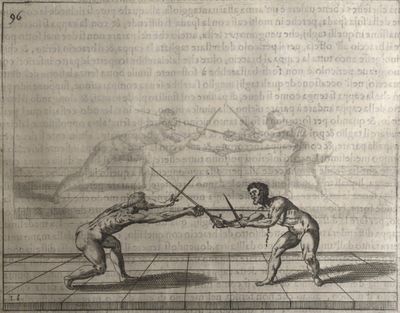

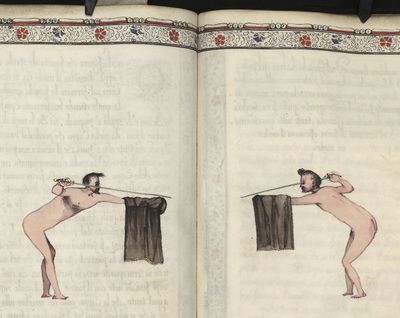

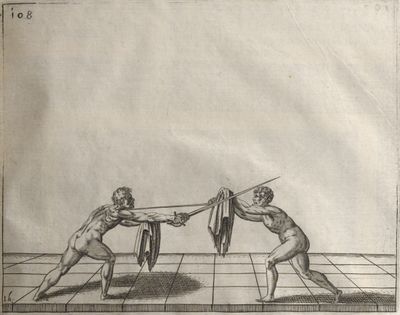

| − | In 1601, Fabris was hired as chief [[rapier]] instructor to the court of Christianus Ⅳ, King of Denmark and Duke Johan Frederik's cousin. He ultimately served in the royal court for five years; toward the end of his tenure and at the king's insistence, he published his opus under the title '' | + | In 1601, Fabris was hired as chief [[rapier]] instructor to the court of Christianus Ⅳ, King of Denmark and Duke Johan Frederik's cousin. He ultimately served in the royal court for five years; toward the end of his tenure and at the king's insistence, he published his opus under the title ''De lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme'' ("On Defense, or the Science of Arms") or ''Sienza e Pratica d’Arme'' ("Science and Practice of Arms"). Christianus funded this first edition and placed his court artist, [[Jan van Halbeeck]], at Fabris' disposal to illustrate it; it was ultimately published in Copenhagen on 25 September 1606.<ref name="Leoni"/> |

Soon after the text was published, and perhaps feeling his 62 years, Fabris asked to be released from his six-year contract with the king so that he might return home. He traveled through northern Germany and was in Paris, France, in 1608. Ultimately, he received a position at the University of Padua and there passed his final years. He died of a fever on 11 November 1618 at the age of 74, and the town of Padua declared an official day of mourning in his honor. In 1676, the town of Padua erected a statue of the master in the Chiesa del Santo. | Soon after the text was published, and perhaps feeling his 62 years, Fabris asked to be released from his six-year contract with the king so that he might return home. He traveled through northern Germany and was in Paris, France, in 1608. Ultimately, he received a position at the University of Padua and there passed his final years. He died of a fever on 11 November 1618 at the age of 74, and the town of Padua declared an official day of mourning in his honor. In 1676, the town of Padua erected a statue of the master in the Chiesa del Santo. | ||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

! class="double" | <p>[[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|Prototype]] (1601)<br/></p> | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|Prototype]] (1601)<br/></p> | ||

! class="double" | <p>[[Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Archetype]] (1606){{edit index|Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Archetype]] (1606){{edit index|Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ||

| − | ! class="double" | <p>German Translation (1677){{edit index|Sienza e pratica | + | ! class="double" | <p>German Translation (1677){{edit index|Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

| [[File:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) Title 1.png|400px|center]] | | [[File:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) Title 1.png|400px|center]] | ||

| <p>[1] '''Fencing''', or '''the Science of Arms''' by Salvator Fabris.</p> | | <p>[1] '''Fencing''', or '''the Science of Arms''' by Salvator Fabris.</p> | ||

| − | | | + | | {{paget|Page:GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040|1r|jpg}} |

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf| | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|3|lbl=I}} |

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Sienza e pratica | + | | {{pagetb|Page:Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf|6|lbl=I}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 104: | Line 104: | ||

| <p>[2] </p> | | <p>[2] </p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf| | + | | |

| + | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|1|lbl=*|p=1}}<ref>This second title page is an interesting anomaly. It was not printed as part of the main book the way the other title page was, and is instead printed on a single sheet that was glued into the binding. Of 24 copies surveyed by Michael Chidester, 14 had only the first title page, 3 had only the second title page, 16 had both title pages, and 1 had neither (instead, a second copy of page 151 was glued into the beginning of the book to serve as a title page). It's unclear what these anomalies indicate about the process of printing the book.</ref> | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 118: | Line 119: | ||

| | | | ||

| [[File:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) Heraldry.jpg|400px|center]] | | [[File:Scienza d’Arme (Fabris) Heraldry.jpg|400px|center]] | ||

| − | | <p>[4] To His Serene Majesty, the most Powerful Christian IV., King of Denmark, Norway, Gothland and Vandalia, Duke of Schleswig Holstein, Stormarn and Ditmarsch, Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst, &c. | + | | <p>[4] To His Serene Majesty, the most Powerful Christian IV., King of Denmark, Norway, Gothland and Vandalia, Duke of Schleswig Holstein, Stormarn and Ditmarsch, Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst, &c.</p> |

| − | <p>I am confident that all who read this work of mine will recognise that the many benefits received from your Serene Highness are the cause, which has urged and impelled me to publish to the world these my labours. I have wished also to help professors of the science of arms by showing them those instructions and rules, which after long use and continual practice and from observing the errors of others I have found to be good. I hope then that a work based on such principles will find merit, especially as it is under the protection of your Serene Highness - a work as worthy by reason of the excellence of its subject as it is glorious through the approval of your high judgment. To you, therefore, my benefactor, my king and a prince of incomparable valour as much in civil government as in the practice of arms, a true hero of our times, I have dared to dedicate my work; for since its inception is due to you, I am bringing it forth to the sight of men under the same protection. I know moreover how useful to the world and necessary to good men this art is, bringing honour to anyone who practises it aright either in the defence of his prince, his country, the laws, his life or his honour. Will your Serene Majesty therefore deign to receive into your favour not only the work, but the devotion with which, your humble and obedient servant, dedicate it. Meantime I will pray the Divine grace that long life may be granted you for the well-being of your blessed subjects and the good of the world, and that by grace you may obtain salvation in the world to come. | + | <p>I am confident that all who read this work of mine will recognise that the many benefits received from your Serene Highness are the cause, which has urged and impelled me to publish to the world these my labours. I have wished also to help professors of the science of arms by showing them those instructions and rules, which after long use and continual practice and from observing the errors of others I have found to be good. I hope then that a work based on such principles will find merit, especially as it is under the protection of your Serene Highness - a work as worthy by reason of the excellence of its subject as it is glorious through the approval of your high judgment. To you, therefore, my benefactor, my king and a prince of incomparable valour as much in civil government as in the practice of arms, a true hero of our times, I have dared to dedicate my work; for since its inception is due to you, I am bringing it forth to the sight of men under the same protection. I know moreover how useful to the world and necessary to good men this art is, bringing honour to anyone who practises it aright either in the defence of his prince, his country, the laws, his life or his honour. Will your Serene Majesty therefore deign to receive into your favour not only the work, but the devotion with which, your humble and obedient servant, dedicate it. Meantime I will pray the Divine grace that long life may be granted you for the well-being of your blessed subjects and the good of the world, and that by grace you may obtain salvation in the world to come.</p> |

<p>Your Serene Majesty's</p> | <p>Your Serene Majesty's</p> | ||

| Line 159: | Line 160: | ||

! class="double" | <p>[[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|Prototype]] (1601)<br/></p> | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868.4040)|Prototype]] (1601)<br/></p> | ||

! class="double" | <p>[[Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Archetype]] (1606){{edit index|Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ! class="double" | <p>[[Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris)|Archetype]] (1606){{edit index|Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Michael Chidester]]</p> | ||

| − | ! class="double" | <p>German Translation (1677){{edit index|Sienza e pratica | + | ! class="double" | <p>German Translation (1677){{edit index|Sienza e pratica d'arme (Johann Joachim Hynitzsch) 1677.pdf}}<br/>Transcribed by [[Alex Kiermayer]]</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 196: | Line 197: | ||

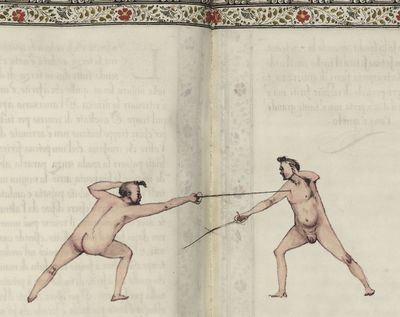

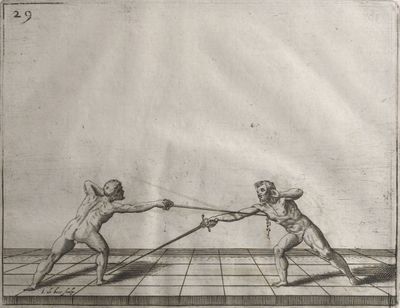

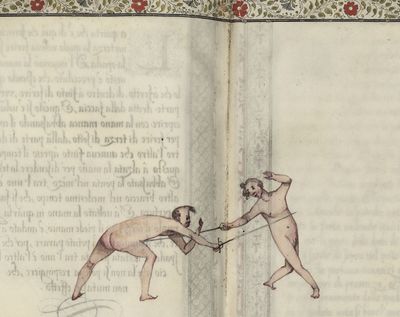

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

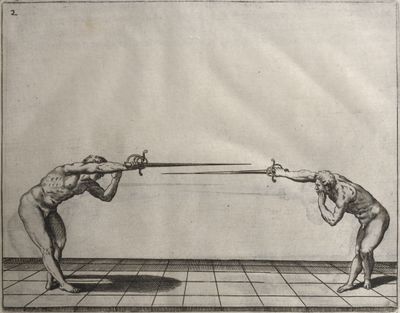

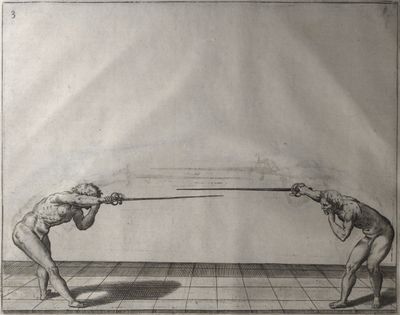

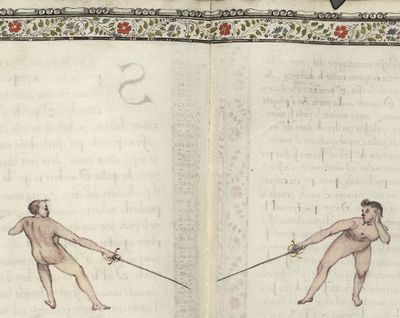

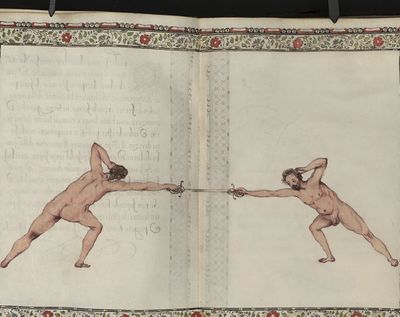

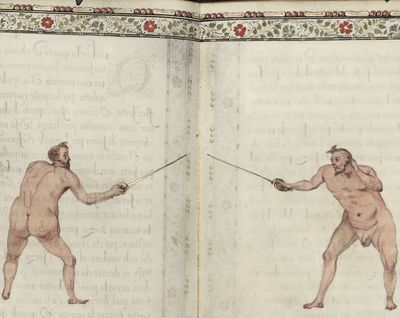

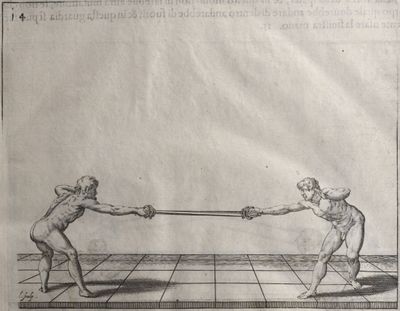

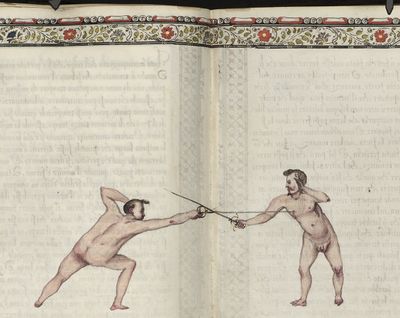

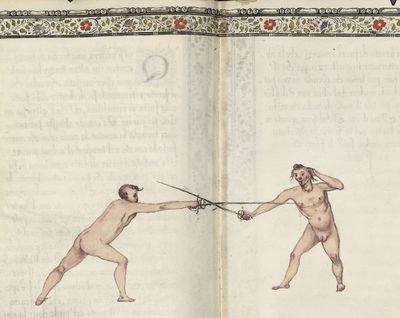

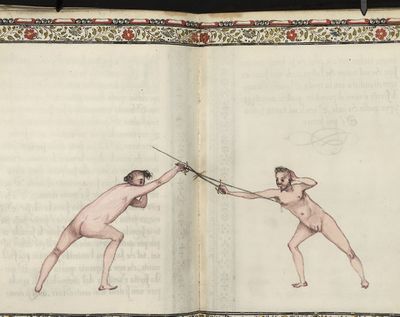

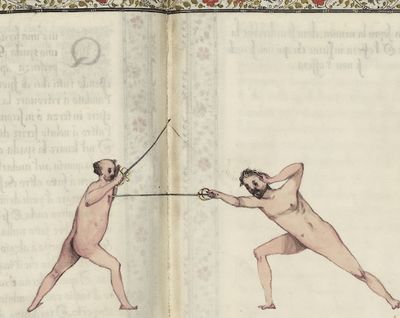

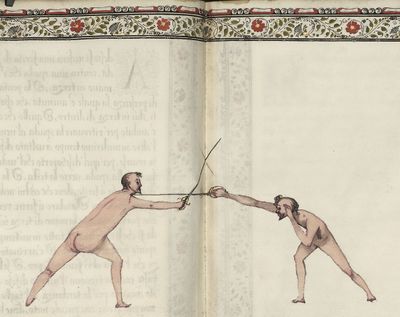

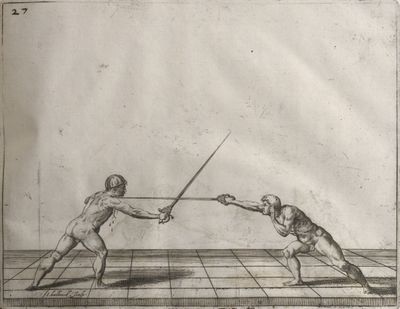

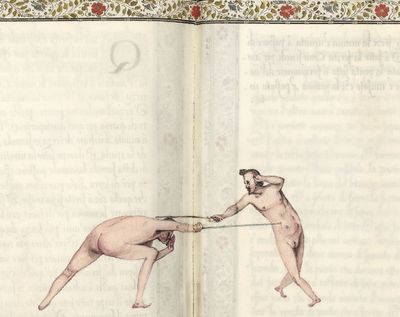

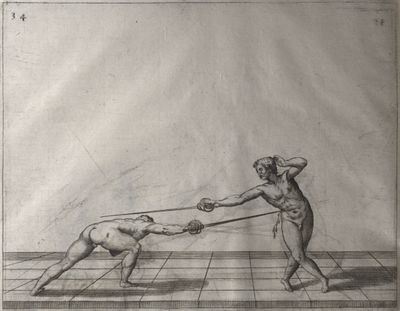

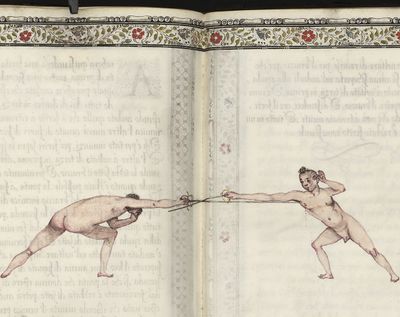

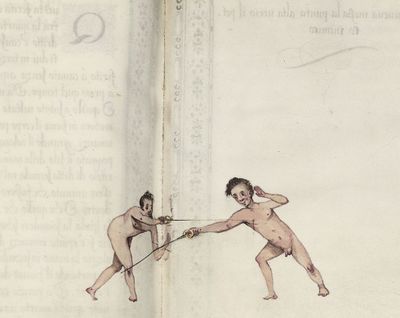

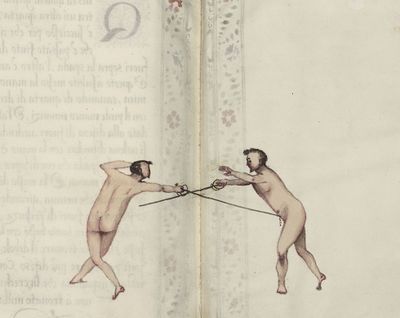

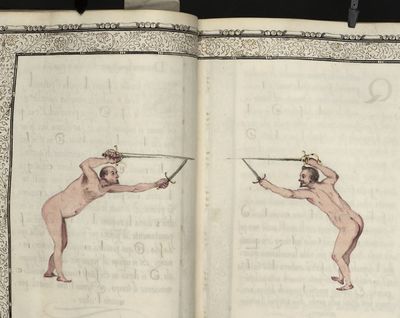

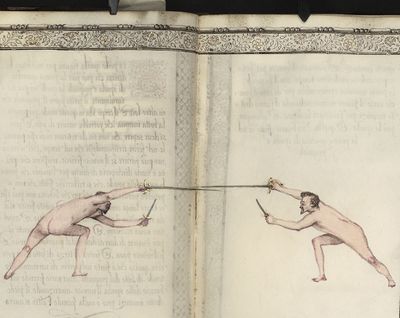

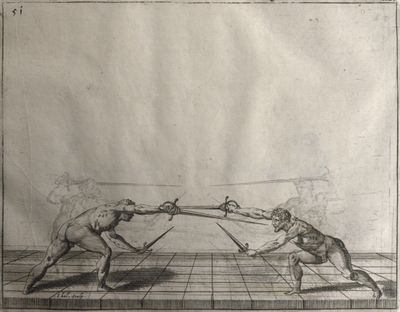

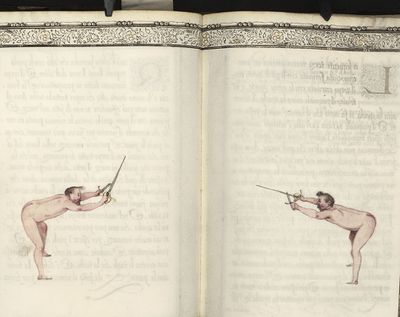

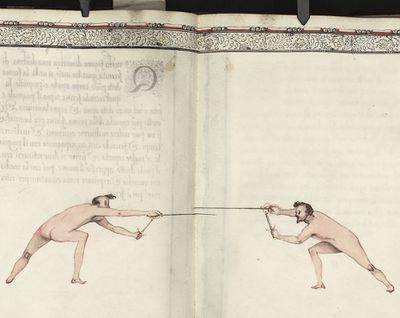

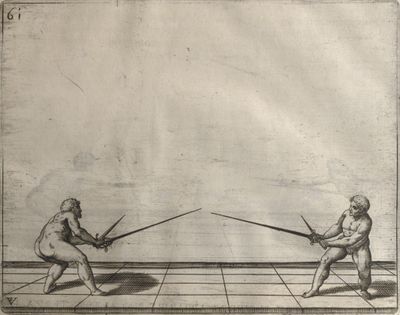

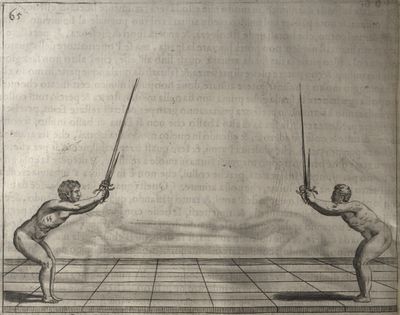

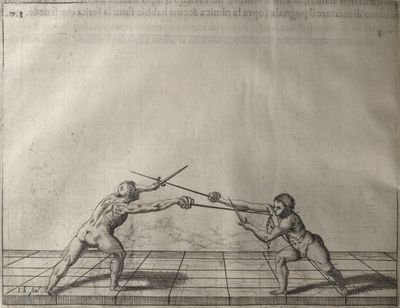

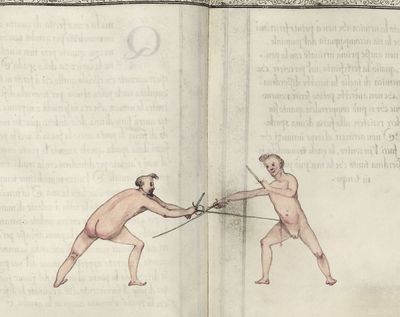

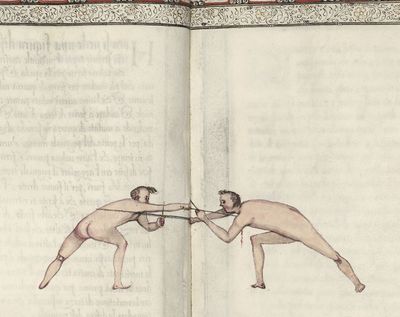

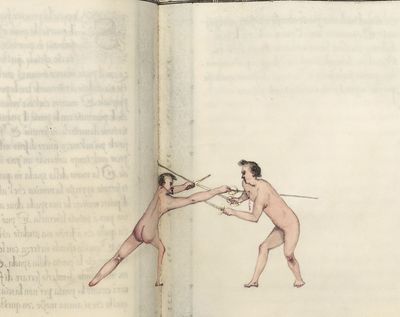

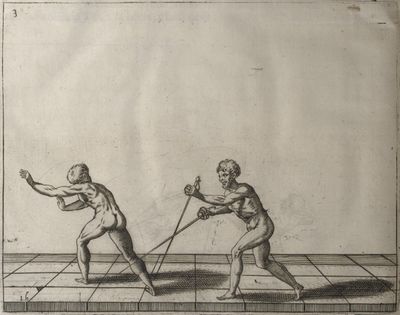

| − | | <p>[4] '''Method of forming the counter-positions,''' showing '''The position of the arms and the body, and when they are to be formed.'''</p> | + | | <p>[4] '''Method of forming the counter-positions,''' showing '''The position of the arms and the body, and when they are to be formed.'''<br/><br/></p> |

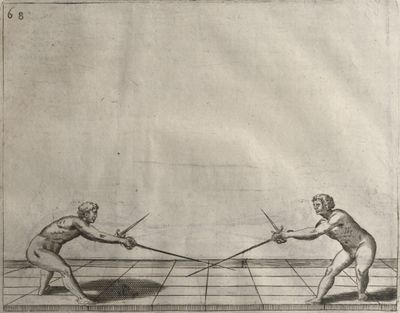

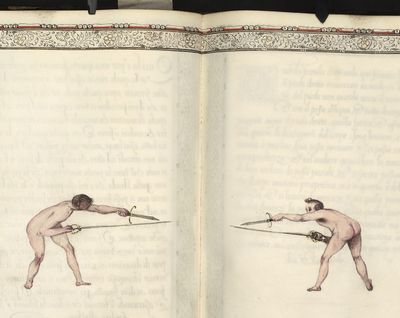

<p>If you wish to form a sound counter-position, the position of the body and arms must be such that without touching the adversary's sword you are defended in the straight line from the point of his sword to your body, so that without making any movement of the body or the sword you are sure that your adversary cannot hit you in that line, but that if he wishes to attack he must move his sword elsewhere, with the result that his ''time'' is so long, that there is every opportunity to parry. But in forming this position care must be taken that your sword is held in such a way as to be stronger than your adversary's, so that it may offer resistance in defence. This rule can be observed against all positions and changes of your adversary, whether accompanied by the dagger or any other defensive weapon, or when you use the sword alone. He who can most subtly maintain this guard will have a great advantage over his adversary.</p> | <p>If you wish to form a sound counter-position, the position of the body and arms must be such that without touching the adversary's sword you are defended in the straight line from the point of his sword to your body, so that without making any movement of the body or the sword you are sure that your adversary cannot hit you in that line, but that if he wishes to attack he must move his sword elsewhere, with the result that his ''time'' is so long, that there is every opportunity to parry. But in forming this position care must be taken that your sword is held in such a way as to be stronger than your adversary's, so that it may offer resistance in defence. This rule can be observed against all positions and changes of your adversary, whether accompanied by the dagger or any other defensive weapon, or when you use the sword alone. He who can most subtly maintain this guard will have a great advantage over his adversary.</p> | ||

| Line 208: | Line 209: | ||

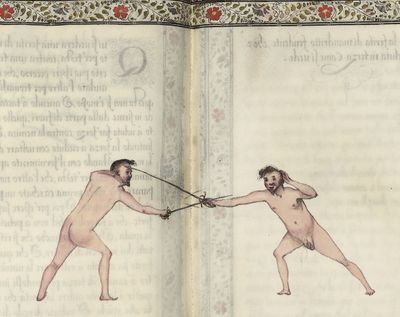

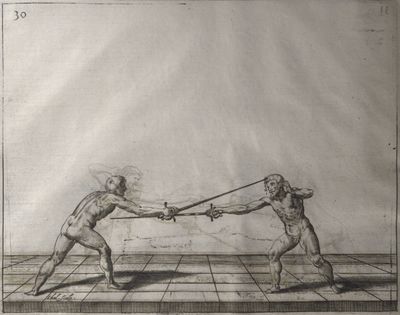

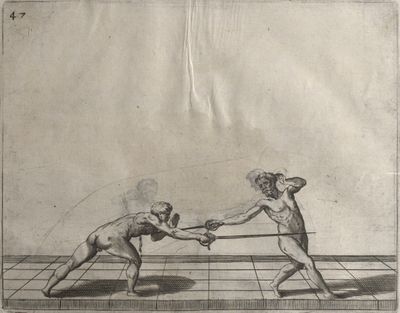

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

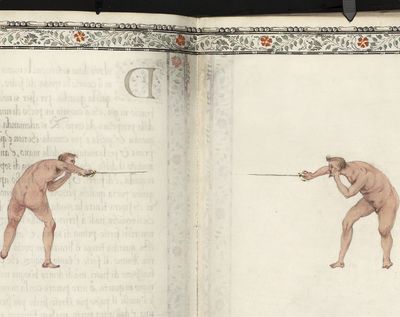

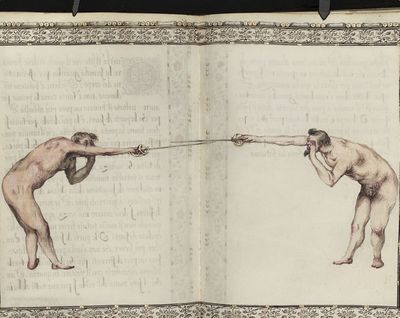

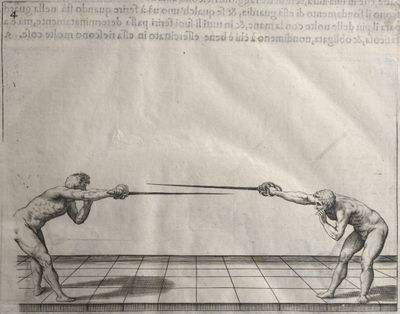

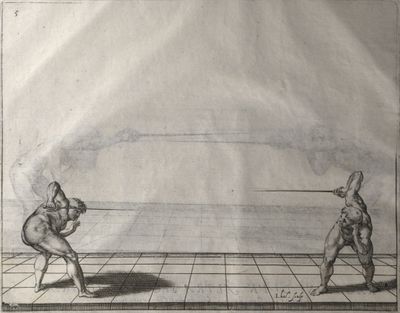

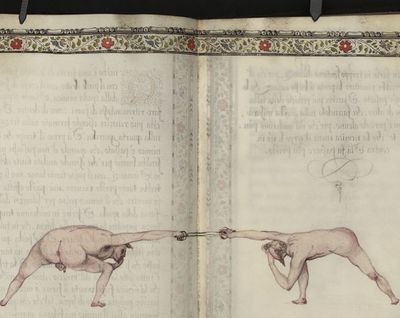

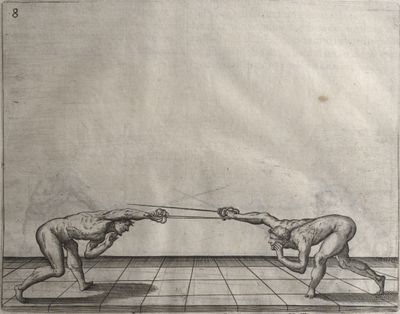

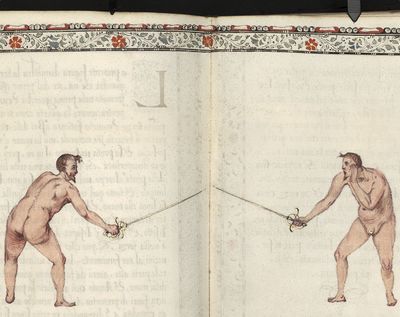

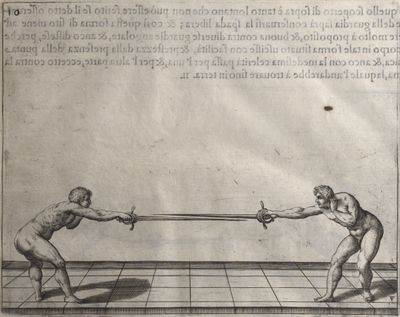

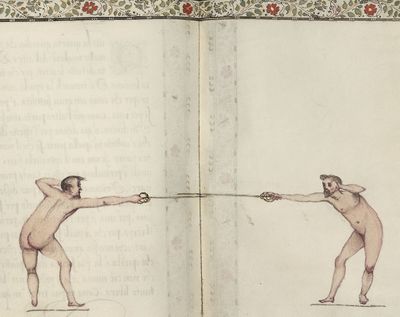

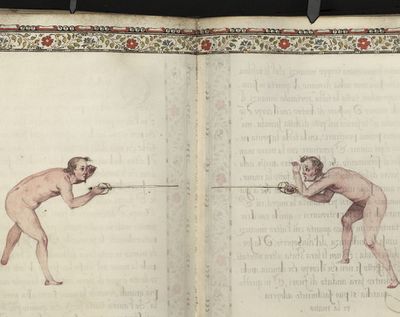

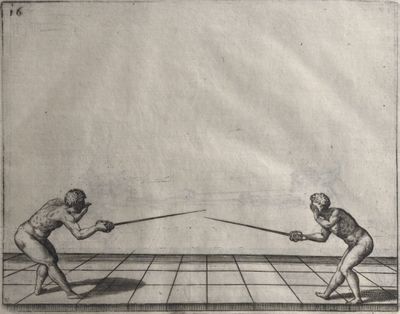

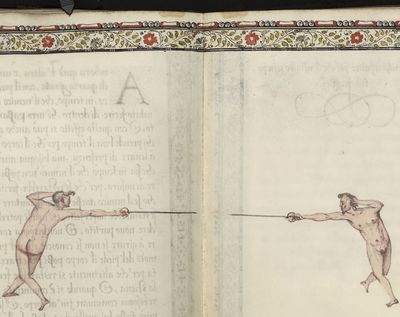

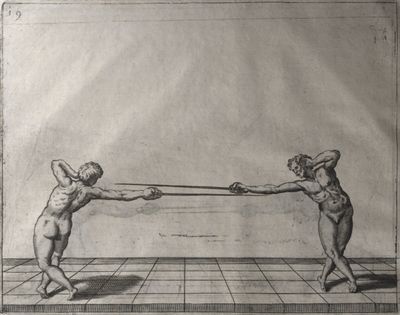

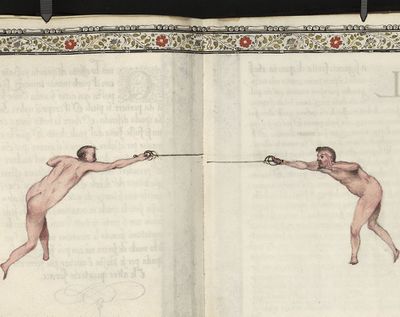

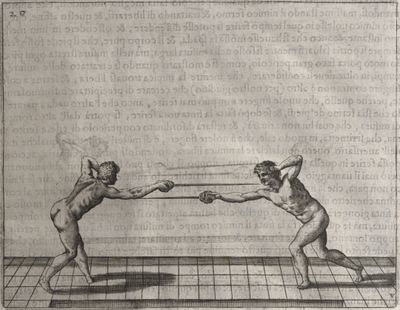

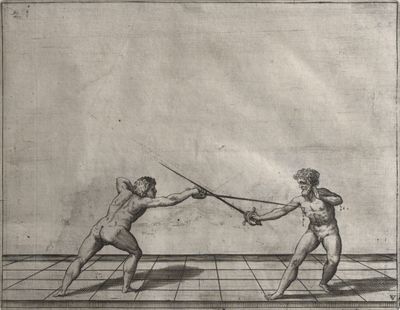

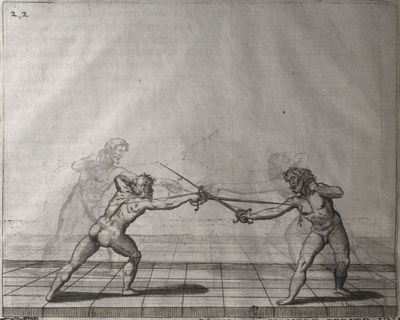

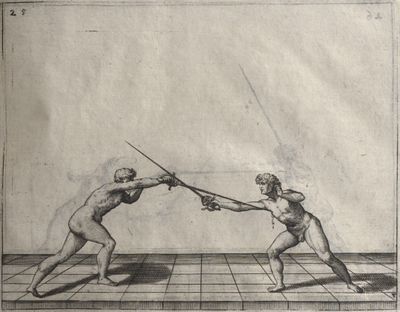

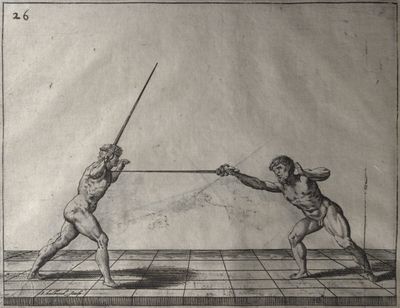

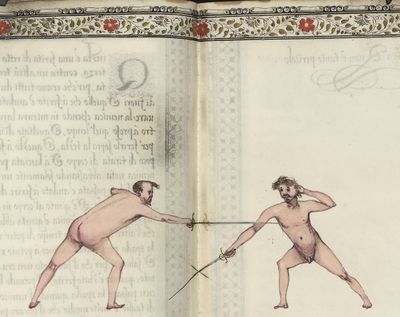

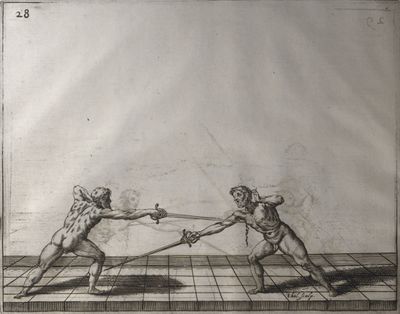

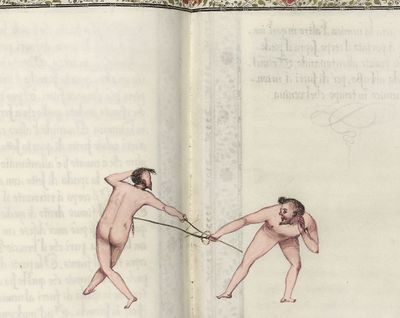

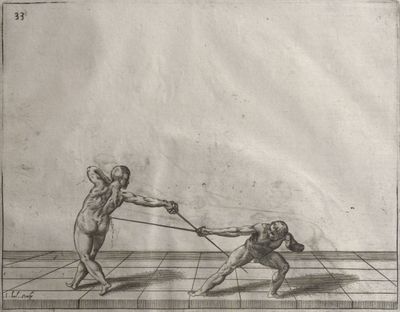

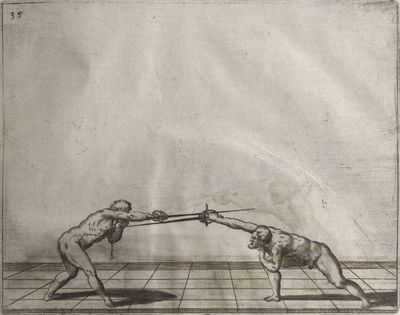

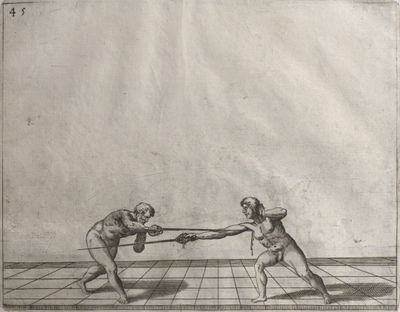

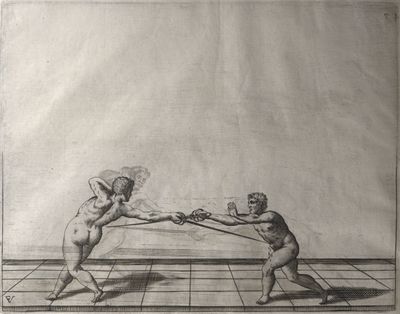

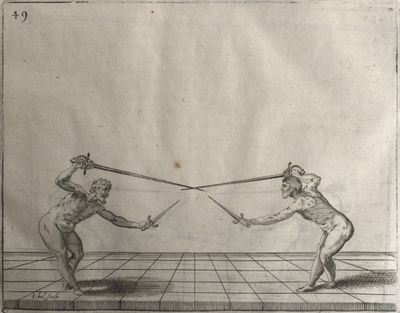

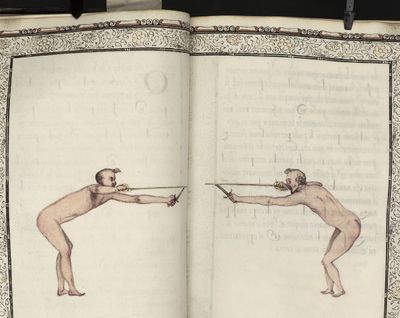

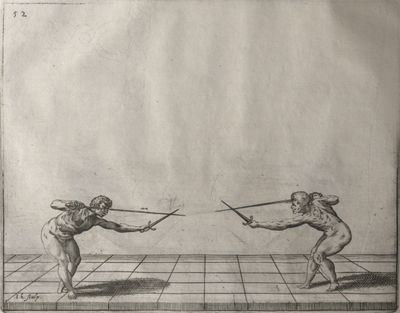

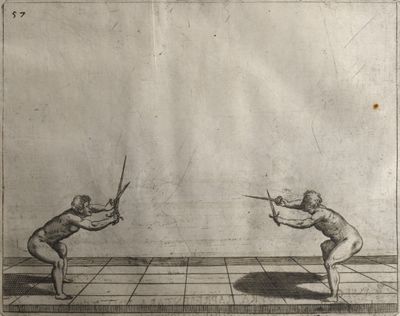

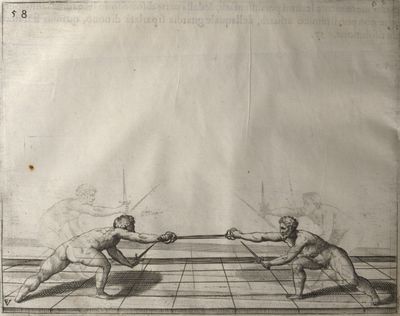

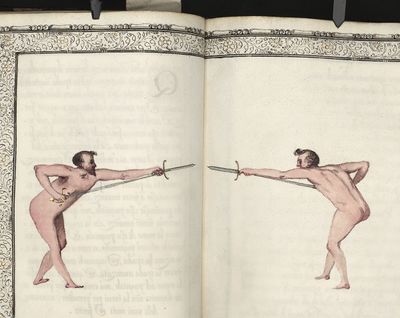

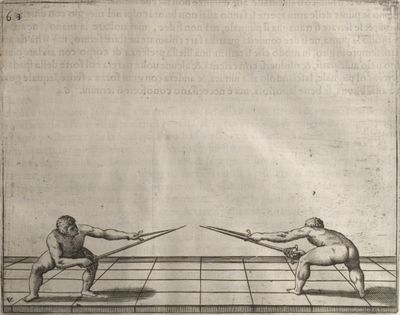

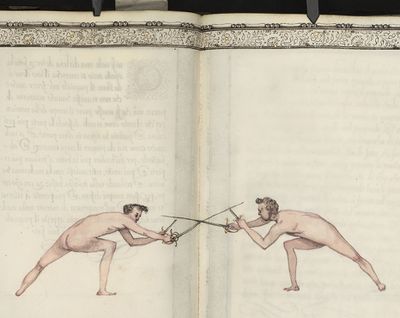

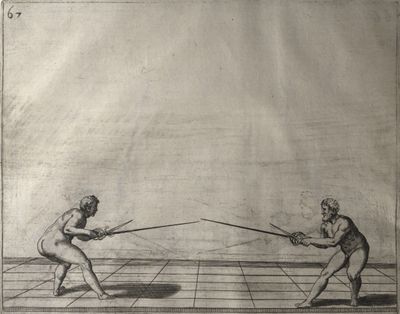

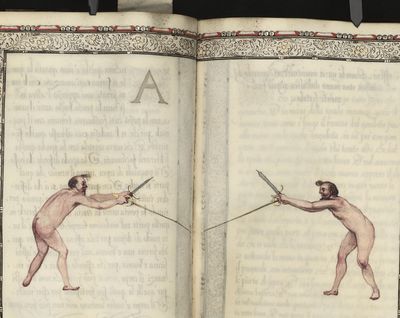

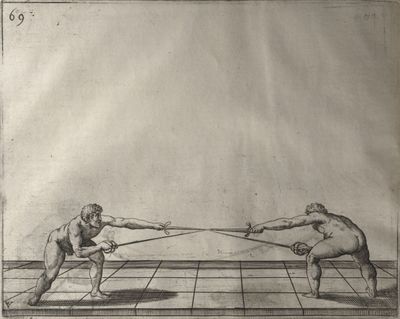

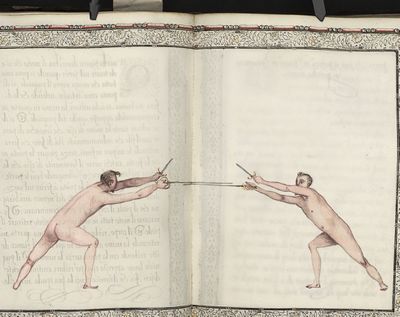

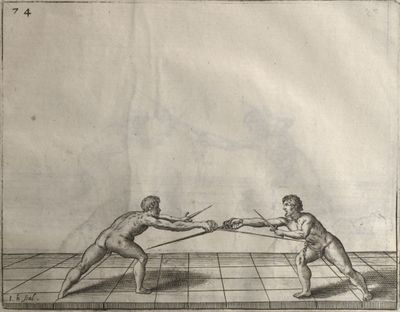

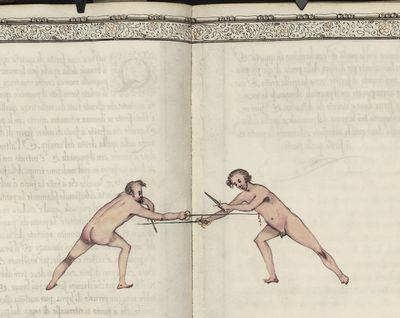

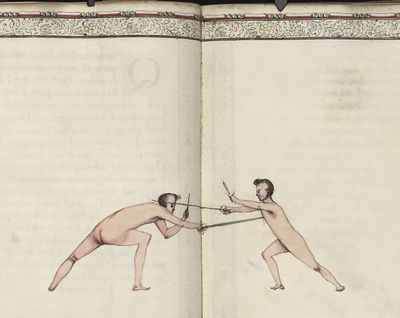

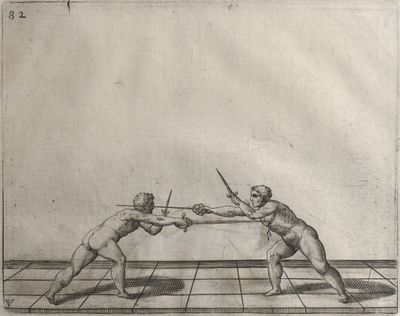

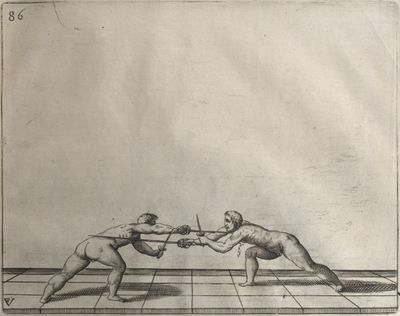

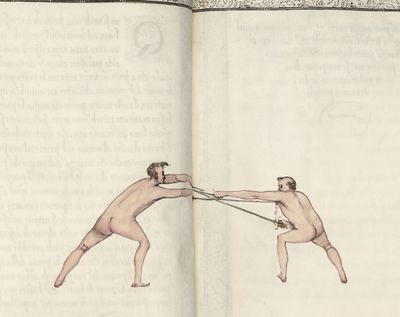

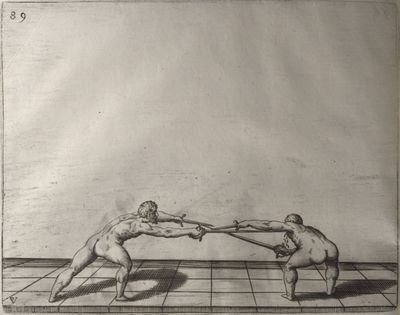

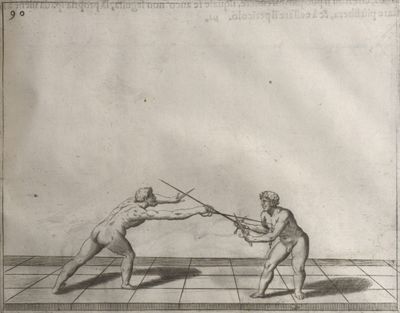

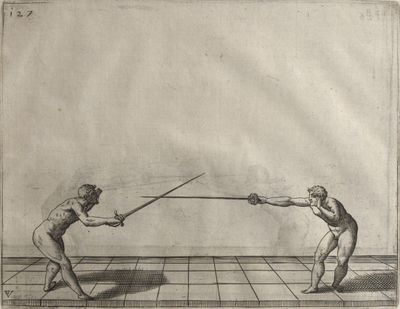

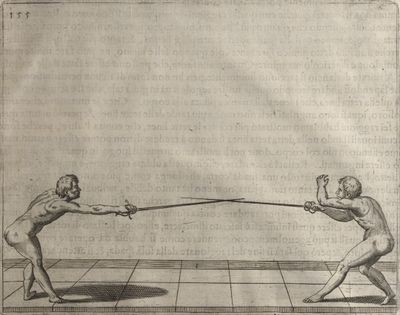

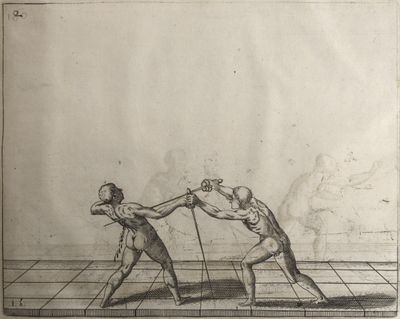

| − | | <p>[5] '''Explanation of the two distances, wide and close, and how to acquire the one or the other with least danger.'''</p> | + | | <p>[5] '''Explanation of the two distances, wide and close, and how to acquire the one or the other with least danger.'''<br/><br/></p> |

<p>You are within wide distance when by advancing the rear foot to the front you can make a hit. After forming the counter-position a little out of distance, you must begin to advance the foot in order to get within the required distance. But you must be on your guard, lest your adversary, being steady, at the moment when you move your foot to advance it, should advance his too and hit at the same time. Therefore, you must move it very carefully, remembering that your adversary may effect something during the movement. After forming the counter-position you must endeavour to throw him into disorder, or at least make some feint in order to have an opportunity to hit. Thus prepared for what may happen you are more guarded and can better resist attack. When you are within wide distance and your adversary makes some movement of his foot, provided he does not break ground, you can hit him in the nearest exposed part, even if he has not moved his weapons. This could not be done if he moved his weapons and stood firm on his feet, the reason being that a movement of the foot is slower than that of the weapons, and therefore he could parry before your sword arrived, while he remained steady; if there were no other way he could protect himself by breaking ground, so that your sword could not reach. Being thrown into disorder you would then be in danger of being hit before you had recovered. Therefore whenever he gives an opportunity without moving his feet, it would be better to approach within close distance in that time. In that distance you can reach with the sword by merely bending the body, without moving the feet, and the adversary is forced to retire to get out of such danger. If he does not move you could hit him even though he retained the advantage of the counter-position. If your adversary does not move, you can sometimes make a hit by judging the distance from the point of your sword to your adversary's body and the distance from the ''forte'' of his sword. If you consider both how much you must advance the point and how far you must move it from the adversary's ''forte'', and understand that the time required for him to parry is the same as for you to hit, the sword will arrive before he has parried by the advantage of having moved first. If you see that his body is little exposed, as may happen, since one guard covers more than another, you can then attempt to hit in the exposed part, and as he moves to the defence change your line and hit in the second exposed part.</p> | <p>You are within wide distance when by advancing the rear foot to the front you can make a hit. After forming the counter-position a little out of distance, you must begin to advance the foot in order to get within the required distance. But you must be on your guard, lest your adversary, being steady, at the moment when you move your foot to advance it, should advance his too and hit at the same time. Therefore, you must move it very carefully, remembering that your adversary may effect something during the movement. After forming the counter-position you must endeavour to throw him into disorder, or at least make some feint in order to have an opportunity to hit. Thus prepared for what may happen you are more guarded and can better resist attack. When you are within wide distance and your adversary makes some movement of his foot, provided he does not break ground, you can hit him in the nearest exposed part, even if he has not moved his weapons. This could not be done if he moved his weapons and stood firm on his feet, the reason being that a movement of the foot is slower than that of the weapons, and therefore he could parry before your sword arrived, while he remained steady; if there were no other way he could protect himself by breaking ground, so that your sword could not reach. Being thrown into disorder you would then be in danger of being hit before you had recovered. Therefore whenever he gives an opportunity without moving his feet, it would be better to approach within close distance in that time. In that distance you can reach with the sword by merely bending the body, without moving the feet, and the adversary is forced to retire to get out of such danger. If he does not move you could hit him even though he retained the advantage of the counter-position. If your adversary does not move, you can sometimes make a hit by judging the distance from the point of your sword to your adversary's body and the distance from the ''forte'' of his sword. If you consider both how much you must advance the point and how far you must move it from the adversary's ''forte'', and understand that the time required for him to parry is the same as for you to hit, the sword will arrive before he has parried by the advantage of having moved first. If you see that his body is little exposed, as may happen, since one guard covers more than another, you can then attempt to hit in the exposed part, and as he moves to the defence change your line and hit in the second exposed part.</p> | ||

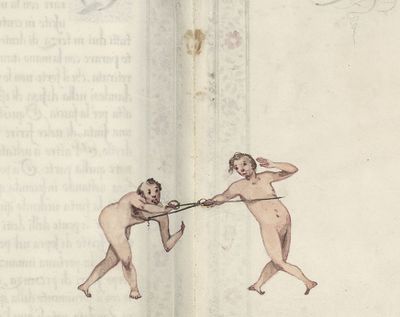

| Line 225: | Line 226: | ||

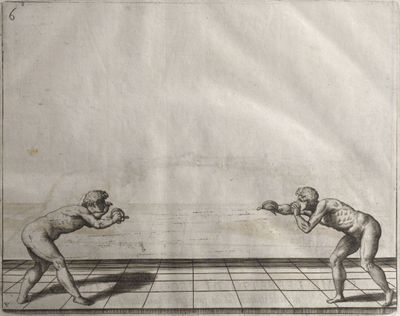

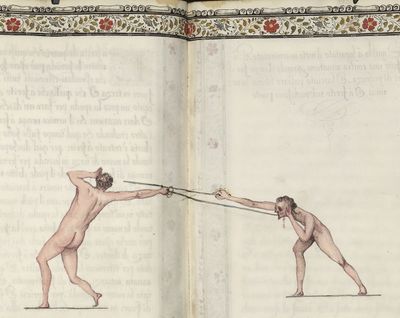

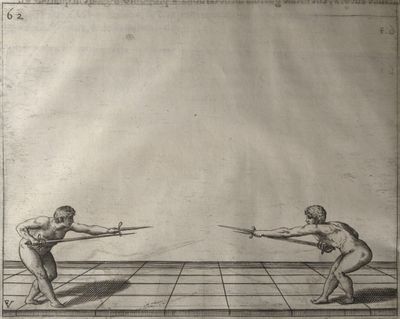

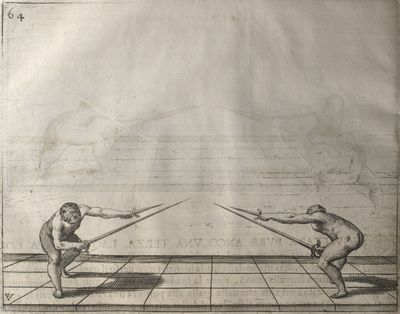

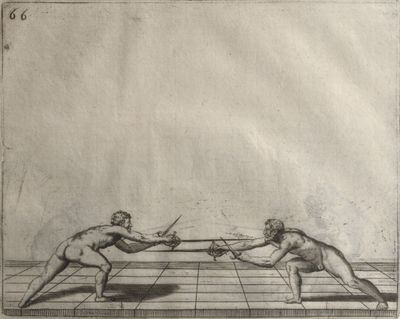

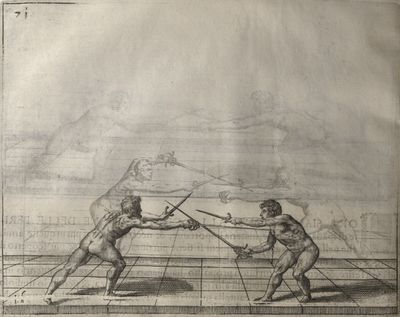

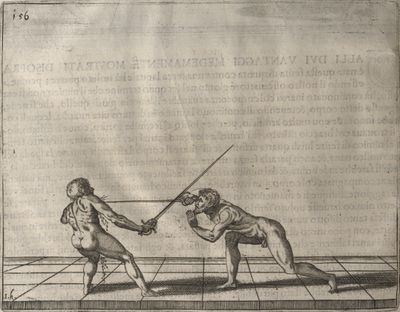

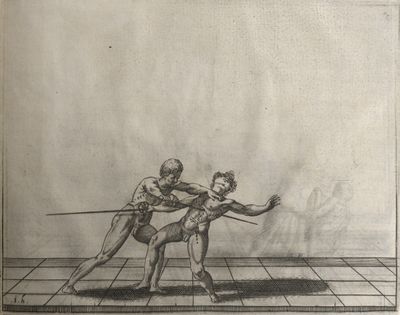

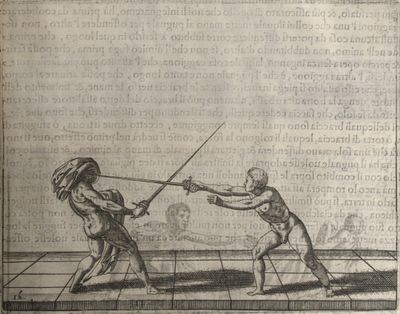

| <p>[6] '''Discourse on rushing in with the sword extended and the principles of the two times, showing that it is better to control the sword and observe the correct time.'''</p> | | <p>[6] '''Discourse on rushing in with the sword extended and the principles of the two times, showing that it is better to control the sword and observe the correct time.'''</p> | ||

| − | <p>There are some who, in endeavouring to hit with the point, hurl the arm violently forward so as to give it greater force. This method is not good for the reasons which we shall bring forward. In the first place when you rush in with the sword, should your adversary anticipate you and defend the part where you intended to hit, you cannot change your line, as would be necessary, so that the adversary is sure of his defence. If he has also realised the weakest part of your thrust and pushed your sword in the direction in which it is being naturally carried, he will drive it out of line all the more quickly. His defence will be very simple without using any force, because if he pushes the sword in the direction in which it is naturally falling, it will fall the quicker without any resistance. In this manner his ''faible'' is stronger than the ''forte'' of the hitter. Moreover in completing the rush the point of the sword drops so that it cannot hit exactly the point aimed at, and <sup>also</sup> at the end of the extension it is impossible to prevent the arm and sword from dropping to the great advantage of your adversary. Further after one rush it is impossible to make another without withdrawing the arm again, which takes so long that, if the adversary has not hit at the first fall of your sword he could hit while you are withdrawing your arm, and recover before the second rush, with excellent opportunity of parrying and hitting even if he did it in two ''times'', that is parrying first and then hitting. The rule of the two ''times'' then would be good enough against such a method, and all the more successful as those who rush cannot make any good feint; for in feinting they move the foot or the body without advancing the sword, or if they advance it often withdraw it even further than before in order to hit with greater force, a very slow and dangerous ''time''. | + | <p>There are some who, in endeavouring to hit with the point, hurl the arm violently forward so as to give it greater force. This method is not good for the reasons which we shall bring forward. In the first place when you rush in with the sword, should your adversary anticipate you and defend the part where you intended to hit, you cannot change your line, as would be necessary, so that the adversary is sure of his defence. If he has also realised the weakest part of your thrust and pushed your sword in the direction in which it is being naturally carried, he will drive it out of line all the more quickly. His defence will be very simple without using any force, because if he pushes the sword in the direction in which it is naturally falling, it will fall the quicker without any resistance. In this manner his ''faible'' is stronger than the ''forte'' of the hitter. Moreover in completing the rush the point of the sword drops so that it cannot hit exactly the point aimed at, and <sup>also</sup> at the end of the extension it is impossible to prevent the arm and sword from dropping to the great advantage of your adversary. Further after one rush it is impossible to make another without withdrawing the arm again, which takes so long that, if the adversary has not hit at the first fall of your sword he could hit while you are withdrawing your arm, and recover before the second rush, with excellent opportunity of parrying and hitting even if he did it in two ''times'', that is parrying first and then hitting. The rule of the two ''times'' then would be good enough against such a method, and all the more successful as those who rush cannot make any good feint; for in feinting they move the foot or the body without advancing the sword, or if they advance it often withdraw it even further than before in order to hit with greater force, a very slow and dangerous ''time''.</p> |

| − | In treating of the rule of the two ''time'', we say that, although it may succeed against some, it is not to be compared with the rule of parrying and hitting at the same time, because the true and safe method is to meet the body as it advances, before it has had time to withdraw and recover. If you then pursue you give an opportunity for parrying and hitting again. It has been our experience, that most of those who observe this rule of two ''times'', if they can engage the adversary's sword, generally beat it in order then to proceed with the stroke. This would be successful but for the danger of being deceived. He whose sword has been beaten on the ''faible'' certainly cannot hit at the same time, as he is thrown into disorder by the beat. But if he happens to disengage he causes the sword which has beaten and missed to drop still further, and has an excellent chance of hitting. Even if he made a feint of beating, so that when the adversary disengaged he might beat in another part, he would still be in danger of being hit, because the adversary might make a feint of disengaging and return, and in this way the one who had meant to beat would not be able to parry. Finally it may be taken as established that it is impossible to beat your adversary's sword without putting your own out of line. Moreover sometimes if you attempt to beat the ''faible'', according to rule, you meet the adversary's ''forte'', which he has pushed forward, so that the beat fails and your adversary proceeds to hit without your being able to prevent him. In dealing with one who does not rush, but controls his sword, even though you beat his ''faible'', his ''forte'' does not move, so that he can parry. Therefore, we conclude for these reasons and for many others which might be adduced, that it is better to parry and hit at the same time, though with the sword alone great judgment is required to effect the two at one moment. As to controlling the sword or thrusting with violence, controlling it is beyond comparison better, first because he who controls his sword, when it is beaten by the adversary, who means to hit in another line, can let it yield in the direction of the beat, and the ''forte'' will still defend, if the sword is held well advanced. Further it is certain that when your sword is beaten, it is immediately freed. Similarly it is more useful to know how to be master of your sword, to engage the adversary's faible and make a hit as opportunity offers, always holding his sword in subjection. If he cannot free his sword he cannot hit. Therefore this rule can be followed only by one who moves his sword without violence, works in such a way as to be always master of it, and if he is prevented by his adversary in any plan can abandon it and adopt another. He will hit at the very moment when his adversary has meant to prevent him, and without deviating his point or withdrawing it he will be able to carry it on to the adversary's body. The principle to be observed is this, that in proceeding to make a hit either by a feint of disengaging or any other change, when once you have begun to approach, the point toward the adversary, you must continue until you reach the body; for if you check the sword in order to disengage or change your line you will not arrive in time. This principle cannot be observed by one who rushes, so that the difference is easily understood. Moreover the sword which is held firm and accompanied by the foot and the body has greater force and exactness. He who so hold[!] it always controls it and does not let it drop after a hit. He has only to withdraw his foot in order to bring his body to safety, unless he has passed, and to engage the adversary's sword again. If your adversary as you withdraw, pursues or advances, you can hit again, defending at the same time. All this is because of the union between the sword, the feet and the body. If this rule is observed in the manner we have described, your parrying will be safe, whereas with the rule of the two ''times'' it is false; this will be better understood in its place.</p> | + | |

| + | <p>In treating of the rule of the two ''time'', we say that, although it may succeed against some, it is not to be compared with the rule of parrying and hitting at the same time, because the true and safe method is to meet the body as it advances, before it has had time to withdraw and recover. If you then pursue you give an opportunity for parrying and hitting again. It has been our experience, that most of those who observe this rule of two ''times'', if they can engage the adversary's sword, generally beat it in order then to proceed with the stroke. This would be successful but for the danger of being deceived. He whose sword has been beaten on the ''faible'' certainly cannot hit at the same time, as he is thrown into disorder by the beat. But if he happens to disengage he causes the sword which has beaten and missed to drop still further, and has an excellent chance of hitting. Even if he made a feint of beating, so that when the adversary disengaged he might beat in another part, he would still be in danger of being hit, because the adversary might make a feint of disengaging and return, and in this way the one who had meant to beat would not be able to parry. Finally it may be taken as established that it is impossible to beat your adversary's sword without putting your own out of line. Moreover sometimes if you attempt to beat the ''faible'', according to rule, you meet the adversary's ''forte'', which he has pushed forward, so that the beat fails and your adversary proceeds to hit without your being able to prevent him. In dealing with one who does not rush, but controls his sword, even though you beat his ''faible'', his ''forte'' does not move, so that he can parry. Therefore, we conclude for these reasons and for many others which might be adduced, that it is better to parry and hit at the same time, though with the sword alone great judgment is required to effect the two at one moment. As to controlling the sword or thrusting with violence, controlling it is beyond comparison better, first because he who controls his sword, when it is beaten by the adversary, who means to hit in another line, can let it yield in the direction of the beat, and the ''forte'' will still defend, if the sword is held well advanced. Further it is certain that when your sword is beaten, it is immediately freed. Similarly it is more useful to know how to be master of your sword, to engage the adversary's faible and make a hit as opportunity offers, always holding his sword in subjection. If he cannot free his sword he cannot hit. Therefore this rule can be followed only by one who moves his sword without violence, works in such a way as to be always master of it, and if he is prevented by his adversary in any plan can abandon it and adopt another. He will hit at the very moment when his adversary has meant to prevent him, and without deviating his point or withdrawing it he will be able to carry it on to the adversary's body. The principle to be observed is this, that in proceeding to make a hit either by a feint of disengaging or any other change, when once you have begun to approach, the point toward the adversary, you must continue until you reach the body; for if you check the sword in order to disengage or change your line you will not arrive in time. This principle cannot be observed by one who rushes, so that the difference is easily understood. Moreover the sword which is held firm and accompanied by the foot and the body has greater force and exactness. He who so hold[!] it always controls it and does not let it drop after a hit. He has only to withdraw his foot in order to bring his body to safety, unless he has passed, and to engage the adversary's sword again. If your adversary as you withdraw, pursues or advances, you can hit again, defending at the same time. All this is because of the union between the sword, the feet and the body. If this rule is observed in the manner we have described, your parrying will be safe, whereas with the rule of the two ''times'' it is false; this will be better understood in its place.</p> | ||

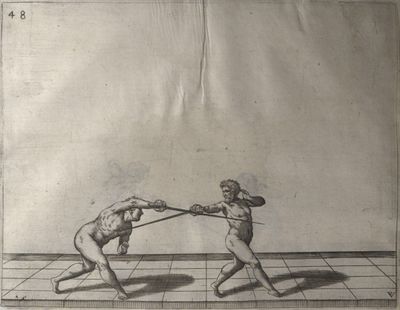

| | | | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 252: | Line 254: | ||

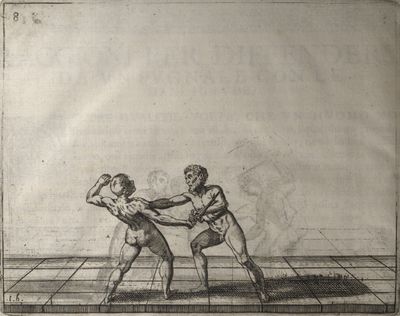

| <p>[8] In ''good and false Parrying'', and on some who, with the sword alone, parry with the left arm.</p> | | <p>[8] In ''good and false Parrying'', and on some who, with the sword alone, parry with the left arm.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The parry partakes of the nature of fear, for he who did not fear some disadvantage, would not put himself on the defence which we may call obedience and subjection, all the more so when it is forced. ''He who does'' not wish to be hit is forced to parry. When we can put our adversary under this obligation, we consider it a great advantage, for while he is under the necessity of parrying he may be hit in the line he uncovers by his movement, so that his defence proves vain. Therefore some say that parrying is false, which we admit, when it is done alone, for when you make a feint in one part and hit in another, your adversary moves to the parry, and, thinking to defend himself, is deceived by the feint, when he might, instead of parrying, have allowed the thrust to pass. To avoid thrusts is always better - that is with the sword alone, for with the sword and the dagger you can parry with one weapon and hit at the same time with the other, so that the defence is easier. But with the sword alone you must be more judicious, as it has to perform the two functions of defence and attack at the same time, in order that the parry may be safe. If you are forced to parry by a cut you must give the opposition with your ''forte'' where the adversary's sword is about to fall, and at the same time drive the point in with great swiftness, in order that it may arrive before your adversary's falls, so that he may neither avoid it nor be able to hit. This is an excellent rule, because the cut is shorter than the thrust. If you see that you cannot arrive with a ''time'' thrust, there is no need to parry, for it follows that your adversary cannot reach. If you are in doubt, you can withdraw the body a little and let his sword fall, and hit at the end of its fall. If you wish to parry knowing that you cannot hit, you must still carry your point as if you meant to hit, as this prevents the adversary from changing his line. Thus you free yourself from subjection and force your adversary to take the defensive, since he is threatened with a ''time'' thrust, and his subjection gives an opportunity for a hit. Hence it is never necessary to parry without hitting, or making a feint of hitting in order to force your adversary to parry, so that you free yourself from danger and at the same time place him in danger. It often happens that one who attempts a cut makes a large circle, so that you may hit him and recover before his sword falls. For in addition to the fact that the cut is slower, as we have said, it is also shorter. This you may do by understanding your adversary's movements and his distances. When the distance is so great that you cannot reach, you must make a feint of hitting while the adversary is making his circle in order to make it fall all the more precipitately and then sieze[!] the opportunity to hit in the part uncovered by its fall. This is instead of parrying at a great distance. But within close distance you may hit before your adversary's sword descends, since the thrust is finished before the cut, so that by withdrawing the left foot and recovering the body you may get into safety and your adversary fail to reach. It is true that this stroke would not be so deadly, since with the parry you can advance further and hit with more vigour and can pass right to the adversary's body. If you do not desire to pass it is necessary to understand how to maintain close distance and to control the feet in such a manner as to break ground in order to avoid a hit. This method is very successful owing to the slowness of the cut and because your thrust reaches further and you move with greater swiftness, so that you can always recover. If these rules are observed he who attempts to cut will always be hit, as we have already said. If in this place we must mention those who first cut at their adversary's sword in order to throw it into disorder, and then we shall not treat of them at greater length, because he who understands ''time'' and disengaging can easily save his sword against a beat.</p> | + | <p>The parry partakes of the nature of fear, for he who did not fear some disadvantage, would not put himself on the defence which we may call obedience and subjection, all the more so when it is forced. ''He who does'' not wish to be hit is forced to parry. When we can put our adversary under this obligation, we consider it a great advantage, for while he is under the necessity of parrying he may be hit in the line he uncovers by his movement, so that his defence proves vain. Therefore some say that parrying is false, which we admit, when it is done alone, for when you make a feint in one part and hit in another, your adversary moves to the parry, and, thinking to defend himself, is deceived by the feint, when he might, instead of parrying, have allowed the thrust to pass. To avoid thrusts is always better - that is with the sword alone, for with the sword and the dagger you can parry with one weapon and hit at the same time with the other, so that the defence is easier. But with the sword alone you must be more judicious, as it has to perform the two functions of defence and attack at the same time, in order that the parry may be safe. If you are forced to parry by a cut you must give the opposition with your ''forte'' where the adversary's sword is about to fall, and at the same time drive the point in with great swiftness, in order that it may arrive before your adversary's falls, so that he may neither avoid it nor be able to hit. This is an excellent rule, because the cut is shorter than the thrust. If you see that you cannot arrive with a ''time'' thrust, there is no need to parry, for it follows that your adversary cannot reach. If you are in doubt, you can withdraw the body a little and let his sword fall, and hit at the end of its fall. If you wish to parry knowing that you cannot hit, you must still carry your point as if you meant to hit, as this prevents the adversary from changing his line. Thus you free yourself from subjection and force your adversary to take the defensive, since he is threatened with a ''time'' thrust, and his subjection gives an opportunity for a hit. Hence it is never necessary to parry without hitting, or making a feint of hitting in order to force your adversary to parry, so that you free yourself from danger and at the same time place him in danger. It often happens that one who attempts a cut makes a large circle, so that you may hit him and recover before his sword falls. For in addition to the fact that the cut is slower, as we have said, it is also shorter. This you may do by understanding your adversary's movements and his distances. When the distance is so great that you cannot reach, you must make a feint of hitting while the adversary is making his circle in order to make it fall all the more precipitately and then sieze[!] the opportunity to hit in the part uncovered by its fall. This is instead of parrying at a great distance. But within close distance you may hit before your adversary's sword descends, since the thrust is finished before the cut, so that by withdrawing the left foot and recovering the body you may get into safety and your adversary fail to reach. It is true that this stroke would not be so deadly, since with the parry you can advance further and hit with more vigour and can pass right to the adversary's body. If you do not desire to pass it is necessary to understand how to maintain close distance and to control the feet in such a manner as to break ground in order to avoid a hit. This method is very successful owing to the slowness of the cut and because your thrust reaches further and you move with greater swiftness, so that you can always recover. If these rules are observed he who attempts to cut will always be hit, as we have already said. If in this place we must mention those who first cut at their adversary's sword in order to throw it into disorder, and then hit, we shall not treat of them at greater length, because he who understands ''time'' and disengaging can easily save his sword against a beat.</p> |

<p>In defence of the thrust you must understand that its effect is swifter and more deadily[!]. In defending against it more subtlely[!] and ingenuity are required but less strength. To parry is more dangerous and deceptive owing to the rapid changes which it renders possible. It often happens that although you use the subtle combination of the parry and thrust at the same time, you are still deceived because your adversary, seeing your plan, removes his body out of the line, allows the point to pass and then hits in the part uncovered by the movement; so that avoiding is more subtle in defence and attack against one who makes a ''time''-thrust, if its use is well understood. You must then understand both this and the parry and know how to avail yourself of the one or other as occasion offers. It is even more effective to use both methods together, making half a motion to defend with the sword and half a motion with the body. This defence is quicker, disorders the sword less, and deprives the adversary of the advantage of changing his line. Such avoiding is more useful with the sword alone than with the sword and dagger, but the defence partly with the body and partly with the weapons may be observed in all cases.</p> | <p>In defence of the thrust you must understand that its effect is swifter and more deadily[!]. In defending against it more subtlely[!] and ingenuity are required but less strength. To parry is more dangerous and deceptive owing to the rapid changes which it renders possible. It often happens that although you use the subtle combination of the parry and thrust at the same time, you are still deceived because your adversary, seeing your plan, removes his body out of the line, allows the point to pass and then hits in the part uncovered by the movement; so that avoiding is more subtle in defence and attack against one who makes a ''time''-thrust, if its use is well understood. You must then understand both this and the parry and know how to avail yourself of the one or other as occasion offers. It is even more effective to use both methods together, making half a motion to defend with the sword and half a motion with the body. This defence is quicker, disorders the sword less, and deprives the adversary of the advantage of changing his line. Such avoiding is more useful with the sword alone than with the sword and dagger, but the defence partly with the body and partly with the weapons may be observed in all cases.</p> | ||

| Line 271: | Line 273: | ||

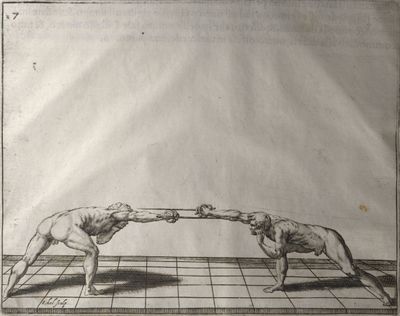

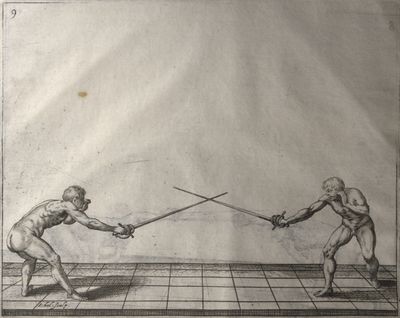

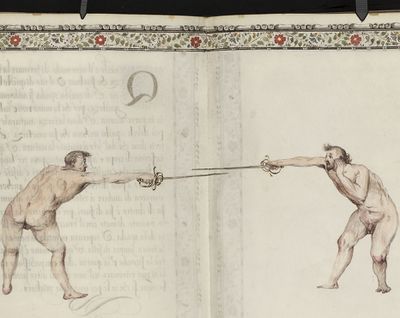

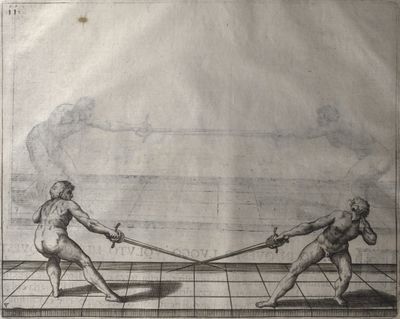

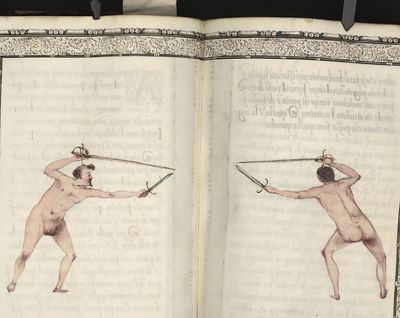

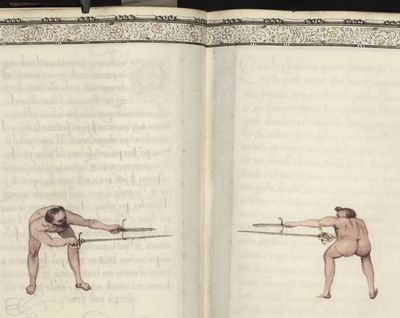

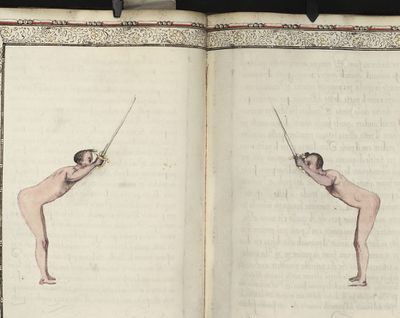

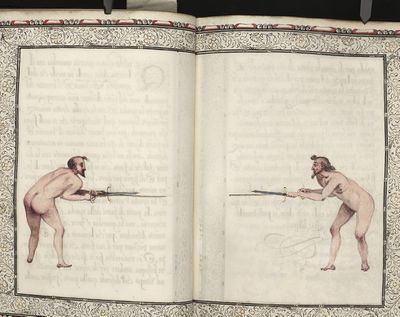

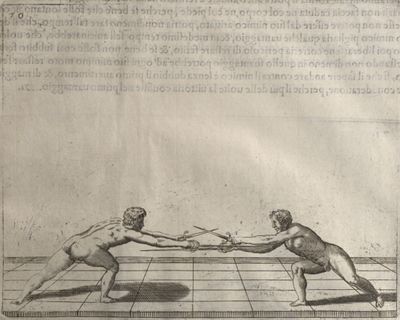

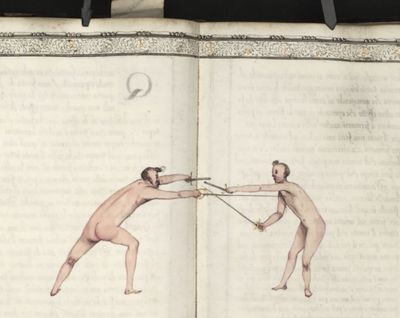

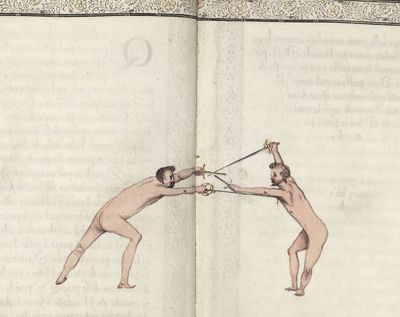

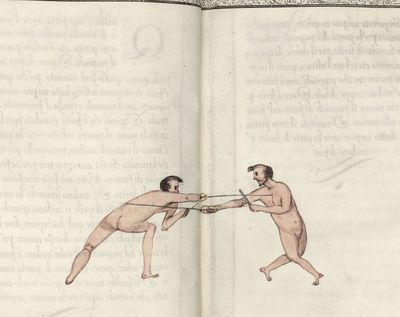

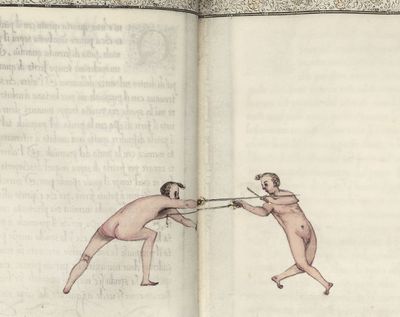

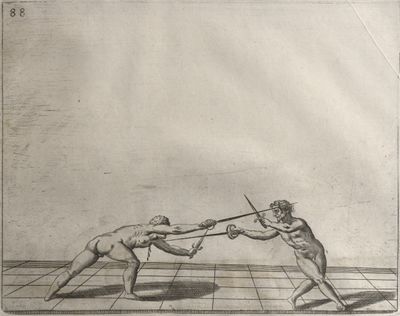

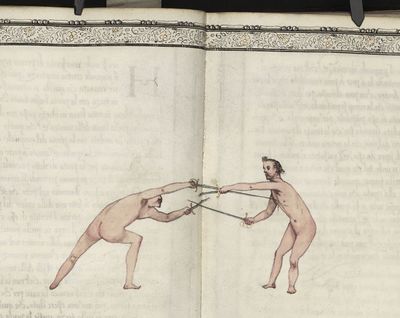

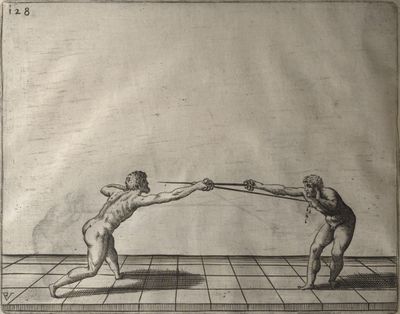

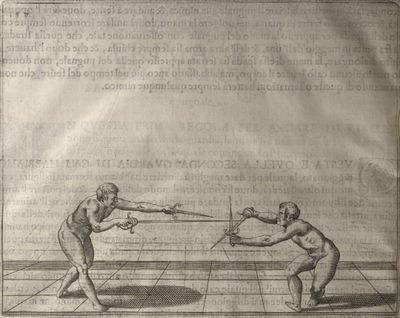

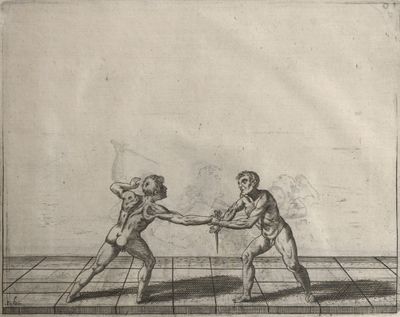

| <p>[9] '''Engaging the sword'''. How it is done and when completed.</p> | | <p>[9] '''Engaging the sword'''. How it is done and when completed.</p> | ||

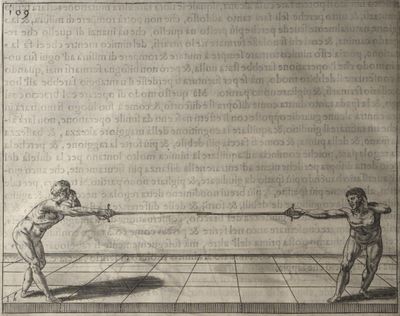

| − | <p>To engage the sword is to gain an advantage over it; it is a kind of counter-position with some difference, because often you have engaged, the adversary's sword without completely closing the line from his | + | <p>To engage the sword is to gain an advantage over it; it is a kind of counter-position with some difference, because often you have engaged, the adversary's sword without completely closing the line from his point to your body. But it has this advantage, that your adversary cannot hit without passing your ''forte'', which is so near his point, that you can find the point while he is moving to make the lunge. The counter-position is not considered well formed except when the line from his point to your body is fully defended. But the same advantage may be obtained by relative strength, so that you are considered to have engaged, when you are sure that your sword is stronger than the adversary's and cannot be pushed aside, but can push his aside. When on guard and wishing to engage the adversary's sword, you must carry your point towards his, with the fourth part of the blade against his fourth, but rather more of your fourth part than of his, for that little more, though little, will be enough to give you the advantage, when you have engaged his sword at the weaker part. You must bear in mind that the sword is always stronger in the line in which the point is directed, and in order to advance in that line ---------- you must know how to carry your body and sword in such a way that their strength is in the same direc-<ref name="hyphen">There's no conclusion of this word on the next page, just a new sentence.</ref> This depends to a great extent on the wrist, as will be seen in the plate illustrating the guard on the inside, which is the most difficult. You must also take care, in trying to engage the fourth part, to keep your point at such a distance from the adversary's sword, that he will not have time to push forward the third or even the second part, with the result that while meaning to engage his ''faible'' you would have engaged his ''forte''. This might happen owing to the distance between the two swords, for the amount you can push your sword forward before engaging is the same as the distance. You must move at the same time as he moves, otherwise you might be hit. Moreover, although the space between the two points were small, while you were advancing to engage, the adversary might perceive this and make an angle, which would strengthen him and bring him away from your advance. If you should push on in order to hit when within distance, his ''forte'' would have penetrated so far, that if you had moved in order to engage his sword, you would be unable to defend yourself, and would be hit. Further, if while you are trying to engage, he moved his body away from your point, he could pass right on to your body, before your sword had returned into line. To prevent your adversary's doing this you must first consider the distance between your bodies, and then move forward to engage his sword, carrying your sword without constraint so as to be free to abandon your first plan, when your adversary seizes the opportunity, and drives the point on to his body, bringing the ''forte'' where you intended to put the point. In this way you will hit the adversary at the moment when he is pushing forward. You must remember that this rule applies to the guard on the inside, for, if on the outside, you must abandon your first movement and drop the point under the adversary's sword to the right side, carrying the ''forte'' where you meant to put the point. On this line too the present method is very successful if you similarly do not touch the sword in seeking to engage. The nearer the adversary is, the better and safer the method is. The advantage is in having brought your ''forte'' against his ''faible''.</p> |

<p>It often happens that the adversary, finding his sword is not molested is not aware that you have already gained the advantage, whereas if you touch his sword he more easily realises the fact, and can disengage or retreat or change his guard, in order to free himself, so that you lose your first advantage. Moreover if you touch the sword, you impede and disconcert yourself, so that if a ''time'' comes to hit, you cannot take it because of the resistance of your adversary's sword. Even when there is no resistance and the adversary disengages, you cannot prevent your point dropping a little, so that the ''time'' is lost. But if you keep your sword suspended, it is the more ready for every opportunity, there is more use made of ''time'', and there is no necessity to force his sword, which often leads to scuffling. If you do not touch swords, that cannot happen. When then you advance to engage your adversary's sword and he moves to meet you at the same time, the one who first yields with the sword and drives on to the body, can hit before the other touches swords, or in the same instant. If you do not wish to try a hit, you can lower your point towards the ground to prevent the adversary's engaging, and if he follows it you can thrust while his sword is falling. There are many other ways of preventing your adversary from engaging your sword, except when the point hits, especially if you have won the advantage of the ''forte'' against the ''faible'' and the swords are in position. In endeavouring to acquire the advantage over the adversary's sword you must take care not to advance the point so far in your desire to be the stronger, that he can pass in one line or another, before you can direct your point. If you observe these rules you will without doubt gain the control of your adversary's sword, which is the first part of victory. Though your adversary takes advantage of the ''time'' he will still be hit. To prevent your getting this advantage he will have to retreat, changing the position of his body and sword and to adopt new devices, which are countless. The one who is more subtle in his movements will maintain his sword the freer.</p> | <p>It often happens that the adversary, finding his sword is not molested is not aware that you have already gained the advantage, whereas if you touch his sword he more easily realises the fact, and can disengage or retreat or change his guard, in order to free himself, so that you lose your first advantage. Moreover if you touch the sword, you impede and disconcert yourself, so that if a ''time'' comes to hit, you cannot take it because of the resistance of your adversary's sword. Even when there is no resistance and the adversary disengages, you cannot prevent your point dropping a little, so that the ''time'' is lost. But if you keep your sword suspended, it is the more ready for every opportunity, there is more use made of ''time'', and there is no necessity to force his sword, which often leads to scuffling. If you do not touch swords, that cannot happen. When then you advance to engage your adversary's sword and he moves to meet you at the same time, the one who first yields with the sword and drives on to the body, can hit before the other touches swords, or in the same instant. If you do not wish to try a hit, you can lower your point towards the ground to prevent the adversary's engaging, and if he follows it you can thrust while his sword is falling. There are many other ways of preventing your adversary from engaging your sword, except when the point hits, especially if you have won the advantage of the ''forte'' against the ''faible'' and the swords are in position. In endeavouring to acquire the advantage over the adversary's sword you must take care not to advance the point so far in your desire to be the stronger, that he can pass in one line or another, before you can direct your point. If you observe these rules you will without doubt gain the control of your adversary's sword, which is the first part of victory. Though your adversary takes advantage of the ''time'' he will still be hit. To prevent your getting this advantage he will have to retreat, changing the position of his body and sword and to adopt new devices, which are countless. The one who is more subtle in his movements will maintain his sword the freer.</p> | ||

| Line 286: | Line 288: | ||

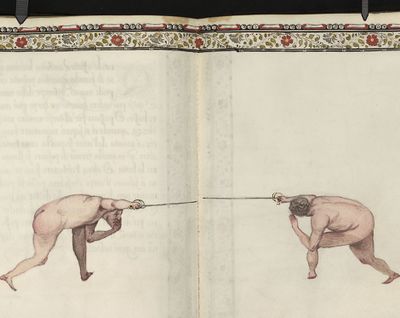

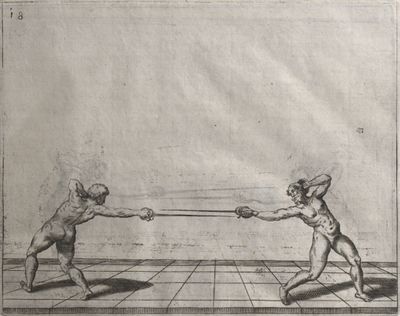

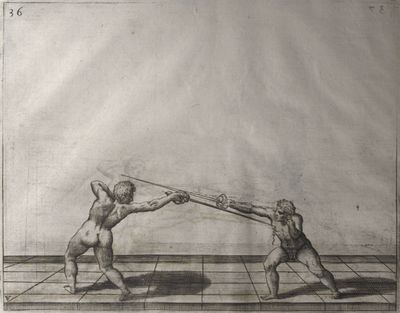

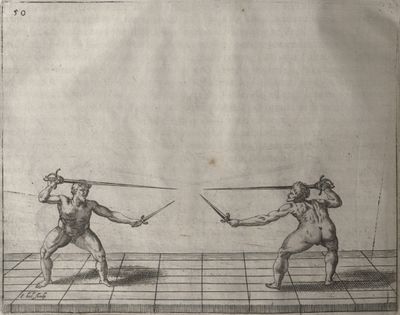

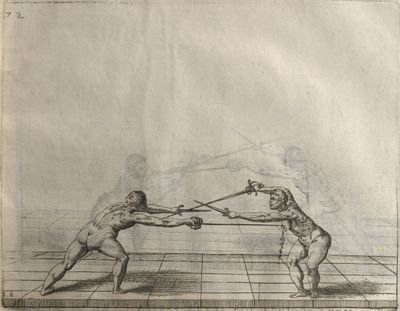

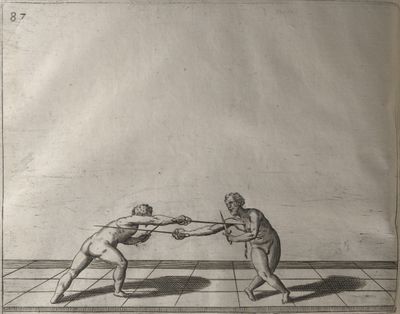

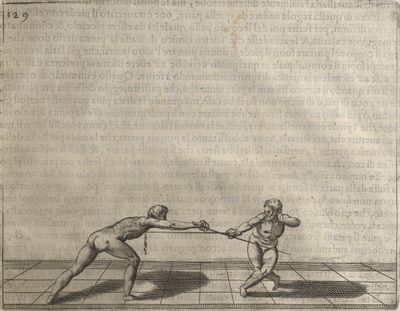

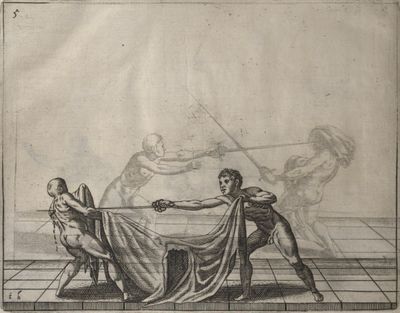

<p>A movement made by the adversary within distance is called a ''time''. For whatever is done out of distance can only be called either a movement or a change of front. ''Time'' then means an opportunity to hit or win some advantage over the adversary. This movement is given the name of ''time'' among the movements of fencing in order to convey the idea that at a given point of time it is the only possible movement. When the adversary moves, if you perceive an exposed part and are ready to hit in that part, the adversary will certainly be hit if within distance. For there cannot be two changes in one ''time'', and therefore you must take care that the ''time'' in which you wish to hit is not longer than the ''time'' offered by the adversary. In such a case he would have a chance to parry before your point arrived, and you would be in danger; whereas, if you understand the movement, you would succeed. This is called a ''time''-thrust. Besides understanding the movement you must consider the distance, because if you were within wide distance, even though your adversary moved his weapons or body, provided he did not move his foot there would be no certainty of being able to hit him, even if he were uncovered, for, if his foot were firm, he could break ground, so that your sword would not reach, and you would be in danger. Therefore it would be better to take advantage of his movement to approach within close distance so as to hit with certainty at his first movement with weapons, foot or body, or with both foot and weapons. All these are ''times'' favourable for a hit in an uncovered part. The success would be even greater, when the adversary offers the ''time'' unawares, provided he is not retreating. To be certain of success you must be in counter-position, since, if your adversary has moved first, it is clear that he will not be able to parry and hit except in two ''times'', so that the stroke will be finished before he has parried, and you will be able to break ground before he hits. It is also clear that he will be unable to break ground, as he might have done if he had remained steady. It is sometimes good to beat the adversary's sword within this distance, even if he does not move his foot, for the reason that, if he offers a ''time'' unawares, he will not expect it, as he has not realised that he has given an opportunity of being hit, and therefore he has had time neither to parry nor to break ground.</p> | <p>A movement made by the adversary within distance is called a ''time''. For whatever is done out of distance can only be called either a movement or a change of front. ''Time'' then means an opportunity to hit or win some advantage over the adversary. This movement is given the name of ''time'' among the movements of fencing in order to convey the idea that at a given point of time it is the only possible movement. When the adversary moves, if you perceive an exposed part and are ready to hit in that part, the adversary will certainly be hit if within distance. For there cannot be two changes in one ''time'', and therefore you must take care that the ''time'' in which you wish to hit is not longer than the ''time'' offered by the adversary. In such a case he would have a chance to parry before your point arrived, and you would be in danger; whereas, if you understand the movement, you would succeed. This is called a ''time''-thrust. Besides understanding the movement you must consider the distance, because if you were within wide distance, even though your adversary moved his weapons or body, provided he did not move his foot there would be no certainty of being able to hit him, even if he were uncovered, for, if his foot were firm, he could break ground, so that your sword would not reach, and you would be in danger. Therefore it would be better to take advantage of his movement to approach within close distance so as to hit with certainty at his first movement with weapons, foot or body, or with both foot and weapons. All these are ''times'' favourable for a hit in an uncovered part. The success would be even greater, when the adversary offers the ''time'' unawares, provided he is not retreating. To be certain of success you must be in counter-position, since, if your adversary has moved first, it is clear that he will not be able to parry and hit except in two ''times'', so that the stroke will be finished before he has parried, and you will be able to break ground before he hits. It is also clear that he will be unable to break ground, as he might have done if he had remained steady. It is sometimes good to beat the adversary's sword within this distance, even if he does not move his foot, for the reason that, if he offers a ''time'' unawares, he will not expect it, as he has not realised that he has given an opportunity of being hit, and therefore he has had time neither to parry nor to break ground.</p> | ||

| − | <p>But you must bear in mind that there are some men who cunningly offer a ''time'', that you may attempt a hit, and at the same time they parry and hit. This is called a ''counter-time''. Whenever you are hit or make a hit at the moment when your adversary is extended to hit, it is called a hit in ''counter | + | <p>But you must bear in mind that there are some men who cunningly offer a ''time'', that you may attempt a hit, and at the same time they parry and hit. This is called a ''counter-time''. Whenever you are hit or make a hit at the moment when your adversary is extended to hit, it is called a hit in ''counter time''. Similarly it sometimes happens that both are hit at the same moment; this is because one of them has not timed the ''counter-time'' well, or that in offering the ''time'' he was too close, or that he has made too large a movement. To avoid the danger of this ''counter-time'', you must realise before you make your movement, whether it is so great, that you could approach nearer, and also whether your adversary has moved with the intention of enticing you to hit. In that case you should either not proceed, or you should carry your sword towards the line uncovered by the adversary, and when he moves to make the ''counter-time'', you should then change your line to the part uncovered by his movement, avoiding his point with your body. In this way the deception planned by him will be turned against himself. In truth this science of arms is merely the science of deceiving your adversary with subtlety.</p> |

| − | <p>When therefore you are within close distance you can hit at every movement or change of your adversary, however small, provided he does not break ground; for if in giving a ''time'' he carries hit foot back he so lengthens the ''time'' in which you may hit, that he has a good chance of parrying and hitting; for he being the first to move is also the first to finish the movement. This advantage he would not have if he stood firm, and tried to break ground, while you were making a hit; for your point would arrive before he was out of distance, nor could he parry. Therefore it is not good to be the first to | + | <p>When therefore you are within close distance you can hit at every movement or change of your adversary, however small, provided he does not break ground; for if in giving a ''time'' he carries hit foot back he so lengthens the ''time'' in which you may hit, that he has a good chance of parrying and hitting; for he being the first to move is also the first to finish the movement. This advantage he would not have if he stood firm, and tried to break ground, while you were making a hit; for your point would arrive before he was out of distance, nor could he parry. Therefore it is not good to be the first to move when within close distance, except to retreat. You must also know that within this distance you may often hit without waiting for a ''time'' by the simple advantage of the counter- position, and by understanding how to move in making a hit and how your adversary moves in parrying; also owing to the fact that there are many exposed parts in such a position. Therefore you must contrive to have your point so near the adversary's body, that the time required for your hit is less than the time he needs to defend himself. You must also contrive that your adversary's sword is so far distant from yours, that it is clear when you advance that he can engage only with the ''forte'' for then your sword cannot be thrust aside but will continue on its path to complete the stroke.</p> |

<p>All these rules may be observed equally with the sword and dagger, because the weapons are kept more withdrawn and there are more exposed parts in which a hit may be made, so that they will be most effective. You may easily understand then, how dangerous it is to approach within distance unless your weapons are in conjunction or without some advantage especially within close distance. You have seen too how ''times'' and ''counter-times'' are made, how they may be deceived, and which cannot be deceived.</p> | <p>All these rules may be observed equally with the sword and dagger, because the weapons are kept more withdrawn and there are more exposed parts in which a hit may be made, so that they will be most effective. You may easily understand then, how dangerous it is to approach within distance unless your weapons are in conjunction or without some advantage especially within close distance. You have seen too how ''times'' and ''counter-times'' are made, how they may be deceived, and which cannot be deceived.</p> | ||

| Line 301: | Line 303: | ||

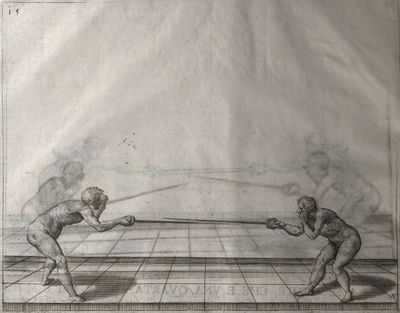

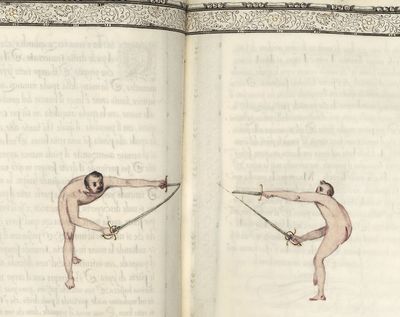

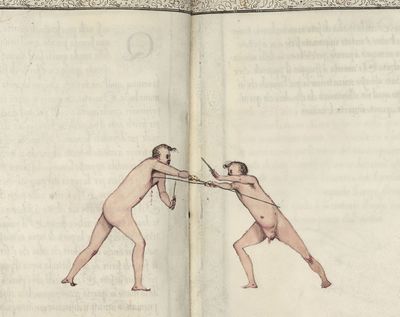

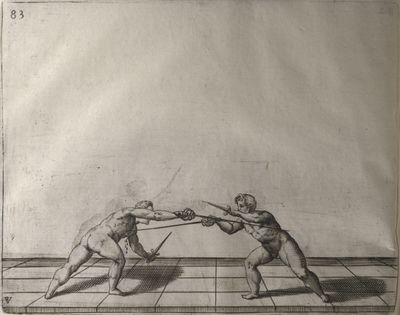

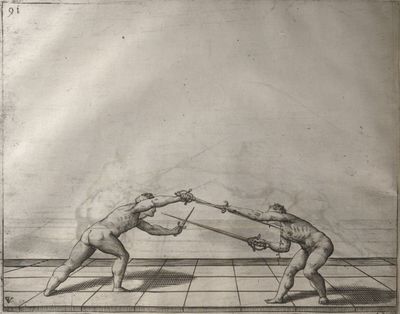

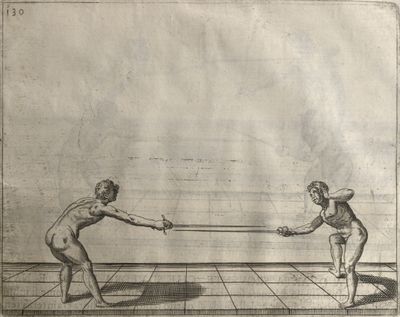

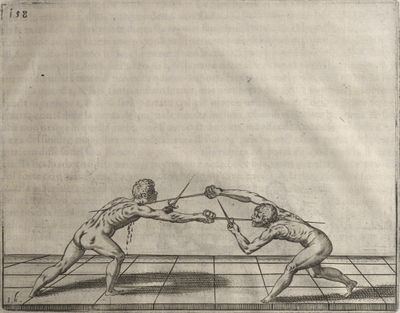

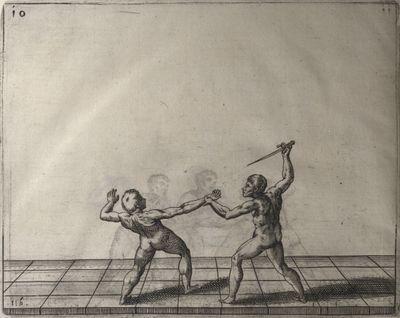

| <p>[11] '''What is "disengagement, counter-disengagement,''' double disengagement, half disengagement, re-engagement, and how and when they should be used.</p> | | <p>[11] '''What is "disengagement, counter-disengagement,''' double disengagement, half disengagement, re-engagement, and how and when they should be used.</p> | ||

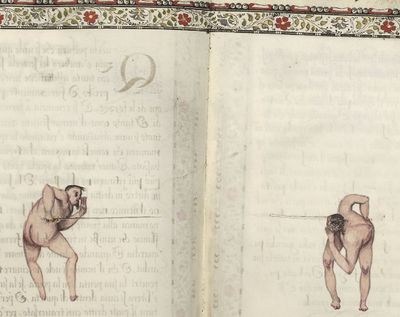

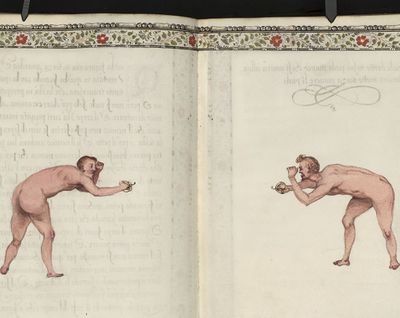

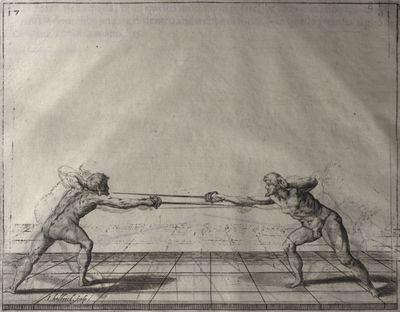

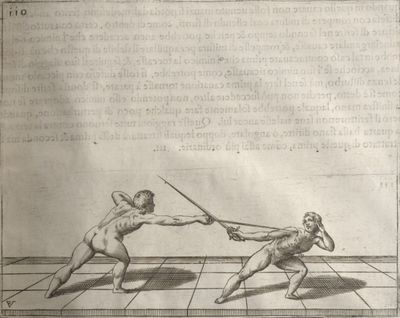

| − | <p>When your adversary attempts to engage your sword or to beat it, and you change from one line to another, before he can beat or engage, you are said to make a disengagement in ''time''. If, while your adversary is disengaging, you follow his movement, which he has begun in order to get the superiority, and let your sword go after his, so that you engage him in the same line as before, that is called a counter-disengagement. If you have disengaged and your adversary has also disengaged and you then deceive his engagement, that is a double disengagement. If, without completing the change from one line to another, you leave your sword under the adversary's, you make a half disengagement. If you disengage and, when your adversary moves to engage or to make a hit, you engage again where you were before, you are said to re-engage - - -.To make a successful disengagement you must bend forward — so that, when the disengagement is completed, the lunge is completed, if you wish to hit, otherwise you will not be in time. If you follow this principle, your adversary will not be able to parry, if you have taken the ''time'', though he may counter-disengage, if that was his intention in seeking to engage. If he had meant simply to get the superiority or to beat he would certainly be hit. If in seeking to engage your sword, the adversary remains steady, then you must disengage in order to free your sword. This gives him an opportunity for a counter-disengagement, for he has moved at the same time as you disengaged. Then to protect yourself you must make a double disengagement and thrust in the same ''time'', in which he has meant to hit you with a counter-disengagement. Some remain steady in seeking to engage in order to make the adversary disengage and so hit him in the straight line, before he has completed the disengagement. In such a case if the adversary, who has begun to disengage, returns to the same line as before, carrying his ''forte'' to your ''faible'' and thrusting on to the body, he will save himself and certainly hit at the moment you meant to hit. The half disengagement is used when you are in doubt that the adversary may pass to your body, before you have completed,[!] the disengagement, since your point would be out of presence and could not hit. Therefore you make a half disengagement to save time, and remain below the adversary's sword in order to hit, removing your body out of presence, as we shall explain in its place. Such a half disengagement is not always used in the first passes, but more often in the second and third movements, as the distance is shortened. The effects produced by these disengagements will be seen in the plates.</p> | + | <p>When your adversary attempts to engage your sword or to beat it, and you change from one line to another, before he can beat or engage, you are said to make a disengagement in ''time''. If, while your adversary is disengaging, you follow his movement, which he has begun in order to get the superiority, and let your sword go after his, so that you engage him in the same line as before, that is called a counter-disengagement. If you have disengaged and your adversary has also disengaged and you then deceive his engagement, that is a double disengagement. If, without completing the change from one line to another, you leave your sword under the adversary's, you make a half disengagement. If you disengage and, when your adversary moves to engage or to make a hit, you engage again where you were before, you are said to re-engage - - -. To make a successful disengagement you must bend forward — so that, when the disengagement is completed, the lunge is completed, if you wish to hit, otherwise you will not be in time. If you follow this principle, your adversary will not be able to parry, if you have taken the ''time'', though he may counter-disengage, if that was his intention in seeking to engage. If he had meant simply to get the superiority or to beat he would certainly be hit. If in seeking to engage your sword, the adversary remains steady, then you must disengage in order to free your sword. This gives him an opportunity for a counter-disengagement, for he has moved at the same time as you disengaged. Then to protect yourself you must make a double disengagement and thrust in the same ''time'', in which he has meant to hit you with a counter-disengagement. Some remain steady in seeking to engage in order to make the adversary disengage and so hit him in the straight line, before he has completed the disengagement. In such a case if the adversary, who has begun to disengage, returns to the same line as before, carrying his ''forte'' to your ''faible'' and thrusting on to the body, he will save himself and certainly hit at the moment you meant to hit. The half disengagement is used when you are in doubt that the adversary may pass to your body, before you have completed,[!] the disengagement, since your point would be out of presence and could not hit. Therefore you make a half disengagement to save time, and remain below the adversary's sword in order to hit, removing your body out of presence, as we shall explain in its place. Such a half disengagement is not always used in the first passes, but more often in the second and third movements, as the distance is shortened. The effects produced by these disengagements will be seen in the plates.</p> |

| | | | ||

| {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|23|lbl=15}} | | {{pagetb|Page:Scienza d’Arme (Salvator Fabris) 1606.pdf|23|lbl=15}} | ||

| Line 311: | Line 313: | ||

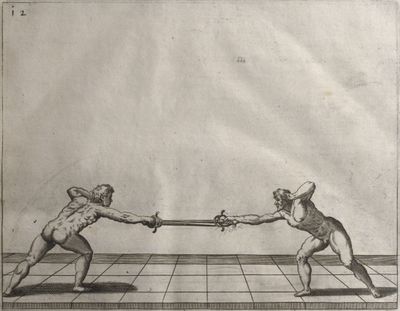

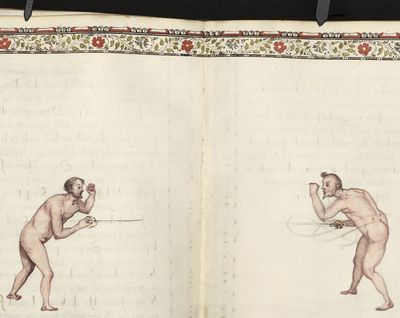

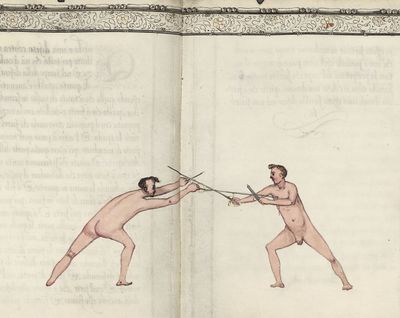

| <p>[12] '''On the feint,''' and why it is so called; in what manner and at what time it should be used.</p> | | <p>[12] '''On the feint,''' and why it is so called; in what manner and at what time it should be used.</p> | ||

| − | <p>When you feign to hit in one line, and while the adversary is defending himself, hit in another, you are said to make a feint. You must understand, which feints are good, and which not. For some make their feints with the feet rather than with the sword, beating the ground as hard as possible, so as to frighten the adversary, and while he is intimidated hit him. This method might sometimes succeed in the hall, particularly if the floor is of wood, so as to re-echo. This might sometimes cause the adversary to waver. But on ground which does not ring, it would not have the same effect. It is of little or no value in either place against those who understand the art. For if this stamping is done out of distance, there is no need to waver, since his sword cannot reach | + | <p>When you feign to hit in one line, and while the adversary is defending himself, hit in another, you are said to make a feint. You must understand, which feints are good, and which not. For some make their feints with the feet rather than with the sword, beating the ground as hard as possible, so as to frighten the adversary, and while he is intimidated hit him. This method might sometimes succeed in the hall, particularly if the floor is of wood, so as to re-echo. This might sometimes cause the adversary to waver. But on ground which does not ring, it would not have the same effect. It is of little or no value in either place against those who understand the art. For if this stamping is done out of distance, there is no need to waver, since his sword cannot reach.</p> |

| − | <p>Others make the faint with the body and the sword, but do not extend the sword much, so that the adversary may not engage it in his parry, and they may then hit him when his weapons have dropped, or when he raises them again violently after failing to engage. This method may succeed with a timid or ill-trained adversary. But as the sword does not come forward, you know that it cannot hit; therefore you should not move, except to attack at the moment of his feint; or you should make a feint of hitting, so that in his doubt that you have taken the ''time'' he will rush to the defence, when you will have ample opportunity to hit. This will be a hit with a counter-feint, and he who made the first feint will | + | <p>If it is done within distance, it gives you a chance to hit in the exposed part at that very moment, or to make a feint of hitting in that part and hit in the other part, which he exposes in his attempt to defend himself; for he can never defend one part without uncovering another. Thus one who stamps with his foot will be deceived through not observing that in seeking to provoke his adversary to offer a ''time'', he has himself offered a ''time''. The adversary, being steady, can better judge the movements than the one who has moved. Thus feints more often succees[!] if made when the adversary is moving than when he is steady.</p> |

| + | |||

| + | <p>Others make the faint with the body and the sword, but do not extend the sword much, so that the adversary may not engage it in his parry, and they may then hit him when his weapons have dropped, or when he raises them again violently after failing to engage. This method may succeed with a timid or ill-trained adversary. But as the sword does not come forward, you know that it cannot hit; therefore you should not move, except to attack at the moment of his feint; or you should make a feint of hitting, so that in his doubt that you have taken the ''time'' he will rush to the defence, when you will have ample opportunity to hit. This will be a hit with a counter-feint, and he who made the first feint will be deceived.</p> | ||

<p>There are others who in feinting carry the sword forward, and, when the adversary tries to parry, draw it back to return it with a rush. Neither is this method good, but rather worse than the other; for when you should make only one movement with the sword you make three contrary ones, one in carrying it forward, the second in withdrawing it and the third, greater than all, in thrusting with violence. You fall to grasp that your movement is so slow, that, if your adversary moves at the first movement of the feint, he will hit before your sword has completed the withdrawal, and will easily save himself before you can proceed to hit.</p> | <p>There are others who in feinting carry the sword forward, and, when the adversary tries to parry, draw it back to return it with a rush. Neither is this method good, but rather worse than the other; for when you should make only one movement with the sword you make three contrary ones, one in carrying it forward, the second in withdrawing it and the third, greater than all, in thrusting with violence. You fall to grasp that your movement is so slow, that, if your adversary moves at the first movement of the feint, he will hit before your sword has completed the withdrawal, and will easily save himself before you can proceed to hit.</p> | ||

| Line 332: | Line 336: | ||

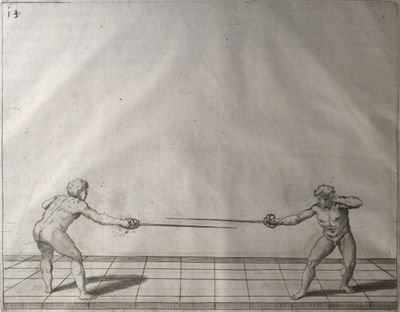

| <p>[13] '''On lunging and passing'''.</p> | | <p>[13] '''On lunging and passing'''.</p> | ||

| − | <p>To lunge is to hit by carrying the right foot forward towards the adversary and withdrawing it immediately after hitting, or to hit by a movement of the body, keeping the foot firm. To pass is to carry both the feet on right to the adversary's body. It is necessary to understand the lunge, as it is in the most common use, and therefore must be the first thing to practise, in order that you may learn how to advance the point accurately and to the full extent. The hand is fallible and may hit in a spot different from the one intended, according to the amount of the distance. This depends on the changed position of the wrist as it is extended more or less, causing the sword to fall short or go too far, in accordance with the angle of its direction | + | <p>To lunge is to hit by carrying the right foot forward towards the adversary and withdrawing it immediately after hitting, or to hit by a movement of the body, keeping the foot firm. To pass is to carry both the feet on right to the adversary's body. It is necessary to understand the lunge, as it is in the most common use, and therefore must be the first thing to practise, in order that you may learn how to advance the point accurately and to the full extent. The hand is fallible and may hit in a spot different from the one intended, according to the amount of the distance. This depends on the changed position of the wrist as it is extended more or less, causing the sword to fall short or go too far, in accordance with the angle of its direction. In order to learn how to drive the sword sufficiently far you must accompany it by bending the body forward and recovering it quickly after hitting, in order to save yourself from danger. Practice is required to learn how to carry yourself, and when you can do this well you will find it very profitable, for it will make the body agile, the feet quick, and give you judgment of distances. You will then certainly make a lunge longer than before practice.</p> |