|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

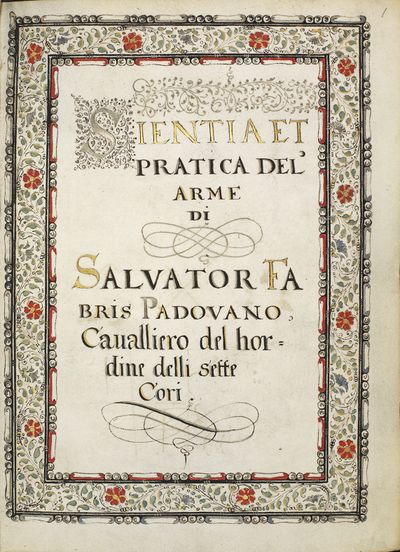

Difference between revisions of "Salvator Fabris"

| Line 2,207: | Line 2,207: | ||

<p>The first method which we discussed on this subject of attacking with resolution is good, because you begin to acquire the advantage so far out of distance, that the adversary cannot hit. Yet it appears that the danger is revealed to the adversary too soon, so that he has good opportunity to change his line in order to disorder you, and ample time in which to employ various devices for his protection. The second method also is good, since it forms a secure guard with only one exposed part and that part so near the sword hand that it cannot be reached without passing your ''forte''. With this guard also your sword, as we have shown, is kept so free, that few disengagements are needed. If it were not in other respects so restricted, and you were not under the constraint of keeping your own steady it would be better than the first. Nevertheless considering the imperfections of these two methods, and particularly that defending oneself when the adversary cannot attack is a loss of time and a disadvantage, since it reveals your intentions to him and gives him a chance of finding a remedy, we have sought for another way of proceeding, a third method, which reveals nothing to the adversary until his body is in danger. This method when properly executed, will hit with such swiftness that the adversary not only has no time for so many changes, but can barely parry the first onslaught.</p> | <p>The first method which we discussed on this subject of attacking with resolution is good, because you begin to acquire the advantage so far out of distance, that the adversary cannot hit. Yet it appears that the danger is revealed to the adversary too soon, so that he has good opportunity to change his line in order to disorder you, and ample time in which to employ various devices for his protection. The second method also is good, since it forms a secure guard with only one exposed part and that part so near the sword hand that it cannot be reached without passing your ''forte''. With this guard also your sword, as we have shown, is kept so free, that few disengagements are needed. If it were not in other respects so restricted, and you were not under the constraint of keeping your own steady it would be better than the first. Nevertheless considering the imperfections of these two methods, and particularly that defending oneself when the adversary cannot attack is a loss of time and a disadvantage, since it reveals your intentions to him and gives him a chance of finding a remedy, we have sought for another way of proceeding, a third method, which reveals nothing to the adversary until his body is in danger. This method when properly executed, will hit with such swiftness that the adversary not only has no time for so many changes, but can barely parry the first onslaught.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The foundation of this method is the certainty that the adversary cannot hit before you are within distance; therefore there is no necessity to defend or to hold your sword steady in any position. You should advance towards the outside, until your feet are within distance; it is of no importance which foot is first. The time to carry the forte to the adversary's ''faible'' is when lifting the foot to bring it within distance, in order to exclude his sword without stopping; you should run along his blade in order to hit with your sword, feet and body in union and without rushing; for if he should then break ground he would have time not only to parry but to hit also. By advancing in union you can change in time, as you should do if on the inside when he parries; you should in that case change from ''tierce'' to ''seconde'', lower the body and continue your advance when you will hit at the moment of his attempted parry; but in turning from ''tierce'' to ''seconde'' you must drop your point under his arm, keeping the hand in the same place and bend the body so as to hit in the right side. If your adversary has succeeded in parrying by breaking ground after you have engaged his sword and advanced to hit, he can no longer bring his point into line as for example he could have done, if you had stopped and made an interval between engaging his sword and advancing, for your plan would have been too slow. Similarly if you had [rushed]<ref>This word can't be read on the photos I have. It's a 6-letter word that seems to end in "s?ed". The Italian word means to move or advance, and Tom Leoni translates it as "fling".</ref> your body or sword forward or hurried your steps, you would have been at a disadvantage, since you could not have turned a second plan, but rather would have been in danger of being hit. | + | <p>The foundation of this method is the certainty that the adversary cannot hit before you are within distance; therefore there is no necessity to defend or to hold your sword steady in any position. You should advance towards the outside, until your feet are within distance; it is of no importance which foot is first. The time to carry the forte to the adversary's ''faible'' is when lifting the foot to bring it within distance, in order to exclude his sword without stopping; you should run along his blade in order to hit with your sword, feet and body in union and without rushing; for if he should then break ground he would have time not only to parry but to hit also. By advancing in union you can change in time, as you should do if on the inside when he parries; you should in that case change from ''tierce'' to ''seconde'', lower the body and continue your advance when you will hit at the moment of his attempted parry; but in turning from ''tierce'' to ''seconde'' you must drop your point under his arm, keeping the hand in the same place and bend the body so as to hit in the right side. If your adversary has succeeded in parrying by breaking ground after you have engaged his sword and advanced to hit, he can no longer bring his point into line as for example he could have done, if you had stopped and made an interval between engaging his sword and advancing, for your plan would have been too slow. Similarly if you had [rushed]<ref>This word can't be read on the photos I have. It's a 6-letter word that seems to end in "s?ed". The Italian word means to move or advance, and Tom Leoni translates it as "fling". ~ Michael Chidester</ref> your body or sword forward or hurried your steps, you would have been at a disadvantage, since you could not have turned a second plan, but rather would have been in danger of being hit.</p> |

<p>You should adopt the same method of advancing with resolution if your adversary on your first approach to engage his sword parries without breaking ground, since before he forced your sword you could hit and pass. But if when making this parry he breaks ground, it is then better to disengage, before he touches your sword; here is the difficulty, because if you move your sword on first seeking his, you cannot disengage in time. Therefore you must advance in such a way that the movement of disengaging shall not be opposite to your other movement; if by accident your hand fell, you could not lift it again in time, if your adversary advanced to meet your sword. But if your point is carried with such ease that you can abandon your first plan and adopt another according to the occasion and with the necessary skill the method will be very deceptive, since, when within distance, you engage your adversary's sword and while he expects to meet and resist your sword you disengage and advance the other foot, so that he can no longer return into line nor do anything but hit below by a half-disengagement; in that case you have only a small movement of the point to make and to lower the body to the line in which his sword is directed; you will continue on your course, exclude his sword and certainly hit. But if the adversary, while you are attacking his sword disengages or advances, rather than breaks ground, he will be hit before he has finished the disengage. If he disengages and breaks ground in order to find your ''faible'' again, then you should counter-disengage and advance, when you will hit at the same time; this will be easier and shorter than seeking his sword and disengaging, before he touches your sword. If the adversary changes his guard, when he breaks ground, raising or lowering his point or withdrawing it, in every case you should continue your advance and again seek his sword as soon as you are within distance, but in such a manner that in whatever way he tries to hit, you can keep on your course, parrying and hitting together. From the position and the distance between your adversary and yourself you will understand what he can do in defence and attack, how he can disturn and impede your sword and how to guard against it. For if you do not foresee what may heppen[!], the opportunity passes so quickly that there is no time to form a plan.</p> | <p>You should adopt the same method of advancing with resolution if your adversary on your first approach to engage his sword parries without breaking ground, since before he forced your sword you could hit and pass. But if when making this parry he breaks ground, it is then better to disengage, before he touches your sword; here is the difficulty, because if you move your sword on first seeking his, you cannot disengage in time. Therefore you must advance in such a way that the movement of disengaging shall not be opposite to your other movement; if by accident your hand fell, you could not lift it again in time, if your adversary advanced to meet your sword. But if your point is carried with such ease that you can abandon your first plan and adopt another according to the occasion and with the necessary skill the method will be very deceptive, since, when within distance, you engage your adversary's sword and while he expects to meet and resist your sword you disengage and advance the other foot, so that he can no longer return into line nor do anything but hit below by a half-disengagement; in that case you have only a small movement of the point to make and to lower the body to the line in which his sword is directed; you will continue on your course, exclude his sword and certainly hit. But if the adversary, while you are attacking his sword disengages or advances, rather than breaks ground, he will be hit before he has finished the disengage. If he disengages and breaks ground in order to find your ''faible'' again, then you should counter-disengage and advance, when you will hit at the same time; this will be easier and shorter than seeking his sword and disengaging, before he touches your sword. If the adversary changes his guard, when he breaks ground, raising or lowering his point or withdrawing it, in every case you should continue your advance and again seek his sword as soon as you are within distance, but in such a manner that in whatever way he tries to hit, you can keep on your course, parrying and hitting together. From the position and the distance between your adversary and yourself you will understand what he can do in defence and attack, how he can disturn and impede your sword and how to guard against it. For if you do not foresee what may heppen[!], the opportunity passes so quickly that there is no time to form a plan.</p> | ||

Revision as of 04:23, 5 June 2022

| Salvator Fabris | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1544 Padua, Italy |

| Died | 11 Nov 1618 (aged 74) Padua, Italy |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Italian |

| Alma mater | University of Padua (?) |

| Patron |

|

| Influenced | |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Italian |

| Notable work(s) | Scienza d’Arme (1601-06) |

| Manuscript(s) |

MS 17 (1600-20)

|

| Translations | |

Salvator Fabris (Salvador Fabbri, Salvator Fabriz, Fabrice; 1544-1618) was a 16th – 17th century Italian knight and fencing master. He was born in or around Padua, Italy in 1544, and although little is known about his early years, he seems to have studied fencing from a young age and possibly attended the prestigious University of Padua.[citation needed] The French master Henry de Sainct Didier recounts a meeting with an Italian fencer named "Fabrice" during the course of preparing his treatise (completed in 1573) in which they debated fencing theory, potentially placing Fabris in France in the early 1570s.[1] In the 1580s, Fabris corresponded with Christian Barnekow, a Danish nobleman with ties to the royal court as well as an alumnus of the university.[2] It seems likely that Fabris traveled a great deal during the 1570s and 80s, spending time in France, Germany, Spain, and possibly other regions before returning to teach at his alma mater.[citation needed]

It is unclear if Fabris himself was of noble birth, but at some point he seems to have earned a knighthood. In fact, he is described in his treatise as Supremus Eques ("Supreme Knight") of the Order of the Seven Hearts. In Johann Joachim Hynitzsch's introduction to the 1676 edition, he identifies Fabris as a Colonel of the Order.[3] It seems therefore that he was not only a knight of the Order of the Seven Hearts, but rose to a high rank and perhaps even overall leadership.

Fabris' whereabouts in the 1590s are uncertain, but there are rumors. In 1594, he may have been hired by King Sigismund of Poland to assassinate his uncle Karl, a Swedish duke and competitor for the Swedish crown. According to the story, Fabris participated in a sword dance (or possibly a dramatic play) with a sharp sword and was to slay Karl during the performance when the audience was distracted. (The duke was warned and avoided the event, saving his life.)[4] In ca. 1599, Fabris may have been invited to England by noted playwright William Shakespeare to choreograph the fight scenes in his premier of Hamlet.[5][2] He also presumably spent considerable time in the 1590s developing the fencing manual that would guarantee his lasting fame.

What is certain is that by 1598, Fabris had left his position at the University of Padua and was attached to the court of Johan Frederik, the young duke of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorp. He continued in the duke's service until 1601, and as a parting gift prepared a lavishly-illustrated, three-volume manuscript of his treatise entitled Scientia e Prattica dell'Arme (GI.kgl.Saml.1868 4040).[2]

In 1601, Fabris was hired as chief rapier instructor to the court of Christianus Ⅳ, King of Denmark and Duke Johan Frederik's cousin. He ultimately served in the royal court for five years; toward the end of his tenure and at the king's insistence, he published his opus under the title Sienza e Pratica d’Arme ("Science and Practice of Arms") or De lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme ("On Defense, or the Science of Arms"). Christianus funded this first edition and placed his court artist, Jan van Halbeeck, at Fabris' disposal to illustrate it; it was ultimately published in Copenhagen on 25 September 1606.[2]

Soon after the text was published, and perhaps feeling his 62 years, Fabris asked to be released from his six-year contract with the king so that he might return home. He traveled through northern Germany and was in Paris, France, in 1608. Ultimately, he received a position at the University of Padua and there passed his final years. He died of a fever on 11 November 1618 at the age of 74, and the town of Padua declared an official day of mourning in his honor. In 1676, the town of Padua erected a statue of the master in the Chiesa del Santo.

The importance of Fabris' work can hardly be overstated. Versions of his treatise were reprinted for over a hundred years, and translated into German at least four times as well as French and Latin. He is almost universally praised by later masters and fencing historians, and through the influence of his students and their students (most notably Hans Wilhelm Schöffer), he became the dominant figure in German fencing throughout the 17th century and into the 18th.

Contents

Treatise

Preface and Dedication

Illustrations |

Illustrations |

Draft Translation (from the archetype) |

Prototype (1601) |

Archetype (1606) [edit] |

German Translation (1677) [edit] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[1] Fencing, or the Science of Arms by Salvator Fabris. |

[I] |

[I] SCIENZA E PRATICA D' ARME DI SALVATORE FABRIS, CAPE DELL’ ORDINE DEI SETTE CUORI. ·/· Herrn Salvatore Fabris Obristen des Ritter-Ordens der Sieben Herzen, verteutschte Italiänische Fecht Kunst. LEIPZIG, Verlegts Erasmus Hynitzsch. Druckts Michael Vogt. Im Jahr 1677. | |||

[2] |

[III] DE LO SCHERMO OVERO SCIENZA D’ARME DI SALVATOR FABRIS CAPO dell’ ordine dei sesse CORI

|

||||

[3] |

[V] VANDALORVM GOTHORVMQVÆ REX CHRISTIANVS IIII D G DANIÆ NORVEGIÆ REGNA FIRMAT PIETAS |

||||

[4] To His Serene Majesty, the most Powerful Christian IV., King of Denmark, Norway, Gothland and Vandalia, Duke of Schleswig Holstein, Stormarn and Ditmarsch, Count of Oldenburg and Delmenhorst, &c. I am confident that all who read this work of mine will recognise that the many benefits received from your Serene Highness are the cause, which has urged and impelled me to publish to the world these my labours. I have wished also to help professors of the science of arms by showing them those instructions and rules, which after long use and continual practice and from observing the errors of others I have found to be good. I hope then that a work based on such principles will find merit, especially as it is under the protection of your Serene Highness - a work as worthy by reason of the excellence of its subject as it is glorious through the approval of your high judgment. To you, therefore, my benefactor, my king and a prince of incomparable valour as much in civil government as in the practice of arms, a true hero of our times, I have dared to dedicate my work; for since its inception is due to you, I am bringing it forth to the sight of men under the same protection. I know moreover how useful to the world and necessary to good men this art is, bringing honour to anyone who practises it aright either in the defence of his prince, his country, the laws, his life or his honour. Will your Serene Majesty therefore deign to receive into your favour not only the work, but the devotion with which, your humble and obedient servant, dedicate it. Meantime I will pray the Divine grace that long life may be granted you for the well-being of your blessed subjects and the good of the world, and that by grace you may obtain salvation in the world to come. Your Serene Majesty's most humble and devoted Servant, Salvatore Fabris |

[VII] ALLA SERma: Mtà: DEL POTENT ISSIMO CHRISTIANO IV. RE DI DANIMARCA, NORVEGGIA, GOTTIA, ET VANDALIA, DVCA DI SLESVIK, HOLSTEIN, STORMARN ET DITMARSCHEN, CONTE DI OLDEMBVRGH, ET DELMENHORST &c. CREDO SICVRAMENTE CHE DA CHIVNQVE leggerà questa mia opera si conoscerà la multitudine de benefficii riceuuti dalla Ser:ma M.ta V. essere stata quella, che mi hà eccitato, & spinto à publicare al mondo queste mie fatiche desideroso anco di giouare à Professori della scienza d’armi, mostrando loro quelli auertimenti, & regole, che per longo uso io hò conosciuto buone tratte da una continouata essercittatiòne, & dalla uista, & osseruatione delli errori altrui coiquali fondamenti & raggioni spero, che l’ opera Sarà lodata, maßimamente sattola protetione della Serenißima M.ta V. opera per l’eccellentia della materia tanto degna, quanto risplendente per essere aprobata dall’ altißimo giuditio di lei, allaquale però, come à Re sommo mio beneffattore, & Prencipe di incomparabile ualore tanto nel gouerno ciuile quanto nel maneggio dell’ armi, & uero Heroe de tempi nostri, hò preso animo de dedicarla, & come parto prodotto in uirtù sua mandarla nel conspetto delli huomini sotto la medesima sua prottetione, sapendo anco per altro quanto utile sia à lo stesso Mondo questo arte neccessaria à buoni, & honoreuole à chi giustamente l’ essercitta, ò in diffesa del Prencipe, ò della Patria, ò delle leggi, ò della vita & fama propria. Degnisi dunque la stessa Majesta S. Serenißima di riceuere in grado non solamente l’ opera, mà la deuotione con che io humilißimo , & obligatißimo seruitore suo gliela consacro, che in tanto attenderò à pregare la Diuina bontà che conceda à lei longhi, & felici anni de uita per benefficio de suoi fortunatißimi popoli, & buoni del Mondo, & à media gratia di poterla seruire in altro. Di Copenhagen adi 20. Aprile 1606.

|

||||

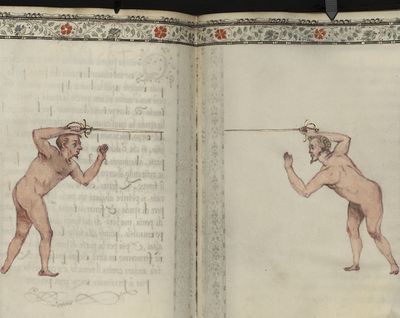

[5] To the Reader. Marvel not, Reader, if you see a man of the sword, unaccustomed to the schools or the circles of literary men, presuming to write and print books; rather rejoice at seeing the science of arms and the knowledge of the sword reduced to rules and precepts, and like the other arts to a teachable form, wherein the curious and eager men of arms may learn by turning the leaves. More than others should men of arms rejoice, in that men of learning and science have never translated their arts from theory to practice, as now a man of arms has brought his from practice to true theory. To him is owed much greater faith, because he has had a thousand experiences in his own case and in that of others of what he has written. Here then, Reader, is my book on the science of arms, illustrated with plates suitable to each case; to these plates and dumb images, as it were, our words give life; the plates will demonstrate and our words will interpret the effects and principles treated of in the book. We have written in our mother tongue, Italian, dispensing with flowers of rhetoric and elegance of style, not thinking shame to acknowledge our little learning, or, following the example of a very famous captain of our age, to declare that in our youth we could not wield both the sword and the pen. We believe however that we have dealt adequately with what is required in this art and have tried as far as in us lay to avoid obscurity and prolixity, although in so subtle a subject it is difficult to preserve the necessary brevity. We have shunned the use of geometrical terms, although swordsmanship has its foundations more in geometry than in any other science. Simply and as naturally as possible we have tried to bring the art within the capacity of all. For what we have written and demonstrated we require no praise or reward, for it was never our intention to publish it to the world; but if in it there is anything worthy of merit, it should be ascribed to his Serene Majesty our King, through whom we have written this work, and at whose command this book is brought to the light of day. We will not speak of the nobility and excellence of this profession, for it is in itself so glorious and resplendent that it has no need of our words, nor is there any man so ignorant as not to know, that by its[!] kingdoms are defended, religion spread abroad, injustice avenged, peace and the prosperity of nations established. We wish only to say that after acquiring this inestimable knowledge a man should not become puffed up nor use it violently to the detriment of others, but always with moderation and justice in all cases, thinking that the last victory of all rests not in his own hand, but in the just will of God; and may He grant us abundance of his saving grace. |

[VIII] A LETTORI. NON TI MARA VIGLIARE, O LETTORE, SE tu uedrai un huomo di spada non assueto nelle scole, ne frà i circoli de litterati, ilquale presuma di scriuire, & stampare libri, mà più tosto rallegrati di uedere la scienza dell’ armi, & peritia della spada ridotta sotto regole, & precetti, & si come l’ altre arti in forma disciplinabile, ouepotranno i curiosi, & solecitti armigeri anco col uoltare delle carte apprendere amaestramenti, & tanto più delli altri douranno eßi armigeri rallegrarsi quanto, che dalli huomini togati, & scientifici, per nobile concorrenza di laude suoi antichi auerssarii, non sono mai state trasportate le arti loro dalla Theorica alla pratica, si come hora dall’ armigero si conuerte l’ atto pratico in uera theorica, alquale si dee tanta maggior fede, quanto, che diciò che hà egli scritto ne hà prima uedute mille esperienze in se medesmo, & in altrui. Eccoti dunque ò lettore il presente libro di scienza d’armi adornato di figure fecondo la proposta de casi, à loro, come imagini mute danno fiato, & animale nostre parole, quelle saranno demostratrici, & queste interprettatrici detti effetti, & raggioni che in esso libro si trattano, ilquale libro noi habbiamo scritto in lingua italiana materna, lontani dà i fiori rethorici, & da certa elliganza di dire, non uergognandoci confessare la nostra poca eruditione, & con l’ esempio di un famosißimo capitano del nostro secolo dire di non hauere potuto in giouentù nostra tenere nella medisima mano la spada, il libro, crediamo bene di hauere, intorno à quello, che in questa profeßione si richiede, sufficientemente trattato, essendoci sforzati in quanto habbiamo potuto di fuggire l’ oscurità, & la prolißita, se bene in materia tanto sottile, difficile cosa è lo seruare la debbita breuità. Habbiamo lasciato l’uso delle parole geometriche, ancorche la detta profeßone habbia li suoi fondamenti piu nella Geometrhia, che altroue, & con un modo facile, & più tosto naturale, che artifficioso habbiamo procurato di renderla capace ad ogniuno, & di quello, che noi habbiamo scritto, ò dimostrato non ricercamo lode, ne preggto alcuno, non essendo mai stato nostro pensiero di publicarlo al mondo, mà se in esso ui è pure cosa degna di preggio tutto si rifferisca alla Serenißima Majesta del Rè nostro signore, per comandamento dil quale il detto libro uiene nella luce del mondo, & anco in uirtu del quale potiamo dire, d’ hauerlo scritto. Lasciamo di discorrere della nobiltà, & eccellenza dideta profeßione, che per essere da se stessa tanto chiara, esplendente non hà bisogno di nostre parole, ne ui è alcuno tanto ignorante, che non sappia, che con questa si diffendono i Regni, si dilattano, le Religgioni, si uendicano le ingiustitie, & si stabilisse la pace, & felicità de’ popoli. Solo uogliamo ricordare, che doppo l’ a quisto di cosi preggiata uirtù non dee l’huomo insuperbirsi, & usarla uiolentemente neldanno d’altri, mà più tosto con moderatione, & giustitia seruirsene in tutti i casi, douendo aspettare il fine di qualunque sua uittoria, non dalla mano di se stesso, mà si bene dalla giustißima uolontà di Dio, ilquale ci conceda coppie delle sue sante gratie. |

Book 1

First Part - On the Basics of the Sword Alone

Illustrations |

Illustrations |

Draft Translation (from the archetype) |

Prototype (1601) |

Archetype (1606) [edit] |

German Translation (1677) [edit] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

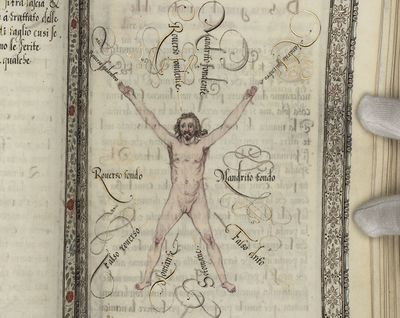

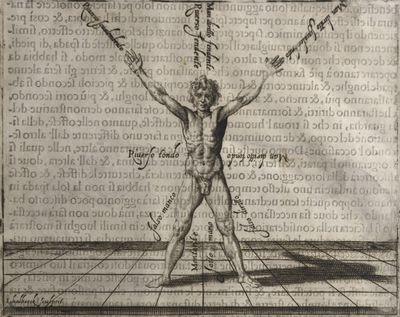

[1] General discourse of the first book. The principles of the sword alone. In opening our promised work we shall begin with the sword alone, for on the knowledge of the sword depend the principles of all other arms. Many rules will be given which may serve excellently for the sword accompanied by the dagger or any other arm. He who can use the sword alone well will easily learn to use it in conjunction with other arms. You must know then that the rules of the sword are founded on four guards in which are formed all the positions and counter positions. From them arise the times, counter-times, disengagements, counter-disengagements, double disengagements, half disengagements, and re-engagements; nor in short can anything be done in attack or defence which does not partake of the nature of one of these four guards. They are differently formed, as will be seen in the accompanying plates. These we have introduced in order that you may recognise with what variations of position of the sword, feet and body, they are made. We shall describe the nature of each guard in its place and the plates will show the results which may arise from them. The discourses will be such that you will easily see when to apply the various rules, and how to the best advantage you must approach your adversary in order to come within presence. Though one who understands the art may approach as he pleases, since in whatever position he is he will succeed by his knowledge of distances, weak and strong positions, exposed and unexposed parts. Nevertheless it is certain that one position is better than another, and a man may approach with more security when he parries his arms in the proper manner. When within distance he must proceed in various ways, according to the changes made and the opportunities offered by his adversary, and according to the distance in which he finds himself. The distances are two, and what is good in the one is not so in the other. These distances control the whole attack and defence, as we shall explain. First we shall describe the four principal guards, why they are called, prime, seconde, tierce and quarte, and the origin of these names. Then we shall treat of the divisions of the sword, then of counterpositions, distances, and some other matters which we consider necessary and useful to the good student of this art. |

[1] DISCORSO GENERALE DEL PRIMO LIBRO Sopra li fondamenti detta spada sola. Cap. 1. DOUENDO NOI DARE PRINCIPIO ALL’ OPERA promessa cominciaremo dalla spada sola come quella, dalla cognitione della quale dependono anco li fondamenti di tutte l’altre armi, & percio s’intenderanno molte raggioni, lequali potranno ottimamente seruire, ancorche sia accompagnata dal pugnale, ouero altra arma, & chi saprà bene oprare quella fola facilmẽte impararà di oprarla non meno accompagnata. Per tanto si dee sapere, che le raggio ni di essa hanno il suo fondamẽto sopra quattro guardie, con che si formano tutte le posture, & contra posture, & da esse nascono li tempi, & contratempi, cauationi, contracauationi, ricauationi meggie cauationi, & comettere di spada, ne si può in somma fare cosa alcuna per diffesa, ouero per offesa, che non si faccia con la natura di una di dette quattro, lequali uengono formate diuersamente, come si uedrà per le seguenti figure, poste da noi, acciò si conosca con quanta uarietà di siti, e prospettiue di spada, di piedi, & di corpo si facciano, & à suoi luoghi si discorrerà sopra la natura di ciascuna, & si metteranno anco in pittura li effetti, che da loro possono nascere, & i discorsi saranno tali, che ageuolmente si potrà comprendere, quando sia tempo ualersi hor dell’una hor dell’ altra raggione, & conche modo per maggiore uantaggio si debba andare contra il nimico per fermarsi in presenza, ancorche da uno che habbia scienza si possa andare come li piaccia, perche trouandosi in qualũque sito farà nascere buono effetto per la cognitione delle misure, debili, e forti, coperti, & scoperti, Nondimeno ècosa certa,che un sito è migliore dell’ altro, & più srcuramẽte Può l’huomo auicinarsi nelle distanze, quando, ché porta l’armi in debbito modo, doue poi gionto, hà da operare diuersamente, secondo le mutationi & opurtunità date dall’ auerssario, & secondo le distanze, inche si trouarà, lequali sono due, & quello, che è buono nell’ una non uale nell’ altra, & lequali distanze sono patrone di tutte le offese, & diffese, come si mostrarà, doppo, che fi Sarà dichiarato qualisiano le quattro principali guardie, & perche chiamate prima, seconda, terza e quarta & la deriuatione de nomi tali, il che fatto, si trattarà della diuisione della spada epoi delle contra posture, & delle misure, & di alcune altre cose gindicate da noi necessarie, & utili al buono osseruatore[6] di quest’ arte. |

||||

[2] Description of the four principal guards and the origin of their names. The four guards arise from the four faces of the hand and the sword, that is to say of the two edges and the two surfaces; and these produce four different positions. Prime is that position which the hand takes in drawing the sword from the scabbard, when the point is turned towards the adversary - all the guards especially with the sword alone must be formed with the point so directed. When the hand is turned slightly upward we have seconde, and tierce when the hand is in its natural position turned neither up nor down. When the inside of the hand is turned upwards we have quarte. The hand in turning can take these four positions only, and being in prime cannot go to quarte without passing through seconde and tierce; so the name quarte is given to the last position. Prime is the most suitable position for grasping the sword, although it can be done in seconde or tierce: but with the hand in quarte the sword cannot be drawn from the scabbard. You must know that nothing can be done which does not arise from one of these four positions approximately; we say approximately, because, if you consider, you will find that there is a great distance between one guard and another owing to the width of the surface of the sword and of the hand, so that between prime and seconde there is a mean, where the hand might stop, and similarly between seconde and tierce, and between tierce and quarte. Therefore one might say that there were four legitimate guards and three bastard, since each bastard resembles the two, between which it is formed. But to avoid the confusion of so many terms we shall speak only of the four legitimate guards, which will serve very well for the three bastards also; for the quality of the guard is considered not only from the position of the hand, but also from the direction of the point, wherein lies the force of the guard. Therefore we shall divide the guards into these four only, especially as with the sword there are only four methods of hitting, that is on the inside, on the outside, below and above. The great differences between one guard and another will be explained when we treat of their natures, when we shall consider the various methods of defence, and the changes made in hitting, according to whether they are formed with the sword extended or withdrawn, high or low; we shall then treat of the nature of each one separately. |

DICHIARATIONE DELLE QVATTRO Guardie principali, & donde deriuino linomi di esse. Cap. 2. NASCONO LE QVATTRO GUARDIE DA QVATRO PROSPETTIVE, CHE HANno la mano, & la spada, ciò è dui fili, & dui piatti, che però fanno quattro effetti differenti, la prima si dimanda quelsito, doue uà la mano nel cauare la spada del fodero quando si uolge la puntauerso il nimico (perche intendiamo che tutte le [2] guardie massime nella spada sola si debbano cosi formare, & quando la mano si uolta un poco ingiù quella è detta seconda, la terza poi quando la mano sta naturalmente senza uoltarla ne nell’ una, ne nell’ altra parte, & la quarta quando si uolge essa mano dalla parte di dentro, laquale mano non può fare se non quelli quattro effetti nel uoltarla, & hauendola nella prima non può andare nella quarta senza passare per la seconda, & per la terza, che per essere l’ultimo effetto aquista nome di quarta. La prima è la più comoda per mettere mano alla spada, ancorche si possa fare, con la seconda, è con laterza, se ben non cosi facilmente, mà con la mano in quarta non si può già cauare la spada del fodero, & deesi sapere che niente si può fare, ilquale non proceda dalla natura di una di queste quattro noi diciamo natura, perche chi ben considera troua gran distanza trà l’una, & l’altra guardia, & questo per la larghezza del piatto della spada, & della mano, talmente che trà la prima, & la seconda uiè un meggio, douesi potrebbe fermare la mano, & così trà la seconda, & la terza, & trà la stessa terza, & la quarta, che perciò si potrebbe dire, che ui fossero quattro, guardie legitime, & tre’ bastarde, perche ciascuna bastarda tiene delle due, trà quali è formata, mà noi per non mettere confusione con tanti termini parlaremo solamente delle quattro legitime, lequali benissimo seruirãno anco per quelle tré bastarde, perche laqualità della guardia si considera non solo dal sito della mano, mà ancora dall’ effetto della punta, laquale dà la cognitione della forza di essa guardia, però ci deuiamo risoluere in queste quattro sole, & tanto più, quanto, che nella spada non cisono altre, che quattro maniere di ferire cioè didentro, di fuori di sotto, & di sopra, eui gran differenza similmente trà l’una, & l’altra guardia, come si mostrarà quando si trattarà della natura di esse, oue si uedranno di uerse diffese, & mutationi di ferire, secondo faranno formate longhe, ò ritirate, alte, o’ basse, & iui si trattarà della natura di tutte quante separatamente l’una dall’ altra. |

||||

[3] The divisions of the sword: the faible and the forte. The blade of the sword is divided into four parts; the first is the part nearest the hand, the second quarter extends to the middle of the blade, the other two extend to the point. The first part near the hand is the strongest for parrying, and there is no thrust or cut, delivered by the strongest arm, which, if parried in this part, the sword cannot defend and resist without disorder, if the rule and the time is observed, as will be explained. The second part is somewhat weaker, but still it will defend well enough, if you parry where your adversary's sword has less strength. The third part is not good, especially against cuts, unless strengthened with the adversary's body at the moment of parrying; this will be explained in considering the defence. The fourth part is entirely bad and must not be thought of in the defence, although in the attack it is the strongest and most deadly. It is also true that a cut made with half the third part and half the fourth is a strong attacking stroke, whereas a cut made with the third part only would not be one half so effective as a cut made with the fourth part as well. The first and second parts then are only to be used in the defence, and the third and fourth in the attack; so that the sword is divided, one half into the defensive part, and the other the offensive. |

DIVISIONE DELLA SPADA Per conoscere il debile, & il forte di essa. Cap. 3. LA LAMA DELLA SPADA SI DIVIDE IN QVATtro parti, la prima è quella che pende più uicina allà mano, la feconda è quello altro quarto, che ariua sino à meggia lama, l’altre sono l’ultima metà spartita anch’essa in due, laquale uà sino alla punta. La prima parte appresso la mano è la più forte per parare, ne ci è botta di punta, ò di taglio tirata da ogni galiardo braccio parata in quella parte, che la spada non diffenda, e resista senza disordine, osseruandosi però la regola, & il tempo, come si dira’ la seconda parte è alquanto più debile, non dimeno anch’essa diffende assai, quando si sà andare à parare oue la nimica spada hà minor forza. La terza parte non è buona massime contra taglii, ne si può contra essi adoprarla, se non fortìfficandola col corpo nimico nel tempo; che si para, come pure s’intenderà oue si parlarà delle diffese. La quarta parte è intieramente cattiua, ne bisogna fare pensiero d’ hauerla quanto alla diffesa, sé ben nella offesa è la più ualida, & quella che più mortalmente ferisce, si come anco è uero quando un taglio fà la ferita meggia con la terza parte & meggia con la quarta, che fà anco all’ hor grand’ offesa, & che se fosse [3] della terza sola non farebbe la metà di quello, che fà con la quarta, la seconda & la prima parte dunque non s’hanno da oprare se non per diffesa, & la terza, & quarta peroffesa, in modo tale, che essa spada uiene ad essere compartita meggia in diffendere, & meggia in offendere. |

||||

[4] Method of forming the counter-positions, showing The position of the arms and the body, and when they are to be formed. If you wish to form a sound counter-position, the position of the body and arms must be such that without touching the adversary's sword you are defended in the straight line from the point of his sword to your body, so that without making any movement of the body or the sword you are sure that your adversary cannot hit you in that line, but that if he wishes to attack he must move his sword elsewhere, with the result that his time is so long, that there is every opportunity to parry. But in forming this position care must be taken that your sword is held in such a way as to be stronger than your adversary's, so that it may offer resistance in defence. This rule can be observed against all positions and changes of your adversary, whether accompanied by the dagger or any other defensive weapon, or when you use the sword alone. He who can most subtly maintain this guard will have a great advantage over his adversary. But it often happens that when you form this guard, your adversary forms another against it. Often also this guard is formed so far out of distance that your adversary can wait until you begin to move your foot against him, and at the moment of year advance change his line, so that you are disconcerted by another counter-position. Therefore you must be full of devices and be able in a moment to take up another position of advantage against that of your adversary and make a fresh guard, unless you are so far within distance that you can hit him daring this change, and if in changing he has not retired, since if he had retired you could not hit him even if you had been within distance. You must then take up another counter-position and approach at the same time, to regain the same distance as before. In forming this counter-position you must bear in mind the rule, that the body must be so far distant that the adversary cannot hit, or, if you have approached within distance so that he could hit by advancing his foot, you must form the counter-position without moving the feet. In this way, if the adversary should attempt to hit during the movement, you could parry and hit him, or break ground;[7] in the latter case his sword, would not reach. But if in moving your weapons to take up this advantage, you have moved slowly, you could then abandon your object and hit at the very moment in which your adversary advanced to attack, parrying at the same time. So that if the first movement is made without violence, you can abandon your attempt and make another, as opportunity offers. In short, if you wish to get within distance with some safety, you must first form the counter-position, and if disconcerted by your adversary's counter-position, it will be better to break ground than to approach, until there is an opportunity to get an advantage. |

MODO DI FORMARELE CONTRAPOSTVRE Per intendere come l’armi si denno situare & il corpo, & quando si hà da cominciare à formarle. Cap. 4. VOLENDOSI FORMARE LA CONTRA POSTURA che stia bene fà di mestieri situare il corpo, & l’armè in modo, che senza toccare la nimica spada si sia diffeso dalla retta linea, che uiene dalla punta auersa al corpo, si che senza fare moto alcuno ne di corpo, ne di spacia si sia sicuro, che il nimico non possa ferire in quella parte, mà uolendo offendere sia neccessitato portare la spada altroue, & cosi il suo tempo uenga ad’ essere tanto longo, che dia gran comodita di parare, mà nell’ acconciarsi in cotal modo si richiede[8] si tuare la spada in guisa, che sia più forte della nimica acciò possa resistere nella diffesa, & laquale regola si può offeruare contra tutte le posture, & mutationi nimiche, tanto essendo accompagnata dal pugnale, onero da altra sorte di arma diffensiua, quanto con la sola spada, & collui, che saprà più sotilmente mantenersi in detta contraguardia haurà gran uantaggio soprà l’nimico, mà spesse uolte auiene che nel formarla esso nimico ne forma un’ altra contra quella & spesse uolte anco si uà à fare detta contrapostura lontano dalla misura tanto, che il nimico può aspettare che si comincia à mouere il piede contra di lui, & nel medesimo tempo, che si li auicina mutare effetto, & serrare di fuori l’offeruatore di questa regola con un’ altra contrapostura, Pertanto è neccessario l’essere ricco di partiti & sapere nell’ istesso punto trottare un’ altro sito uantaggioso à quello dell’ auerssario, & farli noua contraguardia, quando non si fosse tanto in misura, che si potesse ferirlo nella sua mutatione, ouero se esso nimico mutandosi non si fosse ritirato, perche in tal caso se bene si fosse stato nella misura non si; harebbe potuto ferirlo, mà si bene farli un’ altra contrapostura auicinandosi nel medesimo tempo per riguadagnare la stessa distanza di prima; & è di mestieri formando la contrapostura, di usare una certa raggione, ciò è che nelo situare il corpo si sia tanto lontano che il nimico, non possa ferire, ouero, essendosi gionto in distanza tale, cho detto nimico possa con l’auanzare il piede ferire, formarla senza moto de’ piedi, perche cosi facendo, ancor che esso nimico uolesse in quello mouimento ferire, potrebbesi parare, & ferire lui, ouero rompere di misura, che in quest’ alrro modo la nimica non arìuarebbe, mà se nel mouere l’armi per pigliare detto uantaggio, il moto fosse stato fatto lentamente, si potrebbe allhora lasciare l’in cominciato, & ferire in quello tempo proprio, che il nimico si fosse auanzato per offendere, parando insieme, si che se si farà il primo moto senza uiolenza si potrà lasciare l’ lincominciato, & farne un’ altro secondo l’ ocasione, dunque chi si uorà auicinare con qualche sicurtà nelle misure sarà neccessario formare prima la contra postura, & quello che si trouarà serato fuora dalla contrapostura nimica, haurà più raggione di stare in rompere di misura, che auicinarsi sino che li uenga comodità di pigliare il uantaggio. |

||||

[5] Explanation of the two distances, wide and close, and how to acquire the one or the other with least danger. You are within wide distance when by advancing the rear foot to the front you can make a hit. After forming the counter-position a little out of distance, you must begin to advance the foot in order to get within the required distance. But you must be on your guard, lest your adversary, being steady, at the moment when you move your foot to advance it, should advance his too and hit at the same time. Therefore, you must move it very carefully, remembering that your adversary may effect something during the movement. After forming the counter-position you must endeavour to throw him into disorder, or at least make some feint in order to have an opportunity to hit. Thus prepared for what may happen you are more guarded and can better resist attack. When you are within wide distance and your adversary makes some movement of his foot, provided he does not break ground, you can hit him in the nearest exposed part, even if he has not moved his weapons. This could not be done if he moved his weapons and stood firm on his feet, the reason being that a movement of the foot is slower than that of the weapons, and therefore he could parry before your sword arrived, while he remained steady; if there were no other way he could protect himself by breaking ground, so that your sword could not reach. Being thrown into disorder you would then be in danger of being hit before you had recovered. Therefore whenever he gives an opportunity without moving his feet, it would be better to approach within close distance in that time. In that distance you can reach with the sword by merely bending the body, without moving the feet, and the adversary is forced to retire to get out of such danger. If he does not move you could hit him even though he retained the advantage of the counter-position. If your adversary does not move, you can sometimes make a hit by judging the distance from the point of your sword to your adversary's body and the distance from the forte of his sword. If you consider both how much you must advance the point and how far you must move it from the adversary's forte, and understand that the time required for him to parry is the same as for you to hit, the sword will arrive before he has parried by the advantage of having moved first. If you see that his body is little exposed, as may happen, since one guard covers more than another, you can then attempt to hit in the exposed part, and as he moves to the defence change your line and hit in the second exposed part. These rules apply within close distance. If you are within wide distance and wish to advance within close distance, the danger is greater when the adversary stands steady on his guard, because if you raise your foot to advance it, you give him an opportunity to hit and retire, so that at the end of the movement you would be at the same distance, that is wide distance, and would have obtained nothing. All this is due to the fact that you cannot move your foot in less than two times, the one in lifting it and the other in putting it to the ground. For this reason some push the foot forward by scraping it along the ground, which is well enough in the hall, but in the street is likely to lead to a fall because of the many unevennesses. It is better then to lift it to make sure of not stumbling. Therefore in carrying the foot within close distance you must first form a good counter-position, and then lean all the weight of the body on the rear foot as you lift the forward foot, so that if in that moment your adversary should thrust you would be able to parry and to hit by bringing your foot to the ground, or even extend that movement which you had already begun beyond your first design, in order to reach more certainly in case your adversary broke ground in making his hit. If the adversary has not moved the pupil must after raising the foot carry it within close distance in such a way that the weight of the body rests on the rear foot, and is no nearer than when within wide distance. After putting your foot to the ground you could then by merely bending the body hit on the slightest movement if[!] the adversary in the line exposed nearest to your point. If you did not wish to wait you could hit in the manner already described. If while you are carrying your foot within close distance, your adversary should retire, you would remain within wide distance, and must bring the weight of the body from the rear foot to the forward and then bring up the rear foot close to the other. In approaching within close distance always take care that the body does not approach with the foot, but remains in the same position as before, and after bringing your foot to the ground carry forward the body. This rule should be observed in every case of requiring close distance, but after hitting you must in recovering your weapons draw back the body as far as possible and draw back the foot in such a way that if your adversary follows you are ready to parry and hit. If you find that your adversary is always breaking ground you must not grow angry and pursue him. Rather you must then proceed more carefully, for many feign a retirement with the object of drawing on their adversary and seeking an opportunity to hit in the moment of his pursuing. If you follow our method you will avoid this danger. It is better not to pursue one who flees, but rather to feign reluctance in order to reassure him and so draw him on, and then to seize an opportunity which he will not have time to avoid. |

[4] DICHIARATIONE PER INTENDERE Delle due misure quale sia larga & stretta, & il modo da tenersi per aquistare l’una, e l’altra per men pericolo. Cap. 5. MISURA LARGA SI DIMANDA QVELLA, LA QVALE con l’auanzare il piede anteriore l’huomo può ferire il nimico, in modo, che dopò formata la contrapostura poco lontana all’hora si dee cominciare à portare il piede inanzi per ariuare in detta misura, mà ricercasi lo stare auertito, perche essendo il nimico fermo, nel tempo che si moue il piede per portarlo oltre, che ancor lui non portasse il suo & battesse in quello punto medesimo, però si dee mouerlo molto consideratamente credendo, che esso nimico possa fare qualche effetto nel proprio tempo di quello moto; & dopò hauere fatta la contrapostura si dee procurare di farlo disordinare, se non con altro almeno con qualche sinta per hauere poi occasione di ferirlo, & cosi aspettando quello, che può accadere si stà più aueduto, & più facilmente si resiste alli incontri: qnando[!] poi si sia gionto in detta misura larga, & che il nimico si moua col piede per accomodarsi, purche non rompa di misura si può ferirlo nelo scoperto più prossimo ancorche egli non habbia fatto moto dell’armi, cosa che non si potrebbe fare se le mouesse, & stesse fermo de’ piedi, & questo perche il moto de piedi è piu’tardo che quello delle armi, & però potrebbe esso nimico parare inãzzi che la spada giongesse portata dal piede, mentre lui fosse fermo, & quando non si sapesse per altra uia diffendere, si saluarebbe col rompere di misura in modo che la spada non lo ariuaria, & essendo già disordinato si trouaria in pericolo di restare ferito prima, che si fosse rimesso talmente, che quando egli desse occasione senza mouere li piedi sarebbe più à proposito lo auicinarsi in quel tempo nella misura stretta, doue la spada ariua col solo piegare del corpo, & senza il mouere de’ piedi, che esso nimico sarebbe forzato à ritirarsi per non rimanere in pericolo tale, & se non si mouesse si potrebbe ferirlo, quando che si hauesse conseruato il uantaggio della contrapostura, & si potrebbe alcune uolte ancora ferire se bene il nimico non si mouesse cioè per il conoscere quale distanza fosse dalla propria punta al corpo nimico, & quanto lontana dal forte de lo stesso nimico, hauendo parimenti consideratione diquanto si debba auicinare la punta, ouero lontanarla da esso forte nel ferire, & conoscendo che sia tanto grande il tempo, che hà da fare l’auerssario in parare come il suo in ferire, la spada senz’altro ariuarà prima, che quello habbia parato, per il uantaggio, di essere stato il primo à mouersi; mà uedendo il corpo auerso póco scoperto, come può auenire, perche una guardia lo cuopere più dell’ altra, si può allhora andare per ferire quello scoperto, & nel tempo che’l nimico si moue alla diffesa mutare l’effetto, & ferire nelo scoperto secondo; Queste raggioni s’intedono doppo entrato nella misura stretta, perche ritrouãdosi nella larga, & uolendo andare l’huomo nella stretta, quando, che l’nimico stà fermo nella sua guardia il pericolo all’ hora è maggiore, perche leuando il piede per portarlo inanzi quello e un tempo, nelquale può esso nimico ferire con ritirarsi: indietro, di modo che finito il moto della distesa si trouarebbe il detto huomo lontano, cio è nella larga, & cosi non haurebbe [5] aquistato cosa alcuna, & tutto procederebbe perche non puo il piede mouersi con meno di dui tempi l’uno nel lèuarlo l’altro nel metterlo in terra, & per tale caogione alcuni lo spingono inanzi sdruzolandolo per terra, che nelle sale è buono, nelle strade è per cadere rispetto ai molti impedimenti, che possono trouarsi, che per tanto è meglio leuarlo assicurandosi di non traboccare, si che uolendo portare il piede nella misura stretta prima si richiede l’hauere formata ben la contrapostura, & doppo fondare tutto il peso del corpo sopra il piè di dietro leuando quello dinanzi, in modo che se in quel tempo il nimico tirasse si possa pigliare il contra tempo di parare, & ferire nel mettere propriamente il piede in terra anzi stendere quel moto, che si hauea cominciato più inanzi di quello che si hauea disegnato per meglio ariuare in ogni caso, che detto nimico rompesse di misura nel suo ferire, ilquale nimico se non si fosse mosso, douria il nostro osseruatore, leuato che hauesse il piede, portarlo nella misura stretta mà in modo, che tutto il corpo restasse sopra quello di dietro, acciò non s’auicinasse più di quello, che prima era, quando si trouaua nella misura larga, & doppo messo il piè in terra potria all’hora col solo piegare del corpo, ferire in ogni minimo moto ne lo scoperto più uicino alla punta, & anco, non uolendo aspettare, potria ferire con la maniera inanzi scritta, & se nel portare il piede in detta stretta misura esso nimico si ritirasse il nostro sarebbe ancora nella larga, & douria piegare il corpo, che era restato sopra il piè di dietro, nel anteriore, & poi ricuperare il medesimo di dietro appresso l’altro, contenersi sempre nelo portarsì nele strette misure in modo, che il corpo non si approssimi col piede, mà resti nelo medesimo segnò, doue prima era, & dopò fermato il piede portare il corpo, questa raggione è buona da osseruarsi in ogni caso di aquistare la misura stretta mà hauendo ferito si dee nel ricuperare l’armi allontanare sempre il corpo quanto, che più si può ricuperando il piede con comodità tale, che quantunq; il nimico seguisse si sia pronto à parare, & ferire, & trouando, chel detto nimico andasse sempre rompendo di misura non bisogna mettersi in furia, & uolerlo seguire, anzi all’hor si ricerca lo andare più considerato, perche molti singono ritirarsi procurando di tirarsi[9] dietro l’auerssario affine di trouare comodità da ferirlo nel tempo, che quello lo segue, & però tenendosi l’ ordine nostro cessarà simile pericolo & meglio è mentre che uno fuggie non uolerlo seguire anzi mostrare di ricredere per più assicurarlo, & con tale arte tirarlo inanzi, & poi pigliare quella occasione, the non potrà all’hora fuggire in tempo. |

||||

[6] Discourse on rushing in with the sword extended and the principles of the two times, showing that it is better to control the sword and observe the correct time. There are some who, in endeavouring to hit with the point, hurl the arm violently forward so as to give it greater force. This method is not good for the reasons which we shall bring forward. In the first place when you rush in with the sword, should your adversary anticipate you and defend the part where you intended to hit, you cannot change your line, as would be necessary, so that the adversary is sure of his defence. If he has also realised the weakest part of your thrust and pushed your sword in the direction in which it is being naturally carried, he will drive it out of line all the more quickly. His defence will be very simple without using any force, because if he pushes the sword in the direction in which it is naturally falling, it will fall the quicker without any resistance. In this manner his faible is stronger than the forte of the hitter. Moreover in completing the rush the point of the sword drops so that it cannot hit exactly the point aimed at, and also at the end of the extension it is impossible to prevent the arm and sword from dropping to the great advantage of your adversary. Further after one rush it is impossible to make another without withdrawing the arm again, which takes so long that, if the adversary has not hit at the first fall of your sword he could hit while you are withdrawing your arm, and recover before the second rush, with excellent opportunity of parrying and hitting even if he did it in two times, that is parrying first and then hitting. The rule of the two times then would be good enough against such a method, and all the more successful as those who rush cannot make any good feint; for in feinting they move the foot or the body without advancing the sword, or if they advance it often withdraw it even further than before in order to hit with greater force, a very slow and dangerous time. In treating of the rule of the two time, we say that, although it may succeed against some, it is not to be compared with the rule of parrying and hitting at the same time, because the true and safe method is to meet the body as it advances, before it has had time to withdraw and recover. If you then pursue you give an opportunity for parrying and hitting again. It has been our experience, that most of those who observe this rule of two times, if they can engage the adversary's sword, generally beat it in order then to proceed with the stroke. This would be successful but for the danger of being deceived. He whose sword has been beaten on the faible certainly cannot hit at the same time, as he is thrown into disorder by the beat. But if he happens to disengage he causes the sword which has beaten and missed to drop still further, and has an excellent chance of hitting. Even if he made a feint of beating, so that when the adversary disengaged he might beat in another part, he would still be in danger of being hit, because the adversary might make a feint of disengaging and return, and in this way the one who had meant to beat would not be able to parry. Finally it may be taken as established that it is impossible to beat your adversary's sword without putting your own out of line. Moreover sometimes if you attempt to beat the faible, according to rule, you meet the adversary's forte, which he has pushed forward, so that the beat fails and your adversary proceeds to hit without your being able to prevent him. In dealing with one who does not rush, but controls his sword, even though you beat his faible, his forte does not move, so that he can parry. Therefore, we conclude for these reasons and for many others which might be adduced, that it is better to parry and hit at the same time, though with the sword alone great judgment is required to effect the two at one moment. As to controlling the sword or thrusting with violence, controlling it is beyond comparison better, first because he who controls his sword, when it is beaten by the adversary, who means to hit in another line, can let it yield in the direction of the beat, and the forte will still defend, if the sword is held well advanced. Further it is certain that when your sword is beaten, it is immediately freed. Similarly it is more useful to know how to be master of your sword, to engage the adversary's faible and make a hit as opportunity offers, always holding his sword in subjection. If he cannot free his sword he cannot hit. Therefore this rule can be followed only by one who moves his sword without violence, works in such a way as to be always master of it, and if he is prevented by his adversary in any plan can abandon it and adopt another. He will hit at the very moment when his adversary has meant to prevent him, and without deviating his point or withdrawing it he will be able to carry it on to the adversary's body. The principle to be observed is this, that in proceeding to make a hit either by a feint of disengaging or any other change, when once you have begun to approach, the point toward the adversary, you must continue until you reach the body; for if you check the sword in order to disengage or change your line you will not arrive in time. This principle cannot be observed by one who rushes, so that the difference is easily understood. Moreover the sword which is held firm and accompanied by the foot and the body has greater force and exactness. He who so hold[!] it always controls it and does not let it drop after a hit. He has only to withdraw his foot in order to bring his body to safety, unless he has passed, and to engage the adversary's sword again. If your adversary as you withdraw, pursues or advances, you can hit again, defending at the same time. All this is because of the union between the sword, the feet and the body. If this rule is observed in the manner we have described, your parrying will be safe, whereas with the rule of the two times it is false; this will be better understood in its place. |

DISCORSO INTORNO IL LANCIARE DI SPADA, ET raggioni di dui tempi per fare sapere se sia meglio il portarla, & osseruare o; giusto tempo. Cap. 6. SONO ALCUNI, CHE UOLENDO FERIRE DI PUNta lanciano il braccio con uiolenza perdarli maggior forza, tale maniera non è buona per le raggioni che assignaremo prima perche, se il nimico in quello lanciare di spadga, preoccupasse, & diffendesse quel luogo oue si hà disegnato ferire non si può lasciare quello effetto, & farne un’ altro, come si richiederebbe talche esso nimico uiene ad’essere certo della diffesa, & se egli haurà conosciuto la parte più debile, & l’haurà spinta, doue la natura la porta tanto più [6] presto haurà fatto uscire di presenza quella, slanciata, & sarasi esso diffeso molto comodamente senza oprare forza alcuna, perche chi spinge la spada da quella parte oue dee cadere naturalmente essa uà à cadere più presto & senza fare resistenza nissuna, & in questo modo più uale il debile di quello che para, che’ il forte di quello, che fere; in oltre nel finire il slancio la punta della spada, sguinza in modo, che non può andare à ferire,oue guistamente si hauea tolta la mira, & anco nel finire detta distesa non si può tenere il braccio, & la spada, che non cadano con dare gran comodità al nimico di ferire, aggiungendosi ancora, che dopò slanciata unauolta non si può slanciare un’ altra, se non ritirando il braccio di nouo, tempo tanto grande, che se l’istesso nimico non hauesse, ferito nella prima caduta potrebbe ferire nel tempo di questo ritirare il braccio, & saluarsi anco prima, che si slanciasse un’altra uolta, & con hauere buona comodità ditornare à parare, & ferire, se bene lo facesse di dui tempi cio è prima parando, & poi ferendo, in modo che la raggione de dui tempi uerrebbe ad’essere assai buona contra simile maniera, & tanto più riuscibile, quanto che costoro, che feriscono di slancio non possono fare finta di forte alcuna, che stia bene, perche nel fingere fanno similmente moto col piede, o col corpo, senza auanzare la spada ò se pure l’auanzano la ritirano ben spesso più indietro, che prima noti era per ferire con maggiore forza, tempo tardissimo, & dannoso. Hora per trattare delle raggioni de’ dui tempi diciamo, che se bene contra di alcuni potrebbero riuscire, nondimeno non hanno da equipararsi alle raggioni di parare, & ferire in tempo medesimo, perche il uero, & sicuro modo è di incontrare il corpo nel punto medesimo; che quello si spingie inanzi, altrimenti egli subbito s’allontana, & resta saluo, & chi lo seguittasse li darebbe comodità di parare, & tornare à ferire un’altra uolta. Habbiamo ueduto per isperienza, che i piu di questi, iquali osseruano le dette raggioni de’ dui tempi, come possono hauere la spada nimica sogliono batterla per potere poi andare à ferire, il che sarebbe assai riuscibile quando non ci fosse il pericolo di reftare ingannato, perche colui à chi uiene battuta la spada nel debile non può certamente ferire in medesimo tempo per hauerla disordinata dalla battuta, mà se auiene, che caui caggiona, che la spada, dell’altro, che hà battuto, non hauendo trouata la nimica, fa caduta maggiore, & porge oportunissimo tempo al nimico di ferire, & ancorche fosse andato per fingere di batterla acciò detto nimico la cauasse per batterla poi dall’altra parte, non dimeno ancor questo sarebbe pericoloso di restare ferito, perche lo stesso hauria potuto fingere di cauare, & rimetterla, & à questo modo colui, che hauesse uoluto battere non hauria potuto parare, si hà dunque da tenere per fermo, che non si può battere l’altrui spada, che non si suii la sua propria dalla presenza, & tanto più non la trouando, oltreche alcune uolte si uà per battere il debile, come è di raggione, & si troua il forte spinto oltre dall’auerssario, restando in tal modo fallace la battuta, & all’hora uiene lo stesso auerssario à ferire senza potere essere impedito; Mà doppo questo hauendo à fare con chi non lancia mà porta la spada, anco che seli batta il debile non dimeno il suo forte non si moue in modo, che può parare, & però si conchiude tanto per queste raggioni, quanto per molte altre, che potriano addursi, che meglio è il parare, & ferire in tempo medesimo, se bene con la sola spada ci si richiede giuditio grande à uolere che faccia questi dui effetti in un solo punto. Quanto al portare della spada, ouero slanciarla meglio senza comparatione è il portarla, come si intenderà, prima perche una spada battuta, mentre è portata da un’ luogo all’altro, colui, che la porta può lasciarla andare da quella parte doue il nimico la batte, che andarà à ferire in un’altro luogo, & il forte restara sempre alla diffesa, quando si giocarà la spada auanzata, oltre che questo tale è certo che essendo battuta è fatta ancora subbito libera, similmente è più utile lo sapersi conseruare padrone di essa, occupando il debile nimico, & portarsi à ferire secondo l’occasione con tenere sempre suggita la nimica spada, laquale se dall’ ingegnodi esso nimico non si saprà liberare lui non potra mai serire, & perciò questa raggione non può essere osseruata se non da colui che moue la spada da un’luogo. all’altro senza lanciarla, & opera in guisa, che [7] sempre è padrone di essa, & che se uà per farè un’ effetto quale li uenga impedito dalo stesso nimico sà lasciare l’incominciato, & farne un altro; questo tale adunque ferirà nelo medesimo tempo, che l’auerssario l’haurà uoluto impedire, & senza deuiare la punta, ò ritirarla, potrà continouare sino al corpo del detto auerssario, perche l’ordine, che hà da tenere è che andando per ferire, ò per fingere di uolere cauare ò fare altra mutatione, mentre che hà cominciato ad auicinarela punta uerso il nimico, è neccessario continouare sino che la peruiene al corpo, perche chi la uolesse trattenere affine di cauare, ò mutare effetto non ariuarebbe di tempo, & questo non si può osseruare da quello, che slancia, & perciò si può benissimo comprendere la differenza, & tanto più che portandola ferma, & accompagnata dal piede, & dal corpo la spada hà maggior forza, maggior giustezza, & chi la porta è sempre più padrone di essa non facendo caduta alcuna doppo che hà ferito, talmente che non occore fare altro doppo ferito se non di ritirare il piede, se non si fosse passato, per dilongare il corpo, & per ritornare di nouo all’ aquisto della nimica spada, & in caso che il detto nimico, in quello ritirarsi, seguittasse per ferire, ò auicinarsi, si può ritornare à ferire con la diffesa insieme, & tutto per la unione in che si troua di spada, piedi, & corpo, laquale osseruatione se nel soprascrittò modo sarà usata, il parare sarà sicuro, si come nelle raggioni de’ dui tempi è falso, come à suo luogo anco meglio s’intenderà. |

||||

[7] Discourse on cutting. How many cuts there are and how they are made, their nature, and whether it is better to use the point or the edge. The principal cuts are four; they are delivered in different ways and in different directions, as will be seen in the plate which follows (pl. 1.) with their names. The names are derived from the four principal cuts, that is mandiritto, riverso, sottomano and montante. They are delivered in various ways, for some deliver them from the shoulder, some from the elbow, some from the wrist, and some again from the shoulder but with the arm extended and stiff, keeping the point always directed towards the adversary. In making the first cut from the shoulder, the arm is raised and makes a circle with the sword in order to strike with greater force. This is the worst of all because of its excessive slowness and because you may easily be hit as you raise the arm, as you let it fall, or after it has fallen; for as the sword is not supported by the adversary's weapon or body, there is nothing to prevent it from passing on behind his back; or if the hit is made downwards, the sword is in danger of being broken on the ground. In either case so much time is lost that your adversary may easily hit. The second method from the elbow also carries the hand out of line, both when it is raised and when it falls after missing, so that in this case too you may be hit, but not so easily, as the sword does not make such a large circle, nor does the raising of the arm uncover so much, nor the sword fall so far. Therefore as the movement is quicker and you remain better covered, this method is better than the first. The third method, made from the wrist downwards with the arm straight, although the sword makes a circle is beyond comparison better than the two first described, since the body is more covered. Nor can you be so easily hit, since it is quicker, and the point in falling remains in such a position that you can parry with the forte either thrust or cut, and can cut again. Similarly the fourth method with the arm stiff and extended is far better than the two first, since you hit without making a circle with the sword, raising it little or nothing. The sword is allowed to fall on an exposed point, and when your adversary makes a circle with his sword in order to hit, with this fourth method you can continue your stroke, as you will certainly hit before his falls. You will be all the more secure if you have worked with the feet and the body, as you should, because if you remained upright when your sword fell, you could not recover in time, especially if your adversary's cut had been made from the elbow. But if you lower your body the sword is more quickly recovered and has less distance to move in returning to the defence, for as you hit with the arm stiff and extended without bending the wrist, the sword still remains in front and can easily return to the straight line. For this reason the fourth method is better than the two first and in defence better than the third, although it appears to us that the third is much freer or less restricted, and without requiring so much strength has more variety and can more easily deceive the adversary. He who wishes to make a cut with safety, must wait a fitting opportunity, since he cannot make the stroke in a moment, and the time might have passed before the sword arrived. You can make a feint in order to put the adversary in subjection, and whilst he is parrying the cut, thrust at him, or make a feint of a thrust, and cut. The latter method would be necessary if you wish to move without waiting, for, if your adversary remained steady, it would not be good to make a feint of a cut in order to thrust, owing to the length of the movement, during which you might be hit. You can, as has been said, make a feint of a thrust in order to cut, and even if he parries the cut, still make a thrust. Further the feint of a cut, when your adversary stands firm, is not good because of the two times involved in raising and dropping the arm. All the cuts are very long, and he who cuts cannot do so in the time of a parry (we speak of the sword alone), whilst the adversary has always time to protect himself and even to make a hit when you are trying to parry. It is true that in parrying you can put your adversary in subjection and deprive him of the power to do anything, and even hit him before he can save himself; but of this we shall speak when we treat of the defence and the attack. Since cutting is not very useful we shall not dilate on it more than is necessary to show the respective merits of the thrust and the cut. Still it is well to be acquainted with both. In cutting greater strength is required, which is a disadvantage. The sword, if it misses, is thrown into disorder, and the body too. Recovery is not so easy, so that you are in more danger than with the thrust. Further it is less deadly; so that in all respects thrusting is more advantageous. With the point you reach further, more quickly and can more easily recover. In brief thrusting is more noble and excellent, for it includes all the subtlety of arms, whereas in cutting there is neither the counter-time nor the time, since for the most part two times are involved. We do not intend to discuss this further than we have done in the preceding chapter in relation to the two times, but to consider the more subtle, difficult and profitable points. If for example two men were opposed, one who excelled at the cut and the other at the thrust, without a doubt the latter would prevail for the reasons we have given, though his opponent were the stronger man. We conclude that it is better to use the point only, especially in engagements corps à corps without armour. With armour we should deem it good to use both; so too against a number of opponents, for the cut causes greater confusion and may parry several thrusts. |