|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Difference between revisions of "Joachim Meyer"

| (12 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

| pseudonym = | | pseudonym = | ||

| birthname = | | birthname = | ||

| − | | birthdate = | + | | birthdate = August(?) 1537 |

| birthplace = Basel, Germany | | birthplace = Basel, Germany | ||

| − | | deathdate = | + | | deathdate = February 1571 (aged 33) |

| deathplace = Schwerin, Germany | | deathplace = Schwerin, Germany | ||

| resting_place = | | resting_place = | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

| manuscript(s) = {{plainlist | | manuscript(s) = {{plainlist | ||

| [[Joachim Meyers Fechtbuch (MS Bibl. 2465)|MS Bibl. 2465]] (1561) | | [[Joachim Meyers Fechtbuch (MS Bibl. 2465)|MS Bibl. 2465]] (1561) | ||

| − | | [[Joachim Meyers Fäktbok (MS A.4º.2)|MS A.4º.2]] ( | + | | [[Joachim Meyers Fäktbok (MS A.4º.2)|MS A.4º.2]] (1563-68) |

| [[Fechtbuch zu Ross und zu Fuss (MS Var.82)|MS Var.82]] (1570-1) | | [[Fechtbuch zu Ross und zu Fuss (MS Var.82)|MS Var.82]] (1570-1) | ||

}} | }} | ||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

| below = | | below = | ||

}} | }} | ||

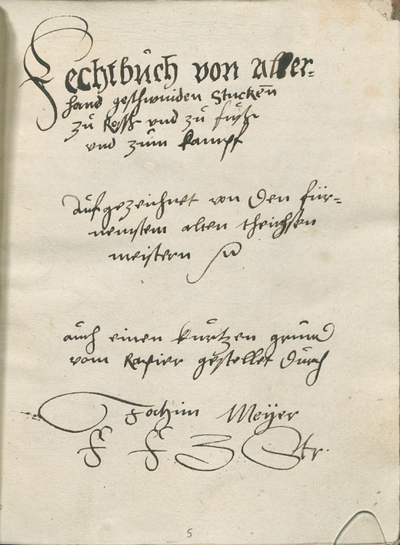

| − | '''Joachim Meyer''' ( | + | '''Joachim Meyer''' (〰 16 Aug 1537, † Feb 1571)<ref>For Meyer's baptism, see Liam Clark, [https://evergreenfencing.substack.com/p/joachim-meyers-family-revealed Joachim Meyer's Family Revealed], ''Evergreen Fencing'', 2024. Meyer's death was reported to Johann Albrecht von Mecklenburg on 24 Feb, so it likely occured a few days prior to that; see [[Olivier Dupuis]], "Joachim Meyer, escrimeur libre, bourgeois de Strasbourg (1537 ? - 1571)", ''Maîtres et techniques de combat'', Dijon: AEDEH, 2006.</ref> was a [[century::16th century]] [[nationality::German]] cutler, [[Freifechter]], and [[fencing master]]. He was the last major figure in the tradition of the German grand master [[Johannes Liechtenauer]], and in the later years of his life he devised at least four distinct [[fencing manual]]s. Meyer's writings incorporate both the traditional Germanic technical syllabus and contemporary systems that he encountered in his travels, including Italian rapier fencing. In addition to his fencing practice, Meyer was a Burgher, master cutler, and eventual officer of the local Smith's Guild.<ref name="Naumann">Naumann, Robert. ''Serapeum.'' Vol. 5. T.O. Weigel, 1844. pp 53-59.</ref> |

| − | Meyer was born in Basel,<ref>According to his wedding certificate.</ref> where he presumably apprenticed as a cutler. | + | Meyer was born in Basel,<ref>According to his wedding certificate.</ref> where he presumably apprenticed as a cutler. Records show that by 4 June 1560 he had settled in Strasbourg, where he married Appolonia Ruhlman (Ruelman)<ref name="Dupuis">[[Olivier Dupuis]], "Joachim Meyer, escrimeur libre, bourgeois de Strasbourg (1537 ? - 1571)", ''Maîtres et techniques de combat'', Dijon: AEDEH, 2006.</ref> and was granted the rank of master cutler. His interests had already moved beyond smithing, however, and in 1561, Meyer's petition to the City Council of Strasbourg for the right to hold a [[Fechtschule]] was granted. He would repeat this in 1563, 1566, 1567 and 1568;<ref name="Van Slambrouck">Van Slambrouck, Christopher. "[https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291284452_The_Life_and_Work_of_Joachim_Meyer The Life and Work of Joachim Meyer]". ''Meyer Frei Fechter Guild, 2010. Retrieved 29 January 2010.''</ref> the 1568 petition is the first extant record in which he identifies himself as a fencing master. |

| − | + | Meyer probably wrote his first manuscript ([[Joachim Meyers Fechtbuch (MS Bibl. 2465)|MS Bibl. 2465]]) in 1561 for Georg Johann Ⅰ, Count Palatine of Veldenz,<ref name="Wittelsbach">Though as a prince of the Wittelsbach dynasty, he was addressed by the loftiest titles held by the family: Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria.</ref> and his second ([[Joachim Meyers Fäktbok (MS A.4º.2)|MS A.4º.2]]) some time between 1560 and 1568 for Otto (later Count of Solms-Sonnewalde).<ref>[[Roger Norling|Norling, Roger]]. "[http://www.hroarr.com/the-history-of-joachim-meyers-treatise-to-von-solms/ The history of Joachim Meyer’s fencing treatise to Otto von Solms]". Hroarr.com, 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2015.</ref> Both of these manuscripts contain a series of lessons on training with [[long sword]], [[dusack]], and [[rapier]]; the 1561 also covers [[dagger]], [[polearms]], and [[armored fencing]]. His third manuscript ([[Fechtbuch zu Ross und zu Fuss (MS Var.82)|MS Var.82]]), produced in the 1560s, is of a decidedly different nature. Like many fencing manuscripts from the previous century, it is an anthology of treatises by a number of prominent German masters including [[Sigmund ain Ringeck]], [[pseudo-Peter von Danzig]], and [[Martin Syber]], and also includes a brief outline by Meyer himself on a system of rapier fencing based on German [[Messer]] teachings and the teachings of Stephen Heinrich, Count of Eberstein. | |

| − | + | Finally, on 24 February 1570, Meyer completed an enormous treatise entitled ''[[Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meyer)|Gründtliche Beschreibung, der freyen Ritterlichen unnd Adelichen kunst des Fechtens, in allerley gebreuchlichen Wehren, mit vil schönen und nützlichen Figuren gezieret und fürgestellet]]'' ("A Foundational Description of the Free, Chivalric, and Noble Art of Fencing, Showing Various Customary Defenses, Affected and Put Forth with Many Handsome and Useful Drawings"); it was dedicated to Johann Casimir, Count Palatine of Simmern,<ref name="Wittelsbach"/> and illustrated at the workshop of [[Hans Christoff Stimmer]]. It contains all of the weapons of the 1561 and '68 manuscripts apart from fencing in armor, and dramatically expands his teachings on each. | |

| − | |||

| − | Finally, on 24 February 1570, Meyer completed an enormous treatise entitled ''[[Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meyer)|Gründtliche Beschreibung, der freyen Ritterlichen unnd Adelichen kunst des Fechtens, in allerley gebreuchlichen Wehren, mit vil schönen und nützlichen Figuren gezieret und fürgestellet]]'' ("A | ||

Unfortunately, Meyer's writing and publication efforts incurred significant debts (about 300 crowns), which Meyer pledged to repay by Christmas of 1571.<ref name="Dupuis"/> Late in 1570, Meyer accepted the position of Fechtmeister to Duke Johann Albrecht of Mecklenburg at his court in Schwerin. There Meyer hoped to sell his book for a better price than was offered locally (30 florins). Meyer sent his books ahead to Schwerin, and left from Strasbourg on 4 January 1571 after receiving his pay. He traveled the 800 miles to Schwerin in the middle of a harsh winter, arriving at the court on 10 February 1571. Two weeks later, on 24 February, Joachim Meyer died. The cause of his death is unknown, possibly disease or pneumonia.<ref name="Van Slambrouck"/> | Unfortunately, Meyer's writing and publication efforts incurred significant debts (about 300 crowns), which Meyer pledged to repay by Christmas of 1571.<ref name="Dupuis"/> Late in 1570, Meyer accepted the position of Fechtmeister to Duke Johann Albrecht of Mecklenburg at his court in Schwerin. There Meyer hoped to sell his book for a better price than was offered locally (30 florins). Meyer sent his books ahead to Schwerin, and left from Strasbourg on 4 January 1571 after receiving his pay. He traveled the 800 miles to Schwerin in the middle of a harsh winter, arriving at the court on 10 February 1571. Two weeks later, on 24 February, Joachim Meyer died. The cause of his death is unknown, possibly disease or pneumonia.<ref name="Van Slambrouck"/> | ||

| Line 90: | Line 88: | ||

== Treatises == | == Treatises == | ||

| − | Joachim Meyer's writings are preserved in three manuscripts prepared in the 1560s: the 1561 [[Joachim Meyers Fechtbuch (MS Bibl. 2465)|MS Bibl. 2465]] (Munich), dedicated to Georg Johannes von Veldenz; the 1563-68 [[Joachim Meyers Fäktbok (MS A.4º.2)|MS A.4º.2]] (Lund), dedicated to Otto von Solms; and the [[Fechtbuch zu Ross und zu Fuss (MS Var.82)|MS Var. 82]] (Rostock), | + | Joachim Meyer's writings are preserved in three manuscripts prepared in the 1560s: the 1561 [[Joachim Meyers Fechtbuch (MS Bibl. 2465)|MS Bibl. 2465]] (Munich), dedicated to Georg Johannes von Veldenz; the 1563-68 [[Joachim Meyers Fäktbok (MS A.4º.2)|MS A.4º.2]] (Lund), dedicated to Otto von Solms; and the [[Fechtbuch zu Ross und zu Fuss (MS Var.82)|MS Var. 82]] (Rostock), which includes notes on the teachings of Stephan Heinrich von Eberstein and which Meyer may have still been working at the time of his death in 1571. The former two manuscripts are substantially similar in text and organization, and it seems clear that the Munich was the basis for the much shorter Lund. |

| + | |||

| + | Dwarfing these works is the massive book he published in 1570 entitled ''[[Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meyer)|Gründtliche Beschreibung der ...Kunst des Fechtens]]'' ("A Foundational Description of the... Art of Fencing"), dedicated to Johann Kasimir von Pfalz-Simmern. Meyer's writings purport to teach the entire art of fencing, something that he claimed had never been done before, and encompass a wide variety of teachings from disparate sources and traditions. To achieve this goal, Meyer seems to have constructed his treatises as a series of progressive lessons, describing a process for learning to fence rather than merely outlining the underlying theory or listing the techniques. In keeping with this, he illustrates his techniques with depictions of fencers in courtyards using training weapons such as two-handed foils, wooden dusacks, and rapiers with ball tips. | ||

| − | The first section of Meyer's teachings is devoted to the long sword (the sword in two hands), which | + | The first section of Meyer's teachings is devoted to the long sword (the sword in two hands), the traditional centerpiece of the [[Liechtenauer]] tradition which Meyer describes as the foundational weapon of his system, and this section devotes the most space to fundamentals like stance and footwork. His long sword system draws upon the teachings of ''Freifechter'' [[Andre Paurenfeyndt]] (via [[Der Allten Fechter gründtliche Kunst (Christian Egenolff)|Christian Egenolff's reprint]]) and Liechtenauer glossators [[Sigmund ain Ringeck]] and [[Lew]], as well as using terminology otherwise unique to the brief [[Recital]] of [[Martin Syber]]. Not content merely to compile these teachings as his contemporary [[Paulus Hector Mair]] was doing, Meyer sought to update—even reinvent—them in various ways to fit the martial climate of the late sixteenth century, including adapting many techniques to accommodate the increased weight and momentum of a [[greatsword]] and modifying others to use beats with the flat and winding slices in place of thrusts to comply with street-fighting laws in German cities (and the rules of the ''Fechtschule''). |

| − | The second section is designed to address | + | The second section is designed to address newer weapons gaining traction in German lands, the dusack and the rapier, and thereby find places for them in the German tradition. His early Munich and Lund manuscripts present a more summarized syllabus of techniques for these weapons, while his printed book goes into greater depth and is structured more in the fashion of lesson plans.<ref>Roberts, James. "[http://www.hroarr.com/system-vs-syllabus-meyers-1560-and-1570-sidesword-texts/ System vs Syllabus: Meyer’s 1560 and 1570 sidesword texts]". Hroarr.com, 2014. Retrieved 14 February 2015.</ref> Meyer's dusack system, designed for the broad-bladed sabers that spread into German lands from Eastern Europe in the 16th century,<ref>[[Roger Norling]]. "[http://hroarr.com/the-dussack/ The Dussack - a weapon of war]". Hroarr.com, 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2015.</ref> combines the old [[Messer]] teachings of [[Johannes Lecküchner]] and the dusack teachings of Andre Paurenfeyndt with other unknown systems (some have speculated that they might include early Polish or Hungarian saber systems). His rapier system, designed for the lighter single-hand swords spreading north from Iberian and Italian lands, seems again to be a hybrid creation, integrating both the core teachings of the 15th century thrust-centruc Liechtenauer tradition as well as components that are characteristic of the various regional Mediterranean fencing systems (including, perhaps, teachings derived from the treatise of [[Achille Marozzo]]). Interestingly, Meyer's rapier teachings in the Rostock seem to represent an attempt to unify these two weapon systems, outlining a method for rapier fencing that includes key elements of his dusack teachings; it is unclear why this method did not appear in his book, but given the dates it may be that they represent his final musings on the weapon, written in the time between the completion of his book in 1570 and his death a year later. |

| − | The third section is omitted from the Lund manuscript but present in the Munich and the 1570, and covers dagger, wrestling, and various pole weapons; to this, the Munich adds | + | The third section is omitted from the Lund manuscript but present in the Munich and the 1570, and covers dagger, wrestling, and various pole weapons; to this, the Munich adds a short section on armored fencing. His dagger teachings, designed primarily for urban self-defense, seem to be based in part on the writings of Bolognese master Achille Marozzo,<ref>[[Roger Norling|Norling, Roger]]. "[http://www.hroarr.com/meyer-and-marozzo-dagger-comparison/ Meyer and Marozzo dagger comparison]". Hroarr.com, 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2015.</ref> but also include much unique content of unknown origin (perhaps the anonymous dagger teachings in his Rostock manuscript). His staff material makes up the bulk of this section, beginning with the short staff, which, like Paurenfeyndt, he uses as a training tool for various pole weapons (and possibly also the greatsword), and then moving on to the halberd before ending with the long staff (representing the [[pike]]). As with the dagger, the sources Meyer based his staff teachings on are largely unknown. |

| − | ''To view the sword, dusack, and rapier teachings of the Munich and Lund manuscripts side-by-side and study the overlaps and differences, see [[Joachim Meyer/Manuscript Comparison]].'' | + | :''To view the sword, dusack, and rapier teachings of the Munich and Lund manuscripts side-by-side and study the overlaps and differences, see [[Joachim Meyer/Manuscript Comparison]].'' |

{{master begin | {{master begin | ||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="3 | + | | rowspan="3" | [[File:MS Bibl. 2465 IIv.jpg|400px|center]] |

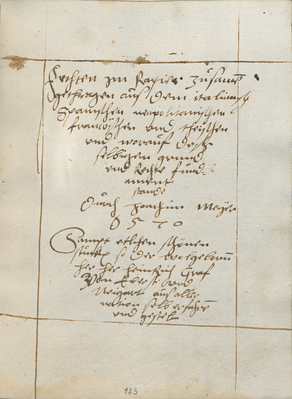

| <p>'''To the Noble High-born Prince and Lord, Lord Georg Hansen Count Palatine of the Rhine Duke of Bavaria, Count at Veldenz and Lord of Lutzelstein, my gracious Prince and Lord'''</p> | | <p>'''To the Noble High-born Prince and Lord, Lord Georg Hansen Count Palatine of the Rhine Duke of Bavaria, Count at Veldenz and Lord of Lutzelstein, my gracious Prince and Lord'''</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 IIIr.jpg|1|lbl=IIIr.1}} | | {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 IIIr.jpg|1|lbl=IIIr.1}} | ||

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | <p>Your Princely Grace</p> | |

<p>  Subservient, Obedient, Willing,</p> | <p>  Subservient, Obedient, Willing,</p> | ||

<p>    Joachim Meyer<br/>    Frey Fechter</p> | <p>    Joachim Meyer<br/>    Frey Fechter</p> | ||

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 IVv.jpg|2|lbl=IVv.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 646: | Line 646: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[73]</small> But if he cuts at you from his left to your fingers, then also cut in simultaneously with the flat and crossed hands, so that the long edge of the blade clashes in on his blade, and your cross is put horizontally in the Crown, when you make this Crown Cut correctly, then always hit with the sharp edge by the half edge, however if you are too far from him and he cuts after at your hands, then cut him to the head, and with that you protect yourself in parrying, thus you have defended your fingers from damage, but if he cuts in simultaneously with a step, then spring with every cut to his parrying with closing.</p> | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 013v.jpg|4|lbl=13v.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 014r.jpg|1|lbl=14r.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 013v.jpg|4|lbl=13v.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 014r.jpg|1|lbl=14r.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 1,061: | Line 1,061: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[35]</small> '''From the Stepping'''</p> | |

<p>Stepping breaks, what one fights, he who does not do it, it fights one to the ground as he wills it, if he does not do it correctly, he is unsuccessful, therefore the saying in the twelve rules is made and understood:</p> | <p>Stepping breaks, what one fights, he who does not do it, it fights one to the ground as he wills it, if he does not do it correctly, he is unsuccessful, therefore the saying in the twelve rules is made and understood:</p> | ||

| Line 1,069: | Line 1,069: | ||

<p>Every cut must have its step, they must go together, otherwise the ''stuck'' will not work, for much relies on stepping, then if you step too soon or too late, thus you (will be responsible for your own loss). The stepping makes it so that the opponent’s work cannot go on, but that yours’ can, you must attack the opponent in a stance or wide position, so he thinks he has you for sure but that you are further from him than you have presented yourself, if on the other hand the opponent thinks you want to step in at him, then do not hurry to the attack. There is great art and cunning in the stepping, and the right measure lies in it. About it, all fencers say, so notice when you are close to the man, then let yourself note with the cutting as if you were treading with great, wide steps, but remain with your feet near to each other, meanwhile, strike off the man secretly like one who wants to steal a step, once you think it is time, then step further with your feet and boldly attack.</p> | <p>Every cut must have its step, they must go together, otherwise the ''stuck'' will not work, for much relies on stepping, then if you step too soon or too late, thus you (will be responsible for your own loss). The stepping makes it so that the opponent’s work cannot go on, but that yours’ can, you must attack the opponent in a stance or wide position, so he thinks he has you for sure but that you are further from him than you have presented yourself, if on the other hand the opponent thinks you want to step in at him, then do not hurry to the attack. There is great art and cunning in the stepping, and the right measure lies in it. About it, all fencers say, so notice when you are close to the man, then let yourself note with the cutting as if you were treading with great, wide steps, but remain with your feet near to each other, meanwhile, strike off the man secretly like one who wants to steal a step, once you think it is time, then step further with your feet and boldly attack.</p> | ||

| − | + | | {{paget|Page:MS Bibl. 2465|021v|jpg|lbl=21v}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,439: | Line 1,439: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | [[File:MS Bibl. 2465 036r.jpg|400px|center]] | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[61]</small> In ''Zufechten'' pay attention and when you note that one desires to cut in high over at you, so then drive under it with the Bow and capture his arm then grab with your left hand quickly to the crook of his knee<ref>''Kniebugen'' = crook of knee, bend of knee.</ref> on his forward most leg, and heave upwards then push up away from you, thus he falls.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{paget|page:MS Bibl. 2465|036r|jpg|lbl=36r}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,772: | Line 1,772: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[54]</small> Item: If you get too close to him, thus you should use slicing, traveling after with the point, setting on, cutting over, winding over, pushing, grabbing and throwing.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 048r.jpg|2|lbl=48r.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,371: | Line 2,371: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[104]</small> These ''Stuck'', along with the Change Cuts, should be changed from one ''Stuck'' to another and from one cut to another, and also varied with the thrusts. The man who wants to defend himself with the rapier, should diligently study this book.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 066bv.jpg|5|lbl=66bv.5}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,649: | Line 2,649: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[51]</small> Item: Grab him by his right hand, swing it up and go through under his arm. Then step with your right foot between both his legs, grab from outside with your right hand around his leg, pull his right arm well towards you over your shoulder and heave upwards, throwing him to your liking.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 075v.jpg|3|lbl=75v.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,800: | Line 2,800: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[25]</small> Several clarifications of good strikes with the staff: When you bind one at the forward point, jerk your hand over you and give the staff a swing with your left hand and strike him above to the head, Cross Strike is when you pull in the bind and strike with both hands to his forward arm from the other side. Round Strike I want to save for the halberd. Locker Strike is the one with an overhand. Through Strike is when you strike him through to his forward leg and back in again to the other side.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 082r.jpg|5|lbl=82r.5}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,947: | Line 2,947: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[26]</small> Item: In the winding and running in don't be too high, for generally you will not be harmed by it at all, to the winding must belong a very great speed, if you note that someone wants to run in at you with winding, then jump back a little with the halberd across your body or come in before quickly to the opening.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 088v.jpg|3|lbl=88v.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 3,137: | Line 3,137: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[32]</small> '''A good Provoking ''Stuck'''''</p> | |

<p>Item: Lay your staff on your shoulder, position yourself with the intention to thrust, but don't actually do it, rather, change with your pike into the Low Guard, so that he is incited to strike when he thinks you have violated (your original intention), so then take out his thrust with a slicing off and thrust in likewise.</p> | <p>Item: Lay your staff on your shoulder, position yourself with the intention to thrust, but don't actually do it, rather, change with your pike into the Low Guard, so that he is incited to strike when he thinks you have violated (your original intention), so then take out his thrust with a slicing off and thrust in likewise.</p> | ||

| − | + | | {{section|page:MS Bibl. 2465 100v.jpg|3|lbl=100v.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 3,420: | Line 3,420: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Joachim Meyer/Jordan Elliot Finch 2023 MAF|51}} | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 111v.jpg|6|lbl=111v.6|p=1}} {{paget|Page:MS Bibl. 2465|112r|jpg|p=1}} | {{section|Page:MS Bibl. 2465 111v.jpg|6|lbl=111v.6|p=1}} {{paget|Page:MS Bibl. 2465|112r|jpg|p=1}} | ||

| Line 3,444: | Line 3,444: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS A.4º.2 02v.jpg|400px|center]] |

| <p>'''To the Well born Lord, Duke Ottbo Count of Solms, Lord of Munzenberg and Sonnewaldt my Gracious Sir'''<br/><br/></p> | | <p>'''To the Well born Lord, Duke Ottbo Count of Solms, Lord of Munzenberg and Sonnewaldt my Gracious Sir'''<br/><br/></p> | ||

| Line 3,452: | Line 3,452: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | <p>Your Grace</p> | |

<p>Subserviently Willing</p> | <p>Subserviently Willing</p> | ||

<p>Joachim Meyer<br/>Fencing Master</p> | <p>Joachim Meyer<br/>Fencing Master</p> | ||

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 04r.jpg|2|lbl=04r.2|p=1}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 3,499: | Line 3,499: | ||

<p>Thus you shall mark in the binding of the swords, as you shall feel if he has become hard or soft in the bind, with the cut.</p> | <p>Thus you shall mark in the binding of the swords, as you shall feel if he has become hard or soft in the bind, with the cut.</p> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <p>Item: If he is yet again, strong or weak, and is usually more watchful of the weak binding before the strong, how hereafter in the fencing it can be seen.</p> | ||

| {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 06v.jpg|3|lbl=6v.3}} | | {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 06v.jpg|3|lbl=6v.3}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p><small>[6]</small> | + | | <p><small>[6]</small> With this however the sword fencing and the following written ''Stuck'' is more understandable thus as I explain my ''Zedel'' according to the rules, as I want the words to have understanding so I have named the order; the Beginning, Middle and End.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 06v.jpg|4|lbl=6v.4}} | | {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 06v.jpg|4|lbl=6v.4}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p><small>[7 | + | | <p><small>[7]</small> '''Follow the Sword ''Zedel'''''</p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<p>'''The Four Main guards'''</p> | <p>'''The Four Main guards'''</p> | ||

| Line 3,522: | Line 3,519: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p><small>[ | + | | <p><small>[8]</small> '''The Eight Secondary Guards'''</p> |

<p>Long Point, Iron Gate, Hanging Point, Speak Window, Key, Side Guard, Barrier Guard, Wrath Guard</p> | <p>Long Point, Iron Gate, Hanging Point, Speak Window, Key, Side Guard, Barrier Guard, Wrath Guard</p> | ||

| Line 3,529: | Line 3,526: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p><small>[ | + | | <p><small>[9]</small> '''The Five Master-Cuts'''</p> |

<p>Wrath Cut, Crooked Cut, Thwart Cut, Squinting Cut, Scalper</p> | <p>Wrath Cut, Crooked Cut, Thwart Cut, Squinting Cut, Scalper</p> | ||

| Line 3,536: | Line 3,533: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p><small>[ | + | | <p><small>[10]</small> '''The Six Covert Cuts'''</p> |

<p>Blinding Cut, Bouncing Cut, Short Cut, Knuckle Cut, Clashing Cut, Wind Cut</p> | <p>Blinding Cut, Bouncing Cut, Short Cut, Knuckle Cut, Clashing Cut, Wind Cut</p> | ||

| Line 3,543: | Line 3,540: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | | <p><small>[ | + | | <p><small>[11]</small> '''Handworks in the Sword'''</p> |

<p>Bind On, Remain, Cut, Strike Around, Travel After, Snap Around, Run Off, Doubling, Leading, Flying, Feeling, Circle, Looping, Winding, Winding Through, Reverse, Change Through, Run over, Set Off, Cut Off, Pull, Hand Press, Displace, Hanging, Blocking, Barring, Travel out, Grab over, Weak pushing</p> | <p>Bind On, Remain, Cut, Strike Around, Travel After, Snap Around, Run Off, Doubling, Leading, Flying, Feeling, Circle, Looping, Winding, Winding Through, Reverse, Change Through, Run over, Set Off, Cut Off, Pull, Hand Press, Displace, Hanging, Blocking, Barring, Travel out, Grab over, Weak pushing</p> | ||

| Line 3,549: | Line 3,546: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan=" | + | | rowspan="3" | [[File:MS A.4º.2 07v.jpg|400px|center]] |

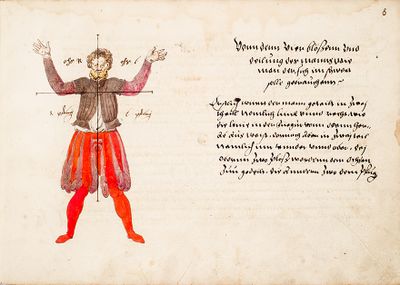

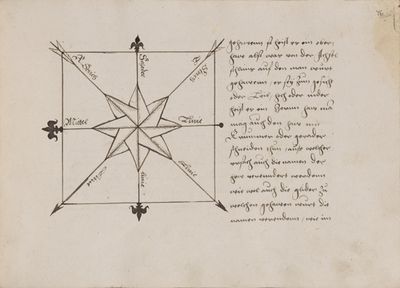

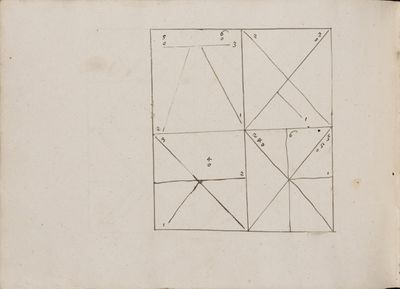

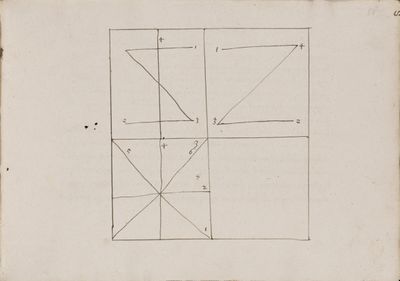

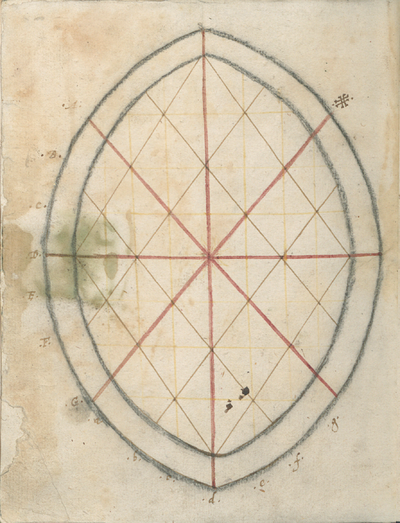

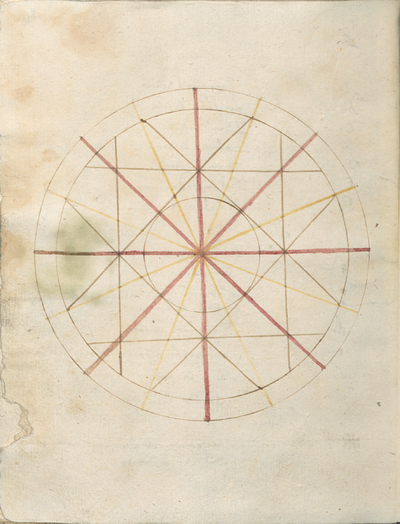

| − | | <p><small>[ | + | | <p><small>[12]</small> '''From the Four Openings and Divisions'''</p> |

| − | <p>Firstly will the opponent be divided in two sections, namely left and right, how the lines in the figure above is shown, thereafter in two more divisions namely under and over, the above two openings would be the Ox, to divide the under two, the Plow. | + | <p>Firstly will the opponent be divided in two sections, namely left and right, how the lines in the figure above is shown, thereafter in two more divisions namely under and over, the above two openings would be the Ox, to divide the under two, the Plow.</p> |

| {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 07v.jpg|1|lbl=7v.1}} | | {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 07v.jpg|1|lbl=7v.1}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | <p><small>[13]</small> Whose use one should thus firstly note, in which division he leads his sword under or above, to the right or the left/ when you have seen that, thus attack against him at once from above, it is about the location, otherwise, take a general example of this:</p> | ||

| + | | {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 07v.jpg|2|lbl=7v.2}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| <p><small>[14]</small> In ''Zufechten'', thus both of you have come together, and you see that he leads his sword to his right in the high opening, in Ox or Wrath Guard, thus attack in to his lower left opening, if not, then it is much more important that you provoke him to meet you. As soon as this clashes, or will, thus pull around your head and strike him high to the opening from which he came. This is namely to his right ear, with the half edge and crossed hands. This is the correct Squinting Cut.</p> | | <p><small>[14]</small> In ''Zufechten'', thus both of you have come together, and you see that he leads his sword to his right in the high opening, in Ox or Wrath Guard, thus attack in to his lower left opening, if not, then it is much more important that you provoke him to meet you. As soon as this clashes, or will, thus pull around your head and strike him high to the opening from which he came. This is namely to his right ear, with the half edge and crossed hands. This is the correct Squinting Cut.</p> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 07v.jpg| | + | {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 07v.jpg|3|lbl=7v.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 08r.jpg|1|lbl=8r.1|p=1}} |

|- | |- | ||

| Line 4,221: | Line 4,222: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:MS A.4º.2 40r.jpg|400px|center]] |

| <p><small>[115]</small> '''Over-gripping'''</p> | | <p><small>[115]</small> '''Over-gripping'''</p> | ||

| Line 4,228: | Line 4,229: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | <p><small>[116]</small> '''A Sword Taking'''</p> | |

<p>Mark when one strongly binds to you on the blade, so remove your left hand from the pommel and grab there with both blades in the middle, and drive with the haft or pommel over besides his both arms. Pull to you, thus must he lose his sword.</p> | <p>Mark when one strongly binds to you on the blade, so remove your left hand from the pommel and grab there with both blades in the middle, and drive with the haft or pommel over besides his both arms. Pull to you, thus must he lose his sword.</p> | ||

| − | + | | {{paget|Page:MS A.4º.2|40v|jpg}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 4,760: | Line 4,761: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[80]</small> Diligently cut the strikes once or more, one after another always through a line, twice namely once from above and again from below with the short edge, thus with this changing you can break the guards and strikes.</p> | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 65r.jpg|3|lbl=65r.3|p=1}} {{paget|Page:MS A.4º.2|65v|jpg|p=1}} | {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 65r.jpg|3|lbl=65r.3|p=1}} {{paget|Page:MS A.4º.2|65v|jpg|p=1}} | ||

| Line 5,282: | Line 5,283: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p><small>[87]</small> Item: Hold you cloak long and when he cuts at you, thus strike with the cape around his blade and spring to him with striking. Thus you yourself will fight.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS A.4º.2 89v.jpg|3|lbl=89v.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 5,311: | Line 5,312: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Meyer 1570 | + | | [[File:Meyer 1570 Title.png|center|400px]] |

| <p>{{red|b=1|Thorough Descriptions of the free Knightly and}}''' Noble Art of Fencing, with various Custom'''ary Weapons, with many beautiful and useful illustrated Figures affected and presented.'''<br/><br/></p> | | <p>{{red|b=1|Thorough Descriptions of the free Knightly and}}''' Noble Art of Fencing, with various Custom'''ary Weapons, with many beautiful and useful illustrated Figures affected and presented.'''<br/><br/></p> | ||

| Line 5,320: | Line 5,321: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Meyer 1570 Crest. | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Meyer 1570 Crest.png|center|400px]] |

| | | | ||

| {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/8|1|lbl=a2r.1}} | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/8|1|lbl=a2r.1}} | ||

| Line 5,367: | Line 5,368: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/13|2|lbl=a4v.1}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 5,461: | Line 5,462: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/21|3|lbl=b4v.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 5,557: | Line 5,558: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>Such input I have seen fit to make for purposes of clearer understanding, so that with this Book each onward going shall become easier to understand, thus easier to modify, and thus initially to learn, and thus I shall see such Knightly arts grow onward, and will now with the first Letter of this chapter, whose first purpose is to teach usefulness, instruct by moving on to present the Four Targets.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/25|3|lbl=Ⅰ.2v.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 5,602: | Line 5,603: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>The means to learn what follows from the Stances, Strikes, and Targets is undertaken here more easily, in that these descriptions and presentations are enough for one to flow on.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/28|3|lbl=Ⅰ.4r.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 5,669: | Line 5,670: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>The fourth is the Weak, through which Changing, Rushing, Slinging, and similar such will duly be used in fencing, of which in what follows there will be many examples and pieces.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/30|6|lbl=Ⅰ.5r.6}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 5,837: | Line 5,838: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>Now much has been said about this art’s start, namely the pre-fencing against your opponent, which faces off through the Stances to the Strikes. Now the rest of the art will follow and we will move onto other parts, and in due form onto the next chapter, which is Of The Strikes.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/40|4|lbl=Ⅰ.10r.4}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 6,019: | Line 6,020: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/50|2|lbl=Ⅰ.15r.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 6,345: | Line 6,346: | ||

<section end="Einlauffen"/> | <section end="Einlauffen"/> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>What the dear reader heard only up until now, on knowing how to engage your opponent with the strikes, moving also through the middle where you will want to come further in the handwork without damage, is meanwhile however not enough without the third, which will be making a good withdrawal. Thus I will give you proper and clear direction in Withdrawing in the following chapter.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/66|1|lbl=Ⅰ.23r.1}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 6,383: | Line 6,384: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>While you will bring all this with you, in this section you will be instructed on his point, such that enough can and will be retained.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/67|2|lbl=Ⅰ.23v.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 6,418: | Line 6,419: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>The steps are done in three different ways, firstly backward and forward, what these are can’t be clarified much as one namely steps to or from someone. The other ones are the steps to the sides which are delineated through a triangle, namely thus: Stand in a straight line with your right foot before your opponent, and with the left behind the right step toward his left, this is the first. The second which is done double you do thus: Step as before with the right foot against his left, then follow with the left behind the right somewhat to the side to his left, and then again with the right farther to his left. The third type is the broken or stolen steps, these are accomplished thus, stand yourself as if you would step forward with your right foot, but as and when you go low, then step back with it behind the other foot. Since these are the same as described in Rapier, I will thus leave it for now.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/68|2|lbl=Ⅰ.24r.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 6,478: | Line 6,479: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>The expression “Intus” and what it means I will let remain Latin, however the expression “Indes” (Just As) is a good German expression and has in itself an important meaning to handy application, that one always and quickly take care, as in when you at first slash to the left, to then at the same time observe the opening to the right, then thirdly on to make sure that you attain the observed opening, where or with what actions you want to come unto it, that you don’t then make openings for your opponent and take damage. Thus retain the meaning of “Just As” so that you observe sharply, which can be much observing and undertaking, also seek to learn faking to your opponent sufficiently, since he needs to have senses in his part, and similarly what Openings you will bring, and where you will be open. Then in all these things to which the expression “Just As” has meaning, stands the whole art of fencing (as Liechtenauer said) and where you don’t undertake such to carefully and securely drive all strikes, will you advance lightly to your damage, as then all fencers will observe, which one thus overpowers and (as one said) tops out and nullifies as wanted.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/70|3|lbl=Ⅰ.25r.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 6,521: | Line 6,522: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>In the pre-fencing come into the right Changer, pay attention that as soon as his sword shows bearing to strike, then before him nimbly strike through above you, and strike with a Traverse from your right at the same time as his, in the strike step on to his left side, if he drives his strike directly at your head, then hit with your Traverse to his left ear, however mark that he doesn’t strike straight to your head by winding his strike with the long edge against your Traverse in the displacement, thus pull the strike with a long Traverse nimbly to his right ear, step just then with your left foot to his right, now you have attacked out of the change with two traverse strikes to each side over against the other. This you take now from the first part to this attack. Forward you will step on to Middle work, then bring yourself to the other part thus, if he slashes from your sword over to the other side, then move after him with a cut against his arm, hit with the strong of your blade, or with your hilt in a jerk away from you, just as he still threatens from the thrust, and still has not yet reached you, then drive to rush out with crossed arms and slash him with the short edge over his right arm to his head; and so that when he reaches you from the thrust, but where he stops you and sweeps away through displacing, then let your sword fly off again, and traverse to his left ear while you step away with your left foot; or where he doesn’t go off or slash around, but stays with the cut or long edge outward, then loop your sword so that your half edge comes at his, ride his sword thus on your right side, but just then let it clip off into the air, so that your hands come together again crosswise high over your head, to then slash him as before, as he reaches from the ride with the short edge over his head, step back following with the left foot, and strike a high traversing middle strike with the long edge from your right to his half, and just as it glides, then pull off to your right with a high strike. Thus you see now how there’s always one part after the other, the application and ordering through must be conceived and executed together, which makes up an entire part of Fencing. Lastly mark here also that the entire engagement can be completed in two or three strikes, where you rush to engage in the first strike, and with the second strike off again and in this strike commit either to the first or last meeting, which needs to be undertaken correctly, or you will lead on there to a third strike. Namely engage with the first, follow after with a second, but when the proper time such must be shown, that you have something worth saying, then mark how one speaks such that you will learn yourself, after which you will learn all other parts in fencing and here on retain your lessons with diligence.</p> | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/72|4|lbl=Ⅰ.26r.4|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf|73|lbl=Ⅰ.26v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/72|4|lbl=Ⅰ.26r.4|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf|73|lbl=Ⅰ.26v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 6,604: | Line 6,605: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>Thus you understand that the third part of fencing is nothing other than the right Practice, as was reported above, the first two Lead parts in fencing, which will be taught though Practice, where you change at every opportunity, namely in the first Lead Part with the stances and strikes, flowing off, changing through, flying off, and letting miss. That such strikes can be trapped with displacement and clearing, likewise in the second Lead Part, displacement, teach the Practice of how you displace, follow after him, cut, punch, etc. Therewith you will end the strikes that he sends to you, or at the least prevent them from reaching their intended destination. And that is the sum of all Practice, namely that you firstly engage your opposing fencer through the stances, with manly strikes and without damage to your target, by showing cunning and agile misleading as can be shown, and after you then engage him to break through with the obligatory or similar handwork, from which you either securely withdraw at your pleasure, or where he must retreat from you and you follow ahead after him. Since going forward such Practice will be needed and extended in many arts to be the same both in name and in fencing, as you found fully described before here in the handwork chapter, I will now drive further to describe fencing from the stances.</p> | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/80|3|lbl=Ⅰ.30r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/81|1|lbl=Ⅰ.30v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/80|3|lbl=Ⅰ.30r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/81|1|lbl=Ⅰ.30v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 6,925: | Line 6,926: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/108|2|lbl=Ⅰ.44r.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 8,023: | Line 8,024: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/149|3|lbl=Ⅰ.64v.3}} | |

| − | + | | | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 8,056: | Line 8,057: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>When he will almost run in at you<br/>Drive him from you with your point,<br/>But if he has run in on you,<br/>With gripping, wrestling, you shall be the first,<br/>Pay heed indeed to forte and foible,<br/>Meanwhile, the openings he makes open,<br/>Also step rightly in the Vor and Nach.<br/>Note diligently the correct time<br/>And do not be quick to be scared.</p> | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/150|3|lbl=Ⅰ.65r.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 8,090: | Line 8,091: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/153|2|lbl=Ⅱ.1v.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 8,118: | Line 8,119: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/154|3|lbl=Ⅱ.2r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/155|1|lbl=Ⅱ.2v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/154|3|lbl=Ⅱ.2r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/155|1|lbl=Ⅱ.2v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 8,212: | Line 8,213: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/166|3|lbl=Ⅱ.8r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/167|1|lbl=Ⅱ.8v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/166|3|lbl=Ⅱ.8r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/167|1|lbl=Ⅱ.8v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 8,341: | Line 8,342: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/179|3|lbl=Ⅱ.14v.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/180|1|lbl=Ⅱ.15r.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/179|3|lbl=Ⅱ.14v.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/180|1|lbl=Ⅱ.15r.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 8,360: | Line 8,361: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/180|2|lbl=Ⅱ.15r.2|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf|181|lbl=Ⅱ.15v|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/182|1|lbl=Ⅱ.16r.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/180|2|lbl=Ⅱ.15r.2|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf|181|lbl=Ⅱ.15v|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/182|1|lbl=Ⅱ.16r.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 8,416: | Line 8,417: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/186|5|lbl=Ⅱ.18r.5}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 8,439: | Line 8,440: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/187|2|lbl=Ⅱ.18v.2|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf|188|lbl=Ⅱ.19r|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/187|2|lbl=Ⅱ.18v.2|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf|188|lbl=Ⅱ.19r|p=1}} | ||

| Line 8,503: | Line 8,504: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/194|2|lbl=Ⅱ.22r.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 8,605: | Line 8,606: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/205|2|lbl=Ⅱ.27v.2|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf|206|lbl=Ⅱ.28r.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/205|2|lbl=Ⅱ.27v.2|p=1}} {{pagetb|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf|206|lbl=Ⅱ.28r.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 8,694: | Line 8,695: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/215|1|lbl=Ⅱ.32v.1}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 8,793: | Line 8,794: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/221|3|lbl=Ⅱ.35v.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 8,957: | Line 8,958: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/232|2|lbl=Ⅱ.41r.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 9,011: | Line 9,012: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/236|1|lbl=Ⅱ.43r.1}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 9,074: | Line 9,075: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/240|4|lbl=Ⅱ.45r.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/241|1|lbl=Ⅱ.45v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/240|4|lbl=Ⅱ.45r.4|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/241|1|lbl=Ⅱ.45v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 9,191: | Line 9,192: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/249|2|lbl=Ⅱ.49v.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 9,225: | Line 9,226: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/252|2|lbl=Ⅱ.51r.2|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/253|1|lbl=Ⅱ.51v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/252|2|lbl=Ⅱ.51r.2|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/253|1|lbl=Ⅱ.51v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 9,255: | Line 9,256: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/254|3|lbl=Ⅱ.52r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/255|1|lbl=Ⅱ.52v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/254|3|lbl=Ⅱ.52r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/255|1|lbl=Ⅱ.52v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 9,309: | Line 9,310: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/259|2|lbl=Ⅱ.54v.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 9,445: | Line 9,446: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/272|2|lbl=Ⅱ.61r.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 9,533: | Line 9,534: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/279|2|lbl=Ⅱ.64v.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 9,572: | Line 9,573: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/280|5|lbl=Ⅱ.65r.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/281|1|lbl=Ⅱ.65v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/280|5|lbl=Ⅱ.65r.5|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/281|1|lbl=Ⅱ.65v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 9,701: | Line 9,702: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/291|2|lbl=Ⅱ.70v.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 9,757: | Line 9,758: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/294|3|lbl=Ⅱ.72r.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 10,347: | Line 10,348: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/351|2|lbl=Ⅱ.100v.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 10,538: | Line 10,539: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/365|2|lbl=Ⅱ.107v.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 10,953: | Line 10,954: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | rowspan="2 | + | | rowspan="2" | [[File:Meyer 1570 Dagger E.png|400px|center]] |

| | | | ||

| {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/395|1|lbl=Ⅲ.15v.1}} | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/395|1|lbl=Ⅲ.15v.1}} | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/395|2|lbl=Ⅲ.15v.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 11,367: | Line 11,368: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | <p>'''Another from the going through.'''</p> | |

<p>Drive again through his staff as before, once, twice, and when he makes the slightest mistake, then fall through below his staff, and quickly tear out his staff downward from your right toward your left, and let your staff go around your head, and strike long with one hand. But before I finish with this weapon, I will also run over and go through the others, because without it these three weapons fence from one ground.</p> | <p>Drive again through his staff as before, once, twice, and when he makes the slightest mistake, then fall through below his staff, and quickly tear out his staff downward from your right toward your left, and let your staff go around your head, and strike long with one hand. But before I finish with this weapon, I will also run over and go through the others, because without it these three weapons fence from one ground.</p> | ||

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/426|2|lbl=Ⅲ.31r.2}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 11,560: | Line 11,561: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/441|4|lbl=Ⅲ.38v.4}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 11,613: | Line 11,614: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | [[File:Meyer 1570 | + | | [[File:Meyer 1570 Title.png|400px|center]] |

| | | | ||

| {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/444|1|lbl=Ⅲ.40r.1}} | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/444|1|lbl=Ⅲ.40r.1}} | ||

| Line 11,701: | Line 11,702: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/450|3|lbl=Ⅲ.43r.3}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 11,826: | Line 11,827: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

{{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/458|3|lbl=Ⅲ.47r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/459|1|lbl=Ⅲ.47v.1|p=1}} | {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/458|3|lbl=Ⅲ.47r.3|p=1}} {{section|Page:Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (Joachim Meÿer) 1570.pdf/459|1|lbl=Ⅲ.47v.1|p=1}} | ||

| Line 11,929: | Line 11,930: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | [[File:MS Var.82 005r.png|400px|center]] | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{paget|Page:MS Var.82|005r|png|lbl=5r}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 12,616: | Line 12,617: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | | |

| − | + | | {{section|Page:MS Var.82 126r.png|3|lbl=-|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS Var.82 126v.png|1|lbl=126v|p=1}} {{section|Page:MS Var.82 127r.png|1|lbl=127r|p=1}} | |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 12,640: | Line 12,641: | ||

{{sourcebox | {{sourcebox | ||

| work = 1570 Figures | | work = 1570 Figures | ||

| − | | authors = [[ | + | | authors = [[Hans Christoff Stimmer]] |

| source link = https://digital.ub.uni-leipzig.de/object/viewid/0000009663 | | source link = https://digital.ub.uni-leipzig.de/object/viewid/0000009663 | ||

| source title= Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig | | source title= Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig | ||

Latest revision as of 21:43, 15 June 2025

|

Caution: Scribes at Work This article is in the process of updates, expansion, or major restructuring. Please forgive any broken features or formatting errors while these changes are underway. To help avoid edit conflicts, please do not edit this page while this message is displayed. Stay tuned for the announcement of the revised content! This article was last edited by Michael Chidester (talk| contribs) at 21:43, 15 June 2025 (UTC). (Update) |

| Joachim Meyer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August(?) 1537 Basel, Germany |

| Died | February 1571 (aged 33) Schwerin, Germany |

| Spouse(s) | Appolonia Ruhlman |

| Occupation |

|

| Citizenship | Strasbourg |

| Patron |

|

| Movement | Freifechter |

| Influences | |

| Influenced | |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | Early New High German |

| Notable work(s) | Gründtliche Beschreibung der... Kunst des Fechtens (1570) |

| Manuscript(s) |

|

| First printed english edition |

Forgeng, 2006 |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | |

| Signature | |

Joachim Meyer (〰 16 Aug 1537, † Feb 1571)[1] was a 16th century German cutler, Freifechter, and fencing master. He was the last major figure in the tradition of the German grand master Johannes Liechtenauer, and in the later years of his life he devised at least four distinct fencing manuals. Meyer's writings incorporate both the traditional Germanic technical syllabus and contemporary systems that he encountered in his travels, including Italian rapier fencing. In addition to his fencing practice, Meyer was a Burgher, master cutler, and eventual officer of the local Smith's Guild.[2]

Meyer was born in Basel,[3] where he presumably apprenticed as a cutler. Records show that by 4 June 1560 he had settled in Strasbourg, where he married Appolonia Ruhlman (Ruelman)[4] and was granted the rank of master cutler. His interests had already moved beyond smithing, however, and in 1561, Meyer's petition to the City Council of Strasbourg for the right to hold a Fechtschule was granted. He would repeat this in 1563, 1566, 1567 and 1568;[5] the 1568 petition is the first extant record in which he identifies himself as a fencing master.

Meyer probably wrote his first manuscript (MS Bibl. 2465) in 1561 for Georg Johann Ⅰ, Count Palatine of Veldenz,[6] and his second (MS A.4º.2) some time between 1560 and 1568 for Otto (later Count of Solms-Sonnewalde).[7] Both of these manuscripts contain a series of lessons on training with long sword, dusack, and rapier; the 1561 also covers dagger, polearms, and armored fencing. His third manuscript (MS Var.82), produced in the 1560s, is of a decidedly different nature. Like many fencing manuscripts from the previous century, it is an anthology of treatises by a number of prominent German masters including Sigmund ain Ringeck, pseudo-Peter von Danzig, and Martin Syber, and also includes a brief outline by Meyer himself on a system of rapier fencing based on German Messer teachings and the teachings of Stephen Heinrich, Count of Eberstein.

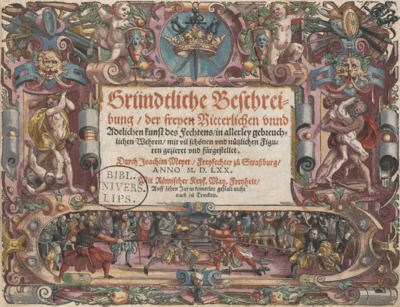

Finally, on 24 February 1570, Meyer completed an enormous treatise entitled Gründtliche Beschreibung, der freyen Ritterlichen unnd Adelichen kunst des Fechtens, in allerley gebreuchlichen Wehren, mit vil schönen und nützlichen Figuren gezieret und fürgestellet ("A Foundational Description of the Free, Chivalric, and Noble Art of Fencing, Showing Various Customary Defenses, Affected and Put Forth with Many Handsome and Useful Drawings"); it was dedicated to Johann Casimir, Count Palatine of Simmern,[6] and illustrated at the workshop of Hans Christoff Stimmer. It contains all of the weapons of the 1561 and '68 manuscripts apart from fencing in armor, and dramatically expands his teachings on each.

Unfortunately, Meyer's writing and publication efforts incurred significant debts (about 300 crowns), which Meyer pledged to repay by Christmas of 1571.[4] Late in 1570, Meyer accepted the position of Fechtmeister to Duke Johann Albrecht of Mecklenburg at his court in Schwerin. There Meyer hoped to sell his book for a better price than was offered locally (30 florins). Meyer sent his books ahead to Schwerin, and left from Strasbourg on 4 January 1571 after receiving his pay. He traveled the 800 miles to Schwerin in the middle of a harsh winter, arriving at the court on 10 February 1571. Two weeks later, on 24 February, Joachim Meyer died. The cause of his death is unknown, possibly disease or pneumonia.[5]

Antoni Rulman, Appolonia’s brother, became her legal guardian after Joachim’s death. On 15 May 1571, he had a letter written by the secretary of the Strasbourg city chamber and sent to the Duke of Mecklenburg stating that Antoni was now the widow Meyer’s guardian; it politely reminded the Duke who Joachim Meyer was, Meyer’s publishing efforts and considerable debt, requested that the Duke send Meyer’s personal affects and his books to Appolonia, and attempted to sell some (if not all) of the books to the Duke.[4]

Appolonia remarried in April 1572 to another cutler named Hans Kuele, bestowing upon him the status of Burgher and Meyer's substantial debts. Joachim Meyer and Hans Kuele are both mentioned in the minutes of Cutlers' Guild archives; Kuele may have made an impression if we can judge that fact by the number of times he is mentioned. It is believed that Appolonia and either her husband or her brother were involved with the second printing of his book in 1600. According to other sources, it was reprinted yet again in 1610 and in 1660.[8][9]

Contents

- 1 Treatises

- 2 Temporary section break

- 2.1 Gründtliche Beschreibung der… Kunst des Fechtens (1570)

- 2.1.1 Introduction

- 2.1.2 Sword

- 2.1.2.1 Introduction

- 2.1.2.2 1 - Of Man and His Divisions

- 2.1.2.3 2 - Of the Sword and Its Divisions

- 2.1.2.4 3 - Of the Stances or Guards

- 2.1.2.5 4 - Of the Strikes

- 2.1.2.6 5 - Of Displacing

- 2.1.2.7 6 - Of the Withdrawal

- 2.1.2.8 7 - A Lesson in Stepping

- 2.1.2.9 8 - Of Before, After, During, and Indes

- 2.1.2.10 9 - A Guide to the Elements

- 2.1.2.11 10 - How One Shall Fence to the Four Openings

- 2.1.2.12 11 - Fencing from the Stances

- 2.1.2.13 Part Three

- 2.1.3 Dusack

- 2.1.3.1 Introduction

- 2.1.3.2 1 - Contents of the Fencing with Dusacks

- 2.1.3.3 2 - Of the Stances or Guards and Their Use

- 2.1.3.4 3 - Of the Four Cuts, with Four Good Rules

- 2.1.3.5 4 - Of the Secondary Cuts

- 2.1.3.6 5 - How One Shall Use the Four Openings

- 2.1.3.7 6 - Of Displacing, and How All Cuts Are Divided into Three Types

- 2.1.3.8 7 - Now Follow the Stances with the Elements

- 2.1.3.9 8 - Of the Watch and the Elements Assigned to It

- 2.1.3.10 9 - Of the Steer with Its Elements

- 2.1.3.11 10 - Of the Wrathful Guard

- 2.1.3.12 11 - The Direct Displacement or the Slice

- 2.1.3.13 12 - How You Shall Fence from the Bow

- 2.1.3.14 13 - Of the Boar

- 2.1.3.15 14 - Of the Middle Guard, and How One Shall Fence from It

- 2.1.3.16 15 - Of the Changer and Its Elements

- 2.1.4 Rapier

- 2.1.4.1 1 - Contents of the Fencing with the Rapier

- 2.1.4.2 2 - Of the Divisions of the Man, and of the Weapon, and of Their Use.

- 2.1.4.3 3 - Of the Guards and Stances of the Rapier

- 2.1.4.4 4 - Of the Classification of the Four Strikes

- 2.1.4.5 5 - Of Thrusting

- 2.1.4.6 6 - A Good Lesson and Rule How One Can Change Strikes into Stabs and Stabs into Strikes

- 2.1.4.7 7 - Of the Misleading

- 2.1.4.8 8 - In This Chapter Will Be Handled Changing, Following After, Staying, Feeling, Twitching, and Winding

- 2.1.4.9 Part Two

- 2.1.4.10 How You Should Use the Weapon Along with a Sidearm

- 2.1.5 Dagger

- 2.1.6 Polearms

- 2.1 Gründtliche Beschreibung der… Kunst des Fechtens (1570)

- 3 Temporary section break

- 4 Additional Resources

- 5 References

Treatises

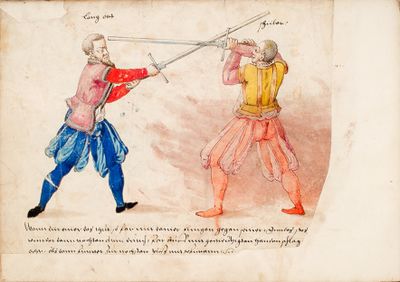

Joachim Meyer's writings are preserved in three manuscripts prepared in the 1560s: the 1561 MS Bibl. 2465 (Munich), dedicated to Georg Johannes von Veldenz; the 1563-68 MS A.4º.2 (Lund), dedicated to Otto von Solms; and the MS Var. 82 (Rostock), which includes notes on the teachings of Stephan Heinrich von Eberstein and which Meyer may have still been working at the time of his death in 1571. The former two manuscripts are substantially similar in text and organization, and it seems clear that the Munich was the basis for the much shorter Lund.

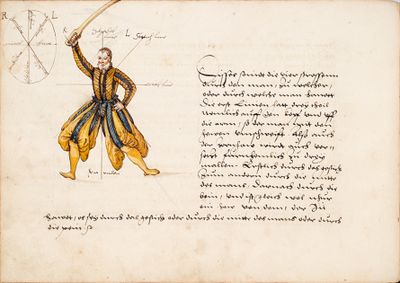

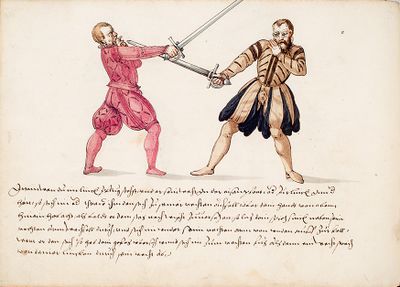

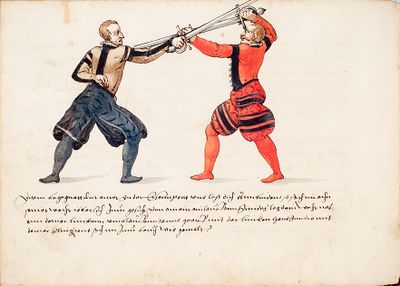

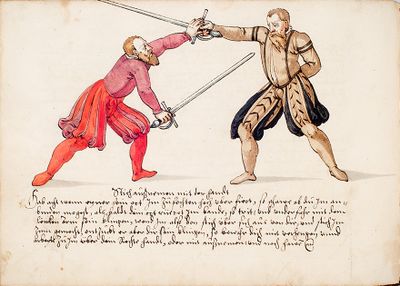

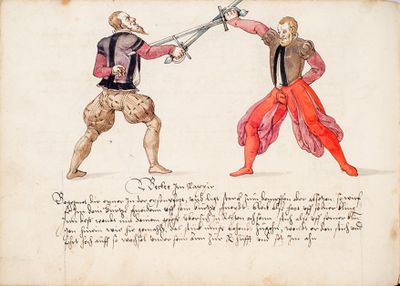

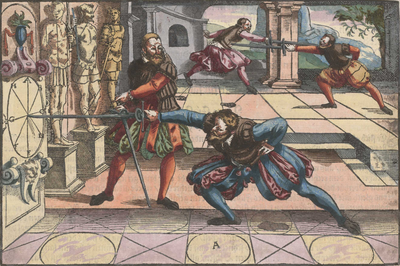

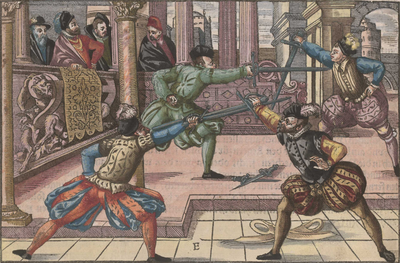

Dwarfing these works is the massive book he published in 1570 entitled Gründtliche Beschreibung der ...Kunst des Fechtens ("A Foundational Description of the... Art of Fencing"), dedicated to Johann Kasimir von Pfalz-Simmern. Meyer's writings purport to teach the entire art of fencing, something that he claimed had never been done before, and encompass a wide variety of teachings from disparate sources and traditions. To achieve this goal, Meyer seems to have constructed his treatises as a series of progressive lessons, describing a process for learning to fence rather than merely outlining the underlying theory or listing the techniques. In keeping with this, he illustrates his techniques with depictions of fencers in courtyards using training weapons such as two-handed foils, wooden dusacks, and rapiers with ball tips.

The first section of Meyer's teachings is devoted to the long sword (the sword in two hands), the traditional centerpiece of the Liechtenauer tradition which Meyer describes as the foundational weapon of his system, and this section devotes the most space to fundamentals like stance and footwork. His long sword system draws upon the teachings of Freifechter Andre Paurenfeyndt (via Christian Egenolff's reprint) and Liechtenauer glossators Sigmund ain Ringeck and Lew, as well as using terminology otherwise unique to the brief Recital of Martin Syber. Not content merely to compile these teachings as his contemporary Paulus Hector Mair was doing, Meyer sought to update—even reinvent—them in various ways to fit the martial climate of the late sixteenth century, including adapting many techniques to accommodate the increased weight and momentum of a greatsword and modifying others to use beats with the flat and winding slices in place of thrusts to comply with street-fighting laws in German cities (and the rules of the Fechtschule).

The second section is designed to address newer weapons gaining traction in German lands, the dusack and the rapier, and thereby find places for them in the German tradition. His early Munich and Lund manuscripts present a more summarized syllabus of techniques for these weapons, while his printed book goes into greater depth and is structured more in the fashion of lesson plans.[10] Meyer's dusack system, designed for the broad-bladed sabers that spread into German lands from Eastern Europe in the 16th century,[11] combines the old Messer teachings of Johannes Lecküchner and the dusack teachings of Andre Paurenfeyndt with other unknown systems (some have speculated that they might include early Polish or Hungarian saber systems). His rapier system, designed for the lighter single-hand swords spreading north from Iberian and Italian lands, seems again to be a hybrid creation, integrating both the core teachings of the 15th century thrust-centruc Liechtenauer tradition as well as components that are characteristic of the various regional Mediterranean fencing systems (including, perhaps, teachings derived from the treatise of Achille Marozzo). Interestingly, Meyer's rapier teachings in the Rostock seem to represent an attempt to unify these two weapon systems, outlining a method for rapier fencing that includes key elements of his dusack teachings; it is unclear why this method did not appear in his book, but given the dates it may be that they represent his final musings on the weapon, written in the time between the completion of his book in 1570 and his death a year later.

The third section is omitted from the Lund manuscript but present in the Munich and the 1570, and covers dagger, wrestling, and various pole weapons; to this, the Munich adds a short section on armored fencing. His dagger teachings, designed primarily for urban self-defense, seem to be based in part on the writings of Bolognese master Achille Marozzo,[12] but also include much unique content of unknown origin (perhaps the anonymous dagger teachings in his Rostock manuscript). His staff material makes up the bulk of this section, beginning with the short staff, which, like Paurenfeyndt, he uses as a training tool for various pole weapons (and possibly also the greatsword), and then moving on to the halberd before ending with the long staff (representing the pike). As with the dagger, the sources Meyer based his staff teachings on are largely unknown.

- To view the sword, dusack, and rapier teachings of the Munich and Lund manuscripts side-by-side and study the overlaps and differences, see Joachim Meyer/Manuscript Comparison.

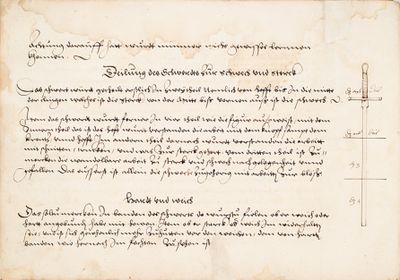

Veldenz Treatise (1561)

Dedication

Illustrations |

Munich Manuscript [edit] | |

|---|---|---|

To the Noble High-born Prince and Lord, Lord Georg Hansen Count Palatine of the Rhine Duke of Bavaria, Count at Veldenz and Lord of Lutzelstein, my gracious Prince and Lord |

[IIIr.1] Dem Durchleuchtigen hochgebornen Fursten vnd Hern, Hern Görg Hansen Pfaltzgraff en bey Rhein Hertzog In Bayern, Graff en zu Veldentz vnd Herren zu Lutzelstein, meinem Gnedigen Fursten vnd Herren. | |

Noble high-born Prince, Your Princely Grace, my submissive obedient willing and diligent service is ready at all times, gracious Lord. The ancient scholars have not in vain made the art of fencing famous with all praise and diligence to all and the same enthusiastic princes and lords imagined especially because of the greater part of chivalrous fights and excellent deeds, hence an origin was taken and credibly told, by which many of the most famous minds are so awakened and strengthened that they may be praised and honored for their high observance and administration of war, and will be magnificent. Therefore, up to the present day, the inspired practice and the art of fencing has not fallen to any decline but has retained its old praises and worthiness by all, the youth are instructed in many noble deeds and practices, solely in accordance with all the arts, intact and undamaged, in the old traditional standings, and have become infatuated. But since I have heard and understood how that Your Princely Grace bears no displeasure to such honorable fencing but much more gracious respect to such fighting Stucken, and how they are not to be divided, and that as such, their virtues are composed in writing, the same to give Your Grace an easy account of all these Stucke, done to keep and retain the much covered arts quite free from defects, in subservience, I shall not spare my diligence, in which, Your Princely Grace, through my submissive means and ways, and as much as I have learned from youth and sought to describe and show here. Which and although it might be a little longer than I myself hoped, and that Your Princely Grace shall forgive and take into account that such multiple works require so much time and effort to write. To this end, it would not be enough that one weapon, two or three is taught and delivered to you, but rather that one Stuck is attached to the other like in a chain, one thing after another is noted, and experience is gained, and one weapon is the teacher of another, I have been caused to assemble the entire fencing art, as if it was very proper and I, in consideration, have ascribed this tract to Your Princely Grace as a princely person, and have produced it solely by the limited Stucken of the same, for Your Princely Grace, giving their proper titles and names, how I know and am obliged to do, also in good part so that the teaching can be clearly understood, and brought to this point, that some Stucken are so completely incomprehensible for and to the hand, that I myself may scarcely understand again their same proper titles and reverence, not to mention where the honorific words should remain, so that it might be of use to someone, that thus not intentionally, but rather without obscuring the art, the pieces have been written with general words. I must show that the understanding is clearly taken without any error, even where one can apply a school law, the following may you learn and understand for yourself, but with what effort and work it will be done, an art that must be arranged and learned in practice alone, delivered here in writing for the eyes, and equally beheld as if they were to be practiced with the hands and the whole body. Put to paper and penned, especially those which were previously attempted and understood by few, I submissively give Your Princely Grace a high princely understanding and a graceful submission for your acceptance, from my slight ability to reveal the fencing arts in an understandable way, and to disclose the same in an intelligible manner sparing neither diligence nor effort (although the same content might be unremarkable). However, Your Princely Grace, I am most hopeful that you will graciously accept and embrace such a work as I have done, which has been carried out according to my will and how then such work has verily flowed from a loyal heart to Your Princely Grace in all possible service and in devoted submissiveness, from me as a faithful servant hereby most diligently commanded in graciousness, dated 7 March 1561. |