|

|

You are not currently logged in. Are you accessing the unsecure (http) portal? Click here to switch to the secure portal. |

Giacomo di Grassi

| Giacomo di Grassi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 16th century Modena, Italy |

| Died | after 1594 London, England |

| Occupation | Fencing master |

| Genres | Fencing manual |

| Language | |

| Notable work(s) | Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l'Arme (1570) |

| First printed english edition |

His True Arte of Defence (1594) |

| Concordance by | Michael Chidester |

| Translations | Český Překlad |

Giacomo di Grassi was a 16th century Italian fencing master. Little is known about the life of this master, but he seems to have been born in Modena, Italy and acquired some fame as a fencing master in his youth. He operated a fencing school in Treviso and apparently traveled around Italy observing the teachings of other schools and masters.

Ultimately di Grassi seems to have developed his own method, which he laid out in great detail in his 1570 work Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l'Arme ("Discourse on Wielding Arms with Safety"). In 1594, a new edition of his book was printed in London under the title His True Arte of Defence; this edition was orchestrated by an admirer named Thomas Churchyard, who hired I. G. to translated it and I. Iaggard to publish it.

Contents

Treatise

This presentation includes a modernized version of the 1594 English translation, which did not follow the original Italian text with exactness. We intend to replace or expand this with a translation of the Italian, when such becomes available.

Figures |

Italian Transcription (1570) |

English Transcription (1594) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Giacomo di Grassi His True Art of Defense, plainly teaching by infallible Demonstrations, apt Figures and perfect Rules the manner and form how a man without other Teacher or Master may handle all sorts of Weapons as well offensive as defensive: With a Treatise Of Deceit or Falsing: And with a way or Means by private Industry to obtain Strength, Judgement, and Activity |

[Ttl] RAGIONE DI ADOPRAR SICVRAMENTE L'ARME SI DA OFFESA, COME DA DIFESA, Con un Trattato dell'inganno, & con un modo di essitarsi da se stesso, per acquistare forza, giudicio, & prestezza, |

[Ttl] Giacomo Di Grassi his true Arte of Defence, plainlie teaching by infallable Demonstrations, apt Figures and perfect Rules the manner and forme how a man without other Teacher or Master may safelie handle all sortes of Weapons as well offensiue as defensiue: VVith a Treatise Of Disceit or Falsinge: And with a waie or meane by priuate Industrie to obtaine Strength, Iudgement and Actiuitie. | |

First written in Italian by the Fore-said Author, And Englished by I. G. gentleman. |

DI GIACOMO DI GRASSI. CON PRIVILEGIO. |

First written in Italian by the foresaid Author, And Englished by I. G. gentleman. | |

Printed at London for I. I. and are to be sold within Temple Barre at the Signe of the Hand and Starre 1594 |

In Uenetia, appresso Giordano Ziletti, & compagni.

|

Printed at London for I. I and are to be sold within Temple Barre at the Signe of the Hand and Starre 1594. | |

|

[i] To the Right Honorable my L. Borrow Lord Gouernor of the Breil, and Knight of the most honorable order of the Garter, T. C. wisheth continuall Honor, worthines of mind, and learned knowledg, with increas of worldlie Fame, & heauenlie felicitie. HAuing a restlesse desier in the dailie exercises of Pen to present some acceptable peece of work to your L. and finding no one thing so fit for my purpose and your honorable disposition, as the knowledge of Armes and Weapons, which defends life, countrie, & honour, I presumed to preferre a booke to the print (translated out of the Italyan language) of a gentle mans doing that is not so gredie of glory as many glorious writers that eagerly would snatch Fame out of other mens mouthes, by a little labour of their own, But rather keeps his name vnknowen to the world (vnder a shamefast clowd of silence) knowing that vertue shynes best & getteth greatest prayes where it maketh smallest bragg: for the goodnes of the mind seekes no glorious gwerdon, but hopes to reap the reward of well doing among the rypest of iudgement & worthiest of sound consideration, like vnto a man that giueth his goods vnto the poore, and maketh his treasurehouse in heauen, And further to be noted, who can tarrie til the seed sowen in the earth be almost rotten or dead, shal be sure in a boūtiful haruest to reap a goodly crop of corne And better it is to abyde a happie season to see how things will proue, than soddainly to seeke profite where slowlye comes commoditie or any benefit wil rise. Some say, that good writers doe purchase small praise till they be dead, (Hard is that opinion.) and then their Fame shal flowrish & bring foorth the fruite that long lay hid in the earth. [ii] This gentleman, perchaunce, in the like regard smothers vp his credit, and stands carelesse of the worlds report: but I cannot see him so forgotten for his paines in this worke is not little, & his merite must be much that hath in our English tongue published so necessarie a volume in such apt termes & in so bigg a booke (besides the liuely descriptions & models of the same) that shews great knowledge & cunning, great art in the weapon, & great suretie of the man that wisely can vse it, & stoutly execute it. All manner of men allowes knowledge: then where knowledge & courage meetes in one person, there is ods in that match, whatsoeuer manhod & ignorance can say in their own behalfe. The sine book of ryding hath made many good hors-men: and this booke of Fencing will saue many mens lyues, or put comon quarrels out of vre, because the danger is death if ignorant people procure a combate. Here is nothing set downe or speach vsed, but for the preseruation of lyfe and honour of man: most orderly rules, & noble obseruations, enterlaced with wise councell & excellent good wordes, penned from a fowntaine of knowledge and flowing witt, where the reasons runnes as freely as cleere water cōmeth from a Spring or Conduite. Your L. can iudge both of the weapon & words, wherefore there needes no more commendation of the booke: Let it shewe it self, crauing some supportation of your honourable sensure: and finding fauour and passage among the wise, there is no doubt but all good men will like it, and the bad sort will blush to argue against it, as knoweth our liuing Lord, who augment your L. in honour & desyred credit. Your L. in all humbly at commaundement. Thomas Churchyard. | |||

The Author's Epistle unto divers Noble men and Gentlemen |

[i] ALLI MOLTO MAG. SIGNORI Il Sig. Camillo, il Sig. Fabritio, il Sig. Girolamo, già del S. Luigi, il S. Liberale, l'uno & l'altro, S. Luigi Renaldi. Il S. Alberto Onigo, il S. Antonio Bressa, il S. Branca Scolari, il Sig. Lione Bosso, il Sig. Giacomo Sugana, il Sig. Bonsembiante, Onigo, già del Sig. Cavallier, il Sig. Ascanio Federici, il Sig. Agostino Bressa, miei Signori Osseruandissimi. |

[iii] The Authors Epistle vnto diuers Noble men and Gentle-men. | |

Among all the prayers, wherein through the whole course of my life, I have asked any great thing at God's hands, I have always most earnestly beseeched, that (although at this present I am very poor and of base fortune) he would notwithstanding give me grace to be thankful, and mindful of the good turns which I have received. For among all the disgraces which a man may incur in this world, there is none in my opinion which causes him to become more odious, or a more enimic to mortal men (yes, unto God himself) than ingratitude. Wherefore being in Treviso, by your honors courteously entreated, and of all honorably used, although I practiced little or nought at all to teach you how to handle weapons, for the which purpose I was hired with an honorable stipend, yet to shew myself in some sort thankful, I have determined to bestow the way how to all sorts of weapons with the advantage and safety. The which my work, because it shall find your noble hearts full of valor, will bring forth such fruit, being but once attentively read over, as that in your said honors will be seen in acts and deeds, which in other men scarcely is comprehended by imagination. And I, who have been and am most fervently affected to serve your lords, for as much as it is not granted unto me, (in respect of your divers affairs) to apply the same, and take some pains in teaching as I always desired, have yet by this other way, left all that imprinted in your noble minds, which in this honorable exercise may bring a valiant man unto perfection. |

FRA TVTTI i preghi che io per tut to il corso della mia uita ho chiesti a Dio maggiori, di quest'uno l'ho sempre caldamente supplicato. Che quan tunque io mi troui per hora in assai debbole & bassa fortuna, egli nondimeno mi conceda gratia di potermi mostrare grato & cortese de' fauori & beneficii riceuuti. Parendomi che fra tutte le brutture, nelle quali puote l'huomo incorrere in questo mondo, niuna ue ne sia, che piu odioso lo faccia, & inimico a' mortali, & a Dio istesso, che la ingratitudine. Onde essendo io stato dalle Signorie Vostre raccolto in Treuiso, & cortese & honora-tamente trattato da tutti, come che io poco o nulla mi a-doprassi in insegnarle la ragion dell'armi, a che ero da quel-le con honorato stipendio condotto, per dimostrar in parte la gratitudine dell'animo mio, ho deliberato donarle que- [ii] sta mia opera, nella qual mi sforzo di insegnare il modo di adoprar tutte le forte d'armi con auantaggio & sicuramente: la qual, perche trouerà i cuori uostri pieni di ualore, produrrà tal frutto, essendo una uolta letta con attentione, che nelle Signorie Vostre si uedrà quello in fatto, che in altrui à gran pena con l'imaginatione si comprende. Et io che sono stato & son ardentissimo di seruirle, non mi essendo stato concesso per molti suoi affari, di affaticarmi in esercitarle come era il desiderio mio, haurò con quest’altra uia lasciato ne i nobilissimi animi uostri impresso tutto quello che può in quest'honorato essercitio ridurre un'huomo ualoroso a perfettione. |

AMong all the Prayers, wherein through the whole course of my life, I haue asked any great thing at Gods hands, I haue alwayes most earnestly beseeched, that (although at this present I am verie poore and of base Fortune) he would notwithstanding giue me grace to be thankefull and mindfull of the good turnes which I haue receiued. For among all the disgraces which a man may incurre in this world, there is none in mine opinion which causeth him to become more odious, or a more enimie to mortall men (yea, vnto God himselfe) than ingratitude. VVherefore being in Treuiso, by your honours courteously intreated, and of all honourably vsed, although I practised litle or nought at all to teach you how to handle weapons, for the which purpose I was hyred with an honourable stipend, yet to shewe my selfe in some sort thankefull, I haue determined to bestowe this my worke vpon your honours, imploying my whole indeuour to shewe the way how to handle all sortes of weapons with aduantage and safetie. The which my worke, because it shall finde your noble hearts full of valure, will bring foorth such fruite, being but once attentiuely read ouer, as that in your said honors will be seene in actes and deedes, which in other men scarsely is comprehended by imagination. And I, who haue beene and am most feruently affected to serue your Ls. forasmuch as it is not graunted vnto me, (in respect of your diuers affaires) to applie the same, and take some paines inteaching as I alwaies desired, haue yet by this other waie, left all that imprinted in your noble mindes, which in this honourable exercise may bring a valiant man vnto perfection.

| |

Therefore I humbly beseech your honors, that with the same liberal minds, with the which you accepted of me, your Ls will also receive these my endeavors, and vouchsafe so to protect them, as I have always, and will defend your honors most pure and undefiled. Wherein, if I perceive this my first childbirth (as I have only published it to the intent to help and teach others) to be to the general satisfaction of all I will so strain my endeavors in another work which shortly shall shew the way both how to handle all those weapons on horseback which here are taught on foot, as also all other weapons whatsoever. Your honours most affectionate servant, Giacomo di Grassi of Medena |

Supplico dunque le Signorie uostre, che con quell'animo liberale, che accettorono me, riceuano questa mia fatica, havendola in quella protettione che io ho sempre hauuto & haurò il chiarissimo honor delle Signorie uostre: che se io conoscerò questo mio primiero parto, si come io l'ho solamente per giouare & insegnare publicato, sia di uniuersale sodisfattione, mi sforzerò in un'altro, & fra poco tempo, insegnare il modo di adoprar a cauallo tutte quelle sorti d'armi, che qui s'insegnano a piede, & dell'altre ancora. Di Venetia, adi 8. Marzo. 1570. Di VV. SS. Seruitor Affettionatissimo

|

Therefore I humbly beseech your honours, that with the same liberall mindes, with the which you accepted of mee, your Ls: will also receiue these my indeuours, & vouchsafe so to protect them, as I haue alwaies, and wil defend your honours most pure and vndesiled. VVherein, if I perceiue this my first childbirth (as I haue only published it to thentent to help & teach others) to be to the generall satisfaction of all I will so straine my endeuours in an other worke which shortly shall shew the way both how to handle all those weapons on horse-backe which here are taught on foote, as also all other weapons whatsoeuer. Your honours most affectionate seruant.

| |

[iii] A I LETTORI. SI COME dalle fascie portiamo con noi un quasi sfrenato desiderio di sapere, cosi da l'esser po fatti ragioneuoli nasce in noi una lodeuole & ardente uoglia d'insegnare, il che quando non fosse non si uedrebbe perauentura il mondo di tante arti e scienze ripieno. |

[iv] The Author, to the Reader. EVen as from our swathing bands wee carrie with vs (as it were) an vnbridled desire of knowledge: So afterwardes, hauing attained to the perfection therof, there groweth in vs a certaine laudable and feruent affection to teach others: The which, if it were not so, the world happily should not be seene so replenished with Artes and Sciences. | ||

|

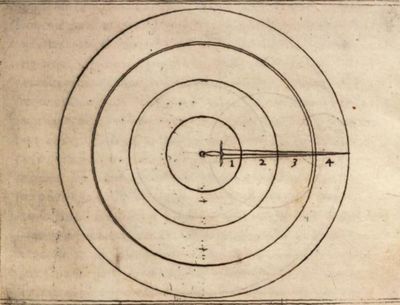

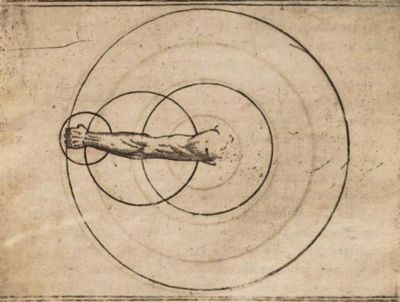

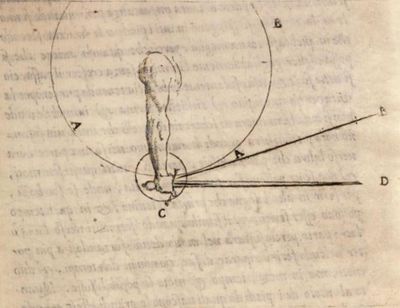

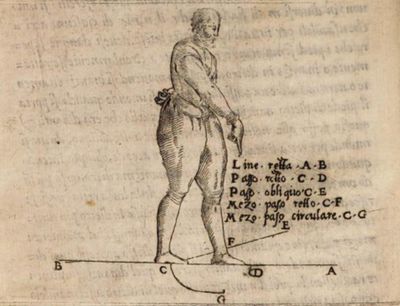

Percio che non essendo tutti gli huomini atti alla contemplatione & inuestigatione delle cose, nè meno a ciascuno concessa da Dio la gratia di poter con la mente leuarsi da terra, & inuestigando trouar le cause delle cose, & quelle compartir a quelli che meno uolentieri s'affaticana; accaderebbe che una parte de gli huomini a guisa di Signori & padroni dominarebbono, & gli altri come serui uilissimi in perpetue tenebre auolti tolererebbono una uita indegna dell'humana conditione. La onde al parer mio è cosa ragioneuole far, altrui partecipe di quello che si ha con molto studio & fatica inuestigando ritrouato. Sendo dunque io sin da fanciullo sommamente dilettato del maneggio dell'armi, dopo l'hauer molto tempo esercitato il corpo in esse, ho uoluto uedere i piu eccellenti maestri di quest'arte, i quali ho auertito hauere tutti, modi diuersi di insegnare l'uno da l'altro molto differenti, quasi che questo mestiero fosse senza ordine & regola, & dipendesse tutto dal ceruello, & ghiribizzo di chi ne fa professione, nè fosse possibile in quello esercitio tanto honorato ritrouarsi, come in tutte l'altre arti e scienze, una sola uia buona e uera, col mezo della quale si potesse hauere intera cognitione di quanto si puo far con l'armi, senza lam bicarsi tutto dì il ceruello ad imparar hoggi un colpo da un maestro, diman da un'altro, affaticandosi d'intorno a i particolari, la cognitione de' quali è infinita, & per ciò impossibile. Però da honesto desio di giouare sospinto, tutto a questa contemplatione mi diedi, con speranza quando che fosse di poter ritrouare i principii & le uere cagioni di questa arte, & in poca somma & certo ordine ridurre il confuso & infinito numero de' colpi: i quali principii essendo pochi, & per ciò facili ad esser da qualunque persona intesi & collocati nella memoria; senza alcun dubio in poco tempo & con poca fatica apriranno una larghissima strada a saper tutto quello che in essa arte si contiene. Nè sono di ciò, si come io stimo, punto rimaso ingannato: percioche al fine dopo molto pensare [iv] ho ritrouato questa uera arte, dalla qual sola dipende la cognitione di quanto si puo far con l'armi in mano; non tanto di quelle che hoggidì si trouano, ma di quelle ancora che si troueranno nel tempo auenire, essendo ella fondata su la offesa & difesa, ambedue le quali si fanno nella linea retta e circulare, che in altro modo non si puo offendere nè difendere. |

For if men generally were not apt to contemplation and searching out of things: Or if God had not bestowed vpon euery man the grace, to be able to lift vp his minde from the earth, and by searching to finde out the causes thereof, and to imparte them to those who are lesse willing to take any paines therein: it would come to passe, that the one parte of men, as Lordes and Masters, should beare rule, and the other parte as vyle slaues, wrapped in perpetuall darknesse, should suffer and lead a life vnworthie the condition of man. Wherefore, in mine opinion it standes with great reason that a man participate that vnto others which he hath searched and found out by his great studie & trauaile. And therefore, I being euen from my childhood greatly delighted in the handling of weapons: after I had spent much time in the exercise thereof, was desyrous to see and beholde the most excellent and expert masters of this Arte, whome I haue generally marked, to teach after diuers wayes, much differing one from another, as though this misterie were destitute of order & rule, or depended onely vpon imagination, or on the deuise of him who professeth the same: Or as though it were a matter impossible to find out in this honourable exercise (as well as in all other Artes and Sciences) one onely good and true way, whereby a man may attaine to the intire knowledge of as much as may be practised with the weapon, not depending altogether vpon his owne head, or learning one blowe to day of one master, on the morowe of another, thereby busying himselfe about perticulars, the knowledge whereof is infinite, therefore impossible. Whereupon being forced, through a certaine honest desire which I beare to helpe others, I gaue my selfe wholy to the con- [v] templation thereof: hoping that at the length, I shoulde finde out the true principles and groundes of this Arte, and reduce the confused and infinite number of blowes into a compendious summe and certaine order: The which principles being but fewe, and therefore easie to be knowen and borne away, without doubt in small time, and little trauaile, will open a most large entrance to the vnderstanding of all that which is contained in this Arte. Neither was I in this frustrate at all of my expectation: For in conclusion after much deliberation, I haue found out this Arte, from the which onely dependeth the knowledge of all that which a man may performe with a weapon in his hand, and not onely with those weapons which are found out in these our dayes, but also with those that shall be inuented in time to come: Considering this Arte is grounded vpon Offence and Defence, both the which are practised in the straight and circuler lynes, for that a man may not otherwise either strike or defend. | ||

Et uolendo insegnar questa ragione dell'adoprar l'armi con quel maggior ordine & con quella maggior chiarezza che sia possibile, ho posto nel primo loco i principii di tutta l'arte nominando gli Auertimenti, i qua li essendo per sua natura notissimi a ciascuna persona di sana mente, non ho fatto altro che solamente raccontarli senza renderne ragion alcuna, come cosa superflua. |

And because I purpose to teach how to handle the Weapon, as orderly and plainly as is possible: I haue first of all layd down the principles or groundes of all the Arte, calling them Aduertisements, the which, being of their owne nature verie well knowen to all those that are in their perfect wittes: I haue done no other then barely declared them, vvithout rendring any further reason, as being a thing superfluous. | ||

Dopo questi principii ho trattato delle cose piu semplici, & de li poi alle composite ascendendo, dimostro quello che in tutto l'armi si possa fare. Et perche nell'insegnar le scienze & l'arti, si denono molto piu estimar le cose, che le parole, però non ho uoluto elegger un modo di parlare copioso, & sonoro, ma uno breue & familiare: il qual modo di parlare si come in poco fascio contiene in se & molte cose & grandi, cosi ricerca un lettore acuto & tardo, il quale uoglia a passo a passo penetrar nella midolla delle cose. |

These principles being declared, I haue next handled those things, vvhich are, and be, of themselues, Simple, then (ascending vp to those that are Compound) I shewe that vvhich may be generally done in the handling of all Weapons. And because, in teaching of Artes and Sciences, Things are more to be esteemed of than VVordes, therefore I vvould not choose in the handling hereof a copious and sounding kinde of speach, but rather that vvhich is more briefe and familiar. Which maner of speach as in a small bundle, it containeth diuers weightie things, so it craueth a slowe and discreete Reader, who will soft and faire pearce into the verie Marrowe thereof. | ||

Prego dunque il benigno lettore che tale si dimostri nel leggere la presente mia opera, sendo sicuro in tal modo leggendola di deuerne raccogliere grandissimo frutto & honore: nè è dubio alcuno che colui, il quale sarà fornito a bastanza di questa cognitione, & haurà a proportione la persona esercitata, non sia di gran lunga superiore ad ogni altro, quando però ui sarà da luna & l'altra parte egual forza & uelocità. |

For this cause I beseech the gentle Reader to shewe himselfe such a one in the reading of this my present worke, assuring him selfe by so reading it, to reape great profite and honour thereby. And [vi] Not doubting but that he (who is sufficientlie furnished with this knowledge, and hath his bodie proporcionably exercised thereunto) shall far surmount anie other although he be indewed with equal force and swiftnes. | ||

Et percioche questa arte è un principal membro della scienza militare, la quale insieme con le lettere è l’ornamento del mondo, però non si deue ella esercitare nelle brighe & risse, che si fanno per le contrade, ma come honoratissimi cauallieri riserbarsi di adoprarla per l'honor della patria, del suo Principe, per l'honor delle Donne, & di loro stessi, & finalmente per la uittoria de gli esserciti. |

Moreouer, because this art is a principal member of the Militarte profession, vvhich alltogether (vvith learning) is the ornament of all the World, Therefore it ought not to be exercised in Braules and Fraies, as men commonlie practise in euerie shire, but as honorable Knights, ought to reserue themselues, & exercise it for the aduantage of their Cuntry, the honour of vveomen, and conqueringe of Hostes and armies. | ||

|

[vii] An Aduertisement to the curteous reader. GOod Reader, before thou enter into the discourse of the hidden knowledge of this honourable excerise of the weapon now layd open and manifested by the Author of this worke, & in such perfectnes translated out of the Italian tongue, as all or most of the marshal mynded gentlemen of England cannot but commend, and no one person of indifferent iudgement can iustly be offended with, seeing that whatsoeuer herein is discoursed, tendeth to no other vse, but the defence of mans life and reputation: I thought good to aduertise thee that in some places of this booke by reason of the aequiuocation of certaine Italian wordes, the weapons may doubtfully be construed in English. Therefore sometimes fynding this worde Sworde generally vsed, I take it to haue beene the better translated, if in steede thereof the Rapier had beene inserted: a weapon more vsuall for Gentlemens wearing, and fittest for causes of offence and defence: Besides that, in Italie where Rapier and Dagger is commonly worne and vsed, the Sworde (if it be not an arming Sworde) is not spoken of. Yet would I not the sence so strictly to be construed, that the vse of so honourable a weapon be vtterly [viii] reiected, but so redd, as by the right and perfect vnderstanding of the one, thy iudgement may som what be augmented in managing of the other: Knowing right well, that as the practise and vse of the first is commendable amongst them, so the second cannot so farre be condemned, but that the wearing thereof may well commend a man of valour and reputation amongst vs. The Sworde and Buckler fight was long while allowed in England (and yet practise in all sortes of weapons is praisworthie,) but now being layd downe, the sworde but with Seruing-men is not much regarded, and the Rapier fight generally allowed, as a wapon because most perilous, therefore most feared, and thereupon priuate quarrels and common frayes soonest shunned. | |||

|

But this peece of work, gentle Reader, is so gallantly set out in euery point and parcell, the obscurest secrets of the handling of the weapon so clerely vnfolded, and the perfect demeaning of the bodie vpon all and sudden occasions so learnedly discoursed, as will glad the vnder stander thereof, & sound to the glory of all good Masters of Defence, because their Arte is herein so honoured, and their knowledge (which some men count infinite) in so singuler a science, drawen into such Grounds and Principles, as no wise man of an vnpartiall iudgement, [ix] and of what profession soeuer, but will confesse himself in curtesie farre indebted both to the Author & Translator of this so necessarie a Treatise, whereby he may learne not onely through reading & remembring to furnish his minde with resolute instructions, but also by practise and exercise gallantly to perfourme any conceited enterprise with a discreete and orderly carriage of his bodie, vpon all occasions whatsoeuer. | |||

Gentle Reader, what other escapes or mistakings shall come to thy viewe, either friendly intreate thee to beare with them, or curteously with thy penne for thine owne vse to amend them. Fare-well. | |||

[x] The Sortes of VVeapons handled in this Treatise. THe single Rapier, Or single Sworde. Falsing of Blowes and Thrusts. At single rapier &c. |

Figures |

Italian Transcription (1570) |

English Transcription (1594) | |

|---|---|---|---|

The second part entreating of deceits and falsings of blows and thrusts |

[119] DELL' INGANO. |

[133] THE Second Part intreatinge of Deceites and Falsinges of Blowes and Thrustes. | |

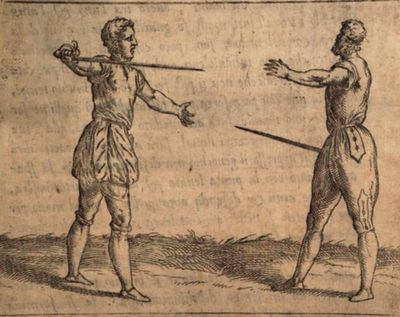

Being come to the end of the true Art, and having declared all which seemed convenient and profitable for the attainment of true judgment in the handling of the weapon and of the entire knowledge of all advantages, by the which as well all disadvantages are known: It shall be good that I entreat of Deceit or Falsing, as well to perform my promise, as also to satisfy those who are greatly delighted to skirmish, not with the pretense to hurt or overcome, but rather for their exercise and pastime: |

BEinge come to the end of the true Arte, and hauing declared all that which seemed conuenient and profitable for the attaynement of true iudgement in the handling of the weapon & of the entire knowledg of al aduātages, by the which as well al disaduantages are knowen: It shall be good that I intreat of Deceite or Falsing, aswel to performe my promise, as also to satisfie those who are greatly delighted to skirmish, not with pretence to hurt or ouer come but rather for their exercise & pastime: | ||

In which it is a brave and gallant thing and worthy of commendations to be skillful in the apt managing of the body, feet and hands, in moving nimbly sometimes with the hand, sometimes with the elbow, and sometimes with the shoulder, in retiring, in increasing, in lifting the body high, in bearing it low in one instant: in brief, delivering swiftly blows as well of the edge as of the point, both right and reversed, nothing regarding either time, advantage or measure, bestowing them at random every way. |

In which it is a braue and gallant thing and worthy of commendations to be skilfull in the apte managing of the bodie, feete and hands, in mouing nimblie sometimes with the hand, some-times with the elbow, and sometimes with the shoulder, in retiring, in increasing, in lifting the bodie high, in bearing it low in one instant: in breif, deliuering swiftlie blows aswell of the edge as of the point, both right and reuersed, nothing regarding either time, aduantage or measure, bestowing them at randone euerie waie. | ||

But diverse men being blinded in their own conceits, do in these actions certainly believe that they are either more nimble, either more wary and discreet then their adversary is: of which their foolish opinion they are beastly proud and arrogant: |

But diuers men being blinded in their owne conceites, do in these actions certainly beleeue that they are either more nimble, either more warie & discreet [134] then theire aduersarie is: Of which their folish opinion they are all beastlie proud and arrogant: | ||

And because it has many times happened them, either with a false thrust, or edge blow, to hurt or abuse the enemy, they become lofty, and presume thereon as though their blows were not to be warded. But yet for the most part it falls out, that by a plain simple swab having only a good stomach and stout courage, they are chopped in with a thrust, and so miserably slain. |

And because it hath manie times happened them, either with a false thrust, or edge blowe, to hurte or abuse the enemie, they become loftie, and presume thereon as though their blowes were not to be warded. But yet for the most part it falleth out, that by a plain simple swad hauing onely a good stomack and stout courage, they are chopt in with a thrust, and so miserablie slaine. | ||

For avoiding of this abuse, the best remedy is, that they exercise themselves in delivering these falses only in sport, and (as I have before said) for their practice and pastime: Resolving themselves for a truth, that when they are to deal with any enemy, and when it is upon danger of their lives, they must then suppose the enemy to be equal to themselves as well in knowledge as in strength, and accustom themselves to strike in as little time as is possible, and that always being well warded. And as for these Falses or Slips, they must use them for their exercises and pastimes sake only, and not presume upon them, except it beagainst such persons, who are either much more slow, either know not the true principals of this Art. For Deceit or Falsing is no other thing, then a blow or thrust delivered, not to the intent to hurt or hit home, but to cause the enemy to discover himself in some part, by means whereof a man may safely hurt him in the same part. And look how many blows or thrusts there may be given, so many falses or deceits may be used, and a great many more, which shall be declared in their proper place: The defense likewise whereof shall in few words be last of all laid upon you. |

For auoiding of this abuse, the best remedie is, that they exercise themselues in deliuering these falses onlie in sport, and (as I haue before said) for their practise & pastime: Resoluing themselues for a truth, that when they are to deal with anie enemie, & when it is vpon danger of their liues, they must then suppose the enemie to be equall to themselues aswel in knoledge as in strength, & accustome themselues to strik in as litle time as is possible, and that alwaies beeing wel warded. And as for these Falses or Slips, they must vse them for their exercise & pastimes sake onelie, and not presume vpon them, except it bee against such persons, who are either much more slow, either know not the true principels of this Art. For Disceit or Falsing is no other thing, then a blow or thrust deuered, not to the intent to hurt or hitt home, but to cause the enemie to discouer himselfe in some parte, by meanes whereof a man maie safely hurt him in the same part. And looke how manie blowes or thrusts there maie be giuen, so manie falses or deceits may be vsed, and a great manie more, which shal be declared in their proper place: The defence likewise whereof [135] shal in few words be last of all laid open vnto you. | ||

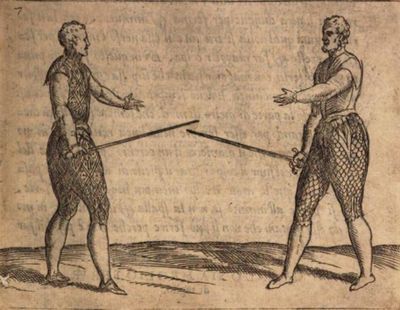

Deceits or falsings of the single sword, or single rapier As I take not Victory to the end and scope of falsing, but rather nimbleness of body and dexterity in play: So, casting aside the consideration how a man is either covered or discovered, and how he has more or less advantage, I say that there may be framed at single sword so many wards, as there be ways to move the hand and foot. |

Deceits or Falsings of the single Sword, or single Rapier AS I take not Victorie to be the end and scope of falsing, but rather nimblenes of bodie and dexteritie in plaie: So, casting aside the consideration how a man is either couered or discouered, and how he hath more or lesse aduantage) I saie that there maie be framed at the single sword so manie wards, as there be waies how to moue the arme hand and foot. | ||

Therefore in falsing there may be framed the high, low, and broad ward, with the right foot behind and before: a man may bear his sword with the point backwards and forwards: he may bear his right hand on the left side, with his sword's point backwards: he may stand at the low ward with the point backwards and forwards, bending towards the ground. And standing in all these ways, he may false a thrust above, and force it home beneath above, he may false it without and deliver it within, or contrariwise. |

Therefore in falsinge there may bee framed the high, lowe, and brode warde, with the right foote behind and before: a man may beare his sword witht the poynt backewardes and forwardes: he may beare his right hand on the left sid, with his swords poynt back wards: he may stand at the low warde with the point backewardes and forwardes, bending towardes the grounde. And standing in all these waies, he may false a thrust aboue, and force it home beneath: and contrarie from beneth aboue, he may false it without and deliuer it within, or contrariwise. | ||

And according to the said manner of thrusting he may deliver edge-blows, right, reversed, high and low, as in that case shall most advantage him. Farther he may false an edge-blow, and deliver it home: as for example, to false a right blow on high, and deliver home a right and reverse blow, high or low. In like for the reverse is falsed, by delivering right or reverse blows, high or low. |

And according to the saide manner of thrusting he may deliuer edge-blowes, right, reuersed, high and lowe, as in that case shal most aduantage him. Farther he may false an edgeblow, and deliuer it home: as for example, to false a right blowe on highe, and deliuer home a right and reuerse blowe, high or lowe. In like sortthe reuerse is falsed, by deliuering right or reuerse blowes, high or lowe. | ||

But it is to be considered, that when he bears his sword with his point backwards, he false no other then the edge-blow, for then thrusts are discommodious. And because men do much use at this weapon, to beat off the point of the sword with their hands: therefore he must in that case for his greater readiness and advantage, suffer his sword to sway to that side, whether the enemy bears it, joining to that motion as much force as he may, performing therein a full circular blow, and delivering it at the enemy. |

[136] But it is to be considered, that when he beareth his sworde with his poynt backewardes, he false no other than the edgeblow, for then thrusts are discommodius. And because men do much vse at this weapon, to beate off the poynt of the sworde with their handes: therefore he must in that case for his greater redines & aduantage, suffer his sword to swaie to that side, whether the enemy beateth it, ioyning to that motion as much force as he may, performing therin a ful circuler blowe, and deliuering it at the enemie. | ||

And this blow is most ready, and so much the rather, it is possible to be performed, by how much the enemy thinks not, that the sword will pass in full circle that way, for the enemy being somewhat disappointed, by beating off the sword, after which beating, he is also to deliver his thrust, he cannot so speedily speed both those times but that he shall be first struck with the edge of the sword, which he had before so beaten off. |

And this blow is most readie, and so much the rather, it is possible to be performed, by how much the enemie thinketh not, that the sword will passe in full circle that waie, for the enemie being somwhat disapoynted, by beating off the sworde, after which beating, he is also to deliuer his thrust, he cānot so speedely spēd both those times but that he shalbe first strokē with the edge of the sworde, which he had before so beaten off. | ||

General advertisements concerning the defenses Because it chances commonly, that in managing of the hands, men bear no great regard, either to time or advantage, but do endeavor themselves after diverse and sundry ways and means to encounter the enemy's sword: therefore in these cases, it is very profitable to know how to strike, and what may be done in the shortest time. |

Generall aduertisementes concerning the defences. BEcause it chaunceth commonly, that in managing of the handes, men beare no great regard, either to time or aduantage, but do endeuour themselues after diuers & sundry waies & meanes to encounter the enemies sword: therfore in these cases, it is verie profitable to knowe how to strike, and what may be done in shortest time. | ||

The enemy's sword is encountered always either above, either in the middle, either beneath: and in all these ways a man finds himself to stand either above, either beneath, either within, either without. And it falls out always that men find themselves underneath with the sword at the hanging ward, when they are to ward high edge-blows or thrusts: and this way is most commonly used: The manner whereof is, when the hand is lifted up to defend the sword being thwarted, and the point turned downwards: when one finds himself so placed, he ought not to recover his sword from underneath, and then to deliver an edge-blow, for that were too long, but rather to strike nimbly that part of the enemy underneath, which is not warded, so that he shall do no other then turn his hand and deliver an edge-blow at the legs which surely speeds. |

The enemies sword is encountred alwaies either aboue, either in the midle, either beneath: & in al these [137] waies a man findeth himself to stand either aboue, either beneth, either within, either without. And it fales out alwaies that men finde themselues vndernethe with the sword at the hanging warde, when they are to ward high edgeblowes or thrusts; and this waie is most commonly vsed: The manner whereof is, when the hand is lifted vp to defend the sword being thwar ted, and the poynt turned downewards: when one findeth himselfe so placed, he ought not to recouer his sworde from vnderneath, and then to deliuer an edge-blowe, for that were to long, but rather to strike nimbly that part of the enemie vnderneath, which is not warded, so that he shall do no other then turne his hand & deliuer an edge-blow at the legges which surely speedeth. | ||

But if he find himself in defense either of the reverse or thrust, to bear his sword aloft and without, and not hanging, in this the safest thing is, to increase a pace, and to seize upon the enemy's hand or arm. |

But if he finde himselfe in defence either of the reuerse or thrust, to beare his sword aloft and without, and not hanging, in this the safest thing is, to increase a pace, and to seasyn vpon the enimies hand or arme. | ||

The self same he ought to do, finding himself in the middle, without and underneath: But if he find himself within, he cannot by any means make any seizure, because he shall then be in great peril to invest himself on the point of the enemy's sword. |

The selfe same he ought to doe, finding himselfe in the midle, without and vnderneath: But if he finde himselfe within, he cannot by any meanes make anie seasure, because he shall be then in greate perill to inuest himselfe on the poynt of the enemies sworde. | ||

Therefore to avoid the said point or thrust, he must turn his fist and deliver an edge-blow at the face, and withdraw himself by voiding of his foot towards the broad ward. And if he find himself beneath, and have encountered the enemy's edge-blow, either with the edge, or with the false or back of the sword, being beneath: then without any more ado, he ought to cut the legs, and void himself from the enemy's thrust. And let this be taken for a general rule: the body must be borne as far off from the enemy as it may. And blows always are to be delivered on that part which is found to be most near, be the stroke great or little. And each man is to be advertised that when he finds the enemy's weapon underneath at the hanging ward, he may safely make a seizure: but it would be done nimbly and with good courage, because he does then increase towards his enemy in the straight line, that is to say, increase on pace, and therewithal take holdfast of the enemy's sword, near the hilts thereof, yea though his hand were naked, and under his own sword presently turning his hand outwards, which of force wrests the sword out of the enemy's hand: neither ought he to fear to make seizure with his naked hand, for it is in such a place, that if should with his hand encounter a blow, happily it would not cut because the weapon has there very small force. All the hazard will be, if the enemy should draw back his sword, which causes it to cut. For in such sort it will cut mightily: but he may not give leisure or time to the enemy to draw back, but as soon as the seizure is made, he must also turn his hand outwards: in which case, the enemy has no force at all. |

Therefore to avoide the saide poynt or thrust, he must turne his fist and deliuer an edge-blow at the face, and withdraw himselfe by voiding of his foote towardes the broad ward. And if he finde himselfe beneath, & haue encountred the enemies edgeblow, either with the edge, or with the false or backe of the sword, being beneath: then without any more adoe, he ought to cut the legges, and void himself from the [138] enimies thrust. And let this be taken for a generall rule: the bodie must be borne as far of from the enimy as it may. And blowes alwaies are to be deliuered on that parte which is founde to be most neare, be the stroke great or little. And each man is to be aduertised that when he findes the enimies weapon vnderneath at the hanging ward, he may safely make a seisure: but it would be done nimbly and with good courage, because he doth then increase towards his enimie in the streight lyne, that is to saie, increase on pace, and therewithall take holdfast of the enemies sword, nere the hiltes thereof, yea though his hand were naked, and vnder his owne sworde presently turning his hand outwardes, which of force wresteth the sworde out of the enimies hand: neither ought he to feare to make feisure with his naked hand, for it is in such a place, that if he should with his hand encounter a blowe, happely it would not cut because the weapō hath thereverie small force. All the hazard wil be, if the enimie should drawe backe his sword, which causeth it to cutte. For in such sorte it will cut mightily: but he may not giue leasure or time to the enimie to drawe backe, but as soone as the seisure is made, he must also turne his hand outwards: in which case, the enimie hath no force at all. | ||

These manner of strikings ought and may be practiced at all other weapons. Therefore this rule ought generally to be observed, and that is, to bear the body different from the enemy's sword, and to strike little or much, in small time as is possible. |

These maner of strikings ought and maie be practised at all other weapons. Therefore this rule ought generally to be obserued, and that is, to beare the bodie different from the enimes sword, and to strike litle or much, in as small time as is possible. | ||

And if one would in delivering of a great edge-blow, use small motion and spend little time he ought as soon as he has struck, to draw or slide his sword, thereby causing it to cut: for otherwise an edge-blow is to no purpose, although it be very forcibly delivered, especially when it lights on any soft or limber thing: but being drawn, it does every way cut greatly. |

And if one would in deliuering of a great edge-blowe, vse small motion and spende little time hee [139] ought as soone as he hath stroken, to drawe or slide his sword, thereby causing it to cute: for otherwise an edge-blowe is to no purpose, although it be verie forcibly deliuered, especialy when it lighteth on any soft or limber thing: but being drawen, it doth euery way cute greatly. | ||

Of sword and dagger, or rapier and dagger All the wards which are laid down for the single sword, may likewise be given for the sword and dagger. And there is greater reason why they should be termed wards in the handling of this, than of the single sword, because albeit the sword is borne unorderly, and with such disadvantage, that it wards in a manner no part of the body, yet there is a dagger which continually stands at his defense, in which case, it is not convenient that a man lift up both his arms and leave his body open to the enemy: for it is neither agreeable to true, neither to false art considering that in each of them the endeavor is to overcome. And this manner of lifting up the arms, is as if a man would of purpose be overcome: Therefore, when in this deceitful and false art, one is to use two weapons, he must take heed that he bear the one continually at his defense, and to handle the other every way to molest the enemy: sometime framing one ward, sometimes another: and in each of them to false, that is, to feign a thrust, and deliver a thrust, to false a thrust, and give an edge-blow: and otherwise also, to false an edge-blow, and to deliver an edge-blow. And in all these ways to remember, that the blow be continually different from the false: That is, if the thrust be falsed above to drive it home below: If within, yet to strike without, and falsing an edge-blow above, to bestow it beneath: or falsing a right blow, to strike with the reverse: or sometimes with a right blow, but yet differing from the other. And after an edge-blow on high, to deliver a reverse below. In fine, to make all such mixture of blows, as may bear all these contrarieties following, to wit, the point, the edge, high, low, right, reversed, within, without. But, I see not how one may practice any deceit with the dagger, the which is not openly dangerous. As for example, to widen it and discover some part of the body to the enemy, thereby provoking him to move, and then warding, to strike him, being so disappointed: but in my opinion, these sorts of falses of discovering the body, ought not to be used: For it behooves a man, first, safely defend to himself, and then to offend the enemy, the which he cannot do, in the practice of the said falses, if he chance to deal with an enemy that is courageous and skillful. But this manner of falsing next following, is to be practiced last of all other, and as it were in desperate cases. And it is, either to feign, as though he would forcibly fling his dagger at the enemy's face, (from the which false, he shall doubtless procure the enemy to ward himself, either by lifting up the arms, or by retiring himself, or by moving towards one side of other, in which travail and time, a man that is very wary and nimble, may safely hurt him) or else instead of falsing a blow, to fling the dagger indeed at the enemy's face. In which chance or occasion, it is necessary that he have the skill how to stick the dagger with the point. But yet howsoever it chance, the coming of the dagger in such sort, does so greatly trouble and disorder the enemy, that if a man step in nimbly, he may safely hurt him. |

Of sword and dagger, or Rapier and dagger. AL the wardes which are laide downe for the single sword, may likewise be giuen for the sworde and dagger. And there is greater reason why they should be termed wardes in the handling of this, than of the single sword, because albeit the sword is borne vnorderly, & with such disaduantage, that it wardeth in a maner no parte of the bodie, yet there is a dagger which continually standeth at his defence, in which case, it is not conuenient that a man lift vp both his armes and leaue his bodie open to the enimie: for it is neither agreeable to true, neither to false arte considering that in each of them the endeuor is to ouercome. And this manner of lifting vp the armes, is as if a man wold of purpose be ouercome: Therfore, when in this deceitfull and false arte, one is to vse two weapons, he must take hede that he beare the one cōtinually at his defence, and to handle the other euerie waye to molest the enimie: somtime framing one warde, somtimes an other: and in each of them to false, that is, to faine a thrust, and deliuer a thrust, to false a thrust, and giue an edge-blowe: and otherwise also, to false an edge-blowe, and to deliuer an edge- [140] blowe. And in all these wayes to remember, that the blowe be continually different from the false: That is, if the thrust be falsed aboue to driue it home belowe: If within, yet to strike it without, and falsing an edgeblowe aboue, to bestowe it beneath: or falsing a right blowe, to strike with the reuerse: or sometimes with a right blowe, but yet differing from the other. And after an edgeblowe on high, to deliuer a reuerse belowe. In fine, to make all such mixture of blowes, as may beare all these contrarieties following, to wit, the point, the edge, high, lowe, right, reuersed, within, without. But, I see not howe one may practise any deceit with the dagger, the which is not openly daungerous. As for example, to widen it and discouer some part of the bodie to the enemie, thereby prouoking him to moue, and then warding, to strike him, being so disapointed: but in my opinion, these sortes of falses of discouering the bodie, ought not to be vsed: For it behoueth a man, first, safely to defend himselfe, and then to offend the enimie, the which he cannot do, in the practise of the said falses, if he chaunce to deale with an enimie that is couragious and skilfull. But this manner of falsing next following, is to be practised last of all other, and as it were in desperate cases. And it is, either to faine, as though he would forcibly fling his dagger at the enemies face, (frō the which false, he shal doubtles procure the enemie to warde himselfe, either by lifting vp his armes, or by retyring himself, or by mouing towards one side or other, in which trauaile & time, a man that is verie warie and nimble, may safely hurt him:) or els in steede of falsing a blowe, to fling [141] the dagger in deede at the enimies face. In which chaunce or occasion, it is necessarie that he haue the skill how to sticke the dagger with the poynt. But yet howsoeuer it chaunce, the comming of the dagger in such sort, doth so greatly trouble and disorder the enemie, that if a man step in nimbly, he may safely hurt him. | ||

These deceits and falses, of the sword and dagger, may be warded according as a man finds it most commodious either with the sword, or else with the dagger, not regarding at all (as in true art) to defend the left side with the dagger, and the right side with the sword: For in this false art men consider not either of advantage, time, or measure, but always their manner is (as soon as they have found the enemy's sword) to strike by the most short way, be it either with the edge, or point, notwithstanding the blow be not forcible, but only touch weakly and scarcely: for in play, so it touch any way, it is accounted for victory. |

These deceits and falses, of the sword and dagger, may be warded according as a man findes it most commodious either with the sworde, or els with the dagger, not regarding at all (as in true arte) to defend the left side with the dagger, and the right sid with the sword: For in this false arte men consider not either of aduantage, time, or measure, but alwaies their manner is (as soone as they haue found the enimies sword) to strike by the most short waie, be it either with the edge, or point, notwithstanding the blowe be not forcible, but onely touch weakely & scarslv: for in plaie, so it touch any waie, it is accounted for victorie. | ||

Concerning taking holdfast, or seizing the enemy's sword, I commend not in any case, that seizure be made with the left hand, by casting a way of the dagger, as else I have seen it practiced: but rather that it be done keeping the sword and dagger fast in hand. And although this seem impossible, yet every one that is nimble and strong of arm, may safely do it. And this seizure is used as well under an edge-blow, as under a thrust in the manner following. |

Concerning taking holdfast, or seising the enimies sword, I commend not in any case, that seisure be made with the left hand, by casting a way of the dagger as else where I haue seene it practised: but rather that it be done keeping the sword and dagger fast in hand. And although this seeme vnpossible, yet euery one that is nimble & strong of arme, may safely do it. And this seisure is vsed aswell vnder an edgeblowe, as vnder a thrust in manner following. | ||

When an edge-blow or thrust comes above, it must be encountered with the sword without, on the third or fourth part of the enemy's sword, and with the dagger born within, on the first or second part thereof: having thus suddenly taken the enemy's sword in the middle, to turn forcibly the enemy's sword outwards with the dagger, keeping the sword steadfast, and as straight towards the enemy as possible by means whereof it may the more easily be turned. And there is no doubt but the enemy's sword may be wrung out of his hand, and look how much nearer the point it is taken, so much the more easily it is turned or wrested outwards, because it makes the greater circle, and the enemy has but small force to resist that motion. |

When the edgeblowe or thrust commeth aboue, it must be incountred with the sword without, on the third or fourth parte of the enimies sword, and with [142] the dagger borne within, on the first or second parte thereof hauing thus sodenly taken the enimies sword in the middle, to turne forciblie the enimies sword outwardes with the dagger, keeping the sword stedfast, and as streight towards the enimie as is possible by meanes whereof it may the more easely be turned. And there is no doubt but the enimies sworde may be wrong out of his hand, and looke how much nearer the poynt it is taken, so much the more easelie it is turned or wrested outwards, because it maketh the greater circle, and the enimie hath but smal force to resist that motion. | ||

Of sword and cloak, or rapier and cloak For to deceive the enemy with the cloak, it is necessary to know how many ways it may serve the turn, and to be skillful how to fold it orderly about the arm, and how to take advantage by the largeness thereof: and farther to understand how to defend, and how to offend and hinder the enemy therewith, because it fails not always, that men fight with their cloak wrapped about the arm, and the sword in hand, Therefore it is the part of a wise man, to know also how to handle the cloak after any other manner. |

Of Sword and Cloke, or Rapier and Cloke.

FOR to disceyue the enimie with the cloake, it is necessarie to know how many waies it may serue the turne, and to be skilfull how to fould it orderly about the arme, and how to take aduantage by the largenes thereof: and farther to vnderstand how to defend, and how to offend and hinder the enimie therewith, because it fales not out alwaies, that men fight with their cloake wrapped about the arme, and the sword in hand, Therefore it is the parte of a wise man, to knowe also how to handle the cloake after any other manner. | ||

Wherefore one may get the advantage of the Cloak, both when it is about his body, and when it is folded about his arm: The Cloak being about the arm in this manner. When it chances that any man to bicker with his enemy, with whom he is at point to join, but yet happily wears about him at that instant no kind of weapon, whereas his enemy is weaponed, and threatens him, then by taking both sides of the cloak as near the collar as is possible, he may draw if over his own head, and throw it at his enemy's face, who then being entangled and blinded there with, may either be thrown down, or disfurnished of his weapon very easily by him that is nimble, especially if he have to deal against one who is slow. A man may after another manner take the advantage of the cloak which the enemy wears, by taking with one hand both sides thereof, near the collar: which sides being strongly held, cause the cloak to be a gin being violently held, and plucked with one hand, he may so forcibly strike him with the other on the face or visage, that he will go near hand to break his neck. |

Wherefore one may get the aduātage of the cloke, both when it is about his bodie, and when it is folded about his arme: The cloke being about the arme in this maner. When it chaunceth any man to bicker [143] with his enimie, with whom he is at poynt to ioyne, but yet happelie weareth about him at that instant no kind of weapon, whereas his enimie is weaponed, & threatneth him, then by taking both sides of the cloake as neare the coller as is possible, he may draw it ouer his owne head, and throwe it at his enimies face, who then being in angled and blinded there with, may either be throwen downe, or disfurnished of his weapon very easely by him that is nimble, especially if he haue to deale against one that is slow. A man may after another manner take the aduantage of the cloake which the enimie weareth, by taking with one hande both sides thereof, neere the coller: which sides being strongly holden, cause the cloak to be a ginne or snare about the enimes necke, the which ginne being violently haled, and plucked with one hande, he may so forciblie strike him with the other on the face or visage, that he will goe neere hande to breake his necke. | ||

There be many other ways whereby one may prevail with the cloak, to the greatest part whereof, men of mean judgment may easily attain unto. Therefore when one has his cloak on his arm, and sword in his hand, the advantage he gets thereby, besides the warding of blows, for that has been declared in the true art is, that he may molest his enemy by falsing to fling his cloak, and then to fling it in deed. But to false the flinging of the cloak is very dangerous, because it may not be done but in long time. And the very flinging of the cloak, is as it were a preparation to get the victory, and is in a manner rather true art then deceit, considering it is done by the straight or some other short line: neither for any other cause is this the rather here laid down, in deceit, then before in true art, then for that when one overcomes by this means, he seems not to conquer manfully, because he strikes the enemy before blinded with the cloak. Therefore when one minds to fling his cloak, he may either do it from and with his arm, or else with his sword: in so doing it is necessary, that he have not the cloak too much wrapped about his arm: I say, not above twice, neither to hold it straight or fast with his hand, that thereby he may be the better able when occasion serves to fling it more easily. If therefore he would fling it with his arm, and have it go with such fury, and make such effect as is required, he must of force join to the flinging thereof the increase of a pace, on that side where the cloak is, but first of all he must encounter, either find, either so endure the enemy's sword, that by the means of the increase of that pace it may do no hurt. |

There be manie other waies whereby one may preuaile with the cloake, to the greatest parte whereof, men of meane iudgment may easely attaine vnto. Therefore when one hath his cloake on his arme, and sword in his hand, the aduantage that he getteth therby, besides the warding of blowes, for that hath bene declared in the true arte is, that he may molest his enimie by falsing to fling his cloake, and then to flinge it in deed. But to false the flingyng of the clok is verie daungerous, because it may not be done but in long time. And the verie flinging of the cloake, is as it were a preparation to get the victorie, and is in a manner rather true art then deceit, cōsidering it is don by the [144] streyght or some other shorte line: neither for any other cause is this the rather here laide downe, in deceite, then before in true arte, then for that when one ouercometh by theis meanes, he seemes not to conquere manfully, because he strikes the enimie before blinded with the cloake. wherefore when one mindeth to flinge his cloake, he may either do it from and with his arme, or else with his sword: and in so doing it is necessarie, that he haue not the cloake too much wrapped about his arme: I saie, not aboue twice, neither to hold it streight or fast with his hande, that thereby he may be the better able when occasion serueth to fling it the more easelie. If therefore he would fling it with his arme, and haue it goe with such fury, and make such effect as is required, he must of force ioyne to the flinging thereof the increase of a pace, on that side where the cloake is, but first of all he must incounter, either finde, either so ensure the enimies sword, that by the meanes of the increase of that pace it may do no hurte. | ||

And it is requisite in every occasion, that he find himself to stand without: and when either an edge-blow or a thrust comes, be it above or in the middle, as soon as he has warded it with his sword, he shall increase a pace and fling his cloak, howsoever it be folded, either from the collar, either from any other part, or else to hale it off from his shoulder, although it be on his shoulder: and in this order it is easily thrown, and is thereby the more widened in such sort, that the enemy is the more entangled and snared therewith. |

And it is requisite in euerie occasion, that he finde himselfe to stand without: and when either an edgeblow or a thrust comes, be it aboue or in the middle, as soone as he hath warded it with his sword, he shall increase a pace and fling his cloake, how soeuer it be folded, either from the coller, either from any other parte, or else to hale it off from his shoulder, although it bee on his shoulder: and in this order it is easelie throwne, & is thereby the more widned in such sort, that the enimie is the more entangled and snared therewith. | ||

Concerning the flinging of the cloak with the sword, I say, it may be thrown either with the point, either with the edge: with the point when one stands at the low ward with the right foot behind, and the cloak before: In which case the cloak that would be well and thick doubled and placed on the arm, but not wrapped. And instead of driving a thrust with the point which shall be hidden behind the cloak, he shall take the cloak on the point of the sword, and with the increase of a pace, force it at the enemy's face. And in this manner the cloak is so forcibly, and so covertly delivered and flung, that the enemy is neither aware of it, neither can avoid it, but of force it lights on his face, by means whereof, he may be struck at pleasure in any part of the body. |

Concerning the flinging of the cloake with the [145] sword, I saie, it may be throwen either with the point, either with the edge: with the poynt when one standeth at the lowe warde with the right foote behinde, and the cloake before: In which case the cloake would be well and thicke doubled and placed on the arme, but not wrapped. And in steed of driuing a thrust with the poynt which shalbe hidden behinde the cloake, he shal take the cloake on the poynt of the sworde, and with the increase of a pace, force it at the enimies face. And in this maner the cloake is so forcib lie, and so couertly deliuered and flinged, that the enimie is neither a ware of it, neither can avoyde it, but of force it lighteth on his face, by meanes whereof, he may be stroken at pleasure in any parte of the bodie. | ||

The cloak may be flung or thrown with the edge of the sword, when one stands at the low ward, with the point of the sword turned backwards, one the left side and the cloak upon it, folded at large upon the arm up to the elbow: but not fast wrapped about it, and whilst he falses a reverse, he may take the cloak on the edge of the sword and fling it towards the enemy, and then strike him with such a blow as shall be then most fit for his advantage deliver. |

The cloake may be flong or throwen with the edge of the sworde, when one standeth at the lowe warde, with the poynt of the sword turned backewardes, one the left side and the cloake vpon it, folded at large vpon the arme vp to the elbowe: but not fast wrapped about it, and whilest he falseth a reuerse, he may take the cloake on the edge of the sword and fling it towards the enimie, and then strike him with such a blow as shal be then most fit for his aduantage deliuer. | ||

Many other deceits there may be declared of the cloak, as well of flinging as of falsing it: but because I think these to be sufficient for an example to frame many other by, I make an end. |

Manie other deceites there might be declared of the cloake, aswell of flinging as of falsing it: but because I thinke these to be sufficient for an example to frame manie other by, I make an ende. | ||

Falsing of blows, of sword and buckler square target, and round target Being of the opinion that as touching deceit, there is but one consideration to be had of all these three weapons, and for because all the difference which may be between them is laid down and declared in the true art, in the consideration of form of each of them: Therefore I am willing rather to restrain myself, then to endeavor to fill the lease with the idle repetition of one thing twice. |

[146] Of Sword and buckler, square Target and round Target. BEing of opinion that as touching deceite, there is but one consideration to be had of all these three weapons, and for because all the difference which may be betwen them is laide downe and declared in the true arte, in the consideration of the forme of each ofthem: Therefore I am willing rather to restraine my selfe, then to indeuoure to fill the leafe with the idle repetition of one thing twice. | ||

All these three weapons ought to be borne in the fist, the arm stretched out forwards, and this is evidently seen in the square Target and buckler: the round Target also, because by reason of his greatness and weight, it may not be held in the only fist, and forward, in which kind of holding, it would ward much more is borne on the arm, being stretched forth with the fist forwards, which is in manner all one, or the self same. Therefore one may false as much with the one as with the other, considering there is no other false used with them then to discover and frame diverse wards, bearing no respect to any advantage. And yet there is this difference between them, that with the round Target, one may easily ward both edge-blows and thrusts, and with the square Target, better than with any other, he may ward edge-blows, because it is of square form: and the edge of the sword may easily be retained with the straight side thereof, which is not so easily done with the buckler: for over and besides the warding of thrusts, the buckler is not so sure of itself, but requires aid of the sword. Edge-blows also when they come a thwart (for in that case, they encounter the circumference thereof: the which if it chance, the sword not to encounter on the diameter, or half, in which place the sword is only stayed, but does encounter it, either beneath, either above the said diameter (may easily slip and strike either the head or thighs: therefore let every man take heed and remember, that in striking at the buckler, either with the point or edge of the sword, he deliver it crossing or a thwart. |

All theis three weapons ought to be borne in the fist the arme stretched outforwardes and this is euidently seene in the square Target and buckler: the round Target also, because by reason of his greatnes and waight, it may not be holden in the onelie fist, & forwarde, in which kind of holding, it would warde much more is borne on the arme, being stretched foorth with the fist forwardes, which is in manner all one, o the selfe same. Therefore one may false as much with the one as with the other, considering there is no other false vsed with them then to discouer and frame diuers wards, bering no respect to any aduantage. And yet there is this difference betwene them that with the round Target, one may easely warde both edgeblowes and thrustes, and with the square Target, better than with any other, he may warde edgeblowes, because it is of square forme: and the edge of the sword may easely be retained with the streight side thereof, which is not so easely done with the buckler: for ouer and besides the warding of thrustes, the buckler is not so sure of itself, but re- [147] quireth aide of the sworde. Edge-blowes also when they come a thwart (for in that case, they incounter the circumference thereof: the which if it chaunce, the sword not to encounter on the diameter, or halfe, in which place the sword is onelie staied, but doth encounter it, either beneath, either aboue the said diameter (maie easelie slippe and strike either the heade or thighs: therfore let euetie man take heede and remember, that in striking at the buckler, either with the poynte or edge of the sword, he deliuer it crossing or a thwarte. | ||

As concerning the falses and deceits, which may be used in the handling of these weapons, as at the single sword, they are infinite, so at these weapons they are much more, if the number of infinite may be exceeded. For besides, that with the sword one may false a thrust, an edge-blow, on high, a low, within without, and frame diverse other unorderly wards, There remains one deceit or false properly belonging unto these, which is, to bear the buckler, square Target, or round Target, wide from the body, and therewithal to discover himself, to the end the enemy may be hindered, and lose time in striking, being therewithal sure and nimble to defend himself and offend the enemy. And this he may practice in every ward, but more easily with the square Target than with the other two, because it is big and large enough, and may easily encounter and find the enemy's when it comes striking: but this happens not in the round Target, because his form is circular, neither in the buckler, because, besides his roundness, it is also small: by means of which two things, blows are very hardly encountered except a man be very much exercised in the handling thereof. And because there are two weapons, the one of offense, and the other of defense: it is to be considered, that when by means of a false thrust or edge-blow, the enemy's round Target, square Target or buckler, is only bound to his ward, and his sword remains free and at liberty, one resolve himself to strike immediately after the falsed thrust, for then he may very easily be hurt by the enemy's sword. Therefore let him remember for the most part, to false such thrusts, against the which, besides the weapon of defense, the sword be also bound to his ward, or else to false edge-blows from the knee downwards: for seeing the round target, or any of the other two, may not be used in that placed at his defense, which as soon as it is found, and thereby ensured that it may do no hurt, a man may then step forwards, and deliver such a blow as he best may without danger. |

As concerning the falses and deceites, which may be vsed in the handling of theis weapons, as at the single sworde, they are infinite, so at theis weapons they are much more, if the number of infinite may be exceded. For besides, that with the sword one may false a thrust, an edgeblowe, on high, a lowe, within without, and frame diuers other vnorderlie wardes, There remaineth one deceite or false properlie belōging vnto theis, which is, to beare the bukler, squar Target, or round Target, wide from the bodie, and therewithall to discouer himselfe, to the end the enimie may be hindred, and lose time in striking, being therewithal sure & nimble to defend himself & offēd the enimie. And this he may practise in euerie ward, but more easelie with the square Target than with the other two, because it is bigge and large inough, & may easelie encounter and find the enimies when it commeth striking: but this happeneth not in the rounde Target, because his forme is circuler, neither in the buckler, because, besides his roundnes, it is also small: by meanes of which two things, blowes are [148] very hardly encountred, except a man be very much exercised in the handling thereof. And because there are two weapons, the one of offence, and the other of defence: it is to be considered, that when by meanes of a false thrust or edgblowe, the enimies round Target, square Target or buckler, is onely bound to his warde, and his sword remaines free and at libertie, one resolue not himselfe to strike immediatly after the falced thrust, for then he may verie easelie be hurt by the enimies sword. Therefore let him remember for the most parte, to false such thrustes, against the which, besides the weapon of defence, the sword be also bound to his warde, or else to false edgeblowes from the knee downewards: for seeing the round target, or any of the other two, may not be vsed in that place, of force the sword must be there placed at his defence, which as soone as it is found, and thereby ensured that it may do no hurte, a man may then step forwardes, and deliuer such a blowe as he best may without daunger. | ||

An advertisement concerning the defenses of the false of the round target Every time one uses to false with round Target, square Target, and buckler, or as I may better say, with the sword accompanied with them, he falses either an edge-blow, either a thrust, either leaves some part of the body before discovered. Against all the falses of the edge, which come from the knee upwards, the round Target or any of the rest, must be oppressed, and then suddenly under them a thrust be delivered, against that part which is most disarmed. But if blows come from the knee downwards, they of force must be encountered with the sword, and always with the false or back edge thereof, whether that the blow be right or reversed: and therewithal the enemy's leg must be cut with the edge prepared without moving either the feet or the body. And this manner of striking is so short that it safely speeds. Moreover, all thrusts and other edge-blows, as well high as low may, nay rather ought to be warded, by accompanying the target or other weapon of defense with the sword, whose point would be bent towards the enemy, and as soon as the enemy's sword is encountered, if it be done with the false edge of the sword, there is no other to be done, then to cut his face or legs. |

An aduertisement concerning the defences of the false of the round Target. EVerie time that one vseth to false with round Target, square Target, and buckler, or as I may better saie, with the sword accompanied with them, he falseth either an edge-blowe, either a thrust, either leaueth some parte of the bodie before discouered. Against all the falces of the edge, which come from the knee vpwards, the round Target or any of the rest, must be oppressed, and then [149] suddenly vnder them a thrust be deliuered, against that parte which is most disarmed. But if blowes come from the knee downwardes, they of force must be encountred with the sword, and alwaies with the false, or backe edge thereof, whether that the blowe be right or reuersed: & therewithall the enimies legge must be cutt with the edge prepared without mouing either the feete or bodie. And this manner of striking is so shorte that it safely spedeth. Moreouer, all thrusts and other edgeblowes, aswell high as lowe may, naie rather ought to be warded, by accompaning the target or other weapon of defence with the sword, whose poynt would be bent towards the enimie, & assoone as the enimies sword is encountred, if it be done with the false edge of the sword, there is no other to be done, then to cut his face or legges. | ||

But if the sword be encountered with the right edge then if he would strike with the edge, he must of force first turn his hand and so cut. And this manner of striking and defending, does properly belong unto the round Target, square Target and buckler, and all other ways are but ane and to small purpose: for to encounter first and then to strike, causes a man to find himself either within the enemy's Target or sword, by which means he may easily strike, before either the sword or Target may ward again. |

But if the sword be encountred with the right edge then if he would strik with the edge, he must offorce first turne his hand and so cute. And this manner of striking and defending, doth properlie belong vnto the round Target, square Target and buckler, and all other waies are but vaine and to small purpose: for to encounter first and then to strike, causeth a man to finde himselfe either within the enimies Target or sword, by which meanes he may easelie strike, before either the sword or Target may warde againe. | ||

But if any man ask why this kind of blow carries small force, and is but weak? I answer, true it is, the blow is but weak, if it were delivered with an axe or a hatchet, which as they say, have but short edges, and makes but one kind of blow, but if it be delivered with a good sword in the foresaid manner, because it bears a long edge, it does commodiously cut, as soon as the edge has found the enemy's sword, and especially on those parts of the body which are fleshly and full of sinews. Therefore speaking of deceit or falsing, a man must always with the sword and round Target and such like, go and encounter the enemy's blows, being accompanied together. And as soon as he has found the enemy's sword, he shall within it, cut either the face or the legs, without any further recovery of his sword, to the intent to deliver either thrusts, or greater edge-blows: for if one would both defend and strike together, that is the most short way that is. |